Abstract

Estrogens affect body fluid balance, including sodium ingestion. Recent findings of a population of neurons in the hindbrain Nucleus of the Solitary Tract (NTS) of rats that are activated during sodium need suggest a possible central substrate for this effect of estrogens. We used immunohistochemistry to label neurons in the NTS that express 11-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (HSD2), an enzyme that promotes aldosterone binding, in male rats, and in ovariectomized (OVX) rats given estradiol benzoate (EB) or oil vehicle (OIL). During baseline conditions, the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the NTS immediately rostral to the area postrema was greater in EB-treated OVX rats compared to those in OIL-treated OVX and male rats. A small number of HSD2 neurons also was labeled for dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH), an enzyme involved in norepinephrine biosynthesis. Double-labeled neurons in the NTS were located primarily in the more lateral portion of the HSD2 population, at the level of the area postrema in all three groups, with no sex or estrogen-mediated differences in the number of double-labeled neurons. These results suggest two subpopulations of HSD2 neurons are present in the NTS. One subpopulation, which does not co-localize with DBH and is increased during conditions of elevated estradiol, may contribute to the effects of estrogens on sodium ingestion. The role of the other, smaller subpopulation, which co-localizes with DBH and is not affected by estradiol, remains to be determined, but one possibility is that these latter neurons are part of a larger network of catecholaminergic input to neuroendocrine neurons in the hypothalamus.

Keywords: sex differences, ovariectomy, salt intake, dopamine-β-hydroxylase

1. INTRODUCTION

Greater understanding of the genomic and molecular actions of steroid hormones has expanded investigations of the effects of reproductive hormones beyond those related to reproduction. As a result, it has become increasingly clear that reproductive hormones influence numerous physiological and behavioral parameters. For example, ovarian steroid hormones such as the estrogens affect fundamental physiological processes, including the regulation of body sodium balance (Curtis, 2009; Pechere-Bertschi and Burnier, 2004; Sladek and Somponpun, 2008; Somponpun, 2007). The primary source of body sodium is from the diet, so it is, perhaps, not surprising that humans, rats, and other species exhibit sex differences in NaCl ingestion (Chow et al., 1992; Krecek et al., 1972; Wolf, 1982) that also appear to be mediated by estrogens (Curtis et al., 2004; Danielsen and Buggy, 1980; Fregly, 1973; Kensicki et al., 2002; Scheidler et al., 1994; but see Chow et al., 1992; Krecek, 1973). Given the lipophilic nature of estrogens, and the localization of estrogen receptors (ERs) to many CNS areas implicated in body sodium balance and NaCl ingestion (Alves et al., 1998; Rosas-Arellano et al., 1999; Schlenker and Hansen, 2006; Simonian and Herbison, 1997; Somponpun et al., 2004; Voisin et al., 1997), it seems likely that central actions of estrogens underlie this difference. However, the specific central mechanism(s) remains uncertain. In fact, the central pathways and neurotransmitter systems involved in the control of NaCl ingestion have yet to be definitively determined in males, though a number of investigators have variously focused on midbrain serotonergic neurons (De Gobbi et al., 2007), hypothalamic oxytocin systems (Blackburn et al., 1995), and morphological changes in dopaminergic neurons of the nucleus accumbens (Roitman et al., 2002). Clearly then—and despite thirty years of investigation—the central mechanisms involved in sex differences in NaCl intake are largely unknown.

Recent investigations of a small population of neurons within the Nucleus of the Solitary Tract (NTS) of rats may provide insight into this issue. These neurons express 11-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (HSD2), an enzyme that facilitates binding of the sodium conserving steroid hormone, aldosterone, to mineralocorticoid receptors (Naray-Fejes-Toth et al., 1998). HSD2 neurons are activated by a variety of experimental manipulations that stimulate NaCl ingestion (Geerling et al., 2006a; Geerling and Loewy, 2006a; Geerling and Loewy, 2007; Geerling and Loewy, 2008). Circulating aldosterone is elevated in many of these experimental manipulations, and has been implicated in NaCl ingestion by virtue of its central actions (Fluharty and Epstein, 1983). Thus, it would seem reasonable to assume that the increased activity in HSD2 neurons is driven by aldosterone. In fact, treatment of rats with deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA), an aldosterone precursor that stimulates NaCl ingestion without producing sodium deficiency, activates HSD2 neurons (Geerling et al., 2006a). In addition, excitation of HSD2 neurons is reversed by NaCl ingestion (Geerling et al., 2006a) which suppresses aldosterone release. However, dietary sodium deprivation also activates HSD2 neurons in adrenalectomized rats (Geerling et al., 2006a), suggesting that increased circulating aldosterone is not a necessary condition for the activation. Moreover, HSD2 neurons are not activated by DOCA treatment when rats are permitted to consume concentrated NaCl solutions (Geerling and Loewy, 2006a), suggesting that aldosterone is not sufficient to sustain excitation of HSD2 neurons in the presence of other factor(s), such as those related to the act of NaCl ingestion. In this regard, it has recently been reported that HSD2 neurons receive input, albeit sparse, from vagal afferents (Shin et al., 2009) that arise primarily from the stomach (Shin and Loewy, 2009). This observation is consistent with the inhibition of HSD2 neuronal activity by gastric signals related to NaCl consumption, although the functional significance of the input has yet to be conclusively demonstrated. In other studies, Loewy and colleagues found that HSD2 neurons receive input, possibly GABAergic, from neurons located in the area postrema (AP) (Sequeira et al., 2006), and send neural projections to circumscribed forebrain and pontine nuclei, primarily the Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis and the external lateral part of the Parabrachial Nucleus, along with the adjacent “pre” Locus Coeruleus (LC) (Geerling and Loewy, 2006b). Interestingly, there appears to be no co-localization of HSD2 with neurotransmitters including, but not limited to, acetylcholine, neurotensin, norepinephrine (NE) or somatostatin (Geerling et al., 2006b; Geerling and Loewy, 2006b). In fact, to date, the single exception to HSD2 co-localization with neurotransmitters (or markers for neurotransmitters) is glutamate (Geerling et al., 2008), leading to the proposal that HSD2 neurons comprise a novel population that is involved in the control of NaCl intake (Geerling et al., 2006b).

