Summary

In Pompe disease, a deficiency of lysosomal acid alpha-glucosidase, glycogen accumulates in multiple tissues, but clinical manifestations are mainly due to skeletal and cardiac muscle involvement. A major advance has been the development of enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), which recently became available for Pompe patients. Based on clinical and pre-clinical studies, the effective clearance of skeletal muscle glycogen appears to be more difficult than anticipated. Skeletal muscle destruction and resistance to therapy remain unsolved problems. We have found that the cellular pathology in Pompe disease spreads to affect both the endocytic and autophagic pathways, leading to excessive autophagic buildup in therapy resistant muscle fibers of knockout mice. Furthermore, the autophagic buildup had a profound effect on the trafficking and processing of the therapeutic enzyme along the endocytic pathway. These findings may explain why ERT often falls short of reversing the disease process, and point to new avenues for the development of pharmacological intervention.

Keywords: Cardiomyopathies, Pompe disease

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) was recently approved for patients with Pompe disease, a devastating disorder affecting both infants and adults (1). The disease is caused by mutations in the acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA) gene, which encodes a lysosomal enzyme responsible for the degradation of glycogen. Clinical manifestations of the disease are extremely heterogeneous, and depend largely on the level of residual enzyme activity (2–4). In the most severe infantile form, complete or near-complete deficiency of the enzyme manifests as cardiomegaly, hypotonia, and mild hepatomegaly, resulting in death within the first year due to cardiorespiratory failure. Residual enzyme activity in milder late-onset variants spares cardiac involvement. The predominant manifestations of the late-onset form include slowly progressive proximal myopathy with respiratory muscle involvement; respiratory failure is the cause of significant morbidity and mortality.

The efficacy of ERT with recombinant human GAA (rhGAA) has been extensively studied in pre-clinical trials and in a relatively small group of Pompe patients with the most severe infantile phenotype. Infantile patients enrolled in the first clinical trials with alglucosidase alfa (Myozyme®; Genzyme Corp., Framingham, MA) survived significantly longer than expected for untreated patients because of greatly improved cardiac function, but only a small subset achieved significant improvement in skeletal muscle function and mortality was still high (5–8). Nine of seventeen infants enrolled in different trials died from disease complications (8). Thus, ERT has not been the magic medicine hoped for: skeletal muscle has turned out to be a difficult target.

Experiments in a knockout mouse model of Pompe disease with the replacement enzyme pointed to the same problem: poor response to therapy in skeletal muscle (9, 10). In mice, it quickly became apparent that type II skeletal muscle fibers are resistant to therapy (10). These fibers showed very modest glycogen reduction on high doses of the therapeutic enzyme despite the fact that in untreated mice, type II fibers accumulated much less glycogen compared to cardiac and type I – rich muscle. Thus, paradoxically, the effectiveness of therapy does not wholly depend on the amount of storage material.

Therefore we explored the differences between glycolytic fast-twitch type II and oxidative slow-twitch type I fibers. We have found differences in the distribution of lysosomes in both wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) fibers: in type I fibers, the lysosomes are lined up and appear connected, while in type II fibers the lysosomes are randomly distributed and do not touch. We have also found that type II fibers have lower levels of the proteins involved in endocytosis and lysosomal targeting of the therapeutic enzyme, such as the cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (10, 11). This receptor, located in the cytosol and on the cell surface, is responsible for the uptake of the recombinant enzyme and its delivery to the late endocytic compartment.

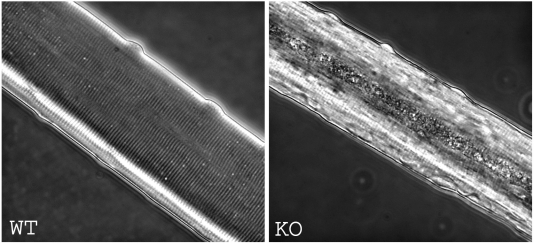

While these fiber-type specific properties may contribute to the differential response to therapy, the “elephant in the room” was the presence of large areas of autophagic buildup in type II fibers. In type I fibers, one can see enlarged lysosomes, as is typical of Pompe disease, but only in Type II fibers can one also see huge areas of autophagic activity, as shown by electron microscopy (10, 11) (Fig. 1). Although noted many years ago (12), the presence of autophagy has largely been ignored. It’s actually surprising that autophagy was not directly linked to the pathogenesis of the disease. After all, the lysosome is the endpoint for both the endocytic pathway – the route of the recombinant enzyme to the lysosome, and the autophagic pathway.

Figure 1.

Electron microscopy of type I and type II fibers from a 9 month-old knockout mouse showing the presence of autophagic buildup in type II fiber.

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved pathway of lysosomal degradation and recycling of long-lived proteins and damaged organelles (13), which maintains intracellular balance between biosynthetic and catabolic processes and is a critical survival mechanism under conditions of nutrient deprivation. Autophagy involves the formation of a double-membrane vesicle, which engulfs part of the cytoplasm and damaged organelles and then fuses with a lysosome where the content of the vesicle is degraded. These double-membrane vesicles, known as autophagosomes, can be detected by staining with a highly specific marker, LC3 (14). Under normal conditions of productive autophagy, autophagosomes are quickly degraded by the lysosomes, and LC3-positive structures are barely detectable.

