Abstract

Conduct problems, substance use, and risky sexual behavior have been shown to coexist among adolescents, which may lead to significant health problems. The current study was designed to examine relations among these problem behaviors in a community sample of children at high risk for conduct disorder. A latent growth model of childhood conduct problems showed a decreasing trend from grades K to 5. During adolescence, four concurrent conduct problem and substance use trajectory classes were identified (high conduct problems and high substance use, increasing conduct problems and increasing substance use, minimal conduct problems and increasing substance use, and minimal conduct problems and minimal substance use) using a parallel process growth mixture model. Across all substances (tobacco, binge drinking, and marijuana use), higher levels of childhood conduct problems during kindergarten predicted a greater probability of classification into more problematic adolescent trajectory classes relative to less problematic classes. For tobacco and binge drinking models, increases in childhood conduct problems over time also predicted a greater probability of classification into more problematic classes. For all models, individuals classified into more problematic classes showed higher proportions of early sexual intercourse, infrequent condom use, receiving money for sexual services, and ever contracting an STD. Specifically, tobacco use and binge drinking during early adolescence predicted higher levels of sexual risk taking into late adolescence. Results highlight the importance of studying the conjoint relations among conduct problems, substance use, and risky sexual behavior in a unified model.

Keywords: conduct problems, substance use, risky sexual behavior, latent growth model, parallel process growth mixture model

1. Introduction

Problem behavior is any “behavior that is socially defined as a problem, source of concern, or undesirable by the norms of conventional society” (Jessor and Jessor, 1977, p. 33). Engagement in some conduct problems and substance use are expectable manifestations of adolescent development. Yet these behaviors may presage the beginning of a serious problem behavior trajectory, including severe delinquency, substance use disorders, and increased risk for sexually-transmitted diseases (STDs; Paul, Fitzjohn, Herbison, and Dickson, 2000). Although it is known that conduct problems, substance use, and risky sexual behaviors co-occur, the extent of co-occurrence and developmental sequence of these behaviors are not well understood (Krueger, Markon, Patrick, Benning, and Kramer, 2007). The goal of the current study was to examine relations of these problem behaviors in children from grades K to 12.

Conduct problems constitute a broad range of acting-out behaviors, including violence, physical destruction, and stealing (McMahon, Wells, and Kotler, 2006). Most children show decreasing frequencies of conduct problems as a function of age (Campbell, Shaw, and Gilliom, 2000), despite a relatively small group of children who show clinically elevated symptoms into adolescence (Nagin and Tremblay, 2001). Children in this latter group are thought to be at increased risk for conduct problems that are more serious and impervious to treatment (Moffitt, 1993). The societal costs associated with conduct problems, including direct harm to victims and costs of incarceration, are staggering (Cohen, 1998).

A number of studies have established a strong relation between adolescent conduct problems and substance use (e.g., Armstrong and Costello, 2002; Moffitt et al., 2008). Among adolescents who engage in both conduct problems and substance use, conduct problems typically precede initiation into substance use (Le Blanc and Loeber, 1998). The consequences of problematic substance use are far reaching and present a serious public health problem (Adams, Blanken, Ferguson, and Kopstein, 1990), including high costs in health care, educational failure, and juvenile crime (Hawkins, Catalano, and Miller, 1992). In terms of costs to society, adolescent crimes that involve substance use accounted for over $6.5 billion in medical and mental heath care expenses in 1999 alone (Miller, Levy, and Cohen, 2006).

Theorists have linked adolescent conduct problems and substance use with risky sexual behaviors (Jessor, Donovan, and Costa, 1991; Petraitis, Flay, and Miller, 1995). Risky sexual behaviors, defined as having sex at an early age, infrequent condom use, receiving money for sexual services, and contracting STDs (Repetti, Taylor, and Seeman, 2002), have been shown to be developmentally preceded by adolescent conduct problems and substance use (Biglan, Brennan, Foster, and Holder, 2004). Individuals from ages 13 to 24 accounted for 15% of reported HIV cases and the proportion of adolescents who acquire HIV as a result of substance use has increased within the last two decades (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998).

Few prospective studies have addressed temporal relations among all three problem behaviors. King, Iacono, and McGue (2004) identified patterns of childhood conduct problems that predicted adolescent substance use but did not examine risky sexual behavior. Guo and colleagues (2002) found that risky sexual behavior correlated with substance use trajectories but did not incorporate conduct problems. Ramrakha and colleagues (2007) found that higher levels of childhood conduct problems were associated with increased odds of early sexual intercourse but did not examine substance use.

To our knowledge, only one study has examined these three problem behaviors in a single model. Schofield, Bierman, Heinrichs, Nix, and Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (CPPRG; 2008) examined these behaviors in a subset of panel data from the Fast Track Project (CPPRG, 1992) using path analyses. The authors found that conduct problems assessed from grades K to 1 predicted substance use at grade 7. In turn, greater substance use predicted higher levels of later sexual activity, defined by age of initiation and years of sexual intercourse from grades 7 to 11.