Given estrogen-mediated differences in basal and stimulated NaCl ingestion, as well as in basal and stimulated release of the antidiuretic hormone, vasopressin (Bossmar et al., 1995; Forsling and Peysner, 1988; Hartley et al., 2004; Ota et al., 1994; Stachenfeld et al., 1998), the goals of the present experiment were twofold. First, we sought to determine whether there are estrogen-mediated sex differences in the number of HSD2 neurons in the NTS under basal conditions. Since HSD2 neurons are associated with NaCl intake, such differences could indicate a central mechanism that underlies the effect of estrogens on NaCl ingestion; certainly, they could identify a candidate neurotransmitter system to target in subsequent investigations. Second, we examined the possibility of estrogen-mediated sex differences in HSD2 and NE co-localization within neurons of the NTS. It is known that hindbrain NE neurons are important in the release of vasopressin (Buller et al., 1996; Gieroba et al., 1994), and that brainstem catecholamine systems are, in part, regulated by circulating estrogens (Curran-Rauhut and Petersen, 2003; Liaw et al., 1992; Sabban et al., 2010; Serova et al., 2004; Serova et al., 2005). Therefore, such differences could provide insights into central pathways by which HSD2 neurons exert their effects and, more specifically, about whether HSD2 neurons are involved in other aspects of body fluid balance in females, in addition to NaCl intake. In short, our goal was to investigate hindbrain involvement in estrogen-mediated sex differences in body fluid regulation by focusing on HSD2 and NE cells in the NTS under basal conditions.

2. RESULTS

Immunolabeling

Digital photomicrographs of HSD2 and DBH immunolabeling in the NTS are shown in Figure 1; examples of double-immunolabeling are shown in Figure 2. Representative digital photomicrographs of immunolabeling in the NTS caudal to AP (capNTS), at the level of AP (apNTS) and immediately rostral to AP (rapNTS) of Male, OIL-treated OVX, and EB-treated OVX rats are shown in Figure 3-5. Images were cropped to illustrate specific areas/cells of interest; contrast and brightness were adjusted for some images.

Figure 1.

Digital photomicrographs of HSD2 and DBH immunolabeling in the NTS. Top: Examples of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons. Bottom: examples of DBH immunoreactive neurons. Scale bars - 20 μm.

Figure 2.

Digital photomicrographs of HSD2, DBH, and double immunolabeling in the NTS. Top: a neuron labeled for HSD2 (left) and DBH (middle); double-immunolabeling (right) is indicated by yellow-orange. Bottom: neurons labeled for HSD2 (left) and DBH (middle); the field shown in the right panel includes neurons labeled only for HSD2 or DBH, as well as a neuron immunolabeled for both HSD2 and DBH. Scale bars - 20 μm.

Figure 3.

Representative digital photomicrographs of HSD2 (top), DBH (middle), and double (bottom) immunolabeling in the capNTS. Area in box shows double immunolabeled neurons and is shown at higher magnification at the right. Green shading in the line drawing of the hindbrain indicates capNTS. dmv = dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; scale bars - 50 μm (left panels) or 20 μm (right panels).

Figure 5.

Representative digital photomicrographs of HSD2 and DBH immunolabeling in the rapNTS of a male rat (top), an OIL-treated OVX rat (middle) and an EB-treated OVX rat (bottom). Green shading in the line drawing of the hindbrain indicates rapNTS. 4V = 4th ventricle; scale bar - 50 μm.

HSD2 immunoreactive neurons

As shown in Figure 6, the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons depended on the level of the NTS (F(2,32) = 38.03, p<0.001). Overall, the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the apNTS was significantly greater than those in the capNTS and rapNTS (both ps<0.001), and the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the rapNTS was significantly greater than that in the capNTS (p<0.001). Although there was no overall, main effect of group on the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the NTS (F(2,16) = 0.24, ns), there was a significant interaction between group and NTS level (F(4,32) = 8.15, p<0.01). Pairwise comparisons of this interaction revealed that the numbers of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons at each of the three levels were similar in Male and OIL-treated OVX rats. In both of these groups, numbers of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the apNTS were significantly greater than those in the rapNTS (p<0.05, 0.001, respectively) and in the capNTS (both ps<0.001). In contrast, in EB-treated OVX rats, the numbers of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the apNTS and rapNTS were comparable, and these numbers were significantly greater than that in the capNTS (both ps<0.001). Moreover, the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the rapNTS of EB-treated OVX rats was significantly greater than those in the rapNTS of Male (p<0.05) and OIL-treated OVX (p<0.01) rats, though there were no group differences in numbers of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the apNTS or the capNTS.

Figure 6.

Mean numbers of HSD2 immunolabeled neurons in the capNTS, apNTS, and rapNTS of male rats (black bars), OIL-treated OVX rats (white bars), and EB-treated OVX rats (gray bars). Overall, the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in apNTS was greater than that in both capNTS and rapNTS; the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in rapNTS is greater than that in capNTS (all ps<0.001). a = greater than capNTS for corresponding group (all ps<0.001); b = greater than rapNTS for corresponding group (ps<0.05, 0.001); c = greater than rapNTS in male rats (p<0.05) and in OIL-treated OVX rats (p<0.01).

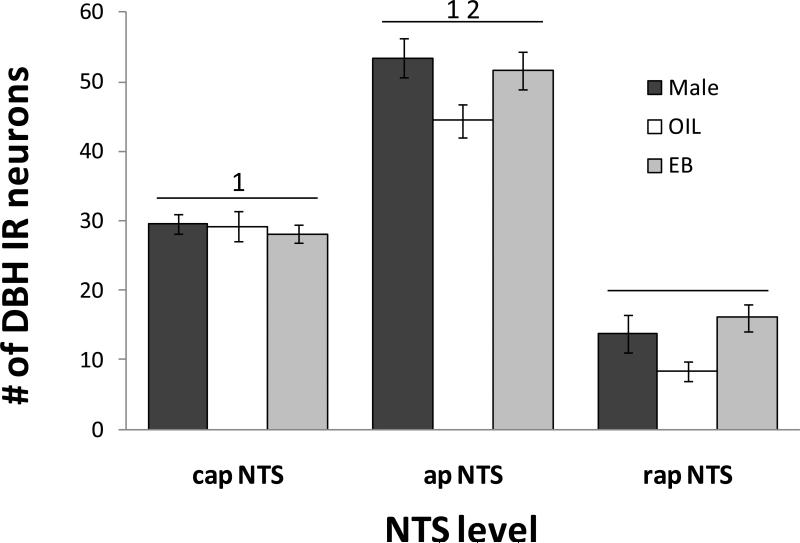

DBH immunoreactive neurons

As shown in Figure 7, the number of DBH immunoreactive neurons also depended on the level of the NTS (F(2,32) = 234.99, p<0.001). Overall, the number of DBH immunoreactive neurons in the apNTS was significantly greater than those in the capNTS and rapNTS (both ps<0.001), and the number of DBH immunoreactive neurons in the capNTS was significantly greater than that in the rapNTS (p<0.001). The number of DBH immunoreactive neurons also depended on group (F(1,16) = 4.22, p<0.05), with the number in OIL-treated OVX rats overall significantly less than those in Male and EB-treated OVX rats (both ps<0.05).

