Abstract

Biomolecular recognition is versatile, specific, and high affinity—qualities that have motivated decades of research aimed at adapting biomolecules into a general platform for molecular sensing. Despite significant effort, however, so-called “biosensors” have almost entirely failed to achieve their potential as reagentless, real-time analytical devices; the only quantitative, reagentless biosensor to achieve commercial success so far is the home glucose monitor, employed by millions of diabetics.

The fundamental stumbling block that has precluded more widespread success of biosensors is the failure of most biomolecules to produce an easily measured signal upon target binding. Antibodies, for example, do not change their shape or dynamics when they bind their recognition partners, nor do they emit light or electrons upon binding. It has thus proven difficult to transduce biomolecular binding events into a measurable output signal—particularly one that is not readily spoofed by the binding of any of the many potentially interfering species in typical biological samples. Analytical approaches based on biomolecular recognition are therefore mostly cumbersome, multistep processes relying on analyte separation and isolation (such as western blots, ELISA, and other immunochemical methods); these techniques have proven enormously useful, but are limited almost exclusively to laboratory settings.

In this Account, we describe how we have refined a potentially general solution to the problem of signal detection in biosensors, one that is based on the binding-induced “folding” of electrode-bound DNA probes. That is, we have developed a broad new class of biosensors that employ electrochemistry to monitor binding-induced changes in the rigidity of a redox-tagged probe DNA that has been site-specifically attached to an interrogating electrode. These folding-based sensors, which have been generalized to a wide range of specific protein, nucleic acid, and small-molecule targets, are rapid (responding in seconds to minutes), sensitive (detecting subpicomolar to micromolar concentrations), and reagentless. They are also greater than 99% reusable, are supported on micrometer-scale electrodes, and are readily fabricated into densely packed sensor arrays. Finally, and critically, their signaling is linked to a binding-specific change in the physics of the probe DNA—and not simply to adsorption of the target onto the sensor head. Accordingly, they are selective enough to be employed directly in blood, crude soil extracts, cell lysates, and other grossly contaminated clinical and environmental samples. Indeed, we have recently demonstrated the ability to quantitatively monitor a specific small molecule in real-time directly in microliters of flowing, unmodified blood serum.

Because of their sensitivity, substantial background suppression, and operational convenience, these folding-based biosensors appear potentially well suited for electronic, on-chip applications in pathogen detection, proteomics, metabolomics, and drug discovery.

Introduction

Biomolecular recognition is second to none when it comes to affinity, specificity and breadth. As a result, analytical approaches based on this phenomenon, including western blots, ELISAs and other immunochemical methods, dominate molecular pathology.1-3 These approaches, however, remain cumbersome, multi-step, laboratory-bound processes. Indeed, the only commercially viable biosensing device (as opposed to a process) on the market today is the glucose-oxidase-based blood sugar sensor, first described in the 1960s4,5 before coming into widespread use by diabetics across the globe.

A single, fundamental problem has largely thwarted the development of effective, reagentless biosensors: most biomolecules do not produce any readily measurable signal upon target binding. An antibody, for example, neither changes its shape or dynamics nor emits light or electrons upon binding its antigen. How, then, does one build a sensor based on biological recognition? A common approach in the field has, historically, been to tie the recognition biomolecule to a surface and then measure the change in refractive index (e.g., surface plasmon resonance6,7), mass (e.g., quartz crystal microbalanc8), steric bulk (e.g., static microcantilever,9,10 impedence spectroscopy11,12), or charge (e.g., field effect transistor-based sensors13,14) that occurs when the target –typically a bulky, charged macromolecule– is bound. Unfortunately, while several of these adsorption-based methods, such as the surface-plasmon resonance approach commercialized by Biacore,15-17 have proven of utility in academic laboratories, where high purity samples are the norm, they have also proven easily foiled by false positives in complex contaminant-ridden “real” samples. Studies of human blood serum, for example, have identified nearly 3,000 distinct proteins to date18 and it is estimated that the 60-80 mg total protein content of this material consists of up to 10,000 distinct components.19-21 Since these proteins also have mass, charge, etc., the non-specific adsorption of any of them is difficult or impossible to distinguish from the binding of the authentic target [e.g., 12].

Given that the field of marketable biosensors is so nascent, it is informative to explore the principles underlying the success of the single commercially viable, quantitative biosensor on the market to date: the home glucose meter. Key to its success is the fact that, unlike most biomolecules, this sensor's recognition element, glucose oxidase, produces a readily measurable response when it binds its target. Specifically, when it binds (and chemically transforms) its target, the enzyme produces hydrogen peroxide, which is then detected electrochemically. That is, nature has given us a gift with this protein: it has produced a mechanism that transduces target binding into a specific, readily detected output not easily spoofed by the non-specific adsorption of other materials to the sensor surface. This observation lies at the heart of the approach we have taken to the design of biosensors. Namely, the key development will be the identification of mechanisms linking biomolecular recognition with large-scale physical changes which, in turn, can be transduced into specific output signals.

Many biomolecules fold only upon binding their complementary target, thus linking recognition with an enormous change in conformation and dynamics [e.g., 22, 23]. For example, single-stranded DNA is unfolded (flexible, dynamic and fully solvated) in the absence of its “target” (its complementary strand), but “folds” into a rigid, well-structured double helix upon hybridization. More generally, it appears that most any single-domain protein or nucleic acid can be re-engineered such that it adopts its native conformations only upon recognizing its binding partner.24,25 That is, because biomolecular folding is generally cooperative it is easy to identify mutations that push the folding equilibrium heavily towards unfolding. Even largely unfolded mutants, however, still sample the native state, and, as only the native state binds the target, the presence of the target rapidly drives the equilibrium back to this state. That these equilibrium-unfolded biomolecules couple recognition with the least subtle of all possible conformational changes -folding itself- suggests that this effect can serve as a robust and general signal transduction mechanism.

