Abstract

In Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus Auratus), the expression of reproductive behavior requires the perception and discrimination of sexual odors. The behavioral response to these odors is mediated by a network of ventral forebrain nuclei, including the medial preoptic area (MPOA). The role of MPOA in male copulatory behavior has been well-studied, but less is known about the role of MPOA in appetitive aspects of male reproductive behavior. Furthermore, many previous studies that examined the role of MPOA in reproductive behavior have used large lesions that damaged other nuclei near MPOA or fibers of passage within MPOA, making it difficult to attribute post-lesion deficits in reproductive behavior to MPOA specifically. Thus, the current study used discrete, excitotoxic lesions of MPOA to test the role of this nucleus in opposite-sex odor preference and copulatory behavior in both sexually-naïve and sexually-experienced males. Lesions of MPOA eliminated preference for volatile, opposite-sex odors in sexually-naïve, but not sexually-experienced, males. When, however, males were allowed to contact the sexual odors, preference for female odors remained intact. Surprisingly, lesions of MPOA caused severe copulatory deficits only in sexually-naïve males, suggesting previous reports of copulatory deficits following MPOA lesions in sexually-experienced males were not due to damage to MPOA itself. Together, these results demonstrate that the role of MPOA in appetitive and consummatory aspects of reproductive behavior depends on the type of access to sexual odors and the sexual experience of the male.

Keywords: Olfaction, Reproduction, Pheromone, Odor Preference

In many rodent species, including Syrian hamsters, male reproductive behavior depends critically on the perception of odor cues from the environment (Johnston 1990). Volatile odor cues are processed primarily by the main olfactory system (MOS), whereas non-volatile odor cues are processed primarily by the accessory olfactory system (AOS) (Breer 2003). Together, these two systems have been shown to mediate both appetitive and consummatory aspects of reproductive behavior in Syrian hamsters, including males’ attraction to female vaginal secretion (Powers et al. 1979) and copulatory behavior (Murphy and Schneider 1970; Powers and Winans 1975).

The behavioral response to social odors in mediated by a network of ventral forebrain nuclei including the medial amygdala (MA), posterior bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (pBNST), and medial preoptic area (MPOA) (Wood 1997). Specifically, MA and pBNST are both densely connected to MPOA (Wood and Swann 2005) and several lines of evidence suggest that main and accessory olfactory information processed in MA and pBNST must reach MPOA in order to elicit the appropriate behavioral response (Lehman et al. 1983; Sayag et al. 1994; Kondo and Arai 1995). Indeed, lesions of MPOA eliminate copulation in male Syrian hamsters (Powers et al. 1987; Floody 1989) and reduce or eliminate copulatory behavior in nearly every species studied, (Bean et al. 1981; Balthazart and Surlemont 1990; Kingston and Crews 1994; Liu et al. 1997), whereas stimulation of MPOA can enhance copulation (Malsbury 1971; Paredes et al. 1990; Rodriguez-Manzo et al. 2000).

The role of MPOA in appetitive aspects of reproductive behavior, such as the approach and investigation of social odors, is less well understood. Electrolytic lesions of MPOA do not impair male Syrian hamsters’ investigation of female hamster vaginal secretion when presented alone or during copulation (Powers et al. 1987). When, however, subjects are given the choice between two simultaneously presented odors, lesions of MPOA produce differing results. For example, electrolytic lesions including MPOA eliminate male rats’ preference to investigate bedding from estrous females over anestrous female bedding (Hurtazo and Paredes 2005). Similarly, lidocaine injections targeting MPOA reduce the amount of time male rats spend near an estrous female that they cannot contact, although they continue to investigate the female more than a simultaneously presented male (Hurtazo et al. 2008). In contrast, lesions including MPOA reverse male ferrets’ preference to approach an estrous female over a male (Paredes and Baum 1995) and this reversal of preference is strengthened when the stimulus animals cannot be contacted (Kindon et al. 1996). Together, these studies suggest that volatile odor cues may be the critical stimulus for MPOA-mediated attraction to, and preference for, opposite-sex conspecifics, but the role of MPOA in opposite-sex odor preference has never been directly tested.

Therefore, the following experiments used site-specific, excitotoxic lesions to test the role of MPOA in generating the appropriate behavioral response to volatile and non-volatile social odors. We hypothesized that MPOA is required for male hamsters’ attraction to volatile female odor cues, but is not critical for attraction to non-volatile opposite-sex odors. If so, then lesions of MPOA should eliminate males’ preference for opposite-sex odors when they cannot contact the odor stimuli, but preference should remain intact when contact is allowed. Furthermore, as small lesions of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of MPOA have produced different behavioral results depending on the sexual experience of the subjects (Arendash and Gorski 1983; De Jonge et al. 1989), we tested the effects of MPOA lesions in both sexually-naïve and sexually-experienced males.

2. EXPERIMENAL PROCEDURES

The goal of the following experiments was to test the role of MPOA in sexual odor investigation in male hamsters. Exposure to female odors causes an increase in circulating testosterone levels in male hamsters (Macrides et al. 1974; Pfeiffer and Johnston 1992) and it is possible that lesions of MPOA may interfere with this surge. Thus, in order to equalize steroid hormone levels across experimental groups, all subjects were gonadectomized and maintained on physiological levels of exogenous testosterone for the duration of the experiment. Following bilateral, excitotoxic lesions of MPOA or sham lesion surgeries, sexually-naïve and sexually-experienced subjects underwent a series of behavioral tests: first, subjects were tested for their preference to investigate female odors over male odors (Odor Preference). To determine if any effects of MPOA lesions on odor investigation depend on the volatility of the odor cues being processed, Odor Preference tests were conducted under conditions that either prevented contact with the odor sources (Non-contact; volatile odors only) or allowed contact with the odor sources (Contact; volatile and non-volatile odors). Second, in order to determine if a lack of preference in these tests was due to an inability to discriminate between odor stimuli subjects were tested for their ability to discriminate between social odor sources using a habituation-dishabituation task (Odor Discrimination). Lastly, as a positive control, subjects’ sexual behavior in response to a receptive stimulus female (Copulatory Behavior Test) was assessed.

2.1 Animals

Experimental subjects were adult (3 to 6 months old) male Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). A separate group of unrelated adult male and female hamsters served as odor stimulus donors for behavior tests. A third group of ovariectomized and hormone-primed adult female hamsters were used as stimulus females for copulatory behavior tests. Experimental subjects and copulatory stimulus females were single-housed, whereas odor donors were group-housed (three to four animals per cage), in solid-bottom Plexiglas cages (36 cm × 30 cm × 16 cm). All subjects were maintained on a reversed 14 hour light/10 hour dark photoperiod, and food and water were available ad libitum. All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications NO. 80–23; revised 1996) and approved by the Georgia State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

2.2 Sexual Experience

Following gonadectomy (see 2.3.1), experimental subjects were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions: sexually-experienced (EXP; n = 30) or sexually-naïve (NVE; n = 32). EXP males were given weekly sexual experiences for three consecutive weeks. Subjects were placed into a clear, Plexiglas testing area (50 cm × 25 cm × 30 cm) for five minutes prior to the addition of a receptive stimulus female. An angled mirror was placed below the testing arena to provide a view of the ventral surface of the animals. Encounters lasted for 30 minutes, or until the animals engaged in aggressive behavior, at which point the stimulus female was removed. The second and third encounters were video-recorded and the male’s behavior was later scored using the Observer for Windows, version 9.0 (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands). Males who failed to copulate on at least two of the three encounters (n = 4) were eliminated from the study. To control for possible effects of experimenter handling on future behavior, NVE males were transported to the same behavioral testing room and placed into an empty cage for 30 minutes once a week for three consecutive weeks.

2.3 Surgery

All surgeries were performed under 2% isoflurane gas anesthesia vaporized in 100% oxygen (gonadectomy) or a 70:30% oxygen/nitrous oxide mixture (stereotaxic surgery). To minimize post-operative pain, ketoprofen (5 mg/kg subcutaneously, Henry Schein, Melville, NY, USA) was administered intra-operatively.

2.3.1 Gonadectomy and Hormone Implant

One to two weeks prior to lesion surgery, subjects’ testes were bilaterally removed via a bilateral midline abdominal incision and cauterization of the ductus deferens and blood vessels. Silastic capsules (i.d. 1.57 mm, o.d. 2.41 mm, Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) packed with 20 mm length of crystalline testosterone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) were implanted subcutaneously between the scapulae immediately following gonadectomy. Vicryl suture (size 4–0, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) and wound clips were used to close the smooth muscle and skin incisions, respectively.

