Abstract

Introduction

Well-organised clinical cooperation between health and social services has been difficult to achieve in Sweden as in other countries. This paper presents an empirical study of a mental health coordination network in one area in Stockholm. The aim was to describe the development and nature of coordination within a mental health and social care consortium and to assess the impact on care processes and client outcomes.

Method

Data was gathered through interviews with ‘joint coordinators’ (n=6) from three rehabilitation units. The interviews focused on coordination activities aimed at supporting the clients’ needs and investigated how the joint coordinators acted according to the consortium's holistic approach. Data on The Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN-S) showing clients’ satisfaction was used to assess on set of outcomes (n=1262).

Results

The findings revealed different coordination activities and factors both helping and hindering the network coordination activities. One helpful factor was the history of local and personal informal cooperation and shared responsibilities evident. Unclear roles and routines hindered cooperation.

Conclusions

This contribution is an empirical example and a model for organisations establishing structures for network coordination. One lesson for current policy about integrated health care is to adapt and implement joint coordinators where full structural integration is not possible. Another lesson, based on the idea of patient quality by coordinated care, is specifically to adapt the work of the local addiction treatment and preventive team (ATPT)—an independent special team in the psychiatric outpatient care that provides consultation and support to the units and serves psychotic clients with addictive problems.

Keywords: coordination, integrated care planning, mental health care

Introduction and problem statement

Poorly linked health and social care services for mental health clients have been reported in many countries and different approaches for better coordination are being pursued [1]. ‘Integrated care’ has become a component of health and social care reform across Europe, defined as “bringing together inputs, delivery, management and organisation of services related to diagnosis, treatment and care, rehabilitation and health promotion” [2, p. 7]. However, evidence indicates that there is a gap between policy intent and practical application [3]. Putting models of integrated care into practice is challenging, and progress toward integrated care has been limited. ‘Under-coordination’ has been shown to increase risks, adverse events and increases costs [4]. Some of the failings are related to unclear responsibilities for the patient and their problems, which result in information loss as the patient navigates the system [3]. Other failings are related to poor communication with the patient and between health and social care providers treating patients for one condition without recognising other needs or conditions, thereby undermining the overall effectiveness of treatment [3].

Efforts to describe the fragmentation problem and formulate solutions seem complex, partly due to a lack of shared definitions of terms like coordination and continuity of care. A multidisciplinary review demonstrates that concepts like coordination of care, continuum of care, discharge planning, case management, integration of services, and seamless care are frequently used synonymously [5]. More recently, integration has been described as an elastic term [6, 7]—a circumstance that has implications for both patient safety and continuity of care in complicating evaluation efforts and constructive communication. To further illustrate the complexity, integration is often pictured along a continuum of inter-organisational relations, extending from a complete autonomy of organisations through intermediate forms of consultation and consolidation to a merger of organisations [7, 8]. Parallel to that, distinctions among linkage, coordination and full integration, where linkage allows individuals with mild to moderate or new disabilities to be cared for appropriately in systems that serve the whole population without having to rely on outside systems for special relationships are also made [9]. At the second level, coordination refers to explicit structures and individual managers installed to coordinate benefits and care across acute and other systems. In comparison, coordination is a more structured form of integration than linkage, but it still operates largely through the separate structures of current systems. Finally, full integration creates new programs or units where resources from multiple systems are pooled.

Well-organised cooperation between health and social services has been difficult to achieve in Sweden, as in other countries. Within mental health care, where flexible, personalised, and seamless care is needed, clients are regularly seen by several professionals in a wide variety of organisations and sites, which often causes fragmentation of care and gaps in the continuity in care. Case management is often described as a method for coordination, integration and allocation of resources for individualised care for mental health clients [10, 11]. Case management is well-established as a major component of psychiatric treatment in most Western countries and has been for up to 20 years in some areas [10]. Coordination in networks is described as a structured type of integration operating largely through existing organisational units aimed at coordination of various health services, to share clinical information, and to manage the transition of clients between care units [12]. Network structures include, but also reach beyond, linkages, coordination, or task force action. Unlike networks, in which people are only loosely linked to each other, in a network structure people must actively work together to accomplish what they recognize as a problem or issue of mutual concern [13].

