Abstract

Background

Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura (SFTP) represents a clinical entity rarely encountered, especially in giant forms. Complete surgical resection for giant tumor of pleura is a challenge. The aim of this article is to present five new cases of giant SFTP, and to discuss their clinical characteristics and the treatment strategy of such neoplasms.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of the clinical records of five patients who underwent surgery for a huge SFTP (>18 cm in diameter) between 2007 and 2009.

Results

Four patients were symptomatic. All five patients underwent angiography and embolization of the tumor-supplying vessels within 24 h of surgery. All giant tumors were removed completely by extended postlateral thoracotomy with moderate intraoperative bleeding. Two wedge resections and one lobectomy were performed in three cases where the parenchyma had been encroached. Tumors in three patients were pathologically benign; those in the other two were malignant. The symptoms disappeared in all cases after surgery.

Conclusions

Complete resection remains the mainstay of cure for giant SFTP. We recommend preoperative angiography and embolization for giant SFTP which can reduce the risk of hemorrhage and can contribute to piecemeal removal for radical excision.

Introduction

Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura (SFTP) represents a rare, slow-growing neoplasm. Historically, several different names have been used to designate this neoplasm because of controversy surrounding its histogenesis. Nowadays, the origin is recognized widely as mesenchymal cells of submesothelial tissues of the pleura rather than mesothelial cells [1]. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura are usually asymptomatic in their early stage and are often discovered incidentally by routine chest X-ray. Parts of these tumors tend to grow into massive lesions before there is evidence of local compression symptom. Surgery is the mainstay of therapy for SFTP. Complete excision of giant SFTP is a challenging task because of poor exposure, a significant tumor blood supply, and heavy adhesions, among other characteristics. In this article we report our experience with five patients with giant SFTP who underwent operation.

Materials and methods

From March 2007 to December 2009, of 29 patients with SFTP treated surgically in the Department of Thoracic Surgery of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital, 5 (17.2%) had giant tumors >18 cm in diameter, including four men and one woman, 57 years old on an average (age range: 44–78 years). One case was discovered by chance whereas four had symptoms related to the tumor, as follows: three with exertional dyspnea, one with right upper limb pain and fever. Expect for distal clubbing in one patient, there were no other paraneoplastic syndromes. None had a history of asbestos exposure. All patients underwent careful preoperative routine tests including radiographs, computed tomography (CT), scan and pulmonary function test. Two patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and one underwent gastroscopic examination. A CT-guided percutaneous biopsy was performed preoperatively in all cases. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunostaining, including vimentin, CD34, and CD31, were performed in each biopsy sample.

All patients underwent angiography and embolization of the tumor-supplying vessels on the day before operation (<20 h). Patients were maintained at a 45° lateral decubitus position during operation. Clinical data and other preoperative and postoperative characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of resected tumors of five patients with a giant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura

| No. | Age (years) | Gender | Side | Histology | Size (cm) | Weight (g) | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44 | Male | Left | Benign | 32 × 22 × 19 | 4,300 | Alive |

| 2 | 54 | Male | Right | Benign | 25 × 25 × 16 | 3,200 | Alive |

| 3 | 61 | Female | Right | Benign | 18 × 14 × 12 | 3,000 | Alive |

| 4 | 48 | Male | Left | Malignant | 20 × 10 × 9 | 2,000 | Alive |

| 5 | 78 | Male | Right | Malignant | 30 × 25 × 20 | 4,000 | Alive |

Outpatient follow-up was performed at 1, 3, and 6 months with a standard chest X-ray, then once a year with a chest CT scanning.

Results

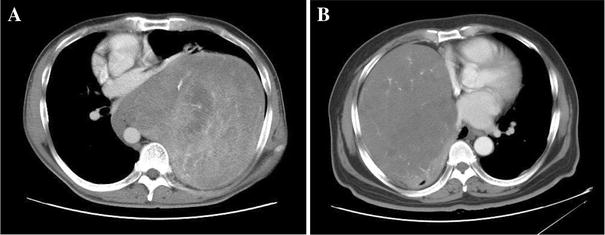

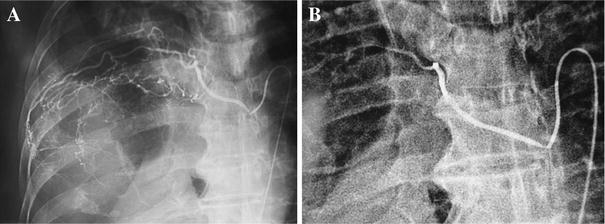

Computed tomography scanning of all five patients showed a huge lobulated heterogeneous mass with focal low attenuation, with apparent compression of the mediastinum and the lung (Figs. 1, 2). Three of these tumors were located in the right hemithorax and two in the left. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a cystic change zone and vascular flow voids (Fig. 3). Varicosity was observed in the inferior segment of the esophagus by gastroscopic examination in the patient with the largest tumor. Angiography delineated multiple feeding vessels of tumor, including several intercostals, as well as the internal mammary, inferior phrenic, and bronchial arteries (Fig. 4). The CT-guided percutaneous biopsydemonstrated a spindle cell tumor in three patients and failed to provide a conclusive result in other two. The diagnosis of SFTP was established before operation by immunohistochemical stains, which showed positivity for vimentin and CD-34, but negative stain for CD-31.

