Abstract

An extremely thermophilic bacterium, Thermus thermophilus HB8, is one of the model organisms for systems biology. Its genome consists of a chromosome (1.85 Mb), a megaplasmid (0.26 Mb) designated pTT27, and a plasmid (9.3 kb) designated pTT8, and the complete sequence is available. We show here that T. thermophilus is a polyploid organism, harboring multiple genomic copies in a cell. In the case of the HB8 strain, the copy number of the chromosome was estimated to be four or five, and the copy number of the pTT27 megaplasmid seemed to be equal to that of the chromosome. It has never been discussed whether T. thermophilus is haploid or polyploid. However, the finding that it is polyploid is not surprising, as Deinococcus radiodurans, an extremely radioresistant bacterium closely related to Thermus, is well known to be a polyploid organism. As is the case for D. radiodurans in the radiation environment, the polyploidy of T. thermophilus might allow for genomic DNA protection, maintenance, and repair at elevated growth temperatures. Polyploidy often complicates the recognition of an essential gene in T. thermophilus as a model organism for systems biology.

The extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus is a Gram-negative aerobic bacterium that can grow at temperatures ranging from 50°C to 82°C (33, 34). The genome sequences of two strains, HB27 and HB8, are available (13; see also http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=genome&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=Overview&list_uids=530). The genome of the HB27 strain consists of a chromosome (1.89 Mb) and a megaplasmid (0.23 Mb), while that of the HB8 strain includes a plasmid (9.3 kb) coupled with a chromosome (1.85 Mb) and a megaplasmid (0.26 Mb) (13; see also the NCBI website [above]). This organism has attracted attention as one of the model organisms for genetic manipulation, structural genomics, and systems biology (9, 44). In the case of the HB8 strain, the Structural and Functional Whole-Cell Project for T. thermophilus HB8, which aims to understand the mechanisms of all the biological phenomena occurring in the HB8 cell by investigating the cellular components at the atomic level on the basis of their three-dimensional (3-D) structures, is in progress (44). In addition to the stability and ease of crystallization of thermophilic proteins, natural competency and an established genetic engineering system add value to T. thermophilus HB8 as a model organism (12, 14, 23, 44). Thermostabilized resistances against antibiotics such as kanamycin (Km), hygromycin (Hm), and bleomycin (Bm), which were developed by directed evolution, have also encouraged the system (5, 6, 16, 29; Y. Koyama, unpublished data).

However, we had been puzzled about several gene disruptions in T. thermophilus HB8 that resulted from replacement with the drug resistance gene. Even if drug-resistant transformants were obtained, the target gene of the transformants had not often been deleted. The target gene, probably an essential gene, seemed to coexist with the drug resistance gene. A similar phenomenon has been reported in the deletion of the recJ gene in Deinococcus radiodurans (7). Repeated observation of this phenomenon suggested that T. thermophilus HB8 might possess multiple genomic copies. Many bacteria, including the most-studied bacteria Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, essentially carry a single genomic copy per cell and are genetically haploid organisms (3, 10, 42, 43). On the other hand, several bacteria have been proposed to be polyploid, harboring multiple genomic copies per cell. They include Buchnera species (21, 22), Blattabacterium species (24), Epulopiscium species (1, 4), Borrelia hermsii (20), Azotobacter vinelandii (28, 35), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (41), D. radiodurans (11, 27), a few Lactococcus lactis laboratory strains (26), and many cyanobacteria (2, 25, 37). In particular, D. radiodurans, an extremely radioresistant bacterium, has been suggested to be closely related to the genus Thermus by comparative genomic analysis (13, 32). The radioresistant bacterium carries four genome copies per cell in the stationary phase and up to 10 copies per cell during exponential growth (11, 27). In contrast with this well-known polyploidy of D. radiodurans, no report on the genomic copy number of Thermus has been done, in spite of the attention it has received as a model organism. Therefore, in this paper, the potential polyploidy and the genomic copy number were first studied in T. thermophilus HB8.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

T. thermophilus HB8 and its derivatives were grown at 70°C in TR medium as a rich medium (12) or at 55°C in synthetic medium as a nutritionally defined medium (40), and 1.5% gellan gum with 1.5 mM CaCl2 and 1.5 mM MgCl2 was added to TR medium for plates (12). Km (500 μg/ml), Hm (100 μg/ml), and/or Bm (20 μg/ml) were added to the medium when needed. B. subtilis strain BEST7003, in which a linearized pBR322 sequence was inserted into the proB gene, has been described previously (19). This genomic pBR322 sequence is called GpBR. B. subtilis strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or at 20°C in Spizizen medium as a synthetic medium (39).

Plasmids and materials.

The E. coli plasmids for the deletion of T. thermophilus HB8 genes (jrn, polX, TTHB090, and TTHB222) were provided by Kuramitsu (Osaka University and RIKEN) (44). The plasmid contains a DNA fragment in which a Km resistance gene (highly thermostable kanamycin [HTK] or Kmr) (16) is sandwiched between the 500-bp fragments just upstream and downstream of the target gene. The Kmr gene can be clipped out with KpnI and PstI enzymes. E. coli plasmid pCISP401 derived from pBR322 has been described previously (18). An Hm resistance gene (Hmr) (Koyama, unpublished) for T. thermophilus HB8 was kindly donated by Koyama (AIST), whereas a Bm resistance gene (high-temperature Streptoalloteichus hindustanus blmA [HTS] or Bmr) (5) was chemically synthesized by TaKaRa Bio. The LA Taq hot-start version for PCR and restriction enzymes were from TaKaRa Bio.