From Signal Transduction to Biosensor: E-DNA

Signal transduction alone, however, does not make a biosensor: the binding event must also be transduced to an output signal that can be detected unambiguously against the background arising from any other molecules (interferants) likely in the sample. To this end, a number of optical reporters of binding-induced folding have been reported, [e.g., 24-33]. For example, Fred Kramer, a pioneer in this field, has developed fluorescent reporters that have been widely used to detect the binding (hybridization) induced “unfolding” of stem-loop DNA structures, commonly known as “molecular beacons”.31 Likewise, we and others have demonstrated optical reporters for the binding-induced folding of polypeptides, proteins and nucleic acid aptamers.25-27 From PNA-peptide chimera beacons to protein molecular switches to RNA aptamer beacons, these optical sensors detect targets ranging from antibodies to small molecules in the laboratory. Unfortunately, however, fluorescent and strongly absorbing interferants are common in clinical and environmental samples, an effect that, in practice, reduce the utility of such optical approaches in “real-world” settings [e.g., 28]. Electroactive interferants, in contrast, are relatively rare, suggesting that electrochemical approaches to monitoring binding-induced folding might be of broader utility. This idea, binding-induced biomolecular folding monitored electrochemically, has been the dominant focus of our research program.

The first electrochemical biosensor based on binding-induced folding was developed in 1993 by Chunhai Fan, then a postdoc in our group. As proof of principle, he immobilized one end of a stem-loop DNA onto a gold electrode via a terminal thiol modification (forming a self assembled monolayer) with the other end bearing a redox-reporting ferrocene34,35 to create an electrochemical DNA (E-DNA) sensor analogous to the optical stem-loop molecular beacons of Kramer.31 In the absence of target, the stem structure of the probe DNA holds the redox tag in proximity to the electrode, producing a large faradaic current. Hybridization to a complementary oligonucleotide removes the redox tag from the electrode, significantly decreasing this current and supporting the ready detection of specific DNA sequences (Fig. 1). Given the potential advantages of electrochemical detection (which we detail below), and the close analogy between E-DNA sensors and molecular beacons, it is perhaps not surprising that, within less than a year, several other groups reported them independently of our work,36,37 and in the years since numerous other authors have described their fabrication, characterization, optimization and applications.38

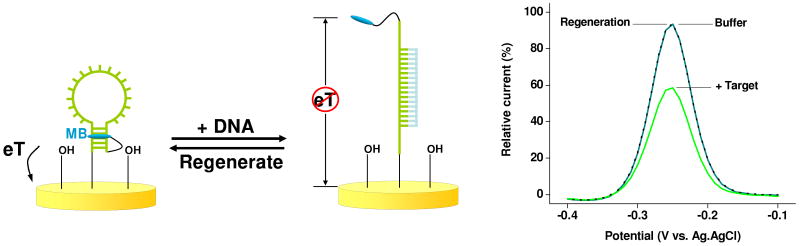

Figure 1.

The first E-DNA sensor comprised a redox-tagged stem-loop DNA attached to an interrogating electrode.34 In the absence of target, the redox tag is held in proximity to the electrode, ensuring efficient electron transfer (eT) and a large, readily detectable faradaic current. Upon hybridization with a target the redox tag is removed from the electrode, impeding the signaling current.

The E-DNA platform exhibits a number of potentially appealing attributes.39-42 First, it achieves sub-nanomolar detection limits, discriminates between at least modestly mismatched targets and responds rapidly (equilibration half-lives of between <1 and 30 minutes for targets of 17 to 100-bases).34,43-45 Second, because E-DNA signaling is associated with a ligand-induced change in the conformation and dynamics of the DNA probe and not simply absorption of the target to the sensor, the approach is quite impervious to complex “real” sample conditions and performs well even when challenged directly in multi-component, contaminant-ridden samples such as blood serum, saliva, urine, food-stuffs, and soil suspensions (Fig. 2).44-46 Third, because the E-DNA probe is strongly chemi-adsorbed onto its electrode, the approach is reagentless and readily reusable (we recover > 99% of our signal after a simple, aqueous wash44). Finally, because E-DNA is electrochemical, it is both scalable -we regularly employ micron-scale electrodes- and amenable to parallelization and device integration.47,48

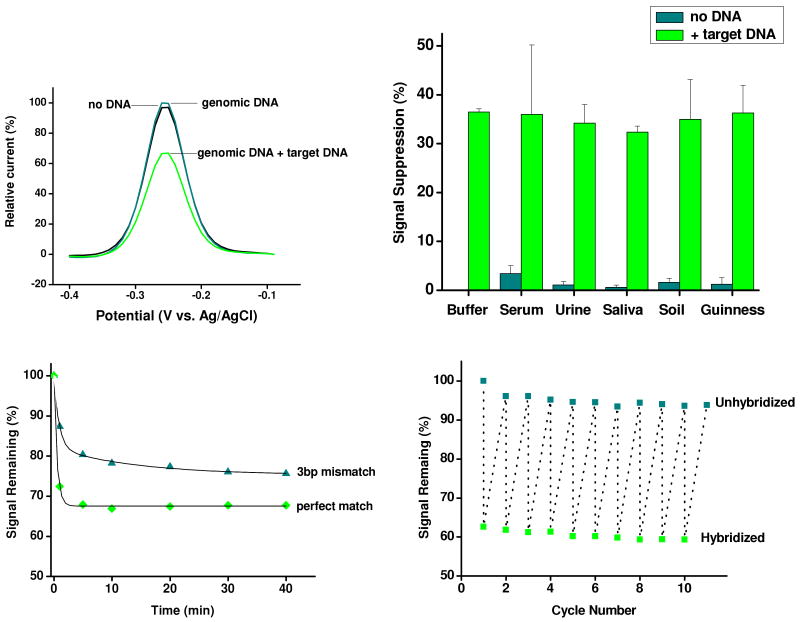

Figure 2.