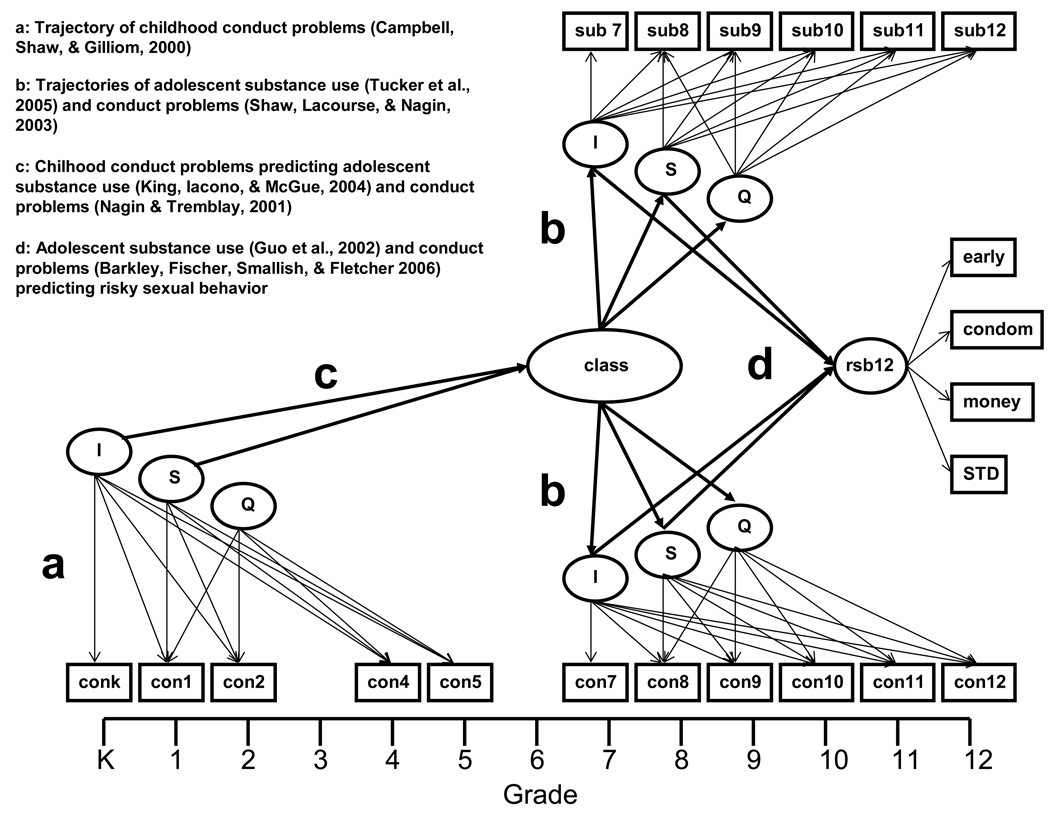

In the current study, using a sub-sample of participants in the Fast Track Project (CPPRG, 1992), we extend the research of Schofield and colleagues (2008) by examining longitudinal relations among conduct problems, substance use, and risky sexual behavior. Four research questions were addressed (see Figure 1). How do conduct problems evolve during childhood? Can we identify individual variation in the comorbid development of conduct problems and substance use during adolescence? Longitudinal trajectories of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use were modeled separately from grades 7 to 12. How does the development of childhood conduct problems affect subsequent trajectories of adolescent conduct problems and substance use? Finally, how does the development of adolescent conduct problems and substance use affect risky sexual behavior measured during late adolescence? We extended the definition of risky sexual behavior as “sexual intercourse between grades 7 and 11” by Schofield and colleagues to include three additional indicators of risky sexual behavior: condom use frequency, receiving money for sex, and contracting STDs.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model of the current study. Con = Conduct problems; Sub = Substance use (tobacco, binge drinking, and marijuana use modeled separately); and Rsb = Risky sexual behavior.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants and Design

The current study used data from a community-based sample of children at high risk for conduct disorder drawn from the Fast Track project, a multi-site investigation of the development and prevention of conduct problems (CPPRG, 1992). Schools within four sites (Durham, NC; Nashville, TN; rural Pennsylvania; and Seattle, WA) were identified as high-risk based on crime and poverty statistics. Within each site, schools were divided into sets matched for demographics and randomly assigned to control and intervention groups. Using the Teacher Observation of Child Adjustment-Revised Authority Acceptance score (Werthamer-Larsson, Kellam, and Wheeler, 1991), 9,594 kindergarteners from 55 schools were screened for classroom conduct problems. Those scoring in the top 40% were then solicited for home behavior problems by parents using items from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) and similar scales, and 91% agreed to participate (n = 3,274). Children were selected for inclusion into the study based on this screening, moving from the highest score downward until desired sample sizes were reached. The outcome was that 891 children (446 control and 445 intervention) participated. The current study used children from the high-risk control group.

