Abstract

Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) is a perfluoroalkyl acid (PFAA) and a persistent environmental contaminant found in the tissues of humans and wildlife. Although blood levels of PFOS have begun to decline, health concerns remain because of the long half-life of PFOS in humans. Like other PFAAs, such as, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), PFOS is an activator of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPARα) and exhibits hepatocarcinogenic potential in rodents. PFOS is also a developmental toxicant in rodents where, unlike PFOA, its mode of action is independent of PPARα. Wild-type (WT) and PPARα-null (Null) mice were dosed with 0, 3, or 10 mg/kg/day PFOS for 7 days. Animals were euthanized, livers weighed, and liver samples collected for histology and preparation of total RNA. Gene profiling was conducted using Affymetrix 430_2 microarrays. In WT mice, PFOS induced changes that were characteristic of PPARα transactivation including regulation of genes associated with lipid metabolism, peroxisome biogenesis, proteasome activation, and inflammation. PPARα-independent changes were indicated in both WT and Null mice by altered expression of genes related to lipid metabolism, inflammation, and xenobiotic metabolism. Such results are similar to studies done with PFOA and are consistent with modest activation of the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), and possibly PPARγ and/or PPARβ/δ. Unique treatment-related effects were also found in Null mice including altered expression of genes associated with ribosome biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and cholesterol biosynthesis. Of interest was up-regulation of Cyp7a1, a gene which is under the control of various transcription regulators. Hence, in addition to its ability to modestly activate PPARα, PFOS induces a variety of PPARα-independent effects as well.

1. Introduction

Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) are stable man-made perfluorinated organic molecules that have been utilized since the 1950s in the manufacture of a variety of industrial and commercial products suchas fire fighting foams, fluoropolymers for the automobile and aerospace industry, paper food packaging, stain-resistant coatings for carpet and fabric, cosmetics, insecticides, lubricants, and nonstick coatings for cookware. One such PFAA, perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), was identified nearly a decade ago as a persistent organic pollutant which could also be found in the tissues of wildlife throughout the globe [2]. Since that time, a number of perfluorinated sulfonic and carboxylic acids of varying chain length have been shown to be persistent and ubiquitous environmental contaminants. Some of these compounds are also commonly identified in the tissues of humans and wildlife with the 8-carbon PFAAs, PFOS and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), being the most frequently reported in biomonitoring studies (for reviews, see [3, 4]). In recent years, blood levels of PFOS and PFOA have gradually begun to decline in the general population [5, 6]. This is due in part to a production phase out of PFOS by its principal U.S. manufacturer as well as a commitment by key manufacturers of perfluorinated chemicals to reduce the product content and emissions of PFOA, and related chemistries, under the EPA 2010/2015 PFOA Stewardship Program (http://www.epa.gov/oppt/pfoa/pubs/stewardship/index.html). Nevertheless, certain PFAAs are likely to remain of concern for years to come due to their environmental persistence and long biological-half lives [7].

PFOS and PFOA are associated with toxicity in laboratory animals at blood levels that are approximately 2-3 orders of magnitude above those normally observed in humans. This includes hepatomegaly and liver tumors in rats and mice as well as pancreatic and testicular tumors in rats (for review see [4]). Teratogenic activity has also been observed in rats and mice, however, such findings have been limited to maternally toxic doses of PFOS [8], whereas, both PFOS and PFOA have been shown to alter growth and viability of rodent neonates at lower doses [4]. Recent epidemiologic data suggests that typical exposures to these compounds may alter fetal growth and fertility in humans [9–13]. These studies, however, lack consistency with regard to either compound activity or measured end point; therefore, alternative explanations for such findings have been suggested [14]. Moreover, a recent study of individuals exposed to PFOA in drinking water at levels that were approximately two orders of magnitude higher than the general population did not show an effect on average birth weight or the incidence of low birth weight infants [15].

The mode of action related to PFAA toxicity in rodents is not fully understood. As a class of chemicals, PFAAs activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) [16–18], and chronic activation of this nuclear receptor is thought to be responsible for the liver enlargement and hepatic tumor induction found in laboratory animals [19]. However, activation of PPARα is not thought to be a relevant mode of action for hepatic tumor formation in humans [20–25], although this assumption has been challenged recently [26]. This does not, however, rule out the possibility that certain PFAAs could have an adverse effect on development since activation of PPARα has been shown to play a role in PFOA-induced neonatal loss in mice [27]. In addition, PPARα-independent modes of action are also likely for various PFAAs. Unlike prototypical activators of PPARα, such as, the fibrate class of pharmaceuticals, PFOA can induce fatty liver in wild-type mice [28]. PFOA can also induce hepatomegaly in PPARα-null mice [27, 29, 30] and is capable of activating the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) [31–33]. Moreover, PFOS can induce neonatal toxicity in the PPARα-null mouse [34].

In the current study, we used global gene expression profiling to assess the transcriptional changes induced by PFOS in the liver of wild-type and PPARα-null mice. The data were compared to results previously published by our group for PFOA and Wy-14,643, a commonly used agonist of PPARα [1]. Our goal was to identify both PPARα-dependent and independent changes induced by PFOS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Dosing

Studies were approved by the U.S. EPA ORD/NHEERL Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The facilities and procedures used followed the recommendations of the 1996 NRC “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals,” the Animal Welfare Act, and the Public Health Service Policy on the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

PPARα-null (Null) mice (129S4/SvJae-P p a r a tm1Gonz/J, stock no. 003580) and wild-type (WT) mice (129S1/SvlmJ, stock no. 002448) were initially purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained as an inbred colony on the 129/Sv background at the U.S. EPA, Research Triangle Park, NC. Animals were housed 5 per cage and allowed to acclimate for a period of one week prior to the conduct of the study. Food (LabDiet 5P00 Prolab RHM3000, PMI Nutrition International, St. Louis, MO) and municipal tap water were provided ad libitum. Animal facilities were controlled for temperature (20–24°C), relative humidity (40%–60%), and kept under a 12 hr light-dark cycle. The experimental design matched that of our previous study [1]. PPARα-null and wild-type male mice at 6–9 months of age were dosed by gavage for 7 consecutive days with either 0, 3, or 10 mg/kg PFOS (potassium salt, catalog no. 77282, Sigma Aldrich, St, Louis, MO) in 0.5% Tween 20. Five biological replicates consisting of individual animals were included in each dose group. Dose levels were based on unpublished data from our laboratory and reflect exposures that produce hepatomegaly in adult mice without inducing overt toxicity. Animals utilized for RT-PCR analysis were taken from a separate set of WT and Null mice. PCR dose groups consisted of 4 animals per group and were treated for seven-days with either 10 mg/kg/day PFOS, 3 mg/kg/day PFOA (ammonium salt, catalog no. 77262, Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.5% Tween 20, or 50 mg/kg/day Wy-14,643 (catalog no. C7081, Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.5% methylcellulose, along with vehicle controls. All dosing solutions were freshly prepared each day. At the end of the dosing period, animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and tissue collected from the left lobe of the liver for preparation of total RNA. Tissue prepared for histology was collected from the same group of animals used for microarray analysis and was taken from a section adjacent to that utilized for RNA preparation.

2.2. RNA Preparation

Collected tissue (≤50 mg) was immediately placed in 1 mL RNAlater (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX) and stored at −20°C. RNA preparations for microarray analysis were then completed by homogenizing the tissue in 1 mL TRI reagent (Sigma Chemical) followed by processing through isopropanol precipitation according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting pellets were washed with 80% ethanol and resuspended in RNase free water (Applied Biosystems/Ambion). Preparations were further purified by passing approximately 100 μg per sample through RNeasy spin columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA for PCR analysis was prepared using the mirVANA miRNA isolation kit (Applied Biosystems/Ambion) according to the manufacturer's protocol without further enrichment for small RNAs. All samples used in the study were quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) and quality evaluated using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). Only samples with an RNA Integrity number of at least 8.0 (2100 Expert software, version B.01.03) were included in the study [35].

2.3. Histological Examination of Tissue

Following overnight fixation in Bouins fixative, collected tissue was washed three times in PBS, dehydrated to 70% ethanol, and stored at 4°C until use. On the day of embedding, the tissue was dehydrated through an ethanol gradient to 100% ethanol and paraffin embedded using standard techniques. Five micron sections were then prepared using a rotary microtome prior to routine staining with hematoxylin and eosin.

2.4. Gene Profiling

Microarray analysis was conducted at the U.S. EPA NHEERL Toxicogenomics Core Facility using Affymetrix GeneChip 430_2 mouse genome arrays according to the protocols recommended by the manufacturer (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Biotin-labeled cRNA was produced from 5 ug total RNA using Enzo Single-Round RNA Amplification and Biotin Labeling System (Cat. no. 42420-10, Enzo Life Sciences Inc, Farmingdale, NY), quantified using an ND-1000 spectrophotometer, and evaluated on a 2100 Bioanalyzer after fragmentation. To minimize technical day to day variation, labeling and hybridization for all samples were conducted as a single block. Following overnight hybridization at 45°C in an Affymetrix Model 640 GeneChip hybridization oven, the arrays were washed and stained using an Affymetrix 450 fluidics station and scanned on an Affymetrix Model 3000 scanner. Raw data (Affymetrix Cel files) were obtained using Affymetrix GeneChip Operating Software (version 1.4). This software also provided summary reports by which array QA metrics were evaluated including average background, average signal, and 3′/5′ expression ratios for spike-in controls, β-actin, and GAPDH. Only arrays of high quality based on low background levels as well as expected 3′/5′ expression ratios for the spike-in controls, β-actin, and GAPDH were included in the study. Data are available through the Gene Expression Omnibus at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) as accession numbers GSE22871.

2.5. PCR Confirmation of Results

Real-time PCR analysis of selected genes was conducted using 2 micrograms of total RNA. All samples were initially digested using 2 units DNaseI (no. M6101, Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) for 30 min at 37°C followed by 10 min at 65°C in a buffer containing 40 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgSO4, and 1 mM CaCl2. The RNA was then quantified using a Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA assay kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (no.R11490, Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) and approximately 1.5 ug RNA reverse transcribed using a High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit according to the provided protocol (no. 4322171, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Amplification was performed on an Applied Biosystems model 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System in duplicate using 25 ng cDNA and TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (no.4304437, Applied Biosystems) in a total volume of 12 μL according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh, Entrez no. 14433), which was uniformly expressed among all samples (cycle threshold deviation less than 0.35), was used as an endogenous reference gene. The following TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems) were included in the study: Gapdh (no. Mm99999915_g1), Srebf2 (no. Mm01306293_m1), P p a r g c1a (Mm0047183_m1), Nfe2l2 (Mm00477784_m1), Ndufa5 (Mm00471676), Lss (no. Mm00461312_m1), Cyp4a14 (no. Mm00484132_m1), Cyp7a1 (no. Mm00484152_m1), and Cyp2b10 (no. Mm00456591_m1). Fold change was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method of Livak and Schmittgen [36].

