Abstract

The expression of thrombomodulin (TM), a calcium-dependent adhesion molecule, is frequently downregulated in various cancer types. However, the mechanism responsible for the low expression level of TM in tumorigenesis is unknown. Here, an inverse expression of TM and Snail was detected in different cancer cell lines. We further confirmed this inverse relation using the epithelial-mesenchymal transition cell model in HaCaT and A431 cells. We demonstrated that Snail suppressed TM expression by binding to E-box (CACCTG) in TM promoter. Moreover, TM knockdown by short hairpin RNA disrupted E-cadherin-mediated cell junctions and contributed to tumorigenesis. In the calcium switch assay, E-cadherin lost the ability to associate with β-catenin and accumulated in cytoplasm in TM knockdown cells. Meanwhile, wound healing and invasive assays showed that TM knockdown promoted cell motility. A subcutaneous injection of TM knockdown transfectants into immunocompromised mice induced squamous cell carcinoma-like tumors. Besides, forced expression of murine TM in TM knockdown cells made the cells reassume epithelium-like morphology and increased calcium-dependent association of E-cadherin and β-catenin. In conclusion, TM, a novel downstream target of Snail in epithelial-mesenchymal transition, is required for maintaining epithelial morphology and functions as a tumor suppressor.

Thrombomodulin (TM), a type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein, was first identified in endothelial cells and is well known as an anticoagulant factor (12). TM consists of 557 amino acid residues arranged in five distinct domains including an NH2-terminal lectin-like domain, a domain with six epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like structures that contain thrombin binding sites, an O-glycosylation site-rich domain, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tail (43). Depletion of the TM gene leads to embryonic lethality due to an impaired cardiovascular system (18). TM was later found in human keratinocytes and served as a differential biomarker for the clinical stages of skin cancers (36). Recent studies further revealed that TM has pleiotropic effects in both physiology and pathology via its different domains, including the calcium-dependent control of cell-cell adhesion by its lectin-like domain (20), angiogenic stimulation by its EGF domain (38), and anti-inflammatory effect by its lectin-like domain in sepsis via binding to Lewis-Y, a tetrasaccharide expressed on the surface of pathogens (39).

Mesenchymal-epithelial transition is characterized as a morphological change from fibroblast-like to epithelium-like cells, which is the reverse of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Transfection of human TM cDNA into A2058 melanoma cells with fibroblast-like shape inhibited cell proliferation in vitro and reduced xenograft tumor growth in immunocompromised mice (20). We also found that A2058 cells stably expressing ectopic TM induced closely clustered colonies, reminiscent of mesenchymal-epithelial transition. The effect of TM in promoting epithelial morphogenesis is consistent with the clinical observations that reduced TM expression is associated with poor prognosis for patients with tumor metastases in lung (31), breast (24), and colorectal (16) cancer. These data suggest that TM may play a negative regulatory role in tumorigenesis by modulating the assembly of cell junctions. However, the exact mechanism underlying TM downregulation and the correlation between TM and E-cadherin involved in tumorigenesis have never been investigated.

E-cadherin is a major component of adherens junctions and mediates cell-cell adhesion in a calcium-dependent manner. Loss of E-cadherin expression was correlated with increased invasive potential of both carcinoma cell lines and tumor samples (10). Reduced E-cadherin expression or altered subcellular localization of E-cadherin protein has been reported in the cells undergoing EMT and different human cancers such as primary tumors of esophagus, stomach (41), and pancreas (34). In contrast, E-cadherin overexpression increased cell-cell adhesion and suppressed gelatinase secretion and cell growth and thereby partially suppressed tumorigenesis in HaCa4 carcinoma cells (30). Moreover, E-cadherin expression in cells is repressed by members of the Snail superfamily, including Snail, Slug, and E12/47 (4). The suppression also causes epidermal cell lines, MCA3D and PDV cells, to assume a mesenchymal phenotype and acquire tumorigenic properties (9). Like E-cadherin, TM functioned as a calcium-dependent cell-to-cell adhesion molecule and its ectopic expression induced a fibroblastic-to-epithelial morphological change in A2058 melanoma cells (20). Since both TM and E-cadherin mediated cell adhesion and are expressed at low levels in metastatic tumors, downregulation of TM may also participate in tumorigenesis and Snail-mediated EMT.

EMT, which involves characteristic change in cellular morphology from an epithelial to a fibroblast-like phenotype, loss of cell-cell junctions, and increase in cell motility and cell proliferation, frequently takes place in embryonic development (42), cancer progression (22), and wound healing (1). Downregulation of adhesion molecules is documented to induce EMT via either reducing E-cadherin expression or abolishing E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contact. For instance, knockdown of claudin 7, the major component of intercellular tight junctions, can directly lead to decreased E-cadherin expression, cell morphology changes, and motility enhancement in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (26). In contrast, knockdown of mucin (MUC-1), a human epithelial tumor antigen and tumor-associated glycoprotein, increases E-cadherin/β-catenin complex formation and restores E-cadherin localization at the cell membrane in PANC1 pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells (47). Together, these results indicate that a loss in the architecture of epithelial cell junctions might lead to the acquisition of mesenchymal cell behavior.

Chemokine-mediated signaling pathways are involved in the process of EMT (14). Among many chemokines, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) has dual functions in tumor growth, inhibiting tumor growth in the early stage but facilitating tumor invasion and metastasis in the later stage of carcinogenesis (37). Normal murine mammary gland (NMuMG) and mouse cortical tubular (MCT) epithelial cells are among a few primary cultured cells and cell lines that are used as models to investigate the mechanism of TGF-β action in EMT. A morphological change of these cells induced by the treatment with TGF-β1 accompanies the loss of E-cadherin (8). Moreover, TGF-β1 together with EGF can synergistically induce EMT in HaCaT cells, spontaneously immortalized keratinocytes, through the activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent signal transduction pathway (11). Furthermore, scatter factors, such as hepatocyte growth factor and EGF, modulate E-cadherin and induce EMT via different mechanisms. Hepatocyte growth factor disrupts cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion between keratinocytes (45), whereas EGF modulates the phosphorylation of the cadherin-catenin system in the human esophageal cancer cell line TE-2R, which expresses E-cadherin and the EGF receptor (40).

Snail, a zinc finger transcriptional factor, functions as a regulator to suppress the expression of adhesion molecules and to assist the escape of tumor cells from cell death during EMT (44). Besides having a regulatory role in EMT, Snail also regulates genes that are associated with EMT-independent biological functions, including mesodermal determinants, cell movement, and cell survival. Snail is frequently expressed in many types of tumor cells in which E-cadherin expression is reduced. Moreover, this inverse relationship of Snail and E-cadherin was often observed in the invasive types of tumors (3). Later studies confirmed a suppressing effect of Snail expression on E-cadherin promoter via a specific binding to the three E-boxes (CACCTG) in the promoter region at −178 to +92 of the E-cadherin gene (2).

In this study, we investigated the relationship of TM and several EMT markers in various tumor cells and the in vitro EMT model induced by cotreatment of TGF-β1 and EGF. A direct Snail binding to the proximal TM promoter was identified by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), and promoter-driven luciferase reporter assay. The knockdown approach was used to examine the role of TM in cell migration, invasion, and tumorigenesis and to confirm the inverse relationship of TM expression and Snail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and treatment.

The basal cell carcinoma (BCC) was kindly provided by Hamm-Ming Sheu. TSGH8301 was purchased from Food Industry Research and Development Institute (Hsinchu, Taiwan). A2058, DU145, A431, HepG2, Huh7, HeLa, SiHa, Cx, and KB cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The culture conditions of HaCaT cells were the same as previously described (5). HaCaT cells that overexpressed Snail were prepared by transfecting cells with pcDNA3-mm snail-HA, ectopic Snail with hemagglutinin (HA) (a kind gift of A. G. de Herreros), using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and selecting them with 600 μg/ml G418. Silencing of TM gene expression in HaCaT cells was accomplished using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) technology by the pSM2c vector system (Gendiscovery). Two shRNA sequences specific to TM (Table 1) were cloned into pSM2c vector. HaCaT cells were transfected with these two constructs or with empty vector and selected with 1 μg/ml puromycin. Cell morphology was observed with a phase-contrast microscope (Leica model DM). Images were obtained using a 40× objective (numerical aperture [NA], 1.4).

TABLE 1.

Short hairpin sequences specific to TM

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′)a |

|---|---|

| TM1.6 (specific target of sh-TM1) | TGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGACCAATTAGGGCCTAGCCTTAATAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTATTAAGGCTAGGCCCTAATTGGGTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA |

| TM1.9 (specific target of sh-TM2 and -3) | TGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGACCCAATTAGGGCCTAGCCTTATAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTATAAGGCTAGGCCCTAATTGGGCTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA |

Boldface indicates the mir-30 loop construct sequence in the hairpin; underlining indicates the antisense/target sequence 19-mer; italics indicate the sense/target sequence 19-mer.

Constructs and transfections.

Full-length cDNA of murine TM (mTM) was constructed in an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector with green fluorescent protein. This construct was transiently transfected into cells with an electroporation system as described by the manufacturer (Promega).

Western blotting.

