Abstract

Heme oxygenase-1 may exert cytoprotective effects. In this study we examined the sensitivity of heme oxygenase-1 knockout (HO-1−/−) mice to renal ischemia by assessing glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and cytokine expression in the kidney, and inflammatory responses in the systemic circulation and in vital extrarenal organs. Four hours after renal ischemia, the GFR of HO-1−/− mice was much lower than that of wild-type mice in the absence of changes in renal blood flow or cardiac output. Eight hours after renal ischemia, there was a marked induction of interleukin-6 (IL-6) mRNA and its downstream signaling effector, phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (pSTAT3), in the kidney, lung, and heart in HO-1−/− mice. Systemic levels of IL-6 were markedly and uniquely increased in HO-1−/− mice after ischemia as compared to wild-type mice. The administration of an antibody to IL-6 protected against the renal dysfunction and mortality observed in HO-1−/− mice following ischemia. We suggest that the exaggerated production of IL-6, occurring regionally and systemically following localized renal ischemia, in an HO-1-deficient state may underlie the heightened sensitivity observed in this setting.

Keywords: interleukin-6, cytokines, cytoprotection, renal hemodynamics

Ischemic insults, localized to the kidney, elicit responses both within and beyond the injured organ. Regional responses in the ischemic kidney may either promote or mitigate renal injury, and among the maladaptive, injurious responses considerable attention is directed to processes that come under the rubric of inflammation.1–6 These processes involve any one or combination of the following: monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, B and T lymphocytes, dendritic cells, as well as assorted cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules.1–6 Along with these and other potentially injurious mechanisms, ischemia also elicits cytoprotective responses which can lessen the severity of ensuing injury by suppressing, at least in part, renal inflammation.7,8

Localized renal ischemia, however, may exert effects that go beyond the confines of the kidney and involve much more than the predictable complications—fluid accumulation and alterations in chemical composition of plasma—occasioned by impaired renal function. Ischemic episodes, restricted to the kidney, can lead to unrestricted inflammatory processes which are widely conveyed by the systemic circulation to organs and tissues far removed from the ischemic kidney.1–12 Localized renal ischemia of sufficient severity, and independent of derangements in fluid and electrolytes, may thus be viewed as an instigator of a systemic inflammatory process with abnormalities appearing in distant organs.

The present studies explored the role of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in influencing renal and systemic responses that occur in the early phase after an acute episode of renal ischemia. HO is the rate-limiting enzyme in the degradation of heme, and such activity is possessed by two isozymes: HO-1, the inducible isoform which can exert cytoprotective properties in injured tissue, and HO-2, the constitutive isoform.13–18 These studies represent the continuation of an investigative line initiated by the demonstration that induction of HO-1 in the kidney exposed to heme proteins conferred marked cytoprotective effects.19 As HO-1 was subsequently shown to be induced in the kidney subjected to ischemia, the question inevitably arose whether such induction of HO-1 in the ischemic kidney was adaptive or maladaptive in nature. While studies based on the use of pharmacologic inhibitors of HO activity to examine this issue yielded conflicting results,20,21 an approach based on HO-1−/− mice demonstrated that such a genetic deficiency markedly increases the sensitivity to renal injury, as reflected by increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine measured 24 h after the ischemic insult, and increased mortality following the ischemic episode.22

This study was undertaken to further analyze the basis for such sensitivity, and began with an analysis of the renal hemodynamic and inflammatory responses in the early phase after ischemia. As the previously observed mortality in HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury was not readily explained by renal dysfunction,22 analyses of relevant cytokine expression in the systemic circulation and distant vital organs were also undertaken.

