Abstract

Using data from a 6-year longitudinal follow-up sample of 240 youth who participated in a randomized experimental trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families with children ages 9–12, the current study tested alternative cascading pathways by which the intervention decreased symptoms of internalizing disorders, symptoms of externalizing disorders, substance use, and risky sexual behavior, and increased self-esteem and academic performance in mid-to late-adolescence (15–19 years old). It was hypothesized that the impact of the program on adolescent adaptation outcomes would be explained by progressive associations between program-induced changes in parenting and youth adaptation outcomes. The results supported a cascading model of program effects in which the program was related to increased mother-child relationship quality, which was related to subsequent decreases in child internalizing problems, which then was related to subsequent increases in self-esteem and decreases in symptoms of internalizing disorders in adolescence. The results also were consistent with a model in which the program was related to increased maternal effective discipline, which was related to subsequent decreases in child externalizing problems, which then was related to subsequent decreases in symptoms of externalizing disorders, less substance use and better academic performance in adolescence. There were no significant differences in the model based on level of baseline risk or adolescent gender. These results provide support for a cascading pathways model of child and adolescent development.

Keywords: PREVENTIVE INTERVENTION, PARENTAL DIVORCE, MEDIATION, DEVELOPMENTAL PATHWAYS, ADOLESCENCE

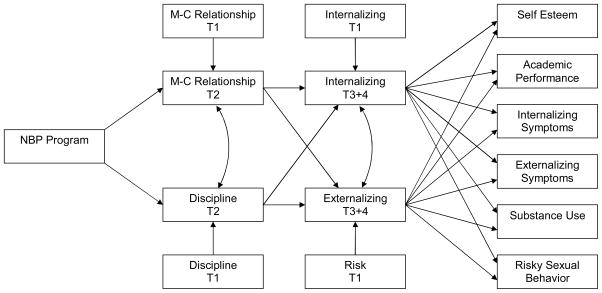

One of the central scientific goals of developmental psychopathology is to unravel the developmental pathways that lead to positive and negative adaptation outcomes (e.g., Cicchetti & Sroufe, 2000; Masten, Burt & Coatsworth, 2006). One approach to studying developmental pathways is to model cascading effects, or the progressive associations among various domains of functioning (Masten et al., 2005; Rutter & Sroufe, 2000). In these models, change in one area of functioning is viewed as triggering a progression of consequences that can have extensive developmental effects on other areas of adaptation in later developmental periods (Sameroff, 2000). The present study examined a cascade model using data from a group of at-risk youth, children from divorced families. These families were involved in a randomized trial of a preventive intervention (the New Beginnings Program, NBP), which was designed to influence developmental outcomes. We examined a developmental cascade model to test whether program effects on adolescent adaptation outcomes could be explained by pathways in which intervention-induced improvements in parent-child relationship quality and effective discipline led to decreased internalizing problems and externalizing problems in middle childhood, which in turn led to improved outcomes in multiple domains of functioning in adolescence (see Figure 1). Below, we briefly review the research on divorce as a risk factor and describe the findings from the program of research on the NBP. We then summarize the research that provides support for the links in the proposed model and describe the contributions of the current study.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model using Developmental Cascades to Explain the Effects of the NBP on Adolescent Adaptation Outcomes

Note. M-C is mother-child.

Parental divorce is a risk factor

It is well documented that parental divorce increases the risk for mental health problems, low academic attainment, and low social competence in youth (e.g., Amato, 2001; Amati & Keith, 1991; Hetherington et al., 1992; Lansford et al., 2006). Meta-analyses of 92 studies published through the 1980s (Amato & Keith, 1991) and 67 studies in the 1990s (Amato, 2001) showed that youth in divorced families have more externalizing, internalizing, substance use, and academic problems than those in non-divorced families. These differences occurred across age and gender and were slightly larger for more recent studies. Although the effect sizes were generally modest, the high prevalence of divorce means that its impact on population rates of problem outcomes is substantial (Cohen, 1996; Scott, Mason, & Chapman, 1999). However, although divorce increases risk, most youth exposed to parental divorce do not experience serious adjustment problems. Across multiple studies, about 70 to 75% of youth from divorced families did not experience clinically significant mental health problems (e.g., Hetherington, Bridges & Insabella, 1998; Wolchik, Sandler, Millsap & Luecken, 2006). Identifying pathways that explain differences in adaptation following this family transition is a critical research issue that has both applied and theoretical implications.

The NBP

The NBP is a theory-based preventive intervention developed to improve developmental outcomes of children who experience parental divorce. The program was designed to modify empirically-supported risk and protective factors that have been associated with outcomes in correlational studies of children from divorced families (Wolchik et al., 1993; Wolchik, West, et al., 2000; Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss & Winslow, 2007). The conceptual model underlying our research on the prevention of short- and long-term post-divorce problems combines elements from a person-environment transactional framework and a risk and protective factor model (Sandler, Wolchik, Winslow, & Schenck, 2006). Derived from epidemiology (Institute of Medicine, 1994), the risk and protective factor model posits that the likelihood of mental health problems is affected by exposure to risk factors and the availability of protective resources. Person-environment transactional models posit that dynamic person-environment processes underlie individual development across time. Aspects of the social environment (e.g., parenting) affect the development of child problems and competencies, which in turn influence the social environment and development of child competencies and problems at later developmental stages (Cicchetti & Sroufe, 2000; Sameroff, 2000). Cummings, Davies and Campbell’s (2000) cascading pathway model integrates these two models into a developmental framework. From this perspective, stressful events, such as divorce, can lead to an unfolding of failures to resolve developmental tasks and increase susceptibility to mental health problems and impairment in developmental competencies. Parenting is viewed as playing a central role in facilitating children’s successful adaptation, and the skills and resources developed in successful resolution of earlier developmental tasks are important tools for managing future challenges.

Two randomized trials of the NBP tested a program designed to promote positive parenting (Wolchik et al., 1993; Wolchik, West et al., 2000). The second trial also tested whether a child component strengthened program effects by comparing the parenting program alone to a dual-component program (i.e., parenting program plus a child coping program). Analyses in both trials indicated that participation in the parenting program significantly improved parenting and reduced child mental health problems at post-test compared to the control condition. The parenting plus child coping condition did not produce additive effects on child mental health outcomes at post-test, 6-month follow-up or 6-year follow-up (Wolchik et al., 2002; Wolchik, West et al., 2000). Thus, the data from the two active conditions were combined to provide a more parsimonious perspective on the program effects at the 6-year follow-up of the sample in the second trial. At the six-year follow-up, positive program effects were found on a wide range of youth outcomes, including internalizing problems, externalizing problems, diagnosis of mental disorder in the last year, symptoms of mental disorder, alcohol use, marijuana use, other drug use, polydrug use, number of sexual partners, grade point average and self-esteem (Wolchik et al, 2007). For several effects at post-test and short- and long-term follow-ups, benefits were greater for those with higher baseline risk scores on a composite measure of environmental stressors and externalizing problems (Dawson-McClure et al., 2004; Wolchik et al., 1993; 2002; 2007; Wolchik, West et al., 2000).

