Abstract

Computer-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (CCBT) is emerging as a promising strategy for improving access to mental health services. Randomized controlled trials have confirmed the efficacy of guided CCBT in treating depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and other common mental disorders. With proper guidance, effect sizes are comparable to those obtained in face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy, treatment is cost-effective, and preliminary data indicate that CCBT is acceptable to patients. Trials are beginning to evaluate optimal strategies for integrating CCBT within existing systems of mental health care.

Introduction and context

Anxiety and depression are common mental disorders that affect 20% of the adult population annually [1] and result in a significant health burden. These conditions can be effectively treated with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) [2]. However, in a typical 12-month period, fewer than 50% of sufferers report seeking treatment from a health professional, and of these, only 50% receive evidence-based treatment [3]. Barriers to evidence-based treatment include direct and indirect costs, a shortfall in trained mental health clinicians (particularly in rural areas), difficulty attending treatment during usual office hours, and stigma. Strategies for reducing these barriers have considerable appeal.

Computer-delivered CBT (CCBT) is emerging as a technique that may help overcome barriers to access while increasing the capacity of existing mental health services to meet demand [4]. CCBT programs teach patients the same principles and techniques taught in face-to-face CBT. CCBT programs may be accessed at a medical centre or at home via an internet connection (internet-based CBT, or iCBT). The term CCBT will be used to describe both in this report.

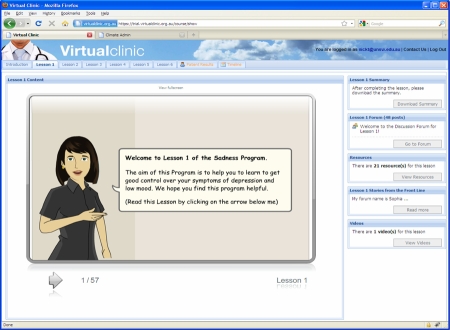

CCBT presents CBT in a highly structured format comprising a number of educational lessons, homework assignments, and supplementary resources via an engaging user interface (Figure 1). Because the computer presents time-consuming components of treatment (such as education), the clinician time required is often considerably less than in face-to-face treatment [5]. Programs are often administered with regular communication with a clinician via email, telephone, or online forums, but such programs may be integrated with face-to-face consultations [6]. Self-guided programs are also increasingly available, but clinician-guided programs or guidance by ‘technicians’ (non-health professionals supervised by clinicians) is superior on current evidence [7].

Figure 1. Lesson 1 from the VirtualClinic [29] Depression (Sadness) Program.

The program comprises lessons (providing structured psycho-education), arrows for navigation, homework/summary (to download, print, and save), online forums (moderated by clinicians), supplementary resources, stories from previous participants, video/multimedia clips, and has a secure internet connection.

The majority of studies of CCBT have been published in the past 5 years, but the use of computers to assist in administering psychological therapies began in the 1960s. This report summarizes recent data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the efficacy and effectiveness of clinician-assisted CCBT for depression and anxiety disorders.

Recent advances

Treatment of depression

RCTs have demonstrated the efficacy and reliability of clinician-assisted CCBT for people with depression [7-10]. One trial reported an effect size of 2.3 on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) following 8 weeks of CCBT treatment in which each patient received a total of 8 hours of therapist support compared with an effect size of 0.7 in the waitlist control group [8]. Importantly, a large effect size (1.5) was also found in a guided self-help condition, which required less than 1 hour of therapist support, indicating the potential cost-effectiveness of the program [8]. Other RCTs have reported a within-groups effect size of 1.6 on the BDI following 11 weeks of CCBT [9] and a within-groups effect size of 1.1 on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) following 8 weeks of CCBT [10]. In comparison, smaller but significant effect sizes were recently reported for self-guided programs [11]. Despite their lower effect sizes, self-guided programs may be particularly helpful for people with mild to moderate symptoms who cannot (or do not wish to) see a clinician, although dropout rates are also higher in self-guided programs.

