Abstract

Purpose:

The clinical efficacy, different dosages, treatment schedules, and safety of azacitidine are reviewed.

Summary:

Azacitidine is the first drug FDA-approved for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes that has demonstrated improvements in overall survival and delaying time to progression to acute myelogenous leukemia. The recommended dosage of azacitidine is 75 mg/m2 daily for 7 days, with different treatment schedules validated. It appears to be well tolerated, with the most common adverse effects being myelosuppression. Several other off-label recommendations were also analyzed.

Conclusion:

Azacitidine is the first DNA hypomethylating agent approved by FDA for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes with demonstrated efficacy.

Keywords: Azacitidine, MDS, hypomethylating agents

Hypomethylating agents are a group of chemotherapeutic drugs with the capacity to induce transient DNA hypomethylation, an important mechanism in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Two hypomethylating agents approved in the United States and widely used in Europe and the rest of the world are azacitidine (5-azacytidine) and decitabine. Azacitidine has been reported to prolong survival in MDS patients. Azacitidine has been studied in different dosing schedules and combination therapies with the objective of improving the response rates in patients with MDS and acute myelogenous leukemia (AML).

Azacitidine is a nucleoside analog with a ribose structure that is incorporated into RNA and requires the activity of ribonucleotide reductase to be incorporated to DNA.1 Azacitidine is phosphorylated intracellularly to its active form, azacitidine triphosphate.2,3 Like most nucleoside analogs, azacitidine enters cells using the nucleoside transporters hENT1 and hENT2, but unlike the nucleoside analog decitabine, azacitidine does not require deoxycytidine kinase for phosphorylation.

Uridine-cytidine kinase phosphorylates azacitidine to its active form.4 Because hypermethylation of the promoters of certain tumor suppression genes is prevalent in MDS and secondary AML, it is postulated that the DNA hypomethylation induced by azacitidine, may result in the reactivation of silenced genes, restoring their cancer-suppressing functions, and inducing cellular differentiation.

Efficacy

Azacitidine as a front-line single agent

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, azacitidine was tested in a series of phase I and II trials as a classic cytotoxic agent and was found to be effective for the treatment of myeloid malignancies. In these studies, most of them involving patients with relapsed AML, azacitidine was mainly used in combinations and was administered at doses ranging from 100–750 mg/m2 with response rates ranging from 0% to 58%.4–8 In a phase I trial in which patients with relapsed leukemia received azacitidine intravenously at various schedules at doses ranging from 150–750 mg/m2, higher remission rates were observed in patients treated with the lower doses.5 Later studies performed by Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) demonstrated that azacitidine had activity in MDS and AML when given at 75 mg/m2 by intravenous infusion (CALGB 8421) or subcutaneous injection (CALGB 8921 and 9221) daily for 7 days in a 28-day cycle.9–11 The crossover phase III CALGB 9221 trial10,11 showed a significant effect of azacitidine on response rates (P < 0.0001), with an overall response rate of 60% in patients receiving azacitidine compared with 5% in those receiving only supportive care. Patients who crossed over from supportive care to azacitidine had an overall response rate of 47%, confirming that azacitidine improved overall response. Although the difference was not significant (due to the crossover design of the study), there was a marked improvement in overall survival times for patients receiving azacitidine (20 months) compared with patients receiving supportive care (14 months). These data are summarized in Table 1. The CALGB 9221study results led to the approval of azacitidine in the United States for patients with MDS.

Table 1.

Phase III trials of azacitidine as a single agent

| Study | CALGB 9221 No. (%) | Updated CALGB No. (%) | AZA-001 No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 99 | 99 | 179 |

| CR | 7 (7) | 10 (10) | 30 (17) |

| PR | 16 (16) | 1 (1) | 21 (12) |

| HI | 37 (37) | 36 (36) | 87 (49) |

| OR | 60 (60) | 47 (47) | 138 (78) |

Abbreviations: CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; HI, hematological improvement; OR, overall response.

