Abstract

Mentha piperita essential oil was bactericidal in order of E. coli> S. aureus > Pseudomonas aeruginosa > S. faecalis > Klebsiella pneumoniae. The oil with total phenolics of 89.43 ± 0.58 µg GAE/mg had 63.82 ± 0.05% DPPH inhibition activity with an IC 50 = 3.9 µg/ml. Lipid peroxidation inhibition was comparable to BHT and BHA. A 127% hike was noted in serum ferric-reducing antioxidant power. There was 38.3% decrease in WBCs count, while platelet count showed increased levels of 214.12%. Significant decrease in uric acid level and cholesterol/HDL and LDL/HDL ratios were recorded. The volatile oil displayed high cytotoxic action toward the human tumor cell line. The results of this study deserve attention with regard to antioxidative and possible anti-neoplastic chemotherapy that form a basis for future research. The essential oil of mint may be exploited as a natural source of bioactive phytopchemicals bearing antimicrobial and antioxidant potentials that could be supplemented for both nutritional purposes and preservation of foods.

Keywords: Antioxidant, antibacterial, cytotoxicity, cancer, Mentha piperita

INTRODUCTION

Supplementation of human diet with herbs, containing especially high amounts of compounds capable of deactivating free radicals, besides the fruits and vegetables recommended as optimal sources of antioxidant activity, may have beneficial effects. The benefits resulting from the use of natural products rich in bioactive substances have promoted the growing interest of pharmaceutical, food and cosmetic industries as well as of individual consumers in the quality of herbal products. The oxidative deterioration of lipids is of great concern in the shelf life of foods. Lipid peroxidation leads to development of undesirable off-flavors and decreases the acceptability of foods. In addition, lipid oxidation decreases food safety and nutritional quality by the formation of potentially toxic products and secondary oxidation products during cooking or processing.[1] To prevent and retard lipid oxidation, synthetic antioxidants such as butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and propyl gallate (PG) have been added to lipid-containing foods.[2] However, potential health hazards of synthetic antioxidants in foods, including possible carcinogens, have been reported several times.[3] Antioxidants are compounds that can delay, inhibit, or prevent the oxidation of oxidizable matters by scavenging free radicals and diminishing oxidative stress. Plants contain a wide variety of antioxidant phytochemicals or bioactive molecules, which can neutralize the free radicals and thus retard the progress of many chronic diseases associated with oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS). The intake of natural antioxidants has been associated with reduced risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and diseases associated with ageing. Studies on dietary free radical scavenging molecules have attracted the attention to characterize phenolic compounds and other naturally occurring phytochemicals as antioxidants.[4] Spices and herbs are generally applied to food which is a nutrient rich environment for most bacteria. The antibacterial activity, however, could be also used in nutrient poor environments, for example, cleaning of food processing devices and depuration of shellfish.[5] A variety of molecules derived from spice possess bioactive properties. Spices are also considered as nutraceuticals in view of their nutritional, medicinal and therapeutical properties. In addition to improving flavor, certain spices and essential oils prolong the storage life of foods by an antimicrobial activity. Spices are primarily used in the food industry for improving the quality of the product. These powdered spices suffer disadvantages, e.g. quality variations from batch to batch caused by uneven distribution of flavor, loss of flavor strength, quality during storage, insect infestation, bacterial contamination, unhygienic nature and inconveniency in bulk handling. To overcome these problems, spice essential oil has come into use in the food industries.[6] Food-borne illness caused by consumption of contaminated foods with pathogenic bacteria and/or their toxins has been of great concern to public health. Controlling pathogenic microorganisms would reduce food-borne outbreaks and assure consumers a continuing safe, wholesome and nutritious food supply.[7,8] The exploration of naturally occurring antimicrobials for food preservation receives increasing attention due to consumer awareness of natural food products and a growing concern of microbial resistance toward conventional preservatives.[9] Bearing in mind the growing use of essential oils, their genotoxicity testing, identification of genotoxic compounds and attempts to improve their safety may be important fields of future research. Mentha piperita (Peppermint) is globally and widely used in the forms of oil, extract, leaves, and water. However, very little information is available on physiological, pharmacological and cytotoxic properties of Mentha piperita essential oil. Therefore, the present investigation was undertaken to evaluate the protective activity of bioactive phytochemicals from M. piperita essential oil.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Equipments and chemicals

