Summary

Cancer cachexia has a significant negative effect on quality of life, survival and the response to treatment. Recent in vitro and experimental animal studies have shown that myosin may be the primary target of the muscle wasting associated with cancer cachexia. In this study, we have extended these analyses to detailed studies of regulation of myofibrillar protein synthesis at the gene level, myofibrillar protein expression and regulation of muscle contraction at the muscle cell level in a 63-year old man with a newly diagnosed small cell lung cancer and a rapidly progressing lower extremity muscle wasting and paralysis. A significant preferential loss of the motor protein myosin together with a downregulation of protein synthesis at the transcriptional level was observed in the patient with cancer cachexia. This had a significant negative impact on muscle fiber size as well as maximum force normalized to muscle fiber cross-sectional area (specific tension).

Keywords: Myosin, MuRF1, MAFBx, force generation capacity, skinned muscle fibers

Introduction

Cachexia is a condition associated with a variety of serious life-threatening diseases, including cancer, sepsis, AIDS, and congestive heart failure. The weight loss in cancer cachexia involves both adipose and muscle tissue. The muscle wasting is not simply due to malnutrition and nutritional supplements have been shown to be ineffective in restoring skeletal muscle protein content in patients with cancer cachexia (1) and the molecular events underlying cancer cachexia have been the subject of increasing scientific interest (2, 3).

There has been an increasing interest in the role played by inflammatory cytokines in cancer cachexia such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukin(IL)-1, IL-6, and interferon-γ. In a myogenic cell culture and an experimental rodent cancer model, Acharya et al. (4) reported that none of these cytokines induced dramatic cachexia-like effects by themselves, but in combination they promoted severe muscle wasting by selectively targeting myosin, the dominating sarcomeric protein in skeletal muscle, i.e., the molecular motor protein. In the in vitro experiments it was shown that a combination of TNF-α and interferon-γ selectively and progressively depleted myosin both at the protein and mRNA level. A parallel decline in the expression of the MyoD nuclear transcription supports a significant role of transcriptional regulation of myosin synthesis in this type of muscle wasting (4). In the rodent cancer model, the myosin loss was not associated with a decrease in myosin mRNA levels, and the myosin loss was primarily related to an enhanced activation of the ubiquitin ligase-dependent proteasome pathway (4). Numerous cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6 and IL-8, are up-regulated by the NFκB transcriptional factor and Kawamura and coworkers have shown in experimental animal models that blocking NFκB inhibits cancer cachexia, without affecting tumor growth (5, 6).

The primary aim of this study is to improve our understanding of the mechanisms underlying muscle paralysis and muscle wasting in a patient with cancer cachexia, with specific reference to myosin gene and protein expression, and the concomitant effects on regulation of muscle contraction at the single fiber level. It is hypothesized that the severe muscle weakness and loss of muscle mass associated with cancer cachexia is secondary to a preferential loss of myosin.

Clinical history

Patient

A 63 year-old man presented with a 6-month history of dyspnoea and was diagnosed to suffer from a small cell lung carcinoma and mild type 2 diabetes. Approximately 3 months after being diagnosed with lung cancer, electromyography (EMG), electroneurography (ENeG) and muscle biopsy was performed due to rapid muscle wasting, loss of muscle function and areflexia in the lower extremities. During this 9 month period, the patient had not been exposed to mechanical ventilation or non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents.

The patient was only given a single 1 ml i.v. dose of corticosteroids during the complete observation period.

The electroneurography (ENeG) and electromyography (EMG) analyses were performed according to standard procedures at the Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Uppsala (7). In short, surface electrodes were used to determine motor nerve conduction velocities, compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes, distal latencies and F-responses (median, ulnar, tibial, and peroneal nerves bilaterally) and sensory nerve conduction velocities and amplitudes (median, ulnar, radial and sural nerves bilaterally).

Disposable concentric needle EMG needles were used (Medtronic, Copenhagen, Denmark) in the analyses of spontaneous EMG activity, interference pattern, and quantitative motor unit potential measurements using the automatic Multi MUP analysis program. At least 20 motor unit potentials were analysed in each muscle (m. biceps brachii, m. extensor digitorum, m. vastus lateralis and m. tibialis anterior). The arm muscles were analysed on the right side and the leg muscles bilaterally. All measurements were performed using commercially available equipment (Keypoint, Medtronic).

The patient had very mild signs of sensory loss, but cognitive functions were intact. MR images of extremities confirmed severe muscle wasting, increased oedema and the absence of an ongoing active inflammatory response in proximal and distal lower extremity muscles. EMG and ENeG findings were complex showing combined myogenic and neurogenic changes. Only mild changes were observed in the arms, such as F-latencies at or slightly above the upper normal limit, mild decrease in compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes, and sensory nerve conduction velocities at or slightly below the normal limit in the median and ulnar nerves bilaterally. There were no signs of neuromuscular transmission failure upon repetitive 3 and 20 Hz supramaximal ulnar nerve stimulation and abductor digiti minimi muscle CMAP recordings. More severe neuropathic changes were observed in the motor nerves, but not in sensory nerves, in the lower compared to upper extremities, i.e., very low CMAP amplitudes (0.2-0.4 mV) upon supramaximal stimulation of the tibial nerve bilaterally and absent CMAPs upon peroneal nerve stimulation bilaterally.

