Abstract

Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B strains are responsible for most meningococcal cases in the industrialized countries, and strains belonging to the clonal complex ST-41/44 are among the most prevalent serogroup B strains in carriage and disease. Here, we report the first genome and transcriptome comparison of a serogroup B carriage strain from the clonal complex ST-41/44 to the serogroup B disease strain MC58 from the clonal complex ST-32. Both genomes are highly colinear, with only three major genome rearrangements that are associated with the integration of mobile genetic elements. They further differ in about 10% of their gene content, with the highest variability in gene presence as well as gene sequence found for proteins involved in host cell interactions, including Opc, NadA, TonB-dependent receptors, RTX toxin, and two-partner secretion system proteins. Whereas housekeeping genes coding for metabolic functions were highly conserved, there were considerable differences in their expression pattern upon adhesion to human nasopharyngeal cells between both strains, including differences in energy metabolism and stress response. In line with these genomic and transcriptomic differences, both strains also showed marked differences in their in vitro infectivity and in serum resistance. Taken together, these data support the concept of a polygenic nature of meningococcal virulence comprising differences in the repertoire of adhesins as well as in the regulation of metabolic genes and suggest a prominent role for immune selection and genetic drift in shaping the meningococcal genome.

Neisseria meningitidis is a commensal of the upper airways in about 10% of the healthy human population and sometimes can cause life-threatening infections, especially in infants and young adults (73). The only well-established virulence factor in N. meningitidis is the polysaccharide capsule, which mediates resistance against complement-mediated lysis and opsonophagocytosis (20). Based on the chemical composition and the immunological characteristics of the capsular polysaccharide, meningococci can be divided into 12 serogroups (20). Strains of serogroup B are of particular concern, because they are a major cause of invasive disease in Europe and the United States (28), and there currently is no licensed vaccine available (92).

According to multilocus sequence typing (MLST), serogroup B strains belonging to the sequence type 41/44 (ST-41/44) clonal complex (CC) are among the most frequently isolated serogroup B strains from healthy carriers as well as from disease cases (12), and certain members of this clonal complex also displaced the formerly prevailing ST-32 complex meningococci as the major cause of serogroup B meningococcal disease in many European countries (46). In addition to the same sialic acid containing capsular polysaccharide, comparative genome hybridization studies (mCGH) further revealed that all serogroup B strains investigated have a highly similar gene content and probably share an ancestor (30, 72). However, despite these similarities, serogroup B strains from different sequence types display pronounced differences in their pathogenic potential. For example, although belonging to the aforementioned ST-41/44 CC, ST-136 strains can be found almost exclusively in healthy carriers, whereas strains from the hyperinvasive lineage ST-32 CC are isolated predominantly from disease cases (13, 33, 90) (http://pubmlst.org/).

These observations suggest that the capsule is necessary but not sufficient to confer virulence. Recent epidemiological approaches (5), as well as (comparative) genome sequencing (3, 54, 56, 65, 77) and mCGH studies (30, 71, 72), performed with different sets of strains belonging to different serogroups instead suggest a polygenic nature of meningococcal virulence. The genome sequence of a serogroup B carriage strain and its comparison to the genome of an invasive serogroup B strain therefore would provide the opportunity not only to capture in more detail differences in gene content but also to analyze small differences in genes common to invasive and noninvasive serogroup B strains in a presumably more-homogenous genetic background. However, no such detailed genome comparisons of different serogroup B strains based on genome sequences have been performed so far.

In addition to genome comparisons, transcriptome analysis carried out with the serogroup B strain MC58 from the hyperinvasive lineage ST-32 CC and with a strain from the commensal species N. lactamica recently identified genes that are specifically regulated only in meningococci upon contact with human bronchial epithelial cells (24). Of note, of the 347 genes that were found to be differentially regulated in N. meningitidis MC58, only 167 were common to both species, indicating that the different behaviors of the two species reside in the genes regulated specifically in meningococci and N. lactamica, respectively. However, no within-species transcriptome comparisons between two meningococcal strains belonging to an invasive and a noninvasive lineage have been carried out so far.

Therefore, we provide here the first high-quality draft sequence of a genome from the ST-136 serogroup B carriage isolate α710 (13) and compared it to the genome of strain MC58 (77) with respect to the predicted functions and subcellular localizations of the encoded proteins (22). We further compared the transcriptomes of both strains upon adhesion to human nasopharyngeal cell lines to comprehensively capture genetic differences between these two serogroup B meningococcal strains on a genome-wide scale.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Comparative genomics. (i) Sequencing and assembly of the N. meningitidis α710 genome.

Small-insert shotgun libraries with insert sizes of 2.0 to 3.0 kb were constructed in the pGEM vector by MWG Biotech AG (Ebersberg, Germany) and sequenced as described previously (65). In addition, a large-insert fosmid library was constructed by IIT GmbH (Bielefeld, Germany) in Escherichia coli EPI300 cells using the pCC1FOS fosmid vector (Biozym Scientific, Hess. Oldendorf, Germany). All regions of the consensus sequence were polished to a phred quality score of at least 40 by primer walking. The assembled contigs of α710 were ordered by comparison to the sequenced genome of strain MC58 (GenBank accession number AE002098) (77) and concatenated by 12-mer linkers (CTAGCTAGCTAG) containing stop codons in all six reading frames. The entire assembly resulted in five contigs and finally was verified by PCRs spanning the five sequence gaps using genomic DNA from strain MC58 as a control.

(ii) Annotation of the α710 genome.

The assembled genome was subjected to automatic annotation with the GenDB genome annotation system (50). Assignments of the putative functions of the encoded proteins were based on results of homology searches against a number of databases, including in particular COG (76) and InterPro (51), and the prediction of the putative localization of the encoded proteins was performed using PSORTb (23).

(iii) Computational genome comparisons.

Pairwise whole-genome comparisons between the genomes of strains α710 and MC58 were performed using BLASTN (1) and the Artemis comparison tool (ACT), release 5 (10). Orthologous coding sequences (CDSs) were operationally identified as bidirectional best hits (BBHs) in BLASTP comparisons having more than 50% sequence identity over at least 50% of the query sequence length. We excluded 57 short CDSs (median length, 198 bp) present in both genomes from further computational comparisons, as they had ambiguous annotations in the genome of strain MC58 (77) and the other published meningococcal genomes (3, 54, 56, 65). Since another 63 CDSs were either putative pseudogenes in both serogroup B genomes or a pseudogene in one genome that lacked an ortholog in the other genome, they also were excluded from further comparisons. By calculating BLASTP bit score ratios (BSR) of BBHs, the sequence variability between groups of orthologous pairs with at last one functional copy in one of the two genomes compared was assessed with respect to the sequences of the MC58 orthologs.

(iv) Phylogenetic analyses.

For a genome-based meningococcal phylogeny, a neighbor net was computed as described in reference 65 using SplitsTree4 (31) based on the differential distribution of 2,295 COGs present in the genomes of strain α710 and the seven meningococcal strains Z2491 (AL157959) (54), MC58 (AE002098) (77), FAM18 (AM421808) (3), 053442 (CP000381) (56), α14 (AM889136), α153 (AM889137), and α275 (AM889138) (65).

(v) Identification of (novel) MMEs.

Minimal mobile elements (MMEs) and candidate MMEs (cMMEs) were identified based on the criteria given in reference 61, and all cMMEs reported were additionally screened for the presence of at least one copy of a neisserial DNA uptake sequence (GCCGTCTGAA) within the cMMEs or the conserved flanking genes. When the corresponding site in both genomes contained different CDSs it was identified as an MME, and when one of the two regions within a site was empty it was classified as a cMME.

(vi) Statistical genome analyses.

Multiple testing corrections were performed according to the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure to control the false discovery rate (FDR), and unless stated otherwise the significance level was set to 5%. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 2.7.0 (57) (http://www.r-project.org/).

Comparative transcriptomics. (i) Isolation of total RNA.

The strains MC58 and α710 were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Biochrom AG, Germany) with HEPES (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany) to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.5 to 0.6), and total RNA was isolated in duplicate from each strain from 10-ml culture pellets using the RNeasy mini kit with on-column DNase treatment (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For the isolation of bacterial RNA on adhesion to FaDu cells, the cells were grown to confluence in T175 cell culture flasks (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany), and 10 flasks each were infected with capsule knockout derivatives of the strains MC58 and α710 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 to 200. After infection for 3 h, adherent bacteria were recovered as described in reference 16, and RNA was isolated from at least four infection experiments.

(ii) Microarray hybridization and data analysis.

