Abstract

Objective

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) is known to play an important role in the vasculature. However, the role of PPARγ in abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) is not well understood. We hypothesized that PPARγ in smooth muscle cells attenuates the development of AAA. In this study, we also investigated PPARγ-mediated signaling pathways that may prevent the development of AAA.

Methods and Results

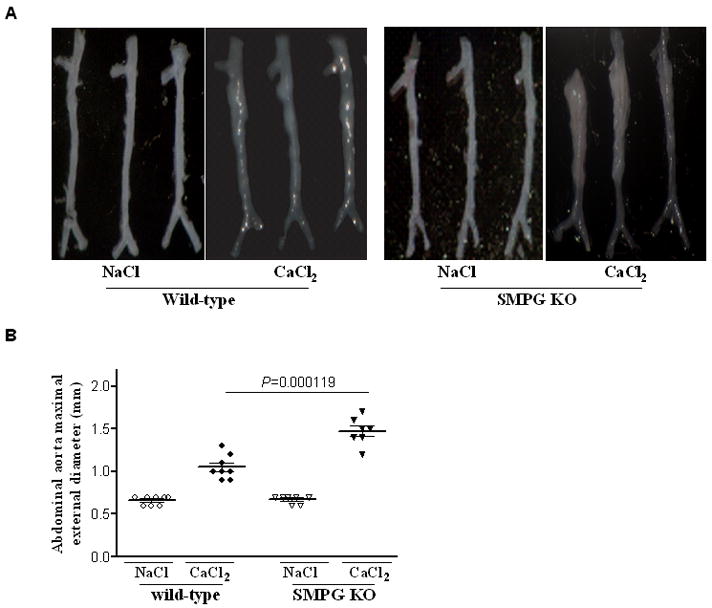

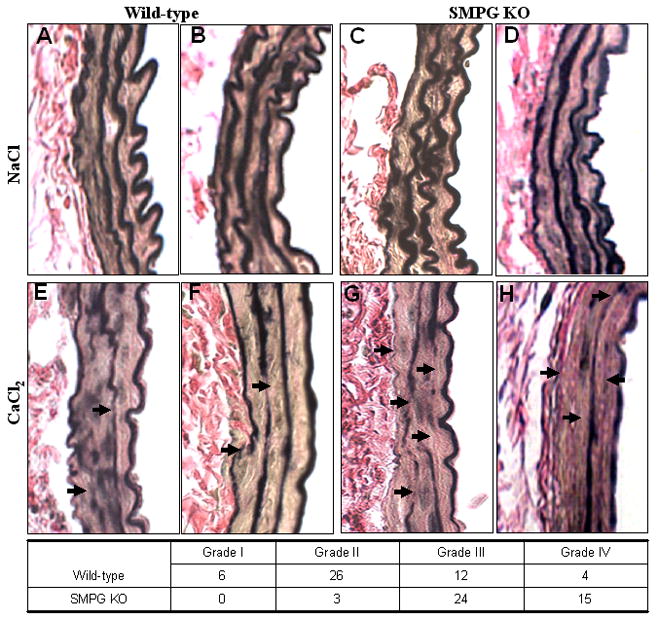

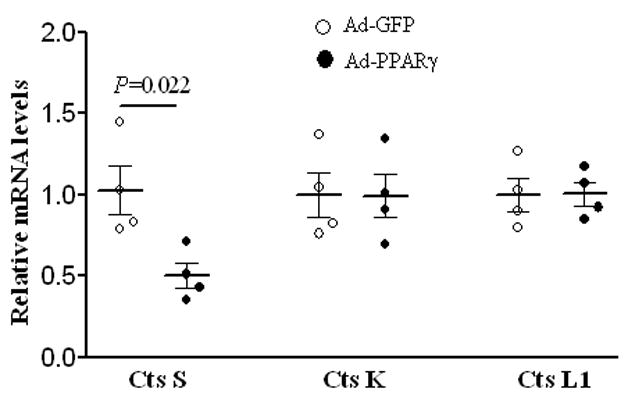

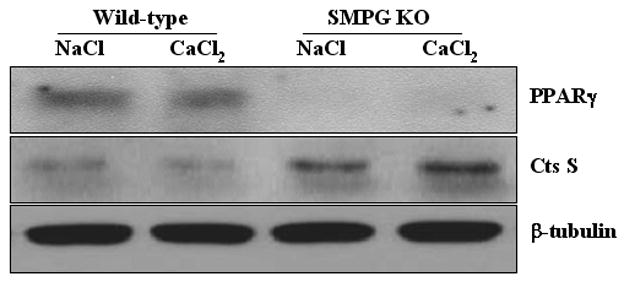

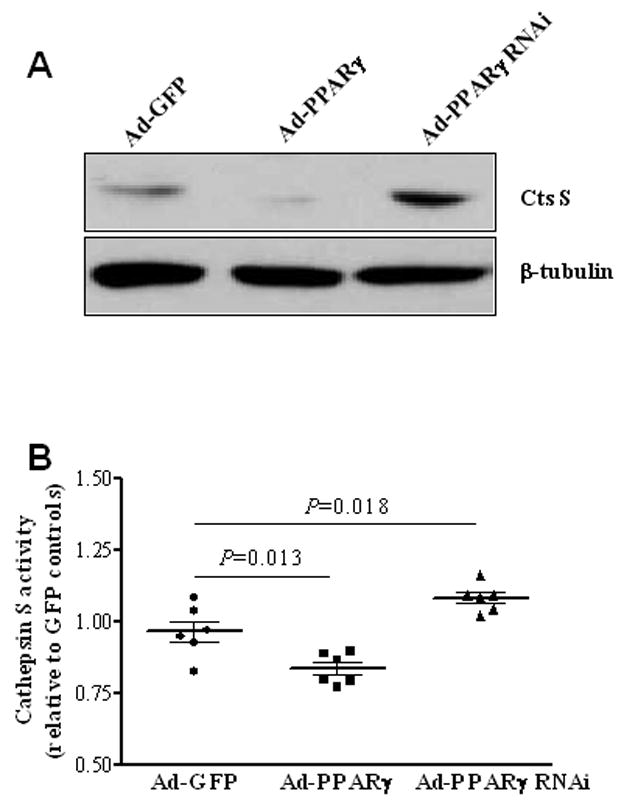

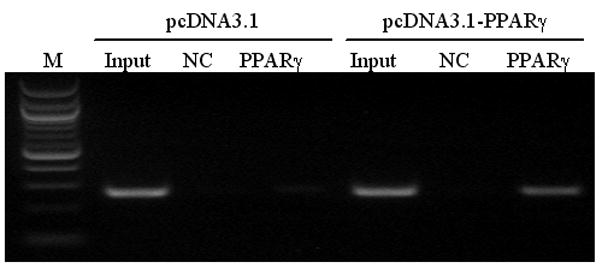

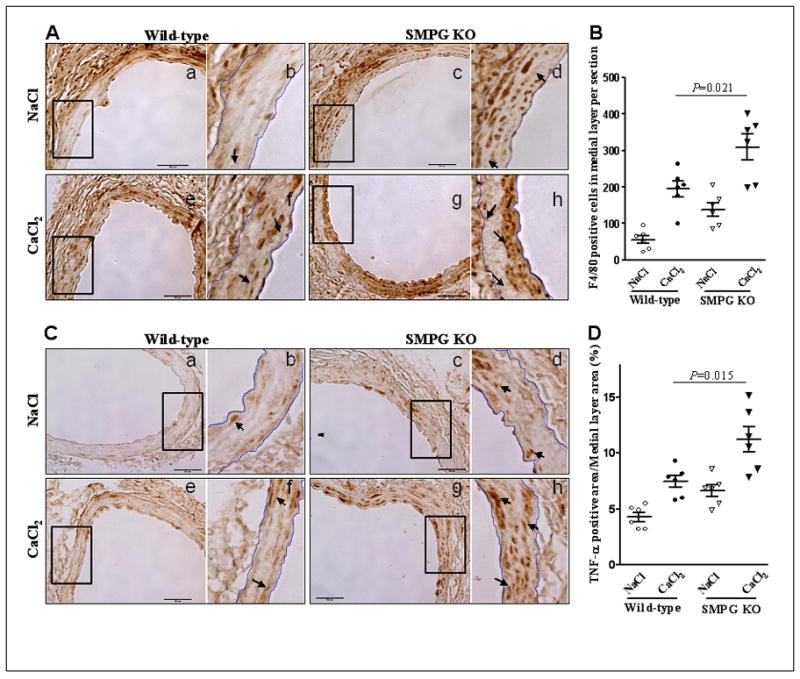

In the present study, we determined whether periaortic application of CaCl2 renders vascular smooth muscle cell-selective PPARγ knockout (SMPG KO) mice more susceptible to destruction of normal aortic wall architecture. There is evidence of increased vessel dilatation in the abdominal aorta six weeks after 0.25 M periaortic CaCl2 application in SMPG KO mice compared to littermate controls (1.4±0.3 mm, n=8 versus 1.1±0.2 mm, n=7; P = .000119). Furthermore, results from SMPG KO mice indicate medial layer elastin degradation was greater six weeks after abluminal application of CaCl2 to the abdominal aorta (P <.01). Next, we found that activated cathepsin S, a potent elastin-degrading enzyme, is increased in SMPG KO mice when compared to wild-type controls. To further identify a role of PPARγ signaling in reducing the development of AAA, we demonstrated that adenoviral-mediated PPARγ overexpression in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells decreases (P = .022) the