Abstract

This paper focuses on the role of religion and spirituality in dementia caregiving among Vietnamese refugee families. In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with nine Vietnamese caregivers of persons with dementia, then tape-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed for emergent themes. Caregivers related their spirituality/religion to three aspects of caregiving: (1) their own suffering, (2) their motivations for providing care, and (3) their understanding of the nature of the illness. Key terms or idioms were used to articulate spiritual/religious dimensions of the caregivers’ experience, which included sacrifice, compassion, karma, blessings, grace and peace of mind. In their narratives, the caregivers often combined multiple strands of different religions and/or spiritualities: Animism, Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and Catholicism. Case studies are presented to illustrate the relationship between religion/spirituality and the domains of caregiving. These findings have relevance for psychotherapeutic interventions with ethnically diverse populations.

Keywords: Vietnamese, caregiving, religion, spirituality, dementia

INTRODUCTION

As the elderly population in the United States becomes more ethnically diverse, there is a growing need to understand how cultural factors influence caregiving processes (Hinton, 2002; Dilworth-Anderson et al, 2002; Janevic and Connell 2001; Yeo and Gallagher-Thompson 2006). This knowledge can inform the development of culturally-tailored and efficacious interventions, public health messages, and community outreach at all levels. A more detailed understanding of the articulation of religion and caregiving can also be very important in the “cultural formulation” of clinical care for patients (Lewis-Fernandez 1996; Boehnlein 2006).

Prior work, largely studying African Americans, has suggested that religion and spirituality are an important adaptive strength for minority families providing care to someone with dementia (Milne and Chryssanthopoulou 2005; Gerdner et al 2007). However, surprisingly little work examines the relevance of religion and spirituality among Asian American caregivers. This research gap is particularly striking in view of the rapid growth that has been projected in the number of older Asian Americans, including those with dementia, in the years to come. It is also a gap that greatly needs to be addressed because the Asian religious and spiritual traditions differ significantly from other religious schools of thought, such as the Judeo-Christian traditions.

Religion and spirituality are important aspects of Vietnamese culture (Jamison, 1993) that may influence beliefs and attitudes towards mental health and illness as well as related patterns of care-seeking (Phan and Silove 1999). Prior studies of dementia within Vietnamese families have also noted the importance of religion and spirituality. One such study done in Hawaii found that both Buddhism and Confucianism were important value orientations influencing caregiving (Braun et al 1996) among the Vietnamese focus group participants. This is significant because Vietnamese often attribute dementia to factors of normal aging, physiological, psychological, or spiritual/religious causes (Yeo et al 2001), and often combine these causes with the biomedical model of dementia (Hinton et al 2005).

Even as prior work has highlighted the potential importance of religion and spirituality among Vietnamese caregivers, it is an important sphere that has not been an area of specific focus. There has also been little attention given to exploring intra-ethnic diversity among Vietnamese caregivers, and how they incorporate religion and spirituality into their caregiving experiences. To address this gap in the literature, our paper reports the result of a qualitative analysis examining the influence of religion and spirituality on the experience of dementia caregiving among Vietnamese. In order to provide context for our qualitative findings, we now briefly discuss the major religious orientations of Vietnam.

When discussing Vietnam's religious schools of thought, scholars describe a spiritual-religious complex that is in many respects distinctive, especially when compared to non-Asian or Anglo-European and Judeo-Christian religious traditions (Tai 1985). For example, folk religion is the oldest of Vietnam's religious systems, encompassing beliefs in a supernatural realm that is inhabited by deities and spirits: “The stones, the mountains, the trees, the streams, and the rivers, and even the air was full of these deities, ghosts, and spirits” (Tai 1985). The spirit world also referred to the souls of the departed, including deceased family members or ancestors, who continue to influence and animate the visible, natural realm of the living. In popular Vietnamese culture, the animistic folk religions were melded with, rather than supplanted by, religions and spiritual traditions introduced at later times.

Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, sometimes referred to as the three religions (tam giáo) (Tai 1983), were introduced to Vietnam during the more than 1000 years of Chinese occupation. Confucianism offers a concrete set of rules to strive for in the here and now, as well as a more fully developed ethical and moral dimension to religious life (Jamison 1993; Lin 1981). Often viewed as a philosophical rather than a religious system, Confucianism placed high emphasis on social relations, conduct, and harmony. Its spiritual component is built on the concepts of ancestor worship, filial piety, and self-cultivation through moral/just conduct. In keeping with the tendency toward religious mutualism, Taoism is a combination of Chinese philosophy and religious ritual emphasizing synchronicity with nature, balance between internal and external elements, and connections between the world of humans and the supernatural (Schipper 1982; Tai 1985). Simply rendered, Taoist traditions combine the esoteric practice of engaging the spirits -as with animism and ancestor worship- but places high importance on “right action” and morality that is also espoused by Confucianism, while at the same time emphasizing a unique perspective on harmony and balance that pertains to the universe as a whole. Buddhism, specifically the Mahayana school of Buddhism that gained a foothold in Vietnam, emphasizes engagement with the world through acts of compassion to alleviate the suffering of others and self-cultivation to achieve enlightenment. Buddhism emphasizes fate, inevitability, and the acceptance of personal and collective suffering in the face of life's challenges (Hanh 1967; Hanh 1995).

Lastly, Christianity -more specifically Catholicism- was introduced in Vietnam by the 16th century Jesuits, who encouraged its integration with the pre-existing religious systems, particularly Confucianism. Because many Vietnamese living in the American occupied South and formerly divided Vietnam of recent history were Catholics, and eventually fled the country when the Communist government ascended, Catholicism remains the prominent religious orientation of many Vietnamese in the United States, as well as those Vietnamese settled in other parts of the world.

It is important to recognize that regardless of whether they identify themselves as “Buddhist” or “Catholic,” Vietnamese are likely to draw upon multiple strands of their rich religious tradition. The melding of these multiple strands is evidenced in the development of Caodaism, a fairly recent minority religious movement in Vietnam that is based on the unification of the various religious traditions mentioned above (Blagov 2002). Thus, Vietnamese have a religious or spiritual orientation reflecting multiple, complementary, and related religious or spiritual perspectives (Taylor 2004). Scholarship on religion in Vietnam has revealed how these various religious traditions form a single Vietnamese religious system, sometimes referred to as the Vietnamese religious/spiritual complex (Tam 1985).

