Abstract

Vitamin D deficiency is associated with many adverse health outcomes. There are several well established environmental predictors of vitamin D concentrations, yet studies of the genetic determinants of vitamin D concentrations are in their infancy. Our objective was to conduct a pilot genome-wide association (GWA) study of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25[OH]2D) concentrations in a subset of 229 Hispanic subjects, followed by replication genotyping of 50 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the entire sample of 1,190 Hispanics from San Antonio, Texas and San Luis Valley, Colorado. Of the 309,200 SNPs that met all quality control criteria, three SNPs in high linkage disequilibrium (LD) with each other were significantly associated with 1,25[OH]2D (rs6680429, rs9970802, and rs10889028) at a Bonferroni corrected P-value threshold of 1.62 × 10−7, however none met the threshold for 25[OH]D. Of the 50 SNPs selected for replication genotyping, five for 25[OH]D (rs2806508, rs10141935, rs4778359, rs1507023, and rs9937918) and eight for 1,25[OH]2D (rs6680429, rs1348864, rs4559029, rs12667374, rs7781309, rs10505337, rs2486443, and rs2154175) were replicated in the entire sample of Hispanics (P < 0.01). In conclusion, we identified several SNPs that were associated with vitamin D metabolite concentrations in Hispanics. These candidate polymorphisms merit further investigation in independent populations and other ethnicities.

Keywords: Vitamin D; 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; genome-wide association study; Hispanic

1. Introduction

Vitamin D deficiency is associated with many adverse health outcomes, including bone diseases, cancers, autoimmune diseases, infectious diseases, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, making vitamin D an important health outcome of interest. The primary source of vitamin D is exposure to sunlight, which produces provitamin D3, the initial vitamin D metabolite, in the skin. Secondary sources of vitamin D are dietary intake of vitamin D rich foods (e.g., fatty fish and fortified foods, such as milk and cereal) and vitamin D supplements.

In addition to behavioral and environmental predictors of vitamin D concentrations, genes are likely to play an important role. Heritability estimates of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D), the major circulating metabolite and marker of vitamin D status, range from 0.23 in Hispanics from the San Luis Valley in Colorado to 0.41 in Hispanics from San Antonio, Texas [1]. Further, the heritability estimates of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25[OH]2D), the more biologically active metabolite, range from 0.16 in Hispanics from the San Luis Valley to 0.20 in Hispanics from San Antonio [1]. Despite this evidence of genetic contributions to both 25[OH]D and 1,25[OH]2D concentrations, studies of the genetic determinants of vitamin D concentrations are in their infancy [1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7] and no genome-wide association (GWA) studies of the more active vitamin D metabolite, 1,25[OH]2D, have been reported thus far. Moreover, all three of the published GWA studies were in non-Hispanic white populations; no GWA studies have been reported in Hispanic populations.

In this report we present results of a two-stage GWA study of both 25[OH]D and 1,25[OH]2D in Hispanic Americans from the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study Family Study (IRASFS). Through a high-density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) scan and follow-up genotyping, a series of genes and regions that contribute to variation in the concentration of two vitamin D metabolites may have been identified.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study population

Details of the IRASFS design and recruitment [8] and the vitamin D phenotyping [1] have been previously published. Briefly, the IRASFS is a multi-center study designed to identify the genetic determinants of insulin resistance and adiposity in Hispanic and African Americans. Members of large families of self-reported Hispanic ancestry (N = 1,190 individuals in 92 pedigrees from San Antonio, Texas and San Luis Valley, Colorado) were recruited and used in this report. The Institutional Review Board of each participating clinical and analysis site approved the study protocol and all participants provided their written informed consent.

A subset of IRASFS Hispanics (229 individuals from 34 families) was chosen from the San Antonio study group for the pilot GWA study (stage 1). These samples were from participants without type 2 diabetes who had complete data for glucose homeostasis and obesity phenotypes, with an age, body mass index (BMI) and gender distribution similar to that of the overall IRASFS population [9]. The individuals chosen represented a genetically homogeneous population based upon structure [10] analysis using microsatellite polymorphisms from an earlier genome-wide linkage scan [11; 12] (i.e., chosen individuals had structure analysis scores >0.90 [from a possible range of 0.0–1.0] on the Hispanic axis, meaning they had >90% Hispanic ancestry).

