Abstract

Background

The assembly and spatial organization of enzymes in naturally occurring multi-protein complexes is of paramount importance for the efficient degradation of complex polymers and biosynthesis of valuable products. The degradation of cellulose into fermentable sugars by Clostridium thermocellum is achieved by means of a multi-protein "cellulosome" complex. Assembled via dockerin-cohesin interactions, the cellulosome is associated with the cell surface during cellulose hydrolysis, forming ternary cellulose-enzyme-microbe complexes for enhanced activity and synergy. The assembly of recombinant cell surface displayed cellulosome-inspired complexes in surrogate microbes is highly desirable. The model organism Lactococcus lactis is of particular interest as it has been metabolically engineered to produce a variety of commodity chemicals including lactic acid and bioactive compounds, and can efficiently secrete an array of recombinant proteins and enzymes of varying sizes.

Results

Fragments of the scaffoldin protein CipA were functionally displayed on the cell surface of Lactococcus lactis. Scaffolds were engineered to contain a single cohesin module, two cohesin modules, one cohesin and a cellulose-binding module, or only a cellulose-binding module. Cell toxicity from over-expression of the proteins was circumvented by use of the nisA inducible promoter, and incorporation of the C-terminal anchor motif of the streptococcal M6 protein resulted in the successful surface-display of the scaffolds. The facilitated detection of successfully secreted scaffolds was achieved by fusion with the export-specific reporter staphylococcal nuclease (NucA). Scaffolds retained their ability to associate in vivo with an engineered hybrid reporter enzyme, E. coli β-glucuronidase fused to the type 1 dockerin motif of the cellulosomal enzyme CelS. Surface-anchored complexes exhibited dual enzyme activities (nuclease and β-glucuronidase), and were displayed with efficiencies approaching 104 complexes/cell.

Conclusions

We report the successful display of cellulosome-inspired recombinant complexes on the surface of Lactococcus lactis. Significant differences in display efficiency among constructs were observed and attributed to their structural characteristics including protein conformation and solubility, scaffold size, and the inclusion and exclusion of non-cohesin modules. The surface-display of functional scaffold proteins described here represents a key step in the development of recombinant microorganisms capable of carrying out a variety of metabolic processes including the direct conversion of cellulosic substrates into fuels and chemicals.

Background

Macromolecular enzyme complexes catalyze an array of biochemical and metabolic processes such as the degradation of proteins [1,2] or recalcitrant polymers [3] as well as the high-yield synthesis of valuable metabolic products via substrate channeling [4]. From a biotechnological perspective, mimicking such process by incorporating catalytic modules or enzymes of interest within synthetic complexes can significantly enhance the efficiency of such bioprocesses via substrate channeling [5] and increased enzyme synergy [3]. In a cellulosome, multiple enzymes assemble into a macromolecular complex by their association with a scaffold protein for the efficient degradation of cellulose [6]. In the case of the gram-positive thermophile Clostridium thermocellum, the cellulosome is anchored to the surface of cells, resulting in one of the most efficient systems for bacterial cellulose hydrolysis [3,7].

Cellulosomal enzymes bear C-terminal type 1 dockerin (dock1) modules, which target them to a central scaffold protein (CipA) via chemically and thermally stable non-covalent interactions with one of nine cohesin (coh) modules [8]. CipA also contains a type 3a cellulose-binding module (CBM3a), allowing the different cellulases to act in synergy on the crystalline substrate, as well as a type 2 dockerin module which binds anchor proteins, ensuring the cellulosome's attachment to the cell [9,10]. Therefore, the architecture of the cellulosome establishes proximal and synergistic effects of enzymes within the complex when associated with the substrate [8,11,12]. These synergistic effects are further augmented by an extra level of synergy resulting from the cellulosome's association with the surface of cells, yielding cellulose-enzyme-microbe (CEM) ternary complexes [6,7,13-18]. CEM ternary complexes benefit from the effects of microbe-enzyme synergy, ultimately limiting the escape of hydrolysis products and enzymes, increasing access to substrate hydrolysis products, minimizing the distance products must diffuse before cellular uptake occurs, concentrating enzymes at the substrate surface, protecting hydrolytic enzymes from proteases and thermal degradation, as well as optimizing the chemical environment at the substrate-microbe interface [6,7,13-16].

In this work, we describe the cell surface display of small cellulosome scaffold proteins in Lactococcus lactis, a first and necessary step for the eventual engineering of extracellular protein complexes in this, and other bacterial hosts. "Mini" scaffold proteins have been intracellularly expressed and purified from hosts such as Escherichia coli or Bacillus subtilis for the purpose of assembling mini-cellulosomes in vitro [19-23]. The production of mini-cellulosomes in vivo has also been reported in Clostridium acetobutylicum and B. subtilis, however, complex localization was limited to secretion into the culture supernatant [24,25]. More recently, the surface-display of mini-cellulosomes was described in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, in some cases enabling growth on cellulosic substrates [26-29]. However, there have been no reports on the recombinant assembly of cellulosome-inspired complexes on the surface of bacterial cells. For this purpose, we chose L. lactis, a gram-positive bacterium with established commercial value. L. lactis is of specific interest as it is generally regarded as safe (GRAS), has been used to produce valuable commodity chemicals such as lactic acid [30] and bioactive compounds [31], and has been successfully engineered to secrete and/or display on its cell surface, a wide variety of proteins ranging from 9.8 to 165 kDa [32]. The metabolic engineering tools available in conjunction with the successful controlled expression and high-yield production of enzymes and proteins [32] make it an ideal candidate for the recombinant expression of cellulosomal components. Using L. lactis as a surrogate host, we successfully secreted fragments of CipA (CipAfrags) to the cell surface and the scaffolds retained functionality. All scaffolds containing functional cohesins were capable of associating with an engineered test enzyme, E. coli β-glucuronidase (UidA) fused with a dockerin. We envision expanding on this work to eventually engineer larger scaffolds that will serve as the basis for assembling and immobilizing large extracellular enzyme complexes.

Results

Regulated expression of CipAfrags yields the surface-display of scaffold proteins

