Abstract

Clumping factor A (ClfA) is a fibrinogen-binding cell wall-attached protein and an important virulence factor of Staphylococcus aureus. Previous studies reported that an immunization with the fibrinogen-binding domain of ClfA (ClfA40-559) protected animals against S. aureus infection. It was reported that some cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of staphylococcal diseases and in host defense against S. aureus infection. However, the role of cytokines in the protective effect of ClfA40-559 as a vaccine has not been elucidated. In this study, we demonstrated that the spleen cells of ClfA40-559-immunized mice produced a large amount of interleukin-17A (IL-17A). The protective effect of immunization was exerted in wild-type mice but not in IL-17A-deficient mice. IL-17A mRNA expression was increased in the spleens and kidneys of immunized mice after infection. CXCL2 and CCL2 mRNA expression was increased in the spleens and kidneys, respectively. Consistent with upregulation of the mRNA expression, neutrophils infiltrated into the spleens extensively and macrophage infiltration was observed in the kidneys of immunized mice. These results suggest that immunization with ClfA40-559 induces the IL-17A-producing cells and that IL-17-mediated cellular immunity is involved in the protective effect induced by immunization with ClfA40-559 against S. aureus infection.

Staphylococcus aureus has been known as a major nosocomial pathogen and to cause a variety of infections, ranging from superficial infections to more life-threatening diseases (18). Recently, infections caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus have been reported to be increasing in healthy children and young adults (40). Most of clinically isolated strains show antibiotic resistance, leaving few options for effective antimicrobial therapy. Effective treatment for and prevention strategies against S. aureus infection are urgently needed.

Various staphylococcal virulence factors have been identified as targets for novel therapeutics, including microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecule proteins (MSCRAMM) located on the surface of S. aureus. Clumping factor A (ClfA) is a fibrinogen-binding MSCRAMM and is expressed by virtually all S. aureus strains (15). ClfA is composed of 933 amino acids, and the structure of ClfA at the molecular level has been clarified (20, 21). Residues 40 to 559 compose region A, which contains the fibrinogen-binding domain. The biological roles of ClfA were also clarified in previous studies. ClfA promotes clumping of S. aureus in plasma and adherence of bacterial cells to blood clots and to plasma-conditioned biomaterials (21, 24, 36). These studies indicate that ClfA must be an important virulence factor of S. aureus in causing infections.

The potential of ClfA as a vaccine target has been shown. Mice vaccinated with a recombinant region A of ClfA (ClfA40-559) induced specific antibody production, and animals were protected against septic arthritis (15). In addition to active immunization, passive immunization with antibodies for ClfA40-559 also protected animals (2, 6, 15, 38). Aurexis (tefibazumab), a humanized monoclonal antibody, was shown to enhance opsonophagocytosis and to protect animals against infective endocarditis caused by S. aureus (2, 6).

Pathogen-activated antigen-presenting cells induce activation and differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into T helper (Th) cells, and the resultant cells play an important role in immune responses by exertion of a variety of effector functions. Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) produced by Th1 cells is involved in immune response to combat intracellular pathogens. Cytokines produced by Th2 cells are essential for the generation of antibodies to eliminate extracellular pathogens (32). Interleukin-17 (IL-17) is produced mainly by Th17 cells (7, 30). IL-17 regulates CXC and CC chemokine expression and several proinflammatory cytokines (4, 29, 30). Recent studies showed that IL-17 plays an important role in cell-mediated host defense, especially against extracellular bacterial infections (4, 29). The roles of specific cell-mediated responses in pathogenesis of staphylococcal diseases and host defense against S. aureus infection were previously reported. Delayed hypersensitivity to staphylococcal antigens developed in mice after repeated staphylococcal infections (3). S. aureus capsular polysaccharide activates T cells and induces production of IFN-γ, which potentiates pathogenesis of S. aureus (22). It was also reported that various T cell populations activated by vaccination are involved in adaptive host defense against S. aureus infection. Gómez et al. reported that the ratio of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells increased in mice immunized with an S. aureus mutant via an intramammary route and that IFN-γ plays an important role in the eradication of intracellular staphylococci (5). Lin et al. showed that vaccination with the recombinant N terminus of the candidal Als3p adhesin induced CD4+ lymphocyte-derived IL-17A, which is necessary for vaccine efficacy against S. aureus and Candida albicans (16).

In this study, we investigated the role of cytokines in the protective effect against S. aureus systemic infection in mice immunized with ClfA40-559. We demonstrate that immunization with ClfA40-559 induces IL-17A-producing cells and that IL-17A plays a role in the protective effect against systemic S. aureus infection in ClfA40-559-immunized mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

IL-17A gene-deficient mice of (129/Sv × C57BL/6)F1 hybrid background were backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice (25, 34), and C57BL/6 mice were used as their wild-type counterparts. BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Clea Japan, Tokyo, Japan. Five- to 8-week-old mice were used in this study. Mice were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the Institute for Animal Experimentation, Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine. Food and water were given ad libitum. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines for animal experimentation of Hirosaki University.

Construction of a plasmid encoding ClfA40-559 expression and purification of recombinant ClfA40-559 protein.

Genomic DNA was isolated from S. aureus strain Mu50 as described elsewhere (28). The ClfA40-559 gene was amplified by PCR using the following PCR primers and standard PCR amplification conditions: forward, 5′-CCCCGAATTCATGAATATGAAGAAAAAAGAAAAAC-3′, and reverse, 5′-CCCCGTCGACTTATTTCTTATCTTTATTTTC-3′. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and SalI and cloned into pGEX-6p-1, and the plasmids were used to transform Escherichia coli DH5α cells. The whole nucleotide sequence was determined with an ABI automatic DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). E. coli DH5α cells harboring the recombinant plasmids were grown in 2× YT medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin until the culture reached an optical density at 550 nm of 0.8 to 1.0. For the expression of ClfA40-559, isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. After a 5-h induction period, the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, and the bacterial pellets were resuspended in B-PER bacterial protein extraction reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Purification of the fusion proteins and removal of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag were performed by using bulk GST purification modules (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The concentrations of the resultant recombinant ClfA40-559 were determined with the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), and the protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The recombinant ClfA40-559 was confirmed to retain the function of native ClfA, i.e., binding to fibrinogen, by Western affinity blotting as described previously (39). Briefly, several doses of fibrinogen were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P transfer membrane (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA). After blocking, the membrane was incubated with ClfA40-559, followed by incubation with rabbit anti-ClfA40-559 antibody, and then horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) was added. Bound horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody was visualized using the ECL Western blotting system (GE Healthcare). The endotoxin content of the purified ClfA40-559 was determined by Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Cape Cod Inc., Falmouth, MA). The endotoxin concentration of ClfA40-559 was less than 8.6 pg/μg.

