Abstract

The present study uses the osteoclast precursor clonal line, HD-11EM, to study the potential of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in mediating the differentiation of HD-11EM into osteoclast-like cells. HD-11EM cells are a newly established clonal cell line that, in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3, differentiate into osteoclast-like cells that are multinucleated (more than three nuclei), express tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), and excavate resorption pits when cultured on dentin slices in the presence of osteoblasts (Hsia et al., 1995, J. Bone Miner. Res., 10(Suppl 1):S424; Hsia, and Hauschka, 1997, unpublished data). Here we demonstrate that HD-11EM express the reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-oxidase specific cytochrome b558 subunits, and that stimulation of HD-11EM with 1 or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 increases the extracellular release of H2O2 within 5–10 min. Ours is the first report that stimulation of a cell with 1α,25-(OH)2D3 enhances the activation of NADPH-oxidase and increases the basal release of superoxide and the formation of its dismutation product, H2O2. To determine the possible involvement of H2O2 in the differentiation of HD-11EM, these cells were exposed to glucose/glucose oxidase. This enzyme system was used to deliver a pure and continuous source of H2O2 in nanomole amounts consistent with quantities produced by HD-11EM in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3. Both 1α,25-(OH)2D3 and the exogenously generated H2O2 stimulated a dose- and time-dependent increase in TRAP activity/cell and the number of multinucleated cells 24–48 hr after treatment. Northern analysis confirmed an increase in expression of TRAP mRNA in response to either 1α,25-(OH)2D3 or H2O2. Decreases in cell proliferation and v-myc mRNA were also observed in response to these agents. Taken together, our findings indicate that production of H2O2 by HD-11EM is an important local factor involved in differentiation of HD-11EM into osteoclast-like cells, and suggest that H2O2 may play a role in native osteoclast differentiation.

Osteoclasts are the principal cells responsible for bone resorption (Chambers and Horton, 1984), and maintenance of skeletal mass is dependent on the formation and functional activation of these cells. Osteoclasts are generally believed to be derived from hematopoietic bone marrow progenitor cells, which have the capacity to differentiate and circulate in the blood as mononuclear osteoclast precursors (Fischman and Hay, 1962; Gothlin and Ericsson, 1973; Walker, 1973, 1975; Kahn and Simmons, 1975; Coccia et al., 1980). Maintaining skeletal mass is therefore dependent on the continuous recruitment of osteoclast precursors from the blood to bone surfaces. At or near bone surfaces, the mononuclear osteoclasts undergo further differentiation, and fuse to form the classic multinucleated osteoclast capable of resorbing bone. Although progress has been made in unraveling the basic cellular mechanisms that regulate the formation and activity of osteoclasts, our understanding of how they differentiate from hematopoietic bone marrow progenitors and become functionally active is incomplete (for review see Marks, 1983; Zaidi et al., 1993b; Roodman, 1995; Athanasou, 1996; Suda et al., 1997).

Advances in our understanding of osteoclast differentiation are based in part on the introduction of methods for the isolation and long-term culture of osteoclast bone marrow progenitor cells (Testa et al., 1981; Burger et al., 1982; Suda et al., 1997). However, osteoclast progenitor cells are not readily identifiable and are often a subpopulation of cells that may vary from preparation to preparation. In addition, most long-term culture systems suffer from the problem of being heterogeneous populations of cells, including osteoblasts and stromal cells, making it difficult to study the actual signaling pathways and responses of the osteoclast population to osteotropic hormones or local factors.

Another approach in the study of osteoclast differentiation has been to develop clonal cell lines from bone marrow progenitor cells, which have a high potential to differentiate into osteoclast-like multinucleate cells when cultured in the presence of osteotropic or neuroendocrine hormones (Gattei et al., 1992; Chambers et al., 1993; Shin et al., 1995; Hsia et al., 1995; Frediani et al., 1996; Hsia and Hauschka, unpublished data). However, none of these cell lines, despite showing osteoclast-like characteristics, have been shown to excavate resorption lacunae when incubated on slices of bone or dentin. Hsia and Hauschka (Hsia et al., 1995; Hsia and Hauschka, unpublished data) have recently developed a clonal cell line designated HD-11EM from the polyclonal v-myc-transformed myelomonocytic cell line, HD-11 (Beug et al., 1979). The HD-11EM clonal line shows a high potential to differentiate into osteoclast-like cells in response to the osteotropic hormone, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1α,25-(OH)2D3). A significant percentage of the cells that form in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3 are multinucleated, express tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), and excavate resorption pits when cultured on dentin slices in the presence of chicken osteoblasts (Hsia and Hauschka, unpublished data). The HD-11EM clonal line is therefore appropriate for studying the signaling pathways and responses of osteoclast precursors to osteotropic hormones or local factors that can influence their differentiation. Although the HD-11EM is an avian cell line, and the number of calcitonin receptors that are present on mature avian osteoclasts is known to be significantly less than those present on rat osteoclasts, we feel this is an appropriate line to study osteoclast differentiation, given that avian and mammalian osteoclasts demonstrate more similarities than differences in their responses to various hormones and in their resorptive activity (for review see Osdoby et al., 1992).

The differentiation and activity of osteoclasts are influenced by a number of osteotropic hormones, cytokines, and local factors (for review see: Zaidi et al., 1993b; Roodman, 1995; Suda et al., 1995, 1997; Manolagas, 1995; Athanasou, 1996). Among the osteotropic hormones, 1α,25-(OH)2D3 acts mainly by enhancing the differentiation of committed osteoclast precursors, and the addition of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 is required for the formation of osteoclasts in in vitro long-term cultures containing osteoblasts or stromal cells (Raisz et al., 1972; Bar-Shavit et al., 1983; Roodman et al., 1985; Takahashi et al., 1988; Udagawa et al., 1990; Quinn et al., 1994). In addition to the more accepted role of an indirect action of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 on the expression of local factors by osteoblasts or stromal cells, studies with HD-11EM cells indicate that 1α,25-(OH)2D3 can act directly on osteoclast precursors to stimulate osteoclast formation (Hsia et al., 1995; Hsia and Hauschka, unpublished data).

One local factor that may be involved in regulation of osteoclast differentiation is the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide and H2O2, originating from endothelial cells, stromal cells, and osteoclasts themselves. Garrett et al. (1990) initially reported ROS production by mature osteoclasts, as measured by the reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), in mouse calvarial cultures in response to exogenous parathyroid hormone, interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor, and 1α,25-(OH)2D3. These investigators also correlated production of ROS with osteoclast formation and activation, noting that addition of superoxide dismutase (SOD), which depletes superoxide, blocked NBT reduction and formation of additional osteoclasts. Catalase, which removes H2O2, had no effect in their studies. In contrast, Suda et al. (Suda, 1991; Suda et al., 1993) found that addition of catalase inhibited the number of osteoclast-like cells formed from progenitor cells in mouse calvarial organ cultures stimulated with 1α,25-(OH)2D3. Addition of exogenous H2O2 to their cultures overcame the effect of catalase, whereas addition of SOD, which would also increase the amount of H2O2, increased the number of osteoclast-like cells. The relative contributions of superoxide and/or H2O2 toward the differentiation of osteoclasts from progenitor cells remain unclear, as do the cellular origins of ROS and the regulating mechanisms of osteotropic hormones and local factors in stimulating ROS production.

The present study tests the hypothesis that production of a local factor(s) by HD-11EM cells in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3 mediates the differentiation of HD-11EM into osteoclast-like cells. We were able to establish that one of the early local factors produced by HD-11EM cells in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3 was H2O2, and that treatment of the HD-11EM cells with glucose/glucose oxidase, a pure H2O2 generation system, alone stimulated an increase in TRAP mRNA expression, TRAP activity/cell, and multinucleated cell formation 24–48 hr after treatment. These results implicate H2O2 as being integrally involved in the 1α,25-(OH)2D3-mediated differentiation of HD-11EM into osteoclast-like cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

4B-Phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate, SOD (type I from bovine erythrocytes), ferricytochrome c (horse heart), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, scopoletin, horseradish peroxidase (type II), 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole, catalase (10,000–25,000 units per mg protein from bovine liver, thymol-free), Naphthol AS-BI Phosphate, Fast Red Violet LB salt, and L(+)tartaric acid were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO. All other chemicals, unless otherwise noted were from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ).

Culture of HD-11EM cells

The HD-11EM clonal cell line (Hsia et al., 1995) was kindly provided by Drs. Yi-Jan Hsia and Peter V. Hauschka (Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA), and was derived from the original HD-11 line of v-myc transformed chicken bone marrow cells (Beug et al., 1979) obtained from Dr. John S. Adams (UCLA School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA). Cells were maintained in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks (Falcon Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lanes, NJ) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM/F12; Sigma D-8900, Sigma) 200 ml supplemented with 1.5 ml penicillin-streptomycin (15070-014, Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY), 0.1 ml of Fungizone (Gibco BRL 15295-017), 1.5 ml of l-glutamine (25030-016, Gibco BRL), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. The cells did not survive in medium supplemented with 0.5% FCS. Cells were passaged once a week before reaching confluency by transferring 0.3 ml of the 1 ml of trypsinized cells to 20 ml of fresh medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FCS, and were fed 2–3 days after passage by complete media replacement. After approximately 60 doublings (3 months), cultures were replaced with cells from early passage stocks that had been frozen.