RESULTS

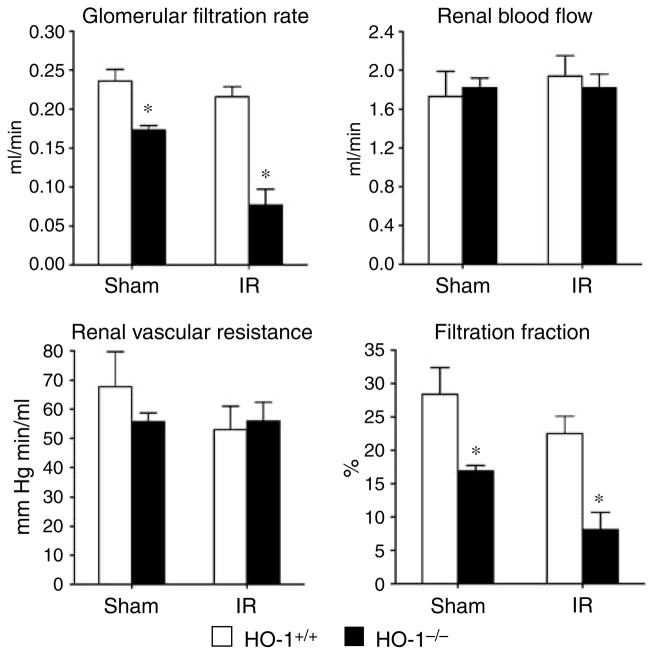

Renal hemodynamic studies at 4 h after ischemia–reperfusion

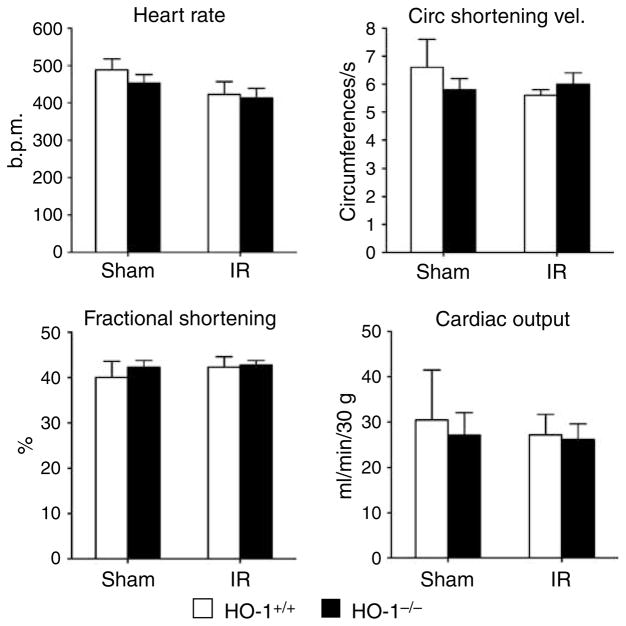

HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion exhibited significant impairment in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as compared to similarly treated HO-1+/+ mice (Figure 1). These changes were not associated with impairment in renal blood flow (RBF) or an increase in renal vascular resistance, but were accompanied by a lower filtration fraction. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was comparable in HO-1+/+ mice and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion (94±2 versus 98±3 mm Hg, P = NS). Mean kidney weights were greater in HO-1−/− mice as compared with HO-1+/+ mice after ischemia–reperfusion (0.33±0.03 versus 0.44±0.02 g, P< 0.05), but not after sham ischemia (0.31±0.03 versus 0.34±0.02 g, P = NS). GFR factored for kidney weight was significantly lower in HO-1−/− mice as compared with HO-1+/+ mice after ischemia (0.66±0.04 versus 0.20±0.10 ml/min/g, P< 0.05). Although less pronounced than after ischemia, GFR and filtration fraction were impaired in HO-1−/− mice as compared with HO-1+/+ mice following sham ischemia (Figure 1). Studies of cardiac function, undertaken 4 h after ischemia, revealed no significant differences among all four groups in any of the assessed indices, in particular cardiac output (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Renal hemodynamics in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IR) or sham ischemia (Sham).

The data demonstrate the following hemodynamic parameters: glomerular filtration rate (GFR), renal blood flow (RBF), renal vascular resistance (RVR), and filtration fraction (FF). n = 4 in each of the HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− groups subjected to sham ischemia; n = 6 and n = 8 (GFR), and n = 5 and n = 7 (RBF, RVR, and FF) in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− groups subjected to IR respectively. *P< 0.05 versus HO-1+/+ mice subjected to the same condition.

Figure 2. Cardiac function in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IR) or sham ischemia (Sham).

The data demonstrate the following: heart rate (beats per minute), circumferential shortening velocity (circumferences/s), fractional shortening (%), and cardiac output (ml/min/30 g). n = 5 in each of the HO-1+/+ Sham and HO-1+/+ IR groups, and n = 6 in each of HO-1−/− Sham and HO-1−/− IR groups.

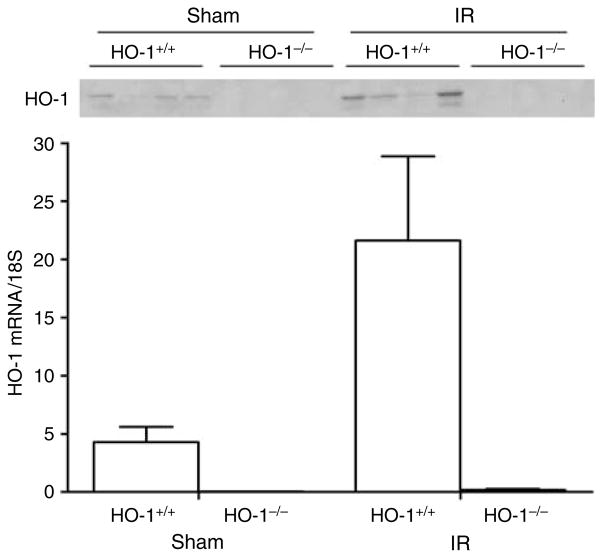

Expression of HO-1 in the kidney 4 h after ischemia–reperfusion

HO-1 mRNA was induced fivefold in the kidney of HO-1+/+ mice following ischemia and was accompanied by more abundant expression of HO-1 protein; HO-1 mRNA and protein were essentially undetectable in the kidneys of HO-1−/− mice subjected to either condition (Figure 3).

Figure 3. HO-1 expression in the kidney 4 h after sham or IR injury.

Upper panel: Western analysis for HO-1 protein expression in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IR) or sham ischemia (Sham). Each lane represents protein extracted from a single kidney of an individual mouse. Equivalency of protein loading was verified by Ponceau staining (not shown). Lower panel: HO-1 mRNA by quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IR) or sham ischemia (Sham). n = 4 in each of the HO-1+/+ Sham and HO-1−/− Sham groups, and n = 6 and n = 8 in HO-1+/+ IR and HO-1−/− IR groups respectively.

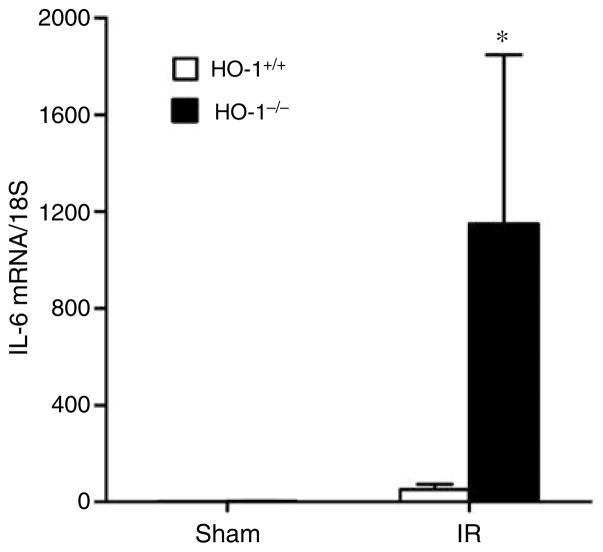

Expression of IL-6 and other cytokines in the kidney 8 h after ischemia–reperfusion