2.2. Measurement of vitamin D concentrations

Concentrations of 25[OH]D were measured by a 2-step process involving rapid extraction of 25[OH]D and other hydroxylated metabolites from a fasting plasma sample and radioimmunoassay with a 25[OH]D-specific antibody (DiaSorin, Stillwater, Minnesota) with interassay CVs <8%. Concentrations of 1,25[OH]2D were measured by a 2-step process involving extraction and purification of vitamin D metabolites from a fasting plasma sample and radioimmunoassay with a 1,25[OH]2D-specific antibody (DiaSorin) with interassay CVs <19%.

2.3. Genome-wide genotyping

DNA was obtained from Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines. Genotyping was performed at Cedars–Sinai Medical Center using 1.5 μg of genomic DNA (15 μl of 100 ng/μl stock) and Illumina Infinium II HumanHap 300 BeadChips and assay protocol [13]. Genotypes were called based on clustering of the raw intensity data for the two dyes using Illumina Bead Studio software. Consistency of genotyping was checked using 18 repeat samples. Repeat genotyping of DNA samples was performed once if the overall call rate was less than 98%. The sample was rejected if there was no improvement in call rate. Each SNP was examined for Mendelian inconsistencies using PedCheck [14]. Genotypes inconsistent with Mendelian inheritance were converted to missing. Maximum likelihood estimates of allele frequencies were computed using the largest set of unrelated individuals and genotypes were tested for departures from Hardy-Weinberg proportions using a chi-square goodness-of-fit test. SNPs with Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium (p<0.001), minor allele frequency (MAF) less than 0.05, or more than 5% missing genotypes were excluded from subsequent analysis. Genotypes with GenCall (Illumina) scores less than 0.15 were set to missing (0.24%).

2.4. Selection of SNPs for replication genotyping

We used two SNP selection strategies to prioritize SNPs for replication genotyping in the entire IRASFS Hispanic cohort (stage 2; includes 229 subjects from the stage 1 GWA analysis). First, 38 SNPs were selected for replication because they were the top independent (r2 <0.40) SNPs from the stage 1 GWA analysis (17 SNPs for 25[OH]D and 21 SNPs for 1,25[OH]2D). Second, 12 additional SNPs were chosen as positional candidates from a previously conducted genome-wide linkage scan of the IRASFS Hispanic cohort. The linkage scan consisted of 383 polymorphisms at approximately 9 cM intervals and was performed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Mammalian Genotyping Service (MGS, Marshfield, Wisconsin). The methods of the linkage scan are described in detail elsewhere [15]. We identified linkage regions with a LOD score >2.0 for the two vitamin D metabolites. Although there were no linkage peaks with LOD scores >2.0 for 25[OH]D, there were two regions that met this criterion for 1,25[OH]2D (chromosome 8 between D8S592 and D6S502 [chromosomal location of 118,525,000–138,900,000 using NCBI’s Reference assembly] and chromosome 11 between D11S1984 and D11S2362 [chromosomal location of 1,523,000–4,869,000]). We then searched for SNPs that were located in one of these two linkage regions, were within the top 3,000 additive P-values in the stage 1 GWA analysis, and were functional SNPs (i.e., had a risk score of ≥3 from a bioinformatics analysis using FASTSNP [function analysis and selection tool for single nucleotide polymorphisms] [16]). Twelve independent (r2 <0.40) SNPs met these criteria and were selected for replication genotyping in the entire IRASFS Hispanic cohort (stage 2). Ultimately, 50 SNPs were chosen for replication genotyping in the entire IRASFS Hispanic cohort, 38 based solely on GWA results and 12 based on GWA results informed by linkage analysis.

2.5. Replication genotyping in the entire IRASFS Hispanic cohort (stage 2)

Replication genotyping of the 50 SNPs described above was performed at Wake Forest University using the MassARRAY genotyping system (Sequenom, San Diego, California) (13). Primer sequences are available on request. Quality control was similar to that described for the genome-wide genotyping.

2.6. Measurement of covariates

Data on solar UV-B radiation, which is the primary source of vitamin D, was obtained from the National Solar Radiation Database 1991–2005 Update produced by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory under the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (available at http://rredc.nrel.gov/solar/old_data/nsrdb/). The AVerage daily total GLObal solar radiation (AVGLO), defined as the total amount of direct and diffuse solar radiation in Watt-hours per square meter (Wh/m2) received on a horizontal surface, for the month prior to the blood draw was determined for each individual based on the county of the study center. BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2).

2.7. Statistical analysis

A panel of 149 ancestry informative markers (AIMs) was genotyped in the entire IRASFS Hispanic cohort. These AIMs were selected from the literature for Hispanic populations [17; 18]. The CEPH (N = 90) and Yoruba (N = 90) HapMap data were merged with the study sample and a principal component (PC) analysis was computed to estimate ancestry proportions. The first three PCs from this analysis explained 10.3% (PC1), 4.8% (PC2), and 1.9% (PC3) of the variation across the 149 AIMs. PC2 was the best at distinguishing the parent populations of Hispanic Americans in the IRASFS and therefore was used to adjust for admixture in these analyses.

