Abstract

The parasympathetic reflex circuit is controlled by three basic neurons. In the vertebrate head, the sensory, pre- and post-ganglionic neurons that comprise each circuit have stereotypic positions along the anteroposterior (AP) axis, suggesting that the circuit arises from a common developmental plan. Here we show that precursors of the VIIth circuit are initially aligned along the AP axis, where the placode-derived sensory neurons provide a critical “guidepost” through which preganglionic axons and their neural crest-derived postganglionic targets navigate prior to reaching their distant target sites. In the absence of the placodal sensory ganglion, preganglionic axons terminate and the neural crest fated for postganglionic neurons undergo apoptosis at the site normally occupied by the placodal sensory ganglion. The stereotypic organization of the parasympathetic cranial sensory-motor circuit thus emerges from the initial alignment of its precursors along the AP axis, with the placodal sensory ganglion coordinating the formation of the motor pathway.

Keywords: epibranchial placode, neural crest, parasympathetic nervous system, branchial arch, rhombomere, migration, axon pathfinding, specification, differentiation, apoptosis, anteroposterior axis

INTRODUCTION

Wiring the billions of neurons in the vertebrate central and peripheral nervous systems is one of the most complex processes in developmental biology (Ghosh and Kolodkin, 1998; Jessell, 2000; Kandel and Schwartz, 2000). A major challenge is to understand the logic that coordinates the formation and assembly of neurons serving a common circuit, a formidable task especially when the neurons are separated by great distances. An example of this phenomenon is represented in the vertebrate head by the VIIth, IXth, and Xth parasympathetic cranial nerves, which are involved in regulating the body’s homeostasis, from salivation and heart rate to gastric motility. Each of the cranial nerves consists of a polysynaptic sensory-motor reflex circuit, whereby a stimulus triggers the sensory (afferent) pathway to illicit a visceral response via the motor (efferent) pathway (Fig. 1A). The motor pathway consists of preganglionic motor neurons in the ventral hindbrain that project their axons to neural crest-derived peripheral postganglionic neurons imbedded within visceral target tissues that they innervate in the head, neck, thoracic, and abdominal regions of the body (Enomoto et al., 2000; Jacob et al., 2000; Kandel and Schwartz, 2000). The sensory pathway consists of epibranchial placode-derived sensory neurons whose peripheral processes innervate visceral tissues and central processes project to the dorsal hindbrain to either sensory relay neurons or directly to preganglionic motor neurons, thereby completing the reflex circuit (Kandel and Schwartz, 2000; Begbie and Graham, 2001; Barlow, 2002; Baker and Schlosser, 2005). The formation and assembly of the reflex circuit may best be understood from the perspective of the developing head, when it is organized into simple repeating units along the rostrocaudal axis (D’Amico-Martel and Noden, 1983; Lumsden and Keynes, 1989; Lumsden et al., 1991; Bell et al., 1999; Trainor and Krumlauf, 2000). Each repeating unit consists of a rhombomere or two and an adjacent branchial arch – a positional match mediated by rhombomere-derived neural crest (Lumsden and Keynes, 1989; Lumsden et al., 1991). We hypothesize that the positional match between the neural crest and the epibranchial placode from the adjacent branchial arch may underlie the cellular mechanism that regulates the formation and assembly of the cranial parasympathetic reflex circuit. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the formation and assembly of the parasympathetic reflex circuit of the VIIth cranial nerve at single-cell resolution with the goal of identifying a conserved cellular mechanism that applies to all parasympathetic cranial nerve circuits.

Figure 1. A model showing the interaction between the epibranchial placode and neural during the development of the parasympathetic reflex circuit.

(A) Schematic transverse view through one-half of the developing hindbrain showing the parasympathetic reflex circuit (epibranchial placode-derived sensory neuron, blue; nucleus of the solitary tract, black; preganglionic motor neuron, green; postganglionic motor neuron, red).

(B) Schematic transverse view through one-half of the developing hindbrain showing the embryonic origin of the sensory and motor neurons of the parasympathetic reflex circuit (epibranchial placode - origin of sensory ganglion, blue); neural crest - origin of postganglionic neurons, green).

(C, D) Schematic transverse view through one-half of the developing hindbrain showing that neural crest cells facilitate the inward migration and central projection of the epibranchial placode-derived sensory ganglion.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

