Abstract

Macrophage activation and infiltration into resident tissues is known to mediate local inflammation and is a hallmark feature of metabolic syndrome. Members of the sirtuin family of proteins regulate numerous physiological processes, including those involved in nutrient regulation and the promotion of longevity. However, the important role that SIRT1, the leading sirtuin family member, plays in immune response remains unclear. In this study, we demonstrate that SIRT1 modulates the acetylation status of the RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB and thus plays a pivotal role in regulating the inflammatory, immune, and apoptotic responses in mammals. Using a myeloid cell-specific SIRT1 knockout (Mac-SIRT1 KO) mouse model, we show that ablation of SIRT1 in macrophages renders NF-κB hyperacetylated, resulting in increased transcriptional activation of proinflammatory target genes. Consistent with increased proinflammatory gene expression, Mac-SIRT1 KO mice challenged with a high-fat diet display high levels of activated macrophages in liver and adipose tissue, predisposing the animals to development of systemic insulin resistance and metabolic derangement. In summary, we report that SIRT1, in macrophages, functions to inhibit NF-κB-mediated transcription, implying that myeloid cell-specific modulation of this sirtuin may be beneficial in the treatment of inflammation and its associated diseases.

Chronic inflammation is increasingly recognized as a causal factor leading to the development of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes (15, 31). This low-grade inflammatory state is in part mediated by macrophages, key sentinels of the innate immune system. Macrophages quiescently monitor the tissue milieu for signs of infection or damage (13, 25). Upon stimulation, macrophages infiltrate resident tissue, perpetuating local inflammation and contributing to the development of insulin resistance and metabolic derangements (17, 37, 43). The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) transcription factor signaling pathway is a key mediator of immune response in macrophages (5, 7). NF-κB is composed of a heterodimer of p50 and RelA/p65 subunits. In unstimulated cells, NF-κB resides in the cytoplasm bound to its inhibitory proteins, which are members of the inhibitor of κB (IκB) family. Stimulation of cells by environmental factors, including dietary fatty acids, liberates NF-κB, allowing it to translocate to the nucleus, where it mediates gene transcription (12). Under environmental stresses, such as those surrounding obesity-like conditions, this chain of events is believed to ultimately lead to insulin resistance, setting in motion the vicious cycle of the metabolic syndrome.

Sirtuins are highly conserved NAD+-dependent deacetylases that target histones, transcription factors, coregulators, and other key regulators to adapt gene expression and metabolism to the cellular energy state (16, 22, 32). SIRT1, the leading family member, has been reported to promote longevity in species ranging from yeast to flies (1-3, 6). It is believed that these life-extending actions of SIRT1 result from its ability to regulate stress management and energy homeostasis. SIRT1 belongs to the class III family of histone deacetylases (HDACs), which use NAD+ as a cosubstrate for the deacetylation of proteins (11). Previous reports have demonstrated that artificial overexpression of SIRT1 leads to suppression of the inflammatory response, whereas deletion of the protein in hepatocytes results in increased local inflammation (26, 27). It appears that in immune signaling, SIRT1's inhibitory actions work through at least two mechanistically distinct pathways. On one hand, sirtuins may diminish histone acetylation by inactivating histone acetyltransferase (HAT) enzymatic activity. In support of this notion, SIRT1 directly interacts with p300, the CREB-binding protein (CBP), and other HATs to inhibit the acetylation status of these enzymes (9, 23). Alternatively, SIRT1 has recently been reported to deacetylate the RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB at lysine 310 in vitro using overexpression systems (41). Deacetylation of K310 of RelA/p65 leads to decreases in NF-κB transcription activity, reducing production of proinflammatory cytokines and antiapoptotic genes (41). In addition, it has been shown that moderate overexpression of SIRT1 in mice leads to downregulated NF-κB activity (26). However, despite mounting evidence pointing toward the anti-inflammatory potential of SIRT1, it is still unclear how this leading sirtuin family member functions in immune cells or systemically.

In order to directly investigate the role of SIRT1 in immune signaling, we generated a myeloid cell-specific SIRT1 knockout (KO) mouse (Mac-SIRT1 KO). Here, we provide both in vitro and in vivo evidence that SIRT1 deacetylates the nuclear RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB and attenuates NF-κB-mediated gene transcription. Genetic deletion of SIRT1 in myeloid cells not only leads to hyperactive NF-κB signaling, but also predisposes mice to the development of insulin resistance and metabolic disorders. Together, our findings demonstrate that myeloid SIRT1 directly regulates the immune response and suggest that activators of SIRT1 may play an important therapeutic role in the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal experiments.

The SIRT1 allele with floxed exon 4 (8a) was backcrossed 6 times into the C57BL/6 background and then bred with mice expressing Cre recombinase driven by the lysozyme promoter (Jackson Laboratory) to generate myeloid cell-specific SIRT1 knockout (Mac-SIRT1 KO) mice on a >98% C57BL/6 background. Mac-SIRT1 KO mice and their age-matched littermate Lox controls (lysozyme-Cre+/+ SIRT1flox/flox) older than 6 weeks of age were fed ad libitum either a standard laboratory chow diet or a high-fat Western diet (HFD) (D12079B; Research Diets) for 14 weeks. Oral glucose tolerance tests (1 g/kg of body weight) were performed after a 14-h fast. For insulin tolerance tests, mice were challenged with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of human insulin (0.65 U/kg) after a 4-h fast. For biochemical analysis of insulin signaling, livers and quadriceps from Mac-SIRT1 KO and control mice were isolated and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue homogenates were immunoblotted for total Akt and phospho-Akt (Ser473) (Cell Signaling). Serum levels of lipids (total cholesterol and triglycerides), cytokines (tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], interleukin 6 [IL-6], and IL-1β), adipokines (leptin), and insulin in fasted mice were quantified using commercially available kits. For liver triglyceride quantification, samples were finely minced and extracted overnight in chloroform and methanol (2/1 ratio) at 4°C. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the NIEHS, NIH, Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell culture.

For bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), control and Mac-SIRT1 KO bone marrow was isolated from femurs and tibias and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 20% L929 conditioned medium. To assess cytokine production, cells were pretreated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for the time indicated in the figure legends. Secreted cytokines were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer's protocols (eBioscience, San Diego, CA).

Transfections and luciferase assay.