As a basic assumption, organisational network structures alone are not sufficient to produce integrated practice, but still, well-organised coordination of care may help to improve care quality, patient safety, health system efficiency, and patient satisfaction [1]. Today, the relationships in mental health care are typically established with a team rather than a single provider and coordination often extends to social services such as housing and daytime activities where care coordinators are appointed to facilitate both health and social services [5]. Identified as a unique feature, still topical in mental health care, is the continuity of contacts, where the care team maintains contact with clients, monitors their progress, and facilitates access to services [14].

The aim of this study was to document and describe a well-established coordination structure within a mental health and social care consortium but also to explore these structures impact on care organisation and client outcomes.

Research questions

A review of the research identifies a need to further increase our knowledge about how to economically and resourcefully organise coordination networks for improved mental health services and identify what factors are helping and hindering. To meet that objective, identification of relevant indicators of end results for clients was included. Specifically, this study addresses the following questions:

What main coordination elements constitute the Södertälje mental health and social care consortium?

Which factors emerge as most essential for helping and hindering coordination?

To what extent has the integrated model influenced the clients’ satisfaction?

Theory and methods

Phase A: Describing the formation of the mental health and social care consortium

Method

In 2007, Medical Management Centre (MMC) at Karolinska Institute started a longitudinal study of innovations in Stockholm health care. The design was a multiple case study focusing on 12 local innovation practices within Stockholm County. The program was implemented in accordance with the core elements of action research [15, 16]. Action research is well suited to help solving real-life problems at hand. In order to meet the problem-solving intention, action research should encompass a conjunction of research, action and democratic participation [17]. One of the 12 case studies covered the Södertälje mental health and social care consortium.

The setting for the study: The Södertälje mental health and social care consortium

The Södertälje mental health and social care consortium is a cooperative model involving a county psychiatry clinic and the municipal social services and sheltered housing and rehabilitation units. Since 1996 the consortium has made major changes for better care across unit boundaries to chronic mental health clients. Some of the key changes made to develop the cooperative model were the formation of a joint steering group in 1996 for representatives from both the county psychiatry clinic and the municipal social services. Another change was the implementation of standardised assessments and follow-up of individual needs and service outcomes using The Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) scale. The assessment scale, introduced in 1997, is a 22-item measure for assessment of health and social needs of people with mental health problems [18, 19]. A third key change was the introduction of ‘joint coordinators’ from both the county psychiatry clinic and the local municipal social services. The joint coordinators, based in the same office, aim at shared coordination for each client. The main actions to bring about the innovation content changes described above were:

actions to formulate a shared vision for the service,

actions to prepare a plan and present this to different local and county committees,

actions to apply for and use national capital finance available for mental health developments,

actions to build and start services at three shared rehabilitation units.

Today, the majority of the clients within the consortium are diagnosed with schizophrenia and a few are diagnosed with schizoaffective psychosis or passing psychosis. A small number of clients have bipolar disorders and functional disorders. The core of the consortium consists of three daytime rehabilitation units. Both the county psychiatry clinic and the municipal social services share a holistic approach to clients needs.

The initial phase of the case study investigated the origin of the consortium, explicitly the basic ideas and actions that guided the local change agents’ first steps in the development work. Structured interviews with key persons (n=10) at various organisational levels helped to reconstruct the program theory and show important changes and factors both helping and hindering the continuous development work.