Figure 7.

Mean numbers of DBH immunolabeled neurons in the capNTS, apNTS, and rapNTS of male rats (black bars), OIL-treated OVX rats (white bars), and EB-treated OVX rats (gray bars). Overall, the number of DBH immunoreactive (IR) neurons in OIL-treated OVX rats was less than that in male rats and in EB-treated OVX rats (both ps<0.05). 1 = greater than rapNTS (both ps<0.001); 2 = greater than capNTS (p<0.001).

Double-labeled neurons

The number of double-labeled neurons was relatively low (Figure 8), and tended to be somewhat variable. Nonetheless, these numbers depended on the level of the NTS (F(2,32) = 12.86, p<0.001), with the number of double-labeled neurons in the apNTS significantly greater than those in the capNTS (p<0.01) and in the rapNTS (p<0.001). There also was a significant interaction between group and NTS level in the numbers of double-labeled neurons (F(4,32) = 2.92, p<0.05). Pairwise comparisons of this interaction revealed no differences between the three groups at any level, nor were there differences across levels in Male or EB-treated OVX rats. In contrast, in OIL-treated OVX rats the number of double-labeled neurons in the apNTS was significantly greater than that in the capNTS (p<0.05) and in the rapNTS (p<0.001).

Figure 8.

Mean numbers of double-immunolabeled neurons in the capNTS, apNTS, and rapNTS of male rats (black bars), OIL-treated OVX rats (white bars), and EB-treated OVX rats (gray bars). Overall, the number of double labeled neurons in apNTS was greater than that in both capNTS (p<0.01) and rapNTS (p<0.001). a = greater than rapNTS in OIL-treated OVX rats (p<0.001); b = greater than capNTS in OIL-treated OVX rats (p<0.05).

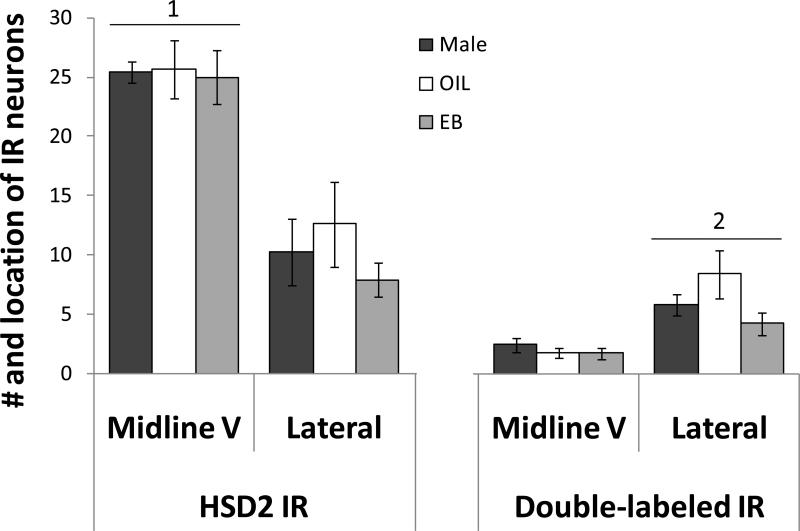

Midline V vs. lateral distribution of immunoreactive neurons in the apNTS

Within the apNTS, the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons (Figure 9, left) depended on the distribution (F(1,16) = 75.61, p<0.001), with the majority of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons located in the midline V. The number of double-labeled neurons within the apNTS (Figure 9, right) also depended on the distribution (F(1,16) = 75.61, p<0.001). However, this pattern was the opposite of that seen for HSD2 immunoreactive neurons, with the majority of double-labeled neurons located in somewhat more lateral portions of the NTS. There were no group differences and no interaction between group and distribution in either the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons or the number of double-labeled neurons within the apNTS.

Figure 9.

Mean numbers of HSD2 immunolabeled neurons (left) and double-labeled neurons (right) in the midline V and the more lateral portion of the apNTS of male rats (black bars), OIL-treated OVX rats (white bars), and EB-treated OVX rats (gray bars). Overall, the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the midline V was greater than that in the more lateral portion (1; p<0.001). In contrast, the number of double-labeled IR neurons in the more lateral portion of the apNTS was greater than that in the midline V (2; p<0.001).

EB treatment

Body weight

Body weight in EB-treated OVX rats decreased from day 1 to day 4 (-9.9 ± 1.5 g), whereas body weight in OIL-treated OVX rats increased (10.0 ± 1.8 g). Relative to body weight on day 1, the percent change was significantly different (-3.55 ± 0.53% vs. 3.74 ± 0.74%, respectively; p<0.001).

Uterine weight

On day 4, uterine weight in EB-treated OVX rats (94.6 ± 6.7 mg) was significantly greater (p<0.001) than that in OIL-treated OVX rats (35.3 ± 3.0 mg).

3. DISCUSSION

Profound differences exist between the sexes in numerous physiological and behavioral parameters, including behaviors associated with body sodium balance. Progress in elaborating the central systems underlying sex differences in NaCl intake has been hampered by limited information about the specific pathways and neurotransmitters that control this behavior. Thus, recent findings of a subpopulation of neurons in the NTS that have been implicated in NaCl ingestion (Geerling et al., 2006a; Geerling and Loewy, 2006a; Geerling and Loewy, 2007; Geerling and Loewy, 2008) represent an important advance in knowledge about the neurotransmitter systems involved in NaCl ingestion, and provide an exciting opportunity to ‘dissect out’ the role of reproductive hormones in NaCl intake. Estrogens have been reported to alter NaCl intake stimulated by a variety of experimental methods (Danielsen and Buggy, 1980; Scheidler et al., 1994), though the direction of the effects appears to depend on the specific method. In contrast, the majority of investigators report that, during basal conditions, elevated estrogens are associated with increased NaCl ingestion (Curtis et al., 2004; Danielsen and Buggy, 1980; Fregly, 1973; Kensicki et al., 2002). Accordingly, we opted to focus on basal conditions and use immunohistochemical methods as a first approach to assess the interactions between estrogens and HSD2-containing neurons in the NTS in the central control of NaCl intake. To do so, we used OVX rats with or without EB treatment, which allowed us to control the timing of the estradiol ‘surge’ and to examine the effects of estradiol independent of progesterone. We and others (Jones and Curtis, 2009; Kisley et al., 1999) have used this protocol in studies of ingestive behaviors, and the effectiveness of the protocol is evident in the present results showing the effects of EB treatment on body weight and uterine hypertrophy.

