Abstract

It is generally agreed that adipocytes originate from mesenchymal stem cells in what can be divided into two processes: determination and differentiation. In the past decade, many factors associated with epigenetic signals have been proved to be pivotal for the appropriate timing of adipogenesis progression. A large number of coregulators at critical gene promoters set up specific patterns of DNA methylation, histone acetylation and methylation, and nucleosome rearrangement, that act as an epigenetic code to modulate the correct progress of adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis during adipogenesis. In this review, we focus on the functions and roles of epigenetic processes in preadipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis.

Keywords: Epigenetic regulation, Histone modification, DNA methylation, Differentiation, Adipogenesis

1. Introduction

In recent years, obesity has become a major global health concern and can be prescribed as an exceeding accumulation of white adipose tissue, resulting from the increase in adipocyte cell size (hypertrophy) and the substantial addition of fresh mature cells from undifferentiated precursors (hyperplasia) (Liu et al., 2008). White adipose mass is virtually a special endocrine organ which not only plays an active and central role in the regulation of the energy balance of the organism but is also important part in a number of physiological and pathological procedures (Feige and Auwerx, 2007). Therefore, considering and understanding how the procedure of adipocyte differentiation is modulated could theoretically allow us to regulate the number and function of these cells in the adult organism, thus helping to treat and relieve metabolic diseases, such as obesity and diabetes (Musri et al., 2007).

Obesity occurs when energy intake by an individual exceeds the rate of energy expenditure. At the cellular level, obesity was originally considered a hypertrophic disease resulting from an increase in the fat cell number or the size of individual adipocytes. New fat cells could arise from a preexisting population of undifferentiated progenitor cells or through the dedifferentiation of adipocytes to preadipocytes, which then proliferate and redifferentiate into mature adipocytes. In both cases, the generation of new fat cells plays a key role in the development of obesity (Marcos et al., 2001). In addition to genetic mechanisms that could lead to inter-individual differences in obesity, epigenetic concepts are initiating some new opinions and perspectives in human diseases related to pivotal gene regulation (Kershaw and Flier, 2004; Liu et al., 2008). Epigenetics has been defined as the study of heritable changes in gene expression that occur in the absence of a change and diversification in the DNA sequence itself (Dolinoy and Jirtle, 2008). In a eukaryotic organism, two major types of chromatin remodeling complexes have been examined and identified: adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent and ATP-independent chromatin remodeling complexes. ATP-dependent chromatin modifying complexes utilize the energy from ATP hydrolysis to disrupt and change nucleosome or chromatin structure to impact gene expression, such as SWItch/Sucrose NonFermentable (SWI/SNF) complexes (Narlikar et al., 2002; Guo et al., 2009). In addition, ATP-independent chromatin remodeling complexes alter nucleosome and chromatin conformations by covalent modifications of histones, including methylation, phosphorylation, and acetylation, which are usually interrelated with suppression or activation of gene expression (Martin and Zhang, 2005; Kouzarides, 2007; Quina et al., 2007).

Recent advances in epigenetics suggest that adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis are the result of an intertwined network of coregulators and transcriptional factors with chromatin-modifying activities (Narlikar et al., 2002; Martin and Zhang, 2005; Guo et al., 2009). These remarkable findings suggest that epigenetics might provide an important insight into preadipose differentiation and adipogenesis. This review provides an overview on the epigenetic regulation of preadipocyte differentiation, given their roles in preadipocyte progression and adipogenesis.

2. Cell models for study of adipocyte differentiation

Adipocytes, also known as fat cells and lipocytes, are found in stereotypical depots throughout the body and mixed with other cell types in some other positions, such as loose connective tissue. There are two kinds of adipose tissues, white adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT), both of which differ in a few significant properties. Most of our understanding about adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis comes from in vitro studies of fibroblasts and preadipocytes (Rosen and MacDougald, 2006).