Coordination in networks for improved mental health service

In Södertälje, each client within the consortium has one coordinator from each service. The joint coordinators have central tasks in helping chronic mental health clients to recover for example through assessments of needs, which is an essential measure for the establishment of rehabilitation plans. Nurses, occupational therapists and rehabilitation assistants primarily hold the role as coordinator. Central in this case, the mental health coordination is strongly characterised by activities where joint coordinators are appointed to facilitate both mental health and social services. Since medical and social rehabilitation often overlap within the mental health consortium, staff activities are organised in networks rather than conventional client pathways [20, 21]. This specific form of integration model includes both seamless care arrangements and health care networks and shares some elements both with assertive community treatment [22] and case management [23, 24].

Phase B: Details of clinical coordination

Method

The case study design

A multiple-case study approach [25] was applied for investigation into the joint coordinators prerequisites to take action and provide care according to the consortium's holistic approach to client needs. The benefit of multiple cases was considered and replication logic was followed [25]. A series of structured interviews with joint coordinators from each of the three rehabilitation units was performed in 2009. The aim of the interviews was to explore the joint coordinators view on current conditions and their prerequisites to take action according to the consortium's idea of prioritising the clients' needs. CAN-data reflecting the clients’ satisfaction with help received from both professional services and relatives was applied as an outcome indicator for the joint coordinators work on integrated mental health care.

Selection of coordinators

The first line managers at each rehabilitation unit administered the selection of coordinators who were selected on the basis on their practical ability to participate in the interviews. A total number of six joint coordinators divided into three rehabilitation units were sampled. Four of these were senior coordinators (>5 years experience) and two had shorter experience in the role (1–5 years). The variation was considered a strength given the purpose of the study was to provide a broad description of the coordinators view on their current conditions.

Interview protocol

The design of the interview protocol was based on five fundamental areas of need defined as; daytime activities, psychotic symptoms, contact with authorities and financial issues, interaction with family and relatives, drug and alcohol. These themes were identified as fundamental to the clients’ well-being and were also included as separate items in the CAN-scale. The interviews aimed at exploring current network-based interactions but also to identify factors both helping and hindering the current work. Minutes of meetings and documents describing the development work gathered all through the case study helped to structure the interview protocol. The protocol and the thematic list of central areas of need was assessed and approved by a reference group established to support the researchers work.

Interview procedure

All together, three pair interviews with six joint coordinators were completed at the rehabilitation units. The time consumed varied between 60 and 90 minutes. All coordinators authorised the researcher (JH) to record the interview session with a digital recorder. Added to that, the researcher made written notes during the session. All coordinators were informed about the purpose of the task and the researcher’s assurance of integrity and confidentiality (informed consent).

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed by procedures following basic content analysis [26–28]. Interview data were then structured into categories following the five areas of need. Descriptive networks illustrating direct and indirect planning activities were produced to represent the coordinated care process. Factors described as helping and hindering the coordination was identified. Based on common themes and emergent patterns in the interview data, quotations were selected and translated from Swedish to English. Conclusions were then formulated and reported back to the coordinators via the study reference group.

Based on the main themes in the interview protocol, five corresponding items in the CAN-scale were identified and selected for outcome measure reflecting the clients’ experience of the Södertälje mental health and social care consortium. The items were; daytime activities, medical supervision, money, interaction with family and relatives, drug and alcohol. Group level data on clients’ self-assessments covering the years 1997/98, 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2008 and were applied as outcome indicators for integrated mental health care. The analysis included all available self-assessments made by clients in the mental health consortium during the period (n=1262). Variables like gender, age, previous admissions and length of contact with services have deliberately been omitted from the analysis. The analysis focused on the clients’ self-assessments regarding their satisfaction with help received from the joint coordinators. All documents were archived in a case study database together with transcribed interviews, minutes of meetings and case study notes.

Ethical considerations

This study was ethically approved by the regional ethical review board in Stockholm at Karolinska Institute, Sweden. In addition, all program activities described were approved by the participating organisation and the data gathering followed The American Psychological Association's ethical principles and code of conduct.