For transactivation experiments, BMDMs were harvested after day 5 of culture in L929-conditioned medium and then resuspended in Amaxa electroporation buffer (Mouse Macrophage Nucleofector Kit; Amaxa) to a concentration of 2 × 106 cells per transfection. The cells were transfected with the indicated firefly luciferase reporter and control pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase; Promega). For NF-κB knockdown, a total of 24 μl of a 5-nmol solution of anti-NF-κB small interfering RNA (siRNA) (Santa Cruz) or Scramble siRNA (Santa Cruz) was mixed with 0.1 ml of cell suspension, transferred to a 2.0-mm electroporation cuvette, and nucleofected with an Amaxa Nucleofector apparatus. After electroporation, the cells were transferred to conditioned medium and cultured in 6-well plates at 37°C. Forty-eight hours postelectroporation, TNF-α (10 ng/ml) was added to the cells, which were lysed 6 h later. The final firefly luciferase activity was normalized to the coexpressed Renilla luciferase activity.

Western blot analysis and ChIP analysis.

Tissue homogenates were prepared with NP-40 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) containing Complete protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche) and then immunoblotted using antibodies against phosphorylated JNK (P-JNK), JNK, P-p38, p38, P-ERK, ERK, P-Akt, and AKT (Cell Signaling Technology Inc.). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis was performed as described by Upstate Biotechnology with antibodies against NF-κB, SIRT6, acetyl (Ac)-H3K9, H3 (Santa Cruz Biotech and Chemicon, Affinity BioReagents, and BD Biosciences) or normal rabbit IgG. DNA fragments were subjected to quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using primers flanking NF-κB response elements on various targets.

In vivo exposure to LPS.

Mice were placed in a Plexiglas chamber and exposed to an aerosolized solution containing Escherichia coli O111:B4 lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (300 μg/ml) in saline (0.9% sodium chloride) for 30 min as previously described (33). At 2 h postexposure, the animals were euthanized with a one-time intraperitoneal injection of Fatal-Plus solution (6.25 mg). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed immediately following euthanasia, and total white blood cells (WBCs) were enumerated and analyzed as described previously (24). TNF-α, ΙL-1B, and IL-6 levels were measured using relevant ELISA kits purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). For systemic LPS injection experiments, mice were given a single dose of LPS (1 mg/kg). Forty minutes after an intraperitoneal injection of LPS, mice (n = 9 for each genotype) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and then transcardially perfused with ice-cold PBS. The livers were quickly removed and frozen on dry ice. The frozen livers were homogenized in 100 mg tissue/ml cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 0.25 M sucrose, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor cocktail tablets). Samples were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The supernatant was collected for protein assay using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent kit (Pierce, Milwaukee, WI). The levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in livers and sera were measured with commercial ELISA kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) as described previously (28).

RNA analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from cells or tissues using Trizol (Invitrogen) and a Qiagen RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). For qPCR, cDNA was synthesized with the ABI reverse transcriptase kit and analyzed using SYBR green Supermix (Applied Biosystems). All data were normalized to lamin A expression.

Statistical analysis.

Values are expressed as means ± standard errors of the mean (SEM). Significant differences between means were analyzed by a two-tailed, unpaired Student's t test, and differences were considered significant at a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Loss of SIRT1 leads to hyperacetylation of NF-κB.

To better understand the role of SIRT1 in immune cell biology, we generated a myeloid cell-specific SIRT1 KO mouse (Mac-SIRT1 KO). Mice expressing a conditional SIRT1 floxed allele were bred into a C57/BL6 background and then crossed with mice expressing Cre recombinase under a myeloid cell-specific promoter. The cross yielded a highly efficient excision of SIRT1 in BMDMs while retaining normal systemic SIRT1 expression levels (Fig. 1A). BMDMs from Mac-SIRT1 KO mice displayed the appearance of a nonfunctional truncated protein, resulting from the excision of 51 amino acids of the SIRT1 catalytic domain.

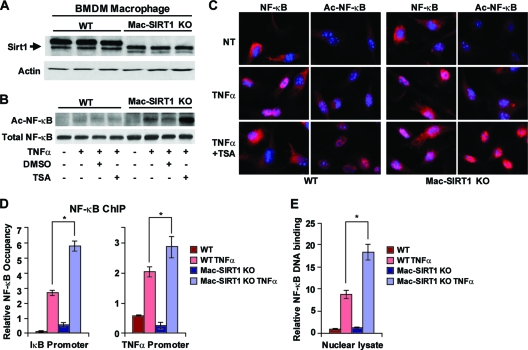

FIG. 1.

Myeloid cell-specific deletion of SIRT1 leads to hyperactive NF-κB signaling. (A) Western blot (WB) analysis of SIRT1 protein in BMDMs from Mac-SIRT1 KO mice compared to those from control mice. WT, wild type. (B) Elevated levels of acetylated p65 in Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMs after TNF-α treatment. BMDMs from control and Mac-SIRT1 KO mice were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of TSA (100 nM). Levels of acetylated p65 were analyzed by Western blotting. (C) Ablation of SIRT1 results in higher levels of Ac-p65 in the nucleus following TNF-α and TSA treatment. Total p65/RelA and Ac-p65/RelA were stained (red) by indirect immunofluorescence, and the nuclei were stained (blue) with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). NT, nontreated. (D) SIRT1 deficiency increases the association of p65/RelA with κB sites at the promoters of NF-κB target genes. BMDMs were treated with vehicle or TNF-α for 30 min and assayed using anti-p65/RelA antibodies. NF-κB occupancy (percentage of input) at κB sites of IκB and TNF-α promoters were analyzed by qPCR. (E) SIRT1 deficiency increases activated NF-κB. The data are represented as means ± SEM; n = 3; *, P < 0.05.

HDACs regulate the transcriptional activity of NF-κB through direct modification of its RelA/p65 subunit. Previous studies have demonstrated that HDACs deacetylate the RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB at three distinct lysine residues, namely, K218, K221, and K310 (7, 19, 41). Deacetylation of these sites leads to enhanced transcriptional activation of NF-κB. In order to identify SIRT1's role in the activation of NF-κB, we conducted transcriptional activation assays using reporter constructs specific for all three putative activation sites and a triple (K218, K221, and K310) reporter construct. In line with results reported by Yeung et al. (41), we determined that the K310 motif is the major NF-κB-mediated transcriptional target of SIRT1 (data not shown). Furthermore, the K310 motif is the most studied acetylation site of p65 and has the benefit of commercially available antibodies. The acetylation of K310 is also required for NF-κB's full transcriptional potential and is important for modulating NF-κB-dependent inflammatory responses (8). Therefore, we concluded that K310 was the most relevant residue for the study of SIRT1-mediated regulation of NF-κB.

