Abstract

To establish a successful infection, Yersinia pestis requires the delivery of cytotoxic Yops to host cells. Yops inhibit phagocytosis, block cytokine responses, and induce apoptosis of macrophages. The Y. pestis adhesin Ail facilitates Yop translocation and is required for full virulence in mice. To determine the contributions of other adhesins to Yop delivery, we deleted five known adhesins of Y. pestis. In addition to Ail, plasminogen activator (Pla) and pH 6 antigen (Psa) could mediate Yop translocation to host cells. The contribution of each adhesin to binding and Yop delivery was dependent upon the growth conditions. When cells were pregrown at 28°C and pH 7, the order of importance for adhesins in cell binding and cytotoxicity was Ail > Pla > Psa. Y. pestis grown at 37°C and pH 7 had equal contributions from Ail and Pla but an undetectable role for Psa. At 37°C and pH 6, both Ail and Psa contributed to binding and Yop delivery, while Pla contributed minimally. Pla-mediated Yop translocation was independent of protease activity. Of the three single mutants, the Δail mutant was the most defective in mouse virulence. The expression level of ail was also the highest of the three adhesins in infected mouse tissues. Compared to an ail mutant, additional deletion of psaA (encoding Psa) led to a 130,000-fold increase in the 50% lethal dose for mice relative to that of the KIM5 parental strain. Our results indicate that in addition to Ail, Pla and Psa can serve as environmentally specific adhesins to facilitate Yop secretion, a critical virulence function of Y. pestis.

The causative agent of plague is the Gram-negative bacterium Yersinia pestis (54, 77). Plague is one of the most deadly infectious diseases and has decimated civilizations repeatedly throughout history (10, 54). Plague still remains a public health concern, and due to the increasing number of cases worldwide, plague is classified as a reemerging infectious disease (68). Identification of therapies or effective vaccines would provide protection against plague as a potential bioterrorism threat.

There are three clinical forms of plague in humans: bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic (54). Bubonic plague is the most common form and usually occurs following a fleabite. In bubonic plague, the organism initially spreads to the regional lymph nodes, where it replicates primarily extracellularly, and then eventually enters the bloodstream. If untreated, bubonic plague is fatal in 40 to 60% of cases (54). Pneumonic plague is the least common form, but it progresses rapidly and is the most fatal form of the disease. Pneumonic plague may occur as a complication of bubonic or septicemic plague (secondary pneumonic plague) or by inhalation of infectious droplets spread by the cough or sneeze of a person with pneumonic plague (primary pneumonic plague). If treatment is not initiated within the first 24 h after symptoms appear, it is likely to be fatal within 48 h (18, 49). Septicemic plague can occur if Y. pestis gains direct access to the bloodstream via open wounds or fleabites (primary septicemic plague) (64) or as a result of spread from the lymphatic system to the bloodstream during advanced stages of bubonic plague (54). Y. pestis can also spread to the bloodstream and blood-filtering organs during late stages of pneumonic plague (39).

In order for Y. pestis to cause disease, it must harbor the 70-kb pCD1 virulence plasmid, which encodes the Ysc type III secretion system (T3SS) and the Yop effector proteins (13, 69, 70). Yops inhibit phagocytosis by disrupting the actin cytoskeleton, diminish proinflammatory cytokine responses, and induce apoptosis of macrophages (13, 30, 50, 51, 54, 60, 62). In order for Yops to be delivered efficiently to host cells, adhesins must provide a docking function to facilitate T3S (8, 22, 59).

Two adhesins shown to be important for Yop delivery in the related Yersinia species Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis are YadA and invasin (Inv) (8, 47, 59). Y. pestis lacks both of these adhesins due to inactivation of inv by an IS1541 element and of yadA by a frameshift mutation (17, 52, 61, 65). Thus, we focused our studies on the Y. pestis adhesins described below.

We recently identified Ail, an adhesin of Y. pestis that binds host cell fibronectin (73) and plays an important role in delivery of Yops to both phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells in vitro (22). In addition to having a defect in Yop delivery in vitro, a Y. pestis KIM5 Δail mutant has a >3,000-fold increased 50% lethal dose (LD50) for mice in a septicemic plague model (22). However, the virulence defect of a KIM5 Δail mutant is not as severe as that of a KIM5 strain lacking the virulence plasmid (>106-fold increase in LD50) (22, 69). Thus, we set out to determine if there were other Y. pestis adhesins capable of facilitating Yop delivery.

Four other adhesins of Y. pestis have been described. Plasminogen activator (Pla) is an adhesin and a protease. It can mediate binding to extracellular matrix proteins (32, 37, 43) and direct invasion of tissue culture cells (14, 36). Pla may also interact with the host cell receptor DEC-205 on macrophages and dendritic cells (80). Pla is known to be required for dissemination of a bubonic plague infection from the site of inoculation, presumably due to cleavage of fibrin clots by plasmin after Pla-mediated activation of plasminogen (27, 66). Its protease activity is also required for the development of fulminant pneumonic plague (39).

pH 6 antigen (Psa) is a multifunctional surface structure that is induced at 37°C under low-pH conditions (4, 57, 75) and is controlled by the regulatory protein RovA (11). Psa can bind to β1-linked galactosyl residues in glycosphingolipids (53) and to phosphatidylcholine (26) on the surfaces of host cells. Due to its ability to bind surface receptors, Psa functions as an efficient adhesin (5, 24, 26, 41, 76). Psa-mediated adhesion also prevents phagocytosis (29). Finally, Psa can bind the Fc portion of human IgG (79) and interact with plasma low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) (44).

The two remaining Y. pestis adhesins are the putative autotransporter YapC (23) and the pilus associated with the chaperone usher locus y0561 to y0563 (24). Neither locus is well expressed under laboratory conditions (23, 24; S. Felek and E. S. Krukonis, unpublished data), but when expressed in Escherichia coli, they can confer an increase in E. coli adhesion to several cultured cell lines (23, 24).

Here we demonstrate that Ail, Pla, and Psa can mediate Yop delivery in vitro when expressed in a KIM5 mutant lacking all five adhesins (KIM5 Δ5), whereas overexpression of YapC or y0561 to y0563 does not allow for Yop delivery from the KIM5 Δ5 strain. Furthermore, we observed cumulative defects in virulence when each of three genes, ail, pla, and psaA, was deleted and tested in a mouse model. Thus, we have shown that all three adhesins can contribute to Yop delivery in vitro and to virulence in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Y. pestis KIM5-3001 is a streptomycin-resistant, pigmentation-negative strain lacking a large, 102-kb locus including the 36-kb high-pathogenicity island and a number of other loci, including the siderophore yersiniabactin gene (ybt) (3, 25). Thus, KIM5-3001 derivatives are unable to acquire iron efficiently from peripheral tissues, resulting in attenuation. For simplicity, KIM5-3001 is referred to as KIM5 throughout this report. Y. pestis KIM5 was grown in heart infusion broth (HIB) or on heart infusion agar (HIA) containing 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Escherichia coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar or in LB broth. Chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml) and 100 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) were added for complementation studies. Characteristics of the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or features | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Y. pestis strains | ||

| KIM5 | KIM5-3001; Pgm− Strr pCD1+ pCP1+ pMT1+ | 23 |

| KIM5 Δail | Δail | 22 |

| KIM5 Δail | Δail; derived from KIM5, not KIM5-3001 | 2 |

| KIM5 Δpla | Δpla | This study |

| KIM5 ΔpsaA | ΔpsaA | This study |

| KIM5 Δail Δpla | Δail Δpla | This study |

| KIM5 Δail ΔpsaA | Δail ΔpsaA | This study |

| KIM5 Δail Δpla ΔpsaA | Δail Δpla ΔpsaA | This study |

| KIM5 Δail Δpla ΔpsaA ΔyapC Δy0561 | Δail Δpla ΔpsaA ΔyapC Δy0561 | This study |

| KIM5 pCD1− (also known as KIM6) | pCD1− | 23 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMMB207 | Cmr | 48 |

| pMMB207-ail | Cmr | 22 |

| pMMB207-pla | Cmr | This study |

| pMMB207-psaABC | Cmr | 24 |

| pMMB207-yapC | Cmr | 23 |

| pMMB207-y0561-y0563 | Cmr | 24 |

| pMMB207-plaS99A | Expresses proteolytically inactive form of Pla; Cmr | This study |

| pMMB207-plaH101V | Expresses proteolytically inactive form of Pla; Cmr | This study |

| pMMB207-plaD206A | Expresses proteolytically inactive form of Pla; Cmr | This study |

| pKD46 | Ampr; λ-RED recombinase expression plasmid | 15 |

| pKD4 | Kmr; template plasmid | 15 |

| pCP20 | Flp recombinase expression plasmid; Ampr Cmr | 15 |

Deletion and cloning of Y. pestis genes.

Genes in Y. pestis KIM5 were deleted by using the λ-RED system (15, 78). Primers used for deletion of ail were reported previously (22). Primers for deletion of pla, psaA, and y0561 are provided in Table 2. For deletion of pla, which is carried on the plasmid pPCP1, after transformation with kanamycin resistance-encoding Δpla PCR products, the KIM5 derivatives were passaged for 5 days with 100 μg/ml kanamycin to replace all pla-carrying plasmids with the Δpla allele. Complete replacement was confirmed by PCR and plasminogen activator assays. Retention of the pla-carrying plasmid pPCP1 in all strains was confirmed by plasmid isolation and characterization, while retention of the pCD1 and pMT1 plasmids was confirmed by PCR amplification of yopB and ymt, respectively. The genes encoding individual adhesins were PCR amplified from Y. pestis KIM5 (using primers listed in Table 2) and cloned into the pMMB207 plasmid by use of appropriate restriction enzymes. Clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing and then introduced into the mutant strains for complementation experiments.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for deletion and cloning of various Y. pestis adhesinsa

| Primer | Purpose | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| placf1 | Cloning of pla | GCGCGAATTCGCAGAGAGATTAAGGGTGTC |

| placr1 | Cloning of pla | GCGCCTGCAGTTTTTCAGAAGCGATATTGCAG |

| pladf | Deletion of pla | CAGATACAAATAATATGTTTTCGTTCATGCAGAGAGATTAAGGGTGTCT TGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| pladr | Deletion of pla | CATCCTCCCCGCTAGGGGAGGATGAAAAGAGAGATATGATCTGTATTTTCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAGT |

| plaf1 | Deletion confirmation | GTTGTCGGATCTGAAAAATTCG |

| plar1 | Deletion confirmation | GGATGTTGAGCTTCCTACAG |

| 0301cf | Cloning of y0561 to y0563 | GCGCGAATTCCATTATAATATATCAGGAGTTTTAA |

| 0301cr | Cloning of y0561 to y0563 | GCGCGGATCCCGCCCCACATCAAAATAACC |

| 0301df | Deletion | GACTCAGCAATAAACATTATAATATATCAGGAGTTTTAATGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| 0301dr | Deletion | CAATCAAAAATAGCCTTGGCCATACCCGCTTGTTACGCGCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAGT |

| 0301f2 | Deletion confirmation | GCAGTCGTAGGTAAATATATTAG |

| 0301r1 | Deletion confirmation | AAAATCGAATATCACCCTAGAG |

| psaAcf6 | Cloning of psaABC | GCGCGTCGACTATCACCACTAGCATATTCTAC |

| psaAcr6 | Cloning of psaABC | GCGCAAGCTTAACCTAACGGGAATTGTGTC |

| psaAf5′ | Deletion of psaA | ATATTCTACGCTATGTCGTAATAGCAATTATTACATTTATGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| psaAf5′ | Deletion of psaA | CATGACAGCAAGCCATCATGTTCTATGATTACTCGTTATCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAGT |

| psaAf2 | Deletion confirmation | ACACAACCACAACAGGAACG |

| psaAr2 | Deletion confirmation | ATAAGCATAAGGTAAAGACACC |

Cell adhesion assays.