mRNA levels of cathepsin S. In addition, a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay detected PPARγ bound to a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor response element (PPRE) −141 to −159 bp upstream of the cathepsin S gene sequence in mouse aortic smooth muscle cells. Also, adenoviral-mediated PPARγ overexpression and knockdown in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells decreases (P = .013) and increases (P = .018) expression of activated cathepsin S. Finally, immunohistochemistry demonstrated a greater inflammatory infiltrate in SMPG KO mouse aortas, as evidenced by elevations in F4/80 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression.

Conclusion

In this study, we identify PPARγ as an important contributor in attenuating the development of aortic aneurysms by demonstrating that loss of PPARγ in vascular smooth muscle cells promotes aortic dilatation and elastin degradation. Thus, PPARγ activation may be potentially promising medical therapy in reducing the risk of AAA progression and rupture.

INTRODUCTION

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) are a complex, vascular disorder and a common cause of mortality in the United States today in individuals age 55 and older (1). Statistics reveal the mortality rate of AAA due to aortic rupture is greater than 80% (2). Abdominal aortic aneurysms are often considered to be connective tissue disorders since the pathophysiological and structural complexity of this disease is associated with degradation and/or complete destruction of extracellular matrix proteins located in the vessel wall. In particular, alterations in vascular wall elastin and collagen contribute to AAA initiation and progression (3).

