Abstract

Background

There are many techniques that can be used to reconstruct anomalous breast volume in Poland’s syndrome, but repair of the stigmatizing deformities such as the transverse skin fold in the anterior axillary pillar, infraclavicular depression, and anomalous breast contours continues to be a challenge. This study aimed to demonstrate the superior results of laparoscopically harvested omentum flap to achieve these aesthetic improvements.

Methods

Patients with Poland’s syndrome from a clinical database were identified and their outcomes were studied.

Results

In 15 consecutive patients with Poland’s syndrome, the breast contour, the anterior axillary pillar, and the infraclavicular depression were treated with omentum flap and evaluated. Silicone implants were used beneath the flap in 80% of cases to improve symmetry. Flap consistency was similar to that of the natural breast and only a small incision in the breast fold was needed. The flap is extremely malleable, adapts to irregular surfaces, and has a long vascular pedicle. It does not leave a scar at the donor site as muscular flaps do. The omentum can repair small irregularities in breast contour, achieving a natural result different from all other flaps. Due to its malleability, it is possible to reconstruct even the extension to the axillary pillar, which is impossible with all other techniques.

Conclusions

The omentum flap technique is a means of repairing the deformities caused by Poland’s syndrome and improves the aesthetic result with outcomes that seem superior to any other reconstructive option.

Keywords: Breast asymmetry, Breast contour, Anterior axillary pillar, Poland’s syndrome, Breast deformities, Omentum flap, Laparoscopically harvested omentum flap

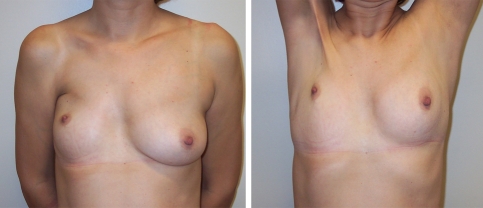

In patients with Poland’s syndrome, some of the most uncomfortable physical alterations are the transverse skin fold in the anterior axillary pillar (caused by absence or hypoplasia of the pectoral muscles), infraclavicular depression, and an anomalous breast contour [1] (Fig. 1). The resulting aesthetic malformation is difficult to hide, leads to thoracic asymmetry, and imposes significant psychological trauma and social withdrawal in both men and women.

Fig. 1.

The stigmatizing deformities of Poland’s syndrome: the transverse skin fold in the anterior axillary pillar, the infraclavicular depression, and the anomalous breast contour

Alfred Poland, in 1841, presented a 27-year-old patient with the absence of the unilateral pectoralis major muscle and syndactyly on the same side [2]. Patients with Poland’s syndrome may present with numerous ailments such as the absence of the sternal-costal portion of the pectoralis major muscle and upper-extremity deformities that include hypoplasia, brachysyndactyly, and syndactyly. Various other muscles may also be affected, e.g., pectoralis minor, latissimus dorsi, serratus anterior, external oblique, and deltoid. Skeletal deformities such as partial agenesis of the ribs, sternum, and spine may occur. Breast hypoplasia or aplasia, nipple abnormalities, skin atrophy, and the absence of sweat glands and surrounding structures are other features [3–5].

In Poland’s syndrome, thoracic wall deformities are not as obvious at birth as hand deformities. However, when female patients reach adolescence, the thoracic deformity seems to become more evident as the absence or asymmetry of the developing breasts occurs. In male patients, although the breast does not develop in adolescence, the thoracic wall deformity causes great suffering, impairing social experiences and the use of bathing and sports clothes.

Expanders and implants, transposition of the latissimus dorsi muscle flap (when unaffected by the syndrome), and the rectus abdominis muscle flap when the latissimus dorsi is absent are options that have been proposed to reconstruct breast volume [1, 6–8]. These techniques may achieve excellent results depending on the degree of deformity, but aesthetic reconstruction of the anterior axillary pillar and the filling of the infraclavicular depression have been disappointing [1]. Moreover, an additional scar is left in the patient’s donor region of those muscular flaps. Besides a scar, the latissimus dorsi flap also leaves an additional deformity in the dorsal contour due to the absence of muscle filling the posterior axillary pillar. The effect of the absence of latissimus dorsi is subtle but it can be very uncomfortable when wearing certain clothes.