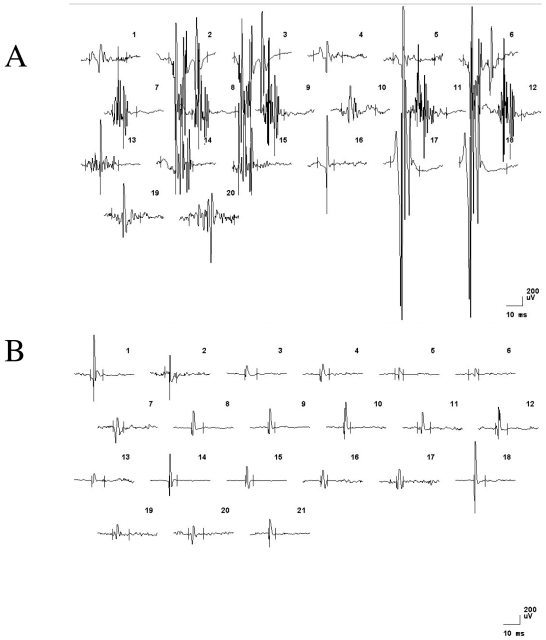

EMG recordings from proximal and distal arm muscles showed normal interference pattern and motor unit potential analyses, but a slight to moderate increase in spontaneous activity (fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves in m. biceps brachii and m. extensor digitorum communis). In the leg muscles, interference pattern analyses (turns per amplitude) displayed a myopathic pattern, a significant increase in spontaneous EMG activity and pathological motor unit potentials. A combination of both myopathic (low amplitude, short and polyphasic) and neuropathic (high amplitude, long duration, polyphasic and unstable) motor unit potentials were recorded in both distal and proximal leg muscles bilaterally (Fig. 1). Thus, the electrophysiological findings indicated a carcinomatous neuromyopathy in proximal and distal lower extremity muscles. A muscle biopsy was taken from an affected leg muscle (m. tibialis anterior).

Figure 1.

Motor unit potentials recorded with concentric needle electrodes from an affected lower extremity muscle (m. tibialis anterior A) and an unaffected upper extremity muscle (m. biceps brachi B). Horizontal and vertical calibration bars denote 10 ms and 200 μV, respectively.

Controls

For comparison, tibialis anterior muscle biopsy samples have been analysed from two (42 and 56 years) healthy men, a 61 year-old woman with cachexia related to malnutrition, an intensive care unit (ICU) patient with muscle wasting and a preferential myosin loss associated with acute quadriplegic myopathy (AQM) and from two female patients with tibial anterior muscle wasting due to hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy of demyelinating (HMSN type 1; 30 years) or axonal type (HMSN type 2; 74 years). In addition, a deltoid muscle biopsy sample from a male patient with cachexia related to progressive motor neuron loss (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS; 75 years) and malnutrition due to bulbar involvement was included. The electrophysiological examinations in patients with HMSN and ALS diseases showed signs of severe peripheral denervation with reinnervation, but the patient with cachexia due to malnutrition alone displayed normal EMG and ENeG findings.

Methods

Muscle Biopsy

Biopsy specimens from the patient with cancer cachexia were obtained from the left tibialis anterior muscle using the percutaneous conchotome method. The biopsy was dissected free of fat and connective tissues. One portion was frozen in isopentane chilled with liquid nitrogen and stored at -160 °C for morphological analyses. Small bundles of 25-50 fibers were dissected from another biopsy specimen and membrane permeabilized (8). The muscle bundles were treated with sucrose, a cryo-protectant, for 1-2 weeks for long-term storage (9).

Histopathology and electron microscopy

The frozen samples were used for histopathology and sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Gomori’s trichrome, and reacted for ATPases with preincubations at pH 4.3. and 10.4, NADH tetrazolium reductase, cytochrome-c-oxidase + succinate dehydrogenase and immunostained for fetal, neonatal, fast and slow myosin heavy chains (MyHCd, MyHCn, MyHCf and MyHCs; Novocastra, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK). The lesser diameters of type I and II fibers were measured in ATPase 4.3 stained sections using a computerized muscle biopsy analyser (Muscle Biopsy Surveyor®; PIT Oy, Turku, Finland). For electron microscopy (EM) small pieces were routinely fixed in 3% phosphate buffered glutaraldehyde, post-osmicated, dehydrated and embedded in epon. Thin sections were double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined in a JEOL JEM 1200 electron microscope.