Expression of selected cytokines relevant to renal ischemia was variably increased in the ischemic kidney in HO-1−/− mice as compared with HO-1+/+ mice (Table 1). Interleukin-6 (IL-6) was dramatically induced in the kidney following ischemia in HO-1−/− mice as compared with HO-1+/+ mice (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Cytokine mRNA expression in the kidney 8 h after Sham or IR injury

| HO-1+/+ Sham | HO-1−/− Sham | HO-1+/+ IR | HO-1−/− IR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCP-1 | 67.1±16.0 | 59.8±8.9 | 179.3±36.4 | 397.4±159.1 |

| TNF | 111.0±43.9 | 78.5±23.4 | 217.2±38.9 | 259.4±90.7 |

| ET-1 | 1.7±0.2 | 2.9±1.3 | 3.3±1.0 | 8.1±1.7* |

| IL-10 | 34.4±16.2 | 33.3±16.0 | 49.8±15.8 | 79.4±28.7 |

ET-1, endothelin-1; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; IL, interleukin; IR, ischemia–reperfusion; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; Sham, sham ischemia; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. Cytokine mRNA expression in the kidney 8 h after Sham or IR injury in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice, and assessed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Values are the result of relative quantification performed against a standard curve constructed for each mRNA target, normalized for expression of 18S rRNA, and expressed in arbitrary units. n=4 and n=5 in the HO-1+/+ Sham and HO-1−/− Sham groups respectively, and n=8 and n=7 in the HO-1+/+ IR and HO-1−/− IR groups respectively.

P< 0.05 versus HO-1+/+ IR.

Figure 4. IL-6 mRNA determination by quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR in the kidney in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IR) or sham ischemia (Sham).

n = 4 and n = 5 in the HO-1+/+ Sham and HO-1−/− Sham groups respectively, and n = 8 and n = 7 in the HO-1+/+ IR and HO-1−/− IR groups respectively. *P< 0.05 versus HO-1+/+ mice subjected to the same condition.

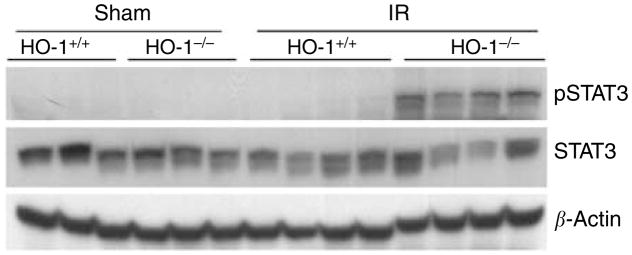

Expression of IL-6-dependent signaling in the kidney 8 h after ischemia–reperfusion

As IL-6 activates the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway, in particular, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3),23 the latter was assessed after ischemia. Phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (pSTAT3), the activated form of STAT3, but not STAT3 itself, was markedly induced in HO-1−/− mice after ischemia, whereas all other groups failed to evince such changes (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Western analysis for pSTAT3 and STAT3 expression in the kidney in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IR) or sham ischemia (Sham).

Each lane represents protein extracted from a single kidney of an individual mouse, and equivalency of protein loading was verified by immunoblotting for β-actin.

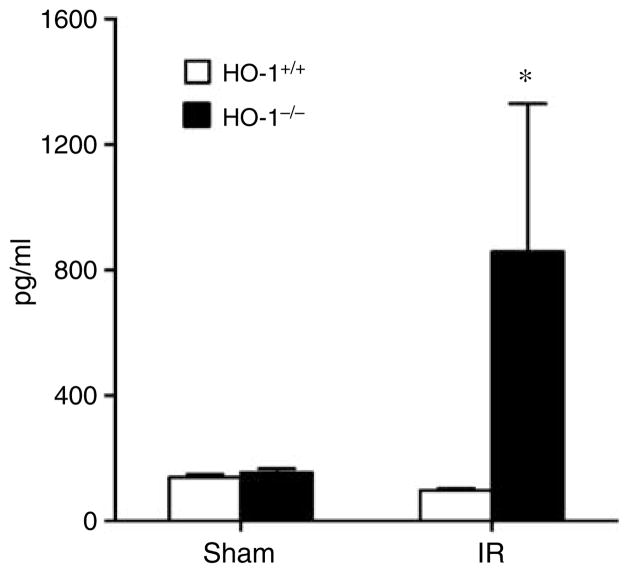

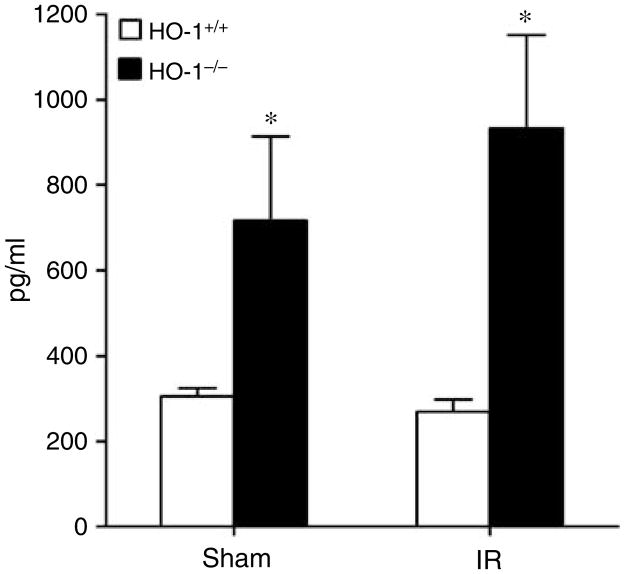

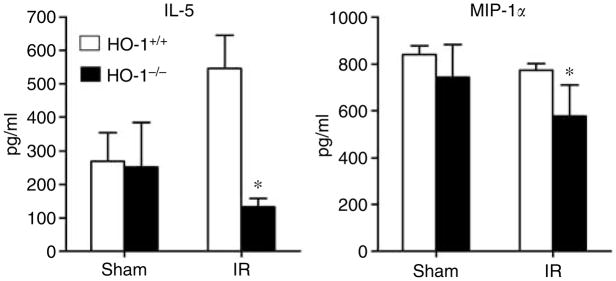

Concentration of serum cytokines at 8 h after renal ischemia–reperfusion

Of these measured cytokines (Table 2 and Figures 6, 7 and 8), the striking finding was that only IL-6 showed the profile depicted in Figure 6, namely, a markedly increased serum level in HO-1−/− mice after ischemia as compared to the other three groups, with comparable IL-6 levels in HO-1−/− and HO-1+/+ mice subjected to sham ischemia (Figure 6). The only other cytokine that was elevated in HO-1−/− mice at this time point after ischemia–reperfusion was IL-12 (p40); however, a similar elevation in IL-12 (p40) in HO-1−/− mice was also observed after sham ischemia (Figure 7). IL-5 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α decreased in HO-1−/− mice following ischemia–reperfusion (Figure 8). All other cytokines were unchanged (Table 2).