It was previously shown in the chick embryo that surgical removal of the hindbrain results in the elimination of the r4 neural crest that normally engages the epibranchial placode-derived geniculate sensory ganglion (Begbie and Graham, 2001). In the absence of the hindbrain, the geniculate ganglion fails to migrate away from the ectoderm and project to the hindbrain; thus forming a model for how placodal sensory neurons integrate with the hindbrain (Fig. 1A-C). However, it remains to be determined whether the geniculate sensory ganglion may reciprocate to influence the development of r4-derived neural crest (Barlow, 2002). To address this issue, we focused on the development of r4 neural crest-derived parasympathetic postganglionic neurons of the sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia, the motor complement of the geniculate sensory ganglia (Arenkiel et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2008). Using the Cre/LoxP system in the mouse, we performed a form of subtractive lineage labeling analyses to better define the rhombomere origin of the sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia, as most reporters do not label single rhombomeres (Mansouri et al., 1996; Srinivas et al., 2001; Arenkiel et al., 2003; Macatee et al., 2003; Keller et al., 2004; Farago et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2008). Lineage labeling of Pax7, Hoxb1, and Hoxa3, which marks neural crest from midbrain/r3/r5 (Pax7), r4-r7 (Hoxb1), and r5-r7 (Hoxa3), respectively, confirmed that the sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia arise predominantly from Hoxb1 lineage-labeled r4 neural crest (Fig. 2A, B; Supplementary Fig. S1). The location of the Hoxb1 lineage-labeled sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia in BA1, however, suggests that a small population of r4 neural crest deviate from the major neural crest stream that migrate into BA2 (Fig. 2C, D).

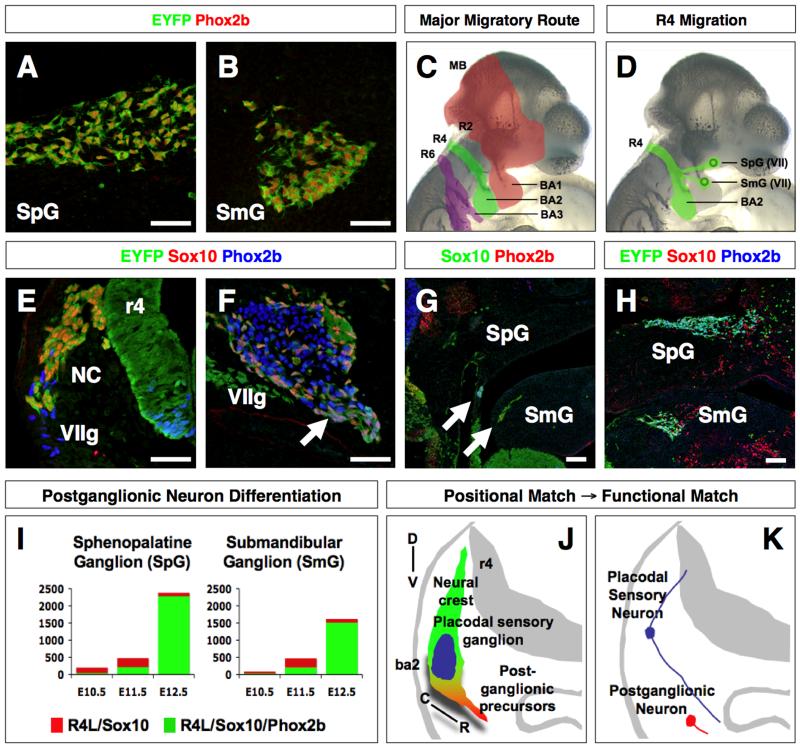

Figure 2. Engagement of Hoxb1 lineage-labeled r4 neural crest cells with the geniculate ganglion in BA2 is required for the formation of parasympathetic postganglionic neurons of the VIIth cranial nerve.

(A, B) Sagittal sections through the sphenopalatine (SpG) and submandibular (SmG) ganglia of 12.5 dpc embryos harboring the Hoxb1 lineage EYFP reporter. Sections were immunolabeled for EYFP (green) and Phox2b (red).

(C) Summary of the major migratory route of midbrain (MB)- and rhombomere (R)-derived neural crest cells into the adjacent branchial arch (BA).

(D) Summary of the rostral migratory route of r4-derived neural crest cells from BA2 to the maxillary and mandibular divisions of BA1, where they proliferate and differentiate into the sphenopalatine (SpG) and submandibular (SmG) ganglia of the VIIth cranial nerve.

(E) Transverse section through BA2 of a 9.5 dpc embryo harboring the Hoxb1-lineage EYFP reporter. The section was immunolabeled for EYFP (green), Sox10 (red), and Phox2b (blue). r4-derived neural crest cells (NC, yellow) are shown to be engaged with the Phox2b-single positive geniculate ganglion (VIIg).

(F) Transverse section through BA2 of an 11.5 dpc embryo harboring the Hoxb1-lineage EYFP reporter. The section was immunolabeled for EYFP (green), Sox10 (red), and Phox2b (blue). The arrow indicates Hoxb1 lineage-labeled r4 neural crest cells expressing EYFP along with Sox10 and Phox2b. The parasympathetic (visceral) sensory neuron in the geniculate ganglion (VIIg) expresses only Phox2b. The EYFP/Sox10-double positive cells in the geniculate ganglion may represent future glial or connective tissue.

(G) Sagittal section through the maxillary and mandibular divisions of BA1 of an 11.5 dpc embryo harboring the Hoxb1-lineage EYFP reporter. The section was immunolabeled for EYFP (green), Sox10 (red), and Phox2b (blue). Arrows show EYFP/Sox10/Phox2b-triple positive cells migrating rostrally just beneath the nasal and oral epithelia.