As this brief overview suggests, Vietnamese culture offers a rich religious and spiritual tradition for caregivers to draw upon in constructing their narratives of caregiving. In this discussion, the term religiosity is used to refer broadly to symbols, concepts and practices linked to distinct religious-spiritual traditions in Vietnamese history and culture. Our view of religion is broadly consistent with that described by Geertz (1973) as “a system of symbols which acts to establish a powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men” (p. 90).

In the caregiving experience, religiously and spiritually based symbolic meanings may be an important set of resources that caregivers draw upon to shape both their understandings of illness, as well as their motivations and approach to the day-to-day process of caregiving. Approaches to caregiving may be shaped by culturally-based ideas about the caregiver's role, idioms of distress or “burden,” ideas about what constitutes “good” or “bad” care, family interactional styles, and views of “normal” and “abnormal” aging. The use of these resources may also be variable and situational (i.e., used in strategic ways by social actors).

This view is in contrast to now outdated top-down views of culture as a shared set of ideas and of all ethnic group members as bearers of these cultural contents (Hinton et al 1999; Banks 1996). More recent theory and empirical study of culture and health within the anthropological literature places considerable emphasis on intra-cultural diversity. This reflects postmodern views of culture as contested, diverse, and changing (Barth 1994; Marcus and Fisher 1986; Hinton and Kleinman 1993).

In the field of ethnogerontology, Henderson (1980) and others (Hinton 2002; Valle and Lee 2002) have suggested that qualitative methods are the appropriate starting point for gathering basic descriptive data on how cultural groups experience and respond to dementing illness. One advantage of this approach is that it provides an “experience-near” account of the phenomenon of interest, revealing the perspective of those who are being studied, emphasizing their language and understandings.

In this paper, examination of the Vietnamese religious complex relationship to caregiver experience was done to understand that Vietnamese religion/spirituality is a potentially important cultural resource on which Vietnamese caregivers may draw. The specific research questions that framed this qualitative study were: 1) What aspects of Vietnamese religion and spirituality do caregivers draw upon when constructing their narratives of caregiving? and 2) Which aspects of caregiving are influenced by Vietnamese religion and spirituality?

METHODS

This study was conducted as part of a collaboration between the Stanford Geriatric Center and the Harvard Center on Culture and Aging, one of a number of Centers nationwide that was funded through the Health Promotions and Minority Health Initiative, an initiative supported by the NIA and the Office for Minority Health. The study is based on interviews with nine family caregivers recruited through contacts at organizations and institutions in the San Francisco Bay and greater Los Angeles area known to serve a large Vietnamese community, and through personal contacts of the research assistants, both of whom are ethnic Vietnamese.

To be eligible for the study, the care recipient needed to be an elder who was either formally diagnosed with dementia or Alzheimer's disease, or who was judged to have dementia or probable Alzheimer's disease based on the caregiver's description of the caregiver recipient's symptoms and disabilities. The caregivers recruited for this study included six women and three men, all of whom were born in Vietnam. Interviews were conducted in Vietnamese by a trained research assistant and averaged two hours each. An interview guide that primarily consisted of open-ended questions was constructed and used to elicit the caregiver's conceptions of, explanation for, and management of illness. It is important to note that the interview guide was not focused on the topic of religion and spirituality. Rather, the importance of religion and spirituality emerged in spontaneous comments by caregivers as they related their narratives of caregiving experiences.

The transcripts were tape-recorded and, in most cases, transcribed into Vietnamese, and then translated into English for analysis in several steps. An initial reading focused on the nature of religious or spiritual content and revealed this as an important and emergent theme in these narratives. A second step involved reading through the interviews and systematically coding (i.e. identifying) all mentions of religion/spirituality within these narratives. The third and final step was to analyze the coded material in order to identify the influence of spiritual/religious meanings on the process of caregiving.

Through this third step in the analysis, three different domains of caregiver experience were identified: (1) the experience and management of personal distress or suffering directly resulting from living with and/or caring for the person with dementia, (2) the meaning and motivation for providing care to a person with dementia, and (3) the nature of the illness itself. Key idioms and terms identified in this analysis are described in more detail in each of the three sections. Finally, in order to contextualize the data and demonstrate more clearly how Vietnamese caregivers incorporated multiple strands of religion into their caregiving narratives, case vignettes were chosen and developed for each theme.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Caregivers interviewed in this study all immigrated to the United States from Vietnam between the mid-1970's and the early 1990's. Most resided in California's San Francisco Bay Area, with ages ranging from 29 to 78 years of age. Six out of the nine caregivers and seven of the care recipients were female. Three of the caregiver-care recipient pairs were spousal pairs, whereas the others were parent-child pairs with the exception of one, where the niece was the elder's caregiver. Catholicism was the predominant religion among the caregivers who were interviewed. Two caregivers were Buddhist and one caregiver was nonspecific regarding her religious orientation, but stated that her mother followed the Buddhist faith.

Spiritual or religious influences on the experience of suffering

These narratives reveal many sources of suffering for family caregivers who are caring for someone with dementia, including difficult behavioral problems such as violent or aggressive behaviors, incontinence, paranoia, and intense time demands. Caregivers also underscored that the older person with dementia suffered as a result of his or her condition. The caregivers often expressed how religion and spirituality either helped them or the person they cared for give meaning to suffering, and also helped the caregivers manage their personal suffering. Within this context, religion and spiritual orientations emerged as a powerful way in which caregivers made sense of, and coped with their own distress in the realm of caregiving.