The major equipments used were UV-2501PC spectrophotometer, ELISA reader and routine microbiology laboratory equipments. The essential oil was purchased from Zardband company, Tehran, Iran. Microbial and cell culture media and laboratory reagents were from Merck, Germany. Other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Microbial strain and growth media

E. coli (ATCC 25922), S. aureus (ATCC 25923), Streptococcus fecalis (PTCC 33186), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 8830) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 13883) were employed in the study. Bacterial suspensions were made in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth to a concentration of approximately 10 8 cfu/ml. Subsequent dilutions were made from the above suspension, which were then used in the tests.

Oil sterility test

To ensure sterility of the oils, geometric dilutions ranging from 0.036 to 72.0 mg/ml of the essential oil were prepared in a 96-well microtitre plate, including one growth control (BHI+DMSO) and one sterility control (BHI+DMSO+test oil). Plates were incubated under normal atmospheric conditions, at 37°C for 24 h. The contaminating bacterial growth, if at all, was indicated by the presence of a white ‘“pellet”’ on the well bottom.

Oil dilution solvent

5 µl of dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) loaded on sterile blank disks were placed on Mueller Hinton agar plates streaked with suspensions of bacterial strains, and were then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. There was no antibacterial activity on the plates and hence DMSO was selected as a safe diluting agent for the oil. 10 µl from each oil dilution was added to sterile blank discs. The solvent also served as control.

Disc diffusion method

The agar disc diffusion method was employed for the determination of antimicrobial activities of the essential oils in question. Briefly, 0.1 ml from 108 CFU/ml bacterial suspension was spread on the Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) plates. Filter paper discs (6 mm in diameter) were impregnated with 10 µl of the undiluted oil and were placed on the inoculated plates. These plates, after remaining at 4°C for 2h, were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The diameters of the inhibition zones were measured in millimeters. All tests were performed in triplicate.

Radical scavenging capacity of the oils

The hydrogen atom or electron donation abilities of the corresponding extracts and some pure compounds were measured from the bleaching of the purple-colored methanol solution of 2,20-diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH). 50 µl of 1:5 concentrations of the essential oil in methanol was added to 5 ml of a 0.004% methanol solution of DPPH. Trolox (1 mM) (Sigma-Aldrich), a stable antioxidant, was used as a synthetic reference. After a 30 min incubation period at room temperature, the absorbance was read against a blank at 517 nm. Inhibition of free radical by DPPH in percent (I%) was calculated in the following way:

I% = (Ablank — Asample/Ablank) × 100;

where Ablank is the absorbance of the control reaction (containing all reagents except the test compound), and Asample is the absorbance of the test compound. Tests were carried out in triplicate.

Lipid peroxidation (LPO) assay

Approximately 10 mg of ²-carotene (type I synthetic, Sigma–Aldrich) was dissolved in 10 ml of chloroform. The carotene-chloroform solution, 0.2 ml, was pipetted into a boiling flask containing 20 mg linoleic acid (Sigma–Aldrich) and 200 mg Tween 40 (Sigma– Aldrich). Chloroform was removed using a rotary evaporator at 40°C for 5 min and to the residue, 50 ml of distilled water was added, slowly with vigorous agitation, to form an emulsion. 5 ml of the emulsion was added to a tube containing 200 µl of essential oils solution and the absorbance was immediately measured at 470 nm against a blank, consisting of an emulsion without β-carotene. The tubes were placed in a water bath at 50°C and the oxidation of the emulsion was monitored spectrophotometrically by measuring absorbance at 470 nm over a 60 min period. Control samples contained 10 µl of water instead of essential oils. Butylated hydroxy anisole (BHA) and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), stable antioxidants, were used as synthetic references. The antioxidant activity was expressed as inhibition percentage with reference to the control after 60 minutes incubation using the following equation: AA = 100(DRC—DRS)/DRC,

where AA = antioxidant activity;

DRC = degradation rate of the control = [ln(a/b)/60];

DRS = degradation rate in the presence of the sample = [ln(a/b)/60];

a = absorbance at time 0;

b = absorbance at 60 min.

