Abstract

DNA can self-assemble in vitro into several liquid crystalline phases at high concentrations. The largest known genomes are encoded by the cholesteric liquid crystalline chromosomes (LCCs) of the dinoflagellates, a diverse group of protists related to the malarial parasites. Very little is known about how the liquid crystalline packaging strategy is employed to organize these genomes, the largest among living eukaryotes—up to 80 times the size of the human genome. Comparative measurements using a semiautomatic polarizing microscope demonstrated that there is a large variation in the birefringence, an optical property of anisotropic materials, of the chromosomes from different dinoflagellate species, despite their apparently similar ultrastructural patterns of bands and arches. There is a large variation in the chromosomal arrangements in the nuclei and individual karyotypes. Our data suggest that both macroscopic and ultrastructural arrangements affect the apparent birefringence of the liquid crystalline chromosomes. Positive correlations are demonstrated for the first time between the level of absolute retardance and both the DNA content and the observed helical pitch measured from transmission electron microscopy (TEM) photomicrographs. Experiments that induced disassembly of the chromosomes revealed multiple orders of organization in the dinoflagellate chromosomes. With the low protein-to-DNA ratio, we propose that a highly regulated use of entropy-driven force must be involved in the assembly of these LCCs. Knowledge of the mechanism of packaging and arranging these largest known DNAs into different shapes and different formats in the nuclei would be of great value in the use of DNA as nanostructural material.

DNA molecules are the indispensable genetic material of every organism. Apart from having the encoding power of a 4-base double-stranded polymer, DNA also has an enormous capacity to be condensed. It is probably this ability that allowed the evolution of increasing genome sizes in the eukaryotes. Histone-mediated nucleosome-based chromatin is the prevailing method for DNA packaging, but it is not the only way that DNA is condensed in the eukaryotes. Highly compact liquid crystalline DNA has been reported in several animal sperm nuclei (11, 28) and was also found in the nucleosomeless liquid crystalline chromosomes (LCCs) of dinoflagellates. Neither animal sperm nuclei nor dinoflagellate nuclei employ histones. In fact, the histone core octamer may hinder the attainment of ultrahigh levels of condensation due to its restrictive volume. In the sperm model, protamine is a sperm-specific DNA-binding protein (∼7 kDa) that is an order of magnitude smaller than the histone core octamer, and it adopts a structural role in the organization of the male gametic genome (1, 3). It is this very reduction in the protein-to-DNA ratio that may well enable the high DNA compaction into a liquid crystalline state. The dinoflagellate chromosomes are known to have a protein-to-DNA ratio even smaller than those of the prokaryotes (24). The typical eukaryotic genome has a protein/DNA ratio of 1:1, whereas the dinoflagellate genome has a ratio of 1:10 (23, 24).

The dinoflagellates, counterintuitively, have the largest known genomes among all living organisms, with a DNA content per genome ranging from 1.5 pg to 200 pg per haploid cell (19, 25, 43). An extraordinarily high level of DNA condensation must be attained in order to sequester these genomes within the bounds of the nucleus, and this is achieved through the form of LCCs. The concentration of the DNA in the dinoflagellate nucleus was estimated to be ∼200 mg ml−1 (up to 80 times more than a human cell) (24), falling well within the range observed for in vitro cholesteric liquid crystalline DNA formation (40). By observing ultrathin sections of dinoflagellate chromosomes using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM), plectonemic structures with nested series of arches and bands were seen (8, 12, 39). This architecture resembles the molecular architecture of thin-section TEM in vitro cholesteric liquid crystals (12, 39, 43).

Knowledge of the condensation process would not only be of interest in terms of eukaryotic genome packaging, but would also provide new insights for the use of DNA as building blocks for nanotechnology applications. Self-assembly is increasingly understood to be of great significance in the regulation of various macromolecules in the crowded environment of living cells (7, 15, 16, 35, 36). Interestingly, it was also recently reported that nucleosomes and polynucleosomes themselves can be self-assembled (17), and in liquid crystalline form (33). The formation of LCCs probably also relies upon the associated chromosomal proteins, while self-assembly of DNA molecules via neutralization of the negatively charged polyelectrolytes by counterions and the crowding effects within the permanently closed nucleus must also contribute significantly (36, 49, 50). Most of the previous studies of dinoflagellate LCCs were focused on the chromosomes of Prorocentrum micans (27, 29). Though it has been reported that not all dinoflagellate chromosomes show the same degree of birefringence (5), the relationships of different species and their DNA contents, densities, or compaction ratios to birefringence have not been reported.

The presence of two indices of refraction and optical anisotropy confer on the liquid crystalline DNA the property of birefringence, or double retardance. This optical phenomenon describes the phase differences between the two resultant light rays of a given light path that pass through the liquid crystal according to its refractive indices. For any given anisotropic material, the birefringence is a direct result of its nanoarchitecture. The property of birefringence and polarizing microscopy have long been employed to study the submicroscopic molecular organizations of different biological samples, such as mitotic spindles (5), filamentous actins (22), and microtubules (38), in living cells. Polarizing microscopy also allows the documentation of dynamic cellular behavior and measurements of cellular structures to be performed in a repeated noninvasive manner, even over extended periods of time (22). Taking advantage of this, we used a recently developed automatic rotating polarizing light microscope (the Metripol system) to study the relative amounts of birefringence and the ultrastructures of the chromosomes in several dinoflagellate species. Highly diverse chromosome structures were observed among the species, and surprisingly, not all dinoflagellates exhibited birefringent chromosomes, even though they are apparently constructed with similar liquid crystalline architectures, as seen in TEM ultrathin sections. The use of a semiautomatic Metripol polarizing microscope allowed the quantification of the retardance (20, 21, 47) of individual chromosomes of different dinoflagellate species in a fixative-free environment, and the relationships between the absolute retardance, DNA content, DNA condensation, and chromosome architecture in the dinoflagellate chromosomes are established in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture strains.

