A new “green revolution” is needed in world agriculture to increase crop yields for food and bioenergy, because gains from conventional crop improvement (Fischer and Edmeades, 2010) are less than world population growth. Efforts to increase crop productivity must also consider global change. Increasing leaf photosynthesis provides one attractive avenue to drive increases in crop yields (Long et al., 2006; Parry et al., 2007; Hibberd et al., 2008; Peterhansel et al., 2008; Murchie et al., 2009; Reynolds et al., 2009). It is timely to consider what new opportunities exist in the current “omics” era to engineer increases in photosynthesis.

THE DEBATE: CAN ENHANCING LEAF PHOTOSYNTHESIS INCREASE YIELD POTENTIAL?

There has been an ongoing debate whether enhancing leaf photosynthesis can raise yield potential (as defined by Fischer and Edmeades, 2010) given the many steps between leaf photosynthesis and final yield. Poor correlations between leaf photosynthetic rates and crop yields (often comparing lines that differ genetically in many respects), together with suggestions that the crop is sink and not photosynthesis limited, have led to the view that improving photosynthesis is unlikely to increase yield (Sinclair et al., 2004). However, two lines of evidence contradict this. First, free-air CO2 enrichment studies have shown that CO2-induced increases in leaf photosynthesis generally lead to increased crop yield. Second, C4 plants have greater rates of photosynthesis and produce more biomass per unit of intercepted sunlight than C3 plants (Sheehy et al., 2007). Long et al. (2006) provide an excellent debate of these issues. The potential benefit from introducing dwarfing genes for the green revolution took additional breeding and selection to increase the fraction of biomass in grain. A similar concerted effort will be needed to capture enhanced photosynthesis in increased growth.

IMPROVING C3 PHOTOSYNTHESIS

CO2 Diffusion: Stomata, Membrane Permeabilities, and Leaf Anatomy

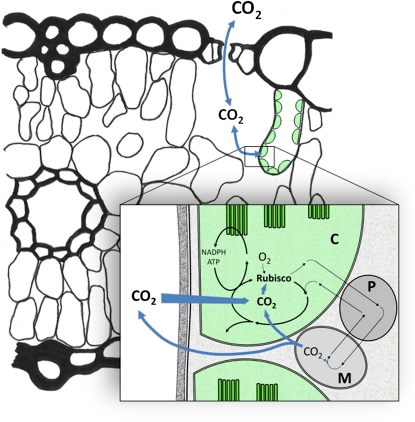

Rubisco is the primary CO2-fixing enzyme, and its kinetic properties shape C3 photosynthesis (Farquhar et al., 1980). Rubisco is a slow catalyst for both carboxylase and oxygenase reactions. To reach Rubisco, CO2 has to diffuse through stomata and then through the liquid phase to the chloroplast stroma (Fig. 1). Under high irradiance, the drawdown in CO2 concentration associated with stomatal conductance is similar to that in the liquid phase (mesophyll conductance). Stomatal aperture varies in response to environmental and plant signals, regulating CO2 uptake and water loss. We can predict how stomata respond to these signals based on gas-exchange measurements. While complex descriptions of both regulatory and developmental pathways have come from studying numerous mutants (Casson and Hetherington, 2010), we still do not know if and how stomatal function and photosynthetic capacity are coordinated. Transgenic reductions in photosynthetic rate are independent of stomatal conductance (Baroli et al., 2008), so it should be possible to enhance photosynthesis without altering stomatal function (and increase water use efficiency) or enhance photosynthesis by increasing stomatal conductance if water is not limiting. Furthermore, the consequences on daily photosynthesis of altering the dynamic behavior of stomata in fluctuating conditions should be explored.

Figure 1.

Leaf cross section showing the diffusion path for CO2 and the linkage between the light reactions, carbon reduction, and photorespiratory cycles. C, Chloroplast; M, mitochondrion; P, peroxisome.

To enhance CO2 diffusion, chloroplasts are spread thinly along cell wall surfaces, and their surface area appressing intercellular air space is up to 25 times leaf surface area. The cell wall and membranes are the key elements limiting CO2 permeability (Evans et al., 2009). There seems little scope for changing cell walls to increase mesophyll conductance. On the other hand, manipulating aquaporins may alter membrane permeability to CO2 (Uehlein et al., 2008). This needs confirmation, because at present membrane permeabilities measured in vitro are 2 orders of magnitude below what is needed to support observed rates of CO2 assimilation. However, it opens up the possibility of manipulating mesophyll conductance. In most cases, it would be beneficial to increase mesophyll conductance to increase the CO2 concentration at Rubisco. Alternatively, a CO2-concentrating mechanism at the chloroplast would require a reduction to chloroplast envelope permeability to minimize leakage (von Caemmerer, 2003).