Results

The result section begins with a description built from the interviews with the joint coordinators on planning activities performed within the consortium. The interview findings is organised in five themes (A–E). Then findings are presented about the clients’ self-assessments regarding satisfaction with help received from the coordinators.

Interviews with joint coordinators

Theme A: Daytime activities. The coordinators primarily mentioned contacts with practice planners, the preparatory group, employers and the Swedish Social Insurance Agency as central for coordination of daytime activities. Contacts with physicians and relatives were only mentioned on a few occasions. Factors helping the current daytime activities included the practice planner, which was described as a central function by the coordinators at both unit A and C:

“Well yes, I do visits to workplaces. Sometimes on my own, sometimes together with the practice planner whom is the one identifying and customising the training place. We often ask the client what they find interesting and motivating. For example, one of my clients is interested in animals so recently we arranged a training place in a nearby pet shop. Our practice planner is really good at finding good matches”.

Continuous assessment of needs using the CAN-scale were mentioned at unit B. Cooperation with a nearby municipality was described as problematic by unit A. Lack of daytime activities for elderly clients (>65 years) were addressed as a barrier to the coordination work at unit B. Unclear communication with the Swedish Social Insurance Agency was mentioned by unit C.

Theme B: Psychotic symptoms. Regarding both direct and indirect planning activities related to psychotic symptoms, the coordinators primarily mentioned interactions with physicians, social workers and staff at the addiction treatment and preventive team (ATPT) an independent special team in the psychiatric outpatient care that provides consultation and support to the units and serves psychotic clients with addictive problems. Contacts with relatives were mentioned on a few occasions. Flexible planning routines was mentioned as a strength at unit A. Continuous contact with clients were described as a factor helping the coordination work at unit B. Shared responsibilities and joint coordinators were mentioned as a strength at unit C. Regarding barriers to the coordination work, unclear roles were mentioned at unit A. Unit B did not describe any current condition hindering the coordination work, but unit C did comment on the limited access to medical records:

“That is a problem. I work in the council next to staff from the municipality and I do have access to our physicians’ record notes. But my colleague doesn’t have access to the same medical record system. I do think we should have a shared system because the risk of errors and mistakes will then be much smaller. Today, I think it is important for me to inform my colleague about our clients’ medical status to avoid contacts with aggressive clients”.

Theme C: Authorities and financial issues. The coordinators primarily mentioned contacts with lawyers and the Swedish Social Insurance Agency as centrally related to contact with authorities and help with financial issues. Contacts with physicians and relatives were only mentioned on a few occasions. Factors helping current coordination activities mainly covered broad contacts within the society, here exemplified by the coordinators at unit A:

“We keep in touch and communicate with various authorities like lawyers for debt collection, the count administrative court and even the district court. All contacts start from our clients needs. Sometimes this is problematic due to unclear roles and boundaries. It is not always clear what to do because we have our tentacles in so many places. There is no clear cut boundary between Stockholm council and the municipality and sometimes one have to stop and ask if this really is within my area of competence”.

Preventive measures and personal skills to identify early signals indicating financial problems for clients were described as strengths at unit C. Inflexible authorities and unclear roles were addressed as a barrier to the coordination at unit A. Work overload on legal representatives were described as a hinderance at unit B. No barriers were mentioned at unit C.

Theme D: Interaction with family and relatives. The coordinators primarily described the network meetings and interactions with associations for relatives including education. The local unit for recently hospitalised clients was also frequently mentioned as a central instance. Concerning factors helping the coordination work on interaction with family and relatives, no helping circumstances were made explicit at unit A. The coordinators at unit B and C mentioned the network meetings and support from the local unit of recently hospitalised clients as helpful cases. Regarding barriers, low communication with relatives was mentioned at unit A and B:

“I wish there were more communication with relatives and that there was a stronger network surrounding our clients. Something bigger than us as coordinators, that is one thing I would like to improve but I don’t think we have any methods for that so it is hard for me to say how to do it in practice. One objective this year and the next are to invite relatives more often to our CAN-assessment sessions”.