Mediational analyses showed that the effects of the NBP parenting program on internalizing problems at post-test were accounted for by improvements in mother-child relationship quality, and effects on externalizing problems at post-test and 6-month follow-up were mediated by improvement in relationship quality and effective discipline (Tein, Sandler, MacKinnon, & Wolchik, 2004). Zhou, Sandler, Millsap, Wolchik, and Dawson-McClure (2008) found that program-induced improvements in maternal effective discipline at post-test mediated the intervention effect on adolescents’ GPA at the 6-year follow-up. In a separate model, program-induced improvement in mother–child relationship quality mediated the intervention effect on adolescents’ mental health problems for those with high baseline risk for maladjustment. Examining parental monitoring and substance use at the 6-year follow-up, Soper, Wolchik, Tein and Sandler (in press) found that monitoring mediated program effects to reduce alcohol and marijuana use, polydrug use, and other drug use for those with high baseline risk for maladjustment. These results provide strong support for the critical role of positive parenting in improving adaptation outcomes of youth in divorced families, and for the differential mediational role of parent-child relationship quality and effective discipline. However, these studies do not elucidate the cascading pathways through which changes in these aspects of parenting may lead to adolescent outcomes six years later. From the cascading pathways perspective, we hypothesized that the intervention-induced improvements in parenting would be related to reductions in internalizing problems and externalizing problems in middle childhood and that these changes would be related to adolescent functioning in these aspects of functioning as well as others, such as academic performance, substance use and sexual behavior. Below, we discuss the empirical support for the proposed linkages.

Parenting and childhood mental health problems

Numerous studies with youth from divorced families show protective effects of high quality mother-child relationships (e.g., Amato & Keith, 1991; Hetherington et al, 1992; Kelly & Emery, 2003; Sandler, Miles, Cookston, & Braver, 2008; Wolchik, Wilcox, Tein & Sandler, 2000) and consistent and appropriate parental discipline (Forgatch, Patterson, & Skinner, 1988; Wolchik, Wilcox et al., 2000). For example, Wolchik, Wilcox and colleagues (2000) showed that relations between divorce stressors and internalizing problems and externalizing problems were strongest for children who reported both low warmth and low consistency of discipline; those who reported both high warmth and consistent discipline had the fewest internalizing problems and externalizing problems. Longitudinal studies with other at-risk groups and normative samples have also shown that poor parent-child relationships and ineffective discipline predict increases in both externalizing problems and internalizing problems for boys and girls during middle childhood (e.g., Hipwell, Keenan, Kasza, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Bean, 2008; Ingoldsby, Shaw, Winslow, Schonberg, Gilliom, & Criss, 2006). For example, Hipwell and colleagues (2008) found that low parent-child warmth and harsh punishment uniquely predicted increases in conduct problems, whereas only low warmth predicted depressed mood at age 12 in a 6-year prospective study of girls.

Evaluations of parent training interventions also provide support for the role of parenting on child adaptation outcomes (Kaminski, Valle, Filene, & Boyle, 2007; Lochman & van den Steenhoven, 2002; O’Connell, Boat & Warner, 2009). In their meta-analytic review, Kaminski and colleagues (2007) found the greatest effect sizes were for parent training programs that included skills to increase effective discipline (i.e., use of time out and parent consistency) and positive parent-child interactions and communication. Thus, in both non-experimental and experimental research, two dimensions of parenting — parent-child relationship quality and effective discipline— have been consistently shown to influence externalizing problems and internalizing problems in middle childhood.

Internalizing problems and externalizing problems from childhood to adolescence

According to the cascading pathways theoretical model, mental health problems in middle childhood are expected to lead to a variety of adaptation problems in adolescence (see Figure 1). High continuity of externalizing problems and moderate continuity of internalizing problems have been demonstrated from middle childhood to adolescence (e.g., Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Masten et al., 2005). Externalizing problems have also been shown to predict increases in internalizing symptoms over time (Kiesner, 2002; Lahey, Loeber, Burke, Rathouz, & McBurnett, 2002). Despite a positive concurrent relation between internalizing problems and externalizing behaviors, higher levels of internalizing problems have predicted decreases in externalizing problems over time (Burt, Obradović, Long, & Masten, 2008; Pine, Cohen, Cohen, & Brook, 2000). This latter finding may be due to greater behavioral inhibition among children with internalizing problems, which reduces the likelihood of future risk-taking behaviors, deviant peer association and rule-breaking behaviors (Burt et al., 2008).

Externalizing problems and internalizing problems in middle childhood predict other adaptation problems in adolescence as well. Externalizing problems have been shown to predict increases in substance use problems in adolescence (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Stice, Barrera, & Chassin, 1998), decreases in academic competence (Masten et al., 2005), and increases in teenage pregnancy (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999), controlling for internalizing problems. Internalizing problems during middle childhood have predicted low self-esteem in adolescence, controlling for externalizing problems (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999). Although some differential effects have been reported for internalizing problems and externalizing problems in childhood on outcomes in adolescence (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999), studies have not yielded consistent findings of differential effects.

The current study

The current study used the NBP data set to test alternative developmental pathways leading to multiple adolescent adaptation outcomes. As shown in Figure 1, we hypothesized that participation in the NBP would be related to improved mother-child relationship quality and increases in effective discipline. Program-induced improvements in effective discipline and relationship quality were expected be associated with decreases in internalizing problems and externalizing problems in middle childhood, and reductions in these mental health problems were expected to be associated with increases in self-esteem and academic performance, and decreases in internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, substance use, and risky sexual behavior in adolescence.

This study extends the findings of previous investigations that have examined mediators of the NBP effects on adaptation outcomes in childhood (Tein et al., 2004) and adolescence (Soper et al., in press; Zhou et al., 2008) in several ways. First, this study uses a cascading pathways framework to investigate the processes that intervene between the program-induced changes in parent-child relationship quality and effective discipline and the longer-term program effects on adolescent adaptation outcomes, including all possible pathways between children’s internalizing problems and externalizing problems and adolescent adaptation outcomes. Second, unlike the previous longitudinal studies which have conducted mediational analyses for one variable at a time, the current study examined multiple mediators at multiple time points. Finally, by including multiple pathways and outcomes in one model, the present study directly tests the impact of each pathway on different adolescent outcomes while controlling for other potential pathways.

Method

Participants

Participants were identified primarily through court records of divorce decrees in a large Southwestern metropolitan county (20% were recruited through media advertisements or word of mouth). Eligibility criteria, described in detail elsewhere (Wolchik, West et al., 2000), included the following: 1) divorce occurred within the past two years; 2) there was at least one child between 9 and 12 in the family; 3) the mother was the primary residential parent; and 4) the mother was not remarried or living with a partner and was not planning to remarry during the trial. Because of the preventive nature of the intervention and ethical concerns, families were excluded and referred for treatment if the child endorsed an item about suicidality or exhibited severe levels of depressive symptomatology or externalizing problems at pre-test. In families with multiple children in the age range, one was randomly selected to be interviewed.

The sample consisted of 240 families who were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: 1) a mother-only program (MP, n = 81 families), 2) a dual-component mother program plus child program (MPCP; separate, concurrent groups for mothers and children, n = 83 families), or 3) a literature control condition (LC, n = 76 families). Comparison of intervention acceptors and refusers (i.e., those who refused to participate in the evaluation of the intervention but completed the pre-test interview, N = 59) that used multivariate analyses indicated that baseline child maladjustment and family income-to-needs positively predicted intervention enrollment (Winslow, Bonds, Wolchik, Sandler, & Braver, 2009). The three intervention conditions did not differ on child mental health problems nor demographic variables at pre-test. Comparisons of the control, mother, and mother-plus-child conditions on the demographic variables revealed no significant group differences at the 6-year follow-up (Wolchik et al., 2002). Attrition analyses found no significant interactions between group membership and attrition status (i.e., data available at follow-up versus missing at follow-up) on the mental health outcomes of externalizing problems or internalizing problems (Wolchik et al., 2002).