Total phenolic content assay

Total phenol content was estimated as gallic acid equivalents (GAE; µg gallic acid/mg extract) as described earlier.[10] In brief, a 100 µl aliquot of dissolved extract was transferred to a 10 ml volumetric flask, containing ca. 6.0 ml H2 O, to which was subsequently added 500 µl Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. After 1 min, 1.5 ml 200 g/l Na2CO3 was added and the volume was made up to 10 ml with H2O. After 2 h of incubation at 25°C, the absorbance was measured at 760 nm. Gallic acid (Sigma Co., 0.2-1 mg/ml gallic acid) was used as the standard for the calibration curve, and the total phenolic contents were expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents per gram of tested extracts (Y=0.001x +0.0079; r2 = 0.997).

Acute and subchronic toxicity

A 30-day oral toxicity study was conducted in Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus; 180–200 g) to determine the potential of C. cyminum essential oil to produce toxic effects. The rats of both sexes were housed in temperature-controlled rooms and were given food and water ad libitum until used. For the acute toxicity analysis, the essential oil was administered via oral gavage to the rats (n = 10 mice per group) at doses ranging from 100 to 2000 mg/kg/day. The results obtained were compared with those for the control animals [3% (v/v) Tween 80 in saline]. The LD50 was calculated by the probit method by using SPSS 7.0 for Windows. To investigate the subchronic toxicity of the essential oil, after 30 days of oral administration to rats, the hematological and serum biochemistry parameters were evaluated. Blood samples were collected by puncture in the infraorbital plexus. The blood samples collected on day 0 and day 30 were used for determining red cell and leucocyte counts and for hemoglobin, hematocrit and biochemical parameter analysis. The serum concentrations of urea, creatinine, glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase (GOT) and glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT) and other parameters were determined by using commercial kits. The values obtained were compared within and between the groups.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power of serum (FRAP)

The antioxidant power of blood serum was determined using FRAP assay.[11] Briefly, 50 µl of the blood serum (normal as well as experimental cells) suspension was added to 1.5 ml of freshly prepared and pre-warmed (37°C) FRAP reagent (300 mM acetate buffer, pH = 3.6, 10 mM TPTZ (tripyridyl-s-triazine) in 40 mM HCl and 20 mM FeCl3.6H2O in the ratio of 10:1:1) and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. The absorbance of the sample was read against reagent blank (1.5 ml FRAP reagent + 50 µl distilled water) at 593 nm. Aqueous solutions of known Fe(II) concentration (FeSO4.7H2O) were used for calibration of the FRAP assay and antioxidant power was expressed as µg/ml (y = 0.0025x+0.0005; r2 = 0.9976).

Cytotoxicity assay

The human cervical carcinoma Hela cell line NCBI code No. 115 (ATCC number CCL-2) were obtained from Pasteur Institute, Tehran-Iran. The cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% (w/v) glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cytotoxicity was measured using a modified MTT assay. This assay detects the reduction of MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] by mitochondrial dehydrogenase, to blue formazan product, which reflects the normal functioning of mitochondrial and cell viability.[12] Briefly, the cells (5 × 104) were seeded in each well containing 100µl of the RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS in a 96-well plate. After 24 h of adhesion, a serial of doubling dilution of the essential oil was added to triplicate wells over the range of 1.0–0.005 µl/ml. The final concentration of ethanol in the culture medium was maintained at 0.5% (volume/volume) to avoid toxicity of the solvent.[13] After 2 days, 10 µl of MTT (5 mg/ml stock solution) was added and the plates were incubated for an additional 4 h. The medium was discarded and the formazan blue, which formed in the cells, was dissolved with 100 µl dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO). The optical density was measured at 490 nm using a microplate ELISA reader. The cell survival curves were calculated from cells incubated in the presence of 0.5% ethanol. Cytotoxicity is expressed as the concentration of drug inhibiting cell growth by 50% (IC50), (y = 110.12x0.025; r2 = 0.9981). All tests and analyses were run in triplicate and mean values were recorded.