(H) Sagittal section through the maxillary and mandibular divisions of BA1 of a 12.5 dpc embryo harboring the Hoxb1-lineage EYFP reporter. The section was immunolabeled for EYFP (green), Sox10 (red), and Phox2b (blue). The EYFP/Sox10/Phox2b-triple positive cells were observed in the sphenopalatine (SpG) and submandibular (SmG) ganglia.

(I) Quantitative analysis of the number of the postganglionic neurons in the sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia in 10.5, 11.5, and 12.5 dpc embryos harboring the Hoxb1-lineage EYFP reporter. Sagittal sections from each developmental stage were immunolabeled for EYFP, Sox10 and Phox2b. Red bar represents EYFP/Sox10-double positive cells and the green bar represent EYFP/Sox10/Phox2b-triple positive cells. Each bar represents the total number of cells per ganglion (n=3/stage). The extensive proliferation and differentiation occurred between 11.5 and 12.5 dpc in both sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia. We observed that the expression of Sox10 diminished after 12.5 dpc, whereas Phox2b expression remained high.

(J) Schematic transverse view through one-half of the developing hindbrain summarizing the migratory route of Hoxb1 lineage-labeled r4 neural crest cells. The majority of Sox10-single positive r4 neural crest cells (green) engage the geniculate ganglion (blue) in BA2. Subsequently, they emerge as Sox10/Phox2b-double positive cells (red) en route to BA1, where they proliferate and differentiate into postganglionic neurons of the sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia (D, dorsal; V, ventral; C, caudal; R, rostral).

(K) Schematic transverse view through one-half of the developing hindbrain showing the embryonic origin of the sensory and postganglionic (motor) neurons of the parasympathetic reflex circuit (epibranchial placode - origin of the sensory ganglion, blue; neural crest cells - origin of the postganglionic neuron, red).

Scale bar = 50μm in A, B, E-H.

To follow the fate of the rostral migratory population of r4 neural crest, we performed detailed spatiotemporal and quantitative analyses of Hoxb1 lineage-labeled r4 neural crest. In 9.5 dpc embryos, we observed a population of EYFP-labeled r4 neural crest that expresses the neuroglial determinant Sox10 (Southard-Smith et al., 1998; Britsch et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2003) migrating towards the anterior cleft of BA2, the site of origin of the geniculate ganglion (Fig. 2E; labeled by the autonomic neuron determinant Phox2b (Pattyn et al., 1999; Dauger et al., 2003). Between 10.5-11.5 dpc, the Sox10/EYFP-labeled r4 neural crest that engaged the geniculate ganglion began to express Phox2b (Fig. 2F; triple-labeled neural crest, arrow; n=6/stage). This neural crest population then traveled from the geniculate ganglion as a migratory chain to the prospective sites of the sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia in BA1 (Fig. 2G, arrows). Upon arrival at these sites, the r4 neural crest population undergo rapid cell division, as indicated by a significant increase in cell number and coexpression of BrdU from 10.5 to 12.5 dpc (Fig. 2I, J, and Supplementary Fig. S2; n=3/stage). The sustained expression of Sox10 in the r4 neural crest between 9.5 and 12.5 dpc suggests that postganglionic neurons in the head, like those in the gut and dorsal aorta (Southard-Smith et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2003), are dependent on Sox10. Indeed, we discovered that Sox10 is required for survival of the Hoxb1 lineage-labeled r4 neural crest fated for the sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia (Supplementary Fig. S3). This finding provides evidence for a cell autonomous regulation of the r4 neural crest population. However, the associated up-regulation of Phox2b expression as the r4 neural crest population migrates through the geniculate ganglion suggests a non-cell autonomous influence by the geniculate ganglion (Fig. 2F-H).