Table 2.

Concentration of cytokines in serum 8 h after Sham or IR injury

| HO-1+/+ Sham | HO-1−/− Sham | HO-1+/+ IR | HO-1−/− IR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1α | 348±65 | 377±48 | 424±53 | 490±39 |

| IL-1β | 206±22 | 157±43 | 181±8 | 193±9 |

| IL-2 | 23±5 | 31±7 | 12±2 | 51±41 |

| IL-3 | 11±1 | 21±5 | 14±2 | 10±2 |

| IL-4 | 8±1 | 11±4 | 8±1 | 10±3 |

| IL-9 | 723±59 | 694±41 | 561±31 | 414±82 |

| IL-10 | 250±42 | 425±125 | 209±13 | 383±122 |

| IL-12 (p70) | 800±37 | 1567±371 | 812±74 | 850±438 |

| IL-13 | 297±29 | 294±47 | 227±20 | 209±33 |

| IL-17 | 368±32 | 468±48 | 318±30 | 176±70 |

| Eotaxin | 2320±174 | 2265±227 | 1934±130 | 1815±176 |

| G-CSF | 2741±651 | 2595±447 | 3166±400 | 4182±628 |

| GM-CSF | 161±6 | 165±12 | 144±6 | 134±14 |

| IFN-γ | 195±22 | 274±42 | 151±9 | 110±19 |

| KC | 349±59 | 339±44 | 317±40 | 407±59 |

| MCP-1 | 575±27 | 610±29 | 571±25 | 634±117 |

| MIP-1β | 65±5 | 104±37 | 86±18 | 52±3 |

| RANTES | 288±39 | 419±68 | 363±36 | 223±37 |

| TNF | 1247±91 | 1670±252 | 1128±85 | 1081±171 |

G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL, interleukin; IR, ischemia–reperfusion; KC, keratinocyte-derived chemokine; MIP-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; RANTES, regulated on activation normal T-cell expressed and secreted; Sham, sham ischemia; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Concentrations of cytokines in serum (pg/ml) were determined by a protein array assay 8 h after Sham or IR injury in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice. n=4 and n=5 in the HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− Sham groups respectively, and n=8 and n=7 in the HO-1+/+ IR and HO-1−/− IR groups respectively.

Figure 6. Serum levels of IL-6 in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IR) or sham ischemia (Sham).

n = 4 and n = 5 in the HO-1+/+ Sham and HO-1−/− Sham groups respectively, and n = 8 and n = 7 in the HO-1+/+ IR and HO-1−/− IR groups respectively. *P< 0.05 versus HO-1+/+ mice subjected to the same condition.

Figure 7. Serum levels of IL-12 (p40) in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IR) or sham ischemia (Sham).

n = 4 and n = 5 in the HO-1+/+ Sham and HO-1−/− Sham groups respectively, and n = 8 and n = 7 in the HO-1+/+ IR and HO-1−/− IR groups respectively. *P< 0.05 versus HO-1+/+ mice subjected to the same condition.

Figure 8. Serum levels of IL-5 and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1a in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IR) or sham ischemia (Sham).

n = 4 and n = 5 in the HO-1+/+ Sham and HO-1−/− Sham groups respectively, and n = 8 and n = 7 in the HO-1+/+ IR and HO-1−/− IR groups respectively. *P< 0.05 versus HO-1+/+ mice subjected to the same condition.

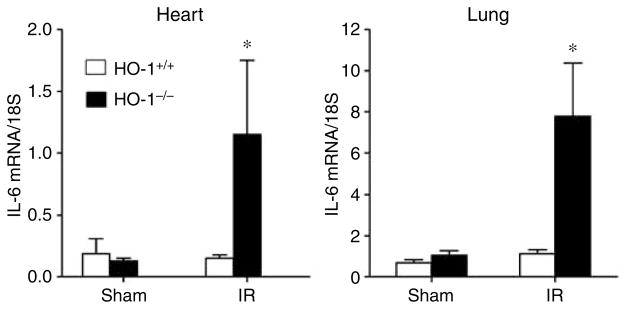

Expression of IL-6 and pSTAT3 in the lung and heart 8 h after renal ischemia–reperfusion

Since IL-6 was markedly increased in the kidney and the systemic circulation, and IL-6 predicts increased mortality in acutely ill patients,24 expression of IL-6 was assessed in vital organs such as the heart and lung. In both of these organs, IL-6 was significantly increased in HO-1−/− mice as compared to HO-1+/+ mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion with no differences observed in the sham-operated animals (Figure 9).

Figure 9. IL-6 mRNA determination by quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR in the heart and lung in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IR) or sham ischemia (Sham).

For studies in either organ, n = 4 and n = 5 in the HO-1+/+ Sham and HO-1−/− Sham groups respectively, and n = 8 and n = 7 in the HO-1+/+ IR and HO-1−/− IR groups respectively. *P< 0.05 versus HO-1+/+ mice subjected to the same condition.

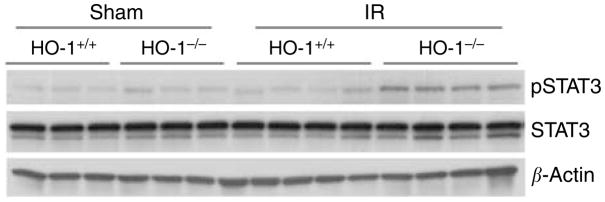

pSTAT3 was also upregulated in distant vital organs. As demonstrated in Figure 10, HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion exhibited significant upregulation in pSTAT3 in the lung as compared to similarly treated HO-1+/+ mice, whereas such upregulation was not observed in HO-1−/− or HO-1+/+ mice subjected to sham ischemia. Such differential upregulation of pSTAT3 in the lung in HO-1−/− mice after ischemia was also seen in the heart (data not shown).

