Abstract

The Aspergillus nidulans endocytic internalization protein SlaB is essential, in agreement with the key role in apical extension attributed to endocytosis. We constructed, by gene replacement, a nitrate-inducible, ammonium-repressible slaB1 allele for conditional SlaB expression. Video microscopy showed that repressed slaB1 cells are able to establish but unable to maintain a stable polarity axis, arresting growth with budding-yeast-like morphology shortly after initially normal germ tube emergence. Using green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged secretory v-SNARE SynA, which continuously recycles to the plasma membrane after being efficiently endocytosed, we establish that SlaB is crucial for endocytosis, although it is dispensable for the anterograde traffic of SynA and of the t-SNARE Pep12 to the plasma and vacuolar membrane, respectively. By confocal microscopy, repressed slaB1 germlings show deep plasma membrane invaginations. Ammonium-to-nitrate medium shift experiments demonstrated reversibility of the null polarity maintenance phenotype and correlation of normal apical extension with resumption of SynA endocytosis. In contrast, SlaB downregulation in hyphae that had progressed far beyond germ tube emergence led to marked polarity maintenance defects correlating with deficient SynA endocytosis. Thus, the strict correlation between abolishment of endocytosis and disability of polarity maintenance that we report here supports the view that hyphal growth requires coupling of secretion and endocytosis. However, downregulated slaB1 cells form F-actin clumps containing the actin-binding protein AbpA, and thus F-actin misregulation cannot be completely disregarded as a possible contributor to defective apical extension. Latrunculin B treatment of SlaB-downregulated tips reduced the formation of AbpA clumps without promoting growth and revealed the formation of cortical “comets” of AbpA.

Germinating asexual spores (conidiospores) of Aspergillus nidulans transiently undergo isotropic growth (“swelling”) before establishing a polarity axis that grows by apical extension, leading to the characteristic tubular morphology of the fungal cell (15, 16, 33). Stable maintenance of a polarity axis at the high apical extension rates of A. nidulans (∼0.5 μm/min at 25°C) (23) can be attributable, at least in part, to the polarization of the secretory apparatus and the predominant and highly efficient delivery of secretory vesicles to the apex (8, 18, 40, 49). In addition, work from several laboratories strongly indicated that hyphal tip growth also involves endocytosis. A key observation supporting this involvement was that despite the fact that endocytosis can occur elsewhere, the endocytic internalization machinery predominates in the hyphal tip, forming a subapical collar. The spatial association of this collar with the apical region where secretory materials are delivered would allow removal of excess lipids/proteins reaching the plasma membrane with secretory vesicles (1, 2, 30, 49, 51, 57), but, most importantly, rapid endocytic recycling (i.e., efficient endocytosis of membrane proteins followed by their redelivery to the plasma membrane) can generate and maintain polarity, as shown with the v-SNARE and secretory-vesicle-resident SynA, which is a substrate of the subapical endocytic ring (1, 49, 52). It is plausible that such a mechanism could drive the polarization of one or more proteins acting as positional cues to mediate polarity maintenance.

Genetic evidence strongly supported the conclusion that endocytosis is required for apical extension. Mutational inactivation of the A. nidulans fimbrin FimA or of the small GTPase ArfBArf6 (a regulator of endocytosis from fungi to mammals), led to delayed polarity establishment and morphologically aberrant tips indicative of polarity maintenance defects (30, 51). These mutations, although very severely debilitating, are not lethal. In contrast, heterokaryon rescue showed that SlaB, a key F-actin regulator of the endocytic internalization machinery (26), is essential in A. nidulans (2). slaBΔ cells are able to establish polarity, but they arrest in apical extension during the very early steps of polarity maintenance with a bud-like germ tube (2). However, work with Aspergillus oryzae using a thiamine-repressible promoter to drive A. oryzae End4 (AoEnd4) (SlaB) expression showed that although endocytosis was prevented and hyphal morphology altered under repressing conditions, hyphal tip extension and polarity maintenance were not completely abolished (20), perhaps suggesting that the phenotype of the thiamine-repressed conditional allele might not fully resemble the null phenotype.

F-actin strongly predominates in the hyphal tips (2, 14, 17, 49, 51). Because endocytic internalization is powered by F-actin (27), predominance of endocytic “patches” (i.e., sites of endocytic internalization) in the tip accounts, at least in part, for F-actin polarization. However, F-actin plays fundamental nonendocytic roles in the tip; for example, actin cables nucleated by the SepA formin localizing to the apical crescent are thought to play a major role in secretion, whereas a network of F-actin microfilaments appears to be a major component of the Spitzenkörper (4, 21, 43, 49). Notably, all genes used to address the role of endocytosis in apical extension share in common their involvement in regulating F-actin. Thus, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ArfB orthologue Arf3p regulates endocytosis but also appears to regulate F-actin at multiple levels (12, 28, 44). Like their respective S. cerevisiae orthologues Sla2p and Sac6p, SlaB and FimA are key components of endocytic patches, but in budding yeast their orthologues appear to regulate F-actin dynamics beyond endocytosis (27, 35, 56).

To gain insight into the essential role of SlaB in A. nidulans, we designed a conditional expression allele. Time-lapse microscopy under restrictive conditions demonstrated that polarity establishment is essentially normal but that these mutant germ tubes arrested in apical extension subsequently undergo swelling, acquiring the characteristic bud-like shape of abortive slaBΔ germlings. Medium shift experiments allowed us to address the role of SlaB in apical extension beyond these early stages of polarity maintenance. We demonstrate the key role that SlaB plays in endocytosis and polarity maintenance, but we also show that deficiency of SlaB affects the actin cytoskeleton.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Aspergillus nidulans techniques.

A. nidulans strains, whose genotypes are detailed in Table 1, carried markers in standard use (11) (http://www.aspgd.org/). slaB1 strains were routinely cultured on 1% (wt/vol) glucose synthetic complete (SC) medium containing 10 mM nitrate as the sole nitrogen source or, alternatively, on Aspergillus complete medium (MCA) supplemented with 50 mM nitrate. SC containing 10 mM ammonium tartrate, which prevents growth of mutant colonies, was used to score the presence of slaB1 in the progeny of meiotic crosses.

Table 1.

Strains used in this work

| Strain | Complete genotype |

|---|---|

| MAD1739 | pyrG89; pyroA4 ΔnkuA::bar |

| MAD1794 | pyrG89; argB2; pyroA4 ΔnkuA::argB; slaB::gfp-pyrGfum |

| MAD2384 | pyrG89; pyroA4 ΔnkuA::bar; slaB1 |

| MAD2434 | pyrG89?; argB2::[argB*-gfp::rabA]?; pyroA4 ΔnkuA?; slaB1; abpA::mRFP-pyrGfum |

| MAD2436 | pyroA4 ΔnkuA?; abpA::mRFP-pyrGfum |

| MAD2556 | pyrG89? pabaA1 yA2; synA::gfp-pyrGfum; pyroA4 ΔnkuA?; slaB1 |

| MAD2674 | pyrG89? pabaA1 yA2; pyroA4 ΔnkuA?; synA::gfp-pyrGfum |

| MAD3041 | pabaA1 yA2; pyroA4::[pyroA*-gpdAmini::gfp::pep12]; slaB1 |

Plasmid and strain constructions.

The niiA promoter used for conditional expression corresponds to the complete intergenic region of the niiA-niaD divergent transcriptional unit as oriented with the direction of transcription toward niiA. p1863 was the source of the linear DNA fragment that was used to replace resident slaB by niiAp::slaB (slaB1). The plasmid is schematically depicted in Fig. 1A. Briefly, a fragment containing 0.72 kbp of the 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) of slaB was PCR amplified using primers Sla1PROM and AM140. This fragment was introduced (as an XhoI-EcoRI fragment) into a pBS-SK(+) plasmid derivative containing (as an EcoRI-SpeI fragment) the A. fumigatus pyrG gene, thus yielding plasmid p5′SlaB::pyrGfum. A chimeric DNA fragment carrying niiAp (considering as such the complete intergenic region of the niiA-niaD divergent transcriptional unit as oriented with the direction of transcription toward niiA) followed by the coding region (including introns) of slaB was assembled by fusion PCR (with primers AM141, AM142, AM143, and Slao13). This fragment was inserted downstream of pyrGfum as an SpeI-NotI fragment and sequenced to verify the absence of mutations. An XhoI-NotI fragment containing the resulting niiAp::slaB transgene was used for transformation of strain MAD1739 (pyrG89; pyroA4 ΔnkuA::bar) (Table 1). As slaB is essential, we selected primary transformants on osmotically stabilized minimal medium without uracil (50) and containing 10 mM nitrate (permissive conditions). Homokaryotic clones were purified from conidiospores of these transformants and tested by replica plating on nitrate and ammonium media. All 25 clones tested showed the phenotype expected for the gene replacement (normal growth on nitrate and no growth on ammonium; we used an nkuAΔ strain to prevent nonhomologous recombination [37]). The presence of the expected gene replacement was confirmed by Southern analysis (not shown). As a control to verify that insertion of pyrGfum at the slaB locus does not impair function, we constructed similarly a strain in which slaB was replaced by a slaB::pyrGfum::3′UTRslaB DNA fragment obtained, as an NcoI-SpeI fragment, from plasmid p1850. Transformants carrying this replacement, which were selected on medium without pyrimidine and containing 5 mM ammonium tartrate as the sole nitrogen source, were indistinguishable from the wild type. For expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-Pep12, we used a plasmid in which the gpdAmini promoter was used to drive expression of A. nidulans Pep12 (genomic version). Details of this plasmid will be given elsewhere. This plasmid was targeted in single copy to the pyroA locus as described previously (40).