HSD2 immunolabeling

Consistent with previous reports (Geerling et al., 2006a; Geerling et al., 2006b; Geerling and Loewy, 2006b; see also Roland et al., 1995), we found that the distribution of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the NTS differed, depending on the level of the NTS. The greatest number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons was located in the apNTS and the least in the capNTS, regardless of the treatment group. Nonetheless, HSD2 labeling was affected by estrogens, with increased number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in EB-treated OVX rats. On the surface, estrogen-mediated sex differences in the number of HSD2 IR neurons may seem an unlikely possibility, particularly since most investigations have focused on the activation of HSD2 neurons during experimental manipulations that stimulate NaCl intake. However, the number of HSD2 neurons in male rats increased after 8 days of dietary sodium deprivation (Geerling et al., 2008), a condition associated with robust NaCl intake. Given estrogen-mediated differences in stimulated NaCl intake (Danielsen and Buggy, 1980; Scheidler et al., 1994), it will be of great interest to follow up on these initial observations to determine whether EB treatment also facilitates the activation of HSD2 neurons in response to experimental manipulations that induce NaCl ingestion. It also is possible that HSD2 neurons are more highly activated during basal conditions, an observation that would be consistent with greater baseline NaCl intake in EB-treated rats (Curtis et al., 2004; Kensicki et al., 2002). In any case, the present results show EB-mediated sex differences in the number of HSD2 neurons in the NTS under basal conditions; thus, it seems reasonable to suggest that differences in the number of HSD2 neurons may contribute to the effect of estrogens to increase spontaneous NaCl intake, and possibly stimulated NaCl ingestion, as well.

HSD2 neurons receive vagal afferents, including those from the stomach (Shin and Loewy, 2009), and the vagus nerve is important in the expression of ERs in the NTS (Estacio et al., 1996). These observations suggest that EB may increase the number of HSD2 neurons in the NTS that respond to gastric vagal input, thereby influencing NaCl intake by altering signals related to NaCl ingestion. An important caveat to this proposition is that EB treatment increased the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons only in the rapNTS without affecting numbers in the capNTS or apNTS, areas which are the primary recipients of vagal input from the gastrointestinal tract (Rinaman, 2007), and from baroreceptors (Dampney, 1994). In previous studies (Shin et al., 2009; Shin and Loewy, 2009), it appeared that input from the stomach and the nodose ganglion to HSD2 neurons in the capNTS and apNTS was denser than that to HSD2 neurons in the rapNTS. Thus, one might have expected EB-mediated differences in the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the capNTS and/or apNTS that play a role in NaCl intake by virtue of modulating gastric or baroreceptor signaling (Johnson and Thunhorst, 1997), rather than in the rapNTS. However, it is possible that EB treatment influences the expression of HSD2 in neurons of the capNTS or apNTS, rather than the number of HSD2 neurons, per se. That is, differences in the number of HSD2 neurons may be attributable to a genomic effect of EB to increase synthesis of the enzyme from levels previously not detectable, to those capable of being detected using our protocols. In the present study, we did not systematically evaluate the density of HSD2 immunolableling; thus, we cannot rule out this possibility or, indeed, the possibility that increased enzyme synthesis occurs at different rates throughout the NTS.

Although another explanation for the current findings is that EB treatment affects HSD2 neurons that receive dense descending input from hypothalamic or midbrain regions (e.g., Geerling and Loewy, 2006c; Geerling et al., 2010), an alternative hypothesis centers on observations that estrogens alter behavioral responses to the taste of salt (Curtis et al., 2004; Curtis and Contreras, 2006; Kensicki et al., 2002; Scheidler et al., 1994) and on our recent study showing that EB treatment modifies electrophysiological responses of the chorda tympani nerve to lingual application of NaCl (Curtis and Contreras, 2006). The chorda tympani branch of the facial nerve carries salt taste information to the CNS, and its afferent fibers terminate primarily in portions of the NTS (Contreras et al., 1980) substantially more rostral than those examined in the present study. However, under certain dietary sodium conditions, chorda tympani fibers distribute more expansively throughout the NTS (May and Hill, 2006). At present, it is not clear whether this expansion includes the area we have defined as the rapNTS, or whether afferent CT fibers terminate more caudally in females during conditions of elevated estrogen. If so, estrogen effects on the number of HSD2 neurons in the rapNTS could be related to differences in the processing of salt taste information. Clearly, further studies will be necessary to evaluate the functional significance of the EB-mediated increase in the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the rapNTS, to determine whether ERs and HSD2 colocalize in NTS neurons, particularly in those that receive gastric vagal input, and to systematically compare the density of HSD2 labeling throughout the NTS among Male rats and OVX rats with or without EB treatment. Nonetheless, the present findings are consistent with sex differences in NaCl ingestion that involve an interaction between estrogens and HSD2 neurons in the rapNTS which, in turn, may underlie the greater NaCl intake by female rats during high estrogen conditions.

DBH immunolabeling

DBH immunolabeling also depended on the level of the NTS. The number of DBH immunoreactive neurons was greatest in the apNTS, least in the rapNTS, and intermediate in the capNTS (see also Curran-Rauhut and Petersen, 2003) and this pattern was evident in all three groups. However, the number of DBH immunoreactive neurons was lowest overall in OIL-treated OVX rats, and did not differ between EB-treated OVX rats and Male rats. It is possible that estrogens regulate the level of DBH, indicated by the number of DBH immunoreactive neurons, such that either EB treatment or the low estrogens present in male rats results in comparable numbers of DBH immunoreactive neurons within the NTS, whereas the number decreases absent estrogens (i.e., in OIL-treated OVX rats). Consistent with this idea, previous studies have shown that estrogens alter the expression of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes in the brainstem (Curran-Rauhut and Petersen, 2003; Liaw et al., 1992; Sabban et al., 2010; Serova et al., 2004; Serova et al., 2005). However, caution must be exercised in generalizing from those studies to the present for several reasons, not the least of which is that we have labeled DBH in situ, while others examined gene expression or mRNA, often using tissue homogenates. In addition, many previous studies focused exclusively on tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate limiting enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis. On the surface, this would appear to be a reasonable strategy; however, EB treatment has differential effects on the expression of TH and DBH in cell cultures (Sabban et al., 2010) and in specific central areas (Serova et al., 2005). Moreover, EB effects on TH depend on the dose and route of EB administration, and may be influenced by the duration of EB treatment (Serova et al., 2004). Finally, although sex differences in TH (or DBH) levels have been largely unexamined, Thanky and colleagues (Thanky et al., 2002) reported that gonadectomy had opposite effects on TH expression in the LC of male and female mice, as did estrogen replacement using an intermittent injection protocol similar to ours. These qualifications notwithstanding, our results show that the number of DBH immunoreactive cells in the NTS is modestly affected by EB treatment. Thus, given that ~30-50% of ERs in the NTS colocalize with TH (Curran-Rauhut and Petersen, 2003) and that NE is important in the control of vasopressin release (Buller et al., 1996; Gieroba et al., 1994), it seems possible that EB-induced changes in the number of DBH-containing neurons within the NTS may play a small role in the effect of estrogens on vasopressin release (Bossmar et al., 1995; Forsling and Peysner, 1988; Hartley et al., 2004; Stachenfeld et al., 1998).