The parenting program targeted four empirically-supported correlates of children’s post-divorce mental health problems: mother-child relationship quality, effective discipline, interparental conflict and father’s access to the child. There were 11 group sessions (1.75 hr.) and two individual sessions (1 hr.). Six sessions focused on mother-child relationship quality and three focused on discipline. The other sessions addressed interparental conflict, father’s access to the child, and ways to continue using the program skills after the group ended. The program employed multiple empirically-supported behavior change strategies based on social learning and cognitive behavioral theories. The groups, which consisted of about 8 to 10 mothers, were co-led by two Master’s-level clinicians. See Wolchik et al. (2007) for more information about the parenting program.

The 11-session child program focused on increasing effective coping, reducing negative thoughts about divorce-related stressors and improving mother-child relationship quality. Several clinical methods derived from social learning and social cognitive theory were used. Children were taught to recognize and label feelings (e.g., Stark, 1990) and use deep-breathing relaxation (Weissberg, Caplan, & Bennetto, 1988). The program also included segments on effective problem solving (e.g., Weissberg et al, 1988), positive cognitive reframing (Meichenbaum, 1986), challenging common negative appraisals (Stark, 1990), and giving “I-messages” (Guerney, 1978). Skills were introduced through presentations, videotapes, or modeling by group leaders. Children practiced the program skills through games, role-plays, or, in the case of communication skills, in a conjoint session with their mothers. The groups were co-led by two Master’s-level clinicians.

Both mothers and children in the literature control condition were sent three books on divorce adjustment and syllabi to guide their reading over a 6-week period.

At pre-test, the average age of the children was 10.4 (SD = 1.1); 49% were girls. Mothers’ mean age was 37.3 years (SD = 4.8); 98% had at least a high school education. Mother’s ethnicity was 88% Caucasian, non-Hispanic; 8% Hispanic; 2% African American; 1% Asian/Pacific Islander; and 1% other. On average, families had been separated and divorced for 2.2 years (SD = 1.4) and 1.0 year (SD = 0.5), respectively. At the 6-year follow-up, adolescents ranged from 15 to 19 years old (M = 16.9 years; SD = 1.1); 80% and 11% lived with their mothers and fathers, respectively, and 9% lived independently.

Procedure

Families were interviewed on five occasions: pre-test (T1), post-test (T2), and 3-month (T3), 6-month (T4), and 6-year (T5) follow-up. The current study employed data from all waves. Trained staff conducted separate home interviews with parents and youth. Confidentiality was explained and parents and youth signed consent/assent forms. Families received $45 compensation at T1, T2, T3 and T4; parents and youth each received $100 compensation at T5. All 240 families randomized to condition completed assessments at T1 and T2. The participation rate was 98% at T3 and T4, and 91% at T5.

Measures

We constructed composite scores for constructs on which multiple measures or ratings from multiple reporters were collected. This procedure helps to ensure that the full breadth of each construct is represented, minimize measurement errors (Epstein, 1983), and reduce the experiment-wise error rate. Composite scores were constructed by standardizing each measure and averaging the scores.

Mother-Child Relationship Quality

At T1 and T2, we used 10 items from the acceptance subscale (16 items) and 10 items from the rejection subscale (16 items) of the revised Child Report of Parenting Behavior Inventory (CRPBI) to assess mother and child report of mother-child relationship quality (Schaefer, 1965; Teleki, Powell, & Dodder, 1982). Children completed reduced versions of the acceptance and rejection subscales at T2 due to concerns about the length of the child battery; thus, in the current study we used the reduced version for mothers to be consistent across reporters. In a previous study of children in divorced families, correlations between the reduced and full scales were r = .95, p < .001 and r = .96, p < .001 for mother reports of acceptance and rejection respectively, and r = .95, p < .001 and r = .96, p < .001 for child reports of acceptance and rejection respectively (Program for Prevention Research, 1993). Sample items are: “You almost always spoke to (child) with a warm and friendly voice” and “Your mother wasn’t very patient with you” for the acceptance and rejection subscales, respectively. The acceptance and rejection subscales were summed to form a total acceptance/rejection scale for mothers and children. The internal consistency reliability coefficients for the acceptance/rejection scale were .78 and .81 for mothers at T1 and T2, respectively, and .84 and .89 for child report of acceptance/rejection at T1 and T2, respectively. Mothers and children completed the open family communication subscale (10 items) of the Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale (Barnes & Olson, 1982). A sample item is “(child) discussed his/her beliefs with you without embarrassment.” The reliability coefficients were .72 and .75 for mothers at T1 and T2, and .82 and .87 for children at T1 and T2. Mothers and children also completed an abbreviated 7-item version of the Family Routines Inventory (Jensen, Boyce, & Hartnett, 1983). These items were selected because they specifically reflected dyadic interactions between mother and child. A sample item is “You regularly talked about things that happened each day.” The reliability coefficients were .67 and .63 for mothers at T1 and T2, and .70 and .76 for children at T1 and T2. Mother and child reports on all measures were standardized and averaged to create a multi-measure, multi-reporter composite.

Effective Discipline

Mothers and children completed the 8-item inconsistent discipline subscale of Teleki et al.’s (1982) adaptation of the CRPBI (Schaefer, 1965). Sample items included “You soon forgot a rule you had made” and “Your mother punished you for doing something one day but ignored it the next.” The internal consistency reliability coefficients were .81 and .80 for mothers at T1 and T2, and .72 and .73 for children at T1 and T2, respectively. Mothers completed the appropriate/inappropriate discipline strategies subscale (14 items; T1 α = .70, T2 α = .71) from the Oregon Discipline Scale (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1991). These items were used to compute the ratio of appropriate-to-inappropriate discipline. Sample items include “When (child) misbehaved, how often did you get him/her to correct or make up for the problem or do a payback?” and “When (child) misbehaved, how often did you slap or hit him/her with your hand?” for appropriate and inappropriate discipline, respectively. Mothers also completed the follow-through subscale (11 items; T1 α = .80, T2 α = .76) from the Oregon Discipline Scale (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1991). A sample item is “If you warned (child) that he/she would be punished if he/she did not stop doing something, how often did you actually punish him/her if they did not stop?” These four scales (i.e., mother report of inconsistent discipline, child report of inconsistent discipline, mother report of appropriate-to-inappropriate discipline and mother report of follow-through) were standardized and averaged to create a composite.

Children’s Externalizing Problems

Mother report of externalizing problems during the past month was measured with the 33-item externalizing subscale of the widely used Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983). At T1 α = .87, at T3 α = .87, and at T4 α = .87. Extensive research has documented the reliability and validity of this subscale (Achenbach, 1991a). Children completed 27 items from the aggression and delinquency subscales of the Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991b) (T1 α = .87, T3 α = .86, and T4 α = .88). This scale has been found to be sensitive to detecting intervention-induced change and has acceptable internal consistency reliability (Achenbach, 1991b). Given the short period of time between T3 and T4 (3 months), we summed reports of externalizing problems across T3 and T4 and then averaged across mother and child report to create a composite variable.