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) histochemistry

HD-11EM cells were plated at a density of 3 × 104 cells/well in a 6-well tissue culture plate (Falcon 3046; Becton Dickinson Labware), and cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS. 1 or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 (Biomol; Plymouth Meeting, PA) or vehicle [0.05% (v/v) final ethanol concentration] was added 3 days later when the cells reached 30–40% confluence. After 0, 6, 24, or 48 hr of culture, the cells were washed 2× in warm 37°C phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+(138 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 16.2 mM Na2HPO4, 1.47 mM KH2PO4, and 7.5 mM D-glucose, pH 7.35), and fixed for 5 min in fresh room temperature 0.5% paraformaldehyde containing 0.05% Triton X-100. To determine TRAP activity, the TRAP histochemical method was performed as reported by Cole and Walters (1987); 2 ml of histochemical media (pH 5.0) containing 50 mM tartrate, naphthol AS-BI phosphate (1 mg/ml), and the coupling dye fast red violet LB salt (2 mg/ml) were added to each well. The plates were incubated for 70 min at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. After incubation for 70 min, the histochemical media was discarded, the plates were washed in running tap water for 5 min, and then emptied. The cells were counter-stained with dilute Harris hematoxylin. Cells containing TRAP activity (regardless of number of nuclei), and observed as cells containing red precipitate, were counted from four randomly selected fields under an inverted light microscope (40×) and expressed as a percentage of the total cells counted in each field. The total number of cells per field, the number of TRAP stained cells, and the number of multinucleated cells (three or more nuclei) were counted using a computer-based image analysis program (Image Pro Plus provided by Phase 3 Imaging Systems, Milford, MA); images of the selected fields were acquired using a Sony DXC970MD three-chip color video camera mounted on a Zeiss IM inverted microscope.

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase activity assay

The relative amount of TRAP activity/cell was determined following the method of Modderman et al. (1991). HD-11EM were incubated and stimulated as described for the histochemical assay, except the coupling dye fast red violet LB salt was eliminated. After incubation for 70 min, the cells were washed for 5 min in running tap water, the plate was emptied and tapped upside-down on an absorbent pad to remove all liquid. The naphthol product was extracted by adding 0.5 ml of 0.1 N NaOH (pH 12.0) to each well, the plates were allowed to sit for 5 min at room temperature, then the plate was scraped (Fisher cell lifter 08-773-1) to ensure complete cell extraction from each well, and the cell extract was transferred to a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube. The procedure was repeated for each well, and the combined sample extractions were added to the appropriate Eppendorf tubes. The tubes were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 RPM to remove insoluble debris. Triplicate aliquots (200 µl) of each sample were placed in a 96-well cytoplate (CFCPN9610, Millipore Corporation; Bedford, MA) and the fluorescence was read at an excitation wavelength of 360 ± 40 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 ± 25 nm (Cytofluor 2350, Perseptive Bio-systems, Inc.; Cambridge, MA). Fluorescent emission of HD-11EM cell extracts after 70 min of incubation in the absence of substrate was equal to background fluorescent emission of 0.1 N NaOH, and was subtracted from each sample. The substrate itself had negligible fluorescence before and after incubation, so only the naphthol product was detectable as previously described (Modderman et al., 1991). Cell numbers were determined by counting cells in duplicate plates receiving the same stimulation media. The amount of product is reported as arbitrary units of fluorescence intensity/cell.

Cell counts and viability

At specified times, cells were washed in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hanks’ (HEPES) N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, released from the dish by trypsinization (Gibco BRL 25300-054), diluted in 10× PBS without Ca2+, and cell numbers were determined using a Coulter counter. Viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion according to the method of Kruse and Patterson (1973).

NADPH-oxidase immunocytochemistry

Cells were immunostained using standard indirect avidin-biotin techniques (Hsu et al., 1981) (Vectastain ABC-Elite, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) with mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAb) subclass IgG1 that recognize (1) human neutrophil cytochrome b558 alpha-and beta-subunits (449 and 48, respectively, 1:50 dilution, generous gift of Dr. Arthur Verhoeven, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands) (Verhoeven et al., 1989); (2) muscle-specific actin (HHF-35, 1:1000 dilution) (Tsukada et al., 1987) (Enzo Biochem., Inc., New York, NY). The cells were initially incubated in 1 ml of a solution of 50 ml of 3% H2O2 and 200 ml of methanol for 20 min at room temperature (RT) to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity. They were next incubated in 1 ml of 5 or 10% nonimmune horse or goat serum at RT for 20 min, then incubated with mAb solution at RT for 90 min or at 4°C for 15 hr. Biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (H + L) produced in horse (BA-2001, Vector Laboratories) was used to detect the bound mouse mAbs (RT for 60 min). This step was followed by incubation with avidin-biotin labeled-peroxidase and finally 0.1 M Tris buffer, pH 7.6, containing 2.5 mM 3,3′-di-aminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) and 0.02% H2O2 at RT for 2–4 min. Cells were counterstained with dilute Harris hematoxylin.

Ferricytochrome c assay for superoxide release

Superoxide production by the membrane associated NADPH-oxidase complex and release into the medium was measured at various intervals of time over a period of 2 hr at 37°C using the SOD-inhibitable reduction of ferricytochrome c (Cohen and Chovaniec, 1978). Data are presented for 30-min incubations. After 3 days in culture, the HD-11EM were washed in 37°C PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+, then stimulated optimally for 20 min at 37°C in media containing 0, 1, or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3. The stimulation medium was discarded, and the cells were washed in 37°C PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+. The assay mixture (2.5 ml) consisting of PBS, 0.04 mM ferricytochrome c, and where appropriate 241 U of SOD was added to remove superoxide, and the cells were incubated at 37°C. Addition of SOD resulted in an absorbance less than the vehicle-treated cells under all conditions of stimulation and was used as the baseline for that condition. Absorbances for duplicate well samples of each condition were read at 550 nm (ΔEm = 2.1 × 104 M−1 cm−1). The stimulation step was done separately, because 1α,25-(OH)2D3 interfered with the absorbance measurements for reduced ferricytochrome c.

Scopoletin assay for hydrogen peroxide generation

Hydrogen peroxide generation, resulting from the dismutation of superoxide, was measured continuously in the extracellular medium by following the oxidation of scopoletin over a period of 2 hr, using the method of Root et al. (1975) with the plate assay modification of Harpe and Nathan (1985). After 3 days, the cells were washed in warm 37°C PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+, and 1 or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 was added directly to the assay mix. The 37°C assay mixture (2.5 ml) contained PBS with 7.5 mM glucose, 4 µM scopoletin, 2 U of horse-radish peroxidase, 241 U of SOD, and 10 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (ATZ). ATZ was added to inhibit intracellular catalase, which converts membrane permeable H2O2 to H2O and O2. Inhibition of catalase improved assay reproducibility. Scopoletin oxidation by horseradish peroxidase in the presence of H2O2 was detected as a decrease in fluorescence emission of scopoletin at 450 ± 50 nm; excitation wavelength of 360 ± 40 nm (Cytofluor 2350, Perseptive Biosystems, Inc., Cambridge, MA). Fluorescence is read from the bottom of a 6-well plate containing the adherent HD-11EM cells. The H2O2 detected by this procedure is an underestimate, because fluorescence is quenched by the plastic and adhered cell layer, and an unknown amount of H2O2 passively enters the cells and escapes detection. Using the same assay mix to quantify production of H2O2 by glucose oxidase, less interference was observed because the adhered cell layer was absent.

Northern analysis for TRAP mRNA and v-myc mRNA

Total RNA was isolated by extraction of 3 × 105 cells/100 × 20 mm tissue culture dish in guanidinium thiocyanate (Sigma) and phenol/chloroform as described (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987). After isolation, RNA was ethanol precipitated, dissolved in 1 mM EDTA, and stored at −20°C. Quantity and purity were assessed by absorbance at 260 and 280 nm. RNA (20 µg) samples were separated on a 1% agarose (SeaKem GTG; FMC BioProducts; Rockland, ME), 1.1 M formaldehyde gel, and transferred by blotting onto nitrocellulose membranes (0.45 µm Protran 4 × 5.25 in; Schleicher & Schuell Inc.; Keene, NH) (Meinkoth and Wahl, 1984). Equivalent loading of RNA samples was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining of the ribosomal bands. The nitrocellulose membranes were baked, prehybridized, and hybridized with 32P-labeled cDNA probes (5–10 × 106 CPM/ml). Hybridization conditions were: 5× Denhardt’s solution without added BSA, 50% formamide (American Bioanalytical, Natick, MA), 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 800 mM NaCl, 0.1% Na pyrophosphate (Sigma), 10% dextran sulfate (Sigma), 100 µg/ml fish sperm DNA and 5% SDS (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Life Science Group, Hercules, CA). Probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (DuPont New England Nuclear; Wilmington, DE) by random primer extension (Oligolabelling kit; ProbeQuant G-50 columns; Pharmacia Biotech., Piscataway, NJ) (109 CPM/µg DNA). The cDNA probes used were a human TRAP cDNA clone (generous gift of Drs. Yi-Ping Li and Philip Stashenko, Forsyth Dental Center; Boston, MA); and a murine c-myc cDNA clone (Dr. K. Marcu, State University of New York, Stony Brook). Where indicated, mRNA levels were quantified by scanning densitometry (Arcus II flatbed scanner; AGFA). The autoradiogram band densities were analyzed using NIH Image version 1.7 software (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD). The expression of actin and GAPDH are not constant during differentiation of hematopoietic cells (Larsson et al., 1994), so band densities were normalized to the constitutive expression of the 28S ribosomal RNA ethidium bromide signal from the same gel lane.

Data analysis

Adequate HD-11EM samples were plated for each experiment so that duplicates of all treatments could be evaluated at the same time. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. To eliminate the day-to-day fluctuations in assay fluorescence or absorbance and to evaluate the treatment effects, the data were grouped by experiment and time point for statistical analysis. Statistical significance of differences between the vehicle-only (control) and treatment values for an individual experiment and time point was determined by a pairwise comparison of correlated groups using Student’s t test from the GB-STAT statistics software version 5.4.1.