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) is a ligand-activated transcription factor that belongs to the nuclear receptor superfamily. Several studies have demonstrated that PPARγ is expressed in vascular cells (4–6). Moreover, PPARγ plays a functional role in the vasculature either through direct or indirect regulation of gene expression (7). Recent evidence establishes a critical role of vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) PPARγ in restenosis and atherosclerosis (8, 9), in addition to blood pressure regulation (10–13). However, the function of PPARγ in AAA has not been delineated.

The opportunity exists for studying PPARγ signaling pathways involved in delaying the onset of AAA and eventual rupture. First, PPARγ has been shown to reduce extracellular matrix proteases (5, 6). Second, PPARγ facilitates many of the effects of angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARB) (14), drugs that are used to treat hypertension and other clinical abnormalities in patients. A recent cohort study suggests that administering losartan or other ARBs may be effective in treating aortic aneurysms in Marfan’s Syndrome patients (15). Third, PPARγ is recognized as the major target of thiazolidinediones (TZD) (16), insulin-sensitizing compounds that are clinically used for treating diabetes (17). Two recent studies provide evidence that rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, TZDs with high-affinity PPARγ binding, are beneficial in experimentally reducing AAA (18, 19). These studies suggest PPARγ should be carefully considered as a potential candidate for drug targeting strategies in the treatment of cardiovascular disorders, including the pathogenic events resulting in AAA. However, the role of PPARγ-dependent signaling in attenuating AAA progression must be first established.

In the present investigation, we examined the effects of vascular smooth muscle cell PPARγ on abdominal aortic dilatation in vascular smooth muscle cell-selective PPARγ knockout (SMPG KO) mice. Using an experimental aortic aneurysm model previously described (20–22), our data suggest that VSMC PPARγ is a contributing factor in delaying aneurysmal degeneration. Furthermore, the findings from this investigation lend strong support in favor of a clinically beneficial role for PPARγ against the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Methods

Mouse Models

The groups for this particular study were as follows: 1) VSMC–selective PPARγ conditional knockout (SMPG KO) mice with a genotype of SM22α-Cre-knock-in heterozygous and PPARγ-floxed homozygous (SM22αCre/+/PPARγflox/flox), and 2) wild-type control mice. The experiments in this study were performed using age- and weight-matched male mice (12 weeks of age). Experimental animals were housed in a temperature-controlled environment with a 12:12 hour light-dark cycle and access to water and rodent chow ad libitum. The generation of SMPG KO has been previously described (10). This study was conducted under the approval of the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the University of Michigan.

Induction of Aneurysm

SMPG KO and wild-type mice were anesthetized by injecting a combination of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) in 0.9% saline. The protocol for inducing abdominal aortic aneurysms has been reported previously (20, 21). Briefly, the mice underwent a laparotomy and the area between the renal arteries and the iliac bifurcation was separated from the nearest retroperitoneal structures. 0.25 M CaCl2 was applied for 15 minutes to the surface of the aorta in SMPG KO and wild-type mice. An equimolar concentration of NaCl served as the control. Afterwards, the aorta was rinsed with 0.9% saline before closing the incision in multiple layers with absorbable sutures. For post-operative pain, mice were treated twice daily with 0.1–0.5 mg/kg Buprenorphine for 24–72 hours. This method was conducted under the approval of the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals at the University of Michigan.

Tissue Collection

Six weeks after periaortic application, whole-body perfusion fixation was performed in mice and the infrarenal portion of the aorta was isolated and removed. Measurements of the external infrarenal diameter were made with a ruler and surgical micro-caliper to the nearest tenth of a millimeter. The excised aortas were photographed and immediately immersed in formalin. For the one week in vivo study, aortas of SMPG KO and wild-type mice were harvested following anesthetization and saline perfusion. Three animals served as one pooled sample to perform Western blot.

Histological Analysis

After fixation with 4% paraformalin overnight, the aortic tissue was dehydrated through an alcohol gradient of 30-, 50- and 70% ethanol. Next, the aortas were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5 μm sections. We analyzed 6 serial sections at 300 μm intervals for each vessel. The effects of PPARγ deletion on medial layer elastin disruption were compared using sections from SMPG KO and wild-type mouse aortas. Cross-sections were stained with a standard protocol for elastic Van Gieson (Sigma-Aldrich, HT25A-1KT, Lot# 056K4340). Digital images were obtained using an Olympus BX51 light microscope. Sections showing pathogenesis were graded on a scale of 1–4 by a blinded observer. A score of 1 signifies mild elastic fiber disruption while a score of 4 signifies severe elastic disruption (Supplemental Figure I).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical labeling was performed as previously described (23). Sections were incubated with F4/80 (Abcam, ab6640) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (Santa Cruz, sc-52746) antibodies overnight. Primary antibody detection was performed using proper avidin-biotin complex (ABC) staining systems (Santa Cruz, sc-2019 and sc-2023).

Cell culture

All cell culture experiments were performed by preparing rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RASMCs) as previously mentioned (24). Seven passages were performed and grown to 80% confluence. The cells were then transfected with Ad-GFP, Ad-PPARγ, or Ad-PPARγ RNAi for 4 hours followed by a switch to growth medium for 24 hours. Next, the cells were harvested and mRNA was isolated for mRNA assay.