The laparoscopically harvested omentum flap can be considered an excellent reconstructive option that offers a very interesting aesthetic result to solve the problems in Poland’s syndrome [9].

Subjects and Methods

Since 1998, 15 Poland’s syndrome patients from a temporal historical series who presented severe hypomastia and agenesis of the pectoralis major muscle were treated with omentum flaps. The anterior axillary pillar was absent and there was infraclavicular depression that resulted in obvious anterior thoracic wall asymmetry. It was determined that local tissues were insufficient to cover adequately the implant chosen for breast volume reconstruction.

These patients were treated by a single surgeon (SSC) over a 12-year period. During this time, many improvements in devices and imaging technologies were incorporated into the technique, but the basics of the protocol remained the same. In the absence of specific contraindications for laparoscopy, patients were considered candidates for transposition of the omentum flap harvested by videolaparoscopy to treat these deformities in the breast and thoracic wall. Previous procedures that remove or compromise omentum viability, such as surgery or infection, were considered absolute contraindications. All patients were informed about the risks of the laparoscopic procedure and selected based on the perceived risk–benefit ratio.

The omentum flap is harvested using standard laparoscopic surgery techniques. Four ports are usually placed in the umbilical region, suprapubic region, and both lateral iliac fossa. CO2 pneumoperitoneum of 10–12 mmHg is maintained during the procedure (Fig. 2). Dissection of the flap is initiated by clamping and elevating the gastric wall (Fig. 3). The right gastroepiploic artery is isolated and preserved; the short gastric arteries are ligated along the greater curvature until the left gastroepiploic artery is reached (Fig. 4). The omentum should be disconnected from the transverse colon by a careful dissection to preserve the mesocolon vascularity (Fig. 5). The flap will be totally liberated when the left gastroepiploic artery is ligated adjacent to the left colic flexure. Finally, through a small incision in the inframammary fold, a subcutaneous tunnel is dissected until the costal border to open the aponeurosis in the medial line, toward the abdominal cavity. With the fingers, the omentum is pulled from the abdominal cavity to the breast region to allow passage and placement of the flap over the specific thoracic wall region (Figs. 6, 7, 8). This tunnel is placed to the left or right side of the round ligament, depending on the site that needs reconstruction. The location of the deformity is then dissected and filled in with the omentum flap, which is fixed in place. Both procedures are performed under video-assisted guidance.

Fig. 2.

Four ports are usually placed to harvest the omentum flap, with minimal scarring

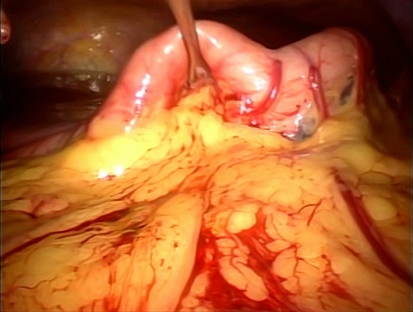

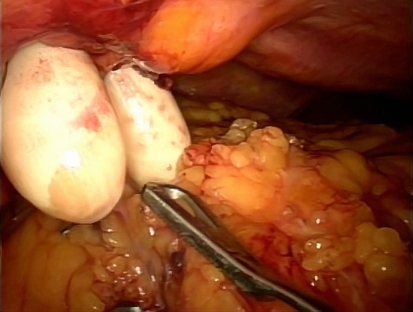

Fig. 3.

Elevation of the gastric wall

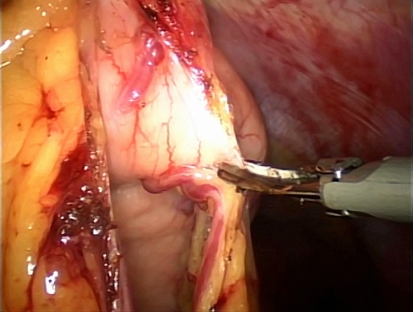

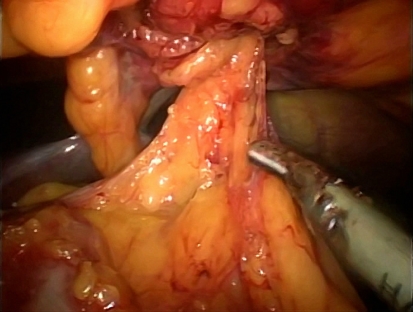

Fig. 4.