Cell adhesion assays were performed as described previously, except that bacteria were not spun down onto the cell monolayer by centrifugation (22). Adhesion was enumerated by counting cell-associated CFU. HEp-2 cells were cultured until they reached 100% confluence in 24-well plastic tissue culture plates (Falcon, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) containing minimal Eagle's medium (MEM) with Earle's salts and l-glutamine (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% nonessential amino acids, and 1% sodium pyruvate. THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FCS. THP-1 cells were activated with 10 pg/ml of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 3 days to stimulate attachment to 24-well plates. By the end of day 3, the cells had grown to about 60% confluence. Y. pestis KIM5 derivatives were cultured overnight at 28°C and pH 7, 37°C and pH 7, or 37°C and pH 6, diluted to an optical density at 620 nm (OD620) of 0.15 in HIB, and cultured for 3 to 4 more hours under the same conditions. Tissue culture cells were washed twice with 1 ml of serum-free Dulbecco's minimal Eagle's medium (DMEM) (HEp-2 cells) or RPMI 1640 (THP-1 cells) and then infected with the bacterial strains at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 30 bacteria per cell. For THP-1 cells, the cells were pretreated with 5 μg/ml cytochalasin D for 45 min prior to infection to inhibit phagocytosis. Plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were then washed, and cell-associated bacteria were liberated by the addition of sterile H2O containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min and enumerated as CFU. In parallel wells, the entire population of bacteria was harvested and enumerated by CFU analysis to determine the total number of bacteria/well. Percent adhesion was calculated by dividing the bound CFU by the total number of bacteria in the well at the end of a 2-h incubation and multiplying the value by 100. Data presented are from two experiments performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test (n = 6).

Determination of adhesion and cytotoxicity by Giemsa staining.

HEp-2 cells were cultured in 24-well tissue culture plates until reaching 50% confluence. Y. pestis and derivative strains were cultured as described above for cell adhesion assays. For complementation strains, 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 100 μM IPTG were added. The strains were centrifuged and resuspended in MEM. HEp-2 cells were infected with bacteria at an MOI of about 30 per cell after being washed twice with MEM (no serum). Plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 2 h, and wells were washed twice with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were fixed with 100% methanol and stained with 0.076% Giemsa stain for 20 min. The stain was washed away four times with double-distilled H2O. Pictures were taken under an inverted light microscope at a magnification of ×20.

Cytotoxicity assay.

HEp-2 cells were cultured until they reached >50% confluence in 24-well tissue culture plates. Strains were cultured and diluted as described above. Cell culture plates were washed two times with 1 ml of serum-free medium, and 400 μl of serum-free medium with 125 μM IPTG was added to each well. IPTG was added for induction of plasmid-encoded adhesins. One hundred microliters of bacteria was then added to achieve an MOI of about 30 bacteria per cell and an IPTG concentration of 100 μM. Plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. As a marker of Yop delivery, rounding was observed and pictures were taken under a phase-contrast microscope at hours 0, 2, 4, and 8. Five fields were counted for each mutant strain infection to determine the % cytotoxicity at the various time points. Statistical significance was assessed using chi-square analysis after counting ∼500 cells/infectious treatment.

Yop delivery assay.

HEp-2 and THP-1 cells were prepared in 6-well culture plates as described above. KIM5 derivatives carrying a YopE129-ELK-containing plasmid (16) were cultured overnight in HIB, diluted, and incubated for 3 to 4 h more under the conditions described above (with the modification that 100 μg/ml ampicillin was added to the assay mixtures to select for the YopE-ELK-encoding plasmid). Strains were added to cells at an MOI of 60 in the presence of 100 μM IPTG (to induce expression of adhesins from plasmid pMMB207). The bacteria were allowed to interact with and translocate Yops for 2 to 8 h. Tissue culture medium was collected, and wells were then lysed directly in 100 μl Laemmli sample buffer. Tissue culture medium was centrifuged to collect unbound bacteria, and the pellet was combined with lysates. Lysates were boiled for 5 min. Extracts were used for Western blot analysis and probed with anti-ELK or anti-phospho-ELK antibodies (Cell Signaling). If YopE-ELK is translocated into eukaryotic cells, ELK is phosphorylated by the eukaryotic kinase mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase or by stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK) (12, 45), and phospho-ELK can be detected by anti-phospho-ELK antibodies (16). Anti-ELK antibody reacts with all YopE-ELK species found in bacteria and host cells. KIM5 ΔyopB served as a negative control for Yop delivery. YopB is part of the translocation apparatus and is required for translocation of Yops.

Some technical issues affected the analysis of this assay. In the presence of Pla, some phospho-YopE-ELK is cleaved prior to or during delivery to host cells. Thus, in assays probing with anti-phospho-ELK, some of the material that should run at the position of phospho-YopE-ELK migrates faster (see arrows in Fig. 4). The position where that molecule runs is the same as that for Ail, and the anti-phospho-ELK antibody cross-reacts with Ail (Felek and Krukonis, unpublished observations). This prevents one from using the anti-phospho-ELK antibody to accurately detect all YopE-ELK delivered to host cells. Fortunately, the same Pla-cleaved product of phospho-YopE-ELK is detectable with the anti-ELK antibody. While this antibody detects both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated YopE-ELK, there is a short YopE-ELK molecule that appears at later times during HEp-2 cell infections (see Fig. 4A) and at all time points in THP-1 cell infections (see Fig. 4B) that corresponds to cleaved phospho-YopE-ELK. In THP-1 cells at 2 h, one can see strong Yop delivery by KIM5 but markedly reduced delivery in the Δail mutant. In the Δpla mutant, one also observes strong delivery, as analyzed with anti-phospho-ELK antibody, but the anti-ELK antibody reveals that in the Δpla mutant, YopE-ELK is no longer cleaved during transfer to host cells (as expected, since cleavage is mediated by Pla). Cleavage of Yops by Pla has been reported previously (46, 63, 67). One also sees restoration of phospho-YopE-ELK cleavage at all time points in THP-1 cells for the Δail Δpla ΔpsaA triple mutant when Pla is reintroduced on a plasmid (see Fig. 4B). Thus, although some aspects of phospho-YopE-ELK detection are obscured in this assay, the anti-ELK antibody allows us to assess the remaining cleaved products of YopE-ELK that are delivered to host cells.

Western blot analysis.

Samples from 8-h time course experiments that were analyzed for YopE-ELK phosphorylation were examined by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). After samples were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, Ail was detected using an anti-Ail antibody (a kind gift from Ralph Isberg [76]). Pla was detected using an anti-Pla antibody (a kind gift from Timo Korhonen), and PsaA was detected using an anti-PsaA antibody (a kind gift from Susan Straley). Primary antibodies were used at a 1:500 (anti-Ail), 1:500 (anti-Pla) or 1:5,000 (anti-Psa) dilution. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody was used at a 1:10,000 dilution (Zymed). Blots were exposed using a Super Signal West Pico kit (Thermo Scientific).

Mouse experiments.

Six- to 8-week-old female Swiss Webster mice were obtained from Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, IN. Strains were cultured overnight in HIB at 28°C, pelleted, and resuspended in sterile PBS to obtain the desired CFU. To assess inoculum doses for each group, samples were plated on HIA. Mice were inoculated intravenously (i.v.), via the tail vein, with 5- to 10-fold increasing doses of strains. All mutants were tested at 10 animals/dose, and some mutants were tested in additional experiments with 4 to 8 animals/dose. Mice were checked daily for survival for 16 days. LD50s were determined by probit analysis, using the program PASWStatistics 17.0, and/or by the method of Reed and Muench (58).

qRT-PCR.

Transcription levels of ail, pla, psaA, yapC, y0561, caf1, rpoB, and the 16S rRNA gene were determined by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR). For in vivo samples, mice were infected i.v. with 960 CFU of Y. pestis KIM5 and then sacrificed at day 4, and liver and lung samples were obtained. One portion of each sample was homogenized and plated on HIA to determine the colonization level by CFU enumeration. The other portion of each sample was put in RNA Later (Ambion, Austin, TX). For in vitro samples, strains were cultured overnight at 28°C and pH 7, 37°C and pH 7, or 37°C and pH 6, diluted to an OD620 of 0.15 in HIB, and cultured for 3.5 more hours under the same growth conditions. RNAs were purified from mouse tissues and from in vitro samples by use of Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), treated with DNase I (New England Biolabs), and reverse transcribed. qRT-PCR was performed for 50 cycles, using an iCycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) thermal cycler. Primers for qRT-PCR were all designed to have a melting temperature of 50 to 53°C and a nearly uniform length of 20 to 23 nucleotides (nt) (see below). All qRT-PCR products were designed to be 112 to 147 nt in length. Samples amplified without RT (−RT) served as a control for DNA contamination and background PCR products from eukaryotic tissue (liver and lung samples). Expression levels were normalized to the levels of transcription found for the housekeeping gene rpoB (encoding the RNA polymerase β subunit). In a pilot experiment using 10-fold serial dilutions of KIM5 genomic DNA, we observed that, on average, every 3.25-cycle increase in qRT-PCR represented a 10-fold decrease in template DNA. Thus, in calculating expression levels for each gene, an increase of 3.25 cycles was calculated as a 10-fold change in expression level. For each gene, the background signal from samples not treated with RT (−RT) was subtracted from the +RT signal to eliminate the contribution of DNA contamination. Assays were performed twice in triplicate, and the standard deviation was determined. Primer pairs were as follows: for rpoB, 5′-AGAAGCAGCATTCCGTTCTG-3′ and 5′-GCTGAATAAGTCACACCACG-3′ (135-nt product); for ail, 5′-GTCAAGGAAGATGGGTACAAG-3′ and 5′-TCAACAGATTCCTCGAACCC-3′ (134-nt product); for pla, 5′-GACAGCTTTACAGTTGCAGCC-3′ and 5′-ATATCACCTTTCAGGATAGCGAC-3′ (136-nt product); for psaA, 5′-ATCGCTGCTTGTGGTATGGC-3′ and 5′-TTACCCGCAAAAATCTCTCCTG-3′ (134-nt product); for yapC, 5′-GTTCAGGTATTGGCTTTTACAC-3′ and 5′-CCAGCCCATTATTAATGACTCC-3′ (112-nt product) (23); for y0561, 5′-GGCACTATGACAGTACCAAG-3′ and 5′-GTCACAGTTTACCGTCCAAG-3′ (147-nt product); for 16S rRNA gene, 5′-TTGTAAAGCACTTTCAGCGAGG-3′ and 5′-AATTCCGATTAACGCTTGCACC-3′ (138-nt product); and for caf1, 5′-TGCAACGGCAACTCTTGTTG-3′ and 5′-TATAGCCGCCAAGAGTAAGC-3′ (131-nt product).

