Abstract

Sepsis is a major cause of mortality worldwide. Acute or chonic ethanol exposure typically suppresses innate immunity and inflammation and increases the risk of mortality in patients with sepsis. The study described here was designed to address the mechanism(s) by which acute ethanol exposure alters the course of sepsis. Ethanol administered to mice shortly before Escherichia coli (injected ip to produce sepsis) decreased production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines for several hours. Bacteria in the peritoneal cavity decreased over time in control mice and were mostly cleared by 21 h, but in ethanol-treated mice, bacteria increased over time to more than 2 × 108 at 21 h. Killing of bacteria in macrophages and neutrophils was apparently compromised by ethanol, as the percentage of these cells that had cleared phagocytosed bacteria increased over time in control mice but not in ethanol-treated mice. The roles of TLR4, MyD88, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) were evaluated using mutant or knockout mice, and these experiments indicated that mice with hyporesponsive TLR4 survived better than those with normal TLR4. Lack of MyD88 or MPO did not significantly alter survival in the presence or absence of ethanol. Ethanol decreased survival in all groups. This indicates that the antimicrobial activities induced though TLR4 are dispensable for survival but contribute to lethality late in the course of sepsis. Thus, the effects of ethanol responsible for lethal outcome in sepsis are not dependent on inhibition of TLR4 signaling, as we and others had previously suspected.

Keywords: macrophages, neutrophils, bacterial infection, cytokines, lipopolysaccharide, inflammation

Sepsis is a complex process involving interactions between the host and the causative microbe. The mortality rate for sepsis ranges from about 12% (Lin et al., 2009) to more than 60%, depending on a variety of factors. In spite of antibiotic and supportive therapy, sepsis is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States (Anonymous, 2007). Acute ethanol consumption is a significant risk factor for mortality in patients with sepsis (Huttunen et al., 2007; McGill et al., 1995), and our mouse model produces similar results (Pruett et al., 2004c). Animal models have also revealed that proinflammatory mediators are important contributors to lethality in sepsis (Lally et al., 2000). However, inhibition of these mediators in clinical trials has typically not improved the outcome significantly for sepsis patients (Marshall, 2008). Characterizing the increase of lethality in sepsis caused by ethanol in a mouse model is a unique approach to identify mechanisms of lethality in sepsis that may be, at least in part, functionally redundant, thereby explaining the ineffectiveness of inhibition of any single inflammatory mediator. The study described here was designed to characterize some of the inflammatory mechanisms associated with lethality in sepsis as an initial step in identifying such mechanisms, which would be potential targets for combination therapies to neutralize more than one inflammatory mediator. Lethality was increased by treating mice with ethanol in a binge-drinking model.

Chonic and acute ethanol exposure inhibits a variety of immunological parameters and decrease resistance to infection (Bagby et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2006). Suppression of inflammatory responses by acute exposure to ethanol is particularly striking in both humans (Gluckman and MacGregor, 1978; Szabo et al., 1999) and animal models (Fitzgerald et al., 2007; Pruett et al., 2004b). The model used in the present study is intended to represent sepsis caused by microbial contamination of the peritoneal cavity (e.g., following penetrating abdominal trauma, ruptured appendix, cirrhosis of the liver, or other conditions that interfere with the normal barrier function of the mucosa). Increased rates of infection have been reported in patients with penetrating abdominal trauma following acute ethanol exposure (Gentilello et al., 1993). Similar results have been reported in burn patients (Germann et al., 1997). Sepsis caused by indigenous bacteria may begin as a polymicrobial infection, but in most cases. only one bacterium is isolated, and Escherichia coli is one of the most frequent (Huttunen et al., 2007). Decreased resistance to infection has also been reported in animal models (D'Souza et al., 1995; Pruett et al., 2004b), but this has not been investigated in as much detail as inhibition of production of particular inflammatory mediators. Studies in which inhibition of inflammatory responses has been implicated as a cause of decreased resistance to microbes have been relatively rare. However, such studies can potentially reveal much about the normal mechanisms by which inflammation promotes bacterial clearance and host survival because the effects of inhibiting a number of those mechanisms simultaneously are revealed by ethanol. In this instance, inhibiting production of several mediators at the same time is beneficial because it will provide an indication of a set of mediators that contribute to lethality. In the present study, evidence is presented indicating that mice treated with ethanol exhibit suppression of several mediators and processes of inflammation early, which is followed by an overgrowth of bacteria and possibly a lethal systemic inflammatory response.

Responses triggered though TLR4 and other Toll-like receptors are inhibited by acute ethanol exposure (Goral and Kovacs, 2005; Pruett et al., 2004b), and many investigators (including the present authors) have suggested that this contributes to decreased resistance to infection. To test this assumption, effects of ethanol in wild-type mice were compared with its effects in mice lacking MyD88, myeloperoxidase (MPO), or with a mutant hyporesponsive TLR4. The results unexpectedly demonstrated that inhibition of TLR4 signaling by ethanol is probably not a major cause of decreased resistance to sepsis in the experimental system used here.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, treatments, and procedures.

For most experiments, female C57Bl/6 × C3H F1 mice were used. Female mice were used because males fight when group housed and this causes stress, which can affect the results, and single housing can also cause stress. These mice were obtained though the National Cancer Institute's Animal Program. They were allowed to recover from shipping stress for at least 2 weeks before beginning experiments, and they were 12–16 weeks old when used. In some experiments, C3H/Hej mice were used because they have a mutant TLR4 gene, which yields a protein that is almost nonresponsive to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS; the major naturally occurring ligand for TLR4). These mice and a strain matched as closely as possible at every locus other than TLR4, C3H/HeOuJ, were obtained from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME). These mice were female and were used at 12–16 weeks of age after at least 2 weeks of recovery from shipping stress. Transgenic MyD88-knockout mice on a C57Bl/6 background were kindly provided by Dr Shizuo Akira (Hyogo College of Medicine, Hyogo, Japan) treated as the other strains and used at the same age range. An equal number of C57Bl/6 wild-type mice were purchased from Jackson Labs as controls. MPO-deficient mice (obtained from Jackson Labs) also had a C57Bl/6 background, and C57Bl/6 controls were used. Because of decreased resistance to some microbes, food, water, and bedding were autoclaved before use for both the knockout and wild-type C57Bl/6 mice. Mice were housed in filter top shoebox cages with five mice per cage in a temperature (70–78°F) and humidity (40–60%)-controlled environment. The laboratory animal facility and animal research program at Mississippi State University are accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Mice were housed and used in accord with the National Institutes of Health and Mississippi State University regulations. Sentinel mice housed in the same room as the mice used in this study were negative for all common pathogens of mice during the period of this study.