Transformation and gene deletion.

Transformation and gene deletion of T. thermophilus HB8 were carried out using the following procedures (12). An overnight culture was diluted 1:60 with TR medium supplemented with 0.4 mM CaCl2 and 0.4 mM MgCl2 and shaken at 70°C for 2 h. Four hundred microliters of this culture was mixed with a 50-μl DNA solution. The mixture was shaken at 70°C for 1 h and spread on plates. The plates were incubated overnight at 70°C. To delete the T. thermophilus HB8 genes in this experiment, the Kmr gene of the plasmid from Kuramitsu was replaced with the Hmr and Kmr or Hmr and Bmr marker, as shown in Fig. 1. To achieve proper substitution by two homologous recombinations as shown in Fig. 1, 1 μg of the plasmid was used for transformation after being linearized by ScaI and NdeI digestion.

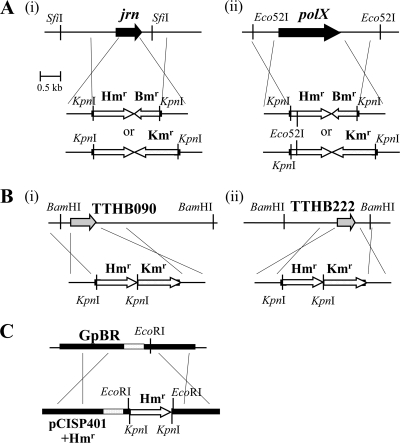

FIG. 1.

Constructs for analyses of T. thermophilus HB8 polyploidy. (A) The jrn (i) and the polX (ii) gene-null mutants in T. thermophilus HB8. The gene was deleted by replacement with the Hmr and Kmr or the Hmr and Bmr marker. The top figure represents the chromosomal region around the jrn gene, and the bottom figures represent the DNA fragments used for deletion. The crossings indicate homologous recombination. (B) The TTHB090 (i) or TTHB222 (ii) gene-null mutants to determine the quantity of the megaplasmid pTT27. In the Δjrn strain labeled by the Hmr and Bmr marker, the TTHB090 or TTHB222 gene located on the pTT27 was deleted by replacement with the Hmr and Kmr marker. The top figure represents the pTT27 region around the gene, and the bottom figure represents a DNA fragment for deletion. (C) B. subtilis possessing the Hmr sequence used for T. thermophilus HB8. This strain was used as a haploid control for the quantitation of the chromosomal copy number of T. thermophilus HB8 in Fig. 6. The top figure represents the chromosomal region around the pBR322 sequence (GpBR) of BEST7003, and the bottom figure represents the pCISP401 (pBR322 derivative) plasmid cloning Hmr. The Hmr amplified by PCR was inserted into the EcoRI site of pCISP401, and two KpnI sites were introduced just inside the resultant two EcoRI sites by PCR primers. The top and bottom shaded regions represent the tetracycline and chloramphenicol resistance genes for B. subtilis, respectively.

B. subtilis BEST7003 was transformed with a pCISP401+Hmr plasmid, in which the Hmr amplified by PCR was inserted into an EcoRI site of pCISP401 (Fig. 1C), as described previously (18). The pCISP401+Hmr plasmid is not a plasmid for B. subtilis but rather an E. coli plasmid harboring the chloramphenicol gene for B. subtilis. Therefore, as shown in Fig. 1C, the tetracycline-sensitive and chloramphenicol-resistant transformant necessarily resulted in possessing the Hmr gene within the GpBR region on the chromosome and was used for quantitation of ploidy as a haploid control.

Southern hybridization.

Genomic DNAs were prepared by a liquid isolation method (36), digested by a restriction enzyme, and used for Southern hybridization analyses. Probes for the analyses were prepared by using an internal region of Hmr, Kmr, Bmr, or the deleted genes amplified by PCR as a template for the DIG high prime DNA labeling kit (Roche). In this paper, the results with the Kmr or Bmr probe are not shown. Anti-DIG-alkaline phosphatase Fab fragments and CDP-Star were used for detection according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche).

Chromosome separation kinetics.

The Δjrn strain carrying both chromosomes labeled by the Hmr and Kmr or the Hmr and Bmr marker was precultured overnight at 70°C in TR medium containing both Km and Bm. The cells were harvested, washed with the antibiotic-free TR medium, and then inoculated into the TR medium for the following assay. To determine the chromosome separation kinetics, the culture at 70°C was sampled at regular intervals, and the number of viable cells was determined by counting the colonies on the antibiotic-free TR plate. The drug resistance of each colony was characterized by restreaking on the plate containing Km or Bm.

Quantitation of ploidy.

