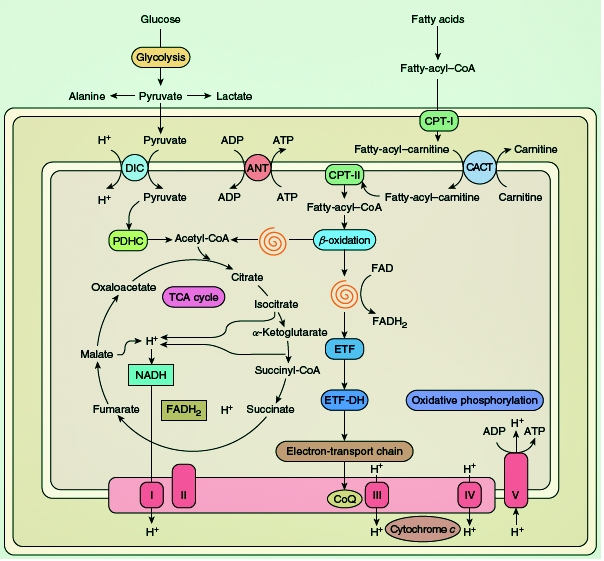

Skeletal muscle is a marvelous motor and much more versatile than we give it credit for. Suffice it to consider the different performances of flight muscles in migrating birds, which cross very long distances non-stop, the cricothyroid muscle in bats, which emits ultrasound signals, and the leg muscles of a human athlete, who can run the 100-meter dash in less than 10 seconds. Obviously, such diverse performances require different fuels. At rest, human muscle utilizes almost exclusively fatty acids, as indicated by the very low respiratory quotient (around 0.7). At the other end of the spectrum, during extremely intense exercise, close to vO2max, energy derives mostly from glycogen through anaerobic glycolysis, a cytosolic pathway (Fig. 1). During submaximal exercise of high intensity (70% to 80% vO2max), glycogen is again the preferred source of energy, which, however, derives from aerobic glycolysis, providing pyruvate as the anaplerotic substrate for the mitochondrial Krebs cycle (Fig. 1). During submaximal exercise of moderate intensity (< 50% vO2max), muscle initially utilizes blood glucose, but – as the exercise continues beyond a few hours – there is a gradual shift from the oxidation of glucose, a finite fuel derived from liver glycogen, to the oxidation of fatty acids, a virtually inexhaustible fuel derived from fat stores (1).

Figure 1.

elected metabolic pathways in a schematic rendition of a mitochondrion. The spirals indicate the sequential reactions of the β-oxidation pathway, resulting in the liberation of acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) and the reduction of flavoprotein. Abbreviations: ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CACT, carnitine acyl-carnitine translocase; CoQ, coenzyme Q; CPT, carnitine palmitoyltransferase; DIC, dicarboxylate carrier; ETF, electron-transfer flavoprotein; ETFDH, electron-transfer flavoprotein dehydrogenase; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; FADH2, reduced FAD; PDHC, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; I, complex I; II, complex II; III, complex III; IV, complex IV; V, complex V.

Two reactions are immediate sources of energy: (i) the creatine kinase (CK) reaction that breaks phosphocreatine (PCr) down to ATP and creatine in the presence of ADP through the creatine kinase (CK) reaction (PCr + ADP + H+ = ATP + Cr); and (ii) the adenylate kinase reaction, generating ATP and AMP from the condensation of two molecules of ADP (2ADP = ATP + AMP). However, by far the largest amount of energy for exercise derives from oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria and a much smaller amount of energy comes from anaerobic glycolysis, which is crucial only during isometric contraction (when blood supply is virtually cut off). The still widely held belief that the exercise intolerance that characterizes many glycogenoses is due to a block of anaerobic glycolysis is exaggerated and probably due to the popularity of the forearm ischemic exercise introduced by Brian McArdle in 1951 (2). In truth, the pathophysiology of exercise intolerance in McArdle disease and similar muscle glycogenoses is mostly due to a block of aerobic glycolysis.