Fig. 1.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrates a heterogeneously enhancing soft-tissue giant mass on the left (a) and right (b) hemithorax

Fig. 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a massive tumor occupying most of the left hemithorax, producing mass effect on the mediastinum, diaphragm, and abdominal organs

Fig. 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrates the fibrous characteristic of the giant mass in the right hemithorax

Fig. 4.

a Angiography shows abundant feeding vessels of SFTP from the intercostal arteries. b Supplying vessels were embolized by polyvinyl alcohol through a microcatheter

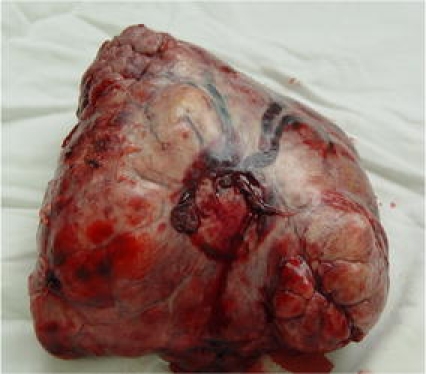

All patients underwent complete surgical resection of the tumor via an extended postlateral thoracotomy. Tumors were completely removed by piecemeal resection in four cases because of huge bulk, poor exposure, and extensive vascular adhesions. In three cases, en-bloc excision of tumor plus the involved lung was performed, two by wedge resection and one by anatomic lobectomy. The tumor appeared to arise from the parietal pleura in two cases, the visceral pleura in two, and the mediastinal pleura in one. The volume of bleeding during operation was 800 ml on average. The tumors ranged from 18 to 32 cm in diameter (mean: 25 cm) and weighed between 2,000 and 4,300 g (mean: 3,300 g) (Fig. 5). The preoperative symptoms disappeared after surgery in all patients. Entrapped lung achieved complete re-expansion proved by chest X-ray in four patients after operation. Re-dilatation pulmonary edema occurred on the second postoperative day in one case, and was relieved by administration of glucocorticoid. There were no other postoperative complications (mean hospital stay: 12.6 days).

Fig. 5.

Excision of a pedunculated solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura (SFTP) shows gross features: ovoid lobular mass with a pedicle attach to visceral pleura, with several vessels entering into the tumor through the pedicle

The macroscopic evaluation showed solid masses that were well encapsulated in appearance. The cut surface was hard and rubbery in consistency in three tumors and it was soft and brittle in the other two. All tumors had significant blood supply. Two tumors were malignant and the other three were benign according to the pathologic criteria of England et al. [1]. Vimentin and CD34 of immunohistochemistry evaluation were positive in all cases.

A short-term clinical and radiological follow-up (a median follow-up of 27.8 months) showed all five patients were free of disease.

Discussion

Giant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura is a rare form of pleural disease that is only occasionally cited in the literature, usually as single cases [2, 3]. The peak incidence of SFTP occurs in the fifth to eighth decades but may be found in any age group [4–6]. Most SFTPs are benign and develop slowly [1]. These tumors often have an asymptomatic clinical course. Thus tumors tend to grow into huge mass before local compression symptoms develop, especially in patients without routine physical examinations. About 50% of patients reported in the literature are symptomatic [4, 5]. Larger tumors may have a higher percentage of symptomatology.

In most cases, thoracic CT scan demonstrates a well-circumscribed, lobular, homogenous, soft-tissue mass [7]. However, large tumors are frequently heterogeneous due to necrosis, hemorrhage, or cystic changes. In our series, CT scan in all five cases showed heterogeneous density. Atelectasis, displacement of adjacent structures, and pleural effusion presented more frequently in giant SFTP. An MRI allows visualization of the diaphragm and is a sensitive instrument to exclude invasion of neighboring structures. An MRI is also helpful for assessing the vascular bed, although angiograms are more definitive [8]. A CT-guided aspiration biopsy was not considered a reliable tool because of its low diagnostic accuracy as reported by several authors [4–6, 9]. Nevertheless we obtained a satisfactory conclusive diagnosis by biopsy in three cases among five. Appropriate biopsy site, adequate specimens, and reference to immunohistochemical analysis may be of benefit for preoperative pathologic diagnosis.