RESULTS

Stimulation of HD-11EM cells with 1α,25-(OH)2D3

Stimulation of exponentially growing HD-11EM cells with 1α,25-(OH)2D3 was performed in medium for 48 hr, or in PBS for 20 min. The cells were plated at a density of 3 × 104 cells/well (6-well plate) in 2.5 ml of DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS. Three days later, cells were treated with vehicle [0.005% (v/v) final ethanol concentration] or 1 or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in medium (no media change after initial 3 days in culture) for 48 hr, or in PBS for 20 min. Cells treated in PBS for 20 min with vehicle or 1α,25-(OH)2D3 subsequently received fresh media without added 1α,25-(OH)2D3. Stimulation in PBS for 20 min was also used to assess the ability of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 to induce HD-11EM differentiation in the absence of serum and its 1α,25-(OH)2D3 binding factors.

Histochemical staining for TRAP activity and multinucleated cell formation in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3

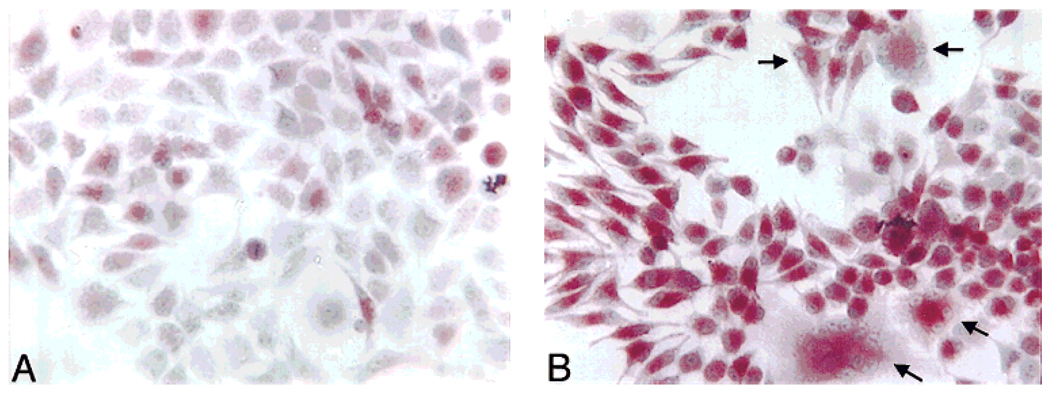

1α,25-(OH)2D3 has been reported to induce the differentiation of HD-11EM into osteoclast-like cells (Hsia et al., 1995; Hsia and Hauschka, unpublished data). To confirm and extend the findings of Hsia and Hauschka (unpublished data), the differentiation of HD-11EM into osteoclast-like cells in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3 was determined over time using both long- and short-term conditions of stimulation. TRAP activity and multinucleated cell formation were used as indicators of osteoclast formation. High levels of TRAP expression are believed to be restricted to the osteoclast under normal physiologic conditions; therefore expression of this enzyme is an important marker of osteoclast differentiation (Hammarstrom et al., 1971; Minkin, 1982; van de Wijngaert and Burger, 1986; Clark et al., 1989). Forty-eight hours after stimulation with 0, 1, or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3, the cells were washed, lightly fixed in 0.5% paraformaldehyde, and counterstained with Harris hematoxylin. Nuclei were round, and stained lightly except for prominent nucleoli. The number of cells containing TRAP activity and the number of multinucleated cells were counted from four randomly selected fields, and are expressed as a percentage of the total cells counted in each field. Approximately 17 ± 5% of the cells receiving vehicle only stained positive (red) for TRAP activity after 48 hr (Fig. 1A). An occasional multinucleated cell was observed in these cell preparations. Treatment with 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 dramatically increased multinucleated cell formation to three to four per field, and increased the percentage of the cells staining positive for TRAP activity to 72 ± 8% (Fig. 1B). TRAP activity was observed in 64 ± 2% of the cells after 1 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 stimulation. In addition to the increased percentage of cells staining for TRAP activity, there was an observable increase in the intensity of staining in individual cells that was uniform from one cell to another in response to either 1 or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3.

Fig. 1.

Histochemical staining for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity and multinucleated cell counts 48 hr after 1α,25-(OH)2D3 stimulation. HD-11EM were plated at a density of 3 × 104 cells/well of a six-well plate in 2.5 ml of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F12 media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. After 3 days in culture, the cells were stimulated with vehicle [0.005% (v/v) final ethanol concentration], 1, or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in medium (no media change at time of stimulation) for 48 hr. The cells were then washed, lightly fixed, and stained for TRAP activity. The total number of cells, the percentage of TRAP stained cells, and the number of multinucleated cells were determined at 48 hr. A: In cell preparations receiving vehicle only, an occasional multinucleated cell (three or more nuclei) was observed, and a low number of the cells contained a red precipitate, indicating TRAP activity. B: Treatment of the cells with 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 dramatically increased the multinucleated cell formation three- to fourfold, and uniformly increased the intensity of staining and the number of TRAP stained cells fourfold. This figure contains representative data from one of three independent experiments.

Similarly, TRAP activity at 48 hr was observed in 59 ± 6% of cells stimulated with 1 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in PBS for 20 min, and 87 α 6% stimulated with 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3. Of the cells receiving vehicle in PBS for 20 min, 36 ± 7.5% of the cells contained TRAP activity. The elevated percentage of cells containing TRAP activity after a short PBS incubation in the absence of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 stimulation may reflect the basal H2O2 production effect on TRAP activity (Fig. 4B) under conditions where no antioxidants contributed by serum or medium are present.

Fig. 4.

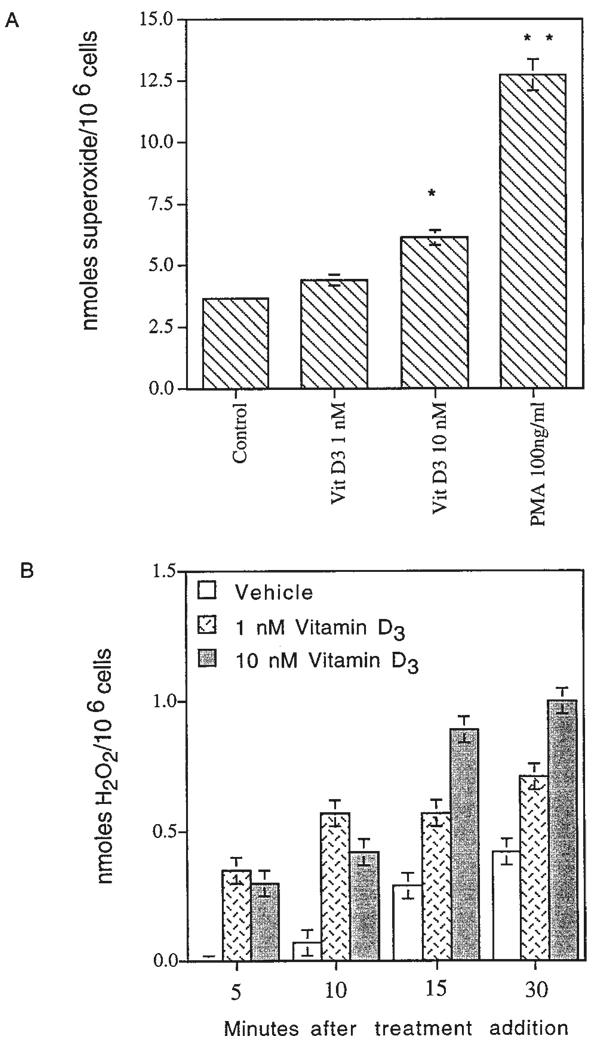

Superoxide and H2O2 production by HD-11EM in response to stimulation with 1α,25-(OH)2D3 or 4B-phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA). A: After 3 days in culture, the HD-11EM were stimulated in medium for 20 min with vehicle, 1, or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 or PMA 100 ng/ml. Cells were then incubated for 30 min at 37°C and the amount of superoxide produced was determined using the superoxide dismutase-inhibitable change in absorbance at 550 nm. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of four experiments. Results are significantly different from vehicle-only responses for each experiment at that time point: **, P < 0.01; and * P < 0.05. B: After 3 days in culture, the amount of H2O2 produced in response to vehicle, 1, or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at 37°C was measured continuously from 0 to 30 min. Representative data are presented from one experiment done in duplicate and performed three times.

Quantitative measurements of TRAP activity/cell at 0, 6, 24, and 48 hr after stimulation with 1α,25-(OH)2D3