Double-immunolabeling

Previous studies have reported no co-localization of HSD2 with other neural phenotypes or with markers for neural phenotypes, including TH (Geerling et al., 2006b; Geerling and Loewy, 2006b). Although it may, therefore, seem unlikely that EB-mediated sex differences in HSD2-DBH double-immunolabeling would exist, a systematic examination of possible sex differences was not conducted in those previous studies. Certainly, effects specific to estrogens were not investigated, even though ERs have been localized to the NTS (Estacio et al., 1996; Schlenker and Hansen, 2006; Simonian and Herbison, 1997). Several additional observations argued against ignoring the possibility of EB effects on HSD2-DBH co-localization in the NTS. First, estrogens alter both basal and stimulated NaCl intake (Curtis et al., 2004; Danielsen and Buggy, 1980; Fregly, 1973; Kensicki et al., 2002; Scheidler et al., 1994), and vasopressin release (Buller et al., 1996; Gieroba et al., 1994). Importantly, given the relationship of NE to vasopressin release, estrogens also influence catecholamines in the brainstem (Curran-Rauhut and Petersen, 2003; Liaw et al., 1992; Sabban et al., 2010; Serova et al., 2004; Serova et al., 2005) and, as mentioned, this latter effect of estrogens appears to depend upon the specific catecholamine biosynthetic enzyme (Sabban et al., 2010; Serova et al., 2005). Accordingly, we examined the possibility of estrogen-mediated sex differences in HSD2-DBH co-localization within neurons of the NTS.

We observed neurons immunolabeled for both HSD2 and DBH throughout the NTS. Admittedly, the number of double-labeled neurons was small, both as absolute numbers (1-5 in the rapNTS; 4-7 in the capNTS; 6-10 in the apNTS) and as a percentage of HSD2 neurons (~20-30%). Nonetheless, there were double-labeled neurons, even in male rats. In the rapNTS, HSD2 immunoreactive neurons were primarily located adjacent to the 4th ventricle, while DBH immunoreactive neurons were smaller in number and located somewhat more laterally. Because there was so little overlap in the distributions, there was a correspondingly low number of double-labeled neurons in the rapNTS. The number of neurons immunolabeled for both HSD2 and DBH also was comparatively low in the capNTS, despite considerable overlap in the distributions of HSD2 immunoreactive and DBH immunoreactive neurons. Taken as a whole, the greatest number of double-labeled neurons was in the apNTS; however, closer examination revealed differences in the medial-lateral distribution of immunolabeled neurons in the apNTS. Approximately ~75% of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons were located in the commissural NTS subadjacent to the AP, but few DBH immunoreactive neurons were located there. Thus, although the majority of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the apNTS were located in the midline V, very few of these neurons also were labeled for DHB. In contrast, the distributions of HSD2 immunoreactive and DBH immunoreactive neurons in more lateral portions of the apNTS overlapped substantially and, despite the smaller number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons located there, a larger number of these neurons also was labeled for DBH.

It has been proposed that HSD2 neurons represent a unique phenotype, based on findings that these neurons do not co-localize with other neurotransmitters, or with markers for neurotransmitters (Geerling et al., 2006b; Geerling and Loewy, 2006b). Given the results of previous studies, it is tempting to discount the present findings of double-labeled neurons as being too small a number to be meaningful, despite the inevitable ensuing debate over how many neurons is enough (or not enough) after such a statement. Alternatively, methodological differences may account for discrepancies between the present study and previous ones. This is not a trivial possibility, as there are substantive methodological differences, ranging from differences in the treatment of the tissue prior to immunohistochemical processing (post-fixed 24 h vs. post-fixed 3-10 days; storage in cryoprotectant vs. not (see (Watson et al., 1986) for a discussion of the effects of cryoprotectants) to the antibodies used (primary antibodies: Santa Cruz vs. Chemicon, which differ in host species, as well as in n-terminus vs. c-terminus epitope targets; secondary antibodies/fluorophores: Cy3 vs. Marina blue (Geerling and Loewy, 2006b), which differ in intensity and, therefore, in the possibility of ‘bleed-through’ or low sensitivity, respectively). However, we suspect that the discrepancies are, in part, the result of labeling different enzymes in the NE biosynthetic pathway (DBH vs. TH), as discussed above. In any case, the present study shows that HSD2 and DBH co-localize in neurons throughout the NTS, albeit in a small number of neurons that tend to be located in somewhat more lateral aspects of the apNTS.

This finding raises the possibility that there are different sub-populations of HSD2 neurons that serve different functions. Thus, for example, HSD2 neurons in the commissural NTS subadjacent to the AP—the ‘midline V’—likely are involved in NaCl intake (see Geerling et al., 2006a; Geerling and Loewy, 2006a; Geerling and Loewy, 2007; Geerling and Loewy, 2008), whereas the small sub-population of HSD2-DBH double immunolabeled neurons located somewhat more laterally in apNTS may serve a different function. Based on previous studies (Buller et al., 1996; Gieroba et al., 1994), one possibility is that this small group contributes to vasopressin release. Interestingly, however, there were no sex differences in the number of double-labeled neurons, and no effect of EB treatment. Thus, whatever the functional role of NTS neurons immunolabeled for both HSD2 and DBH, it would seem to be unlikely to be important in estrogen-mediated sex differences in vasopressin secretion (Bossmar et al., 1995; Forsling and Peysner, 1988; Hartley et al., 2004; Stachenfeld et al., 1998). Clearly, additional studies will be necessary to delineate the roles of these sub-populations of HSD2 neurons in the NTS and to provide further insights into the mechanism by which these HSD2 neurons may contribute to the effects of estrogens on NaCl ingestion and body sodium balance.