As with caregivers in general, most troublesome to the caregivers interviewed were the violent behaviors and repetitive behaviors. The same care recipient who smeared his feces on walls also required anti-psychotic medications due to episodes of hitting his daughter. The caregiver describes her demented father's routine as follows: “Okay. Many times, the two of us are sitting. I get his food for him and then sit next to him. Then, suddenly he says, ‘I'm not eating.’ I just say, ‘Eat father.’ I give the food to him and he says, ‘I'm not eating’ and pushes it away. Then as I sit down next to him, he raises his hand. As soon as I see that his hand is raised –because I've taken care of him for so long- as soon as he raises his hand, I duck and run right away.” [46-year-old daughter, Catholic]

The caregivers often turned to religion in order to sustain a positive attitude about caring for their elderly parents or spouses. Prayer was mentioned by a number of Catholic caregivers. When asked what he did when depressed, one male caregiver replied: “Well, I'm Catholic. I pray that God helps strengthen me... I ask God to strengthen me to give me the ability to persevere so I can take care of my wife, so I can fulfill my responsibilities as a husband, that's all” [70-year-old husband, Catholic]. Another caregiver attributed his ability to control his temperament when caring for his wife by having faith and practicing various acts of faith, such as fasting and abstinence from meat [78-year-old husband, Buddhist]. Generally, when religion emerged, it was a positive source for the caregivers in terms of coping with distress and hardships.

Acceptance is a core orientation to life and suffering within Buddhism, and is discussed by the caregivers as a source of strength, helping them to avoid excessive or unnecessary worrying. The importance of acceptance (chấp nhận) was linked to the idea of perseverance and endurance. These terms were spoken by several caregivers as an attitude towards dealing with very difficult situations. A caregiver described her acceptance thus: “We have to accept things the way they are, no other choice” [42-year-old wife, Buddhist] and, “I do feel that things are difficult, but we have to endure and surpass the difficulties. Because what else am I supposed to do?” [46-year-old daughter, Catholic]. In contrast to the more passive stance towards caregiving, the following caregiver's story emphasizes a more active, problem-solving approach.

Cultivating peace of mind: The story of Thao

Thao was the 51-year-old single woman who was born in Saigon, and recently immigrated to the US with her mother when sponsored by one of her older brothers, who was already in California. Thao, the caregiver, worked as a pharmacist in Vietnam, although she had to do this in a clandestine fashion after the Communist takeover. Thao remained unmarried; so, in keeping with traditional Vietnamese mores, she lives with her mother and supports herself by working as a nanny. During the day she has the twofold job of caring for children and her mother, who is 71, and suffers from a moderate to severe degree of memory loss and executive impairment. Although Thao has four brothers and sisters, she is her mother's primary caregiver, and appears to shoulder the bulk of her mother's daily needs.

It wasn't clear during the course of the interview how Thao came to be her mother's primary caregiver, but she made it clear to us that the responsibility was difficult for her in two respects. First, caring for her mother prevented Thao from going to school in the U.S. and pursuing a business of her own. Thao expressed to us that she was burdened by the responsibility of caring for her mother, because she felt that she would be blamed if her mother experienced a fall or died. Thao also expressed resentment that her brothers and sisters did not do more to help her in caring for their mother. She dreamed of going to school in the U.S. in order to get a good job, but was ultimately unable to do so because of the supervision and care required by her mother. She states: “sometimes I get very upset, I think my mother is very selfish. She wants to tie me down so I cannot go anywhere.” Thao wanted to place her mother in a convalescent facility and ultimately found support for this among friends at her church, but was initially constrained by resistance from members of her own family.

Thao described her parents as Buddhist, but had herself attended a Catholic school in Vietnam. When in the U.S. however, she was befriended by and influenced by members of the Episcopal Church. When asked whether religion helped Thao in the care of her mother, she emphasizes the connection between religious and spiritual practices (e.g. praying), and the cultivation of peace of mind (đầu óc bình an) and a state of inner balance:

I: If you didn't have religion, would it be hard to take care of your mother?

C: I think it would be harder because my mother is becoming more difficult day after day. If I don't have Jesus, then I would become selfish. That means I would have to think of myself, I would have to enjoy my life. How come there are five of us brothers and sisters, and I am the one who gets stuck. I thought like that at that time but I am the one who followed Jesus, so I have to set examples. In my family, at that time, I had a brother who was an alcoholic. He upset me a lot, but my mother loved him the most. Sometimes if I complained a lot about him, then it would make my mother sad. She would prefer to be the one doing the complaining rather than me. Sometimes, I have told my brother about the word of God. I told him everybody should have a good foundation, a soul to keep but if he kept drinking, he would not die, but he would develop diseases and people would avoid him. I used my mother's example to tell my brothers and sisters: “Look at mother. The reason she became like this is because she used her head too much. She didn't know how to have peace of mind. So this is the result of that. So I have to endure, I have to set an example...

I: So now you have done what you can...

C: Yes, even now my older brother, Quyen, and his wife. They are both doctors, and almost 50 years old. They also believe that Jesus gave them peace of mind, so they follow him and I think that it is very good.

I: Because of An?

C: Because of An. I told him, and An also told him that everybody has problems. But if we do not have religion to count on, then we will not have peace of mind. Spirituality is very important. If our mind is affected, it controls our body, and will create all kinds of disease. If we have peace of mind, it won't happen. If we think too much, then we can't sleep. First we will have a headache, then we can't eat, then we will have stomach problems. I learned about it, so I know. All my bothers and sisters are educated. I know they don't know how to have peace of mind. Some have problems with their children; others have other kinds of problems and this does not allow for peace of mind. Now I turn to the true path. I know we are very small, if we encounter something that is out of our control, then we offer it up to God. But it does not mean that we wash our hands of it after we give it to him. We still have to find ways to resolve it. Sometimes I just sit still and pray, or I pray when everything is quiet around me. When I pray, I feel so peaceful. All of the sudden, I find solutions to my problems so easily. I think God gives me the light, otherwise I will be trapped, irritated, and more depressed. Then I cannot solve anything...