Cell extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and proteins were detected with antibodies that were specific to E-cadherin (Calbiochem), N-cadherin (Calbiochem), TM (D3; Santa Cruz), Snail (Abcam), or HA (F-7; Santa Cruz). The same membranes were also probed to detect α-tubulin (DM1A; Calbiochem) as loading controls. The images were captured with LAS-3000 (Fujifilm).

Immunofluorescent staining.

Cells were fixed in 3.7% (vol/vol) formaldehyde solution, permeabilized with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, blocked with 10% fetal bovine serum for 30 min at room temperature, and incubated with antibodies specific for TM (clone 1009; Dako), E-cadherin (Calbiochem), β-catenin (BD Biosciences), Snail (Abcam), nonspecific mouse IgG (Rockland), or rabbit IgG (Rockland) for 2 h. This was followed by incubation of cells with secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) for 1 h or phalloidin (BD Biosciences) for 30 min. Images were obtained using either a fluorescence microscope (DMIRE2; Leica) with a 40× objective (NA, 0.5) or a confocal microscope (SP2; Leica) with a 63× oil-immersion (NA, 1.4) objective.

EMSA.

Forward and reverse oligonucleotides (synthesized by Life Technologies, Invitrogen) were annealed and radiolabeled according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). EMSAs were performed with nuclear extracts of TGF-β1- and EGF-cotreated HaCaT cells. The different probes used were (i) wild-type probe for TM and (ii) mutant probe for TM (Table 2). In competition assays, excess of the wild-type probe or mutant probe, either 20- or 50-fold molar, was added and the reaction mixture was incubated on ice. DNA-protein complexes were separated on 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels in TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) at room temperature. The gels were dried and visualized by autoradiography.

TABLE 2.

Probe sequences of TM in EMSA

| Probe | Sequence (5′-3′)a |

|---|---|

| Wild type | S: 5′-GCAATTCACCTGCCACCGCCT-3′ |

| AS: 5′-AAGCGGTGGCAGGTGAATTGC-3′ | |

| Mutant | S: 5′-GCAATTAACCTACCACCGCCT-3′ |

| AS: 5′-AGGCGGTGGTAGGTTAATTGC-3′ |

S, sense; AS, antisense.

Reporter gene assay.

TM promoter activity assays were carried out in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells using 400 ng of human TM promoter (position numbers −1014/−745) cloned in the pcDNA3.1 basic vector (Promega). Cells were cotransfected with pcDNA3-mm snail-HA and each of several different TM promoter truncation-derived pGL3-based luciferase vectors. Ten nanograms of pSG5-LacZ plasmid was the control for transfection efficiency. The expression of firefly and β-galactosidase was analyzed by a Dual-Light gene assay system (Promega) 48 h after transfection.

ChIP assay.

ChIP assay was performed according to a published procedure (Millipore). The sequences for PCR primers are provided in Table 3. PCR conditions for TM were denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 50°C for 30 s, and extension at 70°C for 30 s, for 35 cycles.

TABLE 3.

ChIP assay primer sequences

| Primer | Direction | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Forward | ACTCAGCGGGACGTTTGG |

| Reverse | GGCCCAGTAGATCCAGGG | |

| 2 | Forward | GTGCAAGAAGCACCATCCTT |

| Reverse | CCAGACCCCATCTCATCG | |

| 3 | Forward | GAGCTCTTGCAATCCAGG |

| Reverse | CTGTAACAAGACGACTGT |

Wound healing assay and individual cell tracking.

TM-expressing HaCaT cells (pSM2c and sh-TM1) and TM knockdown HaCaT cells (sh-TM2 and sh-TM3) were grown to full confluence and wounded with a p200 pipette tip. The images were recorded for 24 h by time-lapse microscopy (Leica DMIRE2) with a 5× objective (NA, 0.25). Percentage of wound closure was analyzed by Image-J software and calculated by the formula [(wound area at 0 h − wound area at 24 h)/wound area at 0 h] × 100%. For tracking individual cells, the migration paths of 15 cells at the wound margin were recorded at 30-min intervals for 24 h by time-lapse microscopy and were analyzed by MetaMorph imaging software (Universal Imaging Corp.).

Invasion assay.

In the invasion assay, a porous membrane was coated with 1 mg/ml Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in serum-free high-glucose Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) at 4°C overnight. Cells were seeded in the upper compartment of the chamber containing 2% serum; medium containing 10% serum was added to the lower chamber as chemoattractant. The chambers were incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Cells that had migrated to the lower side were fixed and stained with Liu's solution (Hand Sel Technologies, Inc.). Random fields of the migrated cells were counted using a 20× (NA, 0.3) objective.

Coimmunoprecipitation assay.

Cells were lysed with lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 2% SDS, Triton X-100, and complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science). The cell extract lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, used immediately for immunoprecipitation, and precleaned with protein G-Sepharose 4 FastFlow beads (Amersham GE Healthcare Bio-Science) for 1 h, and the beads were removed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 3 min. Precleaned supernatants were incubated overnight either with pan-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (pan-ERK) as a nonspecific mouse IgG control or with E-cadherin-specific antibody in the presence of the beads. Immunocomplexes bound to beads were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,600 rpm for 5 min, washed five times with lysis buffer without protease inhibitors, eluted in SDS-PAGE loading buffer at 95°C for 10 min, and separated by SDS-PAGE.

Cell fractionation.

Cells were scraped and homogenized in ice-cold homogenization buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitors) using a sonicator (Misonix; S-3000). Cell lysates were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 10 min. The cytoplasmic fraction was collected following the removal of membrane by centrifugation of cell lysates at 13,000 rpm for 30 min. The membrane fractions were dissolved in homogenization buffer with 1% NP-40. Membrane and cytoplasmic fractions were analyzed by Western blotting.

Tumorigenesis of TM knockdown transfectants in NOD-SCID mice.

pSM2c (vector control), sh-TM1, sh-TM2, and sh-TM3 cell suspensions (5 × 106/mouse) were subcutaneously injected into 8-week-old nonobese diabetic severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD-SCID) mice. Tumor growth was monitored every 2 days for 2 months. Tumors that grew to a volume over 500 mm3 and did not regress were considered to be established tumors. Tumors were not allowed to grow beyond 2,000 mm3 in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulations. Tumors were photographed and weighed after mice were sacrificed.

Immunohistochemistry staining.

Paraffin-embedded blocks containing mouse tumor tissue were fixed in 3.7% formalin and processed for hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemical analysis. Tissue sections were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the primary antibodies bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (BD Biosciences) and loricrin (Covance) were applied to slides and incubated overnight. LSAB2 System horseradish peroxidase as secondary antibody was applied to slides for 1 h. The immune complex was visualized after incubation with β-amino-9-ethyl-carbazole (Dako) as a substrate.

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD). Statistical significance of differences between any two groups was analyzed using an unpaired Student t test. Differences between more than two groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test, with a P value of <0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Inverse expression of TM and Snail.

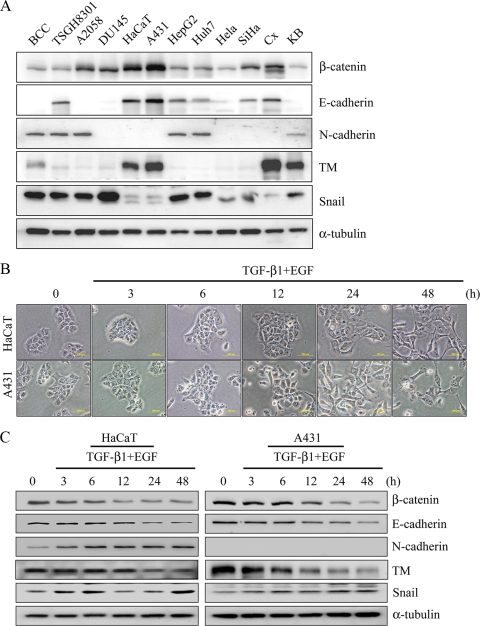

Whether TM downregulation involves EMT-mediated tumorigenesis has never been investigated. We first analyzed the expression levels of EMT markers and TM in diverse epithelial cells and tumor cells. In 9/12 (75%) cells, Snail was highly expressed in BCC, TSGH8301, A2058, DU145, HepG2, Huh7, HeLa, SiHa, and KB cells that were accompanied by downregulation of both E-cadherin and TM. In the same line of observation, N-cadherin, a mesenchymal marker, was detected mostly in high-Snail-expressing cells, BCC, TSGH8301, A2058, HepG2, Huh7, and KB cells (50%). In contrast, low expression of Snail was observed in HaCaT, A431, and Cx with high levels of β-catenin, E-cadherin, and TM (25%) (Fig. 1A). The 12 cell lines were analyzed for their relative expression (fold) of β-catenin, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, TM, and Snail (Table 4). These results are consistent with the notion that adhesion molecules are often downregulated in tumorigenesis (10, 26). Therefore, an inverse expression of TM and Snail suggests a role of TM in EMT.

FIG. 1.