2.6. Data Analysis

Body and liver weight data were analyzed by strain using a one-way ANOVA. Individual treatment contrasts were assessed using a Tukey Kramer HSD test (P ≤ .05) (JMP 7.0 (SAS, Cary, NC). Microarray data were summarized, background adjusted, and quantile normalized using Robust Multichip Average methodology (RMA Express, ver. 1.0). Prior to statistical analysis, microarray data were filtered to remove probe sets with weak or no signal. Data were analyzed for each strain using a one-way ANOVA across dose (Proc GLM, SAS ver. 9.1, Cary, NC). Individual treatment contrasts were evaluated using a pairwise t-test of the least square means. Significant probe sets (P ≤ .0025) were evaluated for relevance to biological pathway and function using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (http://analysis.ingenuity.com/) and DAVID functional annotation software [37]. Duplicate probe sets were resolved using minimum P-value. Data were further evaluated without statistical filtering using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) software available from the Broad Institute [38]. Hierarchical clustering and heat maps were generated using Eisen Lab Cluster and Treeview software (version 2.11).

3. Results

3.1. Necropsy and Histopathology

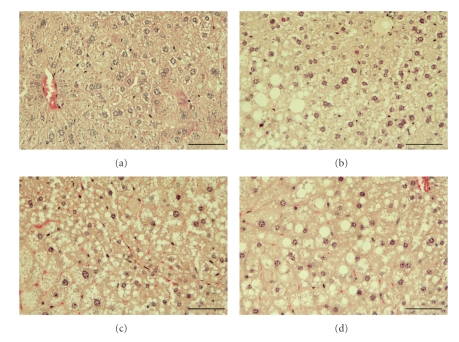

Liver weight increased at the highest dose of PFOS in both WT and Null animals (Table 1). Histological changes were also noted. Vacuole formation was observed in tissue sections from treated WT mice, as well as in sections from control and treated Null mice (Figure 1). The origin of these vacuoles was not fully apparent. Kudo and Kawashima [28] reported that chronic exposure to PFOA can induce fatty liver in mice due to altered triglyceride transport; hence, vacuolization in the current study may be the result of similar changes in WT mice. In Null mice, vacuole formation may also reflect increased triglyceride retention due to reduced hepatic fatty acid catabolism. Furthermore, our group has suggested that a certain degree of vacuolization may be unrelated to triglyceride retention in PFOA-exposed Null mice [29]. It is possible therefore, that hepatic vacuolization might be associated with the liver weight increase observed in treated Null animals.

Table 1.

Average body weight and liver weight of control and PFOS-treated mice on the day of tissue collection.1

| Dose group | WT | Null | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight | Total liver weight | Relative liver weight | Body weight | Total liver weight | Relative liver weight | |

| 0 mg/kg | 28.3 ± .0 | 1.21 ± 0.17 | 0.043 ± 0.014 | 30.3 ± 1.3 | 1.04 ± 0.06 | 0.034 ± 0.003 |

| 3 mg/kg | 26.2 ± 1.5 | 1.12 ± 0.18 | 0.043 ± 0.002 | 28.0 ± 1.2 | 1.20 ± 0.05 | 0.043 ± 0.001 |

| 10 mg/kg | 31.4 ± 1.5 | 1.98 ± 0.11* | 0.062 ± 0.003* | 30.2 ± 1.7 | 1.48 ± 0.16* | 0.049 ± 0.012* |

1Data are mean ± SE, *Significantly different than control (P ≤ .05).

Figure 1.

Hematoxylin-and eosin-stained tissue sections from control and PFOS treated mice. Control WT and Null mice are shown in panels (a) and (b), respectively. WT and null mice treated with 10 mg/kg/day PFOS are shown in panels (c) and (d), respectively. Vacuole formation was observed in sections from treated WT mice, and in sections from control and treated Null mice. Mice exposed to 3 mg/kg/day PFOS were similar to controls (data not shown). Bar = 50 μm.

3.2. Gene Profiling

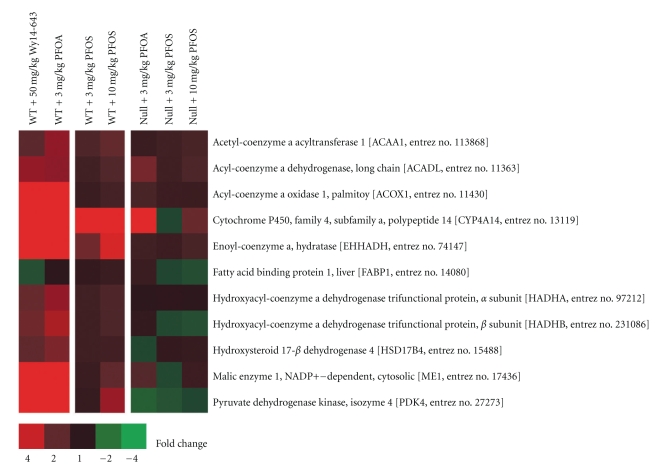

Based on the number of genes significantly altered by PFOS (P ≤ .0025), gene expression changes in WT mice were more evident at the higher dose of PFOS compared to the lower dose. This was in contrast to changes observed in Null mice where the number of transcripts influenced by PFOS was similar across either dose group. Hence, certain PPARα-independent effects were found to be robust in Null mice even at the lowest dose of PFOS. This pattern of gene expression also varied from that previously observed by our group for PFOA where only moderate changes were found in Null mice compared to WT animals [1] (Table 2). By examining the expression of a small group of well characterized markers of PPARα transactivation, PFOS also appeared to be a less robust activator of murine PPARα than PFOA (Figure 2), a conclusion formerly reported by others [18, 39, 40].

Table 2.

Number of fully annotated genes altered by PFOS, PFOA1, or Wy-14,6431 in wild-type and PPARα-null mice (P ≤ .0025)2.

| POS | PFOA | Wy 14,643 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 mg/kg/day | 10 mg/kg/day | 3 mg/kg | 50 mg/kg/day | |

| Wild-type | 81 | 906 | 879 | 902 |

| PPARα-null | 630 | 808 | 176 | 10 |

1From Rosen et al. (2008), 2 Based on Ingenuity Pathways Analysis database.

Figure 2.

Expression of a group of well characterized markers of PPARα transactivation in WT and Null mice. The response to PFOS in WT mice was less robust than that previously observed for either PFOA or Wy14,643. Red or green correspond to average up- or down- regulation, respectively.

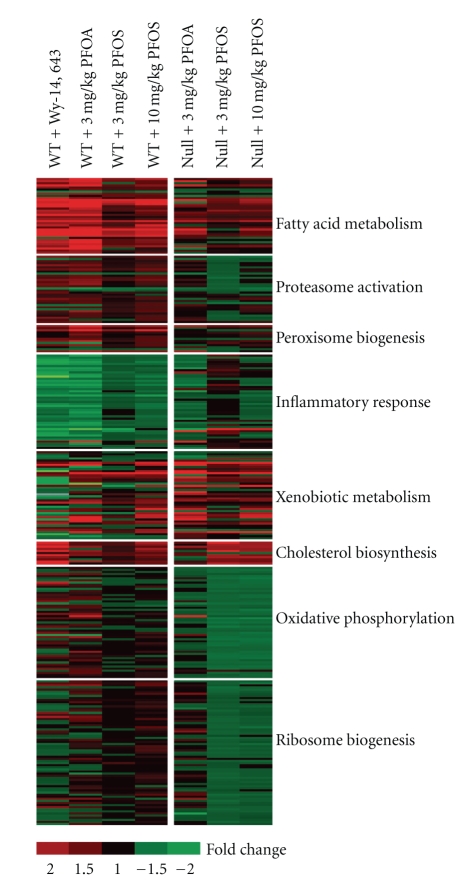

In WT mice, PFOS modified the expression of genes related to a variety of PPARα-regulated functions including lipid metabolism, peroxisome biogenesis, proteasome activation, and the inflammatory response. Genes affected in both WT and Null mice consisted of transcripts related to lipid metabolism, inflammation, and xenobiotic metabolism, including the CAR inducible gene, Cyp2b10. It should be stressed, however, that those changes associated with the inflammatory response in Null mice were modest and were only apparent within the context of similar but more robust changes in WT mice. Several categories of genes were also uniquely regulated in Null mice by PFOS including up-regulation of genes in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, along with modest down-regulation of genes (<1.5 fold change) associated with oxidative phosphorylation and ribosome biogenesis (Figure 3). Changes related to ribosome biogenesis were particularly subtle and were identified by the computational method provided by GSEA using the complete set of expressed genes without statistical filtering. This approach allowed for an a priori set of genes to be evaluated for significant enrichment without regard for the statistical significance of individual genes. Among the changes uniquely induced by PFOS in Null mice was up-regulation of Cyp7a1, an important gene related to bile acid/cholesterol homeostasis. Data for individual genes are provided in Tables 3–10.

Figure 3.

Functional categories of genes modified by PFOS in WT and Null mice. In WT mice, PFOS altered the expression of genes related to a variety of PPARα-regulated functions including lipid metabolism, peroxisome biogenesis, proteasome activation, and the inflammatory response. Genes affected in both WT and Null mice consisted of transcripts related to lipid metabolism, inflammation, and xenobiotic metabolism. Several categories of genes were uniquely regulated by PFOS in Null mice including up-regulation of genes in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway as well as modest down-regulation of genes associated with oxidative phosphorylation and ribosome biogenesis. Red or green corresponds to average up- or down- regulation, respectively.

Table 3.

Average fold change for genes related to lipid metabolism in wild-type and PPARα-null male mice following a seven-day exposure to Wy-14,6431, PFOA1, or PFOS.

| WT | Null | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene name | Entrez no. | Wy14,643 50 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg |

| ACAA1 | acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 1 |

113868 | 1.89 | 2.92 | 1.61 | 2.10** | 1.22 | 1.37 | 1.53* |

| ACAA1B | acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 1B |

235674 | 2.38 | 2.70 | 1.49 | 1.40** | 3.00 | 1.09 | 1.19* |

| ACAD10 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, member 10 |

71985 | 1.51 | 2.39 | −1.18 | 1.38** | −1.01 | 1.05 | 1.20* |

| ACADL | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, long chain |

11363 | 3.03 | 2.86 | 1.40 | 1.68** | 2.50 | 1.34 | 1.59** |

| ACADM | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, C-4 to C-12 |

11364 | 1.70 | 1.30 | 1.21 | 1.31** | 1.06 | 1.11 | 1.10 |

| ACADS | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, C-2 to C-3 |

66885 | 1.03 | 1.52 | 1.22 | 1.31* | −1.13 | −1.12 | −1.08 |

| ACADSB | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short/branched |

66885 | −1.56 | −1.64 | −1.04 | −1.39** | −1.26 | 1.00 | −1.23 |

| ACADVL | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, very long chain |