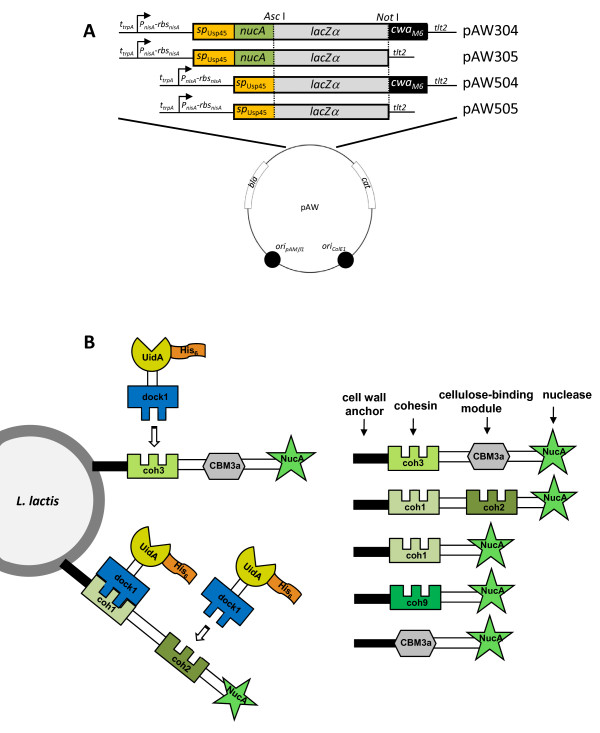

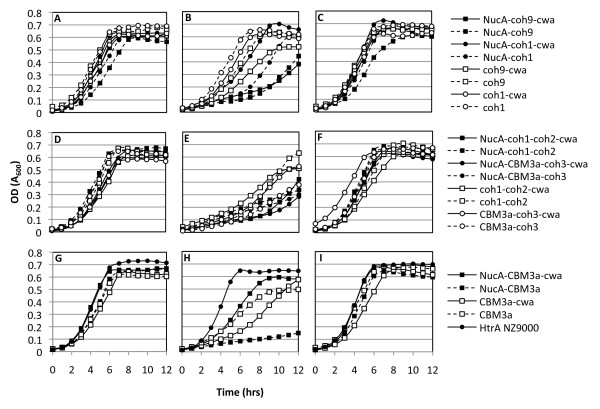

L. lactis HtrA NZ9000 cells were successfully transformed with either the pAW500 series or pAW300 series of vectors (Fig. 1A), resulting in strains expressing fragments of CipA (CipAfrags) alone, or as fusions with the NucA export-specific reporter, and/or the cwaM6 for anchoring of the scaffold to the cell-surface (Fig. 1B). Growth curves of engineered L. lactis strains were used to determine if the expression and secretion of scaffold proteins resulted in growth inhibition. Results from the growth experiments showed a correlation between cipAfrag gene expression and growth inhibition (Fig. 2). The constitutive over-production of recombinant proteins targeted to the cell surface in L. lactis may interfere with the integrity of the cell wall [33], whereas in C. thermocellum, the constitutive expression of CipA is modulated through catabolite repression [34]. In the absence of the inducer nisin, all cipAfrag-expressing strains grew similarly to the control L. lactis HtrA NZ9000 with a final cell density corresponding to an OD600 approaching 0.7 (Fig. 2A, D, G). This indicated that little change in growth profile resulted from any leaky expression of the recombinant proteins. Nisin induction at inoculation resulted in cellular toxicity, as demonstrated by extended lag phases, lower growth rates and final cell yields (Fig. 2B, E, H). In all cases, when induction of protein expression was carried out after 4 hrs of growth (corresponding to an OD600 ≈ 0.3), cultures did not display growth retardation and final cell densities were similar to those attained with no induction (Fig. 2C, F, I). Expression of the various cipAfrags from the constitutive P59 promoter consistently resulted in plasmid rearrangements as observed by restriction digest analysis of the rescued plasmids from both E. coli and L. lactis (data not shown). From these results, we hypothesized that unregulated high-level expression of the CipAfrag proteins was toxic to the cells and using a constitutive promoter such as P59 induced plasmid rearrangements that abolished or reduced cipAfrag expression. These results confirmed the necessity for regulating expression of the proteins, which was achieved using the PnisA promoter. With the exception of cell wall anchored scaffold containing only a cellulose-binding module (CBM3a-cwa) (Fig. 2H), removal of the NucA lowered or eliminated toxicity to the cells, as observed by improved growth rates and yields.

Figure 1.

pAW series of cipAfragexpression vectors and strategy for complex assembly. (A) Vectors were designed for facilitated insertion of fragments of the gene encoding the cellulosomal scaffold protein CipA, into AscI-NotI restriction sites. Scaffolds can be optionally expressed with or without an N-terminal nuclease reporter and/or a C-terminal cell wall anchor motif. pAW304 is designed for expression, secretion, and cell wall-targeting of CipA fragments (CipAfrags) as fusions with the N-terminal NucA reporter. pAW305 is designed for the expression and secretion of CipAfrags as a fusion with the N-terminal NucA reporter, but without the C-terminal anchor motif. pAW504 is designed for expression, secretion, and cell wall-targeting of CipAfrags without the N-terminal NucA reporter. pAW505 is designed for the expression and secretion of CipAfrags with neither the N-terminal NucA reporter nor the C-terminal anchor motif. (B) Graphic depiction of the surface-display strategy of engineered scaffolds and their association with the β-glucuronidase-dockerin fusion protein (UidA-dock1). All successfully displayed CipAfrags are portrayed as fusions with both NucA and a cell wall anchor, however were also expressed and tested without these two components.

Figure 2.

Growth profiles of L. lactis expressing CipAfrags alone or as fusions with M6cwa and/or NucA. Panels A, D and G represent cultures not induced with nisin, panels B, E, H represent cultures induced with 10 ng/mL nisin at inoculation (t = 0 hrs), and panels C, F, I represent cultures induced with 10 ng/mL nisin in log phase corresponding to an OD600 ≈ 0.3 (t = 4 hrs). Constructs were grouped according to their modular nature. Top panels depict constructs containing a single cohesin; Middle panels depict constructs containing two CipA modules; Lower panels depict constructs containing no cohesin modules. Black shapes indicate scaffolds containing a fusion with NucA, and white shapes indicate scaffolds where NucA has been removed. Solid lines represent scaffolds expressed with a cell wall anchor, and dotted lines represent scaffolds lacking the cell wall anchor. Experiments were repeated three times yielding identical trends between growth profiles.

NucA-CipAfrag proteins are localized to the cell wall of L. lactis

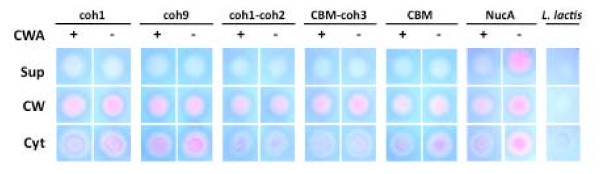

In order to quickly evaluate our success at recombinant protein secretion in L. lactis, a nuclease enzyme was fused to the CipA fragments to be displayed on the cell surface. L. lactis cells harboring the pAW300 series of vectors all displayed a NucA+ phenotype on plates overlaid with TBD agar, confirming that all variants of the NucA-CipAfrag proteins were successfully secreted and that the nuclease retained its function when expressed as an N-terminal fusion to CipAfrags. To determine the cellular localization of the expressed CipAfrag fusion proteins, cell fractionations were performed, and cytoplasmic, cell wall, and supernatant fractions were spotted on TBD agar. Of the secreted NucA-CipAfrag proteins, almost all detectable nuclease activity was found in the cell wall fractions corresponding to proteins released from lysozyme/lysostaphin treatments, suggesting successful cell wall targeting of the proteins (Fig. 3). CipAfrag proteins were not detected in the supernatant, suggesting that secreted proteins remained localized to the cell wall due to the activity of lactococcal sortase. Unexpectedly, the NucA-CipAfrag fusions lacking the cell wall anchor domain were also detected primarily in the cell wall fractions (Fig. 3) suggesting that fusion of NucA with CipAfrags caused the scaffolds to remain associated with the cell wall, even without covalent cross-linking by sortase. All of the cytoplasmic fractions were also found to contain varying levels of expressed scaffolds, a finding consistent with observations previously made while exporting recombinant proteins in L. lactis [35-38]. We hypothesize that these cytoplasmic proteins were either in the process of being synthesized and exported by the cell via cytoplasmic chaperones, or had evaded the sec-pathway due to a lack of recognition of the signal sequence. In certain instances, the net charge of N-terminal residues downstream of the signal peptide can also contribute to the poor secretion efficiency of recombinant proteins [39]. As expected from previous studies [36,37] in the absence of a cell wall anchor domain, NucA was secreted into the supernatant but remained associated to the cell wall if the anchor domain was present (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Cellular localization of NucA-CipAfrag scaffolds expressed by L. lactis with or without M6cwa. NucA activity was detected by spotting cell fractions on TBD-agar and analyzing for pink color formation. Fractions analyzed are supernatant (sup), cell wall (cw), and cytoplasm (cyt). Constructs are represented by their respective CipAfrag components and were expressed as fusions with NucA with or without cell wall anchor (cwa) domains.