In a second randomized phase II study (AZA-001) performed to determine the effect of azacitidine on survival, Fenaux et al compared the efficacy of azacitidine to conventional care regimens in patients with high-risk MDS.12–14 The 358 patients were randomized 1:1 to receive azacitidine or a conventional care regimen that could include supportive care, low-dose cytarabine, or induction-type chemotherapy. Azacitidine was administered subcutaneously at 75 mg/m2 daily for 7 consecutive days every 28 days for at least six cycles. A median of nine cycles of azacitidine was administered (range 4–15 cycles). The primary endpoint in the AZA-001study was overall survival. Patients treated with azacitidine had median overall survival of 24.5 months, while patients receiving conventional care had a median overall survival of 15.0 months. An analysis of the efficacy endpoints found significantly prolonged survival for patients in the azacitidine arm compared with the best supportive care or low-dose cytarabine subgroups but not compared with the intensive chemotherapy subgroup, reflecting the small number of patients preselected to receive intensive chemotherapy. The estimated 2-year survival rates were 50.8% for patients receiving azacitidine and 26.2% for patients receiving conventional care; patients in the azacitidine group also had higher rates of complete response (CR) (17% versus 8%, P = 0.015) and partial response (PR) (12% versus 4%, P = 0.0094). Likewise, the median times to disease progression, relapse after CR or PR, and death were significantly longer in the azacitidine group than in the conventional care group (14.1 months versus 8.8 months, P = 0.047). The proportion of major erythroid improvements (40% versus 11%, P < 0.0001) and major platelet improvements (33% versus 14%, P = 0.0003) based in the International Working Group 2000 criteria, were higher in the azacitidine group than in the conventional care group, but no significant difference in major neutrophil improvements was observed. The median duration of hematological response (CR, PR, and hematological improvements) was significantly longer in the azacitidine group than in the conventional care group (13.6 months versus 5.2 months, P = 0.0002). The rate of transformation to AML was lower in the azacitidine group than in the conventional care group, and the median time to AML transformation was 17.8 months in the azacitidine group compared with 11.5 months in the conventional care group. In subgroup analysis, the time to progression for the azacitidine group was significantly lower than that of the best supportive care subgroup but did not differ significantly from that of either the low-dose cytarabine subgroup or the intensive chemotherapy subgroup. Results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. In summary, the AZA-001study showed for the first time that a hypomethylating agent prolonged survival and decreased the risk of transformation to AML in patients with high-risk MDS compared with conventional therapies.

Table 2.

Results of the AZA-001 trial of azacitidine versus conventional care in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes13

| AzacitidineN= [179] | Conventional careN= [179] | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median overall survival (mo) | 24.5 | 15.0 | P ≤ 0.0001 |

| 2-year overall survival (%) | 50.8 | 26.2 | P < 0.0001 |

| Median time to AML (mo) | 17.8 | 11.5 | P ≤ 0.0001 |

| Cytogenetic overall survival (mo) | |||

| −7/del (7q) | 13.1 | 4.6 | P = 0.0017 |

| Response (%) | |||

| CR | 17 [30] | 8 [14] | P = 0.015 |

| PR | 12 [21] | 4 [7] | P = 0.0094 |

| Stable disease | 42 [75] | 36 [65] | P = 0.33 |

Notes: Definitions of hematological response and improvement were based on the International Working Group 2000 criteria for MDS.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission.

MDS patients with abnormalities in chromosome 7 (−7/del(7q)) typically have poor outcomes with traditional treatments. Follow up of the patients of the AZA-001 trial showed that patients in the azacitidine group with chromosome 7 abnormalities had a longer median overall survival time than those in the conventional care group (13.1 months versus 4.6 months, P = 0.0017); for patients with chromosome 7 abnormalities alone, the median overall survival time did not significantly differ between the two treatment groups (18.4 months versus 10.3 months); however, in patients with −7/del(7q) as part of complex karyotype there was a significant difference between the median overall survival times of the azacitidine and conventional care groups (8.3 months versus 4.2 months, P = 0.0024). Therefore, azacitidine is the only treatment, aside from hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, to confer a demonstrable survival benefit in patients with MDS, including those with −7/del(7q) cytogenetic abnormality.12–14

Patients with high-risk MDS must undergo prolonged treatment with azacitidine to improve their outcomes, with a median of three cycles needed before the first evidence of response appears. In the AZA-001study, the survival advantage was observed after three cycles of azacytidine compared with the conventional care group, with separation of Kaplan–Meier survival curves. A total of 81% of patients had achieved an evidence of response by the sixth cycle of treatment and an additional 9% of patients eventually responded to azacitidine by the ninth cycle. Furthermore, although the first response to azacitidine was a good response for over half the patients treated, a median of four additional cycles of azacitidine improved response in an additional 43% of the patients, suggesting that prolonged treatment with azacitidine may maximize the response to the agent.12,13,15