Mice in various groups were treated as follows: ethanol was administered by gavage at 4 or 6 g/kg using a 32% (vol/vol) solution in tissue culture grade water or water alone as a control; viable E. coli, log phase, grown in Luria Bertani broth, were administered ip. Both dosages of ethanol yield blood ethanol levels that occur in humans (Urso et al., 1981), and this mouse model for binge drinking developed in this laboratory has been thoroughly characterized (Carson and Pruett, 1996) and used by a number of other investigators (Park et al., 2005). The dosage of E. coli was 1.5 × 108 per mouse, which was similar to dosages used by other investigators (Roger et al., 2009).

Mice were observed at least every 6 h after challenge, and mice that were moribund and those with a body temperature less than 27°C were euthanized and counted as dead at each time point indicated. Body temperature was measured by en electronic thermometer with a mice rectal probe (Physitemp, Clifton, NJ). Mice were restrained manually, the probe was lubricated using sterile glycerol and inserted for 5 s (or until the temperature reading stabilized), and results were recorded. In this model of sepsis (as in some cases of sepsis in humans), profound hypothermia is observed. However, in mice that will ultimately survive, hypothermia is less severe (Wei and Pruett, unpublished observations). It should be noted that severe illness typically proceeded to death very quickly, such that most deaths occurred between the 6-h observation points, and only a few cases of moribund mice or mice with very low body temperatures were removed from the study.

Experiments were designed with a group size of 5 for all experiments except survival studies, for which the group size was 10. In survival studies, mice were observed for 72 h (in previous studies, no deaths were observed after 72 h). Mice were treated by gavage with vehicle (water) or ethanol, and 30 min later, they were challenged ip with E. coli (1.5 × 108 per mouse). In most experiments, one group of mice, referred to as naive, remained untreated and was not challenged with E. coli. This group served to confirm that the anticipated inflammatory changes were induced by E. coli. Different groups of mice were anesthetized by inhalation of halothane at various times from 1 to 21 h after E. coli challenge and were bled (from the retro-orbital plexus), and peritoneal lavage was performed. Samples of this fluid were used to quantify bacteria by making serial dilutions in LB agar (held at 45°C to prevent solidification, plating, and performing plate counts). Samples were also used for cytospin preparations followed by Wright-Giemsa staining and differential cell counts at 600× magnification with an oil immersion lens. Cells with three or more bacteria associated were referred to as cells with E. coli, and cells with less than three bacteria were referred to as cells without E. coli. This was designed to account for the possibility that some of the bacteria that appeared to be intracellular might actually be on the cell surface. The number of nucleated cells was determined using a sample of peritoneal lavage fluid with cells suspended. Manual lysing reagent was added to lyse the cytoplasmic membrane, leaving nuclei only to be counted. Counts were determined using a Coulter Z1 particle counter (Hialeah, FL).

Bacteria.

The E. coli strain used in this study was isolated from the colon of one of the mice in our specific pathogen-free colony. It was characterized by the College of Veterinary Medicine Clinical Microbiology Lab as nonpathogenic E. coli. As expected for nonpathogenic bacteria, mice can clear a large number without mortality. However, 1.5 × 108 per mouse routinely yields 10–20% mortality, indicating that this is a sufficient dosage to identify decreased resistance to sepsis, which would cause higher mortality. Bacteria for each experiment were prepared starting with a frozen vial, which was one of a set frozen at the same time from the same culture. Bacteria were in log growth phase (as indicated by optical density [OD] at 650 nm), and dosages were estimated using OD measurements and a standard growth curve. This number was verified by serial dilutions and plate counts, and values were always within 10% of the nominal count. This model is expected to be representative of sepsis in humans that begins with loss of gastrointestinal barrier function (caused, e.g., by trauma, appendicitis, diminished liver function, or other conditions). In human peritonitis, a single species of bacteria often predominates, and in approximately half of cases, E. coli is the species isolated in blood cultures (De Waele et al., 2008). Thus, administration of a single strain of indigenous E. coli in our model allows more controlled conditions than cecal ligation and puncture but yields peritonitis and sepsis similar to that observed in humans.

Cytokine and chemokine assays.

Concentrations of cytokines and chemokines in serum were quantified using multiplexed bead array kits (with standards for each cytokine or chemokine) from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) with a BioPlex analyzer (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis.

The log-rank test, as implemented by Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software, LaJolla, CA), was used to compare survival data. The same software was used to perform one-way ANOVA, and the means of all groups were compared using the Newman-Keuls post hoc test. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

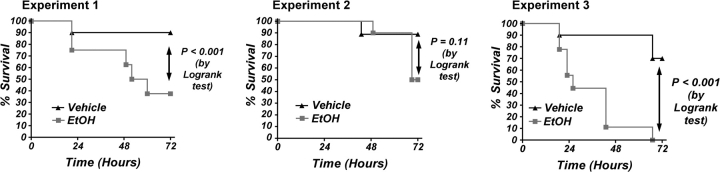

Acute administration of ethanol increased mortality in a mouse model for peritonitis/sepsis. This was a consistent finding, but the exact percentages of survival in control and ethanol-treated animals varied to some degree, as typical for infectious disease models. The results shown in Figure 1 indicate survival results using 10 mice per group that were gavaged with vehicle or ethanol then challenged with E. coli. In each experiment, ethanol significantly decreased survival at 72 h following challenge with the same dosage of nonpathogenic E. coli. The mortality at 72 h in this model ranged from 10 to 30% in control animals in three independent experiments with B6C3F1 mice and from 50 to 100% in ethanol-treated mice (6 g/kg 30 min before bacterial challenge).

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of survival after challenge of mice with viable Escherichia coli in vivo. Challenge with E. coli at 1.5 × 108 caused at least 10% mortality in control groups and 50% or more in ethanol-treated groups in the three independent experiments shown here. The difference between the survival curve for control and ethanol-treated mice was significant by the log-rank test (p < 0.05) for the three sets of results shown here.