Stimulus females for copulatory experiences and behavior testing were ovariectomized at least two weeks prior to use. Following bilateral flank incisions, the ovaries were removed via cauterization of the uterine horn and blood vessels. Silastic capsules (i.d. 1.57 mm, o.d. 2.41 mm, Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) packed with 5 mm length of crystalline estradiol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) were implanted subcutaneously between the scapulae immediately following gonadectomy. Vicryl suture and wound clips were used to close the smooth muscle and skin incisions, respectively. To induce behavioral receptivity, stimulus females were injected subcutaneously with 0.15 ml of progesterone dissolved in sesame oil (2.5 mg/ml, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) 4 hours prior to copulatory behavior tests.

2.3.2 Excitotoxic Lesion

NVE and EXP subjects were randomly assigned to either a MPOA lesion (MPOA-X; NVE n = 22, EXP n = 20) or a sham lesion surgery (SHAM; NVE n = 8, EXP n = 10) group. Anesthetized subjects were secured in the stereotaxic apparatus such that their skull was level in the anterior-posterior (A-P) and medial-lateral (M-L) planes. Following a midline scalp incision, the skin and temporal muscles were retracted to expose the skull and a hand-operated drill was used expose dura. All A-P and M-L measurements were taken in mm relative to bregma and all dorsal-ventral (D-V) measurements were taken in mm relative to dura. Excitotoxic lesions were made by lowering a microinjection syringe (701R 10 μl syringe, Hamilton, Reno, NV, USA) under stereotaxic control (Microinjection Unit, Model 5002, David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA) into bilateral sites targeting MPOA (A-P: −2.0, M-L: ± 0.7, D-V: −7.0) and injecting N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA, 20 mg/ml; 20 nl per injection, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). To minimize the flow of excitotoxin up the syringe tract, the syringe was left in place for 10 minutes after each injection.

Sham surgeries were identical to lesion surgeries with two exceptions: 1) the microinjection syringe was lowered to 1 mm above the target injection site and 2) no excitotoxin was infused into the target injection sites. After all surgeries, skull holes were sealed using bone wax and incisions were closed with wound clips. Subjects were allowed to recover for at least two weeks prior to behavioral testing.

2.4 Behavioral Testing

All behavior testing took place during the first six hours of the dark phase and under light illumination.

2.4.1 Odor Stimuli

Sexual odor stimuli used for Odor Preference and Odor Discrimination tests were collected from cages of group-housed, same-sexed odor donors that had not been changed for four days prior to odor collection. Each sexual odor stimulus consisted of soiled cotton bedding (2 Nestlets, 12 g, ANCARE, Bellmore, NY), soiled corncob litter (50 ml, Bed-o-cob, The Andersons, Maumee, OH, USA) and one damp cotton gauze pad that was used to wipe the inner walls of the cage. In addition, a damp gauze pad was used to wipe two of the cage resident’s anogenital region and bilateral flank glands 10 times each. For female odor stimuli, vaginal secretion was also collected onto a gauze pad by gently palpating the vaginal area of a female with a disposable probe, and was added to each odor stimulus. Clean odor stimuli consisted of clean cotton bedding (2 Nestlets), clean corncob litter (50 ml), and clean cotton gauze pads (2).

For Contact tests, additional sexual odors were collected directly onto glass microscope slides (25 mm × 75 mm × 1 mm) by rubbing a clean slide along an odor donor’s flank and anogenital regions. All odor slides contained samples from two individual odor donors (collected separately onto each end of the slide). For female odor slides, a sample of vaginal secretion was also collected onto the same slide. All odor stimuli were stored in airtight containers at 4°C until 20 minutes before use. Odor stimuli older than one month were discarded and no subject was tested with the same odor stimulus more than once.

2.4.2 Odor Preference

A three-choice test was used to measure odor preference. Subjects were placed into a glass aquarium (50 cm × 25 cm × 30 cm) with opaque walls. Three acrylic odor presentation boxes (8 cm × 8 cm × 8 cm) were lined up on the floor of the aquarium such that the left and right sides of the center box touched one side of each of the lateral boxes. The backs of the three boxes were then affixed to one of the short walls of the aquarium; thus, only the front and top surfaces of each box were accessible. Each odor presentation box had 7-mm holes drilled along the front surface that allowed volatile odors to pass, but prevented contact with the odor sources. During testing, a single odor stimulus (see above) was placed into each of the three odor presentation boxes. Additionally, a line bisecting the available floor space was drawn parallel to the short walls so that general activity levels (as measured by total number of line crosses) could be assessed during the test. The top of the aquarium was secured with a clear Plexiglas top to allow for overhead video recording of the subject’s behavior. All surfaces of the aquarium and odor boxes were thoroughly cleaned with 70% alcohol and allowed to dry between subjects.

Subjects were tested in a series of three tests in the 3-choice apparatus, each separated by 24 hours: Clean, Non-Contact preference, and Contact preference. At the beginning of each test, a subject was placed into the testing arena and then allowed ten minutes to freely explore the apparatus. For all tests, investigation of the odor stimulus was coded when the subject made contact with, or directed its nose within 1 cm of, the perforated front surface of the odor box and/or odor slide. For Clean tests, clean odor stimuli were placed into each of the three odor boxes. These tests were used to acclimate the subjects to the testing arena, as well as to obtain baseline levels of activity in the absence of sexual odor stimuli. For subsequent preference tests, female and male odor stimuli were placed into each of the two outer odor boxes, and clean odor stimuli were placed into the center odor box. The side on which each sexual odor was placed (left or right) was alternated between consecutive subjects. Non-Contact and Contact tests were identical except that during Contact tests, a single odor slide matching the type of odor stimulus in that container (female, male, clean) was secured to the center of the front surface of each odor presentation box.

Video recordings of all tests were digitized onto a computer and scored using the Observer for Windows, version 9.0. All observers were blind to the condition of the subject, and different observers reached at least a 90% inter-observer reliability score prior to coding behavior.

2.4.3 Odor Discrimination

In order to determine if deficits observed in Non-Contact Odor Preference tests (see section 3.3) could be due to an inability to discriminate between odor stimuli, all males were tested for their ability to discriminate between volatile odors using a habituation-dishabituation test. The habituation-dishabituation test involves repeated presentations of the same odor source followed by a test presentation of a novel odor source. A decrease in investigation during the repeated presentations indicates a perception of the odors as being the same or familiar. An increase in investigation of the novel odor compared to the last presentation of the habituated odor indicates an ability to discriminate between the two odors (Johnston 1993; Baum and Keverne 2002). The testing sequence consisted of four, 3-minute presentations of repeated odors (habituation) followed by a fifth, 3-minute presentation of a novel odor (dishabituation). Five-minute inter-trial intervals separated each odor presentation. Odor stimuli were presented in the same odor presentation boxes used for the Odor Preference tests. Odor presentation boxes were affixed to one of the short walls of subjects’ home cage and investigation was measured using a stopwatch. Odor containers were cleaned with 70% alcohol and allowed to dry between subjects. Subjects were presented with different odor sources on each of the habituation trials so that subjects were habituated to the sexual identity of the repeated odor, rather than to the individual identity of odor donors. Under these testing parameters, male hamsters consistently display a lack of habituation to repeated presentations of female odors (Maras and Petrulis 2006) and so all subjects were tested using male odors as the habituation stimuli and female odors as the dishabituation stimuli for social odor discrimination tests.

2.4.4 Copulatory Behavior

Copulatory behavior test procedures were identical to those used to provide sexual experience to EXP males (see section 2.2). Tests were video-recorded and later scored using Observer for Windows, version 9.0. The total number and latencies (from onset of test) of several behavioral measures were scored: mounts (M), intromissions (I), ejaculations (E), and long intromissions (LI). LI are distinguished from I in that males do not quickly dismount the female following vaginal penetration, but instead display a repetitive thrusting pattern (Bunnell et al. 1977). Importantly, the expression of LI is associated with the onset of sexual satiety in Syrian hamsters (Bunnell et al. 1977; Parfitt and Newman 1998). In addition, the total durations of time the male spent investigating the female’s anogenital region (AGI), investigating the female’s head or body region (HBI), and self-grooming (SG) were also scored. Finally, several derived measures of copulatory behavior were also analyzed: post-ejaculatory interval (PEI; latency to display a mount or intromission after each ejaculation), the number of intromissions to reach each ejaculation (I-E), and mounting efficiency (ME; the total number of intromissions divided by the total number of mounts + intromissions).

