Abstract

Objective

To assess the relative contributions of environmental and genetic factors to variation in cystic fibrosis (CF) pulmonary disease.

Study design

Genetic and environmental contributions were quantified using intra-pair correlations and differences in CF-specific FEV1 measures from 134 monozygous twins and 272 dizygous twins and siblings while in different living environments (i.e. living with parents vs. living alone) as well as using intra-individual differences in lung function from a separate group of 80 siblings.

Results

Lung function among monozygous twins was more similar than among dizygous twin and sibling pairs, regardless of living environment, affirming the role of genetic modifiers in CF lung function. Regression modeling revealed that genetic factors account for 50% of lung function variation, unique environmental and stochastic factors 36%, and shared environmental factors, 14% (Model p: <0.0001). The intra-individual analysis produced similar estimates for the contributions of the unique and shared environment. The shared environment effects appeared primarily due to living with a sibling with CF (p: 0.003), rather than factors within the parental household (p: 0.310).

Conclusions

Genetic and environmental factors contribute equally to lung function variation in CF. Environmental effects are dominated by unique and stochastic effects rather than common exposures.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis; heritability, lung disease, genetics; FEV1

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a monogenic disease affecting over 30,000 individuals in the United States and over 70,000 worldwide. The gene responsible for CF, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene (CFTR), was identified over twenty years ago (1, 2). CFTR genotype-phenotype studies have demonstrated that lung disease severity can vary drastically in individuals with identical CFTR genotypes (3-5). These observations indicate that factors besides CFTR, such as environmental factors and modifier genes must contribute to lung function decline, the major cause of mortality in CF. Indeed, the much of progressive increase in the median predicted age of survival of patients with CF in the U.S. to 36.9 years as of 2006 can be attributed to the substantial effect of environmental modification (6). On the other hand, recent twin-based studies have demonstrated that genetic factors also play a role in lung disease variation (7, 8).

Quantifying the environmental contribution to lung function is important for several reasons. First, even though a number of environmental factors have been demonstrated to affect CF lung disease, including second-hand smoke exposure (9-13), socio-economic status (14), healthcare access (15-17), and air pollution (18), estimates of the contribution of environment factors to lung disease as a whole have not been provided by previous studies (7, 8). Second, parsing the contribution of shared versus unique environmental exposures can help assess risks when patients with CF come into contact with others in settings such as clinics and camps. Third, quantifying the contributions of environmental factors relative to genetic factors in lung disease variation can inform efforts to identify gene modifiers using genome-wide approaches. Both genetic and environmental factors have been quantified for other Mendelian disorders, such as the age of onset of Huntington’s disease (19).

To estimate the relative contribution of genetic factors, we examined intra-pair correlations and confirmed our findings using an intra-pair difference regression. To estimate the relative contribution of environmental factors, we employed the previous intra-pair difference regression and then validated our findings using intra-individual difference regression analysis in a different subset of the study population. These are the first quantitative estimates of the relative contributions of environmental and genetic factors to CF lung disease variation.

METHODS

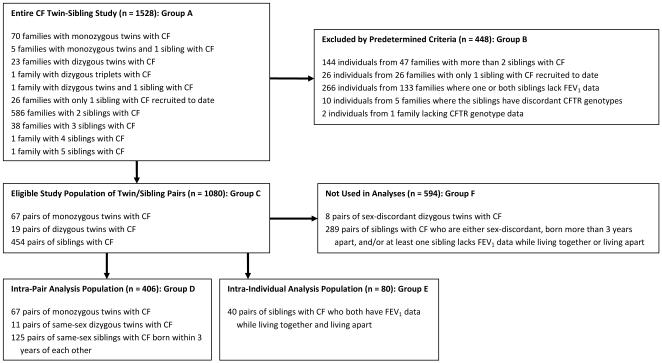

1528 individuals in 752 families were recruited through the Cystic Fibrosis Twin-Sibling Study, including 75 sets of monozygous (MZ) twins, 24 sets of dizygous (DZ) twins, and 1 set of DZ triplets (Figure 1; available at www.jpeds.com). Subjects attended U.S. CF centers, excepting 12 families recruited from Australia and 6 from Scotland. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or guardians. Zygosity was verified using the AmpFlSTR Profiler kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA).

FIGURE 1.

Study Population Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Demographic characteristics of each group (A-F) can be found in Table 2 (online)

Subjects met diagnostic criteria for CF (20). 144 individuals from families with more than 2 affected siblings were excluded owing to the complexity of interactions among family members. 26 subjects were excluded as their sibling was not enrolled at the time of analysis. 114 individuals were excluded as both family members of a pair lacked pulmonary function data; 152 individuals were excluded as one family member of these pairs lacked pulmonary function data. Of these 190 individuals lacking data, 102 were less than 6 years old. Ten siblings were excluded owing to discordant CFTR genotypes among affected family members. Two siblings were excluded owing to lack of CFTR genotype data. Thus, 1080 subjects in 540 families comprise the overall population from which to select family pairs for intra-pair and intra-individual analyses (Table I; available at www.jpeds.com).