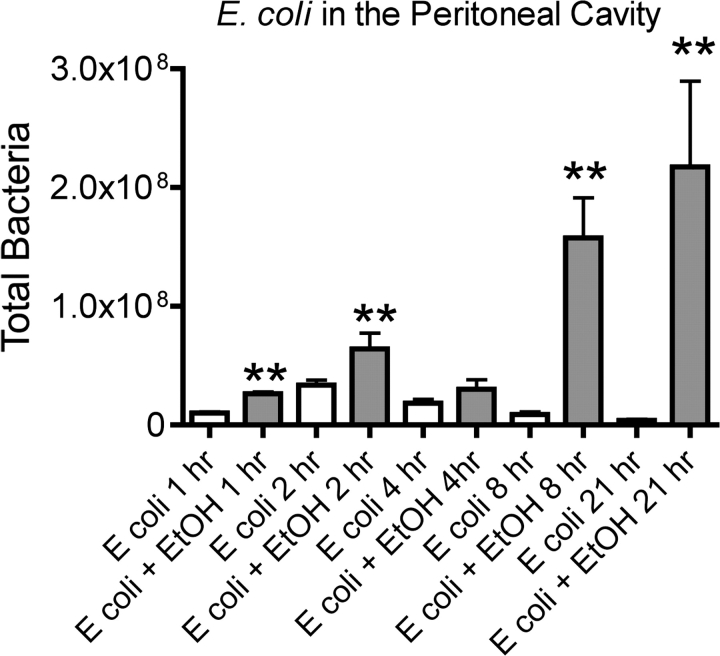

Results shown in Figure 2 indicate the number of viable E. coli isolated at various times after challenge from the peritoneal cavity of control and ethanol-treated mice. The results demonstrate that after a brief increase in number, bacteria are progressively cleared over time in control mice. In contrast, the bacteria continue to grow though 21 h in ethanol-treated mice. The SEM increases at the later time points in ethanol-treated mice. This very likely reflects the fact that some of the mice in the ethanol-treated group will survive (as in Fig. 1). Survivors may have begun clearing bacteria by 21 h, whereas nonsurvivors would not be expected to do this.

FIG. 2.

Viable Escherichia coli counts in peritoneal lavage fluid from control and ethanol-treated mice challenged with E. coli. Samples were taken at the indicated times after E. coli challenge. Results shown for 2 and 4 h were obtained from two independent experiments (n = 5 mice per group in each). Results at other times were obtained in separate experiments in which n = 5 mice per group. Values shown are means ± SEM, and significant differences between the control and ethanol-treated group at each time point (as determined by Student's t test) are indicated by **p < 0.01.

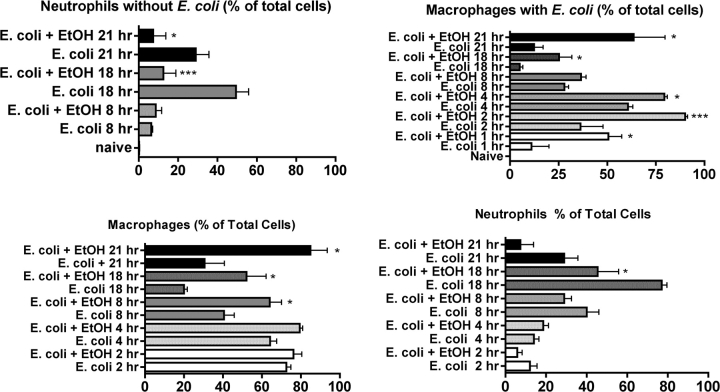

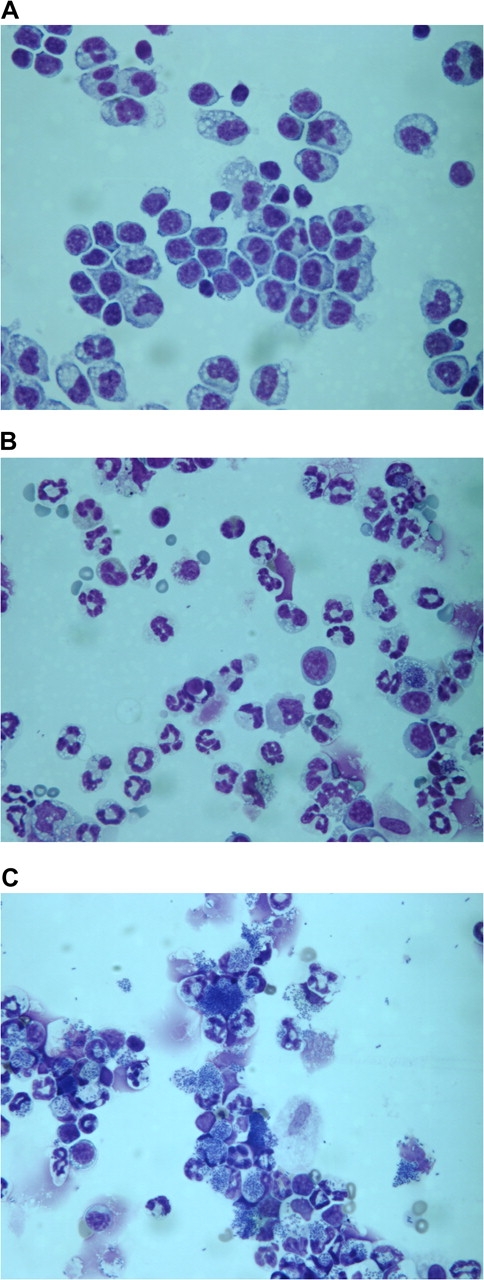

As we reported previously, most of the cells in the peritoneal cavity of normal B6C3F1 female mice are macrophages (Fig. 3A). In contrast, 18 h after challenge with E. coli, the predominant cell type was the neutrophil in control mice and very few bacteria remained (Fig. 3B). In contrast, bacteria were remarkably abundant in mice treated with ethanol before E. coli challenge (Fig. 3C) due to either increased phagocytosis or decreased clearance of the bacteria. There was also a lower percentage of neutrophils than in the control group (shown in detail in Fig. 4), indicating impaired chemotaxis or migration of neutrophils to the initial site of infection or increased death of neutrophils.

FIG. 3.

Phagocytosis and clearance of bacteria by peritoneal phagocytes in control and ethanol-treated mice. Cytospin preparations were stained with Wright-Giemsa stain and observed microscopically at 600× with an oil immersion lens. In (A), cells isolated by peritoneal lavage from naive (untreated mice) are shown. As we have reported previously, macrophages and monocytes comprised at least 85% of total cells. No bacteria were visible. In (B), cells were isolated from control mice 18 h after challenge with Escherichia coli. The percentage of neutrophils had increased substantially, and very few bacteria were evident (small dark rods within or near cells). In (C), cells were isolated from ethanol-treated mice 18 h after E. coli challenge. The samples shown here are representative of five mice per group, for which quantitative results are shown in Figure 4.

FIG. 4.

Changes in the percentage of different cell types with or without associated Escherichia coli in control and ethanol-treated mice during the course of peritonitis. Control and ethanol-treated mice at each time were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc, and significant differences are indicated by *p < 0.05 or ***p < 0.001. Cells were observed microscopically (using preparations such as those shown in Fig. 3), and those with three or more bacteria closely associated were referred to as cells with E. coli, and those with less than three bacteria in close association were referred to as cells without E. coli.