Improving Rubisco’s Performance

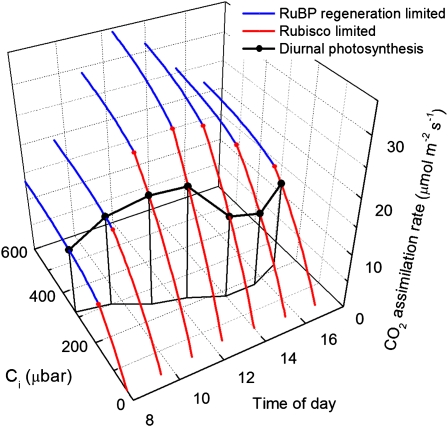

Modification of Rubisco to increase specificity for CO2 relative to oxygen would decrease photorespiration and increase photosynthesis when ribulose 1,5-bisP (RuBP) regeneration is limiting (Fig. 2, blue lines). Increasing catalytic turnover rate would increase the amount of CO2 fixed per Rubisco protein. The prospects and current challenges for improving Rubisco and its helper enzyme Rubisco activase have been reviewed in detail (Parry et al., 2007; Peterhansel et al., 2008). Naturally occurring Rubiscos with better specificity have been found among the red algae, and Rubiscos from C4 species have superior catalytic turnover rates. Crop models predict that substantial increases in canopy photosynthesis could follow from incorporating a “better Rubisco” into C3 crop species (Long et al., 2006).

Figure 2.

Illustration of leaf-level responses of CO2 assimilation rate to intercellular CO2 (Ci) with diurnal variation in temperature and irradiance, which both peak at midday. CO2 assimilation rate is Rubisco limited at low Ci (red lines), and RuBP regeneration is limited at high Ci (blue lines). A hypothetical diurnal path of leaf CO2 assimilation rate and the corresponding Ci are shown in black. The impact of changing Rubisco or RuBP regeneration capacity depends on irradiance, temperature, stomatal conductance, and leaf orientation.

Higher plant Rubisco is a hexadecamer composed of eight chloroplast-encoded large subunits and eight nucleus-encoded small subunits. The inability to assemble Rubisco from any photosynthetic eukaryote within Escherichia coli has hampered structure-function studies of higher plant Rubisco. Progress is being made in understanding chaperoning action in the folding and assembly of hexadecameric Rubisco (Liu et al., 2010). Although crystal structures of Rubisco are available, the possibility of improving the kinetic properties of Rubisco by rational design remains a goal for the future. Meanwhile, directed evolution in E. coli dependent on Rubisco activity is being used to generate novel Rubiscos (Mueller-Cajar and Whitney, 2008). To manipulate Rubisco within higher plants, chloroplast transformation systems need to be developed in more species. The creation of a master line of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) expressing Rubisco from Rhodosprillum rubrum facilitates rapid transformation of tobacco with altered Rubisco (Whitney and Sharwood, 2008).

Photorespiration

The oxygenase reaction of Rubisco produces phosphoglycolate that is metabolized by the photorespiratory pathway. Alternative photorespiratory pathways have been engineered that convert phosphoglycolate and release CO2 either within the chloroplast or the cytosol, resulting in plants with enhanced growth (Peterhansel et al., 2008; Maurino and Peterhansel, 2010). Enhanced growth may be due to a reduced NADPH requirement, but reduced compensation points indicate that chloroplast CO2 was also elevated. This fits with the observations by Uehlein et al. (2008) that the chloroplast envelope is less permeable to CO2 than the plasma membrane and that photorespiratory and respiratory CO2 bypass the chloroplast (Fig. 1). Confocal microscopy may help study the impact of mitochondrial location on the CO2 diffusion path.