TABLE 1. CHARACTERISTICS OF INCLUDED AND EXCLUDED SUBJECTSa.

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | Group E | Group F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF Twin-Sibling Study |

Excluded | Study Population | Intra-Pair Analyses | Intra-Individual Analyses |

Not Used in Analyses |

|

| n | 1535 | 448 | 1080 | 406 | 80 | 594 |

|

Age as of 12/31/07 (yrs:

Mean ± SD) b |

16.7 ± 9.7 [0.3 – 64.6] (n = 1501) |

12.8 ± 11.4 [0.3 – 64.6] (n = 421) |

18.2 ± 8.6 [6.1 – 54.7] |

18.7 ± 8.7 [6.2 – 50.6] |

26.4 ± 6.3 [19.0 – 47.6] |

16.7 ± 8.1 [6.1 – 54.7 |

| Sex: %Male c | 51.8 (n = 1519) |

48.1 (n = 439) |

53.3 | 56.7 | 52.5 | 51.2 |

|

CFTR Genotype: %ΔF508

Homozygote d |

49.3 (n = 1488) |

46.1 (n = 408) |

50.6 | 53.7 | 57.5 | 47.5 |

|

Maximum FEV1CF% in the

most recent year of data e |

69.3 ± 26.3 Median: 77.3 (n = 1311) |

69.2 ± 26.0 Median: 78.1 (n = 231) |

69.3 ± 26.3 Median: 77.3 |

68.3 ± 27.8 Median: 76.9 |

74.8 ± 22.1 Median: 81.1 |

69.2 ± 25.7 Median: 76.6 |

Please see Figure 1 for a visual depiction of the derivation of these groups. Group A is comprised of groups B and C; group C is comprised of groups D, E, and F.

As not all individuals have pulmonary function test (PFT) data available, age was calculated from a particular time rather than from the time of the most recent PFT as in Table 1. Individuals in group B are younger than those in C (t test p value: <0.0001) as group B includes many individuals too young to perform PFTs reliably. Using an ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction, group E is older than group D (p value: <0.001) and group F (p value: <0.001) as individuals in this group require both members to have lung function while living together and living and apart, hence they are older. Group D is also older than group F (ANOVA p value: <0.001).

Groups B and C do not differ by sex frequencies (chi square p value: 0.06). Groups D, E, and F also do not differ from each other by sex frequencies (chi square p value: 0.23).

By CFTR genotype frequencies, groups B and C do not differ (chi square p value: 0.15), groups D and E do not differ (chi square p value: 0.32), and groups D and F also do not differ (chi square p value: 0.06). However, group E has a higher frequency of ΔF508 homozygotes than does group F (chi square p value: 0.045). As group E was used for intra-individual analyses where an individual is compared to him or herself, we would expect CFTR genotype to have less of an impact on the analyses, but this possibility cannot be excluded.

As not all individuals have PFT data for while living together or living apart, the maximum CF-specific percentile in the most recent year of PFT data was selected as an inclusive PFT measure to compare individuals in the various populations. There is no difference in this measure of lung function between groups B and C (t test p value: 0.99) or between groups D, E, and F (ANOVA p value: 0.13).

Intra-pair analyses were conducted using all available monozygous twin pairs (n = 67 pairs) (Table II). The relative paucity of pairs of DZ twins both affected by CF necessitated creating sibling pair proxies, similar to previous CF twin-based studies (7, 8). Within families in the combined DZ twins/siblings (DZ/Sib), siblings and twins are sex concordant (i.e., both males or both females) and born within three years of each other to minimize cohort variation. The DZ/Sib group included 11 pairs of DZ twins and 125 pairs of siblings; the mean age difference between siblings in this group was 2.1 ± 0.6 years. Intra-individual analyses for replication were conducting using 40 pairs of siblings not used in the intra-pair analyses; these subjects had lung function data before and after leaving the parental home.

TABLE 2. CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDY SUBJECTS.

| Intra-Pair Analyses | Intra-Individual Analyses |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MZ Twins | Combined DZ Twins/Siblings |

Siblings | |

| All Individuals | 134 (67 pairs) | 272 (136 pairs)a | 80 (40 pairs) |

|

Mean Age ± SD at

most recent PFT (range) |

18.9 ± 8.9 yrs (6.1-39.8 yrs) |

17.4 ± 7.5 yrs (6.1-40.0 yrs) |

26.0 ± 6.0 yrs (18.7-40.0 yrs) |

| Sex: % Male | 53.7 | 58.1 | 52.5 |

|

CFTR Genotype: %

ΔF508 Homozygote |

62.7 | 49.3 | 57.5 |

|

Mean FEV1CF%

while living together |

59.3 ± 23.9 Median: 62.2 (n = 130) |

61.4 ± 23.3 Median: 65.2 (n = 260) |

63.3 ± 21.3 Median: 65.8 (n = 80) |

|

Mean FEV1CF%

while living apart |

54.5 ± 30.1 Median: 52.6 (n = 65) |

63.5 ± 28.0 Median: 71.3 (n = 90) |

71.2 ± 21.1 Median: 77.3 (n = 80) |

Definition of abbreviations: DZ = Dizygous; MZ = Monozygous; PFT = Pulmonary function test.