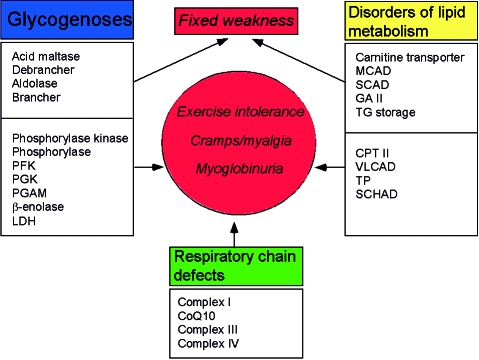

Disorders of energy supply to muscle, irrespective of whether the defects involve carbohydrate metabolism, lipid metabolism, or the respiratory chain, result in one of two syndromes: (i) exercise intolerance, often punctuated by recurrent and reversible “crises” of muscle breakdown (rhabdomyolysis) and myoglobinuria; or (ii) chronic subacute weakness (Fig. 2). Focusing our attention on the glycogenoses, all defects associated with the former syndrome involve glycogen breakdown or glycolysis and are triggered by exercise, whereas the latter syndrome is associated with defects in a glycogen synthetic enzyme (brancher), the lysosomal glycogenolytic enzyme (acid maltase [α-glucosidase]), one glycolytic enzyme (aldolase), and, rather surprisingly, a glycogenolytic enzyme (debrancher) that works hand-in-hand with myophosphorylase The pathogenesis of weakness in the second group of glycogenoses is not completely clear. In part, at least, it relates to the multisystem nature of the enzyme defects. For example, the profound weakness of infants with glycogen storage disease (GSD) type II is both myogenic and neurogenic, as autopsy studies have shown massive glycogen storage in both upper and lower motor neurons (3, 4), which may also explain the tongue fasciculations often observed in these babies. Peripheral nerve involvement probably accounts for the distal muscular atrophy and the “mixed” myogenic and neurogenic EMG pattern shown by patients with GSD III (debrancher deficiency). Another explanation often proposed is that muscle glycogen accumulation is much greater in glycogenoses characterized by fixed weakness than in those dominated by recurrent cramps and myoglobinuria, and this may mechanically disrupt the contractile apparatus. However, both mechanisms leave unanswered questions: for example, why are adult patients with GSD II weak, although glycogen accumulation is usually modest and confined to skeletal muscle?

Figure 2.

The two major syndromes associated with defects of muscle substrate utilization.

Glycogen is a highly ramified polymer of glucose in which linear chains of glucosyl units “stranded” together by α-1,4-bonds sprout – at regular intervals – side chains through α-1,6-glucosidic bonds: the resulting highly symmetrical spherical structure of each glycogen molecule makes it spatially efficient and hydrophilic: these are the osmiophilic β-particles shown by electron microscopy under the sarcolemma and – to a lesser extent – between myofibrils. For many years, it was unclear what was the primer of glycogen synthesis, i.e. which enzyme stranded together the first glucosyl units. This starter enzyme – called glycogenin – is now known (5): the subsequent growth of glycogen into a spherical polymer is catalyzed by the sequential and – as we shall see – highly coordinated actions of two enzymes: (i) glycogen synthetase, which attaches glucosyl units in α-1,4-glucosidic bonds from UDP-glucose to nascent linear chains of glycogen until a length of approximately 10 glucosyl units is reached; and (ii) the branching enzyme, which removes a short linear chain of approximately 4 glucosyl units and attaches it to a longer chain in an α-1,6-glucosidic bond, thus starting a new chain.