Bacterial strains and culture condition.

S. aureus strain 834, a clinical sepsis isolate (27), was used for infection of mice in this study. The bacteria were grown in tryptic soy broth (BD Diagnosis Systems, Sparks, MD) for 15 h, harvested by centrifugation, and washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The washed bacteria were diluted with PBS to appropriate cell concentrations as determined spectrophotometrically at 550 nm.

Immunization of mice and S. aureus infection.

For active immunization, purified ClfA40-559 was dissolved in PBS and emulsified 1:1 in alum adjuvant (Pierce). Mice were subcutaneously injected with 200 μl of the emulsion containing 10 μg of protein or with PBS plus adjuvant as a control on days 0, 14, and 28. For determination of survival rates, mice were injected with PBS plus adjuvant or PBS alone as controls. Booster immunization was performed at 14 and 28 days after the initial immunization. To determine the survival rates after S. aureus infection, BALB/c mice were infected with 5 × 107 CFU per mouse of S. aureus 834. IL-17A-deficient mice and their wild-type C57BL/6 mice were infected with 1 × 108 CFU per mouse by intravenous injection on day 7 after the last booster immunization. The survival rates of mice were monitored for 7 or 14 days after infection. To determine bacterial numbers, cytokine production, and mRNA expression in the organs, BALB/c mice, IL-17A-deficient mice, and their wild-type C57BL/6 mice were infected with S. aureus 834 at 5 × 107 CFU per mouse on day 7 after the last booster immunization. For passive immunization, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 10 mg or 0.3 mg of rabbit Ig fraction containing antibodies specific for ClfA40-559. Control mice were injected with 10 mg or 0.3 mg of normal rabbit globulin (NRG) in the same way. Mice were infected with S. aureus 834 at 5 × 107 CFU per mouse at 24 h after the passive immunization. Bacterial numbers in the organs were enumerated by preparing organ homogenates in PBS and plating 10-fold serial dilutions on tryptic soy agar (BD Diagnosis System). Colonies were counted after 24 h of incubation at 37°C.

Cell culture.

Spleens of naïve mice were aseptically removed. The spleens from immunized and control mice were taken on day 7 after the last booster immunization. Spleen cells were obtained by squeezing and filtering through stainless steel mesh (size, 100) in RPMI 1640 medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan). Erythrocytes were lysed with 0.85% NH4Cl. After being washed three times with RPMI 1640 medium, the cells were suspended at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS), 1% l-glutamine (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan), 100 U of penicillin G per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml in a 24-well culture plate. The spleen cells were incubated at 37°C with or without 10 μg/ml ClfA40-559. The supernatants were collected after 48 h of incubation, and the cells were collected after 4, 24, 48, or 72 h of incubation. The samples were stored at −80°C until further analyses were performed.

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Total RNAs from cultured cells and mouse organs were isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNAs were synthesized by reverse transcription of 1 μg total RNA using random primers (Takara, Shiga, Japan) and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The primers and cycling conditions are listed in Table 1. Gene expression levels were determined by real-time PCR analysis performed using the SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Dissociation curves were used to detect primer-dimer conformation and nonspecific amplification. The threshold cycle (CT) of each target product was determined and set in relation to the amplification plot of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The detection threshold was set to the log linear range of the amplification curve and kept constant (0.05) for all data analysis. The difference between the CT values (ΔCT) of two genes was used to calculate the relative expression; i.e., relative expression = 2−(CT of target gene − CT of GADPH) = 2−ΔCT.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of specific oligonucleotide primer pairs

| Gene | Primer | Sequence | PCR conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β | Forward | 5′-TATAGCAACAATTCCTGGCG-3′ | 29 s, 93°C; 29 s, 55°C; 120 s, 72°C |

| Reverse | 5′-TGCTGTCACAGGAGCAGTG-3′ | ||

| IL-6 | Forward | 5′-TGGAGTCACAGAAGGAGTGGCTAAG-3′ | 29 s, 93°C; 29 s, 55°C; 120 s, 72°C |

| Reverse | 5′-TCTGACCACAGTGAGGAATGTCCAC-3′ | ||

| IL-17A | Forward | 5′-GCTCCAGAAGGCCCTCAGA-3′ | 30 s, 94°C; 30 s, 60°C; 60 s, 72°C |

| Reverse | 5′-AGCTTTCCCTCCGCATTGA-3′ | ||

| IL-17F | Forward | 5′-CCCAGGGTCAGGAAGACA-3′ | 30 s, 94°C; 30 s, 55°C; 60 s, 72°C |

| Reverse | 5′-CCGAAGGACCAGGATTTCT-3′ | ||

| CXCL2 | Forward | 5′-GAACAAAGGCAAGGCTAACTGA-3′ | 60 s, 94°C; 120 s, 60°C; 180 s, 72°C |

| Reverse | 5′-AACATAACAACATCTGGGCAAT-3′ | ||

| CCL2 | Forward | 5′-ACTGAAGCCAGCTCTCTCTTCCTC-3′ | 60 s, 94°C; 120 s, 60°C; 180 s, 72°C |

| Reverse | 5′-TTCCTTCTTGGGGTCAGCACAGAC-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | Forward | 5′-TGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTGG-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-ACGACATACTCAGCACCAGCATCAC-3′ |

Cytokine assays.

The amounts of IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-12p70 in the supernatants of cell cultures were determined by double-sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) as described previously (26, 27, 33). The amounts of IL-6 and IL-17 in the supernatants were determined by ELISAs, using a mouse IL-6 Cytoset kit (Biosource USA, Camarillo, CA) and mouse IL-17 ELISA (Bender MedSystems GmbH, Vienna, Austria), respectively.