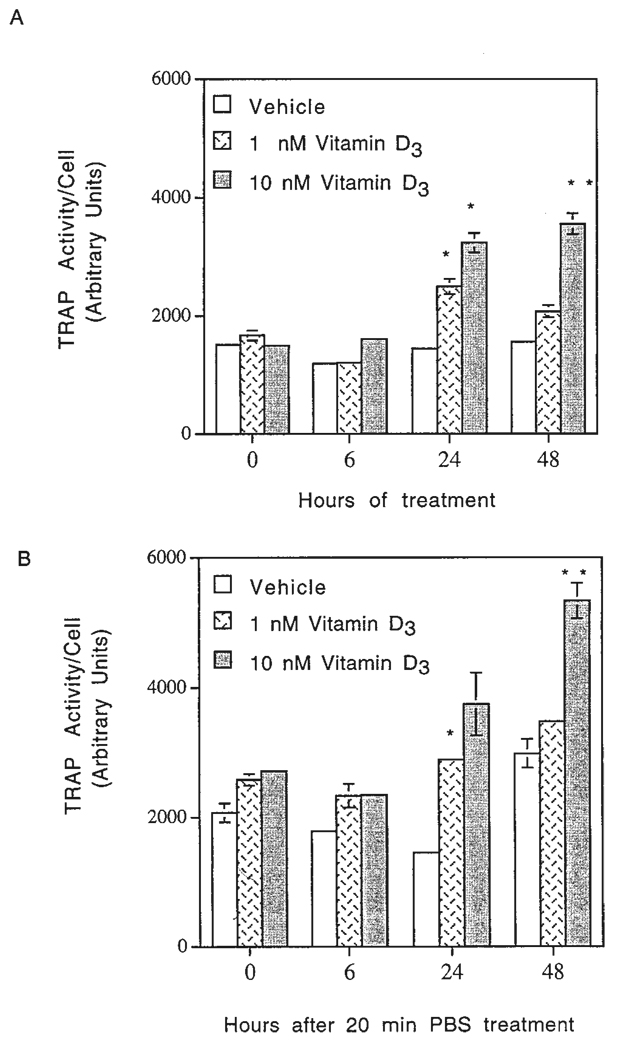

To further evaluate the effects of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 on TRAP activity/cell, quantitative measurements were performed at 0, 6, 24, and 48 hr after stimulation. As the results given in Figure 2A,B indicate, stimulation of the cells with 1α,25-(OH)2D3 resulted in a concentration- and time-dependent increase in TRAP activity/cell, although some variation in the response of HD-11EM to 1α,25-(OH)2D3 was observed depending on the condition of stimulation. TRAP activity in HD-11EM cells stimulated with 1 or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in medium peaked at 24 hr (Fig. 2A). In contrast, TRAP activity of HD-11EM cells stimulated in PBS for 20 min was increased at 24 hr, and continued to increase through 48 hr (Fig. 2B). The amount of basal TRAP activity also varied with the conditions of stimulation. Cells treated with vehicle in medium had a lower basal TRAP activity compared with cells treated in PBS for 20 min (Fig. 2A,B).

Fig. 2.

Quantitative measurements of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity/cell over a 48-hr period in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3. HD-11EM cells were plated and cultured as described in Figure 1. After 3 days in culture, the cells were stimulated with (A) vehicle, 1, or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in medium for 0, 6, 24, or 48 hr; or (B) vehicle, 1, or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min, followed by the addition of fresh medium without 1α,25-(OH)2D3 for 0, 6, 24, or 48 hr. Arbitrary units of TRAP activity/cell represent the amount of reaction product measured by fluorescence intensity. Cell numbers were determined by counting cells in duplicate plates receiving the same stimulation media. Data are expressed as the mean of four experiments ± SEM. Results are significantly different from vehicle-only responses at that time point: **, P < 0.01; and *, P < 0.05.

Regardless of whether the cells were stimulated 48 hr in medium or only 20 min in PBS, there was a consistent increase in TRAP activity/cell in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3, which was not observable until 24 hr after stimulation. The units of TRAP activity/cell correlated with the TRAP histochemical findings (Fig. 1) for both the time of appearance and the percentage of cells that contained TRAP staining. These findings also corroborate the histochemical finding that stimulation with 1α,25-(OH)2D3 for 20 min in serum-free medium is sufficient to induce TRAP activity 48 hr after treatment.

Cell counts 0, 24, and 48 hr after 1α,25-(OH)2D3 treatment

Another indicator of differentiation is a decrease in cell proliferation. The cell numbers at 0 hr equaled 3.0–4.0 × 105 cells/well. At 24 hr, the number of cells receiving vehicle equaled 6–9 × 105 cells/well, which correlated with the cell doubling time of 22 hr. Treatment of HD-11EM with 1 nM or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 suppressed proliferation at 24 hr compared with cells receiving vehicle only, although the decreases were not significant (P = 0.18). By 48 hr, there was a significant 5–15% reduction in cell proliferation in response to 1 or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3, respectively (P = 0.002; P = 0.003), approximating 0.5 to 1.5 × 105 fewer cells compared with the 1.0–1.5 × 106 cells/well for cultures receiving vehicle only. Cell viability observed by trypan blue exclusion was unaffected (>95% viable) by any of the treatments. The measured decrease in cell proliferation without loss of viability supports the inference that 1α,25-(OH)2D3 treatment leads to the increased differentiation of HD-11EM cells.

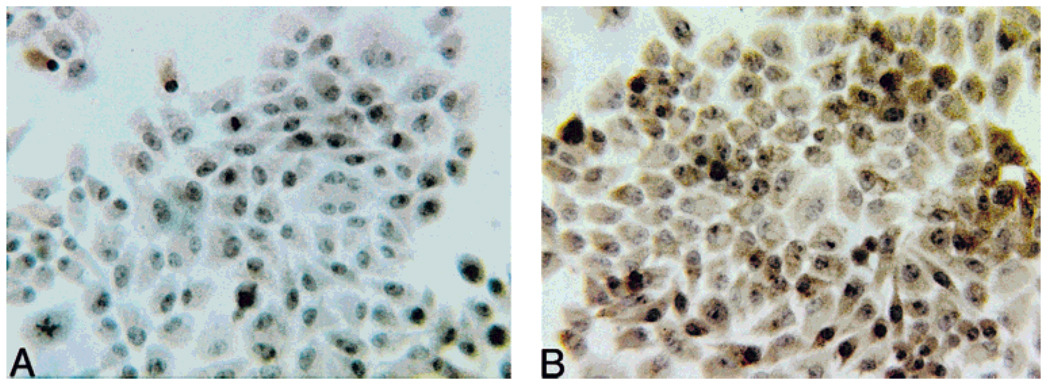

HD-11EM cells contain the NADPH-oxidase cytochrome b558 subunits

The NADPH-oxidase enzyme complex is responsible for production of extracellular superoxide in activated mature phagocytes and osteoclasts (Babior et al., 1973; Steinbeck et al., 1994). To confirm the presence of NADPH-oxidase in HD-11EM cells, immunocytochemical studies were performed using mAbs recognizing epitopes on the p22-phox and gp91-phox subunits of cytochrome b558 (Verhoeven et al., 1989). This cytochrome is unique to the NADPH-oxidase system (Parkos et al., 1987). After 3 days in culture the unstimulated cells were fixed and immunocytochemistry was performed. Immunostaining was observed in HD-11EM cells incubated with mAb recognizing the cytochrome b558 subunits. Figure 3B shows the brown oxidized-DAB immunoperoxidase positive staining observed in response to the mAb recognizing gp91-phox. No immunostaining was observed in the absence of mAb (Fig. 3A) or when a control mAb (HHF-35) of the same subclass IgG1 was used (data not shown). HHF-35 recognizes smooth muscle cell specific actin.

Fig. 3.

Expression of the unique cytochrome b558 subunits of NADPH-oxidase by HD-11EM cells. After 3 days in culture, the cells were washed, and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde. Immunocytochemical studies were done using the standard indirect avidin-biotin technique: (A) no immunostaining was observed in the absence of specific monoclonal antibody; (B) brown oxidized deposits of 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) immunoperoxidase products were observed in HD-11EM cells immunostained with a mAb recognizing the gp91-phox subunit of cytochrome b558.

Superoxide production by HD-11EM cells in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3

The presence of the NADPH-oxidase subunits indicated these cells were probably capable of producing superoxide if an appropriate stimulus was added to induce the activation or assembly of the various subunits of this enzyme system. To determine whether 1α,25-(OH)2D3 could activate NADPH-oxidase, the production of superoxide by HD-11EM cells in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3 was measured using the SOD-inhibitable ferricytochrome c reduction assay, a biochemical method specific for superoxide (Cohen and Chovaniec, 1978). Addition of SOD, which removes superoxide, inhibited the reduction of ferricytochrome c in response to all stimuli.

Figure 4 presents the amounts of superoxide produced by 106 cells over a period of 30 min after a 20-min period of stimulation. Stimulation of the cells with 1α,25-(OH)2D3 for 20 min was performed as a separate step, because the presence of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 interfered with absorbance readings of ferrocytochrome c at 550 nm, the wavelength used to monitor the reduction of ferricytochrome c by superoxide. Unstimulated HD-11EM continuously produced low amounts of superoxide (3–4 nmol/106 cells/30 min) (Fig. 4). Treatment of the cells with 1 or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in conditioned media resulted in a rapid and sustained increase in the production of superoxide. A 1.2-fold or a 1.7-fold increase in superoxide production was observed in response to 1 or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 compared with cells receiving vehicle only. Cells continued to produce superoxide for at least 90 min after stimulation and probably longer, although no measurements were performed beyond this time point. Treatment of the cells with 4B-phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA; 100 ng/ml), a known activator of NADPH-oxidase, resulted in a 3.5-fold increase in superoxide release (Fig. 4). Although treatment with PMA resulted in a more dramatic increase in superoxide release during the 30 min of measurement, 24 hr after treatment the cells lifted off of the plates and were no longer viable.

Inhibiting the production of superoxide by NADPH-oxidase with the addition of 1 µM diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), an inhibitor of flavoprotein function including the flavoprotein component of NADPH-oxidase, (Cross and Jones, 1986; Thannickal and Fanburg, 1995) prevented the increase in TRAP activity/cell in response 1α,25-(OH)2D3. However, the addition of DPI also caused extensive cell death by 24 hr. This finding suggests that low level production of ROS is necessary for HD-11EM cells to continue to proliferate or survive, as has been suggested for other cell types (for review see Burdon, 1995). Alternatively, HD-11EM cells may be unusually sensitive to toxic effects of DPI on cell metabolism, although this low concentration of DPI has not been reported to be cytotoxic for other cell types.