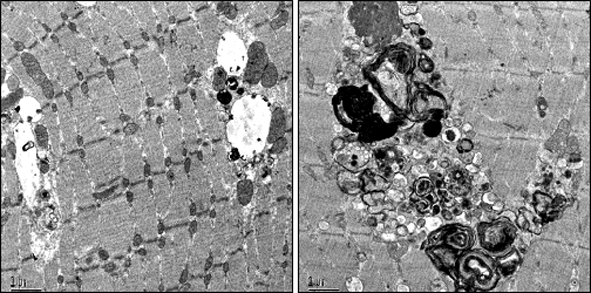

To study the geographic distribution of the autophagic structures seen by electron microscopy in knockout fibers, we isolated single muscle fibers, and stained them with LC3 as well as with lysosomal membrane protein LAMP1, which stains both late endosomes and lysosomes. Strikingly, the autophagic areas were huge, extending almost the full length of the fiber, and were often located in the center of the fiber. Once recognized, the autophagic areas could be clearly seen in fixed or live fibers without any staining by low resolution transmitted light microscopy (Fig. 2). In some fibers, the volume occupied by the autophagic buildup reached 40% of the total volume of the fiber (15).

Figure 2.

Autophagic area could be observed in type II fibers by low resolution transmitted light microscopy. Live cultured myofibers from predominantly type II gastrocnemius (pale) muscle of 2.5 month-old WT and KO mice.

Confocal microscopy of immunostained KO single muscle fibers has revealed the presence of multiple LC3-positive autophagosomes, LAMP1-positive late endosomes and lysosomes, as well as LC3/LAMP1 double-positive structures. The abundance of LC3-positive and LC3/LAMP1 double-positive structures indicates the failure of the lysosomes to fuse with and degrade the content of autophagosomes. Excessive clustering of the vesicles of the autophagic and endocytic pathway, as well as the accumulation of intralysosomal and extralysosomal undigested material, have profound effects on muscle architecture (11, 15).

The increase in autophagy can be detected very early – it is seen in fibers from one-month old KO mice – well before symptomatic disease. Interestingly, at this early stage it is not uncommon to find small damaged lysosomes inside the autophagosome. In an unusual role reversal it appears that the autophagosome engulfs the lysosome. Since one of the functions of autophagy is the elimination of damaged organelles, it is possible that the presence of damaged lysosomes triggers the increase in autophagy. If this hypothesis is true, the damage to the lysosomes may occur very early when the lysosomes are still small.

As the disease progresses, the autophagic buildup appears to interrupt muscle striation, as demonstrated by immunostaining of single muscle fibers for myosin, a structural muscle protein. There is also an indication of oxidative stress as evidenced by progressive accumulation of lipofuscin in muscle fibers, even from young animals. Autofluorescent material in the KO myofibers is concentrated nearly exclusively in the autophagic areas. Enhanced deposition of lipofuscin and large areas of centrally located cellular debris were observed in muscle biopsies of another mouse model of Pompe disease (16). Lipofuscin, an autofluorescent material composed of oxidatively modified macromolecules, normally accumulates in lysosomes of postmitotic cells during aging, but abnormal increase of lipofuscin was shown to be associated with oxidative damage (17).

The autophagic buildup grows with age, and seems to have a greater effect on muscle architecture than the expanded lysosomes outside the area. As mentioned above, autophagic areas contain multiple vesicular structures in fibers from younger mice. In contrast, in old mice (beyond 20 months of age) the integrity of the vesicles in the autophagic areas appears lost and only remnants of vacuolar membranes can be visualized. This stage most likely represents the point of no return because so little of the muscle structure is intact. Furthermore, at this stage, the autophagic areas are totally devoid of the mannose 6-phosphate receptor, making the delivery of the therapeutic enzyme impossible (11).

The relevance of the studies in a murine model of the disease is underscored by the presence of increased autophagy in muscle fibers from patients with Pompe disease.

In humans we see many of the same things that were observed in mice. Autophagy appears to be a big player in the pathogenesis of the disease. The autophagic areas which begin at multiple points along the fiber eventually expand, come together, and totally replace muscle tissue. In some fibers, the expanded lysosomes outside the area of autophagy look like innocent bystanders (18).

What do these findings have to do with the problem we set out to solve – the failure of recombinant enzyme to clear skeletal muscle cells of glycogen? It is reasonable to assume that the autophagic buildup may affect the trafficking of the therapeutic enzyme even at early stages when the vesicular structure of the autophagic areas is preserved. This assumption is based on experimental evidence indicating that the endocytic and autophagic pathways can converge upstream from lysosomes: autophagosomes can fuse with late endosomes or even early endosomes. Thus, the therapeutic enzyme, which moves along the endocytic pathway from early to late endosomes and then to lysosomes, may be mis-targeted and end up in autophagosomes.