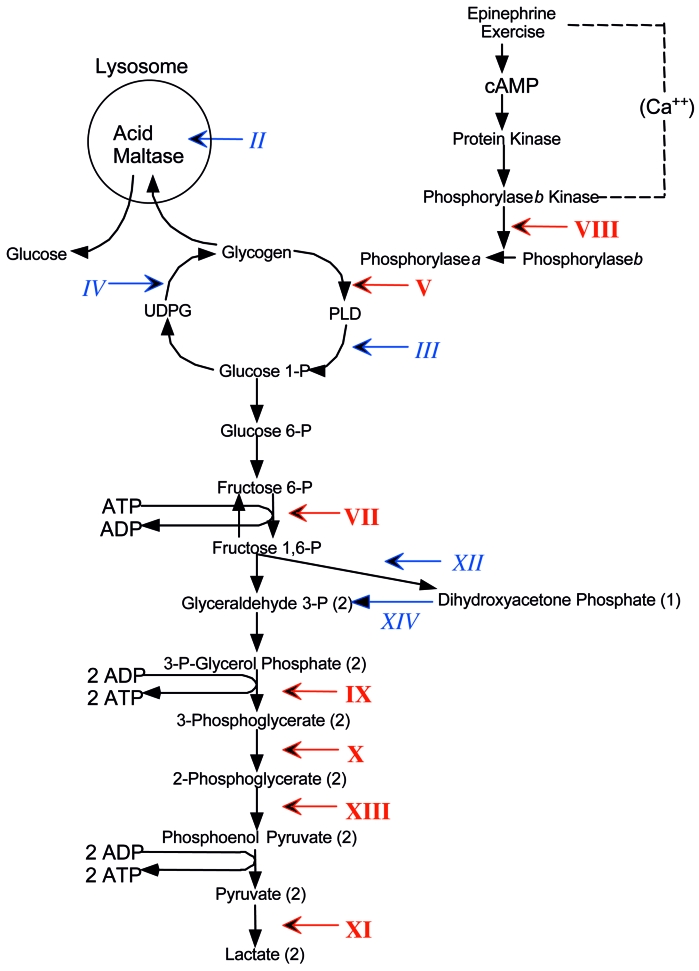

It is not the purpose of this article to review in detail the muscle glycogenoses, for which the reader is referred to recent comprehensive articles (6, 7). However, Figure 3 highlights those enzyme defects that have been associated with muscle glycogenoses within a schematic metabolic pathway of glycogen metabolism, showing by italic Roman numerals the GSD causing exercise intolerance and myoglobinuria, and by plain text Roman numerals those causing fixed weakness. In the rest of this article, I will consider a few comparative aspects between GSD V and GSD VII and provide a general framework for the more specific presentations that will follow.

Figure 3.

Scheme of muscle glycogen metabolism and glycolysis designating the glycogen storage diseases (GSD) affecting muscle with Roman numerals. Numerals in italics indicate GSD causing exercise intolerance, cramps and myoglobinuria. Numerals in plain text indicate GSD causing fixed weakness. The numerals denote defects in the following enzymes: II, acid maltase; III, debrancher; IV, brancher; V, myophosphorylase; VII, phosphofructokinase (PFK); VIII, phosphorylase b kinase (PHK); IX, phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK); X, phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM); XI, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH); XII, aldolase A; XIII, β-enolase. Abbreviations: c-AMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; PLD, phosphorylase-limit dextrin; UDPG, uridine-diphosphate glucose.

Starting from the glycogenoses associated with premature fatigue (summarized in Table 1), I will first pay homage to Brian McArdle, who in 1951, on the strength of astute clinical reasoning and simple laboratory studies, described the disease that is better known by its eponym than by its biochemical defect (myophosphorylase deficiency) (2). He studied a young man with exercise intolerance and cramps. He noted that ischemic exercise resulted in painful cramps of forearm muscles, and that no electrical activity was recorded from the shortened muscles, indicating that they were in a state of contracture. He also noted that oxygen consumption and ventilation were normal at rest but increased excessively with exercise. Having observed that venous lactate and pyruvate did not increase after exercise, McArdle concluded that his patient’s disorder was “characterized by a gross failure of the breakdown of glycogen to lactic acid”. Nor was the specific involvement of muscle lost on McArdle, who noted that epinephrine elicited a normal rise of blood glucose and “shed blood” in vitro accumulated lactate normally, leading him to conclude that “the disorder of carbohydrate metabolism affected chiefly if not entirely the skeletal muscles”.