Theme E: Drug and alcohol. Regarding both direct and indirect planning activities related to drug and alcohol abuse, the coordinators primarily mentioned interactions with the addiction treatment and preventive team (ATPT). Interactions with relatives were only mentioned in exceptional cases. With reference to factors helping the coordination work, some emergent patterns become evident—all units described the ATPT as a central instance:

“We have had a close and well-built cooperation standing for many years with the addiction treatment and preventive team. Today, we do have some clients registered here at our rehabilitation unit, which we, for some period of time, transfer to the local psychiatric addictive team for careful drug or alcohol treatment. After that, they return to our rehabilitation unit.

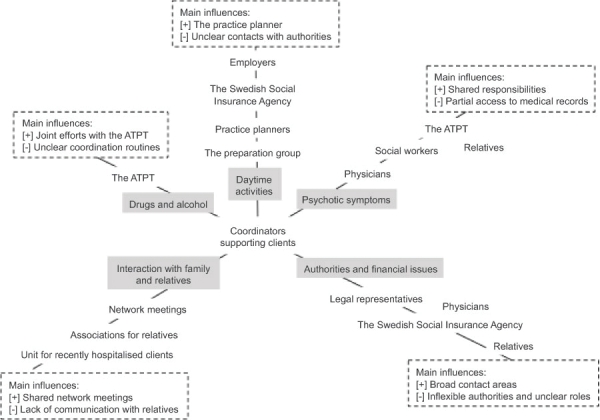

Neither unit A nor B expressed any factors hindering the coordination work related to drug and alcohol. The coordinators at unit C mentioned unclear routines, which in turn indicate role ambiguity. Figure 1 summarises the main interview findings.

Figure 1.

Central planning activities and resources arranged in a network.

In Figure 1, central planning activities and resources are organised along the five areas of need summarising identified main factors helping and hindering the coordination. The endpoints of each axis summarise identified helping aspects and barriers. Among helping aspects, a common denominator related to joint efforts and shared responsibilities manifest. Regarding barriers, a common denominator related to unclear roles and routines became dear. The ambiguity was described both in relation to internal contacts with colleagues and also associated to external contact with authorities.

The Camberwell Assessment of Need

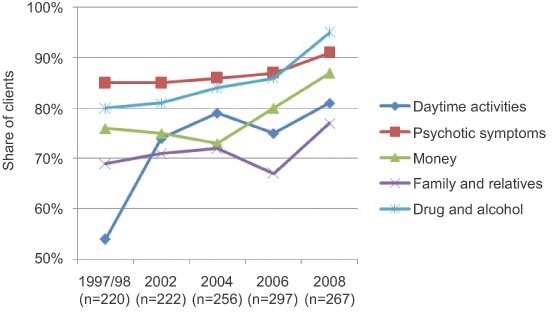

Data on The Camberwell Assessment of Need scale reflecting the clients’ satisfaction was used to assess the set of outcomes. Figure 2 summarises the clients’ self-assessments regarding their satisfaction with the help received from the coordinators.

Figure 2.

CAN data reflecting client satisfaction with help received from the joint coordinators 1997/98–2008. Due to missing data, 2000 is left out.

Figure 2 shows the results on 1262 clients’ self-ratings regarding perceived satisfaction with help received. Clients without any self-reported needs have been omitted from the summary above. Comparing the clients’ self-ratings 1997/98 and 2008, development on all five areas becomes clear; daytime activities (+27%), psychotic symptoms (+6%), money (+11%), interaction with family and relatives (+8%), drug and alcohol (+15%). Overall, the results show that the number of clients satisfied with the help received has consistently increased during the given case period.