Same-sex DZ twins (n = 11 pairs) and same-sex siblings born within three years of each other (n = 125 pairs).

The calendar year of leaving the parental home was ascertained via questionnaires or clinical record review for 328 out of 1080 subjects; for these subjects, the mean age at leaving the parental home was 19.6 ± 2.9 years. 636 subjects were younger than 18 years old at the time of their most recent pulmonary function test and were assumed to be living in the parental home. For the remaining 116 subjects, the year was assigned based on when they turned 18. Living together was defined as the time period before or on the year of moving out for the elder family member; living apart was defined as the time period after the year of moving out for each individual. 1029 subjects had data while living together, and 365 while living apart.

Pulmonary function data were supplemented using the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Data Registry. Raw FEV1 (liters) was converted to CF-specific percentiles [Range: 0-100%] for subjects between 6 and 40 years of age; this age- and sex-corrected phenotype allows for easy comparison of subjects with CF (21) and remains relatively stable over time (Mean rate of decline is 0.0 ± 3.0% per year) (7). For the study population, the mean standard deviation for the average CF-specific FEV1 percentile (averaged for all pulmonary function tests available for an individual) was 13.6% (n = 1056). Tests performed after lung transplantation were excluded. Mean lung function while living together, while living apart, and during discrete time periods was derived by averaging the highest percentile per calendar quarter (7).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical methods used include Student t-tests, chi-square tests, ANOVA tests with Bonferroni corrections, and linear regression models. All regression models were subject to clustering by family. The dependent variable was either an intra-pair or intra-individual (absolute) difference of the CF-specific FEV1; the specific coding of independent variables for each model is provided in the Results section. Heritability estimates were calculated as twice the difference between the MZ twin r and the DZ/Sib group r (22). For these estimates, mean Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were determined by permuting the assignment of twins or siblings as “A” or “B” 106 times to avoid bias that might occur if one twin was consistently assigned as “A.” Intercooled Stata 10 (StataCorp LP., College Station, TX) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Subjects in the intra-individual analyses were older on average than subjects in the intrapair analyses (t-test p value: <0.0001); however, as CF-specific FEV1 percentiles correct for age this difference was irrelevant in our analysis. Although more of the MZ twins were ΔF508 CFTR homozygotes than other subjects, this was not statistically significant (chi square p value: 0.070). Mean lung function was not statistically different among all groups while living together (ANOVA p value: 0.453), but MZ twins had decreased lung function compared with the siblings in the intra-individual analyses (ANOVA Bonferroni p value: 0.001).

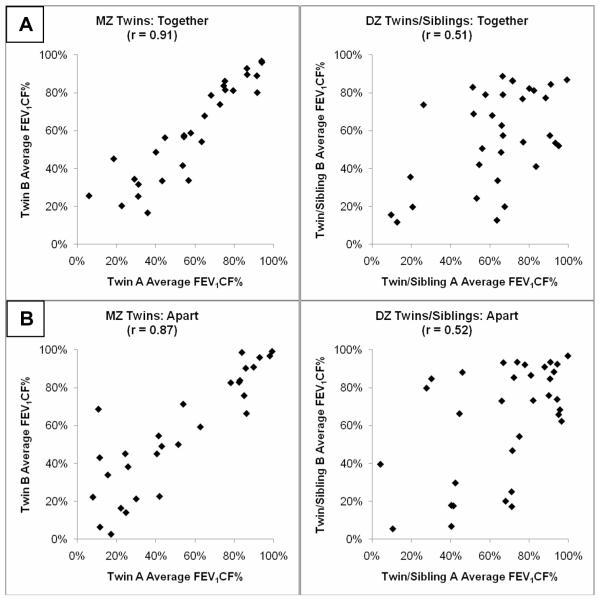

Correlating lung function from 65 pairs of MZ twins and 130 pairs of DZ/Sib pairs from the intra-pair population yielded a heritability estimate of 0.57; the data for this estimate were obtained when the pairs were living together. This estimate (>0.5) suggests a substantial genetic contribution to lung function variation. However, genetic effects may be overestimated due to the shared environment and environmental effects may be underestimated due to survival biases (i.e. underrepresentation of highly discordant pairs where only one individual survives). To address these issues, we examined the correlations in subjects while living together and while living apart. The MZ twin and DZ/Sib groups had similar amounts of time living together in the parental home (11.4 vs. 11.3 years), and living apart after leaving the parental home (5.6 vs. 4.4 years). The correlations in MZ twins (n = 29 pairs) versus DZ twins and siblings (n = 33 pairs) before and after leaving the parental household provide information on the contribution of genetic factors versus shared environment. Lung function remained highly correlated among MZ twins after they separate into less similar environments (Living together: 0.91 vs. living apart: 0.87) (Figure 2; available at www.jpeds.com); DZ twins and siblings also showed minimal change with changes in living environment (0.51 vs. 0.52).