Treatment of anxiety

The efficacy and reliability of clinician-assisted CCBT have recently been demonstrated for generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social phobia. One RCT of CCBT for generalized anxiety disorder reported an effect size of 1.0 on the Penn State Worry Questionnaire following 10 weeks of treatment compared with 0.0 in the waitlist control group [12]. In patients with panic disorder, clinically significant improvements have been reported following treatment with an internet-based CCBT program [13,14], with equivalent results obtained by people with panic disorder treated either via the internet or face to face [13] and equivalent results for those treated by a clinical psychologist or a primary care physician trained in psychological techniques [14]. Robust and reliable clinically significant improvements have also been reported by several independent research teams treating people with social phobia by means of internet-based CCBT [15-19]. In a Swiss study, patients with social phobia experienced clinically significant reductions in symptoms following 10 weeks of treatment [15]. Research teams based in Sweden and Australia have independently conducted trials exploring the efficacy of clinician-assisted or self-guided CCBT for social phobia. More than seven RCTs by these groups with more than 700 patients have consistently revealed clinically significant improvements in adults with social phobia following treatment [16-19], and recent RCTs have revealed that clinically significant improvements can be obtained when programs are guided by non-health professionals who are supervised by clinicians [18,19].

Other issues

Important questions include the effectiveness of CCBT when directly compared with face-to-face treatment, the longevity of benefits, demographic characteristics of patients, and cost-effectiveness: RCTs directly comparing face-to-face with CCBT programs have reported equivalent results [7,20]. The results of CCBT are sustained at follow-ups, with one study indicating that results are sustained at 30-month follow-up [21]. A comparison between people with anxiety and depression identified in an epidemiological survey and patients receiving internet-based treatment or those attending an outpatient treatment clinic found that the internet-based treatment group were a similar age to the survey sample and had disorders that were as severe as those attending the outpatient clinic [22]. Cost-effectiveness analyses indicate that these programs are significantly less expensive than face-to-face treatment, and emerging evidence indicates that CCBT is acceptable to patients [23].

Implications for clinical practice

A rapidly growing body of evidence supports the efficacy and effectiveness of CCBT for anxiety and depression. In the context of a worldwide shortage of therapists, large numbers of untreated people, difficulty attending treatment during usual business hours, and stigma, such programs have considerable potential. Federal governments in several countries, including Australia, Holland, and England, are now funding large-scale trials or have begun implementing CCBT programs for anxiety and depression. For example, in the UK, two CCBT programs are funded by the National Health Service for delivering CBT in the management of mild to moderate depression, panic, and phobia, within stepped-care management programs [24,25]. In Holland, therapist-guided CCBT is accepted as a valid alternative to face-to-face psychotherapy. However, an obvious question is how to integrate CCBT into existing mental health services.

Several models of service delivery are possible, ranging from entirely self-guided programs to entirely clinician-guided. To help address the massive waiting lists for mental health care, self-guided or technician- or clinician-assisted CCBT (completed either at a computer in the outpatient clinic or at home) programs are being employed within stepped-care models as a first-level treatment option, with technician- or clinician-assisted CCBT (completed either at a computer in the outpatient clinic or at home) as a second step and face-to-face treatment as a subsequent step. It is likely that participation in earlier steps will potentiate subsequent treatment, but the results of this research are still pending. Preliminary data from trials in primary care indicate that assisted CCBT [26] results in outcomes that are superior to those of self-guided programs [27].

Hurdles to successful implementation include the need for reliable software, hardware, and internet connections in addition to those hurdles already identified in the implementation of evidence-based practice [28]. Appropriate, safe, and ethical data management protocols need to be standardized, legislation about registration of clinicians working across federal or state and territory borders needs to be clarified, and sensible strategies for working with suicidal clients need to be tested.

In summary, the potential of CCBT programs to extend the capacity of existing mental health services is considerable. Careful attention must be paid to evaluating models of intervention to realise this potential.

Abbreviations

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

- CBT

cognitive behavioural therapy

- CCBT

computer-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found at: http://f1000.com/reports/m/2/49

References

- 1.Australian Bureau of Statistics: National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing 2007: Summary of Results; 23 October 2008. [ http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/6AE6DA447F985FC2CA2574EA00122BD6/$File/43260_2007.pdf]

- 2.Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT. The empirical status of cognitive behavioural therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews G, Issakidis C, Sanderson K, Corry J, Lapsley H. Utilising survey data to inform public policy: comparison of the cost-effectiveness of treatment of ten mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:526–33. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.6.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marks I, Cavanagh K, Gega L. Hands-On Help: Computer-Aided Psychotherapy. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks I, Cavanagh K. Computer-aided psychological treatments: evolving issues. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:121–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barak A, Klein B, Proudfoot JG. Defining internet-supported therapeutic interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38:4–17. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38:196–205. doi: 10.1080/16506070903318960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.0 RecommendedEvaluated by Perminder Sachdev 4 May 2010