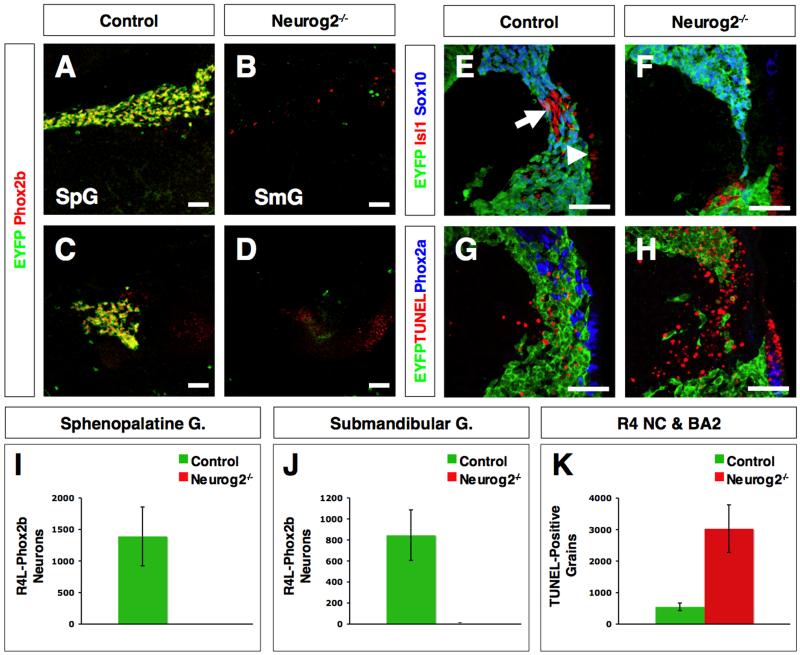

To address a possible non-cell autonomous role of the geniculate ganglia in r4 neural crest development, we analyzed Neurog2 mutant embryos lacking the geniculate ganglia (Fode et al., 1998). The absence of the geniculate ganglia in Neurog2 mutant embryos is a consequence of a defect in delamination of placodal cells from the ectoderm. We also placed the Hoxb1 lineage reporter in the background of Neurog2 mutant embryos to follow the fate of r4 neural crest. Analysis of Neurog2 mutant embryos from 10.5 to 14.5 dpc showed few r4 neural crest-derived Sox10/Phox2b-positive cells in the prospective sites of the sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia at 12.5 dpc (Fig. 3A-D, I, J; n=6). Moreover, the absence of EYFP labeling eliminates the possibility that r4-derived neural crest arrived at these sites and changed cell fate (Fig. 3B, D). No difference in TUNEL-positive cells was observed between groups, therefore ruling out the possibility that the neural crest was eliminated by apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. S4). These data suggest that the r4 neural crest defects in Neurog2 mutant embryos likely occurred at an earlier stage of neural crest differentiation or migration. Analysis of 9.5 dpc Neurog2 mutant embryos confirmed this hypothesis, showing a decrease in the Hoxb1 lineage-labeled r4 neural crest that normally engages the geniculate ganglion in BA2 (Fig. 3E, F; n=3/group). The decrease in Hoxb1 lineage-labeled neural crest in the area normally occupied by the geniculate ganglion was associated with a significant increase in TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 3G, H, K; n=3/group). These analyses enabled us to narrow the r4 neural crest defect to 9.5 dpc, the stage when r4 neural crest and placode-derived geniculate sensory neurons in BA2 first engage. We also found no evidence for Neurog2 protein expression in Hoxb1 lineage-labeled r4 neural crest at this stage (Supplementary Fig. S5). These observations suggest that the loss of the r4 neural crest population is caused non-cell autonomously by the absence of the geniculate ganglion. Together, these findings show that the placodal geniculate sensory ganglion reciprocates to influence the formation of the positionally matched r4 neural crest fated for postganglionic neurons of the sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia.

Figure 3. Placode-derived geniculate sensory ganglia are required non-cell autonomously for survival of the r4 neural crest fated for postganglionic neurons of the VIIth cranial nerve.

(A-D) Sagittal sections through the sphenopalatine (A, B; SpG) and submandibular (C, D; SmG) ganglia of 12.5 dpc control (A, C; n=6) and Neurog2 mutant (B, D; n=6) embryos harboring the Hoxb1-lineage YFP reporter immunolabeled for EYFP (green) and Phox2b (red).

(E-H) Transverse sections through BA2 of 9.5 dpc control (E, G; n=3) and Neurog2 mutant (F, H; n=3) embryos harboring the Hoxb1-lineage YFP reporter. The sections were immunolabeled for EYFP (E-H; green), Isl1 (E, F; red), Sox10 (E, F; blue) and Phox2a (G, H; blue). Apoptosis was visualized by TUNEL assay (G, H; red). Arrow indicates the geniculate ganglion (E) that has delaminated from the surface epibranchial placode (arrowhead in E). The thinning rostral r4-derived neural crest migratory stream (F) was observed in the same region where the increase in TUNEL-positive grains (panel H) was detected in Neurog2 mutant embryos.

(I, J) Quantitative analysis of the number of EYFP/Phox2b-double positive postganglionic neurons in the sphenopalatine (I) and submandibular (J) ganglia of 12.5 dpc control (n=3) and Neurog2 (n=3) mutant embryos harboring the Hoxb1-lineage YFP reporter. r4 neural crest-derived postganglionic neurons are almost completely eliminated in Neurog2 mutant embryos compared to control littermates (p<0.005). All EYFP/Phox2b-double positive neurons were counted in each ganglion. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

(K) Quantitative analysis of the number of TUNEL-positive grains in the r4 and BA2 region of 9.5 dpc control (n=3) and Neurog2 mutant (n=3) embryos. A significant increase in apoptosis was observed in Neurog2 mutant embryos compared to control littermates (p<0.005). All TUNEL-positive grains per neural crest stream were counted. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Scale bar = 50μm in A-H.