Although the numbers of bacteria phagocytosed by each macrophage or neutrophil could not be determined precisely by the type of microscopic analysis done here, quantifying the overall process of phagocytosis and clearance was accomplished by discriminating between neutrophils/macrophages with associated bacteria and the ones without bacteria. Because it was possible that some of the bacteria observed were associated with phagocytes on the cell surface and not phagocytosed, a criterion of three bacteria per cell was used to classify a cell as positive for bacteria. Cells with less than three associated bacteria were classified as negative. This is not intended as precise quantitation of phagocytosis but was done just to give a general impression of how the phagocytosis of bacteria by macrophages/neutrophils after E. coli challenge is affected by ethanol. Results of such an analysis are shown in Figure 4. The percentage of macrophages with bacteria increased from 1 to 4 h in control mice, probably reflecting continued phagocytosis. After 4 h, the percentage of macrophages with bacteria decreased in control mice as bacteria were killed and digested by the phagocytic cells. Ethanol increased the percentage of macrophages with bacteria throughout the time course. At the early time points (1–4 h), this could be due to increased phagocytosis or decreased clearance because the number of cells with bacteria depends on the rate of phagocytosis and the rate of clearance. However, at later times, it seems unlikely that enhanced phagocytosis could explain the increased number of bacteria because bacteria had mostly been phagocytosed by then in the ethanol-only group. Thus, it seems more likely that the increased number of cells with bacteria (which corresponds with the increased bacterial number overall shown in Fig. 2) is due to macrophage and/or neutrophil dysfunction leading to inefficient bacterial killing. In control mice, the percentage of neutrophils in the peritoneal cavity increases over time, but this increase was inhibited by ethanol, which is consistent with inhibition of some of the chemokines that attract neutrophils (see next paragraph).

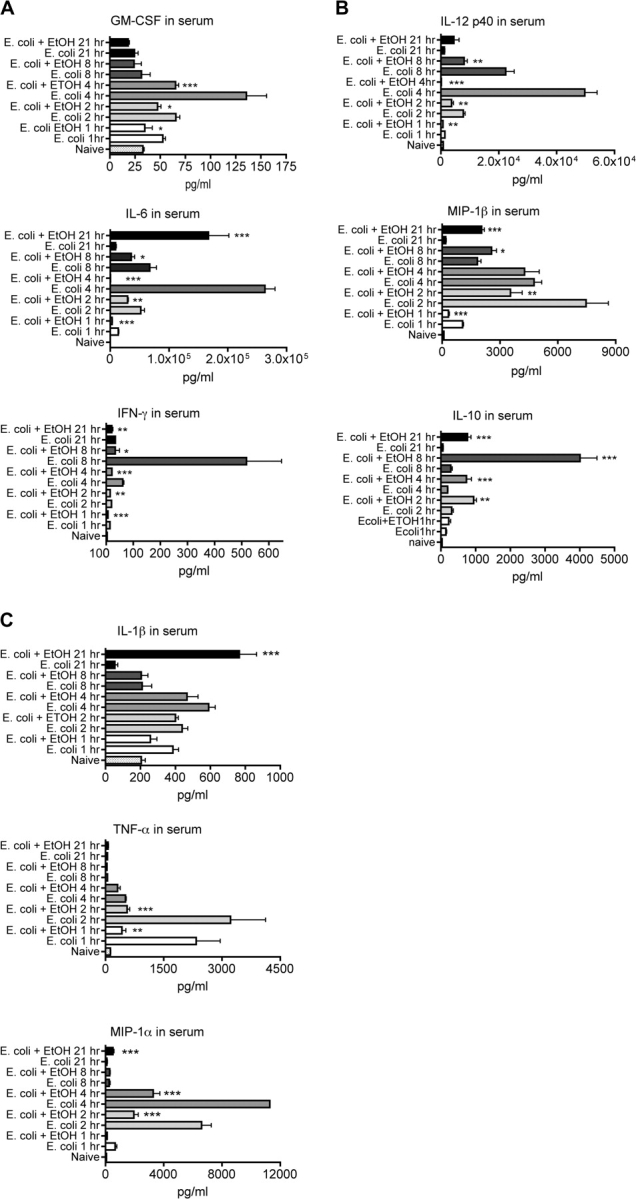

The effects of ethanol on cytokine and chemokine production at various times after E. coli challenge are indicated in Figure 5. Most of the cytokines and chemokines tested here were significantly decreased (all but interleukin [IL]-10 and IL-1β) at one or more time points by one dose of ethanol 30 min before challenge with E. coli. It is particularly interesting that for IL-1β and IL-6, two cytokines strongly associated with inflammation and acute phase responses, the concentration was increased at 21 h, even if it was significantly decreased at earlier times. This is consistent with the much greater bacterial load in the ethanol-treated mice at 21 h than at any other time for any other group (Fig. 2). It is not clear why this was not the case for other cytokines, but there may be a regulatory mechanism that prevents excessive production of these cytokines. The results are also consistent with the known sequence of cytokine production with peak concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-α produced early, interferon (IFN)-γ considerably later, and most others at an intermediate time.

FIG. 5.

Effect of ethanol on Escherichia coli-induced concentrations of selected cytokines and chemokines in serum. Values shown are means ± SEM, and the group size was 5. Significant differences between control and ethanol-treated groups at each time point (as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc) are indicated by *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