Assay of specific antibodies.

Serum samples were obtained from immunized and control mice at 7 days after the last booster immunization and diluted 2-fold with 10% Blockace (Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) in PBS. The titers of IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 antibodies against ClfA40-559 were determined by ELISAs as described previously (10). The titer of each antibody was defined as the highest dilution giving an absorbance value of more than twice that of control.

MPO assay.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) assay, an index of tissue neutrophil levels, was performed as described previously (14). Spleens were obtained from immunized or nonimmunized BALB/c mice on days 2 and 3 after S. aureus infection. Fifty milligrams of spleen sample was homogenized in 1 ml of potassium phosphate buffer (6.8 g of KH2PO4 and 8.7 g of K2HPO4 in 1 liter of water) containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo, Japan) for 30 s and vortexed for 15 s. The homogenate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 4 min, an aliquot of supernatant (7 μl) was added to a flat-bottomed 96-well plate, and 200 μl of potassium phosphate buffer containing 0.167 mg/ml o-dianisidine dihydrochloride and 0.0005% hydrogen peroxide was added immediately prior to reading the optical density at 450 nm and again 60 s later. One unit of MPO activity is defined as the degradation of 1 mmol of peroxide/min, which gives a change in absorbance of 1.13 × 10−2/min (8).

Histological and immunohistochemical analysis.

Spleen and kidney tissues were obtained at 2 and 3 days after S. aureus infection, fixed with 10% phosphate-buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Four-micrometer-thick sections were prepared. For immunohistochemistry, deparaffinized sections were immunostained using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) method with a Vectastain ABC kit (Vector, Burlingame, CA). The sections were incubated with rat anti-mouse neutrophil antibody Ly-6G (diluted 1:20; Hycult Biotechnology, Uden, Netherlands) or rat anti-mouse macrophage antibody F4/80 (diluted 1:100; Serotec Product, Oxford, United Kingdom) overnight at 4°C. The color reaction was developed by the addition of diaminobenzidine followed by counterstaining of sections with hematoxylin. Macrophage density was determined by counting the F4/80-positive cells in 10 random high-power (×400) fields of each section.

Statistical analysis.

Data for bacterial counts are presented as box plots. Boxes represent the interquartile range, and the whiskers indicate the range of all the data. The median value is represented by a line across each box. Data for antibody titers, cytokine production, and mRNA expression are expressed as medians ± interquartile range. Statistical analyses of bacterial counts in the organs, cytokine production, and relative expression of mRNA were done via the Mann-Whitney U test. For survival experiments, the Kaplan-Meier method was used to obtain survival fractions, and the significance was determined by a log rank test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Protective effect of immunization with ClfA40-559 against S. aureus infection.

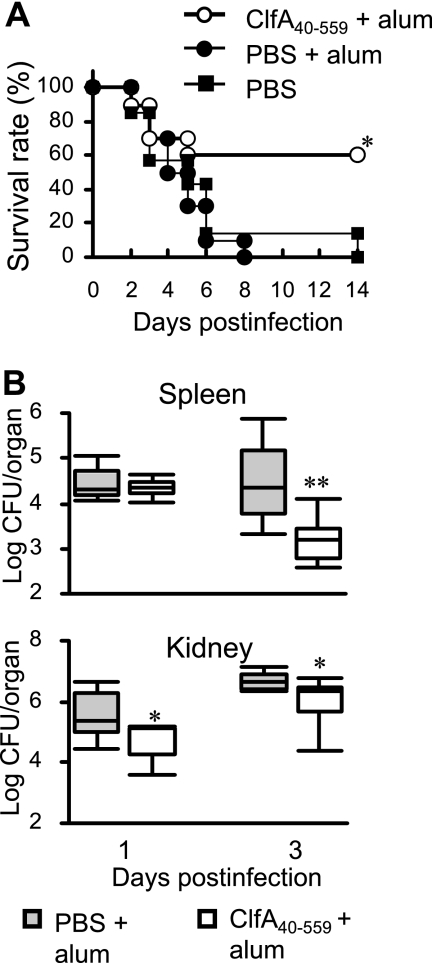

The protective effect against S. aureus infection was evaluated in BALB/c mice immunized with ClfA40-559 plus alum adjuvant. Controls were injected with antigen-free PBS and alum adjuvant or antigen-free PBS only. The immunized and control mice were infected with S. aureus at 7 days after the last booster immunization. Although most mice from both control groups died, 60% of the immunized mice survived (Fig. 1 A). Bacterial growth in the spleens and kidneys of immunized mice and the control animals injected with PBS plus alum adjuvant was determined at 1 and 3 days after S. aureus infection. The bacterial numbers in the spleens of immunized mice were reduced at 3 days after infection, while the elimination of bacteria from the kidneys of immunized mice was enhanced at 1 and 3 days after infection compared with that for the nonimmunized mice (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Protection against S. aureus infection by immunization with ClfA40-559. BALB/c mice were immunized with ClfA40-559 and alum adjuvant. Control mice were treated with antigen-free PBS and alum adjuvant or with antigen-free PBS only. Immunized and control BALB/c mice were infected with S. aureus. (A) Survival rates of both groups were observed for 14 days after infection. Each group of mice included 6 to 10 mice. An asterisk represents a statistically significant difference from the control group administered PBS plus alum (P < 0.05). (B) Bacterial numbers in the spleens and kidneys of immunized and control mice were determined at 1 and 3 days after infection. Data are presented as box plots, with the boxes representing the interquartile range. The median value is represented by the line across each box. An asterisk represents a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

Cytokine responses in spleen cells of mice immunized with ClfA40-559.