FIGURE 2. DZ twins and siblings show greater intra-pair differences in lung function (CF-specific FEV1 percentiles) when living together and when living apart than MZ twins.

The plots demonstrate the concordance in average lung function between the same pairs of family members when living together [A] and living apart [B]. Most PMZ twins within a pair either both experience improving or declining lung function over time; the same is not necessarily true for DZ twins and siblings where the members follow different trajectories.

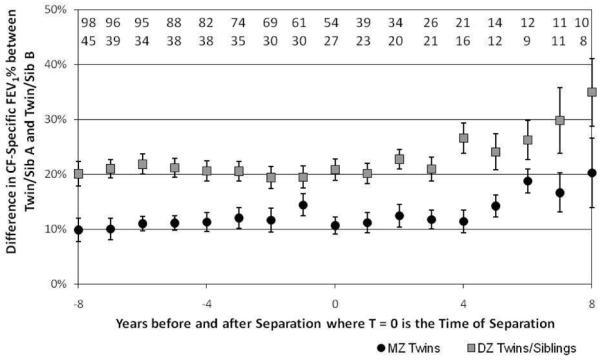

Intra-pair differences in lung function between pairs of MZ twin and pairs of DZ twins and siblings were used an alternative means of estimating of genetic and non-genetic contributions to disease variation. The mean (absolute) difference in CF-specific FEV1 between twin A and twin B (or sibling A and sibling B) for DZ twins and siblings was greater than MZ twins, regardless of living environment (Table III: Together p value: 0.0006; apart: 0.0035), but the mean differences of MZ or DZ/Sib pairs living together versus living apart were not statistically different (Together p value: 0.1412; apart: 0.3091). Of note, this difference appeared to begin to increase for both groups 3 to 4 years after the first family member left the parental home; the difference in lung function between MZ twins increased by 18 percentile points per 10 years, and for DZ twins and siblings, by 25 percentile points per 10 years, but neither of these rates is statistically different from baseline (p value: MZ, 0.075; DZ/Sib, 0.302) (Figure 3; available at www.jpeds.com). Together, these analyses indicate that genetic factors continue to influence lung function in twins and siblings with CF, even after living apart for 5 years.

TABLE 3. MEANS OF INTRA-PAIR CF-SPECIFIC FEV1 PERCENTILE DIFFERENCES WHILE LIVING TOGETHER VS. LIVING APARTa.

| ALL SUBJECTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MEAN ± S.D. | MZ Twins (n = 29 pairs) | Combined DZ Twins/ Siblings (n = 33 pairs) |

T-Test p valueb [Difference: 95%CI] |

|

Living Together

(Years of Data) |

8.0 ± 6.9 (11.4 ± 3.3) |

19.2 ± 15.5 (11.3 ± 3.9) |

0.0006 [−11.2: −17.5, −5.0] |

|

Living Apart

(Years of Data) |

11.2 ± 11.9 (5.6 ± 5.0) |

22.4 ± 16.3 (4.4 ± 3.6) |

0.0035 [−11.2: −18.5, −3.8] |

|

T-Test p value

c

[Difference: 95%CI] |

0.1412 [−3.3: −7.7, 1.2] |

0.3091 [−3.2: −9.5, 3.1] |

|

| ΔF508 HOMOZYGOTES ONLY | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MZ Twins (n = 19 pairs) | Combined DZ Twins/ Siblings (n = 17 pairs) |

T-Test p valueb [Difference: 95%CI] |

|

|

Living Together

(Years of Data) |

6.9 ± 6.1 (11.3 ± 2.9) |

21.1 ± 16.4 (12.3 ± 3.9) |

0.0012 [−14.2: −22.4, −6.0] |

|

Living Apart

(Years of Data) |

7.8 ± 6.5 (4.9 ± 4.2) |

28.3 ± 17.4 (4.2 ± 2.7) |

<0.0001 [−20.5: −29.2, −11.8] |

|

T-Test p value

c

[Difference: 95%CI] |

0.6630 [−0.9: −5.2, 3.4] |

0.1069 [−7.2: −16.1, 1.7] |

|

Mean differences are the mean of the absolute differences in CF-specific FEV1s for each twin/sibling pair for the indicated time periods. Only pairs where both members had data while living together and living apart are included.