Figure 10. Western analysis for pSTAT3 and STAT3 expression in the lung in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IR) or sham ischemia (Sham).

Each lane represents protein extracted from a single lung of an individual mouse, and equivalency of protein loading was verified by immunoblotting for β-actin.

Mild vascular congestion was observed in the lung and heart after ischemia–reperfusion injury as compared with sham ischemia, but these histologic changes were comparable in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice at the time point studied, namely, 8 h (data not shown).

Effect of an IL-6 antibody on the sensitivity of HO-1−/− mice to renal ischemia

Utilizing an IL-6 antibody previously shown to protect against ischemic kidney injury in wild-type mice,25 we examined whether IL-6 contributes to the sensitivity of HO-1−/− mice to such ischemia. HO-1−/− mice, subjected to ischemia, were treated either with an IL-6 antibody or an isotype immunoglobin G (IgG) control antibody (n = 13 and n = 14 respectively). The administration of an IL-6 antibody led to a BUN that was approximately 50% lower at day 1 after ischemia as compared to that observed in isotype IgG-treated, ischemic HO-1−/− mice (48±10 versus 89±17 mg/dl, P< 0.05, n = 13 and n = 11 respectively). Moreover, by day 2 after ischemia, no mortality occurred in the IL-6 antibody-treated HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia, whereas in the isotype IgG-treated HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia, four deaths occurred and one moribund animal (agonal BUN: 191 mg/dl) was killed; the administration of an IL-6 antibody thus significantly decreased mortality from 36 to 0% at day 2 following ischemia in HO-1−/− mice.

DISCUSSION

As evidenced by increased BUN and serum creatinine 24 h after ischemia, our earlier studies demonstrate that HO-1−/− mice exhibit increased sensitivity to renal ischemia. Such sensitivity occurs as early as 4 h after ischemia, as shown in our current studies and as reflected by GFR. This impairment in GFR in HO-1−/− mice was accompanied by a lower filtration fraction but was not attended by changes in RBF, renal vascular resistance, or cardiac output. This filtration defect may reflect an impairment in such determinants of GFR as the glomerular ultrafiltration coefficient or the transcapillary hydraulic pressure gradient, both of which can be altered by vasoactive species. It is possible that ischemia may differentially affect the production of vasoactive mediators in HO-1−/− mice as compared to HO-1+/+ mice, and in this regard, endothelin-1 was induced to a greater extent in the postischemic kidney in HO-1−/− mice.

Of the cytokines assessed after ischemia, marked induction of IL-6 occurred in the kidney in HO-1−/− mice. IL-6 is a critical contributor to postischemic kidney injury25,26 as shown by the following lines of evidence: IL-6−/− mice are resistant to acute ischemic renal injury;25,26 increased production of IL-6 in the ischemic kidney originates largely from macrophages, and the reconstitution of IL-6−/− mice with bone marrow from wild-type mice reduces the resistance of IL-6−/− mice to ischemic injury;26 and prior treatment with an IL-6 antibody reduces renal ischemic injury in wild-type mice.25 IL-6 may also be relevant to human acute kidney injury, since urinary excretion of IL-6 is a predictor for such injury in kidney transplant recipients.27 That IL-6 contributes to the renal dysfunction in HO-1−/− mice following ischemia, as observed in the current study, is indicated by preservation of renal function in HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemia, when these mice are pretreated with an IL-6 antibody.

IL-6 exerts its cellular effects, in part, via the pSTAT3 member of the JAK/STAT system,23,28 and in the present studies, expression of pSTAT3 mirrored the profile observed for IL-6: marked upregulation of pSTAT3 occurred in the kidney of HO-1−/− mice after ischemia but not in the other three groups. These findings are germane to recent and novel observations demonstrating the proapoptotic actions of pSTAT3 in kidney cells.29 Based on these latter findings29 and our current observations we suggest that IL-6/pSTAT3 contribute to cytoreductive pathways and renal injury in HO-1−/− mice following renal ischemia.

Our earlier studies demonstrate that the sensitivity of HO-1−/− mice to renal ischemia was accompanied by increased mortality.22 To explore the basis for such sensitivity, we assessed the expression of cytokines in the systemic circulation and in vital organs such as the heart and lung. Of the cytokines measured in serum, IL-6 was markedly and uniquely elevated in HO-1−/− mice as compared with HO-1+/+ mice following ischemia; the only other cytokine that was increased in HO-1−/− mice after ischemia was IL-12 (p40), but this latter cytokine was also increased in HO-1−/− mice as compared with HO-1+/+ mice following sham ischemia. IL-6 can induce an acute phase response and reach target organs distant from its site of production.23,28 IL-6 is one of a few cytokines that predict mortality in acutely ill patients with acute renal failure24 and in those patients with chronic kidney disease either initiated or maintained on chronic hemodialysis.30,31 Based on these considerations, in general, and our findings derived from the use of the IL-6 antibody, in particular, we suggest that the marked and unique elevation in systemic levels of IL-6 may contribute to increased mortality observed in HO-1−/− mice following renal ischemia. IL-12 (p40), a proinflammatory cytokine, was increased in HO-1−/− mice even in the absence of ischemia, and it is possible that such upregulation of IL-12 (p40) may also be germane to the observed sensitivity of HO-1−/− mice to ischemia.