Table 1. Main features of the glycogen storage diseases (GSD) associated with exercise intolerance, cramps, and myoglobinuria.

| Enzyme GSD # | Non-muscle tissues affected | Isozyme or subunit | Chromosomal location | Common mutations |

| Phosphorylase b kinase GSD VIII |

liver | PHKαM PHKβ |

Xq12-13 16q12-13 |

|

| Phosphorylase GSD V |

M | 11q13 | R49X (Caucasian) | |

| PFK GSD VII |

RBS | PFK-M | 1cen-q32 | Δ5 (Ashkenazi) |

| PGK GSD IX |

RBC CNS |

PGK-1 | Xq13 | |

| PGAM GDS X |

PGAM-M | 7p13-12.3 | ||

| LDH GSD XI |

Smooth muscle skin | LDH-A | 11p15.4 | |

| β-enolase GSD XIII |

β | 17pter-q11 |

It is instructive to compare McArdle disease, due to a block of glycogen breakdown, with Tarui disease (GSD VII), in which a defect of muscle phosphofructokinase (PFK) blocks glycolysis. Although, predictably, the clinical pictures are very similar and dominated by undue fatigue, cramps, and recurrent myoglobinuria, there are interesting clinical, laboratory, and pathological differences (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparative clinical and laboratory features of McArdle disease (GSD V) and Tarui disease (GSD VII).

| GSD V | GSD VII | |

| Other tissues involved | None | RBC |

| Glucose administration | beneficial | Detrimental (“out of wind”) |

| Second wind | + | - |

| Polysaccharide stored | Glycogen | Glycogen + polyglucosan |

Clinically, McArdle disease is a pure myopathy because the lack of the muscle isozyme, which is also expressed in heart and brain, is amply compensated in these tissues by the much more abundant expression of the brain isozyme. In contrast, the genetic defect of the muscle subunit of PFK (PFK-M) results in a partial defect of PFK activity in erythrocytes, manifesting as compensated hemolytic anemia. Thus, hyperbilirubinemia and increased reticulocytes help in differential diagnosis.

More importantly, the “second wind” phenomenon, described by patients as the ability to resume exercising if they take a brief rest at the first appearance of undue fatigue, distinguishes GSD V from GSD VII, despite some reports to the contrary. In fact, Vissing and Haller have based a novel diagnostic test on the “second wind” phenomenon (8). Cycle exercise at a moderate, constant workload resulted in “second wind” (measured as decreased heart rate 7 to 15 minutes into exercise) in all 25 patients with McArdle but in none of 17 normal controls or 25 patients with other metabolic myopathies.

Yet another distinguishing feature described by Haller and Vissing is the opposite effect of glucose administration in the two diseases. Patients with McArdle disease benefit from glucose administration or from a sucrose load before exercise (9) because their metabolic block, which is far upstream in carbohydrate metabolism, impairs glycogen but not glucose utilization (Fig. 3). In contrast, meals rich in carbohydrate exacerbate the exercise intolerance of patients with phosphofructokinase (PFK) deficiency for two reasons: (i) due to the metabolic block downstream in glycolysis, their muscle cannot utilize either glycogen or glucose; (ii) glucose decreases the blood concentration of the alternative fuels FFA and ketones, a situation dubbed the “out of wind” phenomenon (10).

In 1980, while studying two patients with PFK deficiency, we noted, much to our surprise, that their muscle biopsies showed, in addition to deposits of normal-looking glycogen, pockets of an abnormal polysaccharide with the histochemical and ultrastructural features of polyglucosan (11): the polysaccharide was intensely PAS-positive but only partially digested by diastase and, in the electron microscope, consisted of finely granular and fibrillar material, similar to the amylopectin-like storage material of GSD IV (branching enzyme deficiency). Based on experiments in E. coli (12), we reasoned that the high concentration of glucose 6 phosphate (G6P) resulting from the metabolic block would activate glycogen synthetase abnormally and alter the normal ratio of glycogen synthetase (GS) to branching enzyme (BE) to the advantage of GS, thus favoring the synthesis of polysaccharide with excessively long and poorly ramified chains (polyglucosan). In a serendipitous but spectacular experiment, Raben et al. verified this mechanism when they overexpressed GS in the muscle of transgenic mice lacking acid maltase and observed massive accumulation of polyglucosan (13). The crucial role of the GS/BE ratio in the synthesis of normal glycogen has been confirmed in other conditions, such as cardiac glycogenoses due to defects in AMP-dependent protein kinase (AMPK) (14) and, possibly, in Lafora disease (this issue).