CO2-Concentrating Mechanisms

Mechanisms that concentrate CO2 at Rubisco to increase catalytic turnover rate have evolved in cyanobacterial, algal, and higher plant species. Introducing CO2-concentrating mechanisms into C3 species could enhance photosynthesis (Hibberd et al., 2008; Peterhansel et al., 2008). The C4 photosynthetic pathway in higher plants uses phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase in mesophyll cells to pump CO2 into bundle sheath cells for Rubisco. It is intriguing that the C4 pathway has evolved independently many times utilizing diverse anatomical and biochemical modifications. Parallel sequencing of related C3 and C4 species may enable identification of genes involved in the evolution of this photosynthetic pathway. Species with a single-cell C4 photosynthetic pathway have been discovered, and characterization of these pathways may help efforts to install a CO2 pump (Smith et al., 2009) or cyanobacterial bicarbonate transporters (Price et al., 2008) into the chloroplast envelope.

RuBP Regeneration and Light Reactions

Under conditions of high CO2 or low irradiance, the rate of CO2 assimilation is limited by the rate of RuBP regeneration, which in turn can be limited by chloroplast electron transport capacity or by the enzymes involved in the regeneration of RuBP (Fig. 2). These enzymes interact with electron transport and are redox regulated. Several enzymes have been identified, and overexpression of sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase increased both photosynthetic rate and growth. This single gene manipulation should be tested in crop species under field conditions. The saturation characteristics of overexpression of these enzymes need to be studied, because gains from increasing Calvin cycle activity by more than a small amount may be thwarted by other electron transport limitations (for review, see Raines, 2006; Peterhansel et al., 2008). A modeling approach using an evolutionary algorithm predicted that optimizing the distribution of resources between enzymes of the Calvin cycle can dramatically increase photosynthetic rates (Zhu et al., 2007). These in silico approaches provide new ideas of how carbon metabolism can be manipulated to enhance photosynthesis.

The capture and conversion of light into chemical energy is the start of photosynthesis. At low irradiance, the quantum yield of the system (on an absorbed light basis) is similar for all nonstressed C3 leaves. At high irradiance, electron transport rates reach a maximum, which correlates with cytochrome b6f and ATPase contents. It was possible to increase electron transport in Arabidopsis through the expression of Porphyra cytochrome c6, introducing a parallel electron carrier between cytochrome f and PSI (see Peterhansel et al., 2008). ATPase regulation provides feedback control between carbon metabolism and light reactions (Kiirats et al., 2009). In a future high-CO2 world, C3 photosynthesis will be increasingly limited by RuBP regeneration, and research is needed to explore how greater amounts of cytochrome b6f and ATPase complexes can be assembled, given that they contain both nucleus- and chloroplast-encoded subunits.

When light exceeds that used in photochemistry, photoprotection is activated to prevent damage. Decreasing the time it takes for photoprotection to relax could increase photosynthesis in fluctuating light (Murchie et al., 2009). Light saturation is less important for plant communities than single leaves because light is distributed between them. However, decreasing chlorophyll content would spread the light further and could increase crop solar conversion efficiency.

NEW APPROACHES IN SYSTEMS BIOLOGY AND MATHEMATICAL MODELING

The conceptual simplification of photosynthesis focusing on the kinetic properties of Rubisco in the model of Farquhar et al. (1980) has proved tremendously powerful in guiding our understanding of how CO2 assimilation is linked to the underlying biochemistry of C3 photosynthesis (Fig. 2). Different approaches harnessing the masses of information emerging from transcriptomics, metabolomics, and fluxomics to construct system models have been heralded (de Oliveira Dal’Molin et al., 2010; Stitt et al., 2010). Crop-modeling approaches are needed that test predictions coming from new systems approaches in silico. The complex web of control means that few single-gene changes will improve photosynthesis. It will be necessary to pyramid a coordinated series of changes to increase photosynthesis with another series of changes to convert this through to crop yield (Sinclair et al., 2004; Long et al., 2006). An example is the C4 rice (Oryza sativa) project (Hibberd et al., 2008), which hopes to translate changes to photosynthesis into improved crop yield through a concerted team effort spanning many disciplines and taking 10 to 20 years.

We have focused on the biochemistry of the leaf. Understanding photosynthesis, its development, regulation, and coordination with stomatal and hydraulic capacity provide new opportunities for enhancing leaf photosynthesis. The next challenge is to translate it into increased growth.