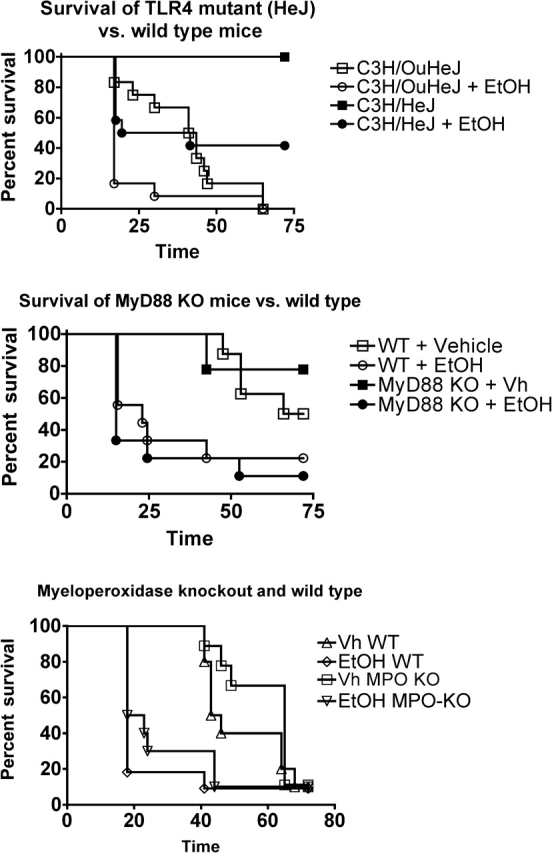

To examine the role of LPS acting though TLR4 and the role of other TLRs in this system, mutant and transgenic mice were used. The C3H/HeJ mouse strain has a mutation in TLR4 that renders it hyporesponsive to LPS (Cross et al., 1995). Therefore, this strain was used to evaluate the role of TLR4 in this experimental system. The adapter molecule MyD88 can initiate TLR signaling for all TLRs except TLR3 (Johnson et al., 2008). Thus, MyD88-knockout mice were used to assess the role of TLRs in general (except TLR3) in this experimental system. The results shown in Figure 6 demonstrate that TLR4 is required for lethality but apparently is dispensable for survival (and presumably for bacterial clearance). Ethanol decreased survival in both TLR4-mutant C3H/HeJ mice and the corresponding wild-type strain. This suggests that the inhibition of TLR4 signaling by ethanol is probably not a major cause of increased mortality because C3H/HeJ mice, which have even less TLR signaling though LPS than ethanol-treated C3H/HeOuJ mice, survive better than C3H/HeOuJ mice with or without ethanol treatment. Survival of C3H/HeOuJ mice was less than noted in Figure 1 for B6C3F1 mice. This is probably due to genetic differences between resistance-related genes in the C3H and C57Bl/6 (the wild-type mice for MyD88 knockouts and MPO knockouts were C57Bl/6). This suggests that complementary genes enhance survival in the B6C3F1 hybrid and that resistance is less effective in C57Bl/6 mice. Absence of MPO did not significantly decrease survival but caused a nonsignificant increase in survival in control groups (Fig. 6). Ethanol significantly and similarly decreased survival in both wild-type and MPO-knockout mice, suggesting that MPO is not critical for survival in this model and that MPO does not have a major role in the inhibition of survival caused by ethanol.

FIG. 6.

Survival following Escherichia coli challenge (1.5 × 108 per mouse) of control and ethanol-treated wild-type mice as well as mice with a dysfunctional mutant TLR4 gene (C3H/HeJ), knocked out MyD88 gene, or knocked out MPO. Each strain was compared with the appropriate wild-type strain. The group size in this study was 10, and results were analyzed using the log-rank test. Survival was significantly decreased (p < 0.05) in ethanol-treated groups compared with control groups within each genotype, except MyD88-knockout mice, in which there was decreased survival in ethanol-treated mice, but the decrease was not quite significant. In addition, survival was significantly increased in TLR4-mutant mice as compared with TLR4 wild-type mice in both vehicle-treated and ethanol-treated groups. In contrast, the difference in survival between wild-type mice and MyD88-knockout mice or wild-type and MPO-knockout mice was not significant for control or ethanol-treated groups.

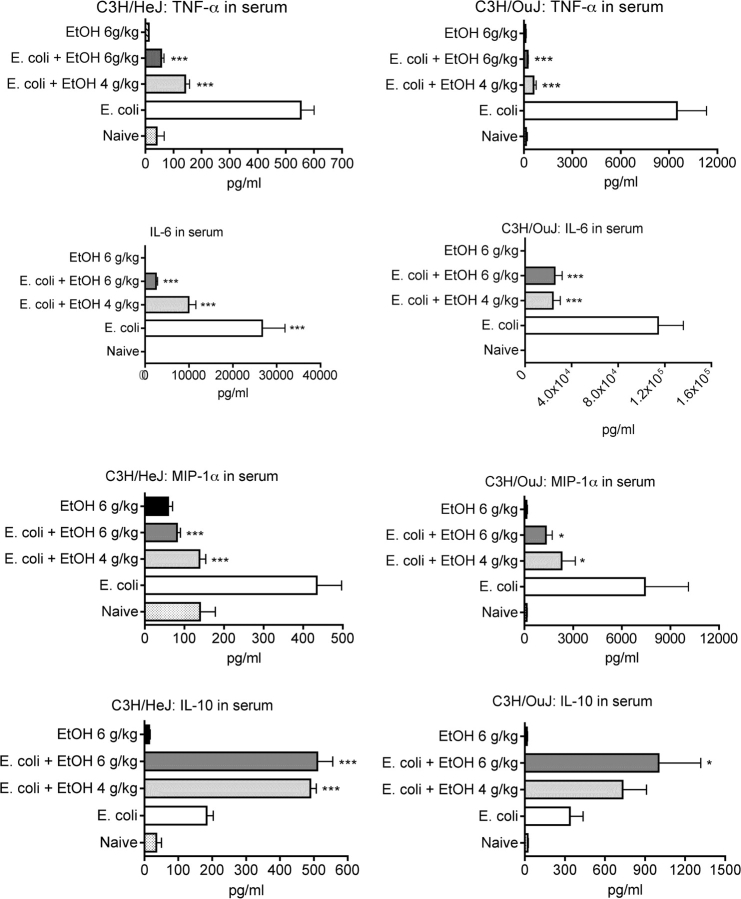

The results shown in Figure 7 indicate that LPS is a major contributor to the induction of cytokines and chemokines by E. coli. The production of cytokines and chemokines was ∼2- to 15-fold greater in C3H/HeOuJ mice than in the TLR4-mutant C3H/HeJ mice. Thus, the poor response of C3H/HeJ mice to LPS substantially decreases the response of these mice with regard to all tested cytokines and chemokines, even though gram-negative bacteria have components that can activate many receptors in addition to TLR4. The results shown in Figure 7 also indicate that ethanol alone (at 6 g/kg) does not induce these cytokines or chemokines to concentrations significantly greater than found in control mice and that ethanol at 4 g/kg significantly modulates production of most cytokines and chemokines. This is of interest because, in this mouse model for binge drinking, a dosage of 4 g/kg produces a peak blood ethanol concentration of ∼65mM (Carson and Pruett, 1996), a concentration not uncommon in humans (Jones and Holmgren, 2009; Urso et al., 1981).

FIG. 7.