The pathogenesis of rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinuria in McArdle disease, as in other glycogenoses, remains unclear. There is no doubt that the block of aerobic glycolysis or, sometimes, anaerobic glycolysis during intense exercise results in an “energy crisis”. However, neither old biochemical determinations in muscle biopsies taken during an exercise-induced contracture (15) nor more recent 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopic studies during controlled exercise (1, 16) have ever revealed a critical decrease of ATP. This has led to the conclusion that probably the decrease of ATP is compartmentalized to ATP pools coupled to Na+ K+ ATPases or to Ca++ ATPases, a concept supported by the finding that sarcolemmal sodium pumps are decreased in McArdle muscle (17). This finding also explains the muscle inexcitability after repeated nerve stimulation observed many years ago in McArdle patients.

Over 40 mutations have been identified all along the gene (PYGM) encoding myophosphorylase. While by far the most common mutation in Caucasian patients is the R49X (Arg49Stop) mutation, it is important to keep in mind that the frequency of different mutations varies in different ethnic groups. For example, the R49X mutation has never been described in Japan, where a single codon deletion 708/709 seems to prevail (18). To complicate things further, it was documented that an apparently innocent polymorphism in the PYGM gene impaired cDNA splicing and was, in fact, pathogenic (19). This phenomenon, aptly dubbed “echo of silence” by Mankodi and Ashizawa (20), has to be taken into account in McArdle patients without clearly pathogenic mutations.

Genotype:phenotype correlations are not easily discernible, as patients with the same genotype (e.g. homozygous for the commonest mutation, R49X) may have very different clinical manifestations, varying from relatively mild exercise-related discomfort to almost crippling myalgia and recurrent myoglobinuria. Although these differences can be due in part to different lifestyles or dietary regimens, genetic must play a role. For example, rare cases of genetic “double trouble”, such as the coexistence in the same individual of homozygous mutations in PYGM and in the gene for adenylate deaminase, may explain more severe phenotypes (21, 22). Perhaps more importantly, screening for insertion/deletion polymorphism in the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) in 47 patients showed a good correlation between clinical severity and number of ACE genes harboring deletion (22).

I will briefly consider only one other glycogenosis causing exercise intolerance and myoglobinuria, phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM) deficiency (GSD X), in part for sentimental reasons, as my group discovered this enzyme defect in 1981 (23). Nine of the 13 patients identified thus far have been African American, and they all harbor one common nonsense mutation (W78X) either in homozygosity or in heterozygosity (Table 3). However, the disease is not confined to this ethnic group, and different mutations have been identified in Italian (24), Japanese (25), and most recently, Pakistani and Ashkenazi Jewish patients (Naini et al, unpublished observations).

Table 3. Main features of 14 patients with GSD X (PGAM deficiency).