To determine whether loss of SIRT1 activity in macrophages alters the acetylation status of NF-κB, BMDMs from control and Mac-SIRT1 KO mice were stimulated with TNF-α and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Ac-K310 specific antibodies. BMDMs from both control and Mac-SIRT1 KO mice displayed very low basal levels of Ac-RelA/p65 (Fig. 1B). TNF-α treatment induced acetylation of RelA/p65 in both control and SIRT1 KO BMDMs; however, SIRT1 KO BMDMs displayed significantly higher levels of Ac-RelA/p65. Further treatment with Trichostatin A (TSA), a specific inhibitor of the class I and II HDACs, dramatically induced hyperacetylation of RelA/p65 in SIRT1 KO BMDMs. Immunostaining of BMDMs showed elevated nuclear Ac-RelA/p65 in SIRT1 KO cells following TNF-α and TSA treatment, confirming that SIRT1 enzymatic activity regulates acetylation of NF-κB (Fig. 1C). Collectively, these data indicate that SIRT1 deacetylates RelA/p65 K310 in macrophages, while deletion of SIRT1 leads to hyperacetylation of the transcription factor.

The increased acetylation status of NF-κB in SIRT1 KO macrophages was suggestive of higher NF-κB-mediated gene transcription. To test this possibility, Mac-SIRT1 KO and control BMDMs were stimulated with TNF-α, and chromatin-associated fractions of NF-κB were analyzed by ChIP using anti-RelA/p65 antibodies. In response to TNF-α, NF-κB levels were moderately enriched at the promoters of several target genes, including IκB and TNF-α genes, in Mac-SIRT1 KO cells compared to controls (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, significantly higher levels of DNA-bound NF-κB were found in Mac-SIRT1 KO nuclear lysates than in controls following TNF-α stimulation using an NF-κB activation assay (Sigma) (Fig. 1E).

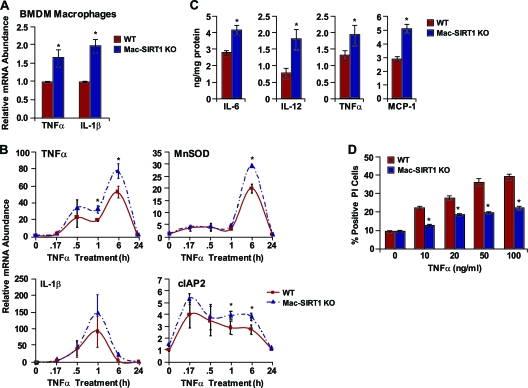

Loss of SIRT1 in macrophages promotes NF-κB-dependent cytokine release.

The NF-κB transcription factor plays a pivotal role in the regulation of inflammatory, immune, and antiapoptotic responses in mammals (14). Upon activation, NF-κB orchestrates the transcription of numerous proinflammatory cytokines. The increased association of NF-κB with target promoters in SIRT1-deficient macrophages indicated that SIRT1 levels may influence NF-κB-dependent gene transcription. To test this possibility, we analyzed NF-κB target genes by quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. Basal expression levels of TNF-α and IL-1β, two major proinflammatory cytokines, were upregulated in Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMs compared to controls, suggesting chronic NF-κB activation (Fig. 2A). A time course with TNF-α stimulation led to varied, though consistently higher, expression of the NF-κB target manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), cellular inhibitor of apoptosis 2 (cIAP2), IL-1β, and TNF-α genes in Mac-SIRT1 KO cells compared to controls (Fig. 2B). Additionally, protein levels of the cytokines monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α were measurably higher in Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMs following 12 h of TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 2C). In aggregate, these data indicate that ablation of SIRT1 in macrophages leads to increased NF-κB-dependent proinflammatory cytokine production.

FIG. 2.

Loss of SIRT1 in macrophages promotes NF-κB-dependent cytokine release and inhibits NF-κB-mediated apoptosis. (A) Elevated proinflammatory cytokine message levels in Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMs. (B) Increased mRNA expression of NF-κB target genes in Mac-SIRT1 KO cells following TNF-α (10 ng/ml) treatment at the indicated time points. (C) Increased release of proinflammatory cytokines from Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMs measured by ELISA following 12-h TNF-α treatment. (D) SIRT1 deficiency protects BMDMs from TNF-α-induced apoptosis. BMDMS from control and Mac-SIRT1 KO mice were treated with TNF-α and stained with propidium iodide. The data are represented as means ± SEM; n = 3; *, P < 0.05.

In addition to mediating proinflammatory cytokine gene expression, NF-κB plays an antiapoptotic role, providing cells protection from environmental stresses (21). This notion is evidenced by the upregulation of the antiapoptotic cIAP2 gene in Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMs (Fig. 2B). To further evaluate this arm of the NF-κB signaling pathway, BMDMs were treated with increasing doses of TNF-α for 6 h, and cell survival was measured by propidium iodide staining. In support of our hypothesis, Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMs displayed significantly lower levels of cell death (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that hyperactive NF-κB in SIRT1-deficient macrophages leads to apoptosis resistance upon TNF-α treatment.

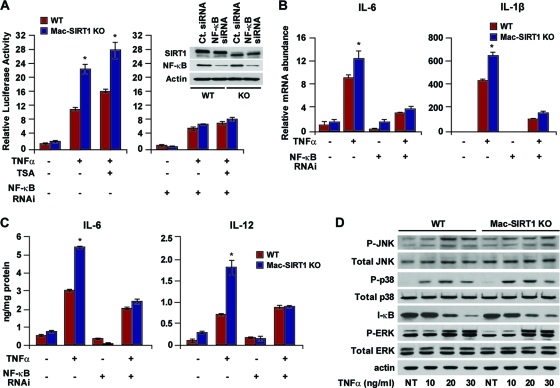

SIRT1 deficiency induces proinflammatory cytokine production through hyperactivation of NF-κB.