In this high-risk sample, 62 participants were missing data on all conduct problem, substance use, and risky sexual behavior measures, reducing the study sample to 384. The 62 attrited participants did not differ on any demographic or dependent variable relative to the 384 participants included in analyses. Of the 384, about one-quarter came from each of the four sites, 32.6% were female, 50.3% were African-American, and most were 5 years old during the initial assessment at kindergarten. A complete list of assessments can be found at http://www.fasttrackproject.org.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Childhood conduct problems

The Externalizing scale of the CBCL (Achenbach, 1991) was used to assess childhood conduct problems. This scale consists of 12 delinquent and 20 aggressive behaviors (one item concerning youth substance use was excluded1). Externalizing T-scores were standardized separately for boys and girls based on a nationally-representative sample and were obtained at grades K, 1, 2, 4, and 5. The reliability of the CBCL Externalizing scale was acceptable (average α across time = .88).

2.2.2 Adolescent conduct problems

The Self-Reported Delinquency measure (SRD; Huizinga and Elliott, 1986) was used to assess adolescent conduct problems. Participants described their delinquent activities (e.g., property damage and theft) and were asked if they committed the act in the past year (0 = no, 1 = yes). Of the 34 original items, 9 minor offenses (e.g., skipping class) and 1 risky sexual behavior item (receiving money for sexual services) were excluded, leaving 24 items that indexed serious conduct problems. A summary score was computed by taking the mean of the 24 items. SRD scores were obtained annually from grades 7 to 12. The reliability of the SRD was acceptable (average α across time = .83).

2.2.3 Adolescent substance use

Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drugs (TAD; CPPRG, 2004) is a revised version of the substance use section of the NLSY97 Self-Administered Youth Questionnaire (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2002) and was used to assess adolescent substance use. Three binary TAD items were examined: (a) any tobacco use in the past month, (b) any binge drinking (five or more consecutive drinks in one session) in the past year, and (c) any marijuana use in the past month. TAD scores were obtained annually from grades 7 to 12.

2.2.4 Adolescent risky sexual behaviors

Sexuality and Consequences (SC; Bearman, Jones, and Udry, 1997) is a 40-item questionnaire designed to assess respondents’ sexual activity. Three items were taken from the SC (assessed at grade 12) and one item was taken from the SRD. Research has suggested that these items serve as reasonable indices of risky sexual behavior: (a) early onset of sexual intercourse (Capaldi, Crosby, and Stoolmiller, 1996), (b) infrequent condom use (Sonenstein, Ku, Lindberg, Turner, and Pleck, 1998), (c) receiving money for sexual services (Wilson and Widom, 2008), and (d) contracting an STD (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2002). A binary variable for early onset sexual intercourse was created (0 = never had sex or first had sex at age 17 or older; 1 = first had sex at age 16 or younger). Past year condom use frequency was dichotomized into a binary variable (0 = most of the time or always, 1 = sometimes or never). Received money for sexual services during grades 7 to 12 and ever contracted an STD in lifetime were also treated as binary variables (0 = no, 1 = yes). These four variables were combined to form a composite risky sexual behavior variable. A participant received a “1” (i.e., risk present) on the composite variable if he or she endorsed any one of the above-listed criteria and “0” if none of the criteria were endorsed.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Analyses included several modeling procedures described below, which have been employed successfully in previous studies of problem behavior (e.g., Auerbach and Collins, 2006; Wiesner and Windle, 2004). Mplus version 5.1 (Muthén and Muthén, 2007) was used to estimate all models. Mplus uses the expectation-maximization algorithm (Allison, 2002) to obtain maximum likelihood estimates with robust standard errors, an accepted approach to handle missingness when data are missing at random (Little and Rubin, 2002). Significance tests were assessed at alpha = .05.

The first step (a in Figure 1) was to describe the trajectory of childhood conduct problems using CBCL Externalizing T-scores at grades K, 1, 2, 4, and 5 as indicators in a latent growth model (LGM; Duncan and Duncan, 2004). Three unconditional LGMs were tested: (a) intercept only, (b) intercept and linear slope, and (c) intercept, linear, and quadratic slope. The model that best fitted the data according to the root-mean-square error of approximation (i.e., RMSEA ≤ .08) and comparative fit index (i.e., CFI ≥ .90) was selected.

A parallel process growth mixture model (GMM; Greenbaum and Dedrick, 2007) was used to describe the concurrent relation between conduct problems and substance use (tobacco use, binge drinking, and marijuana use modeled separately) from grades 7 to 12 (b in Figure 1). The latent class variable was defined by both conduct problem and substance use growth factors. We estimated models with one to five classes and the fit of these models was assessed with three common indices (Bauer and Curran, 2003): (a) Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwartz, 1978), (b) sample-size adjusted BIC (SSABIC; Sclove, 1987), and (c) bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT; McLachlan and Peel, 2000). Lower values of BIC and SSABIC indicate a better fitting model (Muthén, 2004). A significant BLRT χ2 value (p < .05) indicates that the specified model fits the data better than the specified model with one less class (Nylund, Asparouhov, and Muthén, 2007).

After selecting the optimal model, class membership was regressed on childhood conduct problem growth factors (c in Figure 1), while controlling for baseline covariates (cohort, site, gender, and race). These analyses were conducted in order to examine how conduct problems in kindergarten (intercept) and increase in childhood conduct problems over time (slope) influenced the odds of expected membership to a particular latent class during adolescence.