Spontaneous or enzymatic dismutation of superoxide to H2O2

To verify the dismutation of superoxide to H2O2 and determine the time of generation, kinetic measurements of H2O2 were performed using the scopoletin assay (Fig. 4B). Treatment of the cells with 1 or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 resulted in a rapid and sustained increase in the production of H2O2 during the first 30 min after stimulation. The mean amounts of H2O2 produced by 106 HD-11EM cells at 30 min in four experiments equaled: vehicle (1.4 ± 0.43 nmol H2O2//30 min); 1 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 (1.5 ± 0.33 nmol); 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 (1.9 ± 0.31 nmol). Compared with control HD-11EM cells fixed in 4.0% glutaraldehyde, these values were increased 1.12-, 1.33-, and 1.68-fold, respectively. The 1.68-fold increase in response to 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 was highly significant (P = 0.002). As detailed in the Materials and Methods section of this paper, this value may be an underestimate of the amount H2O2 produced by these cells because of fluorescence quenching and internalization of H2O2. However, these findings are consistent with the production of superoxide, and the subsequent early generation of H2O2 by spontaneous or enzymatic dismutation.

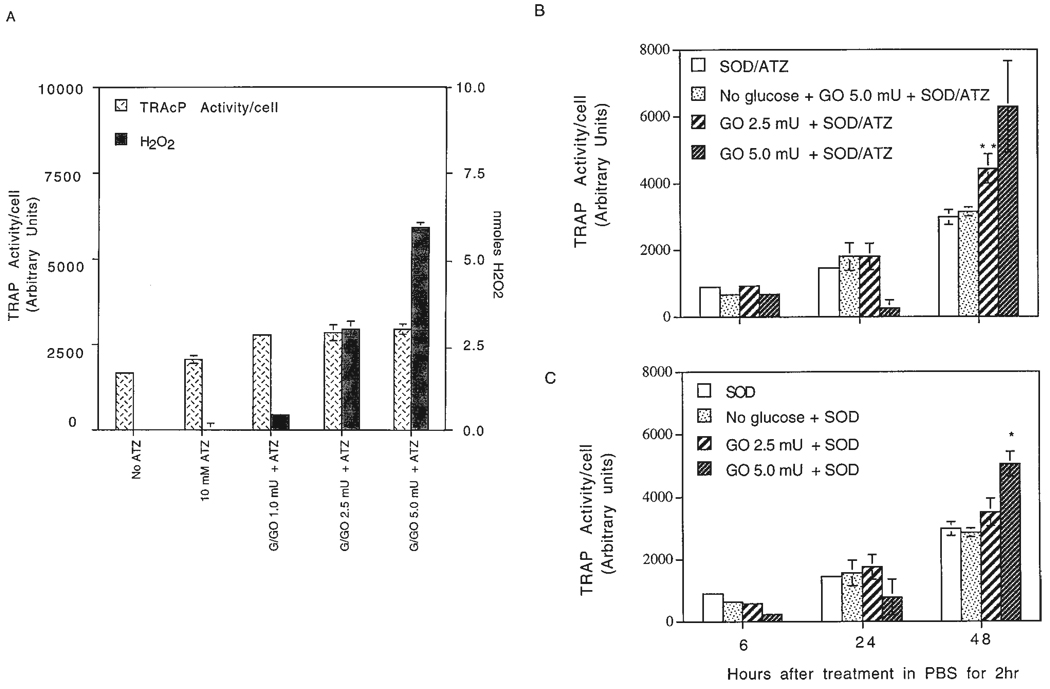

Biochemical measurements of TRAP activity in response to glucose oxidase, a pure and continuous source of low level amounts of H2O2

To determine whether the production of H2O2 in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3 might be involved in the subsequent increase in TRAP activity, HD-11EM were treated with nanomole amounts of H2O2. The amounts of H2O2 produced by glucose oxidase were measured over a period of 2 hr in an assay mix containing scopoletin, glucose, SOD (241 U/2.5 ml), and 10 mM ATZ. When glucose was omitted, no production of H2O2 by glucose oxidase was detected, and this served as a control for subsequent experiments with HD-11EM cells. By using a range of glucose oxidase concentrations, the amount of H2O2 produced by 1 to 5.0 mU of glucose oxidase at 30 min was determined to be within the nanomole range produced by HD-11EM in response to to 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at 30 min (Fig. 5A). HD-11EM cells were then incubated in PBS containing glucose, SOD, ATZ, and 1 to 5.0 mU of glucose oxidase for 2 hr. The cells were washed and fresh medium was added for the remainder of the 24-hr period. SOD was included to ensure that the basal HD-11EM cell production of superoxide was converted to H2O2, thus eliminating any effect of superoxide on the cells and preventing the possible inactivation of glucose oxidase by superoxide. An inhibitor of catalase, 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (ATZ), was also included in the incubations of HD-11EM cells with glucose oxidase. Catalase is one of the main enzymes responsible for the removal of intracellular H2O2 after it has entered the cell.

Fig. 5.

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity/cell over a 48-hr period in response to H2O2 generated by glucose oxidase. HD-11EM cells were stimulated for 2 hr in various media (2.5 ml/well of a six-well plate), the cells were washed, received fresh media, and at indicated time points measurements of TRAP activity/cell were done. A: To determine the amount of H2O2 produced at 30 min by 1.0 to 5.0 mU of glucose oxidase, and to evaluate the effects at 24 hr of increasing amounts of H2O2 on TRAP activity/cell, HD-11EM were incubated in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing glucose, superoxide dismutase (SOD) 241 U, 10 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (ATZ) (catalase inhibitor), and increasing units of glucose oxidase. B: To evaluate TRAP activity/cell at 6, 24, or 48 hr after treatment with amounts of H2O2 within the range produced by HD-11EM stimulated with 1 or 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3, HD-11EM were incubated for 2 hr with glucose, SOD 241 U, and 10 mM ATZ (SOD/ATZ); no glucose, SOD, ATZ, and glucose oxidase 5.0 mU (No glucose + GO 5.0 mU + SOD/ATZ); glucose, SOD, ATZ, and glucose oxidase 2.5 mU (GO 2.5 mU + SOD/ATZ) or 5.0 mU (GO 5.0 mU + SOD/ATZ). C: To determine the effects of H2O2 without inhibiting the intracellular catalase activity with ATZ, HD-11EM were treated for 2 hr with glucose and SOD (SOD); no glucose, SOD, and glucose oxidase 5.0 mU (No glucose/SOD); or glucose, SOD, and glucose oxidase 2.5 mU (GO 2.5 mU + SOD) or 5.0 mU (GO 5.0 mU + SOD). Arbitrary units of TRAP activity/cell represent the amount of product generated measured by fluorescence. Cell numbers were determined by counting cells in duplicate plates receiving the same stimulation media. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of four experiments. Results are significantly different from SOD ± ATZ responses at that time point: **, P < 0.01; and *, P < 0.05.

As the results in Figure 5A show, when glucose oxidase was omitted, 10 mM ATZ alone stimulated a small increase in the basal TRAP activity/cell at 24 hr. In the presence of glucose, 1.0 or 2.5 mU of glucose oxidase produced 0.5 and 3.0 nmol of H2O2/30 min, respectively, and stimulated a slight increase in TRAP activity at 24 hr compared with ATZ-treated cells. H2O2 production by 5.0 mU of glucose oxidase approximated 5.0–6.0 nmol of H2O2/30 min and an increase in TRAP activity was observed. Due to the greater amounts of H2O2, significant decreases in cell numbers of 10 to 15% were also observed, which is reflected by the large standard error of the mean 24-hr data presented in Figure 5B. At the extreme, 10 mU of glucose oxidase caused an almost complete loss of adherent and viable cells at 24 hr (~8.5 nmol of H2O2/30 min), and consequently, no TRAP activity could be detected (data not shown).

Having established the appropriate units of glucose oxidase to be used in these studies, the effect of H2O2 on TRAP activity/cell was determined at 6, 24, and 48 hr after treatment for 2 hr. No statistically significant increase in TRAP activity/cell was observed at 6 or 24 hr (Fig. 5B,C). At 48 hr, a concentration-dependent increase in TRAP activity/cell resulted from the addition of either 2.5 or 5.0 mU of glucose oxidase. The amounts of H2O2 produced by 2.5 mU of glucose oxidase resulted in a significant increase in TRAP activity/cell at 48 hr, and the TRAP activity/cell doubled with the addition of 5.0 mU of glucose oxidase (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5C presents the TRAP activity/cell when ATZ was omitted from the treatment. Lower TRAP activity responses were observed, supporting the supposition that H2O2 is entering the cells and being removed by intracellular catalase. Significant increases in TRAP activity/cell were observed at 48 hr in response to 5.0 mU of glucose oxidase. The addition of 4,000 U of catalase in the absence of the inhibitor ATZ, resulted in a 50% reduction in detectable H2O2 and a similar reduction in TRAP activity (data not shown).