Mutations in plasminogen activator.

Nonproteolytic mutants of Pla were designed according to the methods described in previous studies (35). PCR mutagenesis was performed using the enzyme Pfu (Stratagene) and primer pairs encoding the Pla-S99A, Pla-H101V, and Pla-D206A mutations. The primers used were complementary to one another and were as follows: pla-S99A top, 5′-GAAAATCAATCTGAGTGGACAGATCACGCATCTCATCCTGCTACAAATGTTAATC-3′; pla-S99A bottom, 5′-GATTAACATTTGTAGCAGGATGAGATGCGTGATCTGTCCACTCAGATTGATTTTC-3′; pla-H101V top, 5′-CAATCTGAGTGGACAGATCACTCATCTGTTCCTGCTACAAATGTTAATCATGCC-3′; pla-H101V bottom, 5′-GGCATGATTAACATTTGTAGCAGGAACAGATGAGTGATCTGTCCACTCAGATTG-3′; pla-D206A top, 5′-GACTGGGTTCGGGCACATGATAATGCAGAGCACTATATGAGAGATCTTA C-3′; and pla-D206A bottom, 5′-GTAAGATCTCTCATATAGTGCTCTGCATTATCATGTGCCCGAACCCAGTC-3′. Following PCR amplification using a pSK-pla Bluescript-derived plasmid as a template, the PCRs were digested with DpnI to cut the template DNA and were transformed into E. coli DH5α. Potential mutant clones were sequenced to confirm that only the target site was mutated, and an EcoRI/PstI fragment containing the entire pla open reading frame and ribosome-binding site was liberated, purified, and ligated into the IPTG-inducible plasmid pMMB207 (48).

Plasminogen activator assay.

To determine whether Pla mutants had lost proteolytic activity, we performed a plasminogen activator assay as described previously (35). Briefly, strains were cultured overnight at 28°C, diluted to an OD620 of 0.1 in HIB, and cultured for 4.5 more hours at 28°C with shaking. Strains were diluted to a final concentration of 8 × 107 CFU in 100 μl PBS. Four micrograms of human Glu-plasminogen (Hematologic Technologies, Essex Junction, VT) and a 50 μM concentration of the chromogenic substrate D-AFK-ANSNHiC4H9-2HBr (SN-5; Hematologic Technologies) in 100 μl PBS were added. Plates were incubated for 16 h at 37°C, and absorbances were measured at 360-nm excitation and 465-nm emission wavelengths by a fluorescence microplate reader (Varioskan Flash; Thermo Scientific).

RESULTS

We previously demonstrated that when Y. pestis is grown at 28°C and pH 7, Ail is a critical adhesin that contributes to binding and Yop delivery in vitro and to virulence in vivo (22). In this study, we sought to characterize the roles of five Y. pestis adhesins (Ail, Pla, Psa, YapC, and y0561) in Yop delivery under various growth conditions.

Expression of Ail, Pla, or Psa restores strong binding and cytotoxicity to HEp-2 cells.

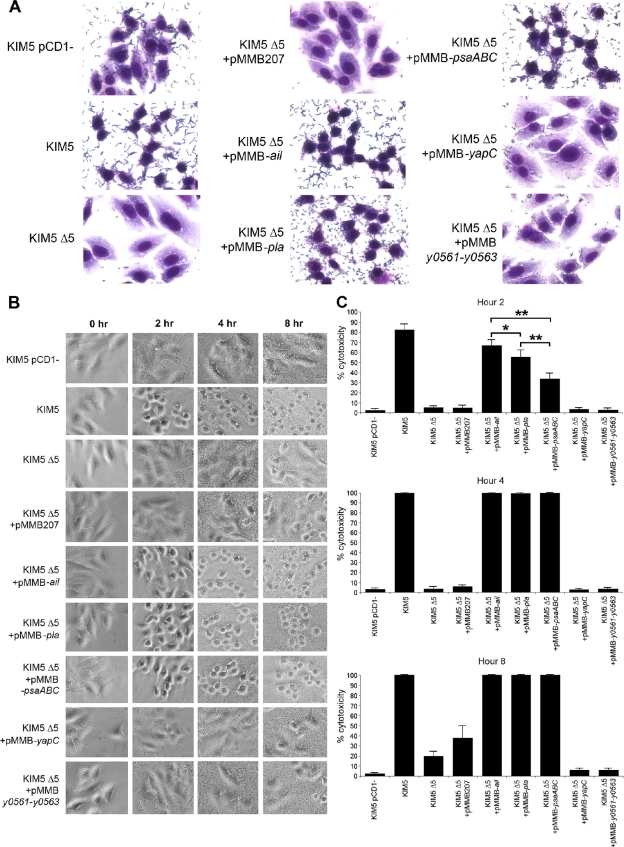

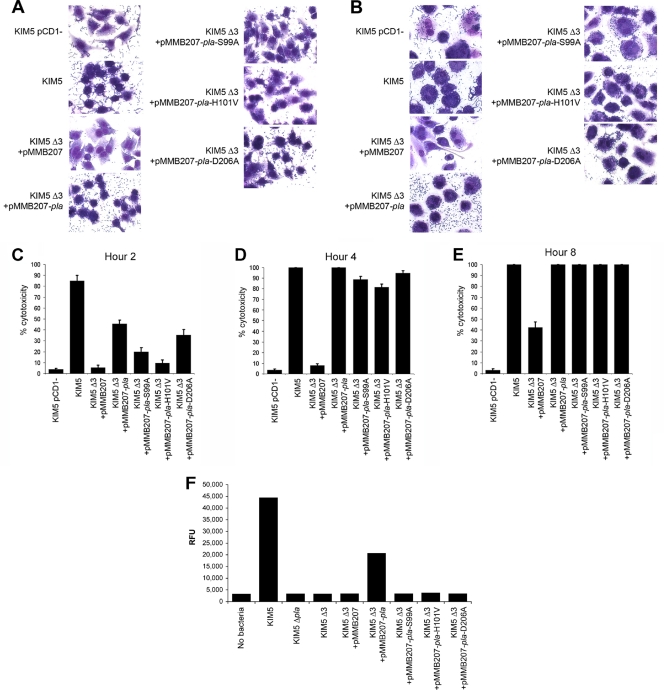

To determine which adhesins play a role in Yop delivery, the five known adhesins of Y. pestis were first deleted from KIM5 (strain KIM5 Δ5). KIM5 is an attenuated strain that is unable to acquire iron following inoculation via peripheral routes of infection (25) but is fully virulent by the intravenous route of infection. Each individual adhesin was then expressed from a plasmid in the KIM5 Δ5 strain and tested for cytotoxicity on HEp-2 cells, using a Giemsa cell-staining protocol. When all five adhesins were deleted, Y. pestis Yop-mediated cytotoxicity to HEp-2 cells was severely diminished (as represented by an intact cytoplasm and spread cells), as was cell-binding capacity (Fig. 1A; bacterial binding is visualized as small Giemsa-stained rods). Expression of Ail, Pla, or Psa from plasmid pMMB207 (48) in this strain restored cytotoxicity and adhesion to HEp-2 cells to levels seen with the parental KIM5 strain (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, expression of two other adhesins, YapC (23) and y0561 (24), slightly increased adhesion to HEp-2 cells but did not cause cytotoxicity. As a negative control, we used a KIM5 strain lacking the pCD1 Yop-encoding virulence plasmid, i.e., Y. pestis KIM5 pCD1−. This strain bound to HEp-2 cells like the parental strain KIM5, but it did not elicit cytotoxicity (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Adhesion and cytotoxicity of the KIM5 Δ5 mutant complemented with various Y. pestis adhesins. (A) Giemsa-stained infection assays at 2 h postinoculation. Cell rounding and bound bacteria are visible. Pictures are representative of overall effects. (B) Cell rounding/cytotoxicity assay of KIM5 derivatives, visualized by phase-contrast microscopy. HEp-2 cells were infected, and cell rounding was observed at hours 2, 4, and 8. (C) Quantification of cell rounding data from panel B at various time points (5 fields/strain; n, ∼500 cells). As a negative control, a KIM5 strain cured of the Yop-encoding virulence plasmid, pCD1, was included. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.000001. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Assessment of defects in cytotoxicity over a longer time course revealed that the Y. pestis KIM5 Δ5 strain caused no cell rounding after 4 h of infection and mediated very little rounding even after 8 h (Fig. 1B). HEp-2 cell cytotoxicity was monitored for 8 h postinfection by phase-contrast microscopy, using cell rounding as an indicator of Yop delivery (Fig. 1B). Plasmid-mediated Ail, Pla, or Psa expression restored cytotoxicity to levels similar to those for KIM5-mediated cell rounding (Fig. 1B). Expression of YapC or y0561 to y0563 did not increase cell rounding, even after 8 h (Fig. 1B). By 4 h, even nonadherent strains grew to high levels in the tissue culture medium (Fig. 1B, KIM5 Δ5), as nonadherent bacteria in the inoculum were not washed off in this assay. Quantification of the ability of each adhesin to restore Yop delivery and cytotoxicity indicated that Ail was the most efficient at restoring Yop delivery, followed by Pla and Psa (Fig. 1C, 2-h time point). However, at least some of the delay in Psa-mediated cytotoxicity was likely due to a kinetic lag in expression, which we address in a later section (see Fig. 4C to E).