Crypthecodinium cohnii strain Biecheler 1649 was obtained from the Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Texas at Austin, maintained in MLH liquid medium (44), and incubated at 28°C in the dark. Alexandrium tamarense (Whedon et Kofoid) Balech (CCMP 1598), Karenia brevis (Davis) Hansen et Moestrup (CCMP 2281), P. micans (CCMP 689), Heterocapsa triquetra Stein (CCMP 449), Symbiodinium microadriaticum (CCMP 830), Karlodinium micrum (CCMP 1975), and Lingulodinium polyedrum (CCMP 1931) were obtained from the Provasoli-Guillard National Center for Culture of Marine Phytoplankton (CCMP). A. tamarense, K. brevis, and P. micans were maintained in L1 medium (14), while H. triquetra was maintained in f/2 medium (14). All of the cultures were grown at 18°C under a daily cycle of 12 h light and 12 h darkness. Amphidinium carterae strain Hulburt 37.80 was obtained from the Culture Collection of Algae (SAG) from the University of Göttingen and maintained in f/2 medium (14) at 18°C under a daily cycle of 12 h light and 12 h darkness.

Metripol system.

The Metripol system (Oxford Cryosystems) consists of an automatic motorized rotating polarizer and a highly light-sensitive charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera. A series of images (5, 10, or 50) are captured under 550-nm monochromatic light between a motorized rotating polarizer and a fixed circular analyzer. The series of images (5, 10, or 50) capture transmitted-light data for every 72°, 36°, or 7.2° of polarizer rotation, respectively. The intensity of this transmitted light for each polarizing angle (α) is captured by the CCD camera. The bundled software then analyzes the data from the multiple images and returns three separate composite false-color images displaying the nonperturbed light intensity (I0), the orientation of extinction (φ), and the absolute sine value of phase retardation |Sinδ| (21, 48). An interference filter (λ = 550 nm) was used throughout all the experiments. The Metripol rotating-polarizer method has two distinct advantages over the classical crossed-polarizing microscope. First, it employs an extremely light-sensitive CCD camera, which is able to visually enhance very small differences in |Sinδ| after compensating for the transmitted-light intensity (I0). Second, it also compensates for the orientation of extinction (φ) of any birefringent structures in the |Sinδ| false-color image. Images were obtained using Ach 100× (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) objectives with a 1.4-numerical-aperture (NA) Aplanat achromat condenser. The Metripol images from which we gathered our data were the |Sinδ| false-color images. These images use a light pink color to represent the baseline zero retardance (isotropic) and a progressively more intense purple color to represent ever more birefringent structures (anisotropic). The bundled software is able to extract a |Sinδ| value for any given point within the captured frame, as well as being able to extract a value for a transect or an area within the image frame. These were the values that we used for comparison of birefringence between species.

Data acquisition for retardance, volume, and value of half the helical pitch.

The values of |Sinδ| (absolute retardance) obtained from the Metripol software were used to estimate the true retardance of the chromosomes, after correcting for the chromosome thickness. Data acquisition for each species was performed using 10-step Metripol photomicrographs and acquired under ×100 magnifications. Average values of |Sinδ| along the chromosome long axis were obtained using the “line” mode analysis tool of the Metripol software, corresponding to a transect length of 1 μm. For those chromosomes that did not show any obvious retardance, |Sinδ| values were obtained by using the “area” mode tool (5 μm by 5 μm) of the Metripol software. More than 100 chromosomes for each species were measured in determining the values of |Sinδ|.

Assuming that a given dinoflagellate chromosome has a perfect rod shape with spherical ends, then the volume for that chromosome is arrived at by the following formula: 4πr2/3 + πr2(l − 2r), where r is the radius of the chromosome and l is the length of the chromosome. The values of r and l for the birefringent species were measured directly from the Metripol photomicrographs, whereas the dimensions for the C. cohnii and A. carterae chromosomes were obtained from the TEM photomicrographs. To prevent underestimation of the chromosome dimensions, a comparison of the data acquired from the fluorescence photographs for the two species was also performed. Again, more than 100 clearly distinct chromosomes for each species were measured, and the average values of r and l were obtained for calculations.

The value of half the helical pitch (P/2) is the distance between the arches seen in the electron micrographs of the dinoflagellate chromosomes (see Fig. 3). As different fracture planes are produced during the sectioning process, the exact P/2 values of the dinoflagellate species can be highly disparate. Instead of averaging all the measured values of P/2, an average value for the largest 100 P/2 values was used to represent the P/2 of each species. This is because the largest value of P/2 could be obtained only from chromosomes that exhibited a fracture plane along their cholesteric axes.

Fig. 3.

TEM photomicrographs of the chromosomes of the six investigated dinoflagellate species, A. carterae (A), C. cohnii (B), A. tamarense (C), H. triquetra (D), K. brevis (E), and P. micans (F). (A to F) Series of arches were observed in the chromosomes, which resembled the plectonemic structure of the cholesteric liquid crystalline DNA. The similarity in the architectures of the chromosomes among different dinoflagellate species suggested that the structure of the chromosomes is not sufficient to cause birefringence. Magnifications are indicated by the scale bars in the photomicrographs.

Transmission electron microscopy.