Children’s Internalizing Problems

Mothers completed the 31-item internalizing subscale of the CBCL, which includes withdrawn and anxious/depressed behaviors and somatic complaints (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983). At T1 α = .88, at T3 α = .86, and at T4 α = .85. Adequate reliability and validity for this subscale have been reported (Achenbach, 1991b). Youth report of depression was measured using the 27-item Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1981). The CDI has been shown to have high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and validity (Saylor, Finch, & Spirito, 1984). In this study, α was .76 at T1, .78 at T3, and .80 at T4. Youth report of anxiety was assessed using the 28-item Revised Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richard, 1978). Convergent and discriminant validity has been supported by high positive correlations with other trait measures of anxiety (Reynolds & Paget, 1981). In this study, α was .88 at T1, .91 at T3, and .91 at T4. A composite of reports on the CDI and CMAS was formed as the mean of the standardized scores. We summed reports of internalizing problems at T3 and T4 to create a composite variable. Mother and child measures of internalizing problems were then standardized and averaged.

Adolescent Symptoms of Externalizing and Internalizing Disorders

Symptoms of externalizing disorders and internalizing disorders at T5 were assessed using mother and adolescent versions of the computer-assisted Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, et al., 2000). Based on DSM-IV criteria, this highly structured diagnostic interview is designed for use by non-clinical interviewers. The modules used in the project assessed symptoms over the past year. Total symptom scores were derived separately for internalizing disorders (i.e., agoraphobia, generalized anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, eating disorders, and major depression) and externalizing disorders (i.e., conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), according to symptoms endorsed by either the parent or adolescent.

Adolescent Substance use

Adolescents completed the Monitoring the Future Scale (MTF; Johnston, Bachman, & O’Malley, 1993) at T5. This measure has been widely used to assess national drug, alcohol and smoking trends. Monitoring the Future drug use scores have been shown to have substantial correlations with delinquency (Bachman, Johnston, & O’Malley, 1996). The following scores were used: frequency of marijuana use and alcohol use in the past year, which were rated on a 7-point scale (1 = “0 occasions”; 7 = “40 or more occasions”). The frequency of marijuana use and alcohol use subscales were standardized and averaged to form a substance use scale.

Adolescent Risky Sexual Behavior

At T5, adolescents reported on the number of partners with whom they had sexual intercourse in the past year using a single item from DeLamater and MacCorquodale’s (1979) Sexual Behavior Inventory.

Adolescent Self-Esteem

The 6-item Global Self-Worth subscale of Harter’s (1985) Self Perception Profile for Children (SPPC) was administered to the adolescents to assess global self-esteem (α = .86). Sample items included, “Some teens are very happy being the way they are” and “Some teens don’t like the way they are leading their lives.” Scores on this measure have been negatively related to youth reports of depressive symptoms and clinical depression (Renouf & Harter, 1990).

Adolescent Academic Performance

Archival data were collected from school records for all participants, regardless of whether they were currently attending school. Questionnaires were mailed to school principals, along with copies of Authorization to Release Information forms. The questionnaire requested the unweighted (based on 4.0 scale) cumulative GPA for high school, which was used as the measure of academic performance at T5.

Baseline Risk

Previous analyses have shown that program benefits were greater for those youth who at pre-test were at risk for developing later adjustment problems (e.g., Dawson-McClure et al., 2004; Wolchik et al.,2002; 2007; Wolchik, West et al., 2000). Given that the overall impact of the NBP depends on level of risk at baseline, it is also possible that the mechanisms by which NBP affects adaptation outcomes in adolescence differs for high and low risk groups. Thus, the risk index developed by Dawson-McClure and colleagues (2004) was included as a predictor and potential moderator in the current analyses. This index consisted of a composite of the two baseline (T1) measures that were the most consistent predictors of adaptation problems in the literature control group at T5: externalizing problems (as assessed using the CBCL and YSR; Achenbach, 1991b; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983) and environmental stress (i.e., composite of negative events that occurred to the child, interparental conflict, maternal distress, reduced contact with father, and per capita income at pre-test). Dawson-McClure et al. (2004) showed that the risk index has an odds ratio of 8.14 for mental disorder, indicating that the odds of having a diagnosis at 6-year follow-up were 8.14 times higher for youth with high levels of risk than for youth with low levels of risk, as assessed six years earlier. For additional information on this composite, see Dawson-McClure et al. (2004).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. The correlations were in the expected direction, such that mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline at T2 had significant negative associations with internalizing problems and externalizing problems at T3+4, and internalizing problems and externalizing problems at T3+4 had significant associations with adolescent adaptation outcomes at T5. It is important to note that the bivariate relations between the program condition and most adolescent outcomes were not significant, which is consistent with previous investigations reporting that the effects of the NBP were conditioned on level of risk at baseline (Dawson-McClure et al., 2004; Wolchik et al., 2002; 2007; Wolchik, West et al., 2000). Moreover, the correlations did not suggest multicollin earity among the study variables. The skewness (3.51) and kurtosis (14.86) of risky sexual behavior exceeded the cutoff values of 2 for skewness and 7 for kurtosis (West, Finch, & Curran, 1995). Previous research has also reported skewness for health risk behaviors in community samples (e.g., Chang, Halpern, & Kaufman, 2007; Turbin, Jessor, & Costa, 2000). To account for the non-normality of risky sexual behavior, we used the bootstrapping method for parameter estimations and tests of the mediation effects in all models. Bootstrapping methods are robust to violations of normality and appropriate for use with small sample sizes (Efron, 1981).

Table 1.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Program | – | ||||||||||||||

| 2. M-C Relationship T1 | −.08 | – | |||||||||||||

| 3. M-C Relationship T2 | .12 | .67 | – | ||||||||||||

| 4. Effective Discipline T1 | −.04 | .54 | .41 | – | |||||||||||

| 5. Effective Discipline T2 | .18 | .36 | .56 | .62 | – | ||||||||||

| 6. Risk T1 | .13 | −.29 | −.28 | −.38 | −.26 | – | |||||||||

| 7. Externalizing Problems T3+4 | −.01 | −.30 | −.38 | −.34 | −.30 | .60 | – | ||||||||

| 8. Internalizing Problems T1 | .06 | −.31 | −.28 | −.37 | −.20 | .57 | .41 | – | |||||||

| 9. Internalizing Problems T3+4 | −.02 | −.30 | −.33 | −.24 | −.24 | .49 | .61 | .65 | – | ||||||

| 10. Externalizing Symptoms T5 | .03 | −.18 | −.18 | −.32 | −.17 | .43 | .45 | .31 | .33 | – | |||||

| 11. Internalizing Symptoms T5 | −.01 | −.13 | −.19 | −.18 | −.07 | .32 | .35 | .43 | .46 | .51 | – | ||||

| 12. Self-Esteem T5 | .01 | .17 | .12 | .09 | .09 | −.20 | −.25 | −.30 | −.40 | −.39 | −.44 | – | |||

| 13. Substance Use T5 | −.04 | −.13 | −.13 | −.12 | −.04 | .19 | .30 | .17 | .23 | .42 | .31 | −.24 | – | ||

| 14. Risky Sexual BehaviorT5 | −.16 | −.06 | −.11 | −.05 | −.07 | .12 | .15 | .06 | .12 | .22 | .18 | −.14 | .44 | – | |

| 15. Academic PerformanceT5 | .12 | .15 | .17 | .26 | .28 | −.32 | −.38 | −.11 | −.19 | −.42 | −.24 | .25 | −.28 | −.27 | – |

| Means | .68 | .05 | .05 | .05 | .04 | .00 | .02 | −.20 | .01 | 11.32 | 9.32 | 19.91 | 5.04 | 1.13 | 2.85 |

| Standard Deviations | .47 | .74 | .76 | .73 | .77 | 1.00 | .94 | 1.47 | .95 | 7.32 | 6.93 | 3.57 | 3.36 | 2.26 | .68 |

| Skewness | −.79 | −.21 | −.25 | −.35 | −.41 | .54 | .78 | .71 | 1.13 | 1.05 | 1.15 | −.64 | 1.14 | 3.51 | −.51 |

| Kurtosis | −1.38 | −.08 | −.50 | .23 | −.03 | .36 | .19 | 1.82 | 1.60 | 1.19 | 1.82 | −.30 | .37 | 14.86 | −.03 |

