Abstract

Using intrachoroidal injection of the transneuronal retrograde tracer pseudorabies virus (PRV) in rats, we previously localized preganglionic neurons in the superior salivatory nucleus (SSN) that regulate choroidal blood flow (ChBF) via projections to the pterygopalatine ganglion (PPG). In the present study, we used higher order transneuronal retrograde labeling following intrachoroidal PRV injection to identify central neuronal cell groups involved in parasympathetic regulation of ChBF via input to the SSN. These prominently included the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), both of which are responsive to systemic BP, and are involved in systemic sympathetic vasoconstriction. Conventional pathway tracing methods were then used to determine if the PVN and/or NTS project directly to the choroidal subdivision of the SSN. Following retrograde tracer injection into SSN (biotinylated dextran amine 3K or Fluorogold), labeled perikarya were found in PVN and NTS. Injection of the anterograde tracer, biotinylated dextran amine 10K (BDA10K) into PVN or NTS resulted in densely packed BDA10K+ terminals in prechoroidal SSN (as defined by its enrichment in nitric oxide synthase-containing perikarya). Double-label studies showed these inputs ended directly on prechoroidal nitric oxide synthase-containing neurons of SSN. Our study thus establishes that PVN and NTS project directly to the part of SSN involved in parasympathetic vasodilatory control of the choroid via the PPG. These results suggest that control of ChBF may be linked to systemic blood pressure and central control of the systemic vasculature.

Keywords: biotinylated dextran amine (BDA), pseudorabies virus (PRV), choroidal blood flow (ChBF), superior salivatory nucleus (SSN), paraventricular nucleus (PVN), nucleus of solitary tract (NTS)

1. INTRODUCTION

The choroid contains the blood supply to the outer retina. The choroid and blood vessels supplying the choroid are innervated by parasympathetic, sympathetic and sensory nerve fibers that adaptively regulate choroidal blood flow (ChBF) according to retinal need (Bill, 1984; Bill, 1985; Bill, 1991; Cuthbertson et al., 1996; Cuthbertson et al., 1997; Fitzgerald et al., 1990a; Fitzgerald et al., 1990b; Fitzgerald et al., 1996; Guglielmone and Cantino, 1982; Kirby et al., 1978; Stone et al., 1987). Such adaptive control may be important for maintaining the health of retinal photoreceptors and maintaining normal visual function (Fitzgerald et al., 1990a; Fitzgerald et al., 1990b; Fitzgerald et al., 2001; Hodos et al., 1998; Potts, 1966; Reiner et al., 1983; Shih et al., 1993; Shih et al., 1994). The pterygopalatine ganglion (PPG) is the major source of parasympathetic input to the choroid and orbital vessels, and this input utilizes two vasodilators: vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and nitric oxide (NO) (Alm et al., 1995; Bill, 1984; Bill, 1985; Bill, 1991; Ruskell, 1971a; Stone, 1986; Stone et al., 1987; Uddman et al., 1980a; Yamamoto et al., 1993). These fibers also appear to be cholinergic (Johansson and Lundberg, 1981; Lundberg et al., 1981; Lundberg et al., 1982; Suzuki et al., 1990).

The PPG receives its preganglionic input from the superior salivatory nucleus (SSN) of the hindbrain via the greater petrosal branch of the facial nerve (Contreras et al., 1980; Ng et al., 1994; Nicholson and Severin, 1981; Schrödl et al., 2006; Spencer et al., 1990; Tóth et al., 1999). The SSN itself is located dorsolateral to the rostral part of the facial motor nucleus. The SSN neurons, which are somewhat intermingled with noradrenergic neurons of the more rostrally situated A5 cell group, are cholinergic. In rats, rabbits and humans, a subset has been reported to contain nitric oxide synthase (NOS), as well (Cuthbertson et al., 2003; Gai and Blessing, 1996; Zhu et al., 1996; Zhu et al., 1997). The SSN also provides preganglionic input via the corda tympani nerve to the submandibular ganglion (Contreras et al., 1980; Jansen et al., 1992; Ng et al., 1994; Nicholson and Severin, 1981), which sends postganglionic fibers to the submandibular and sublingual glands, and thereby regulates blood flow and salivary secretion within these glands (Izumi and Karita, 1994). The PPG, in addition to its innervation of choroidal and orbital blood vessels, also innervates the Meibomian glands, the lacrimal gland, the Harderian gland, blood vessels of the nasal mucosa and palate, and cerebral blood vessels (LeDoux et al., 2001; Nakai et al., 1993; Ruskell, 1965; Ruskell, 1971b; Ten Tusscher et al., 1990; Uddman et al., 1980b; van der Werf et al., 1996). Thus, functionally diverse types of preganglionic neurons are present within the SSN.

The locations within the SSN of the preganglionic neurons controlling the salivary glands (Tóth et al., 1999), Meibomian glands (LeDoux et al., 2001), the lacrimal gland (Tóth et al., 1999) and the choroid (Cuthbertson et al., 2003) have been described. While these functionally diverse populations have slightly differing distributions, overlap among them is nonetheless present, especially for those innervating orbital structures. The present study investigated the projection of two neuronal populations to prechoroidal SSN neurons, which can be identified within the SSN partly by their location, and notably by their enrichment in NOS (Cuthbertson et al., 2003). Using intrachoroidal injection of the transneuronal retrograde tracer, the Bartha strain of pseudorabies virus (PRV), in adult rats, we observed higher order labeling of many neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), and the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), among other regions. The PRV studies could not, however, determine if these projections were direct or multisynaptic. The inputs of PVN and NTS to prechoroidal SSN are of particular interest, as these two nuclei play important roles in cardiovascular regulation. Consequently we confirmed the direct projections of these two neuronal cell groups to the SSN by a combination of retrograde pathway tracing with biotinylated dextran amine 3000kD MW (BDA3K) or Fluorogold (FG), and anterograde pathway tracing with biotinylated dextran amine 10000kD MW (BDA10K) in conjunction with the identification of prechoroidal SSN by NOS immunolabeling.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Transneuronal retrograde tracer (PRV) injection into choroid

Using PRV labeling in brain after intrachoroidal PRV injection to delineate central pathways controlling ChBF depends importantly on limiting the injection site to the choroid. We could judge this was the case if the central neuronal labeling prominently included SSN, with minimal or no labeling in facial, oculomotor or abducens motoneurons, or nucleus of Edinger-Westphal preganglionic neurons. Minute (0.5μl) injections (rats RF8, RF11-08, RF12-08) favored this outcome. Additionally, short survival times (<55 hours) that limited collateral spread of virus (rat RF7) also favored restricting labeling to central choroidal circuits. The PRV findings we report here are based on cases that met these criteria. In such cases, prominent labeling was observed within a cluster of neurons in rostromedial SSN, namely that controlling ChBF. The higher-order PRV+ neuronal labeling seen in these cases included many additional structures, notably PVN, the lateral parabrachial nucleus (PBL), the periaqueductal central gray (PAG), the raphe magnus of the pons, the A5 cell group, and NTS. A full description of the higher order labeling in brain after intrachoroidal PRV injection will be provided in a later publication. In the present study, we particularly focus on PVN and NTS, because of their demonstrated role in peripheral cardiovascular regulation (Badoer and Merolli, 1998; Ciriello, 1983; Godino et al., 2005; Krukoff et al., 1997; Rogers et al., 1993; Spencer et al., 1990). The PRV+ neuron distributions within PVN, SSN, and NTS are shown in Figure 1 for one rat that survived 69 hrs (R3-07). Labeled cells were tightly clustered in SSN (Fig. 1B). Within PVN, PRV+ neurons were located in the ipsilateral dorsolateral posterior PVN, with a few PRV+ neurons located contralaterally (Fig. 1A). Within NTS, PRV+ neurons were observed posteriorly and dorsally in ipsilateral NTS (Fig. 1C&D). Although transneuronal retrograde pathway tracing with PRV identifies circuits, it cannot establish if the connections among any members of the circuits are direct or polysynaptic. We thus next carried out conventional pathway tracing studies to determine if PVN and NTS project directly to choroidal SSN.

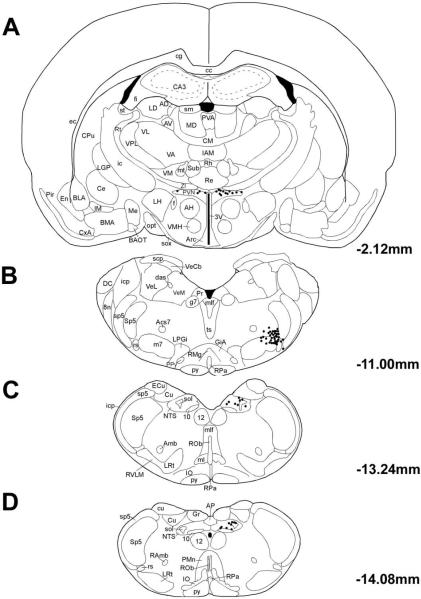

Fig. 1.

Line drawing of coronal sections at the levels of PVN (Bregma −2.12 mm), SSN (Bregma −11.00 mm) and NTS (Bregma −13.24 mm and Bregma −14.08 mm), with schematics based on the rat atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1994), showing the distribution of PRV+ neurons in rat R3-07, in which the PRV injection was well confined to the right choroid and yielded extensive higher-order labeling in PVN and NTS. Each filled circle represents one PRV+ neuron.