RNAs from both strains grown in RPMI and from the respective capsule knockout derivatives on adhesion to FaDu cells were used in a common reference design (89), and an aliquot from each of the eight RNA samples formed the common reference. Five micrograms of each sample RNA was reverse transcribed with Cy3-dCTP, and 5 μg of the common reference RNA was reverse transcribed with Cy5-dCTP using standard procedures (34). The labeled cDNAs were mixed together and hybridized onto spotted 70mer oligonucleotide microarrays comprising the genomes of the meningococcal strains α14, FAM18, MC58, and Z2491, as described in reference 67, using a Tecan HS 4800 Pro hybridization station (Tecan Deutschland GmbH, Crailsheim, Germany). Two microarray slides were hybridized for each sample (MC58 in RPMI, α710 in RPMI, adherent MC58, and adherent α710). The microarray slides were scanned using a Genepix professional 4200A scanner (MDS Analytical Technologies, Ismaning, Germany), and the images were quantified using the Genepix Pro 6.0 gridding software. The raw files were analyzed using the Limma package (70) implemented in R version 2.7.0. Genes having an FDR of <0.05 after BH multiple testing corrections and a log-odds (B-statistic) value greater than 1.4, corresponding to a greater-than 80% probability of being differentially regulated under the various conditions tested, are given in Table S5 in the supplemental material, and genes having a B-statistic value greater than 3, corresponding to a probability of being differentially regulated of greater than 95%, were used for further statistical analyses of their functional distribution.

(iii) Real-time RT-PCR.

The validation of the microarray data was performed using the StepOnePlus real-time PCR system with SYBR green (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). Two micrograms of each RNA was reverse transcribed (RT), and suitable dilutions of the cDNA were used as the template for quantification using the StepOnePlus system. Specific primers were designed for 11 genes (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and the relative amounts of the cDNAs in the samples were determined using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method as described by the manufacturer. The expression of the tested genes was normalized to the expression level of NMB1752, which was not found to be differentially regulated under all of the conditions tested in this study.

Phenotypic characterization of serogroup B strains. (i) Growth rate measurements.

Growth rate measurements of the strains were performed in RPMI 1640, neisserial defined medium (NDM) (39), and supplemented proteose peptone medium (PPM+). The cultures were incubated at 37.0°C at 200 rpm, and the OD600 was determined during 24 h (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material for example growth curves). Based on a logistic model of population growth in a growth-limiting environment, the observed OD600 data were consecutively fitted to the logistic growth function by nonlinear regression analysis using R version 2.7.0 and the nls package. Each growth measurement was repeated three times, and from the fitted curve the growth rate, r (in min−1), was determined for each growth experiment independently.

(ii) Cell adhesion and invasion assays.

Cell adhesion and invasion assays were performed with human FaDu (ATCC number HTB-43) and Detroit562 (ATCC number CCL-138) nasopharyngeal epithelial cell lines. The MOI was adjusted in RPMI 1640 to 10, and the cells were infected for 6 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. The numbers of adherent and intracellular bacteria then were assessed as described in reference 38. For the comparison of the adhesion of encapsulated and unencapsulated strains to FaDu cells, a serogroup B capsule-deficient mutant of strain α710 was constructed using the plasmid pGH 15, which contains a chloramphenicol resistance cassette in the polysialyltransferase gene said, as described in reference 38. All infection experiments were performed in duplicate, and the experiments were repeated at least three times.

(iii) LOS typing and Western blotting.

Lipooligosaccharide (LOS) immunotyping was performed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and the outer membrane proteins Opc and Opa were detected by Western blotting as described in reference 38. The expression of class I pili was assessed via Western blotting using the antibody SM1 (84).

(iv) Serum bactericidal assay.

Serum bactericidal assays with encapsulated strains were performed exactly as described in reference 87. Each experiment was repeated at least four times.

Nucleotide sequence microarray data accession numbers.

The assembled genome sequence of N. meningitidis α710 has been assigned GenBank accession number CP001561. The complete microarray data set associated with this study has been deposited in the GEO omnibus database at NCBI under the accession number GSE22906.

RESULTS

A whole-genome shotgun sequencing approach was used to generate a high-quality fully assembled draft sequence of the N. meningitidis ST-136 serogroup B strain α710 genome, and a common reference design was chosen to further assess differences in genome expression between the carriage strain α710 and the disease strain MC58 upon contact with human nasopharyngeal cells. Finally, the differences in genome architecture and expression profile were compared to phenotypic differences observed in in vitro cell culture assays (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Genomic and phenotypic comparison of meningococcal serogroup B strains α710 and MC58

| Feature | α710 | MC58a | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotypic characterization | |||

| Sequence type | ST-136 | ST-74 | |

| Clonal complex | ST-41/44 | ST-32 | |

| porA-VR1 | 17 | 7 | |

| porA-VR2 | 16-3 | 16-2 | |

| porB | 3-107 | 3-24 | |

| fetA | F5-5 | F1-5 | |

| Epidemiology | |||

| Source of the isolate | Carrier | Patient | |

| Frequency of the respective sequence types in carriersb (%) | 1.5 | ND | |

| Frequency of the respective sequences types in casesc (%) | 0.2 | ND | |

| Frequency of the respective clonal complexes in carriersb (%) | 22.1 | 5.0 | |

| Frequency of the respective clonal complexes in casesc (%) | 16.8 | 23.8 | |

| Genome characteristics | |||

| No. of contigs | 5 | 1 | |

| Genome size (Mb) | ≥2.242 | 2.272 | |

| No. of putative genes | 1,975 | 2,063 | |

| Coding area (%) | 79.3 | 79.1 | |

| % in COGs | 82.7 | 79.1 | |

| Predicted no. of outer membrane proteins | 55 | 54 | |

| No. of strain-specific genes | ≥100 | ≥157 | |

| Transcriptome comparisons upon adhesion to epithelial cells | |||

| No. of specifically upregulated core genesd | 46 | 138 | |

| No. of specifically downregulated core genesd | 50 | 134 | |

| No. of differentially regulated core genes upon adhesione | 82 | 55 | |

| Phenotypic characterization | |||

| Serogroup | B | B | |

| LOS type | L 3/7/9 | L 3/7/9 | |

| Opa expression | + | + | |

| Opc expression | − | + | |

| Class I type IV pilus | + | + | |

| Growth rate | |||

| RPMI 1640 (min−1) | 0.0164 ± 0.0016 | 0.0172 ± 0.0012 | 0.452f |

| PPM+ (min−1) | 0.0268 ± 0.0005 | 0.0250 ± 0.0028 | 0.258f |

| NDM (min−1) | 0.0023 ± 0.0001 | 0.0041 ± 0.0007 | 0.043f |

| Adhesion to epithelial cellsg | |||

| FaDu cells (%) | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 14.5 ± 9.3 | 0.029f |

| FaDu cellsh (%) | 21.1 ± 10.2 | 60.6 ± 4.8 | <0.001f |

| Detroit562 cells (%) | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 9.5 ± 4.5 | 0.021f |

| Invasion of epithelial cellsg | |||

| FaDu cells (%) | 0.0002 ± 0.0002 | 0.0020 ± 0.0012 | 0.015f |

| Detroit562 cells (%) | 0.0004 ± 0.0002 | 0.0021 ± 0.0014 | 0.058f |

| Serum resistancei (%) | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 106.6 ± 8.2 | <0.001f |

The numbers given for N. meningitidis strain MC58 are based on the GenBank accession number AE002098 entry. ND, not determined.

Frequency of sequence types and clonal complexes in 822 carrier isolates as given in reference 13.

Frequency of sequence types and clonal complexes in 525 disease isolates during the time period 2000 to 2002 in Germany, characterized by the European Meningococcal MLST Centre, Oxford, United Kingdom.

Number of up- or downregulated genes in the comparison of growth in RPMI and adhesion to epithelial cells.

Differentially regulated genes identified in the comparison of adherent MC58 and adherent α710.

Two-sided Welch two-sample t test.

Ratio in percentage of adherent and invasive bacteria, respectively, to total bacteria (see Materials and Methods for further details).

Adhesion values for unencapsulated ΔsiaDB mutants.

Ratio in percent of viable bacteria after incubation for 30 min in the presence of 10% human serum and viable bacteria incubated without serum (see Materials and Methods for further details).

Chromosome structure comparison.

Among the seven currently sequenced meningococcal genomes, the genome of strain α710 is most similar to the genome of the serogroup B strain MC58 with respect to gene content (Fig. 1) and chromosome structure (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Similarly to the MC58 genome, it has an average GC content of 51.7% and consists of a single circular chromosome of about 2.24 Mbp that has been assembled into five contigs using the genome of MC58 as a reference (more details about the genome assembly are given in the supplemental material). The remaining five unsequenced gaps comprise about 19 kb, which equals 0.84% of the deduced α710 genome size and probably consist mainly of highly repetitive DNA such as, e.g., NIME repeats, which form secondary structures that are difficult to sequence.