The standard glutaraldehyde-osmium tetroxide protocol that was used previously for other dinoflagellate chromosomes (34) was employed for all cell fixation and TEM specimen preparation. Dinoflagellate cells for each species were harvested, fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde-0.1 M PIPES (1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic) buffer overnight at 4°C, and then subjected to a secondary fixative of 1% osmium tetroxide-0.1 M PIPES buffer for 1 h at 4°C in the dark. Ethanol-dehydrated postfixed cells were infiltrated and embedded with the liquid plastic monomers and epoxy mixtures according to the manufacturer's instructions. The hardened resin mold for each species was eventually trimmed into 70-nm thin sections and subjected to double-positive staining with 1% uranyl acetate in 50% methanol and 0.25% lead citrate in 0.1 N sodium hydroxide. The stained sections were examined under a Jeol TEM-100CX transmission electron microscope for the ultrastructural examination of the dinoflagellate nuclei and chromosomes.

Fluorescence imaging.

Fluorescence microscopy was used to observe the morphology of dye-stained chromosomes. Cultures were concentrated by centrifugation and were fixed overnight in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) with 3% paraformaldehyde (PFA). For chromosome staining, the fixed cells were incubated with 0.02 μg ml−1 DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) in PBS for 15 min. The chromosomes were observed under a Leica DMLS microscope equipped with a 372- to 456-nm filter. Fluorescence photomicrographs were obtained with the attached Pixera Penguin 600CL digital camera.

Induced expulsion of the nucleus.

Cells were incubated with 1% to 5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 at room temperature for at least 30 min to permeabilize them. The cells were harvested as described above, and double-distilled water was added to trigger the expulsion of the nucleus by osmotic pressure. Force was applied by slightly tapping the coverslip with a pipette tip. These cell suspensions were immediately subjected to Metripol studies, and then the DNA was stained with DAPI for further analysis. The chromosomes were also counted.

RESULTS

Birefringence of dinoflagellate liquid crystalline chromosomes.

We investigated the relationship between birefringence and DNA condensation by analyzing the chromosomes of six different dinoflagellates species. Three further Symbiodinium, Lingulodinium, and Karlodinium species were given a less rigorous examination simply to establish the presence or absence of birefringence. The selected species have different taxonomical positions within the dinoflagellate clade, as determined previously using rRNA phylogenetic analysis (reviewed in reference 2). The same species were also characterized according to DNA content and number of chromosomes, as well as their chromosomal arrangements in the nucleus (Table 1). Birefringent chromosomes could be identified in some of the dinoflagellate species (A. tamarense, H. triquetra, K. brevis, and P. micans) when they were viewed between the cross polars, with the added advantage that this method of examination is entirely noninvasive and dispenses with the need for any sort of chemical staining (Fig. 1A to D, white arrows point to the location of the birefringent chromosomes). Their identities as chromosomes of these birefringent intranuclear bodies were confirmed by the analogous positions and arrangements of DAPI-stained chromosomes in fluorescence photomicrographs (Fig. 1A to D). Furthermore, direct measurements showed very similar values for both the widths of the birefringent chromosomes seen under crossed polars and chromosomal widths obtained from the thin-section electron photomicrographs (with a standard deviation of ≤0.12 μm). This confirmed that the anisotropic entities identified in the nuclei from some of the species of dinoflagellates were most definitely the chromosomes and that for most species the liquid crystalline dinoflagellate chromosome was entirely birefringent.

Table 1.

Comparison of select dinoflagellate species

| Parameter | Value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. tamarense | C. cohnii | A. carterae | K. brevis | H. triquetra | P. micans | |

| Order | Gonyaulacales | Gonyaulacales | Gymnodiniales | Gymnodiniales | Peridiniales | Prorocentrales |

| Family | Gonyaulacaceae | Crypthecodiniaceae | Gymnodiniaceae | Gymnodiniaceae | Heterocapsaceae | Prorocentraceae |

| Mean cell size (μm) | 25a | 13 | 15b | 24a | 19a | 30a |

| Shape of nucleus | U-shaped tube | Spherical | Oblate ovoid | Oblate spheriod | Oblate spheriod | C shaped (or lung shaped) |

| No. of chromosomes | 143c | 99c | 32c | 121c | 100 | 68d |

| DNA content per cell (pg/Mb) | 103.5e/1,012 | 3.8c/3,716 | 2.95e/2,885 | 57.1e/55,843 | 24.1e/23,567 | 115.2e/112,666 |

| Avg DNA content per chromosome (pg/Mb) | 0.724/708 | 0.038/37 | 0.092/90 | 0.472/462 | 0.241/236 | 1.694/1,657 |

| Shape of chromosomesf | Long thin rods | Small round rods | Small round rods | Rods | Small round rods | Thick rods |

| Birefringent chromosomes | Presente | Absent | Absent | Present | Present | Present |

The mean cell size represents the median length of the cell. The data were obtained from the catalogue of CCMP.

The mean cell size represents the median length of the cell. The data were obtained from reference 25.

The number of chromosomes and DNA content were obtained from reference 43.

The number of chromosomes was obtained from reference 9.

The DNA content (n) was obtained from reference 25.

Observed under DAPI staining.

Fig. 1.

Polarizing, fluorescence, and bright-field photomicrographs of dinoflagellates. The polarizing and bright-field images in each panel represent the same cell. Each fluorescence image was taken of a different DAPI-stained cell from the same dinoflagellate species. Six different dinoflagellate species (H. triquetra [A], A. catenella [B], K. brevis [C], P. micans [D], A. carterae [E], and C. cohnii [F]) were investigated. Four species (A. tamarense, K. brevis, H. triquetra, and P. micans) showed distinctive birefringence in their chromosomes under the polarizing microscope (A to D, white arrows). These kinds of birefringent chromosomes, however, were absent in both A. carterae and C. cohnii (E and F). Scale bars, 10 μm.

