Abstract

Purpose

Prior practical experience in conducting ACA surveys has demonstrated that many subjects have difficulty understanding the “importance” questions. The objective of this study was to develop a modified version of ACA’s importance questions.

Methods

Modified ACA importance questions composed of two tasks were developed and tested in a pilot study of patients with knee pain. In the first, respondents were presented with the list of attributes and asked to choose which they consider to be the most important. In the second, they were asked to rate the importance of the remaining attributes relative to the most important one on an 11-point numeric rating scale. Consecutive patients, followed at a hospital-based Bone and Joint Clinic with knee pain, were randomized to complete the original or modified version of the ACA survey. The two versions were identical except for the importance questions. The ACA survey included six attributes: pain, energy, route of administration, stomach upset, bleeding ulcer and cost. Each attribute contained three levels, all of which had a natural order except for route of administration. As this was a pilot study, we present descriptive statistics only.

Results

49 patients were recruited; 24 completed the original version and 25 completed the modified version. Subjects felt that bar graphs illustrating the relative importances were more accurate for the modified version of ACA. The proportion of subjects for which the most important attribute chosen on a card sorting task matched that generated by ACA was greater for the modified compare to original version (48% vs 29%). The proportion of subjects for which the treatment option chosen on a card sorting task matched that predicted by ACA was also greater for the modified compare to original version (80% versus 75%). Subjects used a greater number of points to rate the importance of attributes on the modified version of ACA (3.4 ± 0.9) compared to the original version (2.7 ± 1.0).

Conclusions

The modified version of the ACA importance questions appears to perform as well or better then the original version. Use of a simplified set of ACA importance questions is a reasonable alternative for investigators interested in using ACA as a decision support tool in clinical practice.

Conjoint analysis (CA) is an extremely valuable tool to elicit patient preferences for healthcare-related decisions. It has a strong theoretical basis, obtains high levels of internal consistency, is able to predict future choices, and works in real world settings (1, 2). Several forms of CA are commonly used in both research and applied settings, including traditional profile, adaptive conjoint analysis (ACA, Sawtooth Software ®), and discrete choice or choice-based CA (CBC). The latter, is currently the most widely used form of CA, however, ACA has unique features which make it particularly valuable for eliciting preferences in certain healthcare settings. For example, unlike CBC, ACA is able to handle a large number of attributes. This feature is extremely important when using CA to help patients consider trade-offs between complicated treatment options with multiple risks and benefits. In addition, ACA is able to provide accurate estimates of individual respondent’s relative importances and preferences in real time, which is essential if using CA to improve decision making in clinical settings.

ACA includes three sets of questions and an optional fourth set of calibration concepts (for further discussion regarding the latter please see (3)). In the first set, respondents are asked to rank the levels for each attribute in order to determine the rank order of the levels that do not have “a priori” (or natural) ranking. “A priori” ranking refers to attributes where there is an obvious preference from one level to the next, such as a risk of an adverse event. An example of an attribute which does not have a prior ranking would be route of administration for arthritis medications which could include topical agents, pills, as well as intra-articular injections.

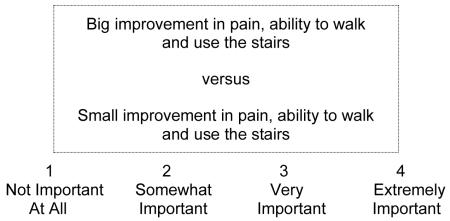

In the second set of questions, ACA asks respondents to rate the importance between the highest and lowest levels of each attribute on a Likert-type scale. For example:

“If a treatment was acceptable in all other ways, how important would the difference be?”

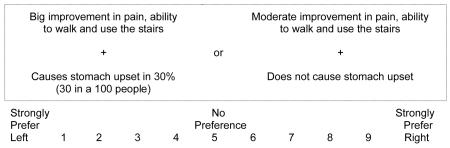

Lastly, ACA presents respondents with a series of paired-comparison tasks. For example:

The paired-comparison questions are based on the subject’s answers to the first two sets of questions (3). ACA is interactive, in that it uses the information obtained from each new paired comparison to update utility estimates and to select the next pair of options. Utility measures become more precise as subjects are asked to discriminate among competing risks and benefits in successive pairs. The software continues presenting the subject with paired comparisons until enough data have been collected to estimate utilities for each level of each characteristic.