2.2. FG or BDA3K injection into SSN

To determine if PVN and NTS project directly to the region of SSN containing the choroidal-control preganglionic neurons, we injected either the retrograde tracer FG or the retrograde tracer BDA3K into SSN, either by iontophoresis or pressure injection with microsyringe. The animals with such injections are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Cases Involving Retrograde Labeling of PVN and NTS Neurons from SSN Using Fluorogold or BDA3K

| Rat ID | Injection Method | Injection Site | Location of Retrogradely Labeled Neurons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of SSN Injected | Region of Spread beyond SSN | Ipsilat PVN | Contral at PVN | Ipsilat NTS | Contralat NTS | ||

| RBPH38, 39, 41 | Pressure FG | Central SSN | Spinal 5, principle 5, nerve 7, motor 7, ISN | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | ++ * |

| RBPH42 | Pressure FG | Laterodorsal SSN | Motor 5, spinal 5, principle 5, nerve 7, SO, MVe | +++ | + | +++ | + |

| RBPH37 | Pressure FG | Ventral SSN | A5, SO, principle 5, spinal 5, motor 7, nerve 7 | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | ++ * |

| RBPH40 | Pressure FG | None | Nucleus subcoeruleus, motor 5, spinal 5, principle 5 | - | - | - | - |

| RBP64 | Pressure BDA | Central SSN | Spinal 5, motor 7 | + | - | ++ | - |

| RBP65 | Pressure BDA | Central SSN | Principle 5, spinal 5, motor 7, nerve 7 | + | - | ++ | - |

| RBP60 | Pressure BDA | Lateral SSN | Principle 5, spinal 5, motor 7 | - | - | + | - |

| RBP56 | Pressure BDA | None | Spinal 5 | - | - | - | - |

| RBP63 | Pressure BDA | None | Spinal 5 | - | - | - | - |

| RBP46 | Iontophoresis BDA | Central SSN | None | + | - | + | - |

| RBP47 | Iontophoresis BDA | Central SSN | Spinal 5 | + | - | + | - |

| RBP53, 55 | Iontophoresis BDA | Central SSN | Spinal 5 | - | - | + | - |

| RBP40, 42 | Iontophoresis BDA | None | Lateral spinal 5 | - | - | - | - |

| RBP43 | Iontophoresis BDA | None | Spinal 5, rostral nerve 7 | - | - | - | - |

| RBP45 | Iontophoresis BDA | None | Nerve 7, IRt | - | - | + | - |

indicates retrogradely labeled neurons only found in NTS posterior to obex.

no retrogradely labeled neurons

few retrogradely labeled neurons

some retrogradely labeled neurons

many number of retrogradely labeled neurons

extensive retrogradely labeled neurons

2.2.1. FG pressure injection into SSN

Six rats received FG into SSN by pressure injection. The injection sites for these six cases are illustrated in Figure 2. In five of these cases (RBPH37, RBPH38, RBPH39, RBPH41, and RBPH42), the FG injection sites were largely or entirely centered on SSN. In all five, numerous FG+ neurons were found in PVN and NTS. Images of the injection site (Fig. 3A), and the FG labeling within PVN (Fig. 3B&C) and NTS (Fig. 3D–F) for one representative case (RBPH41) are shown in Figure 3. The injection site includes the choroidal SSN, with spread to the principal and spinal trigeminal nuclei, facial motor nucleus, facial nerve, and inferior salivatory nucleus (ISN). In this and the other four cases with FG injection into SSN, FG+ neurons were observed in PVN on both sides, with more ipsilaterally (Fig. 3B&C). Within ipsilateral PVN, the labeled neurons were most common posteriorly and dorsally. FG+ neurons were also found bilaterally within the NTS in the five cases with FG injection into SSN, with an ipsilateral predominance as well (Fig. 3D–F). The labeled neurons were particularly abundant in ipsilateral NTS at or just rostral to the obex. It is important to note that these SSN injections also retrogradely labeled neurons in other regions containing PRV+ neurons after intrachoroidal injection, but we will not detail these here due to our focus on PVN and NTS. In one case (RBPH40) that served as a control, the FG injection was rostrolateral to SSN and included the nucleus subcoeruleus, motor trigeminal nucleus, the principal trigeminal nucleus, and the spinal trigeminal nucleus. No FG+ neurons were observed in PVN or NTS in this case. Thus, neither PVN nor NTS project to the nucleus subcoeruleus, motor trigeminal nucleus, the principal trigeminal nucleus, or the spinal trigeminal nucleus, and the FG spread to them in RBPH37, RBPH38, RBPH39, RBPH41, and RBPH42 does not account for the FG+ neurons in PVN and NTS in these cases.

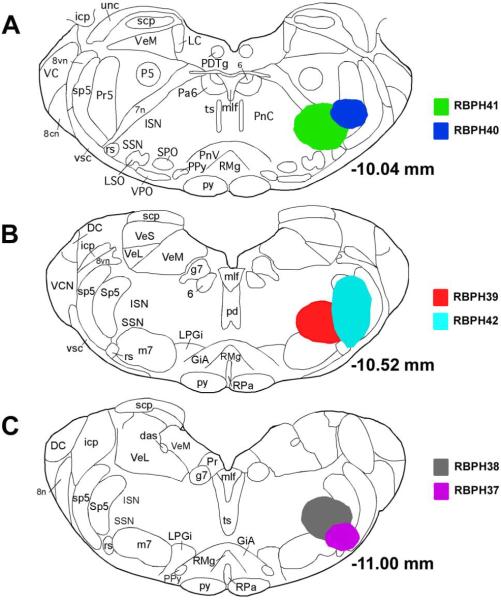

Fig. 2.

Illustration of Fluorogold injection sites targeting SSN by microsyringe pressure injection for six cases (RBPH37–RBPH42). Image A shows the cores of the Fluorogold injection sites for RBPH41 and RBPH40. In RBPH41, the injection site is centered on SSN, while for RBPH40 it was more rostral and lateral to that in RBPH41. Image B shows the cores of the Fluorogold injection sites for RBPH39 and RBPH42. Image C shows the cores of the Fluorogold injection sites for RBPH38 and RBPH37. The location and spread of the injection sites in RBPH41, RBPH39, and RBPH38 are very similar. The injection sites and resulting retrograde labeling for these cases, plus five control pressure injection cases for SSN and six iontophoretic injection cases for SSN, are also described in Table 1.

Fig. 3.

Images of Fluorogold - labeled neurons from a rat that had survived 6 days after pressure injection of Fluorogold into the right SSN (RBPH41), with the labeled neurons detected by DAB peroxidase-antiperoxidase immunohistochemistry. All images are of coronal sections. Image A shows the Fluorogold injection site into the right superior salivatory nucleus (SSN). Image B presents a low power view through the caudal hypothalamus on the right side of the brain, showing a scattering of FG+ neurons on that side in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). Image C shows a high power view of the PVN presented in image B, in which the labeled neurons can be seen more clearly. Image D and E show low power views of FG+ neurons at two levels of the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) near the obex. FG+ neurons are scattered throughout NTS at these levels. Image F shows a high power view of the NTS presented in image E. The scale bar in B also provides the magnification for D and E. The scale bar in C also provides the magnification for F.

2.2.2. BDA3K pressure injection into SSN

Fluorogold is a very avid retrograde tracer, and even seemingly well-confined injections may yield retrograde labeling due to spread to nuclei adjacent to the region of interest. This problem is especially acute for a complex brain region such as the level of the SSN. Therefore, we carried out a series of studies using a less avid retrograde tracer, namely BDA3K. Five rats received BDA3k pressure injections targeting SSN, while eight received BDA3K targeting SSN by iontophoresis to make small confined injections (Table 1). In two of the five rats with BDA3K pressure injection targeting SSN (RBP64 and RBP65), the injection site included central SSN, with slight spread to the sensory trigeminal nuclei (principle trigeminal nucleus and spinal trigeminal nucleus) and facial motor nucleus. The results were as observed following FG injection into SSN - retrogradely labeled BDA3K+ neurons were observed in the dorsal and lateral parvocellular divisions of ipsilateral PVN, and in ipsilateral NTS at and just rostral to the obex. By contrast, after a more lateral injection site including lateral SSN, sensory trigeminal nuclei and facial motor nucleus (RBP60), only a few BDA3K+ neurons were found in ipsilateral NTS and none in PVN. In cases in which the BDA3K pressure injection site included the spinal trigeminal nucleus but not SSN (RBP56 and RBP63), no BDA3K+ neurons were found in PVN and NTS. Thus, the pressure injection BDA3K cases indicate that PVN and NTS project to choroidal SSN, but not to the spinal trigeminal nuclei. Also the BDA3K spread to principle trigeminal nucleus as seen in RBP60 did not appear to contribute to the labeled neurons found in ipsilateral NTS, as FG spread to this region did not demonstrate labeled neurons in NTS (RBPH40).

2.2.3. BDA3K iontophoretic injection into SSN

In four of the rats with small iontophoretic injections (RBP46, RBP47, RBP53 and RBP55), the BDA3K injection site included SSN, with no or minor spread to the sensory trigeminal nuclei (Table 1). The one case with an injection confined to SSN (RBP46) yielded BDA3K+ neurons in ipsilateral posterior, dorsal and lateral PVN, and in NTS at or just rostral to the obex. In the other three cases, BDA3K+ neurons were consistently observed in ipsilateral NTS, but only one of three had BDA3K+ neurons in PVN (RBP47). These results suggest that the NTS input to choroidal SSN is more substantial than the PVN input. In four other rats with iontophoretic injection (RBP40, RBP42, RBP43 and RBP45), the BDA injection site missed SSN, and instead included the spinal trigeminal nucleus, facial nerve root, and/or intermediate reticular nucleus (IRt). No BDA3K+ cells were observed in PVN in any of these four cases (Table 1). These SSN-miss cases therefore show that retrogradely labeled neurons in PVN in our SSN cases did not occur due to iontophoretic injection spread to the spinal trigeminal nucleus or IRt. For NTS, a few BDA3K+ neurons were found in ipsilateral NTS in one rat (RBP45), possibly due to injection site spread to IRt, but not in the other three control cases. The overall data from our FG and BDA3K retrograde labeling studies are consistent with the notion that PVN and NTS neurons project directly to SSN.