Summary and conclusions

Little is known about the central mechanisms that underlie NaCl ingestion. Even less is known about how estrogens influence these central mechanisms, and thereby affect behaviors that ultimately impact body fluid regulation. These are critical oversights, as the knowledge to be gained could provide important insights, not only about central involvement in body fluid changes across the female reproductive cycle, and in the necessary body fluid adaptations that occur during pregnancy, but also, more generally, about cardiovascular function and dysfunction. Here, we report that EB treatment increases the number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons in the NTS immediately rostral to the AP. These differences may contribute to the influence of estrogens on spontaneous NaCl intake, and possibly to EB-mediated differences in NaCl intake stimulated by a variety of experimental manipulations. The question of whether estrogens contribute to differential activation of HSD2 neurons during stimulated NaCl ingestion remains an open question, as does the question of whether these neurons are differentially sensitive to the consequences of NaCl ingestion. More specifically, do HSD2 neurons ‘shut off’ more or less rapidly during NaCl intake when estrogens are present? If so, are EB-mediated differences in the processing of NaCl taste a factor? Or do EB effects on the number of HSD2 neurons in the rapNTS involve the modulation of input from the gastrointestinal tract or from baroreceptors? Further information about where these neurons project and about the functional significance of colocalization with neurotransmitters such as NE undoubtedly will provide important information about the mechanism by which HSD2 neurons and estrogens interact to influence NaCl ingestion and body sodium regulation.

4. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River) weighing 250-350 g and adult male rats (Charles River) weighing 350-500 g were individually housed in a temperature controlled (22 ± 2° С) room on a 12:12 light:dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 A.M.). All rats were given ad libitumaccess to water and Harlan rodent diet (#2018). Experimental protocols were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and all procedures were approved by the Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee.

Ovariectomy and estrogen replacement

Female rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg body weight, I.P.; Sigma-Aldrich), bilaterally ovariectomized (OVX) using a ventral approach, and allowed 7-10 days to recover. OVX rats then were given either 17-β-estradiol-3-benzoate (EB; Fisher Scientific; 10 μg in 0.1 ml sesame oil, s.c.) or the oil vehicle (OIL; 0.1 ml, s.c.) on day 1 and day 2 of a 4-day estrogen replacement protocol. We and others (Jones and Curtis, 2009; Kisley et al., 1999) have used this protocol to mimic the pattern of estrogen fluctuations during the estrous cycle. EB- and OIL-treated OVX rats were weighed on day 1 and day 2.

Perfusion and tissue extraction

On day 4, EB-treated OVX rats (n = 7), OIL-treated OVX rats (n = 6), and male rats (n = 6) were weighed, deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/rat, I.P.), and then perfused with 0.15 M NaCl followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in a 0.1 M phosphate buffer. Brains were removed, placed in paraformaldehyde overnight, and then transferred to a 30% sucrose solution for 48 hrs. Brains were cut in a 1-to-3 series of 40-μm coronal sections using a cryostat. Thus, sections were separated by ~120 μm. Sections were stored in a cryoprotectant solution (Watson et al., 1986) at -20° C until processed.

The uteri of OVX rats were removed immediately prior to perfusion and placed in 0.15 M NaCl. Subsequently, uteri were stripped of fat and vascular tissue; a 10-mm section was cut from one uterine horn adjacent to the bifurcation and weighed.

Immunohistochemistry

One series of free-floating hindbrain sections from each rat was rinsed in 0.05 M Tris-NaCl and blocked in 10% normal goat serum (NGS; in 0.05 M Tris-NaCl containing 0.5% Triton X-100) for 1 hr. Sections then were incubated for 72 hr at 4° C in the HSD2 primary antibody (Santa Cruz; rabbit anti-HSD2, raised against a.a. 261-405 at the c-terminus of 11-β-HSD2 of human origin) diluted 1:500 in 2% NGS. HSD2 labeling was visualized by incubating with a Cy2-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch; diluted 1:200 in 2% NGS) for 6 hr at room temperature. Sections then were processed to label dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH), an enzyme involved in NE biosynthesis, as a marker for NE-containing neurons. Sections were incubated in the DBH primary antibody (mouse anti-DBH; Chemicon; diluted 1:1,000 in 2% NGS) for 48 hrs at 4° C. DBH immunolabeling was visualized by incubating in a Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch; diluted 1:300 in 2% NGS) for 6 hrs at room temperature. Sections were rinsed in 2% NGS, and in 0.05 M Tris-NaCl, then mounted on microscope slides and coverslipped using Cytoseal 60 (Fisher Scientific).

In preliminary evaluations, we noted little HSD2 labeling in brainstem areas other than the NTS, with the exception of a small number of HSD2 immunolabeled neurons in the medial vestibular nucleus (not shown). These findings are consistent with previous studies, as are the patterns of labeling we observed within the NTS (Geerling et al., 2006a; Geerling et al., 2006b; Geerling and Loewy, 2006b; see also Roland et al., 1995). It should be noted, however, that the focus of this study was HSD2 immunolabeling in the NTS and the implications for estrogen-mediated sex differences in NaCl ingestion: thus, we have reported only on the labeling in the NTS.

Quantification of immunoreactivity in the NTS

An epifluorescent microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i) equipped with FITC and rhodamine filters was used to visualize HSD2 and DBH immunolabeling, respectively, in the NTS at three levels along the rostral-caudal plane. These gross anatomical levels were defined in the context of their relation to AP as follows: the NTS caudal to AP ( -14.20 - -14.60 mm relative to bregma) was defined as capNTS; the NTS at the level of AP (-13.60 - -14.10 mm relative to bregma) was defined as apNTS; the NTS immediately rostral to AP (-13.20 - -13.50 mm relative to bregma) was defined as rapNTS. NIS Elements imaging software (Nikon) was used to quantify the number of HDS2 immunoreactive neurons, the number of DBH immunoreactive neurons, and the number of double-labeled neurons in 2-3 representative sections from each of these areas that were matched between subjects. Under fluorescent microscopy, HSD2 immunoreactivity appears as bright green accumulation in neuronal cytoplasm and processes, whereas DBH immunoreactivity appears as bright red accumulation in neuronal cytoplasm and processes (Figure 1). NIS Elements software was used to overlay these images; thus, double-labeled neurons appear as bright yellow-orange (Figure 2). Counts were taken bilaterally in each area and were averaged for each rat in each area. Group means (HSD2 immunoreactive neurons, DBH immunoreactive neurons, and double-labeled neurons) were calculated for each area.

In seminal studies (Geerling et al., 2006a; Geerling et al., 2006b; Geerling and Loewy, 2006b), Geerling and Loewy showed that the majority of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons occupy a V-shaped profile in the commissural NTS immediately subadjacent to AP (see also Roland et al., 1995). These neurons demonstrate particularly robust immunolabeling and are reliably activated by experimental treatments that stimulate NaCl ingestion. Accordingly, in the apNTS, we also classified HSD2 immunoreactive and double-labeled immunoreactive neurons as being in the ‘midline V’ or in the lateral portion of the HSD2 population (see Figure 4) and counted these neurons separately.