There were variations in the morphologies of the chromosomes between species, both in the individual chromosome dimensions and in their arrangement within the nucleus (Table 1). The precise value of the retardance for the chromosomes could not be easily determined using the standard crossed-polarizer microscope. However, the absolute retardance, |Sinδ|, of the anisotropic chromosomes could be quantified using the Metripol rotating-polarizer system. The birefringent chromosomes of A. tamarense, K. brevis, H. triquetra, and P. micans all showed a degree of retardance, as seen in the Metripol photomicrographs (Fig. 2A to D). The false-color |Sinδ| Metripol images use dark purple to label any anisotropies. The more intense the purple, the greater the absolute retardance.

Fig. 2.

Metripol photomicrographs of dinoflagellates. Different dinoflagellate species (H. triquetra [A], A. catenella [B], K. brevis [C], P. micans [D], A. carterae [E], and C. cohnii [F]) were studied. Signals of retardance were detected in the birefringent LCCs in A. tamarense, K. brevis, H. triquetra, and P. micans (A to D, white arrows). The relative birefringence varied among the species, as denoted by the intensity of the color in the Metripol |Sinδ| photomicrographs. No obvious retardation signals were detected in the chromosomes of A. carterae and C. cohnii (E and F). Notably, some cellular contents, e.g., starch granules and thecal plates, are birefringent and give strong signals in the Metripol photomicrographs.

Birefringence is apparently absent in certain dinoflagellates.

Birefringent chromosomes are apparently absent in both A. carterae and C. cohnii, as seen in both the polarizing (Fig. 1E and F) and Metripol (Fig. 2E and F) photomicrographs. The absence of birefringent chromosomes in A. carterae and C. cohnii cannot be accounted for by the differences in chromosome morphology, as they have round, rod-shaped chromosomes similar to those seen for the birefringent species H. triquetra (Fig. 1A). There are several possibilities that may account for the lack of observable birefringence, and all of them involve the superimposition of other interfering anisotropic bodies. These can be starch inclusions, the theca, or even other chromosomes aligned perpendicular to one another. It was not until the chromosomes were examined in isolation that we could determine if they indeed possessed any anisotropic qualities. The downside to this approach is that, once separated from the protective environment of the nucleus within the cell, the chromosomes very quickly decondense, losing any birefringence they may have.

Despite similar series of nested bands and arches that resemble in vitro cholesteric liquid crystalline DNA (29, 39), the nanoarchitectures of these arches, and especially the lengths of the helical pitches, were different between species (Fig. 3). It is important to note that all the specimens in our study were prepared using identical procedures to minimize possible artifacts that might be induced during the fixation and sectioning steps (12). The regularity of the helical pitch was also less obvious for the nonbirefringent species A. carterae and C. cohnii than for the birefringent species. Moreover, there were apparently fewer, less dense DNA fibers within each helical pitch of the chromosomes from A. carterae and C. cohnii (Fig. 3).

The variations in the nanoarchitecture of the chromosomes may provide a plausible reason for the disappearance of birefringence in the chromosomes of certain species, as it seems that birefringence appears in those chromosomes that are arranged with more regular helical pitches. Overall, the fact that there is similarity in the global plectonemic structures of the series of bands and arches but variation in the nanoarchitecture among the chromosomes of different species may indeed suggest multiple organizational orders in the dinoflagellate LCCs.

Birefringent chromosomes were present in isolated nuclei of nonbirefringent species.

One possible explanation for the absence of birefringent chromosomes in certain species is the cancellation of retardance between the overlapping DNA layers. In other words, the individual chromosomes may be intrinsically birefringent, but the birefringence is optically “cancelled out” by the compactly packed chromosomes (anisotropies) within the nucleus. To test such a possibility, the nuclei of dinoflagellates were released from cells by osmotic shock. The extended nuclei were subjected to Metripol microscopy to verify the possible contribution of the chromosome arrangement to the appearance of birefringent chromosomes.

Nuclei of C. cohnii, a species with no apparent chromosomal birefringence (Fig. 1F and 2F), were released from live cells. The nuclei under these conditions were slightly extended, and the chromosomes appeared to be more evenly spread in the space. As the chromosomes became more spread out, a certain degree of birefringence was clearly detected from the C. cohnii chromosomes within the isolated nucleus (Fig. 4A). To verify that the birefringence originated from the chromosomes and not other cellular components, the chromosomes were confirmed with a DNA-specific stain (DAPI) (data not shown). Though the intensity of the retardance was relatively weak compared with the chromosomes of the birefringent species (Fig. 2), birefringence was clearly detected in these disorganized chromosomes (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Birefringence was detected in expelled nuclei. (A) (Left to right) Birefringent chromosomes could be observed when the nucleus of C. cohnii, a species that does not have obvious birefringent chromosomes in its intact cell, was expelled by osmotic pressure. White arrows point to the expelled nucleus. (B) (Left to right) Cells of H. triquetra, a species that has birefringent chromosomes, were subjected to a similar study. Birefringence of the chromosomes was retained even in the expelled nucleus.

The observed birefringence in the reorganized chromosomes directly supports the notion that the arrangement of chromosomes makes a significant contribution to the appearance of birefringence in the chromosomes. The “spreading” of C. cohnii chromosomes would have reduced the subtraction effect of retardation, resulting in the expression of chromosomal birefringence. Under the same treatment, the birefringent chromosomes of H. triquetra remained birefringent, even though the chromosomes were spread in the enlarged nucleus (Fig. 4B). This argues against the possibility that the birefringent chromosomes resulted from other factors, such as dilution of the chromosomal proteins and the concentration of counterions.

Relationships between DNA condensation, chromosome architecture, and birefringence.

