Abstract

Epidemiological data provide strong evidence for a relationship between undernutrition and life-threatening infection in infants and children. However, the mechanisms that underlie this relationship are poorly understood. Through foetal life, infancy and childhood, the immune system undergoes a process of functional maturation. The adequacy of this process is dependent on environmental factors, and there is accumulating evidence of the impact of pre- and post-natal nutrition in this regard. This review outlines the impact of nutrition during foetal and infant development on the capacity to mount immune responses to infection. It provides an overview of the epidemiologic evidence for such a role and discusses the possible mechanisms involved.

Keywords: malnutrition; foetal nutrition disorders; neonatal immunity, maternally acquired; immunity; mucosal; immune disorders

The neonatal immunodeficiency

Upon delivery, the developing neonatal immune system is transferred from the relatively sterile confines of the uterus to an environment teeming with countless antigenic challenges. It must quickly gain competence in identifying and destroying pathogens, whilst maintaining tolerance to self tissues, and to a huge range of harmless food and environmental antigens. At birth, neonates are susceptible to infection because of a functional immaturity of the immune system that spans most areas of host defence.

Mucosal and epithelial surfaces form the first line of defence against infection but are less developed in the neonatal period (1). Antigen-presenting cells in lymphoid accumulations in the foetal gut express markers of maturation and costimulatory molecules from as early as 14–16 wk gestation. They are seen in close apposition with T cells within lymphoid accumulations in the small intestine, which exhibit capping of receptors, suggesting that primary sensitization is occurring (2, 3). However, the ontogeny of the gut-associated lymphoid tissues is structurally incomplete, and its further development is highly dependent on microbial colonization in the early post-natal period (4, 5).

Several factors severely compromise the neonatal innate immune system’s response to pathogenic challenge. Circulating levels of complement proteins are low, and neutrophils display impaired chemotactic, phagocytic and microbicidal capabilities (6, 7). Macrophage activation by cytokines and Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands is also impaired (8), although NK cells, which are present in large numbers in cord blood samples, express high levels of activating receptors, implying effector functions that may be in excess of adult levels (9).

It has long been recognized that in the neonatal period, the antimicrobial effector function of the adaptive arm of the immune system is attenuated. The system adopts a fundamentally tolerogenic posture so as to avoid inappropriate reactivity to common and harmless antigens during the experiential acquisition of antigen-specific memory (10). Consequently, cell-mediated immunity to infectious pathogens is inefficient in the neonatal period (11, 12). However, this is not because of some intrinsic immaturity in lymphocyte function. Indeed, whilst low baseline expression of T-cell receptor (TCR), adhesion molecules and CD40L, and inefficient cytokine generation certainly diminish T-cell responsiveness (13), neonatal T cells are able to demonstrate a relatively complete repertoire of effector functions (14). As early as 28 wk gestation, the foetus is able to mount an antigen-specific CD8+ response to intrauterine viral infection, although these cells may not have a full repertoire of effector functions (15, 16), and antigen-specific T-cell proliferation has been demonstrated at similar gestational ages in response to environmental allergens (17). The inadequate response to pathogenic challenge is partly explained by a bias towards Th2-type responses at the expense of Th1 effector mechanisms important in fighting infection. This bias is crucial for continued maternal acceptance of the foetus and is partly mediated by placental factors (18). It also helps to facilitate the proper acquisition of tolerance to innocuous antigens and resolves gradually through infancy and childhood, as the adaptive immune system becomes more competent at fighting infection (19). Th2 dominance is supported by differences in antigen presentation and in the balance of regulatory lymphocytes. Antigen presentation by circulating cells is inefficient at birth, with cord blood monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells expressing low levels of costimulatory molecules and demonstrating inefficient TLR-mediated signalling alongside abnormalities in maturation and cytokine production (20). Additionally, foetal blood, thymus and lymphoid organs contain large numbers of functional Treg cells, which exhibit a powerful suppressant effect over the foetal immune system (21).

Breast milk and immunity to infection

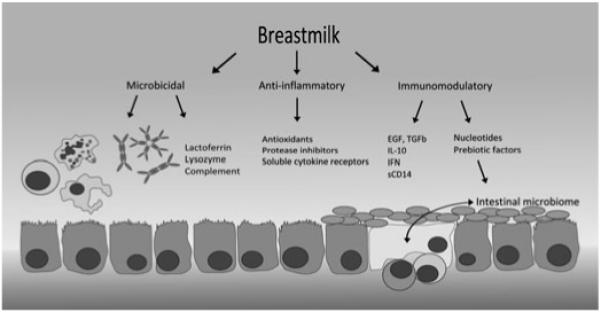

The neonatal immune system is considerably bolstered by factors present in breast milk (see Figure 1). Epidemiological studies have demonstrated lower infant mortality for breastfed infants in both the Developing and Developed World, with less morbidity from diarrhoeal disease, respiratory infections, otitis media and urinary tract infections, effects which are consistent in small for gestational age babies as well as those of normal birthweight (22). There are very few instances in which breastfeeding is absolutely contraindicated, although rates of breastfeeding continuation – especially in the developed world – are often far below the WHO target of exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life (23, 24).

Fig. 1.

Breast milk is immunologically active at the infant’s intestinal mucosa. Microbicidal factors include activated lymphocytes and phagocytes, secretory IgA and IgM, complement and other antimicrobial peptides and lipids, all of which provide broad immune activity against gut pathogens. Maternal IgG from cross-placental transfer provides further support, and the antimicrobial properties of breast milk are complemented by an anti-inflammatory activity, which downregulates damaging inflammation within the mucosa. Direct immunomodulatory factors include cytokines and growth factors, some of which interact directly with the mucosal epithelium, and others that have more distant targets (IL-7 targets the thymus – not shown). Pre-biotic factors including acidic and neutral oligosaccharides facilitate the growth of a healthy intestinal microbiome, and crosstalk between gut commensals, mucosal immune tissue (shown in yellow), and immunomodulators in breast milk help to drive tolerance to harmless antigens.

Breast milk contains a range of substances that demonstrate direct antimicrobial activity. These include lactoferrin, which chelates iron and has bacteriostatic and bactericidal activities, lysozyme, which causes bacterial cell wall lysis and binds endotoxin, defensins, soluble CD14, antiviral lipids and complement proteins. It also contains a variety of factors that are anti-inflammatory in nature, including antioxidants such as vitamins A and C, protease inhibitors and anti-inflammatory cytokines. This mixture facilitates the activity of a wide range of antimicrobial factors at the infant’s mucosal surface independently of their own mucosal immune system, providing broad protection from enteric infection whilst suppressing immune activation in the mucosa itself, where a fine balance of pathogenic and tolerogenic influences direct the development of a mature and experienced immune system. This multifunctional role is reinforced by directly immunoactive factors in breast milk such as hormones, IL-10, interferon and epithelial growth factor (EGF). EGF has been demonstrated to act directly on gut epithelium, decreasing permeability to infectious agents (25). Breast milk is also rich in nucleotides and nucleosides. These have been shown to augment infantile NK cell activity and humoral responses in some cases and may confer limited protection against diarrhoea (26).