Our observations that SIRT1 deficiency in macrophages results in hyperacetylated NF-κB and elevated proinflammatory cytokine levels suggested that SIRT1 is one of the primary HDACs regulating NF-κB-dependent gene transcription. In order to confirm this hypothesis, we examined transcriptional expression using an NF-κB-luciferase reporter construct in BMDMs. TNF-α-stimulated Mac-SIRT1 KO cells displayed significantly higher reporter activity than controls (Fig. 3 A, left). To confirm that the increased reporter activity in the SIRT1 KO macrophages was due to increased NF-κB signaling, siRNA to NF-κB was transfected into BMDMs (Fig. 3A, inset). As expected, both Mac-SIRT1 KO and control cells exhibited very little difference in NF-κB-luciferase reporter activity in NF-κB-depleted cells (Fig. 3A, right). These results were further confirmed by assessment of message levels of the NF-κB target IL-6 and IL-1β genes (Fig. 3B). Similarly, the production levels of proinflammatory cytokine proteins were comparable in control and SIRT1 KO macrophages after depletion of NF-κB (Fig. 3C), indicating that the elevated levels of cytokines in SIRT1-deficient macrophages were primarily the result of hyperactive NF-κB. To further verify that loss of SIRT1 induces inflammation primarily through the NF-κB signaling pathway, markers for activated mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases were examined in control and SIRT1 KO macrophages. No distinguishable differences in protein levels were observed between cell types before and after TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 3D). Together, these results suggest that loss of SIRT1 in macrophages leads to hyperactivation of the NF-κB transcription factor, resulting in increased transcription of proinflammatory genes.

FIG. 3.

Loss of SIRT1 induces elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines through NF-κB. (A) Loss of SIRT1 induces NF-κB-dependent transactivation. (Left) BMDMs were cotransfected with 3× κB luciferase reporter, followed by treatment with TNF-α (10 ng/ml). (Right) NF-κB siRNA was cotransfected together with reporter plasmids. (Inset) Western blot demonstrating NF-κB knockdown in primary macrophages. RNAi, RNA interference. (B) Loss of SIRT results in elevated message levels of proinflammatory cytokines through NF-κB. (C) Cytokine protein levels are essentially equal in WT and Mac-SIRT1 KO cells following knockdown of NF-κB. (D) SIRT1 does not appear to regulate the MAP kinase signaling pathway. Shown is a representative Western blot of BMDMs from control and Mac-SIRT1 KO mice following TNF-α treatment, as indicated. The dsata are represented as means ± SEM; n = 3; *, P < 0.05.

Mac-SIRT1 KO mice are hypersensitive to local and systemic LPS challenges.

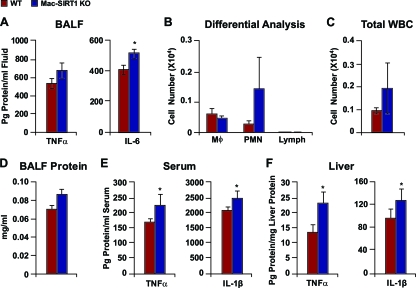

The elevated NF-κB activity in SIRT1-deficient macrophages suggested that Mac-SIRT1 KO mice may be hypersensitive to immune challenges. Lung tissue is macrophage rich, and LPS aerosolization exposure is a well-established model for quantifying an organ-localized inflammatory response to environmental challenge. Therefore, to further address the mechanisms by which SIRT1 modulates activation of NF-κB, we exposed control and Mac-SIRT1 KO mice to an aerosolized solution containing LPS and then assayed BAL fluid (BALF) for cytokine expression. As shown in Fig. 4 A, aerosol exposure to LPS induced significantly higher levels of IL-6 and a trend toward higher TNF-α levels in the lungs of Mac-SIRT1 KO mice. Cytokine expression by resident lung cells, in particular, alveolar macrophages, plays a key role in the induction of migration of neutrophils (polymorphonuclear neutrophils [PMN]), a pivotal effector cell in both lung infection and inflammation, into the lung airspace (33). In line with increased cytokine levels in the BALF, Mac-SIRT1 KO mice displayed trends toward higher white blood cell counts, in particular, PMN (Fig. 4B to D), in response to aerosolized LPS than littermate controls.

FIG. 4.

SIRT1 deficiency augments proinflammatory cytokine levels in vivo. Mice were exposed to aerosolized LPS and sacrificed 2 h later. (A) BALF was collected and analyzed for TNF-α and IL-6 levels (n = 5 or 6). (B) Differential analysis of blood cells in BALF following aerosolized LPS exposure, as described in Materials and Methods (n = 6 per cohort). The data are represented as means ± SEM. (C) Total WBC counts from control and Mac-SIRT1 KO mice following aerosol LPS treatment, as described in Materials and Methods (n = 6 per cohort). The data are represented as means ± SEM. (D) BALF protein levels in control and Mac-SIRT1 KO mice following aerosol LPS treatment, as described in Materials and Methods (n = 6 per cohort). The data are represented as means ± SEM. (E) Elevated serum cytokine protein levels in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice (n = 9) given LPS injections (1 mg/kg). (F) Elevated liver tissue cytokine protein levels in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice (n = 9) given LPS injection (1 mg/kg). The data are represented as means ± SEM; *, P < 0.05.

To further examine the proinflammatory phenotype of Mac-SIRT1 KO mice, animals were given a single dose of LPS (1 mg/kg) for 40 min, and serum and liver tissue samples were analyzed for proinflammatory cytokines. Similar to pulmonary exposure experiments, Mac-SIRT1 mice displayed higher levels of TNF-α and IL-1β than controls in both serum (Fig. 4E) and liver tissue (Fig. 4F) following exposure. These data suggest that Mac-SIRT1-deficient mice exhibit an intrinsic proinflammatory phenotype that is independent of the metabolic conditions associated with obesity.