Single muscle fiber experimental procedure

On the day of an experiment, a fiber segment length of 1 to 2 mm was left exposed to the solution between connectors leading to a force transducer (model 400A, Aurora Scientific) and a lever arm system (model 308B, Aurora Scientific) (10). The total compliance of the attachment system was carefully controlled and remained similar for all the single muscle fibers tested (6 ± 0.4% of fiber length). The apparatus was mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (model IX70; Olympus). While the fiber segments were in relaxing solution, sarcomere length was set to 2.75-2.85 μm by adjusting the overall segment length (8). The sarcomere length was controlled during the experiments using a high-speed video analysis system (model 901A HVSL, Aurora Scientific). The fiber segment width, depth and length between the connectors were measured (8). Fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) was calculated from the diameter and depth, assuming an elliptical circumference, and was corrected for the 20% swelling that is known to occur during skinning (10). The maximum force normalized to fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) was measured in each muscle fiber segment (8). After mechanical measurements, each fiber was placed in urea buffer in a plastic microcentrifuge tube and stored at -80 °C until analysed by gel electrophoresis.

Gel electrophoresis

The 6 and 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoreses (SDS-PAGE) were run to measure MyHC isoform expression and myosin:actin ratios in biopsy cross-sections and in single muscle fiber segments (11). For the 6% and 12% SDS-PAGE gels, the total acrylamide concentration was 4% and 3.5% in the stacking gel and 6 and 12% in the running gel, respectively. The gel matrix included 30% and 10% glycerol in the 6% and 12% SDS-PAGE, respectively, as described previously (11). Briefly, electrophoresis was performed at a constant current of 16 mA for 5 hours with a Tris-glycine electrode buffer (pH 8.3) at 15 °C (SE 600 vertical slab gel unit, Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, CA, USA).

The 12% SDS-PAGE gels were stained with Coomassie blue (12), since the Coomassie staining penetrates the gel and allows accurate and highly reproducible quantitative protein analyses (12). The 6% SDS-PAGE used for single muscle fibers segment analyses were silver-stained, due to high sensitivity (13). All gels were subsequently scanned in a soft laser densitometer (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), with a high spatial resolution (50 μm pixel spacing) and 4096 optical density levels. The volume integration function was used to quantify the amount of protein on 12% and 6% gels (ImageQuant TL Software v. 2003.01, Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). These values were used to calculate myosin:actin protein ratios in both whole biopsies and single fibers, as well as to relate the amount of myosin and actin to the total protein of each fiber, and to quantify the percentage of each myosin isoform in whole biopsies.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and mRNA expression analyses

Total RNA was extracted from frozen muscle tissue (5-10 mg) using Qiagen RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). Muscle tissue was homogenized using a rotor homogenizer (Eurostar Digital, IKA-Werke). Qiashredder™ (Qiagen, Inc.) columns were used to disrupt DNA. RNA was eluted from RNeasy® Mini columns with 30 ul of RNase free water. RNA was quantified using Ribogreen® (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), on a Plate Chameleon™ Multilabel Platereader (Hidex, Oy, Finland). Equal amounts (100 ng) of total RNA were synthesized into cDNA using Ready-To-Go™ You-Prime First-Strand-Beads, 0.66 μg random hexamers and 0.05 μg oligo-dT primers (all Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA was diluted to a volume of 100 μl and stored at -80°C until RT-PCR quantification. Real-time PCR was used to quantify the mRNA levels for the dominating thick and thin filament proteins expressed in the human tibialis anterior muscle, i.e., the β/slow (type I) MyHC isoform and skeletal-βactin.

Taqman primers and probes were designed using the software Primer Express® (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). MAFBx (Atrogin1) and MuRF 1 primer sequences were obtained from a previous publication authored by Urso et al (14). Sequences for primers and probes are listed in Table 1. Probes, labelled with FAM (N-(3-fluoranthyl) maleimide), and primers were purchased from Thermo Electron (Thermo Electron GmBH, Ulm, Germany).

Table 1. Primer and probes for real-time PCR.

| Gene | Forward Primer | Probe | Reverse Primer | Expectedproductsize |

| MyHCI | CTCGCTCCCTCAGCACAGA | TGGAACATCTGGAGACCTTCAAGCGG | CTGCTCAGTCAAGTCGGAGATCT | 125 |

| α-actin | CTACCCGCCCAGAAACTAGACA | ACCACCGCCCTCGTGTGCG | CCAGGCCGGAGCCATT | 79 |

| 28S | GTGCATGGCCGTTCTTAGTTG | TGGAGCGATTTGTCTGGTTAATTCCGATAACor Sybr Green® | AGCATGCCGAGAGTCTCGTT | 74 |

All primers and probes were HPLC purified. Real-time PCR was run using MyiQ™ single-color real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The AmpliTaq® Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems) was heat-activated at 95 °C for 9 minutes, followed by 50 cycles of a two-step PCR with denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and a combined annealing and extension step at 60 °C for one minute. The PCR was performed in a volume of 25 μl, which included 0.4 μM of each primer and 0.2 μM of probe.