For both stage 1 and stage 2, SOLAR (Sequential Oligogenic Linkage Analysis Routines) software [19] was used to test for association between individual SNPs and the concentration of each of the two vitamin D metabolites. The variance component method implemented in SOLAR enabled us to account for the correlations among family members in pedigrees of arbitrary size and complexity. The dependent variables, 25[OH]D and 1,25[OH]2D, were square root transformed in order to best approximate the distributional assumptions of the test and minimize heterogeneity of the variance. The analysis for association with 25[OH]D was adjusted for age, gender, BMI, average solar radiation (AVGLO) in the month prior to the blood draw, and the PC for admixture. The analysis for association with 1,25[OH]2D was adjusted for age, gender, 25[OH]D concentration, and the PC for admixture. An additive genetic model was assumed for all analyses unless the number of individuals homozygous for the minor allele was less than 15 in which case a dominant model with respect to the minor allele was used. The significance of each SNP was assessed using a one degree of freedom likelihood ratio test.

3. Results

As described above, we carried out a two-stage genetic association study of two vitamin D metabolites, with stage 1 being a GWA study in a subset of 229 Hispanic IRASFS participants and stage 2 being replication genotyping and analysis of 50 SNPs from the GWA analysis in all 1,190 Hispanics from the IRASFS (includes 229 subjects from the stage 1 GWA analysis). Comparisons between the GWA sample (used in stage 1) and the entire IRASFS Hispanic cohort (used in stage 2) with respect to the vitamin D metabolite concentrations and well established predictors of these concentrations show that the GWA sample was representative of the entire Hispanic cohort (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Hispanic subjects in the IRASFS

| Stage 1: GWA Sample (N = 229) | Stage 2: Entire Cohort (N = 1,190a) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male gender (n, %) | 83 (36.2) | 493 (41.4) |

| Age (years) | 41.3 ± 13.9 (40.3) | 42.8 ± 14.5 (41.3) |

| Solar radiation (Wh/m2) | 4405 ± 1440 (4212) | 4647 ± 1678 (4423) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.4 ± 5.9 (28.5) | 29.0 ± 6.2 (28.1) |

| 25[OH]D (nmol/Lb) | 37.4 ± 15.5 (36.2) | 40.9 ± 18.2 (39.9) |

| 1,25[OH]2D (pmol/Lb) | 130.8 ± 41.9 (124.8) | 119.1 ± 40.3 (114.4) |

Data are means ± SD (median) unless otherwise noted. Wh/m2, Watt-hours per square meter

Includes 229 subjects from the stage 1 GWA analysis.

To convert 25[OH]D to conventional units (ng/mL), divide by 2.496; to convert 1,25[OH]2D to conventional units (pg/mL), divide by 2.6.