11370 | 1.92 | 1.80 | 1.44 | 1.49** | 1.16 | 1.04 | 1.12 |

| ACAT1 | acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1 |

101446 | −1.01 | 1.10 | 1.45 | 1.36* | −1.55 | −1.05 | −1.17 |

| ACAT2 | acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2 |

110460 | 2.59 | 1.68 | 1.14 | 1.34* | 1.26 | 1.58 | 1.69** |

| ACOT1 | acyl-CoA thioesterase 1 | 26897 | 19.48 | 73.06 | 3.27 | 6.82** | 2.95 | 1.53 | 2.02 |

| ACOT3 | acyl-CoA thioesterase 3 | 171281 | 2.55 | 32.83 | 2.42 | 6.41** | −1.59 | 1.46 | 1.86 |

| ACOT2 | acyl-CoA thioesterase 2 | 171210 | 3.83 | 19.29 | 1.91 | 7.32** | 1.78 | 1.25 | 1.52 |

| ACOX1 | acyl-CoA oxidase 1 | 11430 | 5.65 | 7.17 | 1.23 | 1.49** | 1.51 | 1.30 | 1.29** |

| ACSL1 | acyl-CoA synthetase long- chain member1 |

14081 | 1.34 | 2.36 | 1.28 | 1.36** | 1.01 | 1.31 | 1.30 |

| ACSL3 | acyl-CoA synthetase long- chain member3 |

74205 | 2.25 | 1.90 | 1.28 | 1.69** | 1.11 | 1.77 | 1.63 |

| ACSL4 | acyl-CoA synthetase long- chain member4 |

50790 | 1.95 | 2.00 | 1.03 | 1.42* | 1.51 | 1.34 | 1.29 |

| ACSL5 | acyl-CoA synthetase long- chain member5 |

433256 | 3.06 | 2.76 | 1.24 | 1.31** | 1.38 | 1.23 | 1.28 |

| ALDH1A1 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 1, member A1 |

11668 | 1.56 | 1.59 | 1.07 | 1.12** | 1.22 | 1.16 | 1.17 |

| ALDH1A7 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 1, A7 | 26358 | 1.83 | 1.86 | 1.12 | 1.24* | 1.55 | 1.26 | 1.35 |

| ALDH3A2 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 3, member A2 |

11671 | 3.65 | 7.72 | 2.10 | 3.80** | 2.30 | 1.73 | 2.20** |

| ALDH9A1 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 9, member A1 |

56752 | 1.80 | 1.91 | 1.27 | 1.50** | 1.21 | 1.05 | 1.11* |

| CPT1B | carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1B (muscle) |

12896 | 2.29 | 1.50 | 1.23 | 2.69** | −1.00 | 1.13 | 1.11 |

| CPT2 | carnitine palmitoyltransferase II | 12896 | 1.33 | 2.54 | 1.58 | 2.03** | 1.44 | 1.15 | 1.34 |

| CYP4A14 | cytochrome P450, 4, a, polypeptide 14 |

13119 | 75.38 | 103.48 | 11.26 | 12.28** | 12.75 | −1.09 | 2.22 |

| DCI | dodecenoyl-CoA delta isomerase |

13177 | 2.91 | 4.55 | 1.90 | 2.38** | 1.99 | 1.04 | 1.38* |

| ECH1 | enoyl CoA hydratase 1, peroxisomal |

51798 | 3.27 | 5.23 | 1.93 | 2.49** | 2.10 | 1.16 | 1.39 |

| EHHADH | enoyl-CoA, hydratase | 74147 | 27.89 | 22.11 | 2.37 | 4.34** | 1.37 | 1.32 | 1.52* |

| FABP1 | fatty acid binding protein 1, liver | 14080 | −1.27 | 1.02 | 1.11 | 1.24** | 1.25 | −1.09 | −1.23 |

| HADHA | Trifunctional protein, alpha unit | 97212 | 2.13 | 2.95 | 1.37 | 1.65** | 1.01 | 1.06 | 1.02 |

| HADHB | Trifunctional protein, beta unit | 231086 | 2.33 | 3.43 | 1.37 | 1.60** | 1.08 | −1.15 | −1.28* |

| HSD17B4 | hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase4 |

15488 | 2.03 | 2.56 | 1.34 | 1.45** | −1.13 | 1.12 | 1.20* |

| SLC27A1 | solute carrier 27, member 1 | 26457 | 9.14 | 8.22 | −1.02 | 1.14* | −1.57 | 1.04 | 1.04 |

| SLC27A2 | solute carrier 27, member 2 |

26458 | 1.48 | 1.80 | 1.19 | 1.16** | 1.33 | 1.10 | 1.05 |

| SLC27A4 | solute carrier 27, member 4 |

26569 | 1.87 | 1.91 | 1.04 | 1.31** | −1.03 | 1.09 | 1.07 |

1From Rosen et al. (2008),

*Significantly different than control (P ≤ .03),

**Significantly different than control (P ≤ .0025)

Table 10.

Average fold change for genes related to ribosome biogenesis following a seven-day exposure to Wy-14,6431, PFOA1, or PFOS in wild-type and PPARα-null male mice.

| WT | Null | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene name | Entrez no. | Wy14,643 50 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg |

| MRPL12 | mitochondrial ribosomal protein L12 |

56282 | −1.16 | 1.25 | 1.07 | 1.14* | −1.16 | −1.18 | −1.12* |

| MRPL13 | mitochondrial ribosomal protein L13 |

68537 | 1.32 | 1.33 | 1.12 | 1.35* | 1.01 | −1.21 | −1.42** |

| MRPL17 | mitochondrial ribosomal protein L17 |

27397 | 1.68 | 1.76 | 1.10 | 1.43** | 1.13 | −1.13 | 1.09 |

| MRPL23 | mitochondrial ribosomal protein L23 |

19935 | −1.14 | −1.04 | −1.00 | 1.10 | 1.09 | −1.38 | −1.20* |

| MRPL33 | mitochondrial ribosomal protein L33 |

66845 | 1.22 | 1.26 | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.04 | −1.29 | −1.28** |

| MRPS12 | mitochondrial ribosomal protein S12 |

24030 | −1.24 | 1.18 | 1.05 | 1.12 | 1.02 | −1.27 | −1.15 |

| MRPS18A | mitochondrial ribosomal protein S18A |

68565 | −1.46 | 1.34 | 1.04 | 1.28* | 1.60 | −1.19 | −1.06 |

| RPL10 | ribosomal protein L10 |

110954 | −1.15 | −1.21 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.07 | −1.10 | −1.02 |

| RPL10A | ribosomal protein L10A |

19896 | −1.11 | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.00 | −1.07 | 1.01 |

| RPL11 | ribosomal protein L11 |

67025 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.10 | 1.11* | 1.15 | −1.15 | −1.09 |

| RPL12 | ribosomal protein L12 |

269261 | 1.01 | 1.37 | 1.08 | 1.15* | 1.11 | −1.08 | 1.05 |

| RPL13A | ribosomal protein L13a |

22121 | −1.14 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 1.12* | −1.17 | −1.15 | −1.10 |

| RPL14 | ribosomal protein L14 |

67115 | −1.28 | −1.06 | 1.15 | 1.23** | −1.13 | −1.18 | −1.22* |

| RPL17 | ribosomal protein L17 |

319195 | −1.27 | 1.15 | 1.03 | 1.12 | −1.52 | −1.10 | −1.09 |

| RPL18 | ribosomal protein L18 |

19899 | −1.11 | 1.28 | 1.04 | 1.07* | 1.19 | −1.27 | −1.09* |

| RPL18A | ribosomal protein L18a |

76808 | 1.65 | −1.37 | 1.04 | 1.11* | 1.08 | −1.15 | −1.02 |

| RPL19 | ribosomal protein L19 |

19921 | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.07 | −1.11 | −1.03 |

| RPL21 | ribosomal protein L21 |

19933 | 2.00 | 1.55 | 1.03 | 1.09 | 1.18 | −1.20 | −1.18 |

| RPL22 | ribosomal protein L22 |

19934 | 1.17 | 1.45 | 1.06 | 1.29** | 1.08 | −1.25 | −1.14* |

| RPL23 | ribosomal protein L23 |

65019 | −1.07 | 1.35 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.22 | −1.24 | −1.16 |

| RPL24 | ribosomal protein L24 |

68193 | −1.13 | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.09* | −1.00 | −1.19 | −1.11* |

| RPL26 | ribosomal protein L26 |

19941 | 1.04 | 1.22 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.07 | −1.22 | −1.18** |

| RPL27 | ribosomal protein L27 |

19942 | 1.04 | −1.01 | 1.08 | 1.38** | 1.06 | −1.25 | −1.40* |

| RPL27A | ribosomal protein L27a |

26451 | −1.07 | 1.07 | −1.00 | 1.17 | 1.26 | −1.17 | −1.09 |

| RPL28 | ribosomal protein L28 |

19943 | 1.29 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.11* | 1.67 | −1.22 | −1.10 |

| RPL29 | ribosomal protein L29 |

19944 | 1.16 | −1.30 | 1.04 | 1.09 | 1.08 | −1.23 | −1.17 |

| RPL3 | ribosomal protein L3 |

27367 | −1.00 | −1.14 | 1.01 | 1.09 | −1.01 | −1.03 | 1.06 |

| RPL30 | ribosomal protein L30 |

19946 | −1.15 | −1.07 | 1.02 | −1.21 | −1.04 | −1.29 | −1.23** |

| RPL31 | ribosomal protein L31 |

114641 | 1.11 | 1.37 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.29 | −1.18 | −1.12* |

| RPL32 | ribosomal protein L32 |

19951 | 1.06 | 1.11 | 1.02 | 1.12* | 1.08 | −1.16 | −1.03 |

| RPL34 | ribosomal protein L34 |

68436 | −1.26 | 1.16 | −1.07 | 1.05 | −1.04 | −1.22 | −1.31** |

| RPL35 | ribosomal protein L35 |

66489 | −1.03 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 1.26** | 1.04 | −1.17 | −1.11 |

| RPL36 | ribosomal protein L36 |

54217 | −1.07 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.23* | 1.07 | −1.27 | −1.20* |

| RPL37 | ribosomal protein L37 |

67281 | −1.16 | −1.18 | 1.04 | 1.27* | 1.17 | −1.19 | −1.10** |

| RPL37A | ribosomal protein L37a |

19981 | −1.15 | −1.09 | 1.03 | 1.16 | −1.12 | −1.22 | −1.19* |

| RPL38 | ribosomal protein L38 |

67671 | −1.17 | 1.14 | −1.01 | 1.06 | −1.03 | −1.18 | −1.10 |

| RPL39 | ribosomal protein L39 |

67248 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.06 | 1.13* | 1.07 | −1.18 | −1.16** |

| RPL4 | ribosomal protein L4 |

67891 | 1.16 | 1.43 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.32 | 1.03 | 1.04 |

| RPL41 | ribosomal protein L41 |

67945 | −1.06 | 1.14 | 1.05 | 1.06 | −1.13 | −1.20 | −1.26* |

| RPL5 | ribosomal protein L5 |

19983 | −1.21 | 1.02 | 1.24 | 1.09* | −1.05 | −1.05 | −1.11 |

| RPL6 | ribosomal protein L6 |

19988 | 1.01 | −1.08 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 1.15 | −1.05 | 1.03 |