The risky sexual behavior composite variable was allowed to vary across class in each model. A χ2 test was performed to assess differences in the proportion endorsing risky sexual behavior across each class. Risky sexual behavior was also estimated as a continuous latent variable using the four indicators (d in Figure 1). This latent variable was regressed on adolescent substance use and conduct problem growth factors, while controlling for baseline covariates and childhood conduct problems.

2.4 Missing Data

The range of missing data out of 384 participants included in the analyses was as follows: (a) CBCL: n = 3–25 (1%–7%) missing from grades K to 5; (b) SRD: n = 30–78 (8%–20%) missing from grades 7 to 12; (c) TAD: n = 28–76 (7%–19%) missing from grades 7 to 12; and (d) SC: n = 68 (18%) missing at grade 12. There were no significant differences between missing and non-missing cases on any baseline covariates.

3. Results

Childhood conduct problem trajectories from grades K to 5 were estimated using a LGM. The quadratic model2 provided the best fit to the data (RMSEA = .08 and CFI = .97). Participants started kindergarten with CBCL T-scores around 61 (normative average = 50) and decreased slightly but never reached the average by the end of grade 5 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Dependent Variables (n = 384)

| Grade K | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean CBCL a | 61.15 (8.58) | 62.48 (9.22) | 60.18 (9.74) | 57.78 (11.14) | 56.31 (11.43) | |

| Grade 7 | Grade 8 | Grade 9 | Grade 10 | Grade 11 | Grade 12 | |

| Mean SRD b | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.10) | 0.04 (0.09) | 0.03 (0.08) | 0.04 (0.09) |

| Any Tobacco Use | .21 | .23 | .31 | .32 | .42 | .50 |

| Any Binge Drinking | .07 | .11 | .15 | .21 | .21 | .29 |

| Any Marijuana Use | .06 | .09 | .16 | .16 | .20 | .23 |

| Risky Sexual Behavior | .65 | |||||

| Early Sex | .62 | |||||

| Infrequent Condom Use | .32 | |||||

| Received Money for Sex | .08 | |||||

| Ever Contracted STD c | .07 | |||||

Note. For mean scores, SD is presented in parentheses; all other statistics are proportions.

CBCL = Childhood Behavior Checklist Externalizing T-score (range of skewness = −.28 to .07 & kurtosis = −.22 to .03)

SRD = Self-Reported Delinquency (range of skewness = 3.05 to 5.53 & kurtosis = 12.56 to 31.24)

STD = Sexually transmitted disease

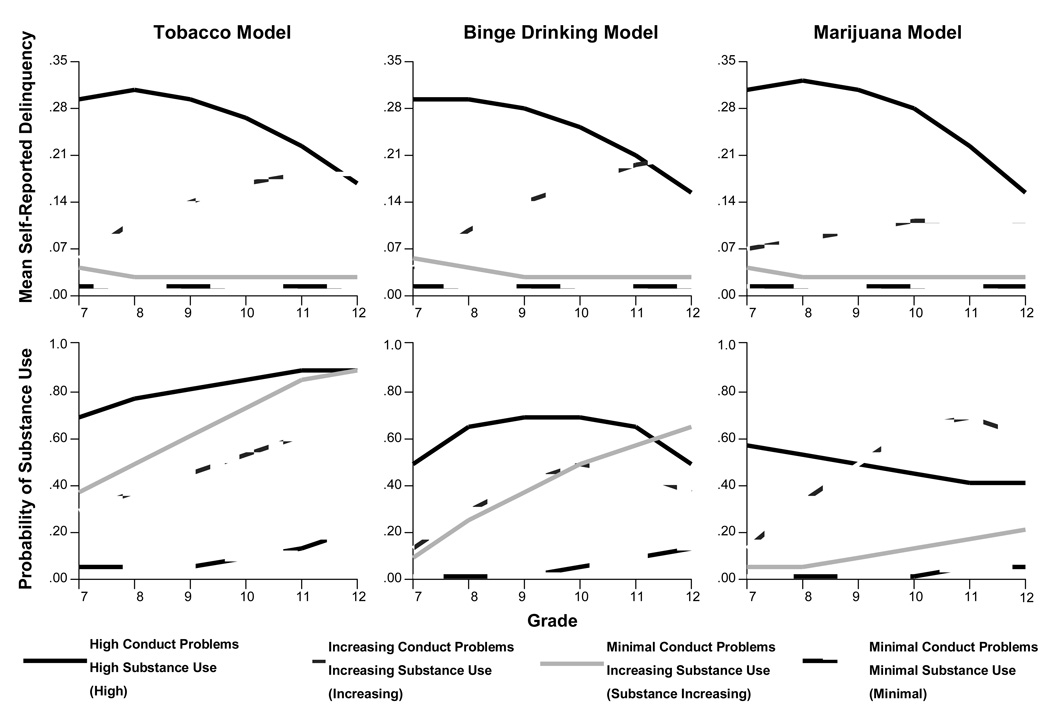

We estimated the parallel growth processes of adolescent conduct problems and substance use for tobacco, binge drinking, and marijuana in three separate models using GMM.3 Unconditional models were estimated to examine relative model fit across class enumerations. Across all substances, the four-class model provided a better fit than one- to three-class models and adding a fifth class did not significantly improve model fit (see Table 2). Figure 2 shows the estimated trajectories of the four-class parallel process GMMs, which were: (a) high conduct problems and high substance use (high), (b) increasing conduct problems and increasing substance use (increasing), (c) minimal conduct problems and increasing substance use (substance increasing), and (d) minimal conduct problems and minimal substance use (minimal).