Downregulation of TM in tumor cells associated with EMT. (A) Diverse cell lines were analyzed with epithelial (β-catenin and E-cadherin) and mesenchymal (N-cadherin and Snail) markers, and TM expression levels were analyzed by Western blotting. α-Tubulin was used as loading control. BCC, basal cell carcinoma; TSGH8301, bladder cancer cell line; A2058, human skin melanoma; DU145, prostate cancer cell line; HaCaT, human skin keratinocytes; A431, human epidermoid carcinoma; HepG2 and Huh7, hepatocellular cancer cells; HeLa, SiHa, and Cx, cervical cancer cells; KB, oral cancer cells. (B) HaCaT and A431 cells were cultured in serum-free medium and then cotreated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) and EGF (10 ng/ml) (TGF-β1+EGF) for indicated periods of time (3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h). Cells were observed with a phase-contrast microscope. Bar, 200 μm. (C) Expression levels of β-catenin, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, TM, and Snail were analyzed by Western blotting. α-Tubulin was the loading control. Triplicate experiments (mean ± SD, n = 3). The relative protein expression levels at indicated times were quantified by Prism software. (D) Distribution of Snail in HaCaT and A431 cells after treatment with TGF-β1 and EGF for 48 h. Snail expression was detected by immunofluorescent staining. Bars, 200 μm. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining was used for nucleic counting.

TABLE 4.

Cell line phenotypes

| Cell line | Relative expression (fold) ofa: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Catenin | E-cadherin | N-cadherin | TM | Snail | |

| BCC | 1.0 | 0 | 1.3 | 8.9 | 11.1 |

| TSGH8301 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 14.0 |

| A2058 | 3.6 | 0 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 9.7 |

| DU145 | 4.7 | 0 | 0 | 1.9 | 23.1 |

| HaCaT | 9.0 | 2.2 | 0 | 35.3 | 1.3 |

| A431 | 15.4 | 3.4 | 0 | 49.9 | 1.0 |

| HepG2 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 21.8 |

| Huh7 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 15.5 |

| HeLa | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 1.4 | 2.8 |

| SiHa | 3.6 | 0.6 | 0 | 2.0 | 4.7 |

| Cx | 6.7 | 1.7 | 0 | 79.2 | 1.6 |

| KB | 1.3 | 0 | 1.0 | 53.5 | 10.5 |

The relative expression levels (fold) of β-catenin, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, TM, and Snail were normalized by α-tubulin.

Snail is a key transcription factor participating in EMT. It has been demonstrated that EMT can be induced by cotreatment of HaCaT cells with TGF-β1 and EGF via sustained activation of Ras during EMT (11). In order to investigate the relationship of TM and Snail expression during EMT, HaCaT cells were used to establish an in vitro EMT model. Consistent with the earlier report, treated cells shifted from epithelial to fibroblast-like morphology and lost cell-cell contact following a 48-h cotreatment of HaCaT with TGF-β1 and EGF (Fig. 1B, top panels). In line with EMT, β-catenin downregulation, an inverse expression of E- and N-cadherin, TM downregulation, and Snail upregulation were observed in these cells by Western blotting (Fig. 1C, left panel). Immunofluorescent microscopy confirmed the nuclear expression of Snail in the cotreated cells (Fig. 1D, left panels). Similar results were also observed in skin-derived A431 cells treated for 48 h with TGF-β1 and EGF (Fig. 1B, C, and D).

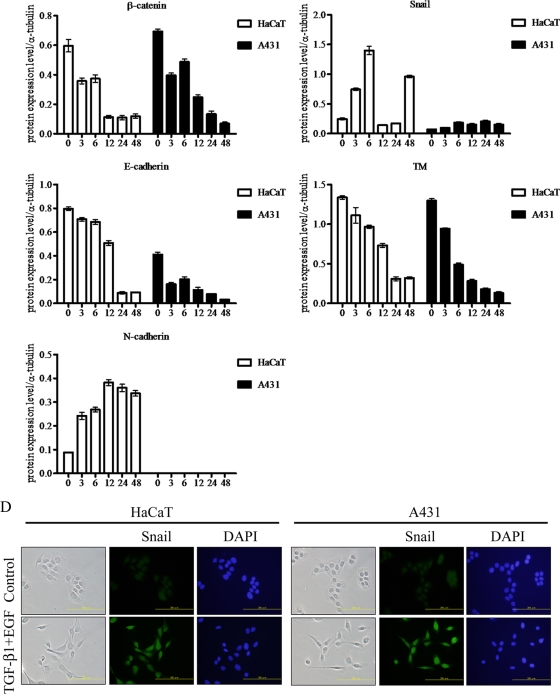

Snail directly suppresses TM and E-cadherin expression.

HaCaT cells with a functional form of TM in cell adhesion (20) were chosen as a model to investigate the potential involvement of TM in EMT. We next determined whether ectopic Snail-HA expression in HaCaT cells had any effect on cell morphology, TM expression, or the expression and distribution of E-cadherin on cell membranes. We first established stable HaCaT clones expressing ectopic Snail-HA. The expression of both E-cadherin and TM was downregulated while that of N-cadherin was increased in clones 5 and 7 of Snail-HA-transfected HaCaT cells as shown by Western blotting (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the cells with ectopic Snail expression assumed a fibroblast-like morphology (Fig. 2B, top panels). Immunofluorescent staining confirmed the inverse expression of Snail with TM or E-cadherin (Fig. 2B, panels a to i). β-Catenin is an interacting protein of E-cadherin in the adherens junction and participates in maintaining epithelial cell-like morphology. Although there was no gross change in β-catenin expression, a discontinuous rather than a continuous presence of β-catenin was observed at the cell-cell boundary of Snail-HA-expressing cells (Fig. 2B, panels j to l). Together, these results indicate that Snail may suppress TM expression in a fashion similar to its repressing effect on E-cadherin during EMT.

FIG. 2.

Snail directly suppresses TM and E-cadherin expression. (A) Expression levels of β-catenin, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, TM, and Snail were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-β-catenin, anti-E-cadherin, anti-N-cadherin, anti-TM lectin-like domain (D3), and anti-HA antibodies. Numbers 5 and 7 refer to Snail-HA clones 5 and 7. (B) HaCaT cells with stable transfection of pcDNA3.1 as vector control and HA-tagged snail (Snail-HA) (clones 5 and 7) were observed by phase-contrast microscopy. Cells were stained with polyclonal Snail antibody (a to c), monoclonal TM antibody (Dako) (d to f), monoclonal E-cadherin antibody (g to i), or monoclonal β-catenin antibody (j to l) as primary antibodies and Alexa 488 as the secondary antibody. Cells were observed by immunofluorescent microscopy. Bars, 200 μm. DAPI staining was used for nucleic counting.

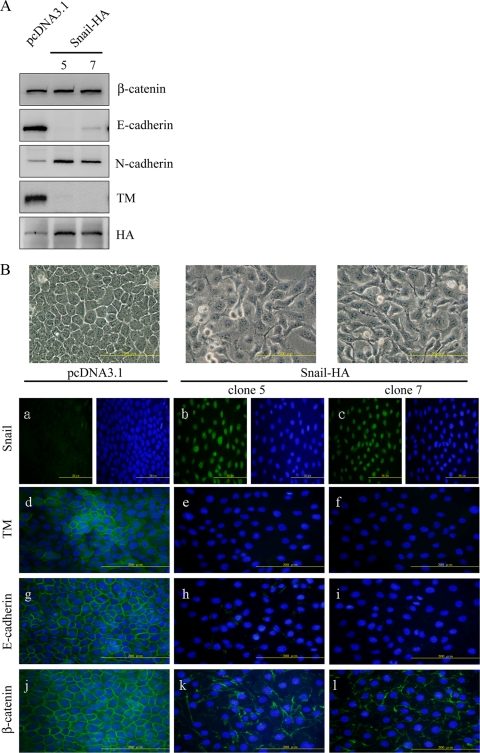

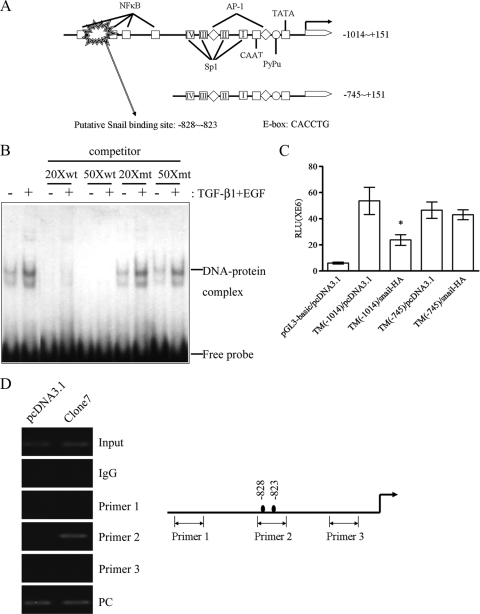

Binding of Snail to TM promoter suppresses TM expression.