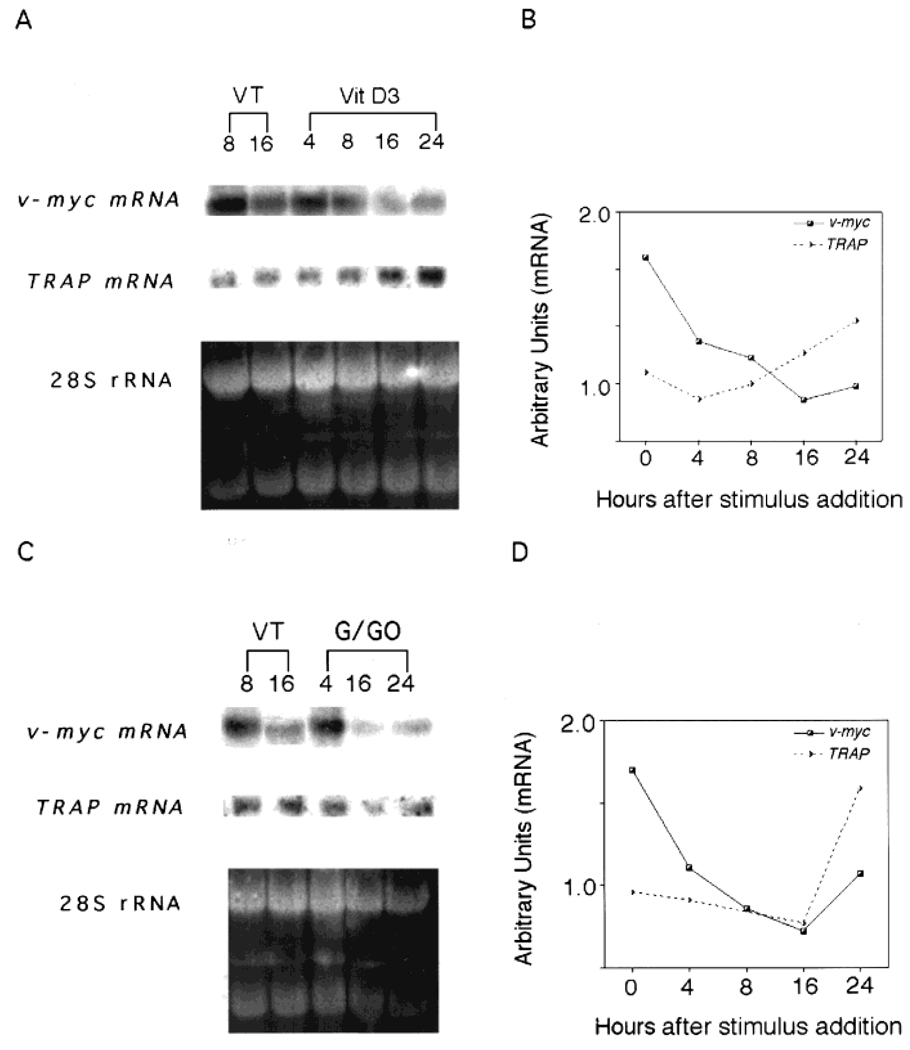

Northern analysis demonstrates increased TRAP mRNA expression and decreased v-myc mRNA in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3

To establish further the effects of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 and H2O2 on TRAP activity and cell differentiation, TRAP and v-myc mRNA amounts were quantified in exponentially growing HD-11EM cells. The cells were exposed to either 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in conditioned medium or 2.5 mU of glucose oxidase/ATZ; total mRNA was isolated, and the relative amounts of TRAP and v-myc mRNA transcripts were determined by Northern analysis. After treatment of HD-11EM with 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3, TRAP mRNA initially declined at 4 hr, then accumulated, reaching significantly elevated levels by 16 hr and peaking at 24 hr (Fig. 6A,B). In contrast, v-myc mRNA was highly expressed in HD-11EM cells and decreased dramatically after treatment with 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 (Fig. 6A,B). Cells receiving vehicle only (VT) showed little change in TRAP mRNA over a 24-hr period, but did show some spontaneous decrease in v-myc mRNA at 16 hr. However, the decrease in v-myc mRNA at 16 hr in vehicle-treated cells was considerably less than the observed decrease in 1α,25-(OH)2D3-treated cells. Regulation of mRNA amounts over time in response to 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 for both TRAP and v-myc relative to the 28S rRNA band are presented in Figure 6B.

Fig. 6.

1α,25-(OH)2D3 or H2O2 increase tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) mRNA and decrease the amounts of v-myc mRNA. HD-11EM were grown for 3 days in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F12 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, then stimulated in (A) conditioned medium with 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 or (C) with glucose/glucose oxidase 2.5 mU, 241 U SOD, and 10 mM ATZ in PBS for 2 hr, and then fresh medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS. Total RNA was isolated at the indicated time points and analyzed by Northern blot procedures; filters were analyzed for TRAP mRNA, washed, and reprobed for v-myc mRNA. B: The amount of mRNA relative to 28S rRNA over time in HD-11EM treated with 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 or (D) with glucose/glucose oxidase 2.5 mU, SOD, and ATZ. These figures contain representative data from one of three independent experiments.

Treatment of HD-11EM with 2.5 mU of glucose oxidase/ATZ caused an initial decrease in TRAP mRNA, followed by a subsequent accumulation of mRNA between 16 and 24 hr, reaching peak levels at 24 hr (Fig. 6C,D). In vehicle-treated cells, v-myc mRNA gradually declined over the next 16 hr. A slightly greater decrease in v-myc mRNA was observed in response to 2.5 mU of glucose oxidase/ATZ treatment. The regulation of mRNA amounts over time in response to 2.5 mU of glucose oxidase/ATZ for both TRAP and v-myc relative to the 28S rRNA band are presented in Figure 6D.

DISCUSSION

The present findings demonstrate that the clonal myelomonocytic cell line HD-11EM produces superoxide and H2O2 in an early response to stimulation by 1α,25-(OH)2D3. 1α,25-(OH)2D3 also stimulates a concentration and time-dependent increase in the expression of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) mRNA and activity; an enzyme that is predominantly expressed in mature osteoclasts. In addition, 1α,25-(OH)2D3 induces multinucleated cell formation, decreases cell proliferation, and decreases v-myc mRNA, supporting a role for 1α,25-(OH)2D3 as a hormone capable of inducing the differentiation of HD-11EM into osteoclast-like cells. The production of superoxide and H2O2 precedes the increase in TRAP mRNA expression in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3, and treatment of HD-11EM with H2O2 mimics the 1α,25-(OH)2D3-mediated increases in TRAP mRNA and activity, multinucleated cell formation, as well as the decreases in v-myc mRNA. These results implicate H2O2 as being integrally involved in the differentiation of HD-11EM into osteoclast-like cells. Despite the fact that the extracellular product of the activated NADPH-oxidase is superoxide, our focus on H2O2 rather than superoxide was based on the fact that H2O2 is longer lived and can freely pass through membranes into the cell after originating as a dismutation product of superoxide on the outside of the cell and, unlike superoxide, H2O2 is known to activate several signal transduction pathways and affect transcription factor activity. Our findings also agree with those of Suda et al. (Suda, 1991; Suda et al., 1993), who reported that production of H2O2 by mouse calvarial organ cultures stimulated with 1α,25-(OH)2D3 is associated with the increased formation of osteoclasts from progenitor cells.

It is generally accepted that mature phagocytic leukocytes, some B lymphocytes, mesangial cells, and mature osteoclasts contain the enzyme NADPH-oxidase (Babior et al., 1973; Maly et al., 1989; Radeke et al., 1991; Steinbeck et al., 1994). In the present study, we show that HD-11EM cells express the gp91-phox cytochrome b subunit of NADPH-oxidase (Fig. 3), and produce superoxide in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3 or PMA, a known activator of NADPH-oxidase (Fig. 4). In contrast, the undifferentiated myelomonocytic cell line HL-60 and monoblastic cell line U937 do not express the gp91-phox subunit of NADPH-oxidase, and do not produce superoxide until stimulated to undergo further differentiation (Barker et al., 1988; Obermeier et al., 1995).

This is the first report that stimulation of a cell with 1α,25-(OH)2D3 enhances the activation of NADPH-oxidase and increases the basal release of superoxide and the formation of its dismutation product, H2O2 (Fig. 4). It is unlikely that the observed activation of NADPH-oxidase is dependent on binding of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 to the vitamin D3 receptor (VDR) and a genomic response (VDRE), based on the relatively short 5–10 min response time between the addition of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 and the increased generation of H2O2. Rapid, nongenomic responses of cells to 1α,25-(OH)2D3 are not unusual, given previous reports that the effects of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 on HL-60, U937, and other cells types are mediated through pathways independent of the classic nuclear VDR (Desai et al., 1986; Norman et al., 1992; Bhatia et al., 1995; Sylvia et al., 1996). In HL-60 cells, 1α,25-(OH)2D3 has been reported to increase the generation of diacylglycerol and protein kinase C activity within seconds of initial 1α,25-(OH)2D3 exposure (Desai et al., 1986; Norman et al., 1992). In our study, PMA, a well-known protein kinase C activating agent and activator of NADPH-oxidase, stimulated a rapid increase in superoxide release (Fig. 4A), which could be detected as early as 1–2 min after treatment. Taken together, the previously reported activation of protein kinase C in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3, and the increases in superoxide release in response to PMA observed in the present study, suggest that a possible common signal transduction pathway involving protein kinase C may result in the activation of NADPH-oxidase and production of superoxide by HD-11EM in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3.

To investigate a role for H2O2 in the differentiation of HD-11EM cells, a glucose/glucose oxidase system was used to deliver H2O2 in nanomole amounts consistent with amounts produced by HD-11EM in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3. Glucose oxidase has the advantage of not only being a continuous source of H2O2, but also a system that exclusively generates H2O2 and not superoxide, making interpretation of the results more direct. Commercial preparations of glucose oxidase are also essentially protease free, unlike preparations of xanthine oxidase commonly used to generate superoxide. We observed that a relatively small concentration range exists for H2O2-induced differentiation of HD-11EM cells (Fig. 5). At higher concentrations of H2O2, (10.0 mU of glucose oxidase or PMA stimulation) cytotoxicity is observed by the failure of these cells to exclude trypan blue.