When optimizing each PCR, PCR products were run on 2% agarose gels to ensure that primer-dimer formation was not occurring. Only one product of expected size was detected in all cases. Each sample was run in triplicates. With each PCR run, a standard cDNA was included in triplicates of three concentrations comprising a standard curve. A control sample was used for the standard. Finally, negative controls without cDNA were included on each plate.

Sequence detection software 1.0.410 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) was used to analyze the raw real-time PCR data. The threshold cycle (CT) data acquired from the RT-PCR run was related to the standard curve to obtain the starting quantity (SQ) of the template cDNA for each sample. Each sample in a triplicate had to be within 0.5 CT of each other to be included in the analysis. The triplicates of each sample were then averaged. The SQ of the sample was related to the triplicate average of the internal standard, 28S (GenBank accession AF102857). Sequences for 28S primers and probe are listed in Table 1. The ribosomal RNA 28S was chosen as an internal standard since it was not affected by the experiment. Standard curves for both the gene of interest and 28S were included on each plate. To be accepted, slopes of the standard curves had to be between -3.0 and -3.5 and were not allowed to differ by more than 5%. The values of the samples, related to the standard, were then analyzed.

Statistics

Means, standard deviations, linear regressions and correlation coefficients were calculated from individual values by using standard procedures. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Structural findings

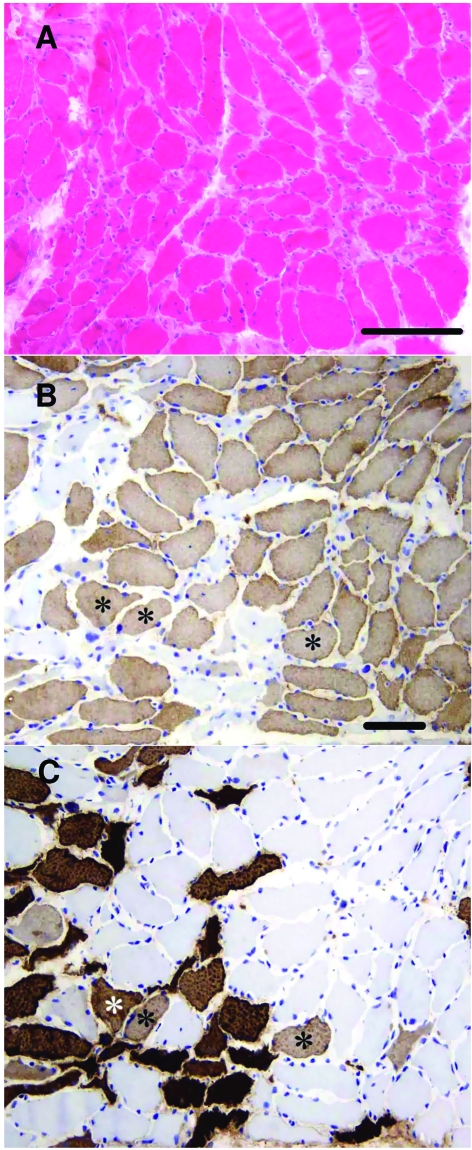

The size variation of the myofibers was increased with many markedly atrophic fibers (Fig. 2A). The mean lesser diameters of slow type I and fast type II fibers were 36.5 and 30.2 μm, respectively. The atrophic fibers were widely distributed, no definite group atrophies were detected. Type I fibers predominated (approximately 75%) (Fig. 2B, C). The fibers appeared shrunken with slightly corrugated outlines and widened endomysial space. No fiber necrosis or phagocytosis was observed. A few fibers were immunopositive for MyHCd or MyHCn, some simultaneously. These MyHCd and/or MyHCn positive fibers were somewhat smaller than the mean size. Furthermore, several fibers expressed both MyHCs and MyHCf (Fig. 2B, C). The immunostaining of the sarcoplasm for the four different myosins was generally homogeneous, no significant focal losses of staining were seen. The intensity of MyHCs immunopositive fibers appeared weaker than in control biopsies, whereas MyHCf staining was of approximately normal intensity (Fig. 2B, C). A couple of fibers were cytochrome-coxidase negative and a few fibers harbored rimmed vacuoles.

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin stained cross-sections show increased fiber size variation and reduced mean fiber size (A). There are numerous random atrophic-angulated fibers with irregular contours. No necroses or phagocytosis is visible. Semiconsecutive sections stained for MyHCs (B) and MyHCf (C) show the predominance of MyHCs positive fibers. Several fibers express both MyHCs and MyHCf (three marked with an asterisk). Fast MyHCf positive fibers are more atrophic. The immunopositivity is homogeneous without significant focal losses within the sarcoplasm, but the intensity of MyHCs staining appears relatively pale. B. MyHCs and C. MyHCf both with hematoxylin counterstain. The horizontal bars denote 200 μm (A) and 100 μm (B, C).