The molecules required for Th cell differentiation were evaluated in the spleen cells of naïve BALB/c mice. The naïve spleen cells were cultured with or without ClfA40-559, and cell culture supernatants were collected 48 h later. IL-6 was induced by stimulation with ClfA40-559 (Fig. 2 A). However, neither IL-12p70 production nor IL-4 production was induced (data not shown). To assess expression of transforming growth factor-β(TGF-β), total mRNA was extracted from spleen cells. TGF-β mRNA expression was significantly increased in the spleen cells of naïve mice at 4 h after stimulation (Fig. 2B). To investigate cytokine profiles in the spleen cells of mice immunized with ClfA40-559 and control BALB/c mice, cells from both groups were stimulated with or without ClfA40-559, and cytokine production in the spleen cell cultures and mRNA expression in the cells were assessed. IFN-γ production in the spleen cell culture supernatants was comparable in the immunized mice and nonimmunized mice (Fig. 2C). IL-4 was not detected in the spleen cell culture supernatants of either group (data not shown). Slight IL-17 production was observed in the cell cultures from control mice after stimulation with ClfA40-559. In contrast, IL-17 production in the cell cultures from immunized mice was significantly augmented by stimulation with ClfA40-559 (Fig. 2D). IL-17A mRNA expression was also evaluated. IL-17A mRNA expression was significantly increased in the spleen cells of immunized mice compared with the control mice (Fig. 2E). However, IL-17F mRNA expression was not different in the immunized and control mice (data not shown). These results suggested that IL-17A-producing cells were induced by immunization with ClfA40-559.

FIG. 2.

Cytokine responses in the spleen cells of naïve mice and mice immunized with ClfA40-559 after stimulation with ClfA40-559. Spleen cells of naïve BALB/c mice were incubated in the absence or presence of 10 μg/ml ClfA40-559. (A) IL-6 production in the spleen cell culture supernatants was determined at 48 h after stimulation. (B) The relative mRNA expression of TGF-β in the spleen cells was determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR at 4 h after stimulation. BALB/c mice were immunized with ClfA40-559 and alum adjuvant, and control mice were injected with antigen-free PBS and alum adjuvant. Spleen cells of both groups were taken at 7 days after the last booster immunization and incubated in the absence or presence of 10 μg/ml ClfA40-559 for 48 h. (C to E) IFN-γ (C) and IL-17 (D) titers in the cell culture supernatants were determined. Simultaneously, the relative mRNA expression of IL-17A was determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR after 4 h of incubation (E). Data are expressed as the medians ± interquartile range for a group of six to eight mice. ND, not detectable. An asterisk represents a statistically significant difference from the control group (P < 0.05).

Impairment of the protective effect of immunization with ClfA40-559 in IL-17-deficient mice.

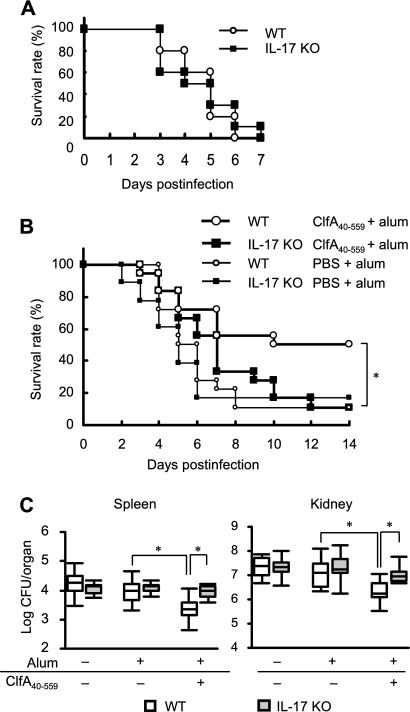

To investigate whether IL-17A is involved in the protective effect of immunization with ClfA40-559 against S. aureus infection, naïve IL-17A-deficient mice and their wild-type C57BL/6 mice were infected with S. aureus and survival was monitored. Survival rates of each group of mice were similar (Fig. 3 A). Next, IL-17A-deficient mice and their wild-type C57BL/6 mice were immunized with ClfA40-559 or injected with antigen-free PBS and alum adjuvant. These animals were infected with S. aureus, and survival was observed for 14 days. Although half of the immunized wild-type mice survived, the immunized IL-17A-deficient mice succumbed to infection, as did the control groups (Fig. 3B). Bacterial growth in the spleens and kidneys of wild-type mice and IL-17A-deficient mice was assessed at 3 days after S. aureus infection. Bacterial growth was inhibited in the organs of immunized wild-type mice, while bacterial numbers in the organs of immunized IL-17A-deficient mice were significantly higher than those in immunized wild-type mice (Fig. 3C). The bacterial numbers in the organs were comparable for the immunized and control IL-17A-deficient mice. These results suggested that IL-17A was required for acquired resistance induced by immunization with ClfA40-559 against S. aureus infection.

FIG. 3.

Survival rates of naïve IL-17A-deficient (IL-17A KO) mice and wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice. Both groups of mice were infected with S. aureus intravenously. (A) Survival rates were observed for 7 days after infection. Each result represents data for a group of 10 mice. Defective protection against S. aureus infection was observed in IL-17A-deficient mice immunized with ClfA40-559. IL-17A KO mice and WT mice were immunized with ClfA40-559 plus alum adjuvant or injected with antigen-free PBS and alum adjuvant. Both groups of mice were infected with S. aureus. (B) Survival rates were observed for 14 days after infection. Each result represents data for a group of 12 mice. (C) Bacterial numbers in the spleens and kidneys of immunized and control mice were determined at 3 days after infection. Each group included six to eight mice. Data are presented as box plots, with the boxes representing the interquartile range. The median value is represented by the line across each box. An asterisk represents a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

Antibody-mediated bacterial clearance in the organs of naïve mice.