While the first and the third set of questions are fairly straightforward, prior practical experience in conducting ACA surveys has demonstrated that many patients have difficulty understanding the second set of questions which are hereafter referred to as the “importance” questions (4). The importance questions are meant to generate respondents’ opinions for how important each attribute is relative to the others, given their specified range. Problems arise from 1) the difficulty patients have incorporating the range in levels into their ratings, 2) the difficulty of making relative judgments for each attribute, especially if respondents are not able to see all the attributes on a single screen, and 3) as with other rating tasks, the tendency to overuse the extremes of the scale.

One option to deal with this difficulty is to simply delete the set of importance questions from the ACA survey. Empirical research has shown that, when the importance questions are omitted from the survey, hit rates are equivalent, shared prediction accuracy is improved, and the length of the survey is shortened (4). However, this is only true if the data are analyzed using Hierarchical Bayes models (5). Therefore, this approach cannot be used for investigators requiring output in real time. The objective of this study was to determine whether a simpler set of ACA importance questions could be developed for investigators requiring individual respondent data in real time.

METHODS

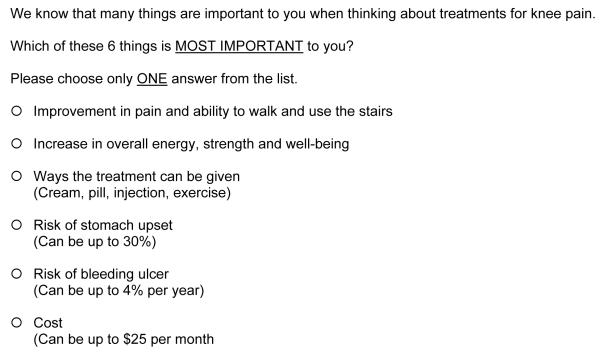

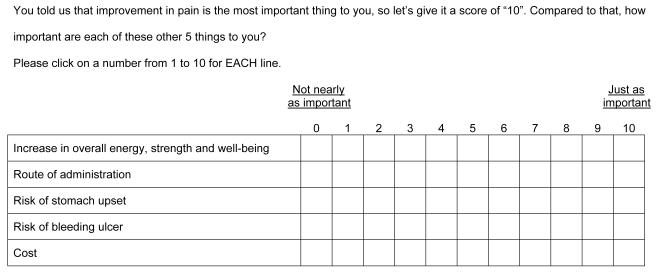

We developed, in collaboration with Sawtooth Software ®, a modified version of ACA importance questions and tested the performance of these questions in a pilot study of patients with knee pain. Two questions were developed by the author and programmers at Sawtooth Software® and subsequently modified based on repeated cycles of feedback from providers and patients with varied levels of education. In the first question, subjects are presented with a list of all the attributes included in the survey and asked to choose the one that is most important to them (Figure 1). In the second, subjects are asked to rate the importance of the remaining attributes on a grid relative to the one chosen as most important using a numeric rating scale ranging from “Not nearly as important” to “Just as important”. An example for a respondent choosing “Improvement in pain” as the most important attribute is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

First importance question in modified version of ACA

Figure 2.

Second importance question in modified version of ACA

To test the performance of the modified ACA importance questions, we recruited consecutive subjects followed at a hospital-based Bone and Joint Clinic. Inclusion criteria were knee pain on most days of the month, ability to read and write English, and age 18 to 89 years. Because treatment planning may differ in patients having undergone total joint replacement, patients with knee pain in a replaced joint were excluded.

Eligible subjects were recruited at the time of their regularly scheduled initial or follow-up appointment and were randomized to complete the original or the modified ACA importance questions. Both versions were otherwise identical. All subjects performed the survey before seeing their physician. We included six attributes in the ACA survey: improvement in pain, increase in energy, route of administration, risk of stomach upset, bleeding ulcer and monthly out-of-pocket cost. Each attribute included three levels all which had a natural order except route of administration (See Table 1). Subjects answered 18 paired comparison tasks (as recommended (3)) after which they were presented with a bar graph (generated by the software) illustrating their relative importances (see example provided in Figure 3). After completion of the ACA survey subjects were asked to 1) rank attributes and treatment options using a card sorting task and 2) indicate whether the bar graph depicting the relative importance of each attribute generated by ACA should be “longer”, “shorter”, or was “just right”.

Table 1.