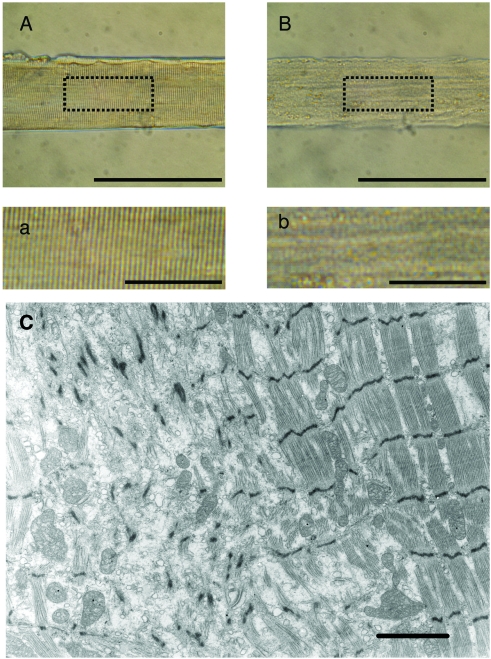

A regional loss of the normal cross-striation pattern was often observed at the single muscle fiber level (Fig. 3B,b), probably reflecting the loss of thick filament proteins. This is supported by EM findings: desarray with marked loss of myofilaments and with scattered disrupted Z-disks to which sparse myofilaments were attached. In better preserved areas generalised thinning of myofibrils was observed (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Chemically skinned single muscle fiber segments from the percutaneous muscle biopsy attached to force transducer and servomotor (A, B). The specific tension developed by the fiber from the control subject (A) and from the patient with cancer cachexia (B) was 25 N/cm2 and 4 N/cm2, respectively. Magnification of the boxes in A and B illustrate the blurring of the cross-striation pattern in the fiber from the patient (b) compared with the control fiber (a). The average sarcomer length was 2.76 μm in both fiber segments (A, B). Electron micrograph shows the loss of myofilaments in the left half of the figure with haphazardly scattered Z-disks remaining. Myofilaments in the slightly thinned myofibrils on the right appear normal (C). The scale bars represent 200 μm (A, B), 50 μm (a, b) and 2 μm (C).

Myofibrillar protein and gene expression

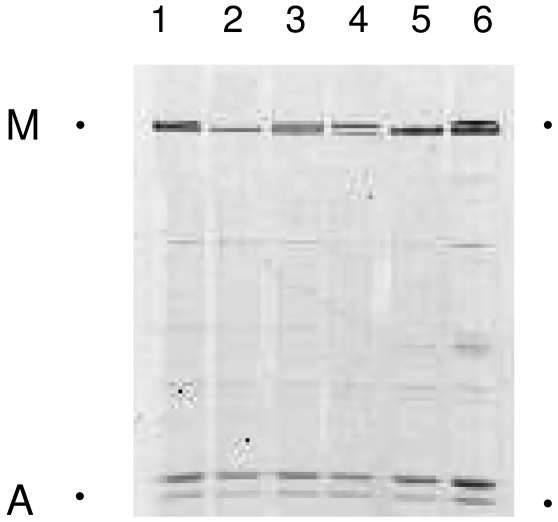

In accordance with the 2:1 stochiometric relation between the dominating thick (myosin) and thin (actin) filament proteins in skeletal muscle, we observed myosin:actin ratios varying between 1.9 and 2.3 in two healthy control subjects, in a patient with cachexia and muscle wasting due to malnutrition, and in patients with muscle atrophy due to peripheral denervation caused by either demyelination (HMSN type1) or axonal loss (HMSN type 2, ALS). In the patient with cancer cachexia, on the other hand, there was a dramatic preferential loss of myosin, but the myosin loss varied in different regions of the same muscle biopsy. The average myosin:actin ratio calculated at four different protein concentrations was 0.12, 0.59 and 0.80 in different portions of the biopsies (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Myofibrillar protein separations on 12% SDS-PAGE in the patient with cancer cachexia (2, myosin:actin ratio 0.8), a patient with cachexia due to malnutrition (3, myosin:actin ratio 1.8), two healthy control subjects (1, myosin:actin ratio 2.0; 4, myosin:actin ratio 1.8), a patient with Charcot Marie-Tooths disease type 1 (5, myosin:actin ratio 2.1) and type type 2 (6, myosin:actin ratio 2.1). The part of the gel with the myosin (M) and actin (A) bands are shown.