E-DNA sensors are rapid, selective and readily reusable.45 (Top) For example, an E-DNA sensor specifically responds to target even in the presence of 50,000× excess genomic DNA and when deployed directly in complex “dirty” samples such as clinical materials, soil-suspensions and foodstuffs. (Bottom) E-DNA sensors equilibrate within minutes and are regenerated via a simple, 30 s wash with deionized water.

Sensor optimization and the mechanism of E-DNA sensing

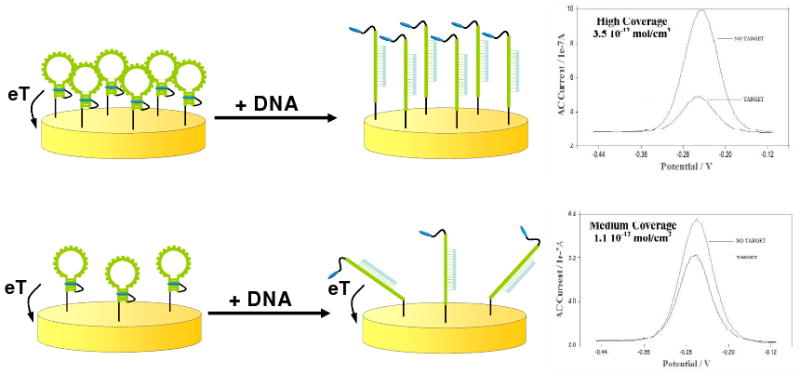

In the years since the inception of E-DNA, we have characterized a number of fabrication and operational parameters in an attempt to improve the signal gain, reproducibility and shelf life of the platform. Specifically, we have monitored the effects of varying probe length,49 the nature of the co-adsorbate forming the self-assembled monolayer,46,50-52 the density with which the probe DNAs are packed on the sensor and the electrochemical method employed53 on E-DNA performance and have achieved significant improvements in sensor gain and shelf life. These efforts have also shed light on the platform's signaling mechanism. Specifically, studies of the effects of probe packing density demonstrate that when the mean spacing between probes is less than their length (∼1012 probe molecules/cm2) the signal change upon hybridization improves with increasing probe density, presumably as crowding effects between the neighboring probe-target duplexes minimize electron transfer from the bound state and thus increase the observed signal change (Fig. 3). This suggests, in turn, that E-DNA signaling arises due to binding-linked changes in the efficiency with which the terminal redox tag strikes the electrode (i.e. with collision dynamics) and not to the binding-induced conformational change per se.53

Figure 3.

The signal gain of E-DNA sensors is a function of the density with which the probe DNAs are packed onto the electrode surface.53 Specifically, signaling improves with increasing probe density, presumably because crowding between neighboring probe-target duplexes minimizes electron transfer from the bound state, resulting in increased signal change upon hybridization.

Two additional lines of evidence support the “collision efficiency model” of E-DNA signaling. First, both our group and that of Inouye have observed that gain of E-DNA sensors can be tuned by varying the frequency at which the potential is modulated in alternating current or square wave voltammetry.53,54,55 Second, E-DNA sensors fabricated using single-stranded, linear probes also support efficient E-DNA signaling, presumably because the flexible, single-stranded state also supports efficient collisions.53,55 Indeed, because target binding no longer competes with the unfavorable energy of breaking the stem, the gain of linear probe sensors is improved relative to the equivalent stem-loop architecture.49

Increasing signal gain: from signal-off to signal-on architectures

A limitation of the first E-DNA architecture is that it is a “signal-off” sensor in which target recognition is signaled by the loss of an initially high current. A drawback is that this limits signal gain: one can never suppress more than 100% of the original current. Conversely, “signal-on” sensors, in theory, can approach enormous signal gain as the background observed in the absence of target is pushed towards zero. (By analogy fluorescence spectroscopy, a low-background “signal-on” technology, is much more sensitive than absorbance spectroscopy, which is “signal-off”). Thus motivated we, and others, have explored several signal-on E-DNA architectures.56-59

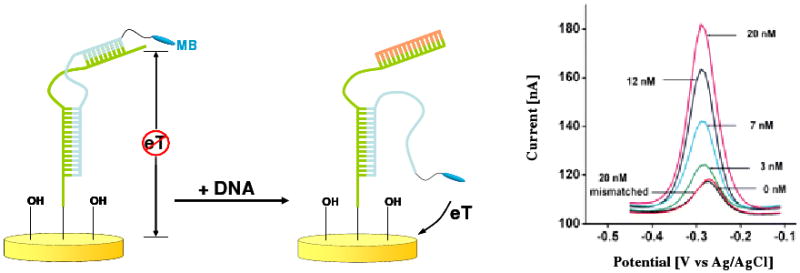

The first signal-on E-DNA sensor design, described by Immoos et al., consisted of a DNA-polyethylene glycol-DNA triblock probe immobilized onto an electrode and labeled at its distal terminus with a redox reporter.56 Hybridization with a target that is complementary to both of the flanking DNA elements brings the labeled end of the probe into proximity with the electrode, increasing electron transfer. This design results in 600% gain and a detection limit of ∼200 pM.56 In an effort to improve on this, we developed a second signal-on sensor via a strand displacement mechanism in which target binding displaces a flexible, single-stranded element modified with a redox-tag. Upon target binding the redox molecule at the terminus of the displaced strand generates up to a 700% increase in faradaic current, supporting detection down to sub-picomolar target concentrations57 (Fig. 4). A complication of the strand-displacement strategy, however, is that the labeled probe, which is the probe that is partially displaced upon target binding, is only held onto the sensor via hybridization with the surface attached strand and thus the stability and reusability of this sensor is poor. In response, we have more recently described a construct comprised of a single DNA chain that, in the absence of target, adopts a double-stem-loop pseudoknot structure that holds the redox tag away from the surface.58,59 Target binding disrupts the pseudoknot, liberating a flexible, single-stranded element that more readily collides with the electrode surface and produces a strong signal increase.

Figure 4.