Alternative schedules and dosing

The standard dosing schedule of azacitidine for the treatment of MDS is 75 mg/m2 daily subcutaneously for 7 days in a 28-day cycle (525 mg/m2 total). Because of the difficulty of continued administration for 7 days, in a randomized trial,16 MDS patients were given azacitidine subcutaneously in one of three schedules every 4 weeks for six cycles: AZA 5-2-2 (75 mg/m2 daily for 5 days, followed by 2 days of no treatment, and then 75 mg/m2 daily for 2 days for a total dose of 525 mg/m2 per cycle), AZA 5-2-5 (50 mg/m2 daily for 5 days, followed by 2 days of no treatment, and then 50 mg/m2 daily for 5 days for a total dose of 500 mg/m2 per cycle), or AZA 5 (75 mg/m2 for 5 days for a total dose of 375 mg/m2). Most patients were FAB criteria-defined (had refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts/chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with less than 5% bone marrow blasts, 63%) or refractory anemia with excess blasts (30%). Seventy-nine patients (52%) completed six or more treatments cycles. After six cycles of treatment, hematological improvement was reported in 44% (22 of 50), 45% (23 of 51), and 56% (28 of 50) of the patients in the AZA 5-2-2, AZA 5-2-5, and AZA 5 arms, respectively. Proportions of red blood cell transfusion-dependent patients who achieved transfusion independence were 50% (12 of 24), 55% (12 of 22), and 64% (16 of 25) in the AZA 5-2-2, AZA 5-2-5, and AZA 5 arms, respectively. More than one grade 3 or 4 adverse event occurred in 84% (42 of 50), 77% (37 of 51), and 58% (29 of 50) of patients the AZA 5-2-2, AZA 5-2-5, and AZA 5 arms, respectively. All three alternative dosing regimens produced hematological improvements, red blood cell transfusion independence, and safety responses consistent with the approved azacitidine regimen. However, results suggest that the AZA 5 dosing regimen may be better tolerated with a more convenient dosing schedule than the two alternative dosing regimens.

Azacitidine in transplantation

Immediate stem cell transplantation therapy has been recommended for patients with intermediate-2 and high-risk MDS according to the International Prognostic Scoring System because of their poor outcomes and short survival times.17 A frequent type of treatment failure after stem cell transplant is disease relapse, which is very difficult to manage. The graft-versus-leukemia effect can be magnified by weaning the patient from the immunosuppressive therapy and initiating a donor lymphocyte infusion, but this strategy is of very limited value, especially because of the risk of graft-versus-host disease.

Because induction chemotherapy is not suitable for some elderly patients or patients with other contraindications, and because modifications to conditioning regimens have not improved their tolerability, azacitidine has been considered as an alternative. In a Nordic MDS study, 23 patients in CR after induction chemotherapy who were not eligible for allogenic transplantation received azacitidine at 60 mg/m2 daily subcutaneously for 5 days in a 28-day cycle until relapse or unacceptable toxicity occurred. Unfortunately, the median duration of response was only 13.5 months (range 2–49 months) with just 30% of the cases remaining in CR beyond 20 months.18 A similar study by the Groupe Francophone des myélodysplasies (GFM) is currently under way. Patients with greater than 10% blasts in the bone marrow, or greater than 5% if a nonmyeloablative transplantation is planned, may require treatment aimed at reducing the tumor burden to decrease the risk of relapse. Azacitidine has been observed to produce better responses in patients with unfavorable cytogenetics.19 In a retrospective study the outcomes of 34 MDS patients who underwent stem cell transplantation were analyzed, 14 of whom had received azacitidine at standard doses before transplantation. The Kaplan–Meier estimates for overall survival and progression-free survival between the two groups did not show clear evidence of a favorable outcome for either group, nor were there marked differences in toxic effects and other complications between the two groups. These results indicate that these two treatment options are still valid approaches but deserve further analysis.20

As mentioned, outcomes for patients with early recurrence of AML are dismal. Maintenance therapy with azacitidine may aid as an adjuvant for decreasing the recurrence rate after transplantation. Azacitidine appears to induce leukemic cell differentiation and to increase the expression of human leukemia antigen DR1 and several other tumor-associated antigens, which can increase the graft-versus-leukemia effect.21–23 Moreover, in recent studies several mechanisms have been demonstrated through which azacitidine compromises the proliferation and activation of regulatory T lymphocytes, mainly by blocking the cell cycle.24–26

In another study,27 40 patients with high-risk MDS or AML in CR without grade 3 or 4 graft-versus-host disease were assigned, on the basis of their toxicity profiles, to receive maintenance doses of azacitidine at 8 mg/m2, 16 mg/m2, or 24 mg/m2 daily for 5 days, starting on day 42 after stem cell transplantation and given in 28-day cycles. Eleven patients relapsed; two of these relapses occurred during maintenance therapy. The day 30 and day 100 nonrelapse mortality rates were 5% and 12%, respectively, with no increase in the graft-versus-host disease rates. Twelve patients received the 24 mg/m2 dose with no toxic effects for at least four cycles, suggesting that higher doses and longer periods of administration could be further investigated. In a later study including a higher dose of 32 mg/m2, thrombocytopenia limited further dose escalation, though it was reversible. A randomized controlled trial of azacitidine for 1 year versus best standard care is ongoing.28