2.1. Stages of adipocyte differentiation

Cell proliferation and differentiation are two fundamental and foremost courses in the development of multicellular organisms. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a heterogeneous assembly of stromal stem cells which can differentiate into cells of the mesodermal lineage. Adipocytes originate from multipotent MSCs residing in the adipose tissue stroma. This premier process of adipocyte differentiation is considered to be determination (Rosen and MacDougald, 2006). Determination promotes the transformation of the stem cell to preadipocyte. Many epigenetic incidents are in charge of this diversification in cell status, assuring that preadipocytes can be differentiated into mature adipocytes or maintained and amplified. Multipotent cell lines such as C3H/10T1/2 fibroblasts represent an excellent pattern for the research of adipose cell commitment, since these cells can be differentiated into myotubes, adipocytes, and chondrocytes in vitro after being treated with the appropriated reagents (Qiu, 2009).

In the second phase, typically called differentiation, the preadipocyte displays the features of the mature adipocyte. Differentiation requires the activation of numerous transcription factors which are in charge of the coordinated induction and silencing of more than 2000 genes related to the regulation of adipocyte in both morphology and physiology (Farmer, 2006). The course of adipocyte differentiation has been well studied using 3T3-F422A and 3T3-L1 cells, two cell lines that are definitely committed to the adipocyte lineage (Green and Kehinde, 1974; 1975; 1976). In the presence of a hormonal cocktail consisting of insulin, dexamethasone, and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 3T3-L1 and 3T3-F422A preadipocytes can differentiate into mature adipocyte cells, expressing specific adipocyte genes and accumulating triacylglycerol lipid droplets (Cornelius et al., 1994).

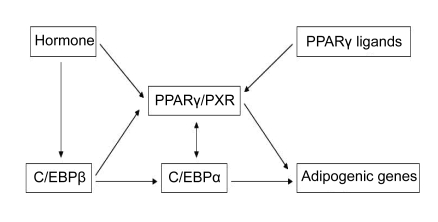

2.2. Transcriptional regulation of adipocyte differentiation

Nucleic acids from individual whiteflies and plants were extracted using the methods of Luo et al. (2002) and Xie et al. (2002), respectively. Terminal adipocytes differentiation involves a series of transcriptional cases. The first wave of adipogenesis consists of the transient dramatic induction of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-β (C/EBPβ) and -δ (C/EBPδ), stimulated in vitro by 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine and dexamethasone, respectively (Ramji and Foka, 2002). C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ begin to accumulate within 24 h of adipogenesis induction and the cells re-take the cell cycle and execute mitotic clonal expansion (MCE) synchronously (Tang et al., 2003). In the conversion from G1 to S stage, C/EBPβ is hyperphosphorylated and sequentially activated by glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Then, both C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ directly induce expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) and C/EBPα, the key transcriptional regulators of adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis (Tang et al., 2005). By Day 2 of the differentiation course, C/EBPα protein initiates to accumulate, and then is phosphorylated by the cyclin D3. Phosphorylated C/EBPα shows a proliferation inhibition effect on the cells, which can hereafter withdraw the cell cycle and begin final differentiation and adipogenesis (Wang et al., 2006; Musri et al., 2007). Growth arrest is followed by expression of final adipogenic genes. PPARγ and C/EBPα subsequently not only initiate positive feedback to induce their own expression, but also activate a large number of downstream target genes whose expression determines the adipocyte. And by Day 8 after differentiation induction, more than 90% of the adipocytes are mature already (Fig. 1) (Huang and Donald, 2007). In addition, PPARγ is a prerequisite for the differentiation of both brown and white adipocytes (Kajimura et al., 2008).

Fig. 1.