2.5 Histology and Lesion Verification

Following the last behavioral test, subjects were injected with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg; Sleep Away, Ft. Dodge, IA, USA) and transcardially perfused with 200 ml of 0.1M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) followed by 200 ml of paraformaldehyde (4%). Brains were post-fixed in paraformaldehyde (4%) overnight and then cryoprotected for 48 hours in 30% sucrose in PBS solution. Coronal sections (30-μm) of brain tissue were sectioned using a cryostat (−20°C) and stored in cryoprotectant until immunohistochemical localization of Neuronal Nuclei protein (NeuN, see below). Additionally, in order to further delineate lesion damage from fiber tracts (which are not readily detected by NeuN), every third section was mounted onto glass slides using a 1% gelatin mounting solution and stained for Nissl material with cresyl violet. Nissl- and NeuN-stained sections were examined under a light microscope for the location and extent of lesion damage as compared with published hamster neuroanatomical plates (Morin and Wood 2001), and the minimum and maximum extents of lesion damage were traced onto anatomical plates using Adobe Illustrator CS 11.0 software.

2.6 Immunohistochemistry

Free-floating sections were removed from cryoprotectant, rinsed thoroughly in PBS, and then incubated in a monoclonal antibody against NeuN in PBS with 0.4% Triton-X-100 (1:30,000, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) for 48 hours at 4°C. After rinsing in PBS, sections were incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody (1:600, Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) in PBS with 0.4% Triton-X-100 for one hour at room temperature, rinsed in PBS, then incubated in an avidin-biotin complex (1:200, Vectastain Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for one hour at room temperature. Sections were then rinsed in PBS and reacted in a nickel-enhanced 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) solution (2 mg DAB plus 250 mg Nickel (II) Sulfate with 8.3 μl 3% H2O2 per 10ml of 175 mM sodium acetate) to yield a blue-black reaction product. After 15 minutes, sections were rinsed in PBS to stop the chromagen reaction.

2.7 Blood Collection and Radioimmunoassay

Blood samples were collected from the inferior vena cava after anesthesia and immediately prior to perfusion and stored in vacutainer collection tubes (4-ml draw, red/gray, VWR, West Chester, PA, USA) on ice until centrifugation. Samples were centrifuged at 2500 revolutions per minute at 4°C for 20 minutes and serum was stored in 200-μl aliquots at −20°C until assay. Testosterone levels (ng/ml) were measured by radioimmunoassay kits from Diagnostics System Laboratories (DSL 4000 Testosterone) with a sensitivity range of 0.05 to 22.92 ng/ml and an interassay variance of 8%, previously validated for hamster serum (Cooper et al. 2000). The mean testosterone levels (± standard errors) for experimental subjects were: NVE MPOA-X = 3.525 ± 0.403; NVE SHAM = 4.241 ± 0.527; EXP MPOA-X = 3.240 ± 0.573; EXP SHAM = 3.471 ± 0.541. There was no difference in testosterone levels between lesion groups for NVE or EXP males (NVE t(18) = 1.009, P = 0.327; EXP t(16) = 0.286, P = 0.778).

2.8 Role of Endocrine Status on Copulatory Behavior

In order to equalize steroid hormone levels across experimental groups, all subjects were gonadectomized and maintained on physiological levels of exogenous testosterone for the duration of the experiment. However, in order to confirm that lesions of MPOA do not produce differing results in gonadally-intact versus hormone-replaced subjects, the copulatory behavior of a small group (n = 6) of gonadally-intact males with lesions of MPOA were compared to the copulatory behavior of a subset (n = 7) of hormone-replaced experimental subjects. The mean number of mounts (t(11) = 1.076, P = 0.315) intromissions (t(11) = 2.761, P = 0.476), and ejaculations (t(11) = 1.091, P = 0.344) did not differ between gonadally-intact and hormone-replaced subjects with lesions of MPOA.

2.9 Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows and significance was determined as P < .05. To establish investigatory preferences for each type of 3-choice test (Clean, Non-Contact Preference, Contact Preference), 2 (Experimental group: MPOA-X, SHAM) X 3 (Odor) mixed-design ANOVAs were performed. Significant interactions were explored using simple effects analysis and pair-wise comparisons with Bonferroni alpha adjustments. Furthermore, separate one-way ANOVAs were used to compare the levels of investigation of each stimulus directly across experimental groups. To identify differences in general motor activity, additional one-way ANOVAs were used to compare the total number of midline crosses across experimental groups for the Clean test.

For the habituation-dishabituation data, data were split by experimental group, and paired t-tests (2-tailed, with Bonferroni alpha adjustments) were used to detect both (1) a habituation to the repeated presentations of odors (male 1 vs. male 4) and (2) a dishabituation to the presentation of the test odor (male 4 vs. female).

Many copulatory behavior tests were terminated before 30 minutes because the male and female engaged in aggressive behavior. Thus, only the first 20 minutes of each copulatory test were analyzed to eliminate variability caused by differences in test duration. Group differences in most copulatory measures were detected using one-way ANOVAs, whereas group differences in the proportion of animals displaying copulatory measures were detected using z-tests for independent proportions. Additionally, separate 2 × 2 (lesion group × ejaculatory series) ANOVAS were used to detect changes in post-ejaculatory intervals or the number of intromissions to reach each ejaculation in the copulatory tests.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Lesion Reconstruction

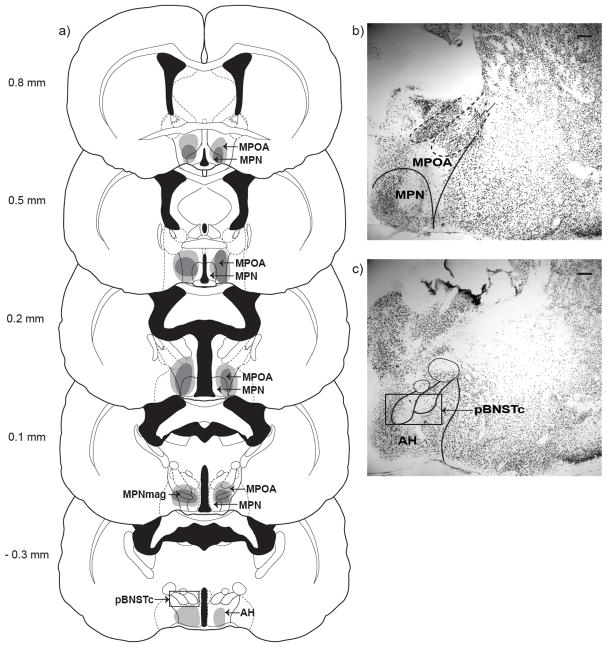

Subjects were included in the MPOA-X lesion group (NVE n = 11; EXP n = 10) only if they had extensive bilateral damage to MPOA, defined as at least 60% bilateral damage to MPOA in at least two stereotaxic planes of section (Figure 1a, (Morin and Wood 2001). All subjects included in the MPOA-X group sustained significant damage to MPOA, including the medial preoptic nucleus (MPN), below the most caudal extent of the anterior commissure (Bregma 0.5 mm). Most subjects (NVE n = 9; EXP n = 8) also sustained significant damage to MPOA, including MPN, at the level where the lateral and third ventricles fuse (Figure 1b; Bregma 0.2 mm). Some subjects (NVE n = 5; EXP n = 4) had damage to the most caudal level of MPOA, including MPN and the magnocellular medial preoptic nucleus (MPNmag) (Bregma −0.1 mm). Subjects with MPNmag damage did not differ from subjects without MPNmag damage on any behavioral measure and were therefore collapsed into the MPOA-X lesion group. Fewer subjects (NVE n = 2; EXP n = 3) sustained damage to the more rostral aspects of MPOA, including MPN (Bregma 0.8 mm).

Figure 1. Lesion Reconstruction.

a) Coronal sections through rostral to caudal extent of MPOA showing largest (light gray) and smallest (dark gray) lesions included in MPOA-X group. Immunohistochemical localization of neuronal nuclei (NeuN) protein was used to visualize cell loss in males with b) excitotoxic lesions of MPOA; some males also sustained damage to c) the most caudal portions of the posterior bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (pBNSTc) and were excluded from the MPOA-X lesion group. Measurements in mm relative to bregma, scale bars = 200 μm

Some subjects included in the MPOA-X group sustained minimal or unilateral damage to other adjacent nuclei, defined as less than 20% damage at only one stereotaxic plane of section of the nucleus (Morin and Wood 2001). These included the parastriatal nucleus (n = 3), lateral preoptic area (n = 11), and periventricular hypothalamic nucleus (n = 10). Eight males also sustained damage to the most rostral level of the anterior hypothalamus (Bregma −0.3 mm). There was no difference in behavior across subjects with minor unilateral, minor bilateral, or no damage to any of the adjacent nuclei. Only needle tracts were visible in SHAM males (NVE n = 8; EXP n = 7).