Few treatment options are available for patients whose disease relapses after transplantation. Moreover, less than 30% of patients with relapsed MDS achieve a complete response with donor lymphocyte infusion, which has a recurrence rate close to 33%.29 Because azacitidine is able to induce response in pretransplant MDS patients, it also has been proposed as a treatment for relapse after unrelated donor peripheral stem cell transplantation.30 This recommendation came from a study of six patients with high-risk myeloid malignancies and cytogenetic relapse after transplantation who received azacitidine at a minimum dose of 25 mg/m2 for 5 days. A reduction of cytogenetic abnormalities was observed in 83% of the patients shortly after one cycle of therapy, with one patient remaining in CR 4 months after the completion of therapy. The remaining patients relapsed 30 days after the completion of therapy, reflecting activity but a short-lived response. Further investigation may be necessary to evaluate azacitidine’s activity as pre-donor lymphocyte infusion regimen.

Azacitidine in elderly patients

As previously discussed, azacitidine was the first treatment to significantly extend overall survival times in patients with high-risk MDS. It is also known that the incidence of MDS increases with age, resulting in limited treatment options – particularly for fragile patients and those older than 75 years, who cannot adequately tolerate cytotoxic therapies. Therefore, an important goal of therapy is to reduce the transfusion dependence and delay the progression of disease while maintaining a basically favorable toxicity profile. A subset analysis of the AZA-001 trial in patients older than 75 years demonstrated higher overall survival rates at 2 years in the azacitidine group (55%) than in the conventional care group (15%).31 Moreover, azacitidine generally was well tolerated in patients older than 75 years and produced transfusion independence in 44% of the patients who received it, compared with 22% in the conventional care group. Similar results have been reported elsewhere.32 It is of interest that most patients older than 75 years randomized to the conventional care regimen group received basic support only, suggesting that clinicians are generally unlikely to administer more aggressive treatments to elderly patients. Although these studies may have included a selected, relatively fit subpopulation of patients, the results of both studies clearly demonstrate azacitidine’s better response rates compared with conventional care and its acceptable safety profile for elderly patients.

Azacitidine in lower-risk MDS

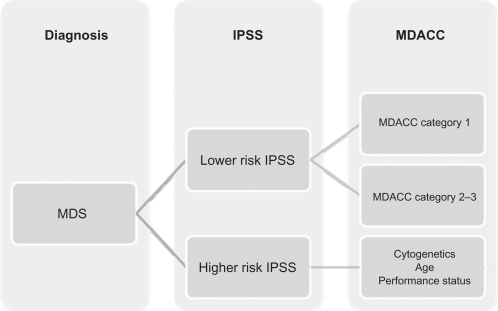

It is known that 90% of patients with an initial diagnosis of MDS present with anemia and eventually become transfusion dependent. The erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, with or without granulocyte-colony stimulating factors, can be effectively used in the initial management in low-risk MDS to reduce the need for transfusions; however, some patients with lower-risk disease may need treatments other than growth factors. The best score to predict MDS natural history is the International Prognostic Scoring System, but this system has several limitations, the most important of which is the identification of patients who may face a poor prognosis despite having lower-risk disease (low and intermediate-1 risk). A new scoring system, the MDACC score, was developed at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center to provide insight into which patients may benefit from more aggressive treatment. This was done by dividing a subset of patients into three categories depending on cytogenetics, hemoglobin levels, thrombocytopenia, age, and number of blasts in the bone marrow.33

To date, few data have been made available regarding the specific use of azacitidine in patients with lower-risk disease. The CALGB 9221 trial included 44 patients with low-risk disease in its analysis. The overall response observed in patients with low-risk MDS receiving azacitidine was 59% (9% CR, 18% PR, and 32% hematological improvement), with an overall survival of 44 months compared with 27 months for the control group. Recently, a multicenter prospective community-based study (AVIDA)34 reported a series of 52 transfusion-dependent patients. In total 42% achieved transfusion independence while on azacitidine; 67% of the patients who achieved transfusion independence did so after the second cycle of treatment. A significant 62% of patients were able to reach platelet transfusion independence; 88% of the patients who achieved platelet transfusion independence did so after the second treatment course, with minimal side effects. A more recent retrospective Italian study35 evaluated 74 patients with low-risk MDS who received azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 or 100 mg/m2 in monthly schedules subcutaneously. The overall response in these patients was 45.0% (10.0% complete response, 9.5% partial response, and 20.3% hematological response). Hematological improvements were not as strong as those reported in higher-risk populations. We believe that the MDACC score could be used to better identify the subset of patients with lower-risk disease who would benefit from early therapeutic regimens, which may help improve their overall survival times. Further analyses are warranted.