FIG. 2.

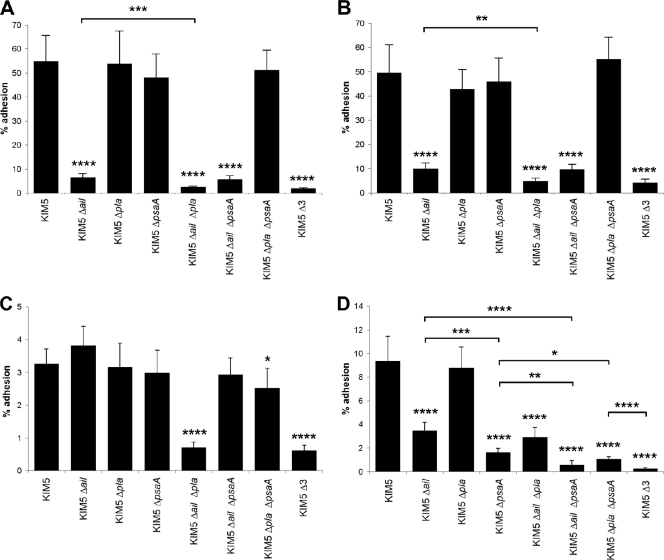

Cell adhesion of various KIM5 mutant derivatives. Binding to HEp-2 cells (A) or THP-1 cells (B) by various KIM5 mutants grown at 28°C and pH 7 was assessed using a CFU assay. THP-1 cells were pretreated with 5 μg/ml of cytochalasin D to prevent phagocytosis during the cell adhesion assays. Binding to HEp-2 cells was also assessed after growing strains at 37°C and pH 7 (C) or at 37°C and pH 6 (D). Δ3 denotes KIM5 Δail Δpla ΔpsaA. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.0005; ****, P < 0.00005. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Cumulative effects of Δail, Δpla, and ΔpsaA mutations in KIM5 on cell binding under various growth conditions.

Since artificially induced expression of Ail, Pla, and Psa could facilitate Yop translocation to HEp-2 cells (Fig. 1), we analyzed these three adhesins further. To determine the roles of individual adhesins in Yop delivery and virulence, we constructed individual, double, and triple deletion mutants. The strongest cell-binding defect for a single mutant, grown at 28°C and pH 7, was observed when ail was deleted in Y. pestis KIM5 (Fig. 2A and B) (22). Additional deletion of pla further decreased the cell-binding capacity of the Δail mutant for both human-derived epithelial cells (HEp-2) (Fig. 2A) and a human-derived monocyte-like cell line (THP-1) (Fig. 2B), although the Δpla mutation had no effect on adhesion to either cell line by itself. Thus, in Y. pestis grown at 28°C and pH 7, Ail is the predominant adhesin and Pla plays a less prominent role (Ail > Pla > Psa). In these experiments, Psa played no role in adhesion, as would be expected since the medium was not acidified to induce Psa expression.

Since during the course of infection Y. pestis adapts to the 37°C environment of the host by modifying many cellular properties, including expression of adhesins and capsule (55), we tested the roles of Ail, Pla, and Psa in cell adhesion upon growth at 37°C and pH 7 and at 37°C and pH 6 (with the latter mimicking acidified tissues and phagolysosomal compartments [41]). When KIM5 and various mutant derivatives were pregrown at 37°C and pH 7, no single mutant had a defect in HEp-2 cell adhesion (Fig. 2C). However, combining the Δail and Δpla mutations gave rise to a 5-fold decrease in adhesion (Fig. 2C). Deletion of psaA had no effect on adhesion under these conditions, as predicted (Ail = Pla > Psa). When pregrown at 37°C and pH 6, KIM5 derivatives demonstrated that Ail and Psa play important roles in cell adhesion, while Pla plays a negligible role under these conditions (Fig. 2D) (Psa > Ail > Pla).

Cumulative effects of Δail, Δpla, and ΔpsaA mutations on Yop-mediated cytotoxicity under various growth conditions.

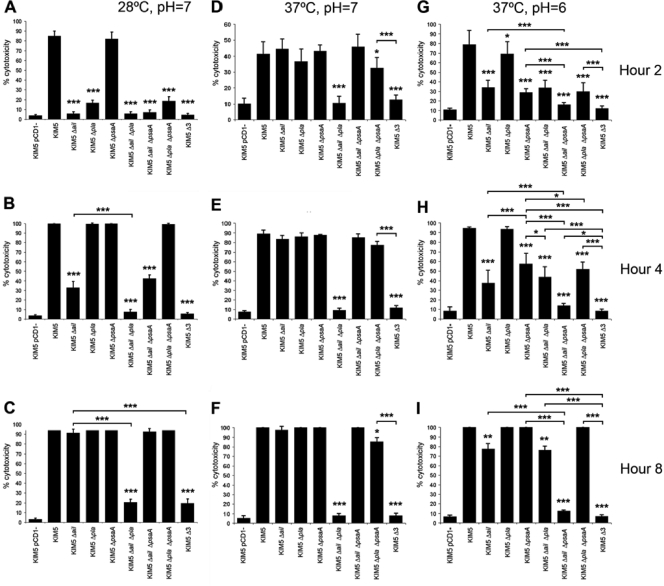

To quantify the contribution of each adhesin to Yop delivery, the efficiency of cytotoxicity mediated by each mutant strain on HEp-2 cells was determined by counting five fields and ∼500 total HEp-2 cells per KIM5 derivative at 2, 4, and 8 h postinoculation. Bacteria were again grown under all three culture conditions. As with the cell-binding assay (Fig. 2), the Δail mutant had the most dramatic effect on cytotoxicity of any single mutant when grown at 28°C and pH 7 (Fig. 3A to C). At hours 2 and 4 of the infection, the Δail mutant displayed 5% and 30% cytotoxicity, respectively, whereas the parental KIM5 strain was 85% and 100% cytotoxic at these two time points (Fig. 3A and B). By 8 h, the Δail mutant was nearly as cytotoxic as KIM5, but the Δail Δpla double mutant and Δail Δpla ΔpsaA triple mutant still showed only 20% cytotoxicity at 8 h postinoculation (Fig. 3C). In contrast, deletion of psaA had no effect on cytotoxicity under these assay conditions. Thus, as seen in the quantified adhesion assay, deletion of pla in addition to the Δail mutation resulted in a further decrease in cytotoxicity at 28°C and pH 7 (Fig. 3A to C).

FIG. 3.

Cytotoxicity time course for HEp-2 cells. Y. pestis KIM5 and mutant derivatives were added to HEp-2 cells, and cell rounding was observed at hours 2 (A, D, and G), 4 (B, E, and H), and 8 (C, F, and I). Strains were grown at 28°C and pH 7 (A to C), 37°C and pH 7 (D to F), or 37°C and pH 6 (G to I) prior to infection of cells. Cytotoxicity was quantified by counting rounded cells in 5 fields/strain (n, ∼500 cells). Δ3 denotes KIM5 Δail Δpla ΔpsaA. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.00005; ***, P < 0.000005. Error bars represent standard deviations.

When cells were pregrown at 37°C and pH 7 prior to infection of HEp-2 cells, both Ail and Pla played important roles in cytotoxicity (Fig. 3D to F), reflecting the cell adhesion data (Fig. 2C). As anticipated, at 37°C and pH 6, Psa now played an important role in cytotoxicity, although over the 8-h time course, the Δail mutant was more affected than the ΔpsaA mutant in mediating cytotoxicity. Combining the Δail and ΔpsaA mutations resulted in the most drastic defect in cytotoxicity at 37°C and pH 6, with only 12% cytotoxicity by 8 h postinoculation. Under these conditions, Pla played a minor role in cytotoxicity. Thus, Ail plays an important role in Yop delivery under all conditions tested, while Pla plays a role primarily at 37°C and pH 7 and Psa plays a role primarily at 37°C and pH 6. These environmental preferences reflect the known conditions for optimal expression of these adhesins (22, 55, 75) (Fig. 4).

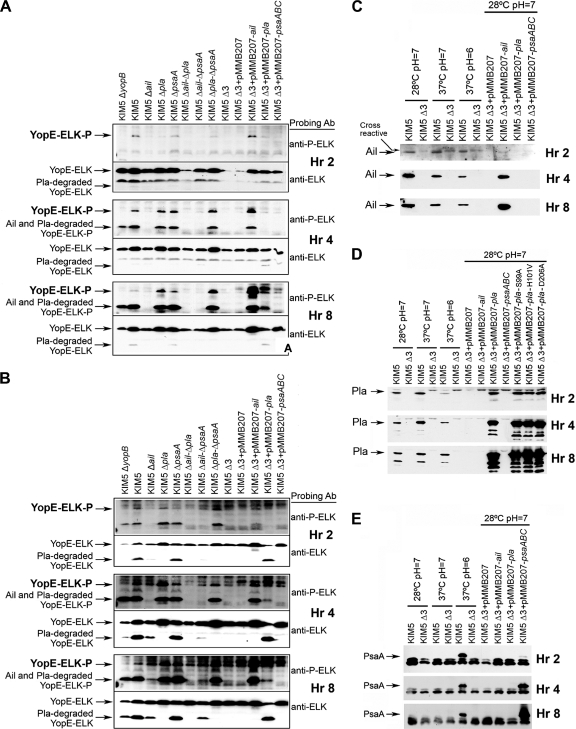

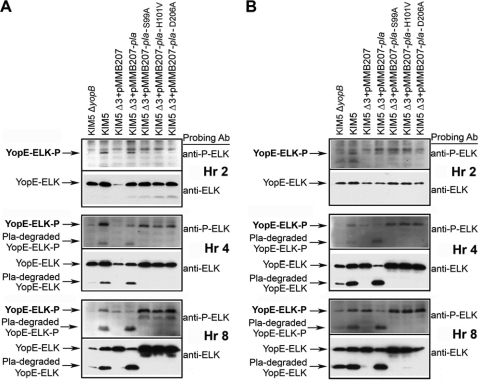

FIG. 4.

Yop delivery to eukaryotic cells. Yop translocation was measured by assessing delivery to and phosphorylation of ELK-tagged YopE from Y. pestis KIM5 and derivative strains in HEp-2 (A) and THP-1 (B) cells. Infected cells were harvested at 2, 4, and 8 postinoculation, and extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, using anti-phospho-ELK and anti-ELK antibodies. Extracts were also tested by Western blotting for Ail (C), Pla (D), and Psa (E) expression from an IPTG-inducible plasmid under various growth conditions over 8 h. A KIM5 ΔyopB strain (lacking a component of the Yop translocation apparatus) was included as a negative control. Δ3 denotes KIM5 Δail Δpla ΔpsaA.