Western blot

Western blot analyses for the proteins in this study were performed using standard methods as previously described (25). Protein extracts were obtained either from cultured VSMCs or directly from dissected aortic medial layer tissue as described above. Membranes were incubated with rabbit anti-PPARγ (1:1,000 dilution, Santa Cruz, sc-7196) overnight at 4°C and anti-cathepsin S polyclonal antibody (1:200 dilution, Abcam, ab18822) at room temperature for 16 hours.

Quantitative Real-Time Reverse-Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (QT-PCR) was performed using a Bio-Rad thermocycler and an SYBR green kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The mouse primers used for the reaction include: cathepsin S-forward, 5′-GCTGCGGGGGTGGCTTCAT-3′; cathepsin S-reverse, 5′-TCGGTACAGGAGGGGTCATCATAG-3′. cathepsin K-forward, 5′-CCACCTTCGCGTTCCTTCAGTAAT-3′; cathepsin K-reverse, 5′-ATAGCCGCCTCCACAGCCATAGT-3′. cathepsin L1-forward, 5′-AGCGACGGTGGGGCCTATTTCT-3′; cathepsin L1-reverse, 5′-TGTTCCGGTCTTTGGCTATTTTGA-3′. The relative mRNA levels were normalized by 18S RNA levels.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed as described previously (10). Briefly, mouse aortic smooth muscle cells were transfected with a human Flag-PPARγ plasmid or control vector pcDNA3.1. Next, cells were fixed and the ChIP assay was performed by using EZ-ChIP assay kit from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Purified chromatin was immunoprecipitated using an anti-Flag antibody (M1, Sigma) while normal mouse IgG served as a control. Eluted DNA fragments were purified to serve as templates for PCR amplification. The input fraction corresponded to 2% of the chromatin solution before immunoprecipitation. By using MatInspector software (www.genomatix.de) to analyze the cathepsin S promoter, we identified a potential PPAR binding site located between −141 to −159 bp upstream of the transcription start site. Primers used to amplify the area containing this PPAR binding site are: forward primer 5′-CAGAACCGATGTGAATAAAATGGA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGGCTGCTTGAAATGACTCTAAAAA-3′, resulting in a 275 bp fragment.

Cathepsin S Activity Assay

To assay cathepsin S activity, RASMCs were first passaged and grown to confluency as described above. The cells were lysed and the determination of cathepsin S activity is according to the suggested protocol (BioVision, Cat#-K144-100). In the fluorescence-based assay, cathepsin S cleaves the preferred substrate sequence Ac-VVR labeled with AFC (amino-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin). Released or free AFC cleaved by cathepsin S was measured using a fluorescence plate reader. For determining substrate specificity, negative control samples were incubated with a cathepsin S inhibitor provided by the manufacturer.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using a standard one-way ANOVA or chi-square test. Data from two-way ANOVA are expressed as mean ± SEM. P-values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

VSMC-selective PPARγ knockout mice have a larger external abdominal aortic diameter

To examine the role of VSMC PPARγ in AAA development, we experimentally induced aneurysms in the infrarenal aorta of VSMC-selective PPARγ knockout (SMPG KO) and wild- type mice through periaortic application of 0.25 M CaCl2. Similarly, an equimolar concentration of NaCl was applied periaortically and served as the control. The maximal external diameter of both SMPG KO and wild-type mice at the beginning of the study is 0.7 mm. From the several measurements conducted on each mouse aorta, only the largest external diameter measurement was used for statistical analysis on aortic dilatation. Figure 1A is a representation of photographed excised abdominal aortas six weeks after periaortic CaCl2 or NaCl application. There is a significant increase in the size of the maximal aortic diameter in SMPG KO compared to wild-type mice (1.4±0.3 mm for SMPG KO versus 1.1±0.2 mm for wild-type mice, P = .000119) (Figure 1A and 1B). Periaortic NaCl application did not result in external diameter increase in either SMPG KO or wild-type mice.

Figure 1.

VSMC-selective PPARγ knockout mice display greater severity of aortic elastin degradation

A semiquantitative grading scale based on severity of medial layer elastin fragmentation and degradation (Supplementary Figure I) was used to determine overall elastin disruption in periaortically-injured (CaCl2) SMPG KO and wild-type mice. The amount of elastin degradation in the aorta of each animal was determined from a score of 1 (mild) to 4 (severe). Figure 2 illustrates representative aortic sections stained with elastic Van Gieson for elastic fiber identification and/or destruction. Six weeks after periaortic CaCl2 application, medial elastin degradation occurs in the aortic walls of SMPG KO (Figure 2A, 2B) and wild-type mice (Figure 2C, 2D). There is greater deterioration of the elastic fiber network in SMPG KO mice (Figure 2A, 2B) compared to wild-type mice (Figure 2C, 2D). Subsequently, the elastic lamella is preserved from degradation following periarterial application of NaCl in both SMPG KO (Figure 2E, 2F) and wild-type mice (Figure 2G, 2H).

Figure 2.