3.1. Stage 1: GWA study

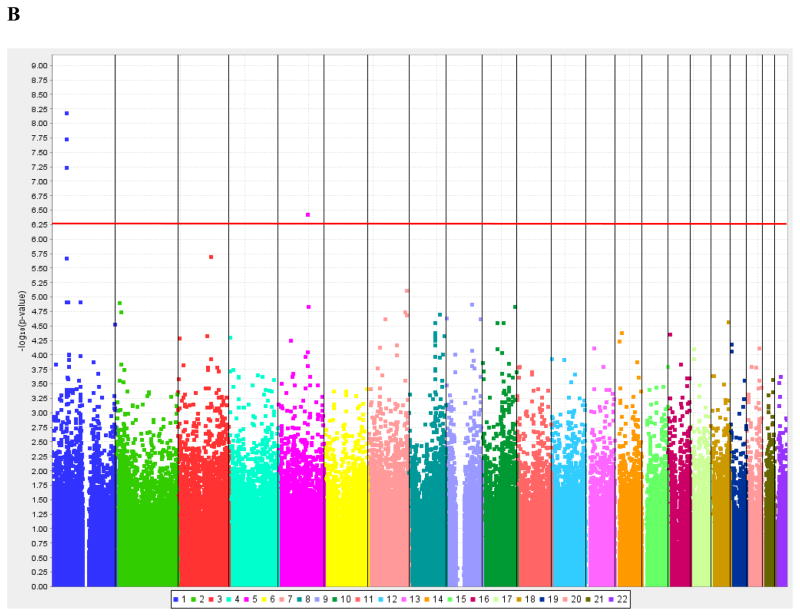

The average sample call rate was 99.76%. A total of 309,200 SNPs met all quality control criteria and were evaluated for association with 25[OH]D and 1,25[OH]2D. Manhattan plots of the distribution of GWA P-values (on the −log10 scale) after adjustment for covariates and admixture are shown in Figure 1, ordered by chromosomal location. Since a total of 309,200 SNPs were tested, the genome-wide significance threshold based on a conservative Bonferroni correction is P <1.62 × 10−7 (shown by the horizontal red line in Figure 1). None of the SNPs met this strict threshold for association with 25[OH]D, while three SNPs in high linkage disequilibrium (LD) with each other (r2 >0.75) met the threshold for 1,25[OH]2D (rs6680429, rs9970802, and rs10889028). Quantile-Quantile plots of the observed P values (on the log10 scale) plotted against P values expected under the null distribution (Figure 2) demonstrate an excessive number of significant results for 1,25[OH]2D.

Figure 1. Manhattan plots of the distribution of P-values for the association between each SNP and the concentration of vitamin D metabolites in the stage 1 GWA analysis.

P-values are ordered by chromosome. The horizontal red line indicates the Bonferroni corrected threshold for significance (P <1.62 × 10−7).

(A) The analysis for 25[OH]D was adjusted for age, gender, average solar radiation (AVGLO) in the month prior to blood draw, and the principal component (PC) for admixture.

(B) The analysis for 1,25[OH]2D was adjusted for age, gender, 25[OH]D, and the PC for admixture.

Figure 2. Quantile-Quantile plot of observed versus expected for the stage 1 GWA analysis.

The Quantile-Quantile plot represents a function of the expectation under the null distribution versus the observed distribution.

(A) The analysis for 25[OH]D was adjusted for age, gender, average solar radiation (AVGLO) in the month prior to blood draw, and the PC for admixture.

(B) The analysis for 1,25[OH]2D was adjusted for age, gender, 25[OH]D, and the PC for admixture.

3.2. Stage 2: Replication in the entire IRASFS Hispanic cohort

SNPs that were selected for replication genotyping and were statistically significant in the entire Hispanic cohort of the IRASFS (stage 2; Bonferroni corrected P-value of <0.01 because 50 SNPs were tested for association) are displayed in Table 2 for both 25[OH]D and 1,25[OH]2D. Of the 50 independent (r2 <0.40) SNPs tested in stage 2, five were significantly associated with 25[OH]D in the entire Hispanic cohort and eight were significantly associated with 1,25[OH]2D. None of the SNPs selected for replication because they were under a linkage peak for 1,25[OH]2D were significant in the entire Hispanic cohort (data not shown).

Table 2.

SNPs significantly associated with concentrations of the vitamin D metabolites in both the stage 1 GWA sample (P < 1.0 × 10−4) and the entire cohort (stage 2; P < 1.0 × 10−2) of the IRASFS

| Chr | SNP | Gene (SNP function, if any) | Alleles | MAF | Stage 1: GWA Sample P-value (N=229) | Stage 2: Entire Cohort P-value (N=1190a) | Genotypic Means in Entire Cohort ± SD (genotypic median) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/1 | 1/2 | 2/2 | |||||||

| 25[OH]Db | |||||||||

| 13 | rs2806508 | N/A | C/T* | 0.426 | 1.6 × 10−6 | 4.1 × 10−5 | 15.0 ± 6.5 (14) N = 274 | 16.4 ± 7.3 (16) N = 508 | 18.6 ± 8.0 (18) N = 213 |

| 14 | rs10141935 | N/A | A/G* | 0.471 | 3.1 × 10−5 | 3.9 × 10−4 | 16.1 ± 7.6 (15) N = 457 | 16.5 ± 7.0 (16) N = 440 | 18.2 ± 7.7 (17) N = 107 |

| 15 | rs4778359 | N/A | G*/T | 0.147 | 4.0 × 10−6 | 5.5 × 10−5 | 15.6 ± 6.9 (15) N = 640 | 18.0 ± 7.8 (18) N = 310 | 19.1 ± 7.7 (19) N = 41 |

| 16 | rs1507023 | A2BP1 (intronic enhancer) | C*/T | 0.470 | 7.5 × 10−6 | 5.1 × 10−4 | 17.0 ± 7.1 (17) N = 340 | 16.3 ± 7.6 (15) N = 472 | 15.8 ± 7.1 (15) N = 173 |