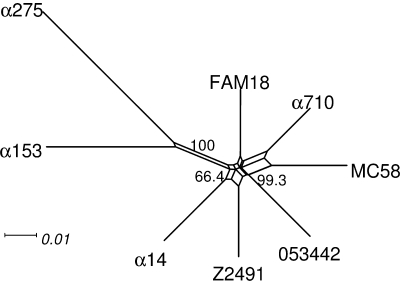

FIG. 1.

Neighbor net based on the distribution of 2,295 COGs in eight meningococcal genomes. The numbers at each split give the percent bootstrap support in 1.000 replicate. The data sets suggest that the α710 genome is closer to the MC58 genome than to the other meningococcal genomes from non-serogroup B strains.

The genome of strain α710 codes for at least 1,975 proteins and 57 transfer RNAs, and it contains four ribosomal operons. Both genomes are highly colinear with only three inversions/translocations larger than 30 kb in size (Fig. 2; also see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In the α710 genome, the first inversion and translocation (IT1), comprising about 48.8 kb, is flanked by a copy of the neisserial filamentous prophage Nf1 (36) and by a P2-like phage 34.3 kb in size inserted at the putative replication terminus (terC). The second translocation and inversion (IT2) comprises about 30.0 kb and is flanked in the genome of MC58 by two IS1655 elements. The third translocation/inversion (IT3), comprising about 80 kb, also is flanked on one side by the second copy of phage Nf1 and an adjacent opa pseudogene (NMBB_1708) in the genome of α710. Consequently, the two copies of the Nf1 phage present in each of the two serogroup B genomes reside at different sites in both chromosomes, suggesting a high mobility of this element within the meningococcal genomes. Likewise, hpuB together with the flanking hpuA gene (NMBB_2258 and NMBB_2259) encoding a TonB-dependent receptor protein probably also have been deleted in the MC58 genome via Nf1-encoded integrase ISNgo3-catalyzed recombination at flanking dRS3/Nf1 repeat sequences (3). This supports earlier findings suggesting that the integration of Nf1 is associated with genomic rearrangements in N. meningitidis (65).

FIG. 2.

Whole-genome and transcriptome comparisons of the two serogroup B meningococcal strains. The linearized α710 and MC58 genomes are shown in the middle-upper and middle-lower panels as gray bars, and regions syntenic in both genomes are connected via red and inverted regions via blue lines, respectively. Above and below the aligned genomes, the Karlin signature differences are given to detect regions of atypical compositional bias in both genomes, such as IHTs or the ribosomal operons (R). In addition, at the upper and lower margins the log2-fold changes in gene expression are given for both genomes, comparing the transcriptomes of cells in mid-log growth in RPMI 1640 medium and upon adhesion to human FaDu nasopharyngeal cell using a MC58-based microarray. In the α710 genome, black vertical lines on the forward and reverse strand indicate the positions of the five gaps (I to V). Pink boxes termed IT1, IT2, and IT3 designate inversions coupled to translocations as described in the text, a chromosomal region duplicated in the genome of MC58 (D), and the position of a P2-like prophage. The TPS system-encoding locus missing in the α710 genome is indicated by a pink box in the MC58 genome panel, and the differing positions of the Nf1 prophages are indicated by a red box in both genomes. Loci that have an atypical nucleotide composition and that contain a number of transcriptionally silent gene cassettes (discussed in more detail in the text) are given as green boxes.

The pronounced overall similarity in chromosome structure is further supported by the presence of the same islands of horizontally transferred DNA (IHT), in particular by the presence of IHT-B and IHT-C (77) in both genomes, which are absent from the other meningococcal genomes sequenced so far (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). However, while the capsule locus required for the synthesis of the serogroup B polysaccharide on IHT-A as well as IHT-E, probably representing a prophage λ remnant (30), are highly similar in both genomes, there is considerable variation in the genetic makeup of IHT-B and IHT-C. Both contain genes coding for two-partner secretion (TPS) proteins that are part of the TPS2 and TPS1 loci, respectively (Fig. 2), but various numbers of different silent 3′ gene cassettes. Strain α710 further lacks the 29.8-kb duplication comprising 36 genes (NMB1123 to NMB1159) that is found in the genome of MC58, and it is likely that this duplication coding for numerous housekeeping metabolic genes is specific for serogroup B strains of the clonal complex ST-32.

Gene content comparison.

Of the 2,143 CDSs putatively coding for functional proteins in at least one of the two strains, 156 genes from α710 have no functional ortholog in the MC58 genome, and 256 genes from MC58 have no functional ortholog in the genome of α710. Based on the COG functional classification scheme, the strain-specific genes differ in their functional category profile from genes common to both strains (Fig. 3 A). Among the common genes with known functional assignment, most code for proteins involved in basic metabolic functions, such as energy production and conversion (COG C); the transport and metabolism of amino acids (COG E), nucleotides (COG F), carbohydrates (COG G), and inorganic ions (COG P); translation (COG J); and cell wall/membrane biogenesis (COG M). In line with their role in basic metabolic functions, the common genes are significantly enriched for genes coding for cytoplasmic or cytoplasmic membrane proteins compared to the level for the strain-specific genes (Fig. 3B). Most of the strain-specific genes either are not part of any known COG (category X), code for proteins involved in cell motility (COG N), or belong to the COG functional category L, comprising proteins involved in replication, recombination, and repair.

FIG. 3.

Distribution of strain-specific and core genes in pairwise genome comparisons among the different functional categories and cellular compartments. (A) Histogram depicting the COG functional category profile for strain-specific and shared genes. Genes present in both genomes differ in their functional category profile from strain-specific genes (P < 0.01, χ2 test). The latter are enriched for genes that do not belong to any functional category (COG X), that code for proteins involved in cell motility (COG N), or that code for proteins involved in replication, recombination, and repair (COG L) (P = 0.055) (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; Fisher's exact test with BH multiple testing correction). Abbreviations: C, energy production and conversion; D, cell cycle control, mitosis, and meiosis; E, amino acid transport and metabolism; F, nucleotide transport and metabolism; G, carbohydrate transport and metabolism; H, coenzyme transport and metabolism; I, lipid transport and metabolism; J, translation; K, transcription; L, replication, recombination, and repair; M, cell wall/membrane biogenesis; N, cell motility; O, posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones; P, inorganic ion transport and metabolism; Q, secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism; R, general function prediction only; S, function unknown; T, signal transduction mechanisms; U, intracellular trafficking and secretion; V, defense mechanisms; X, not in COGs. (B) Histogram showing the different distributions of strain-specific and shared genes among the different subcellular compartments (P < 0.01, χ2 test) as predicted by PSORTb. Common genes are enriched for genes coding for cytoplasmic or inner membrane proteins, respectively (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; Fisher's exact test with BH multiple testing correction). Abbreviations: CP, cytoplasmic; CM, cytoplasmic membrane; PP, periplasmic; OM, outer membrane; EC, extracellular; UK, unknown.

Sequence variability of serogroup B core genes.

Genes present in both strains show about 98.0% (95% confidence interval [CI0.95] = [93.0, 100.0%]) nucleotide sequence identity. To further assess the nonneutral sequence variation of the encoded proteins, we calculated BSRs for all orthologous pairs and compared the obtained values for proteins belonging to different COG functional categories and subcellular localization (Fig. 4 A). The BSR median for all pairwise comparisons of the 1,731 shared proteins is 0.990 (CI0.95 = [0.749, 1.000]) with significant BSR differences between COG functional categories as well as subcellular compartments. Genes coding for proteins involved in translation (COG J) and transcription (COG K) are more conserved than the average, and genes not belonging to any known COG functional category are least conserved (Fig. 4A). With respect to their subcellular localization, the predicted outer membrane proteins are the least conserved in both strains (Fig. 4B). In addition to proteins not found in any COG (X), proteins involved in intracellular trafficking and secretion (COG U) and in cell motility (COG N) (P = 0.077, Fisher's exact test) are overrepresented among the 5% most-variable proteins (Fig. 4C). Among the remaining 95% of the more-conserved proteins, proteins involved in amino acid transport and metabolism (COG E) and translation (COG J) are overrepresented. With respect to the predicted subcellular localization, the 5% most-variable proteins are localized slightly more often in the outer membrane, whereas the conserved proteins either are cytoplasmic or localized in the cytoplasmic membrane (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the sequence variability between orthologs as expressed by their BSRs among the different COG functional categories and subcellular compartments. (A) Box-and-whiskers plot of the BSRs grouped by COG categories. In addition to significant differences among the different COG categories (P < 0.01, Kruskal-Wallis test), the levels of BSRs of orthologs belonging to the COG functional categories J and K are significantly higher and those belonging to category X are significantly lower than the overall BSR median, which is indicated by a black horizontal line (*, P < 0.05; two-sided Wilcoxon test with BH multiple testing correction). The 95% quantile (dashed horizontal line) is given to separate the 5% most variable orthologous pairs. For the abbreviations of the COG functional categories, see the legend to Fig. 3A. (B) Box-and-whiskers plot of the BSRs grouped by subcellular localization as predicted by PSORTb. Again, there are significant BSR differences between the subcellular compartments (P = 0.016, Kruskal-Wallis test) and compared to the overall BSR median (black horizontal line). Outer membrane proteins have a significantly lower degree of sequence conservation (*, P < 0.05; two-sided Wilcoxon test with BH multiple testing correction). For the abbreviations of the different subcellular compartments, see the legend to Fig. 3B. (C) Histogram comparing the COG functional distribution of the 5% orthologs with the highest BSRs and the remaining 95% of more-conserved orthologs from panel A. Whereas the more-conserved orthologs belong more often to the COG functional categories E and J, the 5% most-variable orthologs are more enriched for the COG functional categories U and X than the former (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; Fisher's exact test with BH multiple testing correction). (D) Histogram showing the distribution of the 5% of genes with the highest BSRs among the different subcellular compartments as predicted by PSORTb from panel B. Whereas the more-conserved orthologs are located significantly more frequently in the cytoplasm than the 5% most-variable orthologs, the latter are more often located at the outer membrane (P = 0.052) or have no subcellular localization prediction (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; Fisher's exact test with BH multiple testing correction). For the abbreviations, refer to the legend to Fig. 3.