Effect of ethanol on serum cytokine concentrations in wild-type and TLR4-mutant mice (C3H/HeJ) challenged with Escherichia coli. Mice were treated with vehicle (water) or ethanol (at the indicated dosages) 30 min before ip challenge with E. coli, and blood samples were taken 2 h after challenge. Values shown are means ± SEM for groups of five mice, and values significantly different from mice challenged with E. coli alone were determined by ANOVA with the Newman-Keuls post hoc. Statistical analysis was not performed for naive groups because these groups consisted of only two mice and were included only to confirm that the mice had not been inadvertently exposed to an inflammatory stimulus. Values significantly different from the E. coli-only group are indicated by *p < 0.05 or ***p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here demonstrate that ethanol-treated mice challenged ip with nonpathogenic E. coli exhibit decreased production of most proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines at early time points, decreased attraction of neutrophils to the peritoneal cavity, decreased clearance of bacteria by macrophages and neutrophils in the peritoneal cavity, and increased mortality. This suggests a scenario in which ethanol inhibits the initial inflammatory response to E. coli, which decreases the clearance of bacteria in the first few hours after challenge. After ethanol has been cleared (∼6 h after dosing) (Carson and Pruett, 1996), the increased number of bacteria induces an inflammatory response that probably contributes to the lethal outcome observed. Further studies are needed to determine the role of particular inflammatory mediators in lethal outcome in this experimental system.

Some portion of the inhibition of production of these inflammatory cytokines by ethanol could be mediated by stress hormones such as corticosterone that can be induced by ethanol. However, our recent studies indicate that ethanol-induced glucocorticoids and catecholamines do not contribute to the inhibition of cytokine production induced through TLR3 or TLR4, with the possible exception of a partial role in inhibition of IL-6 production (Glover and Pruett, 2006; Glover et al., 2009). Thus, it seems unlikely that the stress response is critical to the effects of ethanol on the pathogenesis of sepsis in this model system.

Several investigators have reported that ethanol inhibits TLR signaling (Dai et al., 2005; Szabo et al., 2007), and it seemed likely that this was involved in the decreased resistance to infection associated with acute ethanol exposure. However, the results presented here indicate that survival was enhanced in the absence of fully functional TLR4, so inhibition of TLR4 signaling is unlikely to be the major mechanism by which ethanol suppresses resistance to lethality in this experimental system. This is also suggested by the observation that ethanol decreases survival time and/or percentage in TLR4-knockout mice to a similar degree as in wild-type mice, indicating that targets other than TLR4 are involved in lethality. There are cytoplasmic (Cartwright et al., 2007) as well as membrane-bound receptors that respond to LPS and other TLRs that respond to other components of gram-negative bacteria. It is possible that in the absence of TLR4, these receptors mediate sufficient response to lead to bacterial clearance but not to a lethal overproduction of inflammatory mediators. Our results with regard to cytokine and chemokine production in TLR4-mutant and wild-type mice support this idea (Fig. 7). However, it is also possible that decreased cytokine responses in the first few hours after challenge in mice treated with ethanol allow overgrowth of bacteria which becomes lethal after the ethanol has been eliminated. This lethality may be related to TLR4-induced overproduction of inflammatory mediators, but this cannot be the only mechanism because TLR4-mutant mice treated with ethanol have a similar mortality profile as wild-type mice treated with ethanol. This strongly suggests that lethal effects of sepsis are mediated through other receptors and may not involve well-recognized inflammatory mediators because many of these are decreased in concentration in TLR4-mutant mice. Other receptors that may be involved in the pathogenesis include TLR3 and TLR2. There are reports that TLR3 contributes to lethality in sepsis by sensing the RNA released from necrotic cells during sepsis and amplifies the secondary inflammatory responses (Cavassani et al., 2008). Similarly, TLR2-dependent signaling has been shown to be critical for host resistance to bacterial infection both in animal studies and humans (Alves-Filho et al., 2009; Ferwerda et al., 2009; Mancuso et al., 2004; Murphey et al., 2008). Interestingly, ethanol also suppresses TLR3 and TLR2 signaling as reported in our previous study (Pruett et al., 2004a,c).

It remains possible that inhibition of TLR4 signaling by ethanol (or TLR4 mutation) does play an important role in decreased resistance to lower dosages of bacteria, as reported for C3H/HeJ mice (Alves-Filho et al., 2006), and that clearance of higher dosages of bacteria could be delayed (van Westerloo et al., 2005) by inhibition or lack of TLR4, even if ultimately effective. Results for enteropathogenic E. coli indicate that C3H/HeJ mice do not survive as well as wild-type mice when a low dose of bacteria is administered (Cross et al., 1995). Similar results were obtained by another group when mice were treated with a sublethal challenge dose of bacteria (Alves-Filho et al., 2006). However, when mice were treated with a greater dose of bacteria (lethal for a major percentage of wild-type mice), a much higher percentage of C3H/HeJ mice survived than wild type, as noted in our study. Another group very recently reported similar results, indicating that TLR4-mutant mice have increased resistance to a lethal outcome in E. coli sepsis caused by a high dosage of E. coli (Roger et al., 2009). Thus, it seems that the role of TLR4 in resistance to sepsis and lethality in sepsis depends on the initial challenge dose of bacteria.

In contrast to the clear protective effect of the absence of functional TLR4 in the C3H/HeJ mice, the lack of MyD88 in MyD88-knockout mice did not significantly improve survival (although there was a tendency in that direction). This leaves open the interesting possibility that the lethal effects of sepsis involve signals transmitted through the alternate adaptor molecule used by TLR4 (and by TLR3 as its only adaptor), TIR-domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon-beta (TRIF). Results indicating that mice lacking TRIF survive sepsis better than wild-type mice are consistent with this possibility (Weighardt and Holzmann, 2007). Also consistent with this idea is a recent report indicating that IFN-β (the production of which is mediated by the TRIF pathway) is required for release of high-mobility group box 1 protein and lethality in sepsis (Kim et al., 2009). We previously reported that IL-12 and IL-10 production in response to LPS is decreased almost to the lower limit of detection (Pruett et al., 2005). The finding that MyD88 is dispensable in survival of E. coli infection is consistent with findings in humans, in which individuals with a genetic defect in MyD88 were less resistant only to pyogenic bacterial infections, not other to other types of infections (von Bernuth et al., 2008). In apparent contrast to these findings, Peck-Palmer et al. (2008) reported that MyD88-knockout mice do not survive as well as wild-type mice in a cecal ligation and puncture model of sepsis. Mortality in that study was 40% in wild-type C57Bl/6 mice, whereas it was 100% in our study (Fig. 6). Thus, the difference in results may simply reflect different outcomes with high versus lower dosages of bacteria, as reported by other investigators (Alves-Filho et al., 2006; Mancuso et al., 2004) or differences between polymicrobial sepsis and E. coli sepsis.