Since TGF-β1 together with EGF induced an inverse expression of TM and Snail during EMT of HaCaT and A431 cells (Fig. 1B, C, and D), Snail, a transcription factor, may modulate TM expression. By sequence alignment, a putative Snail binding site (CACCTG) was identified between bp −828 and −823 upstream from the transcription start site in the promoter region of the TM gene (Fig. 3A). The sequence of the putative Snail binding site on the proximal TM promoter was used to design wild-type and mutated probes for EMSA. A protein-DNA complex was observed in the reaction of the wild-type probe and nuclear extracts of TGF-β1- and EGF-cotreated HaCaT cells. Moreover, only excess cold wild-type probe, but not mutated probe, could effectively compete for the protein binding to the radiolabeled wild-type probes, indicating a specific binding of the nuclear protein to the putative Snail binding site (Fig. 3B). We next tested the exogenous effect of Snail on the activity of TM promoter fragments using a dual-luciferase reporter gene assay in CHO cells, which are more susceptible than HaCaT cells to transient transfection. Consistent with the presence of a putative Snail binding site at bp −828 to −823, the promoter activity of TM (−1014) was significantly suppressed by cotransfected Snail-HA in CHO cells. When the TM promoter sequence was deleted to −745, Snail-HA showed significantly reduced ability to suppress the promoter activity of the TM (−745) promoter construct (Fig. 3C). Moreover, the in vivo direct binding of Snail-HA to the putative Snail binding site on the proximal TM promoter sites was demonstrated by ChIP assay in ectopic Snail-expressing HaCaT cells (Fig. 3D, clone 7). Thus, the region between −1014 and −745 on the TM promoter harboring a Snail binding sequence is required for negative regulation of the TM promoter by Snail.

FIG. 3.

Snail specifically binds to TM promoter. (A) A scheme of the predicted Snail binding site in TM promoter region spanning from bp −828 to −823. (B) HaCaT cells were cotreated with TGF-β1 and EGF for 48 h to induce Snail expression, and the nuclear extracts were subjected to EMSA. wt, wild-type probe; mt, mutated probe; competitor, unlabeled probes. (C) The effect of Snail on the activity of the TM promoter was assayed by cotransfection of different TM promoter fragment-driven reporter constructs, TM (−1014) and TM (−745), and pcDNA3-mm snail-HA (snail-HA) in CHO cells. Triplicate experiments (mean ± SD, n = 3). *, P < 0.05 versus pGL3-basic/pcDNA3.1. (D) Cross-linked chromatin was immunoprecipitated with an antibody to Snail, in the absence of antibody (Input), or with an isotype-matched immunoglobulin (IgG). Isolated DNA was purified and analyzed by PCR using primers to the region of the TM promoter. The PCR products were analyzed on 2% agarose gels.

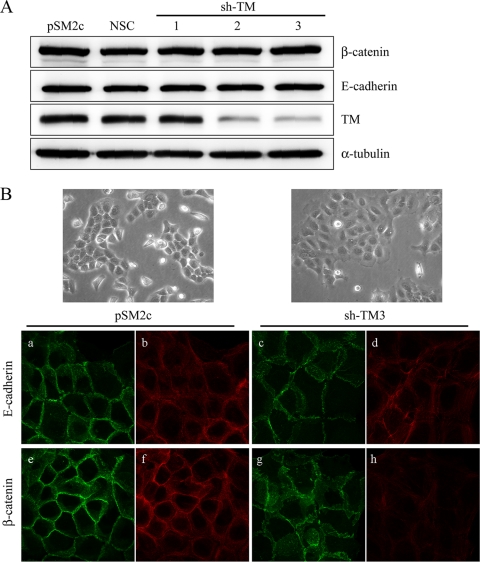

TM knockdown induces E-cadherin and β-catenin dissociation from cell membrane.

To investigate the role of TM in the association of E-cadherin and β-catenin in EMT, several HaCaT cell lines were established, including pSM2c (vector control), NSC (nonsilencing control), sh-TM1 (TM nonknockdown transfectant), and sh-TM2 and sh-TM3 (TM knockdown transfectants). Western blot analysis confirmed the decreased TM expression in knockdown cells, and this knockdown had no effect on the protein expression levels of β-catenin and E-cadherin (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, we observed that TM knockdown cells (sh-TM3) had flat cell morphology with overlapping cell-cell contact in comparison with the TM-expressing cells (pSM2c) (Fig. 4B). We also found that sh-TM3 cells had higher permeability than pSM2c cells, suggesting that TM knockdown induced loose cell-cell connections (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To evaluate whether the morphological change induced by TM knockdown was involved in E-cadherin redistribution at cell contact, we cultured pSM2c and sh-TM3 cells to confluence and examined the subcellular localization of E-cadherin and β-catenin by immunofluorescent staining. We found that both E-cadherin and β-catenin could regularly align at cell junctions in control pSM2c cells (Fig. 4B, panels a and e). In contrast, E-cadherin and β-catenin were dislodged from cell-cell junctions in TM knockdown sh-TM3 cells (Fig. 4B, panels c and g). The F-actin aligned along the cell-cell junctions in the pSM2c cells (Fig. 4B, panels b and f) but disappeared in the sh-TM3 cells (Fig. 4B, panels d and h). Altogether, TM downregulation disrupted cell contact probably by affecting the association of E-cadherin with β-catenin, indicating an essential role of TM in E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contact.

FIG. 4.

TM is necessary for E-cadherin and β-catenin to localize to cell membrane. (A) Cell extracts of TM-expressing HaCaT cells (pSM2c, NSC, and sh-TM1) and TM knockdown HaCaT cells (sh-TM2 and sh-TM3) were subjected to Western blotting with anti-β-catenin, anti-E-cadherin, and anti-TM lectin-like domain (D3) antibodies. α-Tubulin was the loading control. (B) Confluent pSM2c and sh-TM3 cells were stained with either anti-E-cadherin monoclonal antibody (a and c) or anti-β-catenin monoclonal antibodies (e and g) as primary antibodies and Alexa 488 (green channel) as secondary antibody. Phalloidin was specific for actin staining (b, d, f, and h) (red channel).

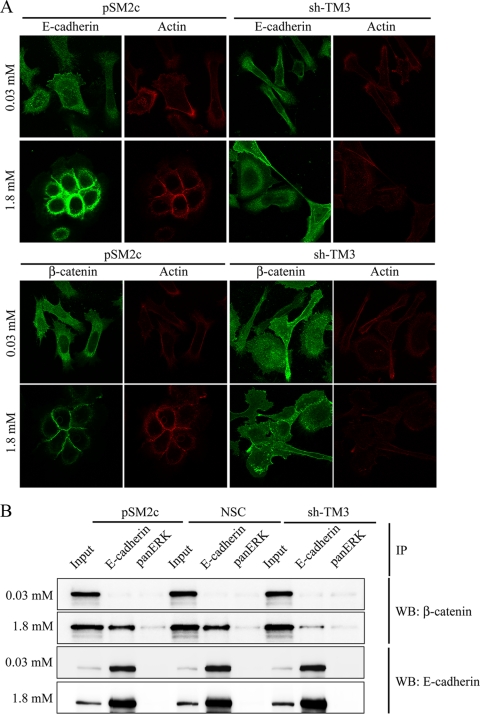

TM knockdown abolishes E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contact formation.

Since TM knockdown had a negative effect on the integrity of cell-cell junctions, we next examined if TM knockdown also had an impact on cell junction rebuilding. A calcium switch assay was used to test how TM regulated E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contacts. TM-expressing HaCaT cells (pSM2c) and TM knockdown HaCaT cells (sh-TM3) were cultured in 0.03 mM calcium-containing medium for 24 h and then in 1.8 mM calcium-containing medium for another 24 h. After calcium switch, control pSM2c cells reassumed epithelial morphology. Conversely, sh-TM3 cells remained fibroblast-like and the distribution of E-cadherin and β-catenin was diffused in the cytoplasm even when they were exposed to 1.8 mM calcium for 24 h (Fig. 5A). The coimmunoprecipitation assay demonstrated that calcium switch reduced the association of E-cadherin with β-catenin in sh-TM3 cells compared with pSM2c and NSC cells (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, we extracted cytoplasmic and membrane fractions to determine whether TM is essential in E-cadherin dynamics. We found that E-cadherin in pSM2c cells, but not sh-TM3 cells, could translocate from cytoplasm to cell membrane after the calcium concentration was switched from 0.03 mM to 1.8 mM (Fig. 5C). Based on these observations, we conclude that TM is required for maintaining epithelial cell-cell adhesion by maintaining E-cadherin on cell membrane.

FIG. 5.

TM knockdown abolishes E-cadherin-mediated cell junction rebuilding. (A) In calcium switch assay, pSM2c and sh-TM3 cells were cultured in 0.03 mM calcium-containing medium for 24 h prior to replacement with 1.8 mM calcium-containing medium for another 24 h. Then the cells were stained with E-cadherin monoclonal antibody or β-catenin monoclonal antibody as primary antibody and Alexa 488 as the secondary antibody with phalloidin for staining F-actin fibers. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of E-cadherin and β-catenin in pSM2c, NSC, and sh-TM3 cells was performed in a calcium switch assay. Anti-E-cadherin antibody was used to capture the immune complex of E-cadherin and β-catenin. Anti-pan-ERK antibody was used as a nonspecific IgG control. The samples were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-β-catenin and anti-E-cadherin antibodies. Triplicate experiments (mean ± SD, n = 3). The relative protein expression levels at indicated periods of time were quantified by Prism software. (C) Cell fractionation of pSM2c, NSC, and sh-TM3 was done in a calcium switch assay. The expression levels of E-cadherin and TM in cytoplasmic fraction (S) and membrane fraction (I) were detected by Western blotting with antibodies specific to E-cadherin and TM (D3 clone), respectively. Triplicate experiments (mean ± SD, n = 3). The relative protein expression levels at indicated periods of time were quantified by Prism software.