Fig. 1.

Experimental design and characterization of the conditional slaB1 allele. (A) Schematic representation of the construct and the double-recombination event use to replace the resident slaB gene by slaB1. (B) Cells carrying slaB1 cannot grow on ammonium medium but grow and sporulate normally on nitrate. (C) Western blot analysis of slaB+ and slaB-gfp cells using anti-SlaB antiserum, demonstrating that this antiserum specifically recognizes SlaB. (D) Western blot analysis of whole-cell extracts obtained by alkaline lysis of slaB+ (wt) and slaB1 cells cultured in synthetic complete medium containing 10 mM nitrate or 40 mM ammonium, as indicated. Actin was used as an equivalent loading control. Note that a very faint band of SlaB is seen in slaB1 cells cultured on ammonium when blots were overexposed (SlaB ↑exp).

Culture conditions for microscopy of slaB1 cells.

Unless otherwise indicated, we routinely used pH 6.5 WMM (41) containing 10 mM nitrate (permissive conditions) or 40 mM NH4Cl (restrictive conditions) as a nitrogen source and 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose (∼11 mM) as a carbon source. However, in medium shift experiments in which hyphae were germinated under permissive conditions before being transferred to restrictive conditions, we used 0.1 to 1 mM nitrate for permissive conditions to avoid carryover contamination due to the use of an unnecessarily high concentration of nitrate during germination. Appropriate controls were set to show that the morphological abnormalities observed were specifically resulting from the shift from nitrate- to ammonium-containing medium. For medium shift experiments, appropriately diluted conidiospore suspensions were inoculated onto 20- by 20-mm coverslips that had been deposited, using sterile tweezers, onto wells of LabTech polystyrene six-well tissue culture plates (Becton-Dickinson, NJ) containing 2.5 ml of 0.1 mM nitrate-WMM. Plates were incubated for 10 to 12 h at 25°C until the average germ tube length of the resulting hyphal cells was at least ∼25 to 50 μm. After this initial period of incubation, coverslips to which hyphae were attached were washed two times with prewarmed (at 25°C) 40 mM NH4Cl-WMM (using suction to remove the medium) before addition of 2.5 ml of the same medium and continuation of incubation for a further 12 to 14 h at 25°C. In controls in which cells that were germinated on 0.1 mM nitrate medium were transferred to the same medium, the second period of incubation was reduced to 6 to 8 h to avoid excessive growth, as these hyphal tips grew normally.

In medium shift experiments in which abnormal cells that were germinated (for 10 h at 25°C) on 40 mM NH4Cl were shifted to permissive conditions, we used 10 mM nitrate for the second incubation period. In this case, controls were set in which cells germinated on ammonium were shifted to the same (ammonium-containing) medium. Unlike cells shifted to nitrate, these cells remained arrested in the early stages of polarity maintenance, resembling cells that had been continuously incubated on ammonium medium.

In medium shift experiments in which ammonium downregulation was combined with latrunculin B (latB) treatment, cells were precultured on 0.1 mM nitrate for 9 to 10 h before being shifted to 40 mM ammonium or, in the case of controls, 10 mM nitrate medium containing 10 or 25 μM latrunculin B (Calbiochem) (from a 10 mM stock in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]; appropriate controls demonstrated that addition of DMSO alone had no effect). After the transfer, cells were incubated for an additional 12 to 14 h before being photographed. These concentrations of latrunculin B permitted germination of slaB1 cells on nitrate and are thus sublethal.

Microscopy.

Epifluorescence microscopy was carried out essentially as described previously, using a Nikon Eclipse 80i or Leica DMI6000 microscope for static and time-lapse sequences, respectively, and a Dual-View beam splitter for simultaneous acquisition of GFP and monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP) channels (19, 40). For confocal microscopy, we used a Leica SP3 or SP5 device with acusto-optical beam splitters, 63× and 1.4-numerical aperture (NA) objectives, and laser lines of 488 nm for GFP and 561 nm for mRFP. These images were processed with Leica software and converted to Metamorph stacks and, when needed, to time-lapse movies using ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Anti-SlaB polyclonal antiserum.

We used the Escherichia coli vector pOPTH (39) to drive high-level expression of a peptide consisting of the 205 C-terminal residues of SlaB, which include the complete I/LWEQ domain. This peptide was fused to an N-terminal hexa-His tag. The peptide was purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography and used to immunize rabbits. E. coli cells carrying pOPTH-I/LWEQ were induced with 0.1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 3 h at 37°C; collected by centrifugation; resuspended in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.5 M NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 1 mM Pefabloc (Roche), 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.05% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, and Roche's protease inhibitors; and lysed using a French press. The resulting lysate was cleared by centrifugation and loaded onto a 5-ml HisTrap-FF column. The peptide was eluted using a linear 40 mM to 500 mM imidazole gradient. Appropriate fractions were pooled, dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and used to immunize rabbits (by Davids Biotechnology GmbH, Regensburg, Germany).

SlaB Western blotting using total protein extracts.

The protocol for SlaB Western blotting is a modification for A. nidulans of the alkaline lysis extraction procedure used for S. cerevisiae (47). Mycelia, cultured under the different growth conditions indicated, were collected by filtration (or by centrifugation in the case of slaB1 cells cultured on ammonium), frozen in dry ice, and lyophilized. Lyophilized cells (in 2-ml screw-cap tubes) were homogenized by using an FP120 Fast Prep cell disruptor and a 0.5-mm ceramic bead, with a 10-s pulse at a setting of 4. Carefully weighted aliquots of powdered biomass (3 to 5 mg per sample) were transferred to Eppendorf tubes, and the proteins were solubilized after addition of 1 ml of lysis solution (0.2 M NaOH and 0.2% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol) per tube. Tubes were vortexed vigorously and maintained on ice for 10 min before proteins were collected by precipitation with 5% (vol/vol) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) followed by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The resulting pellets were resuspended in 1 M Tris base (0.1 ml), mixed with 2 volumes of Laemmli loading buffer, and incubated for 2 min at 100°C. Proteins (2 to 5 μl of each sample) were resolved in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels before being electrotransferred to nitrocellulose filters, which were reacted either with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (raised against the SlaB 206 C-terminal residues) (1/10,000) or, for loading controls, with mouse antiactin monoclonal antibody (1/75,000) (clone C4, ICN Biomedicals Inc.). Peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rabbit (Sigma) antiserum at 1/10,000 and peroxidase conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG immunoglobulin (Jackson) at 1/6,000 were used as a secondary antibodies, respectively. Peroxidase activity was detected with Amersham Biosciences ECL.

RESULTS

A system to construct conditional mutations of essential genes using the niiA promoter.

To manipulate SlaB protein dosage, we chose the well-characterized niiAp (nitrite reductase) promoter for several reasons. First, the regulation of this promoter has been thoroughly studied (5–7, 36, 42). The promoter is repressible by ammonium, which inactivates the wide-domain positively acting transcription factor AreA, and is inducible by nitrate through activation of the pathway-specific, also positively acting, transcription factor NirA (7, 9). Full expression takes place in the absence of ammonium and the presence of nitrate. Second, both nitrate and ammonium are excellent nitrogen sources for A. nidulans. Third, even in the complete absence of AreA (possibly a more extreme condition in terms of reducing expression than the complete repression by ammonium), expression of niiAp is depressed but still inducible (i.e., still responds to nitrate) to a significant extent (42). However, under repressing and noninducing conditions, niiAp expression is virtually nil (42).