- 8.Vernmark K, Lenndin J, Bjärehed J, Carlsson M, Karlsson J, Öberg J, Carlbring P, Eriksson T, Andersson G. Internet administered guided self-help versus individualized e-mail therapy: a randomized trial of two versions of CBT for major depression. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:368–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruwaard J, Schrieken B, Schrijver M, Broeksteeg J, Dekker J, Vermeulen H, Lange A. Standardized web-based cognitive behavioural therapy of mild to moderate depression: a randomized controlled trial with a long-term follow-up. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;16:1–16. doi: 10.1080/16506070802408086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warmerdam L, van Straten A, Twisk J, Riper H, Cuijpers P. Internet-based treatment for adults with depressive symptoms: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e44. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer B, Berger T, Caspar F, Beevers CG, Andersson G, Weiss M. Effectiveness of a novel integrative online treatment for depression (Deprexis): randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e15. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Titov N, Andrews G, Robinson E, Schwencke G, Johnston J, Solley K, Choi I. Clinician-assisted Internet-based treatment is effective for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43:905–12. doi: 10.1080/00048670903179269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiropoulos LA, Klein B, Austin DW, Gilson K, Pier C, Mitchell J, Ciechomski L. Is internet-based CBT for panic disorder and agoraphobia as effective as face-to-face CBT? J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:1273–84. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shandley K, Austin DW, Klein B, Pier C, Schattner P, Pierce D, Wade V. Therapist-assisted, Internet-based treatment for panic disorder: can general practitioners achieve comparable patient outcomes to psychologists? J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e14. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger T, Hohl E, Caspar F. Internet-based treatment for social phobia: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychology. 2009;65:1–15. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlbring P, Gunnarsdóttir M, Hedensjö L, Andersson G, Ekselius L, Furmark T. Treatment of social phobia: randomised trial of internet-delivered cognitive-behavioural therapy with telephone support. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:123–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Titov N, Andrews G, Choi I, Schwencke G, Mahoney A. Shyness 3: randomized controlled trial of guided versus unguided Internet-based CBT for social phobia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:1030–40. doi: 10.1080/00048670802512107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Titov N, Andrews G, Choi I, Schwencke G, Johnston L. Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for social phobia without clinical input is effective: a pragmatic RCT of two types of reminders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43:913–9. doi: 10.1080/00048670903179160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Titov N, Andrews G, Schwencke G, Solley K, Johnston L, Robinson E. An RCT comparing effect of two types of support on severity of symptoms for people completing Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for social phobia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43:920–6. doi: 10.1080/00048670903179228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuijpers P, Marks IM, van Straten A, Cavanagh K, Gega L, Andersson A. Computer-aided psychotherapy for anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38:66–82. doi: 10.1080/16506070802694776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.0 RecommendedEvaluated by Perminder Sachdev 4 May 2010

- 21.Carlbring P, Nordgren LB, Furmark T, Andersson G. Long term outcome of Internet delivered cognitive-behavioural therapy for social phobia: a 30-month follow-up. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:848–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Titov N, Andrews G, Kemp A, Robinson E. Characteristics of adults with anxiety or depression treated at an Internet clinic: comparison with a national survey and an outpatient clinic. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaltenthaler E, Sutcliffe P, Parry G, Beverley C, Rees A, Ferriter M. The acceptability to patients of computerized cognitive behaviour therapy for depression: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1521–30. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Computerised Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (cCCBT) Implementation Guidance. London, UK: Department of Health; Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) Program. 1 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety (Review of Technology Appraisal 51; Technology Appraisal 97) [ http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA97]

- 26.Learmonth D, Trosh J, Rai S, Sewell J, Cavanagh K. The role of computer-aided psychotherapy within an NHS CBT specialist service. Couns Psychother Res. 2008;8:117–23. doi: 10.1080/14733140801976290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Graaf LE, Huibers MJH, Riper H, Gerhards SAH, Arntz A. Use and acceptability of unsupported online computerized cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and associations with clinical outcome. J Affect Disord. 2009;116:227–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinfeld BI, Coffman SJ, Keyes JA. Implementation of evidence-based practice in a clinical setting: what happens when you get there? Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2009;40:410–6. doi: 10.1037/a0015677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. VirtualClinic homepage. [ http://www.virtualclinic.org.au] [Google Scholar]