In the first few months of life, the neonatal immune system is supported by maternal IgG, which is actively transported across the placenta during the third trimester and often reaches higher levels in cord blood than in the maternal circulation. During breastfeeding, this passive ‘adaptive’ arm of the immune system is further supplemented by activated leucocytes and secretory immunoglobulin (27). By virtue of the maternal mucosal immune system, a proportion of these immune constituents will be directed against known environmental and enteric antigens, and thereby give dynamic and environmentally specific immune protection (28, 29).

Consideration of the nutritional status of lactating mothers is important, as the concentration of some micronutrients in breast milk, notably the B vitamins, vitamin A and iodine, are directly correlated with maternal values (30). Maternal deficiencies can be demonstrated to contribute to specific deficiencies in their infants (31). Micronutrient deficiencies can lead to compromise in immune function, as will be discussed later. In addition, maternal undernutrition is associated with differential levels of breast milk antimicrobial factors, and with decreased IL-7 levels, which may impact on the development of the infant’s immune capabilities (32).

Immunity and intestinal flora

Soon after delivery, the sterile infant intestinal tract becomes colonized by bacteria, mostly from maternal faecal flora (33). The balance of this colonization is affected by the mode of delivery and the infant’s diet. Caesarean section delivery denies the neonate the inoculum of organisms from the maternal gut. In breastfed babies, Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli quickly become dominant, whereas in formula-fed babies, Bacteroides species are present in large numbers, alongside other bacteria known to be enteric pathogens (34, 35). Breast milk contains high concentrations of oligosaccharides, which ferment in the bowel and promote the growth of Bifidobacterium gut commensals. Other nutrients have similar pre-biotic effects, including casein, alpha-lactalbumin, lactoferrin and nucleotides (22, 35). Non-pathogenic commensal bacteria are protective against infection via a number of mechanisms including competitive inhibition of epithelial binding by enteropathogenic bacteria and effects on tight junctions (36). In the neonate, a healthy gut flora may also be critical to the development of a properly functioning mucosal immune system. Crosstalk between enteric bacteria and TLRs in the intestinal mucosa can modulate the level of immune activation in the gut and direct towards either Th1 or Th2 type responses (37, 38). Lactobacilli prime dendritic cells to drive the development of Treg cells and to promote mucosal tolerance to non-pathogenic antigens (39).

Specific variations in intestinal flora have been shown to be associated with differential development of atopy (40, 41), but the role of artificially modulating the infant’s intestinal microbiome through the use of pro- or pre-biotic supplements to effect immunological outcomes is unclear. Whilst both probiotic and pre-biotic supplementations for formula-fed infants has been shown to lead to ‘healthier’ gut flora, rich in Bifidobacteria and depleted of known pathogenic enterobacteria (42-44), clinical outcomes have been inconsistent.

Probiotic supplementation in infancy results in shorter and less frequent episodes of diarrhoea (45-48), as well as a reduction in the incidence of lower respiratory tract infections (49, 50). However, the effects are small, and results of other trials have been inconsistent (51). The possibility that probiotic supplements may influence the development of atopy is still contested (52). Maternal probiotic consumption around birth can modify infantile gut flora (53-55), and supplementation alters immunomodulatory properties of breast milk (56), although effects on the foetal and neonatal immune system may be limited (57).

A single trial of pre-biotic-enriched complementary food in Peru failed to demonstrate a reduction in episodes of infectious diarrhoea, utilization of healthcare resources, or vaccine responsiveness (58). However, another study has demonstrated that pre-biotic supplementation leads to increased levels of sIgA in stool – more so than probiotic supplementation (59), and two recent trials of pre-biotic supplemented milk in European infants have demonstrated decreased incidence of gastrointestinal and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections (60, 61). Maternal consumption of pre-biotic oligosaccharides modified maternal gut flora but failed to alter that of the neonate and did not lead to significant differences in neonatal immune status as demonstrated by in vitro cord blood immunological parameters (62).

Pre- and perinatal nutrition

Childhood malnutrition (or protein-energy malnutrition, PEM) is associated with increased incidence and case fatality rates of common illnesses such as diarrhoea and pneumonia, and amongst children, this malnutrition-attributable risk of infection accounts for more than half of global mortality (63, 64). Malnutrition and infection exist in a vicious cycle, with infectious episodes contributing directly to growth faltering and the diversion of essential nutrients (65), whilst malnutrition impedes immune responsiveness by a number of different pathways. Mucosal barrier function, the first line of host defence is inefficient, leading to ingress of pathogens and systemic inflammation (66). Complement activation is reduced, phagocytic cells are compromised, and antibody production is deficient (67). The number of circulating lymphocytes is low, T cells express low levels of activation markers and the proportion of T cells with a memory phenotype is reduced (68). The number of circulating dendritic cells is also reduced, and a recent study demonstrated reduced dendritic cell IL-12 production in half of a cohort of severely malnourished children (69).

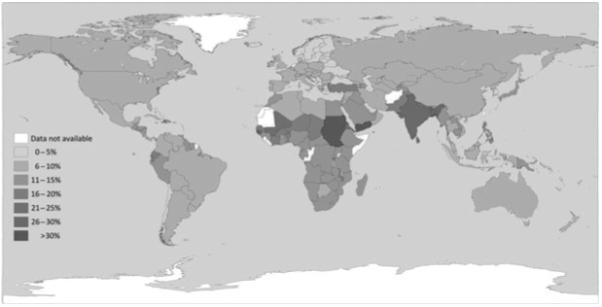

The relationship between maternal nutrition and foetal growth is complex. Foetal growth is modulated by a large range of factors including maternal metabolic and endocrine function, placental function, as well as the availability of nutrients (70). However, maternal PEM during pregnancy can lead to low birthweight (71, 72) via effects on gestational length and, especially, through the association with delivery of small-for-gestational-age babies (SGA), who may be thought of as an analogue of malnourished infants and share their increased infection risk (73-75) (see Figure 2). In the West, SGA infants typically experience a phase of rapid catch-up growth over the first few weeks of life but whether or how this is manifest in the context of dietary insufficiency is unclear. Understanding the links between maternal malnutrition, SGA and infantile malnutrition is hampered by an inadequate evidence base. Notably, there are no published anthropometric criteria for severe malnutrition under 6 months of age, and little research has been carried out on the treatment of malnutrition in this age group. A large retrospective analysis of growth rates amongst children in Developing World found that ‘wasting’ did not occur until late in infancy, but faltering in terms of length occurs from birth (76). However, the clinical correlates of this pattern are unclear. In 2004, a WHO technical review committee found that ‘no new research was identified pertaining to the optimum dietary management of severely malnourished infants aged <6 months. The evidence base for defining the most advantageous formulations for feeding this age remains weak’ (77).