Note. Significant correlations at p ≤ .05 are in bold. M-C is mother-child.

In the present study, we combined the MP and MPCP groups, which is consistent with previous studies testing long-term effects of the NBP (i.e., Wolchik et al., 2007; Soper et al., in press; Zhou et al., 2008). We based this decision on previous comparisons of the two NBP intervention groups that showed fewer than chance differences in the effects of the MP alone as compared to the MPCP at post-test, short-term follow-up, and 6-year follow-up (Wolchik et. al., 2002; 2006; 2007; Wolchik, West et al., 2000).

In Wolchik et al.’s report (2002) of the long-term effects of the NBP on adolescent outcomes, attrition rates were examined across the 3 intervention conditions (i.e., MPCP, MP, and LC) to compare those who completed the 6-year follow-up with those who did not on baseline outcome measures. The interaction between attrition status and group membership was also evaluated. No significant attrition or group × attrition interaction effects were found. Given these results, missing data were accounted for using the Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimator, which provides more unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors than listwise deletion (Enders & Bandalos, 2001; Schafer & Graham, 2002).

Analytic Method

As shown in Figure 1, we hypothesized that the effects of the NBP on adolescent symptoms of internalizing disorders, symptoms of externalizing disorders, self-esteem, academic performance, substance use, and risky sexual behavior would be mediated by program-induced changes in parenting at T2 (i.e., mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline) and children’s mental health problems at T3+4 (i.e., internalizing problems and externalizing problems). To test the hypothesis, we assessed the fit of a multiple mediator model including program effects onT2 mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline, childhood externalizing problems and internalizing problems at T3+4, and adolescent adaptation outcomes at T5. To appropriately assess the intervention effects, we controlled for the baseline measures of mother-child relationship quality, effective discipline, internalizing problems and risk (which includes externalizing problems) as shown in Figure 1. In addition, because previous evaluations of the effects of NBP on adolescent outcomes have reported significant NBP × risk interactions, we included the effects of the NBP, risk and the NBP × risk interaction on all outcome variables. Given that previous research has shown significant effects of adolescent gender on internalizing problems and externalizing problems (see Crick & Zahn-Waxler, 2003 for a review), we also included the effects of adolescent gender and the NBP × gender interaction on all adolescent outcome variables. However, for ease of presentation, the effects of risk, gender, and NBP × risk and NBP × gender interactions on adolescent outcomes at T5 were not included in Figure 1. All possible correlations among the study variables measured at the same point in time, including the outcome variables, were also included in the model (e.g., mother-child relationship quality at T1 and effective discipline at T1).

The structural equation modeling approach to path analysis with observed variables was used to test the cascading pathways proposed in the hypothesized model (Schumacker & Lomax, 1996). Mplus 5.21 was used to estimate relations among the variables and assess model fit (Muthén & Muthén, 2009). The fit of the models was assessed with the chi-square statistic, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI). These particular fit indices are viewed as a good combination to assess the fit of models with small sample sizes (e.g., N < 250; Fan, Thompson, & Wang, 1999; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Yadama & Pandey, 1995). Although the chi-square fit statistic may be statistically significant, models were considered a good fit for the data if the SRMR was less than .08, the RMSEA was less than .06, and the CFI was greater than .95 simultaneously (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The significance of the standardized path coefficients was determined by comparing the t ratio to a critical t(.05) of 1.96. To test the significance of the indirect effects of the program on adolescent outcomes we used the bias-corrected bootstrap test, which produces bias-corrected confidence interval limits for three-path mediation models, and provides more power and smaller Type I error rates than other available tests (Taylor, MacKinnon, & Tein, 2008).

Hypothesized Model

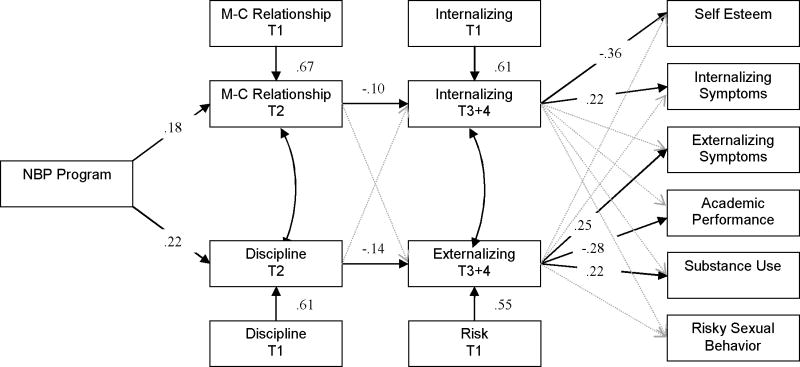

Structural equation modeling results indicated that the multiple mediation model fit the data well (χ2 (56) = 100.65, p = .001, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .05). As shown in Figure 2, the standardized path coefficients between the NBP (control group = 0; intervention group = 1) and mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline at T2 were positive and significant. The results also indicated that the path coefficients between mother-child relationship quality at T2 and child internalizing problems at T3+4, and between effective discipline at T2 and child externalizing problems at T3+4 were negative and significant. However, the paths between mother-child relationship quality at T2 and child externalizing problems at T3+4, and between effective discipline at T2 and child internalizing problems at T3+4 were not significant. The effects of the NBP on child internalizing problems and externalizing problems at T3+4 were also not significant in the context of the effects of mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline at T2. Child internalizing problems at T3+4 were related to decreases in self-esteem and increases in symptoms of internalizing disorders at T5. Child externalizing problems at T3+4 were related to increases in symptoms of externalizing disorders, greater substance use, and decreases in academic performance. The direct effects of the NBP on adolescent adaptation outcomes at T5 were not significant. Correlations between symptoms of externalizing disorders and symptoms of internalizing disorders, self esteem, substance use, and academic performance at T5 ranged in magnitude from .19 to 44, were statistically significant and in the expected direction. Correlations between risky sexual behavior and other outcomes at T5 were not significant. The correlations are not displayed in Figure 2 for ease of presentation. Tests of the multiple mediator model for each outcome separately produced similar results to those described above. The results of the full model are presented because they provide the most parsimonious test.

Figure 2.