An niiAp::slaB cassette containing slaB flanking sequences that was constructed by fusion PCR (48), cloned, and entirely sequenced to rule out the presence of mutations was used to replace the resident slaB gene by homologous recombination under expression-permissive conditions (Fig. 1A) (see Materials and Methods). This slaB allele was denoted slaB1. On synthetic complete (SC) plates, slaB1 strains grew and conidiated normally when the medium contained sodium nitrate as an N source, but they were completely unable to grow when ammonium tartrate was used instead (Fig. 1B; see also below). These data agree with our previous conclusion, based on heterokaryon rescue, that A. nidulans slaB is essential (2).

To monitor SlaB levels by Western blotting under different nutrient conditions, we raised a polyclonal antiserum against its 205-residue C-terminal, actin-interacting I/LWEQ domain (32). This antiserum detected SlaB with high specificity: Fig. 1C shows that in wild-type cells, antibodies react with a protein with the expected Mr for SlaB. This band is absent in a strain expressing endogenously tagged SlaB-GFP, where the antiserum reacts with a lower-mobility band corresponding to the fusion protein.

For determining SlaB levels by Western blotting, it is important to note that we used an adaptation for A. nidulans of the alkaline lysis method designed for S. cerevisiae (47) (see Materials and Methods) to obtain total cell extracts. This method, based on the direct solubilization of the biological material using sodium hydroxide, avoids proteolysis of the antigen and does not require removal of cell debris from lysates. Thus, it is ideally suited for accurate estimation of protein levels because it prevents variability due to the loss of a proportion of the antigen with insoluble fractions, as happens, for example, with SlaB.

In the wild type, using media containing 40 mM ammonium chloride and 10 mM sodium nitrate as fully repressing and inducing conditions for the transgene, respectively, SlaB levels were similar independently of whether the cells had been cultured on nitrate or ammonium. In contrast, in the slaB1 mutant SlaB levels were notably higher than in the wild type under inducing conditions and were virtually undetectable under repressing conditions (Fig. 1D). These data established the validity of the genetic switch for conditional expression.

The terminal phenotype of slaB1.

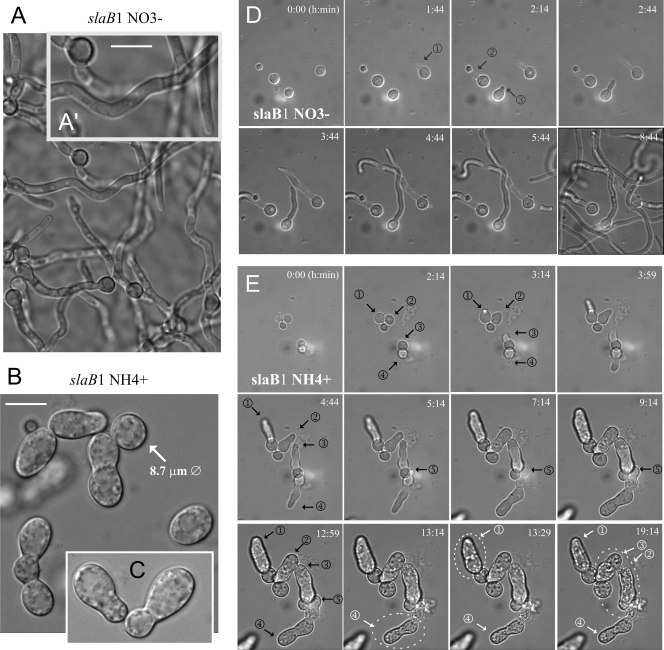

Microscopic observations confirmed that slaB1 conidia germinated normally on 10 mM nitrate (Fig. 2A). Thus, we determined the terminal phenotype of slaB1 after germination in medium containing 40 mM NH4Cl. Under such conditions, mutant spores broke dormancy, underwent isotropic swelling, and, in most cases, were able to establish polarity, but their germ tubes were abnormally wide and arrested in apical extension shortly after their emergence. Thus, slaB is crucially required at early stages of polarity maintenance. As germinated spores showed an abnormally large diameter (the micrographs in Fig. 2A′ and in Fig. 2B and C are at the same magnification), we concluded that SlaB deficiency delays polarity establishment.

Fig. 2.

The terminal phenotype of slaB1. (A) Normal germination of slaB1 spores on 10 mM nitrate medium. The image was taken after overnight incubation at 25°C. (A′) A magnified region of panel A, where the bar indicates 10 μm. (B) Abnormal slaB1 germlings observed after overnight incubation on 40 mM NH4Cl. The diameter of one abnormally swelled spore that had not established polarity is indicated. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Example of the “nose-like” morphotype characteristic of cells germinating on ammonium (at the same magnification as for panels A′ and B). (D) Polarity establishment of slaB1 spores germinating on nitrate. The site of emergence of three germ tubes (numbered) is indicated with arrows. Images represent frames of Movie S1 in the supplemental material and are maximal-intensity projections of z-stacks. (E) Polarity establishment of slaB1 cells cultured on ammonium. (This sequence ought to be consulted together with Movie S2 in the supplemental material, from which the different frames were extracted.) Nascent germ tubes are indicated with black arrows as in panel D. Note that the basal spores continue growing isotropically after establishing polarity and that the relatively normal germ tubes arrest apical extension shortly after their emergence but continue to grow isotropically for some time. However, cells undergo lysis after prolonged incubation. Some examples of cells that undergo lysis are highlighted with white dotted circles, and the time of lysis is indicated by changing their corresponding arrows and numbering from black to white. Images are maximal-intensity projections of z-stacks. Panels D and E are shown at the same magnification.

The most abundant slaB1 morphotype (see also below) was a short germ tube resembling a large bud (Fig. 2C), which is remarkably similar to that of slaBΔ germlings originating from conidiospores rescued from heterokaryons (2). This and the fact that, as seen with slaBΔ spores, the abnormal slaB1 germlings displayed characteristic indentations on their surface (see also below) led us to conclude that under restrictive conditions, slaB1 phenotypically resembles the null allele.

We confirmed that the “nose-like” structures represent abortive germ tubes and not abnormally swelled conidiospores by using time-lapse microscopy. Frames in Fig. 2D, corresponding to Movie S1 in the supplemental material, display the normal pattern of polarity establishment shown by slaB1 conidia germinated on nitrate (time zero of this sequence corresponds to ∼4 h of incubation). Fig. 2E, corresponding to Movie S2 in the supplemental material (which should be consulted for a better understanding of the phenotype), shows several examples of slaB1 conidia that germinated on ammonium. The isotropic growth phase is slightly extended (time zero of this sequence corresponds to ∼5 h of incubation), but, somewhat unexpectedly, the germ tubes that initially emerged were apparently normal. However, after a further 5 h, the growing tips arrested apical extension and grew isotropically. Despite the fact that the basal conidia continued growing isotropically for some time, the width of the arrested germ tubes reached the diameter of their corresponding swelled conidiospores, leading to a characteristic “budding-yeast-like phenotype.” These experiments additionally revealed that some mutant cells undergo lysis upon prolonged incubation under restrictive conditions (Fig. 2E, encircled with dotted lines), further suggesting that the deficiency of SlaB leads to a major morphogenetic defect.

Normal apical extension correlates with the degree of slaB function.

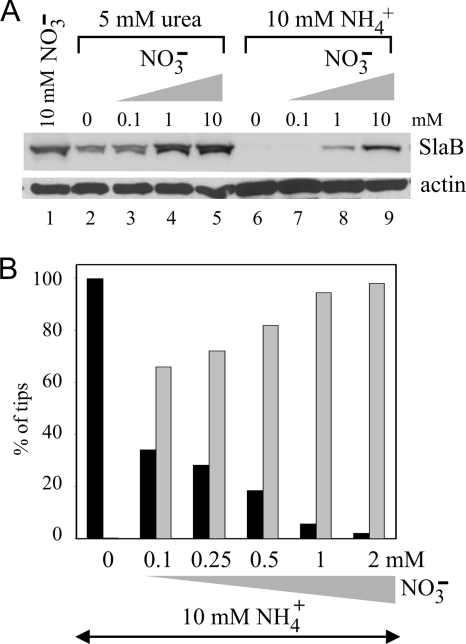

Even in the complete absence of AreA, niiAp is inducible by nitrate (42). We predicted that in slaB1 strains, SlaB levels would be detectably higher under repressed and induced conditions (i.e., on a mixture of both ammonium and nitrate) than under repressed conditions (ammonium only [AreA is inactive]). Western blotting and microscopy confirmed this prediction. Even in the presence of 10 mM ammonium, addition of 1 or 10 mM nitrate led to substantial synthesis of SlaB (Fig. 3A, lanes 8 and 9). However, 1 mM nitrate was clearly suboptimal, and 10 mM nitrate did not fully overcome ammonium repression (the latter condition has been described as “depressed”) (42) (Fig. 3A, compare lines 8 and 9 with lane 1, corresponding to inducing conditions). In contrast, nitrate at 1 mM led to full induction when ammonium was replaced by the nonrepressing nitrogen source urea (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 1, 4, 5, 8, and 9), confirming the repressing effect of ammonium. Nonrepressing, noninducing conditions, as achieved with 5 mM urea in the absence of nitrate, also led to considerable SlaB synthesis (Fig. 3A, lane 2; compare with fully induced levels shown in lane 1, 4, or 5). These data illustrate the versatility of the niiAp driver to achieve different levels of expression.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between normal polarity maintenance and SlaB levels. (A) Western blots of cells cultured on the indicated nitrogen sources. Actin was used as loading control. (B) Proportions of abnormal (“nose-like”) germlings and normal hyphal tips derived from spores germinated and cultured overnight at 25°C in WMM containing 10 mM NH4+ and the indicated concentrations of nitrate. Black and gray bars indicate abnormal germlings and normal tips, respectively.