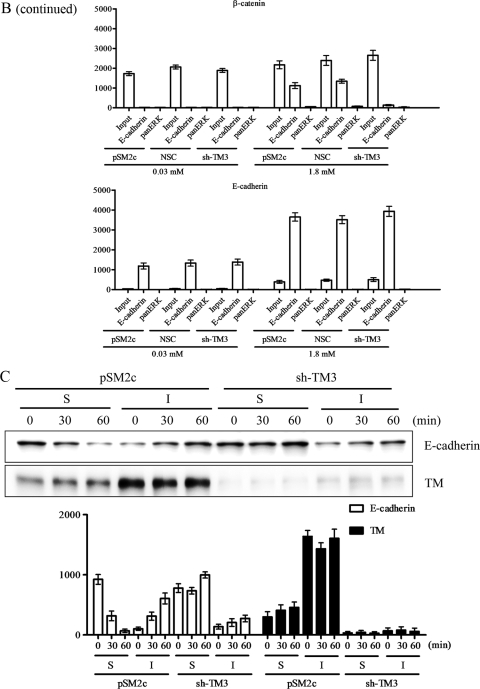

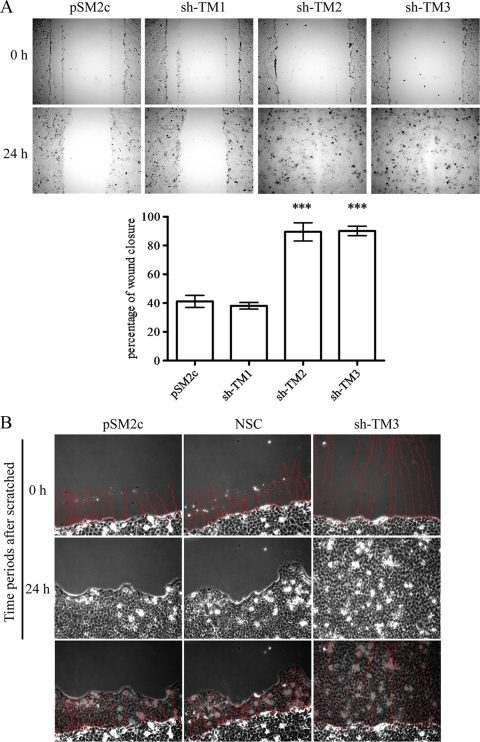

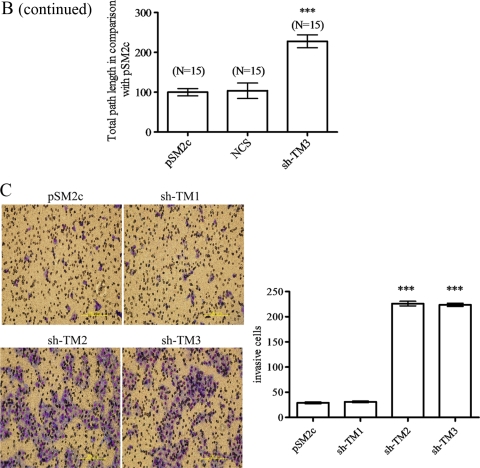

TM knockdown promotes cell motility.

Since E-cadherin is important in contact inhibition, loss of E-cadherin leads to the increase in cell migration and invasion (6, 28). Meanwhile, we found that TM knockdown represented loose cell-cell connections (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), suggesting that TM knockdown might impair cell contact and contribute to cell motility. We next investigated whether TM had a similar role in cell motility. The migratory and invasive abilities of TM knockdown clones were measured by wound healing and assays with Boyden chambers coated with Matrigel, respectively. We found that the migratory ability of TM knockdown cells (sh-TM2 and sh-TM3) was significantly increased in comparison with TM-expressing cells (pSM2c and sh-TM1) (Fig. 6A). After wound scratching, we also monitored the migration paths of 15 individual cells by time-lapse microscopy. We observed that sh-TM3 cells had higher cell motility than did control cells and moved forward as a sheet, suggesting that TM knockdown directly impaired cell contact (Fig. 6B). Consistent with the reduced TM expression in metastatic tumors (16, 24, 31), TM knockdown significantly promoted the invasive ability of cells (Fig. 6C). Therefore, TM and E-cadherin are key mediators for cell-cell contact, cell migration, and cell invasion.

FIG. 6.

TM knockdown increases cell motility and invasion. (A) The migratory abilities of TM-expressing (pSM2c and sh-TM1) and TM knockdown (sh-TM2 and sh-TM3) HaCaT transfectants were independently tested 3 times by scrape wound healing assay. The number of migrated cells was counted with Image J software and statistically analyzed by Graph Pad software (mean ± SD; n = 3). ***, P < 0.001 versus pSM2c. (B) Individual cell migration paths were monitored for 24 h postwounding by time-lapse microscopy, and data were expressed as percentages of control pSM2c value (mean ± SD; n = 15, 3 repeats). ***, P < 0.001 versus pSM2c. (C) Cell invasion was measured as described in Materials and Methods. The number of cells that invaded through Matrigel was counted with an Alpha-Image analyzer and analyzed by the software program Prism (mean ± SD; n = 11). Triplicate experiments. ***, P < 0.001 versus pSM2c.

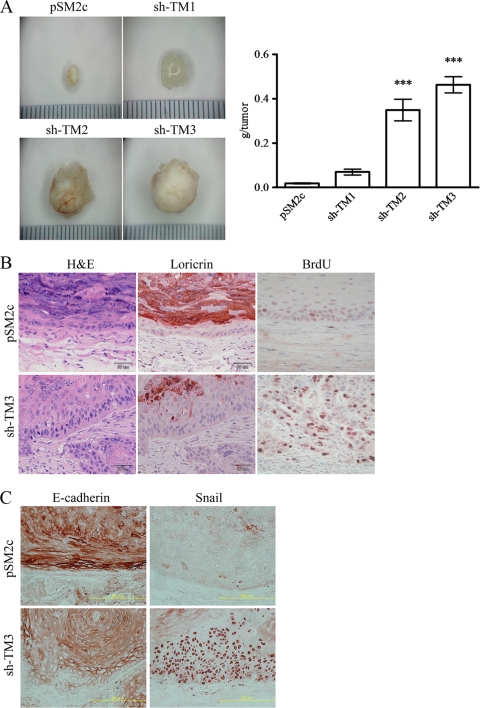

TM knockdown induces SCC-like tumors.

Since TM downregulation led to a morphological change reminiscent of EMT in HaCaT cells, we next examined if TM downregulation had any effect on the tumor-forming ability of HaCaT in immunocompromised NOD-SCID mice. Inoculation of NOD-SCID mice with TM knockdown cells (sh-TM2 and sh-TM3), but not TM-expressing HaCaT cells (pSM2c and sh-TM1), induced the growth of tumors (Fig. 7A). H&E staining was used to examine the effect of TM knockdown in tumor sections harvested from mice (Fig. 7B, far left panels). Moreover, the epidermal layer of sh-TM3 cell-derived tumors was much thicker than the layer in pSM2c cell-derived tumors, and most sh-TM3 cells were in the proliferating phase, as demonstrated by BrdU incorporation (Fig. 7B, far right panels). These data indicate that TM depletion greatly increased DNA synthesis and cell proliferation of basal cell-like keratinoctyes, which might account for a higher tumorigenic ability of TM knockdown HaCaT cells.

FIG. 7.

TM knockdown induces SCC-like tumor. (A) TM-expressing (pSM2c and sh-TM1) and TM knockdown (sh-TM2 and sh-TM3) HaCaT cells were subcutaneously injected into 8-week-old NOD-SCID mice. The mice were sacrificed at 8 weeks after injection, and tumors that grew were dissected and weighed. Increase in tumor outgrowth was observed only in the mice inoculated with TM knockdown HaCaT cells (mean ± SD; n = 10). Triplicate experiments. ***, P < 0.001 versus pSM2c. (B) pSM2c and sh-TM3 cell-derived tumors were dissected and stained with H&E and loricrin and BrdU antibodies. Bar, 50 μm. (C) Expression levels of E-cadherin and Snail in pSM2c and sh-TM3 cell-derived tumors were detected by immunochemistry staining with E-cadherin and Snail antibodies. Bar, 200 μm.

The expression of loricrin, a marker of terminal epidermal differentiation, was significantly reduced and disorganized in the epidermal layers of sh-TM3 cell-derived tumors. Conversely, loricrin was abundantly expressed in the upper spinous layers and the stratum granulosum of pSM2c cell-derived tumors (Fig. 7B, middle panels). We also examined whether EMT-induced alterations of E-cadherin and Snail expression occurred in TM knockdown-derived tumors. We observed that E-cadherin was intensively expressed on the cell surfaces of all epidermal layers in pSM2c cell-derived tumors, whereas markedly reduced expression of E-cadherin was noted in sh-TM3 cell-derived tumors (Fig. 7C, left panels). In contrast, Snail was highly expressed in the nuclei of sh-TM3 cell-derived tumors (Fig. 7C, right panels). Taken together, TM knockdown induced SCC-like tumors in vivo, and this knockdown was accompanied with the reduced expression of E-cadherin at the cell-cell contact and increased Snail expression in the cell nuclei of proliferative epidermal layers.