2.3. Anterograde BDA10K labeling of PVN input to prechoroidal SSN

Our BDA3k retrograde labeling studies could not, by themselves, however, establish that the PVN and NTS projections to SSN terminate directly on the choroidal-control preganglionic neurons of SSN. To establish this, we used anterograde BDA10K labeling from PVN or NTS, either by pressure injection or iontophoresis. The PVN data are presented in this section (Table 2), and the NTS (Table 3) in the next.

Table 2.

Summary of Cases Involving Anterograde Pathway Tracing from PVN to SSN Using BDA10K

| Rat ID | Injection Method | Injection Site | Location of Anterograde Labeling within SSN and Its Vicinity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of PVN Injected | Region of Spread beyond PVN | Ipsilat SSN | Contralat SSN | Ipsilat A5 | Contralat A5 | Ipsilat ISN | Contralat ISN | ||

| RBP39 | Iontophoresis | PVN, complete A–P, medial 1/2 | Slight MPO, medial to AH | ++++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | - | - |

| RBP38 | Iontophoresis | PVN, complete A–P, medial 1/2 | Slight ZI, Re | ++++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | - | - |

| RBP26 | Iontophoresis | None | Left LH | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP27,29,30 | Iontophoresis | None | AH, MPO | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP28 | Iontophoresis | None | Left LH | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP31 | Iontophoresis | None | DH | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP32 | Iontophoresis | None | AH, LA, optic chiasm | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP33 | Iontophoresis | None | MPO; near PVN | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP34 | Iontophoresis | None | Re | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP35 | Iontophoresis | None | ZI & VM; lateral to PVN | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP36 | Iontophoresis | None | SCN | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP25 | Pressure | PVN, complete A–P, medial 2/3 | AH, VMH, DH, Re | ++++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | + |

| RBP10 | Pressure | Post A–P PVN, dorsal slightly | Medial thalamus | ++ | + | ++ | - | + | - |

| RBP22 | Pressure | Ant & Mid A–P PVN, medial 2/3 | DH, septum, MPO, medial thalamus | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| RBP23 | Pressure | Ant & Mid A–P PVN | MPO, BST | ++ | + | + | + | - | - |

| RBP17 | Pressure | Ant & Mid A–P PVN, dorsolat | Medial thalamus, PT, BST | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| RBP24 | Pressure | Mid A–P PVN, dorsal | Medial thalamus | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| RBP6 | Pressure | None | BST | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP13 | Pressure | None | AVPe, MPO | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP16 | Pressure | None | BST, ZI, medial thalamus | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP18 | Pressure | None | SON, LPO, HDB, LH, septum | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP19 | Pressure | None | Septum, VDB, MPO, SON, LH | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RBP20 | Pressure | None | LH, PT, PVA | - | - | - | - | - | - |

no anterogradely labeled fibers

few anterogradely labeled fibers

some anterogradely labeled fibers

many number of anterogradely labeled fibers

extensive anterogradely labeled fibers

Table 3.

Summary of Cases Involving Anterograde Pathway Tracing from NTS to SSN Using BDA10K

| Rat ID | Injection Method | Injection Site | Location of Anterograde Labeling within SSN and Its Vicinity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of NTS Injected | Region of Spread beyond NTS | Ipsilat SSN | Contralat SSN | Ipsilat A5 | Contralat A5 | Ipsilat ISN | Contralat ISN | ||

| RBP95 | Iontophoresis | NTS Entire | Slight dorsal IRt | ++++ | + | +++ | + | ++++ | + |

| RBP94 | Iontophoresis | NTS Entire | Slight dorsal IRt | ++++ | + | +++ | + | ++++ | + |

| RBP83 | Iontophoresis | Mid A–P NTS midventral | Dorsal IRt | ++++ | + | ++ | + | ++++ | +++ |

| RBP91 | Iontophoresis | Mid A–P NTS medial | None | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| RBP92 | Iontophoresis | Mid A–P NTS medioventral | Slight IRt | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| RBP89 | Iontophoresis | None | Lat hypogloss, dorsomed IRt | + | + | + | + | ++ | + |

| RBP72 | Iontophoresis | None | Cu | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| RBP81 | Iontophoresis | None | MVe, Cu | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| RBP88 | Iontophoresis | None | C3, hypogloss | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| RBP90 | Iontophoresis | None | Hypogloss | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| RBP75 | Pressure | Mid A–P NTS | Dorsal IRt | ++++ | + | ++ | + | ++++ | + |

| RBP77 | Pressure | Mid A–P NTS lateral | IRt, Cu, RVLM | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | +++ |

no anterogradely labeled fibers

few anterogradely labeled fibers

some anterogradely labeled fibers

many number of anterogradely labeled fibers

extensive anterogradely labeled fibers

2.3.1. BDA10K iontophoretic injection into PVN

Thirteen rats received iontophoresis of BDA10K into PVN (Table 2). The injection sites for twelve rats are illustrated in Figure 4A–D. The injection site of RBP27 is not illustrated as it is nearly the same as the injection sites for RBP29 and RBP30 (Table 2). Two cases (RBP39 and RBP38) exhibited relatively clean hits of entire the anterior to posterior medial PVN (Table 2). In both cases, many anterogradely labeled terminals were observed within SSN on both sides, with more fibers ipsilaterally. These terminals appeared to cluster in the region of the prechoroidal SSN. Images from RBP39 are presented in Figure 5, including the injection site (Fig. 5A). To better establish the relationship of the BDA10K+ terminals to the SSN neurons controlling the choroid, pairs of adjacent sections were ABC-labeled for BDA10K and immunolabeled for NOS (Fig. 5C&D), the latter of which we previously showed is enriched in the prechoroidal SSN neurons (Cuthbertson et al., 2003). We found that the location of the PVN afferents (Fig. 5D) and the location of the NOS+ neurons in SSN (Fig. 5B&C) were largely coincident. To further confirm this overlap, we double-labeled sections through SSN using two-color DAB, so that we could observe the relationship of the PVN afferent fibers to the NOS+ prechoroidal SSN neurons. We observed that black BDA10K+ afferents from PVN were distributed among the brown NOS+ neurons of SSN (Fig. 5E&F). In some instances, the PVN afferents were observed to be juxtaposed to NOS+ perikarya or dendrites within SSN (Fig. 5F).

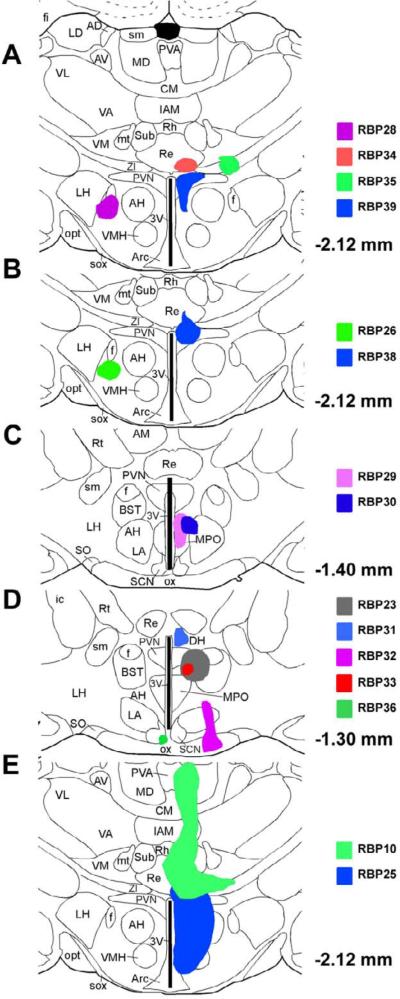

Fig. 4.

Illustration of cases in which PVN was targeted by iontophoresis or microsyringe pressure. Image A shows the injection site of a successful case RBP39 and those of three control cases (RBP28, RBP34, and RBP35). Image B shows the injection site of another successful case RBP38 and that of one control case RBP26. Image C shows the injection sites of two control cases, RBP29 and RBP30, at a more rostral level. Image D shows the injection sites of five control cases. Of the five control cases, RBP23 was a pressure injection case, while the remaining four were iontophoretic cases. Image E shows the injection sites for two cases with pressure injection. The injection sites and resulting anterograde labeling for these cases, and additional cases with injections targeting PVN, are also described in Table 2.

Fig. 5.

Images of BDA10K+ terminals from a rat that had survived 13 days after an iontophoretic delivery of BDA10K into the right PVN (RBP39), with the labeling detected by the ABC procedure with nickel intensified DAB. All images are of coronal sections. Image A shows the BDA10K injection site into the right PVN. Image B presents a camera lucida drawing of the brain stem at the level of the facial motor nucleus (7) and SSN. The dots represent NOS+ neurons. Images C and D show SSN in adjacent sections in which prechoroidal SSN neurons have been immunostained for NOS (C) and BDA10K+ terminals from PVN neurons visualized by the ABC method (D), respectively. Note that the location of NOS+ neurons within SSN overlaps with the location of BDA10K+ terminals from PVN neurons. Image E shows a high-power view of a section with two-color DAB double labeling to highlight the overlap between NOS+ neurons (visualized by a brown DAB reaction) and BDA10K+ terminals (visualized by a black nickel intensified DAB reaction). Image F is an enlargement of part of image E to show more clearly that BDA10K+ terminals are juxtaposed to NOS+ neurons. The scale bar in C provides the magnification for C and D.