Statistical analysis

All the experimental data are presented as mean ± SEM of three individual samples. Data are presented as percentage of free radical scavenging/inhibition lipid peroxidation on different concentrations of cumin oil. IC50 (the concentration required to scavenge 50% of free radicals) value was calculated from the dose-response curves. Antibacterial effect was measured in terms of zone of inhibition to an accuracy of 0.1 mm and the effect was calculated as a mean of triplicate tests. All of the statistical analyses were performed with the level of significant difference between compared data sets being set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

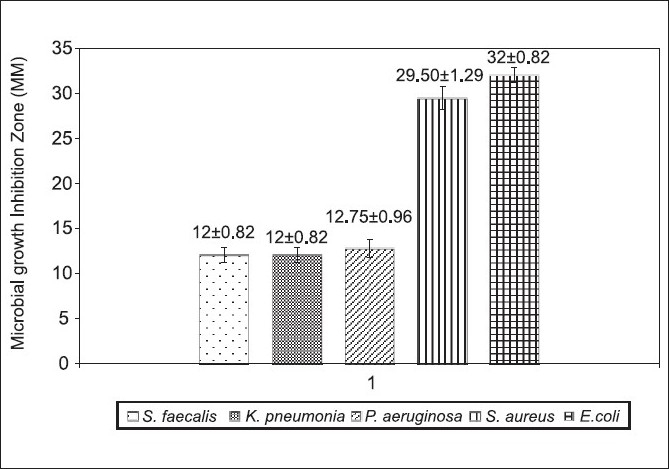

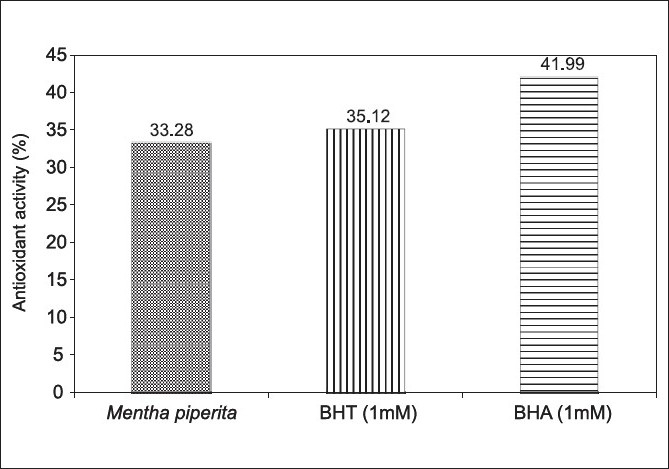

The antibacterial effect of Mentha piperita was tested against some bacteria by agar diffusion method. All the test organisms were sensitive to the oil with the sensitivity order of E.coli> S. aureus > Pseudomonas aeruginosa> S.faecalis > Klebsiella pneumoniae [Figure 1]. The antimicrobial activity of various essential oils including mint (Mentha piperita) was evaluated on survival and growth of different strains of E. coli O157:H7. The strains of E. coli exhibited similar susceptibilities to the action of the essential oils assayed at the inhibition zone diameter range of 16-19mm.[14] Addition of mint essential oil reduced the total viable counts of S. aureus about 6–7 logs.[15] Our results seem to be consistent with the above reports. Since essential oils consist of terpenes (phenolics in nature), it would seem reasonable that their mode of action might be related to those of other phenolic compounds.[15] Mentha extract (ME) has been reported to have antioxidant and antiperoxidant properties.[16] Hence we attempted to evaluate these properties with the essential oil under study. The oil showed at its maximum 63.82 ± 0.05% inhibition of DPPH activity with an IC50 = 3.9 µg/ml [Table 1]. The extracts of the M. piperita has shown 93.9 ± 1.68% inhibition of DPPH activity with an IC50 = 273 µg/ml.[17] In another study the essential oils of M. piperita had an IC50 = 2.53 µg/ml in the DPPH assay.[18] Total phenolics of M. piperita were 89.43 ± 0.58 µg GAE/mg [Table 1]. Plant phenols and flavonoids are known to inhibit lipid peroxidation by quenching lipid peroxy radicals and reduce or chelate iron in lipoxygenase enzyme and thus prevent initiation of lipid peroxidation reaction.[19] The antioxidant capacities of the essential oil as assessed by different assay methods are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2. Lipid peroxidation inhibition by M. Piperita oil was statistically (P>0.05) at the same level of the synthetic antioxidant BHT and lower (P<0.001) than BHA [Figure 2]. Many different methods have been established for evaluating the antioxidant capacity of certain biological samples, with such methods being classified, roughly, into one of two categories based upon the nature of the reaction that the method involved.[20] The methods involving an electron-transfer reaction include the total phenolics assay using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, the TEAC and the DPPH radical-scavenging assay. The radical scavenging effect of M. piperita essential oil was found to be 6.6 and 4.17 times more potent than the standard BHT and BHA respectively, but less potent (64%) than Trolox [Table 1]. This suggests that M. piperita essential oil is a good free radical scavenger or hydrogen donor and contributes significantly to the antioxidant capacity of M. piperita. The DPPH radical scavenging is a sensitive antioxidant assay and is independent of substrate polarity.[21] DPPH is a stable free radical that can accept an electron or hydrogen radical to become a stable diamagnetic molecule. A significant correlation was shown to exist between the phenolic content and with DPPH scavenging capacity for each spice.