Oral azacitidine

An oral formulation of azacitidine could facilitate dosing, reduce side effects, and favor compliance. It is postulated that oral formulations of the hypomethylating agents fail because they undergo rapid catabolism by cytidine deaminase and hydrolysis in aqueous environments. A phase 0 pilot study demonstrated plasma concentrations of azacitidine that were comparable to those achieved by subcutaneous injection.36 A subsequent phase I study of 40 patients receiving the first 75 mg/m2 dose of azacitidine subcutaneously and then escalating doses (from 120 mg to 600 mg) of azacitidine orally over the next 7 days demonstrated that oral azacitidine was well tolerated with low toxicity.37 The maximum tolerated dose was 480 mg, with grade 3 and 4 diarrhea observed in two of the three patients in the 600 mg cohort. The plasma concentration range was 5% to 35% for the first and 15% to 74% in the last group. Twenty-nine percent of the patients had a complete response and 43% had stable disease after six cycles of therapy. Nevertheless, the exposures for the oral dosing regimens were lower than the historical data for subcutaneous dosing, providing the rationale for an extended schedule and twice-daily dosing in a future trial.38

Azacitidine in combination therapy

The goals of combining azacitidine with other agents are to increase the response rates and to prolong the duration of response while maintaining low rates of toxic effects. Based on models of epigenetic biology and utilizing azacitidine’s synergistic effects, several combinations of azacitidine with histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors have been assessed. The concept is based on the reactivation of suppressed anti-cancer genes.39 Valproic acid is a short-chain fatty acid HDAC inhibitor with modest activity as a single agent, but it has shown activity in combination with other hypomethylating agents.40,41 The median overall survival for patients receiving valproic acid plus azacitidine was 14.4 months, and the disease progressed in 32% of the patients. Other investigators have sought to improve this result by looking to all-trans retinoic acid, a cell differentiation agent that releases co-repressors and HDACs and induces the expression of target genes.42 This activity suggests the possibility that adding all-trans retinoic acid to the combination of azacitidine and valproic acid could potentiate the combination’s effects. Of the four patients with MDS receiving the three-drug combination, two achieved a complete response and the other two a bone marrow response.43 Another phase I study combining azacitidine with the HDAC inhibitor MS-275, showed a 44% overall response rate, with 7 of 13 patients with MDS achieving a response.44

MGCD0103 is a selective HDAC inhibitor that demonstrated promising activity as a single agent in MDS patients. In a phase I/II study, patients with relapsed/refractory MDS or AML received a standard dose of subcutaneous azacitidine plus MGCD0103 in escalating doses from 35 mg to 135 mg three times per week commencing on day five of azacitidine.45 Eleven (30%) of the patients responded, with four achieving a complete response, five achieving an incomplete response, and two achieving a partial response. The maximum tolerated dose of MGCD0103 was fixed at 90 mg because of severe nausea, vomiting, and dehydration at higher doses. Additional combination trials with other broad and more specific HDAC inhibitors are underway.

Empiric combinations of drugs with demonstrated individual activity have been evaluated in several other clinical trials. Thalidomide, an effective modulator of immune response with anti-angiogenic activity, was administered in escalating doses with a standard dose of azacitidine for 5 days.46 Of the 40 patients enrolled, 15% experienced a complete response and a hematological improvement was observed in 42%. In a phase I study with 18 patients, azacitidine was tested in combination with lenalidomide, which had demonstrated activity in MDS patients with 5q chromosome abnormalities.47 The treatment regimen was well tolerated, and the overall response rate for the 17 evaluable patients was 71%, with 41% of patients achieving a complete response. This combination was well tolerated, with a significant clinical activity encouraging for further analysis. A clinical trial is planned in which patients will receive a 75-mg/m2 dose of azacitidine from days 1 through 5 and a 10-mg dose of lenalidomide from days 1 through 21.