| RPL7A | ribosomal protein L7a |

27176 | −1.02 | −1.11 | 1.01 | 1.01 | −1.02 | −1.07 | 1.01 |

| RPL9 | ribosomal protein L9 |

20005 | −1.35 | −1.08 | 1.03 | 1.07 | −1.11 | −1.19 | −1.12* |

| RPS10 | ribosomal protein S10 |

67097 | −1.02 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 1.00 | −1.17 | −1.12* |

| RPS11 | ribosomal protein S11 |

27207 | 1.05 | −1.74 | −1.01 | 1.11 | 1.06 | −1.24 | −1.14* |

| RPS12 | ribosomal protein S12 |

20042 | 1.16 | 1.22 | 1.11 | 1.19 | 1.22 | −1.21 | −1.12 |

| RPS13 | ribosomal protein S13 |

68052 | −1.03 | 1.10 | 1.07 | 1.22* | 1.11 | −1.27 | −1.22* |

| RPS14 | ribosomal protein S14 |

20044 | −1.03 | 1.19 | 1.05 | 1.11* | 1.01 | −1.17 | −1.11** |

| RPS15A | ribosomal protein S15a |

267019 | −1.05 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.12 | 1.02 | −1.14 | −1.20 |

| RPS16 | ribosomal protein S16 |

20055 | −1.09 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.07 | −1.02 | −1.12 | −1.07 |

| RPS17 | ribosomal protein S17 |

20068 | 1.00 | 1.16 | 1.04 | −1.19* | 1.01 | −1.19 | −1.15* |

| RPS19 | ribosomal protein S19 |

20085 | −1.07 | 1.23 | 1.08 | 1.19** | −1.00 | −1.14 | −1.05 |

| RPS2 | ribosomal protein S2 |

16898 | −1.09 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.02 | −1.16 | −1.03 | 1.04 |

| RPS20 | ribosomal protein S20 |

67427 | −1.40 | 1.21 | 1.04 | 1.15 | 1.25 | −1.11 | −1.13 |

| RPS21 | ribosomal protein S21 |

66481 | 1.11 | −1.32 | 1.15 | 1.38 | 1.39 | −1.32 | −1.25** |

| RPS23 | ribosomal protein S23 |

66475 | 1.01 | 1.04 | −1.00 | 1.04 | 1.09 | −1.21 | −1.10* |

| RPS24 | ribosomal protein S24 |

20088 | 1.58 | 1.62 | 1.11 | −1.29* | 1.75 | −1.16 | −1.19** |

| RPS25 | ribosomal protein S25 |

75617 | −1.23 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 1.13* | −1.02 | −1.30 | −1.17* |

| RPS26 | ribosomal protein S26 |

27370 | 1.32 | 1.30 | 1.04 | 1.16* | 1.14 | −1.20 | −1.08 |

| RPS27A | ribosomal protein S27a |

78294 | 1.05 | −1.05 | −1.00 | 1.02 | 1.09 | −1.08 | −1.05 |

| RPS27L | ribosomal protein S27-like |

67941 | 1.72 | 1.28 | 1.07 | 1.14* | 1.19 | −1.18 | −1.17* |

| RPS28 | ribosomal protein S28 |

54127 | −1.19 | −1.03 | 1.03 | 1.06 | −1.05 | −1.28 | −1.17* |

| RPS29 | ribosomal protein S29 |

20090 | −1.26 | −1.05 | −1.02 | 1.01 | −1.03 | −1.19 | −1.20** |

| RPS3 | ribosomal protein S3 |

27050 | −1.04 | 1.29 | 1.03 | 1.20* | −2.88 | −1.11 | −1.06 |

| RPS3A | ribosomal protein S3A |

544977 | −1.18 | −1.07 | 1.02 | −1.01 | −1.05 | −1.10 | −1.03 |

| RPS5 | ribosomal protein S5 |

20103 | −1.16 | 1.18 | 1.06 | 1.09* | −1.02 | −1.13 | −1.00 |

| RPS6 | ribosomal protein S6 |

20104 | −1.20 | −1.02 | −1.20 | 1.06 | −1.02 | −1.14 | −1.06* |

| RPS8 | ribosomal protein S8 |

20116 | 1.19 | −1.05 | 1.07 | 1.13* | 1.04 | −1.29 | −1.13 |

| RPS9 | ribosomal protein S9 |

76846 | −1.39 | 1.30 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 1.05 | −1.08 | −1.04 |

1From Rosen et al. (2008), *Significantly different than control (P ≤ .03),

**Significantly different from control (P ≤ .0025).

3.3. PCR Confirmation

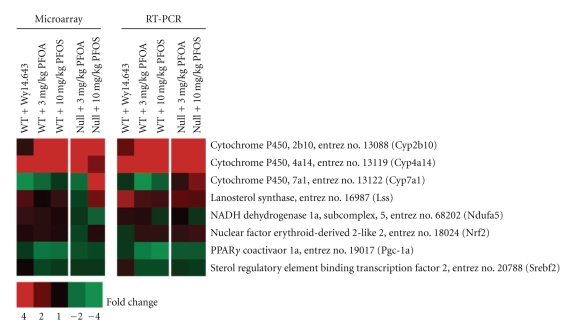

The results from real-time RT-PCR analysis of selected genes are summarized, along with the corresponding results from the microarray analysis, in Figure 4. The data from both assays were in close agreement. It should be pointed out that while up-regulation of Cyp2b10 was confirmed in treated WT and Null mice, it remained a low copy number transcript in these animals. Down-regulation of Ndufa5, a gene which encodes for a subunit of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I, could not be confirmed in treated Null mice. This result, however, was not surprising because the changes associated with oxidative phosphorylation in the current study were small and, therefore, difficult to detect given the technical variation normally associated with real-time PCR. As predicted based on the microarray results, PFOS did not appear to up-regulate the expression of Srebf2, P p a r g c1a, or Nfe2l2 (Nrf2) in either WT or Null mice.

Figure 4.

Microarray and Real-time PCR analysis of selected genes. Data from both assays were in close agreement. Small changes in Ndufa5 expression, a gene which encodes for a subunit of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I, could not be confirmed by RT-PCR. As predicted based on microarray analysis, PFOS did not appear to up-regulate the expression of Srebf2, P p a r g c1a (Pgc-1a), or Nfe2l2 (Nrf2) in WT or Null mice. Red or green correspond to average up- or down- regulation, respectively.

4. Discussion

In the current study, exposure to PFOS induced both PPARα-dependent and PPARα-independent effects in the murine liver. In WT mice, the observed changes were primarily indicative of a weak PPARα activator. As such, PFOS induced hepatomegaly and altered the expression of genes related to a number of biological functions known to be regulated by PPARα including lipid metabolism, peroxisome biogenesis, proteasome activation, and the inflammatory response [41–45]. These data are also in agreement with previous studies done in either the adult or fetal rodent [46–50]. Among those effects found to be independent of PPARα was altered expression of genes associated with xenobiotic metabolism, including up-regulation of the CAR inducible gene, Cyp2b10. Such changes, which were found in both WT and Null mice, were also consistent with results previously reported by our group for PFOA [32, 33]. Although xenobiotic metabolism can be regulated by more than one nuclear receptor [51], the ability of PFOA or perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA) to activate CAR has been demonstrated in experiments using multiple receptor-null mouse models [31]; therefore, it is likely that PFOS functions as an activator of CAR as well. Additional PPARα-unrelated effects were further indicated by regulation of a group of genes associated with lipid metabolism and inflammation in both WT and Null mice. As suggested for mice exposed to PFOA [1, 33], such changes could be due to activation of either PPARγ and/or PPARβ/δ. Indeed, studies done using transient transfection reporter cell assays indicate that PFOS and PFOA have the potential to modestly activate other PPAR isotypes. [39, 40]. Furthermore, peroxisome proliferation, a hallmark of PPARα transactivation, can also be induced in the rodent liver by activating PPARγ and/or PPARβ/δ [52]; hence, a degree of functional overlap might be expected among the PPAR isotypes. Particularly noteworthy were PPARα-independent effects that were unique to Null mice since they were not previously observed in mice treated with PFOA [1, 33]. These included modified expression of genes associated with ribosome biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and cholesterol biosynthesis. While activation of PPARα has been linked to changes in cholesterol homeostasis [19] and oxidative phosphorylation [53], it should be stressed that such changes were not simply the result of targeted disruption of PPARα because they were observed in treated animals over and above those effects which occurred in Null controls. Moreover, in the current study, genes linked to cholesterol biosynthesis were found to be up-regulated in Null mice, an effect that mirrored changes previously reported in WT mice treated with the PPARα agonist, Wy 14,643 [1].

Recognition that PPAR ligands can induce “off-target” effects is not new (for review, see [54]). It is not clear, however, whether the effects described for Null mice in the current study were the result of modified activity of transcription regulators, which only became apparent in the absence of PPARα signaling, or whether these changes represent some other aspect of murine metabolism affected by PFOS. Of interest was up-regulation of Cyp7a1. This gene encodes for an enzyme responsible for the rate limiting step in the classical pathway of hepatic bile acid biosynthesis and is important for bile acid/cholesterol homeostasis [55]. While targeted disruption of PPARα does not appear to alter basal levels of Cyp7a1 [56], PPARα agonists such as, fibrates can reduce both Cyp7a1 gene expression and bile acid biosynthesis in wild-type rodents [57] possibly by interfering with promoter binding of HNF4 [58]. Regulation of Cyp7a1 is often associated with the liver X receptor (LXR) [59] but it is tightly controlled by multiple pathways and may be positively regulated by the pregnane X receptor (PXR) [60] and the retinoid X receptor (RXR) as well [61]. While the two LXR subtypes, LXRα and LXRβ, are lipogenic and play a key role in regulating cholesterol homeostasis [62, 63], they are not thought to be positive regulators of genes in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway [64].

Additional signaling pathways that may contribute to the effects observed in Null mice include pathways regulated by Srebf2 (Srebp2) and PPARGC1α (PGC-1α). Srebf2 is one member of a group of membrane-bound transcription factors that play an important role in maintaining lipid homeostasis. SREBF2 is best known for positively regulating cholesterol synthesis in the liver and other tissues (Horton et al., 1998). While decreased nuclear abundance of SREBP2 has been linked to increased hepatic PPARα activity in rats [65], a PPARα-independent mechanism of action has been suggested in mice as well which, in combination with increased expression of CYP7a1, may paradoxically also function via decreased SREBF2 signaling [66]. It should be noted that transcript levels of Srebf2 were not affected in the current study nor was PFOS found to alter Srebf2 expression in cultured chicken hepatocytes [67], although such changes are not necessarily required for transcription factor regulation. Rather than functioning as a transcription factor like SREBP2, PPARGC-1α is a transcription coactivator that was first described as a moderator of PPARγ-induced adaptive thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue [68]. PPARGC-1α is now known to regulate various aspects of energy metabolism in different tissues by interacting with a host of transcription factors, including PPARα [69, 70]. Certain PPAR ligands have been shown to inhibit oxidative phosphorylation [71–74] and Walters et al. [75] recently reported that high doses of PFOA could modify mitochondrial function in rats via a pathway involving PPARGC-1α. Unlike their results, however, PFOS did not induce a change in expression of Ppargc-1α or its downstream target, Nrf2, in the current study. Cellular regulation of metabolism, however, is complex and there are a number of potentially interrelated signaling pathways, including HNF4α [76] and TOR [77], that based on their biological function could theoretically be linked to the effects observed in PFOS-treated Null mice. Given the diversity of effects observed in the current study, it is likely that more than one signaling pathway is responsible for the biological activity reported for PFOS.