This “signal-on” E-DNA architecture, based on a target-induced strand displacement mechanism, achieves sub-picomolar detection limits.57 In this mechanism sensor target binding displaces a flexible, single-stranded element modified with a redox-tag. This, in turn, strikes the electrode, generating a large increase in faradaic current.

The detection of non-nucleic acid targets

The above studies suggest that the only requisite for E-DNA signaling is that binding alters the flexibility of the signaling probe. This, in turn, suggests that the approach can be expanded to the detection of other targets provided they specifically bind to our probe and, in turn, alter its collision dynamics. To this end, Yi Xiao in our laboratory introduced aptamers, DNA or RNA sequences selected in vitro for specific and high affinity binding to a given target molecule,60-62 into the E-DNA platform.63 Critically, aptamers can be re-engineered such that they only fold upon target binding, thus coupling recognition with the type of large-scale change in flexibility required to generate an E-DNA-like signal [e.g., 64-67].

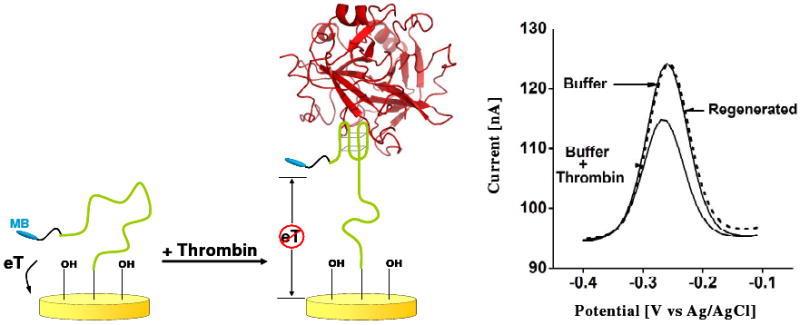

The first of these electrochemical, aptamer-based (E-AB) sensors utilized a 31-base probe that binds the enzyme thrombin.64,68-70 Following on the E-DNA platform, we labeled the 3′ terminus of this probe with a redox label and attached its 5′ terminus to a gold electrode (Fig. 5). This system produces a readily measurable decrease in faradaic current upon binding as little as 20 nM thrombin and is selective enough to deploy directly in blood serum.71 This first E-AB sensor, however, was signal-off and low gain. In an effort to convert it into a higher-gain, signal-on sensor Dr. Xiao later employed a strand-displacement mechanism analogous to the equivalent signal-on E-DNA sensor (Fig. 6). This new sensor yielded a ∼300% increase in signal at saturating target and a detection limit of just 3 nM.72

Figure 5.

The first electrochemical, aptamer-based (E-AB) sensor comprised a redox-tagged DNA aptamer directed against the blood-clotting enzyme thrombin.71 Thrombin biding reduces the current from the redox tag, readily signaling the presence of the target.

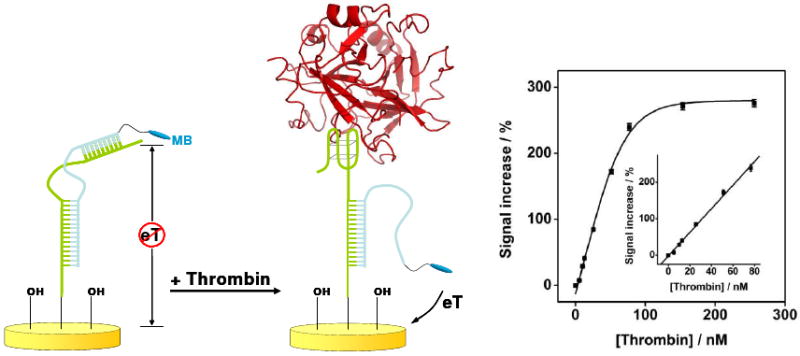

Figure 6.

A signal-on E-AB sensor based on the strand-displacement mechanism and directed against the protein thrombin achieves a 10-fold increase in signal gain over its signal-off counterpart (Fig. 5) and, in turn, a 7-fold increase in sensitivity.72

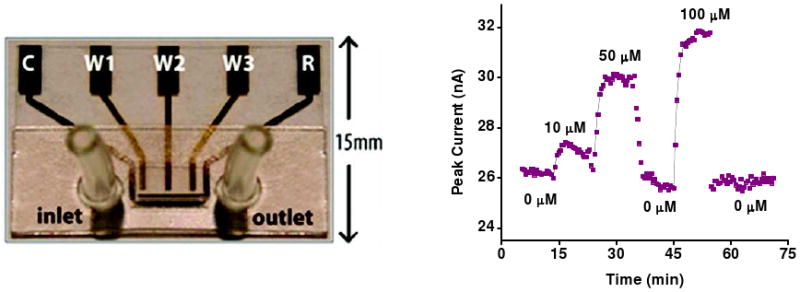

As was the case with our earlier E-DNA sensor, other reports quickly followed. For example, just a few months after our publication, O'Sullivan and co-workers described a sensor based on a similar aptamer sequence in which they observed an increase in faradaic current upon thrombin binding and a detection limit of 500 pM.73,74 Since then, other E-AB sensors have been reported against a wide range of targets [e.g., 75-84]. Employing a cocaine-binding aptamer, for example, we developed an E-AB sensor that can detect low micromolar concentrations of this target directly in blood serum and other complex sample matrices.75,76 Indeed, because the on- and off-rates for cocaine binding are rapid, this sensor supports real-time detection directly in flowing, undiluted blood serum (Fig. 7).77 O'Sullivan and co-workers then exploited the observation that the thrombin-binding aptamer also folds in the presence of potassium to detect this important ion,78 and we reported an E-AB sensor directed against the protein platelet-derived growth factor that achieves a 50 pM detection limit directly in blood serum.79 More recently still, Qu and co-workers have developed an E-AB sensor directed against carbon nanotubes80 and Kim and coworkers described a mercury sensor with a detection limit of 100 nM.81 Expanding the approach by employing RNA, rather than DNA, aptamers Gothelf and co-workers have developed a sensor for the asthma drug theophylline82 that achieves nanomolar detection limits in buffer82 and a somewhat lower sensitivity in diluted, RNAse-inhibited serum.83,84

Figure 7.