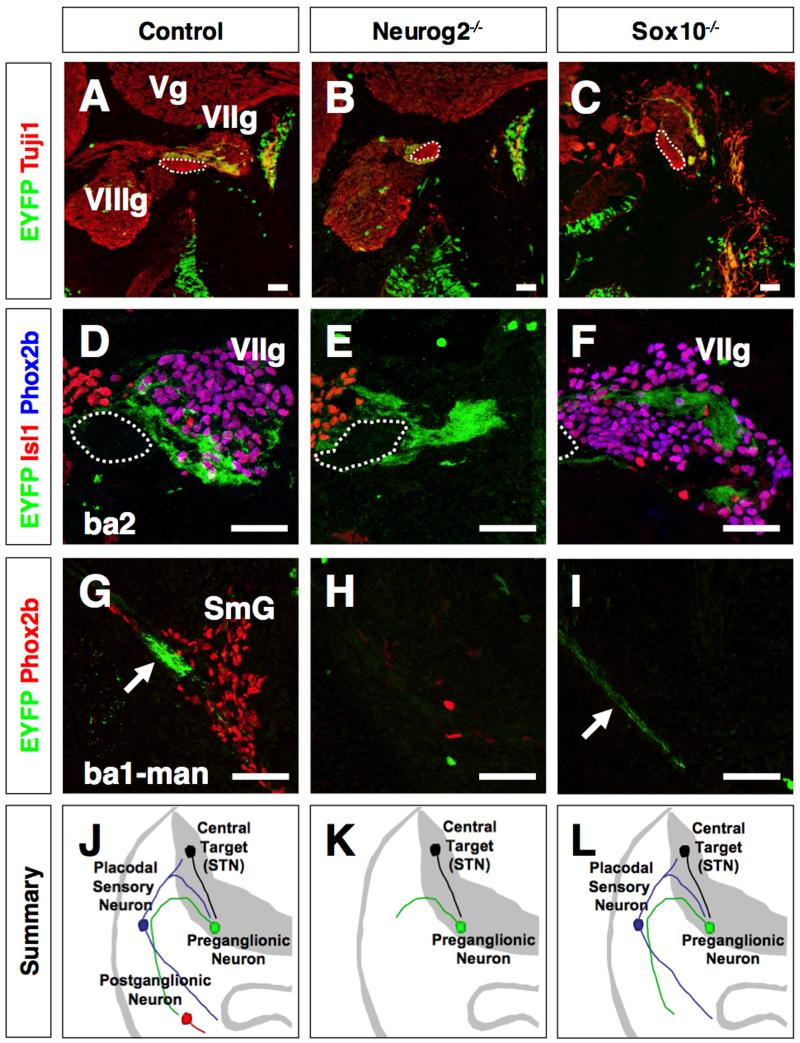

Like the migratory route of the r4 neural crest, the axons of r5-derived preganglionic neurons travel a similar course, exiting r4 and traversing through the geniculate ganglion before reaching their sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia targets in BA1 (Jacob and Guthrie, 2000; Jacob et al., 2000; Guthrie, 2007; Schwarz et al., 2008). This correlation suggests that the axons of preganglionic neurons may also depend on the geniculate ganglion for cues to reach their neuronal targets in BA1. To address this issue, we analyzed geniculate ganglia-deficient Neurog2 mutant embryos harboring the Hoxa3 lineage reporter to label r5-derived preganglionic neurons. In 12.5 control embryos, the Tuj1/EYFP-labeled preganglionic axons can be visualized exiting r4 and traversing through the Phox2b/Isl1-positive geniculate ganglion en route to their terminal targets, the Phox2b-expressing sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia (Fig. 4A, D, G; Supplementary Fig. S6; n=6 per experimental group). In Neurog2 mutant embryos, the Tuj1/EYFP-labeled preganglionic axons terminate abruptly in the region normally occupied by the geniculate ganglion, suggesting that the geniculate ganglion is required for the axonal trajectory from BA2 to their targets in BA1 (Fig. 4B, E, H; Supplementary Fig. S6). As previously suggested, this axonal defect may be due to the absence of the sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia in Neurog2 mutant embryos, potential sources for axon guidance cues (Jacob et al., 2000) (Fig. 3A-D). We therefore analyzed Sox10 mutant embryos, in which the placode-derived geniculate ganglia are intact but the sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia are missing (Supplementary Fig. S3). In Sox10 mutant embryos, we observed that the Hoxa3 lineage-labeled preganglionic axons traverse through the geniculate ganglion and proceed to their prospective target areas in BA1, despite missing the r4 neural crest-derived sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia (Fig. 4C, F, I; Supplementary Fig. S6). From these findings, we conclude that early axon pathfinding of r5-derived preganglionic neurons is dependent on the geniculate ganglion, but surprisingly not on their terminal neural crest-derived neuronal targets (Summarized in Fig. 4J-L).

Figure 4. Placode-derived geniculate sensory ganglia act as an intermediate target for distal axon pathfinding of preganglionic motor neurons of the VIIth cranial nerve.