Subjects were excluded from the MPOA-X lesion group if their lesions extended significantly outside of MPOA. Specifically, four subjects (NVE n =1; EXP n = 3) were excluded from the lesion group because they sustained significant damage to the most caudal levels of the posterior bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (pBNSTc; Figure 1c, Bregma −0.3). In addition, subjects were excluded from the MPOA-X lesion group if their lesions failed to damage a significant portion of MPOA. Specifically, four NVE subjects sustained partial (less than 60% damage in two stereotaxic planes of section), bilateral damage to MPOA and three NVE subjects had primarily unilateral damage to MPOA. Although the small sample sizes of these groups precluded them from statistical analysis, data from subjects with lesions that extended significantly outside of MPOA or that failed to significantly damage MPOA were examined to determine the specificity of MPOA lesions on odor preference and copulatory behaviors (see below).

3.2 Odor Preference

3.2.1 Clean Test

In the Clean test, both NVE and EXP subjects investigated the center odor presentation box less than the left (NVE t(18) = 5.203, P < .001; EXP t(16) = 7.287, P < .001) or right (NVE t(18) = 6.493, P < .001; EXP t(16) = 5.529, P < .001) odor presentation boxes; there was no difference in time spent investigating the left and right boxes (NVE t(18) = .227, P = .823; EXP t(16) = 1.067, P = .302). Thus, although there was a general bias to investigate the outside boxes, there was no difference in this bias across experimental groups, and more importantly, there was no preference to investigate either one of the boxes used to present social odors. There was also no difference in the total number of midline crosses between MPOA-X and SHAM males (NVE F(1,17) = .678, P = .422; EXP F(1,15) = .376, P = .549), indicating similar levels of activity across experimental groups.

3.2.2 Non-Contact Preference Test

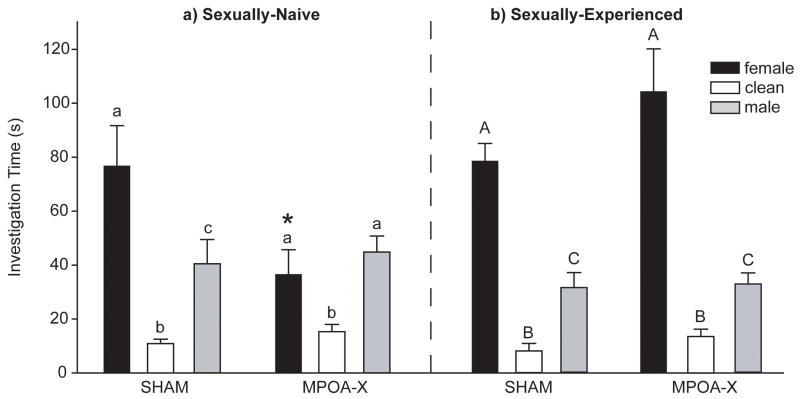

Lesions of MPOA decreased NVE males’ investigation of volatile female odors, resulting in an elimination of opposite-sex odor preference (Figure 2a). There was a significant interaction between lesion group and the duration of investigation of the three odor stimuli (F(2,48) =5.085, P = .010). Whereas SHAM males investigated female odors more than male odors (t(7) = 4.444, P = .004) and investigated both female odors (t(7) = 4.689, P = .003) and male odors (t(7) = 3.860, P = .008) more than clean odors, MPOA-X males spent equivalent amounts of time investigating female and male odors (t(10) = 1.128, P = .286), although they investigated both female odors (t(10) = 2.415, P = .036) and male odors (t(10) =5.830, P < .001) more than clean odors. In addition, MPOA-X males spent significantly less time investigating female odors than did SHAM males (F(1,17) = 5.917, P = .027).

Figure 2. Investigation Times for Non-Contact Preference Test.

a) In sexually-naïve males, lesions of MPOA eliminated preference for opposite-sex odors, whereas b) preference for opposite-sex odors remained intact in sexually-experienced males. Dissimilar letters indicate significant differences in investigation duration within lesion group, P < 0.05. * indicates significant differences in investigation duration between lesion groups, P < 0.05. Data expressed as means ± standard error of means.

In contrast to NVE subjects, EXP males with lesions of MPOA did not display a deficit in their preference to investigate volatile opposite-sex odors (Figure 2b). There was a significant main effect of odor stimulus (F(2,45) = 46.352, P < .001), but no interaction between lesion group and the duration of investigation for the three odor stimuli. Both SHAM and MPOA-X males spent significantly more time investigating female odors than male odors (SHAM t(6) = 7.011, P < .001; MPOA-X t(9) = 3.864, P = .004), and investigated both female odors (SHAM t(6) = 7.897, P < .001; MPOA-X t(9) =5.538, P < .001) and male odors (SHAM t(6) = 3.123, P = .020; MPOA-X t(9) = 4.383, P = .002) more than clean odors.

NVE subjects with unilateral or bilateral, partial damage to MPOA spent more time investigating female odors than male odors in the Non-Contact Preference Test. Interestingly, NVE and EXP subjects with damage that extended into pBNSTc did not investigate female odors more than male odors in the Non-Contact Preference Test (Table 1a).

Table 1. Summary of Odor Preference measures from males excluded from MPOA-X lesion group.

Unilateral or bilateral, partial lesions of MPOA do not disrupt sexually-naïve (NVE) or sexually-experienced (EXP) males’ preference to investigate female odors more than male or clean odors in a) Non-Contact or b) Contact Preference tests. In contrast, lesions that extend into pBNSTc eliminate preference for opposite-sex odors in the Non-Contact test only. Data expressed as mean ± standard error of means.

| a) Non-Contact | b) Contact | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Clean | Female | Male | Clean | |

| Unilateral NVE (n = 3) | 77.76 ± 13.70 | 36.89 ± 12.40 | 10.11 ± 4.22 | 61.80 ± 12.19 | 25.88 ± 3.6 | 7.7 ± 2.83 |

| Partial NVE (n = 4) | 99.63 ± 10.09 | 49.86 ± 5.95 | 11.67 ± 2.12 | 110.80 ± 6.56 | 59.66 ± 9.33 | 20.54 ± 1.13 |

| pBNSTc NVE (n = 1) | 67.62 | 64.75 | 22.12 | 126.48 | 42.51 | 20.20 |

| pBNSTc EXP (n = 4) | 43.66 ± 5.64 | 58.60 ± 32.95 | 10.79 ± 2.21 | 91.98 ± 5.43 | 33.54 ± 9.13 | 13.12 ± 5.46 |

3.2.3 Contact Preference Test

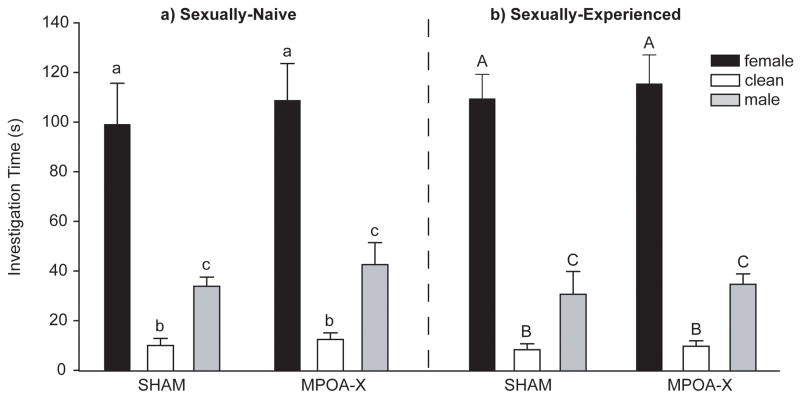

Lesions of MPOA did not affect NVE or EXP males’ preference for opposite-sex odors when contact with the odor stimuli was allowed. In NVE males, there was a significant main effect of odor stimulus (F(2,48) = 41.891, P < .001), but no interaction between lesion group and the duration of investigation of the three odor stimuli (Figure 3a). Both SHAM and MPOA-X males spent significantly more time investigating female odors than male odors (SHAM t(7) = 5.032, P = .002; MPOA-X t(10) = 3.330, P = .008) and investigated both female odors (SHAM t(7) = 6.585, P < .001; MPOA-X t(10) = 5.792, P < .001) and male odors (SHAM t(7) = 6.227, P < .001; MPOA-X (t(10) = 3.698, P = .004) more than clean odors.