B. subtilis possessing the Hmr sequence was grown in Spizizen medium at 20°C until the stationary phase at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.7. On the other hand, T. thermophilus HB8 possessing the Hmr and Bmr marker was grown in synthetic medium at 55°C until exponential growth (OD600 of 0.8) or until the stationary phase (OD600 of 1.7). The cell density was determined with a bacterial-counting chamber and by counting colonies on plates. The B. subtilis cells were mixed with a specific amount of the T. thermophilus HB8 cells at various ratios, and from the mixtures, genomic DNAs were prepared as described above. The genomic DNAs were digested by KpnI and used for Southern analyses with the Hmr probe. The signals corresponding to the Hmr sequence were detected and quantified using the Molecular Imager FX (Bio-Rad).

Determination of the pTT27 copy number.

In the Δjrn strain carrying the Hmr and Bmr marker, a TTHB090 or TTHB222 gene was replaced by the Hmr and Kmr marker. The resultant strain was grown in the synthetic medium at 55°C until exponential growth (OD600 of 0.8) or until the stationary phase (OD600 of 1.7). Genomic DNA was prepared from each culture, digested by KpnI, and used for Southern analyses with the Hmr probe. Detection and quantification were performed as described above.

RESULTS

T. thermophilus HB8 is polyploid.

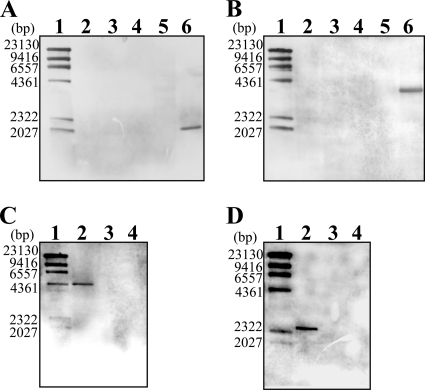

To validate polyploidy in T. thermophilus HB8, we tested whether or not two different genes can coexist at the same position on the chromosome. To do this, we examined whether a drug resistance gene displacing a nonessential gene was replaced by or could coexist with another drug resistance gene. The jrn gene encoding junction RNase was selected as a nonessential gene (31). As shown in Fig. 1Ai, T. thermophilus HB8 was transformed with a DNA fragment carrying an Hmr and Kmr or an Hmr and Bmr marker. Resultant transformants on TR plates containing Km or Bm were checked by colony PCR with primers located outside the jrn gene. In Fig. 2 A, the amplified fragment for the transformant (lane 2 for Hmr and Kmr and lane 5 for Hmr and Bmr) was different from that for the wild type (lane 6), implying that the jrn gene could be replaced by the marker. Then, the replacement was confirmed by sequencing of the amplified fragment. Complete deletion of the gene was confirmed by Southern hybridization with the jrn internal probe (lanes 2 and 5 in Fig. 3 A), supported by the result of colony PCR in Fig. 2A. Furthermore, Southern analysis with the Hmr probe suggested that the marker was located at a single locus on the chromosome (lanes 2 and 5 in Fig. 4 A). Next, the Δjrn strain carrying the Hmr and Bmr marker was transformed by the DNA fragment used for the strain carrying the Hmr and Kmr marker and then spread on TR plates containing Km or both Km and Bm. As shown in Table 1, transformants grew not only on the Km plates but also on the plates containing both Km and Bm. Forty percent of transformants were estimated to exhibit both resistances. To test the presence of both markers, the transformants on the plates containing both Km and Bm were checked by colony PCR as described above. As shown in lanes 3 and 4 of Fig. 2A, two fragments were amplified, and they exhibited sizes similar to that of the fragment observed in the Δjrn strain carrying the Hmr and Kmr or the Hmr and Bmr marker (lanes 2 and 5). Sequencing of them indicated that the upper fragments in lanes 3 and 4 were identical to that in lane 2, and the lower fragments were identical to that in lane 5. In the transformants on the plates containing both Km and Bm, the Hmr and Kmr and Hmr and Bmr markers were suggested to be located at the same locus (corresponding to the jrn gene) on the chromosome. If T. thermophilus HB8 was haploid, two markers would never coexist at the same locus on the chromosome in a cell. The transformants derived from the single colony were grown in a liquid medium containing both antibiotics, and then genomic DNA was prepared and used for Southern hybridization analyses. As shown in Fig. 4A, the analysis using the Hmr probe indicated that the transformants could possess both chromosomes in which the jrn gene was replaced by the Hmr and Kmr or Hmr and Bmr marker. Furthermore, the different signal intensities between the Hmr and Kmr and Hmr and Bmr markers imply that three or more copies of the chromosome could exist (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 4).

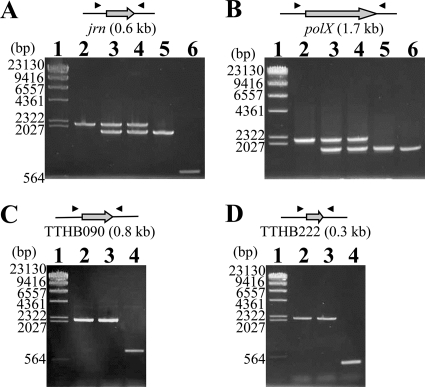

FIG. 2.