Among the 1% most variable proteins, nine are (hypothetical) proteins with unknown function, and of the eight proteins with (putative) functional assignments, three encode hemagglutinin/hemolysin-related proteins that belong to the class TPS systems (TpsA2/NMB0497, TpsS2/NMB0499, and TpsS7/NMB1772) (82) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). TPS systems are composed of a secreted protein, TpsA, and its cognate transporter, TpsB. TpsA proteins display significant C-terminal sequence variation and are translocated across the meningococcal outer membrane by their cognate transporters (TpsB). Since it was shown recently that a small percentage of mature TpsA remains associated with the bacteria and contributes to the interaction with epithelial cells, differences in the sequence and repertoire of TpsA proteins between strains might result in differences in the interaction with host cells (63). Finally, this class of most-variable proteins includes a glycosyl transferase (NMB0846), an MafB-3 alternative C-terminal cassette (NMB0655) (see below), the lactoferrin-binding protein B (LbpB/NMB1541), a transcription-repair coupling factor (NMB1281), and RNA-binding protein (NMB1826).

Classification of strain-specific genes.

About 20% of the serogroup B genes that have no functional ortholog in one of the two genomes are pseudogenes due to frameshift mutations. Insertion sequence (IS) element transposases together with genes coding for hypothetical proteins, phage proteins, putative transporters, and restriction-modification (RM) systems account for more than half of the strain-specific pseudogenes. The other half comprises numerous genes for diverse metabolic functions as well as two genes (NMB1967 in strain MC58 and NMBB_2143 in strain α710) coding for transcriptional regulators of the AraC/Xyls family (InterPro accession number IPR018060).

Another 20% of the genes differentially present in both strains are mostly single-gene insertions/deletions often coding for hypothetical proteins; 10% of the strain-specific genes are located on the MC58 genome duplication not present in the genome of strain α710 (Fig. 2), and 10% code for silent gene cassettes involved in gene conversion, as described below in more detail. However, about 40% of the strain-specific genes either are IS elements or are located on putatively mobile genetic elements, such as IHTs, prophages, and MMEs (Fig. 2).

MMEs in both serogroup B genomes.

An MME is a region encompassing two highly conserved metabolic genes that are cooriented and between which different whole-gene cassettes are found in different strains (61). In contrast to prophages or IS elements, they are chromosomally incorporated solely through the action of homologous recombination. Pairwise genome comparisons suggest nine novel putative cMME sites, of which three are empty in MC58 and six in α710, as well as five novel putative MME sites (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). As in the case of prophages, most genes located on MMEs and cMMEs code for hypothetical proteins, and only a few encode proteins with functional annotations. For example, at the cMME-bfrAlipA locus MC58 contains six genes (NMB1209 to NMB1214) that are absent from α710 (TPS in Fig. 2) and code for, among others, a TpsA protein (TpsA3/NMB1214) and a repeat-in-toxin (RTX) activating protein (NMB1210) (82). At MME-pglC, in addition to pglB, the genome of α710 (comprising NMBB_2071 to NMBB_2074) contains further genes for glycosyl transferases that are involved in the glycosylation of type IV pili (Tfp) (35), and therefore Tfp glycosylation might be different in both strains. Another example of an MME that has a patchy distribution among the meningococcal genomes is MME-prpCacnA. In strain α710 (as in the genomes of strains α14 and FAM18), the two genes vanX and NMBB_0475 are jointly inserted between prpC and acnA, forming a possible operon, whereas in strain MC58 (as well as in strain Z2491 and gonococci) the nonhomologous NMB0432 can be found at the respective locus. vanX encodes a d-alanyl-d-alanine dipeptidase, and NMBB_0475 encodes a membrane protein that might function as a transporter. In Escherichia coli, it was shown that the vanX homolog (ddpX) is cotranscribed with a putative dipeptide transport system in stationary phase by the transcription factor RpoS, and that these genes might contribute to the increased survival of the cells under stress conditions (40). Although meningococci lack RpoS, it still is possible that both genes affect meningococcal physiology in a similar manner by utilizing different transcription factors. In addition to genes encoding metabolic functions, genes coding for putative transcriptional regulators also can be found on cMMEs. In particular, at cMME-thiEthiS strain α710 encodes, in addition to a Zinc-binding oxidoreductase (IPR014182), an MarR/HxlR-type helix-turn-helix (HTH) transcriptional regulator (IPR002577) (NMBB_2381), which together are absent from the other sequenced neisserial genomes. In turn, strain α710 contains an AAA+-type ATPase (IPR003593) and a protein with a von Willebrand factor type A domain (IPR002035) (NMBB_2310 and NMBB_2311) at MME-hrpA, and in strain MC58 it encodes a putative HTH transcriptional regulator (IPR001387) (NMB2012) and two conserved hypothetical proteins (NMB2013 and NMB2014).

Loci with silent gene cassette-mediated variation.

The meningococcal genome harbors a number of loci 1.0 to 23 kb in size that often code for surface or excreted proteins involved in host cell interactions (66). At these loci, a putatively functional and expressed gene is neighbored by a number of transcriptionally silent gene cassettes that are used via gene conversion as sources of variation for the expressed proteins. These loci comprise the pilE/S locus coding for the major Tfp subunit, which mediates the initial contact with human mucosal epithelial cells, the three maf loci, as well as the RTX islands I to III and the TPS regions 1 and 2 (Fig. 2). Although very little is known about the maf loci and the function of the encoded proteins in N. meningitidis, a detailed genetic analysis (see the supplemental material) suggests that similarly to the products of pilE/S, TPS, and RTX loci, the encoded MafB proteins are involved in host cell interactions. Genes with no functional ortholog in the other serogroup B genome are significantly enriched for genes belonging to loci with silent cassettes compared to the level for genes that can be found in both genomes (P < 0.01, Fisher's exact test). Orthologous proteins encoded by genes on these loci also are significantly less similar (BSR = 0.947) than other orthologous protein pairs (BSR = 0.990) (P < 0.001, Wilcoxon test). In particular, the predicted outer membrane protein orthologs encoded by genes on these loci (BSR = 0.856) are less similar to each other than other orthologous outer membrane proteins (BSR = 0.983) (P = 0.024, Wilcoxon test).

Strain-specific outer membrane proteins.

Among the strain-specific genes predicted to code for outer membrane proteins, seven were specific to MC58 and eight were specific to α710 (Table 2 ). Of the α710-specific genes coding for outer membrane proteins, two are located on putative prophages, PilC2 and Opa are encoded by phase-variable genes that are in the off state in the published MC58 annotation, NMBB_1488 codes for a putative TonB-dependent receptor that has a central deletion of about 100 bp in the MC58 ortholog, and NMBB_2259, coding for the haptoglobin-hemoglobin receptor HpuB, is missing from MC58, as described above. In turn, of the MC58-specific genes coding for outer membrane proteins, the genes encoding the major adhesin OpcA, the minor adhesin NadA, and the putative TPS system protein TpsA3 (NMB1214) have no ortholog in the α710 genome. The phase-variable gene coding for the outer membrane protease NalP (NMB1969), which processes the neisserial heparin-binding antigen (NHBA) (69) and mediates the proteolytic release of LbpB from the meningococcal surface (59), is in the off state and therefore is a pseudogene in α710. However, most of the strain-specific outer membrane proteins belong to families that consist of putative paralogs present in various numbers in both genomes, such as the TPS system proteins, putative TonB-dependent receptors, and the RTX proteins (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Differences in content and sequence of selected strain-specific outer membrane proteins as well as proteins known to be involved in host cell interaction and serum resistance in the two serogroup B strains