The observation that mice lacking MPO were not significantly more susceptible to sepsis-induced mortality than wild-type mice was not entirely unexpected because similar results have been reported previously (Brovkovych et al., 2008). However, the finding that wild-type and MPO-knockout mice are similarly and significantly susceptible to ethanol-induced mortality in sepsis indicates that ethanol does not act primarily by inhibiting expression or function of MPO. We had considered this as a potential mechanism because our microarray analysis indicated that early after E. coli challenge MPO expression was decreased by ethanol (data not shown).

The effects of ethanol on survival were similar for wild-type mice, MyD88-knockout mice, TLR4-mutant mice, and MPO-knockout mice. Significantly decreased survival percentage or survival time was noted in all cases. These results indicate that inhibition of TLR4 signaling through MyD88 (which does occur) is not the major mechanism by which ethanol decreases host resistance. They also demonstrate that inhibition of MPO by ethanol is not a major mechanism for decreased resistance to sepsis in this system.

The cellular targets for decreased antibacterial effectiveness seem to be macrophages and/or neutrophils. Although the results reported here indicate that phagocytosis occurred in ethanol-treated mice (Fig. 3), it was evident that killing and degradation of the bacteria in both macrophages and neutrophils were substantially decreased (Fig. 4). Microarray results using this experimental model indicate inhibition by ethanol of a variety of genes coding for proteins involved in antibacterial effects of phagocytic cells (manuscript in preparation). Others have reported that acute ethanol exposure decreases host resistance by inhibiting upregulation of key antimicrobial effectors (e.g., nitric oxide synthase 2) (Greenberg et al., 1999). Future studies will be conducted to determine which of these are involved in the inhibition of phagocyte antimicrobial function.

There are at least two obvious potential applications suggested by these results for treatment of sepsis in humans. For E. coli-mediated sepsis, inhibition of TLR4 signaling may be a useful therapeutic approach because decreased response to TLR4 in a mutant mouse strain improved survival substantially (Fig. 6). This conclusion is consistent with another recently published report (Roger et al., 2009). This approach has the advantage of decreasing responses of several mediators of inflammation, not just one. Also, greater efficacy of therapy in sepsis might be obtained using treatments that inhibit combinations of the cytokines overproduced in the later stages of sepsis (e.g., IL-1β and IL-6) (Fig. 5) and that augment key mediators that are not known to contribute to lethality at intermediate stages of sepsis (e.g., granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating-factor) (Fig. 5). It is clear that this animal model is associated with rapid lethality, which is different from the typical course of sepsis in humans, which lasts 15–17 days, possibly due to antibiotic therapy that is not included in the mouse model (Angus et al., 2001). However, there is evidence that intervention of various types early after the diagnosis of sepsis is more effective than later intervention (Moore et al., 2009). Thus, the patterns noted in the animal model may be useful, but the results reported here would suggest that the timing of intervention is critical and will need to be determined in studies with human subjects.

In summary, the results presented here demonstrate conclusively that inhibition of TLR4 signaling, MPO expression, and MyD88 expression or function do not represent major mechanisms by which ethanol inhibits resistance to sepsis. The results instead suggest that the primary defect caused by ethanol is in the killing of phagocytosed bacteria by macrophages and neutrophils. Ethanol inhibits cytokine production early, but similar decreases in mice with a defective TLR4 did not decrease resistance to sepsis. These findings highlight how little is known about the quantitative relationships and time dependence of cytokines and chemokines with regard to host resistance to sepsis.

FUNDING

National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (R01AA009505).

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the technical assistance of Lindsay Walker.