Cell surface displayed CipAfrag scaffolds bind UidA-dock1

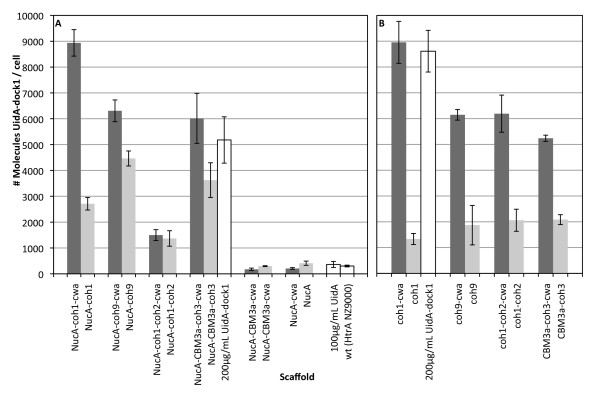

In vivo binding assays were performed to determine if a dockerin-containing enzyme could associate with cell surface displayed CipAfrag scaffold proteins. L. lactis cells expressing cell wall and supernatant-targeted scaffolds were incubated with purified β-glucuronidase enzymes fused to a dockerin module (UidA-dock1). After incubation, washed cells were assayed for β-glucuronidase activity, allowing a relative comparison of CipAfrag display efficiencies between engineered constructs. All constructs containing cohesin modules as part of their scaffolds successfully bound UidA-dock1, while those lacking cohesins as well as the plasmid-free L. lactis HtrA NZ9000 failed to do so (Fig. 4). Binding experiments using UidA lacking dock1 resulted in no successful "docking" onto L. lactis displaying NucA-CBM3a-coh3 (Fig. 4A) or any other recombinant scaffolds (data not shown). These results demonstrated that functional recombinant scaffolds could be expressed on the surface of L. lactis and that cell surface complex formation was dependent on the presence of both cohesin and dockerin modules. Among those strains secreting and displaying functional scaffolds, significant variation in display efficiency was observed. Assuming a 1:1 enzyme-to-cohesin ratio, the approximate number of cohesins and/or scaffolds per cell was determined. The strains that displayed the greatest number of nuclease bearing scaffolds (~9 × 103 scaffolds/cell) were those expressing the cohesin 1 module alone (coh1-cwa and NucA-coh1-cwa) (Fig. 4). Strains expressing coh9-cwa, NucA-coh9-cwa, coh1-coh2-cwa, CBM3a-coh3-cwa and NucA-CBM3a-coh3-cwa, were estimated to display between 5.0 × 103 and 6.3 × 103 scaffolds/cell. These results suggested that the size of the CipAfrag is not necessarily the limiting factor influencing scaffold display. This was further observed with the relatively lower amount of enzymes binding to L. lactis displaying NucA-coh1-coh2-cwa (1.5 × 103 UidAdock1/cell). Essentially, NucA-coh1-coh2-cwa is of similar size to NucA-CBM3a-coh3-cwa (approx. 68 kDa), contains twice as many cohesins, yet host cells where able to bind one quarter the amount of UidA-dock1 molecules. The predicted molecular weights of the engineered scaffolds were used in order to estimate the net amount of recombinant protein on the cell surface of strains producing scaffolds with a single cohesin. The culture producing the highest net yield of functional recombinant protein was the strain anchoring NucA-CBM3a-coh3-cwa on its surface. Cultures produced and displayed approximately 0.72 mg/mL of recombinant scaffolds, which remained cell-associated and fully functional.

Figure 4.

In vivo binding of UidAdock1 on live intact L. lactis cells displaying CipAfrags. CipAfrags were expressed and anchored as fusions with the NucA reporter enzyme (A), or lacking the NucA reporter (B). Quantification of UidAdock1 molecules bound to L. lactis cells corresponds to equivalent amounts of functional cohesin assuming a 1:1 ratio of dockerin-cohesin association. Dark grey bars represent scaffolds containing the C-terminal M6 cell wall anchor motif (cwa), and light grey bars represent their anchor-deficient derivatives. White bars correspond to indicated controls; "200 μg/mL UidA-dock1" represents binding assay carried out with excess enzyme and L. lactis pAW328 (NucA-CBM3a-coh3-cwa) to ensure saturation of cohesins. "100 μg/mL UidA" represents binding assay carried out in the presence of UidA and L. lactis pAW328 (NucA-CBM3a-cwa). Binding assay carried out with UidA and all other constructs resulted in no association with scaffold-expressing strains (data not shown).

The effect of the N-terminal nuclease reporter on secretion efficiency was also analyzed by comparing the binding capacity of L. lactis harboring the pAW300 series (nuclease fusions) with cells harboring the pAW500 (nuclease deficient) series of vectors. Initially included as a reporter to facilitate detection of exported scaffolds, we hypothesized that the nuclease fusion might also increase secretion efficiency, as has been previously observed [35,38]. Removal of NucA had no detrimental effects on scaffold display for all constructs (Fig. 4B), as similar amounts of anchor-containing scaffolds were located to the cell surface. Furthermore, removal of NucA resulted in a fourfold increase in the amount of coh1-coh2-cwa successfully displayed when compared to its NucA-containing counterpart. The presence of NucA appeared to interfere with the secretion of supernatant-targeted scaffolds from the cell, given that the cwa-deficient variants of coh1, coh9, and CBM3a-coh3 remained associated with the cell to a much larger extent than their NucA-deficient counterparts (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Several recent studies have reported on the recombinant expression of mini cellulosome scaffold proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [26-29]. In these examples, the potential application of the engineered strains for the direct conversion of cellulosic biomass to ethanol was the driving factor for choosing S. cerevisiae as a host. However, many more platform strains have been or are now being developed that will produce ethanol, biofuels other than ethanol, and non-biofuel chemicals [5,14,40-47]. The economics of these processes would be greatly improved if these engineered microbes could use cellulosic substrates. With this goal in mind, the first logical step in establishing this system was the successful secretion and display of cohesin-bearing scaffold proteins. Previous studies have demonstrated that controlled gene expression in L. lactis can reduce toxicity and increase net protein yields [33,48,49]. In our study, the constitutive expression of the scaffold proteins consistently led to cellular toxicity, a problem that was solved by delaying the onset of gene expression until the cells had reached mid log-phase. In cell division, higher concentrations of recombinant cell wall-targeted proteins are localized to the septum, the site of cell wall biosynthesis [33]. It is thus likely that over-expression of our scaffold proteins targeted to the extracytoplasmic space early in the growth phase impaired cell wall biosynthesis and ultimately resulted in cell death. Removal of NucA from the scaffolds decreased or eliminated cellular toxicity for all cohesin-containing constructs (Fig. 2), and we thus suspect that accumulation of NucA in the cytoplasm may also contribute to this observed lag in the onset of growth when induced at t = 0 hrs. In addition, as a larger proportion of scaffolds lacking a cell wall anchor remained trapped in the cell wall when fused with NucA, it is also likely that part of this observed reduction in toxicity is due to a decrease in the amounts of recombinant proteins being trapped in the cell wall and ultimately disrupting its integrity.