Figure 4.

Representative digital photomicrographs of HSD2 (top), DBH (middle), and double (bottom) immunolabeling in the apNTS. Area in box shows double immunolabeled neurons and is shown at higher magnification at the left. Green shading in the line drawing of the hindbrain indicates apNTS. dmv = dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; AP = area postrema; midline V = area of intensely labeled HSD2 neurons. scale bars - 50 μm (right panels) or 20 μm (left panels).

Statistics

All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M.

Numbers of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons, DBH immunoreactive neurons, and double-labeled neurons were compared using 2-way repeated measures analysis of variance (rm ANOVA; Statistic, StatSoft), with group (EB, OIL, male) and level (capNTS, apNTS, rapNTS) as factors, repeated for level. Number of HSD2 immunoreactive neurons and double-labeled neurons in the midline V vs the more lateral portion of the apNTS were compared using 2-way rm ANOVA, with group (EB, OIL, male) and distribution (midline V, lateral) as factors, repeated for distribution. Pairwise comparisons of significant (p<0.05) main effects or interactions were conducted using Student-Newman-Keuls tests.

Changes in body weight in EB- and OIL-treated OVX rats were calculated as percent change [(day 4 weight - day 1 weight)/day 1 weight]*100; these data were compared using t-tests. Uterine weights in EB- and OIL-treated OVX rats also were compared using t-tests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders (DC-06360) and the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (HR09-123S). Preliminary versions of portions of these data were presented at the annual meetings of the Society for the Study of Ingestive Behaviors (Portland, OR; July, 2009) and of the Society for Neuroscience (Chicago, IL; October, 2009). We thank Ms. Jennifer Hackett and Ms. Minh Ngo for assistance with animal handling and analyses of uteri.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

During baseline, numbers of HSD2 neurons in NTS of rat varied with region and sex.

During baseline, numbers of HSD2 neurons in NTS of rat varied with region and sex. EB-treated OVX rats had more HSD2 neurons in the NTS immediately rostral to AP.

EB-treated OVX rats had more HSD2 neurons in the NTS immediately rostral to AP. A small number of HSD2 neurons also was labeled for DBH, but without an effect of EB.

A small number of HSD2 neurons also was labeled for DBH, but without an effect of EB. The function of HSD2 neurons may depend on their specific phenotype or on estrogens.

The function of HSD2 neurons may depend on their specific phenotype or on estrogens.