A total of 42 and 48 serial sections from CaCl2-injured SMPG KO (n=7) and wild-type mice (n=8) respectively were histologically graded for elastin degradation (Figure 2 Insert Table). Histological analysis indicates that out of a total of 48 sections from wild-type mice, 6 sections have mild elastic disruption (grade I), 26 sections demonstrate moderate elastin destruction (grade II), 12 sections display high elastic breakdown (grade III), and 4 sections demonstrate severe elastin destruction (grade IV). Similarly, 42 total sections were histologically analyzed for elastin degradation in SMPG KO mouse aortas. However, medial layer elastic degradation is greater in SMPG KO mice since 24 sections display high elastin breakdown (grade III) and 15 sections demonstrate severe elastin destruction (grade IV). Furthermore, none of the sections from SMPG KO mice display mild elastin breakage (grade I) and only 3 sections show evidence of moderate elastic disruption (grade II). Thus, SMPG KO mice clearly demonstrate greater medial elastic breakdown compared with wild-type mice (P <.01) since 39 of 42 sections analyzed were administered at least a score of grade III. Thus, the results from Figure 2 suggest that disruption of the elastic lamella network is more severe in SMPG KO mice compared to wild-type mice, indicating a potential role for PPARγ in attenuating aortic aneurysmal development.

VSMC PPARγ decreases cathepsin S expression

To explore possible mechanisms by which deletion of PPARγ in VSMCs leads to an increase in the size of the aortic external diameter, we performed an in vitro study to examine PPARγ-mediated signaling mechanisms related to regulating the levels of cathepsin cysteine proteases. Cathepsins are shown to be capable of aortic elastin breakdown (26). In particular, cathepsins K, L, and S all have elastin-degrading properties and are significantly increased in human AAA tissue (27). The overexpression of PPARγ in RASMCs results in a decrease in the relative levels of cathepsin S mRNA expression (P = .022) (Figure 3), providing greater evidence that PPARγ provides a vascular protective effect against destruction of the medial layer elastic network. On the other hand, PPARγ overexpression has no effect on the relative mRNA levels of either cathepsin K or cathepsin L1 (Figure 3). The observations from this study demonstrate that of the three elastolytic cathepsins, the effects of PPARγ in smooth muscle cells are selective for the inhibition of cathepsin S mRNA expression.

Figure 3.

Cystatin C, an extracellular inhibitor of cathepsins, has been reported to be decreased in tissue of abdominal aortic aneurysms (28). We found that neither overexpression nor knockdown of VSMC PPARγ elicited a change in cystatin C mRNA levels (Supplemental Figure II).

Next, since PPARγ has been shown to inhibit MMP-9 expression (6) and MMP-9 is elevated in human AAA tissue (27, 29), we decided to examine the effects of PPARγ on MMP activity in cultured RASMCs and mouse aortic tissue. Gelatinase zymography revealed that neither PPARγ knockdown nor overexpression affected MMP-2 activity in cultured smooth muscle cells or homogenized aortic samples two weeks after CaCl2 treatment (Supplemental Figure III). Also, MMP-9 activity was not detectable in RASMCs or aortic tissue (Supplemental Figure III). Thus, our data suggests the critical contribution of PPARγ in attenuating CaCl2-induced aortic dilatation and elastin degradation is not related to the regulation of MMP-9 activity.

VSMC-selective PPARγ knockout mice have increased aortic cathepsin S protein expression

The results mentioned above compelled us to determine whether removal of VSMC PPARγ has an effect on the expression of abdominal aortic cathepsin S expression. Therefore, a Western blot analysis was performed using excised tissue from SMPG KO and wild-type mice. For this study, CaCl2 or NaCl was applied to the periaortic surface for one week before aortic excision took place (a total of n=3 for each pooled sample). Figure 4 shows that activated cathepsin S protein expression is increased in SMPG KO mice compared to wild-type mice one week after administering CaCl2. Therefore, our in vivo study demonstrates that VSMC PPARγ ablation removes inhibition of activated cathepsin S expression (Figure 4). Moreover, our observations are supported by previous in vivo studies showing rosiglitazone reduces cathepsin S mRNA levels in mouse aorta (30). Thus, it is apparent PPARγ signaling controls the level of cathepsin S expression in the vasculature.

Figure 4.

VSMC PPARγ decreases activated cathepsin S

Although we provide evidence of PPARγ participation in attenuating activated cathepsin S expression in the vasculature, our previous results did not show whether PPARγ decreases activated cathepsin S in VSMCs. Figure 5A and 5B demonstrate that PPARγ overexpression in RASMCs decreases active cathepsin S protein expression and activity (P = .013). Moreover, adenoviral-mediated PPARγ knockdown increases both protein expression and activity of cathepsin S (P = .018). One explanation for a decreased active form of cathepsin S is that PPARγ may affect post-translational modification of this proteolytic enzyme. However, more studies that are beyond the scope of this study must be performed to confirm this hypothesis.

Figure 5.

A PPAR Response Element is Located in the Promoter of Cathepsin S

To determine whether cathepsin S is a direct target gene of PPARγ, a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed in mouse aortic smooth muscle cells (Figure 6). The cathepsin S promoter was examined using bioinformatic analysis, and we identified a putative PPAR response element (PPRE) in the promoter region of cathepsin S. As shown in Figure 6, PPARγ binds to the response element located between −141 to −159 nucleotides upstream of the transcription start site (lane 6). Mouse aortic smooth muscle cells transfected with a negative control vector did not detect PPARγ binding in the cathepsin S promoter (lane 3). A non-reactive isotype-matched IgG negative control antibody served as a negative immunoprecipitation control in smooth muscle cells transfected with either Flag-PPARγ (lane 5) or a control vector (lane 2). Overall, the results from Figure 3 and 6 demonstrate that PPARγ inhibits cathepsin S expression at the genomic level through direct interaction with a PPRE in the cathepsin S promoter.

Figure 6.