Confirmation of transformants by colony PCR. Colony PCR of the transformants of T. thermophilus HB8 was performed with primers located outside the deleted gene. The black triangles in the upper figures indicate the primers. The results of the jrn and the polX gene-null mutants are shown in panels A and B, respectively. Lane 1, λ/HindIII digest marker; lane 2, the transformant of the wild-type strain by the DNA fragment carrying the Hmr and Kmr marker; lanes 3 and 4, the transformants of the Hmr and Bmr strain (corresponding to the strain in lane 5) by the DNA fragment carrying the Hmr and Kmr marker; lane 5, the transformant of the wild-type strain by the DNA fragment carrying the Hmr and Bmr marker; lane 6, the wild-type strain. The results of the TTHB090 and the TTHB222 gene-null mutants are shown in panels C and D, respectively. For deletion of these genes, the Δjrn strain carrying the Hmr and Bmr marker (corresponding to the strain in lane 5 of panel A) was used as shown in Fig. 1B. Lane 1, λ/HindIII digest marker; lanes 2 and 3, the transformants of the Δjrn strain by the DNA fragment carrying the Hmr and Kmr marker; lane 4, the Δjrn strain. All of these amplified DNA fragments were checked by DNA sequencing. The numbers along the left side of the gel represent the DNA fragment size of each marker (lane 1).

FIG. 3.

Confirmation of null mutants by Southern analysis. The null mutants of T. thermophilus HB8 as shown in Fig. 2 were confirmed by Southern hybridization analysis with an inside probe for each gene. The genomic DNAs were digested by SfiI for jrn (A), Eco52I for polX (B), and BamHI for TTHB090 (C) and TTHB222 (D). (A and B) Lane 1, λ/HindIII digest marker; lane 2, the mutant carrying the Hmr and Kmr marker; lanes 3 and 4, the transformants of the Hmr- and Bmr-labeled mutant (corresponding to the strain in lane 5) by the DNA fragment carrying the Hmr and Kmr marker; lane 5, the mutant carrying the Hmr and Bmr marker; lane 6, wild type. (C and D) Lane 1, λ/HindIII digest marker; lane 2, the Δjrn strain; lanes 3 and 4, the transformant of the Δjrn strain by the DNA fragment, in which the TTHB090 or TTHB222 gene is replaced with the Hmr and Kmr marker. The numbers along the left side of the gel represent the DNA fragment size of each marker (lane 1).

FIG. 4.

Multiple chromosomes in T. thermophilus HB8. The genomic DNAs of the jrn (A)- or polX (B)-null mutants of T. thermophilus HB8 were analyzed by Southern hybridization with a probe for the Hmr marker, as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Lane 1, λ/HindIII digest marker; lane 2, the mutant carrying the Hmr and Kmr marker; lanes 3 and 4, the transformants of the Hmr- and Bmr-labeled strain (corresponding to the strain in lane 5) by the DNA fragment carrying the Hmr and Kmr marker; lane 5, the mutant carrying the Hmr and Bmr marker; lane 6, wild type. Open and closed arrowheads indicate DNA fragments containing the Hmr and Kmr and Hmr and Bmr markers, respectively. The numbers along the left side of the gel represent the DNA fragment size of each marker (lane 1). The ratios of signal intensity between DNA fragments containing the Hmr and Kmr and Hmr and Bmr markers were estimated to be approximately 1:3 for lane 3 in panel A, 2:5 for lane 4 in panel A, 5:1 for lane 3 in panel B, and 3:2 for lane 4 in panel B.

TABLE 1.

Transformation efficiencies

| DNAa | Cell | No. of viable cells (CFU/ml)b | Transformants in CFU/ml (%)c |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km | Km and Bm | |||

| Δjrn | WT | 1.2 × 105 | 5.2 × 102 (0.43) | |

| Δjrn carrying the Hmr and Bmr marker | 1.1 × 105 | 6.6 × 102 (0.60) | 2.6 × 102 (0.24) | |

| ΔpolX | WT | 2.1 × 105 | 8.7 × 102 (0.41) | |

| ΔpolX carrying the Hmr and Bmr marker | 1.8 × 105 | 1.5 × 103 (0.83) | 4.1 × 102 (0.23) | |

One microgram of the plasmid for replacement by the Hmr and Kmr marker (Fig. 1A). To achieve proper substitutions by two homologous recombinations as shown in Fig. 1A, the plasmid linearized by ScaI and NdeI digestion was used.

Number of CFU formed on TR plates.

Number of CFU formed on TR plates containing Km or both Km and Bm. Parenthetical values represent transformants versus viable cells.