Table 2.

Model Fit Indices of Unconditional Parallel Process Growth Mixture Models (n = 384)

| Tobacco Model | Binge Drinking Model | Marijuana Model | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | ka | LLb | BICc | SSABICd | BLRTe | k | LL | BIC | SSABIC | BLRT | k | LL | BIC | SSABIC | BLRT |

| One | 12 | −5347 | 10765 | 10727 | - | 12 | −5008 | 10087 | 10049 | - | 12 | −4948 | 9969 | 9931 | - |

| Two | 19 | −5046 | 10205 | 10144 | .000 | 19 | −4699 | 9511 | 9454 | .000 | 19 | −4647 | 9408 | 9348 | .000 |

| Three | 26 | −4881 | 9918 | 9835 | .000 | 26 | −4608 | 9371 | 9288 | .000 | 26 | −4538 | 9231 | 9148 | .000 |

| Four | 33 | −4800 | 9797 | 9693 | .000 | 33 | −4532 | 9261 | 9156 | .000 | 33 | −4460 | 9117 | 9012 | .000 |

| Five | 40 | −4722 | 9682 | 9555 | .182 | 40 | −4457 | 9152 | 9025 | .084 | 40 | −4406 | 9051 | 8924 | .076 |

k = Parameters

LL = Log-likelihood

BIC = Bayesian information criterion

SSABIC = Sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion

BLRT = Bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (p-value)

Figure 2.

Estimated trajectories for the four-class parallel process conduct problems and substance use growth mixture models (n = 384)

Table 3 shows expected class proportions and model estimated means/proportions of covariates. Class proportions were similar across tobacco and binge drinking models with the majority of participants expected in the minimal class. The substance increasing class was the second most representative based on class proportions for tobacco and binge drinking models, but was the largest class for the marijuana model. Across all substances, the high classes had the smallest class proportions and the increasing classes had the next smallest class proportions.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the Four-Class Parallel Process Growth Mixture Model (n=384)

| Tobacco Model | Binge Drinking Model | Marijuana Model | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H a | I b | SI c | M d | H | I | SI | M | H | I | SI | M | |

| N | 16 (4.1%) |

29 (7.7%) |

132 (34.3%) |

207 (53.9%) |

16 (4.1%) |

23 (5.8%) |

96 (25.1%) |

249 (65.0%) |

15 (3.9%) |

58 (15.1%) |

193 (50.3%) |

118 (30.7%) |

| Female | 1 (6.3%) |

3 (10.3%) |

39 (29.5%) |

82 (39.6%) |

1 (6.3%) |

4 (17.4%) |

25 (26.0%) |

95 (38.2%) |

1 (6.7%) |

8 (13.8%) |

82 (42.5%) |

34 (28.8%) |

| African- American |

9 (56.3%) |

15 (51.7%) |

44 (33.3%) |

125 (60.4%) |

9 (56.3%) |

12 (52.2%) |

30 (31.3%) |

142 (57.0%) |

9 (60.0%) |

31 (53.4%) |

114 (59.1%) |

39 (33.1%) |

| ICBC e | 64.78 | 61.94 | 62.60 | 60.77 | 64.78 | 62.68 | 61.84 | 61.24 | 65.32 | 61.13 | 61.60 | 61.43 |

| SCBC f | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.41 | −0.14 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.46 | −0.07 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.31 | −0.05 |

| RSB g | 1.00 | .83 | .76 | .53 | 1.00 | .77 | .75 | .56 | 1.00 | .75 | .96 | .03 |

| Early | .82 | .85 | .76 | .49 | .82 | .80 | .77 | .54 | .80 | .77 | .88 | .00 |

| Condom | .75 | .38 | .37 | .25 | .75 | .50 | .33 | .27 | .71 | .39 | .36 | .00 |

| Money | .50 | .13 | .09 | .03 | .50 | .16 | .09 | .04 | .54 | .19 | .04 | .03 |

| STD | .27 | .04 | .11 | .03 | .27 | .05 | .11 | .05 | .30 | .09 | .09 | .07 |

H = High conduct problems and high substance use class

I = Increasing conduct problems and increasing substance use class

SI = Minimal conduct problems and increasing substance use class

M = Minimal conduct problems and minimal substance use class

ICBC = Mean intercept of CBCL LGM

SCBC = Mean slope of CBCL LGM

RSB = Risky sexual behavior composite variable (proportion of endorsing any risky sexual behavior): (a) Early = proportion of having sex before age 17; (b) Condom = proportion of infrequent condom use when having sex in past year (0 = most of the time or always, 1 = never or sometimes); (c) Money = proportion of receiving money for sex during grades 7–12; and (d) STD = proportion of ever contracting a sexually transmitted disease (STD) in lifetime

Logistic regressions of class membership on intercept and slope of childhood conduct problems were conducted, while controlling for site, cohort, gender, and race. For tobacco and binge drinking models, females had lower odds, OR = 0.08 (95% CI = 0.01–0.81) and OR = 0.09 (95% CI = 0.01–0.85), respectively, for being in the high class relative to the minimal class. For the marijuana model, being female was associated with lower odds, OR = 0.06 (95% CI = 0.01–0.63) of expected membership in the high class relative to the substance increasing class. Race had a significant effect in the marijuana model, where African Americans (compared to European Americans) had greater odds, OR = 4.01 (95% CI = 1.09–14.71) of expected class membership in the increasing class relative to the minimal class.