Quantification of cell surface displayed proteins in lactic acid bacteria was previously reported using fluorescence-activated cell sorting, flow cytometry, or whole-cell ELISA [50]. In our assay, functionality of the displayed CipAfrag scaffold proteins could be tested directly through binding with a dockerin-containing reporter enzyme, attesting that the number of cohesins detected was a direct quantification of those that retained biochemical function. Of the four expressed CipA fragments containing at least one cohesin (coh1, coh9, coh1-coh2, CBM3a-coh3), coh1 was displayed with the highest efficiency (~9 × 103 scaffolds per cell). Due to its small size and decreased number of modules compared with coh1-coh2 and CBM3a-coh3, we attribute part of this increase in display to the decrease in size of the scaffold itself. However, coh1 was also displayed more efficiently than coh9, which is approximately the same size and similar in primary amino acid sequence. One possible explanation may relate to the position of coh1 relative to coh9 on native CipA scaffold. Coh1 is located at the N-terminus of the 200 kDa scaffold CipA, adjacent to the processing site of the signal peptide by the sec-pathway machinery of C. thermocellum [7]. It is possible that the increase in secretion efficiency of coh1 when compared with coh9 may be in some part due to differences in amino acid content adjacent to the signal peptide, possibly increasing its accessibility to the chaperones involved in its transport to the extracytoplasmic space [51]. This, however, does not account for the differences in display efficiency between NucA-coh1 and NucA-coh9, as in both cases, NucA is adjacent to the signal sequence. The amount of sequence identity among cohesins perhaps provides a better explanation for these observed differences. Of the nine cohesin modules on CipA, cohesins 3 through 8 show between 96 to 100% sequence identity, whereas among the remaining cohesins, coh1 and coh9 show the least amount of sequence identity (69 and 75%, respectively) [52]. These differences in amino acid content may translate into differences in folding and solubility of the recombinantly expressed modules.

L. lactis was engineered to display a scaffold containing 2 cohesin modules (coh1-coh2). Based on a 1:1 binding ratio of the enzyme-cohesin and assuming equivalent expression and secretion, we expected this strain to bind twice the amount of UidA when compared to scaffolds of similar size but containing a single cohesin module (i.e. CBM3a-coh3). However, coh1-coh2 bound similar amounts of UidA as CBM3a-coh3 (Fig 4B). This reduction in UidA binding was not attributed to CipAfrag size differences, since both mature scaffolds have a theoretical molecular weight of 68 kDa, suggesting that other factors affected secretion and display efficiency. In fact, protein size is not regarded as a major bottleneck for protein secretion in L. lactis, as the size of successfully secreted heterologous proteins ranges from 6.9 kDa to a staggering 165 kDa [32]. We hypothesize that the substitution of a cohesin module by CBM3a may have enhanced secretion by increasing the rate of folding of the scaffold into its soluble form. A similar effect was recently reported with the fusion of the highly insoluble Clostridium cellulovorans cellulase CelL with the CBM of cellulase CelD, which resulted in dramatic increases in its solubility [53].

Comparisons between amounts of UidA binding to cells expressing CipAfrags with or without the cwaM6 domain revealed that the cell wall anchor motif significantly increased the amounts of functional scaffolds displayed on the cell (Fig. 4). With NucA present, CipAfrags lacking cwaM6 remained cell-associated to a larger extent (Fig. 3) and bound UidA (Fig 4), suggesting that NucA fusion proteins remained trapped in the cell wall for reasons other than covalent cross-linking by the sortase, but yet the cohesin modules were accessible to UidA. This phenomenon is well-documented in other studies of protein secretion in L. lactis, as in some cases the fusion of two generally well-secreted proteins results in changes in the folding of the hybrid protein, and deficiencies in their release from cells [37,54]. While the exact mechanism of this phenomenon is not clear, hydrophobic domains resulting from fusing two recombinant proteins may promote cell wall association [37].

Conclusions

Until now, all attempts to anchor enzymes on the surface of a bacterium have been limited to a single enzyme per anchor [33,35,36,38,50,55-61]. In our system, multiple enzymes could theoretically associate with scaffolds containing a corresponding number of cohesins. We used purified β-glucuronidase fused to a dockerin module as a probe to establish proper display and function of the cohesins, but envision co-expression of enzymes and scaffold in a subsequent development of the strain. We thus envision that further development of this cellulosome-inspired system may contribute to the efficient bioconversion of substrates into industrially relevant fuels and commodity chemicals, and that tailor-designed synthetic macromolecular complexes could be engineered to contain large permutations and combinations of desired enzymes of interest.

Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C with shaking (220 rpm). Lactococcus lactis HtrA NZ9000 was grown in M17 medium [62] supplemented with 1% (w/v) glucose (GM17) at 30°C without agitation. C. thermocellum was grown in ATCC1191 medium at 55°C with 0.2% (w/v) cellobiose as a carbon source. Where appropriate, antibiotics were added as follows: for E. coli, ampicillin (100 μg/mL), erythromycin (150 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (10 μg/mL) and kanamycin (30 μg/mL); for L. lactis, erythromycin (5 μg/mL) and chloramphenicol (10 μg/mL). General molecular biology techniques for E. coli were performed as previously described [63]. Genomic DNA was isolated from C. thermocellum as previously described [64]. To make competent cells, L. lactis was grown in M17 medium [62] supplemented with 1% (w/v) glucose, 25% (w/v) sucrose and 2% (w/v) glycine and cells were transformed as previously described [65]. M17 media was supplied by Oxoid, LB media was supplied by Novagen , all antibiotics, ρ-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucuronide and nisin were provided by Sigma, and X-gal and IPTG were supplied by Fermentas.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype/Decription | Source |

|---|---|---|

| L. lactis HtrA NZ9000 | MG1363 (nisRK genes on the chromosome) | [37] |

| E. coli TG1 | supE thi-1 Δ(lac-proAB) Δ(mcrB-hsdSM)5 (rK- mK-) [F' traD36 proAB lacIqZΔM15] | ATCC |

| E. coli DH5α | fhuA2 Δ(argF-lacZ)U169 phoA glnV44 Φ80 Δ(lacZ)M15 gyrA96 recA1 relA1 endA1 thi-1 hsdR17 | Invitrogen |

| E. coli BL21 (DE3) | F- ompT gal dcm lon hsdSB(rB- mB-) λ(DE3 [lacI lacUV5-T7 gene 1 ind1 sam7 nin5]) | Novagen |

| Plasmid | ||

| pVE5524 | Eryr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::P59::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA-cwaM6-t1t2 | [36] |

| pVE5523 | Eryr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::P59::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA-t1t2 | [36] |

| pSIP502 | Eryr; PnisA::rbsnisA::uidA | [66] |

| pSCNIII | Cmr | J. Seegersa |

| pUC19 | Ampr | [69] |

| pET28(b) | Kmr | Novagen |

| pSIPsp-nuc | Eryr; PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA | This Work |

| pUC104 | Ampr; ttrpA::PnisA::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA | This Work |

| pUC104mod | Ampr; ttrpA::P59::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA | This Work |

| pUC304 | Ampr; ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA | This Work |

| pUC504 | Ampr; ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45 | This Work |

| pAW004 | Eryr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::P59::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA-MCS-cwaM6-t1t2 | This Work |

| pAW005 | Eryr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::P59::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA-MCS-t1t2 | This Work |

| pAW004Z | Eryr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::P59::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA-lacZα-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW005Z | Eryr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::P59::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA- lacZα-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW004ZC | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::P59::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA-lacZα-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW005ZC | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::P59::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA- lacZα-tlt2 | This Work |