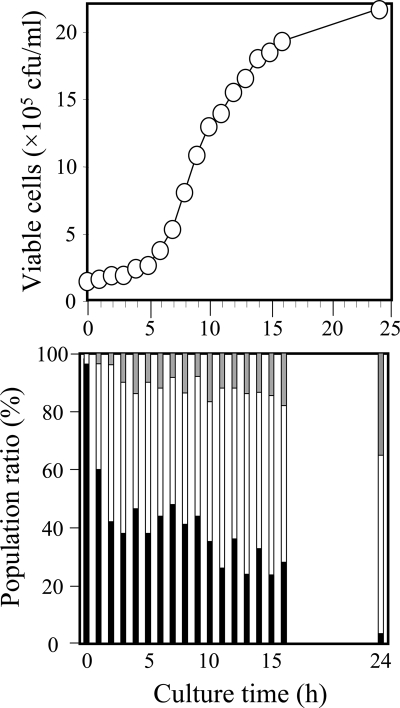

To examine chromosome separation, the Δjrn strain carrying both Km and Bm markers (the strain in lane 3 of Fig. 4A) was cultured in TR liquid medium without antibiotics and then spread on antibiotic-free plates. The drug resistance of the resultant colonies was characterized by restreaking on each plate containing Km or Bm. If the Hmr and Kmr and Hmr and Bmr markers are on the same single chromosome for any reason, the Bm and Km resistances would be genetically linked and therefore would be expected to be segregated together. As shown in Fig. 5, however, 40% of the cells lost one resistance after 1 h, compared with 4% at 0 h. The strain exhibited both Bm and Km resistances as long as both antibiotics were added, whereas one resistance seemed to be lost gradually once the addition of the antibiotics was ended. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the two markers are not on the same single chromosome but on separate chromosomes, suggesting that T. thermophilus HB8 might carry more than one chromosomal copy.

FIG. 5.

Chromosome separation kinetics. The Δjrn strain carrying both chromosomes labeled by the Hmr and Kmr or the Hmr and Bmr marker was cultured at 70°C in TR medium as described in Materials and Methods. At 0 h of culture time, the cells precultured in the presence of both Km and Bm were added to fresh antibiotic-free medium. The number of viable cells (top) was determined by counting the colonies on the antibiotic-free TR plate, and the drug resistance of each colony (bottom) was characterized by restreaking on the plate containing Km or Bm. In the bottom panel, the resistance only to Km or Bm is shown in white and gray, respectively, and that to both is shown in black.

These results were not specific to the jrn gene, since the same results were observed for the polX gene encoding DNA polymerase X (30) (Fig. 4B). The polX and jrn genes are located at opposite sides of the circular T. thermophilus HB8 chromosome (at the 1.097 and 0.194 positions on a 1.850-Mb genome). T. thermophilus HB8 must be a polyploid bacterium.

Chromosomal copy number.

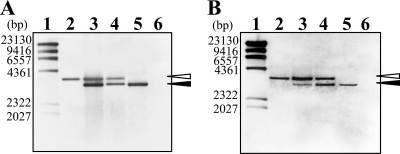

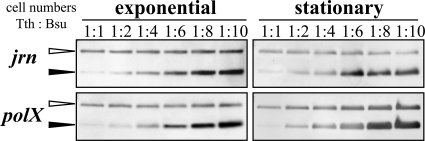

The number of copies of the chromosome per cell was determined in T. thermophilus HB8. B. subtilis labeled by the Hmr gene as shown in Fig. 1C was used as a haploid control, whereas the Hmr- and Bmr-labeled Δjrn strain mentioned above (corresponding to lane 5 in Fig. 4A) was used as T. thermophilus HB8. B. subtilis was grown in the Spizizen medium at the low temperature of 20°C for slow growth. T. thermophilus HB8 was grown in the synthetic medium at 55°C as described in Materials and Methods. The defined number of T. thermophilus HB8 cells was mixed with that of B. subtilis cells at various rates, and both genomic DNAs were extracted from the mixtures. T. thermophilus HB8 and B. subtilis used for this study possess a unique Hmr sequence per chromosome. The amount of each chromosomal DNA could be estimated by Southern analysis detecting the Hmr sequence on the chromosome. In Fig. 6, the upper signal corresponding to the Hmr and Bmr marker of T. thermophilus HB8 was compared with the lower signal corresponding to the Hmr gene of B. subtilis. Both during exponential growth and in the stationary phase, the upper signals were about the same as or slightly weaker than the lower ones in the 1:4 lane. In the 1:6 lane, however, the lower signals were more intensive than the upper ones. The measured intensities of the upper and lower signals were calculated to give agreement at a ratio of the cell number between 1:4 and 1:5. Therefore, the chromosomal copy number in T. thermophilus HB8 is about four or five times that of B. subtilis. The same analysis was carried out on the polX gene (Fig. 6). The estimate for the polX gene was also four or five copies of chromosome per cell both during exponential growth and in the stationary phase.

FIG. 6.

Quantitation of chromosomal copy number of T. thermophilus HB8. The defined number of T. thermophilus HB8 Δjrn or ΔpolX cells during exponential growth and in the stationary phase was mixed with that of B. subtilis cells as a haploid control at different ratios (1:1 to 1:10), and genomic DNAs of both cells were prepared from the mixtures. The genomic DNA mixtures were digested by KpnI and used for Southern analyses with a probe for the Hmr marker. As shown in Fig. 1A and C, T. thermophilus HB8 and B. subtilis are labeled by the Hmr and Bmr and the Hmr markers, respectively. Open and closed arrowheads indicate the Hmr and Bmr and the Hmr signals, respectively.

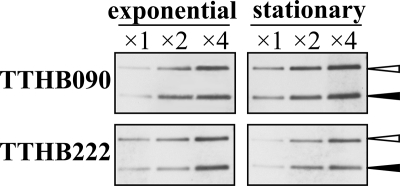

Copy number of pTT27.