Peace of mind (đầu óc bình an) is contrasted with “thinking too much” (suy nghĩ nhiều), providing an explanation for her mother's illness, and giving rise to fears about the toll of caregiving. “Thinking too much” is counter to the Buddhist ideal of a directed, centered, and calm mind. Thao's implied admonition against “thinking to much” is also in line with Taoist ideas about the critical importance of maintaining inner and external balance or harmony, wherein not doing so is thought to possibly damage body and brain (Hinton et al 2003; Hinton et al 2000).

Another interesting aspect of Thao's story is the way in which she draws upon religion and spirituality and her social network in the Episcopal Church to support her desire to place her mother in custodial care, which continues to be a matter of face, filial piety and viewed as an indication of poor family dynamics among Vietnamese. Thao eventually reframed her decision to place her mother in a convalescent facility as a compassionate and respectful act which would ensure that her mother receive proper care.

Spiritual/religious influences on the motivations and approach to caregiving

In addition to describing the many difficulties attendant with caregiving and its associated personal suffering, caregivers described the meanings and motivations attached to providing care for their family member. Not surprisingly, given its enormous importance in Vietnamese culture, caregivers often described their own motivation for caregiving in terms of filial respect and piety (có hiếu), a key idiom and value that reflects the strong hold of Confucianism on Vietnamese culture. Caring for a parent or older family member was viewed within the context of a culturally prescribed moral commitment of the younger generation to care for the older family members. Doing so is also viewed as a way of appeasing the ancestors and gaining their blessings and approval.

As illustrated in Thao's narrative above, several caregivers made a direct and seamless link between filial piety and religious/spiritual idioms, such as sacrifice, compassion (tình thương), and Karma (cái hậu). A Christian caregiver said, “It's in our culture and is the pillar of teachings about family life. A tenet of the family institution is to revere the elderly. Care for and love the elderly...” [56-year-old daughter, Catholic].

The idiom of sacrifice (hy sinh) was used by one 70-year-old husband to describe his meaning and motivation for caring for his wife. He takes care of his wife together with his sons, one of whom was present for the interview. After being asked how he has adapted to his wife's condition and his role as her caregiver, the husband described the importance of sacrifice, at one point directly addressing his son:

C: I live according to my faith, faith in God. For instance, there are people who call it God, people who call it the Spirit, people who call it the Creator, people who call it Buddha. Well I believe very much in those things being able to give me more blessings. The second thing is - - for example, when you ask about experience to help your mother, you should remember the word “sacrifice.” For example, today your friends invited you [the son] out but your mom needs you, so you sacrifice the fun to stay home to make your parents happy. That's sacrifice. Like us coming here in our old age. We don't quite fit in and feel very sad, giving ourselves to Jesus we must sacrifice for our children. Otherwise, sitting around and worrying would make us mad or sick. To me, I'm open, I'm removed. I just think that to live according to God's idea means to sacrifice for everyone, that's all. Sacrifice for my wife, my children, whatever comes I'll take. I don't ask for my share.

Sacrifice (hy sinh) is used here in a Catholic sense, and not only to frame caregiving for his wife, but also as a moral orientation towards interpersonal relationships within the family. Within the context of the Catholic faith, the term “sacrifice” is linked with Christ's sacrifice, which is a model for others in dealing with their own difficult life situations and circumstances. In addition to conveying to the interviewer the husband's experience and meaning of caregiving for his wife, the narrative is also a “teaching moment” in which the caregiver highlights his son's filial behavior and reframes it as sacrifice. Thus, spiritual and religious motivations were viewed as reinforcing the core cultural value of filial piety and respect.

Along with sacrifice, the caregiver emphasizes the importance of “acceptance” of one's situation, and notes in the following paragraph that many old people “go mad” because of conflicts with their children, a desire to control them, and a perceived lack of proper respect for their parents. He notes that a key to his own sense of inner peace or “happiness” is his acceptance (chấp nhận) of the fact that in the United States, “our kids come first, parents second.” Yet in the context of this narrative, he is also praising his son's behavior, and thereby reinforcing traditional filial values reframed and articulated with Catholicism through the idiom of “sacrifice.”

Compassion (tình thương) and Karma (cái hậu) also emerged as religious/spiritual influences on the meaning and motivation toward caring for older family members with dementia. A husband caring for his wife acknowledges the necessity of compassion: “My wife is sick and makes things difficult...It's correct to say that with my wife's illness, wherever she lives she'll be a great bother to people around her. She can only live where people have a lot of compassion, where they take pity and will help, because this illness likes to bother people very much, and people are compassionate about those things.” Of note, in contrast to Theravada Buddhism, which emphasizes withdrawal from the world, the Mahayana school of Buddhism, which gained a foothold in Vietnam, emphasizes engagement with the world through acts of compassion to alleviate the suffering of others.

Another important source of motivation for caregiving resulted from the caregivers’ belief in karma, which was often joined with strands of various spiritual beliefs involving the Christian afterlife, redemption through self-sacrifice, and the practice of “dharma.” In the following case, a Catholic caregiver drew upon these concepts to explain her own motivation for caring for the elderly.

“There is Karma in everything we do”: The story of Phuong

Phuong, the caregiver, is a 42-year-old female who self-identifies as Catholic, and is the care recipient's “niece” by way of extensive kinship ties. Phuong received 12 years of formal education in Vietnam prior to migrating to the U.S. in 1991 at the age of 37. She is not formally employed, but is supported by the kinship network of family members, and partially from the care recipient's monthly entitlement check. Phuong was interviewed three months after the demented elder had moved in with her. It was decided that the elder should move into Phuong's home because the elder's own daughter was not able to cope with the elder's repetitive questioning and other difficult behaviors. Perhaps because she was not working and had previous experience working with the elderly in Vietnam, Phuong was chosen by the care recipient's daughter to take care of the demented elder.

This caregiver understands the elder's problem as confusion (lẫn) that is a normal and natural consequence of the process of aging. For Phuong, care of the elderly is difficult because “the old person has a lot of complexes.” By complexes, Phuong means difficult characteristics, such as stubbornness, refusal to listen to others, and being disagreeable, characteristics that Phuong believes are a return to the basic nature that the elder had as a younger person. Repetitive behaviors are viewed as a product of confusion, but also attributed to this difficult predisposition of the elderly. Phuong was quite open with us about how difficult it is to take care of her “aunt” because of the behavioral problems.