Although the injection site following iontophoresis (diameter < 1mm) was very small, BDA10K spread to areas adjacent to PVN could not be avoided (Table 2). The spillover areas observed in RBP39 involved the medial preoptic nucleus (MPO) and the small area medial to anterior hypothalamus (AH). The injection site spread outside of PVN observed in RBP38 included nucleus reuniens (Re) and zona incerta (ZI). Eleven rats with BDA10K injected by iontophoresis into cell groups surrounding, but not including, PVN served as controls (Fig. 4A–D and Table 2). In none of these control rats were BDA10K+ fibers found in SSN. The injection sites in some rats (RBP26, RBP27, RBP28, RBP32, RBP33 and RBP36) included structures ventral to PVN such as lateral hypothalamus (LH), AH, MPO, and suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), and in other rats (RBP29 and RBP30) structures rostral to PVN such as MPO and AH. The absence of BDA10K fibers in SSN from these cases supported the notion that the terminals observed in RBP39 were from PVN, but not from MPO or AH or their vicinity. In yet additional rats (RBP31 and RBP34), the BDA10K injection site involved structures dorsal to PVN such as Re and dorsomedial hypothalamus (DH), and in one rat (RBP35) structures lateral to PVN such as ZI and ventromedial thalamus (VM). The absence of BDA10K fibers in SSN from these cases supported the notion that the terminals observed in RBP38 were from PVN, but not from Re or ZI or their vicinity.

2.3.2. BDA10K pressure injection into PVN

Initially, we also tried pressure injection of BDA10K (0.1–0.2 μl) into PVN on twelve rats. The results were consistent with the findings from iontophoretic injection presented in the preceding section. The pressure injection with microsyringe yielded a larger injection site (diameter > 3 mm), and consequently more spillover outside PVN (Table 2). In the case of RBP25, the injection site was located mainly in right PVN with spillover ventrally (Fig. 4E). Many anterogradely labeled fibers were observed within SSN bilaterally, with more intensely labeled fibers found in the ipsilateral SSN (right side). Five other rats (RBP10, RBP17, RBP22, RBP23, and RBP24) were considered as partially successful cases, since the injection site, while not centered on right PVN, did include it. Anterogradely labeled fibers were more common in SSN ipsilaterally for three of these cases, RBP10, RBP22 and RBP23, than in RBP17 and RBP24. In RBP10 (Fig. 4E), the BDA10K injection site included a very small part of dorsolateral PVN, while the major injection site was in medial thalamus. In RBP23, the injection site was more anterior (Fig. 4D), and similar injections sites were observed in RBP22 and RBP17. Six cases with pressure injection of BDA10K served as control cases (RBP6, RBP13, RBP16, RBP18, RBP19, and RBP20), in which the injection sites did not include PVN. No anterograde labeling was seen in SSN in any of these cases (Table 2). These six control cases were valuable as they suggested that the areas surrounding PVN do not project directly to SSN. These control results were consistent with the iontophoretic findings, yet more informative, as the injection sites were bigger.

In summary, the findings from our anterograde pathway tracing study with BDA10K injection into PVN, either by iontophoresis or pressure injection, strongly supported the notion that PVN neurons, especially those located dorsolaterally and posteriorly, project directly to prechoroidal SSN neurons.

2.4. Anterograde BDA10K labeling of NTS input to prechoroidal SSN

Ten rats received iontophoretic injections of BDA10K targeting NTS, while two received pressure injections targeting NTS. These are discussed separately below (Table 3).

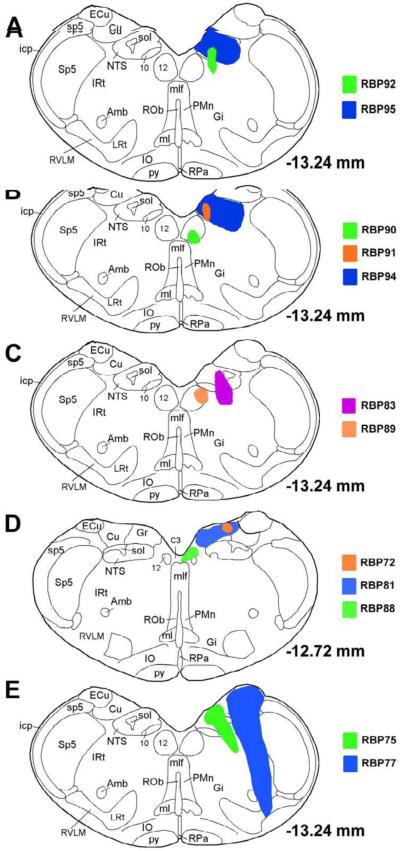

2.4.1. BDA10K iontophoretic injection into NTS

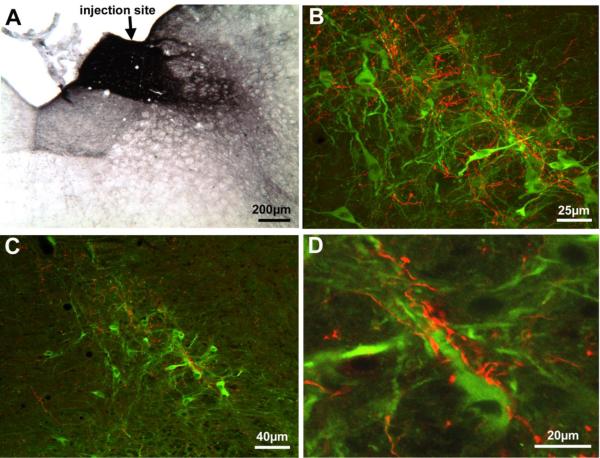

The injection sites for the iontophoretic cases are illustrated in Figure 6A–D. In two of these rats, the injections were confined to the right NTS, with small spillover to dorsal IRt (RBP95 and RBP94). In both, anterogradely labeled fibers were observed in the ipsilateral SSN and within the region dorsal to the SSN. To establish the relationship of the terminals within SSN to SSN neurons controlling the choroid, we used immunofluorescence double-labeling to simultaneously visualize both the BDA10K+ NTS input and NOS+ prechoroidal SSN neurons in the same sections from the two cases with the BDA10K injection largely confined to NTS (Fig. 6A&B). In Figure 7, images from RBP95 are presented, including the injection site and the confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) images of the double-labeling. The CLSM images confirmed the co-mingling of the NTS afferents and NOS+ neurons within the SSN (Fig. 7B–D). Moreover, in many instances BDA10K+ terminals were observed immediately adjacent to the NOS+ soma and dendrites of SSN neurons (Fig. 7D). The BDA10K+ terminals were unlikely to come from the spillover into dorsal IRt, since in our PRV transneuronal labeling studies we did not observed PRV+ neurons in dorsal IRt (Fig. 1).

Fig. 6.

Illustration of central injection sites for the BDA10K injection cases targeting NTS by iontophoresis or microsyringe. Image A shows the injection site of a successful case (RBP95) and that of a control case (RBP92). Image B shows the injection site of another successful case (RBP94) and those of two control cases. Image C shows the injection sites of one partially successful case (RBP83) and a control case (RBP30). Image D shows the injection sites for three control cases at a more rostral level. Image E show the injection sites for two cases with pressure injection. The injection sites and resulting anterograde labeling for these cases are also described in Table 3.

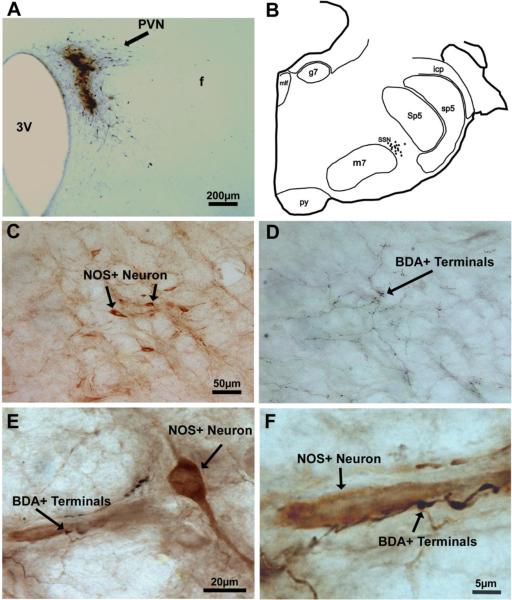

Fig. 7.

Images of BDA10K+ terminals from a rat that survived 11 days after an iontophoretic injection of BDA10K into the right NTS (RBP95). All images are of coronal sections. Image A shows the BDA10K injection site in the right NTS at the level of the obex. Image B shows an intermediate magnification CLSM image of NOS+ neurons (green) and BDA10K+ terminals (red) at the level of the facial somatomotor nucleus and SSN, showing the extensive overlap of NTS terminals with the NOS+ neurons of prechoroidal SSN. Image C shows a low-power view of NOS+ neurons and BDA10K+ fibers and boutons within SSN by using a rendered z-stack obtained by CLSM. Densely distributed BDA10K+ fibers are juxtaposed to the NOS+ neurons. Image D is high-power view centering on one of the NOS+ neurons shown in C. Note that many BDA10K+ boutons can be seen surrounding the dendrites and perikarya of this NOS+ neuron, presumably forming direct synaptic contacts.

Based on iontophoretic BDA10K injections into different parts of NTS, our results suggest that input to prechoroidal SSN appears to arise from lateral NTS at and rostral to the obex. For example in two cases (RBP91 & RBP92), the injection sites were confined to medial NTS at the obex. Anterogradely labeled fibers were not found in SSN in either case. By contrast, when the BDA10K injection site included lateral NTS at the obex level, as in RBP94 and RBP95 (noted above) and RBP83, anterogradely labeled fibers were abundant in prechoroidal SSN ipsilaterally. In five other rats (RBP72, RBP81, RBP88, RBP89 and RBP90), the iontophoretic injections did not include NTS but did include neuronal groups around NTS (Table 3). No anterogradely labeled fibers were found in SSN in any of these five cases.