Because certain effects were found only in Null mice, their relevance to the toxicity of PFOS is not clear. Although the developmental toxicity of PFOS has been shown to be independent of PPARα in murine neonates [34], it has also been suggested that rather than causing primary alterations to the murine transcriptome, PFOS may alter the physicochemical properties of fetal lung surfactant as the critical event related to toxicity in these animals [78–80]. It should also be stressed that in Null animals the magnitude of change found for certain effects was small, hence, the reported effects in the current study were subtle. On the other hand, these data serve to reinforce two recurring themes regarding the biological activity of PFAAs. First, as a class of compounds, the activity of PFAAs may be quite variable. Differences exist among PFAAs with regard to chain length and functional group which influence, not only the elimination half-life of assorted PFAAs [4, 7] and their ability to activate PPARα [18], but potentially their ability to modify the function of other transcription regulators as well. Second, the biological activity of PFAAs is likely to differ from that observed for fibrate pharmaceuticals, the most commonly studied ligands of PPARα. While much has been learned from studies using fibrate-exposed PPARα-null and PPARα-humanized mice regarding the relevance of chronic PPARα activation to liver tumor formation in humans [22], additional information concerning the biological activity of specific PFAAs remains relevant for risk assessment.

In summary, PFOS is a PPARα agonist that is capable of inducing a variety of PPARα-independent effects in WT and Null mice, although the toxicological relevance of these changes is uncertain. A number of these effects such as, altered expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism, inflammation, and xenobiotic metabolism were observed in both WT and Null animals, and were consistent with prior studies done with either PFOS or PFOA. Other effects involving genes associated with ribosome biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and cholesterol biosynthesis were unique to Null mice and may represent targeted signaling pathways not yet described for certain PFAAs.

Table 4.

Average fold change for genes related to proteasome biogenesis in wild-type and PPARα-null male mice following a seven-day exposure to Wy-14,6431, PFOA1, or PFOS.

| WT | Null | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene name | Entrez no. | Wy14,643 50 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg |

| PSMA1 | proteasome unit, alpha type, 1 |

26440 | 1.61 | 1.38 | 1.15 | 1.31* | 1.17 | −1.29 | −1.34 |

| PSMA2 | proteasome unit, alpha type, 2 |

19166 | −1.46 | −1.15 | 1.09 | 1.23** | −1.34 | −1.20 | −1.07 |

| PSMA3 | proteasome unit, alpha type, 3 |

19167 | 1.33 | 1.22 | 1.12 | 1.14 | 1.28 | −1.13 | −1.17 |

| PSMA4 | proteasome unit, alpha type, 4 |

26441 | 1.19 | 1.32 | 1.10 | 1.19* | 1.01 | −1.04 | 1.05 |

| PSMA5 | proteasome unit, alpha type, 5 |

26442 | 1.67 | 1.59 | 1.12 | 1.26** | 1.15 | −1.12 | 1.09 |

| PSMA6 | proteasome unit, alpha type, 6 |

26443 | 1.20 | 1.29 | 1.14 | 1.24** | 1.06 | −1.14 | −1.06 |

| PSMA7 | proteasome unit, alpha type, 7 |

26444 | 1.47 | 1.60 | 1.23 | 1.53** | 1.23 | −1.12 | 1.11 |

| PSMB1 | proteasome unit, beta type, 1 |

19170 | 1.09 | 1.29 | 1.07 | 1.28* | 1.04 | −1.17 | 1.13* |

| PSMB10 | proteasome unit, beta type, 10 |

19171 | −1.42 | −1.48 | −1.25 | −1.19 | −1.57 | −1.14 | −1.21** |

| PSMB2 | proteasome unit, beta type, 2 |

26445 | 1.33 | 1.48 | 1.05 | 1.31** | 1.02 | −1.20 | 1.05 |

| PSMB3 | proteasome unit, beta type, 3 |

26446 | 1.22 | 1.47 | 1.21 | 1.36** | 1.04 | −1.37 | −1.20 |

| PSMB4 | proteasome unit, beta type, 4 |

19172 | 1.59 | 1.65 | 1.27 | 1.55** | 1.22 | −1.12 | 1.09 |

| PSMB5 | proteasome unit, beta type, 5 |

19173 | 1.34 | 1.74 | 1.04 | 1.24** | 1.02 | −1.15 | 1.03 |

| PSMB6 | proteasome unit, beta type, 6 |

19175 | 1.54 | 1.83 | 1.08 | 1.24* | 1.19 | −1.23 | −1.09 |

| PSMB7 | proteasome unit, beta type, 7 |

19177 | 1.46 | 1.33 | 1.07 | 1.15** | 1.13 | −1.17 | −1.09 |

| PSMB8 | proteasome unit, beta type, 8 |

16913 | −1.61 | −2.00 | −1.44 | −1.51 | −1.38 | −1.23 | −1.45** |

| PSMB9 | proteasome unit, beta type, 9 |

16912 | 1.24 | −1.12 | −1.31 | −1.09 | −1.10 | −1.11 | −1.30** |

| PSMC1 | proteasome 26S unit, ATPase, 1 |

19179 | 1.44 | 1.00 | 1.19 | 1.15* | 1.11 | −1.06 | 1.01 |

| PSMC6 | proteasome 26S unit, ATPase, 6 |

67089 | 1.18 | 1.21 | 1.09 | −1.02 | 1.07 | 1.14 | −1.16 |

| PSMD1 | proteasome 26S unit, non-ATPase, 1 |

70247 | 1.20 | 1.22 | 1.15 | 1.25** | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 |

| PSMD11 | proteasome 26S unit, non-ATPase, 11 |

69077 | 1.56 | 1.38 | 1.09 | 1.26* | −1.17 | 1.16 | 1.32 |

| PSMD12 | proteasome 26S unit, non-ATPase, 12 |

66997 | 1.34 | 1.27 | 1.10 | 1.14 | 1.20 | −1.03 | 1.04 |

| PSMD13 | proteasome 26S unit, non-ATPase, 13 |

23997 | 1.21 | 1.38 | 1.14 | 1.26* | −1.03 | −1.38 | −1.42** |

| PSMD14 | proteasome 26S unit, non-ATPase, 14 |

59029 | −1.39 | −1.42 | 1.17 | 1.31* | 1.31 | 1.01 | 1.17 |

| PSMD2 | proteasome 26S unit, non-ATPase, 2 |

21762 | 1.34 | 1.32 | 1.14 | 1.24* | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.30** |

| PSMD3 | proteasome 26S unit, non-ATPase, 3 |

22123 | −1.35 | −1.19 | 1.17 | 1.29* | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.22* |

| PSMD4 | proteasome 26S unit, non-ATPase, 4 |

19185 | 1.31 | 1.92 | 1.19 | 1.38** | 1.03 | −1.07 | 1.17* |

| PSMD6 | proteasome 26S unit, non-ATPase, 6 |

66413 | 1.17 | 1.33 | 1.10 | 1.14* | 1.07 | −1.06 | 1.04 |

| PSMD7 | proteasome 26S unit, non-ATPase, 7 |

17463 | 1.13 | 1.27 | 1.13 | 1.24* | 1.02 | −1.19 | −1.22* |

| PSMD8 | proteasome 26S unit, non-ATPase, 8 |

57296 | 1.68 | 1.24 | 1.03 | 1.30** | 1.16 | −1.15 | −1.00 |

| PSME1 | proteasome activator unit 1 |

19186 | 1.22 | −1.00 | −1.05 | 1.32** | 1.27 | −1.10 | −1.09 |

| VCP | valosin−containing protein |

269523 | 1.40 | 1.49 | 1.04 | 1.12 | 1.07 | 1.13 | 1.21** |

1From Rosen et al. (2008),

*Significantly different than control (P ≤ .03),

**Significantly different than control (P ≤ .0025).

Table 5.

Average fold change for genes related to peroxisome biogenesis in wild-type and PPARα-null male mice following a seven-day exposure to Wy-14,6431, PFOA1, or PFOS.

| WT | Null | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene name | Entrez no. | Wy14,643 50 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg |

| PECI | peroxisome D3, D2-enoyl- CoA isomerase |

23986 | 1.73 | 3.15 | 1.61 | 1.87** | 1.96 | 1.42 | 1.57** |

| PEX1 | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 1 |

71382 | 1.25 | 1.84 | 1.07 | 1.21** | −1.02 | 1.10 | 1.14* |

| PEX11A | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 11 alpha |

18631 | 1.80 | 6.71 | 1.70 | 2.99** | 1.04 | −1.09 | −1.11 |

| PEX12 | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 12 |

103737 | 1.07 | 1.36 | 1.11 | 1.17* | 1.09 | 1.17 | 1.30* |

| PEX13 | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 13 |

72129 | 1.04 | 1.58 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 1.02 | 1.09 | 1.16* |

| PEX14 | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 14 |

56273 | 1.06 | 1.24 | 1.03 | 1.25* | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.13 |

| PEX16 | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 16 |

18633 | 1.51 | 1.44 | 1.13 | 1.33** | −1.00 | −1.12 | −1.03 |

| PEX19 | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 19 |

19298 | 1.61 | 2.25 | 1.19 | 1.36** | 1.12 | 1.15 | 1.32** |

| PEX26 | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 26 |

74043 | −1.32 | −1.86 | 1.01 | 1.26 | 1.01 | 1.29 | 1.10 |

| PEX3 | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 3 |

56535 | 1.50 | 1.77 | 1.13 | 1.37** | −1.05 | 1.09 | 1.20* |

| PEX6 | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 6 |

224824 | 1.08 | −1.06 | 1.12 | 1.16 | 1.30 | −1.08 | 1.09 |

| PXMP2 | peroxisomal membrane protein 2 |

19301 | −1.22 | −1.29 | −1.08 | −1.20* | −1.28 | −1.13 | −1.06 |

| PXMP4 | peroxisomal membrane protein 4 |

59038 | 1.62 | 2.09 | 1.61 | 1.62* | 1.99 | −1.03 | 1.01 |

1From Rosen et al. [1],

*Significantly different than control (P ≤ .03),

**Significantly different than control (P ≤ .0025).

Table 6.