Given that THP-1 cells are inherently rounded, we could not easily assess cytotoxicity in THP-1 cells with this assay but relied upon a secondary Yop delivery assay (Fig. 4) (16). These kinetic analyses of cytotoxicity are a powerful tool in observing intermediate delays in Yop delivery rather than relying upon a single time point.

Ail, Pla, and Psa restore YopE-ELK delivery to HEp-2 and THP-1 cells.

Our cytotoxicity studies indicated that Ail, Pla, and Psa are capable of facilitating delivery of Yops to host cells. As a more direct indicator of Yop translocation, we monitored the delivery of a YopE-ELK fusion protein that becomes phosphorylated when delivered to host cells (16, 22).

HEp-2 or THP-1 cells were infected with KIM5 derivatives carrying a YopE129-ELK-expressing plasmid, and cells were harvested at 2, 4, and 8 h postinoculation to assess the kinetics of Yop delivery. Cell extracts were used for Western blot analysis. As seen in the cytotoxicity assays, Ail was the major facilitator of YopE-ELK delivery to HEp-2 cells, as evidenced by the fact that the KIM5 Δail mutant showed almost no phospho-YopE-ELK over 8 h of infection in HEp-2 cells (Fig. 4A) and over 2 h of infection in THP-1 cells (Fig. 4B). Deletion of pla, psaA, or both genes had little or no effect on Yop delivery to HEp-2 cells or THP-1 cells (Fig. 4A and B). However, when overexpressed in a Δail Δpla ΔpsaA triple deletion strain (Δ3), each of the three adhesins, Ail, Pla, and Psa, could restore some level of Yop delivery to HEp-2 cells (Fig. 4A, 8 h) and THP-1 cells (Fig. 4B, 4h), above the background levels of YopE-ELK delivery observed with vector alone. Even under these overexpression conditions, Ail facilitated the most efficient Yop delivery, while Psa was the least efficient at restoring YopE-ELK delivery to host cells (Fig. 4).

As expected, a KIM5 ΔyopB strain did not translocate YopE-ELK to HEp-2 cells (Fig. 4A) (YopB is a component of the Yop translocation apparatus). Small amounts of YopE-ELK were phosphorylated in THP-1 cells after 4 and 8 h of infection with the KIM5 ΔyopB strain. This may have been the result of release of some YopE-ELK protein into the macrophage cytoplasm following phagocytosis (Fig. 4B). We observed moderate (30%) cytotoxicity by the KIM5 ΔyopB mutant in THP-1 cells in a separate study as well (73). During the course of these infections, some phospho-YopE-ELK was cleaved by Pla, and cleavage of Yops by Pla has been reported previously (46, 63, 67). However, we were able to detect this cleaved form of phospho-YopE-ELK and include it in our assessment of Yop delivery efficiencies (Fig. 4; see Materials and Methods). In addition, it should be noted that Ail cross-reacts with the anti-phospho-ELK antibody (Fig. 4; see Materials and Methods). We were able to distinguish between phospho-YopE-ELK and Ail by using an anti-ELK antibody that recognizes YopE-ELK and phospho-YopE-ELK but not Ail (Fig. 4).

Since a number of experiments utilized overexpressed adhesins to facilitate Yop delivery and cytotoxicity, we assessed the relative levels of each adhesin over an 8-h time course of cell infection to determine whether levels of Ail, Pla, and PsaA expression were similar to endogenous levels. Ail expression was difficult to detect at 2 h (presumably due to the small number of inoculated bacteria). Ail expressed from the IPTG-inducible plasmid was present but was less abundant than endogenous Ail (Fig. 4C). However, this reduced level of expression was sufficient to mediate Yop delivery (Fig. 1 and 4A and B). At hour 4, Ail was expressed from the plasmid at levels similar to those of endogenous Ail, and by 8 h, plasmid-expressed Ail exceeded endogenous Ail (Fig. 4C). Maximal Ail expression was achieved when bacteria were pregrown at 28°C and pH 7 (Fig. 4C). Endogenously encoded Pla was maximally expressed in cultures pregrown at 37°C and pH 7 (as expected [55]). When KIM5 Δ3 was grown at 28°C and pH 7 with an IPTG-inducible plasmid in the presence of HEp-2 cells, expression levels reached or surpassed endogenous levels by 2 h postinfection (Fig. 4D). Psa expression, on the other hand, took 2 to 4 h to reach endogenous levels (compared to cells grown at 37°C and pH 6) when psaABC was induced from a plasmid (Fig. 4E).

Plasminogen activator-mediated Yop delivery does not require proteolytic activity.

Plasminogen activator (Pla) has both proteolytic and adhesive activities (43, 74). Since we hypothesized that the adhesive activity would be most important for Yop delivery, we constructed three previously described (35) nonproteolytic mutants (Pla-S99A, Pla-H101V, and Pla-D206A) of Pla and expressed them in the KIM5 Δail Δpla ΔpsaA background to determine which activity is critical for Pla-mediated cytotoxicity. All three Pla mutants had no plasminogen activator activity (Fig. 5F), but all increased adhesion of strain KIM5 Δail Δpla ΔpsaA (Δ3) to both HEp-2 and THP-1 cells (Fig. 5A and B). Compared to that of the KIM5 parental strain, Pla-mediated cytotoxicity was slightly reduced at hour 2 for wild-type Pla and the three proteolytic mutants in the KIM5 Δ3 background (Fig. 5C), but it was similar to that of KIM5 by hours 4 and 8 (Fig. 5D and E). The proteolytic mutants also facilitated YopE-ELK delivery to HEp-2 cells and THP-1 cells (Fig. 6), although in HEp-2 cells, YopE-ELK delivery by the Pla proteolytic mutants was not readily observed until 4 h after infection, whereas wild-type Pla could deliver YopE-ELK to HEp-2 cells by hour 2 (Fig. 6A). The Pla proteolytic mutants were expressed at levels similar to that of wild-type Pla (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 5.

Adhesion and cytotoxicity of Pla and nonproteolytic Pla mutants to HEp-2 (A) and THP-1 (B) cells after 2 h of incubation. (C to E) Time course quantification of cell rounding for HEp-2 cells. (F) Fluorescence cleavage assay for detection of Pla proteolytic activity. RFU, relative fluorescence units. Δ3 denotes KIM5 Δail Δpla ΔpsaA. Error bars represent standard deviations.

FIG. 6.

Yop translocation to HEp-2 and THP-1 cells by Pla mutants defective for proteolysis. HEp-2 (A) and THP-1 (B) cells were infected with KIM5 derivatives, and Western immunoblotting was performed for total ELK and phosphorylated ELK at the indicated time points. Δ3 denotes KIM5 Δail Δpla ΔpsaA.

Use of these Pla proteolytic mutants allowed us to address the fact that some YopE-ELK and phospho-YopE-ELK was cleaved during these assays by Pla. We observed a lower band reacting with both anti-ELK and anti-phospho-ELK antibodies at hours 4 and 8 for both cell types. This band was missing for the nonproteolytic mutants and strains expressing no pla (Fig. 6). This indicates that the protease activity of Pla can degrade YopE-ELK, presumably during transfer to host cells, confirming what we observed previously (Fig. 4). Since the starting strain for this analysis lacked Ail (KIM5 Δail Δpla ΔpsaA), all degraded phospho-YopE-ELK or YopE-ELK product detected was derived from YopE-ELK, and none was due to the cross-reactivity of Ail to the anti-phospho-ELK antibody (see Materials and Methods). As seen previously (Fig. 4), the ΔyopB strain showed some phospho-YopE-ELK by hour 8 in THP-1 cells.

Adhesins are required for mouse virulence.

Delivery of cytotoxic Yop proteins during plague infection is a critical mechanism of pathogenesis for Y. pestis. Since we determined that three adhesins of Y. pestis (Ail, Pla, and Psa) were capable of mediating Yop delivery in vitro (either at endogenous levels or when artificially induced), we determined the contribution of each adhesin to plague virulence. Given that we had previously reported a strong virulence defect (>3,000-fold increase in LD50) for a KIM5 Δail mutant (22), we hypothesized that deletion of multiple adhesins may reveal partially redundant functions of the three adhesins in vivo.

Swiss Webster mice were inoculated i.v. with increasing doses of KIM5 or single, double, or triple mutants of ail, pla, and psaA, and the LD50s were determined. The LD50s for Y. pestis KIM5 ranged between 1 and 14 bacteria over several experiments, with a cumulative LD50 of 7 bacteria over all experiments (Table 3). Of the single deletions, deletion of ail affected virulence most dramatically (Table 3), similar to what was reported previously (22). In the current studies, we found a ΔpsaA mutant to be attenuated variably (depending on the experiment), with a cumulative LD50 of 530 bacteria over several experiments (Table 3). The KIM5 Δpla strain was slightly less attenuated in mice, with an LD50 of 250 bacteria, similar to the case in previous studies of a pla-negative strain via the i.v. route of infection (9).

TABLE 3.

Virulence of various Y. pestis KIM5 mutantsa

| Conditions and strain | Probit LD50 (Reed-Muench LD50) | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Pregrowth at 28°C and pH 7 | ||

| KIM5 | 7 (8) | 4-10 |

| KIM5 Δailb | 21,000 (21,000) | 3,000-186,000 |

| KIM5 ΔpsaA | 530 (500) | 170-2,900 |

| KIM5 Δpla | 250 (280) | 76-58,000 |

| KIM5 Δail ΔpsaA | 940,000 (635,000) | NA |

| KIM5 Δail Δpla | 31,000 (64,000) | NA |

| KIM5 ΔpsaA Δpla | (24,000)c | NA |

| KIM5 Δail ΔpsaA Δpla | 420,000 (600,000) | 31,000-1,000,000 |

| KIM5 pCD1− | 30,000,000 (49,000,000) | NA |

| Pregrowth at 37°C and pH 7 | ||

| KIM5 | 27 (34) | NA |

| KIM5Δail | 220,000 (21,000) | 14,000-NUB |

Results of mouse virulence assays for Y. pestis KIM5 and mutant derivatives after i.v. inoculation. Mice were inoculated i.v. with 5- to 10-fold increasing doses of each strain. All mutants were tested at 10 animals/dose, and some mutants were tested in additional experiments with 4 to 8 animals/dose. Mice were observed for 16 days for survival, and LD50s were determined by probit analysis and the method of Reed and Muench (58). As a negative control, a pCD1− strain, lacking the Yop-encoding virulence plasmid, was included. In some cases, probit analysis was unable to assign confidence intervals (NA, not available), but Reed-Muench analysis gave similar LD50s. NUB denotes no upper bound for confidence interval.