Myosin and actin mRNA expression normalized to 28S ribosomal RNA was measured in the tibialis anterior muscle sample from the patient with cancer cachexia and compared with normal control subjects and patients with muscle wasting due to HMSN, AQM and malnutrition. A down-regulation of both myosin and actin synthesis at the transcriptional level was observed in our patient with cancer cachexia, i.e., MyHC and actin mRNA levels were 21 and 30% of control values. MyHC (10%) and actin (7%) mRNA levels were also lower in the patient with AQM. The MyHC and Actin mRNA expression in the patients with muscle wasting due to chronic peripheral denervation (HMSN) and malnutrition were within 70% of control values. The mRNA expression of the two ubiquitin E3 ligases MuRF-1 and MAFBx (Atrogin1), normalized to 28S ribosomal RNA, were 103% (MuRF-1) and 22% (Atrogin1) higher in the patient with cancer cachexia. In all other patients, MuRF-1 and Atrogin1 expression was similar or slightly lower than in the control samples.

Contractile measurements

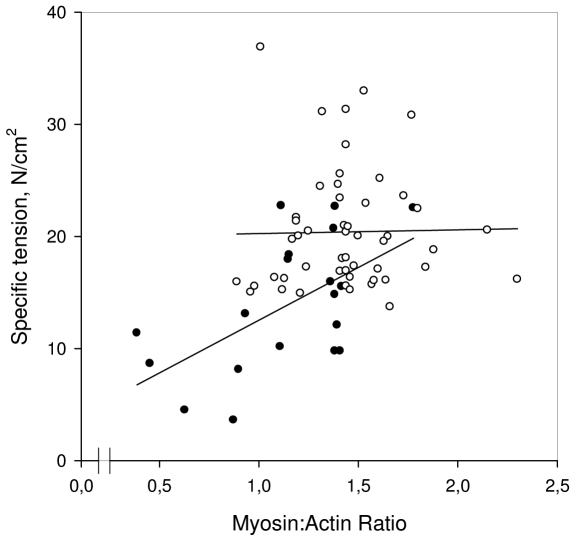

The cross-sectional area was measured in single tibialis anterior muscle fibers at a 2.75-2.85 μm fixed sarcomere length (2.79 ± 0.03 μm). In accordance with the morphometrical analyses of the enzyme-histochemically stained biopsy cross-sections, the muscle fibers were approximately half the size (p < 0.05) in the patients compared with the control fibers expressing both the type I (1030 ± 290 vs. 2410 ± 880 μm2) and IIa (1300 ± 590 vs, 2600 ± 960 μm2) MyHC isoforms. The myosin:actin ratios and the force generating capacity, i.e., maximum force normalized to fiber cross-sectional area (specific force), at the single muscle fiber level did not differ between fibers expressing the type I and II MyHC isoforms in either the patient or controls and they have therefore been pooled. In accordance with the observations at the muscle biopsy level, myosin:actin ratios were lower (p < 0.01) in the patient with cancer cachexia (1.14 ± 0.36) than in the controls (1.44 ± 0.28). The specific force at the single muscle fiber level was lower (p < 0.001) in the patient with cancer cachexia (13.8 ± 5.9 N/cm2) than in the control fibers (20.4 ± 5.3 N/cm2). There was a significant variability in both specific force and myosin:actin ratios in the patient as well as in the control fibers. In the patient with cancer cachexia, there was a correlation (r = 0.58, p < 0.01) between specific force and the myosin:actin ratio, suggesting a significant role of the preferential myosin loss for the decreased force generation capacity. The variability in specific force among control fibers was, on the other hand, unrelated to the myosin:actin ratio (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Specific force vs. myosin:actin ratio in single muscle fibers from the patient with cancer cachexia (filled symbols) and the controls (open symbols). Regression lines within the myosin:actin ratio range is given for both control (p = n.s.) and patient (r = 0.58; p < 0.01) fibers.

Although myosin:actin ratios decreased significantly both at the single fiber and biopsy level in the patient with cancer cachexia, the absolute change in the ratio was smaller at the fiber level. The reason for this difference is not known, but it is suggested to be related to methodology in combination with a bias in the selection of fibers for contractile recordings.

The most atrophic fibers from the patient broke during dissections or during activations, showed regional loss of the cross-striation pattern or developed non-uniform sarcomere lengths during maximum calcium activations, and were therefore not included in the analyses, i.e., the most pathological fibers with the lowest myosin:actin ratios. The myosin loss may accordingly be greater than observed at the single fiber level. From this follows that the overall reduction in specific force may be significantly larger than 30%.

Thus, the reduction in force generation capacity together with the 50% reduction of muscle fiber cross-sectional area can accordingly account fully for the muscle paralysis in the patient with cancer cachexia.

Discussion

The cachectic state in patients with cancer indicates poor prognosis by lowering responses to chemotherapy and radiation. More than 50% of patients with cancer suffer from cachexia and nearly a third of mortalities are estimated to result from cachexia rather than the tumor burden itself (15). There is accordingly a significant need for a detailed understanding of the mechanisms underlying cancer cachexia. The increase in inflammatory cytokine production in cancer cachexia is thought to trigger the muscle wasting. Recent in vitro and experimental rodent cancer models have shown that the combination of specific cytokines has a dramatic impact on protein loss where the motor protein myosin appears to be the primary target (4).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study focussing on myosin expression and muscle fiber function in patients with cachexia associated with small cell lung cancer. The preferential loss of myosin and the consequent impairment in muscle fiber function are forwarded as the dominating mechanisms causing the rapidly progressing muscle wasting and weakness in our patient.