2.4.2. BDA10K pressure injection into NTS

Two rats received BDA10K pressure injections via microsyringe targeting NTS. The injection in one case (RBP75) was centered on NTS, and in the second (RBP77) included lateral NTS. Both RBP75 and RBP77 possessed densely packed fine BDA10K+ fibers in SSN and its surrounding area, including A5, ISN, PBL, the vestibular nucleus, and the principal trigeminal nucleus. Scattered thick labeled fibers were also seen among the fine BDA10K+ fibers. These results are consistent with our iontophoretic studies.

In summary, our anterograde labeling studies with BDA10K injection into NTS either by iontophoresis or pressure strongly support the notion that NTS neurons, especially those located dorsolaterally at or rostral to obex, project directly and heavily to prechoroidal SSN neurons.

3. DISCUSSION

The ventral part of the SSN contains the preganglionic neurons projecting to the PPG via the greater petrosal nerve (Contreras et al., 1980; Jansen et al., 1992; Ng et al., 1994; Nicholson and Severin, 1981; Spencer et al., 1990; Tóth et al., 1999). The PPG itself, however, innervates diverse cranial targets, including the lacrimal gland, the Meibomian glands, the orbital conjunctiva, choroidal blood vessels, the cerebral vasculature, and the nasal and palatal mucosa (Nakai et al., 1993; Ruskell, 1965; Ruskell, 1971b; Schrödl et al., 2006; Ten Tusscher et al., 1990; Uddman et al., 1980b; van der Werf et al., 1996). Prior studies using PRV injected into different peripheral PPG targets have suggested that the SSN populations responsible for innervation of the different PPG targets show overlapping, but somewhat segregated, distributions. For example, SSN neurons controlling lacrimal gland are centered slightly caudal to those responsible for Meibomian gland control (LeDoux et al., 2001; Tóth et al., 1999). A prior study of ours (Cuthbertson et al., 2003) indicated that preganglionic neurons controlling PPG choroidal neurons in rat reside within ventromedial SSN, and that NOS is a marker for prechoroidal SSN neurons. The possibility remains, nonetheless, that choroidal preganglionic SSN neurons may control more than one of the target structures of the PPG. For example, given the similar metabolic and regulatory needs of the brain and eye (Bill, 1984; Bill, 1985), the same SSN neurons may mediate vasodilation of brain and choroidal vessels.

Prior studies have shown that the PPG neurons innervating the choroid contain NOS, VIP and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) (Cuthbertson et al., 2003; Stone et al., 1987; Yamamoto et al., 1993). The same PPG neurons innervating the choroid or additional PPG neurons may innervate orbital vessels feeding into the choroid and thereby exert a further influence on ChBF (Stone et al., 1987). The presence of prechoroidal neurons in the SSN is consistent with prior studies showing that facial nerve or SSN activation yields choroidal vasodilation, which appears to be mediated mainly by NOS and VIP released from PPG terminals in the choroid (Bill and Sperber, 1990; Steinle et al., 2000). It is important to note that, in addition to the parasympathetic vasodilatory influence on the choroid mediated by the PPG, the choroid also is regulated by vasodilatory sensory fibers from the ophthalmic nerve and vasoconstrictory sympathetic fibers from the superior cervical ganglion (Bill, 1984; Bill, 1985; Bill, 1991; Guglielmone and Cantino, 1982; Kirby et al., 1978; Stone et al., 1987).

The higher order labeling obtained here with PRV provides insight into the central circuitry and mechanisms underlying control of ChBF. In particular, higher order labeling was observed in dorsolateral posterior PVN and in caudolateral NTS at the level of the obex in cases with PRV injections well confined to the choroid. Consistent with our findings, Spencer et al. observed PRV+ neurons in PVN and NTS after direct injection of virus into the PPG (Spencer et al., 1990). The higher order labeling in NTS and PVN following short survival was of interest, since it suggested both project directly to choroidal neurons of SSN. Prior studies have, in fact, shown that the PVN and NTS are sources of input to the SSN (Agassandian et al., 2002; Hosoya et al., 1984; Hosoya et al., 1990). We confirmed that the subdivisions of the PVN and NTS containing PRV+ neurons after intrachoroidal PRV injections could be retrogradely labeled from SSN by Fluorogold and BDA3K. Thus, the dorsolateral caudal PVN and the caudolateral dorsal NTS at the level of the obex project to the SSN region that contains the choroidal preganglionic neurons. Given that SSN neurons possess glutamate receptors, and SSN has been shown to receive central glutamatergic inputs, it is likely the PVN and NTS inputs are excitatory (Lin et al., 2003).

The PVN region of the diencephalon is known to be responsive to systemic blood pressure (BP) changes, and may exert a vasodilatory influence on cerebral blood flow (Badoer and Merolli, 1998; Godino et al., 2005; Guyenet, 2006; Krukoff et al., 1997; Spencer et al., 1990). The caudolateral part of the NTS projecting to the SSN is known to receive aortic baroreceptor input via the vagus nerve and respond to systemic BP fluctuation (Ciriello, 1983; Guyenet, 2006; Rogers et al., 1993). The NTS also exerts a vasodilatory influence on cerebral blood flow (Agassandian et al., 2003; Nakai and Ogino, 1984). Additionally, the NTS projects directly and polysynaptically via the PBL to the PVN (Calarescu et al., 1984; Goldstein and Kopin, 1990). We have observed that activation of the PBL, NTS or the PVN increases ChBF in the ipsilateral eye (Fitzgerald et al., 2010). Since the present results show that both the PVN and the NTS project to the choroidal subdivision of SSN, it is likely that the ChBF increase occurring with their activation is in large part mediated by their input to SSN prechoroidal neurons. Given the apparent role of the PVN and the NTS in mediating peripheral vascular responses to fluctuations in systemic BP, this suggests the possibility that these inputs might regulate ChBF, in part, as a function of systemic BP. Prior studies have in fact shown that ChBF does compensate for fluctuations in systemic BP, and remain stable over a range of 35% above and below basal BP in rats, rabbits and pigeons (Kiel and Shepherd, 1992; Reiner et al., 2003; Reiner et al., 2010).

The similarities in systemic and ocular blood flow control circuitries reinforce the possibility that control of the two operates in parallel – with the systemic sympathetic control serving to restore BP in the face of any episodic declines in BP, and the parasympathetic control of ChBF serving to maintain high ChBF during bouts of low systemic BP. Consistent with the protective role that such parasympathetic ocular vascular control might play, severing PPG input to the cerebral vasculature intensifies the cerebral damage occurring with an ischemic event (Kano et al., 1991; Koketsu et al., 1992). Further studies are needed to determine if some of the same PVN and NTS neurons are involved in regulation of both cerebral blood flow and ChBF.

4. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

4.1. Subjects and approaches

Sixty-six adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (SD rats; 300g–500g; from Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were used (10 for PRV into choroid, 13 for BDA3K into SSN, 6 for Fluorogold into SSN, 25 for BDA10K into PVN, and 12 for BDA10K into NTS). All experiments were undertaken in compliance with the ARVO statement on the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and with NIH and institutional guidelines. This study focused on the projections of the PVN and NTS to the choroidal control neurons of SSN, using a two-step approach. In the first step, the participation of PVN and NTS in circuitry projecting to prechoroidal SSN was established by injections of the transneuronal retrograde tracer PRV into choroid. In the second step, we assessed whether PVN and NTS project directly to prechoroidal SSN neurons, using conventional retrograde and anterograde pathway tracing methods. In the retrograde tracer studies, BDA3K or FG was injected unilaterally into SSN to determine if PVN and NTS were among the nuclei projecting directly to SSN. The anterograde tracing studies involved injection of BDA10K into PVN or NTS, and examination of prechoroidal SSN for the presence of resulting anterogradely labeled BDA10K+ fibers in SSN in general and upon NOS+prechoroidal SSN neurons, in particular.

4.2. Pseudorabies virus transneuronal retrograde pathway tracing

To identify SSN neurons involved in the control of ChBF, a retrograde transneuronal tracer, the Bartha strain of pseudorabies virus (PRV), was injected into the right choroid. Viruses such as PRV are valuable for delineating central circuits since, unlike a conventional retrograde tracer, they are transported transneuronally (i.e. across synapses), and provide robust labeling in recipient neurons due to virus replication (LeDoux et al., 2001). PRV injections were performed with a Hamilton syringe with a 30-gauge needle, and rats receiving intrachoroidal injection of PRV had received prior bilateral resections of the superior cervical ganglia (SCG) to prevent retrograde transneuronal labeling along sympathetic circuitry (LeDoux et al., 2001). Since PRV does not typically show transganglionic transport via sensory ganglia (Jansen et al., 1992; LeDoux et al., 2001; Rotto-Percelay et al., 1992), there was no reason to transect the ophthalamic nerve to prevent transport of PRV to the brain via trigeminal circuitry. For the intrachoroidal injections, rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 0.1ml/100g of a ketamine/xylazine mixture (87/13 mg/kg), and the right superior-temporal choroid was injected with 0.5–2.0 μl of PRV (3×108 plaque forming units/ml or 1.1×109 plaque forming units/ml), as described previously (Cuthbertson et al., 2003). The animals were allowed to survive between 52 and 87.5 hours after virus injection. Brains from these rats were fixed by transcardial perfusion and the PRV was detected by immunolabeling. Figure 1 presents one illustrative case (R3-07, with a survival of 69 hrs) from the 10 rats that received intrachoroidal PRV. Schematics adapted from Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1994) were used. Some of these rats had been used to detect prechoroidal SSN neurons in a prior study (Cuthbertson et al., 2003).