It is well known that maximal treatment of SFTP is based on surgical excision. Resection is generally curative in all benign cases, and in approximately half of malignant cases [1]. Complete resection for giant tumor of the pleura is a challenging task because of poor exposure, significant blood supply, and other factors. Angiography is an important investigative tool with which to delineate major feeding vessels of tumor, which can be embolized before operation [7, 10, 11]. Preoperative embolism of major vessels can make operation safer by significantly reducing the risk of bleeding. In the series reported by England et al., five patients had aberrant vessels including a branch of the phrenic artery and a bronchial artery [1]. Angiography in those five cases demonstrated that the major blood supply to the tumor was from the intercostals, the internal mammary, inferior phrenic, and bronchial arteries. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) granules, microcoils, and sponge granules are used to embolize the blood supply through a micro-catheter. Surgery should then be carried out within 24 h for minimal blood loss. Too long a delay may reduce the effectiveness of embolization.

A giant sessile tumor with good movement may compress the heart and draw down blood pressure when the thoracic cavity is open. The 45° lateral decubitus position during operation is an easy and reasonable way to avoid compression. Peri-tumor extensive adhesions make it more difficult to ligate feeding vessels and handle hilar vessels, especially in a tumor with a broad-based pedicle. Piecemeal resection proved to be a practical method for removal of giant SFTP, because it can achieve better exposure and avoid impairing adjacent structure. Extended excision is necessary in cases of “inverted fibroma,” invasive tumor [3, 12]. Wedge resection is enough in most cases [4].

The completeness of surgical excision was an important prognostic factor for both benignity and malignancy. Thus some authors advocated intraoperative pathology examination in every case to obtain microscopically free surgical margins [13, 14]. To reduce operative time, we used extensive electric coagulation to pedicle rather than intraoperative frozen section to avoid recurrence in the two tumors that originated from the parietal pleura. We think that an intraoperative pathological examination is necessary in parietal pleura broad-based tumor in order to assess the surgical margins.

Atelectasis occurs frequently in giant SFTP, and removal of a giant tumor might result in pulmonary edema. It is therefore beneficial to use mechanism ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) during the first postoperative day. And it is important for these patients to undergo chest X-rays to check postoperative lung re-expansion.

The great majority of patients undergoing surgical removal of an SFTP have a benign clinical course, with a long-term disease-free survival in around 90% of the cases [4, 5, 14]. Long-term follow-up after complete resection is necessary because of the possibility of late recurrence of SFTP, especially in malignant ones [4].The follow-up of the two patients with malignant tumors in our series is too short (4 and 32 months, respectively) to establish a clinical judgment.

In conclusion, CT-guided aspiration biopsy, including immunopathologic examination, is helpful for preoperative diagnosis in SFTP. Angiography and embolization are important and useful in the diagnosis and treatment of giant SFTP. We advise that angiography and embolization should be done before operation in all giant tumors of the chest, including SFTP.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Solitary benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:640–658. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bar I, Papiashvilli M, Zukerman B, et al. Large solitary fibrous tumour of the pleura: analysis of six cases. Heart Lung Circ. 2007;16:282–284. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filosso PL, Asioli S, Ruffini E, et al. Radical resection of a giant, invasive and symptomatic malignant solitary fibrous tumour (SFT) of the pleura. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison-Phipps KM, Nichols FC, Schleck CD, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: results of surgical treatment and long-term prognosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardillo G, Faccilo F, Cavazzana AO, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: an analysis of 55 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1808–1812. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(00)01908-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magdeleinat P, Alifano M, Petino A, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: clinical characteristics, surgical treatment and outcome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21:1087–1093. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(02)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Abbott GF, Page McAdams H, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura. Radiographics. 2003;23:759–783. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan JH, Rahman SB, Clary-Macy C, et al. Giant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:1461–1464. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(98)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rena O, Filosso PL, Papalia E, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: surgical treatment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:185–189. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(00)00636-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss B, Horton DA. Preoperative embolization of a massive solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:983–985. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)03117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaul P, Kay S, Gaines P, et al. Giant pleural fibroma with an abdominal vascular supply mimicking a pulmonary sequestration. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:935–937. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)00553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breda C, Zuin A, Marulli G, et al. Giant solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: report of three subsequent cases. Lung Cancer. 2006;52:249–252. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Perrot M, Kurt AM, Robert JH, et al. Clinical behavior of solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1456–1459. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(99)00260-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardillo G, Carbone L, Carleo F, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: an analysis of 110 patients treated in a single institution. Ann Thorc Surg. 2009;88:1632–1637. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]