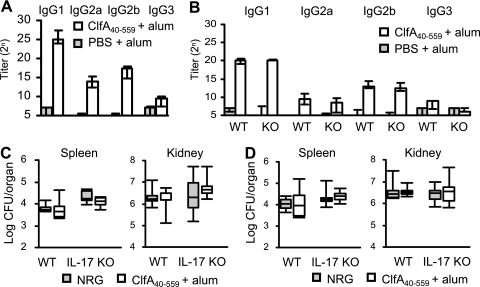

Anti-ClfA40-559 Ig subclasses were induced in the bloodstreams of ClfA40-559-immunized BALB/c mice (Fig. 4 A). It is possible that the impaired protection of IL-17A-deficient immunized mice may be due to insufficient antibody production. Serum samples were obtained from the immunized and control IL-17A-deficient and wild-type C57BL/6 mice. The titers of anti-ClfA40-559 IgG classes in the sera were elevated in both immunized IL-17A-deficient and wild-type C57BL/6 mice. There was no difference in antibody titers between the immunized groups (Fig. 4B). Next, the role of anti-ClfA40-559 antibody in protection was investigated by passive immunization. Naïve IL-17A-deficient and wild-type C57BL/6 mice were passively immunized with 10 mg or 0.3 mg of rabbit anti-ClfA40-559 antibody at 24 h before S. aureus infection, and bacterial numbers in the spleens and kidneys were determined at 3 days after infection. No effect of the passive immunization on bacterial clearance was shown in either IL-17A-deficient or wild-type mice (Fig. 4C and D). These results suggested that IL-17A is not involved in the induction of IgG subclasses against ClfA40-559 and that anti-ClfA40-559 antibody alone is insufficient to reduce the bacterial burden in the organs of mice actively immunized with ClfA40-559.

FIG. 4.

Antibody production by active immunization with ClfA40-559 and effect of passive immunization with anti-ClfA40-559 antibody. Mice were immunized with ClfA40-559 as described in Materials and Methods. Control mice were injected with antigen-free PBS and alum adjuvant. (A and B) Sera from immunized and control mice were collected at day 7 after the last booster immunization. Titers of anti-ClfA40-559 antibody in the sera of BALB/c mice (A) and IL-17A deficient (KO) mice and wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice (B) were determined by ELISA. Data are expressed as median ± interquartile range for a group of six to eight mice. (C and D) Bacterial numbers in the spleens and kidneys of mice passively immunized with 10 mg (C) or 0.3 mg (D) of anti-ClfA40-559 antibody were determined at 3 days after infection. Each group included six or seven mice. Data are presented as box plots, with the boxes representing the interquartile range. The median value is represented by the line across each box.

Effect of immunization with ClfA40-559 on inflammatory responses by S. aureus infection in the organs of mice.

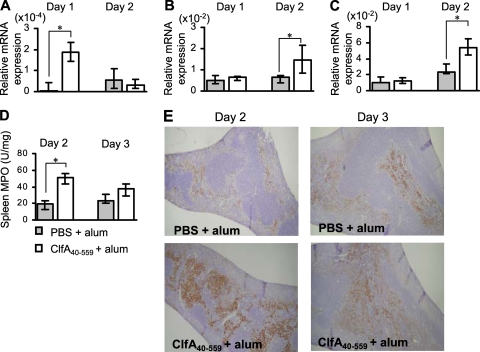

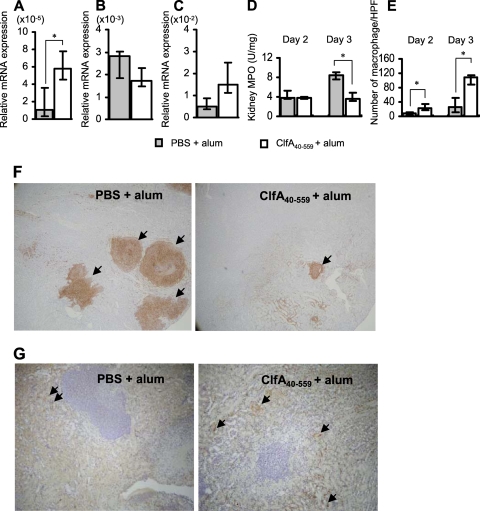

We next investigated mechanisms of IL-17A-mediated protection against S. aureus infection in the ClfA40-559-immunized BALB/c mice. Immunized and control mice were infected with S. aureus, and the spleens of mice were obtained at 1, 2, and 3 days after infection. IL-17A mRNA expression was significantly increased in the spleens of immunized but not control mice at 1 day after infection (Fig. 5 A). Both CXCL2 and IL-6 mRNA expression was significantly increased in the immunized mice compared with control mice at 2 days after infection (Fig. 5B and C). MPO activity and neutrophil infiltration in the spleens of immunized mice were increased and peaked at 2 days after infection (Fig. 5D and E). We also assessed the kidneys of immunized mice after S. aureus infection. IL-17A mRNA expression was enhanced in the kidneys of immunized mice at 1 day after infection (Fig. 6 A). In contrast to case for the spleens of immunized mice, CXCL2 mRNA expression and MPO activity in the kidneys of immunized mice were lower than those in control mice (Fig. 6B and D), while CCL2 mRNA expression was increased in immunized mice at 2 days after infection, (Fig. 6C). For histological analysis, kidneys of the immunized and control mice were obtained at 2 and 3 days after infection. Consistent with the results for MPO activity, extensive neutrophil infiltration and abscess formation occurred in the control mice (Fig. 6F). In contrast, macrophage infiltration was more prominent in the kidneys of the immunized mice than in those of control mice (Fig. 6E and G).

FIG. 5.

Inflammatory responses caused by S. aureus infection in the spleens of mice immunized with ClfA40-559. BALB/c mice were immunized with ClfA40-559 or injected with antigen-free PBS and alum adjuvant. Immunized and control BALB/c mice were infected with S. aureus. The spleens of mice were obtained at 1, 2, and 3 days after infection. (A to C) The mRNA expression of IL-17 (A), CXCL2 (B), and IL-6 (C) in the spleens was determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as the medians ± interquartile range for a group of five to seven mice. (D) MPO activity in the spleens of immunized and control mice was determined at 2 and 3 days after infection. Data are expressed as the medians ± interquartile range for a group of six mice. An asterisk represents a statistically significant difference from the control group (P < 0.05). (E) Histology of the spleens of immunized and nonimmunized mice was observed at 2 and 3 days after infection. Spleen sections were stained with antineutrophil antibody. Magnification, ×40.

FIG. 6.