One concern associated with this method is the extent of tracer spread beyond choroid after injection with microsyringe. It is very difficult to detect PRV itself within the choroidal injection site as the virus is taken up, and the virus at the injection site as a result undetectable after a few days of survival. Confinement of the injection site to choroid is revealed by the pattern of labeling within the brain, since spread to extraocular or periorbital facial muscles is revealed by labeling within brain in oculomotor, trochlear, abducens or facial motoneurons, while intravitreal spread is revealed by labeling in the nucleus of Edinger-Westphal of the oculomotor complex. Additionally, in a prior study we injected Fluorogold into choroid to label PPG neurons (Cuthbertson et al., 2003), and found that the intrachoroidal injections were largely restricted to the choroid. Any slight leakage into the musculature surrounding the temporal side of the eye did not yield labeling of motoneurons in brain, nor did spread to the Harderian gland occur and cause Fluorogold labeling in the PPG. Therefore, intrachoroidal PRV injections could be carried out without undetected confounding spread beyond the choroid.

4.3. Retrograde tracer injection into SSN

Fluorogold (FG, 10%, 0.03μl-0.05μl) was delivered into SSN by microsyringe in six rats (RBPH37–RBPH42). Pressure injections were performed using a 0.5μl syringe with 25-gauge needle (Hamilton, #86250). Rats were anesthetized by ketamine/xylazine, with supplemental doses during surgery to maintain anesthesia (as monitored by whisker movement). Body temperature was maintained at 37 C and the rats were positioned in a stereotaxic device. Based on the rat brain stereotaxic atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1994), the target coordinates of right SSN were 10.6 mm behind Bregma, 2.2 mm lateral to the midline, and 7.6 mm to 8.0 mm below the brain surface. Two injections of tracer separated by 0.2 mm (DV) were made in SSN via pressure to increase the chance of hitting target area. The animals with FG injections were allowed to survive 5–7 days.

We also used BDA3K to make more confined injections into SSN by pressure or iontophoresis. A solution of 10% BDA3K (Molecular Probes, BDA3000kD MW) was prepared with 0.1M sodium-citrate-HCl buffer (pH3). Injection of 0.06–0.1μl 10% BDA3K was made into the right SSN in five rats using the same pressure injection procedure as for Fluorogold. Eight additional rats received iontophoretic injections of BDA3K into the right SSN. Micropipettes for iontophoresis were pulled from glass tubing (World Precision Instrument, 1B150F-4) with a PE-2 microelectrode puller (Narashige), and micropipettes with a tip diameter of 50–100μm used for iontophoresis. Micropipettes were filled with 7–8 μl 10% BDA3K, and a platinum wire inserted. A Grass stimulator (Model S88) was used to deliver constant current pulses (+ current, 7s on, 7s off, 5μA, 20–60 min) via a stimulation isolation unit (Grass Instrument, PSIU-6) (Reiner et al., 2000). The animals with BDA3K injections were allowed to survive 10–14 days.

4.4. Anterograde tracer injection into PVN

Twelve rats received pressure injections of 0.1–0.2 μl of 5% BDA10K (Molecular Probes, BDA10,000 kD MW) diluted with 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer into the right PVN via a 0.5μl syringe with 25-gauge needle. Since the injection sites made by microsyringe pressure injection invariably spread beyond PVN, thirteen additional SD rats received smaller injections of 5% BDA10K into the right PVN via iontophoresis (+ current, 7 s on, 7 s off, 5 μA, 10–30 min). Stereotaxic methods were as noted above. The target coordinates for PVN were - 1.9 mm caudal to the Bregma, - 0.4 mm lateral to the midline, and - 7.3 mm to 7.6 mm from the brain surface (Paxinos and Watson, 1994). BDA10K was then injected at two sites separated by 0.1 – 0.2 mm dorsoventrally for both the pressure and iontophoretic injections. The animals with BDA10K injections in PVN were allowed to survive 10 to 14 days.

4.5. Anterograde tracer injection into NTS

Two rats received pressure injection of 0.06 μl of 5% BDA10K in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer into the right NTS via a 0.5 μl microsyringe with 25-gauge needle. Nine additional rats received iontophoretic injections of 15% BDA10K in 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer into the right NTS via a micropipette with a 20–50 μm tip diameter. The rats were anesthetized, placed in a stereotaxic device and the body temperature maintained at 37°C as described above. The coordinates for NTS (Paxinos and Watson, 1994) were - 13.6 mm behind Bregma, -1.1 lateral to Bregma, and 5.1–5.9 below the brain surface. Animals with BDA10K injection into NTS were allowed to survive 7 to 11 days.

4.6. Histological tissue preparation

As described previously (Cuthbertson et al., 2003), rats were anesthetized, and perfused transcardially with sodium phosphate buffered saline and 400 –500 ml 4% paraformaldehyde prepared in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer (pH7.4) with 0.1M lysine and 0.01M sodium periodate (PLP fixative). Brains were removed and cryoprotected at 4°C in 20% sucrose / 10% glycerol / 0.138% sodium azide in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer. Brains were then frozen, and coronal sections cut at 40 μm with a sliding microtome. The free-floating sections were stored at 4°C in a 0.02% sodium azide / 0.02% imidazole in 0.1 M PB until processed for detection of PRV, FG, BDA3K, or BDA10K, as described below.

4.7. Single-label immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical single-labeling was carried out as described previously to detect the PRV and FG tracers, or the NOS+ neurons within SSN (Cuthbertson et al., 2003; LeDoux et al., 2001). For PRV detection, the primary antibody was a highly sensitive and specific goat anti-PRV (LeDoux et al., 2001; Cuthbertson et al., 2003), diluted 1:15,000–1:100,000 with 0.1 M phosphate buffer / 0.3% Triton X-100 / 0.001% sodium azide (PB/Tx/Az) + 5% normal horse serum. The anti-PRV antibody specificity was demonstrated by viral immunostaining in culture and in virus-infected brain. In the case of in vitro tests of specificity, PRV was incubated with PK15 (porcine kidney) cells at 4°C for 1 hour, to produce monolayer cultures of PRV-infected PK15 cells. The cultures were subsequently washed 3 times with PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde. A 1:10,000 dilution of antibody followed by 1:10,000 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-goat antibody resulted in strong staining of virus particles on the cell surface. For in vivo tests of antibody specificity, brain tissue from normal uninfected rats or from rats with intrachoroidal or intra-Meibomian gland injection of PRV >60 hours previously was used. Robust staining of virus-infected neurons with post-immunization goat anti-PRV antiserum was observed at concentrations ranging from 1:10,000 to 1:100,000. Uninfected brains did not stain with the anti-PRV antibody at these concentrations (LeDoux et al., 2001; Cuthbertson et al., 2003). Moreover, no immunostaining was observed in virus-infected brain tissue treated with pre-immune serum.

For FG detection, the primary antibody was rabbit anti-FG (from Fluorochrome, LLC), diluted at 1:2000 with the same diluent). This antibody has been widely used for detecting FG (Hayward and Von Reitzenstein, 2002; Kingsbury et al., 2005), and it produces no labeling in brains that have not been injected with Fluorogold.

For NOS, a rabbit anti-NOS1 (neuronal NOS, R-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), diluted 1:2000 to 1:4000 with the same diluent, was used. The antibody specificity has been verified by Western blot analysis by the manufacturer, and the distribution of perikaryal NOS staining it produces in rodents matches the known distribution of NOS+ perikarya in rodent brain as seen in the Allen Brain Atlas (http://mouse.brain-map.org/welcome.do).

Our immunolabeling procedures have been described in detail elsewhere (Reiner et al., 1991; Cuthbertson et al., 2003). In brief, sections were incubated in primary antibody overnight at room temperature. Sections for PRV detection were beforehand pretreated with 0.5% H2O2 to quench endogeneous peroxidases, followed by 1% nonfat dry milk to reduce non-specific background. After primary antibody incubation, sections were rinsed and incubated in donkey antiserum against goat IgG in the case of PRV visualization, or donkey antiserum directed against rabbit IgG in the case of FG or neuronal NOS detection. The sections were subsequently rinsed and incubated in goat peroxidase-antiperoxidase (Gt PAP, diluted at 1:1000 with PB/Tx; goat PAP from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) or rabbit peroxidase-antiperoxidase (Rb PAP, diluted at 1:1000; rabbit PAP from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). The labeling was visualized using diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) in a 0.05M sodium cacodylate - 0.05M imidizole buffer (pH 7.2–7.4). The sections were then rinsed, mounted air-dried, dehydrated and coverslipped with Permount® (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The sections were examined with an Olympus BHS microscope with standard transmitted light or differential interference contrast optics.

4.8. ABC procedure to visualize BDA

Sections were rinsed, followed by pretreatment with 0.5% H2O2 and 0.3% Triton X-100 PB (PB/Tx) (Reiner et al., 2000). The sections were then rinsed and incubated in ABC solution preparing with the Vectastain ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). BDA3K or BDA10K was visualized as a black reaction product using nickel intensification of the chromagen, DAB (Sigma). The sections were then rinsed, mounted, air-dried, dehydrated, coverslipped, and examined with an Olympus BHS microscope.

4.9. Two-color DAB double-label immunohistochemistry

Our previous studies showed that prechoroidal SSN neurons largely correspond to NOS+ neurons of the SSN (Cuthbertson et al., 2003). This information was used to judge the location of BDA10K+ fibers from the PVN or NTS in relation to prechoroidal SSN neurons. Immunohistochemical two-color DAB double-labeling was used to visualize both the PVN or NTS inputs, and the NOS+ prechoroidal neurons of SSN. For these double-label studies, brain sections from rats with BDA10K injection into PVN or NTS were first labeled black by the ABC procedure using nickel-intensified DAB as described above. The tissue was then rinsed extensively, and incubated overnight in rabbit anti-NOS1 (neuronal NOS). Tissue was then sequentially incubated at room temperature for 1 hr in a donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody and rabbit PAP. The NOS immunolabeling was visualized with a brown DAB procedure. The sections were subsequently mounted, air-dried, dehydrated, and coverslipped. They were examined with a BHS Olympus microscope.