Results for the Full Model of the Developmental Cascade Effects of the NBP on Adolescent Adaptation Outcomes

Note. Solid lines represent significant path coefficients at p ≤ .05; dashed lines represent nonsignificant path coefficients. The direct effects between NBP and all outcomes were included in the model, but only the significant paths are shown in the figure. The risk by program interaction, gender main effect, and gender by program interaction were also included in the model as predictors of mediators at T2 and T3+4 and outcomes at T5. The results of the interaction effects are described in the text. M-C is mother-child.

Indirect Effects

The confidence intervals for the indirect effects from the bootstrap method are presented in Table 2. The confidence intervals that did not include zero revealed that there were significant indirect effects of the NBP on adolescent (T5) symptoms of internalizing disorders and self-esteem through mother-child relationship quality at T2 and child internalizing problems at T3+4. In addition, there were significant indirect effects of the NBP on adolescent symptoms of externalizing disorders, substance use, and academic performance through effective discipline at T2 and child externalizing problems at T3+4. Taken together, the results indicated that there were five significant indirect pathways: 1) NBP was related to increases in mother-child relationship quality which in turn was related to decreases in child internalizing problems, which was related to decreases in adolescent symptoms of internalizing disorders; 2) NBP was related to increases in mother-child relationship quality which was related to decreases in child internalizing problems, which was related to increases in adolescent self-esteem; 3) NBP was related to increases in effective discipline which was related to decreases in child externalizing problems, which was related to decreases in adolescent symptoms of externalizing disorders; 4) NBP was related to increases in effective discipline which was related to decreases in child externalizing problems, which in turn was related to decreases in adolescent substance use; and 5) NBP was related to increases in effective discipline which was related to decreases in child externalizing problems, which was related to increases in adolescent academic performance.

Table 2.

Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects

| Program → M-C Relationship T2 → Internalizing T3+4 → | Program → Discipline T2 → Externalizing T3+4 → | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower 2.5% Confidence Limit | Upper 2.5% Confidence Limit | Lower 2.5% Confidence Limit | Upper 2.5% Confidence Limit | |

| Externalizing T5 | −.10 | .08 | −.41 | −.03 |

| Internalizing T5 | −.15 | −.01 | −.07 | .03 |

| Self-Esteem T5 | .01 | .20 | −.05 | .06 |

| Substance Use T5 | −.13 | .02 | −.17 | −.01 |

| Risky Sexual Behavior T5 | −1.62 | .65 | −1.31 | .45 |

| Academic Performance T5 | −.03 | .01 | .01 | .04 |

Note. Significant confidence intervals (i.e., not including 0) are in bold.

Risk Effects

Although not depicted in Figure 2 for ease of presentation, there were significant NBP × risk interactions on symptoms of internalizing disorders, symptoms of externalizing disorders, self-esteem, and substance use at T5. To probe the significant interactions, we conducted multiple group models for high and low risk subsamples and examined which pathways differed across groups, a procedure that has been used in a previous study examining mediation of long-term NBP effects (Zhou et al., 2008). To divide the sample into high- and low-risk groups, we used the cutoff developed by Zhou et al. (2008). Zhou and her colleagues (2008) took the lowest value of the Johnson-Neyman High Region of Significance (.09 above the mean on risk) across five adaptation outcomes (i.e., T5 externalizing problems, internalizing problems, mental health symptoms, competence, and substance use) to divide the sample into high- (44%) and low-risk groups (Johnson & Neyman, 1936; Ragosa, 1980; 1981). In the present study, the unconstrained multiple group model fit the data adequately (χ2 (100) = 153.35, p = .00, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .06). We employed a 4-step process of additive model constraints to test for significant differences between the path coefficients for the high and low risk groups. In the first step, we constrained the relations between the covariates and mediators to be equal for mother-child relationship quality, effective discipline, and risk at T1; mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline at T2; and child internalizing problems and externalizing problems at T3+4 (χ2 (106) = 159.41, p = .00, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .06). In step 2, we added constraints for the paths between the NBP and mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline at T2 (χ2 (108) = 161.37, p = .00, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .06). Next, we constrained the paths between mother-child relationship quality at T2 and child internalizing problems at T3+4, and effective discipline at T2 and child externalizing problems at T3+4 (χ2 (110) = 163.60, p = .00, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .06). The final model constrained all of the paths between the NBP, covariates at T1, mother-child relationship and effective discipline at T2, child internalizing problems and externalizing problems at T3+4, and all adolescent adaptation outcomes at T5 (χ2 (128) = 188.12, p = .00, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .07). The chi-square differences between the unconstrained multiple group model and the four constrained models were not significant, suggesting that the path coefficients between the high and low risk groups were not significantly different.

Gender Effects

As part of the full model, we also examined NBP × gender interaction effects. There were no significant NBP × gender interaction effects on mother-child relationship quality or effective discipline at T2, internalizing problems or externalizing problems at T3+4, or adolescent adaptation outcomes at T5. Thus, the model was not significantly different for girls and boys.

Discussion

Using a developmental cascade conceptual framework, the present study tested whether the NBP’s effects on adolescent adaptation outcomes could be explained by pathways in which intervention-induced improvements in parenting practices was related to decreases in mental health problems in childhood which were associated with more adaptive outcomes in adolescence. Results of this study provide support for the cascading pathways model in which functioning in one domain of behavior influences functioning in other domains later in development (Cicchetti & Sroufe, 2000; Cummings et al., 2000). The present study also furthers our understanding of the pathways through which the NBP had positive long-term effects on adolescent adaptation outcomes. Although the mediational role of NBP-induced changes in positive parenting on adolescent outcomes has been demonstrated previously (Zhou et al., 2008), the present study extends this work by beginning to “unpack” this linkage by identifying a cascade of effects from childhood adapation outcomes to adolescent adaptation outcomes. Further, the results provided support for different cascading pathways to different outcomes. Results indicated that program-induced improvements in mother-child relationship quality at post-test were related to decreases in child internalizing problems at short-term follow-up, which in turn were related to increases in self-esteem and decreases in symptoms of internalizing disorders at longer-term follow-up when participants were in mid-to-late adolescence. The program effect on effective discipline at post-test was related to decreases in externalizing problems in childhood, which was in turn related to reductions in symptoms of externalizing disorders, less substance use and increases in academic performance in adolescence.

Effects of parenting on internalizing problems and externalizing problems

Although over the past several decades researchers have provided consistent support for the critical role that positive parenting plays on youth outcomes (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Holmbeck, 1996), several researchers have argued that studies are needed to identify the specific processes underlying these relations and the direction of effects between dimensions of parenting and youth outcomes (e.g., Cowan & Cowan, 2002; Steinberg, 2000). Because so few studies have examined the longitudinal effects of specific dimensions of parenting on internalizing problems and externalizing problems simultaneously (McKee et al., 2008), our study provides relatively unique information about the independent effects of mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline on youth externalizing problems and internalizing problems.