Probit analysis was unable to calculate an LD50 (due to reduced mouse lethality at the highest infection doses, potentially due to immune clearance). In this case, we relied upon the Reed-Muench LD50, with the acknowledgment that this mutant has an unusual behavior in vivo.

To assess whether certain adhesins may serve redundant functions during infection, we analyzed double and triple mutants. Combining the Δail and ΔpsaA mutations gave a cumulative reduction in virulence beyond the effect of the Δail mutation alone. The ΔpsaA mutation caused a 45-fold further reduction in the LD50 of the Δail mutant, whereas the Δpla mutation showed a modest (<2-fold) effect on the LD50 of the Δail strain (Table 3). When the ΔpsaA and Δpla mutations were combined, the resulting KIM5 ΔpsaA Δpla mutant had an LD50 of 24,000 bacteria, indicating a cumulative effect on virulence of these two mutations in KIM5 (Table 3). It should be noted that due to the lethality responses to this strain, we had to rely upon Reed and Muench analysis (58) to calculate the LD50, as fewer mice died at the highest doses. This is a curious phenomenon that may relate to triggering of a robust immune response when the host is challenged with high doses of the ΔpsaA Δpla mutant. Finally, a Δail ΔpsaA Δpla triple mutant was attenuated, similar to the Δail ΔpsaA double mutant, with an LD50 of 420,000 bacteria (Table 3). This level of attenuation is only 70-fold less severe than that of a pCD1-negative derivative of KIM5 which is a completely avirulent strain (Table 3) (22, 69). At doses between 107 and 108 bacteria, death in mice becomes Yop independent and may be due to LPS, murine toxin (28), or other Y. pestis factors (Felek and Krukonis, unpublished observations). In some cases, probit analysis used for LD50 determination could not assign confidence intervals, as no doses gave >50% lethality or the data were not normally distributed. For these strains, we present the Reed-Muench LD50 as well, for comparison. These in vivo results are consistent with results indicating that Ail, Pla, and Psa play a role in Yop delivery in vitro. In addition, functions related to the protease activity of Pla or other activities of Ail, Pla, and Psa may play roles in virulence in vivo (6, 29, 33).

Since the KIM5 Δail mutant had the most severe virulence defect of all the single mutants, we also tested this strain for virulence attenuation when it was pregrown at 37°C and pH 7 prior to inoculation. These growth conditions mimic late stages of bubonic plague, when the infection spreads from the lymphatic system to the blood to cause systemic disease after adapting to 37°C in the host (54). While the LD50 for the parental KIM5 strain was slightly higher under these conditions (LD50 of 27 bacteria) (Table 3), the Δail mutant gave a much higher LD50 (220,000 bacteria by probit analysis and 21,000 bacteria by Reed-Muench analysis) (Table 3). Thus, even at later stages of infection (after adaptation to 37°C), Ail plays an important role in infection.

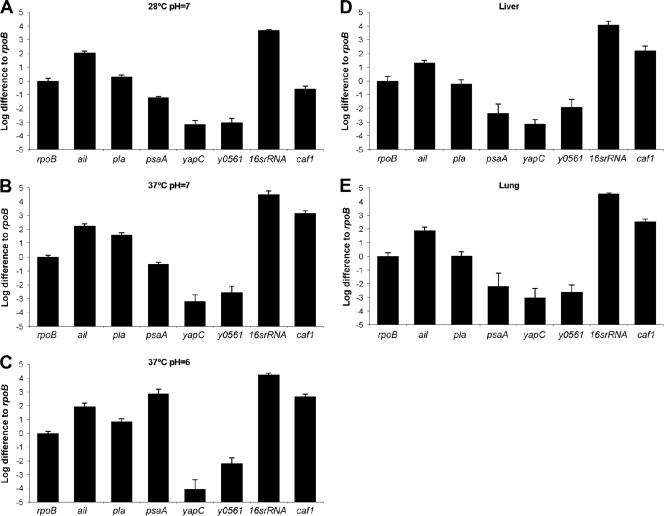

Expression levels of Ail, Pla, and Psa.

For an adhesin to play a role at a particular stage of infection, it must be expressed at that time and location. Based on the differences in attenuation for each adhesin mutant (Table 3), we sought to determine the level of expression of each adhesin during a mouse infection to establish its potential to affect virulence. To establish standardized levels of expression, we first grew KIM5 under three different in vitro conditions, namely, 28°C and pH 7 (flea-like conditions), 37°C and pH 7 (infection conditions), and 37°C and pH 6 (phagolysosomal and abscess conditions, known to induce pH 6 antigen [41]), and then analyzed samples by qRT-PCR, using the housekeeping gene rpoB as a normalization control. At 28°C and pH 7, ail was strongly expressed (100-fold above rpoB level), while pla and psaA were expressed at lower levels, i.e., 2-fold above and 10-fold below the rpoB level, respectively (Fig. 7A). When cultures were grown at 37°C, ail was still strongly expressed, but pla was also expressed much more abundantly than at 28°C (30-fold above rpoB level) (Fig. 7B). We also assessed the expression of caf1, the capsule-encoding gene, known to be induced strongly at 37°C, as a positive control. caf1 was expressed at 37°C to levels 1,000-fold higher than the rpoB level (Fig. 7B). While psaA was also increased at 37°C and pH 7 (4-fold below rpoB level), it was much more strongly expressed under its optimal conditions of 37°C and pH 6 (500-fold above rpoB level) (Fig. 7C). Thus, in vitro, ail is consistently expressed (in agreement with its presence as a major outer membrane protein [2, 22, 34]), and pla and psaA are induced under specific conditions. Expression of yapC and y0561 was low under all in vitro conditions tested (Fig. 7A to C).

FIG. 7.

Transcription levels of ail, pla, psaA, yapC, y0561, 16S rRNA gene, and caf1. Expression levels were determined in vitro under different growth conditions (A to C) and in vivo in livers (D) and lungs (E). All values are presented relative to rpoB expression. For in vivo samples, mice were infected i.v. with 960 CFU Y. pestis KIM5 and then sacrificed on day 4, and qRT-PCR was performed on liver and lung specimens. The colonization levels for tissues used for qRT-PCR were as follows: for liver tissue, 13,000,000 CFU/g; and for lung tissue, 3,000,000 CFU/g. Ten milligrams of tissue was used to generate mRNA for liver and lung tissues. Error bars represent standard deviations.

To determine the in vivo transcription levels of ail, pla, and psaA, we infected mice i.v. with KIM5. After i.v. infection, we observed accumulation of Y. pestis KIM5 in the liver and spleen over the first few days, with spread to the lungs by days 2 and 3 (22). Therefore, mice were sacrificed on day 4, and qRT-PCR was performed on liver and lung specimens. Triplicate wells were run for each sample, and assays were repeated two times. Transcription levels were normalized to rpoB gene transcription levels, and rpoB expression was set to 1 (log10 1 = 0) (Fig. 7; see Materials and Methods). Again, caf1 served as a positive control, as a Y. pestis gene induced at 37°C in the mouse (about 100-fold above rpoB levels in both tissues) (Fig. 7D and E). qRT-PCRs with liver and lung samples showed that ail was highly expressed (10- to 100-fold above rpoB levels) in both tissues and that pla and psaA were expressed at somewhat lower levels (Fig. 7D and E). The levels of pla and psaA expression in liver and lung tissues were about 10-fold less than those seen in vitro at 37°C and pH 7, suggesting that other factors may limit their expression in vivo (Fig. 7D and E). Like the in vitro results, yapC and y0561 were expressed at low levels in vivo (Fig. 7D and E). Thus, as predicted from in vitro adhesion and Yop delivery analyses and the major effect of Ail on virulence, these in vivo expression studies are consistent with Ail serving as a primary adhesin to promote efficient Y. pestis infection.

DISCUSSION

Adhesins are important for the targeting of T3SS-delivered toxins to host cells (8, 59, 71). To initiate a productive Y. pestis infection, a number of Yop effectors are secreted through the Ysc T3S apparatus (13, 54). Y. pestis Ail has been shown previously to mediate cell adhesion (22, 34) and to facilitate Yop delivery (22). While a Y. pestis KIM5 Δail mutant has a strong virulence defect, with a >3,000-fold increase in LD50, the level of attenuation is not as severe as that of a strain lacking the Yop-encoding plasmid, pCD1 (4.3 × 106-fold increase in LD50) (Table 3). Thus, we sought to investigate the roles of four other defined adhesins of Y. pestis in Yop delivery and virulence. In addition to Ail, we found that Pla and Psa can facilitate Yop delivery when expressed from a plasmid in a strain lacking all five known adhesins (KIM5 Δ5) (Fig. 1). While the autotransporter YapC and the chaperone/usher locus-encoded protein y0561 modestly increase binding to HEp-2 cells and the THP-1 macrophage cell line (Fig. 1A) (23, 24), they do not facilitate Yop translocation under these conditions (Fig. 1). Initial complementation studies with the KIM5 Δ5 strain suggested the order Ail > Pla > Psa for efficiency of Yop delivery (Fig. 1C). However, kinetic analysis of protein expression demonstrated that PsaA is not expressed at endogenous levels until some time between 2 and 4 h postinduction (Fig. 4E). Thus, this kinetic delay in Psa expression likely explains the poor Psa-mediated Yop delivery at hour 2 postinoculation (Fig. 1C).

Studies in which the genes encoding each of the three adhesins capable of delivering Yops (Ail, Pla, and Psa) were deleted demonstrated that each adhesin plays an environmentally specific role in cell binding and Yop delivery. While Ail can contribute to adhesion and cytotoxicity when Y. pestis is pregrown under three different culture conditions (28°C and pH 7, 37°C and pH 7, and 37°C and pH 6) (Fig. 2 and 3), Pla has its strongest effects on cell binding and cytotoxicity at 28°C and pH 7 and at 37°C and pH 7 (Fig. 2A to C and 3A to F), with a minor role at 37°C and pH 6. As predicted from studies characterizing the expression patterns of Psa (4, 57, 75), this adhesin played a role in cell adhesion and cytotoxicity when Y. pestis was pregrown at 37°C and pH 6 (Fig. 2D and 3G to I). These cell-binding assay and cytotoxicity results correlate well with the endogenous protein expression levels of Ail, Pla, and Psa (Fig. 4C to E).