The copy number of the pTT27 megaplasmid was also estimated on the basis of the chromosomal copy number. For the estimation, TTHB090 and TTHB222 genes encoding a hypothetical protein were selected. They are located at the 0.080 and 0.227 positions on the 0.257-Mb pTT27, respectively. In the Δjrn strain in which chromosomal DNA was previously labeled by the Hmr and Bmr marker, the TTHB090 or TTHB222 gene was replaced by an Hmr and Kmr marker, as shown in Fig. 1B. Absolute replacement was confirmed by sequencing of the amplified fragment by colony PCR and Southern analyses as described for Δjrn and ΔpolX (Fig. 2 and 3). These strains were grown in the synthetic medium at 55°C and used for the analysis. In Fig. 7, the result of ΔTTHB090 showed that the signal intensity of the Hmr and Bmr marker on the chromosome (top) was almost equal to that of the Hmr and Kmr marker on pTT27 (bottom), suggesting that the number of copies of pTT27 is almost the same as that of the chromosome. The result of ΔTTHB222 also agreed with this view.

FIG. 7.

Number of copies of the megaplasmid pTT27. Genomic DNA from the ΔTTHB090 or ΔTTHB222 strain (as described in the legend to Fig. 1B) during exponential growth or in the stationary phase was prepared, digested by KpnI, and used for Southern analyses with a probe for the Hmr marker. In the figure, ×2 and ×4 mean that 2- and 4-fold amounts of the digested DNAs were applied for electrophoresis. The strain possesses the Hmr and Bmr and the Hmr and Kmr markers replacing the jrn gene on the chromosome and the TTHB090 gene on the pTT27, respectively. Open and closed arrowheads indicate the Hmr and Kmr signal on pTT27 and the Hmr and Bmr signal on the chromosome, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Polyploidy of T. thermophilus.

In spite of the absence of discussion of the ploidy of Thermus species, T. thermophilus HB8 was believed to be haploid, as are E. coli and B. subtilis. However, the bacterium was found to be polyploid. Under a slow growth condition such as at 55°C in the synthetic medium, the HB8 strain was estimated to have four or five copies of the chromosome per cell both during exponential growth and in the stationary phase (Fig. 6), and as many pTT27 megaplasmids were determined to exist as the number of chromosomes in a cell (i.e., four or five copies per cell) (Fig. 7). Agreement between the number of copies of the chromosome and of the pTT27 megaplasmid might imply that some cooperating mechanisms regulating both copy numbers exists in T. thermophilus HB8 cells. The HB8 strain also harbors the pTT8 plasmid at 8 copies per chromosome, as has already been reported (15). In consequence, the HB8 strain turns out to contain approximately 30 to 40 copies of the plasmid pTT8 per cell.

T. thermophilus HB27, another representative strain of T. thermophilus, also seems to be polyploid, as its chromosome labeled by Bmr at the jrn gene coexisted in a cell with that labeled by Kmr at the gene (data not shown). Other Thermus species remain to be analyzed. However, as the closely related D. radiodurans and related cyanobacteria are well known to be polyploid cells, it seems likely that Thermus species might be generally polyploid.

Physiological function of bacterial polyploidy.

In D. radiodurans, multiple genome copies contribute to the reassembly of chromosomes shattered by exposure to desiccation and ionizing radiation (38, 45). The homologous recombinations between chromosomal fragments promote the reassembly. As is the case for D. radiodurans in a radiation environment, the polyploidy of T. thermophilus might allow for genomic DNA protection, maintenance, and repair at elevated growth temperatures. The recA inactivation in T. thermophilus HB27 has been reported to show extremely low viability depending on the growth temperature (8). Therefore, high growth temperatures could damage the genomic DNAs, and multiple genome copies would assist DNA repair by RecA. The cyanobacteria, which contain extremophiles such as thermophiles, psychrophiles, halophiles, xelophiles, and so on, also include many polyploid cells. Is the genomic polyploidy correlated with extreme environmental conditions causing DNA damage? It remains an interesting question whether hyperthermophilic bacteria such as Thermotoga or Aquifex species are haploid or polyploid. From another perspective, genomic polyploidy also has the potential to harbor accidental mutations to encourage adaptation to environmental changes. However, the potential of polyploidy often complicates the recognition of an essential gene in T. thermophilus. In the genetics of T. thermophilus, it should be carefully confirmed whether the gene in this bacterium was perfectly deleted or disrupted.

Chromosome separation and homologous recombination.

The chromosome separation mechanism in T. thermophilus HB8 is not understood. It is even unclear whether identical chromosomes are separated equally into two daughter cells or the chromosomes are randomly distributed. Although it has been less well known how multiple identical chromosomes in bacteria may be separated, in cyanobacteria, it has been suggested to be random (17, 37). In the absence of antibiotics, as shown in Fig. 5, T. thermophilus HB8 cells carrying both of the chromosomes labeled by the different markers tended to lose one of the two markers immediately. If each identical chromosome were separated into daughter cells, both of the markers would be retained in a cell. Therefore, the chromosome separation in T. thermophilus HB8 might also be a random process. However, this is not a definitive demonstration of random distribution of chromosomes in the HB8 strain because homologous recombination between chromosomes is likely to occur. In T. thermophilus HB8, replacement of a nonessential gene on all of four or five chromosomes by the drug resistance gene was established easily, as shown for jrn or polX. However, the result in Table 1 means that in at least 30 to 40% of transformants, all of four or five chromosomes are not necessarily replaced with the foreign marker. Completion of the replacement on all chromosomes is likely facilitated by subsequent homologous recombination between chromosomes. The previous report that the absence of RecA in T. thermophilus HB27 apparently results in a dramatic and generalized increase in the mutation rate (8) also implies that the high-frequency recombination between chromosomes could be involved in DNA repair. Therefore, this probable recombination between chromosomes might make it more difficult to monitor the chromosome separation in T. thermophilus HB8. For instance, in Fig. 5, although the number of viable cells after 1 h is at most 1.1-fold that at 0 h, as many as 40% of the cells have already lost one resistance after 1 h. In any case, the results in Fig. 4 and 5 are impossible in a haploid cell, and multiple chromosomal copies would make these phenomena possible.