[22] Ferric-reducing antioxidant power in the blood sera of the rats gavaged with a daily dose of 100 µl oil showed 127% hike as compared to the control group [Table 2]. The antioxidant activity can be correlated to the moderate phenolic content of the oil. The phenolic content of certain spices appears to correlate well with such spices’ protective effect against peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration and lipid peroxidation. Such an observation indicates that phenolics present in the spices contributed to such spice-elicited protection against peroxynitrite toxicity.[22] There were some treatment-related effects in hematology parameters [Table 3]. Although the animals gained significant weight but the weight gain was statistically (P=0.1) insignificant. There was 38.3% decrease in WBCs count, while platelet count showed increased levels of 214.125% [Table 3]. Clinical chemistry parameters showed significant decrease in uric acid level while total cholesterol and triglycerides levels increased significantly. The interesting observations were of increased good cholesterol (HDL) level that reduced cholesterol/HDL and LDL/HDL ratios to 80% and 45.93% respectively. Thus, M. piperita with a high phenolic content and good antioxidant activity can be supplemented for both nutritional purposes and preservation of foods. Recently Dragland et al.[23] speculated that the daily intake of 1 g of various potent antioxidant spices makes a relevant contribution to the total intake of antioxidants in a normal diet. Peppermint oil was minimally toxic in acute oral studies. Short-term and subchronic oral studies reported cyst-like lesions in the cerebellum in rats that were given doses of peppermint oil containing pulegone, pulegone alone, or large amounts (>200 mg/kg/day) of menthone. With the limitation that the concentration of pulegone in these ingredients should not exceed 1%, it was concluded that Mentha piperita (peppermint) oil, Mentha piperita (peppermint) extract, Mentha piperita (peppermint) leaves, Mentha piperita (peppermint) water are safe as used in cosmetic formulations.[24] At a concentration of 0.02 µl/ml, oil destructed Hela cells by 98.48% [Table 4]. At lower doses, the oil was still toxic to the cells. The volatile oil displayed an excellent cytotoxic action toward the human tumor cell line. The IC50 was calculated to be 1×10-16 which seem to be indicative of high toxicity of the oil that needs testing with normal healthy cells in order to rule out its hazardous cytotoxicity before it is recommended for use. The oral administration of Mentha piperita extract (ME) showed a significant reduction in the number of lung tumors from an incidence of 67.92% in animals given only benzo[a]pyrene (BP) to 26.31%. Cancer chemoprevention is defined as the use of chemicals or dietary components to block, inhibit, or reverse the development of cancer in normal or preneoplastic tissue. A large number of potential chemopreventive agents have been identified, and they function by mechanisms directed at all major stages of carcinogenesis.[25] Essential oil constituents have a very different mode of action in bacterial and eukaryotic cells. For bacterial cells they are having strong bactericidal properties, while in eukaryotes they modify apoptosis and differentiation, interfere with the post-translational modification of cellular proteins, induce or inhibit some hepatic detoxifying enzymes. So, essential oils may induce very different effects in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Peppermint essential oil was reported to be cytotoxic.[26] Thus, peppermint essential oil may be classified as “high toxicity clastogen”,[27] which induces chromosome aberrations by secondary mechanism associated with cytotoxicity. It was suggested[28] that such compounds do not react with DNA and are not genotoxic in vivo and usually not carcinogenic. Some reports support the relationship of cytotoxicity with antioxidant activity.[29] Although all in vitro experiments hold limitations with regard to possible in vivo efficacy, the results of this study deserve attention with regard to antioxidative and possible anti-neoplastic chemotherapy that form a basis for future research. Even though essential oils might not be ideal for the treatment of human cancers, the oil tested certainly deserves some further investigation.