Ligations of the short gastric arteries along the great gastric curvature showing the preserved right gastroepiploic artery

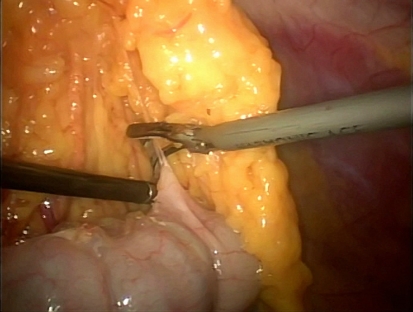

Fig. 5.

Liberation of the colon segment of omentum attachment

Fig. 6.

Using the fingers the omentum is pulled from the abdominal cavity to the breast region

Fig. 7.

Final position of the pedicle flap into the abdominal cavity, near the round ligament

Fig. 8.

Omentum flap on the thoracic wall

Results

Age, gender (M/F), side of the syndrome, use of complementary silicone implant in the breast, and the time it took to perform the laparoscopic dissection of the flap are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient details

| Patients | Age | Gender | Side | Prosthesis in the affected side | Operative time (min) | Postprandial discomfort | Hospital stay (days) | Contralateral breast intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | F | L | Yes | 360 | Yes | 2 | – |

| 2 | 19 | F | R | Yes | 390 | Yes | 3 | Mastopexy |

| 3 | 19 | F | R | Yes | 330 | Yes | 2 | Mastopexy |

| 4 | 19 | M | R | No | 220 | No | 2 | – |

| 5 | 18 | F | L | Yes | 290 | No | 1 | Prosthesis |

| 6 | 37 | F | R | Yes | 190 | Yes | 2 | – |

| 7 | 21 | F | R | Yes | 190 | No | 2 | Prosthesis |

| 8 | 24 | F | R | No | 160 | No | 3 | Reduction |

| 9 | 38 | F | L | Yes | 90 | Yes | 5 | – |

| 10 | 53 | F | L | Yes | 100 | Yes | 2 | – |

| 11 | 23 | F | L | Yes | 110 | Yes | 3 | Mastopexy |

| 12 | 35 | F | R | Yes | 80 | No | 2 | – |

| 13 | 25 | M | R | No | 110 | Yes | 2 | – |

| 14 | 22 | F | L | Yes | 130 | No | 1 | – |

| 15 | 20 | F | R | Yes | 110 | Yes | 3 | – |

Eighty-seven percent of the patients were female with a mean age of 26 years (range = 18–53). There was no specific predominance of one side. Eighty percent of the patients received ipsilateral silicone implants to complement breast volume and achieve symmetry.

The mean operative time for laparoscopic dissection of the flap in this group was 190 min (range = 80–390). The mean hospital stay was 2.3 days (range = 1–5), and patients resumed normal activities depending on individual treatment progress. Nine patients had postprandial discomfort and moderate gastric distension with spontaneous regression for 48 h after the procedure.

Breast reduction (6%), mastopexy (20%), and augmentation procedures (13%) of contralateral breasts were also performed in six patients to finalize equalization of both breasts (Table 1). There was no need for procedures in the other breast in 60% of the patients because they were satisfied with the initial result. Blood loss was insignificant in all cases and there were no conversions to open procedures or deaths.

There were no significant intraoperative complications such as omentum being unavailable because of adhesions or small size, vascular injury, or bowel injury, and there were no cases of wound infection, internal hernia, and loss of the flap or fat necroses during the postoperative period.

Because the omentum flap tissue is malleable, it is possible to correct particular details of the breast contour, an outcome impossible to achieve with any other technique (Fig. 9). Use of the omentum flap improves the breast contour, fills the infraclavicular depression, and reconstructs the anterior axillary pillar. When implants are employed underneath the flap, they provide appropriate concealment and a better quality coverage system that results in improved symmetry with the opposite hemithorax. No other flaps achieve the consistency of the breast-like omentum flap.

Fig. 9.