Figure 3. Investigation Times for Contact Preference Test.

In a) sexually-naïve or b) sexually-experienced males, lesions of MPOA did not affect preference for opposite sex odors. Dissimilar letters indicate significant differences in investigation duration within lesion group, P < 0.05. Data expressed as means ± standard error of means.

In EXP males, there was also a significant main effect of odor stimulus (F(2,45) = 98.968, P < .001), but no interaction between lesion group and the duration of investigation of the three odor stimuli (Figure 3b). Both SHAM and MPOA-X males spent significantly more time investigating female odors than male odors (SHAM t(6) = 4.535, P = .004; MPOA-X t(9) = 7.526, P < .001) and investigated both female odors (SHAM t(6) = 11.243, P < .001; MPOA-X t(9) = 9.114, P < .001) and male odors (SHAM t(6) = 2.476, P = .048; MPOA-X (t(9) = 6.801, P < .001) more than clean odors.

NVE subjects with unilateral or bilateral, partial damage to MPOA spent more time investigating female odors than male odors in the Non-Contact Preference Test. Similarly, NVE and EXP subjects with damage that extended into pBNSTc spent more time investigating female odors than male odors in the Non-Contact Preference Test (Table 1b).

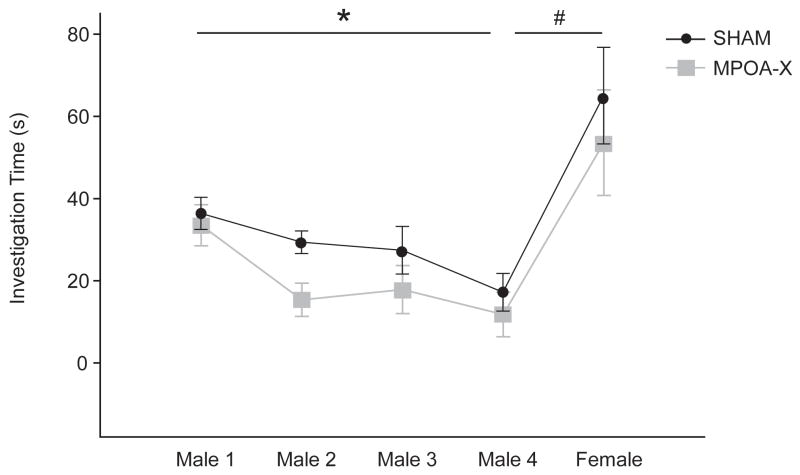

3.3 Odor Discrimination

NVE SHAM and MPOA-X males habituated to repeated presentations of different male odors, as indicated by decreased investigation of the male odor on the fourth trial compared to the first trial (SHAM t(7) = 2.104, P = .052; MPOA-X t(10) = 2.551, P = .031). Importantly, both lesion groups also dishabituated to a novel female odor, as indicated by an increased investigation of the female odor compared to the last presentation of the habituated male odor (SHAM t(7) = 4.425, P = .003; MPOA-X t(10) = 2.966, P = .016) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Investigation Times for Odor Discrimination Test.

Sexually-naïve SHAM and MPOA-X males both habituated their investigation to repeated presentations of male odors and increased their investigation to a subsequently presented female odor. * indicates a significant decrease between Male 1 and Male 4, P ≤ 0.05, # indicates a significant increase between Male 4 and Female, P < 0.05. Data expressed as means ± standard error of means.

3.4 Copulatory Behavior

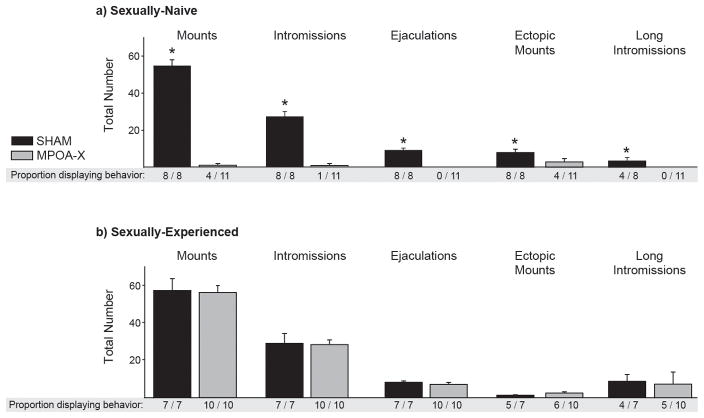

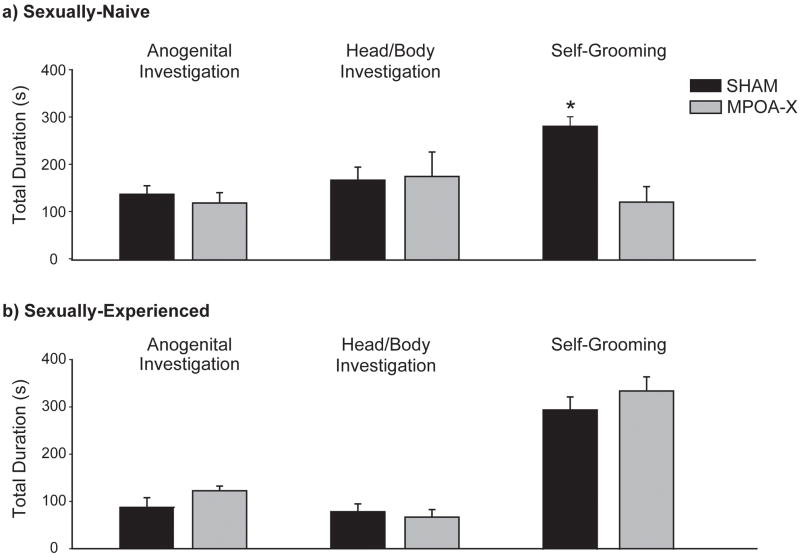

In NVE males, lesions of MPOA caused severe deficits in copulatory behavior. Whereas all SHAM males displayed mounts, intromissions, and ejaculations, only four out of eleven MPOA-X males mounted, one intromitted, and none achieved ejaculation. As a result of this, the total number of mating events for MPOA-X males did not follow a normal distribution; therefore the proportion of subjects displaying each mating event was compared between groups instead. The proportion of males displaying mounts (z = 2.839, P = .004), intromissions (z = 3.918, P < .001), ejaculations (z = 4.358, P < .001), ectopic mounts (z = 2.839, P < .004), and long intromissions (z = 2.639, P = .008) was significantly different between SHAM and MPOA-X groups (Figure 5a). Although SHAM and MPOA-X males did not differ in their total duration of anogenital investigation (F(1,16) =.398, P = .537) or head/body investigation (F(1,16) = .015, P = .904), MPOA-X spent significantly less time self-grooming than SHAM males (F(1,16) 15.195, P = .001) (Figure 6a). Derived measures of copulatory behavior were not calculated for NVE males, as the majority of subjects failed to intromit or ejaculate.

Figure 5. Total number of Mating Events in NVE and EXP males.

In sexually-naïve males, the proportion of MPOA-X males displaying mounts, intromissions, ejaculations, ectopic mounts, and long intromissions was significantly less than in SHAM males. b) In EXP males, the proportion of subjects displaying any mating event did not differ between SHAM and MPOA-X males. * indicates significant differences in proportions, P < 0.05. Data expressed as means ± standard error of means.

Figure 6. Total Durations of Mating Events in NVE and EXP males.

a) In sexually-naïve males, the total duration of anogenital and head/body investigation did not differ between SHAM and MPOA-X males, but MPOA-X males spent significantly less time self-grooming than did SHAM males. b) In sexually-experienced males, the total duration of anogenital investigation, head/body investigation, and self-grooming did not differ between SHAM and MPOA-X males. * indicates significant differences between lesion groups, P < .05. Data expressed as means ± standard error of means.

In contrast to NVE males, EXP males with lesions of MPOA displayed relatively normal copulatory behavior. All SHAM and MPOA-X males mounted, intromitted, and ejaculated, and the proportion of subjects displaying these behaviors did not differ between groups (Figure 5b). Furthermore, the proportion of subjects displaying ectopic mounts (z = 0.485, P = .627) and long intromissions (z = 0.290, P = .772) did not differ between SHAM and MPOA-X males (Figure 5b), nor did the total duration of anogenital investigation (F(1,14) = 2.753, P = .119), head/body investigation (F(1,14) = .240, P = .632), and self-grooming (F(1,14) = .930, P = .351) (Figure 6b).