References

- Alves-Filho JC, de Freitas A, Russo M, Cunha FQ. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling leads to neutrophil migration impairment in polymicrobial sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2006;34:461–470. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000198527.71819.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves-Filho JC, Freitas A, Souto FO, Spiller F, Paula-Neto H, Silva JS, Gazzinelli RT, Teixeira MM, Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ. Regulation of chemokine receptor by Toll-like receptor 2 is critical to neutrophil migration and resistance to polymicrobial sepsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:4018–4023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900196106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit. Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. National Center for Health Statistics Health, United States, 2007 With Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans: 2007. Hyattsville, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2007. p. 186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby GJ, Zhang P, Purcell JE, Didier PJ, Nelson S. Chronic binge ethanol consumption accelerates progression of simian immunodeficiency virus disease. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006;30:1781–1790. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brovkovych V, Gao XP, Ong E, Brovkovych S, Brennan ML, Su X, Hazen SL, Malik AB, Skidgel RA. Augmented inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and increased NO production reduce sepsis-induced lung injury and mortality in myeloperoxidase-null mice. Am. J. Physiol. 2008;295:L96–L103. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00450.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, Cook RT, Jerrells TR, Kolls JK, Nagy LE, Szabo G, Wands JR, Kovacs EJ. Acute and chronic alcohol abuse modulate immunity. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006;30:1624–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson EJ, Pruett SB. Development and characterization of a binge drinking model in mice for evaluation of the immunological effects of ethanol. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1996;20:132–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright N, Murch O, McMaster SK, Paul-Clark MJ, van Heel DA, Ryffel B, Quesniaux VF, Evans TW, Thiemermann C, Mitchell JA. Selective NOD1 agonists cause shock and organ injury/dysfunction in vivo. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007;175:595–603. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1103OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavassani KA, Ishii M, Wen H, Schaller MA, Lincoln PM, Lukacs NW, Hogaboam CM, Kunkel SL. TLR3 is an endogenous sensor of tissue necrosis during acute inflammatory events. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:2609–2621. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross A, Asher L, Seguin M, Yuan L, Kelly N, Hammack C, Sadoff J, Gemski P., Jr The importance of a lipopolysaccharide-initiated, cytokine-mediated host defense mechanism in mice against extraintestinally invasive Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:676–686. doi: 10.1172/JCI118110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza NB, Mandujano JF, Nelson S, Summer WR, Shellito JE. Alcohol ingestion impairs host defenses predisposing otherwise healthy mice to Pneumocystis carinii infection. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1995;19:1219–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Q, Zhang J, Pruett SB. Ethanol alters cellular activation and CD14 partitioning in lipid rafts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;332:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waele JJ, Hoste EA, Blot SI. Blood stream infections of abdominal origin in the intensive care unit: characteristics and determinants of death. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt) 2008;9:171–177. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferwerda B, Alonso S, Banahan K, McCall MB, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Ramakers BP, Mouktaroudi M, Fain PR, Izagirre N, Syafruddin D, et al. Functional and genetic evidence that the Mal/TIRAP allele variant 180L has been selected by providing protection against septic shock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:10272–10277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811273106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald DJ, Radek KA, Chaar M, Faunce DE, DiPietro LA, Kovacs EJ. Effects of acute ethanol exposure on the early inflammatory response after excisional injury. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:317–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilello LM, Cobean RA, Walker AP, Moore EE, Wertz MJ, Dellinger EP. Acute ethanol intoxication increases the risk of infection following penetrating abdominal trauma. J. Trauma. 1993;34:669–675. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199305000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germann G, Barthold U, Lefering R, Raff T, Hartmann B. The impact of risk factors and pre-existing conditions on the mortality of burn patients and the precision of predictive admission-scoring systems. Burns. 1997;23:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(96)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover M, Cheng B, Fan R, Pruett S. The role of stress mediators in modulation of cytokine production by ethanol. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009;239:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover M, Pruett SB. Role of corticosterone in immunosuppressive effects of acute ethanol exposure on Toll-like receptor mediated cytokine production. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1:435–442. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman SJ, MacGregor RR. Effect of acute alcohol intoxication on granulocyte mobilization and kinetics. Blood. 1978;52:551–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goral J, Kovacs EJ. In vivo ethanol exposure down-regulates TLR2-, TLR4-, and TLR9-mediated macrophage inflammatory response by limiting p38 and ERK1/2 activation. J. Immunol. 2005;174:456–463. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SS, Ouyang J, Zhao X, Parrish C, Nelson S, Giles TD. Effects of ethanol on neutrophil recruitment and lung host defense in nitric oxide synthase I and nitric oxide synthase II knockout mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1999;23:1435–1445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen R, Laine J, Lumio J, Vuento R, Syrjanen J. Obesity and smoking are factors associated with poor prognosis in patients with bacteraemia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AC, Li X, Pearlman E. MyD88 functions as a negative regulator of TLR3/TRIF-induced corneal inflammation by inhibiting activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:3988–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AW, Holmgren A. Age and gender differences in blood-alcohol concentration in apprehended drivers in relation to the amounts of alcohol consumed. Forensic. Sci. Int. 2009;188:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Kim SJ, Lee IS, Lee MS, Uematsu S, Akira S, Oh KI. Bacterial endotoxin induces the release of high mobility group box 1 via the IFN-beta signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 2009;182:2458–2466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lally KP, Cruz E, Xue H. The role of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-10 in protecting murine neonates from Escherichia coli sepsis. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2000;35:852–854. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2000.6862. discussion 855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JN, Tsai YS, Lai CH, Chen YH, Tsai SS, Lin HL, Huang CK, Lin HH. Risk factors for mortality of bacteremic patients in the emergency department. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2009;16:749–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso G, Midiri A, Beninati C, Biondo C, Galbo R, Akira S, Henneke P, Golenbock D, Teti G. Dual role of TLR2 and myeloid differentiation factor 88 in a mouse model of invasive group B streptococcal disease. J. Immunol. 2004;172:6324–6329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JC. Sepsis: rethinking the approach to clinical research. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;83:471–482. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill V, Kowal-Vern A, Fisher SG, Kahn S, Gamelli RL. The impact of substance use on mortality and morbidity from thermal injury. J. Trauma. 1995;38:931–934. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199506000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LJ, Jones SL, Kreiner LA, McKinley B, Sucher JF, Todd SR, Turner KL, Valdivia A, Moore FA. Validation of a screening tool for the early identification of sepsis. J. Trauma. 2009;66:1539–1546. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a3ac4b. discussion 1546–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphey ED, Fang G, Sherwood ER. Pretreatment with the Gram-positive bacterial cell wall molecule peptidoglycan improves bacterial clearance and decreases inflammation and mortality in mice challenged with Staphylococcus aureus. Crit. Care Med. 2008;36:3067–3073. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818c6fb7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park PH, Lim RW, Shukla SD. Involvement of histone acetyltransferase (HAT) in ethanol-induced acetylation of histone H3 in hepatocytes: potential mechanism for gene expression. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G1124–G1136. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00091.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck-Palmer OM, Unsinger J, Chang KC, Davis CG, McDunn JE, Hotchkiss RS. Deletion of MyD88 markedly attenuates sepsis-induced T and B lymphocyte apoptosis but worsens survival. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;83:1009–1018. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0807528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett SB, Schwab C, Zheng Q, Fan R. Suppression of innate immunity by acute ethanol administration: a global perspective and a new mechanism beginning with inhibition of signaling through TLR3. J. Immunol. 2004a;173:2715–2724. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett SB, Zheng Q, Fan R, Matthews K, Schwab C. Acute exposure to ethanol affects Toll-like receptor signaling and subsequent responses: an overview of recent studies. Alcohol. 2004b;33:235–239. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett SB, Zheng Q, Fan R, Matthews K, Schwab C. Ethanol suppresses cytokine responses induced through Toll-like receptors as well as innate resistance to Escherichia coli in a mouse model for binge drinking. Alcohol. 2004c;33:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett SB, Zheng Q, Schwab C, Fan R. Sodium methyldithiocarbamate inhibits MAP kinase activation through Toll-like receptor 4, alters cytokine production by mouse peritoneal macrophages, and suppresses innate immunity. Toxicol. Sci. 2005;87:75–85. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger T, Froidevaux C, Le Roy D, Reymond MK, Chanson AL, Mauri D, Burns K, Riederer BM, Akira S, Calandra T. Protection from lethal gram-negative bacterial sepsis by targeting Toll-like receptor 4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:2348–2352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808146106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G, Chavan S, Mandrekar P, Catalano D. Acute alcohol consumption attenuates interleukin-8 (IL-8) and monocyte chemoattractant peptide-1 (MCP-1) induction in response to ex vivo stimulation. J. Clin. Immunol. 1999;19:67–76. doi: 10.1023/a:1020518703050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G, Dolganiuc A, Dai Q, Pruett SB. TLR4, ethanol, and lipid rafts: a new mechanism of ethanol action with implications for other receptor-mediated effects. J. Immunol. 2007;178:1243–1249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urso T, Gavaler JS, Van Thiel DH. Blood ethanol levels in sober alcohol users seen in an emergency room. Life Sci. 1981;28:1053–1056. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90752-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Westerloo DJ, Weijer S, Bruno MJ, de Vos AF, Van't Veer C, van der Poll T. Toll-like receptor 4 deficiency and acute pancreatitis act similarly in reducing host defense during murine Escherichia coli peritonitis. Crit. Care Med. 2005;33:1036–1043. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000162684.11375.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bernuth H, Picard C, Jin Z, Pankla R, Xiao H, Ku CL, Chrabieh M, Mustapha IB, Ghandil P, Camcioglu Y, et al. Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with MyD88 deficiency. Science. 2008;321:691–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1158298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weighardt H, Holzmann B. Role of Toll-like receptor responses for sepsis pathogenesis. Immunobiology. 2007;212:715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]