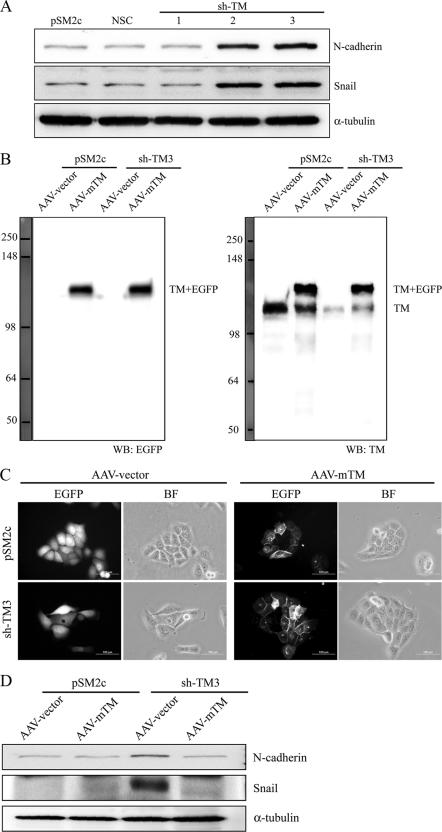

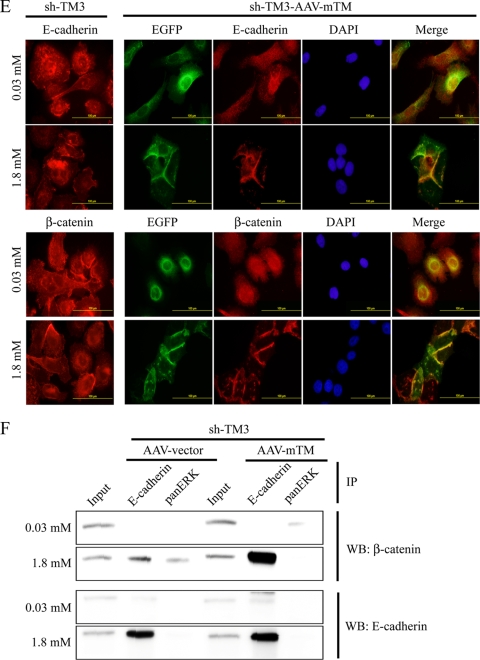

Forced mTM expression suppresses TM knockdown-induced morphology alteration and mesenchymal marker expression.

Since TM knockdown enhanced the nuclear expression of Snail in a xenograft tumor model, TM knockdown may directly affect the gene expression profile to induce EMT. Consistent with this notion, mesenchymal markers like Snail and N-cadherin were upregulated in TM knockdown cell lines (sh-TM2 and sh-TM3) (Fig. 8A). We further transiently transfected TM knockdown sh-TM3 or control pSM2c cells with an mTM-bearing AAV vector which would resist the attack by short hairpin RNA (Fig. 8B). Forced expression of mTM induced TM knockdown cells, but not pSM2c cells, to reassume an epithelium-like morphology (Fig. 8C). Meanwhile, the expression levels of Snail and N-cadherin were reduced in mTM-expressing sh-TM3 cells in comparison with empty AAV vector cells (Fig. 8D). We also found that forced expression of mTM in sh-TM3 cells maintained the colocalization of E-cadherin and β-catenin at cell-cell junctions as shown by immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 8E) and increased the association of E-cadherin with β-catenin as shown by coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 8F) in a calcium switch assay. Based on these results, we conclude that TM functions as a pivotal suppressor of EMT.

FIG. 8.

Forced TM expression suppresses TM knockdown-induced morphology alteration and mesenchymal marker expression. (A) Cell extracts of TM-expressing HaCaT cells (pSM2c, NSC, and sh-TM1) and TM knockdown HaCaT cells (sh-TM2 and sh-TM3) were subjected to Western blotting with anti-N-cadherin and anti-Snail antibodies. α-Tubulin was the loading control. (B) Cell extracts of AAV vector- and AAV-mTM-transfected pSM2c and sh-TM3 cells were subjected to Western blotting with anti-EGFP and anti-TM lectin domain antibodies (D3 clone). (C) Distributions of mTM in pSM2c and sh-TM3 cells were observed by immunofluorescence microscopy. BF, bright field. Bar, 100 μm. (D) Cell extracts of AAV vector- and AAV-mTM-transfected pSM2c cells and sh-TM3 cells were subjected to Western blotting with anti-N-cadherin and anti-Snail antibodies. (E) Immunofluorescent staining of sh-TM3 cells and AAV-mTM-transfected sh-TM3 cells was performed following calcium switch assay. The cells were stained with specific antibodies to E-cadherin or β-catenin and then secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa 546 (red color). EGFP indicates mTM. DAPI is used for nucleic counting. (F) Coimmunoprecipitation of E-cadherin and β-catenin in AAV-mTM-transfected sh-TM3 cells was performed following a calcium switch assay. Anti-E-cadherin antibody was used to capture the complex of E-cadherin and β-catenin. Anti-pan-ERK antibody was used as a nonspecific IgG control. The samples were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-β-catenin and anti-E-cadherin antibodies.

TM directly interacts with ACTN-4.

In order to investigate which domain of TM participated in maintaining cell integrity, we observed whether TM interacted with actinin-4 (ACTN-4), a cytoskeleton-associated protein, by its cytoplasmic domain. We found by confocal microscopy that TM colocalized with ACTN-4 at cell-cell junctions in HaCaT cells (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material), suggesting that TM might interact with ACTN-4. To prove this, we further prepared recombinant proteins, including cytoplasmic domain of TM (TMD5) with glutathione-Sepharose tag (GST) and the spectrin repeats 1 to 4 of ACTN-4 with histidine tag (Nus-act SR1-4) by using an Escherichia coli expression system (see Fig. S2B). We found that TMD5 bound to Nus-act SR1-4 as demonstrated by a GST pulldown assay (see Fig. S2B). Together, we conclude that TM may maintain cell integrity by binding to ACTN-4 through its cytoplasmic domain.

DISCUSSION

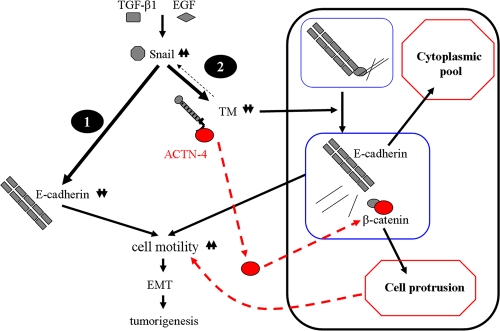

The expression level of TM in the tissues of different carcinomas was inversely correlated with cancer progression and metastasis (16, 24, 31), suggesting that TM may be one of the endogenous antimetastatic factors and that it has diagnostic and prognostic values for the progression of carcinoma. However, the mechanisms involved in TM downregulation and its relationship to tumorigenesis remain mostly unknown. In this report, we observed not only a concordant association of epithelial markers but also an inverse association of Snail with TM expression in a variety of tumor cells and in the in vitro EMT model induced by TGF-β1 and EGF. The inverse expression of TM and Snail could be partly accounted for by a direct Snail binding to the putative binding site (bp −828 to −823 upstream from the transcription start site) in the TM promoter region to repress TM transcription. Moreover, the decrease of TM expression abolishes the trafficking of E-cadherin from the cytoplasmic pool to cell membrane, leading to the decrease in the association of E-cadherin with β-catenin on cell membrane. This downregulation also induced a flat morphology with loose cell junctions, decreased calcium-dependent cell-cell contact, promoted cell motility, and enhanced tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo. We propose two regulatory mechanisms involved in the expression of E-cadherin, which participate in Snail governing EMT (Fig. 9). First, Snail can directly suppress E-cadherin expression at the transcriptional level. Second, Snail can also bind to the TM promoter to downregulate its expression. TM downregulation alters the balance of E-cadherin dynamics and leads to the accumulation of E-cadherin in cytoplasmic pools. The impairment of cell-cell contact and cytoskeletal integrity by the increase of Snail expression is likely through downregulation of not only E-cadherin but also TM. Altogether, TM functions as one key factor for maintaining epithelial morphology.

FIG. 9.

Proposed role of TM in EMT process. Inducers (such as TGF-β1 and EGF) upregulate the expression level of Snail, which leads to EMT directly or indirectly. Snail can either suppress expression of E-cadherin at the transcriptional level (1, direct manner) or inhibit TM promoter activity to dissociate E-cadherin from β-catenin (2, indirect manner), which promotes cell motility. Finally, both direct and indirect mechanisms result in EMT and tumorigenesis. The dashed red line represents the mechanism of TM knockdown-induced enhanced cell motility. The dashed black line shows an interrelationship between Snail and TM.