Acknowledgments

We thank Noriko Nakagawa and Seiki Kuramitsu (Osaka University and RIKEN) for the gene deletion plasmids, Yoshinori Koyama (AIST) for the Hmr gene, and Miki Hasegawa for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 August 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angert, E. R., and K. D. Clements. 2004. Initiation of intracellular offspring in Epulopiscium. Mol. Microbiol. 51:827-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binder, B. J., and S. W. Chisholm. 1990. Relationship between DNA cycle and growth rate in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 6301. J. Bacteriol. 172:2313-2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bremer, H., and P. P. Dennis. 1996. Modulation of chemical composition and other parameters of the cell growth rate, p. 1553-1566. In F. C. Neidhardt (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 4.Bresler, V., W. L. Montgomery, L. Fishelson, and P. E. Pollak. 1998. Gigantism in a bacterium, Epulopiscium fishelsoni, correlates with complex patterns in arrangement, quantity, and segregation of DNA. J. Bacteriol. 180:5601-5611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brouns, S. J., H. Wu, J. Akerboom, A. P. Turnbull, W. M. de Vos, and J. van der Oost. 2005. Engineering a selectable marker for hyperthermophiles. J. Biol. Chem. 280:11422-11431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannio, R., P. Contursi, M. Rossi, and S. Bartolucci. 2001. Thermoadaptation of a mesophilic hygromycin B phosphotransferase by directed evolution in hyperthermophilic Archaea: selection of a stable genetic marker for DNA transfer into Sulfolobus solfataricus. Extremophiles 5:153-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao, Z., C. W. Mueller, and D. A. Julin. 2010. Analysis of the recJ gene and protein from Deinococcus radiodurans. DNA Repair (Amst.) 9:66-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castán, P., L. Casares, J. Barbé, and J. Berenguer. 2003. Temperature-dependent hypermutational phenotype in recA mutants of Thermus thermophilus HB27. J. Bacteriol. 185:4901-4907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cava, F., A. Hidalgo, and J. Berenguer. 2009. Thermus thermophilus as biological model. Extremophiles 13:213-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper, S., and C. E. Helmstetter. 1968. Chromosome replication and the division cycle of Escherichia coli B/r. J. Mol. Biol. 31:519-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen, M. T. 1978. Multiplicity of genome equivalents in the radiation-resistant bacterium Micrococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 134:71-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto, Y., T. Yano, S. Kuramitsu, and H. Kagamiyama. 2001. Disruption of Thermus thermophilus genes by homologous recombination using a thermostable kanamycin-resistant marker. FEBS Lett. 506:231-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henne, A., H. Brüggemann, C. Raasch, A. Wiezer, T. Hartsch, H. Liesegang, A. Johann, T. Lienard, O. Gohl, R. Martinez-Arias, C. Jacobi, V. Starkuviene, S. Schlenczeck, S. Dencker, R. Huber, H. P. Klenk, W. Kramer, R. Merkl, G. Gottschalk, and H. J. Fritz. 2004. The genome sequence of the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:547-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hidaka, Y., M. Hasegawa, T. Nakahara, and T. Hoshino. 1994. The entire population of Thermus thermophilus cells is always competent at any growth phase. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 58:1338-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hishinuma, F., T. Tanaka, and K. Sakaguchi. 1978. Isolation of extrachromosomal deoxyribonucleic acids from extremely thermophilic bacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 104:193-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoseki, J., T. Yano, Y. Koyama, S. Kuramitsu, and H. Kagamiyama. 1999. Directed evolution of thermostable kanamycin-resistance gene: a convenient selection marker for Thermus thermophilus. J. Biochem. 126:951-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu, B., G. Yang, W. Zhao, Y. Zhang, and J. Zhao. 2007. MreB is important for cell shape but not for chromosome segregation of the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Mol. Microbiol. 63:1640-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itaya, M., K. Fujita, A. Kuroki, and K. Tsuge. 2008. Bottom-up genome assembly using the Bacillus subtilis genome vector. Nat. Methods 5:41-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itaya, M., K. Fujita, M. Ikeuchi, M. Koizumi, and K. Tsuge. 2003. Stable positional cloning of long continuous DNA in the Bacillus subtilis genome vector. J. Biochem. 134:513-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitten, T., and A. G. Barbour. 1992. The relapsing fever agent Borrelia hermsii has multiple copies of its chromosome and linear plasmids. Genetics 132:311-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komaki, K., and H. Ishikawa. 1999. Intracellular bacterial symbionts of aphids possess many genomic copies per bacterium. J. Mol. Evol. 48:717-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komaki, K., and H. Ishikawa. 2000. Genomic copy number of intracellular bacterial symbionts of aphids varies in response to developmental stage and morph of their host. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 30:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koyama, Y., T. Hoshino, N. Tomizuka, and K. Furukawa. 1986. Genetic transformation of the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus and of other Thermus spp. J. Bacteriol. 