| Sex/Age | Ethnicity | Clinical | Biopsy | Gene defect |

| M/52 | Afr..Amer. | Ex, Cr, Mg | ND | |

| F/17 | Afr. Amer. | Ex, Cr, Mg | W78X | |

| M/24 | Afr. Amer. | Ex, Cr, Mg | Tub. Aggr. | W78X |

| F/17 | Afr. Amer. | Ex, Cr | W78X | |

| M/30 | Afr. Amer. | Ex, Cr, Mg | W78X/E89A | |

| F/34 | Afr. Amer. | Ex, Cr, Mg | W78X | |

| F/36 | Afr. Amer. | Ex, Cr, Mg | W78X | |

| M/25 | Afr. Amer. | Ex, Cr, Mg | Tub. Aggr. | W78X |

| M/20 | Afr. Amer. | Ex, Cr, Mg | Tub. Aggr. | W78X |

| M/23 | Italian | Ex, Cr, Mg | R90W | |

| F/31 | Italian | Ex | R90W | |

| M/25 | Pakistani | Ex, Cr, Mg | Tub. Aggr. | R180X |

| M/55 | Japanese | Ex, Cr | G97A* | |

| M/22 | Japanese | Ex, Cr | G97A* |

There are two curious aspects of PGAM deficiency. The first is the frequency of manifesting heterozygotes, which is counterintuitive considering that PGAM is the glycolytic enzyme with the highest activity (26). The second peculiarity is that this enzyme defect is frequently associated with tubular aggregates (27). In isolation, these abnormal structures have been seen in patients with exercise intolerance, myalgia, or weakness, but they have also been associated with various disorders (including hypokalemic periodic paralysis and myotonia congenita) or with exposure to drugs or toxins (28). In frozen sections, they react strongly with the Gomori trichrome (mimicking ragged-red fibers) and with the NADH-tetrazolium reductase. Ultrastructurally, however, these predominantly subsarcolemmal aggregates do not contain mitochondria, but tubules derived from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), especially from the terminal cisternae near the junctions between the SR and the transverse tubules. Bundles of tubules, which are 50 to 80 nm in diameter and have a double membrane, often form hexagonal arrays. While there is no doubt about their origin from the SR, little is known about what triggers the formation of tubular aggregates, except that they seem to occur in response to abnormalities of excitation-contraction coupling and intracellular Ca++ flux regulation (28). Tubular aggregates have been described in four patients with PGAM deficiency and we have recently encountered a fifth patient in collaboration with Dr. Ashok Verma of the University of Miami. Thus, tubular aggregates seem to occur in PGAM deficiency more often than can be explained by chance, which may provide some clues as to their pathogenesis.

I will not consider in any detail the group of glycogenoses characterized by fixed weakness, which are listed in Table 4, because acid maltase deficiency (GSD II), branching enzyme deficiency (GSD IV), AMPK deficiency (a GSD still without a Roman numeral attribution), and Lafora disease (a glycogenosis sui generis, also without a Roman numeral label) each are discussed in separate chapters. I will only make a few considerations on debrancher deficiency (GSD III).

Table 4. Main features of the glycogen storage diseases (GSD) associated with fixed weakness.

| Enzyme GSD # | Non-muscle tissues affected | Isozyme or Subunit | Chromosomal location | Common mutations |

| α-glucosidase GSD IV | heart CNS liver |

17q23-q25 | IVS1-13t > g (Caucasian) Δ18 9 (Dutch) R854X (African-American) |

|

| Debrancher GSD III | liver heart |

1p21 | 4455delT (North African Jews) |

|

| Brancher GSD IV | liver heart brain (APBD) |

3p12 | Y329S (APBD) | |

| Aldolase GSD XII | RBC | Ald A | 16q22-24 | |

| TPI GSD XIV | RBC brain |

12p13 | ||

| Lafora disease | brain nerve muscle |

laforin | 6q |

The debrancher is a bifunctional enzyme, with two catalytic activities, oligo-1,4-1,4-glucantransferase and amylo-1,6-glucosidase. After phosphorylase has shortened the peripheral chains of glycogen to about four glycosyl units (this partially chewed up glycogen is called phosphorylase-limit dextrin [PLD]), the debrancher enzyme removes the residual “twigs” in two steps. First, a maltotriosyl unit is transferred from a donor to an acceptor chain (transferase activity), leaving behind a single glucosyl unit, which is then hydrolyzed by the amylo-1,6-glucosidase. The enzyme is encoded by a single-copy gene (AGL) on chromosome 1p21 (29).

Clinical presentations of debrancher deficiency vary depending on which tissues are affected and which enzymatic function is deficient (30). In the most common clinical variant (IIIa), the enzyme defect is generalized but liver and muscle are predominantly affected. In the rare variant IIIb, only liver is affected. The even less frequent variants IIIc and IIId are characterized by the selective defect of the glucosidase activity (IIIc) or of the transferase activity (IIId).

Patients with the IIIa variant typically present in childhood with hepatomegaly, growth retardation, hypoglycemia, and occasional seizures related to hypoglycemia. Symptoms tend to resolve spontaneously around puberty. Myopathy often appears in adult life, long after liver symptoms have subsided. Adult-onset myopathies have been distinguished into two groups, distal and generalized (31). Patients with distal myopathy develop atrophy of leg and intrinsic hand muscles, often suggesting the diagnosis of motor neuron disease or peripheral neuropathy (32). The course is slowly progressive and the myopathy is rarely crippling. Patients with generalized myopathy are more severely affected and often suffer from respiratory distress (31, 33).