Participants with greater childhood conduct problem intercepts were more likely to be in the high class relative to the minimal class for the tobacco model, the increasing class for the binge drinking model, and the minimal, substance increasing, and increasing classes for the marijuana model (see Table 4). Participants with greater childhood conduct problems slopes were more likely to be in the high and substance increasing classes relative to the minimal class for the tobacco and binge drinking models. No other regressions were significant.

Table 4.

Class Membership Logistic Regressions on Childhood Conduct Problem Growth Factors (n = 384)

| Tobacco Model High |

Binge Drinking Model High |

Marijuana Model High |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICBC d | SCBC e | ICBC | SCBC | ICBC | SCBC | |

| M a | 1.23 (1.02–1.47) | 6.01 (1.45–24.95) | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) | 4.99 (1.22–20.08) | 1.26 (1.08–1.46) | 0.94 (0.26–3.35) |

| SI b | 1.07 (0.95–1.20) | 2.22 (0.50–9.91) | 1.09 (0.97–1.22) | 2.08 (0.44–9.78) | 1.18( 1.05–1.27) | 0.73 (0.21–2.53) |

| I c | 1.06 (0.92–1.23) | 1.37 (0.14–13.41) | 1.30 (1.11–1.64) | 1.23 (0.16–9.47) | 1.22 (1.07–1.33) | 0.51 (0.12–2.17) |

| Substance Increasing | Substance Increasing | Substance Increasing | ||||

| ICBC | SCBC | ICBC | SCBC | ICBC | SCBC | |

| M | 1.02 (0.95–1.09) | 2.69 (1.33–5.43) | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | 2.39 (1.02–5.47) | 0.98 (0.92–1.05) | 1.30 (0.77–2.21) |

Note: Row = reference class, column = target class; Estimates are expressed as odds ratios (95% CI) of being in target class relative to reference class for unit increase in growth factor. Significant (p<.05) odds ratios are in bold. No regressions involving the I class as the target class was significant.

M = Minimal conduct problems and minimal substance use class

SI = Minimal conduct problems and increasing substance use class

I = Increasing conduct problems and increasing substance use class

ICBC = Intercept of CBCL LGM

SCBC = Slope of CBCL LGM

We evaluated differences in risky sexual behavior across classes using posterior-probability based class-estimated means. The proportion of members endorsing risky sexual behavior differed across classes for the tobacco, χ2(3) = 159.69, p < .01, binge drinking, χ2(3) = 122.82, p < .01, and marijuana model, χ2(3) = 151.52, p < .01 (see Table 3). For tobacco and binge drinking models, proportion of members endorsing risky sexual behavior increased from the minimal to substance increasing to increasing to high class. For the marijuana model, more participants in the substance increasing class exhibited higher proportions of risky sexual behavior relative to the increasing class. Of the four individual risky sexual behavior indicators, the early sex variable distinguished those expected in the minimal class relative to the other classes, whereas the condom use, receive money for sex, and STD variables distinguished those expected in the high class relative to the other classes.

Fit of the latent risky sexual behavior measurement model was adequate, χ2 (7) = 11.06, p = .14). Risky sexual behavior was regressed on adolescent tobacco use, binge drinking, marijuana use, and conduct problem growth factors, while controlling for baseline covariates and childhood conduct problems. Risky sexual behavior was significantly related to the tobacco use intercept (β = .62, p < .01, r = .46) and binge drinking intercept (β = .59, p < .01, r = .37). No other regressions were significant. Follow-up analyses were conducted to examine potential moderating effects of gender on the relation between tobacco use and binge drinking intercept and individual risky sexual behavior items. Logistic regressions for each sexual risk item indicated that tobacco use intercept predicted early sexual intercourse, β = .20, p = .02, OR = 1.57 (95% CI = 1.08–2.29) and ever having an STD by grade 12, β = .23, p = .02, OR = 1.77 (95% CI = 1.08–2.92). Gender moderated the relationship between tobacco use and binge drinking intercepts and grade 12 condom use: [gender×tobacco: β = .22, p = .02, OR = 1.66 (95% CI = 1.08–2.55); gender×binge drinking: β = .98, p < .01, OR = 9.96 (95% CI = 5.03–19.73)]. Multiple groups analyses indicated the relation between tobacco use and binge drinking intercepts and condom use were significant for males but not females.