Several parameters of the dinoflagellate chromosomes, including the DNA content per chromosome, chromosomal dimensions, and absolute retardance, were measured in each species to uncover any possible relationship to the appearance of birefringence in the chromosomes. A positive relationship was observed between the amount of DNA per chromosome and the level of absolute retardance (Fig. 5A). Birefringent chromosomes were also more obvious in those species that possess higher DNA content. The DNA content and, more specifically, the DNA density play crucial roles in determining whether a chromosome appears birefringent. The ability of densely packed DNA to form a liquid crystal hinges upon the local orientation of the DNA molecules within the chromosome itself. This is accomplished by the DNA strands being generally aligned parallel to one another at any given point in the chromosome, while at the same time, the DNA molecules are perpendicular to the long axis of the chromosome. The parallel DNA molecules also present a gradual rotation of the average orientation when measured along the length of the chromosome proper. These are the classic hallmarks of a cholesteric liquid crystal and are what provides the dinoflagellate chromosome with its birefringent nature.

Fig. 5.

Chromosomal birefringence and dinoflagellate genomes. (A) Relationship between DNA content and retardance in dinoflagellates. The DNA content of each dinoflagellate species was defined as the amount of DNA per haploid cell (n) and was obtained from reference 25 (Table 1), while the values of retardance correspond to the average value of |Sinδ| for 100 chromosomes obtained through the Metripol system, as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Relationship between DNA density and retardance in dinoflagellates. The DNA density was defined as the average mass (pg) of the DNA in each chromosome per unit chromosomal volume (μm3). The number of chromosomes of each dinoflagellate species was obtained from the work of Spector (43) and Dodge (9a) and the experiment with induced expulsion of nuclei (data not shown). The chromosomal volume, on the other hand, was calculated under the assumption that the chromosome had a perfect rod shape (see Materials and Methods). A positive relationship can be observed between the DNA density and retardance in the birefringent species.

The DNA density per chromosome, which represents how closely the DNA molecules are packaged within the chromosomes, does not have a simple relationship to the level of retardance (Fig. 5B). Disregarding the apparently nonbirefringent species (A. carterae and C. cohnii), a positive correlation was observed between the retardance and the DNA density in the group of birefringent species. This positive relationship was determined to have a coefficient of correlation of 0.274. In these birefringent species, more compacted chromosomes seemed to yield a higher level of retardance. The chromosomes are densely packed in the nuclei of A. carterae and C. cohnii, but they have a lower DNA content and a loosely packed nanostructure (Fig. 3A and B, respectively). The measured DNA density for A. carterae was found to be just above 0.2 pg μm−3 (precisely 220 ± 80 mg ml−1), slightly more than previously reported by quantitative scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) (3, 26). The deviation between the values may be explained by the STEM failing to detect the extrachromosomal DNA, which is located at the peripheries of chromosomes, thus becoming undetectable by the ratio-contrast technique (3, 26). For this reason, the actual DNA density of the cell may well have been underestimated. Moreover, a recent advance in flow cytometric analysis of fluorescently sorted cells was able to provide a more reliable and accurate measurement of the DNA content (25). The DNA content of A. carterae in the current study (2.95 pg/cell) is larger than the reference value (1.8 pg/cell) that was used in the measurements by Bohrmann et al. (3). The unexpectedly high DNA densities in A. carterae and C. cohnii suggest that the appearance of birefringence does not solely depend on the DNA density, but that other factors may also play a role.

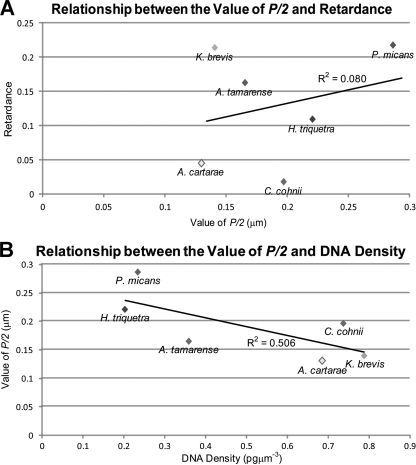

According to the model proposed by Bouligand et al. (4a), half the helical pitch (P/2) of the dinoflagellate chromosome is the distance between two DNA discs (these discs are conceptual only, for the purposes of imagining the model; in fact, the average orientation of the DNA molecules along the pitch changes gradually and smoothly) that have a rotation of 180° in their molecular orientations (Fig. 6). The value of P/2 is revealed as the distance between arches, or between two neighboring ridges, seen in the electron micrographs and therefore can be used as a defining value of the structure of the chromosomes. The measured values of P/2 from different dinoflagellate species in the current study were within the range of helical pitches that were previously reported (26). There was an apparent positive correlation between the value of retardance and the value of P/2 (Fig. 7 A), implying a direct contribution of the chromosome architecture to the level of birefringence. On the other hand, the values of P/2 appeared to have a negative dependence on the DNA density (Fig. 7B), so that a smaller helical pitch was observed in more compacted dinoflagellate chromosomes. Two prevailing models of dinoflagellate chromosomes involve twisting (see Discussion) (29, 37). Assuming that the ridges that constitute the helical pitches were indicative of higher-order twisting of dinoflagellate chromosomal DNA, a smaller helical pitch would intuitively reflect tighter twisting.

Fig. 6.

Proposed model of dinoflagellate chromosomes. (A) The structure of the dinoflagellate chromosome was proposed by Livoland and Bouligand (31). The dinoflagellate chromosome may be composed of multiple stacks of DNA discs that are twisted very tightly together. Half the helical pitch (P/2) is defined as the distance between two DNA discs (layers) that have 180° of rotation. (B) The corresponding half of the helical pitch seen in the electron micrograph when the fracture plane is along the longitudinal (cholesteric) axis of the chromosome.

Fig. 7.