Pattern of regulation of 3T3-L1 differentiation by C/EBPs and PPARγ

The expression pattern of numerous transcription factors is believed to function in the differentiation program

In addition to PPARγ and C/EBPs, recently many other factors have been located and associated with the modulation of adipogenesis. The super family of forkhead-containing transcription factors (Fox) consists of numerous elements and factors with known functions on the process of development and differentiation (Huang and Donald, 2007; Musri et al., 2007). Like C/EBPβ, FoxO1 is induced immediately after the initial phase of differentiation; however, its activation is postponed until the end of the MCE stage, when it induces the expression of cyclin-kinase inhibitor p21, resulting in withdrawing cell-cycle (Armoni et al., 2006). In addition, previous studies have suggested that specific expression of FoxC2 in adipocytes could lead to transformation of WAT to a phenotype like “brown”-like adipose tissue (Cederberg et al., 2001; Darlington et al., 1998).

3. Epigenetic regulation of adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis

Epigenetic regulation plays a critical role in several differentiation processes and possibly in adipocyte differentiation (D′Alessio et al., 2007). C3H/10T1/2 fibroblasts can go through adipogenesis spontaneously accompanied with special demethylation and the expression of the bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) gene under the treatment with 5-azacytidine (Bowers et al., 2006). In addition, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, another DNA methylation inhibitor, can inhibit differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells (Sakamoto et al., 2008). Recently, it is demonstrated that the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells associates with genome-wide epigenetic changes by the ratio of demethylation/methylation and furthermore maintenance of a static demethylated/methylated state, both of which depend on differentiation phase (Sakamoto et al., 2008). This fact proves that DNA methylation might be associated with the course of determination. In addition, studying with 3T3-L1 cells using microarray-based integrated method clarifies that adipogenesis is regulated by a rashomologue guanine nucleotide exchange factor (RhoGEF, WGEF) expression through DNA methylation change (Horii et al., 2009). A study through isolated adipose stromal cells has described that there are several hypomethylated adipogenic promoters, such as PPARγ and leptin (Noer et al., 2006; Yokomori et al., 2002).

In addition, several studies have suggested that the promoters of final adipogenic genes including leptin and glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4), which are methylated in preadipocytes, show the hypomethylated characteristics throughout adipogenesis. There are, however, some results which indicate that the diet-induced up-regulation of leptin and secreted frizzled-related protein 5 (sFRP5) gene expression in WAT during the development of obesity in mice is not mediated directly by changes in DNA methylation with the C57BL/6J mice model (Okada et al., 2009). Furthermore, like DNA demethylation, the methylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) is related to transcriptional activation. In order to detect the change of histone methylation, 3T3-L1 fibroblast cells are treated with low-dose of the methyltransferase inhibitor methylthioadenosine, which eliminates this epigenetic sign from the promoters, and generates significantly decreased adipogenesis, therefore, suggesting the crucial role of this histone modification in the regulation of adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis (Musri et al., 2006). The transcription factors and co-regulators involved in preserving appropriate levels of histone methylation and modification at the late adipogenic genes remain unknown. Above all, the role of DNA and histone modification in adipogenesis is very important and some functions remain unknown.