The current findings provide evidence for specificity of relations between these two dimensions of parenting and these two dimensions of children’s mental health problems—high mother-child relationship quality predicted fewer internalizing problems but was not uniquely related to externalizing problems. Conversely, effective discipline predicted reduced externalizing problems but was not uniquely related to internalizing problems. These findings are consistent with the findings of most of the limited number of studies that have examined the effects of these parenting dimensions on internalizing problems and externalizing behaviors simultaneously (e.g., Buehler, Benson, & Gerard, 2006; Caron, Weiss, Harris, & Catron, 2006). It is important to note that not all studies have found support for this pattern (McKee et al., 2008). For example, although similar to our findings, Hipwell et al. (2008) found that low parental warmth but not discipline predicted increased internalizing problems, they also found that both low parental warmth and harsh punishment predicted increased externalizing problems. However, their measure of harsh discipline included items such as amount of yelling that overlap with the construct of acceptance/rejection used to measure mother-child relationship quality in our study. In our sample, Tein et al. (2004) found that both mother-child relationship quality and discipline predicted externalizing problems; however, Tein et al. (2004) did not include relationship quality and discipline in the same model. Thus, there were methodological differences between these studies and the current study which might account for the variability in the findings. Additional research is needed to understand the contexts in which these two dimensions of parenting lead to internalizing problems and externalizing problems.

Effects of childhood internalizing problems and externalizing problems on adolescent outcomes

Similar to findings of other researchers, we found stability in internalizing problems and externalizing problems from middle childhood to adolescence (e.g., Masten et al., 2005). However, unlike previous longitudinal studies, our findings did not support the proposition that internalizing problems would be associated with decreases in later externalizing problems (Burt et al., 2008; Pine et al., 2000), or that externalizing problems would be related to increases in later internalizing problems (Kiesner, 2002; Lahey et al., 2002). Methodological and developmental differences might explain these inconsistencies. For example, Lahey and colleagues (2002) used a clinically-referred sample and assessed conduct disorder diagnosis as a predictor of later internalizing problems, whereas we used a non-clinical sample and a continuous measure of externalizing problems. In studies showing that internalizing problems was related a lower likelihood of future externalizing problems, the effect was found from adolescence (age 14 to 17) to young adulthood (age 20 to 22) but was not significant when externalizing behavior was measured in adolescence, as in our study (Burt et al., 2008; Masten et al., 2005; Pine et al., 2000). Thus, as we follow our sample into young adulthood, we might find a significant relation between earlier internalizing problems and young adult externalizing problems.

We also observed differential effects of childhood internalizing problems and externalizing problems on other aspects of adolescent adjustment. Similar to our findings, previous studies found that internalizing problems predicted low self-esteem (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Roberts & Gamble, 2001). It is possible that the link between internalizing problems and self-esteem is due to negative cognitive styles, including negative self-schemata which are more common in individuals with higher levels of internalizing problems (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979). Previous studies have also found that externalizing problems predicted a broad range of adolescent outcomes not predicted by internalizing problems, including increased substance use, lower educational attainment, (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999) and decreased academic competence (Masten et al., 2005). Children who exhibit high levels of externalizing symptoms are more likely to associate with deviant peers in adolescence which often leads to delinquent behaviors, such as substance use and problems at school (Forgatch, Patterson, DeGarmo, & Beldavs, 2009). Thus, despite high concurrent associations between internalizing problems and externalizing problems, our results suggest that these dimensions of childhood adjustment problems appear to have different cascading effects to adolescent adaptation outcomes.

We did not find evidence for cascading effects that linked improvements in parenting and child mental health problems to adolescent risky sexual behavior. In their prospective mediational analyses, Zhou et al. (2008) found no support for NBP-induced changes in parenting at post-test to mediate reductions in number of sexual partners six years later. However, Soper et al. (in press) found that for those whose families were in the mother program condition, parental monitoring (i.e., knowledge of adolescents’ whereabouts, activities, and friends) assessed in adolescence mediated NBP effects on number of sexual partners for those at high risk for adjustment problems at baseline. High parental monitoring may be more critical to preventing adolescent sexual behavior than mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline. Most of the adolescents in the sample had sexual intercourse with only one partner or had not yet had sexual intercourse. Thus, the scores on risky sexual behavior (i.e., number of sex partners) were skewed, which may have limited the ability to detect significant effects. Perhaps we might have found significant indirect effects on risky sexual behavior if a wider range of sexual activities had been assessed, such as heavy petting, other foreplay activities, and use of birth control.

It is also important to note that we did not find support for significant differences in the model across gender nor level of baseline risk. The modest sample size and the complex, multiple mediator model may have limited the ability to detect significant gender or risk effects in the pathways from intervention-induced changes in parenting to mental health problems in childhood to adapative outcomes in adolescence.

Limitations and Future Research

There are several limitations that have implications for future research. First, all the participants agreed to participate in a randomized trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families in which multiple eligibility criteria were used. Participating mothers had higher incomes and reported more child behavior problems than refusers, thus, the sample may be biased in ways that limit generalizability. Also, the sample was almost exclusively middle-class and Caucasian. Research with larger, community-based samples that are diverse in ethnicity and socioeconomic background is an important future direction. Second, the youth in this study were children from divorced homes. Replication with children from the general population and other groups of at-risk youth is important to test the generalizability of the findings. Third, the time intervals between assessments varied widely because data collection was determined by the timing of the intervention and the interest in conducting short-term and longer-term follow-ups. Future studies should use developmental theory to guide the timing of assessments and employ equal amounts of time between waves. Fourth, we also did not assess bi-directional or reciprocal effects in the current study due to inconsistency of measurement across time. Further, given that previous cascade studies have found associations between earlier academic achievement and later internalizing problems (Masten et al., 2005), the current study is limited by not having a measure of academic achievement at T3 & 4. Future studies should include measures of all constructs assessed in developmentally appropriate way sat each time point to allow for testing a strict cascade analysis using a full cross-lag panel model (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Finally, the effects of parenting on developmental cascades should be studied across a broader range of developmental periods.

Conclusion

The current results add to the findings from previous studies with this data set that have shown that changing parenting in middle childhood has lasting effects by examining the developmental pathways through which these long-term effects may occur. Considerable evidence demonstrates that parenting interventions are among the most effective approaches to prevention (O’Conell, Boat & Warner, 2009), and the longitudinal evaluation of theory-driven preventive interventions will be important to identify the processes through which changing different dimensions of parenting at different developmental stages reduces problem outcomes and improves healthy development across time.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (1R01MH071707-01A2, 5P30MH068685, 5T32MH018387). We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of our research team and the families who so willingly gave their time to this project. We want to thank several members of the research team who made particularly important contributions to this project: Lillie Weiss, Susan Westover, Michele Porter, Toni Genalo, Brett Plummer, Qing Zhou, Art Martin, Julie Lustig, Kathleen Hipke, Rachel Haine, and Linda Harris.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychology; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Children Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(3):355–370. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Keith B. Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110(1):26–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes H, Olson DH. Parent-Adolescent Communication. In: Olson D, McCubbin H, Barnes H, Larsen A, Muxen M, Wilson M, editors. Family Inventories. St. Paul, MN: Family Social Sciences; 1982. pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Benson MJ, Buehler C, Gerard JM. Interparental hostility and early adolescent problem behavior: Spillover via maternal acceptance, harshness, inconsistency, and intrusiveness. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28(3):428–454. [Google Scholar]