| 16 | rs9937918 | GPR114 (splicing regulation) | C/T* | 0.382 | 3.3 × 10−5 | 8.2 × 10−3 | 17.0 ± 7.2 (17) N = 236 | 16.8 ± 7.2 (16) N = 521 | 15.4 ± 7.5 (14) N = 226 |

| 1,25[OH]2Dc | |||||||||

| 1 | rs6680429 | DAB1 | A*/G | 0.368 | 6.6 × 10−9 | 1.4 × 10−3 | 44.9 ± 15.3 (42) N = 380 | 45.8 ± 14.4 (44) N = 444 | 50.0 ± 18.3 (48) N = 151 |

| 2 | rs1348864 | N/A | G/T* | 0.279 | 1.8 × 10−5 | 2.4 × 10−3 | 45.0 ± 14.7 (43) N = 373 | 45.8 ± 15.3 (44) N = 447 | 48.5 ± 17.9 (44) N = 161 |

| 5 | rs4559029 | N/A | A/G* | 0.379 | 1.5 × 10−5 | 1.2 × 10−4 | 48.8 ± 16.0 (46) N = 344 | 45.2 ± 15.0 (42) N = 483 | 42.2 ± 15.3 (42) N = 156 |

| 7 | rs12667374 | N/A | A*/G | 0.059 | 2.4 × 10−5 | 1.8 × 10−3 | 45.5 ± 15.2 (44) N = 945 | 55.4 ± 19.8 (51) N = 45 | 55.3 ± 30.6 (73) N = 3 |

| 7 | rs7781309 | MLL3 | C*/T | 0.235 | 7.9 × 10−6 | 3.1 × 10−3 | 45.2 ± 15.0 (43) N = 604 | 46.6 ± 16.1 (45) N = 332 | 53.8 ± 17.9 (52) N = 40 |

| 8 | rs10505337 | N/A | C*/T | 0.382 | 2.0 × 10−5 | 2.7 × 10−3 | 44.7 ± 14.7 (43) N = 403 | 46.3 ± 16.2 (44) N = 458 | 48.5 ± 15.3 (45) N = 132 |

| 9 | rs2486443 | N/A | A*/G | 0.029 | 2.4 × 10−5 | 3.5 × 10−4 | 45.7 ± 15.3 (44) N = 923 | 50.6 ± 18.2 (47) N = 70 | N/A |

| 10 | rs2154175 | N/A | G/T* | 0.279 | 1.5 × 10−5 | 9.9 × 10−4 | 44.0 ± 14.0 (42) N = 562 | 48.0 ± 16.3 (46) N = 373 | 52.7 ± 22.0 (47) N = 56 |

N/A is indicated for Gene if the SNP is intragenic.

Minor allele (coded as 2 for the analysis). MAF, minor allele frequency.

Includes 229 subjects from the stage 1 GWA analysis.

Adjusted for age, gender, average solar radiation (AVGLO) in the month prior to blood draw, and the principal component (PC) for admixture.

Adjusted for age, gender, 25[OH]D, and the PC for admixture.

4. Discussion

We conducted an initial GWA study of both 25[OH]D and 1,25[OH]2D in a subset of 229 Hispanics from San Antonio, Texas and performed replication genotyping and analysis of 50 SNPs in the entire sample of 1,190 Hispanics. Of the 50 SNPs selected for replication genotyping, five for 25[OH]D (rs2806508, rs10141935, rs4778359, rs1507023, and rs9937918) and eight for 1,25[OH]2D (rs6680429, rs1348864, rs4559029, rs12667374, rs7781309, rs10505337, rs2486443, and rs2154175) were replicated in the entire sample of Hispanics (P <0.01; Table 2). Although three GWA studies of 25[OH]D have been reported, no GWA studies of the more active vitamin D metabolite, 1,25[OH]2D, have been reported thus far [4; 5; 7]. Moreover, GWA publications thus far have been centered on populations of European descent [20]; this GWA study in Hispanic Americans helps fill a void in the existing GWA literature.

The five SNPs that were associated with 25[OH]D were independent from the eight SNPs that were associated with 1,25[OH]2D. One would expect a SNP to be associated with both metabolites if the SNP is involved in a process that is common to both metabolites, for example, the transport of the vitamin D metabolites, as was seen with a SNP in the vitamin D binding protein gene in a previous publication by this group [1]. However, if a SNP is involved in a process that is specific to one of the metabolites, for example, the hydroxylation of a particular metabolite to another metabolite, the SNP may only be associated with the metabolites involved in that hydroxylation step. For example, a SNP that enhances the expression of CYP24A1, which produces 24-hydroxylase that degrades excess 1,25[OH]2D to 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, would not necessarily be strongly associated with the concentration of the upstream metabolite, 25[OH]D.