Discussion

The addiction treatment and preventive team (ATPT) within the psychiatric outpatient care was described as a central element by all coordinators. As indicated by others [29, 30] the observed results give strength to the importance of incorporating special teams in mental health care. Based on the general characteristics of the ATPT, the element might be important to include in other mental health services trying to achieve proper integration [31]. On the negative side, context factors such as financial savings, role ambiguity and unclear guidelines were described as hindering circumstances in the current situation. The factors contributing and explaining this are worth closer examination and more research. For instance, inflexible authorities and unclear roles were addressed as a barrier to the coordination and, as identified elsewhere, this type of relations and interaction between governmental levels in a multi-level governance system affect public organizations, their tasks, functioning and autonomy [32]. The findings also indicate that the current system for medical records unavailable for municipal staff might result in redundant administrative work. Implementation of shared medical records may help to strengthen the consortium's holistic approach and also contribute to the important aspect of building trust in inter-organisational collaboration and care coordination [33]. Regarding data validity, the selection of coordinators via the first line managers entails the risk of positive sampling but the observed results indicate no or little such bias since both strengths and weaknesses were identified at all units.

Another finding was that the number of clients satisfied with the help received has consistently increased during the given case period. The observed CAN results on client satisfaction with help received during the examined period lend strong support for progression on integrated staff activities. It is likely to assume that the CAN results reflect the introduction and development of joint coordinators in 1997/98 but more research on mechanism explaining the outcome is still needed. The applied study design was limited in identifying and separating other changes likely to have had an influence the observed CAN outcome but the study was able to identify structural and process changes which make the observed client outcomes likely. As regards aspects of internal data validity, the observed CAN results converge with the interview findings and the embedded idea of successive advances within the mental health consortium.

Conclusions

Well-organised cooperation between health and social services has been difficult to achieve in Sweden and elsewhere. Given the study aim, to document and describe a well-established coordination structure within a mental health and social care consortium, and to explore these structures impact on care organisation and client outcomes, this study has gone someway towards describing how to develop network structures for coordination. This paper described areas where there was some evidence of effective care coordination. Factors that help and hinder care coordination were identified, suggesting elements to be included in further research. The research also identified issues for further development—one lesson for current policy on integrated health care is that joint coordinators for each client may be suited to some situations where full structural integration is not possible. Another lesson, based on the idea of improved patient quality through coordinated care, is to adapt the core work of the local addiction treatment and preventive team for psychiatric outpatient care.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study (Innovation Implementation Systems for Better Health, application A2007-032) has been allocated by VINNVÅRD, a joint research foundation set up by The Vårdal Foundation, VINNOVA (Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems), The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions and The Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs.

Contributor Information

Johan Hansson, PhD, Senior Researcher, Medical Management Centre (MMC), Karolinska Institute, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden.

John Øvretveit, PhD, Professor of Health Innovation Implementation and Evaluation, Director of Research, Medical Management Centre (MMC), Karolinska Institute, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden.

Marie Askerstam, MSc, Head of Section, Psychiatric Centre Södertälje, Healthcare Provision, Stockholm County (SLSO), SE-152 40 Södertälje, Sweden.

Christina Gustafsson, Head of Social Psychiatric Service in Södertälje Municipality, SE-151 89 Södertälje, Sweden.

Mats Brommels, MD, PhD, Professor in Healthcare Administration, Director of Medical Management Centre (MMC), Karolinska Institute, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden.