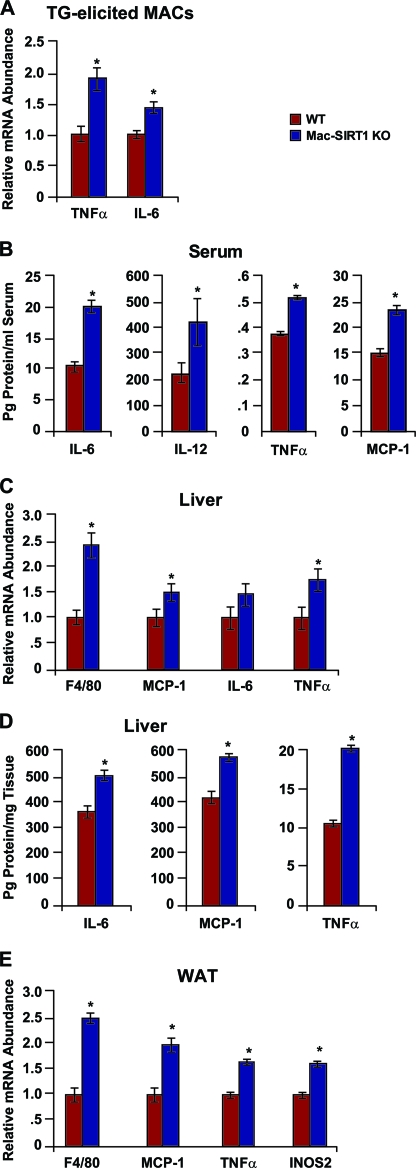

Hyperactivation of NF-κB is associated with chronic inflammation under obesity-like conditions (44). Several recent reports have indicated that specific dietary fatty acids can directly activate Toll-like receptors, which are key recognition components of the innate immune system (30, 38). Stimulation of these receptors triggers a signaling cascade culminating in activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways. The elevated activity of NF-κB in SIRT1 KO macrophages suggests that Mac-SIRT1 KO mice may also display increased susceptibility to environmental stimuli associated with obesity. To test this possibility, Mac-SIRT1 KO and control mice were fed ad libitum a Western diet providing 40% of Kcal as fat and 0.21% as cholesterol for 14 weeks. In line with our hypothesis, thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages from Mac-SIRT1 KO mice displayed higher message levels of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 than controls (Fig. 5 A). More importantly, serum protein levels of the cytokines IL-6, IL-12, TNF-α, and MCP-1 were significantly higher in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice, suggesting a chronic inflammatory state (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, significantly higher levels of F4/80, a classic marker of macrophage infiltration, were expressed in the livers of Mac-SIRT1 KO mice than in those of controls (Fig. 5C). Message levels of TNF-α and IL-1β (Fig. 5C), as well as protein cytokine levels, were also increased in liver tissue of Mac-SIRT1 KO mice (Fig. 5D), pointing toward the development of hepatic inflammation. Interestingly, F4/80 expression was higher in white adipose tissue (WAT) in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice (Fig. 5E). This pattern is indicative of elevated adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs), which are thought to perpetuate local inflammation and cause insulin resistance (37, 39, 42). Additionally, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS2), an enzyme involved in the oxidative respiratory burst of macrophages, was upregulated in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice (Fig. 5E). Collectively, these results highlight SIRT1's protective role in high-fat-induced inflammation.

FIG. 5.

Mac-SIRT1-deficient mice display enhanced proinflammatory cytokine levels on a high-fat diet. (A) Elevated message levels of proinflammatory cytokines in Mac-SIRT1 KO thioglycolate (TG)-elicited macrophages after high-fat feeding. (B) Elevated serum cytokine protein levels in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice after high-fat feeding. (C and D) Markers of macrophage infiltration and inflammation message levels (C) and protein levels (D) in liver. (E) Elevated proinflammatory cytokine mRNA levels and macrophage infiltration markers in white adipose tissue of Mac-SIRT1 KO mice. The mice were fed a high-fat diet for 14 weeks. The data are represented as means ± SEM; n = 5 or 6; *, P < 0.05.

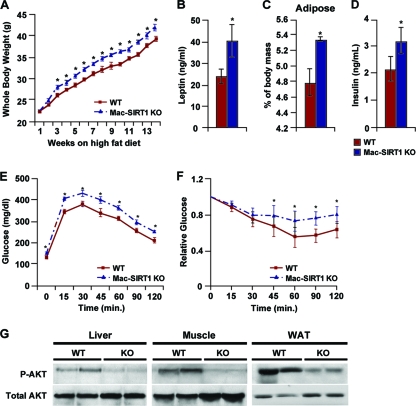

Myeloid deficiency of SIRT1 exacerbates insulin resistance and impairs glucose tolerance.

Chronic inflammation is thought to underlie obesity-induced insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (15, 31). Therefore, we investigated whether Mac-SIRT1 KO mice were at increased risk of developing metabolic disease. Although Mac-SIRT1 KO mice displayed no body weight abnormalities on a chow diet (data not shown), they did gain significantly more weight on a Western diet than control mice (Fig. 6 A) without variation in food intake (data not shown). Consistent with an increase in body weight, serum leptin levels and epididymal fat pads from Mac-SIRT1 KO mice exceeded those of controls (Fig. 6B and C). These results suggest that deletion of SIRT1 in macrophages exacerbates the onset of diet-induced obesity. It is likely that the excess weight gain by Mac-SIRT1 KO mice on a Western diet was due to chronic activation and infiltration of macrophages into key metabolic organs, such as WAT and the liver, resulting in dysfunction in metabolic signaling programs.

FIG. 6.

Myeloid cell-specific deletion of SIRT1 impairs systemic metabolic homeostasis on a high-fat diet. (A) Mac-SIRT1 KO mice gain more weight on a Western-style high-fat diet (n = 14 per cohort). (B) Increased leptin levels in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice following high-fat diet feeding. (C) Increased white adipose tissue in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice upon high-fat diet feeding. (D) Increased resting insulin levels in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice following a high-fat diet. (E) Oral glucose tolerance tests (1 g/kg) were carried out after 14 weeks of high-fat diet in male Mac-SIRT1 KO and control mice (n = 14 per cohort). (F) Impairment in insulin action in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice measured by insulin tolerance tests. (G) Impaired insulin signaling in tissues of Mac-SIRT1 KO mice. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted for phospho-Akt (P-Akt) or total Akt in liver, quadriceps muscle, and white adipose tissue. The data are represented as means ± SEM; *, P < 0.05, unless noted.

To further explore the role of SIRT1 in obesity-induced insulin resistance, glucose and insulin tolerance tests were performed in control and Mac-SIRT1 KO mice (Fig. 6E and F). The results revealed that Mac-SIRT1 KO mice were slightly but significantly more glucose intolerant following a 14-week high-fat diet challenge (Fig. 6E). Additionally, Mac-SIRT1 KO mice were more resistant than controls to the glucose-lowering effects of exogenous insulin (Fig. 6F). Consistent with a decrease in insulin sensitivity, fasting insulin levels were significantly higher in the Mac-SIRT1 KO mice (Fig. 6D). However, serum triglyceride levels, cholesterol levels, and bone density (data not shown) were similar between mouse models. To further explore the origin of insulin resistance, phosphorylation levels of AKT, a marker for the onset of global insulin resistance, were analyzed in liver, muscle, and WAT tissues (Fig. 6G). As expected, Mac-SIRT1 KO mice displayed lower levels of AKT phosphorylation, suggestive of chronic insulin resistance. In summary, these data signify that macrophage-specific loss of SIRT1 magnifies systemic insulin resistance and hinders glucose tolerance.