| Protein/adhesin | Gene designation for: |

BSR | PSORTba | COGb | InterProc | GC (%) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC58 | α710 | |||||||

| Major adhesins | ||||||||

| Opad | ψNMB0490e | ψNMBB_0442Ae | OM | M | IPR003394 | 49.7 | 15 | |

| ψNMB0926e | ψNMBB_1708Ae | OM | M | IPR003394 | 49.3 | |||

| ψNMB1465e | ψNMBB_1080Ae | OM | M | IPR003394 | 49.0 | |||

| ψNMB1636e | NMBB_1866e | OM | M | IPR003394 | 50.0 | |||

| OpcA | NMB1053 | OM | X | IPR009876 | 46.2 | 86 | ||

| Tfp proteins | ||||||||

| PilC1 | ψNMB1847e | ψNMBB_2111Ae | OM | N, U | IPR008707 | 50.4 | 52 | |

| PilC2 | ψNMB0049e | NMBB_0053e | OM | N | IPR008707 | 50.4 | 52 | |

| PilE | NMB0018 | NMBB_0021 | 0.854 | UK | N, U | IPR001082 | 52.2 | 85 |

| Autotransporters | ||||||||

| App | NMB1985 | NMBB_2277 | 0.960 | OM | M, U | IPR000710, IPR004899, IPR005546 | 51.0 | 68 |

| NalP | NMB1969e | ψNMBB_2254Ae | OM | O, S | IPR011165 | 56.4 | 80 | |

| NhhA | NMB0992 | NMBB_1631 | 0.856 | UK | U, W | IPR005594, IPR008635 | 48.5 | 62 |

| MspA | NMB1998 | NMBB_2295 | 0.981 | OM | M, U | IPR000710, IPR005546 | 56.5 | 79 |

| Oca-type adhesin | ||||||||

| NadA | NMB1994 | OM | N | IPR005594 | 48.7 | 8 | ||

| β-Barrel protein | ||||||||

| NspA | NMB0663 | NMBB_0737 | 0.988 | OM | M | IPR003394 | 58.1 | 47 |

| TonB-dependent receptors | ||||||||

| NMB0293 | ψNMBB_0325A | OM | P | IPR010105 | 53.7 | |||

| ψNMB1346 | NMBB_1488 | OM | P | IPR000531 | 50.8 | |||

| HpuB | NMBB_2259 | OM | P | IPR010949 | 55.0 | 41 | ||

| RTX toxins and activating enzymes | ||||||||

| NMB1210 | UK | O | IPR003996 | 47.0% | ||||

| NMB1405 | OM | Q | 45.1 | 78 | ||||

| NMBB_1560 | OM | X | 43.6 | 78 | ||||

| TPS systems | ||||||||

| TpsA1/TpsA2 | NMB0497 | NMBB_0546 | 0.474 | OM | U | IPR011050 | 49.2 | 63 |

| TpsA3 | NMB1214 | OM | U | IPR011050 | 50.6 | |||

| TpsA2/TpsA | NMB1779 | NMBB_2023 | 0.754 | OM | U | IPR011050 | 49.2 | 63 |

| TpsS8 (TpsA cassette) | NMB1775 | OM | U | IPR006914, IPR006915 | 49.3 | 63 | ||

| NMBB_2021 | OM | M | IPR006914, IPR006915 | 49.5 | ||||

| Complement resistance | ||||||||

| PorA | NMB1429 | NMBB_1586 | 0.922 | OM | M | IPR001702 | 51.7 | 32 |

| fHBP/GNA1870 | NMB1870 | NMBB_2133 | 0.746 | UK | X | IPR014902 | 52.1 | 44 |

| Other strain-specific outer membrane proteins | ||||||||

| Phage P2 tail protein S | NMBB_1108 | OM | X | 53.9 | ||||

| Phage late control gene D | NMBB_1141 | OM | R | IPR010277 | 56.6 | |||

For the abbreviations of the PSORTb predictions for the protein subcellular localization, see the legend to Fig. 3.

For the abbreviations of the COG functional categories, see the legend to Fig. 3.

The InterPro database entries are given for each protein for further information on the respective protein families.

Although all genes that are pseudogenes in both genomes were excluded from further analyses as described in Materials and Methods, all four genetic loci carrying opa genes are given here for the sake of completeness.

The opa, pilC1, and pilC2 genes are phase-variable genes. They can be in an off state in one or both of the two genome sequences due to slipped-strand mispairing at homopolymeric tracts, which per the definition results in the generation of pseudogenes (ψ).

Comparison of the MC58 and α710 virulence gene content.

Of the 104 putative virulence genes in strain MC58 (77), only lgtG (NMB2032), opcA, nadA, the three genes encoding putative TonB-dependent siderophore receptors (NMB0293, NMB1346, and NMB1449), and NMB1210 and tpsA3 (NMB1214), both located on cMME-bfrAlipA (see above; also see Table S3 in the supplemental material), are entirely missing from or are nonfunctional in α710 (Table 2). From another set of 60 potential core pathogen-specific genes that were found to be absent in N. lactamica but present in a panel of 48 meningococcal strains (30), all were present in strain α710. Among the 45 genes recently found to be absent from 7 commensal Neisseria species but present in all 18 serogroup B meningococcal strains investigated (72), only NMB0293, NMB0832 (which codes for a putative anticodon nuclease), and NMB1167 (encoding a small hypothetical protein) are missing from α710. A more-detailed analysis is given in the supplemental material.

Correlation of genomic and phenotypic differences.

While both strains grow almost equally well in PPM+ and RPMI 1640 media, they show a marginally significant difference in their growth rates in minimal medium (NDM) (Table 1). However, it is possible that the slightly faster growth rate observed for MC58 in NDM does not reflect a correspondingly faster growth in vivo, since strain MC58 already has been in long use in the laboratory since its first isolation (49) and might already have adapted to the in vitro conditions. In contrast to the almost-identical growth rates, both strains show considerable phenotypic differences in their adhesion to and invasion of human epithelial cell lines as well as their serum resistance, with the invasive strain MC58 showing a higher rate of adhesion to and invasion of FaDu and Detroit562 cell lines as well as a higher serum resistance than that of the carriage strain α710.

Comparison of gene expression profiles in both serogroup B strains upon adhesion to FaDu epithelial cells.

To assess differences in the expression of shared as well as MC58-specific genes, transcriptional profiling using oligonucleotide microarrays based on the MC58 genome sequence was performed with both strains grown in RPMI 1640 and upon adhesion to FaDu cells. The following data sets were extracted from the microarray analyses: (i) core genes regulated in both strains between growth in RPMI 1640 and adhesion to FaDu cells, (ii) core genes regulated in only one of the strains between growth in RPMI 1640 and adhesion to FaDu cells, (iii) core genes differentially regulated between strains MC58 and α710 specifically on adhesion to FaDu cells, excluding possible medium effects, and (iv) MC58-specific genes differentially expressed between growth in RPMI 1640 and adhesion to FaDu cells. The distribution of the functional categories of differentially regulated genes in the above-mentioned categories is depicted in Fig. 5. In addition, the 5% of genes with the highest log2-fold expression changes are given in Table 3, and the complete list of differentially regulated genes are given in Table S5 in the supplemental material.

FIG. 5.

Functional classification of genes differentially expressed upon adhesion to human FaDu nasopharyngeal cell lines in the two meningococcal serogroup B strains MC58 and α710. Core genes regulated in both strains are depicted as black bars, core genes regulated only in MC58 as dark gray, and those regulated only in α710 as light gray bars, respectively; regulated MC58-specific genes are depicted as white bars. (A) Distribution of core and MC58-specific genes among the five different COG functional classes. The regulated core genes are not distributed equally over the five functional classes (P < 0.01, χ2 test) but are enriched for metabolic genes in the respective three datasets (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Likewise, the distribution of core genes that are regulated in only one strain also differs significantly between both strains (P < 10−15, χ2 test) and also from the core genes regulated in both strains (P < 10−9, χ2 test). In contrast, the regulated MC58-specific genes are evenly distributed over all functional classes (P = 0.77, χ2 test). (B) Distribution among the different COG functional categories separated into up- and downregulated genes. For each of the four datasets, the percentage of regulated genes adds up to 100% separately. Fifty-eight percent of the downregulated MC58-specific genes fall into COG category X, which therefore falls off the scale to the right side of the histogram. In all four datasets the downregulated genes are enriched for genes not in COGs (COG X), whereas the core genes that are upregulated in only one strain are enriched for genes coding for proteins involved in translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (COG J) (P < 0.05; Fisher's exact test with BH multiple testing correction). For clarity, significant differences have not been depicted in the diagram. For the abbreviations, refer to the legend to Fig. 3.

TABLE 3.