REFERENCES

- Alves SE, Lopez V, McEwen BS, Weiland NG. Differential colocalization of estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) with oxytocin and vasopressin in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the female rat brain: An immunocytochemical study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:3281–3286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn RE, Samson WK, Fulton RJ, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Central oxytocin and ANP receptors mediate osmotic inhibition of salt appetite in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:R245–251. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.2.R245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossmar T, Forsling M, Akerlund M. Circulating oxytocin and vasopressin is influenced by ovarian steroid replacement in women. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1995;74:544–548. doi: 10.3109/00016349509024387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buller KM, Khanna S, Sibbald JR, Day TA. Central noradrenergic neurons signal via ATP to elicit vasopressin responses to haemorrhage. Neuroscience. 1996;73:637–642. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow SY, Sakai RR, Witcher JA, Adler NT, Epstein AN. Sex and sodium intake in the rat. Behav. Neurosci. 1992;106:172–180. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.1.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras RJ, Gomez MM, Norgren R. Central origins of cranial nerve parasympathetic neurons in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1980;190:373–394. doi: 10.1002/cne.901900211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran-Rauhut MA, Petersen SL. Oestradiol-dependent and -independent modulation of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA levels in subpopulations of A1 and A2 neurones with oestrogen receptor (ER)alpha and ER beta gene expression. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:296–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis KS, Davis LM, Johnson AL, Therrien KL, Contreras RJ. Sex differences in behavioral taste responses to and ingestion of sucrose and NaCl solutions by rats. Physiol. Behav. 2004;80:657–664. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis KS, Contreras RJ. Sex differences in electrophysiological and behavioral responses to NaCl taste. Behav. Neurosci. 2006;120:917–924. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.4.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis KS. Estrogen and the central control of body fluid balance. Physiol. Behav. 2009;97:180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney RA. Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol. Rev. 1994;74:323–364. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen J, Buggy J. Depression of ad lib and angiotensin-induced sodium intake at oestrus. Brain Res. Bull. 1980;5:501–504. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(80)90253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gobbi JIF, Martinez G, Barbosa SP, Beltz TG, De Luca LA, Jr, Thunhorst RL, Johnson AK, Vanderlei Menani J. 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors in the lateral parabrachial nucleus mediate opposite effects on sodium intake. Neuroscience. 2007;146:1453–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estacio MA, Tsukamura H, Yamada S, Tsukahara S, Hirunagi K, Maeda K. Vagus nerve mediates the increase in estrogen receptors in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and nucleus of the solitary tract during fasting in ovariectomized rats. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;208:25–28. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluharty SJ, Epstein AN. Sodium appetite elicited by intracerebroventricular infusion of angiotensin II in the rat: II. Synergistic interaction with systemic mineralocorticoids. Behav. Neurosci. 1983;97:746–758. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.97.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsling ML, Peysner K. Pituitary and plasma vasopressin concentrations and fluid balance throughout the oestrous cycle of the rat. J. Endocrinol. 1988;117:397–402. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1170397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregly MJ. Effect of an oral contraceptive on NaCl appetite and preference threshold in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1973;1:61–65. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(73)90056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling JC, Engeland WC, Kawata M, Loewy AD. Aldosterone target neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius drive sodium appetite. J. Neurosci. 2006a;26:411–417. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3115-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling JC, Kawata M, Loewy AD. Aldosterone-sensitive neurons in the rat central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006b;494:515–527. doi: 10.1002/cne.20808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling JC, Loewy AD. Aldosterone-sensitive NTS neurons are inhibited by saline ingestion during chronic mineralocorticoid treatment. Brain Res. 2006a;1115:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling JC, Loewy AD. Aldosterone-sensitive neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract: Efferent projections. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006b;497:223–250. doi: 10.1002/cne.20993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling JC, Loewy AD. Aldosterone-sensitive neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract: Bidirectional connections with the central nucleus of the amygdala. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006c;497:646–657. doi: 10.1002/cne.21019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling JC, Loewy AD. Sodium depletion activates the aldosterone-sensitive neurons in the NTS independently of thirst. Am. J. Physiol. 2007;292:R1338–1348. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00391.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling JC, Chimenti PC, Loewy AD. Phox2b expression in the aldosterone-sensitive HSD2 neurons of the NTS. Brain Res. 2008;1226:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.05.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling JC, Loewy AD. Central regulation of sodium appetite. Exp. Physiol. 2008;93:177–209. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.039891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling JC, Shin JW, Chimenti PC, Loewy AD. Paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus: Axonal projections to the brainstem. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010;518:1460–1499. doi: 10.1002/cne.22283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieroba ZJ, Shapoval LN, Blessing WW. Inhibition of the A1 area prevents hemorrhage-induced secretion of vasopressin in rats. Brain Res. 1994;657:330–332. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90986-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley DE, Dickson SL, Forsling ML. Plasma vasopressin concentrations and fos protein expression in the supraoptic nucleus following osmotic stimulation or hypovolaemia in the ovariectomized rat: Effect of oestradiol replacement. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:191–197. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-8194.2004.01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AK, Thunhorst RL. The neuroendocrinology of thirst and salt appetite: Visceral sensory signals and mechanisms of central integration. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1997;18:292–353. doi: 10.1006/frne.1997.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AB, Curtis KS. Differential effects of estradiol on drinking by ovariectomized rats in response to hypertonic NaCl or isoproterenol: Implications for hyper- vs. Hypoosmotic stimuli for water intake. Physiol. Behav. 2009;98:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensicki E, Dunphy G, Ely D. Estradiol increases salt intake in female normotensive and hypertensive rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002;93:479–483. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00554.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisley LR, Sakai RR, Ma LY, Fluharty SJ. Ovarian steroid regulation of angiotensin II-induced water intake in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:R90–96. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.1.R90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krecek J, Novakova V, Stibral K. Sex differences in the taste preference for a salt solution in the rat. Physiol. Behav. 1972;8:183–188. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(72)90358-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krecek J. Sex differences in salt taste: The effect of testosterone. Physiol. Behav. 1973;10:683–688. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(73)90144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw JJ, He JR, Hartman RD, Barraclough CA. Changes in tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA levels in medullary A1 and A2 neurons and locus coeruleus following castration and estrogen replacement in rats. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1992;13:231–238. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May OL, Hill DL. Gustatory terminal field organization and developmental plasticity in the nucleus of the solitary tract revealed through triple-fluorescence labeling. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006;497:658–669. doi: 10.1002/cne.21023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naray-Fejes-Toth A, Colombowala IK, Fejes-Toth G. The role of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in steroid hormone specificity. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1998;65:311–316. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(98)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota M, Crofton JT, Liu H, Festavan G, Share L. Increased plasma osmolality stimulates peripheral and central vasopressin release in male and female rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:R923–928. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.4.R923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechere-Bertschi A, Burnier M. Female sex hormones, salt, and blood pressure regulation. Am. J. Hypertens. 2004;17:994–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaman L. Visceral sensory inputs to the endocrine hypothalamus. Front.Neuroendocrinol. 2007;28:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roitman MF, Na E, Anderson G, Jones TA, Bernstein IL. Induction of a salt appetite alters dendritic morphology in nucleus accumbens and sensitizes rats to amphetamine. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:1–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-j0001.2002. RC225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland BL, Li KX, Funder JW. Hybridization histochemical localization of 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 in rat brain. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4697–4700. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Arellano MP, Solano-Flores LP, Ciriello J. Co-localization of estrogen and angiotensin receptors within subfornical organ neurons. Brain Res. 1999;837:254–262. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL, Maharjan S, Nostramo R, Serova LI. Divergent effects of estradiol on gene expression of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes. Physiol. Behav. 2010;99:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidler MG, Verbalis JG, Stricker EM. Inhibitory effects of estrogen on stimulated salt appetite in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 1994;108:141–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker EH, Hansen SN. Sex-specific densities of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in the subnuclei of the nucleus tractus solitarius, hypoglossal nucleus and dorsal vagal motor nucleus weanling rats. Brain Res. 2006;1123:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira SM, Geerling JC, Loewy AD. Local inputs to aldosterone-sensitive neurons of the nucleus tractus solitarius. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1995–2005. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serova LI, Maharjan S, Huang A, Sun D, Kaley G, Sabban EL. Response of tyrosine hydroxylase and GTP cyclohydrolase I gene expression to estrogen in brain catecholaminergic regions varies with mode of administration. Brain Res. 2004;1015:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serova LI, Maharjan S, Sabban EL. Estrogen modifies stress response of catecholamine biosynthetic enzyme genes and cardiovascular system in ovariectomized female rats. Neuroscience. 2005;132:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J-W, Geerling JC, Loewy AD. Vagal innervation of the aldosterone-sensitive HSD2 neurons in the nts. Brain Res. 2009;1249:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J-W, Loewy AD. Gastric afferents project to the aldosterone-sensitive HSD2 neurons of the NTS. Brain Res. 2009;1301:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonian SX, Herbison AE. Differential expression of estrogen receptor and neuropeptide Y by brainstem A1 and A2 noradrenaline neurons. Neuroscience. 1997;76:517–529. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00406-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladek CD, Somponpun SJ. Estrogen receptors: Their roles in regulation of vasopressin release for maintenance of fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:114–127. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somponpun SJ, Johnson AK, Beltz T, Sladek CD. Estrogen receptor-alpha expression in osmosensitive elements of the lamina terminalis: Regulation by hypertonicity. Am. J. Physiol. 2004;287:R661–669. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00136.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somponpun SJ. Neuroendocrine regulation of fluid and electrolyte balance by ovarian steroids: Contributions from central oestrogen receptors. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19:809–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachenfeld NS, DiPietro L, Palter SF, Nadel ER. Estrogen influences osmotic secretion of AVP and body water balance in postmenopausal women. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:R187–195. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.1.R187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanky NR, Son JH, Herbison AE. Sex differences in the regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene transcription by estrogen in the locus coeruleus of TH9-LacZ transgenic mice. Mol. Brain Res. 2002;104:220–226. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DL, Simonian SX, Herbison AE. Identification of estrogen receptor-containing neurons projecting to the rat supraoptic nucleus. Neuroscience. 1997;78:215–228. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00551-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RE, Jr., Wiegand SJ, Clough RW, Hoffman GE. Use of cryoprotectant to maintain long-term peptide immunoreactivity and tissue morphology. Peptides. 1986;7:155–159. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(86)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf G. Refined salt appetite methodology for rats demonstrated by assessing sex differences. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1982;96:1016–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]