Fig. 2.

Percentage of low birthweight infants by country. Data from UNICEF/WHO (78).

Whilst the burden and immediate impact are largely unknown and current clinical management is unstructured, there is evidence that malnutrition during infancy may lead to permanent structural and functional changes in the developing immune system (79, 80). Cohort studies from the Gambia have demonstrated that being born in the ‘hungry season’ is associated with reduced thymic size and function (32), with elevated levels of CD8+ve T cells and NK cells that persist through the first year independent of current nutritional status (81), and is strongly associated with risk of death from infection in adolescence and early adulthood (79). Similarly, correlations between birthweight and functional responses to vaccines administered in adolescence have been described in Pakistan and in the Philippines (82, 83), although such observations have not been universal (84).

Furthermore, limited data suggest that nutritional status can exert transgenerational effects. In murine studies, a period of maternal malnutrition during gestation leads to permanent immunodeficiency in the offspring that is not amenable to correction by optimal feeding during infancy. The offspring of these mice also demonstrate abnormalities in immune function, especially if grandmaternal malnutrition incorporates zinc deficiency (85, 86). Some observational studies of famine-exposed populations have shown a similar effect (87), and there is growing interest in the role of foetal and prenatal programming of immune function. Such transgenerational phenomena have been well documented in other areas, as grandmaternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with increased levels of asthma irrespective of maternal smoking status (88). They may represent modulation by epigenetic mechanisms and are a source of significant interest at present (89).

Micronutrient malnutrition

Alongside protein-energy nutrition, micronutrient status is an important determinant of immune function. Different micronutrients have numerous roles in immune responses, and individual micronutrient deficiencies can lead to immunocompromise in infants.

Iron deficiency is associated with impairment of neutrophil and NK cell-mediated killing and T-cell proliferative responses and tends to bias the immune response towards the Th2 type (90). However, iron supplementation for infants and children remains controversial. Iron is an essential nutrient for pathogens as well as humans. Bacterial proliferation is impaired by environmental iron depletion, for example because of the actions of lactoferrin in the gut, and mild iron deficiency may be protective against malaria (91). In two large recent studies of routine iron and folate supplementation for children younger than 3 yr old, supplementation was associated with an increased risk of infectious morbidity and mortality confined to those living in an area of intense malarial transmission (92, 93). In non-malarial areas, routine supplementation carried no such increased infection risk, and in the Pemba trial, it was probably confined to a subgroup who were already iron replete at enrolment (94). In populations with high levels of anaemia, routine supplementation has been associated with positive effects on cognitive performance and other long-term outcomes (95). However, the evidence points to a degree of risk associated with routine iron supplementation and with the early administration of iron to subjects who may have infection as well as malnutrition (96). Current WHO guidelines restrict iron supplementation in malnourished children until a course of broad-spectrum antibiotics has been instituted, and appetite has started to return. During pregnancy, it is recognized that iron delivery to the foetus is preserved even in the face of maternal iron-deficient anaemia, allowing sufficient stores to be established to last until weaning. However, maternal iron deficiency during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of deficiency in the infant at 6 and 9 months (97), and strategies to optimize iron nutriture during infancy remain the subject of investigation (98).

Zinc deficiency is associated with lymphopenia and impaired lymphocyte function including a bias towards Th2 responses, thymic atrophy and distortion of the cell-mediated immune response, which are corrected by appropriate zinc supplementation (90, 99). Zinc deficiency is probably very common, affecting up to a third of the World’s population, especially in the context of protein-energy malnutrition (99), and it has proved an important nutrient for immunity in children. A recent systematic review of zinc supplementation amongst children with diarrhoea demonstrated a significant reduction in length of the diarrhoeal episode (100), and supplementation is recommended as part of routine diarrhoea management by WHO. However, in infants < 6 months old, the benefits are less clear, and a recent trial even demonstrated increased diarrhoeal duration (101). Amongst children with pneumonia, there are conflicting data on the effect of zinc supplementation, with two trials demonstrating hastened recovery, but the most recent showing no effect – and a possibility of harm for those children with the most severe infections (102-104). Routine supplementation with zinc has failed to show significant effects on mortality in infants less than a year old (105-107), although there are probably beneficial effects in decreasing incidence of infections (108), which may be especially important amongst children born at low birthweight (109). Zinc homoeostasis in the infant is affected by gestation, birthweight and feeding method, but accurately predicting zinc status based on the current evidence is difficult (110). Other recent work from Africa has emphasized that effects observed in Asia, where many zinc trials have been carried out, may not be uniform across different Developing World communities (111).

Vitamin A has a diverse range of roles in effective immune responses. It is important in maintaining the integrity of mucosal surfaces, and deficient states are associated with increased rates of invasive respiratory, gastrointestinal and ocular infections. Deficiency also interferes with phagocytic and NK cell function, and with both Th1 and, especially, Th2 responses. Routine supplementation trials have demonstrated improvements in measles and diarrhoeal disease morbidity (112-114) and decreased incidence of malaria (115), although they have largely failed to demonstrate a positive effect on respiratory disease morbidity, and supplementation may even increase the rate of respiratory infection (116). Studies assessing the survival benefit of supplementation have suggested that modest benefit exists, although it may be highly time dependent; routine supplementation for infants <6 months appears to be expeditious only in the very early neonatal period, and benefit in African populations is less apparent than in those from south Asia (117).

Vitamin D has diverse immunologic effects, including the promotion of Th2 and regulatory T-cell signalling as well as increasing the antimycobacterial properties of monocytes and macrophages (118). It has long been recognized that children with rickets have increased susceptibility to respiratory tract infections, and recent epidemiological work has hinted at the importance of subclinical deficiency in this regard, with several studies reporting increased pneumonia incidence associated with vitamin D insufficiency (119). In a very large retrospective cohort analysis, vitamin D levels were inversely correlated with self-reported recent respiratory infection (120). Vitamin D was used as a treatment for tuberculosis (TB) in the pre-antibiotic era, and interest in its anti-TB properties has recently been revived. A study of adult TB contacts in London found that a single dose of oral vitamin D significantly improved antimycobacterial whole blood innate immune indices (121), contributing to an accumulating evidence base for the use of vitamin D supplementation in active TB (122). Whilst a recent trial of supplementation in Guinea Bissau showed no overall effect, it may have suffered from underdosing the supplement (123). Subclinical vitamin D deficiency is probably very common in all parts of the World, and infants are highly vulnerable. Foetal vitamin D stores are highly dependent on maternal nutritional sufficiency, and breast milk is poor in vitamin D even from vitamin replete mothers (124). At present, the scale of the problem of subclinical vitamin D deficiency in infants is not clear, and the potential roles of supplementation both in routine care and as an adjunct to TB or pneumonia treatment have not been tested.