In addition to the role of H2O2 as a local factor involved in osteoclast differentiation, nanomolar concentrations of H2O2, thought to be produced by endothelial cells, have been implicated in the enhancement of osteoclast resorptive activity (Bax et al., 1992; Zaidi et al., 1993a). Whether mediating differentiation and/or functional activation or motility, H2O2 has been shown in other cell types to stimulate both receptor tyrosine kinase-mediated phosphorylation as well as non-receptor tyrosine kinase activity and to inhibit tyrosine phosphatases (Koshio et al., 1988; Heffetz et al., 1990; Fantus et al., 1989). In addition to regulating second messenger signaling pathways, H2O2 is also recognized as a powerful activator of NF-kB, a transcription factor that increases the gene expression of a number of cytokines involved in inflammation related processes (Scheck et al., 1991). Hydrogen peroxide may therefore mediate the observed, long-term increase in TRAP gene transcription (Fig. 6A,B) indirectly through the activation of NF-kB and the expression of cytokines known to affect osteoclast differentiation, such as IL-6 (Suda et al., 1995, 1997). The expression of cytokines may be of particular importance because the TRAP promoter contains at least one candidate transcription factor binding sequence for NF-IL-6. A second potentially active transcription factor binding sequence within the TRAP promoter is AP-1 (Reddy et al., 1993, 1995). Hydrogen peroxide has also been reported to inhibit the binding of the transcription factors c-Jun and c-Fos to AP-1 sites (for review see Burdon, 1995), and in fact, we observed an initial decrease in TRAP mRNA in response to either 1α,25-(OH)2D3 or H2O2 (Fig. 6), which might reflect a transient decrease in transcription factor binding to AP-1 DNA sequences within the TRAP promoter. Our findings that a known activator of NF-kB can induce the differentiation of HD-11EM cells into osteoclast-like cells is of particular interest, as a recent report by Iotsova et al. (1997) demonstrates that osteoclast differentiation did not take place in NF-kB p50 and p52 double knockout mice. The NF-kB double knockout mice, similar to c-fos knockout mice (Grigoriadis et al., 1994) develop osteopetrosis resulting from decreased bone resorption caused by a defect in osteoclast formation. Another similarity of the NF-kB double knockout mice and the c-fos knockout mice is increased numbers of bone marrow macrophages and osteoclast precursors. Whether regulation of NF-kB and/or c-Fos transcription factor activities is involved in the differentiation of HD-11EM in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3 or H2O2 awaits further study.

Because v-myc expression is known to play a pivotal role in regulating the proliferation and differentiation of v-myc transformed cells (Tikhonenko et al., 1995), v-myc mRNA amounts were evaluated in exponentially growing HD-11EM cells treated with either 1α,25-(OH)2D3 or H2O2. Both 1α,25-(OH)2D3 and H2O2 caused a >60% decrease in the steady-state v-myc mRNA amounts relative to vehicle-treated cells at 4 hr, well before detectable changes in proliferation and differentiation (Fig. 5A–D). Based on the decrease in v-myc mRNA in response to both agents, our findings suggest that 1α,25-(OH)2D3 may regulate v-myc mRNA amounts in HD-11EM cells by activating NADPH-oxidase and increasing the production of H2O2. However, 1α,25-(OH)2D3 may also work through a genomic VDR-dependent pathway, as reported for the induced differentiation of U937 cells (Larsson et al., 1994). U937 cells do not produce H2O2 (Obermeier et al., 1995), but differentiate into monocytic cells in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3, after a decrease in c-myc expression and an increase in the expression of Mad, a protein that negatively regulates the transactivating function of c-Myc (Larsson et al., 1994). 1α,25-(OH)2D3 has also been reported to increase the expression of the cdk cell cycle inhibitor p21 in U937 cells by means of a VDR-dependent process (Liu et al., 1996). A possible VDR genomic event cannot be ruled out in the present study of osteoclast differentiation; however, our data show that, although less sustained compared with 1α,25-(OH)2D3, H2O2 can mediate a decrease in v-myc mRNA.

The present study was designed to investigate whether production of H2O2 by HD-11EM cells, in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3, could mediate their differentiation into osteoclast-like cells. Our findings indicate that HD-11EM cells express the cytochrome b558 subunits of NADPH-oxidase and produce superoxide/ H2O2 after stimulation with 1α,25-(OH)2D3. H2O2 treatment of HD-11EM cells with a pure and continuous H2O2-generation system, similar to 1α,25-(OH)2D3, increased TRAP mRNA, TRAP activity/cell, and multinucleated cell formation, which are markers of osteoclast differentiation. These results implicate H2O2 as being integrally involved in the differentiation of HD-11EM into osteoclast-like cells, and suggest that H2O2 may be an important local factor produced by osteoclast progenitor cells in response to 1α,25-(OH)2D3 and perhaps other osteotropic hormones.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Yi-Ping Li and Dr. Philip Stashenko for the human osteoclast TRAP cDNA probes; Dr. Yi-Jan Hsia and Dr. Peter Hauschka for the HD-11EM cells; and Ruth Schillig for her excellent technical assistance.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Contract grant number: DE-08507; Contract grant number: DE-11082; Contract grant number: AR41392; Contract grant number: AR44046.

Abbreviations

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TRAP

tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

- 1α,25-(OH)2D3

1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

- VDR

1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor.