A number of other studies have also indicated that Pla and Psa can contribute to Yop delivery. Rosqvist et al. showed that YadA and invasin are capable of mediating reestablishment of Yop delivery from Y. pestis strain EV76p (59). EV76 is a pigmentation-negative strain (lacking the 102-kb pgm locus) (25) of Y. pestis. We found that the parental EV76 strain was capable of mediating Yop delivery when grown at 37°C and pH 7 prior to inoculation of HEp-2 cells. However, when pla was deleted in strain EV76 (EV76 Δpla; similar to EV76p in reference 59), a delay of several hours in Yop delivery to HEp-2 cells was observed (21; data not shown). These results indicate that Pla can play an important role in Yop delivery when Y. pestis EV76 is grown at 37°C and pH 7. In the studies presented here for strain KIM5 grown at 37°C and pH 7, deletion of pla affected Yop delivery only when combined with the Δail mutation. While a derivative of EV76, EV76-51F, harbors IS285 insertion elements within the ail gene (72), the ail locus of EV76 is intact and is expressed (Felek and Krukonis, unpublished data). It remains unclear why KIM5 and EV76 have different adhesin requirements for Yop delivery at 37°C and pH 7.

In our current studies, we demonstrated that the roles of Pla in cell binding and Yop delivery are largely independent of the proteolytic activity of Pla, as there was only a slight delay in cytotoxicity and Yop delivery by nonproteolytic Pla mutants (Fig. 5 and 6, respectively).

Several independent observations demonstrate the ability of Psa to dock with cells and facilitate T3S effector delivery. Here we showed that when Y. pestis was pregrown at 37°C and pH 6.0 prior to inoculation into HEp-2 cells, deletion of psaA in KIM5 resulted in reduced cytotoxicity at 2 and 4 h postinoculation (Fig. 3G to I). Thus, under conditions of increased acidity and 37°C (mimicking phagolysosomes or necrotic tissue), Psa is expressed and can mediate Yop delivery. Psa is known to be induced within phagolysosomes of cultured macrophages (41). Furthermore, Psa is capable of heterologously restoring adhesion and T3S of ExoS to an adhesion-defective mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (71). We also demonstrated here that artificially induced expression of Psa resulted in cell binding and Yop delivery (Fig. 1 and 4).

Mouse infections by mutants lacking multiple adhesins revealed some cumulative defects (Table 3). Pla is required for dissemination of Y. pestis from a subcutaneous inoculation site to the liver and spleen (66) but is not required for productive i.v. infection (9). Recently, Pla was demonstrated to be important for development of fulminant pneumonic plague (39). In our study, we found a 36-fold increase in LD50 for KIM5 Δpla and a 76-fold increase in LD50 for KIM5 ΔpsaA. These effects are similar to those in previous studies (9, 40). When both pla and psaA were deleted, the LD50 increased 3,400-fold compared to that of KIM5, as predicted for cumulative defects. Deletion of pla caused a 4-fold decrease in Yop-mediated cytotoxicity at 2 h when cells were grown at 28°C and pH 7 in vitro (Fig. 3A). By hour 4 under these growth conditions, the pla mutant had wild-type cytotoxic activity. When cells were grown at 37°C and pH 7, deletion of pla resulted in a defect in cytotoxicity only when combined with a Δail mutation (Fig. 3D to F). The Δail Δpla double mutant also had the most dramatic and persistent defect in cytotoxicity when Y. pestis was grown at 28°C and pH 7 (Fig. 3A to C). Thus, at pH 7, for Y. pestis grown at either 28°C or 37°C, Pla and Ail combined to facilitate maximal Yop delivery in vitro. Furthermore, they appeared to confer redundant mechanisms of Yop delivery.

When Y. pestis was pregrown at 37°C and pH 6, we observed a Yop delivery defect in the ΔpsaA mutant (Fig. 3G to I). Thus, much of the attenuation of the Δpla ΔpsaA double mutant may be explained by the delayed Yop delivery by this strain under various growth conditions (Fig. 3). Other activities of Pla and Psa may also contribute to the increased LD50s of the Δpla, ΔpsaA, and Δpla ΔpsaA mutants (Table 3). Likewise, the cumulative virulence defect caused by successive deletion of ail, psaA, and pla (Table 3) is consistent with a reduced ability to deliver Yops during infection, as demonstrated in vitro (Fig. 3). Although Ail has a secondary virulence function of conferring serum resistance (2, 7, 33, 34, 56), a KIM5 Δail mutant did not show increased sensitivity to mouse serum (2). Thus, defects in mouse virulence due to the Δail mutation are likely attributable to impaired cell adhesion and Yop delivery. Why the KIM5 Δail Δpla ΔpsaA (Δ3) mutant is not completely avirulent in vivo is not clear. There may be some level of adhesin-independent Yop delivery in vivo, especially to phagocytic cells. By hours 4 and 8 in our in vitro Yop delivery assay with THP-1 macrophage cells, we observed some YopE-ELK delivery to host cells by the KIM5 Δ3 strain (Fig. 4B). Alternatively, additional adhesins may be expressed in vivo that facilitate modest levels of Yop delivery.

It has been shown previously that opsonization-mediated adhesion of Yersinia to host cells can facilitate Yop delivery and inhibition of phagocytosis via interactions of Yersinia-bound IgG with Fc receptors (20). This could potentially occur via C3b-opsonized Yersinia binding to complement receptors as well. In addition to mediating direct adhesion to host cells, Ail can also recruit the complement regulatory proteins factor H (6) and C4b binding protein (C4bp) (33), which lead to the degradation of C3b and/or dissociation of the C3-convertase complex. Thus, one effect of deleting ail in vivo, in addition to impaired Yop delivery due to decreased direct adhesion by Ail, could be via increased phagocytosis due to impaired C3b degradation and increased C3b generation in a Δail mutant.

One unanticipated finding of our studies was that YopE-ELK appears to be susceptible to Pla-mediated cleavage during (or prior to) transfer to eukaryotic cells via T3S, since we could detect YopE-ELK-P that was cleaved in a Pla-dependent fashion (Fig. 4A and B). One simple explanation for the cleavage of YopE-ELK-P is that YopE-ELK-P leaks out of intoxicated cells and becomes cleaved by surface-localized Pla on attached Y. pestis cells. However, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assays using HEp-2 and THP-1 cells indicated that during the time course we analyzed, cells were intact and little to no LDH leakage occurred (data not shown). During harvest of the extracts for Western blot analysis, YopE-ELK-P may have been accessible to Pla. However, extractions were performed in SDS sample buffer in the presence of protease inhibitors, making Pla activity in these extracts unlikely. We are left to consider the intriguing possibility that YopE-ELK is first secreted to the surface of Y. pestis (where it would be susceptible to Pla) and then targeted for T3S-dependent delivery to host cells. This idea has been proposed previously (31) and may suggest a new model for Yop delivery. Alternatively, T3S substrates may be accessible to the outer membrane protease Pla as they traverse the T3S needle apparatus during secretion.

The timing of psaABC induction may be critical in determining whether Psa promotes the establishment of a plague infection. A psa mutant has been reported to have a 200-fold increase in the LD50 for mice after i.v. inoculation (40). We observed somewhat variable results over several experiments with a similar KIM5 ΔpsaA in-frame deletion mutant in mice, resulting in a cumulative LD50 that was 76-fold above that of the parental KIM5 strain (Table 3). Other studies using different routes of infection have also demonstrated modest or negligible effects of a psa mutation on virulence (1, 11). Analysis of expression of the psa locus during pulmonary infection has given rise to two studies, one indicating that psaA is strongly downregulated in the lung (strain CO92) (38) and one indicating that psa is upregulated during pulmonary infection (strain 201) (42). These studies have a number of important differences. In the first study, the inoculated bacteria were pregrown at 37°C, and thus the Caf1 capsule was presumably being produced at the time of infection. Since Caf1 is known to be antiphagocytic (19), this likely prevented the engulfment of Y. pestis by pulmonary phagocytes. It is within this intracellular niche that psaABC has been shown to be induced (41). Thus, it is not surprising that the psaABC locus was not upregulated in this study and even appears to have been downregulated relative to that in broth-grown 37°C in vitro cultures. In the second study (42), bacteria were pregrown at 26°C prior to inoculation and gene expression was monitored at several time points during infection (42). At early time points, when cells grown at 26°C were likely being engulfed by pulmonary phagocytes, psaA was shown to be induced 10-fold compared to that in the inoculum. However, as the infection progressed, psaA became downregulated, such that by 48 h postinfection, psaA was slightly downregulated relative to that in the broth-grown culture. The 48-h time point was also the time point used in the study with strain CO92 (38). Presumably, in the latter study, as Y. pestis adapted to the 37°C conditions of the host, Caf1 was produced and the mainly extracellular Y. pestis remained extracellular due to the antiphagocytic function of the Caf1 capsule. This would prevent further upregulation of psaA.

In our infection system, Psa accounts for most of the detectable virulence in the absence of Ail, as the Δail ΔpsaA and Δail Δpla ΔpsaA mutants had similar virulence defects and the Δail Δpla mutant had a similar LD50 to that of the Δail single mutant (Table 3). However, we did not detect levels of psaA expression in tissues from infected mice that approached the level of psaA expression in vitro at 37°C and pH 6 (Fig. 7). This may indicate that only a small subpopulation of Y. pestis bacteria express Psa by day 4 postinfection and that the frequency of induction is insufficient to be detected by qRT-PCR analysis of the entire bacterial population. If so, then those few bacteria expressing Psa are capable of contributing to disease. It is also possible that PsaA was required early on in the infection (days 1 to 3) but had been downregulated by day 4, when tissues were harvested for transcription analysis in this study. This would be similar to a previous study of pneumonic plague where psaA was induced in the lungs during the early stages of infection but was downregulated by 48 h postinfection (42). In that study, expression of psaA remained high in liver and spleen tissues through the 48-h time point, but that was the latest time point tested (42). One other possibility we considered was that in the absence of Ail, Y. pestis may compensate for the loss of Ail by inducing expression of the secondary adhesin Psa at a higher frequency. However, tissues harvested from moribund animals infected with the KIM5 Δail strain did not indicate any higher level of psaA expression than those for animals infected with the parental KIM5 strain (data not shown).

Our results indicate that Ail, Pla, and Psa can all contribute to Yop translocation and cytotoxicity in host cells, depending upon the environmental conditions in which Y. pestis is found. Experiments relying upon endogenous levels of protein expression established a hierarchy of efficiency of Yop delivery: Ail > Pla > Psa at 28°C and pH 7, Ail = Pla > Psa at 37°C and pH 7, and Ail ≥ Psa > Pla at 37°C and pH 6 (Fig. 3). Furthermore, in our infection model, Ail and Psa are major contributors to Y. pestis virulence (Table 3). In contrast, even under overexpression conditions, two additional Y. pestis adhesins, YapC and y0561, do not facilitate Yop delivery. Future studies can now evaluate the critical parameters for efficient Yop delivery, such as avidity/density of receptor binding, the choice of receptor by each adhesin, and/or the downstream signaling events triggered by each specific receptor engagement mechanism, as suggested in previous studies (47).