Unpaired T-test p value is for MZ twin group versus the combined DZ twin/sibling group.

Paired T-test p value is for living together versus living apart.

FIGURE 3. Mean difference in lung function (CF-specific FEV1 percentiles) increases between twins and siblings after they leave the parental home.

Each point represents the mean absolute difference (± S.E.) in cross-sectional lung function between family members. The numbers above the datapoints represent the number of pairs contributing to that timepoint (Upper: DZ/Sib; Lower: MZ). Negative years represent the time leading up to leaving the parental home, positive years the time afterwards.

One means to determine if accumulated environmental exposures contribute to variation is to examine correlations between twin and sibling pairs over time. To do this, we derived correlations and heritability estimates from all eligible subject pairs from the intra-pair population within a specified age range. Although heritability estimates were >0.5 for each age stratum between ages 10 years old and 30 years old, correlation (r values) between family members progressively decreased by age group for both MZ twins and DZ twins/siblings after age 18 (Table IV: available at www.jpeds.com). These data indicate a role for non-genetic factors, which could be due to changes in the shared environment, unique environment, or stochastic factors.

TABLE 4. CORRELATION OF LUNG FUNCTION (CF-SPECFIC FEV1 PERCENTILES) FOR TWIN AND SIBLING PAIRS WITHIN DISCRETE AGE GROUPSa.

| Age Group | MZ Twins Mean r value |

Combined DZ Twins/Siblings Mean r value |

Heritability Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-10 yo | 0.6529 (n = 57 pairs) |

0.4764 (n = 116 pairs) |

0.35b |

| 10-14 yo | 0.8791 (n = 45 pairs) |

0.5070 (n = 101 pairs) |

0.74 |

| 14-18 yo | 0.9094 (n = 39 pairs) |

0.6147 (n = 74 pairs) |

0.59 |

| 18-22 yo | 0.8799 (n = 31 pairs) |

0.5153 (n = 43 pairs) |

0.73 |

| 22-26 yo | 0.8494 (n = 24 pairs) |

0.3465 (n = 25 pairs) |

1.00 |

| 26-30 yo | 0.7871 (n = 13 pairs) |

0.2725 (n = 11 pairs) |

1.00 |

| 30-40 yo | 0.5441 (n = 7 pairs) |

0.3637 (n = 7 pairs) |

0.36b |

Derivation of r values and heritability estimates are described in the Methods section. All pairs where both members of the pair had data within the specific age range were included (out of a total of 67 MZ twin pairs and 136 DZ twin and sibling pairs).

Lower heritability estimates observed in the 6-10yo and 30-40yo groups are likely due to increased variability in young children’s pulmonary function tests and fewer numbers of older subjects, respectively.

Differences in MZ twins (sharing 100% of their genes) living together (sharing a common environment) can be attributed to effects of unique environment and/or stochastic factors. In this study, MZ twins living together showed appreciable differences in lung function measures (Table III: mean difference: 8.0). CFTR genotype was not a significant source of variation, as analysis limited to ΔF508 homozygotes (Table III) obtained a similar p values for the genetic contribution and a similar mean difference for MZ twins living together (6.9). We then performed regression modeling of intra-pair differences to determine the contribution of unique environmental factors and to evaluate the relative contributions of genes and environment:

Y = Intra-pair CF-specific FEV1 (absolute) difference; X1 = [0 if living together, 1 if living apart]; X2 = [0 if MZ twins, 1 if DZ twins/siblings]

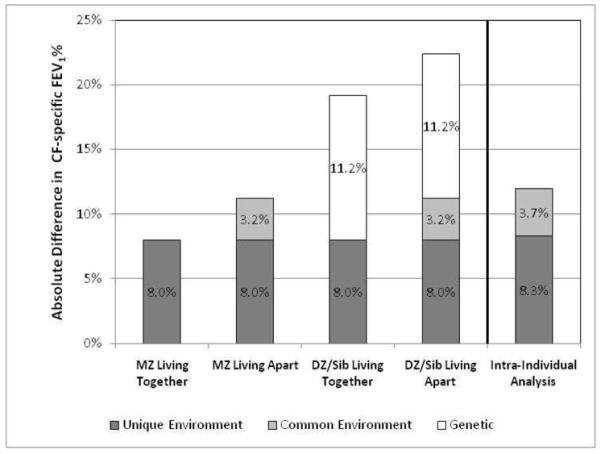

The intercept value (β0) was assumed to be due to unique environmental and stochastic factors, after accounting for shared environmental factors (β1) and genetic (β2). Using the 62 pairs in Table III, it was found that β0 = 8.0 ± 1.5 (p value: <0.001), β1 = 3.2 ± 1.9 (p value: 0.100), and β2 = 11.2 ± 2.7 (p value: <0.001), with an overall model p value of 0.0001. Thus, unique environmental factors accounted for 36% (8.0/22.4) of variation, common or shared environmental factors 14% (3.2/22.4) and genetic factors 50% (11.2/22.4). The genetic and environmental contributions appear to be of similar magnitude (3.2 [shared] + 8.0 [unique] = 11.2 [total environment] vs. 11.2 [genetic]).