A negative association of TM and Snail expression was first detected in immortalized HaCaT cells and a variety of carcinoma cell lines. We further confirmed the inverse relation of TM and Snail during the EMT elicited by TGF-β1 and EGF in cultured cells, TM knockdown sh-TM3 cells, and SCC-like tumors derived from sh-TM3 cells in the murine xenograft model. Although we report a novel pathway by which Snail represses TM expression via direct promoter binding during EMT (Fig. 9), we also observed that ectopic TM expression suppressed Snail expression by transfection of shRNA-resistant mTM-EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) fusion-expressing vector (Fig. 8D) and a cell type-specific induction (biphasic activation in HaCaT cells versus sustained activation in A431 cells) of Snail expression during EMT in cultured cells (Fig. 3C). To test whether forced expression of TM reversed the effects elicited by TGF-β1 and EGF, mTM-EGFP-expressing HaCaT cells were cotreated with TGF-β1 and EGF for EMT induction. We found that the cells with forced expression of mTM still maintained epithelium-like morphology even under TGF-β1 and EGF stimulation for 48 h (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Meanwhile, we tested the expression levels of E-cadherin, TM, and Snail in these cells. A decrease of endogenous TM and E-cadherin together with the increase of Snail was observed. Taken together, mTM is able to maintain epithelium-like morphology but fails to reverse the downregulation of E-cadherin and upregulation of Snail elicited by TGF-β1 and EGF. Since mTM cDNA constructed in an AAV vector was driven by a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter which has no Snail binding site, TGF-β1- and EGF-induced Snail could not suppress the expression of ectopic mTM. Therefore, ectopic mTM expression maintains epithelial cell morphology of transfected cells even under TGF-β1 and EGF stimulation. This result is consistent with our previous report that TM functions as a cell-to-cell adhesion molecule even in the absence of E-cadherin (20).

A tumor microenvironment rich in growth factors and cytokines may also play a role in the relation of TM and Snail expression in vivo. More studies are needed to reveal the underlying mechanism responsible for the interrelationship of TM and Snail, particularly how TM expression directly or indirectly suppresses Snail expression. TM promoter methylation at CpG islands has been reported to be one mechanism responsible for TM downregulation in melanoma cells (13). Although we cannot completely rule out this possibility, we were able to demonstrate that TM expression could also be negatively regulated by Snail binding to its promoter region. Snail participates in modulating the expression of many genes associated with tumor progression, including E-cadherin, matrix metalloproteinase 2, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1, tissue plasminogen activator, and ras homolog gene family member A (25). We found that cotreatment of HaCaT and A431 cells with TGF-β1 and EGF induced Snail while reducing the expression of E-cadherin and TM. A putative Snail-binding E-box (−828/−823) in the proximal TM promoter region was confirmed by EMSA, promoter-driven luciferase assay, and ChIP assay (Fig. 3B, C, and D). We demonstrated that the E-box could be a functional element for Snail binding to suppress TM expression. Along the same line, ectopic expression of HA-tagged Snail induced a fibroblast-like phenotype together with the reduction of TM and E-cadherin expression in HaCaT cells (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we are the first to demonstrate that Snail is a key suppressor of TM expression during EMT. Although there are other regulatory factors in the Snail family, including Slug and the E12/47 transcriptional factors (33), more studies are needed to address the involvement of these factors in the modulation of TM expression during EMT. Together, our findings suggest that TM functions as an “initiator” or a “stabilizer” in the formation of a stable complex, including E-cadherin and the associated proteins, at cell-cell junctions to maintain epithelial morphology.

Various adhesion molecules are involved in cell junction formation with E-cadherin under different biological conditions. Loss of these molecules may lead to E-cadherin delocalization from the cell membrane rather than a decrease in expression level of E-cadherin. For instance, Scribble is a conserved polarity protein required for neural differentiation and EMT. Disruption of E-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion by knockdown of Scribble increases cell migration and promotes a more fibroblast-like phenotype (35), which partially mimics EMT in these cells. Similarly, AF6i3 is involved in signaling and organization of cell junctions during embryogenesis. Knockdown of AF6i3 leads to impaired E-cadherin-dependent cell adhesion due to the dissociation of E-cadherin and β-catenin (27). In line with our observations, we found that the protein expression levels of typical adhesion molecules such as E-cadherin and β-catenin were not affected by knockdown of TM expression (Fig. 4A). However, E-cadherin and β-catenin were mostly in the cytoplasm rather than at the cell-cell boundary in TM knockdown HaCaT cells (Fig. 4B). Altogether, TM may contribute to cell-cell adhesion by facilitating the localization of E-cadherin and β-catenin at the cell junctions.

Although initially identified in endothelial cells, TM was also expressed in epithelial keratinocytes but limited to the suprabasal layer (36). The expression of TM was also increased in skin keratinocytes treated with high calcium (1 mM) but not with reduced calcium (29). The expression of TM is thus positively associated with keratinocyte differentiation. Consistent with this notion, TM knockdown promoted the growth in mice of SCC-like tumors, where higher proliferative potential accounted for the larger tumors formed by these cells. Loricrin, a terminally differentiated marker, remained detectable although at a low level with uneven expression in the granular layer around the nest of keratin pearls in the tumors of TM knockdown HaCaT cells (Fig. 7B, middle panels), indicating that this tumor was in a more poorly differentiated state because of the knockdown. The reduced expression of E-cadherin in the TM knockdown-derived tumors further supported the malignant potential of the tumors. The tumor-promoting effect of TM knockdown observed in murine tumorigenesis was consistent with the poor prognosis of cancer patients with reduced TM expression (15, 21, 24, 31). Taken together, our study further supports a tumor-suppressing role of TM.

There are two approaches commonly used to address potential off-target effects caused by the use of shRNA. First, more than one shRNA targeting different regions of the same target gene could be used to examine if either one has the same knockdown effect. Second, forced expression of a cDNA of interest without the shRNA targeting sites would prevent the cDNA from being attacked by the shRNA in the same cells. In this report, we overexpressed the mTM lack-of-recognition sequence by TM1.9 (Table 1) in the cells expressing this shRNA to examine any off-target effects. As predicted, only the expression of endogenous TM rather than mTM fusion protein was decreased by TM1.9 (Fig. 8B, right panel), supporting a TM-specific shRNA used in this study. Moreover, ectopic expression of mTM reversed TM knockdown-induced alteration of cell morphology (Fig. 8C) and maintained the colocalization of E-cadherin and β-catenin at cell junctions in a calcium-dependent manner (Fig. 8E and F). Since we successfully reversed the TM knockdown effects by introduction of mTM expression, the observed phenotypic change induced by TM knockdown was unlikely due to off-target effects.

ACTN-4, a scaffold protein connecting the cytoskeleton to cell junctions, is a biomarker for cancer invasion and metastasis in several cancer types (7, 19, 23, 32, 46). During the process of tumor cell migration, the expression of ACTN-4 is increased and mainly localized at the leading edge of migrating cells (19). Silencing the expression of ACTN-4 restores E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contact and reduces the cell motility of pancreatic cancer cells (23). Knockdown of E-cadherin librates β-catenin from cell membrane, and the free β-catenin together with ACTN-4 is recruited into cell protrusion in colorectal cancer cells (17). In our unpublished data, we found that overexpression of TM in A2058 cells upregulated the expression level of ACTN-4 and increased its association with TM as shown by using confocal microscopy and immunoprecipitation. Moreover, this association in HaCaT cells was highly concentrated at cell-cell contact (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). GST pulldown assay further confirmed that the cytoplasmic tail of TM is required for its interaction with ACTN-4 (see Fig. S2B and C). Altogether, TM holds E-cadherin in check at the cell-cell junction and maintains epithelial morphology. The loss of TM expression not only induced the mesenchymal phenotype but also increased cell motility partly via the accumulation of E-cadherin in the cytoplasmic pool and dissociation of TM from ACTN-4, thereby increasing the pool of the free ACTN-4 and β-catenin to cell protrusions for cell migration (Fig. 9).