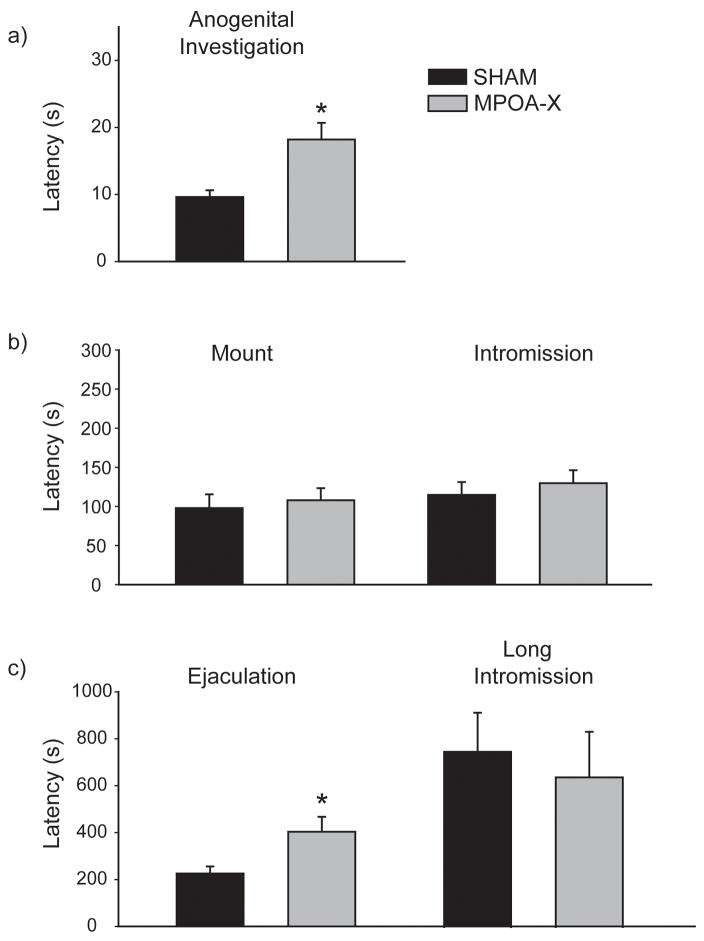

There were, however, subtle differences in the temporal pattern of mating between EXP SHAM and MPOA-X males. MPOA-X males took significantly longer to begin anogenital investigation (Figure 7a) (F(1,14) = 8.401, P = .012) and displayed significantly longer ejaculation latencies (F(1,14) = 5.339, P = .037) than did SHAM males (Figure 7c). These differences remained significant even after data was corrected for the latency to begin anogenital investigation. In contrast, the latencies to first mount (F(1,14) = 2.288, P = .153) and first intromission (F(1,14) = 2.812, P = .116) did not differ between SHAM and MPOA-X males (Figure 7b), nor did latency to display long intromissions (F(1,4) = 1.522, P = .285) (Figure 7c). Finally, EXP MPOA-X males did not differ from SHAM males in any derived measure of copulatory behavior (Table 2).

Figure 7. Latencies to Mating Events in EXP males.

Lesions of MPOA increased the latency to a) begin anogenital investigation and c) ejaculate in sexually-experienced males, although the latencies to display mounts, intromissions, and long intromissions did not differ between SHAM and MPOA-X males, * indicates P < 0.05. Data expressed as means ± standard error of means.

Table 2. Derived measures of mating events for EXP males.

In sexually-experienced subjects, MPOA-X males did not differ from SHAM males in any derived measure of copulation. Data expressed as mean ± standard error of means.

| SHAM | MPOA-X | |

|---|---|---|

|

Derived Measures | ||

| PEI | 41.43 ± 4.87 | 39.12 ± 5.66 |

| I-E | 9.33 ± 1.68 | 8.88 ± 1.20 |

| ME | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.01 |

NVE subjects with unilateral or bilateral, partial damage to MPOA performed at levels comparable to SHAM males on all measures of copulatory behavior (Table 3a). In contrast, subjects with damage that extended into pBNSTc were severely impaired in their copulatory behavior. Only one EXP male with pBNSTc damage displayed a single bout of mounting that resulted in one intromission, whereas all other males with pBNSTc damage (NVE and EXP) failed to mount, intromit, or ejaculate (Table 3b).

Table 3. Total number of mating events in males excluded from MPOA-X lesion group.

Unilateral or bilateral, partial lesions of MPOA do not disrupt a) sexually-naïve (NVE) or b) sexually-experienced (EXP) males’ total number of mounts, intromissions, ejaculations, or long intromissions. In contrast, lesions extending into pBNSTc cause copulatory deficits in a) NVE and b) EXP males. Data expressed as mean ± standard error of means.

| Mating Events |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | I | E | LI | |

|

a) NVE | ||||

| Unilateral (n = 3) | 44.33 ± 7.96 | 18.00 ± 1.52 | 6.66 ± 0.88 | 6.33 ± 1.85 |

| Partial (n = 4) | 54. 25 ± 10.06 | 31.75 ± 6.70 | 6.75 ± 0.85 | 5.50 ± 0.35 |

| pBNSTc (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

b) EXP | ||||

| pBNSTc (n = 3) | 1.66 ± 1.66 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 0 | 0 |

4. DISCUSSION

4.1 Summary

This study is the first to comprehensively test the role of MPOA in the processing of distal and proximate sexual odor cues and copulatory behavior in both sexually-naïve and sexually-experienced males. We found that excitotoxic lesions specific to MPOA eliminate preference for volatile opposite-sex odors in sexually-naïve male Syrian hamsters. Importantly, this lack of preference was not due to an inability to discriminate between odors, as MPOA-X males, like SHAM males, could discriminate between volatile male and female odors in a habituation-dishabituation test. Preference for opposite-sex odors remained intact, however, when subjects were allowed to contact the sexual odors, supporting our prediction that MPOA is more critical for the initial approach and investigation of volatile female odors, rather than close, intensive investigation of non-volatile female odors. In addition, subjects with sexual experience were unimpaired in their preference for opposite-sex odors under both stimulus conditions. Surprisingly, lesions of MPOA severely compromised copulatory behavior only in sexually-naïve males, conflicting with previous reports of copulatory deficits following electrolytic lesions of MPOA in sexually-experienced male hamsters (Powers et al. 1987; Floody 1989).

4.2 Role of MPOA in opposite-sex odor preference

The finding that lesions of MPOA eliminate preference for volatile opposite-sex odors in male hamsters is congruent with previous studies that suggest MPOA mediates males’ unconditioned anticipatory responding to a female or her odors. In male rats, for example, large, electrolytic lesions that include MPOA decrease preference for estrous female bedding over non-estrous female bedding (Hurtazo and Paredes 2005), preference to interact with a female over a male (Paredes et al. 1998), and pursuit of females (Paredes et al. 1993). Similarly, temporary inactivation of MPOA using lidocaine decreases the amount of time male rats spend near a female in an incentive motivation test where subjects can choose to spend time near a female or male stimulus animal that they cannot contact (Hurtazo et al. 2008). In male ferrets, electrolytic (Kindon et al. 1996) or excitotoxic (Paredes and Baum 1995) lesions that include MPOA reverse the normal preference for approaching and interacting with females over males. Finally, MPOA also mediates anticipatory responses to females in other comparative animal models, including anogenital investigation, tongue-flicking, and anticipatory erections in male marmosets (Lloyd and Dixson 1988), preference to view females over males in male Japanese Quails (Balthazart et al. 1998), and pre-copulatory courtship behaviors in male garter snakes (Friedman and Crews 1985). Together, these data suggest that MPOA mediates males’ anticipatory responses to female cues in a variety of conditions, sensory modalities, and species.

4.3 Role of Odor Volatility

The results of the current study also suggest the importance of MPOA for male attraction to female odors depends on the volatility of the odor cues available. When only volatile odors are present, as would be the case when animals are detecting odors from a distance, they are processed primarily by MOS. The primary source of MOS information to the MPOA is via afferents from MA, a structure that receives both direct and indirect input from the main olfactory bulbs (Scalia and Winans 1975). As with lesions of MPOA in the current study, lesions of MA eliminate preference for volatile, opposite-sex odors (Maras and Petrulis 2006), suggesting that interactions between MA and MPOA are critical for the appropriate investigation of volatile odors. It is also possible that both MA and pBNST must interact with MPOA to regulate volatile odor investigation, as excitotoxic lesions of pBNST also eliminate preference for volatile, opposite-sex odors (Been and Petrulis 2010).