3.1. Regulation of adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis by C/EBPs

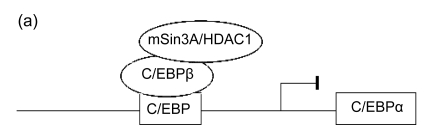

As mentioned above, it is suggested that C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ proteins can combined to the C/EBPα promoter as early as 4 h after the induction of adipogenesis tested by chromatin immunoprecipitation (CHIP) (Salma et al., 2006). Its activity, however, is blocked by the mammalian Sin3 protein A/histone deacetylase complex 1 (mSin3A/HDAC1) (Fig. 2a). Once PPARγ protein accumulates subsequently, it is able to guide HDAC1 to the 26S proteasome, resulting in its degradation and causing the activation of C/EBPα expression by C/EBPβ (Fig. 2b) (Zuo et al., 2006). After the protein of C/EBPα gathers in the nucleus of the differentiating cells, it substitutes C/EBPβ binding from the promoters of PPARγ and other adipogenic genes (Salma et al., 2006). C/EBPα promotes transcription of its downstream target genes through recruiting and raising the SWI/SNF remodeling complex to their proper promoter regions by direct interactions with its transactivation element III domain (TE-III), indicating that the complex is prerequisite for gene activation, adipocyte differentiation, and adipogenesis (Müller et al., 2004; Musri et al., 2007). In addition to regulating the expression of adipogenic genes, another main function of C/EBPα is to prompt the cell to withdraw the cell cycle, an important matter for 3T3-L1 fibroblast differentiation (Johnson, 2005). It is considered that C/EBPα depends on the SWI/SNF remolding complex to prompt growth arrest through repressing E2F-dependent promoters (Wang et al., 2006). Furthermore, it has been shown that Pax transactivation domain-interacting protein (PTIP), a protein that related to histone H3K4 methyltransferases, regulates PPARγ and C/EBPα expression during preadipocyte differentiation and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Cho et al., 2009).

Fig. 2.

Epigenetic regulation of C/EBP transcription factors

(a) The C/EBPβ-induced activity is blocked by the mSin3A/HDAC1 complex; (b) PPARγ protein is able to guide mSin3A/HDAC1 complex to the 26S proteasome and cause the activation of C/EBPα expression by C/EBPβ

In our lab, we have studied the DNA methylation modifications throughout adipogenesis at the promoter regions of C/EBPα. We have noticed that the promoter of C/EBPα displayed dramatic level of DNA hypermethylation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (unpublished data). Interestingly, this hypermethylation signal was not detected at the promoters of C/EBPα gene in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Thus, according to our data, it is speculated that this epigenetic mark is related to the recruitment of specific protein 1 (Sp1) to the binding site for Sp family members at the promoter of C/EBPα. And the presence of DNA hypermethylation at the promoter region of C/EBPα gene suggests that the cells have experienced a differentiation stage and are committed to be differentiated into mature adipocytes.

3.2. Regulation of PPARγ in adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis

3.2.1. Role of chromatin remodeling

A main rearrangement of nucleosome and chromosome location has been observed during adipogenesis (Musri et al., 2007), indicating that nuclear and chromatin compartments are dynamic variation during cell differentiation, and that these alterations might take an active part in the modulation of transcriptional activity.

By Day 1 of induction of differentiation, C/EBPβ can all bind to the PPARγ promoter and induce the expression of the gene. Subsequently, the binding of SWI/SNF occurs, generating chromatin remodeling of the promoter, and then transcription starts by Day 2 (Salma et al., 2004). Since SWI/SNF complex binding is unstable, however, simultaneously coinciding with the dissociation of several SWI/SNF components from the promoter, it is observed that transcription of PPARγ decreases after Day 4 and the PPARγ mRNAs are found on Days 5–7, representing stable mRNAs produced on Day 4 or earlier (Musri et al., 2007; Salma et al., 2004). In addition, the promoter of the PPARγ gene is hypermethylated in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes, but is gradually demethylated upon induction of differentiation (Fujiki et al., 2009).

3.2.2. Regulation of PPARγ by retinoblastoma (Rb) protein and adipocyte determination and differentiation factor-1/sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 (ADD1/SREBP1)

Recent studies have shown that Rb protein is associated with histone deacetylase HDAC3 and shows a passive effect on the initial stages of differentiation (Salma et al., 2004). When Rb is dephosphorylated, the Rb/HDAC3 complex interacts with PPARγ, producing the raising of deacetylase activity to the PPARγ promoters and causing their suppression (Feige and Auwerx, 2007). While Rb phosphorylation weakens this interplay, then PPARγ is able to associate with the histone acetyltransferases, cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB)-binding protein (CBP) and p300, allowing the activation of PPARγ target genes. The interaction of PPARγ with CBP/p300 plays a crucial role in differentiation and adipogenesis, because the repression of its expression in 3T3-L1 fibroblasts significantly decreases adipogenesis (Feige and Auwerx, 2007). Interestingly, Rb represses PPARγ expression and therefore instructs differentiation to the white rather than the brown adipose lineage by binding to the PPARγ promoter (Scimè et al., 2005). Furthermore, Rb-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts show additional expression of FoxC2 and the gene transcription and expression pattern of brown adipocytes (Hansen et al., 2004; Musri et al., 2007).