References

- Baroli I, Price GD, Badger MR, von Caemmerer S. (2008) The contribution of photosynthesis to the red light response of stomatal conductance. Plant Physiol 146: 737–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casson SA, Hetherington AM. (2010) Environmental regulation of stomatal development. Curr Opin Plant Biol 13: 90–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Dal’Molin CG, Quek LE, Palfreyman RW, Brumbley SM, Nielsen LK. (2010) AraGEM, a genome-scale reconstruction of the primary metabolic network in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 152: 579–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Kaldenhoff R, Genty B, Terashima I. (2009) Resistances along the CO2 diffusion pathway inside leaves. J Exp Bot 60: 2235–2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA. (1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149: 78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer RA, Edmeades GO. (2010) Breeding and cereal yield progress. Crop Sci 50: S85–S98 [Google Scholar]

- Hibberd JM, Sheehy JE, Langdale JA. (2008) Using C4 photosynthesis to increase the yield of rice: rationale and feasibility. Curr Opin Plant Biol 11: 228–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiirats O, Cruz JA, Edwards GE, Kramer DM. (2009) Feedback limitation of photosynthesis at high CO2 acts by modulating the activity of the chloroplast ATP synthase. Funct Plant Biol 36: 893–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Young AL, Starling-Windhof A, Bracher A, Saschenbrecker S, Rao BV, Rao KV, Berninghausen O, Mielke T, Hartl FU, et al. (2010) Coupled chaperone action in folding and assembly of hexadecameric Rubisco. Nature 463: 197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Zhu XG, Naidu SL, Ort DR. (2006) Can improvement in photosynthesis increase crop yields? Plant Cell Environ 29: 315–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurino VG, Peterhansel C. (2010) Photorespiration: current status and approaches for metabolic engineering. Curr Opin Plant Biol 13: 249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller-Cajar O, Whitney SM. (2008) Directing the evolution of Rubisco and Rubisco activase: first impressions of a new tool for photosynthesis research. Photosynth Res 98: 667–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchie EH, Pinto M, Horton P. (2009) Agriculture and the new challenges for photosynthesis research. New Phytol 181: 532–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry MAJ, Madgwick PJ, Carvalho JFC, Andralojc PJ. (2007) Prospects for increasing photosynthesis by overcoming the limitations of Rubisco. J Agric Sci 145: 31–43 [Google Scholar]

- Peterhansel C, Niessen M, Kebeish R. (2008) Metabolic engineering towards the enhancement of photosynthesis. Photochem Photobiol 84: 1317–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Badger MR, Woodger FJ, Long BM. (2008) Advances in understanding the cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating-mechanism (CCM): functional components, Ci transporters, diversity, genetic regulation and prospects for engineering into plants. J Exp Bot 59: 1441–1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raines CA. (2006) Transgenic approaches to manipulate the environmental responses of the C3 carbon fixation cycle. Plant Cell Environ 29: 331–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M, Foulkes MJ, Slafer GA, Berry P, Parry MAJ, Snape JW, Angus WJ. (2009) Raising yield potential in wheat. J Exp Bot 60: 1899–1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehy JE, Ferrer AB, Mitchell PL, Elmido-Mabilangan A, Pablico P, Dionora MJA. (2007) How the rice crop works and why it needs a new engine. Sheehy JE, Mitchell PL, Hardy B, , Charting New Pathways to C4 Rice. International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Philippines, pp 3–26 [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair TR, Purcell LC, Sneller CH. (2004) Crop transformation and the challenge to increase yield potential. Trends Plant Sci 9: 70–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ME, Koteyeva NK, Voznesenskaya EV, Okita TW, Edwards GE. (2009) Photosynthetic features of non-Kranz type C-4 versus Kranz type C-4 and C-3 species in subfamily Suaedoideae (Chenopodiaceae). Funct Plant Biol 36: 770–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Sulpice R, Keurentjes J. (2010) Metabolic networks: how to identify key components in the regulation of metabolism and growth. Plant Physiol 152: 428–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehlein N, Otto B, Hanson DT, Fischer M, McDowell N, Kaldenhoff R. (2008) Function of Nicotiana tabacum aquaporins as chloroplast gas pores challenges the concept of membrane CO2 permeability. Plant Cell 20: 648–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S. (2003) C4 photosynthesis in a single C3 cell is theoretically inefficient but may ameliorate internal CO2 diffusion limitations of C3 leaves. Plant Cell Environ 26: 1191–1197 [Google Scholar]

- Whitney SM, Sharwood RE. (2008) Construction of a tobacco master line to improve Rubisco engineering in chloroplasts. J Exp Bot 59: 1909–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, de Sturler E, Long SP. (2007) Optimizing the distribution of resources between enzymes of carbon metabolism can dramatically increase photosynthetic rate: a numerical simulation using an evolutionary algorithm. Plant Physiol 145: 513–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]