(A-C) Sagittal sections through the geniculate ganglion of 12.5 dpc control (A, n=6), Neurog2 (B, n=6) and Sox10 (C, n=6) mutant embryos harboring the Hoxa3-lineage EYFP reporter. The sections were immunolabeled for EYFP (green) and Tuji1 (red). Hoxa3 lineage-labeled r5 preganglionic axons were positive for EYFP and Tuj1. The preganglionic axons in Neurog2 mutant embryos stopped near the axon bundle of the facial branchial motor neurons (dotted outline), the site normally occupied by the geniculate sensory ganglion. The axons of the facial branchial motor neurons in Neurog2 and Sox10 mutant embryos project normally in BA2. Scale bar = 100 μm.

(D-F) Sagittal sections though the geniculate ganglion of 12.5 dpc control (D; n=6), Neurog2 (E; n=6), and Sox10 (F; n=6) mutant embryos harboring the Hoxa3-lineage EYFP reporter. The sections were immunolabeled for EYFP (green), Isl1 (red), and Phox2b (blue). Isl1/Phox2b-double positive and Isl1-single positive cells indicated the sensory neurons of the geniculate (VIIg) and vestibulocochlear ganglion, respectively. The axons of preganglionic neurons reached the region normally occupied by the geniculate ganglion in Neurog2 mutant embryos. However, these preganglionic axons failed to extend beyond this region compared to control and Sox10 mutant embryos. The dotted outline indicates the axon bundle of facial branchial motor neurons. Scale bar = 50 μm.

(G-I) Transverse sections through the submandibular ganglion (SmG) of 12.5 dpc control (G; n=6), Neurog2 (H; n=6), and Sox10 (I; n=6) mutant embryos harboring the Hoxa3-lineage EYFP reporter. Few Phox2b-single positive cells were detected in Neurog2 and Sox10 mutant embryos, suggesting that the neural crest-derived postganglionic neurons are controlled non-cell autonomously by Neurog2 and cell autonomously Sox10. The r5-derived preganglionic motor axons (arrow) project to the submandibular ganglion or its normal site in control and Sox10 mutant embryos, but fail in Neurog2 mutant embryos. These data suggest that the geniculate ganglion (intermediate target), but not the submandibular ganglion (terminal target), as previously suggested (Jacob et al., 2000), are required for the distal axon pathfinding of r5-derived preganglionic motor neurons of the VIIth cranial nerve.

Scale bar = 50 μm.

(J-L) Summary showing the axon pattern of pre- and post-ganglionic neurons of the VIIth cranial nerve in control (J), Neurog2 (K), and Sox10 (L) mutant embryos. The preganglionic motor axons (green) can be divided into proximal (r4 to geniculate ganglion) and distal segments (geniculate ganglion to sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia). The axon pathfinding of the distal segment requires the epibranchial placode-derived sensory neurons as an intermediate targets (K, Neurog2 mutation), but not the neural crest-derived terminal targets (L, Sox10 mutation). The proximal segment is independent of both intermediate and terminal targets.

Our study suggests that the formation and assembly of a common cranial parasympathetic reflex circuit manifests from the reciprocal interaction of its precursors. It was previously shown that the r4-derived neural crest is critical for the integration of the placode-derived geniculate sensory ganglia in the adjacent BA2 with the hindbrain (Begbie and Graham, 2001). Conversely, we show that the epibranchial placode-derived geniculate sensory ganglion controls the survival of the r4 neural crest population that gives rise to postganglionic neurons of the parasympathetic sphenopalatine and submandibular ganglia. Together, these findings provide a cellular mechanism by which the reciprocal interaction between the neural crest and placode-derived sensory ganglia from the same rostrocaudal level (positional match) (Lumsden and Keynes, 1989; Lumsden et al., 1991; Trainor and Krumlauf, 2000) contributes to the formation of a common parasympathetic cranial nerve (functional match). Our data also indicate that the placode-derived geniculate sensory ganglion in BA2 acts as a critical intermediate target for the developing relay motor pathway of the VIIth cranial nerve. We show that the geniculate sensory ganglion in BA2 is required to establish the relationship between the r5-derived preganglionic and r4 neural crest-derived postganglionic neurons.