Contribution of half the helical pitch to birefringence. (A) Relationship between the value of half the helical pitch (P/2) and retardance. The value of P/2 for each dinoflagellate species was calculated from transmission electron micrographs, as described in Materials and Methods. As the helical pitch is a direct reflection of the chromosome structure, the positive relationship observed among the dinoflagellates implies a contribution of the chromosome architecture to the level of birefringence. (B) Relationship between the value of half the helical pitch (P/2) and DNA density in dinoflagellates. The negative correlation between the value of P/2 and the DNA density is in agreement with the twisting nature of the dinoflagellate chromosomes.

DISCUSSION

LCCs probably represent the highest order of DNA condensation possible for living cells. Prokaryotic histone-like proteins have been found in dinoflagellates (45) but are present at very low concentrations in the LCCs (41). Condensation of dinoflagellate LCCs is therefore unlikely to involve DNA-protein costructures mediated by small chromosomal proteins, such as protamine in the birefringent nuclei of sperm (1, 28) or the Dps-induced cocrystals with DNA in stressed bacteria (10, 45). The amount of protein required for such DNA complexes is simply not present at a high enough molar ratio to suggest that this method of condensation is solely responsible for the liquid crystalline nature of the dinoflagellate chromosomes.

At high concentrations, DNA can spontaneously self-assemble into aggregations, leading to a separation between the liquid crystalline anisotropic phase and the isotropic phase (23, 32, 49). Confinement of the eukaryotic nucleus by the highly fastidious nuclear membrane imposes a very crowded environment with many macromolecules close to their solubility limit (3, 23). Any molecules present within the nucleus are thus subjected to the volume-excluded effect, which helps to drive the formation of self-assembled structures. The importance of this sequestration within a highly controlled nuclear environment for the maintenance of LCCs is given further support due to the fact that dinoflagellates undergo a closed mitosis in which the nuclear membrane is never dismantled. A liquid crystalline chromosome is proposed to consist of a highly condensed core, with transcriptionally active DNA loops being allowed to decondense at the chromosomal periphery (5, 33, 36–38). Nucleosomes are considered a solution to this crowded situation by serving as a chaperone for DNA packaging/unpackaging (36). In the absence of nucleosomes, the ability of peripheral transcriptional loops to be maintained in such a crowded environment is made possible only because the bulk of the remaining DNA is maintained as a highly dense liquid crystalline chromosome. The ability to straighten DNA by using the recombinant dinoflagellate histone-like protein HCc3 (6) and the presence at the chromosomal periphery of the native HCc protein (13, 42) are both consistent with its role in maintaining these “extrachromosomal” loops. In essence, LCCs and the nucleosomal chromosomes probably solve the same problems; they enable compartmentalization, replication, and selective activation of ever-increasing genomes. Although lacking the transcriptional finesse conferred by the “histone codes” (18), LCCs represent a simple, efficient, and elegant method of DNA condensation that is nevertheless able to overcome all of the transcriptional challenges present in a highly evolved eukaryotic organism.

We present here the first report of the quantitative measurement of birefringence of in vivo LCCs. Although birefringent chromosomes are readily visible in many dinoflagellates, the intensities differ significantly between species. Cachon et al. (5) attempted to quantify the birefringence of the chromosomes by using the “coefficient of birefringence” (ne − no, where ne and no are the refractive indexes for polarizations parallel and perpendicular, respectively, to the axis of anisotropy). This method relied on the measurements in the angle that apparently gives the strongest birefringence when observed under cross polars. The values obtained in this way were in fact relatively subjective. The Metripol system, on the other hand, gives a quantitative measurement of retardance by the RP method (43) and applies a Jones matrix to the data obtained from the intensity of transmitted light through each “pixel” of the resultant captured image. Both of the methods discussed above, in fact, do not take the sample thickness into account and can be considered only relative measurements of birefringence. The absolute retardance values obtained via the Metripol system are more representative in quantifying the birefringence, since they contain virtually no subjective errors and the variations in the azimuth of the chromosomes have already been compensated for during the automated software calculations.

The fixative-free conditions of polarizing microscopy mean that the measurements of the chromosomes truly reflect the in vivo conditions compared with those values acquired from electron photomicrographs. The relative amount of birefringence has been recently employed as a quality check for proper DNA condensation and hence superior human spermatozoa for use in intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) (44). The birefringence in the dinoflagellate nuclei not only reflects the liquid crystalline arrangement in the chromosomes, but can also be considered a manifestation of the extremely compact organization of the massive genomes. The measured values in the current study mark the first correlation between the appearance of birefringence and chromosomal dimensions. The observed positive relationships between the DNA content (Fig. 5A), the DNA density (Fig. 5B), and retardance highlight the importance of the DNA concentration, in regard to not only the level of birefringence, but also the consequent formation of in vivo liquid crystalline DNA.

The positive correlation between the absolute retardance and the value of P/2 confirms a direct contribution of the architecture of the DNA within the chromosomes to its anisotropic nature (Fig. 7A). This notion is further strengthened by the fact that birefringence was detected in naked chromosomes that had been expelled from lysed C. cohnii cells (Fig. 4A) and thus were not influenced by any other contributing optical factors. Quite often, an instance of birefringence can be masked by several factors, including the presence of intracellular anisotropic bodies, such as starch granules or the cellulosic theca present in the armored dinoflagellates. The orientation of stacked birefringent chromosomes to one another can also have an additive or subtractive effect on individual birefringence when the optical train passes through several stacked chromosomes aligned perpendicular to one another. The only way to truly determine if a given species possesses birefringent chromosomes is to examine them out of context after they have been expelled from their protective environment. The drawback of this method is that the naked chromosomes rapidly undergo a decondensation process and quickly lose any native birefringence. We were lucky to capture some traces of birefringence for the recently expelled C. cohnii chromosomes shortly after the cells were ruptured and the nuclei were expelled. The current data therefore support the idea that the appearance of birefringence relies on both the level of condensation and the arrangement of the chromosomes in the nucleus.