| pGEMc9 | Ampr; pGEMT::with cloned coh9 from cipA | This Work |

| pGEMc1 | Ampr; pGEMT::with cloned coh1 from cipA | This Work |

| pGEMc1-c2 | Ampr; pGEMT::with cloned coh1-coh2 from cipA | This Work |

| pGEMcbm-c3 | Ampr; pGEMT::with cloned cbm3a-coh3 from cipA | This Work |

| pGEMcbm | Ampr; pGEMT::with cloned cbm3a from cipA | This Work |

| pAW104 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA-LacZα-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW105 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsusp45::spUsp45-nucA-LacZα-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW301 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW302 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW304 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-lacZα-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW305 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-lacZα-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW307 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-coh9-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW308 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-coh9-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW310 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-coh1-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW311 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-coh1-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW334 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-coh1-coh2-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW335 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-coh1-coh2-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW328 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-cbm3a-coh3-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW329 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-cbm3a-coh3-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW331 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-cbm3a-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW332 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-nucA-cbm3a-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW504 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-lacZα-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW505 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-lacZα-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW507 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-coh9-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW508 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-coh9-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW510 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-coh1-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW511 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-coh1-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW534 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-coh1-coh2-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW535 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-coh1-coh2-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW528 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-cbm3a-coh3-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW529 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-cbm3a-coh3-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW531 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-cbm3a-cwaM6-tlt2 | This Work |

| pAW532 | Cmr, Ampr; pBS::pIL252::ttrpA::PnisA::rbsnisA::spUsp45-cbm3a-tlt2 | This Work |

| pETdock1 | Knr; pET28(b)::with cloned dock1 from celS | This Work |

| pETUdock1 | Knr; pET28(b)::PT7::6xHis-uidA-dock1 | This Work |

| pETU | Knr; pET28(b)::PT7::6xHis-uidA | This Work |

aVector pSCNIII was a gift provided by Jos Seegers (unpublished data)

pAW100 series of vectors are nisin-inducible and contain an intact rbsusp45. pAW300 series vectors are nisin-inducible and contain an intact rbsnisA. pAW500 series vectors are pAW300 variants lacking an N-terminal NucA fusion. P59, constitutive lactococcal promoter; PT7, inducible T7 promoter; PnisA, inducible nisA promoter; rbsusp45, Usp45 ribosome-binding site; rbsnisA, nisA ribosome-binding site; spUsp45, signal sequence of Usp45; nucA, staphylococcal nuclease; cwaM6, anchor motif of M6 protein; llt2, transcriptional terminator of rrnB operon; ttrpA, transcriptional terminator of trpA.

Assembly of cassettes for scaffold protein expression and targeting

The E. coli-L. lactis shuttle vectors pVE5524 and pVE5523 were used as backbone plasmids for targeting fragments of the CipA scaffold protein to the cell surface or supernatant, respectively [36]. The various CipAfrags were produced as fusions with the N-terminal signal peptide from the lactococcal Usp45 secreted protein (spUsp45) and for targeting to the cell wall, as a fusion with the C-terminal anchor from the Streptococcus pyogenes M6 protein (cwaM6) (Fig. 1). Expression cassettes were designed to allow the optional fusion of CipAfrags with an N-terminal nuclease reporter (NucA) used for detection of the fusion proteins in the extracellular milieu [35,38] (Fig. 1). The strong constitutive lactococcal promoter P59 [36] and the PnisA nisin-inducible promoter from the nisA gene of L. lactis [66] were tested for optimal expression of the recombinant scaffolds. Two ribosome-binding sites were also tested, that of the usp45 gene (rbsusp45) [36] and that of the nisA gene (rbsnisA) [66]. In order to facilitate the exchange of scaffold fragments in the expression cassette, AscI-NotI restriction sites were engineered just downstream of nucA (Fig. 1). To achieve this, an 800-bp fragment containing the nucA gene was PCR-amplified from pVE5524 using primers a and b (Table 2), digested with SalI-EcoRV and ligated into similarly digested pVE5524 and pVE5523, yielding pAW004 and pAW005. To facilitate detection of E. coli clones that harbor cipA fragments, a lacZ-α stuffer fragment was PCR-amplified from pUC19 using primers c and d, digested with AscI-NotI, and subsequently ligated into similarly cut pAW004 and pAW005, yielding pAW004Z and pAW005Z, respectively. Since L. lactis HtrA NZ9000 is resistant to erythromycin, the ery marker of the pAW vectors was replaced with the cat gene from pSCNIII. The cat gene was PCR-amplified using primers e and f, digested with AflII and HpaI, and ligated into similarly digested pAW004Z and pAW005Z, yielding plasmids pAW004ZC and pAW005ZC, respectively. For inducible expression of the scaffolds, we replaced the P59 promoter with PnisA from pSIP502. The PnisA promoter was isolated using primers o and p, digested with ApaI-NruI and ligated to similarly digested pAW004ZC and pAW005ZC, yielding pAW104 and pAW105, respectively.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| Primer | Sequence (5'-3') |

|---|---|

| a | TATAGATCTTCGATAGCCCGCCTAATGAGC |

| b | ATGATATCGCGGCCGCGGCGCGCCTCGAGATCGATTTG |

| c | TAGATATCGGCGCGCCATTAGCTATGCGGCATCAGAGC |

| d | TAGCTAGCGCGGCCGCGCCCAATACGCAAACCGCCTC |

| e | GATCTAGCCTTAAGTTCAACAAACTCTAGCGCC |

| f | CGTAGATCGTTAACCCTTCTTCAACTAACGGGG |

| g | TCGAGGCGCGCCCGGCCACAATGACAGTCGAGA |

| h | TCGAGCGGCCGCCGGTACGGAACTACCAAGAT |

| i | TAGGCGCGCCATAAGTTGACACTTAAGATAGGCAG |

| j | TAGCGGCCGCAGTTACAAGTACTCCACCATTG |

| k | TCGAGCGGCCGCCGGTGTTGCATTGCCAACGT |

| l | TCGAGGCGCGCCCGGATGATCCGAATGCAATAAAG |

| m | TCGAGCGGCCGCTACTACACTGCCACCGG |

| n | TGAGGCGCGCCCGGCAAATACACCGGTATC |

| o | ATGCGGGCCCGACCTAGTCTTATAACTATACTG |

| p | ATGTACTCGCGATTTATTTTGTAGTTCCTTCGAACG |

| q | AGAACAGTCATGAAAAAAAAGATTATCTC |

| r | ATATCTCGAGATCGATTTGACCTGAATCA |

| s | AGTCACATGTTCTTTCCTGCGTTATCCCCTG |

| t | ATGCTCGCGAAGATCTGGGATCAAAAAAAAGCCCGC |

| u | GCTTGAATTCTCTACTAAATTATACGGCGACGTCAATG |

| v | GCTTGCGGCCGCTTTAGTTCTTGTACGGCAATGTATC |

| w | ATGCGCTAGCATGTTACGTCCTGTAGAAACC |

Restriction enzyme cut sites are in bold.