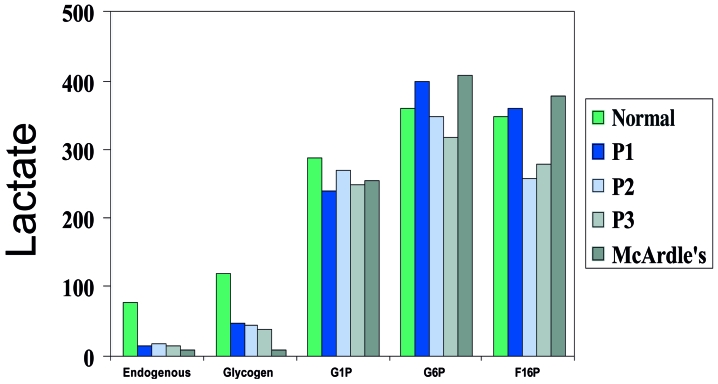

Although debrancher works in parallel with myophosphorylase, the symptoms of debrancher deficiency are very different from those of McArdle disease and cramps and myoglobinuria are exceedingly rare. One reason for this discrepancy may be that in McArdle disease glycogen cannot be broken down at all, whereas in GSD III, the most peripheral portions of normal glycogen can be utilized, as shown by lactate production in vitro (Fig. 4). However, for this minor “spare fuel” to work in vivo, one has to postulate a constant recycling of the peripheral chains between glycogen and PLD, while most of the stored glycogen in GSD III appears to be in the form of PLD.

Figure 4.

Comparative lactate production through anaerobic glycolysis in vitro by muscle homogenates from normal controls, 3 patients with debrancher deficiency (P1, P2, P3) and one patient with McArdle disease.

A more important explanation for the fixed, and mostly distal, weakness is the simultaneous involvement of muscle and nerve, as clearly documented both electrophysiologically and by nerve biopsy (34, 35).

Although the glycogenoses have been studied for almost one century (29), this Symposium documents how new enzyme defects are still being discovered, clinical variants of known defects are being described, pathogenetic mechanisms are incompletely understood, molecular studies have not provided clear genotype/phenotype relationships, and therapy is still woefully inadequate. Clearly, much remains to be done.

Acknowledgements

Part of this work has been supported by a grant from the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