In order to deal with the elder's difficult behaviors, Phuong draws heavily on her Catholic orientation, and emphasizes the importance of compassion:

C: Well now she has stopped doing it. She has already stopped doing it. Honestly, God loves us. I don't have any special talent, but it's by the grace of God. I bring out all of my abilities, all of my compassion and all of my charity/goodwill for her.

Later Phuong noted: “If you don't have compassion and charity within you then there's no way you can live with them...It's very tiring.” Thus, for Phuong, compassion is strong motivation to care for older persons, and helps her cope with her own personal suffering. It is expressed here as being tired, although in other parts of the interview Phuong describes feeling angry and frustrated, particularly when faced with the repetitive behaviors.

Later in the interview, when asked how she finds the ability to persevere as a caregiver, Phuong expresses her motivation for caregiving in terms of Karma:

C: Oh, the issues of morale? I care a great deal for the elderly. I love and care for them a lot because I believe that there is karma in everything that we do. We have to think that later, when we are old, we will also reach that road too. So now, we love and help the elderly so that later on, God will also provide another person to help us in return. So in helping, I don't differentiate between elders who aren't my parents or who don't have blood relation to me. I don't do it just to do it, and not for the money or for a bowl of rice. I wouldn't do it without compassion. Now, even if that person didn't mean anything to me, I would still use my compassion to do it, because I believe that karma will benefit us later. I look to my afterlife.

I: Where does that idea come from?

C: (laughter) Oh, that idea? Back in the days when I was in school, I used to read a lot of books. I read a lot of books on psychology. So from the reading and inquisitiveness, I went to work as a volunteer in such places to develop an understanding and to learn for myself. And from that, I find that we have love/compassion for the elderly. And we go home, and see that our parents are old and we love them and realize that later on, we'll also arrive at that road. So we have to, we...I don't know how, but I think we just have that intuition. Because sooner or later, we all face the afterlife and no one can be young forever, sooner or later, we have to grow old. But when we're old, well, if we can't have compassion for the elderly now, then when we're old, we probably won't have anyone to love us either. One more thing is that I believe and think that we must set an example in our family...My father often said that and I saw my father and my mother as two role models in my family. My parents loved and cared for my maternal and paternal grandparents very much. They loved them a lot, and also had great filial piety for them. Both of my parents always talked about those who gave birth to us.

I: So in a way, you are doing this as a way of paying homage to your parents?

C: We can never pay our parents enough homage! But we can take that thought and use it as an example for living life. So my father said that everything we do affects our afterlife. So, if we don't work with compassion and have God's grace helping us in our work, then we can't possibly do it. So whatever we do, no matter what we do, if we don't do it, then fine. But if we do it, then we have to realize all of our obligations and put our effort and soul into doing it. That's what my father taught me. So it's through such teaching that we're mature now. As the days go by, we think back more and more about the words our father spoke, and we realize they we are very correct. My father loved his elders very much, both of my paternal and maternal grandparents. So at the last moments of his life, he received many blessings from God. So now, I use that as an example of how to live my life.

The narrative illustrates a fluidity of different aspects of what was described earlier as Vietnam's religious traditions. The narrative begins with an emphasis on Christian values of charity and compassion, goes on to seamlessly weave these together with the Buddhist concepts of Karma, and then to what is ultimately a re-affirmation of the Confucian notions of filial piety and indirectly with ancestor worship, then comes full circle to the Christian concept of blessings (phưởc lanh) or grace of God (ơn của Thiên Chúa). In Christianity, with emphasis on Catholicism, compassion or love is one of the ten moral commandments (Spirago and Clarke 1993). According to Christian thought, with suffering and sacrifice, God also grants believers the grace to accept and endure all hardships and to love selflessly. Through this, caregivers of the Catholic faith are able to love, accept and adapt to their elder's decline too (Spirago and Clarke 1993).

The term compassion also resonates deeply in Mahayana Buddhism, and aligns with the central Buddhist teaching that acceptance of suffering is one of the four “Sublime Attitudes” leading to attainment of enlightenment and Nirvana. Buddhism places emphasis on suffering and its acceptance, but also leaves wide berth for its opposite experience -joy- through the exercise of compassionate thought, acts, and just conduct. Instead of struggling against what is likely an unchangeable situation –such as dementia- the caregivers with Buddhist leanings strive to accept and adapt to their elder's decline, and seek to express “compassion” in their day-to-day caregiving activities. As such, compassion is a way of creating good dharma as well, a crucial motivator for this caregiver.

For this self-professed Catholic caregiver, Buddhism also provides an incentive to accept and move beyond one's own suffering in order to provide care for others, via the framework of “dharma”, or action, and “karma”, or consequence. Dharma affects the goal of enlightenment and the ending of rebirth. In this way, all action and conduct can become religious activity, leading to good versus bad karma, and the need to exercise good will and compassion in order to mitigate the karma of one's past lives. Although Phuong was only distantly related to her care recipient, she managed to persevere where the elder's own daughter was unable to continue by drawing on wells of compassion. Phuong used her sense of compassion for the elderly in general, and projected her own mother's presence onto her elderly relative, allowing her to care even more deeply for someone in her extended family for whom she had little obligation to provide care for.

Spiritual or religious influences on conceptions of illness

There is a long tradition of drawing upon religion and spiritual explanations for misfortune in Vietnamese culture (Malarney 2002). Several caregivers spoke of their care recipient's illness as being the manifestation of God's will or plan, as in: “God gave humans that, so it just has to be like that. There's nothing we have to be afraid of” [56 year old daughter, Catholic]. Another caregiver expressed the idea that the illness was caused by too much worrying, and also linked this personality trait to God's will: “I think my wife worries too much...I think it's because God made each person with a certain trait” [70 year old husband, Catholic]. Some caregivers cited demonic possessions, curses, or spiritual possessions as causes for dementia. Below, we present the case of Tam, the caregiver who used spiritual possession and other spiritual/religious strands to make sense of his wife's illness.