166:338-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.López-Sánchez, M. J., A. Neef, R. Patiño-Navarrete, L. Navarro, R. Jiménez, A. Latorre, and A. Moya. 2008. Blattabacteria, the endosymbionts of cockroaches, have small genome sizes and high genome copy numbers. Environ. Microbiol. 10:3417-3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann, N., and N. G. Carr. 1974. Control of macromolecular composition and cell division in the blue-green algae Anacystis nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 83:399-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michelsen, O., F. G. Hansen, B. Albrechtsen, and P. R. Jensen. 2010. The MG1363 and IL1403 laboratory strains of Lactococcus lactis and several dairy strains are diploid. J. Bacteriol. 192:1058-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minton, K. W. 1994. DNA repair in the extremely radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Mol. Microbiol. 13:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagpal, P., S. Jafri, M. A. Reddy, and H. K. Das. 1989. Multiple chromosomes of Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Bacteriol. 171:3133-3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura, A., Y. Takakura, H. Kobayashi, and T. Hoshino. 2005. In vivo directed evolution for thermostabilization of Escherichia coli hygromycin B phosphotransferase and the use of the gene as a selection marker in the host-vector system of Thermus thermophilus. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 100:158-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakane, S., N. Nakagawa, S. Kuramitsu, and R. Masui. 2009. Characterization of DNA polymerase X from Thermus thermophilus HB8 reveals the POLXc and PHP domains are both required for 3′-5′ exonuclease activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:2037-2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohtani, N., M. Tomita, and M. Itaya. 2008. Junction ribonuclease: a ribonuclease HII orthologue from Thermus thermophilus HB8 prefers the RNA-DNA junction to the RNA/DNA heteroduplex. Biochem. J. 412:517-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Omelchenko, M. V., Y. I. Wolf, E. K. Gaidamakova, V. Y. Matrosova, A. Vasilenko, M. Zhai, M. J. Daly, E. V. Koonin, and K. S. Makarova. 2005. Comparative genomics of Thermus thermophilus and Deinococcus radiodurans: divergent routes of adaptation to thermophily and radiation resistance. BMC Evol. Biol. 5:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oshima, T., and K. Imahori. 1971. Isolation of an extreme thermophile and thermostability of its transfer ribonucleic acid and ribosomes. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 17:513-517. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oshima, T., and K. Imahori. 1974. Description of Thermus thermophilus (Yoshida and Oshima) comb. nov., a nonsporulating thermophilic bacterium from a Japanese thermal spa. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 24:102-112. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robson, R. L., J. A. Chesshyre, C. Wheeler, R. Jones, P. R. Woodley, et al. 1984. Genome size and complexity in Azotobacter chroococcum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130:1603-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito, H., and K. Miura. 1963. Preparation of transforming deoxyribonucleic acid by phenol treatment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 72:619-629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider, D., E. Fuhrmann, I. Scholz, W. R. Hess, and P. L. Graumann. 2007. Fluorescence staining of live cyanobacterial cells suggest non-stringent chromosome segregation and absence of a connection between cytoplasmic and thylakoid membranes. BMC Cell Biol. 8:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slade, D., A. B. Lindner, G. Paul, and M. Radman. 2009. Recombination and replication in DNA repair of heavily irradiated Deinococcus radiodurans. Cell 136:1044-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spizizen, J. 1958. Transformation of biochemically deficient strains of Bacillus subtilis by deoxyribonuclease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 40:1072-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka, T., N. Kawano, and T. Oshima. 1981. Cloning of 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase gene of an extreme thermophile and partial purification of the gene product. J. Biochem. 89:677-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tobiason, D. M., and H. S. Seifert. 2006. The obligate human pathogen, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, is polyploid. PLoS Biol. 4:e185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webb, C. D., P. L. Graumann, J. A. Kahana, A. A. Teleman, P. A. Silver, and R. Losick. 1998. Use of time-lapse microscopy to visualize rapid movement of the replication origin region of the chromosome during the cell cycle in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 28:883-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu, L. J. 2004. Structure and segregation of the bacterial nucleoid. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14:126-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yokoyama, S., H. Hirota, T. Kigawa, T. Yabuki, M. Shirouzu, T. Terada, Y. Ito, Y. Matsuo, Y. Kuroda, Y. Nishimura, Y. Kyogoku, K. Miki, R. Masui, and S. Kuramitsu. 2000. Structural genomics projects in Japan. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:943-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zahradka, K., D. Slade, A. Bailone, S. Sommer, D. Averbeck, M. Petranovic, A. B. Lindner, and M. Radman. 2006. Reassembly of shattered chromosomes in Deinococcus radiodurans. Nature 443:569-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]