Figure 1.

Antimicrobial activity of Mentha piperita essential oil

Table 1.

Total phenolics and mean inhibition of DPPH free radical (%) by Mentha piperita essential oil dilutions

| Oil (µg/ml) and synthetic antioxidants | DPPH inhibition (%) | GAE µg Gallic acid/mg sample |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 63.82 ± 0.05 | 89.43 ± 0.58 |

| 5 | 55.85 ± 0.09 | 40.43 ± 0.58 |

| 2.5 | 42.77 ± 0.09 | 15.10 ± 1 |

| 0.2 | 26.50 ± 0.45 | 9.43 ± 0.58 |

| BHT 1mM | 9.63 | — |

| BHA 1mM | 15.28 | — |

| Trolox 1mM | 99.62 | — |

Table 2.

Blood serum Ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) of Mentha piperita essential oil

| Serum FRAP | FeSO4.7H2O equivalent (µg/ml) | Test/control ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 226.25 ± 5.84 | 100 |

| Mentha piperita | 287.4 ± 4.46 | 127 |

Figure 2.

Lipid peroxidation activity of Mentha piperita essential oil

Table 3.

Mean hematology and clinical chemistry values of rats blood samples fed with Mentha piperita essential oil

| Parameters | Control | Mean value (test) | % change | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial body weight (g) | 142.50±2.9 | 159±3.61 | 111.58 | 0.001 |

| Final body weight (g) | 157.50±5 | 198.33±18.93 | 125.93 | 0.008 |

| Weight gain (%) | 110.53±2 | 124.95±14.73 | 114.42 | 0.106 |

| Erythrocyte count (RBC) (×106/IL) | 7.23±1.25 | 7.90±0.59 | 109.39 | 0.430 |

| Total white blood cell (WBC) and differential | 9400+668 | 5800±608 | 61.7 | 0.0008 |

| leukocyte count (×103/μl) | ||||

| Hemoglobin concentration (HGB) (g/dl) | 12.78±1.4 | 13.53±0.51 | 105.94 | 0.434 |

| Hematocrit (HCT) (%) | 39.63±1.7 | 38.5±0.60 | 97.16 | 0.338 |

| Platelet count (PLT) (×103/μl) | 238500±1658 | 510666.67±5401.34 | 214.12 | 0.0002 |

| Red cell distribution width [RDW (%)] | 14.75±2.14 | 13.97±1.29 | 94.69 | 0.602 |

| Mean platelet volume (MPV) | 7.600.56 | 7.07±0.45 | 92.98 | 0.236 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) (fL) | 52.93±3.84 | 50.6±4 | 95.61 | 0.471 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) (pg) | 17.78±1.37 | 17.33±0.71 | 97.52 | 0.638 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration | 33.75±1.95 | 35.47±0.81 | 105.09 | 0.217 |