4.10. Fluorescent double-label immunohistochemistry

We also used immunofluorescence double labeling to visualize the relationship of BDA10K+ fibers originating from NTS to NOS+ prechoroidal SSN neurons. The sections were rinsed and incubated in rabbit anti-NOS1 (1:800) overnight. After rinsing, the tissue was incubated in donkey anti rabbit Alexa 488 (1:100; Molecular Probes) and streptavidin Alexa 594 (1:100; Molecular Probes) for 3 hrs. The sections were then mounted on gelatin-coated slides, air-dried, and coverslipped in glycerol phosphate buffer (9:1). Sections were viewed and images captured using a Nikon C1 confocal laser-scanning microscope. Single image planes as well as Z-stacks were captured for viewing, analysis and illustration.

Paraventricular hypothalamus innervates facial preganglionic neurons for choroidal blood flow

Solitary Nucleus innervates facial preganglionic neurons for choroidal blood flow

Parasympathetic control of choroidal blood flow is linked to control of systemic vasculature

Parasympathetic control of choroidal blood flow may be influenced by blood pressure signals

Parasympathetic control of choroidal blood flow may be influenced by blood salinity and volume

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Dr. Yunping Deng for valuable advice on technical matters, and Ting Wong, Marion Joni, Aminah Henderson, Phoungdinh Nguyen, Amanda Walters, Dr. Rebeca-Ann Weinstock, Dr. Raven Babcock, Amanda Valencia, Dr. Seth Jones, Julia Jones, Karen Hanks, and Christy Loggins for their excellent technical assistance. Supported by the University of Tennessee Neuroscience Institute (CL), Department of Ophthalmology unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (MECF) Benign Essential Blepharospasm Research Foundation Inc. (ML), NIH-EY-12232 (ML), NIH-EY-05298 (AR), and NIH/NEI-5P30EY013080 (D. Johnson).

Grant/Financial Support: Supported by the University of Tennessee Neuroscience Institute (CL), Department of Ophthalmology unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (MECF), Benign Essential Blepharospasm Research Foundation Inc. (ML), NIH-EY-12232 (ML), NIH-EY-05298 (AR), and NIH/NEI-5P30EY013080 (D. Johnson).