- Burt K, Obradović J, Long J, Masten A. The interplay of social competence and psychopathology over 20 years: Testing transactional and cascade models. Child Development. 2008;79(2):359–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D, Stoolmiller M. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. Prediction to young-adult adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:59–84. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron A, Weiss B, Harris V, Catron T. Parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology: Specificity, task dependency, and interactive relations. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(1):34–45. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JJ, Halpern CT, Kaufman JS. Maternal depressive symptoms, father’s involvement, and the trajectories of child problem behaviors in a US national sample. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:697–703. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Sroufe LA. The past as prologue to the future: The times, they’ve been a-changin’. Development and Psychopathology. Special Issue: Reflecting on the Past and Planning for the Future of Developmental Psychopathology. 2000;12(3):255–264. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. Childhood risks for young adult symptoms of personality disorder: Method and substance. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1996;31:121–148. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3101_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP. Interventions as tests of family systems theories: Marital and family relationships in children’s development and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:731–759. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Zahn-Waxler C. The development of psychopathology in females and males: Current progress and future challenges. Development and Psychopathology. Special Issue: Conceptual, Methodological, and Statistical Issues in Developmental Psychopathology: A Special Issue in Honor of Paul E. Meehl. 2003;15(3):719–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(3):487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-McClure SR, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Millsap RE. Risk as a moderator of the effects of prevention programs for children from divorced families: A six-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(2):175–190. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019769.75578.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater J, MacCorquodale P. Premarital sexuality: Attitudes, relationships, behaviors. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2001;8:430–457. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Nonparametric estimates of standard error. Biometrika. 1981;68:589–599. [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, Thompson B, Wang L. Effects of sample size, estimation methods, and model specification on structural equation modeling fit indexes. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):56–83. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. An effective prevention program for single mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:711–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, Skinner ML. A mediational model for the effect of divorce on antisocial behavior in boys. In: Hetherington EM, Arasteh JD, editors. Impact of divorce, single parenting, and stepparenting on children. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1988. pp. 135–154. [Google Scholar]

- Guerney LF. Parenting: A skills training manual. 3. State College, PA: Institute of the Development of Emotional and Life Skills; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile of Children (Revision of the Perceived Competence Scale for Children) Denver, CO: University of Denver; 1985. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Bridges M, Insabella GM. What matters? what does not? five perspectives on the association between marital transitions and children’s adjustment. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):167–184. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel WG, Anderson ER, Deal JE, Stanley Hagan M, Hollier EA, Lindner MS. Coping with marital transitions: A family systems perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57(2–3) Serial No. 227. [Google Scholar]

- Hightower AD, Work WC, Cowen EL, Lotczewski BS, Spinell AP, Duare JC, Rohrbeck C. The Teacher-Child Rating Scale: A brief objective measure of elementary children’s school problem behaviors and competencies. School Psychology Review. 1986;15:393–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell A, Keenan K, Kasza K, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Bean T. Reciprocal influences between girls’ conduct problems and depression, and parental punishment and warmth: A six year prospective analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:663–677. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9206-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. A model of family relational transformations during the transition to adolescence: Parent-adolescent conflict and adaptation. In: Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen AC, editors. Transitions through adolescence: Interpersonal domains and context. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1996. pp. 167–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner AJ, Howell LW. Examining the relationship between adolescent sexual risk-taking and perceptions of monitoring, communication, and parenting styles. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:71–78. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS, Winslow E, Schonberg M, Gilliom M, Criss M. Neighborhood disadvantage, parent-child conflict, neighborhood peer relationships, and early antisocial behavior problem trajectories. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(3):293–309. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventative intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen ES, Boyce WT, Hartnett SA. The Family Routines Inventory: Development & Validation. Social Science Medicine. 1983;17:201–211. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, Neyman J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs. 1936;1:57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM. Monitoring the future: Questionnaire responses from the nation’s high school seniors. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Survey Research Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski J, Valle L, Filene J, Boyle C. A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:567–589. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JB, Emery RE. Children’s adjustment following divorce: Risk and resilience perspectives. Family Relations. 2003;52(4):352–362. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesner J. Depressive symptoms in early adolescence: Their relations with classroom problem behavior and peer status. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12(4):463–478. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatry. 1981;46:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey B, Loeber R, Burke J, Rathouz P, McBurnett K. Waxing and waning in concert: Dynamic comorbidity of conduct disorder with other disruptive and emotional problems over 7 years among clinic-referred boys. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(4):556–567. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Malone PS, Castellino DR, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Trajectories of internalizing, externalizing, and grades for children who have and have not experienced their parents’ divorce or separation. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(2):292–301. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, van den Steenhoven A. Family-based approaches to substance abuse prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2002;23(1):49–114. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Burt KB, Coatsworth JD. Competence and psychopathology in development. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, vol 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006. pp. 696–738. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt KB, Obradovic J, Riley JR, et al. Developmental cascades: Linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41(5):733–746. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Forehand R, Rakow A, Reeslund K, Roland E, Hardcastle E, et al. Parenting specificity: An examination of the relation between three parenting behaviors and child problem behaviors in the context of a history of caregiver depression. Behavior Modification. 2008;32(5):638–658. doi: 10.1177/0145445508316550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meichenbaum D. Stress innoculation training. New York: Pergamon Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus version 5.21©. Los Angeles CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. In: O’Connell M, Boat T, Warner K, editors. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. National Academies Press; Washington D. C: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Social Learning Center. LIFT Parent Interview. Oregon Social Learning Center; Eugene, OR: 1991. Unpublished Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Pine D, Cohen E, Cohen P, Brook J. Social phobia and the persistence of conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2000;41(5):657–665. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogosa DR. Comparing nonparallel regression lines. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:307–321. [Google Scholar]

- Rogosa DR. On the relationship between the Johnson-Neyman region of significance and statistical tests of parallel within-group regressions. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1981;41:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Renouf AG, Harter S. Low self-worth and anger as components of the depressive experience of young adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2(3):293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Paget KD. Factor analysis of the revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale for blacks, whites, males, and females with a national normative sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;49:352–359. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richard BO. What I Think and Feel: A Revised Measure of Children’s Manifest Anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J, Gamble S. Current mood-state and past depression as predictors of self-esteem and dysfunctional attitudes among adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:1023–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Roeser R, Eccles J, Sameroff A. School as a context of early adolescents’ academic and social-emotional development: A summary of research findings. The Elementary School Journal. 2000;100(5):443–471. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Sroufe LA. Developmental psychopathology: Concepts and challenges. Development and Psychopathology. Special Issue: Reflecting on the Past and Planning for the Future of Developmental Psychopathology. 2000;12(3):265–296. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ. Developmental systems and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. Special Issue: Reflecting on the Past and Planning for the Future of Developmental Psychopathology. 2000;12(3):297–312. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Miles J, Cookston J, Braver S. Effects of father and mother parenting on children’s mental health in high and low conflict divorces. Family Court Review. 2008;46:282–297. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Wolchik SW, Winslow EB, Schenck C. Prevention as the promotion of healthy parenting following divorce. In: Beach SRH, Wamboldt MZ, Kaslow NJ, Heyman RE, First MB, Underwood L, Reiss D, editors. Relational Processes and DSM-V: Neuroscience, Assessment, Prevention and Intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2006. pp. 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Saylor CF, Finch AJ, Spirito A, Bennett B. The Children’s Depression Inventory: A systematic evaluation of psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52(6):955–967. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36(2):413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Scott KG, Mason GA, Chapman DA. The use of epidemiological methodology as a means of influencing public policy. Child Development. 1999;70:1263–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper AC, Wolchik SA, Tein J-Y, Sandler IN. Mediation of a preventive intervention’s six-year effects program effects on health risk behaviors. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0019014. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark KD. Childhood depression: School-based intervention. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]