The origin of the 3-neuron parasympathetic circuit of the VIIth cranial nerve thus appears to follow a highly conserved 2:1 periodicity (r4 and r5:BA2) (Lumsden and Keynes, 1989; Chipman et al., 2004). In the vertebrate head, this organizing principle was originally described for the branchial motoneuron system (Lumsden and Keynes, 1989; Bell et al., 1999; Cordes, 2001; Guthrie, 2007). In this system, the neural crest is the central player that integrates hindbrain branchial motor neurons with their corresponding skeletal muscle targets in the adjacent branchial arch (Lumsden and Keynes, 1989; Lumsden et al., 1991; Bell et al., 1999; Arenkiel et al., 2003; Arenkiel et al., 2004; Matsuoka et al., 2005; Guthrie, 2007). With respect to the developing parasympathetic reflex circuit, we show that the placodal sensory ganglion takes center stage, orchestrating the formation and assembly of pre- and post-ganglionic neurons. In the absence of the placodal sensory ganglion, the axons of preganglionic neurons fail to extend to their terminal target areas, much in the same way that developing neurons in the grasshopper leg rely on “guidepost” cells to reach their terminal targets (Bentley and Caudy, 1983). In contrast to “guidepost” cells, the placodal sensory ganglion ultimately becomes integrated into a common neural circuit. Furthermore, we found that the placodal sensory ganglion also provides survival and possibly differentiation cues to the neural crest population that gives rise to postganglionic neurons. Taken together, our study establishes the placodal sensory ganglion as a convergence node for cellular interaction that is critical for establishing the cranial parasympathetic reflex circuit.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Drs. M. Capecchi, A. Moon, D. Anderson, W. Pavan, M. Wegner, F. Costantini, and C. Goridis for providing mice and reagents; Drs. T. Jessell, P. Mueller, A. Moon, and C. Wilson for critical review of the manuscript; members of the SNRP-SAC and N.W. Ulan for helpful comments; and H.Y. Kao and O. Trevino for technical assistance. This study was supported in part by grants to G.O.G from the NIH (1U54NS060658-01A10002) and the Whitehall Foundation.

APPENDIX

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

The Sox10, Neurog2 mutant mice and Hoxb1-Ires-Cre, Hoxa3-Ires-Cre, and Rosa-EYFP reporter mice used for this study have been previously published and generously provided by Drs. W. Pavan, M. Wegner, D. Anderson, M. Capecchi, A. Moon, and F. Costantini. Care of the mice used in this study was in accordance with institutional guidelines (IACUC protocol #MU041). The morning of the appearance of a vaginal plug was considered to be 0.5 day post coitum (dpc). Transgenic or knockout mice were identified by PCR analysis. The Neurog2 mutant allele was identified as a 250 bp products using primers 5′ CAT CGC TCT AGA CGC AGT GA 3′ and 5′ TAC CGG TGG ATG TGG AAT GT 3′. The Neurog2 wild allele was identified as a 167 bp products using primers 5′ CAT CGC TCT AGA CGC AGT GA 3′ and 5′ TCC CAG AAT GGA CAG GGT AA 3′. The Neurog2 mutant allele was identified as a 199 bp products using primers 5′ GTC GAA AAC CCG AAA CTG TG 3′ and 5′ GAT GAT GCT CGT GAC GGT TA 3′. The Sox10 wild allele was identified as a 269 bp products using primers 5′ CCT TCA TTG AGG AGG CTG AG 3′ and 5′ TCT GGG TTC CCA TCT GAC AT 3′.

Immunohistochemistry

Embryos were dissected in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 30 min at 4°C and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose at 4°C, followed by embedding in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek). The cryostat sections were blocked in PBS-T (phosphate-buffered saline with 0.02% TritonX-100) with 5% skimmed milk and 5% normal goat sera for 5 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with the appropriate dilution of primary antibody in PBS-T containing 2% skimmed milk and 5% goat sera overnight at 4°C. The following primary antibodies used for this study were mouse anti-Isl1/2 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa, IA), mouse anti-Sox10 (a gift from D. Anderson), rabbit anti-Phox2b and anti-Phox2a (a gift from C. Goridis), and sheep anti-GFP (Invitrogen). For visualization of antibody binding, the sections were incubated with Alexa 594 conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Fab)2 fragment (Invitrogen), Alexa 647 conjugated goat anti-mouse (Fab)2 fragment (Invitrogen) and Alexa 488 conjugated goat anti-mouse (Fab)2 (Invitrogen) for 45min at 4°C. Detection of apoptotic cells was performed with In situ cell death detection kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). The sections were incubated with TdT and secondary antibodies for 1hr at 37°C. The slides were examined with a Zeiss LSM 5 PASCAL confocal microscope. Cell counting was performed using Imaris software (Bitplane AG, Zurich, Switzerland) in combination with manual verification of the automated results.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical analysis of differences between two groups was performed using the unpaired Student’s t-test (two-tailed analysis). Differences with P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