We next exploited the different degrees of induction achievable in the presence of ammonium to correlate SlaB levels with normal polarity maintenance. Nearly all slaB1 conidiospores in a sample with n = 106 showed wild-type polarity maintenance (i.e., led to normal hyphal tips after overnight incubation at 25°C) when 10 mM ammonium medium was supplemented with 1 mM nitrate (Fig. 3B), conditions under which SlaB synthesis was clearly detectable (Fig. 3A, lane 8). At below 1 mM nitrate, we could not confidently discriminate relatively minor increments in SlaB levels in our Western blots, but we determined by microscopy that addition of as little as 0.1 mM nitrate to ammonium-containing medium sufficed for normal polarity maintenance in >60% of slaB1 nascent tips (n = 44) (Fig. 3B). Importantly, the number of typically aberrant cells seen under semirestrictive conditions decreased and the number of normally polarized tips increased as the concentration of nitrate that was mixed with ammonium was increased, strongly indicating that normal polarity maintenance is crucially dependent on the availability of a sufficient amount of SlaB.

SlaB is required for endocytosis.

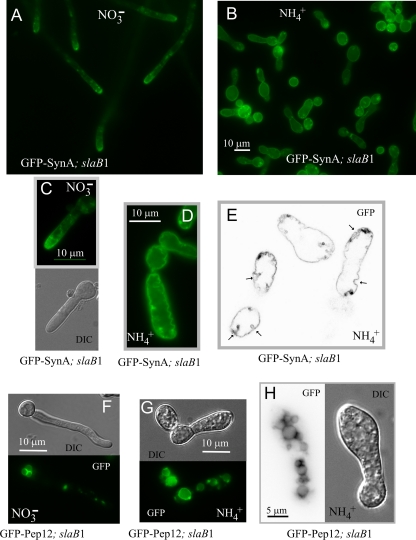

We next determined that slaB1 cells cultured under restrictive conditions are deficient in endocytosis, using the secretory vesicle SNARE SynA (1, 49) as cargo. This integral membrane protein continuously undergoes endocytic recycling (i.e., it is secreted to the apical plasma membrane, endocytosed by the subapical endocytic ring, and redelivered from endosomes to the plasma membrane), which results in a markedly polarized plasma membrane localization (Fig. 4A). In the wild type cultured on either ammonium or nitrate (not shown) and in the slaB1 mutant cultured on nitrate, SynA plasma membrane polarization is noticeable shortly after polarity is established (Fig. 4A and C). In contrast, SynA shows no polarization in slaB1 cells cultured on ammonium, despite the fact that the protein localizes exclusively to the plasma membrane (Fig. 4B and D), demonstrating that the protein does not undergo normal endocytic recycling. Because SynA reaches the plasma membrane efficiently, the inability of slaB1 cells to maintain polarity cannot be attributed to deficient secretion. SynA is a membrane cargo, and thus its turnover requires endocytosis, sorting into multivesicular endosomes, and delivery from these endosomes to the vacuolar lumen for degradation by vacuolar proteases. In addition to the loss of SynA polarization, mutant cells show markedly elevated levels of plasma membrane fluorescence, indicating that the turnover of SynA also is essentially blocked. Thus, slaB1 prevents both the endocytic recycling and the endocytic downregulation of SynA, as expected from the pivotal role that SlaB plays in the endocytic internalization step. In contrast, the vacuolar membrane localization of the Pep12 t-SNARE, which does not need endocytosis because it travels to the vacuole from endosomes without reaching the plasma membrane, is unaffected (Fig. 4F, G, and H). Thus, the virtually complete absence of SlaB prevents endocytosis.

Fig. 4.

Abolishment of SynA endocytic recycling by SlaB downregulation. (A) slaB1 hyphae on nitrate, showing normal, polarized plasma membrane localization of SynA. (B) A general view of slaB1 cells after overnight incubation on ammonium at 25°C. (C) slaB1 germling cultured on nitrate for 9 h, showing that SynA polarization is already conspicuous at this early stage of polarity maintenance. (D) slaB1 cell cultured overnight on ammonium. SynA is not polarized, and the SynA-GFP-labeled plasma membrane is ruffled. Panels C and D are at the same magnification. (E) Confocal image of SynA-GFP (inverted contrast) showing the large cavities that are formed when slaB1 cells are cultured on ammonium. This plane is a frame of Movie S3 in the supplemental material, which should be consulted to fully appreciate the size of these cavities. (F) slaB1 germling expressing GFP-Pep12, cultured on nitrate. GFP-Pep12 localizes to the vacuolar membrane and endosomes. (G) slaB1 germling expressing GFP-Pep12, cultured on ammonium. GFP-Pep12 localizes to the vacuolar membrane as on nitrate, but the abnormal cells show enlarged vacuoles. (H) Another example of a slaB1 germling expressing GFP-Pep12 that had been cultured on ammonium. It shows extensive vacuolization.

GFP-SynA labeling revealed that the plasma membrane was utterly deformed in these cells that were almost completely deficient in SlaB, which presented deep irregular invaginations of the plasma membrane that could be better resolved by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4E shows a single section, but see Movie S3 in the supplemental material, showing tubular structures across the different sections, to appreciate the large size of these invaginations). These invaginations almost certainly account for the characteristic fenestrated aspect of the cell surface seen in Nomarski images of cells lacking SlaB (reference 2 and this work). In S. cerevisiae, Sla2p regulates actin polymerization during internalization of the endocytic vesicle, perhaps by preventing excessive Arp2/3-dependent polymerization of actin at endocytic sites (26). The primary endocytic pits in yeast are tubular invaginations of up to 180 nm in depth (24), and thus it is tempting to speculate that the nearly complete deficit of SlaB results in excessive polymerization of F-actin, leading to hypertrophy of equivalent A. nidulans endocytic invaginations. It has also been reported that an S. cerevisiae mutant with a myo5 missense mutation leading to defective fluid-phase endocytosis shows a large number of deep invaginations of the plasma membrane (25).

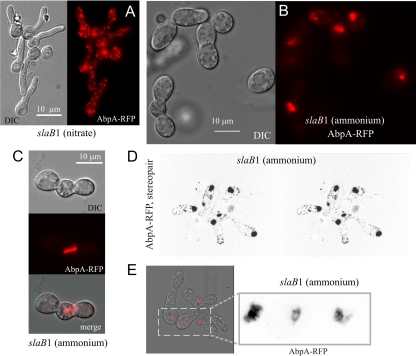

Major disturbance of F-actin by SlaB deficiency.

We next addressed the effects of downregulating SlaB on the organization of F-actin at endocytic sites, using AbpA as a reporter (AbpA does not label actin cables). As in the wild type (2), AbpA is seen in cortical patches in slaB1 germlings cultured under inducing conditions (Fig. 5A). In contrast, when slaB1 cells were cultured under repressing conditions, the reporter weakly labeled a peripheral mesh but largely predominated in strongly fluorescent aggregates (Fig. 5B and D; see Movie S4 in the supplemental material, showing a three-dimensional [3D] reconstruction). Large AbpA clusters often formed rod-like structures (Fig. 5C), somewhat resembling S. cerevisiae “comets” seen with Abp1 in sla2Δ cells (26). However, S. cerevisiae comets are very abundant and originate at the cortex, whereas AbpA aggregates are usually one, at most two, per germling and are not associated with the cortex. Confocal imaging revealed that in some examples these AbpA aggregates look like fenestrated structures (Fig. 5E). As noted above, Sla2/HipR proteins coordinate actin polymerization with the endocytic machinery (13, 26). Sla2p possibly inhibits cortical Arp2/Arp3-dependent F-actin assembly (22). Thus, unrestrained F-actin polymerization plausibly underlies the formation of these large AbpA aggregates.

Fig. 5.