Dementia as spirit possession: The story of Tam

Tam is a retired 78 year old barber with little formal education who is now the only caregiver for his 66 year-old wife. The couple migrated to the U.S. in 1992 through a United Nations Orderly Departure Program. Early in the interview, Tam framed his demented wife's confusion and erratic behavior as a consequence of somatic causes, but also spoke of her physical and mental pain as the result of Western medication that was “too strong” for her. He was conveying Taoist philosophies pertaining to concepts of balancing various properties within the body, and the belief that the Western medications had caused an imbalance, and therefore suffering within his wife's body.

Tam has tried multiple avenues of treatment. As he put it: “With the Eastern medication, she at times drinks about 50 preparations of herbal formulas and it doesn't improve the condition at all. So we turn to Western medicine and it causes heat and discomfort or hot temperament, and then we turn back to traditional medication, for instance a traditional medication with herbs and acupuncture.”

The care recipient, Tam's wife, is currently seeing more than three Western doctors, including a psychiatrist, a family practitioner, and a gastroenterologist. Later in the interview, Tam enthusiastically related a story about how he has put his faith in a spirit medium and the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy in order to heal his wife. The day before the interview, Tam had taken his wife to a spiritual medium for the first time. The medium practices in a local Buddhist temple, and the ceremony appears to combine elements of Taoism, Buddhism and folk religion.

Tam says that in order to cure his wife:

C: The first thing is that we have to worship and appeal to Buddha or the Lady Buddha Quang Am, this and that Buddha to give us faith in the unseen forces/spirits...Worship and appeal, believe in Buddha. At night when we go to bed, we light incense to worship the Lady Buddha Quang Am or Buddha. We have faith in and we believe so that the pain will subside. Abstain from meat, follow Buddha, control one's temperament, don't be hot tempered or often think and wonder about something so that the mind is stressed, and eventually it will subside. This Sunday we'll have to go worship a few times. I'll just be frank, this isn't that it's going to stop right away, but that we have to decide to go many times and eventually...plus, we have to practice grounding our mind. Don't think a lot or get upset/angry a lot, don't be hot tempered or angry about anything. Have to set ourselves to calming our temper, or if we think and wonder about something, give it all up and eventually the illness will slowly go away.

Tam's search for a cure for his wife is also pragmatic:

C: ...For example, if we are ill/hurt, we would go wherever people can do something, go to shamans/voodoo masters/spiritual masters too.

He describes his own religious orientation in the following way:

C: To be correct, I'm not totally of the Buddhist religion. I pay homage/worship the ancestors and stuff, our inner self knows to revere the Heavens, revere Buddha. Our conscious knows to ‘eat right and talk straight’, fast, and look to Buddha. That's all I know. Don't do anything cruel, then pay homage. Here is paying homage to the Lady Buddha Quang Am. Sometimes I think she is like a guardian to the Elder, helps Elder. So it's not exactly like the Buddhist religion.”

Although the caregiver is not entirely of the Buddhist faith, he still draws strongly upon the Buddhist religion to shape his understanding and help-seeking for his wife's illness. He states “pray/appeal in Buddha” and “have faith so the pain will subside...and eventually the illness will go away”, yet he is “not totally of the Buddhist religion.” In addition, he mentions fasting, avoiding stress and maintaining equilibrium in temperament, which is strongly Taoist in philosophy. This aspect of the caregiver's faith again demonstrates how Vietnamese can draw upon different religious and spiritual traditions to explain illnesses such as dementia.

In this specific case vignette, the caregiver makes references to spiritual possessions as the reason behind his second wife's illness. He used his first wife's encounter with spirit possessions to allude to the illness and behavioral changes of his second wife:

C: My partial understanding is that in Vietnam, this woman [caregiver's first wife] was rich and well-off, so the spirit took over and possessed her, and it caused her to be in pain and ill. She was taken over/possessed by this thing and that thing. Because a person with enough to eat -a rich person-, they don't have this man or woman bothering/possessing them. After the possession was done, there were times it harassed us horribly. Sometimes she ran all over the place, I almost died from following and looking for her. When she was no longer under the influence of the spirit, she was a normal person. The medium who is treating Mrs. Tran [caregiver's second wife] is a woman, the spirit is a young boy.

He describes an incident in which a spirit entered the body of another person who was praying beside his second wife, and correctly revealed to his second wife her diagnosis:

C: A while ago, I walked in and saw a thing -to use the women's words- called Uncle Vo. Don't know why, or who he is, or where he came from to enter her body (the body of the other person praying next to the caregiver's wife). When I came up and saw her worshipping with others...She prayed, turned to my wife and then suddenly correctly named the illness that my wife has. She said that my wife's two legs feel like they want to be cut off, are painfully aching, and said the body feels like it is being occupied by spirits, not like an alert and aware person.

This case illustrates religious or spiritual influences on the conception of illness that combines a belief in the malevolence of spirits, the curative power of spirits and Buddhist entities, as well as a Taoist and moral aesthetic inclined toward cultivating balance, inner peace or harmony. While Taoism is formally practiced as a religion in Vietnam, its presence –like that of Confucianism and ancestor worship- is so ingrained within Vietnamese culture, that its beliefs have become part of Vietnam's cultural fabric. As such, Tam may not align himself with one religion over another, but his practices and beliefs belie the influence of the many intertwined philosophies. He speaks of Western medicines making her temperament “hot” and has no compunctions about trying a combination of Eastern, Western and esoteric Vietnamese cures.

Orthodox followers of Taoism are said to eschew the more mystical sects of Taoism and shaman-like practices that Tam describes, in favor of strictly philosophical traditions. However, throughout the centuries, the practice of these more arcane beliefs have led to Vietnamese having at the very least, a watered-down concept of “hot” and “cold”, or “Yin” and “Yang” properties of food and the elements, such that it becomes futile to separate strands of religion from daily, cultural practice. Despite his stated desperation, these different strands of religion and their great and small influences allow Tam the caregiver to preserve some hope of a cure, at least for the moment.