REFERENCES

- Arenkiel BR, Gaufo GO, Capecchi MR. Hoxb1 neural crest preferentially form glia of the PNS. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:379–386. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenkiel BR, Tvrdik P, Gaufo GO, Capecchi MR. Hoxb1 functions in both motoneurons and in tissues of the periphery to establish and maintain the proper neuronal circuitry. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1539–1552. doi: 10.1101/gad.1207204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CV, Schlosser G. The evolutionary origin of neural crest and placodes. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. 2005;304:269–273. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow LA. Cranial nerve development: placodal neurons ride the crest. Curr Biol. 2002;12:R171–173. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00734-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begbie J, Graham A. Integration between the epibranchial placodes and the hindbrain. Science. 2001;294:595–598. doi: 10.1126/science.1062028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E, Wingate RJ, Lumsden A. Homeotic transformation of rhombomere identity after localized Hoxb1 misexpression. Science. 1999;284:2168–2171. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley D, Caudy M. Pioneer axons lose directed growth after selective killing of guidepost cells. Nature. 1983;304:62–65. doi: 10.1038/304062a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britsch S, Goerich DE, Riethmacher D, Peirano RI, Rossner M, Nave KA, Birchmeier C, Wegner M. The transcription factor Sox10 is a key regulator of peripheral glial development. Genes Dev. 2001;15:66–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.186601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipman AD, Arthur W, Akam M. A double segment periodicity underlies segment generation in centipede development. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1250–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes SP. Molecular genetics of cranial nerve development in mouse. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:611–623. doi: 10.1038/35090039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico-Martel A, Noden DM. Contributions of placodal and neural crest cells to avian cranial peripheral ganglia. Am J Anat. 1983;166:445–468. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001660406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauger S, Pattyn A, Lofaso F, Gaultier C, Goridis C, Gallego J, Brunet JF. Phox2b controls the development of peripheral chemoreceptors and afferent visceral pathways. Development. 2003;130:6635–6642. doi: 10.1242/dev.00866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto H, Heuckeroth RO, Golden JP, Johnson EM, Milbrandt J. Development of cranial parasympathetic ganglia requires sequential actions of GDNF and neurturin. Development. 2000;127:4877–4889. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.22.4877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farago AF, Awatramani RB, Dymecki SM. Assembly of the brainstem cochlear nuclear complex is revealed by intersectional and subtractive genetic fate maps. Neuron. 2006;50:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fode C, Gradwohl G, Morin X, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Goridis C, Guillemot F. The bHLH protein NEUROGENIN 2 is a determination factor for epibranchial placode-derived sensory neurons. Neuron. 1998;20:483–494. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80989-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Kolodkin AL. Specification of neuronal connectivity: ETS marks the spot. Cell. 1998;95:303–306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie S. Patterning and axon guidance of cranial motor neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:859–871. doi: 10.1038/nrn2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob J, Guthrie S. Facial visceral motor neurons display specific rhombomere origin and axon pathfinding behavior in the chick. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7664–7671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07664.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob J, Tiveron MC, Brunet JF, Guthrie S. Role of the target in the pathfinding of facial visceral motor axons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:14–26. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessell TM. Neuronal specification in the spinal cord: inductive signals and transcriptional codes. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:20–29. doi: 10.1038/35049541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER, Schwartz JH. Principles of neural science. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2000. p. xli.p. 1414. [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Hansen MS, Coffin CM, Capecchi MR. Pax3:Fkhr interferes with embryonic Pax3 and Pax7 function: implications for alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cell of origin. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2608–2613. doi: 10.1101/gad.1243904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lo L, Dormand E, Anderson DJ. SOX10 maintains multipotency and inhibits neuronal differentiation of neural crest stem cells. Neuron. 2003;38:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden A, Keynes R. Segmental patterns of neuronal development in the chick hindbrain. Nature. 1989;337:424–428. doi: 10.1038/337424a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden A, Sprawson N, Graham A. Segmental origin and migration of neural crest cells in the hindbrain region of the chick embryo. Development. 1991;113:1281–1291. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macatee TL, Hammond BP, Arenkiel BR, Francis L, Frank DU, Moon AM. Ablation of specific expression domains reveals discrete functions of ectoderm- and endoderm-derived FGF8 during cardiovascular and pharyngeal development. Development. 2003;130:6361–6374. doi: 10.1242/dev.00850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri A, Stoykova A, Torres M, Gruss P. Dysgenesis of cephalic neural crest derivatives in Pax7−/− mutant mice. Development. 1996;122:831–838. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka T, Ahlberg PE, Kessaris N, Iannarelli P, Dennehy U, Richardson WD, McMahon AP, Koentges G. Neural crest origins of the neck and shoulder. Nature. 2005;436:347–355. doi: 10.1038/nature03837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattyn A, Morin X, Cremer H, Goridis C, Brunet JF. The homeobox gene Phox2b is essential for the development of autonomic neural crest derivatives. Nature. 1999;399:366–370. doi: 10.1038/20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz Q, Waimey KE, Golding M, Takamatsu H, Kumanogoh A, Fujisawa H, Cheng HJ, Ruhrberg C. Plexin A3 and plexin A4 convey semaphorin signals during facial nerve development. Dev Biol. 2008;324:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southard-Smith EM, Kos L, Pavan WJ. Sox10 mutation disrupts neural crest development in Dom Hirschsprung mouse model. Nat Genet. 1998;18:60–64. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor PA, Krumlauf R. Patterning the cranial neural crest: hindbrain segmentation and Hox gene plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:116–124. doi: 10.1038/35039056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Zhou Y, Barcarse EA, O’Gorman S. Altered neuronal lineages in the facial ganglia of Hoxa2 mutant mice. Developmental Biology. 2008;314:171–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.