4. Discussion

The current study examined relations among conduct problems, substance use, and risky sexual behavior in a community sample of children at high risk for conduct disorder, using a parallel process growth mixture model. Participants in the current study started kindergarten with conduct problem scores that were one standard deviation above the normative average. The current study identified four classes of high-risk adolescents based on joint conduct problems and substance use and found that these groups differed in risk for later risky sexual behavior. The four classes were high conduct problems and high substance use, increasing conduct problems and increasing substance use, minimal conduct problems and increasing substance use, and minimal conduct problems and minimal substance use. The trajectory patterns of these classes are consistent with extant trajectory studies on conduct problems (Wiesner and Windle, 2004) and substance use (Tucker et al., 2005).

Across all substances (i.e., tobacco use, binge drinking, and marijuana use), higher levels of childhood conduct problems during kindergarten predicted a greater probability of expected membership in the more problematic conduct problem and substance use classes during adolescence relative to less problematic classes. Furthermore, individuals in the more problematic classes showed higher rates of early sexual intercourse, infrequent condom use, receiving money for sexual services, and ever contracting an STD. Individuals in the high class were approximately twice as likely to not use condoms during sex, five times as likely to receive money for sexual services during high school, and four times as likely to ever contract an STD, relative to the other three classes. These findings highlight the importance of providing sexual risk preventive intervention to individuals who engage in conduct problems and substance use during early adolescence.

Seventh grade tobacco use, binge drinking, and being male increased the chance of risky sexual behavior during late adolescence. This suggests that individuals who use tobacco and binge drink during early adolescence might be particularly likely to engage in higher levels of sexual risk taking into late adolescence. For example, males who used substances in grade 7 were less likely to use condoms in grade 12. Thus, these individuals could potentially benefit from early condom use education (e.g., Mullen, Ramirez, Strouse, Hedges, and Sogolow, 2002).

4.1 Strengths

The current study contributes to the literature on problem behaviors by examining longitudinal trajectories of conduct problems with three separate substances and their influence on multiple indicators of risky sexual behavior. It is possible that these behaviors are linked by an underlying core pathological process (Krueger et al., 2007). Future studies should investigate potential underlying processes that act as a common link among these problem behaviors, such as behavioral disinhibition (Iacono, Malone, and McGue, 2008) and impulsivity (Lejeuz et al., 2007). Also, the current study included 13 years of longitudinal data, which provides an extensive developmental model of behavior from childhood to late adolescence. Last, because much research on the developmental pathways of conduct problems has been conducted with boys, the applicability of these pathways to girls is less well established (McMahon and Frick, 2005). By including both genders, we were able to show that even though a higher proportion of boys were classified into the more problematic trajectory classes relative to girls, associations between conduct problems and substance use did not differ by gender.

4.2 Limitations and Implications

First, because the current study examined a high-risk sample, our findings are specific to early-starting conduct-problem youth and may not generalize to other levels of risk. A second potential limitation is the nature of the latent trajectory classes (Bauer and Curran, 2003). In the current study, the robustness of class definitions across substances provides strong evidence for the utility of these models. However, we are not able to draw conclusions about actual risk levels. These findings do suggest that high-risk youth, who were expected to follow more problematic trajectories and used tobacco and binge drank by seventh grade, may be particularly appropriate targets for early preventive interventions.

4.3 Conclusion

The findings add support to the hypothesis that knowledge of the development of conduct problems, substance use, and risky sexual behavior can be enhanced by taking an integrated approach (Krueger et al., 2007). Specifically, we were able to demonstrate the temporal connection among all three problem behaviors in a single model. It is well established that conduct problems, substance use, and risky sexual behavior tend to co-occur in adolescents (Doljanac and Zimmerman, 1998) and these problems behaviors result in enormous societal and economic costs (e.g., Cohen, 1998; Miller et al., 2006). For these reasons, research is needed to further explicate the pathways by which these problem behaviors develop and identify risk and protective factors that contribute to or pre-empt these behavior patterns.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Members of the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group include Karen L. Bierman (Pennsylvania State University), John D. Coie (Duke University), Kenneth A. Dodge (Duke University), Mark T. Greenberg (Pennsylvania State University), John E. Lochman (University of Alabama), Robert J. McMahon (University of Washington), and Ellen E. Pinderhughes (Tufts University)

The substance use item was endorsed by only five participants (1%) throughout grades K to 5. Hence, excluding this item did not significantly affect the T-scores.

Several baseline covariates were significantly related to the growth factors of the quadratic LGM: (a) African-Americans had a higher intercept than non African-Americans (β = .27, p < .05, r = .31); (b) Nashville and Seattle had more positive slopes than Durham (β = .25, p < .05, r = .11, and β = .29, p < .05, r = .18, respectively); (c) cohort 3 had a more negative slope than cohort 1 (β = −.24, p < .05, r = −.23); and (d) African-Americans had a more negative slope than non African-Americans (β = −.24, p < .05, r = −.25).