DISCUSSION

Our findings are consistent with Geertz's definition of religion as establishing “powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations” (1973). The narratives above reveal how the multi-faceted Vietnamese moral-religious system serves as a resource for immigrant Vietnamese caregivers, and provides a set of cultural resources for ethnic Vietnamese to draw upon in managing personal suffering/distress, motivation for caregiving, and understanding the nature of illness itself. The extent to which these caregivers draw upon multiple strands of religion should be emphasized, and is also consistent with a wider literature on Vietnamese culture and religion (Taylor 2004; Malarney 2002; Jamison 1993). In his book Living Buddha, Living Christ (1995), the famous Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh states: “To me, religious life is life. I do not see any reason to spend one's whole life tasting just one kind of fruit. We human beings can be nourished by the best values of many traditions.”

The narratives highlighted two interesting ways in which caregivers incorporated religion and spirituality into their motivational scripts for caregiving. First, religious and spiritual frameworks motivated caregiving directly through a reference to “Karma” or “compassion.” Often, however, caregivers used religion and spirituality to reinforce the importance of “filial” behavior. In these cases, religion and spirituality operated through the construct of filial piety. In either case, religious and spiritual values are invoked within these stories to call attention to the moral status of the caregiver and/or the family with respect to the care that they provide. As moral stories, they simultaneously provide a window on day-to-day practices and experiences, and provide the narrator an opportunity to attest to their own moral status, and that of significant others in the world of the affected person. In this way, these stories often reveal in striking terms “what is at stake” (Kleinman 1988), or the important “concerns” (Traphagan 2004) for these families in caring for a family member with dementia.

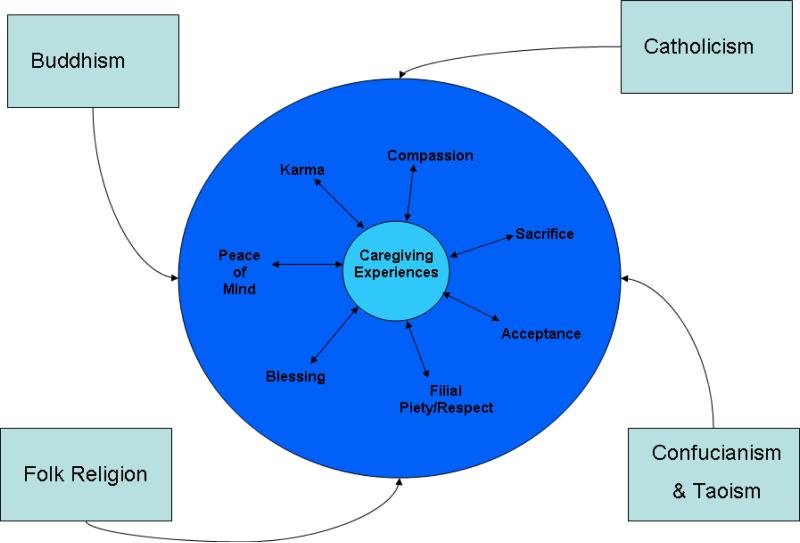

Our analysis identified key idioms and terms caregivers used to express the religious/spiritual dimensions of their caregiving experiences. These cultural idioms are important because they are more “experience-near” and provide a way of conceptualizing how religion and spirituality synchronize with the Vietnamese experience. These idioms exist as key nodes in what Good has referred to as semantic networks (Good 1977), connecting caregiving and illness processes, and the Vietnamese religious/spiritual complex as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Vietnamese religious/spiritual complex in relationship to key terms/idioms mediating the dementia caregiving experience

Further, several of the terms identified in this study, such as “compassion” or “sacrifice”, resonate with multiple religious/spiritual traditions. This may make these terms particularly useful and salient for caregivers in that they are able to symbolize or “hold” parallel strands of and represent various strands of the multi-faceted Vietnamese religious complex. In this sense, the terms are multi-vocal and their very ambiguity may be part of the reason for their prominence, as they powerfully convey the Vietnamese religious complex.

The availability of multiple strands of religion also has a pragmatic value in the context of the day-to-day lives of these Vietnamese refugees. One of the caregivers in this study, for example, used her discourse on evangelical Protestantism almost strategically in order to justify placing her mother in a convalescent home, and to resist her husbands “oppressive” demands that she care for his mother in the same filial manner. In this case, the internal contradictions of these different strands of religion provide opportunities to justify behaviors by social actors under certain circumstances. In addition, the father who invoked the concept of “sacrifice” in his narrative of caregiving was conveying the spiritual and religious dimensions of his experience, but also using his narrative to reinforce for his son, the importance of filial respect and piety. These examples underscore how meaning of the narratives cannot be understood apart from the sociocultural context in which they are constructed and articulated, and upon which they may have significant impacts (Good 1994).

The Vietnamese-religious complex described here has important implications for both research and clinical care. In terms of research, any attempt to quantify or measure religious orientations in a valid fashion for Vietnamese will need to account for the extent to which Vietnamese may simultaneously use frames—for example, Catholic and Buddhist—to make sense of their experience. Having Vietnamese “choose” one primary religious orientation over another is largely incompatible with the long history of religion and spirituality in Vietnam.

Much more valid from a cultural point of view, is a multidimensional approach that attempts to measure the extent to which these different strands of religion and spirituality are valued and practiced by the person. Ethnographic work may help us understand how caregivers make use of different strands of their religious tradition to motivate themselves in the task of caregiving. Health care providers, who treat such caregivers, and persons with dementia, need to understand these religious and spiritual strands in order to understand the illness experience at the level of the family, and to promote maximal care (Boehnlein 2006; Barnes et al 2000).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Carolee GiaoUyen Tran Ph.D., Hendry Ton M.D. and David Gellerman M.D, Ph.D. for comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. This research was supported by grants K23AG019809 (L. Hinton PI), P30AG010129 (C. DeCarli PI), and P30AG012057 (S. Levkoff PI) from the National Institute on Aging. This paper was presented at the 2007 Gerontological Society of American Meeting in San Francisco.