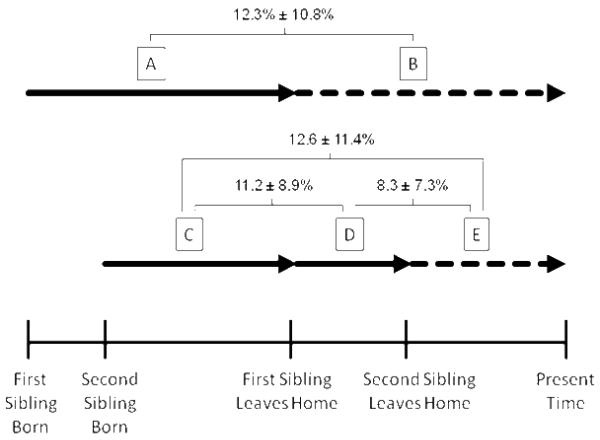

To verify the above estimates, we examined lung function in the same individual before and after leaving the parental household (Figure 4). By comparing lung function over different time frames in the same individual, genetic effects are assumed to be nil; variation in that individual is assumed to be a function of shared and unique environmental changes. This method also allows partitioning of the contributions of the parental household vs. the effect of living with another sibling with CF. The intra-individual analysis was performed on a different subset of the study population not studied in the prior analyses and was restricted to 40 sibling pairs who had lung function measures available for both siblings before and after they left the parental household.

FIGURE 4. Differences in intra-individual lung function (CF-specific FEV1 percentiles) between different living environments.

Solid lines represent time spent in the parental home; dashed lines represent time spent outside the parental home. The lettered boxes refer to discrete periods of time for which lung function is averaged. A: Firstborn sibling from birth to leaving the parental home. B: First sibling after leaving home. C: Second sibling from birth to when the first sibling leaves the home. D: Second sibling from when the first sibling leaves home until the second sibling leaves home. E: Second sibling after leaving home. CF-specific FEV1 percentiles for 40 pairs of siblings was averaged over each lettered time period, and mean absolute differences (± S.D.) between selected time periods are provided. Sibling pairs were included only if data existed for all lettered time periods. Siblings were not necessarily concordant for sex or born within 3 years of each other.

To perform the analysis, lung function was averaged for each patient when living with parents and a sibling with CF, when living with only parents, and when living away from both sibling and parents. As shown in Figure 4, changes in CF-specific FEV1 appear to be greater when patients moved away from both parents and siblings (i.e., A to B [12.3] and C to E [12.6]), compared with moving away from only the parents (D to E [8.3]). Furthermore, the presence of another sibling with CF affected an individual’s lung function as demonstrated by changes in the sibling that remained with the parents as the other sibling left home (C to D [11.2]). The contribution of the sibling (C to D) and parental household (D to E) did not equal the combined total (C to E) owing to the presence of unique environmental factors throughout the period C to E.

To quantify the contribution of the parental versus affected sibling effects, intra-individual differences were placed into a regression model:

Y = Intra-individual (absolute) difference in CF-specific FEV1; X1 = [0 if no change, 1 if separating from a sibling with CF]; X2 = [0 if no change, 1 if leaving parental household]

As before, the intercept value (β0) was assumed to be due to unique environmental and stochastic factors over time, after accounting for shared environmental factors due to the presence of a sibling with CF (β1) and the parental household (β2). The initial model demonstrated that β0 = 7.0 ± 1.4 (p value: <0.001), β1 = 4.1 ± 1.3 (p value: 0.003), and β2 = 1.3 ± 1.2 (p value: 0.310), with an overall model p value of 0.0110. For the final model, the non-significant parental variable (X2) was dropped, yielding β0 = 8.3 ± 1.2 (p value: <0.001), and β1 = 3.7 ± 1.3 (p value: 0.007), with an overall model p value of 0.0072. The final intra-individual regression model generates very similar estimates for the contribution of environmental factors (Unique: 8.3; shared: 3.7) as did the intra-pair model (8.0; 3.2).

DISCUSSION

Determining the causes of lung disease variation will help identify targets for ameliorating morbidity and extending lifespan for individuals with CF. Our results demonstrate that environmental and genetic factors contribute approximately equally to lung function variation. As a number of studies have described shared environmental exposures that significantly affect CF lung function (e.g. second-hand smoke), we were surprised to find the majority of the environmental contribution is mediated through effects that act uniquely (or stochastically) on an individual. This finding was replicated using intra-individual analyses in a different study population. These similar analytic findings are illustrated in Figure 5 when comparing MZ twins living apart with the intra-individual analysis.