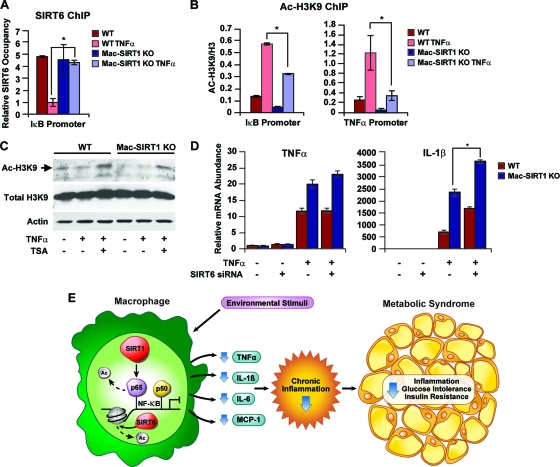

SIRT1 deficiency in macrophages induces a compensatory increase of SIRT6 histone H3K9 deacetylase activity.

Histone deacetylation decreases accessibility of chromatin to DNA binding factors. This notion was highlighted in a recent report demonstrating that the SIRT1 homolog SIRT6 associates with NF-κB target gene promoters and attenuates gene transcription through deacetylase of histone H3K9 (18). To determine whether SIRT6 deacetylase activity may have compensatory effects on NF-κB transcription in the absence of SIRT1, ChIP analysis was performed on NF-κB target gene promoters using anti-SIRT6 antibodies. SIRT6 promoter occupancy was dramatically reduced in BMDM control cells following TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 7 A). However, in Mac-SIRT1 KO cells, SIRT6 levels remained consistent even after TNF-α treatment. Additionally, Ac-H3K9 levels near NF-κB binding sites within promoters of IκB and TNF-α were significantly higher in control cells than in SIRT1-deficient cells following TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 7B). This evidence indicates that the chromatin-remodeling actions of SIRT6 may in part compensate for SIRT1-mediated NF-κB gene transcription. Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates also showed decreased Ac-H3K9 levels in the Mac-SIRT1 KO cells, even after treatment with TSA, suggesting compensation from chromatin-associated SIRT6 (Fig. 7C).

FIG. 7.

Compensatory effects of SIRT6 on NF-κB activation in Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMs. (A) Increased association of SIRT6 on the κB site of NF-κB target genes in Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMs upon TNF-α treatment. Cell extracts from control and Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMS were ChIPed using anti-SIRT6 antibodies. SIRT6 occupancy (percentage of input) at the κB site of IκB was analyzed by qPCR. (B) Decreased acetylation levels of H3K9 on the κB site of NF-κB target genes in BMDMs. ChIP assays were performed with anti-Ac-H3K9 antibodies following 1 h of TNF-α treatment. (C) Decreased total levels of Ac-H3K9 in SIRT1 KO BMDMS after TNF-α treatment (10 ng/ml). (D) Knockdown of SIRT6 enhances proinflammatory cytokine levels in SIRT1-deficient macrophages following TNF-α treatment. Control and Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMS were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA specific to SIRT6, followed by TNF-α treatment. (E) Proposed model showing the role of SIRT1 in NF-κB-mediated signaling in the macrophage. Environmental stimuli activating NF-κB transcriptional activity trigger the immune response. SIRT1 suppresses NF-κB-mediated transcription by deacetylating the p65/RelA subunit of NF-κB, resulting in lower levels of inflammation and reduced likelihood of developing metabolic syndrome. The data are represented as means ± SEM; n = 3; *, P < 0.05.

To further explore the compensatory effects of SIRT6, BMDMs were transfected with siRNA to SIRT6, followed by treatment with TNF-α. Message levels of the NF-κB target IL-1β gene were slightly higher in cells depleted of both sirtuins, while TNF-α levels showed little change (Fig. 7D). In aggregate, these results suggest that SIRT6 deacetylase activity is upregulated in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice, pointing to a compensatory role of SIRT6 in the absence of SIRT1.

DISCUSSION

Since the discovery of sirtuins as longevity determination genes in yeast over a decade ago, much effort has been devoted to elucidating the molecular mechanisms and physiological functions of their mammalian homologs. Recently, evidence has emerged pointing toward an association between SIRT1 and the NF-κB transcription factor, which makes targeting this signaling pathway an intriguing possibility for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases (29, 40, 41). In our current study, we used a Mac-SIRT1 KO mouse model to explore SIRT1's role in the regulation of the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response. We demonstrated that SIRT1 plays an important role in controlling cytokine production in the wake of environmental stimuli, such as TNF-α, bacterial endotoxin, and dietary lipids. Importantly, our study used a novel mouse model to further verify that SIRT1 regulates this in vivo anti-inflammatory effect by modulating NF-κB gene transcription in immune cells, namely, macrophages.

Our findings suggest that SIRT1 plays a protective role against chronic inflammation and thus development of metabolic syndrome, an observation supported by several independent lines of evidence. First, Mac-SIRT1 KO BMDMs display elevated levels of hyperacetylated nuclear NF-κB. Second, hyperactive NF-κB signaling in macrophages contributed to elevated transcriptional activity and proinflammatory cytokine production. Third, knockdown of NF-κB in Mac-SIRT1 KO and control macrophages results in similar cytokine production in the cell groups, demonstrating that SIRT1 functions primarily through NF-κB. Fourth, loss of SIRT1 leads to compensatory SIRT6 deacetylase activity on histone H3 lysine 9. Finally, the chronic inflammatory phenotype observed in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice is independent of metabolic conditions. However, HFD-induced obesity exacerbates metabolic abnormalities in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice and leads to systemic abrogated insulin signaling.