LITERATURE CITED

- Athanasou NA. Current concepts review cellular biology of bone-resorbing cells. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1996;78:1096–1112. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199607000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior BM, Kipnes RS, Curnutte JT. Biological defense mechanisms: The production by leukocytes of superoxide, a potential bactericidal agent. J. Clin. Invest. 1973;52:741–744. doi: 10.1172/JCI107236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker KA, Orkin SH, Newburger PE. Expression of the X-CGD gene during induced differentiation of myeloid leukemia cell line HL-60. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988;8:2804–2810. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.7.2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Shavit Z, Teitelbaum SL, Reitsma P, Hall A, Pegg LE, Trial J, Kahn AJ. Induction of monocytic differentiation and bone resorption by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:5907–5911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.19.5907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax BE, Alam ASMT, Banerji B, Bax CMR, Bevis PJR, Stevens CR, Moonga BS, Blake DR, Zaidi M. Stimulation of osteoclastic bone resorption by hydrogen peroxide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;183:1153–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beug H, von Kirchback A, Doderlein G, Conscience JF, Graf T. Chicken hematopoietic cells transformed by seven strains of defective avian leukemia viruses display three distinct phenotypes of differentiation. Cell. 1979;18:375–390. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia M, Kirkland JB, Meckling-Gill KA. Monocytic differentiation of acute promyelocytic leukemia cells in response to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is independent of nuclear receptor binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:15962–15965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.15962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdon RH. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in relation to mammalian cell proliferation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995;18:775–794. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00198-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger EH, Van der Meer JWM, Van der Gevel JS, Gribnan JC, Thesingh CW, Van Furth R. In vitro formation of osteoclasts from long-term cultures of bone mononuclear phagocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1982;156:1604–1614. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.6.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers TJ, Horton MA. Failure of cells of the mononuclear phagocyte series to resorb bone. Calcif. Tissue Internat. 1984;36:556–558. doi: 10.1007/BF02405365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers TJ, Owens JM, Harrersley G, Jat PS, Noble MD. Generation of osteoclast-inductive and osteoclastogenic cell lines from the H-2KbtsA58 transgenic mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:5578–5582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SA, Ambrose WW, Anderson TR, Terrell RS, Toverud SU. Ultrastructural localization of tartrate-resistant, purple acid phosphatase in rat osteoclasts by histochemistry and immunocytochemistry. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1989;4:399–405. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650040315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia PF, Krivit W, Cervenka J, Clawson CC, Kersey JH, Kim TH, Nesbit ME, Ramsay MKC, Warkenton PI, Teitelbaum SL, Kahn AJ, Brown DM. Successful bone-marrow transplantation for infantile malignant osteopetrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1980;302:701–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198003273021301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen HJ, Chovaniec ME. Superoxide generation by digitonin-stimulated guinea pig granulocytes. A basis for a continuous assay for monitoring superoxide production and for the study of the activation of the generating system. J. Clin. Invest. 1978;61:1081–1087. doi: 10.1172/JCI109007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole AA, Walters LM. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase in bone and cartilage following decalcification and cold-embedding in plastic. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1987;35:203–206. doi: 10.1177/35.2.3540104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross AR, Jones OTJ. The effect of the inhibitor diphenylene iodonium on the superoxide-generating system of neutrophils. Specific labelling of a component polypeptide of the oxidase. Biochem. J. 1986;237:111–116. doi: 10.1042/bj2370111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai SS, Appel MC, Baran DT. Differential effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on cytosolic calcium in two human cell lines (HL-60 and U-937) J. Bone Miner. Res. 1986;1:497–501. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650010603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantus IG, Kadota S, Deragon G, Foster B, Posner BI. Pervanadate [peroxide(s) of vanadate] mimics insulin action in rat adipocytes via activation of the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8864–8871. doi: 10.1021/bi00448a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischman DA, Hay ED. Origin of osteoclasts from mononuclear leucocytes in regenerating newt limbs. Anat. Rec. 1962;143:329–338. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091430402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frediani U, Becherini L, Lasagni L, Tanini A, Brandi ML. Catecholamines modulate growth and differentiation of human preosteoclastic cells. Osteoporos. Int. 1996;6:14–21. doi: 10.1007/BF01626532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett RI, Boyce BF, Oreffo ROC, Bonewald L, Poser J, Mundy GR. Oxygen-derived free radicals stimulate osteoclastic bone resorption in rodent bone in vitro and in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;85:632–639. doi: 10.1172/JCI114485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattei V, Bernabei PA, Pinto A, Bezzini R, Ringressi A, Formigli L, Tanini A, Attadia V, Brandi ML. Phorbolester induced osteoclast-like differentiation of a novel human leukemic cell line (FLG 29.1) J. Cell Biol. 1992;116:437–447. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.2.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothlin G, Ericsson JE. On the histogenesis of the cells in fracture callus. Electron microscopic and autoradiographic observations in parabiotic rats and studies on labeled monocytes. Virchows Arch. Cell Pathol. 1973;12:318–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriadis AE, Wang Z-Q, Cecchini MG, Hofstetter W, Felix R, Fleisch HA, Wagner EF. c-Fos: A key regulator of osteoclast-macrophage lineage determination and bone remodeling. Science. 1994;266:443–448. doi: 10.1126/science.7939685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarstrom LE, Hanker JS, Toverud SU. Cellular differences in acid phosphatase isoenzymes in bone and teeth. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1971;78:151–167. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpe JDl, Nathan CF. A semi-automated micro-assay for H2O2 release by human blood monocytes and mouse peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. Methods. 1985;78:323–336. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffetz D, Buskin K, Dror R, Zick Y. The insulinomimetic agents H2O2 and vanadate stimulate protein tyrosine phosphorylation in intact cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:2896–2902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia Y-J, Kim J-K, Damoulis PD, Hauschka PV. Osteoclastic properties of clonal HD-11 cells are regulated by 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1995;10 Suppl 1:S424. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H. Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: A comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) techniques. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1981;29:577–580. doi: 10.1177/29.4.6166661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iotsova V, Caamano J, Loy J, Yang Y, Lewin A, Bravo R. Osteopetrosis in mice lacking NF-kB1 and NF-kB2. Nat. Med. 1997;11:1285–1289. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn AJ, Simmons DJ. Investigations of cell lineage in bone using a chimaera of chick and quail embryonic tissue. Nature (Lond.) 1975;258:325. doi: 10.1038/258325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshio O, Akanuma Y, Kasuga M. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor and its tyrosine kinase activity in intact cells. Biochem. J. 1988;250:95–101. doi: 10.1042/bj2500095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse PF Jr, Patterson MK Jr, editors. Tissue Culture: Methods and Applications. New York: Academic Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L-G, Pettersson M, Oberg F, Nilsson K, Luscher B. Expression of mad, mxi1, max and c-myc during induced differentiation of hematopoietic cells: Opposite regulation of mad and c-myc. Oncogene. 1994;9:1247–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Lee M-H, Cohen M, Bommakanti M, Freedman LP. Transcriptional activation of the Cdk inhibitor p21 by vitamin D3 leads to the induced differentiation of the myelomonocytic cell line U937. Genes Dev. 1996;10:142–153. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly F-E, Nakamura M, Gauchat J-F, Urwyler A, Walker C, Dahinden CA, Cross AR, Jones OTG, De Weck AL. Superoxide-dependent nitroblue tetrazolium reduction and expression of cytochromeb−246 components by human tonsillar B lymphocytes and B cell lines. J. Immunol. 1989;142:1260–1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolagas SC. Role of cytokines in bone resorption. Bone. 1995;17 Suppl 2:63S–67S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00180-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks SC., Jr The origin of osteoclast. J. Oral Pathol. 1983;12:226–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1983.tb00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinkoth J, Wahl G. Hybridization of nucleic acids immobilized on solid supports. Anal. Biochem. 1984;138:267–284. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90808-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkin C. Bone acid phosphatase: Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase as a marker of osteoclast function. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1982;34:285–290. doi: 10.1007/BF02411252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modderman WE, Tuinenburg-Bol Raap AC, Nijweide PJ. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase is not an exclusive marker for mouse osteoclasts in cell culture. Bone. 1991;12:81–87. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(91)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman AW, Nemere I, Zhou LX, Bishop JE, Lowe KE, Msiyer AC, Collins ED, Taoka T, Sergeev I, Farach-Carson MC. 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3, a steroid hormone that produces biologic effects via both genomic and nongenomic pathways. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1992;41:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90349-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermeier H, Sellmayer A, Danesch U, Aepfelbacher M. Cooperative effects of interferon-γ on the induction of NADPH oxidase by retinoic acid or 1α,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 in monocytic U937 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1269:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(95)00095-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osdoby P, Krukowski M, Collin-Osdoby P. Experimental systems for studying osteoclast biology. In: Rifkin BR, Gay CV, editors. Biology and Physiology of the Osteoclast. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Inc.; 1992. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Parkos CA, Allen RA, Cochane CG, Jesaitis AJ. Purified cytochrome b from human granulocyte plasma membrane is comprised of two polypeptides with relative molecular weights of 91,000 and 22,000. J. Clin. Invest. 1987;80:732–742. doi: 10.1172/JCI113128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn JM, McGee JO, Athanasou NA. Cellular and hormonal factors influencing monocyte differentiation to osteoclastic bone-resorbing cells. Endocrinology. 1994;134:2416–2423. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.6.8194468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radeke HH, Cross AR, Hancock JT, Jones OTG, Nakamura M, Kaever V, Resch K. Functional expression of NADPH oxidase components (α- and β- subunits of cytochrome b558 and 45-kDa flavoprotein) by intrinsic human glomerular mesangial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:21025–21029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raisz LG, Trummel CL, Holick MF, DeLuca HF. 1,25-dihydroxy-cholecalciferol: A potent stimulator of bone resorption in tissue culture. Science. 1972;175:768–769. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4023.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SV, Scarcez T, Windle JJ, Leach RJ, Hundley JE, Chirgwin JM, Chou JY, Roodman GD. Cloning and characterization of the 5′-flanking region of the mouse tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) gene. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1993;8:1263–1270. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650081015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SV, Hundley JE, Windle JJ, Alcantara O, Linn R, Leach RJ, Boldt DH, Roodman GD. Characterization of the mouse tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) gene promoter. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1995;10:601–606. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodman GD, Ibbotson KJ, MacDonald BR, Kuehl TJ, Mundy GR. 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 causes formation of multinucleated cells with several osteoclast characteristics in cultures of primate marrow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:8213–8217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodman GD. Osteoclastic models. application of bone marrow cultures to the study of osteoclast formation and osteoclast precursors in man. Calcif Tissue Int. 1995;56 Suppl 1:S22–S23. [Google Scholar]

- Root RK, Metcalf J, Oshino N, Chance B. H2O2 release from human granulocytes during phagocytosis. I. Documentation, quantitation, and some regulating factors. J. Clin. Invest. 1975;55:945–955. doi: 10.1172/JCI108024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheck R, Rieber P, Baeuerle PA. Reactive oxygen intermediates as apparently widely used messengers in the activation of the NF-kB transcription factor and HIV-1. EMBO J. 1991;10:2247–2258. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07761.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JH, Kukita A, Ohki K, Katsuki T, Kohashi O. In vitro differentiation of the murine macrophage cell line BDM-1 into osteoclast-like cells. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4285–4292. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbeck MJ, Appel WH, Verhoeven AJ, Karnovsky MJ. NADPH-oxidase expression and in situ production of superoxide by osteoclasts actively resorbing bone. J. Cell Biol. 1994;126:765–772. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.3.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda N. Role of free radicals in bone resorption. Kokubyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1991;58:603–612. doi: 10.5357/koubyou.58.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda N, Morita I, Kuroda T, Murota S. Participation of oxidative stress in the process of osteoclast differentiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1157:318–323. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(93)90116-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda T, Udagawa N, Nakamura I, Miyaura C, Takahashi N. Modulation of osteoclast differentiation by local factors. Bone. 1995;17:87S–91S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00185-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda T, Nakamura I, Jimi E, Takahashi N. Regulation of osteoclast function. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1997;12:869–879. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.6.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvia VL, Schwartz ZVI, Ellis B, Helm SH, Gomez R, Dean DD, Boyan BD. Nongenomic regulation of protein kinase c isoforms by the vitamin D metabolites 1α,25-(OH)2D3 and 24R,25-(OH)2D3. J. Cell. Physiol. 1996;167:380–393. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199606)167:3<380::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Yamana H, Yoshiki S, Roodman DG, Mundy GR, Jones SJ, Boyde A, Suda T. Osteoclast-like cell formation and its regulation by osteotropic hormones in mouse bone marrow cultures. Endocrinology. 1988;122:1373–1382. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-4-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa NG, Allen TD, Lajtha LG, Onions D, Jarret O. Generation of osteoclasts in vitro. J. Cell Sci. 1981;47:127–137. doi: 10.1242/jcs.47.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal VJ, Fanburg BL. Activation of an H2O2-generating NADH oxidase in human lung fibroblasts by transforming growth factor β1. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:30334–30338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonenko AT, Black DJ, Linial ML. v-Myc is invariably required to sustain proliferation of infected cells but in stable cell lines becomes dispensable for other traits of the transformed phenotype. Oncogene. 1995;11:1499–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada T, Tippins D, Gordon D, Ross R, Gown AM. HHF35, a muscle-actin-specific monoclonal antibody. I. Immunocytochemical and biochemical characterization. Am. J. Pathol. 1987;126:51–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Akatsu T, Tanaka H, Sasaki T, Nishihari T, Kosa T, Martin TJ, Suda T. Origin of osteoclasts: mature monocytes and macrophages are capable of differentiating into osteoclasts under a suitable microenvironment prepared by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:7260–7264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wijngaert FP, Burger EH. Demonstration of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase in un-decalcified, glycolmethacrylate-embedded mouse bone: A possible marker for (pre)osteoclast identification. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1986;34:1317–1323. doi: 10.1177/34.10.3745910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven AJ, Bolscher BGJM, Meerhof LJ, van Zwieten R, Keijer J, Weening RS, Roos D. Characterization of two monoclonal antibodies against cytochrome b558 of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Blood. 1989;73:1686–1694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DG. Osteopetrosis cured by temporary parabiosis. Science. 1973;180:875. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4088.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DG. Control of bone resorption by hematopoietic tissue. The induction and reversal of congenital osteopetrosis in mice through use of bone marrow and splenic transplants. J. Exp. Med. 1975;142:651–653. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.3.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi M, Alam ASMT, Bax BE, Shankar VS, Bax CMR, Gill JS, Pazianas M, Huang CL-H, Sahinoglu T, Moonga BS, Stevens CR, Blake DR. Role of the endothelial cell in osteoclast control: New perspectives. Bone. 1993a;14:97–102. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(93)90234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi M, Alam ASMT, Shankar VS, Bax BE, Bax CMR, Moonga BS, Bevis PJR, Stevens C, Blake DR, Pazianas M, Huang CLH. Cellular biology of bone resorption. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1993b;68:197–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1993.tb00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]