Other micronutrients have important effects on the developing immune system. Selenium deficiency is associated with the development of atopic features and of poor cell-mediated immunity including increased risk of viral infections and rapid progression of HIV (125-127). Copper, manganese, the antioxidant vitamins C and E and other nutritional factors are also important for immune function.

The relative clinical importance of different micronutrient deficiencies is difficult to ascertain. Subsistence diets in low or middle income countries where the effects of nutritional deficiencies are most pressing are often deficient in multiple micronutrients. These multiple deficiencies are likely to have a cumulative effect on immunity to infection that is difficult to control for in trials of the supplementation of single micronutrients. Additionally, single micronutrient deficiencies or excess can impact on the absorption and bio-availability of other micronutrients, and there are many examples of how dietary supplementation can inadvertently have negative impacts on global micronutrient status. An additional problem in assessing the clinical importance of different deficiencies is that interventional studies have not typically incorporated detailed assessment of individual subjects’ nutritional status at either initiation or completion because of logistical and ethical concerns, and the generalizability of outcomes across different populations is questionable.

The effect of these problems is that clear dose–response relationships for the effect of individual micronutrients on immune function have proved impossible to ascertain, and their relevance to real-world scenarios in which a complex web of nutritional deficiencies co-exist is questionable. As a result, the research agenda and public policy discourse are shifting towards the provision of balanced multiple micronutrient supplementation. There has been particular interest in the development of a balanced micronutrient supplement for use during pregnancy (128). Pregnancy constitutes a significant metabolic and nutritional burden for women, especially those in the Developing World, and the foetus is sensitive to micronutrient depletion, leading to low birthweight independent of protein-energy status (129, 130). So far, the effects of such supplementation remain controversial.

A recent systemic review of trials of supplementation during pregnancy failed to demonstrate an effect of multiple micronutrients on reducing the frequency of low birthweight or perinatal mortality more than the effect of iron and folate supplementation, which is WHO routine antenatal care (131). However, several more recent trials have reported reduced rates of low birthweight deliveries, raising hopes of improvements in neonatal health (132-135). Indeed, a large trial in Indonesia involving more than 30000 pregnancies of a micronutrient supplement during pregnancy and 90 days post-partum showed positive results: The mortality rate during early infancy was decreased by 18% in the multiple micronutrient group compared to iron and folate alone (136). However, two large trial cohorts in Nepal comparing antenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation versus iron and folate or other less complete supplements have demonstrated strikingly different results. Both groups, based in Sarlahi district and Janakpur, respectively, reported modest improvements in birthweight with percentage decreases in the rate of low birthweight of 14% and 25% (137, 138), but a combined analysis showed significantly increased perinatal and neonatal mortality rates with multiple micronutrient supplementation, with relative risks of 1.52 and 1.36, respectively (139, 140). This effect may partly be explained by larger birthweights leading to increased levels of birth asphyxia, the rate of which was increased by 60% in the Sarlahi trial and which was associated with 8- to 14-fold increases in mortality at 6 months if it occurred alongside prematurity or sepsis (141). However, the Janakpur trialists have recently reported improvements in weight at 2.5 yr in the micronutrient intervention group, emphasizing the current uncertainty surrounding this area (142). A further similar study from China has also demonstrated a very modest increase in birthweight with micronutrients versus iron and folate, not associated with any improvement in neonatal mortality (143).

Lipid malnutrition

Dietary lipids have immunomodulatory effects, and there has lately been increasing interest in utilizing the immunoactive properties of the n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) in a variety of clinical settings (144, 145). Animal models and clinical trials of supplementation with n-3 PUFA, which are present in oily fish, have demonstrated a diverse and sometimes contradictory range of effects on immune function. Most studies show them to be predominantly immunosuppressant, with impairment of NK cell function, delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and T-cell (especially Th1) function, although some studies have shown an opposite effect with increases in lymphocyte responsiveness (146, 147). Competitive antagonism of the generation of arachidonic acid metabolites and the parallel formation of anti-inflammatory ‘resolvin’ molecules underlie some of these effects (148). In addition, the incorporation of n-3 PUFA into cell membranes alters membrane fluidity, and their disruption of lipid raft formation in T-cell membranes has been shown to correlate with T-cell signalling defects (149).

Most clinical interest in young children has focused on the potential impact of lipid status on atopic disease incidence and severity. The Childhood Asthma Prevention Study trialled n-3 PUFA-rich supplements for infants at risk of asthma and reported less wheeze episodes at 18 months of age (150, 151). However, there was no long-term effect on the children’s incidence of asthma despite sustained alteration of their plasma fatty acids (152). Maternal consumption during pregnancy has resulted in both clinical and laboratory evidence of slight benefit to infants at risk of allergy (153-155), and variations in n-3/n-6 PUFAs in breast milk have been found in allergic mothers, and these have had an impact on allergic outcome in their infants (156).

Some recent work has shown encouraging signs that fatty acid supplementation may impact on the immune response to infection as well. N-3 PUFA supplementation during late infancy led to increased production of IFN during lipopolysaccharide–stimulated whole blood culture, suggesting a more efficient immune response (157). Similar effects were seen when the lactating mother received supplements during early infancy, and these efficiency gains persisted for at least 2 yr (158). A recent trial of n-3 supplementation for Thai school children aged 9 to 12 resulted in significantly reduced frequency of infections (159). In adult studies, there is conflicting data, although some studies have shown improved outcomes during sepsis, possibly because of immunoregulatory effect that improves the efficiency of the immune response (160).

These results and the observation that some subsistence diets in the Developing World may have markedly unbalanced n-6 to n-3 ratios of more than 30:1 (161) raise the intriguing question of whether subclinical lipid malnutrition could lead to increased risk of infective pathology and whether n-3 PUFA supplementation could impact on the global disease burden of malnutrition-associated infection. Further research is warranted in this area.

Summary

Nutrition around the time of birth is an important determinant of the efficiency of neonatal immune responses to infection. The benefits of breastfeeding are clear and reinforce the public health imperative to improve breastfeeding rates across the World. Providing appropriate supplements for the pregnant and lactating mother could be useful methods to strengthen infant immune function, but their effectiveness, and even potential to cause harm, is unclear at present. The likely importance of malnutrition during infancy is not matched by a depth of mechanistic understanding of the associations between protein-energy, multiple micronutrient, and lipid malnutrition, and immunity to infection. A better understanding of the mechanisms behind these effects could generate biomarkers for use in clinical trials or practice, allowing complex nutritional interventions to be assessed over a shorter time period than is required to show significance under current circumstances. Further work quantifying the effects of nutrient supplementation on metabolism and stores will also be important, both looking in detail at trial participants’ nutritional status at the start and end of an intervention and investigating maternal transfer of nutrients to the foetus. Without such information, questions regarding the optimum dose, delivery vehicle and combination of nutrients for routine supplementation are difficult to answer.