Abbreviations

- 6

abcucens nucleus

- 10

dorsal motor nucleuse of vagus

- 12

hypoglossal nucleus

- 3V

third ventricle

- 7n

facial nerve

- 8cn

cochlear root of 8n

- 8n

vestibulocochlear nerve

- 8vn

vestibular root of 8n

- A5

A5 noradrenaline cells

- Acs7

accessory facial nucleus

- AD

anterodorsal thalamic nucleus

- AH

anterior hypothalamus

- Amb

ambiguus nucleus

- AP

area postrema

- Arc

arcuate nucleus

- AV

anteroventral thalamic nucleus

- AVPe

anteroventral periventricular nucleus

- BAOT

bed nucleus of accessory olfactory tract

- BDA

biotinylated dextran amine

- BDA3K

biotinylated dextran amine 3000kD MW

- BDA10K

biotinylated dextran amine 10000 kD MW

- BLA

anterior part of basolateral amygdaloid nucleus

- BMA

anterior part of basomedial amygdaloid nucleus

- BP

blood pressure

- BST

bed nucleus of stria terminalis

- C3

C3 adrenaline cells

- CA3

field CA3 of hippocampus

- cc

corpus callosum

- Ce

central amygdaloid nucleus

- cg

cingulum

- ChAT

choline acetyltransferase

- ChBF

choroidal blood flow

- CLSM

confocal laser scanning microscope

- CM

central medial thalamic nucleus

- CPu

caudate putamen

- CxA

cortex-amygdala transition zone

- cu

cuneate fasciculus

- Cu

cuneate nucleus

- DAB

diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride

- das

dorsal acoustic stria

- DC

dorsal cochlear nucleus

- DH

dorsomedial hypothalamus

- DV

dorsoventrally

- ec

external capsule

- ECu

external cuneate nucleus

- En

endopiriform cortex

- f

fornix

- FG

Fluorogold

- fi

fimbria of hippocampus

- g7

genu of facial nerve

- Gi

gigantocellular reticular nucleus

- GiA

alpha part of gigantocellular reticular nucleus

- Gr

gracile nucleus

- HDB

nucleus of horizontal limb of diagonal band

- IAM

interanteromedial thalamic nucleus

- ic

internal capsule

- icp

inferior cerebellar peduncle

- IM

intercalated nucleus of amygdala

- IO

inferior olive

- ISN

inferior salivatory nucleus

- IRt

intermediate reticular nucleus

- LA

lateroanterior hypothalamus

- LC

locus coeruleus

- LD

laterodorsal thalamic nucleus

- LGP

lateral globus pallidus

- LH

lateral hypothalamus

- LPGi

lateral paragigantocellular nucleus

- LPO

lateral preoptic area

- LRt

lateral reticular nucleus

- LSO

lateral superior olive

- m7

facial nucleus

- MD

mediodorsal thalamic nucleus

- Me

medial amygdaloid nucleus

- ml

medial lemniscus

- mlf

medial longitudinal fasciculus

- MPO

medial preoptic nucleus

- mt

mammillothalamic tract

- MVe

medial vestibular nucleus

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- NTS

nucleus of solitary tract

- opt

optic tract

- ox

optic chiasm

- P5

peritrigeminal zone

- Pa6

paraabducens nucleus

- Pr5

principle trigeminal nucleus

- PAG

periaqueductal central gray

- PAP

peroxidase-antiperoxidase

- PBL

lateral parabrachial nucleus

- pd

predorsal bundle

- PDTg

posterodorsal tegmental nucleus

- Pir

piriform cortex

- PK15

porcine kidney cells

- PMn

paramedian raphe nucleus

- PnC

caudal pontine reticular nucleus

- PnV

ventral pontine reticular nucleus

- PPG

pterygopalatine ganglion

- PPy

parapyramidal nucleus

- Pr

prepositus nucleus

- PRV

pseudorabies virus

- PT

paratenial thalamic nucleus

- PVA

anterior part of paraventricular thalamic nucleus

- PVA

paraventricular thalamic nucleus

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus

- py

pyramid

- RAmb

retroambiguus nucleus

- Re

reunions

- Rh

rhomboid thalamic nucleus

- RMg

raphe magnus

- unc

uncinate fasciculus

- ROb

raphe obscurus nucleus

- RPa

raphe pallidus nucleus

- rs

rubrospinal tract

- Rt

reticular thalamic nucleus

- RVLM

rostroventral lateral Medulla

- SCG

superior cervical ganglion

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- scp

superior cerebellar peduncle

- suprachiasmatic nucleus

- SD

Sprague-Dawley

- sm

stria medullaris of thalamus

- sol

solitary tract

- SO

superior olive

- SON

supraoptic nucleus

- sox

supraoptic decussation

- Sp5

spinal trigeminal nucleus

- sp5

spinal trigeminal tract

- SPO

superior paraolivary nucleus

- SSN

superior salivatory nucleus

- st

stria terminalis

- Sub

submedius thalamic nucleus

- ts

tectospinal tract

- VA

ventral anterior thalamic nucleus

- VDB

nucleus of vertical limb of diagonal band

- VeCb

vestibulocerebellar nucleus

- VeL

lateral vestibular nucleus

- VeM

medial vestibular nucleus

- VeS

superior vestibular nucleus

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal polypeptide

- VL

ventrolateral thalamic nucleus

- VM

ventromedial thalamic nucleus

- VMH

ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus

- VPL

ventral posterolateral thalamic nucleus

- VPO

ventral paraolivary nucleus

- vsc

ventral spinocerebellar tract

- ZI

zona incerta

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CR: None

REFERENCES

- Agassandian K, Fazan VP, Adanina V, Talman WT. Direct projections from the cardiovascular nucleus tractus solitarii to pontine preganglionic parasympathetic neurons: a link to cerebrovascular regulation. J Comp Neurol. 2002;452:242–254. doi: 10.1002/cne.10372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agassandian K, Fazan VP, Margaryan N, Dragon DN, Riley J, Talman WT. A novel central pathway links arterial baroreceptors and pontine parasympathetic neurons in cerebrovascular control. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23:463–478. doi: 10.1023/A:1025059710382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alm P, Uvelius B, Ekstrom J, Holmqvist B, Larsson B, Andersson KE. Nitric oxide synthase-containing neurons in rat parasympathetic, sympathetic and sensory ganglia: a comparative study. Histochem J. 1995;27:819–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badoer E, Merolli J. Neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus that project to the rostral ventrolateral medulla are activated by haemorrhage. Brain Res. 1998;791:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill A. The circulation in the eye. In: Renkin EM, Michel CC, editors. The microcirculation. Handbook of Physiology, section 2, Vol. American Physiological Society; Bethesda, MD, USA: 1984. pp. 1001–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Bill A. Some aspects of the ocular circulation. Friedenwald lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26:410–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill A, Sperber GO. Control of retinal and choroidal blood flow. Eye (Lond) 1990;4(Pt 2):319–325. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill A. The 1990 Endre Balazs Lecture. Effects of some neuropeptides on the uvea. Exp Eye Res. 1991;53:3–11. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarescu FR, Ciriello J, Caverson MM, Cechetto DF, Krukoff TL. Functional neuroanatomy of ventral pathways controlling the circulation. In: Kochen TA, Guthrie CP, editors. Hypertension and the brain. Vol. Futura Publications; Mt. Kisco, New York: 1984. pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ciriello J. Brainstem projections of aortic baroreceptor afferent fibers in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1983;36:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras RJ, Gomez MM, Norgren R. Central origins of cranial nerve parasympathetic neurons in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1980;190:373–394. doi: 10.1002/cne.901900211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson S, White J, Fitzgerald ME, Shih YF, Reiner A. Distribution within the choroid of cholinergic nerve fibers from the ciliary ganglion in pigeons. Vision Res. 1996;36:775–786. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(95)00179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson S, Jackson B, Toledo C, Fitzgerald ME, Shih YF, Zagvazdin Y, Reiner A. Innervation of orbital and choroidal blood vessels by the pterygopalatine ganglion in pigeons. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:422–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson S, LeDoux MS, Jones S, Jones J, Zhou Q, Gong S, Ryan P, Reiner A. Localization of preganglionic neurons that innervate choroidal neurons of pterygopalatine ganglion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3713–3724. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald ME, Vana BA, Reiner A. Control of choroidal blood flow by the nucleus of Edinger-Westphal in pigeons: a laser Doppler study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990a;31:2483–2492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald ME, Vana BA, Reiner A. Evidence for retinal pathology following interruption of neural regulation of choroidal blood flow: Muller cells express GFAP following lesions of the nucleus of Edinger-Westphal in pigeons. Curr Eye Res. 1990b;9:583–598. doi: 10.3109/02713689008999598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald ME, Gamlin PD, Zagvazdin Y, Reiner A. Central neural circuits for the light-mediated reflexive control of choroidal blood flow in the pigeon eye: a laser Doppler study. Vis Neurosci. 1996;13:655–669. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800008555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald ME, Tolley E, Frase S, Zagvazdin Y, Miller RF, Hodos W, Reiner A. Functional and morphological assessment of age-related changes in the choroid and outer retina in pigeons. Vis Neurosci. 2001;18:299–317. doi: 10.1017/s0952523801182143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gai WP, Blessing WW. Human brainstem preganglionic parasympathetic neurons localized by markers for nitric oxide synthesis. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 4):1145–1152. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.4.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godino A, Giusti-Paiva A, Antunes-Rodrigues J, Vivas L. Neurochemical brain groups activated after an isotonic blood volume expansion in rats. Neuroscience. 2005;133:493–505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DS, Kopin IJ. The autonomic nervous system and catecholamines in normal blood pressure control and in hypertension. In: Laragh JH, Brenner BM, editors. Hypertension: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Vol. Raven Press Ltd; New York: 1990. pp. 711–747. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmone R, Cantino D. Autonomic innervation of the ocular choroid membrane in the chicken: a fluorescence-histochemical and electron-microscopic study. Cell Tissue Res. 1982;222:417–431. doi: 10.1007/BF00213222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG. The sympathetic control of blood pressure. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:335–346. doi: 10.1038/nrn1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward LF, Von Reitzenstein M. c-Fos expression in the midbrain periaqueductal gray after chemoreceptor and baroreceptor activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1975–1984. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00300.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodos W, Miller RF, Ghim MM, Fitzgerald ME, Toledo C, Reiner A. Visual acuity losses in pigeons with lesions of the nucleus of Edinger-Westphal that disrupt the adaptive regulation of choroidal blood flow. Vis Neurosci. 1998;15:273–287. doi: 10.1017/s0952523898152070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoya Y, Matsushita M, Sugiura Y. Hypothalamic descending afferents to cells of origin of the greater petrosal nerve in the rat, as revealed by a combination of retrograde HRP and anterograde autoradiographic techniques. Brain Res. 1984;290:141–145. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoya Y, Sugiura Y, Ito R, Kohno K. Descending projections from the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus to the A5 area, including the superior salivatory nucleus, in the rat. Exp Brain Res. 1990;82:513–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00228793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi H, Karita K. Parasympathetic-mediated reflex salivation and vasodilatation in the cat submandibular gland. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R747–753. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.3.R747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen AS, Ter Horst GJ, Mettenleiter TC, Loewy AD. CNS cell groups projecting to the submandibular parasympathetic preganglionic neurons in the rat: a retrograde transneuronal viral cell body labeling study. Brain Res. 1992;572:253–260. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90479-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson O, Lundberg JM. Ultrastructural localization of VIP-like immunoreactivity in large dense-core vesicles of `cholinergic-type' nerve terminals in cat exocrine glands. Neuroscience. 1981;6:847–862. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(81)90167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M, Moskowitz MA, Yokota M. Parasympathetic denervation of rat pial vessels significantly increases infarction volume following middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:628–637. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel JW, Shepherd AP. Autoregulation of choroidal blood flow in the rabbit. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:2399–2410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury MA, Friedman B, McConnell MJ, Rehen SK, Yang AH, Kaushal D, Chun J. Aneuploid neurons are functionally active and integrated into brain circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6143–6147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408171102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby ML, Diab IM, Mattio TG. Development of adrenergic innervation of the iris and fluorescent ganglion cells in the choroid of the chick eye. Anat Rec. 1978;191:311–319. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091910304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koketsu N, Moskowitz MA, Kontos HA, Yokota M, Shimizu T. Chronic parasympathetic sectioning decreases regional cerebral blood flow during hemorrhagic hypotension and increases infarct size after middle cerebral artery occlusion in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:613–620. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krukoff TL, Mactavish D, Jhamandas JH. Activation by hypotension of neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus that project to the brainstem. J Comp Neurol. 1997;385:285–296. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970825)385:2<285::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux MS, Zhou Q, Murphy RB, Greene ML, Ryan P. Parasympathetic innervation of the meibomian glands in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2434–2441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Agassandian K, Fujiyama F, Kaneko T, Talman WT. Evidence for a glutamatergic input to pontine preganglionic neurons of the superior salivatory nucleus in rat. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;25:261–268. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(03)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg JM, Anggard A, Emson P, Fahrenkrug J, Hokfelt T. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and cholinergic mechanisms in cat nasal mucosa: studies on choline acetyltransferase and release of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:5255–5259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg JM, Anggard A, Fahrenkrug J. Complementary role of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and acetylcholine for cat submandibular gland blood flow and secretion. Acta Physiol Scand. 1982;114:329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1982.tb06992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai M, Ogino K. The relevance of cardio-pulmonary-vascular reflex to regulation of the brain vessels. Jpn J Physiol. 1984;34:193–197. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.34.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai M, Tamaki K, Ogata J, Matsui Y, Maeda M. Parasympathetic cerebrovasodilator center of the facial nerve. Circ Res. 1993;72:470–475. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng YK, Wong WC, Ling EA. A light and electron microscopical localisation of the superior salivatory nucleus of the rat. J Hirnforsch. 1994;35:39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson JE, Severin CM. The superior and inferior salivatory nuclei in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1981;21:149–154. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Vol. Academic Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Potts AM. An hypothesis on macular disease. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1966;70:1058–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Karten HJ, Gamlin PDR, Erichsen JT. Parasympathetic ocular control: Functional subdivisions and circuitry of the avian nucleus of Edinger-Westphal. Trends in Neuroscience. 1983;6:140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Veenman CL, Medina L, Jiao Y, Del Mar N, Honig MG. Pathway tracing using biotinylated dextran amines. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;103:23–37. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Zagvazdin Y, Fitzgerald ME. Choroidal blood flow in pigeons compensates for decreases in arterial blood pressure. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Li C, Del Mar N, Fitzgerald ME. Choroidal blood flow compensation in rats for arterial blood pressure decreases is neuronal nitric oxide-dependent but compensation for arterial blood pressure increases is not. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90:734–741. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RF, Paton JF, Schwaber JS. NTS neuronal responses to arterial pressure and pressure changes in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R1355–1368. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.6.R1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotto-Percelay DM, Wheeler JG, Osorio FA, Platt KB, Loewy AD. Transneuronal labeling of spinal interneurons and sympathetic preganglionic neurons after pseudorabies virus injections in the rat medial gastrocnemius muscle. Brain Res. 1992;574:291–306. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90829-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruskell GL. The orbital distribution of the sphenopalatine ganglion in the rabbit. In: Rohen JW, editor. The structure of the eye. Vol. Schattauer-Verlag; Stuttgart: 1965. pp. 323–339. [Google Scholar]

- Ruskell GL. Facial parasympathetic innervation of the choroidal blood vessels in monkeys. Exp Eye Res. 1971a;12:166–172. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(71)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruskell GL. The distribution of autonomic post-ganglionic nerve fibres to the lacrimal gland in monkeys. J Anat. 1971b;109:229–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödl F, Brehmer A, Neuhuber WL, Nickla D. The autonomic facial nerve pathway in birds: a tracing study in chickens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3225–3233. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih YF, Fitzgerald ME, Reiner A. Effect of choroidal and ciliary nerve transection on choroidal blood flow, retinal health, and ocular enlargement. Vis Neurosci. 1993;10:969–979. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800006180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih YF, Fitzgerald ME, Reiner A. The effects of choroidal or ciliary nerve transection on myopic eye growth induced by goggles. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3691–3701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SE, Sawyer WB, Wada H, Platt KB, Loewy AD. CNS projections to the pterygopalatine parasympathetic preganglionic neurons in the rat: a retrograde transneuronal viral cell body labeling study. Brain Res. 1990;534:149–169. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90125-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinle JJ, Krizsan-Agbas D, Smith PG. Regional regulation of choroidal blood flow by autonomic innervation in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R202–209. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.1.R202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]