Cloning of cipA fragments from C. thermocellum

Five unique cipA fragments were PCR-amplified from C. thermocellum genomic DNA using primer pairs g-h, i-j, g-k, l-m and n-m (Table 2), ligated into pGEM-T (Promega) and sequenced to verify the integrity of the gene sequence. The resulting pGEM plasmids were digested with AscI-NotI to release the cipA gene fragments and these were ligated into pAW004ZC and pAW005ZC. The cipA fragments were chosen on the basis of containing a single cohesin (coh1 or coh9), two cohesins of identical specificity (coh1-coh2), one cohesin and a cellulose-binding module (coh3-CBM3a) and only a cellulose-binding module (CBM3a) (Fig. 1). The resulting spUsp45-nucA-cipAfrag-cwaM6 cassettes were under control of the P59 promoter and contained rbsusp45. The same cipA fragments were cloned into pAW104 and pAW105 for inducible expression of the scaffold proteins.

For the inducible expression of the fusion proteins under the control of PnisA with an intact ribosome-binding site from the nisA gene (rbsnisA), spUsp45-nucA was PCR-amplified from pAW004ZC using primers q and r, creating a BspHI cut site at the 5' end of the PCR product. The PCR product was digested with BspHI and XhoI and ligated to pSIP502 digested with NcoI-XhoI, effectively replacing the gusA gene with spUsp45-nucA, retaining the first lysine of the signal peptide, and yielding pSIPSPNUC. For the insertion of an upstream transcriptional terminator and removal of nucA, a 1500-bp SapI-XbaI fragment was temporarily removed from pAW104, and was ligated to similarly cut pUC19, yielding vector pUC104. To introduce the E. coli transcriptional terminator from the tryptophan synthase operon (ttrpA) upstream of PnisA and to introduce a BglII cut site, a 200-bp fragment containing ttrpA was PCR-amplified from pVE5524 using primers s and t, digested with AflIII-NruI and ligated to similarly-cut pUC104, yielding pUC104mod. Plasmid pSIPSPNUC was digested with BglII-XhoI and ligated to similarly-digested pUC104mod, yielding vector pUC304. This was the base vector harboring the ttrpA-PnisA-rbsnisA-spUsp45-nucA cassette, which was digested with ApaI-AscI and ligated into the pAW100 series of vectors. Inserting this cassette into ApaI-EcoRV digested pAW110 and pAW111, yielding pAW301 and pAW302, respectively, created controls lacking cipA fragments for expression of nucA alone. For deletion of the nucA reporter and construction of the pAW500 series, pUC304 was digested with SalI-XhoI and self-ligated, yielding vector pUC504. The ttrpA-PnisA-rbsnisA-spUsp45 cassette was released via digestion with ApaI-AscI, gel-purified, and ligated to similarly-cut pAW100 series vectors, yielding the pAW500 series of vectors. This cassette was also ligated into similarly cut pAW104 and pAW105 yielding base vectors containing the lacZ-α stuffer fragment. The final expression vectors for this study included the pAW300 series of vectors for inducible expression and targeting of NucA-fused scaffolds, and the pAW500 series of vectors for inducible expression and targeting of scaffolds lacking the N-terminal NucA reporter (Fig. 1).

Expression and localization of CipAfrags in L. lactis

L. lactis HtrANZ9000 was transformed with the pAW300 and pAW500 series of vectors for the controlled expression of scaffolds. It contains chromosomal copies of the nisR and nisK genes necessary for nisin-inducible expression of cassettes under control of the nisA promoter, and is deficient in a major extracellular housekeeping protease, which has been shown previously to be responsible for the proteolysis of exported recombinant proteins [37]. Growth curves were used to evaluate the potential of growth inhibition caused by the over-expressed CipAfrag proteins. Growth curves were performed in 96 well plates and cells were induced with 10 ng nisin/mL at inoculation (t = 0 hrs), 4 hrs post-inoculation (t = 4 hrs) or were not induced. For the expression of CipAfrag proteins in L. lactis HtrA NZ9000, overnight cultures were diluted 1/50 into fresh GM17 medium and were induced with 10 ng nisin/mL when an OD600 ≈ 0.3 was reached (4 hrs). After 20 hrs growth, successful CipAfrag secretion was evaluated using a nuclease assay consisting of spotting cells on TBD-agar and observing pink color formation [36]. For analysis of NucA-CipAfrag proteins in various cellular locations, cell fractionation was performed as described previously [58], with the addition of lysostaphin (0.6 mg/mL) [67]. Aliquots of proteins were blotted on TBD-agar plates and formation of a pink color was analyzed after a 1-hr incubation at 37°C.

Expression and purification of CipAfrag-binding β-glucuronidase

The E. coli β-glucuronidase (UidA) was engineered to have a C-terminal dock1 module for binding onto CipAfrag scaffolds, as well as an N-terminal 6 × His-tag for protein purification. The dock1 module of the C. thermocellum celS gene was amplified from C. thermocellum genomic DNA using primers u and v (Table 2). PCR products were digested with EcoRI-NotI and ligated to similarly-digested pET28(b), yielding pETdock1. The uidA gene lacking a stop codon was amplified using primers w and x and pSIP502 as template. The PCR product was digested with NheI-EcoRI and ligated to similarly-cut pET28(b) and pETdock1, yielding His-tagged UidA proteins with and without a dock1 module (pETUdock1 and pETU). His-tagged proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3). Cultures were induced at an OD600 of 0.5 with 1 mM IPTG and incubated for an additional 5 hrs at 37°C. Cells were harvested (1000 × g, 10 min, 4°C) and cell pellets were kept overnight at -80°C. Thawed cell pellets were suspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, containing 300 mM NaCl. Samples were subjected to sonication (15 sec pulse, 5 sec between pulses, 2 min total process time) and lysates were loaded on approximately 10 mL of Ni-NTA sepharose resin. The resin was washed with phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.0) containing 300 mM NaCl and 20 mM imidazole and eluted using the same buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. Fifty μL of each elution fraction were added to 450 μL GUS buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7), 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100. Samples were heated for 1 min, after which p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucuronide was added to a final concentration of 4 mg/mL [68]. The UidA-containing fractions were identified by the appearance of a yellow color. Proteins from the elution fractions showing UidA activity were visualized by SDS-PAGE on a 12% (w/v) gel to identify fractions containing the highest purity of enzyme. The specific activities of UidA-dock1 and UidA were determined by colorimetric assays in a thermostated UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Cary 50 WinUv) at 405 nm, using a 1 cm (L) cuvette, and the known molar extinction coefficient of p-nitrophenol being 18 000 M-1 cm-1. Quantification of the proteins was done using a Bradford protein assay kit (Pierce) and BSA as a standard. Specific activities were used to evaluate the amount of enzyme bound to cells in the in vivo binding assay described below.

Binding of β-glucuronidase to L. lactis

L. lactis HtrA NZ9000 cells harboring the pAW300 or pAW500 series of vectors, as well as the plasmid-free strain were grown overnight in GM17 medium. Cultures were diluted 1/50 in 5 mL of fresh media and grown for an additional 4 hrs (OD600 ≈ 0.3) after which cells were induced with 10 ng nisin/mL for scaffold expression. After 20 hrs of growth, cells from 1-mL of culture were harvested (4,300 × g, 5 min, 4°C) washed once in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.0) containing 300 mM NaCl and suspended in 100 μL of purified UidA-dock1 or UidA at a concentration 100 μg/mL. To ensure that saturation of all cohesin sites was achieved, binding assay with 200 μg UidA-dock1/mL was tested for L. lactis harboring pAW328. Binding was carried out at 4°C for 10 hrs. Cells were then washed 6 times to eliminate residual enzyme activity and suspended in 100 μL of phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.0) containing 300 mM NaCl for detection of β-glucuronidase activity. For quantification of bound UdiA-dock1, 50 μL of washed cells were analyzed for β-glucuronidase activity. Reactions were stopped with 250 μL of 1 M sodium carbonate once a yellow color appeared, and the duration of each assay was recorded. The specific activities of the purified UidA-dock1 and UidA were used to determine the amount of enzyme bound onto the L lactis cells. Using the calculated molecular weight of UidA-dock1 and the known amount of cells present in each sample, the average number of enzyme units bound per cell was estimated. Assuming a 1:1 cohesin to dockerin ratio, the number of enzymes present per cell also is a representation of the number of cohesins present on the cell surface. The calculated molecular weight of the scaffolds was used to estimate the net amount of recombinant protein anchored to cells in respective cultures. Experiments were repeated twice and true biological replicates (independent colonies and cultures) were performed in triplicate for all samples.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

VM defined the strategy described and supervised the project. AW designed and carried out all experiments. AW drafted the initial manuscript, VM helped draft the manuscript, and both AW and VM edited the manuscript. VM supervised the entire PhD project of AW. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Andrew S Wieczorek, Email: as_wiecz@alcor.concordia.ca.