| [MCHC (g/dl)] | ||||

| Fasting glucose (GLUC) (mg/dl) | 221±7.79 | 218.33±15.18 | 98.79 | 0.77 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (mg/dl) | 60±5.96 | 55.23±5.25 | 92.06 | 0.322 |

| Blood creatinine (CREA) (mg/dl) | 0.64±0.1 | 0.63±0.10 | 99.21 | 0.95 |

| Uric acid | 8.18±2.45 | 4.29±0.85 | 52.44 | 0.049 |

| Total cholesterol(CHOL) (mg/dl) | 75.75±1 | 91±1 | 120.13 | 0.0000 |

| Triglycerides (TRIG) (mg/dl) | 45±9.2 | 73±8.19 | 162.22 | 0.009 |

| HDL | 45.50±4 | 67.30±0.72 | 147.91 | 0.0003 |

| LDL | 15.05±1.9 | 10.20±1.71 | 67.77 | 0.018 |

| Cholesterol/HDL ratio | 1.68±0.16 | 1.35±0.03 | 80.71 | 0.021 |

| LDL/HDL ratio | 0.33±0.03 | 0.15±0.03 | 45.93 | 0.0003 |

| SGOT | 530.75±68 | 520.67±69.41 | 98.10 | 0.855 |

| SGPT | 236.75±9 | 146.33±16.5 | 61.81 | 0.031 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALKP) (U/L) | 136.75±3 | 244.67±84.79 | 178.92 | 0.063 |

Table 4.

Cytotoxicity assay of Mentha piperita essential oil

| Oil (µl/ml) | Mean Viable cells | % Death |

|---|---|---|

| 0.02 | 1.52 ± 0.5 | 98.48 |

| 0.01 | 2.17 ± 0.67 | 97.83 |

| 0.0075 | 2.99 ± 0.75 | 97.01 |

| 0.005 | 3.89 ± 0.32 | 96.11 |

| 0.0025 | 5.48 ± 0.84 | 94.52 |

| 0.00125 | 7.36 ± 0.66 | 92.64 |

CONCLUSION

From the above results, it can be concluded that the tested essential oil exhibited antimicrobial activity against the tested microorganisms and it could be a better natural antioxidant. The essential oil provided comparable antioxidative activity as compared with synthetic antioxidants, which provides a way of screening antioxidants for foods, cosmetics and medicine. Hence, the essential oil of mint may be exploited as a natural source of bioactive phytopchemicals bearing antimicrobial and antioxidant potentials.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Medicinal Plants Research Centre of Shahed University (Tehran-Iran) for the sanction of research grants to conduct the present study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Maillard MN, Soum MH, Boivin P, Berset C. Antioxidant activity of barley and malt: relationship with phenolic content. Lebenson Wiss Technol. 1996;29:238–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winata A, Lorenz K. Antioxidant potential of 5-n-pentadecylresorcinol. J Food Process Preserv. 1996;20:417–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hettiarachchy NS. Natural Antioxidant Extract from Fenugreek (Trigonella foenumgraecum) for Ground Beef Patties. J Food Sci. 1996;61:516–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ani V, Varadaraj MC, Naidu KA. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of polyphenolic compounds from bitter cumin (Cuminum nigrum L.) Eur Food Res Technol. 2006;224:109–15. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birkenhauer JM, Oliver JD. Use of diacetyl to reduce the load of Vibrio vulnificus in the eastern Oyster, Crassostrea virginica. J Food Prot. 2003;66:38–43. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-66.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milan KS, Dholakia H, Tiku PK, Vishveshwaraiah P. Enhancement of digestive enzymatic activity by cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) and role of spent cumin as a bionutrient. Food Chem. 2008;110:678–83. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grohs BM, Kunz B. Use of spice mixtures for the stabilisation of fresh portioned pork. Food Control. 2000;11:433–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karanika MS, Komaitis M, Aggelis G. Effect of aqueous extracts of some plants of Lamiaceae family on the growth of Yarrowia lipolytica. Int J Food Microbiol. 2001;64:175–81. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(00)00468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuenzel KM, Harrison MA. Microbial antagonists of foodborne pathogens on fresh, minimally processed vegetables. J Food Prot. 2002;65:1909–15. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-65.12.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventos RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. In: Packer L, editor. Methods in Enzymology. Vol 299. San Diego: Academic Press Inc; 1999. pp. 152–78. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benzie IF, Strain JJ. [2] Ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay: Direct measure of total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous measurement of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid concentration. In: Lester P, editor. Methods in Enzymology Oxidants and Antioxidants Part A. Vol 299. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. p. 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau CB, Ho CY, Kim CF, Leung KN, Fung KP, Tse TF, et al. Cytotoxic activities of Coriolus versicolor (Yunzhi) extract on human leukemia and lymphoma cells by induction of apoptosis. Life Sci. 2004;75:797–808. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sylvestre M, Legault J, Dufour D, Pichette A. Chemical composition and anticancer activity of leaf essential oil of Myrica gale L. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreira MR, Ponce AG, del Valle CE, Roura SI. Inhibitory parameters of essential oils to reduce a foodborne pathogen. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 2005;38:565–70. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tassou C, Koutsoumanis K, Nychas GJ. Inhibition of Salmonella enteritidis and Staphylococcus aureus in nutrient broth by mint essential oil. Food Res Intl. 2000;33:273–80. [Google Scholar]