In distant vital organs such as the heart and lung, IL-6 was upregulated in HO-1−/− mice subjected to renal ischemia, and was accompanied by upregulation of its downstream signaling species, pSTAT3. This raises the possibility that such upregulation of IL-6/pSTAT3 in these organs may contribute to organ dysfunction. Prior, novel studies demonstrate the adverse extrarenal effects of localized ischemic injury to the kidney.3,6,9–12 For example, renal ischemic injury increases pulmonary vascular permeability9,11 and cytokine expression in the heart, causes apoptosis of myocytes, and impairs cardiac function.10 The mechanisms incriminated in the relay of information from the ischemic kidney to these vital extrarenal organs involve cytokines including IL-6.3,6,9–12

The duration of renal ischemia employed in this study (15 min) was relatively mild, and in HO-1+/+ mice, failed to impair renal hemodynamics, to elevate serum IL-6, or to induce IL-6/pSTAT3 in the kidney and other organs. However, as recently shown, relatively mild renal ischemia can amplify the inflammatory effects of lipopolysaccharide.32 Furthermore, when cytoprotective responses are abrogated—as occurs in HO-1−/− mice—these regional and distant effects of relatively mild, localized, renal ischemia can be accentuated. Similarly, in the setting of a disease that promotes a proinflammatory and procoagulant state, such as sickle cell disease, relatively mild renal ischemia can inflict severe injury to the kidney and distant organs.33

The marked upregulation of IL-6 mRNA in the ischemic kidney and in the nonischemic heart and lung in HO-1−/− mice suggests that the inability to express HO-1 in these stressed tissues promotes the upregulation of IL-6. Renal ischemia can induce expression of HO-1 in the heart,34 and it is thus possible that the absence of expression of HO-1 in distant organs (such as the heart and lung) of HO-1−/− mice subjected to renal ischemia may underlie the upregulation of IL-6 observed in these organs. We also suggest that, as IL-6 can induce HO-1,35,36 a negative feedback loop may exist between IL-6 and HO-1 such that induction of IL-6 upregulates HO-1 which, in turn, exerts a countervailing, suppressive effect on IL-6 expression.

Kidney and other diseases occur in humans with genetic deficiency of HO-1,37,38 and polymorphisms in the HO-1 gene associated with lesser HO activity may predispose to assorted diseases.39 The exaggerated inflammatory response observed in this and earlier studies of HO-1−/− mice subjected to ischemic and nephrotoxic insults40–43 raises the possibility that inflammatory processes may contribute to morbidity and mortality in acutely ill patients in whom HO-1 is deficient or inadequately expressed.

In summary, we demonstrate that within hours of relatively mild renal ischemia, an HO-1-deficient state exhibits increased renal dysfunction accompanied by increased IL-6/pSTAT3 in the kidney and distant vital organs, and markedly increased systemic levels of IL-6. Based on studies utilizing an IL-6 antibody, we suggest that the regional, systemic, and distant upregulation of IL-6 contributes to the adverse renal and extrarenal responses to acute renal ischemia observed in an HO-1-deficient state.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Murine HO-1−/− model

Homozygous HO-1 null mutant mice, employed in this and earlier studies by our laboratory22,40,42, were generated by targeted disruption of the HO-1 gene as described by Poss and Tonegawa.44 Colonies of mice were maintained by breeding HO-1−/− males with HO-1+/− females. Offspring were genotyped at the time of weaning by using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify the wild-type and mutant alleles of genomic DNA from tail samples. HO-1+/+ mice were used as controls. For all experiments, HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice were age-matched and sex-matched, and mice from 9 to 12 weeks were utilized in studies involving renal and cardiac hemodynamics, and in all studies of cytokine expression in tissues and serum. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mayo Clinic.

Murine model of acute renal ischemia

This model was performed as described in detail by our earlier studies.22,33 A midline abdominal incision was made and the renal pedicles were dissected. Fifteen minutes of bilateral renal ischemia were induced with non-traumatic clamps (RS5426, Micro Aneurysm clip, straight, 10 mm, 125 g pressure; Roboz Surgical Instruments, Rockville, MD, USA). Sham procedures included the abdominal incision but excluded renal pedicle dissection and clamping.

Renal hemodynamic studies in mice

These studies were performed as described in detail in our earlier studies.45 Mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg body weight, intraperitoneally) and placed on a temperature-regulated table to maintain body temperature at 37°C. Evaluation of MAP, RBF, and GFR were commenced after exactly 4 h of reperfusion. During these studies, a solution of 0.9% saline containing 2.25% of bovine serum albumin and 0.75% of FITC-inulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was infused, and GFR was determined by the clearance of inulin.46 RBF was determined by an electromagnetic flow probe (Transonic Systems Inc., Ithaca, NY, USA) and a small animal blood flow meter (T206, Transonic Systems Inc.).47 Renal vascular resistances were calculated as the ratio of MAP/RBF. Renal plasma flow (RPF) was determined by RBF(100–hematocrit)/100. Filtration fraction was calculated as GFR/RPF.

Assessment of cardiac function after renal ischemia

This methodology is described in detail by our earlier studies.48,49 Echocardiography (c256 and 15L8, Acuson, Mountain View, CA, USA) was performed in lightly sedated mice 4 h after renal ischemia or sham ischemia in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice. Images were digitally acquired and stored for off-line blinded analysis. Echocardiographic measurements of left ventricular dimensions were recorded at end-diastole (EDD) and end-systole (ESD) from three consecutive cardiac cycles using the leading edge method. Left ventricular fractional shortening (%FS) was calculated as: %FS = [(EDD − ESD)/EDD]100. Ejection time (Et) was determined from the actual pulsed-wave Doppler tracings on the parasternal long-axis view of trans-aortic flow by measuring the interval from the beginning of the acceleration to the end of the deceleration. The myocardial velocity of left ventricular circumferential shortening (Vcf expressed in circumferences per second) was calculated as: Vcf = [(EDD − ESD)/EDD]/Et. Stroke volume was determined by the sum of aortic root cross-sectional area and the velocity time integral, taken from peak left ventricular outflow tract Doppler tracings. The product of stroke volume and heart rate, expressed as ml/min, was used to calculate cardiac output and corrected for body weight.