Attributes and levels included in the ACA survey

| Attribute | Level |

|---|---|

| Improvement in pain and ability to walk and use stairs |

Big improvement in pain and ability to walk and use stairs |

| Moderate improvement in pain and ability to walk and use stairs | |

| Small improvement in pain and ability to walk and use the stairs | |

| Increase in overall energy, strength and well-being |

Big increase in overall energy, strength and well-being |

| Moderate increase in overall energy, strength and well-being | |

| No increase in overall energy, strength and well-being | |

| Way treatment can be given | Cream or pill |

| Injection into the knee. This can be repeated up to 4 times per year. | |

| Exercise 3 times per week for about 30 minutes each time. | |

| Risk of stomach upset | Does not cause stomach upset |

| Causes stomach upset in 10% (10 in a 100 people) | |

| Causes stomach upset in 30% (30 in a 100 people) | |

| Risk of ulcer | Does not cause bleeding ulcers |

| Causes bleeding ulcers in 1% (1 in 100 people) per year | |

| Causes bleeding ulcers in 4% (4 in 100 people) per year | |

| Cost | Costs $5 per month |

| Costs $10 per month | |

| Costs $25 per month |

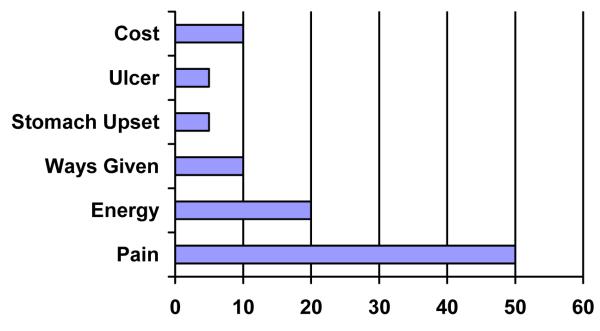

Figure 3.

Example of a bar graph generated by ACA to illustrate each subject’s relative importances

In addition to the ACA task, we collected demographic (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment status) and clinical (overall health status and severity of knee pain using an 11-point numeric rating scale) variables by self report.

Preference data were generated using Sawtooth Software SSI web V 6.4 and SMRT V 4.18. In ACA, regression models are constructed based on individual respondent’s ratings to the questions described above. This approach assumes that respondent’s ratings reveal some information about how they value the specific characteristics included in the survey. Characteristics which are rated higher are presumed to be of greater value or utility. A respondent’s utility is therefore a measure of their relative preference for each estimate of each characteristic. Utilities are calculated using a least squares updating algorithm. The final utility estimates reflect true least squares (3). Market simulators are used to convert the raw utilities into preferences for specific options. Preferences are calculated by first summing the utilities of the levels corresponding to each option. The utilities are then exponentiated and rescaled so that they sum to 100. This approach is based on the assumption that subjects’ prefer the option with the highest utility. Details related to simulation models used by ACA have been previously published (3).

We calculated the importance that respondents assigned to each characteristic by dividing the range of values for each characteristic by the sum of ranges, and multiplying by 100. The relative importances are proportions and sum to 100. We report the distribution of variables collected using descriptive characteristics, the time required to perform the task, the percent reporting that bar graphs were accurate, the percent whose rankings on card sorting matched those generated by ACA, and the mean number of scale points subjects used in the importance questions.

RESULTS

Seventy-four percent of eligible patients agreed to participate. Forty-nine patients were recruited. Twenty-four completed the original version of ACA and 25 the modified version. An average of 10 ± 3 minutes was required to complete both versions. Characteristics of the study population are illustrated in Table 2. The median relative importances and preferences for each group are provided in Tables 3 and 4 respectively. Predicted preferences were similar; however, the rank order of the relative importances differed across versions.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study population

| Characteristic | Original ACA (N=24) |

Modified ACA (N=25) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, range) | 61 (24 - 83) | 54 (25 - 77) |

| Male | 86% | 77% |

| White | 93% | 73% |

| College educated | 24% | 27% |

| Employed | 45% | 28% |

| Health status fair or poor | 34% | 33% |

| Pain (mean, range) | 7 (2 - 10) | 6 (3 - 10) |

Table 3.

Relative importances [median (range)]

| Attribute | Original ACA (N=24) |

Modified ACA (N=25) |

|---|---|---|

| Improvement in pain and ability to walk and use stairs |

18 (5 - 36) | 21 (7 - 40) |

| Increase in overall energy, strength and well-being |

20 (8 - 32) | 22 (3 - 35) |

| Route of administration | 22 (2 - 37) | 20 (5 - 30) |

| Risk of stomach upset | 17 (1 - 27) | 16 (2 - 27) |

| Risk of bleeding ulcer | 19 (2 - 31) | 17 (2 - 35) |

| Cost | 7 (2 - 27) | 5 (1 - 19) |

Table 4.