A preferential loss of myosin and myosin associated proteins has been repeatedly documented in critically ill ICU patients with AQM, according to electron microscopy, electrophoretic separation of myofibrillar proteins, enzyme- and immunocytochemical analyses (16–20). Widespread myosin loss has therefore been considered to be essentially pathognomonic of AQM (21). Patients with AQM have typically been mechanically ventilated for several days and exposed to sepsis, non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents and corticosteroids. The preferential myosin loss has therefore been used as a sensitive diagnostic marker of AQM. The dramatic preferential loss of myosin observed in our cancer cachexia patient demonstrates that a decreased myosin:actin ratio is not a pathognomonic finding in the acquired muscle paralysis observed in critically ill ICU patients (18, 19, 22). However, distinguishing the muscle weakness/paralysis in patients with cancer cachexia from ICU patients with AQM should not impose a diagnostic problem due to the differences in clinical history, phenotype and electrophysiology (ENeG and EMG).

The electrophysiological and histopathological observations in the patient with cancer cachexia were consistent with a “carcinomatous neuromyopathy” with preferential involvement of lower extremity muscles. This combined neurogenic and myogenic disorder is most frequently observed in patients with cachexia associated lung cancer (23, 24). In AQM, the myosin loss has been related to both enhanced myofibrillar protein degradation and a downregulation of myosin synthesis at the transcriptional level (18, 25). Low myosin and actin mRNA levels were observed in the patient with cancer cachexia and in the ICU patient with AQM, in spite of a preferential loss of myosin at the protein level. The similar changes in myosin and actin regulation at the transcriptional level, but the significant differences at the protein level, i.e., the preferential loss of myosin, may suggest differences in post-transcriptional regulation or in protein degradation. Both myosin and actin have long turnover rates, i.e., reports in the literature regarding myosin turnover rate are variable, but a turnover rate as low as 1-2% per day or a half-life as long as of 30 days have been reported (26, 27), with actin having a half-life approximately twice as long as myosin (28). The differences in myosin and actin protein expression despite similar changes at the gene level may accordingly be explained by differences in protein turnover rate, although differences in, e.g., translational regulation or protein degradation, cannot be ruled out.

Immune and tumor-derived cytokines are known to play an important role in the muscle wasting associated with cancer and the majority of these cachectic factors regulate muscle wasting by reducing protein synthesis at the translational level and by stimulating protein breakdown primarily through the activation of the ATP-dependent ubiquitinproteasome pathway (2, 29). A number of different signaling pathways have been shown to be involved in muscle atrophy, some of which may play a significant role in the muscle wasting associated with cancer and lending themselves as targets for pharmacological treatment of the cachexia associated with cancer (5, 6). It is interesting to note that most of these pathways appear to mediate their effects through activation of the ubiquitin proteasome degradation pathway, measured through the induction of MuRF1 and MAFBx (Atrogin1).

The increased levels of these ubiquitin E3 ligases indicate that myofibrillar protein degradation contributes to the myofibrillar protein loss in the patient with cancer cachexia (29). Léger and co-workers recently reported increased MAFBx (Atrogin1) expression in ALS patients with severe muscle wasting, but MuRF1 mRNA levels were not affected and it was claimed that it remains unknown if MuRF1 plays a role in other models of human muscle wasting (30). The patient with cancer cachexia in this study had a > 2-fold increase in MuRF1 mRNA expression compared with normal controls. This is consistent with the increased expression of these two E3 ligases in the muscle wasting observed in the early phase following spinal cord injury in humans (14). MuRF1 and MAFBx (Atrogin1) mRNA expression in our other patients with muscle wasting secondary to chronic peripheral denervation (HMSN type 1 and type 2), malnutrition and AQM were, on the other hand, not increased compared with control subjects.

In conclusion, myosin appears to be the preferred substrate in the muscle wasting associated with cancer cachexia in the patient with a small cell lung cancer and severely impaired lower extremity muscle function. The preferential myosin loss appears to be secondary to the combined effect of decreased synthesis at the transcriptional level and enhanced myofibrillar protein degradation via the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. This confirms recent in vitro and experimental animal studies of a cytokine mediated preferential loss of myosin in cancer cachexia due to altered transcriptional regulation of synthesis and enhanced protein degradation. This case report will be continued in a larger group of patients with cachexia associated with small cell lung cancer and specific interest will be focused on intracellular signaling pathways regulating myofibrillar protein synthesis and degradation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Yvette Hedström and Ann-Marie Gustavsson for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, National Institute of Health (NIAMS: AR 045627, AR 047318, AG014731), the Swedish Sports Research Council, Association Française Contre les Myopathies (AFM) and the Swedish Research Council (08651) to L.L., and AFM to J.O.