Core genes most differentially regulated (5%) between the two serogroup strains on adhesion to epithelial cells and growth in RPMIa

| MC58 classificationb | Gene | Productc | PSORTb predict tiond | Gene expression differences between: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesion and growth in RPMI |

Adherent MC58 and adherent α710g | |||||

| MC58e | α710f | |||||

| Information storage and processing | ||||||

| NMB0299 | comE1 | DNA-binding competence protein ComE1 | CM | 3.43 | ||

| NMB0686 | rnc | Ribonuclease III | CP | 2.27 | ||

| NMB1368 | Putative ATP-dependent RNA helicase | CP | 4.05 | 3.63 | ||

| NMB2048 | Putative periplasmic DNA ligase | UK | 1.99 | |||

| Cellular processes | ||||||

| NMB0879 | cysA | Sulfate/thiosulfate import ATP-binding protein | CP | 2.58 | ||

| NMB1372 | clpX | ATP-dependent Clp protease | CP | −2.94 | ||

| NMB1398 | sodC | Superoxide dismutase (Cu-Zn) | PP | −3.53 | ||

| NMB1475 | Conserved hypothetical protein | UK | −3.81 | −2.74 | ||

| NMB1845 | Putative membrane-associated thioredoxin | UK | 2.81 | 2.83 | ||

| Metabolism | ||||||

| NMB0567 | nqrC | Na+-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit C | UK | 2.05 | ||

| NMB1077 | ABC transporterh | CM | 2.35 | |||

| NMB1540 | lbpA | Lactoferrin-binding protein A | OM | −3.31 | −3.07 | |

| NMB1541 | lbpB | Lactoferrin-binding protein B | OM | −4.56 | −4.32 | |

| NMB1572 | acnB | Aconitate hydratase 2 | UK | 1.74 | ||

| NMB1814 | aroB | 3-Dehydroquinate synthase | CP | 1.91 | ||

| NMB1688 | Putative l-asparaginase Ih | CP | 2.06 | |||

| Poorly characterized | ||||||

| NMB0330 | Putative UPF0243 zinc-binding protein | UK | 2.18 | |||

| NMB0546 | Putative alcohol dehydrogenase | CP | 1.54 | |||

| NMB0902 | Hypothetical protein | UK | −2.29 | |||

| NMB0906 | Conserved hypothetical protein | UK | −2.74 | |||

| NMB0995 | Conserved hypothetical protein | UK | 2.21 | |||

| NMB1048 | Putative transporter | CM | 4.64 | 3.62 | ||

| NMB1494 | Conserved hypothetical protein | UK | −2.37 | |||

| NMB1753 | Putative VapD-like protein | CP | −3.09 | |||

| NMB1906 | Conserved hypothetical protein | UK | 2.26 | |||

| Not in COGs | ||||||

| NMB0374 | mafB1 | MafB1 protein | UK | −4.04 | ||

| NMB0460 | tbp2 | Transferrin-binding protein 2 | OM | −1.83 | ||

| NMB0467 | Hypothetical periplasmic protein | UK | −1.89 | |||

| NMB0483 | Hypothetical integral membrane protein | UK | −2.68 | |||

| NMB0555 | Hypothetical membrane-associated protein | UK | 1.76 | |||

| NMB0905 | Hypothetical protein | UK | −2.35 | |||

| NMB1739 | Hypothetical integral membrane protein | UK | −3.50 | |||

| NMB2015 | Conserved hypothetical protein | UK | −2.85 | |||

| NMB2152 | Hypothetical protein | CP | −3.09 | |||

For all genes the probability of being differentially regulated was greater than 99% with the exception of NMB0995 and NMB1688, for which this probability was greater than 95%.

Functional classification according to the COG classification scheme (76).

Annotation according to the corresponding NeMeSys database entries (60).

For the abbreviations of the PSORTb predictions for the protein subcellular localization, see the legend to Fig. 3.

Log2-fold change of strain MC58 on adhesion compared to that after growth in RPMI 1640.

Log2-fold change of strain α710 on adhesion compared to that after growth in RPMI 1640.

Log2-fold change of adherent strain MC58 compared to that of adherent strain α710.

Also classified into the category cellular processes.

For both strains, the results of quantitative RT-PCR for a test set of 11 genes (see Table S1) comparing gene expression in adherent bacteria to bacteria grown in RPMI 1640 were in very good agreement with the respective microarray data for both strains (Pearson's r2 = 0.94). A functional analysis of the regulated genes further revealed that, whereas the regulated MC58-specific genes are evenly distributed over all COG functional classes (P = 0.77, χ2 test) (22, 76), the regulated core genes in the corresponding three data sets are enriched for genes coding for metabolic functions (Fig. 5; also see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Likewise, the regulated core genes surprisingly were not significantly enriched for outer membrane protein-coding genes (P ≥ 0.09, Fisher's exact test).

In the following sections, only genes for which functional annotations are available according to Rusniok et al. (60) will be presented in more detail.

The core transcriptome in the comparison of growth in RPMI to adhesion.

Within the core genome, 110 genes showed similar values for the log2-fold change in expression levels (Pearson's r2 = 0.92), with 55 genes significantly upregulated and 55 genes significantly downregulated in both strains. Among the downregulated core genes were the two genes for lactoferrin-binding proteins A and B (lbpA and lbpB), genes that are part of the two-partner secretion system tpsA2 (NMB1768) and tpsB3 (NMB1780), genes involved in DNA synthesis, including DNA polymerase I (NMB1982) and DNA glycosylase (NMB0698), as well as three genes coding for transporters (NMB0060, NMB0586, and NMB0705) and four genes that are part of the Nf1 phage (NMB0975, NMB1544, NMB1545, and NMB1633). In turn, cysA and cysW genes, encoding sulfate transport system permeases involved in sulfur acquisition, a putative HTH-type transcriptional regulator (NMB0398), as well as genes involved in RNA synthesis, such as rpoC (NMB0133), an ATP dependent-RNA helicase (NMB1368), the glutamyl-tRNA synthetase gene glnS (NMB1560), NMB1866, coding for a tRNA modification enzyme, and three genes (NMB0822, NMB1587, and NMB1664) involved in protein turnover (proteases/peptidases), all were significantly induced in both strains.

Core genes differentially expressed in only one of the strains on adhesion to FaDu epithelial cells.

Two hundred seventy-one genes of the core genome were differentially expressed only in strain MC58 on adhesion to FaDu cells, with 138 genes being upregulated and 133 being downregulated. Genes encoding proteins for translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (COG J), as well as genes for nucleotide transport and metabolism, were significantly upregulated. Accordingly, among the core genes specifically upregulated only in MC58 were genes involved in tryptophan (aroA, aroB, aroC, aroK, and trpF), pyrimidine (pyrB and pyrI), and folate (metF) biosynthesis, genes for Tfp biogenesis (pilD and pilW), genes that are part of an operon coding for multidrug resistance (mtrD andmtrE), the two RNase genes rnc (NMB0686) and pnp (NMB0758), and comE1, coding for a DNA-binding competence protein. Genes that were significantly downregulated only in MC58 include members of the maf1 locus mafA1 and mafB1; a putative TonB-dependent receptor, NMB0293; tpsA2 (NMB0497), tpsA3 (NMB1779), and tpsS7 (NMB1772); genes coding for an RTX toxin (NMB1403) and an RTX toxin cassette (NMB1409), respectively; sodC, coding for superoxide dismutase; clpX, encoding an ATP-dependent Clp protease; and NMB1550, which is part of the Nf1 prophage.

In turn, 96 shared genes were differentially expressed only in strain α710 on adhesion to FaDu cells. Among the 46 upregulated genes were 18 genes for proteins involved in translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (COG J), a transcriptional regulator (NMB1843), fbpA (involved in iron acquisition), a gene for a putative ABC transporter (NMB1051), acnB, which encodes aconitate hydratase, and two genes coding for the IS1655 transposase (NMB0834 and NMB0911). The 50 downregulated genes comprised genes involved in Tfp biogenesis (pilN, pilO, and pilP), a gene cluster encoding ATP synthase subunits (atpA, atpE, atpF, atpG, and atpH), and genes for the immunogenic iron-regulated outer membrane proteins fetA and fetB.

Comparative transcriptomics of adherent strain MC58 and strain α710.