FIGURE 5. Summary of genetic and environmental effects on lung function variation using intra-pair and intra-individual differences.

The data in this table are derived from the coefficients from the intra-pair and intra-individual regressions in the Results section. For the four leftmost bars, which are based on the intra-pair regression, the sources of variation are shown for each group. The rightmost bar is based on the intra-individual regression. Of note is that the genetic contribution to lung function (0.112) equals the environmental contribution (0.080 + 0.032) for the intra-pair regression. Also of note is that the estimates of the contributions of the common environment and unique environment from the intra-pair analysis are very similar those generated from the independent study sub-group used in the intra-individual analysis with a different regression strategy.

Our analyses confirm the potency of the genetic influence on lung function variation (7, 8) and add several new and useful observations. Specifically, MZ twins’ lung function tends to remain highly similar even after leaving home in contrast to DZ twins and siblings. These results support ongoing efforts to identify genetic modifiers through candidate and genome-wide approaches. Also, our results add that heritability remains relatively constant over time. This suggests either the variance due to genetic and environmental sources remains constant or the variance from both genetic sources and the environment (or age) is increasing thus preserving heritability (23). Decreasing correlation coefficients with age as seen in Table IV precludes the first explanation. At least two possibilities may underlie increasing phenotypic variation over time with constant heritability. First, gene-age interactions may exist as some modifier genes may have differing ages of onset of effect based on genotype; one potential example in CF is mannose binding lectin (MBL) (24, 25). Second, cumulative environmental exposures may precipitate novel modifier gene-environment interactions. Each explanation implies that stratifying patients with CF by age should be considered to optimize searches for environmental and genetic modifiers of lung function.

Although we found that the majority of the environmental contribution is mediated through unique factors, a closer examination of the common or shared environmental contribution turned up an unsuspected finding; namely we found that the presence of a sibling with CF results in greater intra-pair differences in lung function than does the parental environment. We speculate that parents caring for two children with CF divide their time and resources in caring for both children, but once the older sibling has left the home, the remaining sibling’s lung function is increased (before older sibling leaves: 62.4 ± 21.9 vs. after: 70.9 ± 21.1; t test p value: <0.0001), perhaps as a result of increased resources being devoted to that remaining sibling. In contrast, leaving the parental home may induce less variation because the effects of the parental environment (e.g. exercise regimens, nutritional habits) may persist even after the individual moves out. This is supported by results shown in Figure 3 where differences in lung function between siblings do not appear to increase until several years after moving out of the parental home. Alternatively, the absence of increasing differences may be due to siblings moving back into the parental home (26).

The current study had several limitations. A component of genetic variation not included in this analysis is variation due to CFTR as family members shared the same CFTR genotypes. This may not be a major shortcoming as numerous studies have indicated that CFTR genotype has a minimal role in variation of CF lung function (3-5). Current methods of estimating sources of variation do not allow parsing of the relative contribution of unique (e.g., one twin smoking) vs. stochastic (e.g., one twin contracts influenza) factors, or gene-environment interactions, which are likely an important source of variation, to be specifically isolated. Twins may also elect to live with each other after leaving the parental home, and this may lead to genetic effects being overestimated and environmental effects being underestimated. Our analyses of common or shared environmental factors are structured on leaving the parental home, and do not necessarily capture variation due to CF care centers or regional factors such as climate or air pollution. Finally, our data following leaving the parental home is limited to 5 years of lung function data. To help address some of these limitations, the twins and siblings with CF will be re-evaluated after a considerably longer duration of time living apart.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that environmental and genetic factors make contributions of approximately similar magnitude to variation in CF lung disease, and justify the need for ongoing and future studies to examine both sets of factors. Furthermore, the important contribution of unique environment (and possibly stochastic factors) will inform future searches for gene-environment interactions that modify CF lung function. Identification of such interactions should provides clues into disease pathophysiology with both a stimulus (unique exposure) and target (gene), which may lead to individualized therapies for CF and other chronic respiratory diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the CF Foundation for use of the CF Foundation Data Registry, Ase Sewall, B.S., Monica Brooks, B.S., the staff at the Data Registry, Nulang Wang, B.S. and Sarah Ritter, B.A. for CFTR genotyping, Michal Kulich, Ph.D. for providing conversion programs for CF-specific percentile estimates for FEV1 (served as a biostatistician for Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutic Development Network Coordinating Center), Rita McWilliams, Ph.D., Julie Hoover-Fong, M.D., Ph.D., and Ada Hamosh, M.D., M.P.H., for designing questionnaires, and most importantly the patients with CF and their families, research coordinators, nurses, and physicians who are participating in the CF Twin and Sibling Study.