Western analysis

Western analysis was carried out on proteins extracted from mouse tissues as described previously.22 Briefly, lysate proteins (20–100 μg) were separated on 10% Tris-HCl gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Blots were incubated with primary antibodies to pSTAT3 and STAT3 (catalog numbers 9138 and 4904, respectively; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), HO-1 (catalog number SPA-895; StressGen, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), and β-actin (catalog number 612657; BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C. This was followed by incubation with goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies and visualization using a chemiluminescence method (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Equal protein loading was confirmed by Ponceau staining for HO-1 or immunoblotting against β-actin for pSTAT3.

mRNA expression by quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR

For analysis of gene expression, total RNA was extracted from mouse tissues using the TRIzol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and further purified with an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), according to each manufacturer’s protocol. One hundred nanograms of purified total RNA were subsequently used in 20 μl reverse transcription reactions (Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) employing random hexamers. The resulting cDNA was used in quantitative real-time PCR analysis as in our earlier study.22 Reactions were performed on an ABI Prism 7900HT (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using TaqMan Mastermix reagents (part number 4309169, Applied Biosystems) with primer and probe concentrations of 300 nmol/l and 200 nmol/l, respectively. Parameters for quantitative PCR were as follows: 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of amplification for 15 s at 95°C, and 1 min at 60°C. Probe and primer sets employed for quantification were designed with Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems) and are detailed in Table 3. Additionally, a probe and primer set for the analysis of ET-1 gene expression was obtained from Applied Biosystems (TaqMan Gene Expression Assay, stock number Mm00438656) and was utilized in quantitative real-time PCR reactions with cycling parameters outlined above.

Table 3.

Primers and probes used for quantitative real-time RT-PCR

| cc | Primer/Probe | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| HO-1 | Forward | 5′-CTGCTAGCCTGGTGCAAGATACT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTCTGGGATGAGCTAGTGCTGAT-3′ | |

| TaqMan | 5′-(FAM)-AGACACCCCGAGGGAAACCCCA (TAMRA)-3′ | |

| IL-6 | Forward | 5′-CCAGAAACCGCTATGAAGTTCCT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CACCAGCATCAGTCCCAAGA-3′ | |

| TaqMan | 5′-(FAM)TCTGCAAGAGACTTCCATCCAGTTGCC (TAMRA)-3′ | |

| IL-10 | Forward | 5′-AGCAGCCTTGCAGAAAAGAGA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AGTAAGAGCAGGCAGCATAGCA-3′ | |

| TaqMan | 5′-(FAM)-CCATCATGCCTGGCTCAGCA (TAMRA)-3′ | |

| MCP-1 | Forward | 5′-GGCTCAGCCAGATGCAGTTAA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCTACTCATTGGGATCATCTTGCT-3′ | |

| TaqMan | 5′-(FAM)-CCCCACTCACCTGCTGCTACTCATTCAC (TAMRA)-3′ | |

| TNF | Forward | 5′-TCTCTTCAAGGGACAAGGCTG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-ATAGCAAATCGGCTGACGGT-3′ | |

| TaqMan | 5′-(FAM)-CCCGACTACGTGCTCCTCACCCA (TAMRA)-3′ | |

| 18S | Forward | 5′-TGTCTCAAAGATTAAGCCATGCAT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AACCATAACTGATTTAATGAGCCATTC-3′ | |

| TaqMan | 5′-(FAM) TACGCACGGCCGGTACAGTGAAACT (TAMRA)-3′ |

HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; IL, interleukin; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Serum protein array assay

This array determined the serum levels of the following cytokines: interferon-γ, TNF, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-17, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor, keratinocyte-derived chemokine, regulated on activation normal T-cell expressed and secreted, IL-13, Eotaxin, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1β. Serum samples were collected using BD Microtainer serum separators (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and concentrations of cytokines were determined employing a multiplex bead suspension array (23-Plex Mouse Cytokine Panel, catalog number 171-F11241, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) performed on a Bio-Plex Suspension Array System (Bio-Rad, catalog number 171-000001); this was performed as described in the manufacturer’s protocol contained in the Bio-Rad publication number 4110004.

Effect of an IL-6 antibody on the sensitivity of HO-1−/− mice to renal ischemia

To determine the role of IL-6 in the sensitivity of HO-1−/− mice to ischemia, a neutralizing monoclonal rat anti-mouse IL-6 antibody (catalog number AMC0862, Biosource International, Camarillo, CA, USA) or an IgG1 isotype control was administered to HO-1−/− mice (10 μg/day, intraperitoneally) at 24 h and 1 h before, and 24 h after renal ischemia (15 min bilateral renal ischemia, as described above); these studies were performed in 40-week-old male HO-1−/− mice. For these studies, renal function was assessed by the measurement of BUN levels at 24 h after ischemia using a BUN Analyzer 2 (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. Data for HO-1−/− and HO-1+/+ mice for a given condition were compared using Student’s t-test for parametric data, and the Mann–Whitney test for nonparametric data. Results were considered significant for P< 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We greatly acknowledge the secretarial expertise of Mrs Sharon Heppelmann in the preparation of this work and the following NIH grants for support: DK47060 (KAN), HL 64822 (AT), and DK68545 (MDG).