Inflammatory responses in the kidneys of mice immunized with ClfA40-559. BALB/c mice were immunized with ClfA40-559 or injected with antigen-free PBS and alum adjuvant. Immunized and control BALB/c mice were infected with S. aureus. The kidneys of mice were obtained at 1, 2, and 3 days after S. aureus infection. (A to C) IL-17A mRNA expression (A) in the kidneys was determined at 1 day after infection, and the mRNA expression of CXCL2 (B) and CCL2 (C) was determined at 2 days after infection by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as the medians ± interquartile range for a group of six to seven mice. (D) MPO activities in the kidneys of immunized and control mice were determined at 2 and 3 days after infection. (E) Quantitative analysis of macrophages in the kidneys of the immunized and control mice was carried out. Macrophage density was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Each result represents the median ± interquartile range for 10 random fields of each section. An asterisk represents a statistically significant difference from the control (P < 0.05). (F and G) The histology of the kidney sections of immunized and control mice was observed 3 days after infection. The sections were stained with antineutrophil antibody Ly-6G (F) (magnification, ×40) or antimacrophage antibody F4/80 (G) (magnification, ×100). Arrows indicate F4/80-positive cells.

DISCUSSION

It was reported that active immunization with a domain of ClfA reduces the severity of Staphylococcus-mediated arthritis in mice (15). In this study, we confirmed the protective effect of an immunization with ClfA40-559 and alum adjuvant by evaluation of survival rates and bacterial counts in the organs of ClfA40-559-immunized and control BALB/c mice. The immunized mice were protected against sepsis-induced death (Fig. 1A). Because S. aureus is trapped in the spleen and colonizes in the kidney during systemic infection (27), we focused on the spleens and kidneys to evaluate the protective effect of immunization with ClfA40-559. Bacterial counts were reduced in the spleens and kidneys of the immunized mice (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that immunization with ClfA40-559 elicits the reduction of the bacterial burden in the organs of mice infected with S. aureus and that the effect should be involved in the protection by immunization against sepsis-induced death.

Previous studies have identified a significant role of T cells in regulating S. aureus pathogenesis and contributing to the host defense against S. aureus infection, showing the ability to produce cytokines and chemokines, which affect infiltration of phagocytes into infection sites (22). Hence, we considered that the cytokines produced by Th cells should play an important role in the protective effect of active immunization with ClfA40-559. To verify this, to begin with, we investigated cytokines, which are involved in differentiation of Th cells. IL-12 and IL-4 regulates Th1 and Th2 differentiation, respectively (30). IL-6 and TGF-β are reported to be required for differentiation of Th17 or IL-17-producing CD8+ cells (1, 17, 19). In this study, IL-6 production in spleen cell cultures and TGF-β mRNA expression in spleen cells obtained from naïve mice were induced by stimulation with ClfA40-559 (Fig. 2A and B). However, neither IL-12p70 nor IL-4 production was induced (data not shown). These results indicate that stimulation with ClfA40-559 induces IL-17-producing cells. Next, we assessed cytokine profiles produced by the spleen cells of ClfA40-559-immunized and control mice. There was no significant difference in the production of IFN-γ (Fig. 2C) and IL-4 (data not shown) between the immunized and control mice. Stimulation with ClfA40-559 slightly enhanced IL-17 production in the spleen cell cultures of control mice, but IL-17 production in those of ClfA40-559-immunized mice increased more than 5-fold compared with those of control mice (Fig. 2). Previous studies reported that the IL-17 family has six members, designated IL-17A to -F (4, 29). IL-17A and IL-17F play critical roles in protection against local S. aureus infection, and IL-17A and IL-17F complement each other in this setting (11). In this study, IL-17A mRNA expression was increased in the spleen cells of immunized mice after stimulation with ClfA40-559 (Fig. 2E), whereas IL-17F expression was comparable in the immunized and control mice (data not shown). These results suggest that IL-17A but not IL-17F production is enhanced by immunization with ClfA40-559.

The role of IL-17A in the protective efficacy of immunization with ClfA40-559 was investigated using wild-type and IL-17A-deficient mice. No significant difference in survival rates of naïve wild-type and IL-17A-deficient mice was shown (Fig. 3A). Bacterial counts in the spleens and kidneys of control wild-type mice were similar to those in control IL-17A-deficient mice at 3 days after S. aureus infection (Fig. 3C). These results are consistent with previous studies indicating that IL-17A-mediated responses may not be involved in innate immunity against S. aureus infection (11, 16). On the other hand, immunization with ClfA40-559 improved survival rates and reduced bacterial counts in the spleens and kidneys of wild-type mice significantly, whereas these protective effects were impaired in the immunized and control IL-17A-deficient mice (Fig. 3B and C). These results suggest that IL-17A plays an important role in the protective effect of immunization with ClfA40-559.

It was previously indicated that polyclonal anti-ClfA antibody plays an important role in the protective effect of active immunization with ClfA40-559 against the sepsis-induced death and septic arthritis caused by S. aureus, and passive immunization with antibodies for ClfA40-559 protected animals (6, 15, 38). In this study, immunization with ClfA40-559 induced significant titers of anti-ClfA40-559 IgG subclasses in both wild-type mice and IL-17A-deficient mice (Fig. 4B), although the protective effect was impaired in IL-17A-deficient mice compared with wild-type mice. Passive immunization with polyclonal ant-ClfA40-559 antibody failed to enhance the bacterial elimination in the spleens and kidneys of immunized wild-type and IL-17A-deficient mice (Fig. 4C and D). Recent studies reported the important role of phagocytes in protection against extracellular pathogens. Zhang et al. showed that mucosal colonization with Streptococcus pneumoniae induced IL-17A- and CD4+ T cell-dependent recruitment of phagocytes and that cellular immunity is required for clearance of pneumococci from the mucosal surface (43). Lin et al. reported that a vaccine-induced Th1/Th17 response resulted in recruitment into sites of infection and more effective clearance of S. aureus from tissues (16). From our data and these recent studies, it is possible that IL-17A-mediated cellular immunity rather than humoral immunity might play a more important role in the protective effect of immunization with ClfA40-559.

IL-17 regulates the production of cytokines and chemokines that are involved in neutrophil inflammation (4, 29, 30, 42). Neutrophils are crucial in the protective role against sepsis, septic arthritis, and dermatitis induced by S. aureus (23, 37). Previous studies reported that IL-17 is critical for optimal production of CXCL2 and plays a pivotal role in host defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae infection (42), IL-17 enhances neutrophil recruitment and contributes to lung defense against Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection (41), and IL-17A enhanced phagocyte recruitment and reduced bacterial counts of S. aureus in kidney (16). In the present study, IL-17A, CXCL2, and IL-6 mRNA expression was increased in the spleens of ClfA40-559-immunized mice (Fig. 5A, B, and C), and significant neutrophil infiltration was observed in the spleens of immunized but not control mice (Fig. 5D and E). These results suggest that IL-17A might enhance neutrophil recruitment and bacterial elimination in the spleens of ClfA40-559-immunized mice.