As with the childhood conduct problem LGMs, the quadratic forms for each adolescent growth model fitted the observe data best relative to the intercept only and intercept plus linear slope model.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Adams EH, Blanken AJ, Ferguson LD, Kopstein A. Overview of Selected Drug Trends. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1224–1239. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach KJ, Collins LM. A multidimensional developmental model of alcohol use during emerging adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2006;67:917–925. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: Adaptive functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:192–211. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000189134.97436.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Distributional assumptions of growth mixture models: Implications for overextraction of latent trajectory classes. Psychological Methods. 2003;9:338–363. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research design. 1997 doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. Retrieved September 30, 2009 from Adolescent Health web site: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Biglan A, Brennan PA, Foster SL, Holder HD. Helping Adolescents At Risk: Prevention of Multiple Problem Behaviors. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. The Ohio State University; National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 Cohort, 1997–2001. Produced by the National Opinion Research Center, the University of Chicago and distributed by the Center for Human Resource Research. 2002

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:467–488. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L, Stoolmiller M. Predicting timing of first sexual intercourse for at-risk adolescent males. Child Development. 1996;67:344–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report: U.S. HIV and AIDS cases reported through June 1998. Midyear Addition. 1998;10:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA. The monetary value of saving a high-risk youth. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1998;14:5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. A developmental and clinical model for the prevention of conduct disorders: The FAST Track program. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:509–527. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drugs. 2004 Retrieved September 30, 2009, from Fast Track web site: http://www.fasttrackproject.org/techrept/t/tad.

- Doljanac RF, Zimmerman MA. Psychosocial factors and high-risk sexual behavior: Race differences among urban adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;21:451–465. doi: 10.1023/a:1018784326191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC. An introduction to latent growth curve modeling. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:333–363. [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum PE, Dedrick RF. Changes in use of alcohol, marijuana, and services by adolescents with serious emotional disturbance: A parallel process growth mixture model. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2007;15:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Chung IJ, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Developmental relationships between adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;2002:354–362. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications of substance abuse prevention. Psychology Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Elliott DS. Reassessing the reliability and validity of self-report delinquency measures. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1986;2:293–327. [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: Common and specific influences. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Donovan JE, Costa FM. Beyond Adolescence: Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development- A Longitudinal Study of Youth. New York: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99:1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Benning SD, Kramer MD. Linking antisocial behavior, substance use, and personality: An integrative quantitative model of the adult externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:645–666. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc M, Loeber R. Developmental criminology revisited. In: Tonry M, editor. Crime and Justice. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press; 1998. pp. 115–197. [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Aklin W, Daughters S, Zvolensky M, Kahler C, Gwadz M. Reliability and validity of the youth version of the balloon analogue risk task (BART-Y) in the assessment of risk-taking behavior among inner-city adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:106–111. doi: 10.1080/15374410709336573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G, Peel D. Finite mixture models. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Frick PJ. Evidence-based assessment of conduct problems in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:477–505. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Wells KC, Kotler JS. Conduct problems. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Treatment of Childhood Disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 137–268. [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR, Levy DT, Cohen MA. Costs of alcohol and drug-involved crime. Prevention Science. 2006;7:333–342. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Jaffee SR, Kim-Cohen J, Koenen KC, Odgers CL, Slutske WS, Viding E. DSM-V conduct disorder: Research needs for an evidence base. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:3–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PD, Ramirez G, Strouse D, Hedges LV, Sogolow E. Meta-analysis of the effects of behavioral HIV prevention interventions on the sexual risk behavior of sexually experienced adolescents in controlled studies in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;30:S94–S105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. Latent variable analysis: Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. The Sage Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables. 5th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Tremblay R. Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviors: A group-based model. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:18–34. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Paul C, Fitzjohn J, Herbison P, Dickson N. The determinants of sexual intercourse before age 16. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:136–147. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:67–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramrakha S, Bell ML, Paul C, Dickson N, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood behavior problems linked to sexual risk taking in young adulthood: A birth cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:1272–1279. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180f6340e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield HT, Bierman KL, Heinrichs B, Nix RL Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Predicting early sexual activity with behavior problems exhibited at school entry and in early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1175–1188. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Sclove SL. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika. 1987;52:333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Lacourse E, Nagin DS. Developmental trajectories of conduct problems and hyperactivity from ages 2 to 10. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:931–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenstein FL, Ku J, Lindberg JD, Turner CF, Pleck JH. Changes in sexual behavior and condom use among teenage males: 1988–1995. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:956–959. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Substance use and sexual health among teens and young adults in the U.S. CASA Fact Sheet. 2002 Retrieved September 30, 2009, from Kaiser Family Foundation web site: http://www.kff.org/youthhivstds/loader.cfm?url=/commonspot/security/getfile.cfmPageID=14905.

- Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Martino SC, Klein DJ. Substance use trajectories from early adolescence to emerging adulthood: A comparison of smoking, binge drinking, and marijuana use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Werthamer-Larsson L, Kellam SG, Wheeler L. Effects of first grade classroom environment on shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and concentration problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19:585–560. doi: 10.1007/BF00937993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner M, Windle M. Assessing covariates of adolescent delinquency trajectories: A latent growth mixture modeling approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:431–442. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: A 30-year follow-up. Health Psychology. 2008;27:149–158. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]