Photos in the left-hand column show a Poland’s syndrome patient who was treated with a single silicone implant which was insufficient to correct the absence of the right breast, the infraclavicular depression, and the unpleasant transverse sulcus in the axillary pillar. In the right-hand column, the same patient after laparoscopically harvested omentum flap transposition on the right side. The infraclavicular depression and the anomalous breast contour were concealed and the transverse sulcus minimized

Discussion

The laparoscopically harvested omentum flap procedure results in a shorter hospital stay, fewer complications, and a faster return to normal life compared with open procedures in all recent studies [9–15]. The omentum has been used in reconstructive surgery for more than 100 years. In 1888, Senn employed it to protect an intestinal anastomosis [16], and in 1963 Kirikuta [17] described use of the great omentum as a flap in cases of breast cancer surgery. In 1972, McLean and Buncke [18] described the omentum free flap, and in 1976, Arnold and Jurkiewicz [19] used the pedicled omentum in the reconstruction of the chest wall, including two patients with Halsted mastectomy by a one-stage reconstruction using transposed omentum to cover a silastic gel implant and to support an overlying skin graft.

Laparoscopic harvesting of the omentum was carried out for the first time by Saltz et al. in 1993 [14] to repair soft tissue defects in the knee. In 1996, Goes [13] used the laparoscopically harvested omentum flap in breast reconstruction after a skin-sparing periareolar mastectomy, opening the abdominal cavity in the epigastrium at the end of the procedure to transfer the omentum from the abdominal cavity to the thoracic region. In the same year, Costa [10] presented a totally closed videolaparoscopic procedure where the flap was dissected in the abdominal cavity and transposed through a subcutaneous tunnel to the thoracic wall; the procedure was also used to treat breast cancer patients. The excellent outcomes obtained with omentum flaps for the treatment of breast cancer sequels were the main reason this technique was used in patients with Poland’s syndrome. In 1998, for the first time, Costa [9] used the omentum flap to treat Poland’s syndrome deformities.

Numerous alternative treatments such as handmade expanders and implants, latissimus dorsi flaps, and rectus abdominals muscle flaps have been proposed to correct the most important deformities caused by this syndrome, but all have offered only a partial correction of the deformities, with poor aesthetic results [1, 6–8]. The laparoscopically harvested omental flap works much better than a fat graft that loses significant volume with time. In contrast, the omentum achieves sufficient volume with a single procedure, without the postoperative absorption and loss of transplanted volume; it even grows.

Use of the omentum flap, in our experience, offers the possibility to treat these deformities with excellent cosmetic results [9, 10, 13, 14] and repairs the thoracic wall and breast deformities caused by Poland’s syndrome, with superior outcomes compared to those of other reconstructive options. The advantages of the omentum flap are numerous and significant: it is extremely malleable, adapts easily to irregular surfaces, and has a long and reliable vascular pedicle. The flap measures approximately 25 × 35 cm and its volume varies according to patient size [20, 21]. In the first 6 months after the procedure, the omentum flap has a variable growth rate that needs to be considered when planning repair of the deformity.

Other important advantages of the omentum flap include its large absorption capacity, which reduces postoperative time during which drains are needed. Use of laparoscopy to harvest the flap offers minimal insult to the abdominal wall, ensuring a short and comfortable postoperative recovery period [11, 12, 15]. The resulting consistency is very similar to that of the contralateral breast, enabling more satisfactory repair of the anterior axillary pillar than any other reconstructive option.

A difficulty of this technique is that it is not possible to precisely determine the final omentum volume available while planning the reconstruction. Complementation of volume and equalization with the contralateral breast may be performed during the same surgical time or, even better, 4–6 months later when it is possible to take into consideration the spontaneous flap growth that always occurs after its transposition. The skeletal deformities that come with this syndrome may be minimized, but when they are very severe, they may still distort the aesthetic appearance of the thoracic wall and breasts, in same cases calling for another complementary procedure.

A review of all available literature about laparoscopically harvested omentum flaps indicates that there are no severe postoperative complications, a finding that is in agreement with the experience of our group.