SREBP1, which includes the helix-loop-helix motif, has been shown to enhance PPARγ-driven adipogenesis (Yang et al., 2007), and also associates with CBP to improve its transcriptional capability (Nerlov, 2008). In addition, SREBP1 is a target for CBP-mediated acetylation modification, which generates stable protein levels of the factor through competing with ubiquitination activity, then preventing targeting to the proteasome (Giandomenico et al., 2003). Recently, it was revealed that SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex interacts with the ADD1/SREBP1c and actively modulates insulin-dependent gene expression to regulate lipid metabolism. Furthermore, the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling facts stimulate the transcriptional activity of ADD1/SREBP1c co-operative with PPARγ co-activator 1α (PGC-1α) in fat cells for energy homeostasis (Lee et al., 2007).

3.2.3. Regulation of PPARγ by cyclin D1/3

In the early phase of the differentiation process, high levels of cyclin D1 handicap immature expression of PPARγ by associating with PPARγ and raising enlistment to its target promoters of histone deacetylase complex HDAC1/3 and histone methyltransferase SUV39H1, a human homologue of the Drosophila position effect variegation modifier Su(var) 3-9. This produces decreased acetylation of PPARγ target promoters such as that of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), which is responsible for decreased expression (Fu et al., 2005). With the addition of ligands, PPARγ competes with p300 for a c-Fos binding site and then restrains the expression of cyclin D1, a crucial factor regulating the cell cycle during cellular proliferation and adipocyte differentiation (Fox et al., 2008).

On the other hand, after the MCE phase, the levels of cyclin D1 decrease dramatically, simultaneously while the expression of cyclin D3 is induced. Cyclin D3 plays a role as a PPARγ ligand-dependent coactivator and also an important role in differentiation and adipogenesis independent of its cell-cycle regulator. Cyclin D3, together with the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK6), binds to and phosphorylates PPARγ and generates increased transcriptional activity (Sarruf et al., 2005).

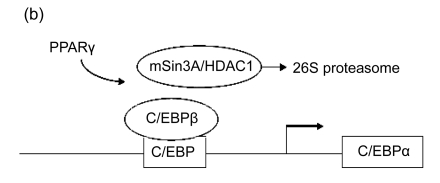

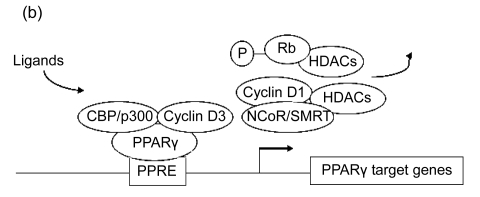

3.2.4. Regulation of PPARγ by ligands

It is known that in the absence of its ligand, PPARγ can also enlist some corepressors such as nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) and silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT), which decrease the transcriptional activity of the factor and therefore the expression of its target genes. Co-expression of NCoR inhibits the transcriptional activity of PPARγ, as well as that of its isoform PPARα, whereas co-expression of the histone acetyltransferase steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC1) could enhance it (Fig. 3a) (Rotman et al., 2008; Musri et al., 2007). In 3T3-L1 adipocytes, the addition of PPARγ ligand troglitazone can block the PPARγ/NCoR complex and turn out the activation of PPARγ transcriptional activity (Yu et al., 2005). Simultaneously binding to the ligand also increases interaction of PPARγ with histone acetyltransferases CBP and p300, even though this interaction may take place in the absence of ligand (Fig. 3b) (Cho et al., 2008; Musri et al., 2007). The addition of troglitazone induces the exchange of suppressive NCoR/SMRT complexes through causing the expression of PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) (Guan et al., 2005).