Previous studies provided substantial and highly detailed information about the structure of dinoflagellate chromosomes. Based on the central hollow and furrows that were observed in the spread preparation of twisted DNA bundles (28, 37, 45), Oakley and Dodge (37) proposed the “toroidal chromonema” to account for the structure of the dinoflagellate chromosome. In another model, Livolant and Bouligand suggested that the dinoflagellate chromosomes were composed of stacks of conceptual DNA discs that progressively turned along the longitudinal axis (30, 31). The inverse relationship between the value of P/2 and the DNA density (Fig. 7B) imples the twisted nature of the dinoflagellate chromosomes: the tighter the twist, the higher the density.

The evolutionary development of LCCs by ancestral alveolates probably involved concomitant loss of the nucleosomal histones and the recruitment of some prokaryotic proteins (46). Nucleosomes impose a burden on the progress of DNA replication (36). The absence of nucleosomes may thus remove a size limit on the capacity and speed of eukaryotic DNA replication. The genome size of the ancestral alveolate probably increased substantially after the loss of the core histones. It was also argued that the immiscibility of liquid crystalline phases is actually required for the unhindered separation of the newly replicated daughter strands after replication without core histones (4). The formation of liquid crystalline DNA may be a natural survival strategy of cells that lost their nucleosomes. Interestingly, in the absence of the wild-type Dps-DNA cocrystals, starvation stress induces the formation of liquid crystalline DNA in Dps− bacteria, (10, 45).

Phase separation is increasingly understood to be important in the regulation of macromolecules in the crowded environment of the nucleus (49, 50). Even isolated nucleosomes can form a liquid crystalline phase (33). It is unclear whether the evolution of the nuclear envelope was concomitant with the evolution of the nucleosomes. Liquid crystalline states of DNA, different from the dinoflagellate LCCs, might well have been intermediate stages in the evolution of the nucleosomal chromosomes of today.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The present study was partly supported by a CERG grant (HKUST6421/06 M) from the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong and Grant RPC06/07.SC10 from the University Grant Council to J.T.Y.W.