It is widely reported that NF-κB is subject to regulation by acetylation and to deacetylation by HDACs, including SIRT1 (8, 29, 40, 41). We note that the promiscuous nature of SIRT1 deacetylase activity at both histone and nonhistone substrates most likely reflects a transient enzyme-substrate interaction. In this context, it appears SIRT1 association at NF-κB target gene promoter sites is an important regulatory mechanism involved in the modulation of this transcription factor. In support of these notions, TSA treatment abrogates deacetylation of NF-κB in Mac-SIRT1 KO macrophages, further highlighting the dynamic nature of this process (Fig. 1B and C). Unlike SIRT1, SIRT6 exerts deacetylase activity on histone H3K9 (Fig. 7A and B), demonstrating that SIRT1 and SIRT6 act upon NF-κB via distinct molecular mechanisms. These findings imply that the combinatory actions of both sirtuins modulate NF-κB transcriptional activity and thus regulate the immune signaling pathway (Fig. 7E).

Additional experiments with both primary macrophages and Mac-SIRT1 KO mice revealed that the proinflammatory phenotype associated with myeloid deletion of SIRT1 was independent of metabolic conditions. For example, Mac-SIRT1-deficient mice displayed hyperactive immune signaling in response to both aerosol and systemic LPS injections on a standard diet, where no metabolic defects were observed (Fig. 4A to C). These same chow-fed mice showed no signs of obesity or metabolic derangements, while displaying a heightened state of inflammatory response. Additionally, primary bone marrow-derived macrophages from Mac-SIRT1 KO mice expressed higher basal levels of proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 2A). These findings indicate that SIRT1 deficiency induces an intrinsic proinflammatory status in macrophages. Additional data from our group (not shown) indicate that SIRT1-deficient macrophages display disruptions in fatty acid oxidative metabolism. It is likely that the intrinsic chronic inflammation in Mac-SIRT1 KO mice primes diet-induced obesity, elevated resting leptin levels, and insulin resistance (Fig. 6A to G). Consistent with this notion, excess proinflammatory cytokines have been shown to trigger insulin resistance in animals (9, 33). This chronic activation may be the cause of insulin resistance. Since NF-κB is a transcription factor involved in a vast array of disease states, understanding its interactions with sirtuins may provide therapeutic benefits.

Excess proinflammatory cytokines have been shown to trigger insulin resistance in animals (10, 34). In vitro cell culture studies have shown that TNF-α can render cells insulin resistant through downregulation of the synthesis of the glucose transporter, as well as through interference with insulin signaling (34). Studies have also shown that mice lacking the TNF-α receptor have improved capacity to facilitate glucose uptake in metabolic tissues (35, 36). Interestingly, it has been shown that caloric restriction attenuates the age-related upregulation of nuclear factor NF-κB, which is known to induce transcription of TNF-α in adipose tissue and the production of inflammatory cytokines in immune cells (20, 41). It is possible that upregulation of SIRT1 may contribute to increases in insulin sensitivity and reduction in inflammation.

In summary, we have demonstrated an important role for SIRT1 in immune signaling. In the absence of SIRT1, macrophages display hyperactive NF-κB, leading to increased transcription of proinflammatory genes. Our findings identify SIRT1 as an important link between environmental stress and immune system activation. It will be interesting to investigate how pharmacological activators of sirtuins affect diseases associated with chronic inflammation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Adelman and John Cidlowski for critical reading of the manuscript and Frederic Alt at Harvard Medical School for providing the SIRT1 exon 4 floxed allele.

This research was supported by a grant from the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, to X.L. (Z01 ES102205).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anastasiou, D., and W. Krek. 2006. SIRT1: linking adaptive cellular responses to aging-associated changes in organismal physiology. Physiology (Bethesda) 21:404-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, R. M., K. J. Bitterman, J. G. Wood, O. Medvedik, and D. A. Sinclair. 2003. Nicotinamide and PNC1 govern lifespan extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 423:181-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bäckesjä, C. M., Y. Li, U. Lindgren, and L. A. Haldosen. 2006. Activation of Sirt1 decreases adipocyte formation during osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21:993-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reference deleted.