Vincent JJ Martin, Email: vmartin@alcor.concordia.ca.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Alexandra Gruss and Dr. Isabelle Poquet for providing base expression vectors for LAB as well as strains of L. lactis. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Andy Ekins for his help in reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by research grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (grant numbers 312357-06 and 330781-06) the Canada Foundation for Innovation (grant number 202359) and a Canada Research Chair to V.J.J.M. A.S.W. is the recipient of graduate scholarships from NSERC and the Fonds Québécois de la Recherche sur la Nature et les Technologies.

References

- Lowell GH, Ballou WR, Smith LF, Wirtz RA, Zollinger WD, Hockmeyer WT. Proteosome-lipopeptide vaccines: enhancement of immunogenicity for malaria CS peptides. Science. 1988;240:800–802. doi: 10.1126/science.2452484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell GH, Smith LF, Seid RC, Zollinger WD. Peptides bound to proteosomes via hydrophobic feet become highly immunogenic without adjuvants. J Exp Med. 1988;167:658–663. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer EA, Belaich JP, Shoham Y, Lamed R. The cellulosomes: multienzyme machines for degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:521–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.091022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrado RJ, Varner JD, DeLisa MP. Engineering the spatial organization of metabolic enzymes: mimicking nature's synergy. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:492–499. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueber JE, Wu GC, Malmirchegini GR, Moon TS, Petzold CJ, Ullal AV, Prather KL, Keasling JD. Synthetic protein scaffolds provide modular control over metabolic flux. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynd LR, Weimer PJ, van Zyl WH, Pretorius IS. Microbial cellulose utilization: fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:506–577. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.506-577.2002. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz WH. The cellulosome and cellulose degradation by anaerobic bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;56:634–649. doi: 10.1007/s002530100710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruus K, Lua AC, Demain AL, Wu JH. The anchorage function of CipA (CelL), a scaffolding protein of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9254–9258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibovitz E, Beguin P. A new type of cohesin domain that specifically binds the dockerin domain of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome-integrating protein CipA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3077–3084. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3077-3084.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire M, Ohayon H, Gounon P, Fujino T, Beguin P. OlpB, a new outer layer protein of Clostridium thermocellum, and binding of its S-layer-like domains to components of the cell envelope. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2451–2459. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2451-2459.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi A, Amano Y, Murashima K, Doi RH. Hydrophilic domains of scaffolding protein CbpA promote glycosyl hydrolase activity and localization of cellulosomes to the cell surface of Clostridium cellulovorans. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:6351–6359. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.19.6351-6359.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Campayo V, Beguin P. Synergism between the cellulosome-integrating protein CipA and endoglucanase CelD of Clostridium thermocellum. J Biotechnol. 1997;57:39–47. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(97)00086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zverlov VV, Klupp M, Krauss J, Schwarz WH. Mutations in the scaffoldin gene, cipA, of Clostridium thermocellum with impaired cellulosome formation and cellulose hydrolysis: insertions of a new transposable element, IS1447, and implications for cellulase synergism on crystalline cellulose. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4321–4327. doi: 10.1128/JB.00097-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynd LR, van Zyl WH, McBride JE, Laser M. Consolidated bioprocessing of cellulosic biomass: an update. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Zhang YH, Lynd LR. Enzyme-microbe synergy during cellulose hydrolysis by Clostridium thermocellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16165–16169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605381103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron J, Ben-Ghedalia D, Morrison M. Invited review: adhesion mechanisms of rumen cellulolytic bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 2001;84:1294–1309. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)70159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer EA, Kenig R, Lamed R. Adherence of Clostridium thermocellum to cellulose. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:818–827. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.2.818-827.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TK, Weimer TK, Zeikus JG. Cellulolytic and physiological properties of Clostridium thermocellum. Arch Microbiol. 1977;114:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00429622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierobe HP, Bayer EA, Tardif C, Czjzek M, Mechaly A, Belaich A, Lamed R, Shoham Y, Belaich JP. Degradation of cellulose substrates by cellulosome chimeras. Substrate targeting versus proximity of enzyme components. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49621–49630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207672200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierobe HP, Mechaly A, Tardif C, Belaich A, Lamed R, Shoham Y, Belaich JP, Bayer EA. Design and production of active cellulosome chimeras. Selective incorporation of dockerin-containing enzymes into defined functional complexes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21257–21261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierobe HP, Mingardon F, Mechaly A, Belaich A, Rincon MT, Pages S, Lamed R, Tardif C, Belaich JP, Bayer EA. Action of designer cellulosomes on homogeneous versus complex substrates: controlled incorporation of three distinct enzymes into a defined trifunctional scaffoldin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16325–16334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingardon F, Chanal A, Tardif C, Bayer EA, Fierobe HP. Exploration of new geometries in cellulosome-like chimeras. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:7138–7149. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01306-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashima K, Kosugi A, Doi RH. Synergistic effects on crystalline cellulose degradation between cellulosomal cellulases from Clostridium cellulovorans. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:5088–5095. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.18.5088-5095.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perret S, Casalot L, Fierobe HP, Tardif C, Sabathe F, Belaich JP, Belaich A. Production of heterologous and chimeric scaffoldins by Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:253–257. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.1.253-257.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabathe F, Soucaille P. Characterization of the CipA scaffolding protein and in vivo production of a minicellulosome in Clostridium acetobutylicum. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1092–1096. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.1092-1096.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito J, Kosugi A, Tanaka T, Kuroda K, Shibasaki S, Ogino C, Ueda M, Fukuda H, Doi RH, Kondo A. Regulation of the display ratio of enzymes on the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell surface by the immunoglobulin G and cellulosomal enzyme binding domains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:4149–4154. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00318-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SL, Oh J, Singh S, Chen R, Chen W. Functional assembly of minicellulosomes on the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell surface for cellulose hydrolysis and ethanol production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:6087–6093. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01538-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly M, Fierobe HP, van Zyl WH, Volschenk H. Heterologous expression of a Clostridium minicellulosome in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009;9:1236–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen F, Sun J, Zhao H. Yeast surface display of trifunctional minicellulosomes for simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of cellulose to ethanol. Appl Environ Microbiol. pp. 1251–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Petrov K, Urshev Z, Petrova P. L+-lactic acid production from starch by a novel amylolytic Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis B84. Food Microbiol. 2008;25:550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez I, Molenaar D, Beekwilder J, Bouwmeester H, van Hylckama Vlieg JE. Expression of plant flavor genes in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1544–1552. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01870-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Loir Y, Azevedo V, Oliveira SC, Freitas DA, Miyoshi A, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Nouaille S, Ribeiro LA, Leclercq S, Gabriel JE. et al. Protein secretion in Lactococcus lactis : an efficient way to increase the overall heterologous protein production. Microb Cell Fact. 2005;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita J, Okano K, Kitao T, Ishida S, Sewaki T, Sung MH, Fukuda H, Kondo A. Display of alpha-amylase on the surface of Lactobacillus casei cells by use of the PgsA anchor protein, and production of lactic acid from starch. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:269–275. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.269-275.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YH, Lynd LR. Regulation of cellulase synthesis in batch and continuous cultures of Clostridium thermocellum. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:99–106. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.1.99-106.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieye Y, Hoekman AJ, Clier F, Juillard V, Boot HJ, Piard JC. Ability of Lactococcus lactis to export viral capsid antigens: a crucial step for development of live vaccines. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:7281–7288. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7281-7288.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieye Y, Usai S, Clier F, Gruss A, Piard JC. Design of a protein-targeting system for lactic acid bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4157–4166. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.14.4157-4166.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi A, Poquet I, Azevedo V, Commissaire J, Bermudez-Humaran L, Domakova E, Le Loir Y, Oliveira SC, Gruss A, Langella P. Controlled production of stable heterologous proteins in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:3141–3146. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.6.3141-3146.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro LA, Azevedo V, Le Loir Y, Oliveira SC, Dieye Y, Piard JC, Gruss A, Langella P. Production and targeting of the Brucella abortus antigen L7/L12 in Lactococcus lactis: a first step towards food-grade live vaccines against brucellosis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:910–916. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.2.910-916.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langella P, Le Loir Y. Heterologous protein secretion in Lactococcus lactis: a novel antigen delivery system. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1999;32:191–198. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X1999000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsumi S, Hanai T, Liao JC. Non-fermentative pathways for synthesis of branched-chain higher alcohols as biofuels. Nature. 2008;451:86–89. doi: 10.1038/nature06450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Eddy C, Deanda K, Finkelstein M, Picataggio S. Metabolic engineering of a pentose M\metabolism pathway in ethanologenic Zymomonas mobilis. Science. 1995;267:240–243. doi: 10.1126/science.267.5195.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CH, Mulchandani A, Chen W. Versatile microbial surface-display for environmental remediation and biofuels production. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittmann D, Lindner SN, Wendisch VF. Engineering of a glycerol utilization pathway for amino acid production by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:6216–6222. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00963-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Chou H, Ham TS, Lee TS, Keasling JD. Metabolic engineering of microorganisms for biofuels production: from bugs to synthetic biology to fuels. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers PL, Jeon YJ, Lee KJ, Lawford HG. Zymomonas mobilis for fuel ethanol and higher value products. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2007;108:263–288. doi: 10.1007/10_2007_060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen EJ, Kang Y, Bokinsky G, Hu Z, Schirmer A, McClure A, Del Cardayre SB, Keasling JD. Microbial production of fatty-acid-derived fuels and chemicals from plant biomass. Nature. pp. 559–562. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shaw AJ, Podkaminer KK, Desai SG, Bardsley JS, Rogers SR, Thorne PG, Hogsett DA, Lynd LR. Metabolic engineering of a thermophilic bacterium to produce ethanol at high yield. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13769–13774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801266105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vos WM. Gene expression systems for lactic acid bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:289–295. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez-Humaran LG, Cortes-Perez NG, Le Loir Y, Alcocer-Gonzalez JM, Tamez-Guerra RS, de Oca-Luna RM, Langella P. An inducible surface presentation system improves cellular immunity against human papillomavirus type 16 E7 antigen in mice after nasal administration with recombinant lactococci. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:427–433. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05472-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenhouts K, Buist G, Kok J. Anchoring of proteins to lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:367–376. doi: 10.1023/A:1002095802571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerngross UT, Romaniec MP, Kobayashi T, Huskisson NS, Demain AL. Sequencing of a Clostridium thermocellum gene (cipA) encoding the cellulosomal SL-protein reveals an unusual degree of internal homology. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:325–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle B, Myers C, Kruus K, Wu JH. Interactions of the CelS binding ligand with various receptor domains of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosomal scaffolding protein, CipA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1200–1203. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1200-1203.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashima K, Kosugi A, Doi RH. Solubilization of cellulosomal cellulases by fusion with cellulose-binding domain of noncellulosomal cellulase engd from Clostridium cellulovorans. Proteins. 2003;50:620–628. doi: 10.1002/prot.10298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez-Humaran LG, Langella P, Miyoshi A, Gruss A, Guerra RT, Montes de Oca-Luna R, Le Loir Y. Production of human papillomavirus type 16 E7 protein in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:917–922. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.2.917-922.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avall-Jaaskelainen S, Lindholm A, Palva A. Surface display of the receptor-binding region of the Lactobacillus brevis S-layer protein in Lactococcus lactis provides nonadhesive lactococci with the ability to adhere to intestinal epithelial cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:2230–2236. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.4.2230-2236.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Perez NG, Azevedo V, Alcocer-Gonzalez JM, Rodriguez-Padilla C, Tamez-Guerra RS, Corthier G, Gruss A, Langella P, Bermudez-Humaran LG. Cell-surface display of E7 antigen from human papillomavirus type-16 in Lactococcus lactis and in Lactobacillus plantarum using a new cell-wall anchor from lactobacilli. J Drug Target. 2005;13:89–98. doi: 10.1080/10611860400024219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm A, Smeds A, Palva A. Receptor binding domain of Escherichia coli F18 fimbrial adhesin FedF can be both efficiently secreted and surface displayed in a functional form in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:2061–2071. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2061-2071.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piard JC, Hautefort I, Fischetti VA, Ehrlich SD, Fons M, Gruss A. Cell wall anchoring of the Streptococcus pyogenes M6 protein in various lactic acid bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3068–3072. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.3068-3072.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raha AR, Varma NR, Yusoff K, Ross E, Foo HL. Cell surface display system for Lactococcus lactis: a novel development for oral vaccine. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;68:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1851-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy R, Yasawardena S, Zomer A, Venema G, Kok J, Leenhouts K. Immunogenicity of a malaria parasite antigen displayed by Lactococcus lactis in oral immunisations. Vaccine. 2006;24:3900–3908. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Liu Q, Wang Q, Zhang Y. Novel bacterial surface display systems based on outer membrane anchoring elements from the marine bacterium Vibrio anguillarum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:4359–4365. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02499-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzaghi BE, Sandine WE. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Microbiol. 1975;29:807–813. doi: 10.1128/am.29.6.807-813.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 3. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wang WK, Wu JH. Structural features of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulase SS gene. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1993;39-40:149–158. doi: 10.1007/BF02918985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holo H, Nes IF. High-frequency transformation, by electroporation, of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris grown with glycine in osmotically stabilized media. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:3119–3123. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.12.3119-3123.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorvig E, Gronqvist S, Naterstad K, Mathiesen G, Eijsink VG, Axelsson L. Construction of vectors for inducible gene expression in Lactobacillus sakei and L plantarum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;229:119–126. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidler L, Viaene J, Fiers W, Remaut E. Functional display of a heterologous protein on the surface of Lactococcus lactis by means of the cell wall anchor of Staphylococcus aureus protein A. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:342–345. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.342-345.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson L, Lindstad G, Naterstad K. Development of an inducible gene expression system for Lactobacillus sakei. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2003;37:115–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]