Because of the great variability in the characteristics of the deformities in individuals, it is very difficult to establish objective parameters of comparison regarding aesthetic outcomes. Long-term evaluations might provide information about aesthetic results and patients’ satisfaction.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the aesthetic improvements offered by the omentum flap in the treatment of Poland’s syndrome enable reconstruction of the anterior axillary pillar as well as the filling in of the infraclavicular depression, providing a soft coverage system that is thick enough to conceal silicone implants used in breast reconstruction much better than all other techniques seem able to achieve.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Seyfer AE, Icochea R, Graeber GM. Poland’s anomaly. Natural history and long-term results of chest wall reconstruction in 33 patients. Ann Surg. 1988;208:776–782. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198812000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poland A. Deficiency of the pectoral muscles. Guy Hosp Rep. 1841;6:191–193. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bainbridge LC, Wright AR, Kanthan R. Computed tomography in the preoperative assessment of Poland’s syndrome. Br J Plast Surg. 1991;44:604–607. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(91)90099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobben JM, Robinson PH, van Essen AJ, van der Wiel HL, ten Kate LP. Poland anomaly in mother and daughter. Am J Med Genet. 1989;33:519–521. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320330423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez Aznar JM, Urbano J, Garcia Laborda E, Quevedo Moreno P, Ferrer Vergara L. Breast and pectoralis muscle hypoplasia. A mild degree of Poland’s syndrome. Acta Radiol. 1996;37:759–762. doi: 10.3109/02841859609177712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gatti JE. Poland’s deformity reconstructions with a customized, extrasoft silicone prosthesis. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39:122–130. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199708000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marks MW, Argenta LC, Izenberg PH, Mes LG. Management of the chest-wall deformity in male patients with Poland’s syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:674–678. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rintala AE, Nordstrom RE. Treatment of severe developmental asymmetry of the female breast. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1989;23:231–235. doi: 10.3109/02844318909075123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa SS (1998) Tratamento cirúrgico da Síndrome de Poland com omento transposto por videolaparoscopia. In: Mastologia. Foz do Iguaçu. AdXCBd, Brasil, p 186

- 10.Costa SS (1996) Uso do omento livre retirado por videolaparoscopia para reconstrução de mama. In: Reconstrutiva AdVEdSBdM, Anais do VIII Encontro da Sociedade Brasileira de Microcirurgia Reconstrutiva, vol 1. Sociedade Brasileira de Microcirurgia, Rio de Janeiro, p 5

- 11.Cothier-Savey I, Tamtawi B, Dohnt F, Raulo Y, Baruch J. Immediate breast reconstruction using a laparoscopically harvested omental flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1156–1163. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200104150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferron G, Garrido I, Martel P, Gesson-Paute A, Classe JM, Letourneur B, Querleu D. Combined laparoscopically harvested omental flap with meshed skin grafts and vacuum-assisted closure for reconstruction of complex chest wall defects. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58:150–155. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000237644.29878.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Góes JCS. Immediate reconstruction after mastectomy using a periareolar approach with an omental flap and mixed mesh support. Perspect Plast Surg. 1996;10:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saltz R, Stowers R, Smith M, Gadacz TR. Laparoscopically harvested omental free flap to cover a large soft tissue defect. Ann Surg. 1993;217:542–546. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199305010-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaha H, Inamine S, Naito T, Nomura H. Laparoscopically harvested omental flap for immediate breast reconstruction. Am J Surg. 2006;192:556–558. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irons GB, Witzke DJ, Arnold PG, Wood MB. Use of the omental free flap for soft-tissue reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1983;11:501–507. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198312000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiricuta I. The use of the great omentum in the surgery of breast cancer. Presse Med. 1963;71:15–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLean DH, Buncke HJ., Jr Autotransplant of omentum to a large scalp defect, with microsurgical revascularization. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;49:268–274. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jurkiewicz MJ, Arnold PG. The omentum: an account of its use in the reconstruction of the chest wall. Ann Surg. 1977;185:548–554. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197705000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnold PG, Hartrampf CR, Jurkiewicz MJ. One-stage reconstruction of the breast, using the transposed greater omentum. Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;57:520–522. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197604000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das SK. The size of the human omentum and methods of lengthening it for transplantation. Br J Plast Surg. 1976;29:144–170. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(76)90045-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]