In the stage 1 GWA analysis in 229 Hispanics from San Antonio, no SNPs met the Bonferroni corrected P-value cut-off (P <1.62 × 10−7) for 25[OH]D (Figure 1A); however, three SNPs (rs6680429, rs9970802, and rs10889028) in high LD were significantly associated with 1,25[OH]2D (P <1.62 × 10−7; Figure 1B). All three SNPs are intronic and reside on the short arm of chromosome 1 (1p32-p31; NCBI Mapviewer) within the disabled homolog 1 (DAB1) gene. DAB1 is a very large gene, spanning more than 1.2 Mb, which encodes a protein that is thought to be a signal transducer that interacts with protein kinase pathways to regulate neuronal positioning in the developing brain (GeneID: 1600; NCBI Entrez Gene). Of note, two other intronic SNPs in DAB1 ranked in the top 25 associations based on the additive P-values (rs155288 and rs1831870). Since these SNPs were in LD, only the SNP with the lowest P-value (rs6680429; P = 6.6 × 10−9), was genotyped in the entire IRASFS Hispanic cohort, where the association was replicated (P = 1.4 × 10−3). However, this region was not among the three regions that reached genome-wide significance in the two recent GWA studies [5; 7].

Twelve SNPs were selected for replication because they were under a linkage peak for 1,25[OH]2D, were in the top 3,000 SNPs in the stage 1 GWA analysis, and were functional SNPs. However, none of these SNPs were significant (P <0.01) in the entire Hispanic cohort. There are at least two potential explanations for this lack of replication. First, the linkage peaks could have been due to chance and, therefore, false positives. Second, one or both of the linkage peaks may have been true positives, but we did not select a SNP for replication genotyping that was in strong enough LD with the causative variant to show an association with 1,25[OH]2D. If this was the case, it may be that the twelve SNPs that were under a linkage peak and in the top 3,000 SNPs in the stage 1 GWA analysis (with additive P-values ranging from 9.9 × 10−5 to 7.6 × 10−3) were false positives and the HumanHap 300 BeadChip that we used did not contain a SNP that was in strong LD with the causative variant.

Of the three regions identified by both of the two recent large GWA studies of 25[OH]D, GC, DHCR7/NADSYN1, and CYP2R1, only one of the regions showed marginal significance in our stage 1 GWA analysis: rs7041 in the GC gene (P <0.10) [5; 7]. Two SNPs in the DHCR7/NADSYN1 gene and two in the CYP2R1 gene were included in the HumanHap 300 BeadChip used for our stage 1 GWA analysis, but none of these showed even a marginally significant association with 25[OH]D. This lack of association could be explained by the small sample size of our stage 1 GWA sample (N = 229). Alternately, the lack of association could be explained by differences in LD and/or allele frequencies between the non-Hispanic white populations included in the two recent GWA studies and the Hispanic population included in the current GWA study.

To carry out this study we chose a research design in which a pilot GWA study was performed on 229 Hispanic subjects from one clinical center (San Antonio). From the analysis results, 50 SNPs were selected for genotyping and analysis in the entire IRASFS Hispanic cohort. While we ideally would have carried out the GWA study on the entire cohort, this was not financially possible. Our purpose was to identify some potential polymorphisms, and was motivated by the success of a number of small GWA studies. For example, the complement factor H gene association with age-related macular degeneration (224 cases and 134 controls) [21], the NOS1AP gene association with cardiac repolarization (200 subjects) [22], the TNFSF15 gene conferring susceptibility to Crohn’s disease (94 subjects) [23], and the recent report of a region near the CDKN2A and CDKN2B genes on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease, which was based initially on results from a GWA study of 322 cases and 312 controls [24].

A limitation to this study is that, due to financial constraints, we were only able to select 50 SNPs for replication genotyping, but it is likely that additional SNPs contribute to the variation in vitamin D metabolite concentrations. For example, a SNP in the GC gene, rs7041, has been previously shown to be associated with 25[OH]D in the entire San Antonio Hispanic cohort of 504 individuals (P = 0.003), as well as in Hispanics from the San Luis Valley and African Americans from Los Angeles, and in the two recent large GWA studies [1; 5; 7]. However, in the stage 1 GWA analysis in a subset of 229 Hispanics from the San Antonio cohort, rs7041, which was included in the HumanHap 300 BeadChip, was only marginally associated with 25[OH]D (P <0.10), although the association with the T risk allele was in the same direction and of similar magnitude. Following up an expanded list of SNPs will be the focus of future research.