Predicted treatment preferences (mean ±SD)

| Treatment | Original ACA (N=24) |

Modified ACA (N=25) |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise | 48 ± 4 | 51 ± 5 |

| Anti-inflammatory | 7 ± 1 | 11 ± 3 |

| Topical | 6 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 |

| Corticosteroid Injection | 28 ± 4 | 25 ± 3 |

| Acetaminophen | 9 ± 2 | 8 ± 2 |

Subjects’ perceived accuracy of the ACA-generated relative importances is provided in Table 5. As can be seen, subjects felt that bar graphs illustrating the relative importances were more accurate for the modified version of ACA. This was especially true for pain where only 50% of respondents felt that the bar estimate was accurate. The remaining 50% felt that the bar representing pain should have been longer, indicated that the original version tended to underestimate the importance patients placed on relieving pain.

Table 5.

Percent reporting that bar graph was accurate

| Attribute | Original ACA (N=24) |

Modified ACA (N=25) |

|---|---|---|

| Route of administration | 75% | 88% |

| Improvement in pain and ability to walk and use stairs |

50% | 76% |

| Increase in overall energy, strength and well-being |

71% | 76% |

| Risk of stomach upset | 79% | 76% |

| Risk of bleeding ulcer | 79% | 88% |

| Cost | 79% | 84% |

The proportion of subjects for which the most important attribute chosen on the card sorting task matched that generated by ACA was greater for the modified compared to original version of the ACA task (48% vs 29%). The proportion of subjects for which the treatment option chosen on the card sorting task matched that predicted by ACA was also greater for the modified compare to original version of the ACA task (80% versus 75%). Subjects used a greater number of points to rate the importance of attributes on the modified version of ACA (3.4 ± 0.9) compared to the original version (2.7 ± 1.0), indicating that the modified version demonstrated greater discrimination among attributes.

DISCUSSION

ACA has many properties which make it a valuable tool to elicit patient preferences and facilitate medical decision-making. It can be designed to ensure that patients are made aware of all essential information related to appropriate treatment options, and therefore should improve patient knowledge and informed consent. ACA also improves the quality of decisions by making the trade-offs between competing options explicit. This is of direct clinical relevance since choices based on explicit trade-offs are less likely to be influenced by heuristics (errors in reasoning) which can lead to poor decisions (6). In addition, ACA questionnaires may be easily formatted to present individualized estimates of risks and benefits (7).

ACA is a unique form of CA in that it uses individual respondent’s answers to update and refine the questionnaire through a series of graded-paired comparisons. As a result, each respondent answers a customized set of questions. Because it is interactive, ACA is more efficient than other techniques and allows a large number of attributes to be evaluated without resulting in information overload or respondent fatigue. This is an important feature, since complex treatment decisions often require multiple trade-offs between competing risks and benefits. In addition to providing an estimate of preferences, ACA, like other forms of CA, can be used to examine the amount of importance respondents place on specific treatment characteristics. This feature enables physicians to gain insight into the reasons underlying their patients’ preferences, tailor discussions to address individual patient’s concerns, and ensure that decisions are made based on accurate expectations.

To enable patients to receive this output in real time, however, requires that patients respond to ACA’s importance questions, which are difficult to understand. The modified version of the ACA importance questions developed and tested in this pilot study appears to perform as well or better then the original version. In addition, our results suggest that the modified version may be better able to capture the relative impact of particularly important attributes (such as improvement in pain) than the original ACA.

The limitations of this study are inherent to those of small pilot projects and include lack of power to permit analytic statistics and limited generalizability. In addition, there were differences in the demographic characteristics across the two groups which may have influenced our results. However, it would be reasonable to use a simplified version of ACA, even if it only benefited a proportion of subjects. In summary, use of the simplified set of ACA importance questions presented in this paper is a reasonable alternative for investigators interested in examining the value of ACA as a potential decision support tool in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Fraenkel is supported by the K23 Award AR048826-01 A1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ryan M, McIntosh E, Shackley P. Methodological issues in the application of conjoint analysis in health care. Health Economics. 1998;7:373–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199806)7:4<373::aid-hec348>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C, et al. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technology Assessment. 2001;5:1–186. doi: 10.3310/hta5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orme B. [Accessed June 2009];The ACA technical paper. http://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/download/techpap/acatech.pdf.

- 4.King C, Hill A, Orme B. [Accessed June 2009];The “Importance” question in ACA: Can it be omitted? http://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/download/techpap/omitimp.pdf5.

- 5.Allenby GM, Rossi PE. [Accessed June 2009];Perspectives based on 10 years of HB in marketing research. http://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/download/techpap/allenby.pdf.

- 6.Janis IL, Mann L. Decision-making. A psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and committment. The Free Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraenkel L, Chodkowski D, Lim J, Garcia-Tsao G. Patients’ preferences for treatment of hepatitis C. Medical Decision Making. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0272989X09341588. [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]