This hypothesis has been confirmed experimentally. To address the issue of rhGAA trafficking in skeletal muscle we have used a unique experimental system – analysis of endocytosis of labeled recombinant enzyme in live cultured myofibers. We have demonstrated that the endocytosed therapeutic enzyme in the KO fibers accumulates along the length of the fibers, primarily in the vesicular compartments of the autophagic areas. The recombinant enzyme, trapped in these areas, is mostly wasted since it is diverted from glycogen-filled lysosomes in the rest of the fiber, but is unable to resolve the autophagic buildup (11), which continues to expand as the disease progresses. Thus, autophagy sets up the conditions for the disruptive buildup and diversion of recombinant enzyme away from lysosomes (19).

The data from both mouse model and human studies led us to reconsider the view of the pathogenesis of the disease and the mechanisms of skeletal muscle damage.

The current view, put forward more than 20 years ago, is that muscle damage occurs because unlike in other cells, lysosomes in muscle cells have a limited space in which to expand, resulting in mechanical pressure, and rupture (20, 21). According to this hypothesis, the disease progresses through multiple stages: glycogen begins to accumulate in lysosomes, which gradually increase in size and number leading to rupture of the lysosomal membrane, and allowing spilled glycogen to float into the cytoplasm. Later stages are characterized by complete replacement of contractile elements by spilled cytoplasmic glycogen.

This hypothesis does not take into consideration abnormalities in multiple other vesicles of the lysosomal-degradative system, and specifically, those involved in autophagy. We are not arguing with the idea of vesicular rupture, and in fact, at later stages we do see the disintegration of the vesicular membranes. However, the stages leading to this final point are at odds with our experimental evidence, both in an animal model and in humans; the data strongly indicate that it is not the global expansion of the lysosomes which cause skeletal muscle damage, but rather some yet unknown abnormalities in a subset of lysosomes which do not allow them to recycle autophagosomes and their content.

References

- 1.Reuser AJ, Van den Hout H, Bijvoet A, et al. Enzyme therapy for Pompe disease: from science to industrial enterprise. Eur J Pediatr 2002;161:106-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engel AG, Hirschhorn R, Huie ML. Acid Maltase Deficiency. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, eds. Myology. Third Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. p. 1559-86. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reuser AJ, Kroos MA, Hermans MM, et al. Glycogenosis type II (acid maltase deficiency). Muscle Nerve 1995;3:61-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kishnani PS, Steiner RD, Bali D, et al. Pompe disease diagnosis and management guideline. Genet Med 2006;8:267-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Hout JM, Kamphoven JH, Winkel LP, et al. Long-term intravenous treatment of Pompe disease with recombinant human alpha-glucosidase from milk. Pediatrics 2004;113:448-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkel LP, Kamphoven JH, Van Den Hout HJ, et al. Morphological changes in muscle tissue of patients with infantile Pompe’s disease receiving enzyme replacement therapy. Muscle Nerve 2003;27:743-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klinge L, Straub V, Neudorf U, Voit T. Enzyme replacement therapy in classical infantile pompe disease: results of a ten-month follow-up study. Neuropediatrics 2005;36:6-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kishnani P, Nicolino M, Voit T, et al. Chinese hamster ovary cell-derived recombinant human acid alpha-glucosidase in infantile-onset Pompe disease. J Pediatr 2006;149:89-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raben N, Danon M, Gilbert AL, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy in the mouse model of Pompe disease. Mol Genet Metab 2003;80:59-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raben N, Fukuda T, Gilbert AL, et al. Replacing acid alpha-glucosidase in Pompe disease: recombinant and transgenic enzymes are equipotent, but neither completely clears glycogen from type II muscle fibers. Mol Ther 2005;11:48-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda T, Ewan L, Bauer M, et al. Dysfunction of endocytic and autophagic pathways in a lysosomal storage disease. Ann Neurol 2006;59:700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engel AG. Acid maltase deficiency in adults: studies in four cases of a syndrome which may mimic muscular dystrophy or other myopathies. Brain 1970;93:99-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death Differ 2005;12:1542-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J 2000;19:5720-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuda T, Roberts A, Ahearn M, et al. Autophagy and lysosomes in Pompe disease. Autophagy 2006;2:318-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hesselink RP, Schaart G, Wagenmakers AJ, Drost MR, van der Vusse GJ. Age-related morphological changes in skeletal muscle cells of acid alpha-glucosidase knockout mice. Muscle Nerve 2006;33:505-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terman A, Brunk UT. Oxidative stress, accumulation of biological ‘garbage’, and aging. Antioxid Redox Signal 2006;8:197-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raben N, Takikita S, Pittis MG, et al. Deconstructing Pompe disease by analyzing single muscle fibers: to see a world in a grain of sand. Autophagy 2007;3: in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuda T, Ahearn M, Roberts A, et al. Autophagy and Mistargeting of Therapeutic Enzyme in Skeletal Muscle in Pompe disease. Mol Ther 2006;14:831-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin JL. Infantile acid maltase deficiency. I. Muscle fiber destruction after lysosomal rupture. Virchows Arch (Cell Pathol) 1984;45:23-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thurberg BL, Lynch MC, Vaccaro C, et al. Characterization of pre- and post-treatment pathology after enzyme replacement therapy for pompe disease. Lab Invest 2006;86:1208-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]