SlaB downregulation results in formation of large AbpA clumps. (A) Wide-field epifluorescence and differential interference contrast (DIC) images of slaB1 germlings cultured on nitrate. (B) Wide-field images of slaB1 cells cultured on ammonium. (C) Confocal images showing a long AbpA-mRFP rod extending from a basal conidiospore into an abnormal germ tube of a slaB1 cell cultured on ammonium. (D) Stereopair image extracted from a 3D reconstruction (see Movie S4 in the supplemental material) of an mRFP channel confocal z-stack (inverted contrast), displaying a group of slaB1 cells cultured on ammonium. (E) Confocal images showing examples of fenestrated structures seen with AbpA-mRFP in slaB1 cells cultured on ammonium. Left, merge of the DIC and mRFP channels. Right, enlarged section of the mRFP image shown in inverted contrast.

Reversibility of the effects of slaB1.

We carried out medium shift experiments to demonstrate reversibility. slaB1 spores were cultured on ammonium, and the resulting cells arrested in apical extension were shifted to medium containing 10 mM nitrate. If the time of the initial incubation on ammonium was extended beyond 14 h, only a minor proportion of the population of abnormal germlings gave rise to normal germ tubes after the shift to nitrate. Among 35 randomly photographed examples of these new germ tubes, 34% showed slight morphological abnormalities without marked SynA polarization. These findings almost certainly reflect the fact that abnormal slaB1 cells progressively lose viability upon incubation on ammonium (see above [Fig. 2]). Indeed, if the length of the initial incubation period on ammonium was reduced to 10 h, virtually every abnormal slaB1 germling gave rise to one or more morphologically normal polarity axes after 6 to 8 h from the shift to nitrate (Fig. 6). In each and every case these normal hyphae showed wild-type GFP-SynA polarization (Fig. 6), indicating that normal apical extension correlates with resumption of SynA endocytosis. GFP-SynA fluorescence in the plasma membranes of the normal tips “induced” by nitrate was markedly weaker than that in their “mother” cells that had germinated under restrictive conditions (data not shown), in agreement with the contention that the “emerging” normal tip cells had reassumed the endocytic turnover of the v-SNARE.

Fig. 6.

Reversibility of the polarity maintenance-arrested phenotype resulting from SlaB downregulation. (Top) Nomarski and epifluorescence image of an abnormal GFP-SynA germling cultured on ammonium medium for 10 h. (Bottom) Wide-field epifluorescence images of GFP-SynA and the corresponding Nomarski (DIC) image of slaB1 cells cultured on ammonium for 10 h and shifted to nitrate conditions for an additional 8-h period. The image shows several morphologically normal tips emerging from “mother” cells and the inverted contrast epifluorescence images of the indicated areas demonstrating normal GFP-SynA polarization.

The “new” normal-polarity axes induced by nitrate were never seen in control cells incubated on ammonium and shifted to ammonium (data not shown), demonstrating that these emerging hyphae reflect resumption of normal polarity maintenance/SynA endocytic recycling when SlaB synthesis is restored by nitrate.

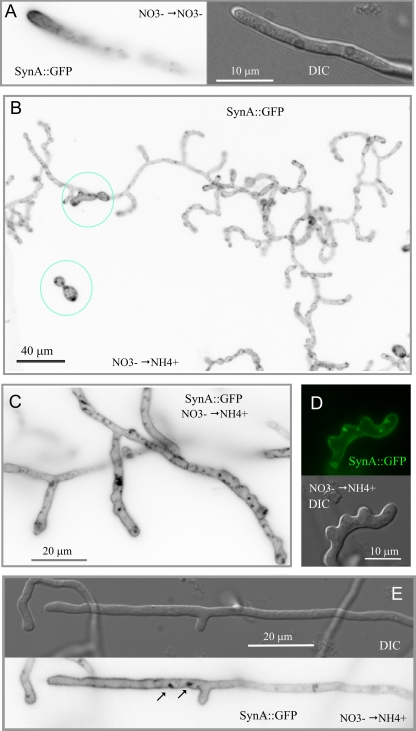

SlaB is crucially involved in polarity maintenance in hyphae.

The experiments described above demonstrated that SlaB is required for apical extension shortly after polarity establishment and showed that the proportion of tips undergoing normal apical extension appears to correlate with SlaB levels. These data would be consistent with two possible scenarios: (i) SlaB is exclusively required during an “early” stage of polarity maintenance but becomes dispensable after this stage, once the tip growth apparatus is set in place (see Discussion for more rationale), or (ii) SlaB is also required for polarity maintenance in hyphae. To address its involvement in maintaining polarity once germlings progress beyond the emergence of the germ tube, we used nitrate conditions (0.1 mM nitrate) permitting SlaB synthesis during the first 10 to 12 h of slaB1 spore germination and subsequently shut off the promoter by shifting these cells to high-ammonium conditions. The terminal phenotype of these cells was determined after an additional overnight incubation. We set up controls in which slaB1 cells germinated on 0.1 mM nitrate were shifted to nitrate medium. These cells gave rise to hyphae with normal (i.e., wild-type) tips and GFP-SynA polarization (Fig. 7A). In contrast, microscopic analysis of the population of cells shifted from nitrate to ammonium led to the following conclusions. First and most important, cells undergoing this regimen grew and maintained polarity far beyond the “bud-like” stage at which control cells that had germinated on ammonium arrested, in agreement with the conclusion that SlaB is required during the early stages of polarity maintenance (Fig. 7B [two cells showing the “early” polarity-arrested phenotype that possibly germinated after shutting off the promoter are circled for comparison]). Figure 7B also shows that the predominating morphotype consists of hyperbranched hyphae showing abnormally wide diameters. The large majority of the primary and secondary tips in these abnormal hyphae were bulged, and, very frequently, hyphal tubes had a “ruffled” aspect near the tips, with abundant small heaps poking up that appear to represent abortive events of subapical branching (Fig. 7C), such that some tips showed a characteristic “deer antler” shape (Fig. 7D). Thus, these experiments strongly support the contention that SlaB is crucially required for polarity maintenance also in hyphae. Abnormal (shifted-to-ammonium) hyphae also showed a completely uniform distribution of GFP-SynA across their whole length (Fig. 7B to D) and contained accumulations of GFP-SynA corresponding to large invaginations of the plasma membrane resembling those seen in cells directly germinated on ammonium (see above). Both the lack of SynA polarization and these accumulations were also seen even in those hyphae that, although still showing abnormal subapical branching and a certain degree of tip swelling, were more normal morphologically (Fig. 7E). Thus, we concluded that in cells shifted to ammonium SlaB had been downregulated to a level insufficient to support normal endocytosis and thus that deficient apical extension correlates with deficient endocytosis.

Fig. 7.

Medium shift experiments showing that SlaB is required for polarity maintenance and endocytosis in hyphae. (A) Nomarski and epifluorescence (in inverted contrast) images of a slaB1 hyphal tip cell expressing GFP-SynA, germinated for 10 h on 0.1 mM nitrate medium and shifted to the same medium for additional incubation. Note the normal hyphal polarization of GFP-SynA correlating with normal hyphal morphology. (B) Large epifluorescence microscopy field (GFP channel, inverted contrast) of slaB1 cells that had been germinated on nitrate medium before being shifted to ammonium medium. Note the abnormal branching and morphology of the hyphae and the abnormally swollen hyphal tips. The two cells circled in blue represent two spores that appeared to be in an early stage of germination when the culture was shifted to repressing conditions (note that germination is not synchronous). (C) Enlarged details of slaB1 tips (GFP-SynA fluorescence, inverted channel) corresponding to cells germinated on nitrate medium and shifted to ammonium conditions. Note the abnormally swollen tips, the GFP-SynA accumulations, and the “ruffled” aspect of the hyphal tubes. (D) Enlarged slaB1 tip (Nomarski and GFP-SynA fluorescence channels) from a culture germinated on nitrate medium and shifted to ammonium conditions. Note the emergence of subapical, consecutive, and seemingly abortive branch primordia and the plasma membrane invaginations seen with GFP-SynA when endocytosis is deficient. (E) A hyphal tip (Nomarski and GFP-SynA fluorescence channels) from a culture germinated on nitrate medium and shifted to ammonium conditions. Note the swollen tip, the abnormal occurrence of a branch in a hyphal tip compartment, and the presence of two plasma membrane invaginations near the base of this branch.

F-actin phenotype in slaB1 hyphae shifted to repressing conditions.