Fig. 3.

Epigenetic regulation of PPARγ target gene expression

(a) In the absence of PPARγ ligand, some corepressors such as NCoR/SMRT decrease the expression of its target genes; (b) PPARγ ligand can block the PPARγ/NCoR complex and cause the activation of PPARγ transcriptional activity

4. Conclusions

In summary, this review focuses on the importance of epigenetic regulation in the adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis and reports some epiobesigenic genes potentially involved in these processes. Epigenetics has become an increasingly important factor programmatically throughout complex processes of development and adipogenesis. A large amount of studies have shown the significance of epigenetics in the change between undifferentiated and differentiated fibroblast cells. Adipogenesis apparently includes the synthetical regulation of chromosome modifications, nucleosome structure, chromatin variants, and histone remodeling. This knowledge will undoubtedly lead to new therapies and treatments to combat disease initiation and progression. However, the interactions connecting these significant epigenetic marks, as well as the transcriptional downstream regulation, need to be forward expounded. Another future direction is to determine whether epigenetic regulation is effective in the prevention and treatment of obesity in vivo.

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31071027 and 30870926), the National Key Technology R&D Program of China (No. 2008BAC39B05), and the Fund from Key Laboratory for Cell Proliferation and Regulation Biology of Ministry of Education and Beijing Key Laboratory of Engineered Drug and Biotechnology, Beijing Normal University, China