Acknowledgments

We thank Timo Korhonen for providing anti-Pla antibody. We thank Ralph Isberg for providing anti-Ail antibody (directed against Y. pseudotuberculosis Ail [76]). We thank Susan Straley for providing anti-Psa antibody. We thank Virginia Miller and Matthew Lawrenz for providing anti-YapC antibody. We thank Robert Perry for supplying the Y. pestis strain EV76 and Greg Plano for providing an isolate of Y. pestis KIM5 Δail for experiments confirming the virulence defect of this strain. We thank Hans Wolf-Watz for allowing us to reference data presented at the 9th International Symposium on Yersinia and for helpful discussions. We thank Michele Swanson and Chris Fenno for critical readings of the manuscript.

This study was supported by funding from the University of Michigan Biomedical Research Council (BMRC), the Office of the Vice President of Research (OVPR), and the Rackham Graduate School. T.M.T. was funded by the Frances Wang Chin Endowed Fellowship from the University of Michigan Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 August 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anisimov, A. P., I. V. Bakhteeva, E. A. Panfertsev, T. E. Svetoch, T. B. Kravchenko, M. E. Platonov, G. M. Titareva, T. I. Kombarova, S. A. Ivanov, A. V. Rakin, K. K. Amoako, and S. V. Dentovskaya. 2009. The subcutaneous inoculation of pH 6 antigen mutants of Yersinia pestis does not affect virulence and immune response in mice. J. Med. Microbiol. 58:26-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartra, S. S., K. L. Styer, D. M. O'Bryant, M. L. Nilles, B. J. Hinnebusch, A. Aballay, and G. V. Plano. 2008. Resistance of Yersinia pestis to complement-dependent killing is mediated by the Ail outer membrane protein. Infect. Immun. 76:612-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bearden, S., J. Fetherston, and R. Perry. 1997. Genetic organization of the yersiniabactin biosynthetic region and construction of avirulent mutants in Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 65:1659-1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Efraim, S., M. Aronson, and L. Bichowsky-Slomnicki. 1961. New antigenic component of Pasteurella pestis formed under specified conditions of pH and temperature. J. Bacteriol. 81:704-714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bichowsky-Slomnicki, L., and S. Ben-Efraim. 1963. Biological activities in extracts of Pasteurella pestis and their relation to the “pH 6 antigen.” J. Bacteriol. 86:101-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biedzka-Sarek, M., H. Jarva, H. Hyytiainen, S. Meri, and M. Skurnik. 2008. Characterization of complement factor H binding to Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:3. Infect. Immun. 76:4100-4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bliska, J., and S. Falkow. 1992. Bacterial resistance to complement killing mediated by the Ail protein of Yersinia enterocolitica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:3561-3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd, A. P., N. Grosdent, S. Totemeyer, C. Geuijen, S. Bleves, M. Iriarte, I. Lambermont, J.-N. Octave, and G. R. Cornelis. 2000. Yersinia enterocolitica can deliver Yop proteins into a wide range of cell types: development of a delivery system for heterologous proteins. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 79:659-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brubaker, R. R., E. D. Beesley, and M. J. Surgalla. 1965. Pasteurella pestis: role of pesticin I and iron in experimental plague. Science 149:422-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantor, N. 2001. In the wake of the plague. Perennial, New York, NY.

- 11.Cathelyn, J. S., S. D. Crosby, W. W. Lathem, W. E. Goldman, and V. L. Miller. 2006. RovA, a global regulator of Yersinia pestis, specifically required for bubonic plague. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:13514-13519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavigelli, M., F. Dolfi, F. X. Claret, and M. Karin. 1995. Induction of c-fos expression through JNK-mediated TCF/Elk-1 phosphorylation. EMBO J. 14:5957-5964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornelis, G. R., A. Boland, A. P. Boyd, C. Geuijen, M. Iriarte, C. Neyt, M.-P. Sory, and I. Stainier. 1998. The virulence plasmid of Yersinia, an antihost genome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1315-1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowan, C., H. Jones, Y. Kaya, R. Perry, and S. Straley. 2000. Invasion of epithelial cells by Yersinia pestis: evidence for a Y. pestis-specific invasin. Infect. Immun. 68:4523-4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Day, J. B., F. Ferracci, and G. V. Plano. 2003. Translocation of YopE and YopN into eukaryotic cells by Yersinia pestis yopN, tyeA, sycN, yscB and lcrG deletion mutants measured using a phosphorylatable peptide tag and phosphospecific antibodies. Mol. Microbiol. 47:807-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng, W., V. Burland, G. Plunkett III, A. Boutin, G. F. Mayhew, P. Liss, N. T. Perna, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, S. Zhou, D. C. Schwartz, J. D. Fetherston, L. E. Lindler, R. R. Brubaker, G. V. Plano, S. C. Straley, K. A. McDonough, M. L. Nilles, J. S. Matson, F. R. Blattner, and R. D. Perry. 2002. Genome sequence of Yersinia pestis KIM. J. Bacteriol. 184:4601-4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennis, D. T., and P. S. Mead. 2010. Yersinia species, including plague, p. 2943-2949. In G. L. Mandell, J. E. Bennett, and R. Dolin (ed.), Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases, 7th ed. Elsevier Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- 19.Du, Y., R. Rosqvist, and A. Forsberg. 2002. Role of fraction 1 antigen of Yersinia pestis in inhibition of phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 70:1453-1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fällman, M., K. Andersson, S. Hakansson, K. E. Magnusson, O. Stendahl, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1995. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis inhibits Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in J774 cells. Infect. Immun. 63:3117-3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Felek, S., and E. S. Krukonis. 2006. Analysis of three Yersinia pestis adhesins capable of delivering Yops to host cells, p. 52. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Yersinia, Lexington, KY. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 22.Felek, S., and E. S. Krukonis. 2009. The Yersinia pestis Ail protein mediates binding and Yop delivery to host cells required for plague virulence. Infect. Immun. 77:825-836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felek, S., M. B. Lawrenz, and E. S. Krukonis. 2008. The Yersinia pestis autotransporter YapC mediates host cell binding, autoaggregation and biofilm formation. Microbiology 154:1802-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felek, S., L. M. Runco, D. G. Thanassi, and E. S. Krukonis. 2007. Characterization of six novel chaperone/usher systems in Yersinia pestis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 603:97-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fetherston, J. D., P. Schuetze, and R. D. Perry. 1992. Loss of the pigmentation phenotype in Yersinia pestis is due to the spontaneous deletion of 102 kb of chromosomal DNA which is flanked by a repetitive element. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2693-2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galvan, E. M., H. Chen, and D. M. Schifferli. 2007. The Psa fimbriae of Yersinia pestis interact with phosphatidylcholine on alveolar epithelial cells and pulmonary surfactant. Infect. Immun. 75:1272-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goguen, J. D., T. Bugge, and J. L. Degen. 2000. Role of the pleiotropic effects of plasminogen deficiency in infection experiments with plasminogen-deficient mice. Methods 21:179-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinnebusch, B. J., A. E. Rudolph, P. Cherepanov, J. E. Dixon, T. G. Schwan, and A. Forsberg. 2002. Role of Yersinia murine toxin in survival of Yersinia pestis in the midgut of the flea vector. Science 296:733-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang, X.-Z., and L. E. Lindler. 2004. The pH 6 antigen is an antiphagocytic factor produced by Yersinia pestis independent of yersinia outer proteins and capsule antigen. Infect. Immun. 72:7212-7219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iriarte, M., and G. R. Cornelis. 1998. YopT, a new Yersinia Yop effector protein, affects the cytoskeleton of host cells. Mol. Microbiol. 29:915-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isaksson, E. L., J. Olsson, A. Bjornfot, R. Rosqvist, M. Aili, K. E. Carlsson, M. S. Francis, M. Hamberg, J. Klumperman, and H. Wolf-Watz. 2006. Effector translocation is mediated by a surface located protein complex of Y. pseudotuberculosis, p. 20-21. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Yersinia, Lexington, KY. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 32.Kienle, Z., L. Emody, C. Svanborg, and P. O'Toole. 1992. Adhesive properties conferred by the plasminogen activator of Yersinia pestis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:1679-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirjavainen, V., H. Jarva, M. Biedzka-Sarek, A. M. Blom, M. Skurnik, and S. Meri. 2008. Yersinia enterocolitica serum resistance proteins YadA and Ail bind the complement regulator C4b-binding protein. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolodziejek, A. M., D. J. Sinclair, K. S. Seo, D. R. Schnider, C. F. Deobald, H. N. Rohde, A. K. Viall, S. S. Minnich, C. J. Hovde, S. A. Minnich, and G. A. Bohach. 2007. Phenotypic characterization of OmpX, an Ail homologue of Yersinia pestis KIM. Microbiology 153:2941-2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kukkonen, M., K. Lahteenmaki, M. Suomalainen, N. Kalkkinen, L. Emody, H. Lang, and T. K. Korhonen. 2001. Protein regions important for plasminogen activation and inactivation of alpha-2 antiplasmin in the surface protease Pla of Yersinia pestis. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1097-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lahteenmaki, K., M. Kukkonen, and T. K. Korhonen. 2001. The Pla surface protease/adhesin of Yersinia pestis mediates bacterial invasion into human endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 504:69-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lahteenmaki, K., R. Virkola, A. Saren, L. Emody, and T. K. Korhonen. 1998. Expression of plasminogen activator Pla of Yersinia pestis enhances bacterial attachment to the mammalian extracellular matrix. Infect. Immun. 66:5755-5762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lathem, W. W., S. D. Crosby, V. L. Miller, and W. E. Goldman. 2005. Progression of primary pneumonic plague: a mouse model of infection, pathology, and bacterial transcriptional activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:17786-17791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lathem, W. W., P. A. Price, V. L. Miller, and W. E. Goldman. 2007. A plasminogen-activating protease specifically controls the development of primary pneumonic plague. Science 315:509-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindler, L., M. Klempner, and S. Straley. 1990. Yersinia pestis pH 6 antigen: genetic, biochemical, and virulence characterization of a protein involved in the pathogenesis of bubonic plague. Infect. Immun. 58:2569-2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindler, L. E., and B. D. Tall. 1993. Yersinia pestis pH 6 antigen forms fimbriae and is induced by intracellular association with macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 8:311-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]