Average fold change for genes related to the inflammatory response in wild-type and PPARα-null male mice following a seven-day exposure to Wy-14,6431, PFOA1, or PFOS.

| WT | Null | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene name | Entrez no. | Wy14,643 50 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg |

| APCS | amyloid P component, serum |

20219 | −1.50 | −2.33 | −1.23 | −1.28 | −1.19 | 1.41 | 1.13 |

| C1QA | complement component 1QA |

12259 | −1.75 | −1.40 | −1.13 | −1.17 | −1.31 | −1.24 | −1.34** |

| C1R | complement component 1r | 50909 | −2.67 | −1.78 | −1.15 | −1.23* | −1.22 | 1.16 | −1.17* |

| C1S | complement component 1s | 317677 | −3.73 | −2.53 | −1.14 | −1.62** | −1.52 | 1.06 | −1.11 |

| C2 | complement component 2 | 12263 | −2.56 | −1.91 | −1.37 | −1.32* | −1.18 | 1.10 | 1.11 |

| C3 | complement component 3 | 12266 | −1.41 | −1.41 | −1.04 | −1.04 | −1.22 | 1.13 | 1.08* |

| C4B | complement component 4B | 12268 | −2.35 | −2.15 | −1.08 | −1.28 | −1.91 | 1.15 | −1.13 |

| C4BP | complement component 4 binding prot |

12269 | −1.86 | −1.82 | −1.11 | −1.19 | 1.02 | 1.39 | 1.13 |

| C6 | complement component 6 | 12274 | −2.66 | −1.27 | −1.35 | −1.08 | 1.90 | 1.12 | 1.06 |

| C8A | complement component 8, alpha |

230558 | −3.62 | −1.94 | −1.17 | −1.31* | −1.17 | 1.19 | 1.04 |

| C8B | complement component 8, beta |

110382 | −5.25 | −2.99 | −1.20 | −1.60** | −1.12 | 1.11 | 1.02 |

| C8G | complement component 8, gamma |

69379 | −1.59 | −1.35 | −1.05 | −1.17* | −1.34 | −1.10 | −1.17** |

| C9 | complement component 9 |

12279 | −2.12 | −2.64 | −1.35 | −1.58** | −1.46 | 1.08 | −1.19* |

| CFB | complement factor B |

14962 | −1.81 | −1.77 | −1.07 | −1.26 | −1.39 | 1.07 | −1.11 |

| CFH | complement factor H |

12628 | −2.39 | −2.30 | −1.19 | −1.62 | −1.76 | 1.45 | −1.35 |

| CFI | complement factor I |

12630 | −1.63 | −1.77 | −1.06 | −1.15 | −1.06 | 1.12 | 1.04 |

| CRP | C−reactive protein |

12944 | −1.33 | −1.39 | −1.01 | −1.15* | 1.32 | 1.14 | 1.13 |

| CTSC | cathepsin C | 13032 | −1.56 | −2.52 | 1.01 | −1.36 | −1.96 | 1.04 | −1.35 |

| F10 | coagulation factor X |

14058 | −1.62 | −1.42 | −1.09 | −1.13 | −1.00 | 1.07 | −1.07 |

| F11 | coagulation factor XI |

109821 | −2.17 | −2.68 | −1.41 | −2.08** | −1.08 | −1.08 | −1.34* |

| F12 | coagulation factor XII |

58992 | −1.22 | −1.35 | −1.05 | −1.14 | −1.21 | −1.07 | −1.12* |

| F13B | coagulation factor XIII, B polypeptide |

14060 | −1.41 | −1.54 | −1.11 | −1.22** | 1.02 | 1.02 | −1.12 |

| F2 | coagulation factor II (thrombin) |

14061 | −1.19 | −1.20 | −1.02 | −1.13* | −1.10 | 1.02 | −1.02 |

| F5 | coagulation factor V |

14067 | −1.78 | −1.53 | −1.09 | −1.44* | −1.41 | 1.08 | −1.34* |

| F7 | coagulation factor VII |

14068 | −2.68 | −2.15 | −1.09 | −1.46** | −1.23 | 1.03 | −1.03 |

| F9 | coagulation factor IX |

14071 | −1.42 | −1.43 | −1.02 | −1.39* | −1.33 | 1.07 | −1.19 |

| FGA | fibrinogen alpha chain |

14161 | −1.27 | −1.75 | 1.00 | −1.12 | −1.07 | 1.05 | −1.07 |

| FGB | fibrinogen beta chain |

110135 | −1.32 | −1.97 | 1.03 | −1.15 | −1.25 | 1.08 | −1.07 |

| FGG | fibrinogen gamma chain |

99571 | −1.14 | −1.68 | 1.02 | −1.15* | −1.08 | 1.04 | −1.06 |

| KLKB1 | kallikrein B, plasma (Fletcher factor) 1 |

16621 | −1.58 | −1.76 | −1.09 | −1.39* | −1.05 | −1.03 | −1.18* |

| LUM | lumican | 17022 | −1.34 | −1.27 | 1.02 | −1.20* | −1.66 | 1.03 | −1.27 |

| MASP1 | Mannan- binding lectin1 |

17174 | −1.23 | −1.62 | −1.19 | −1.18* | 1.11 | 1.18 | 1.17* |

| MBL2 | Mannose-binding lectin 2 |

17195 | −1.77 | −2.18 | −1.12 | −1.23* | −1.36 | −1.20 | −1.28** |

| ORM2 | orosomucoid 2 | 18405 | −1.96 | −2.04 | −1.26 | −1.21 | −1.16 | 1.30 | 1.05 |

| PROC | protein C | 19123 | −1.49 | −1.50 | −1.02 | −1.13* | −1.09 | −1.01 | −1.09* |

| SAA1 | serum amyloid A1 |

20209 | −3.71 | −3.98 | −2.75 | 1.04 | −2.76 | 6.51 | 2.55 |

| SAA2 | serum amyloid A2 |

20210 | −1.75 | −1.30 | −1.79 | −1.29 | 3.05 | 1.44 | 1.22 |

| SAA4 | serum amyloid A4, constitutive |

20211 | −2.19 | −1.45 | −1.06 | −1.27 | −1.02 | 1.47 | −1.05 |

| SERPINA1 | serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A1 |

20701 | −3.43 | −2.07 | −1.03 | −1.05** | −1.16 | 1.11 | −1.33 |

| SERPINC1 | serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade C1 |

11905 | −1.19 | −1.21 | −1.03 | −1.08* | −1.02 | −1.04 | −1.06* |

| SERPIND1 | serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade D1 |

15160 | −1.62 | −1.70 | −1.08 | −1.25** | −1.05 | 1.09 | 1.05 |

| SERPINE1 | serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E1 |

18787 | 1.44 | 9.75 | 1.03 | 1.85** | 2.95 | 1.03 | 1.26* |

| SERPINF2 | serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade F2 |

18816 | −1.15 | −1.87 | 1.01 | −1.13* | 1.02 | 1.12 | 1.05 |

| SERPING1 | serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade G1 |

12258 | −1.23 | −1.37 | −1.12 | −1.13 | −1.07 | 1.12 | 1.02 |

| VWF | von Willebrand factor |

22371 | 1.06 | 1.12 | −1.25 | 1.07 | −1.51 | 1.22 | 1.14 |

1From Rosen et al. [1],

*Significantly different than control (P ≤ .03),

**Significantly different than control (P ≤ .0025).

Table 7.

Average fold change for genes related to xenobiotic metabolism in wild-type and PPARα-null male mice following a seven-day exposure to Wy-14,6431, PFOA1, or PFOS.

| WT | Null | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene name | Entrez no. | Wy14,643 50 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg |

| ADH1C | alcohol dehydrogenase 1C | 11522 | 1.27 | 1.02 | −1.00 | 1.02 | −1.09 | −1.02 | −1.04 |

| ADH5 | alcohol dehydrogenase 5 | 11532 | −1.18 | 1.10 | 1.09 | −1.04 | −1.02 | 1.11 | 1.14 |

| ADH7 | alcohol dehydrogenase 7 | 11529 | −1.51 | 1.06 | −1.01 | −1.06 | −1.71 | −1.01 | −1.01 |

| ALDH1L1 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 1L1 | 107747 | −1.29 | −1.85 | −1.08 | −1.18* | −1.41 | 1.76 | 1.68** |

| ALDH3B1 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 3B1 |

67689 | 1.12 | 1.04 | −1.11 | 1.04 | 1.48 | −1.03 | −1.11 |

| CES1 | carboxylesterase 1 | 12623 | 1.43 | 2.29 | 1.61 | 2.62** | 3.15 | 4.80 | 4.84** |

| CES2 | carboxylesterase 2 | 234671 | 3.37 | 5.75 | 1.03 | 2.29 | 4.25 | 1.41 | 1.74* |

| CYP1A1 | cytochrome P450,1A1 |

13076 | 1.25 | −1.93 | −1.05 | 1.08 | −1.02 | 1.34 | 1.49** |

| CYP1A2 | cytochrome P450,1A2 |

13077 | −1.67 | −1.24 | −1.13 | 1.10 | 1.26 | 1.15 | 1.25* |

| CYP2A4 | cytochrome P450,2A4 |

13087 | −4.26 | 1.33 | 1.08 | 2.01 | 5.82 | 1.28 | 1.57** |

| CYP2B10 | cytochrome P450,2B10 |

13088 | 1.31 | 4.39 | 3.50 | 5.92* | 24.20 | 11.34 | 21.66** |

| CYP2C55 | cytochrome P450,2C55 |

72082 | 1.58 | 21.72 | 1.54 | 8.37* | 110.35 | 10.57 | 25.18** |

| CYP2C37 | cytochrome P450,2C37 |

13096 | −2.42 | 1.57 | 1.39 | 1.48 | 4.09 | 1.53 | 1.68 |

| CYP2C38 | cytochrome P450, 2C38 |

13097 | 1.62 | 1.12 | 1.78 | 2.30** | −1.42 | −1.26 | 1.03 |

| CYP2C39 | cytochrome P450, 2C39 |

13098 | 2.45 | 1.51 | 1.65 | 1.51 | −1.42 | 1.11 | −1.01 |

| CYP2C50 | cytochrome P450,2C50 |

107141 | −2.63 | 1.31 | 1.11 | 1.19 | 1.71 | 1.34 | 1.26 |

| CYP2C54 | cytochrome P450,2C54 |

404195 | −2.98 | 1.44 | 1.16 | 1.14 | 1.87 | 1.29 | 1.35** |

| CYP2C70 | cytochrome P450,2C70 |

226105 | −2.75 | −4.22 | −1.23 | −1.68* | −1.05 | −1.05 | 1.04 |

| CYP2C65 | cytochrome P450,2C65 |

72303 | 1.44 | 1.63 | −1.93 | 1.98 | 46.78 | 2.28 | 8.63** |

| CYP2D10 | cytochrome P450,2D10 |

13101 | −1.47 | −1.09 | −1.02 | −1.03 | 1.33 | −1.00 | 1.02 |

| CYP2D26 | cytochrome P450,2D26 |

76279 | −1.17 | −1.21 | 1.06 | −1.01 | −1.12 | −1.03 | −1.08 |

| CYP3A11 | cytochrome P450,3A11 |

13112 | −1.23 | 1.40 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 4.61 | 1.12 | 1.20 |