We thank K. K. Fung (Physics Department, HKUST) for discussions in relation to birefringence.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balhorn R. 1982. A model for the structure of chromatin in mammalian sperm. J. Cell. Biol. 93:298–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett M., Wong J. T. Y. 2006. Evolution and diversity of dinoflagellates: molecular perspectives, p89–115InSharma A. K., Sharma A.(ed.), Plant genome: biodiversity and evolution, vol. 2B Lower groups. Science Publishers, Enfield, NH [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohrmann B., Haider M., Kellenberger E. 1993. Concentration evaluation of chromatin in unstained resin-embedded sections by means of low-dose ratio-contrast imaging in STEM. Ultramicroscopy 49:235–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouligand Y., Norris V. 2001. Chromosome separation and segregation in dinoflagellates and bacteria may depend on liquid crystalline states. Biochimie 83:187–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Bouligand Y., Soyer M.-O., Puiseux-Dao S. 1968. The fibrillary structure and orientation of chromosomes in dinoflagellata. Chromosoma 24:251–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cachon J., Sato H., Cachon M., Sato Y. 1989. Analysis by polarizing microscopy of chromosomal structure among dinoflagellates and its phylogenetic involvement. Biol. Cell 65:51–60 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan Y. H., Wong J. T. Y. 2007. Concentration-dependent organization of DNA by the dinoflagellate histone-like protein HCc3. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:2573–2583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook P. R., Marenduzzo D. 2009. Entropic organization of interphase chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 186:825–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costas E., Goyanes V. 1987. Ultrastucture and division behaviour of dinoflagellate chromosomes. Chromosoma 95:435–441 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodge J. D. 1965. Chromosome structure in dinoflagellates and the problem of the mesokaryotic cell. Progr. Protozool. 6:264–265 [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Dodge J. D. 1963. Chromosome numbers in some marine dinoflagellates. Bot. Mar. 5:121–127 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frenkiel-Krispin D., Levin-Zaidman S., Shimoni E., Wolf S. G., Wachtel E. J., Arad T., Finkel S. E., Kolter R., Minsky A. 2001. Regulated phase transitions of bacterial chromatin: a non-enzymatic pathway for generic DNA protection. EMBO J. 20:1183–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuentes-Mascorro G., Serrano H., Rosado A. 2000. Sperm chromatin. Arch. Androl. 45:215–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gautier A., Michel-Salamin L., Tosi-Couture E., McDowall A. W., Dubochet J. 1986. Electron microscopy of the chromosomes of dinoflagellates in situ: confirmation of Bouligand's liquid crystal hypothesis. J. Ultrastruct. Mol. Struct. Res. 97:10–30 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geraud M.-L., Sala-Rovira M., Herzog M., Soyer-Gobillard M.-O. 1991. Immunocytochemical localization of the DNA-binding protein HCC during the cell cycle of the histone-less dinoflagellate protoctista Crypthecodinium cohnii b. Biol. Cell 71:123–134 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillard R. R. L., Ryther J. H. 1962. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt and Detonula confervacea Cleve. Can. J. Microbiol. 8:229–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hancock R. 2004. Internal organisation of the nucleus: assembly of compartments by macromolecular crowding and the nuclear matrix model. Biol. Cell 96:595–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hancock R. 2004. A role for macromolecular crowding effects in the assembly and function of compartments in the nucleus. J. Struct. Biol. 146:281–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hancock R. 2008. Self-association of polynucleosome chains by macromolecular crowding. Eur. Biophys. J. 37:1059–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herzog M., Soyer-Gobillard M. O. 1981. Distinctive features of dinoflagellate chromatin. Absence of nucleosomes in a primitive species Prorocentrum micans E. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 23:295–302 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herzog M., Von Boletzky S., Soyer-Gobillard M. O. 1984. Ultrastructural and biochemical nuclear aspects of Eukaryote classification: independent evolution of the dinoflagellates as a sister group of the actual Eukaryotes? Orig. Life. Evol. Biosph. 13:205–215 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howell D., Jones A. P., Dobson D. P., Milledge H. J., Harris J. W. 2006. Birefringence analysis of diamond utilising the Metripol system. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta Suppl. 70:A268 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin L.-W., Claborn K. A., Kurimoto M., Geday M. A., Maezawa I., Faranak S., Estrada M., Kaminksy W., Kahr B. 2003. Imaging linear birefringence and dichroism in cerebral amyloid pathologies. Proc. Natl. Acad. of Sci. U. S. A. 100:15294–15298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katoh K., Hammar K., Smith P. J. S., Oldenbourg R. 1999. Birefringence imaging directly reveals architectural dynamics of filamentous actin in living growth cones. Mol. Biol. Cell 10:197–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellenberger E. 1988. About the organisation of condensed and decondensed non-eukaryotic DNA and the concept of vegetative DNA (a critical review). Biophys. Chem. 29:51–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kellenberger E., Arnold-Schulz-Gahmen B. 1992. Chromatins of low-protein content: special features of their compaction and condensation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 100:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaJeunesse T. C., Lambert G., Andersen R. A., Coffroth M. A., Galbraith D. W. 2005. Symbiodinium (pyrrhophyta) genome sizes (DNA content) are smallest among dinoflagellates. J. Phycol. 41:880–886 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leforestier A., Livolant F. 1993. Supramolecular ordering of DNA in the cholesteric liquid crystalline phase: an ultrastructural study. Biophys. J. 65:56–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livolant F. 1978. Positive and negative birefringence in chromosomes. Chromosoma 68:45–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livolant F. 1984. Cholesteric organization of DNA in the stallion sperm head. Tissue Cell 16:535–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livolant F. 1984. Cholesteric organization of DNA in vivo and in vitro. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 33:300–311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livolant F., Bouligand Y. 1978. New observations on the twisted arrangement of dinoflagellate chromosomes. Chromosoma 68:21–44 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livolant F., Bouligand Y. 1980. Double helical arrangement of spread dinoflagellate chromosomes. Chromosoma 80:97–118 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livolant F., Leforestier A. 1996. Condensed phases of DNA: structures and phase transitions. Prog. Polym. Sci. 21:1115–1164 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Livolant F., Mangenot S., Leforestier A., Bertin A., de Frutos M., Raspaud E., Durand D. 2006. Are liquid crystalline properties of nucleosomes involved in chromosome structure and dynamics? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 364:2615–2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mak C. K. M., Hung V. K. L., Wong J. T. Y. 2005. Type II topoisomerase activities in both the G1 and G2/M phases of the dinoflagellate cell cycle. Chromosoma 114:420–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marenduzzo D., Micheletti C., Cook P. R. 2006. Entropy-driven genome organization. Biophys. J. 90:3712–3721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minsky A., Ghirlando R., Reich Z. 1997. Nucleosomes: a solution to crowded intracellular environment? J. Theor. Biol. 188:379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oakley B. R., Dodge J. D. 1979. Evidence for a double-helically coiled toroidal chromonema in the dinoflagellate chromosome. Chromosoma 70:277–291 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oldenbourg R., Salmon E. D., Tran P. T. 1998. Birefringence of single and bundled microtubules. Biophys. J. 74:645–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rill R. L., Livolant F., Aldrich H. C., Davidson M. W. 1989. Electron microscopy of liquid crystalline DNA: direct evidence for cholesteric-like organization of DNA in dinoflagellate chromosomes. Chromosoma 98:280–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rill R. L., Strzelecka T. E., Davidson M. W., van Winkle D. H. 1991. Ordered phases in concentrated DNA solutions. Physica A 176:87–116 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rizzo P. J., Morrie L. D. 1972. Chromosomal proteins in the dinoflagellate Gyrodinium cohnii. Science 176:796–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sala-Rovira M., Geraud M. L., Caput D., Jacques F., Soyer-Gobillard M. O., Vernet G., Herzog M. 1991. Molecular cloning and immunolocalization of two variants of the major basic nuclear protein (HCc) from the histone-less eukaryote Crypthecodinium cohnii (Pyrrhophyta). Chromosoma 100:510–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spector D. L. 1984. Dinoflagellate nuclei, p. 107–147InSpector D. L.(ed.), Dinoflagellates. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tuttle R. C., Loeblich A. R. 1975. An optimal growth medium for the dinoflagellate Crypthecodinium cohnii. Phycologia 14:1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolf S. G., Frenkiel-Krispin D., Arad T., Finkel S. E., Kolter R., Minsky A. 1999. DNA protection by stress-induced biocrystallization. Nature 400:83–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong J. T. Y., Kwok A. C. M. 2005. Proliferation of dinoflagellates: blooming or bleaching. Bioessays 27:730–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong J. T. Y., New D. C., Wong J. C. W., Hung V. K. L. 2003. Histone-like proteins of the dinoflagellate Crypthecodinium cohnii have homologies to bacterial DNA-binding proteins. Eukaryot. Cell 2:646–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye C., Liu S., Teng X., Fang Q., Li G. 2006. Morphological and optical characteristics of nanocrystalline TiO2 thin film by quantitative optical anisotropy and imaging techniques. Measurement Sci. Technol. 17:436–440 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zimmerman S. B., Minton A. P. 1993. Macromolecular crowding: biochemical, biophysical, and physiological consequences. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 22:27–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zimmerman S. B., Murphy L. D. 1996. Macromolecular crowding and the mandatory condensation of DNA in bacteria. FEBS Lett. 390:245–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]