Preliminary data from preclinical studies of the mechanisms that may cause MDS have implicated tumor necrosis factor-α2 receptors. Therefore, a combination of etanercept, a tumor necrosis factor-α blocker, and azacitidine was evaluated in a phase II study of 23 patients. Azacitidine was given in the standard 7-day dose, while etanercept was administered at 25 mg subcutaneously twice a week for 2 weeks in a 28-day cycle. It is notable that 14 patients responded, with 28% achieving CR and 44% achieving PR.48

Targeting cell surface markers has also been studied for the treatment of MDS. CD33 is a surface marker known to be present in early hematopoietic stem cell precursors. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin, an antibody attached to a toxin that targets CD33-expressing cells, has produced good responses in hematological malignancies. Its combination with azacitidine has been assessed in early clinical trials in patients with refractory or relapsed AML or MDS.49 Median overall survival was 21 weeks, and 27% of patients achieved a complete response. Notably, 26% of patients with refractory disease had a documented complete response, and the median overall survival was 40 weeks. A prospective clinical trial is underway.

Failure of treatment

Hypomethylating agents are currently the standard therapy for the treatment of MDS, but the prognosis after a failure of the treatment, although thought to be poor, has not been well documented. Recently, a single institution retrospective study of 87 patients, had determined an expected median survival of 4.3 months, with no difference in the outcome noted between patients who progressed to AML or who did not. An important validation of MDACC risk model was done, demonstrating the utility of the model for advice in prognosis and treatment alternatives.50

Safety

Azacitidine appears to be well tolerated, with the most common grade 3 or 4 events being peripheral blood cytopenias.6 Injection site complications are the most common treatment-related non-hematological complications in subcutaneous azacitidine dosing, followed by nausea and vomiting. Although sometimes severe, myelosuppression is usually transient, with most patients recovering before their next treatment or usually managed with dosing delays (23%–29%).51

The highest proportion of adverse events occurs during the first two cycles, and the drug’s tolerability improves subsequently. The infection rates were not statistically different when comparing with basic support (RR = 1.00 [95% CI: 0.81, 1.22], P = 1.00]. The administration-related events such as nausea and vomiting occurred typically in the first week of drug delivery, resolved with antiemetics during the studies. The majority of injection site complications are typically mild erythema, and most improve after the application of warm or cold compresses to the affected area for a couple of hours.

This drug is mainly renally excreted (50%–85%), and some renal complications have been reported, although these are rare. These have included serum creatinine elevation, renal failure, renal acidosis, and death, and occurred more often when azacitidine was given in combinations with other drugs and at higher doses for non-MDS conditions.52 Azacitidine has not been studied in patients with renal impairment and MDS. In patients with decreased levels of serum bicarbonate (< 20 mEq/L) or unexplained elevations of creatinine, dose reductions may be warranted. Caution should also be used in patients with hepatic impairment. Early studies associated hepatic toxicity, including coma, with subcutaneous injections of azacitidine.6,53 All of these patients who became comatose had liver metastasis at the time of treatment. Based on these reports, azacitidine is contraindicated in patients with advanced hepatic tumors, and caution is needed when administering azacitidine to patients with other liver conditions. Also unknown are the interactions between azacitidine and microsomal enzyme inhibitors or inducers. We are unaware of any current information regarding its effect on cytochrome P450 or other drug interactions.

Women of childbearing age should be warned of azacitidine’s potential effects on the pregnancy and instructed not to breastfeed and to avoid pregnancy while receiving therapy. It is not known whether the drug is safe in children.54

Conclusion

Until recently, few treatments were available for MDS, and these yielded poor results. Azacitidine has risen as a keystone in MDS treatment because it prolongs survival; however, responses are slow and short. It has been demonstrated that azacitidine has synergistic effects with other molecules, which potentiate azacitidine’s effects. More investigational clinical trials of azacitidine are underway, and more trials are needed to improve the clinical course of this disease.

Figure 1.

Classification of myelodysplastic syndromes based on the MD Anderson Cancer Center scoring classification.

Abbreviations: IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System; MDACC, MD Anderson Cancer Center scoring system; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes.

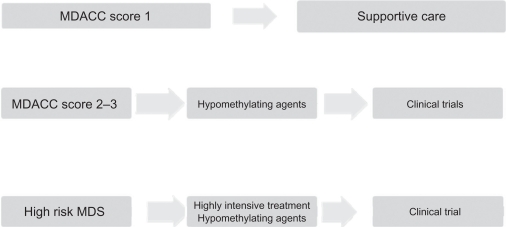

Figure 2.