Nutritional research to date suggests that there will not be a simple or single nutritional intervention that dramatically reverses the association between malnutrition and infection. The importance of prenatal and infant malnutrition as determinants of global mortality necessitate more work in this area, but a focus on complex and relatively nutritionally ‘complete’ interventions may be indicated. A clearer mechanistic understanding of immunity during poor nutrition will be an important correlate of this approach and should be a priority for research.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Kath Maitland, who read and commented on an earlier draft of the manuscript. KDJJ and JOW are grateful for support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme. JAB is supported by a fellowship from the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Newburg DS, Walker WA. Protection of the neonate by the innate immune system of developing gut and of human milk. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:2–8. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000250274.68571.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones CA, Vance GH, Power LL, Pender SL, MacDonald TT, Warner JO. Costimulatory molecules in the developing human gastrointestinal tract: a pathway for fetal allergen priming. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:235–41. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thornton CA, Holloway JA, Popplewell EJ, Shute JK, Boughton J, Warner JO. Fetal exposure to intact immunoglobulin E occurs via the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:306–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandtzaeg P. Development and basic mechanisms of human gut immunity. Nutr Rev. 1998;56:S5–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamanaka T, Helgeland L, Farstad IN, Fukushima H, Midtvedt T, Brandtzaeg P. Microbial colonization drives lymphocyte accumulation and differentiation in the follicle-associated epithelium of Peyer’s patches. J Immunol. 2003;170:816–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolach B, Dolfin T, Regev R, Gilboa S, Schlesinger M. The development of the complement system after 28 weeks’ gestation. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:523–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb08924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrova A, Mehta R. Dysfunction of innate immunity and associated pathology in neonates. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:185–91. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maródi L. Innate cellular immune responses in newborns. Clin Immunol. 2006;118:137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sundström Y, Nilsson C, Lilja G, Kärre K, Troye-Blomberg M, Berg L. The expression of human natural killer cell receptors in early life. Scand J Immunol. 2007;66:335–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billingham RE, Brent L, Medawar PB. Actively acquired tolerance of foreign cells. Nature. 1953;172:603–6. doi: 10.1038/172603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fadel S, Sarzotti M. Cellular immune responses in neonates. Int Rev Immunol. 2000;19:173–93. doi: 10.3109/08830180009088504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegrist CA. Neonatal and early life vaccinology. Vaccine. 2001;19:3331–46. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt PG, Jones CA. The development of the immune system during pregnancy and early life. Allergy. 2000;55:688–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adkins B, Leclerc C, Marshall-Clarke S. Neonatal adaptive immunity comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:553–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchant A, Appay V, Van der Sande M, et al. Mature CD8(+) T lymphocyte response to viral infection during fetal life. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1747–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI17470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elbou Ould MA, Luton D, Yadini M, et al. Cellular immune response of fetuses to cytomegalovirus. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:280–6. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000104150.85437.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones AC, Miles EA, Warner JO, Colwell BM, Bryant TN, Warner JA. Fetal peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferative responses to mitogenic and allergenic stimuli during gestation. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1996;7:109–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1996.tb00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warner JO. The early life origins of asthma and related allergic disorders. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:97–102. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.013029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Härtel C, Adam N, Strunk T, Temming P, Müller-Steinhardt M, Schultz C. Cytokine responses correlate differentially with age in infancy and early childhood. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;142:446–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velilla PA, Rugeles MT, Chougnet CA. Defective antigen-presenting cell function in human neonates. Clin Immunol. 2006;121:251–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michaëlsson J, Mold JE, McCune JM, Nixon DF. Regulation of T cell responses in the developing human fetus. J Immunol. 2006;176:5741–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence RM, Pane CA. Human breast milk: current concepts of immunology and infectious diseases. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2007;37:7–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371:243–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleischer Michaelsen K, Weaver L, Branca F, Robertson A. Health and nutritional status and feeding practices. In: Fleischer Michaelsen K, Weaver L, Branca F, Robertson A., editors. Feeding and Nutrition of Infants and Young Children: Guidelines for the WHO European Region, with Emphasis on the former Soviet Countries. World Health Organization; Copenhagen: 2003. pp. 10–37. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okuyama H, Urao M, Lee D, Drongowski RA, Coran AG. The effect of epidermal growth factor on bacterial translocation in newborn rabbits. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:225–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu VYH. Scientific rationale and benefits of nucleotide supplementation of infant formula. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38:543–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldman AS, Chheda S, Garofalo R. Evolution of immunologic functions of the mammary gland and the postnatal development of immunity. Pediatr Res. 1998;43:155–62. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199802000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandtzaeg P. Mucosal immunity: integration between mother and the breast-fed infant. Vaccine. 2003;21:3382–8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker WA. The dynamic effects of breastfeeding on intestinal development and host defense. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;554:155–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-4242-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen LH, Graham JM. Assuring micronutrient adequacy in the diets of young infants. In: Delange FM, West KPJ, editors. Micronutrient Deficiencies in the First Six Months of Life. Vevey/S. Karger AG; Basel: 2003. pp. 55–88. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen LH. Multiple micronutrients in pregnancy and lactation: an overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1206S–12S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ngom PT, Collinson AC, Pido-Lopez J, Henson SM, Prentice AM, Aspinall R. Improved thymic function in exclusively breastfed infants is associated with higher interleukin 7 concentrations in their mothers’ breast milk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:722–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tannock GW, Fuller R, Smith SL, Hall MA. Plasmid profiling of members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, lactobacilli, and bifidobacteria to study the transmission of bacteria from mother to infant. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1225–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1225-1228.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harmsen HJ, Wildeboer-Veloo AC, Raangs GC, et al. Analysis of intestinal flora development in breast-fed and formula-fed infants by using molecular identification and detection methods. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30:61–7. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200001000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mountzouris KC, McCartney AL, Gibson GR. Intestinal microflora of human infants and current trends for its nutritional modulation. Br J Nutr. 2002;87:405–20. doi: 10.1079/BJNBJN2002563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourlioux P, Koletzko B, Guarner F, Braesco V. The intestine and its microflora are partners for the protection of the host: report on the Danone Symposium “The Intelligent Intestine”, held in Paris, June 14, 2002. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:675–83. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hooper LV, Wong MH, Thelin A, Hansson L, Falk PG, Gordon JI. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science. 2001;291:881–4. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5505.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forchielli ML, Walker WA. The role of gut-associated lymphoid tissues and mucosal defence. Br J Nutr. 2005;93(Suppl 1):S41–8. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smits HH, Engering A, Van der Kleij D, et al. Selective probiotic bacteria induce IL-10-producing regulatory T cells in vitro by modulating dendritic cell function through dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1260–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalliomäki M, Isolauri E. Role of intestinal flora in the development of allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;3:15–20. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200302000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Penders J, Stobberingh EE, Van den Brandt PA, Thijs C. The role of the intestinal microbiota in the development of atopic disorders. Allergy. 