VSMC-selective PPARγ knockout mice display evidence of elevated medial layer inflammation

Among the proposed theories regarding AAA pathogenesis, it has been suggested that the development of AAA is often characterized by the presence of an increased inflammatory infiltrate in the medial layer (31). Since PPARγ has been reported to inhibit macrophage activation (6) as well as production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines (32), we investigated the role of VSMC PPARγ and its functional significance in the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the medial layer. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrates an increased number of medial layer cells positive for F4/80 in SMPG KO mice compared to wild-type mice (P = .021) six weeks after CaCl2 treatment (Figure 7A, 7B). In addition, the percentage of the medial layer containing TNF-α was greater in SMPG KO mouse aortas versus the wild-type group (P = .015) (Figure 7C, 7D). These results suggest that VSMC PPARγ is important in attenuating CaCl2-induced increases in inflammatory cell recruitment and pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling in the medial layer.

Figure 7.

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to explore the beneficial effects of PPARγ against aortic elastin degradation and the development of AAA. The present investigation utilizes a smooth muscle cell-selective PPARγ knockout murine model as well as in vitro systems to elucidate a novel functional role of PPARγ in the vasculature. Our study demonstrates that loss of PPARγ in VSMCs results in increased aortic dilatation and elastic degradation following CaCl2-induced periaortic injury.

In support of our findings, two recent studies elegantly demonstrate that administration of PPARγ ligands decreases AAA development in animals, however the role of PPARγ was not discussed in these reports (18, 19). The fact that TZDs are clinically-approved (17) is advantageous for studying the potential therapeutic effects of PPARγ-mediated signaling cascades that may protect against AAA vascular complications. The encouraging results from our investigation have formed the basis for our laboratory to conduct a preclinical (animal) study on the potential effects of pioglitazone in a VSMC-selective PPARγ knock-out mouse model.

In the case of VSMC PPARγ influence on extracellular matrix structure and vessel stability, our findings clearly indicate a PPARγ-dependent effect on inhibiting cathepsin S activation in VSMCs. Cathepsin S is a potent elastase (33) and it is therefore logical to hypothesize that cathepsin S is important for the development of aortic aneurysms. First, human AAA tissue samples show evidence of elevated cathepsin S expression (27). Second, cathepsin S has been shown to be stable at neutral pH, and high elastolytic activity at neutral pH is a strong indicator of extracellular-degrading activity (34). Next, results from a previous study report improved elastic lamellae preservation in the aortic vessel wall of cathepsin S knockout mice (26). Finally, unpublished data from Shi et al. found that aortic dilatation is decreased in cathepsin S-deficient mice (35). Based on our results demonstrating that VSMC PPARγ directly targets cathepsin S, we can conclude the effect of PPARγ on aortic dilatation and elastin degradation occurs through transcriptional downregulation of cathepsin S. We also propose that PPARγ affects post-translational modification of cathepsin S, resulting in decreased activity of this elastolytic enzyme. Our findings showing that PPARγ directly inhibits both cathepsin S expression and activity are further strengthened by the observations that VSMC PPARγ has no effect on the mRNA expression levels of cystatin C, an extracellular cathepsin S inhibitor.

There is also the possibility that PPARγ may reduce aortic ectasia and medial layer degeneration through prevention of inflammatory cell recruitment. Increased inflammatory cell localization in the vessel wall is one event often regarded to be associated with aortic dilatation (36) and elastin disruption (37). Activated macrophages have long been considered as being major culprits of increased pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and signaling involved in extracellular matrix deterioration (37) and a role for PPARγ in the negative regulation of macrophage activation and monocyte cytokine production has been previously observed (6, 32). In the present study, our immunohistochemical analysis revealed significant increases in medial layer expression of F4/80 and TNF-α in VSMC PPARγ knockout mice six weeks after periaortic CaCl2 treatment. We provide evidence supporting the concept that PPARγ may also inhibit aortic distension and extracellular matrix destruction through inhibition of inflammatory cell localization and activity. This has important significance, particularly since TNF-α knockout mice are less prone to developing AAA (38).

It has been clearly documented that MMP-9 secreted from macrophages plays a critical role in AAA (39, 40). Furthermore, previously reported evidence from in vitro studies suggests a role for PPARγ in attenuating MMP-9 expression and activity in macrophages (6, 41). However, our studies did not detect MMP-9 activity in cultured VSMC after PPARγ knockdown or CaCl2-treated SMPG KO mouse aortic tissue. Interestingly, it has recently been reported that rosiglitazone, a high-affinity PPARγ agonist, does not reduce either MMP-2 or MMP-9 expression in angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms (18). Consistent with this report, another study demonstrates that MMP-9 levels in atherosclerotic plaques are similar in patients administered rosiglitazone versus placebo (42).

The majority of studies examining vessel wall elastin destruction have focused on MMP-mediated pathways over cathepsin signaling, in part because cathepsins were long considered to be localized in either lysosomes or endosomes, only participating in intracellular protein degradation (33). However, recent studies demonstrate that cathepsin S is secreted by cardiovascular cells and involved in the extracellular breakdown of elastin (26, 43). Results obtained in this study and other investigations should make us reevaluate the assumption that matrix metalloproteinases are the most important endogenous elastic proteolytic enzymes in AAA pathogenesis. Also, the notion that cathepsins and matrix metalloproteinases may be synergistically induced and even act in concert to promote deterioration of arterial wall elastin has been suggested (44).