In principle, differences in the expression of shared core genes upon adhesion to FaDu cells also could derive from differences in gene expression patterns in response to the medium RPMI 1640 in which the infection experiments were carried out. Therefore, we chose a common reference design for the transcriptome comparisons that allows for a direct comparison of the transcriptional profiles of adherent strains only and therefore compensates for such possible medium effects. Accordingly, on adhesion to FaDu cells, 136 genes were differentially expressed in both strains. The 55 genes that were upregulated in MC58 compared to their regulation in α710 comprised, among others, genes coding for proteins required for amino acid transport and metabolism (COG E), including argH, aroA, aroB, ilvC, and gdhA, genes for ATP synthase subunits (atpA, atpD, and atpG), the siaB and siaC genes, involved in capsule synthesis, and an operon coding for subunits of the Na+-translocating NADH-quinone reductase (nqrB, nqrC, and nqrD). In turn, the 81 genes that were specifically downregulated in MC58 compared to their level in α710 were enriched for genes involved in inorganic ion transport and metabolism (COG P) and included, among others, 14 genes encoding ribosomal proteins, two sigma factor-encoding genes (rpoD and NMB2144), the tuf genes for the elongation factor Tu (NMB0124 and NMB0139), clpX (encoding the ATP-dependent Clp protease), a tpsA TPS gene (NMB1768), two genes encoding putative ABC transporters (NMB0586 and NMB0588), and one involved in methionine transport (NMB1948).

Expression of MC58-specific genes upon adhesion to FaDu epithelial cells.

The analysis of the gene expression profile in strain MC58 revealed that of the 256 MC58-specific genes, 12 were significantly upregulated, including a substantial part of the Mu-like prophage MuMenB (NMB1101 to NMB1105) (48), which thus indicates a possible role at least for these phage-carried genes for adhesion to FaDu cells.

In turn, 56 genes were significantly downregulated on adhesion to FaDu cells compared to results for growth in RPMI (Table 3; also see Table S5 in the supplemental material). Among others, these comprise five genes, including tpsS5 (NMB0509), located on IHT-B; three genes (NMB1764, NMB1765, and NMB1771) located on IHT-C; the three genes NMB1212, NMB1213, and tpsA3 (NMB1214) on cMME-bfrAlipA; NMB1402, NMB1403, and NMB1408, all on RTX island I; and a possible operon coding for silent 3′ cassettes at the maf-3 locus (NMB2106 to NMB2121) (Fig. 2). Of note, all of these genes differ in their Karlin signature from the rest of the MC58 genome, suggesting that they were acquired via horizontal gene transfer.

DISCUSSION

Experimental approaches for the in vivo study of meningococcal pathogenicity factors have been severely hampered by the lack of appropriate animal models (4), and either epidemiological approaches have been used to identify associations between meningococcal genes and pathogenicity (11, 45) or cell culture experiments have been used to analyze the interaction between bacteria and host cells (9, 83). However, the latter often is used only with a single strain, and both approaches were designed to assess the effect only of certain candidate genes. Accordingly, to search for genetic factors in serogroup B meningococci that might affect the interaction of the bacteria with host cells and, thus, virulence in an unbiased manner, we performed a systematic comparison of the genomes and transcriptomes of two serogroup B meningococcal strains having markedly different epidemiological properties (Table 1).

Given the high genomic variability seen in N. meningitidis (66), the two serogroup B strains MC58 and α710 have a remarkably similar genomic makeup, with a high degree of genome synteny and with highly conserved sequences of shared housekeeping genes (Fig. 1 and 2). In particular, they share a number of mobile elements that are absent from the other sequenced meningococcal genomes, such as IHT-B and IHT-C (30, 72), which further supports an origin from a common ancestor. In light of this marked genomic similarity, some of the observed genomic differences are more striking, such as the high variability in the number and chromosomal location of IS elements and, in particular, of IS1655 and the prophage Nf1. Given that IS elements are deleterious for genome maintenance and that N. meningitidis strains consequently undergo high selection pressure to inactivate IS elements (42), there probably was not enough time for selection to inactivate these elements due to the presumed recent ancestry of both strains (58). Alternatively, IS elements either are selectively neutral or these mobile elements confer a fitness advantage, as they might act as mutators on chromosome structure and thereby increase the genetic adaptability of the population (2, 17).

Another remarkable difference between both genomes is the difference in gene content. Of the approximately 2,000 genes in each serogroup B genome, 156 genes from α710 have no functional ortholog in the MC58 genome and 256 genes from MC58 have no functional ortholog in the α710 genome, and 157 genes in the genome of strain MC58 and 100 genes in the genome of strains α710 do not even have a homolog in the other genome. However, whether these genes are predominantly selfish DNA or contribute to bacterial fitness is an open issue. A number of prophage MuMenB/NeisMu1 genes are indeed activated in MC58 upon adhesion to nasopharyngeal cells, which suggests that these prophage genes contribute to the interaction of the bacterium with its host, and Masignani et al. (48) showed that three of the MuMenB/NeisMu1 genes code for surface-associated antigens that also are able to induce bactericidal antibodies. On the other hand, genes with atypical nucleotide composition are mostly repressed upon contact with host cells (Fig. 2). In particular, given that TPS proteins recently were found to contribute to the adhesion of N. meningitidis to epithelial cells (63), it was surprising that the TPS-encoding gene NMB1214 (TpsA3) and other TPS proteins on TPS1 (IHT-C) and TPS2 (IHT-B) (Fig. 2; also see Table S5 in the supplemental material) were significantly downregulated upon adhesion. This observation is also in line with previous findings by Grifantini et al. (25), who could not find an activation of this class of paralogous genes upon adhesion to epithelial cells. Therefore, the role of these genes in meningococcal infection obviously requires more experimental investigation.

There is increasing evidence from in vitro cell culture studies suggesting that the ability of the meningococcus to inflict damage is correlated with adherence to human epithelial and endothelial cells (9, 83), and in line with findings by Watanabe et al. in disease- and carriage-associated strains from Japan (75), the invasive strain MC58 indeed exhibited higher infectious abilities in adherence and invasion than the carriage strain (Table 1). Although adhesion to and invasion of human epithelial cells by N. meningitidis is a multifactorial process, these differences might at least in part be explained by the different repertoire and sequences of major as well as minor adhesins. Accordingly, a number of epidemiological analyses demonstrated that genes coding for surface proteins, such as the meningococcal opa repertoire (6), nadA (14), or hmbR (coding for a hemoglobin receptor) (29), segregate differently between carriage and disease isolates, and the comparison of the two serogroup B genomes indeed revealed a substantial variability in the sequence and number of specific outer membrane proteins (Table 2). Whereas both strains used in the present study express a type B capsule, Opa adhesins as well as a class I Tfp α710 strain entirely lack OpcA and NadA, and both strains also differ in the amino acid sequences of major adhesins such as PilE and minor adhesins such as NhhA. In light of the importance of outer membrane proteins for the adhesion to host cells, it is further intriguing that the respective genes were not significantly enriched among the upregulated genes. The induction of the meningococcal outer membrane proteins upon contact with host cells, however, occurs in a time-dependent manner (25), and it is plausible that their induction takes place at earlier time points that were not investigated in this study. Finally, the high variability in the genetic architecture of the RTX, TPS, and maf loci together with the high sequence diversity of the encoded orthologous proteins supports an important role for these classes of genes in meningococcal infection biology; however, this remains to be fully resolved (53, 55, 63, 81).

Similarly, the repertoire of LOS (core) biosynthesis genes differs between both strains. Whereas the genome of α710 harbors a type III Lgt-1 locus, MC58 has a type VI locus missing lgtC (88), which together with the presence of phase variation might result in the expression of alternative structures, as can be shown by tricine gel electrophoresis (Heike Claus, unpublished data). Differences in the PorA and factor H binding protein sequences (fHBP) as well as in the repertoire of glycosyl transferases probably contribute to the different resistance levels of both strains against human serum despite the identical serogroup B capsule (43, 64).

In addition to the well-acknowledged importance of bacterial surface proteins for the interaction of bacterial and eukaryotic cells, there also is growing evidence that a fine-tuned interplay between central metabolic pathways exists in many (facultative) pathogenic bacteria, which affects virulence gene expression (18). In N. meningitidis, recent epidemiological analyses further suggest that combinations of allelic variants of housekeeping genes are associated with very small differences in transmission efficiency among hosts, and these data also point at an important impact of metabolism on virulence in this species (5). Likewise, genomic comparisons by Rusniok et al. (60) demonstrated that Neisseria species colonizing the human nasopharynx (N. meningitidis and N. lactamica), but not N. gonorrhoeae, which colonizes the genital tract, have a complete metabolic pathway involved in sulfate reduction. In line with these findings, the activation of cysW and cysA in both strains indeed suggests that the acquisition and metabolism of sulfur is important during the adhesion process in meningococci (25) and contribute to the potential for nasopharyngeal colonization and virulence.