Some of morphological abnormalities described above somewhat resembled the effects of misregulating F-actin at the A. nidulans tip region (53). As noted above, abnormal germlings germinated on ammonium (and therefore almost totally devoid of SlaB) frequently show “chunks” of actin/AbpA. Thus, we observed by epifluorescence microscopy slaB1 cells expressing AbpA-mRFP that had been subjected to the medium shift (i.e., nitrate-to-ammonium) protocol described above. In control experiments in which slaB1 cells germinated on nitrate were shifted to nitrate, hyphae were morphologically normal and AbpA-mRFP patches were polarized at the tip region (Fig. 8A) (2). In marked contrast, slaB1 AbpA-mRFP cells germinated for 12 h on nitrate medium and subsequently shifted to ammonium medium closely resembled their slaB1 GFP-SynA counterparts subjected to the same nutritional regime in their hyperbranching and in that they also showed abnormally wide germ tubes and swollen tips (Fig. 8B to E). This indicates that these strong morphological phenotypes cannot be attributed to the fluorescent reporters. In some swollen tips, slaB1 AbpA-mRFP patches, although often obscured by strongly fluorescent AbpA clumps (see below), were abnormally numerous (Fig. 8B). Abnormally abundant AbpA-mRFP patches are also noticeable in A. oryzae hyphae downregulated for SlaBEnd4 (20). However, the most noticeable aspect of the AbpA-mRFP distribution in these cells is the presence of bright clumps of AbpA-mRFP (Fig. 8C to E). These clumps were often associated with abnormal tips (Fig. 8D and E) but could be found elsewhere across the hyphal germ tube and in the bases of swollen tips of branches (Fig. 8C). These clumps of AbpA have not been observed in A. oryzae, perhaps because our repressed slaB1 allele is able to downregulate protein levels to a greater extent than the thiA promoter-based system used with A. oryzae (20). In any case, our data above show that the nearly complete deficiency of SlaB leads to an important major disturbance of the actin cytoskeleton.

Fig. 8.

Disturbance of the actin cytoskeleton in slaB1 hyphae germinated on nitrate and shifted to repressing conditions. (A) Nomarski and epifluorescence (in inverted contrast) images of a slaB1 hyphal tip cell expressing AbpA-mRFP that had been germinated for 12 h on nitrate medium before being shifted to the same medium for additional incubation. (B) A nascent branch showing bright accumulations of AbpA-mRFP (inverted contrast) and numerous less fluorescent AbpA-mRFP patches. (C) Abnormal branches in a hyphal region distant from the tip. Clumps of AbpA-mRFP (inverted contrast) are indicated by arrows. (D) Dichotomous tip with a large accretion of AbpA-mRFP. (E) Large field showing the general disruption of the actin cytoskeleton as seen with AbpA-mRFP. AbpA-mRFP clumps associated with tips are indicated by arrows.

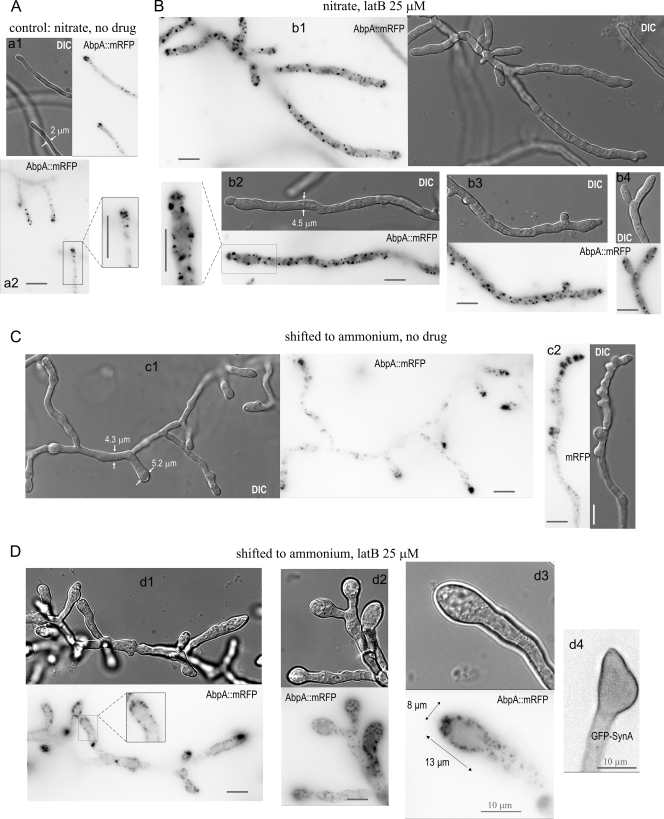

As F-actin is required for apical extension, one possible explanation for the polarity defect of downregulated slaB1 tip cells would be that key F-actin regulators are sequestered in the actin clumps. To gain insight into this possibility, we used latrunculin B (latB), a drug which prevents polymerization of actin monomers (34). In previous work we showed that 100 μM latB disassembles endocytic patches and prevents apical extension (2, 40, 49). At 10 to 25 μM, latB impairs growth but, under SlaB-sufficient (nitrate) conditions, does not preclude the formation of hyphae (Fig. 9B). As expected, these hyphae showed polarity maintenance defects, with bulged and often dichotomous tips (Fig. 9B). They also showed prominent actin patches, demonstrating that actin polymerization is not fully prevented under these conditions, although at 25 μM these patches were fully depolarized (compare Fig. 9A and B). Notably, incubation in the presence of latB led to a marked increase in hyphal tube width, leading to “giant” cells (Fig. 9A and B are shown at the same magnification; panels a2 in Fig. 9A and b2 in Fig. 9B are also equally enlarged).

Fig. 9.

Effect of sublethal latrunculin B treatment in cells downregulated for SlaB. (A) Nomarski and epifluorescence (in inverted contrast) images of a slaB1 hyphal tip cell expressing AbpA-mRFP cultured for 10 h on 10 mM nitrate medium and shifted to the same medium for an additional 13 to 14 h of incubation. The inset in panel a2 was enlarged at double magnification to show the endocytic internalization collar. (B) Examples of slaB1 cells cultured for 10 h on 10 mM nitrate medium and shifted to the same medium containing 25 μM latrunculin B. b1, a large field; b2, the inset was enlarged at double magnification to facilitate direct comparison with a2; b3, a branch near the tip; b4, a dichotomous tip. (C) Examples of slaB1 cells cultured for 10 h on 10 mM nitrate medium and shifted to ammonium medium without latrunculin B. c1, a hypha which had undergone multiple branching events; c2, a hyphal tip cell with characteristic “deer antler” morphology. (D) Examples of slaB1 cells cultured for 10 h on 10 mM nitrate medium and shifted to ammonium medium containing 25 μM latrunculin B. Cells were expressing either AbpA-mRFP or GFP-SynA, as indicated. d1, a large cell; d2, examples of globular tips; d3, middle plane of a globular tip showing cortical comet-like structures of AbpA-mRFP, corresponding to Movie S5 in the supplemental material; d4, globular tip showing the plasma membrane localization of SynA. In all panels, scale bars indicate 10 μm.

We next used latB in slaB1 cells downregulated by ammonium. In agreement with the mechanism of latB action, the drug markedly decreased the formation of actin clumps (Fig. 9D) such that, at 25 μM, these were either absent or markedly less prominent in a major proportion of the tips (Fig. 9D, panel d1). These SlaB-downregulated and latB-treated cells also showed a very notable increase in the proportion of cortical actin patches, apparently at the expense of actin “clumps” (compare Fig. 9C and D). In this hyperabundance of actin patches, these cells resemble S. cerevisiae sla2Δ mutants (22). SlaB downregulation and latB treatment showed additivity, resulting in an stronger effect on the morphology of the tips than either alone (Fig. 9D). For example, many tips formed large bubbles densely populated by cortical actin patches (Fig. 9D, panels d2 and d3). These “bubbles” were never seen in cells treated with latB only or shifted to ammonia only. As expected, tip bubbles do not internalize GFP-SynA (Fig. 9D, panel d4). Thus, the finding that latB interferes with the formation of actin clumps without reverting the polarity defects resulting from SlaB downregulation would support the view that the endocytic defect itself rather than the sequestering of actin regulators in actin clumps is responsible for the morphological abnormalities. However, these experiments should be interpreted with caution, as the additive effect of the two treatments could reflect that either alone leads to a deficit of actin monomers which would be worsened by their combination, thereby preventing apical extension.

In any case, the finding that latB prevents the formation of actin clumps in SlaB-deficient cells supports the view that Sla2/SlaB restrains excessive actin polymerization at endocytic patches (26). Unexpectedly, time-lapse imaging of patches in SlaB-deficient tips treated with latB (Fig. 9D, panel d3; see Movie S5 in the supplemental material) revealed that AbpA forms comet-like structures resembling those observed in S. cerevisiae sla2Δ mutants (26). Like their yeast counterparts, AbpA comet-like structures are attached to the cortex in one end, with the other waving in the cytoplasm (see Movie S5 in the supplemental material). These comet-like structures presumably result from the uncoupling of actin polymerization and vesicle formation at endocytic sites (26). It is tempting to speculate that in latB-untreated cells, actin clumps rather than comets are formed when SlaB is downregulated due to the high local levels of unrestrained actin polymerization associated with the A. nidulans hyphal tip, which is densely populated by endocytic patches.