| CYP3A41A | cytochrome P450,3A41A |

53973 | −2.08 | 1.11 | 1.24 | 1.58* | 2.01 | 1.39 | 1.25 |

| CYP3A25 | cytochrome P450,3A25 |

56388 | −1.94 | −1.70 | 1.01 | −1.01 | 1.04 | 1.13 | 1.12 |

| CYP3A13 | cytochrome P450,3A13 |

13113 | −1.54 | 1.19 | 1.22 | 1.38* | 1.52 | 1.75 | 1.62** |

| EPHX1 | epoxide hydrolase 1, microsomal |

13849 | 1.22 | 1.78 | 1.16 | 1.60* | 1.82 | 1.33 | 1.59* |

| EPHX2 | epoxide hydrolase 2, cytoplasmic |

13850 | 2.25 | 2.34 | 1.45 | 1.67** | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.07 |

| GSTA3 | glutathione S-transferase A3 |

14859 | 1.08 | −1.04 | 1.05 | 1.26 | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.13 |

| GSTA4 | glutathione S-transferase A4 |

14860 | −2.01 | −1.10 | −1.02 | 1.52 | 1.37 | −1.20 | 1.36 |

| GSTA5 | glutathione S-transferase A5 |

14857 | −1.12 | 1.44 | 1.19 | 2.76* | 2.26 | 1.15 | 2.13 |

| GSTK1 | glutathione S-transferase kappa 1 |

76263 | 1.85 | 1.43 | 1.02 | −1.04 | −1.30 | −1.26 | −1.27 |

| GSTM1 | glutathione S-transferase M1 |

14863 | −2.12 | −1.56 | −1.51 | 1.77 | 2.54 | 1.18 | 1.97 |

| GSTM3 | glutathione S-transferase, mu 3 |

14864 | −1.32 | 1.50 | 1.16 | 2.44* | 1.83 | 1.57 | 2.59* |

| GSTM4 | glutathione S-transferase M4 |

14865 | 2.07 | 3.13 | 1.30 | 2.40* | 2.48 | 1.40 | 2.63* |

| GSTP1 | glutathione S-transferase pi 1 |

14870 | −2.79 | 4.14 | −1.16 | 1.00 | 2.87 | −1.06 | −1.03 |

| GSTT2 | glutathione S-transferase theta 2 |

14872 | 1.64 | 2.74 | 1.42 | 1.83** | 1.13 | 1.16 | 1.43** |

| GSTT3 | glutathione S-transferase, theta 3 |

103140 | 2.10 | 1.13 | 1.41 | 1.61 | 1.77 | 1.30 | 1.85** |

| GSTZ1 | glutathione transferase zeta 1 |

14874 | −1.36 | −1.14 | −1.03 | −1.08 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.01 |

| MGST1 | microsomal glutathione S-transferase 1 |

56615 | 1.28 | 1.24 | −1.02 | 1.01 | 1.21 | 1.04 | 1.01 |

| MGST3 | microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 |

66447 | 1.73 | 1.60 | 1.24 | 1.80* | −1.54 | −1.31 | −1.06 |

| POR | P450 (cytochrome) oxidoreductase |

18984 | −1.26 | 2.63 | 1.27 | 1.94 | 2.04 | 2.91 | 3.30** |

| UGT2B17 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 2B17 |

71773 | −3.90 | −1.13 | −1.03 | 1.02 | 1.24 | 1.03 | −1.01 |

| UGT2B4 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 2B4 |

552899 | −1.37 | −1.93 | −1.26 | −1.23* | 1.35 | 1.01 | 1.03 |

| UGT2B7 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 |

231396 | −1.19 | −1.20 | −1.05 | −1.05 | 1.16 | 1.04 | −1.00 |

1From Rosen et al. (2008),

*Significantly different than control (P ≤ .03),

**Significantly different than control (P ≤ .0025).

Table 8.

Average fold change for genes related to cholesterol biosynthesis in wild-type and PPARα-null male mice following a seven-day exposure to Wy-14,6431, PFOA1, or PFOS.

| WT | Null | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene name | Entrez no. | Wy14,643 50 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg |

| CYP51 | cytochrome P450, family 51 |

13121 | 2.85 | 1.37 | 1.27 | 2.10* | 1.37 | 2.99 | 1.93** |

| FDFT1 | farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1 |

14137 | 2.30 | 1.28 | 1.29 | 1.73* | 1.09 | 2.00 | 1.92** |

| FDPS | farnesyl diphosphate synthase |

110196 | 3.19 | 1.79 | 1.16 | 1.38 | 1.83 | 1.84 | 1.96** |

| HMGCR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl -CoA reductase |

15357 | 1.79 | −1.08 | 1.19 | 1.97** | 1.20 | 1.85 | 1.80* |

| HMGCS1 | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl -CoA synthase 1 |

208715 | 6.67 | 1.79 | 1.15 | 1.61 | −1.06 | 3.11 | 1.86* |

| HMGCS2 | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl -CoA synthase 2 |

15360 | 1.17 | 1.54 | 1.28 | 1.34* | 1.25 | −1.08 | −1.28* |

| IDI1 | isopentenyl-diphosphate delta isomerase 1 |

319554 | 3.14 | 1.61 | 1.35 | 1.62 | 1.40 | 1.96 | 1.57* |

| LSS | lanosterol synthase | 16987 | 1.73 | 1.08 | 1.12 | 1.41 | −1.26 | 1.98 | 2.13** |

| MVK | mevalonate kinase | 17855 | 1.45 | −1.24 | 1.12 | 1.22 | −1.02 | 1.57 | 1.52** |

| PMVK | phosphomevalonate kinase | 68603 | 3.23 | 2.04 | 1.36 | 1.51* | 1.20 | 1.58 | 1.53** |

| SQLE | squalene epoxidase | 20775 | 3.10 | 1.05 | 1.17 | 1.46 | 1.26 | 2.25 | 1.98** |

1From Rosen et al. (2008), *Significantly different than control (P ≤ .03),

**Significantly different than control (P ≤ .0025).

Table 9.

Average fold change for genes related to oxidative phosphorylation/electron transport in wild-type and PPARα-null male mice following a seven-day exposure to Wy-14,6431, PFOA1, or PFOS.

| WT | Null | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene name | Entrez no. | Wy14,643 50 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg | PFOA 3 mg/kg | PFOS 3 mg/kg | PFOS 10 mg/kg |

| ATP5D | ATP synthase H+ transporting, F1delta |

66043 | 1.03 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.09 | −1.17 | −1.22 | −1.13* |

| ATP5E | ATP synthase H+ transporting, F1epsilon |

67126 | −1.10 | 1.21 | −1.00 | 1.03 | −1.17 | −1.32 | −1.38** |

| ATP5G2 | ATP synthase H+ transporting, F0, C2 |

67942 | −1.09 | −1.03 | 1.10 | −1.10 | −1.10 | −1.33 | −1.26** |

| ATP5G3 | ATP synthase H+ transporting, F0, C3 |

228033 | 1.62 | 1.48 | −1.01 | 1.05 | −1.10 | −1.12 | −1.10** |

| ATP5H | ATP synthase H+ transporting, F0, D |

71679 | 1.18 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 1.06 | −1.01 | −1.30 | −1.38** |

| ATP5I | ATP synthase H+ transporting, F0, E |

11958 | −1.01 | −1.45 | −1.03 | 1.10 | 1.17 | −1.38 | −1.50** |

| ATP5J | ATP synthase H+ transporting, F0, F6 |

11957 | −1.20 | 1.44 | −1.04 | −1.07 | −1.14 | −1.25 | −1.35** |

| ATP5J2 | ATP synthase H+ transporting,F0, F2 |

57423 | 2.38 | −1.56 | −1.05 | −1.09 | 1.03 | −1.29 | −1.35** |

| ATP5L | ATP synthase H+ transporting, F0, G |

27425 | 1.58 | 1.21 | −1.02 | 1.00 | −1.05 | −1.33 | −1.30** |

| ATP5O | ATP synthase H+ transporting, F1, O |

28080 | 1.12 | 1.16 | 1.06 | 1.22 | −1.03 | −1.33 | −1.31** |

| ATP6V0B | ATPase, H+ transporting, V0 unit b |

114143 | −1.37 | −1.25 | 1.03 | −1.09 | 1.05 | −1.22 | −1.20** |

| ATP6V1F | ATPase, H+ transporting, V1 unit F |

66144 | −1.18 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 1.01 | −1.33 | −1.28** |

| COX4I1 | cytochrome c oxidase unit IV isoform 1 |

12857 | 1.14 | 1.15 | 1.02 | 1.03 | −1.15 | −1.19 | −1.16** |

| COX5A | cytochrome c oxidase unit Va |

12858 | 1.25 | 1.12 | −1.02 | 1.09 | −1.13 | −1.26 | −1.33** |

| COX5B | cytochrome c oxidase unit Vb |

12859 | 1.19 | 1.33 | 1.09 | 1.08 | −1.27 | −1.27 | −1.35** |

| COX6B1 | cytochrome c oxidase unit VIb1 |

110323 | 1.32 | 1.39 | −1.01 | 1.10* | −1.12 | −1.25 | −1.19* |

| COX6C | cytochrome c oxidase unit VIc |

12864 | 1.62 | −1.23 | 1.03 | −1.05 | 1.21 | −1.22 | −1.25** |

| COX7A2 | cytochrome c oxidase unit VIIa 2 |

12866 | −1.68 | −1.08 | −1.04 | −1.04 | −1.57 | −1.39 | −1.37** |

| COX7C | cytochrome c oxidase unit VIIc |

12867 | 1.22 | 1.32 | −1.03 | −1.28* | −1.05 | −1.23 | −1.19** |

| COX8A | cytochrome c oxidase unit 8A |

12868 | 1.34 | 1.34 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.07 | −1.23 | −1.13* |

| NDUFA1 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha1 |

54405 | −1.19 | 1.13 | −1.03 | −1.11 | −1.25 | −1.31 | −1.49** |

| NDUFA2 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha 2 |

17991 | 1.06 | 1.18 | 1.04 | 1.04 | −1.06 | −1.26 | −1.33** |

| NDUFA3 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha 3 |

66091 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 1.06 | 1.16* | −1.06 | −1.37 | −1.30** |

| NDUFA4 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha 4 |

17992 | 1.02 | 2.46 | −1.00 | 1.01 | 3.16 | −1.12 | −1.11** |

| NDUFA5 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha 5 |

68202 | 1.41 | 1.26 | 1.10 | 1.11 | −1.07 | −1.55 | −1.73** |

| NDUFA6 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha 6 |

67130 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.02 | −1.04 | −1.02 | −1.34 | −1.29** |

| NDUFA7 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha 7 |

66416 | −1.14 | −1.01 | 1.09 | 1.12 | −1.17 | −1.45 | −1.38** |

| NDUFA8 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha 8 |

68375 | 1.14 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 1.09 | 1.05 | −1.29 | −1.18* |