Small molecule E-AB sensors support real-time detection even in complex sample matrices, such as blood serum. The cocaine E-AB sensor, for example, supports real-time detection of cocaine directly in undiluted blood serum as it flows through a sub-microliter chamber.77 The letter designations on the external leads denote the “reference,” “counter,” and “working” electrodes to which they are attached.

All of the above sensors utilize probes that are contiguous strands attached to the interrogating electrode. However, in an approach similar to our strand-displacement E-AB sensor, several groups have used binding-induced folding to completely displace an aptamer from an electrode-bound complementary strand85 –or a complementary strand from an electrode-bound aptamer86– to generate a faradaic signal and detect ATP. Likewise we have utilized the strand cleaving ability of a lead-dependent DNAzyme to detect parts per billion lead directly in soil extracts.87

The Detection of DNA binding proteins

E-AB sensors expanded our approach to the detection of specific proteins and small molecules, but aptamers are not the only oligonucleotides that bind non-oligonucleotide targets. For example, while on sabbatical in our laboratory Francesco Ricci of the University of Rome, Tor Vergata employed double-stranded or single-stranded DNA probes to detect several, specific double- and single-stranded binding proteins at concentrations as low as 2 nM.88 Sensors employing single-stranded DNA probes, for example, supported the detection of endogenous single-strand binding activity in minutes, directly in crude cellular extracts.88

Non-nucleotide recognition elements

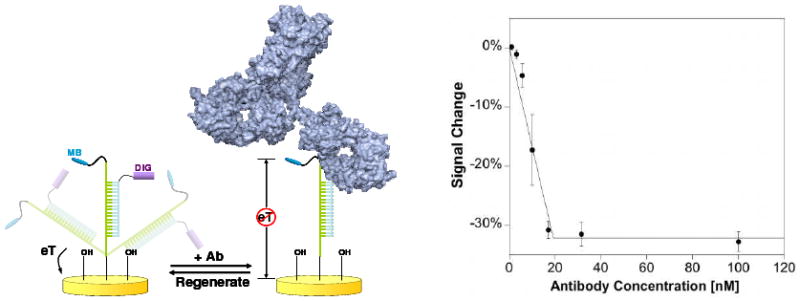

While the E-DNA/E-AB platform is versatile for several years it remained limited to analytes that bind nucleic acids. Recognizing this, Ricci and Kevin Cash in our group set out to expand the approach by appending small molecule recognition element onto a double-stranded DNA probe that acts as a physical scaffold (Fig. 8). 89 In the absence of target, a redox tag appended to this scaffold collides with the electrode, permitting electron transfer. The binding of a macromolecule to the receptor alters the efficiency of these collisions, leading to a change in faradaic current.89 First developed with the receptors biotin and digoxigenin, this technology readily detects sub-nanomolar to low nanomolar concentrations of antibodies and other small-molecule-binding proteins in complex, contaminant-ridden samples such as blood and blood serum. Recently for example, it has been employed to detect both anti-TNT antibodies and, via a competition assay, parts-per-trillion TNT in crude soil extracts.90 Moving forward we believe this “E-DNA scaffold” approach may prove a general method for the detection of macromolecules that bind to low molecular weight targets for application in, for example, drug screening.

Figure 8.

Utilizing double-stranded DNA as a support scaffold for a small molecule receptor, we have fabricated E-DNA-like sensors for the detection of protein-small molecule interactions.89 Shown, for example, is the detection of, low nanomolar concentrations of antibodies against the drug digoxigenin.

Conclusion and Outlook

The E-DNA platform is sensitive, convenient, specific and, importantly, selective enough to deploy directly in whole blood, cellular lysates, soil extracts and other realistically complex samples. Moreover, the approach requires only that target binding alter the efficiency with which the redox-tag on the probe biomolecule strikes the electrode, which can be induced by a switch between two discrete conformational states (as in the original stem-loop E-DNA sensor, or the various “strand-displacement” architectures we have described), by wholesale folding (as in E-AB sensors and linear-probe E-DNA sensors) or via a change in steric bulk, charge or hydrodynamic radius (for the detection of DNA-binding proteins and in the E-DNA scaffold approach). This, in turn, lends the approach great versatility and accounts for the wide range of targets for which such sensors have already been reported.

Given the potential promise of folding-based electrochemical biosensors, what does the future hold? Unfortunately the majority of the sensors described here are directed against analytes notable more for their convenience as test-bed targets than their value as clinically relevant diagnostics. This has largely precluded the rigorous side-by-side comparison of these approaches with current gold-standard clinical methods on authentic clinical samples. Thus, while the promise of this platform appears strong, it remains to be seen if it can deliver the clinically relevant specificity and sensitivity required to be of widespread use. Nevertheless, given the approach's many positive attributes, and given the growing number of research groups working on improving and expanding it, we are increasingly optimistic that platforms similar to those described in this account will offer viable solutions to a wide range of analytical problems.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge our colleagues and collaborators, with particular recognition going to Chunhai Fan and our long-standing collaborators Alan Heeger and Yi Xiao. We also thank Kevin Cash, Brian Baker, Rebecca Lai, Norbert Reich, Francesco Ricci, H. Tom Soh, James Sumner, James Swensen and Ryan White. This work was supported by the NIH (GM062958-01 and 2R01EB002046) and the Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies (DAAD19-03-D-0004 from the US Army Research Office).

Biographies

Arica Lubin received her B.S. in Biochemistry from UCSB in 2000. Continuing her education, she began her Ph.D. studies in Biochemistry under Plaxco in 2002 and finished her degree in 2009. Her work has focused on the development and characterization of electrochemical DNA sensors.