- 16.al-Sereiti MR, Abu-Amer KM, Sen P. Pharmacology of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis Linn.) and its therapeutic potentials. Indian J Exp Biol. 1999;37:124–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samarth RM, Panwar M, Kumar M, Soni A, Kumar M, Kumar A. Evaluation of antioxidant and radical-scavenging activities of certain radioprotective plant extracts. Food Chem. 2008;106:868–73. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mimica-Dukić N, Bozin B, Soković M, Mihajlović B, Matavulj M. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of three Mentha species essential oils. Planta Med. 2003;69:413–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torel J, Cillard J, Cillard P. Antioxidant activity of flavonoids and reactivity with peroxy radical. Phytochem. 1986;25:383–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang D, Ou B, Prior RL. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:1841–56. doi: 10.1021/jf030723c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaguchi T, Takamura H, Matoba T, Terao J. HPLC method for evaluation of the free radical-scavenging activity of foods by using 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1998;62:1201–4. doi: 10.1271/bbb.62.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho SC, Tsai TH, Tsai PJ, Lin CC. Protective capacities of certain spices against peroxynitrite-mediated biomolecular damage. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:920–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dragland S, Senoo H, Wake K, Holte K, Blomhoff R. Several culinary and medicinal herbs are important sources of dietary antioxidants. J Nutr. 2003;133:1286–90. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair B. Final report on the safety assessment of Mentha piperita (Peppermint) Oil, Mentha piperita (Peppermint) Leaf Extract, Mentha piperita (Peppermint) Leaf, and Mentha piperita (Peppermint) Leaf Water. Int J Toxicol. 2001;20:61–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samarth RM, Panwar M, Kumar M, Kumar A. Protective effects of Mentha piperita Linn on benzo[a]pyrene-induced lung carcinogenicity and mutagenicity in Swiss albino mice. Mutagenesis. 2006;21:61–6. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gei075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lazutka JR, Mierauskiene J, Slapsyte G, Dedonyte V. Genotoxicity of dill (Anethum graveolens L.), peppermint (Menthaxpiperita L and pine (Pinus sylvestris L) essential oils in human lymphocytes and Drosophila melanogaster. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39:485–92. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirkland D. Chromosome aberration testing in genetic toxicology - Past, present and future. Mutat Res. 1998;404:173–85. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galloway SM. Cytotoxicity and chromosome aberrations in vitro: Experience in industry and the case for an upper limit on toxicity in the aberration assay. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2000;35:191–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou J, Sun T, Hu J, Chen S, Cai X, Zou G. Chemical composition, cytotoxic and antioxidant activity of the leaf essential oil of Photinia serrulata. Food Chem. 2007;103:355–8. [Google Scholar]