There are potential limitations to our study that must be discussed. The concentration of 0.5 M sodium chloride (NaCl), an isotonic control to 0.25 M CaCl2, results in impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation of the rabbit aorta in response to acetylcholine (45). Therefore, in order to circumvent the potential development of decreased chronic aortic relaxation, we administered an equimolar concentration of NaCl as opposed to an isotonic control. Another limitation in our study is that in situ detection of MMP-2 and MMP-9 was not performed since this method has been associated with non-specific MMP activity. Furthermore, since MMP-9 is an inducible protein, it is possible that methods of isolation may result in loss of MMP-9 activity. In addition, adenoviral transfection could result in phenotypic modulation of SMCs and also affect MMP-9 activity. Therefore, we cannot exclude a critical role of VSMC MMP-9 in aortic distension.

Although the values for quantification of elastin fragmentation are higher in the aorta of VSMC-selective PPARγ knockout mice, PPARγ-mediated signaling is only one of several signaling cascades involved in elastic fiber degeneration. Thus, we must acknowledge that PPARγ-independent pathways also participate in the attenuation of AAA. Next, we must consider that although rosiglitazone reduces the severity of aortic expansion experimentally, recent focus has centered on this PPARγ ligand and its association with cardiovascular events (46, 47). Nevertheless, our results suggest potential benefits of PPARγ activation in attenuating the development of AAA.

Conclusions

This is the first investigation to demonstrate in vivo that PPARγ reduces aortic dilatation and extracellular matrix destruction. Thus, the data in this study provide the basis for further elucidation of novel PPARγ signaling mechanisms involved in the prevention of AAA pathogenesis. The data suggest that VSMC PPARγ counterbalances or offsets the deleterious effects of extracellular matrix-degrading signaling mechanisms that promote the formation of AAAs in animals and humans. Finally, it is likely that PPARγ signaling, particularly in the cardiovascular system, can serve as the basis for developing effective clinical therapeutic intervention against this common vascular disorder.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grants

This work was partially funded by National Institutes of Health (HL68878 and HL89544). M.H. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Institutes of Health (T32 HL007853). L.C. is supported by the American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (09SDG2230270). J.Z. was supported by the American Heart Association National Career Development Grant (0835237N). Y.E.C. is an established investigator of the American Heart Association (0840025N).