Kevin Plaxco completed his PhD studies performing molecular dynamics simulations under Goddard at Caltech. Following stints in experimental molecular biophysics with Dobson at Oxford and Baker at Washington he came to UCSB in 1998 and set up a group focused on protein folding. Realizing the potential engineering applications of folding he shifted gears once again in the mid-00s to focus on folding-based detection and responsive materials and devices.

References

- 1.Engvall E, Perlman P. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Quantitative assay of immunoglobulin G. Immunochemistry. 1971;8:871–874. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(71)90454-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Weemen BK, Schuurs AH. Immunoassay using antigen-enzyme conjugates. FEBS Letters. 1971;15:232–236. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(71)80319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renart J, Reiser J, Stark GR. Transfer of proteins from gels to diazobenzyloxymethyl-paper and detection with antisera: a method for studying antibody specificity and antigen structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:3116–3120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.7.3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark LC, Lyons C. Electrode Systems for Continuous Monitoring in Cardiovascular Surgery. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1962;102:29–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb13623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Updike SJ, Hicks GP. The enzyme electrode. Nature. 1967;214:986–988. doi: 10.1038/214986a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gouzy M, Keß M, Krämer PM. A SPR-based immunosensor for the detection of isoproturon. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;24:1563–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rich RL, et al. A global benchmark study using affinity-based biosensors. Anal Biochem. 2009;386:194–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frisk T, Sandstrom N, Eng L, van der Wijngaart W, Månsson P, Stemme G. An integrated QCM-based narcotics sensing microsystem. Lab On A Chip. 2008;8:1648–1657. doi: 10.1039/b800487k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shu W, Laurenson S, Knowles TPJ, Ferrigno PK, Seshia AA. Highly specific label-free protein detection from lysed cells using internally referenced microcantilever sensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;24:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen KM, Thundat T. Microcantilever biosensors. Methods. 2005;37:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du Y, Li B, Wei H, Wang Y, Wang E. Multifunctional label-free electrochemical biosensor based on an integrated aptamer. Anal Chem. 2008;80:5110–5117. doi: 10.1021/ac800303c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogomolova A, Komarova E, Reber K, Gerasimov T, Yavuz O, Bhatt S, Aldissi M. Challenges of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy in Protein Biosensing. Anal Chem. 2009;81:3944–3949. doi: 10.1021/ac9002358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakata T, Miyahara Y. Potentiometric detection of single nucleotide polymorphism by using a genetic field-effect transistor. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:703–710. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park HJ, Kim SK, Park K, Lyu HK, Lee CS, Chung SJ, Yun WS, Kim M, Chung BH. An ISFET biosensor for the monitoring of maltose-induced conformational changes in MBP. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fägerstam LG, Frostell Å, Karlsson R, Kullman M, Larsson A, Malmqvist M, Butt H. Detection of antigen-antibody interactions by surface plasmon resonance. Application to epitope mapping. J Mol Recognit. 1990;3:208–214. doi: 10.1002/jmr.300030507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fivash M, Towler EM, Fisher RJ. BIAcore for macromolecular interaction. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1998;9:97–101. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(98)80091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rich RL, Myszka DG. Survey of the year 2007 in commercial optical biosensor literature. J Mol Recognit. 2008;21:355–400. doi: 10.1002/jmr.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang H, Ali-Khan N, Echan LA, Levenkova N, Rux JJ, Speicher DW. A novel four-dimensional strategy combining protein and peptide separation methods enables detection of low-abundance proteins in human plasma and serum proteomes. Proteomics. 2005;5:339–3342. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wrotnowski C. The future of plasma proteins. Genet Eng News. 1998;18:14–X. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adkins JN, Varnum SM, Auberry KJ, Moore RJ, Angell NH, Smith RD, Springer DL, Pounds JG. Toward a human blood serum proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:947–955. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200066-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson NL, Anderson NG. The human plasma proteome: history, character, and diagnostic prospects. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:845–867. doi: 10.1074/mcp.r200007-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plaxco KW, Gross M. The importance of being unfolded. Nature. 1997;386:657–659. doi: 10.1038/386657a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fink AL. Natively unfolded proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohn JE, Plaxco KW. Engineering a signal transduction mechanism for protein-based biosensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10841–10845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503055102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh KJ, Cash KC, Plaxco KW. Beyond Molecular Beacons: Optical Sensors Based on the Binding-Induced Folding of Proteins and Polypeptides. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:2244–2251. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stratton MM, Mitrea DM, Loh SN. A Ca2+-Sensing Molecular Switch Based on Alternate Frame Protein Folding. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:723–732. doi: 10.1021/cb800177f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mok W, Li Y. Recent progress in nucleic acid aptamer-based biosensors and bioassays. Sensors. 2008;8:7050–7084. doi: 10.3390/s8117050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh KJ, Cash KJ, Plaxco KW. Excimer-based peptide beacons: A convenient experimental approach for monitoring polypeptide-protein and polypeptide-oligonucleotide interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14018–14019. doi: 10.1021/ja0651310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh KJ, Cash KJ, Hugenberg V, Plaxco KW. Peptide beacons: A new design for polypeptide-based optical biosensors. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:607–609. doi: 10.1021/bc060319u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh KJ, Cash KJ, Lubin AA, Plaxco KW. Chimeric peptide beacons: a direct polypeptide analog of DNA molecular beacons. Chem Commun. 2007:4869–4871. doi: 10.1039/b709776j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tyagi S, Kramer FR. Molecular beacons: Probes that fluoresce upon hybridization. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:303–308. doi: 10.1038/nbt0396-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thurley S, Roglin L, Seitz O. Hairpin peptide beacon: Dual-labeled PNA-peptide-hybrids for protein detection. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12693–12695. doi: 10.1021/ja075487r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan CH, Plaxco KW, Heeger AJ. Biosensors based on binding-modulated donor-acceptor distances. Trends Biotechnol. 2005;23:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan CH, Plaxco KW, Heeger AJ. Electrochemical interrogation of conformational changes as a reagentless method for the sequence-specific detection of DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9134–9137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633515100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao Y, Lai RY, Plaxco KW. Preparation of electrode-immobilized, redox modified oligonucleotides for electrochemical DNA and aptamer-based sensing. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2875–2880. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Immoos CE, Lee SJ, Grinstaff MW. Conformationally gated electrochemical gene detection. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:1100–1103. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mao Y, Luo C, Ouyang Q. Studies of temperature-dependent electronic transduction on DNA hairpin loop sensor. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31:e108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ricci F, Plaxco KW. E-DNA sensors for convenient, label-free electrochemical detection of hybridization. Microchim Acta. 2008;163:149–155. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee TM. Over-the-counter biosensors: past, present, and future. Sensors. 2008;8:5535–5559. doi: 10.3390/s8095535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odenthal KJ, Gooding JJ. An introduction to electrochemical DNA biosensors. Analyst. 2007;132:603–610. doi: 10.1039/b701816a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendes PM. Stimuli-responsive surfaces for bio-applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:2512–2529. doi: 10.1039/b714635n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Privett BJ, Shin JH, Schoenfisch MH. Electrochemical sensors. Anal Chem. 2008;80:4499–4517. doi: 10.1021/ac8007219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lai RY, Lagally ET, Lee SH, Soh HT, Plaxco KW, Heeger AJ. Rapid, sequence-specific detection of unpurified PCR amplicons via a reusable, electrochemical sensor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4017–4021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511325103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lubin AA, Lai RY, Baker BR, Heeger AJ, Plaxco KW. Sequence-specific, electronic detection of oligonucleotides in blood, soil, and foodstuffs with the reagentless, reusable E-DNA sensor. Anal Chem. 2006;78:5671–5677. doi: 10.1021/ac0601819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lubin AA, Fan C, Schafer M, Clelland CT, Bancroft C, Heeger AJ, Plaxco KW. Rapid Electronic Detection of DNA and Nonnatural DNA Analogs for Molecular Marking Applications. For Sci Commun. 2008;10(1) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lai RY, Seferos DS, Heeger AJ, Bazan GC, Plaxco KW. Comparison of the signaling and stability of electrochemical DNA sensors fabricated from 6- or 11-carbon self-assembled monolayers. Langmuir. 2006;22:10796–10800. doi: 10.1021/la0611817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lai RY, Lee SH, Soh HT, Plaxco KW, Heeger AJ. Differential labeling of closely spaced biosensor electrodes via electrochemical lithography. Langmuir. 2006;22:1932–1936. doi: 10.1021/la052132h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pavlovic E, Lai RY, Wu TT, Ferguson BS, Sun R, Plaxco KW, Soh HT. Microfluidic device architecture for electrochemical patterning and detection of multiple DNA sequences. Langmuir. 2008;24:1102–1107. doi: 10.1021/la702681c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lubin AA, Vander Stoep Hunt B, White RJ, Plaxco KW. Effects of Probe Length, Probe Geometry, and Redox-Tag Placement on the Performance of the Electrochemical E-DNA Sensor. Anal Chem. 2009;81:2150–2158. doi: 10.1021/ac802317k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ricci R, Zari N, Caprio F, Recine S, Amine A, Moscone D, Palleschi G, Plaxco KW. Surface chemistry effects on the performance of an electrochemical DNA sensor. Bioelectrochem. 2009;76:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phares N, White RJ, Plaxco KW. Improving the stability and sensing of electrochemical biosensors by employing trithiol-anchoring groups in a six-carbon self-assembled monolayer. Anal Chem. 2009;81:1095–1100. doi: 10.1021/ac8021983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seferos DS, Lai RY, Plaxco KW, Bazan GC. alpha,omega-dithiol oligo(phenylene vinylene)s for the preparation of high-quality pi-conjugated self-assembled monolayers and nanoparticle-functionalized electrodes. Adv Funct Mater. 2006;16:2387–2392. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ricci F, Lai RY, Heeger AJ, Plaxco KW, Sumner JJ. Effect of molecular crowding on the response of an electrochemical DNA sensor. Langmuir. 2007;23:6827–6834. doi: 10.1021/la700328r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ricci F, Lai RY, Plaxco KW. Linear, redox modified DNA probes as electrochemical DNA sensors. Chem Commun. 2007:3768–3770. doi: 10.1039/b708882e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ikeda R, Kobayashi S, Chiba J, Inouye M. Detection of mismatched duplexes by synchronizing the pulse potential frequency with the dynamics of ferrocene/isoquinoline conjugate-connected DNA probes immobilized onto electrodes. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:4822–4828. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Immoos CE, Lee SJ, Grinstaff MW. DNA-PEG-DNA triblock macromolecules for reagentless DNA detection. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10814–10815. doi: 10.1021/ja046634d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xiao Y, Lubin AA, Baker BR, Plaxco KW, Heeger AJ. Single-step electronic detection of femtomolar DNA by target-induced strand displacement in an electrode-bound duplex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16677–16680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607693103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiao Y, Qu XG, Plaxco KW, Heeger AJ. Label-free electrochemical detection of DNA in blood serum via target-induced resolution of an electrode-bound DNA pseudoknot. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11896–11897. doi: 10.1021/ja074218y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cash KJ, Heeger AJ, Plaxco KW, Xiao Y. Optimization of a Reusable, DNA Pseudoknot-Based Electrochemical Sensor for Sequence-Specific DNA Detection in Blood Serum. Anal Chem. 2009;81:656–661. doi: 10.1021/ac802011d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ellington AD, Szostak JW. Invitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature. 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tuerk C, Gold L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment – RNA ligands to baceriophage-T4 DNA-polymerase. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robertson MP, Joyce GF. Selection invitro of an RNA enzyme that specifically claves single-stranded-DNA. Nature. 1990;344:467–470. doi: 10.1038/344467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiao Y, Plaxco KW. Electrochemical Approaches to Aptamer-Based Sensing. In: Lu Y, Li Y, editors. Functional Nucleic Acids for Analytical Applications. Chapter 7 Springer Science + Business Media; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hamaguchi N, Ellington A, Stanton M. Aptamer beacons for the direct detection of proteins. Anal Biochem. 2001;294:126–131. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li JWJ, Fang XH, Tan WH. Molecular aptamer beacons for real-time protein recognition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;292:31–40. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Potyrailo RA, Conrad RC, Ellington AD, Hieftje GM. Adapting selected nucleic acid ligands (aptamers) to biosensors. Anal Chem. 1998;70:3419–3425. doi: 10.1021/ac9802325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baldrich E, Restrepo A, O'Sullivan CK. Aptasensor development: elucidation of critical parameters for optimal aptamer performance. Anal Chem. 2004;76:7053–7063. doi: 10.1021/ac049258o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bock LC, Griffin LC, Latham JA, Vermaas EH, Toole JJ. Selection of single-stranded DNA molecules that bind and inhibit human thrombin. Nature. 1992;355:564–566. doi: 10.1038/355564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dittmer WU, Reuter A, Simmel FC. A DNA-based machine that can cyclically bind and release thrombin. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:3550–3553. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Macaya RF, Schultze P, Smith FW, Roe JA, Feigon J. Thrombin-binding DNA aptamer forms a unimolecular quadruplex structure in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3745–3749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xiao Y, Lubin AA, Heeger AJ, Plaxco KW. Label-free electronic detection of thrombin in blood serum by using an aptamer-based sensor. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:5456–5459. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xiao Y, Piorek BD, Plaxco KW, Heeger AJ. A reagentless signal-on architecture for electronic, aptamer-based sensors via target-induced strand displacement. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17990–17991. doi: 10.1021/ja056555h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Radi A, Sanchez JLA, Baldrich E, O'Sullivan CK. Reagentless, reusable, ultrasensitive electrochemical molecular beacon aptasensor. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:117–124. doi: 10.1021/ja053121d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sanchez JLA, Balrich E, Radi AE, Dondapati S, Sanchez PL, Katakis I, O'Sullivan CK. Electronic ‘Off-On’ molecular switch for rapid detection of thrombin. Electroanalysis. 2006;18:1957–1962. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baker BR, Lai RY, Wood MS, Doctor EH, Heeger AJ, Plaxco KW. An electronic, aptamer-based small-molecule sensor for the rapid, label-free detection of cocaine in adulterated samples and biological fluids. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3138–3139. doi: 10.1021/ja056957p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.White RJ, Phares N, Lubin AA, Xiao Y, Plaxco KW. Optimization of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors via optimization of probe packing density and surface chemistry. Langmuir. 2008;24:10513–10518. doi: 10.1021/la800801v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Swensen JS, Xiao Y, Ferguson BS, Lubin AA, Lai RY, Heeger AJ, Plaxco KW, Soh HT. Continuous, real-time monitoring of cocaine in undiluted blood serum via a microfluidic, electrochemical aptamer-based sensor. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4262–4266. doi: 10.1021/ja806531z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Radi AE, O'Sullivan CK. Aptamer conformational switch as sensitive electrochemical biosensor for potassium ion recognition. Chem Commun. 2006:3432–3434. doi: 10.1039/b606804a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lai RY, Plaxco KW, Heeger AJ. Aptamer-based electrochemical detection of picomolar platelet-derived growth factor directly in blood serum. Anal Chem. 2007;79:229–233. doi: 10.1021/ac061592s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peng Y, Wang X, Xiao Y, Feng L, Zhao C, Ren J, Qu X. i-Motif quadruplex DNA-based biosensor for distinguishing single- and multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13813–13818. doi: 10.1021/ja9051763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Han D, Kim Y, Oh J, Kim TH, Mahajan RK, Kim JS, Kim H. A regenerative electrochemical sensor based on oligonucleotide for the selective determination of mercury (II) Analyst. 2009;134:1857–1862. doi: 10.1039/b908457f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ferapontova EE, Olsen EM, Gothelf KV. An RNA aptamer-based electrochemical biosensor for detection of Theophylline in Serum. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4256–4258. doi: 10.1021/ja711326b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ferapontova EE, Gothelf KV. Effect of serum on an RNA aptamer-based electrochemical sensor or theophylline. Langmuir. 2009;25:4279–4283. doi: 10.1021/la804309j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ferapontova EE, Gothelf KV. Optimization of the electrochemical RNA-aptamer based biosensor for theophylline by using a methylene blue redox label. Electroanalysis. 2009;21:1261–1266. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lu Y, Li X, Zhang L, Yu P, Su L, Mao L. Aptamer-based electrochemical sensors with aptamer-complementary DNA oligonucleotides as probe. Anal Chem. 2008;80:1883–1890. doi: 10.1021/ac7018014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zuo X, Song S, Zhang J, Pan D, Wang L, Fan C. A target-responsive electrochemical aptamer switch (TREAS) for reagentless detection of nanomolar ATP. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1042–1043. doi: 10.1021/ja067024b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xiao Y, Rowe AA, Plaxco KW. Electrochemical detection of parts-per-billion lead via an electrode-bound DNAzyme assembly. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:262–263. doi: 10.1021/ja067278x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ricci F, Bonham AJ, Mason AC, Reich NO, Plaxco KW. Reagentless, electrochemical approach for the specific detection of double- and single-Stranded DNA binding proteins. Anal Chem. 2009;81:1608–1614. doi: 10.1021/ac802365x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cash KJ, Ricci F, Plaxco KW. An electrochemical sensor for the detection of protein-small molecule interactions directly in serum and other complex matrices. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6955–6957. doi: 10.1021/ja9011595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cash K, Ricci F, Plaxco K. A general electrochemical method for label-free screening of protein-small molecule interactions. Chem Commun. 2009 doi: 10.1039/b911558g. on web Aug 28, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]