Treatment algorithms of myelodysplastic syndromes at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Abbreviations: MDACC, MD Anderson Cancer Center scoring system; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Issa JP, Kantarjian HM, Kirkpatrick P. Azacitidine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(4):275–276. doi: 10.1038/nrd1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gobler AB, Leyland-Jones B. Biochemistry of azacitidine: a review. Cancer Treat Rep. 1987;71(10):959–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leone G, Teofili L, Voso MT, et al. DNA methylation and demethylating drugs in myelodysplastic syndromes and secondary leukemias. Haematologica. 2002;87(12):1324–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cataldo V, Cortes J, Quintas-Cardama A. Azacitidine for the treatment of Myelodysplastic syndrome. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9(7):875–884. doi: 10.1586/era.09.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saiki JH, Bodey GP, Hewlett JS, et al. Effect of schedule on activity and toxicity of 5-azacytidine in acute leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group Study. Cancer. 1981;47(7):1739–1742. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810401)47:7<1739::aid-cncr2820470702>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogler WR, Miller DS, Keller JW. 5 Azacitidine (NSC102816): a new drug for the treatment of myeloblastic leukemia. Blood. 1976;48(3):331–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mc Credie KB, Bodey GP, Burgess MA, et al. Treatment of acute leukemia with 5-azacytidine (NSC 102816) Cancer Chemother Rep. 1973;57(3):319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg J, Gryn J, Raza A, et al. Mitoxantrone and 5-azacytidine for refractory/relapsed ANLL or CML in blast crisis: a Leukemia Intergroup Study. Am J Hematol. 1993;43(4):286–290. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830430411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman LR, Holland JF, Demakos EP, et al. Azacitidine (Aza C) in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), CALGB studies 8421 and 8921. Ann Hematol. 1994;68:A12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverman LR, Demakos EP, Peterson BL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of azacitidine in patients with the myelodysplastic syndrome: a study of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(10):2429–2440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverman LR, McKenzie DR, Peterson BL, et al. Further analysis of trials with azacitidine in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome: studies 8421, 8921, and 9221 by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3895–3903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenaux P, Mufti G, Santini V, et al. Azacitidine treatments prolong overall survival in higher risk MDS patients compared with conventional care regimens: results of the AZA-001 phase III study. Blood. 2007;110:250. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomized, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(3):223–232. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raj K, John A, Ho A, et al. CDKN2B methylation status and isolated chromosome 7 abnormalities predict responses to treatment with 5-azacytidine. Leukemia. 2007;21:1937–1944. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverman LR, Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, et al. The effects of continued azacytidine (AZA) treatments cycles on response in higher-risk patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2008;112(11):227. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2008.118. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyons R, Cosgriff T, Modi S, et al. Hematologic response to three alternative dosing schedules of azacitidine in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(11):1850–1856. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cutler CS, Lee SJ, Greenberg P, et al. A decision analysis of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for the myelodysplastic syndromes: delayed transplantation for low-risk myelodysplasia is associated with improved outcomes. Blood. 2004;104:579–585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grovdal M, Khan R, Aggerholm A, et al. Maintenance treatment with 5-azacitidine for patients with high-risk MDS or acute myeloid leukemia following MDS in complete remission after induction chemotherapy. Blood. 2008;112:223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08235.x. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravandi F, Jean-Pierre I, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Superior outcome with hypomethylating therapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and chromosome 5 and 7 abnormalities. Cancer. 2009;115:5746–5751. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Field T, Perkins J, Alsina M, et al. Pre-transplant 5-azacitidine may improve outcome of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2006;108:3664. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinto A, Maio M, Attadia V, et al. Modulation of HLA-DR antigen expression in human myeloid leukemic cells by cytarabine and 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine. Lancet. 1984;2:867–868. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90900-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coral S, Sigalotti L, Gasparollo A, et al. Prolonged up regulation of the expression of HLA class I antigen and co stimulatory molecules on melanoma cells treated with 5-aza-2’-deoxycitidine. J Immunother. 1999;22:16–24. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jabbour E, Giralt S, Kantarjian H, et al. Low-dose azacitidine after allogenic stem cell transplantation for acute leukemia. Cancer. 2009;115:1899–905. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HP, Leonard WJ. CREB/ATF-dependent T cell receptor-induced FoxP3 gene expression: a role for DNA methylation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1543–1551. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang KF, He CX, Zeng GL, et al. Induction of MHC class I–related chain B (MICB) by 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez-Abarca L, Gutierrez-Cosio S, Santamaria C, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of 5-azacytidine: potential role in the transplant setting. Blood. 2010;115:107–121. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Lima M, Padua L, Giralt S, et al. A dose schedule finding study of maintenance therapy with low-dose 5-azacitidine after allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for high risk AML or MDS. Blood. 2007;110:3012. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Lima, Padua L, Giralt S, et al. Maintenance therapy with low-dose Azacitidine after allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for relapsed or refractory AML or MDS: dose and schedule finding study. Blood. 