DISCUSSION

For A. nidulans and Ustilago maydis, evidence strongly suggests that endocytosis is intimately associated with hyphal tip growth (2, 30, 45, 46, 49, 51). However, the actual contribution of endocytosis to apical extension remains to be clarified.

A combination of localized apical delivery coupled to slow diffusion and rapid endocytic recycling suffices to generate polarity (31, 49, 52, 54). Thus, one attractive although hypothetical possibility is that A. nidulans uses endocytosis to maintain the dynamic localization of a membrane polarity landmark(s) (51). One plausible candidate would be A. nidulans Cdc42 (31). Although A. nidulans Cdc42 is dispensable for polarity maintenance because its roles may be partially redundant with those of Rac1 (a Rac1 orthologue is absent in S. cerevisiae), Cdc42 misregulation leads to polarity establishment and maintenance defects (53).

Cells cultured on ammonium and thus deficient for SlaB can establish polarity and arrest shortly after germ tube emergence. Although these cells still contain minute levels of SlaB, this phenotype resembles the null phenotype (2). It is important to note that a homozygous null sla2 mutant of the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans, which can grow as yeast, cannot form hyphae (3). Thus, that report and our data strongly indicate that slaB/SLA2 is important for apical extension during hyphal morphogenesis.

The very strong, depolarized GFP-SynA plasma membrane fluorescence seen in slaB1 cells germinated on ammonium demonstrates that they are fully deficient in endocytosis and, in passing, that SlaB is not required for traffic from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane. It is not required for biosynthetic traffic from the Golgi apparatus to the endosomal system either, as the endosomal t-SNARE Pep12 also reaches its normal locale at the vacuolar membrane under repressing conditions. This is an important control because in mammals Hip1R is involved in the traffic of Golgi-derived vesicles bound to the endosomal system (10). Shift-up experiments demonstrated that the endocytic and polarity maintenance phenotypes are fully reversible and that normal hyphal tip morphology essentially correlates with recovery of SynA turnover.

Markedly slower apical extension of germlings compared to hyphae indicates that these two “cell types” differ substantially (23). The fact that germlings can establish and maintain polarity in the absence of microtubules (MTs) (38) suggests that transport of secretory materials to their growing tips is mediated by actin microfilaments. We thus considered the possibility that the failure of slaB1 germlings to maintain polarity could involve a “general” role of SlaB in F-actin regulation. If secretion coupled to endocytic recycling were required to create and maintain an apical domain containing, for example, the actin microfilament organizer Cdc42, short germlings could be more crucially dependent on an actin regulatory function of SlaB for maintaining polarity than hyphae, because secretory vesicle transport would be less dependent on the actin cytoskeleton in the latter, where the MT cytoskeleton has been set in place. However, shift-down experiments showed that this is not the case, as SlaB is required for normal apical extension even when hyphal tips have progressed well beyond germlings. SlaB downregulation in hyphae results in hyperbranching and formation of markedly swelled, abnormal hyphal tips. The complete absence of SynA polarization and the strong labeling of the plasma membrane observed across the whole length of these hyphae is indicative of deficient endocytosis. Therefore, correlation between normal hyphal tip growth and efficient endocytosis appears to indicate strongly that the latter plays an important role in polarity maintenance.

However, although this conclusion appears to be firmly established, it should be taken with some caution. Thus far, genetic evidence supporting the role of endocytosis in hyphal tip growth is based on the inactivation of endocytic genes with F-actin regulation capabilities. Abnormal germlings that had been cultured on ammonium contain large aggregates of F-actin, visualized with fluorescently tagged AbpA. Similar F-actin accumulations were eventually observed near the hyphal tips and branches of hyphae that showed typical polarity defects upon SlaB downregulation. Thus, although this and work with A. oryzae (20) unequivocally establish that SlaBSla2 is required for endocytosis, we cannot formally rule out that in addition to endocytosis, F-actin misregulation also contributes to the polarity maintenance defects displayed by slaB1 cells.

S. cerevisiae Sla2p (26, 55), which is essential for endocytosis, is thought to inhibit Arp2/3-mediated F-actin polymerization driving actin patch internalization until a signal releases its inhibitory effect (26), in agreement with the finding that the Sla2p mammalian orthologue Hip1R, in complex with cortactin, prevents actin filament “barbed end elongation” (29). Thus, unrestrained actin polymerization due to the absence of SlaB may have consequences beyond endocytosis. For example, S. cerevisiae sla2 mutations suppress the hyperabundance of actin cables resulting from a formin-deregulated mutant, possibly by depleting actin monomers (56). Hyphae downregulated for SlaB contain numerous septae (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), and 38 out of 88 abnormal germlings directly germinated on ammonium presented a basal septum, which argues strongly against actin monomer deficiency being the underlying cause of the defective polarity maintenance (septation is F-actin dependent). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that actin/AbpA clumps titrate a key actin-regulatory factor which is required to organize actin microfilaments elsewhere (for example, in the Spitzenkörper).

Abortive SlaB-deficient germlings display very large and deep invaginations of the plasma membrane. It is tempting to speculate that the absence of SlaB leads to excessive F-actin polymerization in association with endocytic patches, thus driving these deep invaginations of the plasma membrane. If this is true, these large structures would be ideally suited to gain insight into the ordered pathway leading to endocytic vesicle internalization (27), using immunoelectron microscopy (24).

Finally, our method to generate conditional expression alleles should be of general applicability to investigate the functions of essential A. nidulans genes. Our system has, we believe, significant technical advantages over those already in use, including a very low level of expression under repressing conditions, the possibility of fine-tuning the levels of synthesis, and, importantly, the fact that both the physiological inducer and the repressor are favorable nitrogen sources.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants MCIN BIO2009-07281 and Comunidad de Madrid SAL/0246/2006 to M.A.P.