Reviewers

Roslyn Sorensen, BSoc Studies (USyd), MBA (UC), PhD (UNSW), Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery and Health, Broadway NSW, Australia

Two anonymous reviewers

References

- 1.Reilly S, Challis D, Donnelly M, Hughes J, Stewart K. Care management in mental health services in England and Northern Ireland: do integrated organizations promote integrated practice? Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2007;12(4):236–41. doi: 10.1258/135581907782101633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gröne O, Garcia-Barbero M. Integrated care: A position paper of the WHO European office for integrated health care services. International Journal of Integrated Care 2001;1, ISSN 1568-4156. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd J, Wait S. A guide for policymakers. London: Alliance for Health and the Future; 2006. Integrated care. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Øvretveit J. A review of evidence of which improvements to quality reduce costs to health service providers. London: The Health Foundation; 2009. Does improving quality save money? [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. British Medical Journal. 2003;327:1219–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacAdam M. Frameworks for integrated care for the elderly: a systematic review. Ontario: Canadian Policy Research Networks Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Axelsson R. Integration and collaboration in public health—a conceptual framework. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2006;21(1):75–88. doi: 10.1002/hpm.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hudson B, Hardy B, Henwood M, Wistow G. In pursuit of inter-agency collaboration in the public sector: what is the contribution of theory and research? Public Management. 1999;1(2):235–60. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leutz W. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. The Milbank Quarterly. 1999;77(1):77–110. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith L, Newton R. Systematic review of case management. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41(1):2–9. doi: 10.1080/00048670601039831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns T, Catty J, Dash M, Roberts C, Lockwood A, Marshall M. Use of intensive case management to reduce time in hospital in people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-regression. British Medical Journal. 2007;335(7615):336–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39251.599259.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahgren B, Axelsson R. Evaluating integrated health care: a model for measurement. doi: 10.5334/ijic.134. International Journal of Integrated Care 2005 Aug 31;5 [cited 2010 3 August]. Available from: http://www.ijic.org/. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keast R, Mandell MP, Brown K, Woolcock G. Network structures: working differently and changing expectations. Public Administration Review. 2004;64(3):363–71. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson S, Prosser D, Bindman J, Szmukler G. Continuity of care for the severely mentally ill: concepts and measures. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1997;32(3):137–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00794612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McIntyre A. Participatory action research. London: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall P, Willson P, Salas K, McKay J. Action research in practice: issues and challenges in a financial services case study. Qualitative Report. 2010;15(1):76–93. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenwood DJ, Levin M. Introduction to action research: social research for social change. 2nd edition. London: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phelan M, Slade M, Thornicroft G, Dunn G, Holloway F, Wykes T, et al. The Camberwell Assessment of Need: the validity and reliability of an instrument to assess the needs of people with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;167(5):589–95. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Najim H, McCrone P. The Camberwell assessment of need: comparison of assessments by staff and patients in an inner-city and a semi-rural community area. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2005;10(2):13–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Øvretveit J. Coordinating community care—multidisciplinary teams and care management. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Øvretveit J, Mathias P, Thompson T. Interprofessional working for health and social care. Basingstoke: MacMillan; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson S. So what shall we do about assertive community treatment? Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale. 2008;17(2):110–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziguras SJ, Stuart GW. A Meta-Analysis of the effectiveness of mental health case management over 20 years. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51(11):1410–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.11.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burns T. Case management and assertive community treatment: what is the difference. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2008;17(2):99–105. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00002761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 4th edition. London: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber RP. Basic content analysis. 2nd edition. London: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverman D. Doing qualitative research. 2nd edition. London: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data: methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction. 3rd edition. London: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Killaspy H, Bebbington P, Blizard R, Johnson S, Nolan F, Pilling S. The REACT study: randomised evaluation of assertive community treatment in north London. Bristish Medical Journal. 2006;332(7545):815–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38773.518322.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Sullivan J, Powell J, Gibbon P, Emmerson B. The resource team: an innovative service delivery support model for mental health service. Australasian Psychiatry. 2009;17(5):371–4. doi: 10.1080/10398560802573701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM. Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness: a randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(9):861–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lægreid P, Verhoest K, Jann W. The governance, autonomy and coordination of public sector organizations. Public Organization Review. 2008;8(2):93–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vangen S, Huxham C. Nurturing collaborative relations: building trust in inter-organizational collaboration. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science. 2003;39(1):5–31. [Google Scholar]