2008;112:1134. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25500. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins RH, Jr, Shpilberg O, Drobyski WR, et al. Donor leukocyte infusions in 140 patients with relapsed malignancy after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:433–444. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosetti J, Shadduck R, Thatikonda C, et al. Low-dose Azacitidine for relapse of MDS/AML after unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;110:5034. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seymour J, Fenaux P, Silverman L, et al. Effects of azacitidine vs conventional care regimens in elderly (>75 years) patients with myelodysplastic syndromes from the AZA-001 survival trial. Blood. 2008;112:3629. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Itzykson R, Thepot S, Achour B, et al. Azacytidine in MDS in patients >80 years: results of the French ATU Program. Blood. 2009;114:1773. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Manero G, Shan J, Faderl S, et al. A prognostic score for patients with lower risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia. 2008;22:538–543. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grinblatt D, Narang M, Malone J, et al. Treatment of patients with low-risk myelodysplastic syndromes receiving azacitidine who are enrolled in AVIDA, a longitudinal patient registry Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts).2008112164618502832 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Musto P, Maurillo L, Spagnoli A, et al. Azacitidine for the treatment of lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer. 2010;116:1485–1494. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia-Manero G, Stoltz ML, Ward MR, et al. A pilot pharmacokinetic study of oral azacitidine. Leukemia. 2008;22:1680–1684. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-Manero G, Gore S, Skikne B, et al. A phase I, open–label, dose escalation study to evaluate safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics of oral azacitidine in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:117. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacBeth K, Laille E, Ning Y, et al. A comparative pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic evaluation of azacitidine following subcutaneous and oral administration in subjects with Myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myelogenous leukemia, results from a phase I study. Blood. 2009;114:1772. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian HM, Sanchez-Gonzalez B, et al. Phase I/II study of the combination of 5-aza-2’deoxycitidine with valproic acid in patients with leukemia. Blood. 2006;108(10):3271–3279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-009142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian HM, Sanchez-Gonzalez B, et al. Phase 1/2 study of the combination of 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine with valproic acid in patients with leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:3271–3279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-009142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voso MT, Santini V, Finelli C, et al. Valproic acid therapeutic plasma levels may increase 5-azacytidine efficacy in higher risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(15):5002–5007. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silverman LR, Verma A, Odchimar-Reissig R, et al. A phase I/II study of vorinostat, an oral histone deacetylase inhibitor, in combination with azacitidine in patients with the myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Initial results of the phase I trial: a New York Cancer Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26 abstract 7000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soriano A, Yang H, Faderl S, et al. Safety and clinical activity of the combination of 5-azacytidine, valproic acid, and all-trans retinoic acid in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2006;110(7):2302–2308. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-078576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gore S, Jiemjit A, Silverman LR, et al. Combined methyltransferase/histone deacetylase inhibition with 5-azacitidine and MS-275 in patients with MDS, CMMoL and AML: clinical response, histone acetylation and DNA damage. Blood. 2006;108(11):517. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia-Manero G, Assouline S, Cortes J, et al. Phase I study of the oral isotype specific histone deacetylase inhibitor MGCD0103 in leukemia. Blood. 2008;112(4):981–989. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-115873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raza A, Mehdi M, Mumtaz M, et al. Combination of 5-Azacitidine and thalidomide for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2008;113:1596–1604. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sekeres M, List F, Cuthbertson D, et al. Final results from a phase I combination study of lenalidomide and azacitidine in patients with higher-risk MDS. Blood. 2008;112:221. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holsinger AL, Ramakishnan A, Storer B, et al. Therapy of Myelodysplastic Syndrome with azacitidine given in combination with etanercept: a phase II study. Blood. 2007;110:1452. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michaelis L, Shafer D, Barton K, et al. Azacitidine and low-dose gemtuzumab ozogamicin for the treatment of poor-risk AML and MDS including relapsed refractory disease. Blood. 2009;114:1034. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jabbour E, Garcia-Manero G, Batty N, et al. Outcome of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome after failure of decitabine therapy. Cancer. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25247. In press. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.25247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santini V, Fenaux P, Mufti G, et al. Management and supportive care measures for adverse events in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes treated with azacitidine. Eur J Haematol. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01456.x. In press. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600–0609.2010.01456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peterson BA, Collins AJ, Vogelzang NJ, et al. 5-Azacytidine and renal tubular acidosis. Blood. 1981;57(1):182–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bellet RD, Mastrangelo MJ, Engstrom PF, et al. Clinical Trial with subcutaneously administered 5-azacytidine (NSC-102816) Cancer Chemother Rep. 1974;58:217–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vidaza (azacitidine) package insert. Boulder, CO: Celgene Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]