2007;62:1223–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boehm G, Jelinek J, Stahl B, et al. Prebiotics in infant formulas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:S76–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000128927.91414.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Euler AR, Mitchell DK, Kline R, Pickering LK. Prebiotic effect of fructo-oligosaccharide supplemented term infant formula at two concentrations compared with unsupplemented formula and human milk. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:157–64. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200502000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rinne MM, Gueimonde M, Kalliomäki M, Hoppu U, Salminen SJ, Isolauri E. Similar bifidogenic effects of prebiotic-supplemented partially hydrolyzed infant formula and breastfeeding on infant gut microbiota. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;43:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pedone CA, Arnaud CC, Postaire ER, Bouley CF, Reinert P. Multicentric study of the effect of milk fermented by Lactobacillus casei on the incidence of diarrhoea. Int J Clin Pract. 2000;54:568–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szajewska H, Mrukowicz JZ. Probiotics in the treatment and prevention of acute infectious diarrhea in infants and children: a systematic review of published randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33(Suppl 2):S17–25. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200110002-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang JS, Bousvaros A, Lee JW, Diaz A, Davidson EJ. Efficacy of probiotic use in acute diarrhea in children: a meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2625–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1020501202369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Niel CW, Feudtner C, Garrison MM, Christakis DA. Lactobacillus therapy for acute infectious diarrhea in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2002;109:678–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hatakka K, Savilahti E, Pönkä A, et al. Effect of long term consumption of probiotic milk on infections in children attending day care centres: double blind, randomised trial. BMJ. 2001;322:1327. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7298.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weizman Z, Asli G, Alsheikh A. Effect of a probiotic infant formula on infections in child care centers: comparison of two probiotic agents. Pediatrics. 2005;115:5–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dani C, Biadaioli R, Bertini G, Martelli E, Rubatelli FF. Probiotics feeding in prevention of urinary tract infection, bacterial sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. A prospective double-blind study. Biol Neonate. 2002;82:103–8. doi: 10.1159/000063096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osborn DA, Sinn JK. Probiotics in infants for prevention of allergic disease and food hypersensitivity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006475.pub2. CD006475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schultz M, Göttl C, Young RJ, Iwen P, Vanderhoof JA. Administration of oral probiotic bacteria to pregnant women causes temporary infantile colonization. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:293–7. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200403000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gueimonde M, Sakata S, Kalliomäki M, et al. Effect of maternal consumption of lactobacillus GG on transfer and establishment of fecal bifidobacterial microbiota in neonates. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:166–70. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000189346.25172.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lahtinen SJ, Boyle RJ, Kivivuori S, et al. Prenatal probiotic administration can influence Bifidobacterium microbiota development in infants at high risk of allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:499–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prescott SL, Wickens K, Westcott L, et al. Supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus or Bifidobacterium lactis probiotics in pregnancy increases cord blood interferon-gamma and breast milk transforming growth factor-beta and immunoglobin A detection. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1606–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boyle RJ, Mah L, Chen A, Kivivuori S, Robins-Browne RM, Tang ML. Effects of Lactobacillus GG treatment during pregnancy on the development of fetal antigen-specific immune responses. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1882–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duggan C, Penny ME, Hibberd P, et al. Oligofructose-supplemented infant cereal: 2 randomized, blinded, community-based trials in Peruvian infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:937–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.4.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bakker-Zierikzee AM, Tol EAF, Kroes H, Alles MS, Kok FJ, Bindels JG. Faecal SIgA secretion in infants fed on pre- or probiotic infant formula. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2006;17:134–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arsanoglu S, Moro GE, Schmitt J, Tandoli L, Rizzardi S, Boehm G. Early dietary intervention with a mixture of prebiotic oligosaccharides reduces the incidence of allergic manifestations and infections during the first two years of life. J Nutr. 2008;138:1091–5. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.6.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bruzzese E, Volpicelli M, Squeglia V, et al. A formula containing galacto- and fructo-oligosaccharides prevents intestinal and extra-intestinal infections: an observational study. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:156–61. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shadid R, Haarman M, Knol J, et al. Effects of galactooligosaccharide and long-chain fructooligosaccharide supplementation during pregnancy on maternal and neonatal microbiota and immunity – a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1426–37. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caulfield LE, De Onis M, Blössner M, Black RE. Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:193–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Black RE. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. Lancet. 2005;365:1147–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhutta ZA. Effect of infections and environmental factors on growth and nutritional status in developing countries. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43(Suppl 3):S13–21. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000255846.77034.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Campbell DI, Elia M, Lunn PG. Growth faltering in rural Gambian infants is associated with impaired small intestinal barrier function, leading to endotoxemia and systemic inflammation. J Nutr. 2003;133:1332–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schaible UE, Kaufmann SHE. Malnutrition and infection: complex mechanisms and global impacts. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nájera O, González C, Toledo G, López L, Ortiz R. Flow cytometry study of lymphocyte subsets in malnourished and well-nourished children with bacterial infections. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:577–80. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.3.577-580.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hughes SM, Amadi B, Mwiya M, Nkamba H, Tomkins A, Goldblatt D. Dendritic cell anergy results from endotoxemia in severe malnutrition. J Immunol. 2009;183:2818–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fall CHD, Yajnik CS, Rao S, Davies AA, Brown N, Farrant HJW. Micronutrients and fetal growth. J Nutr. 2003;133:1747S–56S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1747S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.World Health Organisation Maternal anthropometry and pregnancy outcomes: a WHO collaborative study. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:S1–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kramer MS. Balanced protein/energy supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000118. CD000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chatrath R, Saili A, Jain M, Dutta AK. Immune status of full-term small-for-gestational age neonates in India. J Trop Pediatr. 1997;43:345–8. doi: 10.1093/tropej/43.6.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barker DJP, Fall CHD. Technical Consultation on Low Birthweight. UNI-CEF; New York: 2000. The immediate and long-term consequences of low birthweight. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Langley-Evans AJ, Langley-Evans SC. Relationship between maternal nutrient intakes in early and late pregnancy and infants weight and proportions at birth: prospective cohort study. J R Soc Health. 2003;123:210–6. doi: 10.1177/146642400312300409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shrimpton R, Victora CG, De Onis M, Lima RC, Blössner M, Clugston G. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: implications for nutritional interventions. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E75. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.World Health Organisation . Severe Malnutrition: Report of a Consultation to Review Current Literature. WHO; Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 78.United Nations Children’s Fund and World Health Organisation . Low Birthweight: Country, Regional and Global Estimates. UNICEF; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moore SE, Cole TJ, Collinson AC, Poskitt EM, McGregor IA, Prentice AM. Prenatal or early postnatal events predict infectious deaths in young adulthood in rural Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:1088–95. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.6.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McDade TW, Beck MA, Kuzawa CW, Adair LS. Prenatal undernutrition and postnatal growth are associated with adolescent thymic function. J Nutr. 2001;131:1225–31. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Collinson AC, Ngom PT, Moore SE, Morgan G, Prentice AM. Birth season and environmental influences on blood leucocyte and lymphocyte subpopulations in rural Gambian infants. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McDade TW, Beck MA, Kuzawa CW, Adair LS. Prenatal undernutrition, postnatal environments, and antibody response to vaccination in adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:543–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moore SE, Jalil F, Ashraf R, Szu SC, Prentice AM, Hanson LA. Birth weight predicts response to vaccination in adults born in an urban slum in Lahore, Pakistan. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:453–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.2.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moore SE, Collinson AC, Prentice AM. Immune function in rural Gambian children is not related to season of birth, birth size, or maternal supplementation status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:840–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.6.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chandra RK. Antibody formation in first and second generation offspring of nutritionally deprived rats. Science. 1975;190:289–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1179211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Beach RS, Gershwin ME, Hurley LS. Gestational zinc deprivation in mice: persistence of immunodeficiency for three generations. Science. 1982;218:469–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7123244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lumey LH, Stein AD. Offspring birth weights after maternal intrauterine undernutrition: a comparison within sibships. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:810–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li Y, Langholz B, Salam MT, Gilliland FD. Maternal and grandmaternal smoking patterns are associated with early childhood asthma. Chest. 2005;127:1232–41. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.4.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zeisel SH. Epigenetic mechanisms for nutrition determinants of later health outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1488S–93S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27113B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wintergerst ES, Maggini S, Hornig DH. Contribution of selected vitamins and trace elements to immune function. Ann Nutr Metab. 2007;51:301–23. doi: 10.1159/000107673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nyakeriga AM, Troye-Blomberg M, Dorfman JR, et al. Iron deficiency and malaria among children living on the coast of Kenya. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:439–47. doi: 10.1086/422331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sazawal S, Black RE, Ramsan M, et al. Effects of routine prophylactic supplementation with iron and folic acid on admission to hospital and mortality in preschool children in a high malaria transmission setting: community-based, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:133–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67962-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tielsch JM, Khatry SK, Stoltzfus RJ, et al. Effect of routine prophylactic supplementation with iron and folic acid on preschool child mortality in southern Nepal: community-based, cluster-randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:144–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67963-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stoltzfus RJ. Developing countries: the critical role of research to guide policy and programs research needed to strengthen science and programs for the control of iron deficiency and its consequences in young children. J Nutr. 2008;138:2542–6. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.094888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grantham-McGregor S, Ani C. A review of studies on the effect of iron deficiency on cognitive development in children. J Nutr. 2001;131(2S-2):649S–66S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.649S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Prentice AM. Iron metabolism, malaria, and other infections: what is all the fuss about? J Nutr. 2008;138:2537–41. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.098806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Preziosi P, Prual A, Galan P, Daouda H, Boureima H, Hercberg S. Effect of iron supplementation on the iron status of pregnant women: consequences for newborns. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:1178–82. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.5.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chaparro CM. Setting the stage for child health and development: prevention of iron deficiency in early infancy. J Nutr. 2008;138:2529–33. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.12.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cunningham-Rundles S, McNeeley DF, Moon A. Mechanisms of nutrient modulation of the immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1119–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lazzerini M, Ronfani L. Oral zinc for treating diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005436.pub2. CD005436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Walker CLF, Bhutta ZA, Bhandari N, et al. Zinc during and in convalescence from diarrhea has no demonstrable effect on subsequent morbidity and anthropometric status among infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:887–94. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brooks WA, Yunus M, Santosham M, et al. Zinc for severe pneumonia in very young children: double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1683–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mahalanabis D, Lahiri M, Paul D, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of the efficacy of treatment with zinc or vitamin A in infants and young children with severe acute lower respiratory infection. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:430–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bose A, Coles CL, Gunavathi, et al. Efficacy of zinc in the treatment of severe pneumonia in hospitalized children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1089–96. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Osendarp SJM, Santosham M, Black RE, Wahed MA, Van Raaij JMA, Fuchs GJ. Effect of zinc supplementation between 1 and 6 mo of life on growth and morbidity of Bangladeshi infants in urban slums. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:1401–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sazawal S, Black RE, Ramsan M, et al. Effect of zinc supplementation on mortality in children aged 1–48 months: a community-based randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:927–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60452-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tielsch JM, Khatry SK, Stoltzfus RJ, et al. Effect of daily zinc supplementation on child mortality in southern Nepal: a community-based, cluster randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1230–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61539-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Roth DE, Caulfield LE, Ezzati M, Black RE. Acute lower respiratory infections in childhood: opportunities for reducing the global burden through nutritional interventions. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:356–64. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sazawal S, Black RE, Menon VP, et al. Zinc supplementation in infants born small for gestational age reduces mortality: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1280–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.6.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hemalatha P, Bhaskaram P, Kumar PA, Khan MM, Islam MA. Zinc status of breastfed and formulafed infants of different gestational ages. J Trop Pediatr. 1997;43:52–4. doi: 10.1093/tropej/43.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Luabeya KA, Mpontshane N, Mackay M, et al. Zinc or multiple micronutrient supplementation to reduce diarrhea and respiratory disease in South African children: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.West KPJ. Vitamin A deficiency disorders in children and women. Food Nutr Bull. 2003;24:S78–90. doi: 10.1177/15648265030244S204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Huiming Y, Chaomin W, Meng M. Vitamin A for treating measles in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001479.pub3. CD001479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Villamor E, Fawzi WW. Effects of vitamin a supplementation on immune responses and correlation with clinical outcomes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:446–64. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.446-464.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shankar AH, Genton B, Semba RD, et al. Effect of vitamin A supplementation on morbidity due to Plasmodium falciparum in young children in Papua New Guinea: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:203–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen H, Zhuo Q, Yuan W, Wang J, Wu T. Vitamin A for preventing acute lower respiratory tract infections in children up to seven years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006090.pub2. CD006090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.West KPJ, Sommer A, Tielsch JM, Katz J, Christian P, Klemm RDW. A central question not answered: can newborn vitamin A reduce infant mortality in South Asia? BMJ. 2009 http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/338/mar27_1/b919. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bikle DD. Vitamin D and the immune system: role in protection against bacterial infection. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:348–52. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282ff64a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Walker VP, Modlin RL. The Vitamin D Connection to Pediatric Infections and Immune Function. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:106R–113R. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819dba91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ginde AA, Mansbach JM, Camargo CAJ. Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and upper respiratory tract infection in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:384–90. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Martineau AR, Wilkinson RJ, Wilkinson KA, et al. A single dose of vitamin D enhances immunity to mycobacteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:208–13. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-007OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Martineau AR, Honecker FU, Wilkinson RJ, Griffiths CJ. Vitamin D in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:793–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wejse C, Gomes VF, Rabna P, et al. Vitamin D as Supplementary Treatment for Tuberculosis – A Double-blind Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:843–50. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-567OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kovacs CS. Vitamin D in pregnancy and lactation: maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes from human and animal studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:520S–8S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.520S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Beck MA, Levander OA, Handy J. Selenium deficiency and viral infection. J Nutr. 2003;133:1463S–7S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1463S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Shaheen SO, Newson RB, Henderson AJ, Emmett PM, Sheriff A, Cooke M. Umbilical cord trace elements and minerals and risk of early childhood wheezing and eczema. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:292–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00117803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fawzi W, Msamanga G, Spiegelman D, Hunter DJ. Studies of vitamins and minerals and HIV transmission and disease progression. J Nutr. 2005;135:938–44. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nestel PS, Jackson AA. The impact of maternal micronutrient supplementation on early neonatal morbidity. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:647–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.137745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Doyle W, Crawford MA, Laurance BM, Drury P. Dietary survey during pregnancy in a low socio-economic group. Hum Nutr Appl Nutr. 1982;36:95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Rao S, Yajnik CS, Kanade A, et al. Intake of micronutrient-rich foods in rural Indian mothers is associated with the size of their babies at birth: Pune Maternal Nutrition Study. J Nutr. 2001;131:1217–24. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Haider BA, Bhutta ZA. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004905.pub5. CD004905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Fawzi WW, Msamanga GI, Urassa W, et al. Vitamins and perinatal outcomes among HIV-negative women in Tanzania. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1423–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gupta P, Ray M, Dua T, Radhakrishnan G, Kumar R, Sachdev HPS. Multimicronutrient supplementation for undernourished pregnant women and the birth size of their offspring: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:58–64. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Maradones F, Urrutia M, Villaroel L, et al. Effects of a dairy product fortified with multiple micronutrients and omega-3 fatty acids on birth weight and gestation duration in pregnant Chilean women. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:30–40. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zagré NM, Desplats G, Adou P, Mamadoultaibou A, Aguayo VM. Prenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation has greater impact on birthweight than supplementation with iron and folic acid: a cluster-randomized, double-blind, controlled programmatic study in rural Niger. Food Nutr Bull. 2007;28:317–27. doi: 10.1177/156482650702800308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.The Supplementation with Multiple Micronutrients Intervention Trial (SUMMIT) Study Group Effect of maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation on fetal loss and infant death in Indonesia: a double-blind cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:215–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Christian P, Khatry SK, Katz J, et al. Effects of alternative maternal micronutrient supplements on low birth weight in rural Nepal: double blind randomised community trial. BMJ. 2003;326:571. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7389.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Osrin D, Vaidya A, Shrestha Y, et al. Effects of antenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation on birthweight and gestational duration in Nepal: double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:955–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Christian P, West KP, Khatry SK, et al. Effects of maternal micronutrient supplementation on fetal loss and infant mortality: a cluster-randomized trial in Nepal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:1194–202. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.6.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Christian P, Osrin D, Manandhar DS, Khatry SK, de LCostello AM, West KPJ. Antenatal micronutrient supplements in Nepal. Lancet. 2005;366:711–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67166-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Christian P, Darmstadt GL, Wu L, et al. The effect of maternal micronutrient supplementation on early neonatal morbidity in rural Nepal: a randomised, controlled, community trial. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:660–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.114009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Vaidya A, Saville N, Shrestha BP, de LCostello AM, Manandhar DS, Osrin D. Effects of antenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation on children’s weight and size at 2 years of age in Nepal: follow-up of a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:492–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60172-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zeng L, Dibley MJ, Cheng Y, et al. Impact of micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy on birth weight, duration of gestation, and perinatal mortality in rural western China: double blind cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a2001. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Calder PC. The relationship between the fatty acid composition of immune cells and their function. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008;79:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Gottrand F. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids influence the immune system of infants. J Nutr. 2008;138:1807S–12S. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.9.1807S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Calder PC, Grimble RF. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation and immunity. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56(Suppl 3):S14–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Field CJ, Johnson IR, Schley PD. Nutrients and their role in host resistance to infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:16–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Serhan CN, Arita M, Hong S, Gotlinger K. Resolvins, docosatrienes, and neuroprotectins, novel omega-3-derived mediators, and their endogenous aspirin-triggered epimers. Lipids. 2004;39:1125–32. doi: 10.1007/s11745-004-1339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Fan Y, McMurray DN, Ly LH, Chapkin RS. Dietary (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids remodel mouse T-cell lipid rafts. J Nutr. 2003;133:1913–20. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.6.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Mihrshahi S, Peat JK, Webb K, Oddy W, Marks GB, Mellis CM. Effect of omega-3 fatty acid concentrations in plasma on symptoms of asthma at 18 months of age. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004;15:517–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2004.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Peat JK, Mihrshahi S, Kemp AS, et al. Three-year outcomes of dietary fatty acid modification and house dust mite reduction in the Childhood Asthma Prevention Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:807–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Marks GB, Mihrshahi S, Kemp AS, et al. Prevention of asthma during the first 5 years of life: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Dunstan JA, Mori TA, Barden A, et al. Fish oil supplementation in pregnancy modifies neonatal allergen-specific immune responses and clinical outcomes in infants at high risk of atopy: a randomized, controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:1178–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Dunstan JA, Mori TA, Barden A, et al. Maternal fish oil supplementation in pregnancy reduces interleukin-13 levels in cord blood of infants at high risk of atopy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:442–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Decsi T, Campoy C, Koletzko B. Effect of N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in pregnancy: the Nuheal trial. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;569:109–13. doi: 10.1007/1-4020-3535-7_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Warner JO. Early life nutrition and allergy. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83:777–83. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Damsgaard CT, Lauritzen L, Kjaer TMR, et al. Fish oil supplementation modulates immune function in healthy infants. J Nutr. 2007;137:1031–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Lauritzen L, Kjaer TMR, Fruekilde M, Michaelsen KF, Frøkiaer H. Fish oil supplementation of lactating mothers affects cytokine production in 2 1/2-year-old children. Lipids. 2005;40:669–76. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Thienprasert A, Samuhaseneetoo S, Popplestone K, West AL, Miles EA, Calder PC. Fish oil n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids selectively affect plasma cytokines and decrease illness in Thai schoolchildren: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled intervention trial. J Pediatr. 2009;154:391–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Mayer K, Seeger W. Fish oil in critical illness. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:121–7. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f4cdc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Prentice AM, Paul AA. Fat and energy needs of children in developing countries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1253S–65S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1253s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]