Contributor Information

Ladson Hinton, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences UC Davis Medical Center 2230 Stockton Blvd. Sacramento, CA 95817 ladson.hinton@ucdmc.ucdavis.edu

Jane NhaUyen Tran, Kaiser Permanente, San Francisco nhauyent@yahoo.com

Cindy Tran, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences UC Davis Medical Center 2230 Stockton Blvd. Sacramento, CA 95817 chtran@ucdavis.edu.

Devon Hinton, Department of Psychiatry Massachusetts General Hospital Boston, MA devon_hinton@hms.harvard.edu

REFERENCES

- Barnes LL, Plotnikoff GA, Fox K, Pendelton S. Spirituality, religion, and pediatrics: intersecting worlds of healing. Pediatrics. 2000;106:899–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth F. Enduring and emerging issues in the analysis of ethnicity. In: Vermeulen H, Grovers C, editors. The Anthropology of Ethnicity. Het Spinhius; Amsterdam: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Blagov S. Caodaism: Vietnamese Traditionalism and its Leap into Modernity. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Boehnlein JK. Religion and spirituality in psychiatric care: looking back, looking ahead. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2006;43(4):634–51. doi: 10.1177/1363461506070788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun KL, Takamura JC, Mougeot T. Perceptions of dementia, caregiving, and help-seeking among recent Vietnamese immigrants. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1996;11:213–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00122702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadière LM. Religious Beliefs and Practices of the Vietnamese. Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University; Australia: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- DiGregorio M, Salemink O. Living with the Dead: The politicis of ritual and remembrance in contemporary Vietnam. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 2007;38(3):433–440. [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams IC, Gibson BE. Issues of race, ethnicity, and culture in caregiving research: A 20-year review (1980-2000). The Gerontologist. 2002;42(2):237–272. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. The Interpretation of cultures. Basic Books Inc.; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdner LA, Tripp-Reimer T, Simpson HC. Hard Lives, God's Help, and Struggling Through: Caregiving in Arkansas Delta. Journal of Cross-cultural Gerontology. 2007;22(4) doi: 10.1007/s10823-007-9047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good B. The heart of what's the matter: The semantics of Illness in Iran. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 1977:25–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00114809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good B. Medicine, Rationality, and Experience: An Anthropological Perspective. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hanh TN. Vietnam: lotus in a sea of fire. Hill and Wang; New York, NY: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hanh TN. Living Buddha, Living Christ. Riverhead Books; New York, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson JN. Anthropology, Health and Aging. In: Rubinstein RL, Keith J, Shenk D, Wieland D, editors. Anthropology and Aging: Comprehensive Reviews. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Boston: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L. Improving care for ethnic minority elderly and their family caregivers across the spectrum of dementia severity. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2002;16(Suppl 2):S50–S55. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200200002-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pham T, Chau H, Tran M, Hinton S. ‘Hit by the wind’ and temperature-shift panic among Vietnamese refugees. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2003;40:342–376. doi: 10.1177/13634615030403003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Franz C, Yeo G, Levkoff S. Conceptions of dementia in a multi-ethnic sample of family caregivers. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2005;53:1405. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Guo Z, Hillygus J, Levkoff SE. Working with culture: A qualitative analysis of barrier to recruitment of Chinese-American family caregivers for dementia research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2000;15:119–137. doi: 10.1023/a:1006798316654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Kleinman A. Cultural Issues and International Psychiatric Diagnosis. In: Costa e Silva JA, Nadelson C, editors. International Review of Psychiatry. Vol. 1. American Psychiatric Association Press; Washington D.C.: 1993. pp. 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Levkoff SA, Fox K. Introduction: exploring the relationships among aging, ethnicity, and family dementia caregiving. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 1999;23:403–413. doi: 10.1023/a:1005514501883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson N. Understanding Vietnam. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Janevic MR, Connell CM. Racial, ethnic, and cultural differences in the dementia caregiving experience: recent findings. Gerontologist. 2001;41(3):334–347. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellema K. Everywhere incense burning: Remembering ancestors in Đổi Mới Vietnam. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 2007;38(3):467–492. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. The Illness Narratives. Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernández R. Cultural formulation of psychiatric diagnosis. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 1996;20:133–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00115858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KM. Traditional Chinese medical beliefs and their relevance for mental illness and psychiatry. In: Kleinman A, Lin TY, editors. Normal and abnormal behavior in Chinese culture. Reidel; Dordrecht, Netherlands: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Marlarney SK. Culture, Ritual and Revolution in Vietnam. Routledge; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Milne A, Chryssanthopoulou C. Dementia care-giving in Black and Asian populations: Reviewing and refining the research agenda. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology. 2005;15:319–337. [Google Scholar]

- Phan T, Silove D. An overview of indigenous descriptions of mental phenomena and the range of traditional healing practices amongst the Vietnamese. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1999;36(1):79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper K. The Taoist Body. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Spirago F, Clarke RF. The Cathechism Explained: An Exhaustive Exposition of the Catholic Religion. Tan Books and Publishers, INC.; Rockford, IL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tai HH. Millenarianism and peasant politics in Vietnam. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Tai HH. The Asia Society, Vietnam: essays on history, culture, and society. New York: 1985. Religion in Vietnam: a world of ghosts and spirits. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P. Goddess on the Rise: Pilgrimage and Popular Religion in Vietnam. University of Hawai'I Press; Honolulu: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Traphagan JW. The Practice of Concern. Carolina Academic Press; Durham, NC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Van DN. Religion and beliefs in Vietnam. Social Compass. 1995;42(3):345–365. [Google Scholar]

- Valle R, Lee B. Research priorities in the evolving demographic landscape of Alzheimer disease and associated dementias. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2002;16(Suppl 2):S64–76. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200200002-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G, Gallagher-Thompson D, editors. Ethnicity and the Dementias. Routledge; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G, Tran JNU, Hikoyeda N, Hinton L. Conceptions of dementia among Vietnamese American caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2001;36(1-2):131–152. [Google Scholar]