5. Conclusions

Since vitamin D status is being linked to more and more health outcomes, understanding the genetic variants that are responsible for variation in the concentration of relevant vitamin D metabolites is important. Our analysis identified several SNPs that were associated with vitamin D metabolite concentrations in Hispanics. These candidate polymorphisms merit further investigation in independent populations. If replicated, the biologic pathways behind the associations should be investigated, as they may also play a role in adverse health outcomes associated with vitamin D, such as bone disease, cancer, autoimmune disease, infectious disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by American Diabetes Association (ADA) Grant 7-04-RA-83; NIH Grants HL060894 (Bowden), HL060919 (Haffner), HL060944 (Wagenknecht), and HL061019 (Norris); the Wake Forest University Health Sciences Center for Public Health Genomics; the General Clinical Research Centers Program, National Center for Research Resources Grant M01RR00069; and the Human Genetics Core of the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center Grant DK63491.

Abbreviations

- 25[OH]D

25-hydroxyvitamin D

- 1,25[OH]2D

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D

- AIMs

ancestry informative markers

- AVGLO

AVerage daily total GLObal solar radiation

- GWA

genome-wide association

- IRASFS

Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study Family Study

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- MAF

minor allele frequency

- PC

principal component

- SNPs

single nucleotide polymorphisms

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Engelman CD, Fingerlin TE, Langefeld CD, Hicks PJ, Rich SS, Wagenknecht LE, Bowden DW, Norris JM. Genetic and environmental determinants of 25-hydroxyvitamin d and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d levels in Hispanic and african americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3381–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wjst M, Altmuller J, Braig C, Bahnweg M, Andre E. A genome-wide linkage scan for 25-OH-D(3) and 1,25-(OH)2-D3 serum levels in asthma families. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:799–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinotte M, Diorio C, Berube S, Pollak M, Brisson J. Genetic polymorphisms of the vitamin D binding protein and plasma concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in premenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:634–40. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin EJ, Dupuis J, Larson MG, Lunetta KL, Booth SL, Govindaraju DR, Kathiresan S, Keaney JF, Jr, Keyes MJ, Lin JP, Meigs JB, Robins SJ, Rong J, Schnabel R, Vita JA, Wang TJ, Wilson PW, Wolf PA, Vasan RS. Genome-wide association with select biomarker traits in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahn J, Yu K, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Simon KC, McCullough ML, Gallicchio L, Jacobs EJ, Ascherio A, Helzlsouer K, Jacobs KB, Li Q, Weinstein SJ, Purdue M, Virtamo J, Horst R, Wheeler W, Chanock S, Hunter DJ, Hayes RB, Kraft P, Albanes D. Genome-wide association study of circulating vitamin D levels. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2739–45. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGrath JJ, Saha S, Burne TH, Eyles DW. A systematic review of the association between common single nucleotide polymorphisms and 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang TJ, Zhang F, Richards JB, Kestenbaum B, van Meurs JB, Berry D, Kiel DP, Streeten EA, Ohlsson C, Koller DL, Peltonen L, Cooper JD, O’Reilly PF, Houston DK, Glazer NL, Vandenput L, Peacock M, Shi J, Rivadeneira F, McCarthy MI, Anneli P, de Boer IH, Mangino M, Kato B, Smyth DJ, Booth SL, Jacques PF, Burke GL, Goodarzi M, Cheung CL, Wolf M, Rice K, Goltzman D, Hidiroglou N, Ladouceur M, Wareham NJ, Hocking LJ, Hart D, Arden NK, Cooper C, Malik S, Fraser WD, Hartikainen AL, Zhai G, Macdonald HM, Forouhi NG, Loos RJ, Reid DM, Hakim A, Dennison E, Liu Y, Power C, Stevens HE, Jaana L, Vasan RS, Soranzo N, Bojunga J, Psaty BM, Lorentzon M, Foroud T, Harris TB, Hofman A, Jansson JO, Cauley JA, Uitterlinden AG, Gibson Q, Jarvelin MR, Karasik D, Siscovick DS, Econs MJ, Kritchevsky SB, Florez JC, Todd JA, Dupuis J, Hypponen E, Spector TD. Common genetic determinants of vitamin D insufficiency: a genome-wide association study. Lancet. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60588-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henkin L, Bergman RN, Bowden DW, Ellsworth DL, Haffner SM, Langefeld CD, Mitchell BD, Norris JM, Rewers M, Saad MF, Stamm E, Wagenknecht LE, Rich SS. Genetic epidemiology of insulin resistance and visceral adiposity. The IRAS Family Study design and methods. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:211–7. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(02)00412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rich SS, Goodarzi MO, Palmer ND, Langefeld CD, Ziegler J, Haffner SM, Bryer-Ash M, Norris JM, Taylor KD, Haritunians T, Rotter JI, Chen YD, Wagenknecht LE, Bowden DW, Bergman RN. A genome-wide association scan for acute insulin response to glucose in Hispanic-Americans: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study (IRAS FS) Diabetologia. 2009;52:1326–33. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1373-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–59. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rich SS, Bowden DW, Haffner SM, Norris JM, Saad MF, Mitchell BD, Rotter JI, Langefeld CD, Wagenknecht LE, Bergman RN. Identification of quantitative trait loci for glucose homeostasis: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) Family Study. Diabetes. 2004;53:1866–75. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rich SS, Bowden DW, Haffner SM, Norris JM, Saad MF, Mitchell BD, Rotter JI, Langefeld CD, Hedrick CC, Wagenknecht LE, Bergman RN. A genome scan for fasting insulin and fasting glucose identifies a quantitative trait locus on chromosome 17p: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study (IRAS) family study. Diabetes. 2005;54:290–5. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunderson KL, Steemers FJ, Ren H, Ng P, Zhou L, Tsan C, Chang W, Bullis D, Musmacker J, King C, Lebruska LL, Barker D, Oliphant A, Kuhn KM, Shen R. Whole-genome genotyping. Methods Enzymol. 2006;410:359–76. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)10017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connell JR, Weeks DE. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:259–66. doi: 10.1086/301904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norris JM, Langefeld CD, Scherzinger AL, Rich SS, Bookman E, Beck SR, Saad MF, Haffner SM, Bergman RN, Bowden DW, Wagenknecht LE. Quantitative trait loci for abdominal fat and BMI in Hispanic-Americans and African-Americans: the IRAS Family study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:67–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan HY, Chiou JJ, Tseng WH, Liu CH, Liu CK, Lin YJ, Wang HH, Yao A, Chen YT, Hsu CN. FASTSNP: an always up-to-date and extendable service for SNP function analysis and prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W635–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choudhry S, Coyle NE, Tang H, Salari K, Lind D, Clark SL, Tsai HJ, Naqvi M, Phong A, Ung N, Matallana H, Avila PC, Casal J, Torres A, Nazario S, Castro R, Battle NC, Perez-Stable EJ, Kwok PY, Sheppard D, Shriver MD, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Risch N, Ziv E, Burchard EG. Population stratification confounds genetic association studies among Latinos. Hum Genet. 2006;118:652–64. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seldin MF, Tian C, Shigeta R, Scherbarth HR, Silva G, Belmont JW, Kittles R, Gamron S, Allevi A, Palatnik SA, Alvarellos A, Paira S, Caprarulo C, Guilleron C, Catoggio LJ, Prigione C, Berbotto GA, Garcia MA, Perandones CE, Pons-Estel BA, Alarcon-Riquelme ME. Argentine population genetic structure: large variance in Amerindian contribution. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007;132:455–62. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1198–211. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg NA, Huang L, Jewett EM, Szpiech ZA, Jankovic I, Boehnke M. Genome-wide association studies in diverse populations. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:356–66. doi: 10.1038/nrg2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards AO, Ritter R, 3rd, Abel KJ, Manning A, Panhuysen C, Farrer LA. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:421–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1110189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arking DE, Pfeufer A, Post W, Kao WH, Newton-Cheh C, Ikeda M, West K, Kashuk C, Akyol M, Perz S, Jalilzadeh S, Illig T, Gieger C, Guo CY, Larson MG, Wichmann HE, Marban E, O’Donnell CJ, Hirschhorn JN, Kaab S, Spooner PM, Meitinger T, Chakravarti A. A common genetic variant in the NOS1 regulator NOS1AP modulates cardiac repolarization. Nat Genet. 2006;38:644–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamazaki K, McGovern D, Ragoussis J, Paolucci M, Butler H, Jewell D, Cardon L, Takazoe M, Tanaka T, Ichimori T, Saito S, Sekine A, Iida A, Takahashi A, Tsunoda T, Lathrop M, Nakamura Y. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in TNFSF15 confer susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3499–506. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, Stewart A, Roberts R, Cox DR, Hinds DA, Pennacchio LA, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Folsom AR, Boerwinkle E, Hobbs HH, Cohen JC. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science. 2007;316:1488–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1142447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]