References

- 1.Evans WK, Makuch R, Clamon GH, et al. Limited impact of total parenteral nutrition on nutritional status during treatment for small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 1985;45:3347-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acharyya S, Guttridge DC. Cancer cachexia signaling pathways continue to emerge yet much still points to the proteasome. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:1356-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ventadour S, Attaix D. Mechanisms of skeletal muscle atrophy. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2006;18:631-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acharyya S, Ladner KJ, Nelsen LL, et al. Cancer cachexia is regulated by selective targeting of skeletal muscle gene products. J Clin Invest 2004;114:370-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawamura I, Morishita R, Tomita N, et al. Intratumoral injection of oligonucleotides to the NF kappa B binding site inhibits cachexia in a mouse tumor model. Gene Ther 1999;6:91-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawamura I, Morishita R, Tsujimoto S, et al. Intravenous injection of oligodeoxynucleotides to the NF-kappaB binding site inhibits hepatic metastasis of M5076 reticulosarcoma in mice. Gene Ther 2001;8:905-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stalberg E, Falck B, Gilai A, Jabre J, Sonoo M, Todnem K. Standards for quantification of EMG and neurography. The International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1999;52(Suppl):213-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsson L, Moss RL. Maximum velocity of shortening in relation to myosin isoform composition in single fibres from human skeletal muscles. J Physiol 1993;472:595-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frontera WR, Larsson L. Contractile studies of single human skeletal muscle fibers: a comparison of different muscles, permeabilization procedures, and storage techniques. Muscle Nerve 1997;20:948-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss RL. Sarcomere length-tension relations of frog skinned muscle fibres during calcium activation at short lengths. J Physiol 1979;292:177-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsson L, Moss RL. Maximum velocity of shortening in relation to myosin isoform composition in single fibres from human skeletal muscles. J Physiol 1993;472:595-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Syrovy I, Hodny Z. Staining and quantification of proteins separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J Chromatogr 1991;569:175-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giulian GG, Moss RL, Greaser M. Improved methodology for analysis and quantitation of proteins on one-dimensional silver-stained slab gels. Anal Biochem 1983;129:277-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urso ML, Chen YW, Scrimgeour AG, et al. Alterations in mRNA expression and protein products following spinal cord injury in humans. J Physiol 2007;579:877-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Eys J. Nutrition and cancer: physiological interrelationships. Annu Rev Nutr 1985;5:435-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.al-Lozi MT, Pestronk A, Yee WC, Flaris N, Cooper J. Rapidly evolving myopathy with myosin-deficient muscle fibers. Ann Neurol 1994;35:273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danon MJ, Carpenter S. Myopathy with thick filament (myosin) loss following prolonged paralysis with vecuronium during steroid treatment. Muscle Nerve 1991;14:1131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsson L, Li X, Edstrom L, et al. Acute quadriplegia and loss of muscle myosin in patients treated with nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents and corticosteroids: mechanisms at the cellular and molecular levels. Crit Care Med 2000;28:34-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto N, Nakamura T, Yasui Y, Torii J. Analysis of muscle proteins in acute quadriplegic myopathy. Muscle Nerve 2000;23:1270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sander HW, Golden M, Danon MJ. Quadriplegic areflexic ICU illness: selective thick filament loss and normal nerve histology. Muscle Nerve 2002;26:499-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacomis D, Zochodne DW, Bird SJ. Critical illness myopathy. Muscle Nerve 2000;23:1785-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stibler H, Edstrom L, Ahlbeck K, Remahl S, Ansved T. Electrophoretic determination of the myosin/actin ratio in the diagnosis of critical illness myopathy. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:1515-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubinstein MK. Carcinomatous neuromyopathy. The non-metastatic effects of cancer on the nervous system. Calif Med 1969;110:482-92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lane RJM. Handbook of muscle disease. In: New York: Marcel Dekker Inc. 1996, p. 398. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norman H, Zackrisson H, Hedström Y, et al. Changes in myofibrillar protein and mRNA expression in patients with Acute Quadriplegic Myopathy during recovery. 2007 (submitted for publication). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kay J. Intracellular protein degradation. Biochem Soc Trans 1978;6:789-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith K, Rennie MJ. The measurement of tissue protein turnover. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;10:469-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin AF. Turnover of cardiac troponin subunits. Kinetic evidence for a precursor pool of troponin-I. J Biol Chem 1981;256:964-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams A, Sun X, Fischer JE, Hasselgren PO. The expression of genes in the ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway is increased in skeletal muscle from patients with cancer. Surgery 1999;126:744-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leger B, Vergani L, Soraru G, et al. Human skeletal muscle atrophy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis reveals a reduction in Akt and an increase in atrogin-1. Faseb J 2006;20:583-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]