References

- 1.Armoni M, Harel C, Karni S, Chen H, Yoseph F, Marel R, Quon MJ, Karnieli E. FoxO1 represses peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ1 and -γ2 gene promoters in primary adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(29):19881–19891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowers RR, Kim JW, Otto TC, Lane MD. Stable stem cell commitment to the adipocyte lineage by inhibition of DNA methylation: role of the BMP-4 gene. PNAS. 2006;103(35):13022–13027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605789103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cederberg A, Gronning LM, Ahren B, Tasken K, Carlsson P, Enerback S. FoxC2 is a winged helix gene that counteracts obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and diet-induced insulin resistance. Cell. 2001;106(5):563–573. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00474-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho MC, Lee K, Paik SG, Yoon DY. Peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor (PPAR) modulators and metabolic disorders. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2008/679137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho YW, Hong SH, Jin Q, Wang LF, Lee JE, Gavrilova O, Ge K. Histone methylation regulator PTIP Is required for PPARγ and C/EBPα expression and adipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2009;10(1):27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornelius P, MacDougald OA, Lane MD. Regulation of adipocyte development. Annu Rev Nutr. 1994;14(1):99–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.14.070194.000531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D′Alessio AC, Weaver IC, Szyf M. Acetylation-induced transcription is required for active DNA demethylation in methylation-silenced genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(21):7462–7474. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01120-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darlington GJ, Ross SE, MacDougald OA. The role of C/EBP genes in adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(46):30057–30060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolinoy DC, Jirtle RL. Environmental epigenomics in human health and disease. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2008;49(1):4–8. doi: 10.1002/em.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farmer SR. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metabolism. 2006;4(4):263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feige JN, Auwerx J. Transcriptional coregulators in the control of energy homeostasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(6):292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox KE, Colto LA, Erickson PF, Friedman JE, Cha HC, Keller P, MacDougald OA, Klemm DJ. Regulation of cyclin D1 and Wnt10b gene expression by cAMP-responsive element-binding protein during early adipogenesis involves differential promoter methylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(50):35096–35105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806423200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu M, Rao M, Bouras T, Wang C, Wu K, Zhang X, Li ZP, Yao T, Pestell1 RG. Cyclin D1 inhibits PPARγ-mediated adipogenesis through histone deacetylase recruitment. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(17):16934–16941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujiki K, Kano F, Shiota K, Murata M. Expression of the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ gene is repressed by DNA methylation in visceral adipose tissue of mouse models of diabetes. BMC Biology. 2009;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giandomenico V, Simonsson M, Gronroos E, Ericsson J. Coactivator-dependent acetylation stabilizes members of the SREBP family of transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(7):2587–2599. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2587-2599.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green H, Kehinde O. Sublines of mouse 3T3 cells that accumulate lipid. Cell. 1974;1(3):113–116. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90126-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green H, Kehinde O. An established preadipose cell line and its differentiation in culture II. Factors affecting the adipose conversion. Cell. 1975;5(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green H, Kehinde O. Spontaneous heritable changes leading to increased adipose conversion in 3T3 cells. Cell. 1976;7(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guan HP, Ishizuka T, Chui PC, Lehrke M, Lazar MA. Corepressors selectively control the transcriptional activity of PPARγ in adipocytes. Genes Dev. 2005;19(4):453–461. doi: 10.1101/gad.1263305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo W, Zhang KM, Tu K, Li YX, Zhu L, Xiao HS, Yang Y, Wu JR. Adipogenesis licensing and execution are disparately linked to cell proliferation. Cell Res. 2009;19(2):216–223. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen JB, Jorgensen C, Petersen RK, Hallenborg P, de Matteis R, Boye HA, Petrovic N, Enerback S, Nedergaard J, Cinti S, et al. Retinoblastoma protein functions as a molecular switch determining white versus brown adipocyte differentiation. PNAS. 2004;101(12):4112–4117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0301964101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horii T, Morita S, Kimura M, Hatada I. Epigenetic regulation of adipocyte differentiation by a Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor, WGEF. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(6):e5809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang HJ, Donald JT. Dynamic FoxO transcription factors. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(15):2479–2487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.001222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson PF. Molecular stop signs: regulation of cell-cycle arrest by C/EBP transcription factors. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(12):2545–2555. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kajimura S, Seale P, Tomaru T, Erdjument-Bromage H, Cooper MP, Ruas JL, Chin S, Tempst P, Lazar MA, Spiegelman BM. Regulation of the brown and white fat gene programs through a PRDM16/CtBP transcriptional complex. Genes Dev. 2008;22(10):1397–1409. doi: 10.1101/gad.1666108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kershaw EE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2548–2556. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128(4):693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee YS, Sohn DH, Han D, Lee HW, Seong RH, Kim JB. Chromatin remodeling complex interacts with ADD1/SREBP1c to mediate insulin-dependent regulation of gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(2):438–452. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00490-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu L, Li YY, Tollefsbol T. Gene-environment interactions and epigenetic basis of human diseases. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2008;10(1):25–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo C, Yao Y, Wang RJ, Yan FM, Hu DX, Zhang XL. The use of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (mtCOI) gene sequences for the identification of biotypes of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) in China. Acta Entomol Sin. 2002;45(6):759–763. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcos A, Montero A, Lopez-Varela S, Morande G. Eating disorders (obesity, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa), immunity, and infection. Nutr Immun Infect Infants Child. 2001;45:243–262. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin C, Zhang Y. The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(11):838–849. doi: 10.1038/nrm1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Müller C, Calkhoven CF, Sha X, Leutz A. C/EBPα requires a SWI/SNF complex for proliferation arrest. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(8):7353–7358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Musri MM, Corominola H, Casamitjana R, Gomis R, Parrizas M. Histone H3 lysine 4 dimethylation signals the transcriptional competence of the adiponectin promoter in preadipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(25):17180–17188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Musri MM, Gomis R, Párrizas M. Chromatin and chromatin-modifying proteins in adipogenesis. Cell Biol. 2007;85(4):397–410. doi: 10.1139/O07-068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narlikar GJ, Fan HY, Kingston RE. Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell. 2002;108(4):475–487. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00654-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nerlov C. C/EBPs: recipients of extracellular signals through proteome modulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20(2):180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noer A, Sorensen AL, Boquest AC, Collas P. Stable CpG hypomethylation of adipogenic promoters in freshly isolated, cultured, and differentiated mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(8):3543–3556. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okada Y, Sakaue H, Nagare T, Kasuga M. Diet-induced up-regulation of gene expression in adipocytes without changes in DNA methylation. Kobe J Med Sci. 2009;54(5):241–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiu J. Cellular differentiation: a two-stage procedure. Cell Res. 2009;19:216–223. doi: 10.1038/nchina.2009.35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quina AS, Buschbeck M, Croce LD. Chromatin structure and epigenetics. Biol Reprod. 2007;72(11):1563–1569. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramji DP, Foka P. CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins: structure, function and regulation. Biochem J. 2002;365:561–575. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosen ED, MacDougald OA. Adipocyte differentiation from the inside out. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(12):885–896. doi: 10.1038/nrm2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rotman N, Zofia HT, Lucke S, Feige J, Gelman L, Desvergne B, Wahli W. PPAR disruption: cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences. Chimia. 2008;62(5):340–344. doi: 10.2533/chimia.2008.340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakamoto H, Kogo Y, Ohgane J, Hattori N, Yagi S, Tanaka S, Shiota K. Sequential changes in genome-wide DNA methylation status during adipocyte differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366(2):360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salma N, Xiao H, Mueller E, Imbalzano AN. Temporal recruitment of transcription factors and SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling enzymes during adipogenic induction of the PPARγ nuclear hormone receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(11):4651–4663. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4651-4663.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salma N, Xiao H, Imbalzano AN. Temporal recruitment of C/EBPs to early and late adipogenic promoters in vivo. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;36(1):139–151. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarruf DA, Iankova I, Abella A, Assou S, Miard S, Fajas L. Cyclin D3 promotes adipogenesis through activation of PPARγ. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(22):9985–9995. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.22.9985-9995.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scimè A, Grenier G, Huh MS, Gillespie MA, Bevilacqua L, Harper ME, Rudnicki M. Rb and p107 regulate preadipocyte differentiation into white versus brown fat through repression of PGC-1α. Cell Metab. 2005;2(5):283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang QQ, Otto TC, Lane MD. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β is required for mitotic clonal expansion during adipogenesis. PNAS. 2003;100(3):850–855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337434100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang QQ, Gronborg M, Huang H, Kim JW, Otto TC, Pandey A, Lane MD. Sequential phosphorylation of C/EBPβ by MAPK and GSK3β is required for adipogenesis. PNAS. 2005;102(28):9766–9771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503891102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang GL, Shi X, Salisbury E, Sun Y, Albrecht JH, Smith RG, Timchenko NA. Cyclin D3 maintains growth-inhibitory activity of C/EBPα by stabilizing C/EBPα-cdk2 and C/EBPα-Brm complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(7):2570–2582. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2570-2582.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie Y, Zhou XP, Zhang ZK, Qi YJ. Tobacco curly shoot virus isolated in Yunnan is a distinct species of Begomovirus. Chin Sci Bull. 2002;47(3):197–200. doi: 10.1360/02tb9047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang LH, Chen TM, Yu ST, Chen YR. Olanzapine induces SREBP-1-related adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Pharmacol Res. 2007;56(3):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yokomori N, Tawata M, Onaya T. DNA demethylation modulates mouse leptin promoter activity during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. Diabetologia. 2002;45(1):140–148. doi: 10.1007/s125-002-8255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu C, Markan K, Temple KA, Deplewski D, Brady MJ, Cohen RN. The nuclear receptor corepressors NCoR and SMRT decrease PPARγ transcriptional activity and repress 3T3-L1 adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(14):13600–13605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409468200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zuo Y, Qiang L, Farmer SR. Activation of C/EBPα expression by C/EBPβ during adipogenesis requires a PPARγ-associated repression of HDAC1 at the C/EBPα gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(12):7960–7967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]