- 5.Caamaño, J., and C. A. Hunter. 2002. NF-kappaB family of transcription factors: central regulators of innate and adaptive immune functions. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:414-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, D., and L. Guarente. 2007. SIR2: a potential target for calorie restriction mimetics. Trends Mol. Med. 13:64-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, L., W. Fischle, E. Verdin, and W. C. Greene. 2001. Duration of nuclear NF-kappaB action regulated by reversible acetylation. Science 293:1653-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, L. F., Y. Mu, and W. C. Greene. 2002. Acetylation of RelA at discrete sites regulates distinct nuclear functions of NF-kappaB. EMBO J. 21:6539-6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Cheng, H. L., R. Mostoslavsky, S. Saito, J. P. Manis, Y. Gu, P. Patel, R. Bronson, E. Appella, F. W. Alt, and K. F. Chua. 2003. Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:10794-10799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen, H. Y., C. Miller, K. J. Bitterman, N. R. Wall, B. Hekking, B. Kessler, K. T. Howitz, M. Gorospe, R. de Cabo, and D. A. Sinclair. 2004. Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science 305:390-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinstein, R., H. Kanety, M. Z. Papa, B. Lunenfeld, and A. Karasik. 1993. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha suppresses insulin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor and its substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 268:26055-26058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frye, R. A. 2000. Phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic Sir2-like proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 273:793-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh, S., and M. Karin. 2002. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell 109(Suppl.):S81-S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon, S. 2003. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:23-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden, M. S., A. P. West, and S. Ghosh. 2006. NF-kappaB and the immune response. Oncogene 25:6758-6780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hotamisligil, G. S. 2006. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444:860-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imai, S., C. M. Armstrong, M. Kaeberlein, and L. Guarente. 2000. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature 403:795-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamei, N., K. Tobe, R. Suzuki, M. Ohsugi, T. Watanabe, N. Kubota, N. Ohtsuka-Kowatari, K. Kumagai, K. Sakamoto, M. Kobayashi, T. Yamauchi, K. Ueki, Y. Oishi, S. Nishimura, I. Manabe, H. Hashimoto, Y. Ohnishi, H. Ogata, K. Tokuyama, M. Tsunoda, T. Ide, K. Murakami, R. Nagai, and T. Kadowaki. 2006. Overexpression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in adipose tissues causes macrophage recruitment and insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 281:26602-26614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawahara, T. L., E. Michishita, A. S. Adler, M. Damian, E. Berber, M. Lin, R. A. McCord, K. C. Ongaigui, L. D. Boxer, H. Y. Chang, and K. F. Chua. 2009. SIRT6 links histone H3 lysine 9 deacetylation to NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression and organismal life span. Cell 136:62-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiernan, R., V. Bres, R. W. Ng, M. P. Coudart, S. El Messaoudi, C. Sardet, D. Y. Jin, S. Emiliani, and M. Benkirane. 2003. Post-activation turn-off of NF-kappa B-dependent transcription is regulated by acetylation of p65. J. Biol. Chem. 278:2758-2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, H. J., K. W. Kim, B. P. Yu, and H. Y. Chung. 2000. The effect of age on cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression: NF-kappaB activation and IkappaBalpha degradation. Free Radic Biol. Med. 28:683-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kisseleva, T., L. Song, M. Vorontchikhina, N. Feirt, J. Kitajewski, and C. Schindler. 2006. NF-kappaB regulation of endothelial cell function during LPS-induced toxemia and cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 116:2955-2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landry, J., A. Sutton, S. T. Tafrov, R. C. Heller, J. Stebbins, L. Pillus, and R. Sternglanz. 2000. The silencing protein SIR2 and its homologs are NAD-dependent protein deacetylases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:5807-5811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motta, M. C., N. Divecha, M. Lemieux, C. Kamel, D. Chen, W. Gu, Y. Bultsma, M. McBurney, and L. Guarente. 2004. Mammalian SIRT1 represses forkhead transcription factors. Cell 116:551-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nick, J. A., S. K. Young, K. K. Brown, N. J. Avdi, P. G. Arndt, B. T. Suratt, M. S. Janes, P. M. Henson, and G. S. Worthen. 2000. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in a murine model of pulmonary inflammation. J. Immunol. 164:2151-2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odegaard, J. I., R. R. Ricardo-Gonzalez, M. H. Goforth, C. R. Morel, V. Subramanian, L. Mukundan, A. R. Eagle, D. Vats, F. Brombacher, A. W. Ferrante, and A. Chawla. 2007. Macrophage-specific PPARgamma controls alternative activation and improves insulin resistance. Nature 447:1116-1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfluger, P. T., D. Herranz, S. Velasco-Miguel, M. Serrano, and M. H. Tschop. 2008. Sirt1 protects against high-fat diet-induced metabolic damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:9793-9798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purushotham, A., T. T. Schug, Q. Xu, S. Surapureddi, X. Guo, and X. Li. 2009. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SIRT1 alters fatty acid metabolism and results in hepatic steatosis and inflammation. Cell Metab. 9:327-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qin, L., X. Wu, M. L. Block, Y. Liu, G. R. Breese, J. S. Hong, D. J. Knapp, and F. T. Crews. 2007. Systemic LPS causes chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration. Glia 55:453-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen, Z., J. M. Ajmo, C. Q. Rogers, X. Liang, L. Le, M. M. Murr, Y. Peng, and M. You. 2009. Role of SIRT1 in regulation of LPS- or two ethanol metabolites-induced TNF-alpha production in cultured macrophage cell lines. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 296:G1047-G1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi, H., M. V. Kokoeva, K. Inouye, I. Tzameli, H. Yin, and J. S. Flier. 2006. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 116:3015-3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shoelson, S. E., J. Lee, and A. B. Goldfine. 2006. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 116:1793-1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith, J. S., C. B. Brachmann, I. Celic, M. A. Kenna, S. Muhammad, V. J. Starai, J. L. Avalos, J. C. Escalante-Semerena, C. Grubmeyer, C. Wolberger, and J. D. Boeke. 2000. A phylogenetically conserved NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase activity in the Sir2 protein family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6658-6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smoak, K., J. Madenspacher, S. Jeyaseelan, B. Williams, D. Dixon, K. R. Poch, J. A. Nick, G. S. Worthen, and M. B. Fessler. 2008. Effects of liver X receptor agonist treatment on pulmonary inflammation and host defense. J. Immunol. 180:3305-3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stephens, J. M., J. Lee, and P. F. Pilch. 1997. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes is accompanied by a loss of insulin receptor substrate-1 and GLUT4 expression without a loss of insulin receptor-mediated signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 272:971-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uysal, K. T., S. M. Wiesbrock, and G. S. Hotamisligil. 1998. Functional analysis of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors in TNF-alpha-mediated insulin resistance in genetic obesity. Endocrinology 139:4832-4838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uysal, K. T., S. M. Wiesbrock, M. W. Marino, and G. S. Hotamisligil. 1997. Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNF-alpha function. Nature 389:610-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weisberg, S. P., D. McCann, M. Desai, M. Rosenbaum, R. L. Leibel, and A. W. Ferrante, Jr. 2003. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Invest. 112:1796-1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woods, S. C., D. A. D'Alessio, P. Tso, P. A. Rushing, D. J. Clegg, S. C. Benoit, K. Gotoh, M. Liu, and R. J. Seeley. 2004. Consumption of a high-fat diet alters the homeostatic regulation of energy balance. Physiol. Behav. 83:573-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu, H., G. T. Barnes, Q. Yang, G. Tan, D. Yang, C. J. Chou, J. Sole, A. Nichols, J. S. Ross, L. A. Tartaglia, and H. Chen. 2003. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 112:1821-1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang, S. R., J. Wright, M. Bauter, K. Seweryniak, A. Kode, and I. Rahman. 2007. Sirtuin regulates cigarette smoke-induced proinflammatory mediator release via RelA/p65 NF-kappaB in macrophages in vitro and in rat lungs in vivo: implications for chronic inflammation and aging. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 292:L567-L576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeung, F., J. E. Hoberg, C. S. Ramsey, M. D. Keller, D. R. Jones, R. A. Frye, and M. W. Mayo. 2004. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 23:2369-2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshizaki, T., J. C. Milne, T. Imamura, S. Schenk, N. Sonoda, J. L. Babendure, J. C. Lu, J. J. Smith, M. R. Jirousek, and J. M. Olefsky. 2009. SIRT1 exerts anti-inflammatory effects and improves insulin sensitivity in adipocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:1363-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshizaki, T., S. Schenk, T. Imamura, J. L. Babendure, N. Sonoda, E. J. Bae, Y. Ohda, M. Lu, J. C. Milne, C. Westphal, G. Bandyopadhyay, and J. M. Olefsky. 2010. SIRT1 inhibits inflammatory pathways in macrophages and modulates insulin sensitivity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 298:E419-E428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang, X., G. Zhang, H. Zhang, M. Karin, H. Bai, and D. Cai. 2008. Hypothalamic IKKbeta/NF-kappaB and ER stress link overnutrition to energy imbalance and obesity. Cell 135:61-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]