| NDUFA12 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha12 |

66414 | 1.47 | 1.16 | −1.03 | 1.06 | 1.06 | −1.51 | −1.40** |

| NDUFA13 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha13 |

67184 | −1.12 | −1.16 | −1.03 | −1.03 | −1.08 | −1.26 | −1.28** |

| NDUFA9 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha 9 |

66108 | 1.18 | 1.07 | 1.02 | −1.01 | −1.09 | −1.20 | −1.19** |

| NDUFAB1 | NADH dehydrogenase 1, alpha/beta 1 |

70316 | 1.56 | 1.19 | 1.05 | 1.23* | −1.07 | −1.31 | −1.44* |

| NDUFB2 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 beta 2 |

68198 | −2.31 | −3.32 | 1.04 | 1.11 | 1.49 | −1.31 | −1.35** |

| NDUFB3 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 beta 3 |

66495 | 1.55 | 1.93 | 1.09 | 1.19 | 1.05 | −1.41 | −1.32** |

| NDUFB4 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 beta 4 |

68194 | −1.03 | 1.17 | −1.01 | 1.06 | −1.13 | −1.45 | −1.46** |

| NDUFB5 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 beta 5 |

66046 | 1.21 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 1.05 | −1.28 | −1.41** |

| NDUFB6 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 beta 6, |

230075 | 1.32 | −1.03 | 1.04 | 1.19 | −1.02 | −1.38 | −1.36** |

| NDUFB7 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 beta 7, |

66916 | 1.02 | 1.14 | 1.04 | 1.11 | −1.11 | −1.40 | −1.29** |

| NDUFB9 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 beta 9, |

66218 | 1.19 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.01 | −1.08 | −1.22 | −1.25** |

| NDUFB11 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 beta 11 |

104130 | −1.29 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.06 | −1.00 | −1.26 | −1.23** |

| NDUFC1 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 unknown 1 |

66377 | −1.28 | 1.84 | 1.07 | 1.21* | 1.17 | −1.28 | −1.37** |

| NDUFC2 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 unknown, 2 |

68197 | −1.02 | 1.13 | 1.06 | 1.06 | −1.13 | −1.37 | −1.33** |

| NDUFS4 | NADH dehydrogenase Fe-S protein 4 |

17993 | 1.51 | 1.21 | 1.12 | −1.12 | 1.07 | −1.41 | −1.40** |

| NDUFS5 | NADH dehydrogenase Fe-S protein 5 |

595136 | 1.16 | 1.13 | −1.01 | 1.08 | 1.02 | −1.37 | −1.44** |

| NDUFS7 | NADH dehydrogenase Fe-S protein 7 |

75406 | 1.09 | 1.40 | 1.09 | 1.13* | 1.07 | −1.28 | −1.15 |

| NDUFS6 | NADH dehydrogenase Fe-S protein 6 |

407785 | −1.32 | 1.06 | −1.01 | 1.02 | −1.14 | −1.30 | −1.32** |

| NDUFV2 | NADH dehydrogenase flavoprotein 2 |

72900 | 1.38 | 1.09 | 1.06 | 1.07 | −1.02 | −1.24 | −1.24** |

| NDUFV3 | NADH dehydrogenase flavoprotein 3, |

78330 | 1.12 | 1.16 | −1.03 | −1.01 | −1.14 | −1.35 | −1.39** |

| UCRC | ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase |

66152 | 1.58 | 1.26 | 1.10 | 1.27 | 1.07 | −1.40 | −1.27** |

| UHRF1BP1 | UHRF1 binding protein 1 |

224648 | −1.03 | 1.36 | −1.08 | 1.06 | 1.15 | 1.23 | 1.15** |

| UQCR | ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase |

66594 | 1.26 | 1.40 | 1.04 | 1.14* | 1.09 | −1.28 | −1.19* |

| UQCRC2 | ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase CP II |

67003 | 1.09 | 1.17 | 1.07 | 1.13 | −1.04 | −1.11 | −1.27* |

| UQCRQ | ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase 3 unit 7 |

22272 | 1.01 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.12* | −1.07 | −1.18 | −1.21** |

1From Rosen et al. [1], *Significantly different than control (P ≤ .03),**Significantly different than control (P ≤ .0025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Hongzu Ren for conducting the microarray analysis and Drs. Jennifer Seed and Neil Chernoff for their critical review of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Rosen MB, Abbott BD, Wolf DC, et al. Gene profiling in the livers of wild-type and PPARα-null mice exposed to perfluorooctanoic acid. Toxicologic Pathology. 2008;36(4):592–607. doi: 10.1177/0192623308318208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giesy JP, Kannan K. Global distribution of perfluorooctane sulfonate in wildlife. Environmental Science and Technology. 2001;35(7):1339–1342. doi: 10.1021/es001834k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houde M, Martin JW, Letcher RJ, Solomon KR, Muir DCG. Biological monitoring of polyfluoroalkyl substances: a review. Environmental Science and Technology. 2006;40(11):3463–3473. doi: 10.1021/es052580b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau C, Anitole K, Hodes C, Lai D, Pfahles-Hutchens A, Seed J. Perfluoroalkyl acids: a review of monitoring and toxicological findings. Toxicological Sciences. 2007;99(2):366–394. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calafat AM, Wong LY, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Needham LL. Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-2004 and comparisons with NHANES 1999-2000. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007;115(11):1596–1602. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen GW, Mair DC, Reagen WK, et al. Preliminary evidence of a decline in perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) concentrations in American Red Cross blood donors. Chemosphere. 2007;68(1):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen GW, Burris JM, Ehresman DJ, et al. Half-life of serum elimination of perfluorooctanesulfonate, perfluorohexanesulfonate, and perfluorooctanoate in retired fluorochemical production workers. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007;115(9):1298–1305. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thibodeaux JR, Hanson RG, Rogers JM, et al. Exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonate during pregnancy in rat and mouse. I: maternal and prenatal evaluations. Toxicological Sciences. 2003;74(2):369–381. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apelberg BJ, Witter FR, Herbstman JB, et al. Cord serum concentrations of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) in relation to weight and size at birth. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007;115(11):1670–1676. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fei C, McLaughlin JK, Lipworth L, Olsen J. Maternal levels of perfluorinated chemicals and subfecundity. Human Reproduction. 2009;24(5):1200–1205. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fei C, McLaughlin JK, Tarone RE, Olsen J. Perfluorinated chemicals and fetal growth: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007;115(11):1677–1682. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fei C, McLaughlin JK, Tarone RE, Olsen J. Fetal growth indicators and perfluorinated chemicals: a study in the Danish National Birth Cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;168(1):66–72. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Washino N, Saijo Y, Sasaki S, et al. Correlations between prenatal exposure to perfluorinated chemicals and reduced fetal growth. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2009;117(4):660–667. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen GW, Butenhoff JL, Zobel LR. Perfluoroalkyl chemicals and human fetal development: an epidemiologic review with clinical and toxicological perspectives. Reproductive Toxicology. 2009;27(3-4):212–230. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nolan LA, Nolan JM, Shofer FS, Rodway NV, Emmett EA. The relationship between birth weight, gestational age and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)-contaminated public drinking water. Reproductive Toxicology. 2009;27(3-4):231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cwinn MA, Jones SP, Kennedy SW. Exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonate or fenofibrate causes PPAR-α dependent transcriptional responses in chicken embryo hepatocytes. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology—C. 2008;148(2):165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shipley JM, Hurst CH, Tanaka SS, et al. Trans-activation of PPARα and induction of PPARα target genes by perfluorooctane-based chemicals. Toxicological Sciences. 2004;80(1):151–160. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf CJ, Takacs ML, Schmid JE, Lau C, Abbott BD. Activation of mouse and human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha by perfluoroalkyl acids of different functional groups and chain lengths. Toxicological Sciences. 2008;106(1):162–171. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters JM, Cattley RC, Gonzalez FJ. Role of PPARα in the mechanism of action of the nongenotoxic carcinogen and peroxisome proliferator Wy-14,643. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18(11):2029–2033. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.11.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjork JA, Wallace KB. Structure-activity relationships and human relevance for perfluoroalkyl acid-induced transcriptional activation of peroxisome proliferation in liver cell cultures. Toxicological Sciences. 2009;111(1):89–99. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foreman JE, Chang S-C, Ehresman DJ, et al. Differential hepatic effects of perfluorobutyrate mediated by mouse and human PPAR-α . Toxicological Sciences. 2009;110(1):204–211. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez FJ, Shah YM. PPARα: mechanism of species differences and hepatocarcinogenesis of peroxisome proliferators. Toxicology. 2008;246(1):2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klaunig JE, Babich MA, Baetcke KP, et al. PPARα agonist-induced rodent tumors: modes of action and human relevance. Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 2003;33(6):655–780. doi: 10.1080/713608372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morimura K, Cheung C, Ward JM, Reddy JK, Gonzalez FJ. Differential susceptibility of mice humanized for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α to Wy-14,643-induced liver tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(5):1074–1080. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Q, Ito S, Gonzalez FJ. Hepatocyte-restricted constitutive activation of PPARα induces hepatoproliferation but not hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(6):1171–1177. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyton KZ, Chiu WA, Bateson TF, et al. A reexamination of the PPAR-α activation mode of action as a basis for assessing human cancer risks of environmental contaminants. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2009;117(11):1664–1672. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abbott BD, Wolf CJ, Schmid JE, et al. Perfluorooctanoic acid-induced developmental toxicity in the mouse is dependent on expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha. Toxicological Sciences. 2007;98(2):571–581. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudo N, Kawashima Y. Fish oil-feeding prevents perfluorooctanoic acid-induced fatty liver in mice. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1997;145(2):285–293. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf DC, Moore T, Abbott BD, et al. Comparative hepatic effects of perfluorooctanoic acid and WY 14,643 in PPAR-α knockout and wild-type mice. Toxicologic Pathology. 2008;36(4):632–639. doi: 10.1177/0192623308318216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Q, Abedi-Valugerdi M, Xie Y, et al. Potent suppression of the adaptive immune response in mice upon dietary exposure to the potent peroxisome proliferator, perfluorooctanoic acid. International Immunopharmacology. 2002;2(2-3):389–397. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng X, Klaassen CD. Perfluorocarboxylic acids induce cytochrome P450 enzymes in mouse liver through activation of PPAR-α and CAR transcription factors. Toxicological Sciences. 2008;106(1):29–36. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren H, Vallanat B, Nelson DM, et al. Evidence for the involvement of xenobiotic-responsive nuclear receptors in transcriptional effects upon perfluoroalkyl acid exposure in diverse species. Reproductive Toxicology. 2009;27(3-4):266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosen MB, Lee JS, Ren H, et al. Toxicogenomic dissection of the perfluorooctanoic acid transcript profile in mouse liver: evidence for the involvement of nuclear receptors PPARα and CAR. Toxicological Sciences. 2008;103(1):46–56. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abbott BD, Wolf CJ, Das KP, et al. Developmental toxicity of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) is not dependent on expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-alpha (PPARα) in the mouse. Reproductive Toxicology. 2009;27(3-4):258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imbeaud S, Graudens E, Boulanger V, et al. Towards standardization of RNA quality assessment using user-independent classifiers of microcapillary electrophoresis traces. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(6, article e56) doi: 10.1093/nar/gni054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]