The present results confirm a previous report of MPOA lesions not disrupting male hamsters’ investigation of directly-contacted female odors (Powers et al. 1987). This suggests that when non-volatile odors are present, and the AOS is additionally recruited (Keller et al. 2009), nuclei that receive direct AOS projections, such as MA and pBNST (Scalia and Winans 1975), do not modulate direct odor investigation via MPOA. Instead, connections between MA and/or pBNST and other nuclei, such as the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), ventral premammillary nucleus (PMV), or the nucleus accumbens (NAc) may mediate males’ preference for directly-contacted opposite-sex odors. This idea is supported by the fact that lesions of either MA or pBNST decrease male hamsters’ investigation of female odors when contact is allowed (Lehman et al. 1980; Been and Petrulis 2010). Furthermore, in male hamsters, VMH, PMV, and NAc express Fos protein following exposure to female odors that they can contact (Kollack-Walker and Newman 1995) and lesions of VMH disrupt female ferrets’ preference for male odors that they can contact (Robarts and Baum 2007).

4.4 Role of MPOA in copulatory behavior

Lesions of MPOA caused significant impairments in copulatory behavior in sexually-naïve male hamsters, but only caused subtle deficits in sexually-experienced males. This finding differs notably from previous reports of large, electrolytic MPOA lesions causing severe copulatory deficits in sexually-experienced male hamsters (Powers et al. 1987; Floody 1989). Unlike previous studies, subjects in the present experiment were excluded from the MPOA-X lesion group if lesion damage extended into pBNSTc. This is an important distinction, as damage to this region may cause severe disruption of male copulatory behavior. In the current study, for example, both sexually-naïve and sexually-experienced males with lesion damage that extended into pBNSTc (and therefore excluded from the MPOA-X group) had severe deficits in copulatory behavior. Furthermore, only large, electrolytic lesions of BNST cause severe mating deficits in male hamsters, whereas smaller or excitotoxic lesions that do not damage pBNSTc cause more subtle copulatory deficits (Powers et al. 1987; Been and Petrulis 2010). Similarly, lesions of the sexually-dimorphic nucleus of MPOA in male rats, which do not damage pBNSTc, only cause severe deficits in copulatory behavior in sexually-naïve males (De Jonge et al. 1989); copulatory deficits in sexually-experienced males with similar lesions are subtle and temporary (Arendash and Gorski 1983). Finally, disconnecting the sexually-dimporphic area of the MPOA from the caudal part of the medial BNST severely disrupts copulation in sexually-experienced male gerbils (Sayag et al. 1994). It is therefore possible that pBNSTc, and not MPOA itself, is critical for copulatory behavior in sexually-experienced males.

The current study also differs from previous reports in that the lesions made by Powers and colleagues (1987) were electrolytic and therefore were not limited to neurons, but also damaged fibers of passage. Therefore, it is possible that the copulatory deficits observed in the previous study were not due to damage to MPOA itself, but rather resulted from the disruption of social odor information from MA and/or pBNST that passes through MPOA to other hypothalamic nuclei critical for male reproductive behavior. In addition, whereas the subjects in the current study were gonadectomized and maintained on exogenous testosterone, the subjects in Powers et. al. were gonadally-intact. It is therefore possible that differences in post-lesion copulatory behavior were due not to lesion size or technique, but rather to the endocrine status of the subjects. This seems unlikely, however, as we demonstrated that gonadally-intact males are indistinguishable from castrated and hormone-replaced males in their copulatory behavior. Finally, MPOA is a heterogeneous structure and so it is possible that damage to additional structures within or near MPOA would have led to greater deficits in sexually-experienced males. For example, PVH, which did not sustain significant, bilateral damage in the current study, may be important for copulatory reflexes. Although radiofrequency lesions of PVH increase ejaculation latencies in sexually-experienced male rats (Liu et al. 1997), it seems unlikely that PVH is critical for regulating copulation, as smaller, excitotoxic lesions of PVH do not impair copulation in sexually-experienced male rats (Liu et al. 1997).

4.5 Role of Sexual Experience

Our results demonstrate that prior sexual experience can compensate for MPOA lesion-induced deficits in the appropriate investigation of volatile social odors and deficits in copulatory behavior, suggesting that sexual experience changes how female reproductive cues are processed centrally. Sexual experience may lead to a more distributed processing of female odor and/or other sensory cues such that MPOA becomes redundant and is no longer required for the appropriate behavioral response to female cues. This type of experience-dependent plasticity may result from associations between volatile odors and copulatory cues learned during sexual experience. In male rats, for example, exposure to estrous female odors increases immediate early gene expression in a circuit that includes MPOA, whereas exposure to an artificial odor that has previously been paired with a sexually-receptive female induces immediate early gene expression in a different neural pathway that includes the NAc (Kippin et al. 2003). As such, MPOA may be required for the appropriate behavioral response to a female or her odors in sexually-naïve males, but following sexual experience, the same stimuli may elicit a conditioned behavioral response that is mediated by NAc and associated circuitry (Pfaus et al. 2001). Of the cues available during copulation, non-volatile odor cues may be the most critical for the formation of associations with the attractive properties of volatile female odor cues. In fact, allowing male hamsters contact with volatile and non-volatile female odors (and not sexually experience per se) is sufficient to rescue the deficits in copulatory behavior following VNO removal (Westberry and Meredith 2003). Although male hamsters do not require sexual experience to show a preference for volatile, opposite-sex odors (Maras and Petrulis 2006; Ballard and Wood 2007), our finding that lesions of MPOA only eliminate preference in the non-contact condition suggests that attraction to a combination of non-volatile and volatile female odors is more robust than attraction to just volatile opposite-sex odors. If a learned association with non-volatile female odors (as would occur either during close investigation or copulation) is required to strengthen preference for opposite-sex volatile odors, then it is not surprising that volatile odor preference is more susceptible to lesion-induced deficits in sexually-naïve males than in sexually-experienced males, as these males have not had contact with a female or with non-volatile female odors.

4.6 Conclusions

Although previous lesion studies have examined the role of MPOA in reproductive behavior, this study is the first to comprehensively test the role of MPOA in both appetitive and consummatory reproductive behavior while directly addressing the effects of sexual experience and odor volatility. Together, these results demonstrate that MPOA mediates preference for volatile female odors and copulatory behavior only in sexually-naïve male Syrian hamsters. In contrast, we found no support for previous reports that lesions of MPOA cause severe copulatory deficits in sexually-experienced male hamsters and suggest that these deficits are more likely mediated by damage to pBNSTc. Although the lesions in the current study are specific to MPOA, it would be valuable to further delineate the role of subnuclei within MPOA. Indeed, Ball and Balthazart (Balthazart and Ball 2007) have suggested that the rostral MPOA may be more important for appetitive reproductive behavior whereas the caudal MPOA may be more critical for consummatory reproductive behaviors. Ultimately, a more detailed analysis of the functional microstructure of MPOA is needed to identify specific neural regulators of appetitive and consummatory reproductive behaviors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mary Karom for performing the testosterone radioimmunoassays for this study. We would also like to thank Shelease Johnson and Nina King for their assistance in collecting behavioral data. This work was supported by NIH grant MH072930 to A. P. and in part by the Center for Behavioral Neuroscience under the STC program of the NSF, under agreement IBN 9876754.

Abbreviations

- AGI

anogenital investigation

- AH

anterior hypothalamus

- AOS

accessory olfactory system

- E

ejaculation

- EXP

sexually-experienced

- HBI

head/body investigation

- I

intromission

- I-E

intromissions to ejaculation

- LI

long intromission

- M

mount

- ME

mounting efficiency

- MA

medial amygdala

- MOS

main olfactory system

- MPN

medial preoptic nucleus

- MPNmag

magnocellular medial preoptic nucleus

- MPOA

medial preoptic area

- NAc

nucleus accumbens

- NeuN

neuronal nuclei protein

- NVE

sexually-naïve

- pBNST

posterior bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- pBNSTc

caudal posterior bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- PEI

post-ejaculatory interval

- PMV

ventral premammillary nucleus

- PVH

periventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus

- SG

self-grooming

- VMH

ventromedial hypothalamus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Laura E. Been, Email: lbeen1@student.gsu.edu.

Aras Petrulis, Email: apetrulis@gsu.edu.