IL-17 was also reported to enhance the production of CCL2 by various kinds of cells, including proximal tubular epithelial cells and renal epithelial cells (9, 31, 35). Macrophages recruited by CCL2 play an important role in the host defense against extracellular bacterial infections, together with neutrophils. We demonstrated higher IL-17A mRNA expression and subsequent upregulated CCL2 mRNA expression in the kidneys of ClfA40-559-immunized mice (Fig. 6A and C). In contrast to the case for CCL2, CXCL2 mRNA expression was decreased in the kidneys of ClfA40-559-immunized mice compared with those of control mice (Fig. 6B). Neutrophils play an important role in host defense against S. aureus infection (23, 37), whereas an excessive recruitment of neutrophils causes an inflammatory response by release or generates potent cytotoxic mediators and bears the risk of additional tissue damage (12, 13). In accordance with CXCL2 mRNA expression, extensive neutrophil recruitment and large abscess formation were shown in the kidneys of control mice (Fig. 6F). In contrast, smaller abscesses and enhanced macrophage infiltration were observed in the kidneys of the immunized mice, along with upregulated CCL2 mRNA expression (Fig. 6G). These results suggest that IL-17A-mediated macrophage recruitment rather than neutrophil recruitment plays an important role in elimination of S. aureus in the kidneys of ClfA40-559-immunized mice.

The present study suggests that immunization with ClfA40-559 elicits IL-17A-dependent cell-mediated immunity to reduce the bacterial burden in the organs of immunized mice. These findings would be useful for development of an effective prophylactic strategy against infection caused by multidrug-resistant S. aureus.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (20390122 to A.N.) and by a grant for Hirosaki University Institutional Research.