References

- 1.Haller RG, Vissing J. Functional evaluation of metabolic myopathies. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, eds. Myology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. p. 65-79. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McArdle B. Myopathy due to a defect in muscle glycogen breakdown. Clin Sci 1951;10:13-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gambetti PL, Di Mauro S, Baker L. Nervous system in Pompe’s disease. Ultrastructure and biochemistry. J Neuropath Exp Neurol 1971;30:412-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JJ, DeBarsy T, Van Hoof F. Pompe’s disease: an inborn lysosomal disorder with storage of glycogen: a study of brain and striated muscle. Acta Neuropathol 1973;23:229-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roach PJ. Glycogen and its metabolism. Curr Mol Med 2002;2:101-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YT. Glycogen storage diseases. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, eds. The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001. p. 1521-51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Mauro S, Tsujino S. Nonlysosomal glycogenoses. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, eds. Myology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1994. p. 1554-76. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vissing J, Haller RG. A diagnostic cycle test for McArdle’s disease. Ann Neurol 2003;54:539-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vissing J, Haller RG. The effect of oral sucrose on exercise tolerance in patients with McArdle’s disease. New Engl J Med 2003;349:2503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haller RG, Lewis SF. Glucose-induced exertional fatigue in muscle phosphofructokinase deficiency. New Engl J Med 1991;324:364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agamanolis DP, Askari AD, Di Mauro S, et al. Muscle phosphofructokinase deficiency: Two cases with unusual polysaccharide accumulation and immunologically active enzyme protein. Muscle Nerve 1980;3:456-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyer C, Preiss J. Biosynthesis of bacterial glycogen: Purification and properties of Escherichia coli alpha-1,4-glucan:alpha-1,4-glucan 6 glycosyltransferase. Biochemistry 1977;16:3693-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raben N, Danon MJ, Lu N, et al. Surprises of genetic engineering: a possible model of polyglucosan body disease. Neurology 2001;56:1739-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arad M, Benson DW, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Constitutively active AMP kinase mutations cause glycogen storage disease mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 2002;109:357-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowland LP, Araki S, Carmel P. Contracture in McArdle’s disease. Arch Neurol 1965;13:541-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Argov Z, Bank WJ, Maris J, Chance B. Muscle energy metabolism in McArdle’s syndrome by in vivo phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neurology 1987;37:1720-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haller RG, Clausen T, Vissing J. Reduced levels of skeletal muscle Na+ K+-ATPase in McArdle disease. Neurology 1998;50:37-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsujino S, Shanske S, Goto Y, Nonaka I, DiMauro S. Two mutations, one novel and one frequently observed, in Japanese patients with McArdle’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 1994;3:1005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez-Cadenas I, Andreu AL, Gamez J, et al. Splicing mosaic of the myophosphorylase gene due to a silent mutation in McArdle disease. Neurology 2003;61:1432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mankodi A, Ashizawa T. Echo of silence. Silent mutations, RNA splicing, and neuromuscular diseases. Neurology 2003;61:1330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsujino S, Shanske S, Carroll JE, Sabina RL, Di Mauro S. Double trouble: Combined myophosphorylase and AMP deaminase deficiency in a child homozygous for nonsense mutations at both loci. Neuromusc Disord 1995;5:263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinuzzi A, Sartori E, Fanin M, et al. Phenotype modulators in myophosphorylase deficiency. Ann Neurol 2003;53:497-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Mauro S, Dalakas M, Miranda AF. Phosphoglycerate kinase deficiency: a new cause of recurrent myoglobinuria. Trans Am Neurol Assoc 1981;106:202-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toscano A, Tsujino S, Vita G, Shanske S, Messina C, Di Mauro S. Molecular basis of muscle phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM-M) deficiency in the Italian kindred. Muscle Nerve 1996;19:1134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hadjigeorgiou GM, Kawashima N, Bruno C, et al. Manifesting heterozygotes in a Japanese family with a novel mutation in the muscle-specific phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM-M) gene. Neuromusc Disord 1999;9:399-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Mauro S, Miranda AF, Olarte M, Friedman R, Hays AP. Muscle phosphoglycerate mutase deficiency. Neurology 1982;32:584-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh SJ, Park K-S, Ryan HF, et al. Exercise-induced cramp, myoglobinuria, and tubular aggregates in phosphoglycerate mutase deficiency. Muscle Nerve 2006;34:572-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.North C. Congenital myopathies. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, eds. Myology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2004. p. 1473-533. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Mauro S, Hays AP, Tsujino S. Nonlysosomal glycogenoses. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, eds. Myology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. p. 1535-58. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen J-J, Chen Y-T. Molecular characterization of glycogen storage disease type III. Curr Mol Medicine 2002;2:167-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiechl S, Kohlendorfer U, Thaler C, et al. Different clinical aspects of debrancher deficiency myopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 1999;67:364-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DiMauro S, Hartwig GB, Hays AP, et al. Debrancher deficiency: neuromuscular disorder in five adults. Ann Neurol 1979;5:422-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiechl S, Willeit J, Vogel W, Kohlendorfer U, Poewe W. Reversible severe myopathy of respiratory muscles due to adult-onset type III glycogenosis. Neuromusc Disord 1999;9:408-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Powell HC, Haas R, Hall CL, Wolff JA, Nyhan W, Brown BI. Peripheral nerve in type III glycogenosis: selective involvement of unmyelinated fiber Schwann cells. Muscle Nerve 1985;8:667-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ugawa Y, Inoue K, Takemura T, Iwamasa T. Accumulation of glycogen in sural nerve axons in adult-onset type III glycogenosis. Ann Neurol 1986;19:294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]