Our data further demonstrate that the interaction with epithelial cells leads to a large-scale differential reorganization of meningococcal transcription profiles. The significant induction of genes coding for proteins involved in translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (COG J) and the downregulation of genes involved in DNA synthesis, like polA and NMB0698 (DNA glycosylase), indicates that DNA replication is reduced on adhesion in meningococci, and most of the metabolic activity is directed toward RNA/protein synthesis and turnover during this process (Fig. 5). The reduced bacterial growth during adhesion reduces the energy demand of the bacterial cell (24), and the altered expression of the gene cluster coding for ATP synthase subunits between the two serogroup B strains further shows that the energy demands during the process of adhesion to nasopharyngeal cells between the two serogroup B strains are indeed quite different. Of note, transcriptome analysis recently revealed a key role for tryptophan metabolism in biofilm formation in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium (27), and the upregulation of five genes of the tryptophan biosynthesis pathway in MC58 upon adhesion to epithelial cells therefore suggests a possible role of tryptophan metabolism in meningococcal biofilm formation (39). Likewise, as suggested by the differential expression of sodC and clpX, there might be differences in the stress response between both strains upon adhesion to human nasopharyngeal cells, and a number of metabolic genes as well as genes involved in transcription and translation were expressed differentially in the two serogroup B strains (Fig. 4 and Table 3; also see Table S4 and S5 in the supplemental material). In line with previous findings for MC58 by Grifantini et al. (24, 25), these included two RNase genes (rnc and pnp) and metF (involved in folate biosynthesis), which were induced only in strain MC58 on adhesion, and genes for the elongation factor Tu (NMB0139) and an NADP-specific glutamate dehydrogenase (gdhA) were differentially regulated in adherent MC58 and adherent α710 bacteria. Combined with the finding that mutants lacking the above-mentioned genes were found to be attenuated in an infant rat model of meningococcal infection (74), these observations indicate that differences in the transcriptional regulation of housekeeping genes plays an important role in vivo.

The finding that cytoplasmic and inner membrane proteins are significantly more conserved than genes coding for outer membrane proteins and, in particular, are more conserved than genes subject to gene conversion (Fig. 3 and 4) further suggests that meningococci have evolved mechanisms like gene conversion to increase genetic diversity at the affected loci and thus to successfully escape immune selection (26). Immune selection might not only alter the antigenicity of certain surface proteins (7) but also affect their interaction with host cell receptors and, thus, virulence. Another major evolutionary force shaping meningococcal genome make-up is genetic drift (19) resulting from repeated transmission bottlenecks (91). It leads to the generation of pseudogenes not only for IS elements but also for proteins involved in, e.g., cell metabolism and gene regulation (37), and in the two serogroup B genomes almost half of the pseudogenes code for housekeeping functions, including two genes for AraC/XylS-type transcriptional regulators. Notably, members of this family were found in other bacterial species to have regulatory functions in carbon metabolism, stress response, and virulence (21), and the differences in the repertoire of transcription factors might thus at least in part explain the observed differences in gene expression between both strains upon adhesion to human nasopharyngeal cells.

In summary, despite high levels of the sequence conservation of metabolic genes, there are considerable differences in their expression in both strains upon adhesion to human nasopharyngeal cells. Taken together with the different repertoire of surface adhesins, these findings might explain the different pathogenic potential of both strains and clearly support the concept of a polygenic nature of meningococcal virulence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathrin Engelhard for expert technical assistance, Gabriele Gerlach for the critical reading of the manuscript, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

The work was supported by the German Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) in the context of the PathoGenoMik and PathoGenoMik-Plus funding initiatives (grant 0313801A).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arber, W. 2000. Genetic variation: molecular mechanisms and impact on microbial evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentley, S. D., G. S. Vernikos, L. A. Snyder, C. Churcher, C. Arrowsmith, T. Chillingworth, A. Cronin, P. H. Davis, N. E. Holroyd, K. Jagels, M. Maddison, S. Moule, E. Rabbinowitsch, S. Sharp, L. Unwin, S. Whitehead, M. A. Quail, M. Achtman, B. Barrell, N. J. Saunders, and J. Parkhill. 2007. Meningococcal genetic variation mechanisms viewed through comparative analysis of serogroup C strain FAM18. PLoS Genet. 3:e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourdoulous, S., and X. Nassif. 2006. Mechanisms of attachment and invasion, p. 257-272. In M. Frosch and M. C. Maiden (ed.), Handbook of meningococcal disease. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 5.Buckee, C. O., K. A. Jolley, M. Recker, B. Penman, P. Kriz, S. Gupta, and M. C. Maiden. 2008. Role of selection in the emergence of lineages and the evolution of virulence in Neisseria meningitidis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:15082-15087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callaghan, M. J., C. Buckee, N. D. McCarthy, A. B. Ibarz Pavon, K. A. Jolley, S. Faust, S. J. Gray, E. B. Kaczmarski, M. Levin, J. S. Kroll, M. C. Maiden, and A. J. Pollard. 2008. Opa protein repertoires of disease-causing and carried meningococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3033-3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callaghan, M. J., C. O. Buckee, K. A. Jolley, P. Kriz, M. C. Maiden, and S. Gupta. 2008. The effect of immune selection on the structure of the meningococcal opa protein repertoire. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capecchi, B., J. Adu-Bobie, F. Di Marcello, L. Ciucchi, V. Masignani, A. Taddei, R. Rappuoli, M. Pizza, and B. Arico. 2005. Neisseria meningitidis NadA is a new invasin which promotes bacterial adhesion to and penetration into human epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 55:687-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carbonnelle, E., D. J. Hill, P. Morand, N. J. Griffiths, S. Bourdoulous, I. Murillo, X. Nassif, and M. Virji. 2009. Meningococcal interactions with the host. Vaccine 27:B78-B89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carver, T. J., K. M. Rutherford, M. Berriman, M. A. Rajandream, B. G. Barrell, and J. Parkhill. 2005. ACT: the artemis comparison tool. Bioinformatics 21:3422-3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caugant, D. A., and M. C. J. Maiden. 2009. Meningococcal carriage and disease-population biology and evolution. Vaccine 27:B64-B70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caugant, D. A., G. Tzanakaki, and P. Kriz. 2007. Lessons from meningococcal carriage studies. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 31:52-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Claus, H., M. C. Maiden, D. J. Wilson, N. D. McCarthy, K. A. Jolley, R. Urwin, F. Hessler, M. Frosch, and U. Vogel. 2005. Genetic analysis of meningococci carried by children and young adults. J. Infect. Dis. 191:1263-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comanducci, M., S. Bambini, D. A. Caugant, M. Mora, B. Brunelli, B. Capecchi, L. Ciucchi, R. Rappuoli, and M. Pizza. 2004. NadA diversity and carriage in Neisseria meningitidis. Infect. Immun. 72:4217-4223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dehio, C., S. D. Gray-Owen, and T. F. Meyer. 1998. The role of neisserial Opa proteins in interactions with host cells. Trends Microbiol. 6:489-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dietrich, G., S. Kurz, C. Hubner, C. Aepinus, S. Theiss, M. Guckenberger, U. Panzner, J. Weber, and M. Frosch. 2003. Transcriptome analysis of Neisseria meningitidis during infection. J. Bacteriol. 185:155-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Earl, D. J., and M. W. Deem. 2004. Evolvability is a selectable trait. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:11531-11536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenreich, W., T. Dandekar, J. Heesemann, and W. Goebel. 2010. Carbon metabolism of intracellular bacterial pathogens and possible links to virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:401-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser, C., W. P. Hanage, and B. G. Spratt. 2005. Neutral microepidemic evolution of bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:1968-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frosch, M., and U. Vogel. 2006. Structure and genetics of the meningococcal capsule, p. 145-162. In M. Frosch and M. C. Maiden (ed.), Handbook of meningococcal disease. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 21.Gallegos, M. T., R. Schleif, A. Bairoch, K. Hofmann, and J. L. Ramos. 1997. Arac/XylS family of transcriptional regulators. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:393-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galperin, M. Y., and E. Kolker. 2006. New metrics for comparative genomics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17:440-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardy, J. L., M. R. Laird, F. Chen, S. Rey, C. J. Walsh, M. Ester, and F. S. Brinkman. 2005. PSORTb v. 2.0: expanded prediction of bacterial protein subcellular localization and insights gained from comparative proteome analysis. Bioinformatics 21:617-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grifantini, R., E. Bartolini, A. Muzzi, M. Draghi, E. Frigimelica, J. Berger, F. Randazzo, and G. Grandi. 2002. Gene expression profile in Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria lactamica upon host-cell contact: from basic research to vaccine development. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 975:202-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grifantini, R., E. Bartolini, A. Muzzi, M. Draghi, E. Frigimelica, J. Berger, G. Ratti, R. Petracca, G. Galli, M. Agnusdei, M. M. Giuliani, L. Santini, B. Brunelli, H. Tettelin, R. Rappuoli, F. Randazzo, and G. Grandi. 2002. Previously unrecognized vaccine candidates against group B meningococcus identified by DNA microarrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:914-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta, S., M. C. Maiden, I. M. Feavers, S. Nee, R. M. May, and R. M. Anderson. 1996. The maintenance of strain structure in populations of recombining infectious agents. Nat. Med. 2:437-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]