We thank Naoki Tsujishima and Akie Kobayashi for their technical assistance.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 August 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bettelli, E., Y. Carrier, W. Gao, T. Korn, T. B. Strom, M. Oukka, H. L. Weiner, and V. K. Kuchroo. 2006. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 441:235-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domanski, P. J., P. R. Patel, A. S. Bayer, L. Zhang, A. E. Hall, P. J. Syribeys, E. L. Gorovits, D. Bryant, J. H. Vernachio, J. T. Hutchins, and J. M. Patti. 2005. Characterization of a humanized monoclonal antibody recognizing clumping factor A expressed by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 73:5229-5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Easmon, C. S., and A. A. Glynn. 1975. Cell-mediated immune responses in Staphylococcus aureus infections in mice. Immunology 29:75-85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaffen, S. L. 2008. An overview of IL-17 function and signaling. Cytokine 43:402-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez, M. I., D. O. Sordelli, F. R. Buzzola, and V. E. Garcia. 2002. Induction of cell-mediated immunity to Staphylococcus aureus in the mouse mammary gland by local immunization with a live attenuated mutant. Infect. Immun. 70:4254-4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall, A. E., P. J. Domanski, P. R. Patel, J. H. Vernachio, P. J. Syribeys, E. L. Gorovits, M. A. Johnson, J. M. Ross, J. T. Hutchins, and J. M. Patti. 2003. Characterization of a protective monoclonal antibody recognizing Staphylococcus aureus MSCRAMM protein clumping factor A. Infect. Immun. 71:6864-6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrington, L. E., R. D. Hatton, P. R. Mangan, H. Turner, T. L. Murphy, K. M. Murphy, and C. T. Weaver. 2005. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat. Immunol. 6:1123-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hobden, J. A., S. A. Masinick, R. P. Barrett, and L. D. Hazlett. 1997. Proinflammatory cytokine deficiency and pathogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis in aged mice. Infect. Immun. 65:2754-2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh, H. G., C. C. Loong, and C. Y. Lin. 2002. Interleukin-17 induces src/MAPK cascades activation in human renal epithelial cells. Cytokine 19:159-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu, D. L., K. Omoe, S. Sasaki, H. Sashinami, H. Sakuraba, Y. Yokomizo, K. Shinagawa, and A. Nakane. 2003. Vaccination with nontoxic mutant toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 protects against Staphylococcus aureus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 188:743-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishigame, H., S. Kakuta, T. Nagai, M. Kadoki, A. Nambu, Y. Komiyama, N. Fujikado, Y. Tanahashi, A. Akitsu, H. Kotaki, K. Sudo, S. Nakae, C. Sasakawa, and Y. Iwakura. 2009. Differential roles of interleukin-17A and -17F in host defense against mucoepithelial bacterial infection and allergic responses. Immunity 30:108-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaeschke, H. 2006. Mechanisms of liver injury. II. Mechanisms of neutrophil-induced liver cell injury during hepatic ischemia-reperfusion and other acute inflammatory conditions. Am. J. Physiol. 290:G1083-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaeschke, H., and C. W. Smith. 1997. Mechanisms of neutrophil-induced parenchymal cell injury. J. Leukoc. Biol. 61:647-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeyaseelan, S., H. W. Chu, S. K. Young, and G. S. Worthen. 2004. Transcriptional profiling of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Infect. Immun. 72:7247-7256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Josefsson, E., O. Hartford, L. O'Brien, J. M. Patti, and T. Foster. 2001. Protection against experimental Staphylococcus aureus arthritis by vaccination with clumping factor A, a novel virulence determinant. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1572-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin, L., A. S. Ibrahim, X. Xu, J. M. Farber, V. Avanesian, B. Baquir, Y. Fu, S. W. French, J. E. Edwards, Jr., and B. Spellberg. 2009. Th1-Th17 cells mediate protective adaptive immunity against Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans infection in mice. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu, S. J., J. P. Tsai, C. R. Shen, Y. P. Sher, C. L. Hsieh, Y. C. Yeh, A. H. Chou, S. R. Chang, K. N. Hsiao, F. W. Yu, and H. W. Chen. 2007. Induction of a distinct CD8 Tnc17 subset by transforming growth factor-β and interleukin-6. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82:354-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowy, F. D. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:520-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangan, P. R., L. E. Harrington, D. B. O'Quinn, W. S. Helms, D. C. Bullard, C. O. Elson, R. D. Hatton, S. M. Wahl, T. R. Schoeb, and C. T. Weaver. 2006. Transforming growth factor-β induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature 441:231-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDevitt, D., P. Francois, P. Vaudaux, and T. J. Foster. 1995. Identification of the ligand-binding domain of the surface-located fibrinogen receptor (clumping factor) of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 16:895-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDevitt, D., P. Francois, P. Vaudaux, and T. J. Foster. 1994. Molecular characterization of the clumping factor (fibrinogen receptor) of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 11:237-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLoughlin, R. M., J. C. Lee, D. L. Kasper, and A. O. Tzianabos. 2008. IFN-γ regulated chemokine production determines the outcome of Staphylococcus aureus infection. J. Immunol. 181:1323-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molne, L., M. Verdrengh, and A. Tarkowski. 2000. Role of neutrophil leukocytes in cutaneous infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 68:6162-6167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreillon, P., J. M. Entenza, P. Francioli, D. McDevitt, T. J. Foster, P. Francois, and P. Vaudaux. 1995. Role of Staphylococcus aureus coagulase and clumping factor in pathogenesis of experimental endocarditis. Infect. Immun. 63:4738-4743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakae, S., Y. Komiyama, A. Nambu, K. Sudo, M. Iwase, I. Homma, K. Sekikawa, M. Asano, and Y. Iwakura. 2002. Antigen-specific T cell sensitization is impaired in IL-17-deficient mice, causing suppression of allergic cellular and humoral responses. Immunity 17:375-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakane, A., S. Nishikawa, S. Sasaki, T. Miura, M. Asano, M. Kohanawa, K. Ishiwata, and T. Minagawa. 1996. Endogenous interleukin-4, but not interleukin-10, is involved in suppression of host resistance against Listeria monocytogenes infection in gamma interferon-depleted mice. Infect. Immun. 64:1252-1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakane, A., M. Okamoto, M. Asano, M. Kohanawa, and T. Minagawa. 1995. Endogenous gamma interferon, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin-6 in Staphylococcus aureus infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 63:1165-1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Omoe, K., M. Ishikawa, Y. Shimoda, D. L. Hu, S. Ueda, and K. Shinagawa. 2002. Detection of seg, seh, and sei genes in Staphylococcus aureus isolates and determination of the enterotoxin productivities of S. aureus isolates harboring seg, seh, or sei genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:857-862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouyang, W., J. K. Kolls, and Y. Zheng. 2008. The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity 28:454-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park, H., Z. Li, X. O. Yang, S. H. Chang, R. Nurieva, Y. H. Wang, Y. Wang, L. Hood, Z. Zhu, Q. Tian, and C. Dong. 2005. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat. Immunol. 6:1133-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu, Z., C. Dillen, J. Hu, H. Verbeke, S. Struyf, J. Van Damme, and G. Opdenakker. 2009. Interleukin-17 regulates chemokine and gelatinase B expression in fibroblasts to recruit both neutrophils and monocytes. Immunobiology 214:835-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reiner, S. L. 2007. Development in motion: helper T cells at work. Cell 129:33-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sashinami, H., A. Nakane, Y. Iwakura, and M. Sasaki. 2003. Effective induction of acquired resistance to Listeria monocytogenes by immunizing mice with in vivo-infected dendritic cells. Infect. Immun. 71:117-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umemura, M., A. Yahagi, S. Hamada, M. D. Begum, H. Watanabe, K. Kawakami, T. Suda, K. Sudo, S. Nakae, Y. Iwakura, and G. Matsuzaki. 2007. IL-17-mediated regulation of innate and acquired immune response against pulmonary Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin infection. J. Immunol. 178:3786-3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Kooten, C., J. G. Boonstra, M. E. Paape, F. Fossiez, J. Banchereau, S. Lebecque, J. A. Bruijn, J. W. De Fijter, L. A. Van Es, and M. R. Daha. 1998. Interleukin-17 activates human renal epithelial cells in vitro and is expressed during renal allograft rejection. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 9:1526-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaudaux, P. E., P. Francois, R. A. Proctor, D. McDevitt, T. J. Foster, R. M. Albrecht, D. P. Lew, H. Wabers, and S. L. Cooper. 1995. Use of adhesion-defective mutants of Staphylococcus aureus to define the role of specific plasma proteins in promoting bacterial adhesion to canine arteriovenous shunts. Infect. Immun. 63:585-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verdrengh, M., and A. Tarkowski. 1997. Role of neutrophils in experimental septicemia and septic arthritis induced by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 65:2517-2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vernachio, J., A. S. Bayer, T. Le, Y. L. Chai, B. Prater, A. Schneider, B. Ames, P. Syribeys, J. Robbins, and J. M. Patti. 2003. Anti-clumping factor A immunoglobulin reduces the duration of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in an experimental model of infective endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3400-3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wann, E. R., S. Gurusiddappa, and M. Hook. 2000. The fibronectin-binding MSCRAMM FnbpA of Staphylococcus aureus is a bifunctional protein that also binds to fibrinogen. J. Biol. Chem. 275:13863-13871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weber, J. T. 2005. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41(Suppl. 4):S269-S272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu, Q., R. J. Martin, J. G. Rino, R. Breed, R. M. Torres, and H. W. Chu. 2007. IL-23-dependent IL-17 production is essential in neutrophil recruitment and activity in mouse lung defense against respiratory Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Microbes Infect. 9:78-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye, P., F. H. Rodriguez, S. Kanaly, K. L. Stocking, J. Schurr, P. Schwarzenberger, P. Oliver, W. Huang, P. Zhang, J. Zhang, J. E. Shellito, G. J. Bagby, S. Nelson, K. Charrier, J. J. Peschon, and J. K. Kolls. 2001. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J. Exp. Med. 194:519-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang, Z., T. B. Clarke, and J. N. Weiser. 2009. Cellular effectors mediating Th17-dependent clearance of pneumococcal colonization in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119:1899-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]