References

- 1.Rabb H, O’Meara YM, Maderna P, et al. Leukocytes, cell adhesion molecules and ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1463–1468. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutton TA, Fisher CJ, Molitoris BA. Microvascular endothelial injury and dysfunction during ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1539–1549. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kielar ML, Rohan Jeyarajah D, Lu CY. The regulation of ischemic acute renal failure by extrarenal organs. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2002;11:451–457. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200207000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burne-Taney MJ, Rabb H. The role of adhesion molecules and T cells in ischemic renal injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2003;12:85–90. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200301000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonventre JV, Weinberg JM. Recent advances in the pathophysiology of ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2199–2210. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000079785.13922.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly KJ. Acute renal failure: much more than a kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 2006;26:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng J, Kohda Y, Chiao H, et al. Interleukin-10 inhibits ischemic and cisplatin-induced acute renal injury. Kidney Int. 2001;60:2118–2128. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, Okusa MD. Blocking the immune response in ischemic acute kidney injury: the role of adenosine 2A agonists. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:432–444. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer AA, Postler G, Salhab KF, et al. Renal ischemia/reperfusion leads to macrophage-mediated increase in pulmonary vascular permeability. Kidney Int. 1999;55:2362–2367. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly KJ. Distant effects of experimental renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1549–1558. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000064946.94590.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabb H, Wang Z, Nemoto T, et al. Acute renal failure leads to dysregulation of lung salt and water channels. Kidney Int. 2003;63:600–606. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonventre JV. Pathophysiology of ischemic acute renal failure. Inflammation, lung-kidney cross-talk, and biomarkers. Contrib Nephrol. 2004;144:19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal A, Nick HS. Renal response to tissue injury: lessons from heme oxygenase-1 GeneAblation and expression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:965–973. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V115965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanwar YS. Heme oxygenase-1 in renal injury: conclusions of studies in humans and animal models. Kidney Int. 2001;59:378–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sikorski EM, Hock T, Hill-Kapturczak N, et al. The story so far: molecular regulation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F425–F441. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00297.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abraham NG, Kappas A. Heme oxygenase and the cardiovascular–renal system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanwar YS. A dynamic interplay between monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and heme oxygenase-1: implications in renal injury. Kidney Int. 2005;68:896–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nath KA. Heme oxygenase-1: a provenance for cytoprotective pathways in the kidney and other tissues. Kidney Int. 2006;70:432–443. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nath KA, Balla G, Vercellotti GM, et al. Induction of heme oxygenase is a rapid, protective response in rhabdomyolysis in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:267–270. doi: 10.1172/JCI115847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaizu T, Tamaki T, Tanaka M, et al. Preconditioning with tin-protoporphyrin IX attenuates ischemia/reperfusion injury in the rat kidney. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1393–1403. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimizu H, Takahashi T, Suzuki T, et al. Protective effect of heme oxygenase induction in ischemic acute renal failure. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:809–817. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200003000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pittock ST, Norby SM, Grande JP, et al. MCP-1 is up-regulated in unstressed and stressed HO-1 knockout mice: pathophysiologic correlates. Kidney Int. 2005;68:611–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song M, Kellum JA. Interleukin-6. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:S463–S465. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186784.62662.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simmons EM, Himmelfarb J, Sezer MT, et al. Plasma cytokine levels predict mortality in patients with acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1357–1365. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel NS, Chatterjee PK, Di Paola R, et al. Endogenous interleukin-6 enhances the renal injury, dysfunction, and inflammation caused by ischemia/reperfusion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:1170–1178. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kielar ML, John R, Bennett M, et al. Maladaptive role of IL-6 in ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3315–3325. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2003090757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon O, Molitoris BA, Pescovitz M, et al. Urinary actin, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 may predict sustained ARF after ischemic injury in renal allografts. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:1074–1087. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stenvinkel P, Ketteler M, Johnson RJ, et al. IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-alpha: central factors in the altered cytokine network of uremia — the good, the bad, and the ugly. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1216–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arany I, Megyesi JK, Nelkin BD, et al. STAT3 attenuates EGFR-mediated ERK activation and cell survival during oxidant stress in mouse proximal tubular cells. Kidney Int. 2006;70:669–674. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bologa RM, Levine DM, Parker TS, et al. Interleukin-6 predicts hypoalbuminemia, hypocholesterolemia, and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:107–114. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9669431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pecoits-Filho R, Barany P, Lindholm B, et al. Interleukin-6 is an independent predictor of mortality in patients starting dialysis treatment. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1684–1688. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.9.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Hanson SY, et al. Ischemic proximal tubular injury primes mice to endotoxin-induced TNF-alpha generation and systemic release. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F289–F297. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00023.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nath KA, Grande JP, Croatt AJ, et al. Transgenic sickle mice are markedly sensitive to renal ischemia–reperfusion injury. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:963–972. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62318-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raju VS, Maines MD. Renal ischemia/reperfusion up-regulates heme oxygenase-1 (HSP32) expression and increases cGMP in rat heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:1814–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ricchetti GA, Williams LM, Foxwell BM. Heme oxygenase 1 expression induced by IL-10 requires STAT-3 and phosphoinositol-3 kinase and is inhibited by lipopolysaccharide. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:719–726. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0104046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tron K, Samoylenko A, Musikowski G, et al. Regulation of rat heme oxygenase-1 expression by interleukin-6 via the Jak/STAT pathway in hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 2006;45:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yachie A, Niida Y, Wada T, et al. Oxidative stress causes enhanced endothelial cell injury in human heme oxygenase-1 deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:129–135. doi: 10.1172/JCI4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohta K, Yachie A, Fujimoto K, et al. Tubular injury as a cardinal pathologic feature in human heme oxygenase-1 deficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:863–870. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Exner M, Minar E, Wagner O, et al. The role of heme oxygenase-1 promoter polymorphisms in human disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1097–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nath KA, Haggard JJ, Croatt AJ, et al. The indispensability of heme oxygenase-1 in protecting against acute heme protein-induced toxicity in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1527–1535. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65024-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiraishi F, Curtis LM, Truong L, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 gene ablation or expression modulates cisplatin-induced renal tubular apoptosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278:F726–F736. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.5.F726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nath KA, Vercellotti GM, Grande JP, et al. Heme protein-induced chronic renal inflammation: suppressive effect of induced heme oxygenase-1. Kidney Int. 2001;59:106–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kapturczak MH, Wasserfall C, Brusko T, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 modulates early inflammatory responses: evidence from the heme oxygenase-1-deficient mouse. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63365-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poss KD, Tonegawa S. Heme oxygenase 1 is required for mammalian iron reutilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10919–10924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Juncos JP, Grande JP, Murali N, et al. Anomalous renal effects of tin protoporphyrin in a murine model of sickle cell disease. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:21–31. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lorenz JN, Gruenstein E. A simple, nonradioactive method for evaluating single-nephron filtration rate using FITC-inulin. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F172–F177. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.1.F172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Traynor TR, Schnermann J. Renin–angiotensin system dependence of renal hemodynamics in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(Suppl 11):S184–S188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kane GC, Behfar A, Dyer RB, et al. KCNJ11 gene knockout of the Kir6.2 KATP channel causes maladaptive remodeling and heart failure in hypertension. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2285–2297. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kane GC, Behfar A, Yamada S, et al. ATP-sensitive K+ channel knockout compromises the metabolic benefit of exercise training, resulting in cardiac deficits. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 3):S169–S175. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]