Supported by NHLBI grant HL68927 and CF Foundation funding (CUTTIN06P0 and COLLAC09A0).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- (1).Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–73. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kerem B, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, Markiewicz D, Cox TK, Chakravarti A, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis. Science. 1989;245:1073–80. doi: 10.1126/science.2570460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Koch C, Cuppens H, Rainisio M, Madessani U, Harms H, Hodson M, et al. European Epidemiologic Registry of Cystic Fibrosis (ERCF): comparison of major disease manifestations between patients with different classes of mutations. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001 Jan;31:1–12. doi: 10.1002/1099-0496(200101)31:1<1::aid-ppul1000>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kerem E, Corey M, Kerem B-S, Rommens J, Markiewicz D, Levison H, et al. The relation between genotype and phenotype in cystic fibrosis--analysis of the most common mutation (deltaF508) N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1517–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011293232203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Cystic Fibrosis Genotype/Phenotype Consortium Correlation between genotype and phenotype in cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1308–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199310283291804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry Annual Data Report 2006. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- (7).Vanscoy LL, Blackman SM, Collaco JM, Bowers A, Lai T, Naughton K, et al. Heritability of lung disease severity in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 May 15;175:1036–43. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1164OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Mekus F, Ballmann M, Bronsveld I, Bijman J, Veeze H, Tummler B. Categories of deltaF508 homozygous cystic fibrosis twin and sibling pairs with distinct phenotypic characteristics. Twin Res. 2000 Dec;3:277–93. doi: 10.1375/136905200320565256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Smyth A, O’Hea U, Williams G, Smyth R, Heaf D. Passive smoking and impaired lung function in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 1994;71:353–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.71.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Beydon N, Amsallem F, Bellet M, Boule M, Chaussain M, Denjean A, et al. Pulmonary function tests in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Oct 15;166:1099–104. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200205-421OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Campbell PW, III, Parker RA, Roberts BT, Krishnamani MR, Phillips JA., III Association of poor clinical status and heavy exposure to tobacco smoke in patients with cystic fibrosis who are homozygous for the F508 deletion. J Pediatr. 1992 Feb;120:261–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Rubin BK. Exposure of children with cystic fibrosis to environmental tobacco smoke. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:782–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009203231203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Collaco JM, Vanscoy L, Bremer L, McDougal K, Blackman SM, Bowers A, et al. Interactions between secondhand smoke and genes that affect cystic fibrosis lung disease. JAMA. 2008 Jan 30;299:417–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.4.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).O’Connor GT, Quinton HB, Kneeland T, Kahn R, Lever T, Maddock J, et al. Median household income and mortality rate in cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 2003 Apr;111:e333–e339. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.e333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Schechter MS, Margolis PA. Relationship between socioeconomic status and disease severity in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1998 Feb;132:260–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70442-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Schechter MS, Shelton BJ, Margolis PA, Fitzsimmons SC. The association of socioeconomic status with outcomes in cystic fibrosis patients in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 May;163:1331–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.9912100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Curtis JR, Burke W, Kassner AW, Aitken ML. Absence of health insurance is associated with decreased life expectancy in patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997 Jun;155:1921–4. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.6.9196096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Goss CH, Newsom SA, Schildcrout JS, Sheppard L, Kaufman JD. Effect of ambient air pollution on pulmonary exacerbations and lung function in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004 Apr 1;169:816–21. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-779OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Wexler NS, Lorimer J, Porter J, Gomez F, Moskowitz C, Shackell E, et al. Venezuelan kindreds reveal that genetic and environmental factors modulate Huntington’s disease age of onset. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Mar 9;101:3498–503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308679101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Rosenstein BJ, Cutting GR. The diagnosis of cystic fibrosis: A consensus statement. J Pediatr. 1998;132:589–95. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kulich M, Rosenfeld M, Campbell J, Kronmal R, Gibson RL, Goss CH, et al. Disease-specific Reference Equations for Lung Function in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 Oct 1;172:885–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200410-1335OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. 4th ed. Longman; Essex: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Falconer DS. The inheritance of liability to diseases with variable age of onset, with particular reference to diabetes mellitus. Ann Hum Genet. 1967 Aug;31:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1967.tb01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Dorfman R, Sandford A, Taylor C, Huang B, Frangolias D, Wang Y, et al. Complex two-gene modulation of lung disease severity in children with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2008 Mar 3;118:1040–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI33754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Muhlebach MS, MacDonald SL, Button B, Hubbard JJ, Turner ML, Boucher RC, et al. Association between mannan-binding lectin and impaired lung function in cystic fibrosis may be age-dependent. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006 Aug;145:302–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Quittner AL, Modi A, Boyle MP. The role of independence in daily functioning for adults with cystic fibrosis: Results from the adult data for understanding lifestyle and transitions (ADULT) survey. 31 ed. 2008. p. 445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]