References

- Arendash GW, Gorski RA. Effects of discrete lesions of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area or other medial preoptic regions on the sexual behavior of male rats. Brain Res Bull. 1983;10(1):147–54. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(83)90086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard CL, Wood RI. Partner preference in male hamsters: steroids, sexual experience and chemosensory cues. Physiol Behav. 2007;91(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazart J, Absil P, et al. Appetitive and consummatory male sexual behavior in Japanese quail are differentially regulated by subregions of the preoptic medial nucleus. J Neurosci. 1998;18(16):6512–27. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06512.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazart J, Ball GF. Topography in the preoptic region: differential regulation of appetitive and consummatory male sexual behaviors. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2007;28(4):161–78. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazart J, Surlemont C. Copulatory behavior is controlled by the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the quail POA. Brain Res Bull. 1990;25(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90246-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum MJ, Keverne EB. Sex difference in attraction thresholds for volatile odors from male and estrous female mouse urine. Horm Behav. 2002;41(2):213–9. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean NY, Nunez AA, et al. Effects of medial preoptic lesions on male mouse ultrasonic vocalizations and copulatory behavior. Brain Res Bull. 1981;6(2):109–12. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(81)80033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Been L, Petrulis A. Lesions of the posterior bed nucleus of the stria terminalis eliminate opposite-sex odor preference and delay copulation in male Syrian hamsters: role of odor volatility and sexual experence. Eur J Neurosci. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breer H. Olfactory receptors: molecular basis for recognition and discrimination of odors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003;377(3):427–33. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell BN, Boland BD, et al. Copulatory behavior of golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) Behaviour. 1977;61(3–4):180–206. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TT, Clancy AN, et al. Conversion of testosterone to estradiol may not be necessary for the expression of mating behavior in male Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) Horm Behav. 2000;37(3):237–45. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2000.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge FH, Louwerse AL, et al. Lesions of the SDN-POA inhibit sexual behavior of male Wistar rats. Brain Res Bull. 1989;23(6):483–92. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floody OR. Dissociation of hypothalamic effects on ultrasound production and copulation. Physiol Behav. 1989;46(2):299–307. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90271-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D, Crews D. Role of the anterior hypothalamus-preoptic area in the regulation of courtship behavior in the male Canadian red-sided garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis parietalis): intracranial implantation experiments. Horm Behav. 1985;19(2):122–36. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(85)90013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtazo HA, Paredes RG. Olfactory preference and Fos expression in the accessory olfactory system of male rats with bilateral lesions of the medial preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 2005;135(4):1035–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtazo HA, Paredes RG, et al. Inactivation of the medial preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus by lidocaine reduces male sexual behavior and sexual incentive motivation in male rats. Neuroscience. 2008;152(2):331–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RE. Contemporary Issues in Comparative Psychology. D. A. Dewsbury; Sunderland, MA, Sinauer: 1990. Chemical communication in golden hamsters: from behavior to molecules and neural mechanisms; pp. 381–412. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RE. Memory for individual scent in hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) as assessed by habituation methods. J Comp Psychol. 1993;107(2):201–7. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.107.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M, Baum MJ, et al. The main and the accessory olfactory systems interact in the control of mate recognition and sexual behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2009;200(2):268–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindon HA, Baum MJ, et al. Medial preoptic/anterior hypothalamic lesions induce a female-typical profile of sexual partner preference in male ferrets. Horm Behav. 1996;30(4):514–27. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1996.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston PA, Crews D. Effects of hypothalamic lesions on courtship and copulatory behavior in sexual and unisexual whiptail lizards. Brain Res. 1994;643(1–2):349–51. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippin TE, Cain SW, et al. Estrous odors and sexually conditioned neutral odors activate separate neural pathways in the male rat. Neuroscience. 2003;117(4):971–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00972-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollack-Walker S, Newman SW. Mating and agonistic behavior produce different patterns of Fos immunolabeling in the male Syrian hamster brain. Neuroscience. 1995;66(3):721–36. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00563-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y, Arai Y. Functional association between the medial amygdala and the medial preoptic area in regulation of mating behavior in the male rat. Physiol Behav. 1995;57(1):69–73. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00205-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman MN, Powers JB, et al. Stria terminalis lesions alter the temporal pattern of copulatory behavior in the male golden hamster. Behav Brain Res. 1983;8(1):109–28. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(83)90174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman MN, Winans SS, et al. Medial nucleus of the amygdala mediates chemosensory control of male hamster sexual behavior. Science. 1980;210(4469):557–60. doi: 10.1126/science.7423209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YC, Salamone JD, et al. Impaired sexual response after lesions of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in male rats. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111(6):1361–7. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.6.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YC, Salamone JD, et al. Lesions in medial preoptic area and bed nucleus of stria terminalis: differential effects on copulatory behavior and noncontact erection in male rats. J Neurosci. 1997;17(13):5245–53. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05245.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd SA, Dixson AF. Effects of hypothalamic lesions upon the sexual and social behaviour of the male common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) Brain Res. 1988;463(2):317–29. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrides F, Bartke A, et al. Effects of exposure to vaginal odor and receptive females on plasma testosterone in the male hamster. Neuroendocrinology. 1974;15(6):355–64. doi: 10.1159/000122326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malsbury CW. Facilitation of male rat copulatory behavior by electrical stimulation of the medial preoptic area. Physiol Behav. 1971;7(6):797–805. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(71)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maras PM, Petrulis A. Chemosensory and steroid-responsive regions of the medial amygdala regulate distinct aspects of opposite-sex odor preference in male Syrian hamsters. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24(12):3541–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin LP, Wood RI. A Stereotaxic Atlas of the Golden Hamster Brain. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MR, Schneider GE. Olfactory bulb removal eliminates mating behavior in the male golden hamster. Science. 1970;167(916):302–4. doi: 10.1126/science.167.3916.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes R, Haller AE, et al. Medial preoptic area kindling induces sexual behavior in sexually inactive male rats. Brain Res. 1990;515(1–2):20–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90571-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes RG, Baum MJ. Altered sexual partner preference in male ferrets given excitotoxic lesions of the preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus. J Neurosci. 1995;15(10):6619–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06619.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes RG, Highland L, et al. Socio-sexual behavior in male rats after lesions of the medial preoptic area: evidence for reduced sexual motivation. Brain Res. 1993;618(2):271–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91275-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes RG, Tzschentke T, et al. Lesions of the medial preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus (MPOA/AH) modify partner preference in male rats. Brain Res. 1998;813(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00914-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt DB, Newman SW. Fos-immunoreactivity within the extended amygdala is correlated with the onset of sexual satiety. Horm Behav. 1998;34(1):17–29. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaus JG, Kippin TE, et al. Conditioning and sexual behavior: a review. Horm Behav. 2001;40(2):291–321. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer CA, Johnston RE. Socially stimulated androgen surges in male hamsters: the roles of vaginal secretions, behavioral interactions, and housing conditions. Horm Behav. 1992;26(2):283–93. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(92)90048-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JB, Fields RB, et al. Olfactory and vomeronasal system participation in male hamsters’ attraction to female vaginal secretions. Physiol Behav. 1979;22(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(79)90407-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JB, Newman SW, et al. MPOA and BNST lesions in male Syrian hamsters: differential effects on copulatory and chemoinvestigatory behaviors. Behav Brain Res. 1987;23(3):181–95. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(87)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JB, Winans SS. Vomeronasal organ: critical role in mediating sexual behavior of the male hamster. Science. 1975;187(4180):961–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1145182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robarts DW, Baum MJ. Ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus lesions disrupt olfactory mate recognition and receptivity in female ferrets. Horm Behav. 2007;51(1):104–13. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbch.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Manzo G, Pellicer F, et al. Stimulation of the medial preoptic area facilitates sexual behavior but does not reverse sexual satiation. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114(3):553–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayag N, Hoffman NW, et al. Telencephalic connections of the sexually dimorphic area of the gerbil hypothalamus that influence male sexual behavior. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108(4):743–57. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalia F, Winans SS. The differential projections of the olfactory bulb and accessory olfactory bulb in mammals. J Comp Neurol. 1975;161(1):31–55. doi: 10.1002/cne.901610105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westberry JM, Meredith M. Pre-exposure to female chemosignals or intracerebral GnRH restores mating behavior in naive male hamsters with vomeronasal organ lesions. Chem Senses. 2003;28(3):191–6. doi: 10.1093/chemse/28.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RI. Thinking about networks in the control of male hamster sexual behavior. Horm Behav. 1997;32(1):40–5. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RI, Swann JM. The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the Syrian hamster: subnuclei and connections of the posterior division. Neuroscience. 2005;135(1):155–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]