We thank Elena Reoyo for technical assistance, Joseph Strauss for advice on the regulation of the promoter, and Herb Arst for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 6 August 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abenza J. F., Pantazopoulou A., Rodríguez J. M., Galindo A., Peñalva M. A. 2009. Long-distance movement of Aspergillus nidulans early endosomes on microtubule tracks. Traffic 10:57–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araujo-Bazán L., Peñalva M. A., Espeso E. A. 2008. Preferential localization of the endocytic internalization machinery to hyphal tips underlies polarization of the actin cytoskeleton in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 67:891–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asleson C. M., Bensen E. S., Gale C. A., Melms A. S., Kurischko C., Berman J. 2001. Candida albicans INT1-induced filamentation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae depends on Sla2p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1272–1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berepiki A., Lichius A., Shoji J. Y., Tilsner J., Read N. D. 2010. F-actin dynamics in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 9:547–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger H., Basheer A., Bock S., Reyes-Dominguez Y., Dalik T., Altmann F., Strauss J. 2008. Dissecting individual steps of nitrogen transcription factor cooperation in the Aspergillus nidulans nitrate cluster. Mol. Microbiol. 69:1385–1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger H., Pachlinger R., Morozov I., Goller S., Narendja F., Caddick M., Strauss J. 2006. The GATA factor AreA regulates localization and in vivo binding site occupancy of the nitrate activator NirA. Mol. Microbiol. 59:433–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernreiter A., Ramón A., Fernandez-Martinez J., Berger H., Araujo-Bazán L., Espeso E. A., Pachlinger R., Gallmetzer A., Anderl I., Scazzocchio C., Strauss J. 2007. Nuclear export of the transcription factor NirA is a regulatory checkpoint for nitrate induction in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:791–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breakspear A., Langford K. J., Momany M., Assinder S. J. 2007. CopA:GFP localizes to putative Golgi equivalents in Aspergillus nidulans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 277:90–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burger G., Strauss J., Scazzocchio C., Lang B. F. 1991. nirA, the pathway-specific regulatory gene of nitrate assimilation in Aspergillus nidulans, encodes a putative GAL4-type zinc finger protein and contains four introns in highly conserved positions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:5746–5755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carreno S., Engqvist-Goldstein A. E., Zhang C. X., McDonald K. L., Drubin D. G. 2004. Actin dynamics coupled to clathrin-coated vesicle formation at the trans-Golgi network. J. Cell Biol. 165:781–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clutterbuck A. J. 1993. Aspergillus nidulans, p. 3.71–3.84 InO'Brien S. J. (ed.), Genetic maps. Locus maps of complex genomes, vol. 3 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa R., Warren D. T., Ayscough K. R. 2005. Lsb5p interacts with actin regulators Sla1p and Las17p, ubiquitin and Arf3p to couple actin dynamics to membrane trafficking processes. Biochem. J. 387:649–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engqvist-Goldstein A. E., Zhang C. X., Carreno S., Barroso C., Heuser J. E., Drubin D. G. 2004. RNAi-mediated Hip1R silencing results in stable association between the endocytic machinery and the actin assembly machinery. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:1666–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harispe L., Portela C., Scazzocchio C., Peñalva M. A., Gorfinkiel L. 2008. Ras GAP regulation of actin cytoskeleton and hyphal polarity in Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell 7:141–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris S. D. 2006. Cell polarity in filamentous fungi: shaping the mold. Int. Rev. Cytol. 251:41–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris S. D., Momany M. 2004. Polarity in filamentous fungi: moving beyond the yeast paradigm. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41:391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris S. D., Morrell J. L., Hamer J. E. 1994. Identification and characterization of Aspergillus nidulans mutants defective in cytokinesis. Genetics 136:517–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris S. D., Read N. D., Roberson R. W., Shaw B., Seiler S., Plamann M., Momany M. 2005. Polarisome meets Spitzenkorper: microscopy, genetics, and genomics converge. Eukaryot. Cell 4:225–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hervás-Aguilar A., Rodríguez-Galan O., Galindo A., Abenza J. F., Arst H. N., Jr., Peñalva M. A. 2010. Characterization of Aspergillus nidulans DidBDid2, a non-essential component of the multivesicular body pathway. Fungal Genet. Biol. 47:636–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higuchi Y., Shoji J. Y., Arioka M., Kitamoto K. 2009. Endocytosis is crucial for cell polarity and apical membrane recycling in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Eukaryot. Cell 8:37–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hohmann-Marriott M. F., Uchida M., van de Meene A. M., Garret M., Hjelm B. E., Kokoori S., Roberson R. W. 2006. Application of electron tomography to fungal ultrastructure studies. New Phytol. 172:208–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holtzman D. A., Yang S., Drubin D. G. 1993. Synthetic-lethal interactions identify two novel genes, SLA1 and SLA2, that control membrane cytoskeleton assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 122:635–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horio T., Oakley B. R. 2005. The role of microtubules in rapid hyphal tip growth of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:918–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Idrissi F. Z., Grotsch H., Fernandez-Golbano I. M., Presciatto-Baschong C., Riezman H., Geli M. I. 2008. Distinct acto/myosin-I structures associate with endocytic profiles at the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 180:1219–1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jonsdottir G. A., Li R. 2004. Dynamics of yeast myosin I: evidence for a possible role in scission of endocytic vesicles. Curr. Biol. 14:1604–1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaksonen M., Sun Y., Drubin D. G. 2003. A pathway for association of receptors, adaptors, and actin during endocytic internalization. Cell 115:475–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaksonen M., Toret C. P., Drubin D. G. 2005. A modular design for the clathrin- and actin-mediated endocytosis machinery. Cell 123:305–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambert A. A., Perron M. P., Lavoie E., Pallotta D. 2007. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Arf3 protein is involved in actin cable and cortical patch formation. FEMS Yeast Res. 7:782–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Clainche C., Pauly B. S., Zhang C. X., Engqvist-Goldstein A. E., Cunningham K., Drubin D. G. 2007. A Hip1R-cortactin complex negatively regulates actin assembly associated with endocytosis. EMBO J. 26:1199–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S. C., Schmidtke S. N., Dangott L. J., Shaw B. D. 2008. Aspergillus nidulans ArfB plays a role in endocytosis and polarized growth. Eukaryot. Cell 7:1278–1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marco E., Wedlich-Soldner R., Li R., Altschuler S. J., Wu L. F. 2007. Endocytosis optimizes the dynamic localization of membrane proteins that regulate cortical polarity. Cell 129:411–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCann R. O., Craig S. W. 1997. The I/LWEQ module: a conserved sequence that signifies F-actin binding in functionally diverse proteins from yeast to mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.U. S. A. 94:5679–5684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Momany M. 2002. Polarity in filamentous fungi: establishment, maintenance and new axes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:580–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morton W. M., Ayscough K. R., McLaughlin P. J. 2000. Latrunculin alters the actin-monomer subunit interface to prevent polymerization. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:376–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moseley J. B., Goode B. L. 2006. The yeast actin cytoskeleton: from cellular function to biochemical mechanism. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:605–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muro-Pastor M. I., Gonzalez R., Strauss J., Narendja F., Scazzocchio C. 1999. The GATA factor AreA is essential for chromatin remodelling in a eukaryotic bidirectional promoter. EMBO J. 18:1584–1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nayak T., Szewczyk E., Oakley C. E., Osmani A., Ukil L., Murray S. L., Hynes M. J., Osmani S. A., Oakley B. R. 2006. A versatile and efficient gene targeting system for Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 172:1557–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oakley B. R., Morris N. R. 1980. Nuclear movement is β-tubulin-dependent in Aspergillus nidulans. Cell 19:255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obita T., Saksena S., Ghazi-Tabatabai S., Gill D. J., Perisic O., Emr S. D., Williams R. L. 2007. Structural basis for selective recognition of ESCRT-III by the AAA ATPase Vps4. Nature 449:735–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pantazopoulou A., Peñalva M. A. 2009. Organization and dynamics of the Aspergillus nidulans Golgi during apical extension and mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 20:4335–4347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peñalva M. A. 2005. Tracing the endocytic pathway of Aspergillus nidulans with FM4-64. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42:963–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Punt P. J., Strauss J., Smit R., Kinghorn J. R., van den Hondel C. A. M. J. J., Scazzocchio C. 1995. The intergenic region between the divergently transcribed niiA and niaD genes of Aspergillus nidulans contains multiple NirA binding sites which act bidirectionally. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5688–5699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharpless K. E., Harris S. D. 2002. Functional characterization and localization of the Aspergillus nidulans formin SEPA. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:469–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smaczynska-de Rooij I. I., Costa R., Ayscough K. R. 2008. Yeast Arf3p modulates plasma membrane PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels to facilitate endocytosis. Traffic 9:559–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinberg G. 2007. Hyphal growth: a tale of motors, lipids and the Spitzenkorper. Eukaryot. Cell 6:351–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinberg G. 2007. On the move: endosomes in fungal growth and pathogenicity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:309–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stimpson H. E., Lewis M. J., Pelham H. R. 2006. Transferrin receptor-like proteins control the degradation of a yeast metal transporter. EMBO J. 25:662–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szewczyk E., Nayak T., Oakley C. E., Edgerton H., Xiong Y., Taheri-Talesh N., Osmani S. A., Oakley B. R. 2006. Fusion PCR and gene targeting in Aspergillus nidulans. Nat. Protoc. 1:3111–3120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taheri-Talesh N., Horio T., Araujo-Bazán L., Dou X., Espeso E. A., Peñalva M. A., Osmani S. A., Oakley B. R. 2008. The tip growth apparatus of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Biol. Cell 19:1439–1449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tilburn J., Scazzocchio C., Taylor G. G., Zabicky-Zissman J. H., Lockington R. A., Davies R. W. 1983. Transformation by integration in Aspergillus nidulans. Gene 26:205–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Upadhyay S., Shaw B. D. 2008. The role of actin, fimbrin and endocytosis in growth of hyphae in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 68:690–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valdez-Taubas J., Pelham H. R. 2003. Slow diffusion of proteins in the yeast plasma membrane allows polarity to be maintained by endocytic cycling. Curr. Biol. 13:1636–1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Virag A., Lee M. P., Si H., Harris S. D. 2007. Regulation of hyphal morphogenesis by cdc42 and rac1 homologues in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 66:1579–1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wedlich-Soldner R., Altschuler S., Wu L., Li R. 2003. Spontaneous cell polarization through actomyosin-based delivery of the Cdc42 GTPase. Science 299:1231–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wesp A., Hicke L., Palecek J., Lombardi R., Aust T., Munn A. L., Riezman H. 1997. End4p/Sla2p interacts with actin-associated proteins for endocytosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 8:2291–2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshiuchi S., Yamamoto T., Sakane H., Kadota J., Mochida J., Asaka M., Tanaka K. 2006. Identification of novel mutations in ACT1 and SLA2 that suppress the actin-cable-overproducing phenotype caused by overexpression of a dominant active form of Bni1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 173:527–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zekert N., Fischer R. 2008. The Aspergillus nidulans kinesin-3 UncA motor moves vesicles along a subpopulation of microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 20:673–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.