Footnotes

Disclosures

No competing interest declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics (NHCS) NVSS. WISQARS Query, 20 Leading Causes of Death, United States 1999–2006, All Races, Male and Female Sexes. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ernst CB. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1167–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304223281607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powell J, Greenhalgh RM. Cellular, enzymatic, and genetic factors in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1989;9:297–304. doi: 10.1067/mva.1989.vs0090297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marx N, Bourcier T, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Plutzky J. PPARgamma activation in human endothelial cells increases plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 expression: PPARgamma as a potential mediator in vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:546–51. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.3.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marx N, Schonbeck U, Lazar MA, Libby P, Plutzky J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activators inhibit gene expression and migration in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1998;83:1097–103. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.11.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricote M, Li AC, Willson TM, Kelly CJ, Glass CK. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature. 1998;391:79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamblin M, Chang L, Fan Y, Zhang J, Chen YE. PPARs and the Cardiovascular System. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1415–52. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim S, Jin CJ, Kim M, Chung SS, Park HS, Lee IK, et al. PPARgamma gene transfer sustains apoptosis, inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, and reduces neointima formation after balloon injury in rats. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:808–13. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000204634.26163.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meredith D, Panchatcharam M, Miriyala S, Tsai YS, Morris AJ, Maeda N, et al. Dominant-negative loss of PPARgamma function enhances smooth muscle cell proliferation, migration, and vascular remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:465–71. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.184234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang L, Villacorta L, Zhang J, Garcia-Barrio MT, Yang K, Hamblin M, et al. Vascular smooth muscle cell-selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma deletion leads to hypotension. Circulation. 2009;119:2161–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.815803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halabi CM, Beyer AM, de Lange WJ, Keen HL, Baumbach GL, Faraci FM, et al. Interference with PPAR gamma function in smooth muscle causes vascular dysfunction and hypertension. Cell Metab. 2008;7:215–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansmann G, de Jesus Perez VA, Alastalo TP, Alvira CM, Guignabert C, Bekker JM, et al. An antiproliferative BMP-2/PPARgamma/apoE axis in human and murine SMCs and its role in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1846–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI32503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang N, Yang G, Jia Z, Zhang H, Aoyagi T, Soodvilai S, et al. Vascular PPARgamma controls circadian variation in blood pressure and heart rate through Bmal1. Cell Metab. 2008;8:482–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schupp M, Janke J, Clasen R, Unger T, Kintscher U. Angiotensin type 1 receptor blockers induce peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activity. Circulation. 2004;109:2054–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127955.36250.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooke BS, Habashi JP, Judge DP, Patel N, Loeys B, Dietz HC., 3rd Angiotensin II blockade and aortic-root dilation in Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2787–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Wilkison WO, Willson TM, Kliewer SA. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12953–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villacorta L, Schopfer FJ, Zhang J, Freeman BA, Chen YE. PPARgamma and its ligands: therapeutic implications in cardiovascular disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2009;116:205–18. doi: 10.1042/CS20080195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones A, Deb R, Torsney E, Howe F, Dunkley M, Gnaneswaran Y, et al. Rosiglitazone reduces the development and rupture of experimental aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 2009;119:3125–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.852467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golledge J, Cullen B, Rush C, Moran CS, Secomb E, Wood F, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands reduce aortic dilatation in a mouse model of aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longo GM, Xiong W, Greiner TC, Zhao Y, Fiotti N, Baxter BT. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 work in concert to produce aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:625–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI15334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshimura K, Aoki H, Ikeda Y, Fujii K, Akiyama N, Furutani A, et al. Regression of abdominal aortic aneurysm by inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Nat Med. 2005;11:1330–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun J, Sukhova GK, Yang M, Wolters PJ, MacFarlane LA, Libby P, et al. Mast cells modulate the pathogenesis of elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3359–68. doi: 10.1172/JCI31311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu M, Zhang J, Tseng YH, Cui T, Zhu X, Xiao Y, et al. Rad GTPase attenuates vascular lesion formation by inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circulation. 2005;111:1071–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156439.55349.AD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villacorta L, Zhang J, Garcia-Barrio MT, Chen XL, Freeman BA, Chen YE, et al. Nitro-linoleic acid inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Am J Physiol. 2007;293:H770–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00261.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Fu M, Zhu X, Xiao Y, Mou Y, Zheng H, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta is up-regulated during vascular lesion formation and promotes post-confluent cell proliferation in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11505–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sukhova GK, Zhang Y, Pan JH, Wada Y, Yamamoto T, Naito M, et al. Deficiency of cathepsin S reduces atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:897–906. doi: 10.1172/JCI14915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdul-Hussien H, Soekhoe RG, Weber E, von der Thusen JH, Kleemann R, Mulder A, et al. Collagen degradation in the abdominal aneurysm: a conspiracy of matrix metalloproteinase and cysteine collagenases. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:809–17. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi GP, Sukhova GK, Grubb A, Ducharme A, Rhode LH, Lee RT, et al. Cystatin C deficiency in human atherosclerosis and aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1191–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI7709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wassef M, Baxter BT, Chisholm RL, Dalman RL, Fillinger MF, Heinecke J, et al. Pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a multidisciplinary research program supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:730–8. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.116966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keen HL, Ryan MJ, Beyer A, Mathur S, Scheetz TE, Gackle BD, et al. Gene expression profiling of potential PPARgamma target genes in mouse aorta. Physiol Genomics. 2004;18:33–42. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00027.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koch AE, Haines GK, Rizzo RJ, Radosevich JA, Pope RM, Robinson PG, et al. Human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Immunophenotypic analysis suggesting an immune-mediated response. Am J Pathol. 1990;137:1199–213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature. 1998;391:82–6. doi: 10.1038/34184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chapman HA, Riese RJ, Shi GP. Emerging roles for cysteine proteases in human biology. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:63–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bromme D, Bonneau PR, Lachance P, Wiederanders B, Kirschke H, Peters C, et al. Functional expression of human cathepsin S in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Purification and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4832–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sukhova GK, Shi GP. Do cathepsins play a role in abdominal aortic aneurysm pathogenesis? Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1085:161–9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1383.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anidjar S, Dobrin PB, Eichorst M, Graham GP, Chejfec G. Correlation of inflammatory infiltrate with the enlargement of experimental aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1992;16:139–47. doi: 10.1067/mva.1992.35585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimizu K, Mitchell RN, Libby P. Inflammation and cellular immune responses in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:987–94. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000214999.12921.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiong W, MacTaggart J, Knispel R, Worth J, Persidsky Y, Baxter BT. Blocking TNF-alpha attenuates aneurysm formation in a murine model. J Immunol. 2009;183:2741–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson RW, Holmes DR, Mertens RA, Liao S, Botney MD, Mecham RP, et al. Production and localization of 92-kilodalton gelatinase in abdominal aortic aneurysms. An elastolytic metalloproteinase expressed by aneurysm-infiltrating macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:318–26. doi: 10.1172/JCI118037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McMillan WD, Patterson BK, Keen RR, Shively VP, Cipollone M, Pearce WH. In situ localization and quantification of mRNA for 92-kD type IV collagenase and its inhibitor in aneurysmal, occlusive, and normal aorta. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1139–44. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.8.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marx N, Sukhova G, Murphy C, Libby P, Plutzky J. Macrophages in human atheroma contain PPARgamma: differentiation-dependent peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor gamma(PPARgamma) expression and reduction of MMP-9 activity through PPARgamma activation in mononuclear phagocytes in vitro. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65540-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meisner F, Walcher D, Gizard F, Kapfer X, Huber R, Noak A, et al. Effect of rosiglitazone treatment on plaque inflammation and collagen content in nondiabetic patients: data from a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:845–50. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000203511.66681.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Nooijer R, Bot I, von der Thusen JH, Leeuwenburgh MA, Overkleeft HS, Kraaijeveld AO, et al. Leukocyte cathepsin S is a potent regulator of both cell and matrix turnover in advanced atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:188–94. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yasuda Y, Li Z, Greenbaum D, Bogyo M, Weber E, Bromme D. Cathepsin V, a novel and potent elastolytic activity expressed in activated macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36761–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403986200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freestone T, Turner RJ, Higman DJ, Lever MJ, Powell JT. Influence of hypercholesterolemia and adventitial inflammation on the development of aortic aneurysm in rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:10–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Home PD, Pocock SJ, Beck-Nielsen H, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Jones NP, et al. Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiovascular outcomes--an interim analysis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:28–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2457–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.