In conclusion, the expression of TM and Snail in various human tumor cells and during EMT is not only inversely correlated but also interregulated. Snail is a novel transcriptional repressor of TM via a direct binding to the Snail-responsive E-box in the TM proximal promoter. TM downregulation either by knockdown or by induction by EMT led to a dissociation of E-cadherin with β-catenin at cell-cell junctions. Therefore, the expression level of TM may function as a gatekeeper to prevent epithelial cells from undergoing EMT and may be used as a prognostic or therapeutic target for cancer prognosis or treatment. Our studies provide another biological function of TM besides its role in cell adhesion, angiogenesis, and anti-inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Council, Executive Yuan, Taipei, Taiwan, grants NSC 97-2752-B-006-003-PAE, NSC 97-2752-B-006-004-PAE, and NSC 97-2752-B-006-005-PAE.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbour, W., S. Saika, T. Miyamoto, K. Ohkawa, H. Utsunomiya, and Y. Ohnishi. 2004. Expression patterns of beta1-related alpha integrin subunits in murine lens during embryonic development and wound healing. Curr. Eye Res. 29:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batlle, E., E. Sancho, C. Franci, D. Dominguez, M. Monfar, J. Baulida, and A. Garcia De Herreros. 2000. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:84-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker, K. F., E. Rosivatz, K. Blechschmidt, E. Kremmer, M. Sarbia, and H. Hofler. 2007. Analysis of the E-cadherin repressor Snail in primary human cancers. Cells Tissues Organs 185:204-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolos, V., H. Peinado, M. A. Perez-Moreno, M. F. Fraga, M. Esteller, and A. Cano. 2003. The transcription factor Slug represses E-cadherin expression and induces epithelial to mesenchymal transitions: a comparison with Snail and E47 repressors. J. Cell Sci. 116:499-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boukamp, P., R. T. Petrussevska, D. Breitkreutz, J. Hornung, A. Markham, and N. E. Fusenig. 1988. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J. Cell Biol. 106:761-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bracke, M. E., H. Depypere, C. Labit, V. Van Marck, K. Vennekens, S. J. Vermeulen, I. Maelfait, J. Philippe, R. Serreyn, and M. M. Mareel. 1997. Functional downregulation of the E-cadherin/catenin complex leads to loss of contact inhibition of motility and of mitochondrial activity, but not of growth in confluent epithelial cell cultures. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 74:342-349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broderick, M. J., and S. J. Winder. 2005. Spectrin, alpha-actinin, and dystrophin. Adv. Protein Chem. 70:203-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, K. A., M. E. Aakre, A. E. Gorska, J. O. Price, S. E. Eltom, J. A. Pietenpol, and H. L. Moses. 2004. Induction by transforming growth factor-beta1 of epithelial to mesenchymal transition is a rare event in vitro. Breast Cancer Res. 6:R215-R231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cano, A., M. A. Perez-Moreno, I. Rodrigo, A. Locascio, M. J. Blanco, M. G. del Barrio, F. Portillo, and M. A. Nieto. 2000. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:76-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conacci-Sorrell, M., J. Zhurinsky, and A. Ben-Ze'ev. 2002. The cadherin-catenin adhesion system in signaling and cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 109:987-991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies, M., M. Robinson, E. Smith, S. Huntley, S. Prime, and I. Paterson. 2005. Induction of an epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human immortal and malignant keratinocytes by TGF-beta1 involves MAPK, Smad and AP-1 signalling pathways. J. Cell. Biochem. 95:918-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esmon, C. T. 1987. The regulation of natural anticoagulant pathways. Science 235:1348-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furuta, J., A. Kaneda, Y. Umebayashi, F. Otsuka, T. Sugimura, and T. Ushijima. 2005. Silencing of the thrombomodulin gene in human malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 15:15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grunert, S., M. Jechlinger, and H. Beug. 2003. Diverse cellular and molecular mechanisms contribute to epithelial plasticity and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:657-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanly, A. M., A. Hayanga, D. C. Winter, and D. J. Bouchier-Hayes. 2005. Thrombomodulin: tumour biology and prognostic implications. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 31:217-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanly, A. M., M. Redmond, D. C. Winter, S. Brophy, J. M. Deasy, D. J. Bouchier-Hayes, and E. W. Kay. 2006. Thrombomodulin expression in colorectal carcinoma is protective and correlates with survival. Br. J. Cancer 94:1320-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashida, Y., K. Honda, M. Idogawa, Y. Ino, M. Ono, A. Tsuchida, T. Aoki, S. Hirohashi, and T. Yamada. 2005. E-cadherin regulates the association between beta-catenin and actinin-4. Cancer Res. 65:8836-8845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Healy, A. M., H. B. Rayburn, R. D. Rosenberg, and H. Weiler. 1995. Absence of the blood-clotting regulator thrombomodulin causes embryonic lethality in mice before development of a functional cardiovascular system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:850-854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honda, K., T. Yamada, R. Endo, Y. Ino, M. Gotoh, H. Tsuda, Y. Yamada, H. Chiba, and S. Hirohashi. 1998. Actinin-4, a novel actin-bundling protein associated with cell motility and cancer invasion. J. Cell Biol. 140:1383-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, H. C., G. Y. Shi, S. J. Jiang, C. S. Shi, C. M. Wu, H. Y. Yang, and H. L. Wu. 2003. Thrombomodulin-mediated cell adhesion: involvement of its lectin-like domain. J. Biol. Chem. 278:46750-46759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iino, S., K. Abeyama, K. Kawahara, M. Yamakuchi, T. Hashiguchi, S. Matsukita, S. Yonezawa, S. Taniguchi, M. Nakata, S. Takao, T. Aikou, and I. Maruyama. 2004. The antimetastatic role of thrombomodulin expression in islet cell-derived tumors and its diagnostic value. Clin. Cancer Res. 10:6179-6188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang, Y., and J. Massague. 2004. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: twist in development and metastasis. Cell 118:277-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kikuchi, S., K. Honda, H. Tsuda, N. Hiraoka, I. Imoto, T. Kosuge, T. Umaki, K. Onozato, M. Shitashige, U. Yamaguchi, M. Ono, A. Tsuchida, T. Aoki, J. Inazawa, S. Hirohashi, and T. Yamada. 2008. Expression and gene amplification of actinin-4 in invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas. Clin. Cancer Res. 14:5348-5356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim, S. J., E. Shiba, H. Ishii, T. Inoue, T. Taguchi, Y. Tanji, Y. Kimoto, M. Izukura, and S. Takai. 1997. Thrombomodulin is a new biological and prognostic marker for breast cancer: an immunohistochemical study. Anticancer Res. 17:2319-2323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuphal, S., H. G. Palm, I. Poser, and A. K. Bosserhoff. 2005. Snail-regulated genes in malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 15:305-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lioni, M., P. Brafford, C. Andl, A. Rustgi, W. El-Deiry, M. Herlyn, and K. S. Smalley. 2007. Dysregulation of claudin-7 leads to loss of E-cadherin expression and the increased invasion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Am. J. Pathol. 170:709-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorger, M., and K. Moelling. 2006. Regulation of epithelial wound closure and intercellular adhesion by interaction of AF6 with actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Sci. 119:3385-3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandal, M., J. N. Myers, S. M. Lippman, F. M. Johnson, M. D. Williams, S. Rayala, K. Ohshiro, D. I. Rosenthal, R. S. Weber, G. E. Gallick, and A. K. El-Naggar. 2008. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in head and neck squamous carcinoma: association of Src activation with E-cadherin down-regulation, vimentin expression, and aggressive tumor features. Cancer 112:2088-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizutani, H., T. Hayashi, N. Nouchi, S. Ohyanagi, K. Hashimoto, M. Shimizu, and K. Suzuki. 1994. Functional and immunoreactive thrombomodulin expressed by keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 103:825-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navarro, P., M. Gomez, A. Pizarro, C. Gamallo, M. Quintanilla, and A. Cano. 1991. A role for the E-cadherin cell-cell adhesion molecule during tumor progression of mouse epidermal carcinogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 115:517-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogawa, H., S. Yonezawa, I. Maruyama, Y. Matsushita, Y. Tezuka, H. Toyoyama, M. Yanagi, H. Matsumoto, H. Nishijima, T. Shimotakahara, T. Aikou, and E. Sato. 2000. Expression of thrombomodulin in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung: its relationship to lymph node metastasis and prognosis of the patients. Cancer Lett. 149:95-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otey, C. A., and O. Carpen. 2004. Alpha-actinin revisited: a fresh look at an old player. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 58:104-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peinado, H., D. Olmeda, and A. Cano. 2007. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat. Rev. Cancer 7:415-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pignatelli, M., T. W. Ansari, P. Gunter, D. Liu, S. Hirano, M. Takeichi, G. Kloppel, and N. R. Lemoine. 1994. Loss of membranous E-cadherin expression in pancreatic cancer: correlation with lymph node metastasis, high grade, and advanced stage. J. Pathol. 174:243-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin, Y., C. Capaldo, B. M. Gumbiner, and I. G. Macara. 2005. The mammalian Scribble polarity protein regulates epithelial cell adhesion and migration through E-cadherin. J. Cell Biol. 171:1061-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raife, T. J., D. J. Lager, K. C. Madison, W. W. Piette, E. J. Howard, M. T. Sturm, Y. Chen, and S. R. Lentz. 1994. Thrombomodulin expression by human keratinocytes. Induction of cofactor activity during epidermal differentiation. J. Clin. Invest. 93:1846-1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts, A. B., and L. M. Wakefield. 2003. The two faces of transforming growth factor beta in carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:8621-8623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi, C. S., G. Y. Shi, Y. S. Chang, H. S. Han, C. H. Kuo, C. Liu, H. C. Huang, Y. J. Chang, P. S. Chen, and H. L. Wu. 2005. Evidence of human thrombomodulin domain as a novel angiogenic factor. Circulation 111:1627-1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi, C. S., G. Y. Shi, S. M. Hsiao, Y. C. Kao, K. L. Kuo, C. Y. Ma, C. H. Kuo, B. I. Chang, C. F. Chang, C. H. Lin, C. H. Wong, and H. L. Wu. 2008. Lectin-like domain of thrombomodulin binds to its specific ligand Lewis Y antigen and neutralizes lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response. Blood 112:3661-3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiozaki, H., T. Kadowaki, Y. Doki, M. Inoue, S. Tamura, H. Oka, T. Iwazawa, S. Matsui, K. Shimaya, M. Takeichi, et al. 1995. Effect of epidermal growth factor on cadherin-mediated adhesion in a human oesophageal cancer cell line. Br. J. Cancer 71:250-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiozaki, H., H. Tahara, H. Oka, M. Miyata, K. Kobayashi, S. Tamura, K. Iihara, Y. Doki, S. Hirano, M. Takeichi, et al. 1991. Expression of immunoreactive E-cadherin adhesion molecules in human cancers. Am. J. Pathol. 139:17-23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shook, D., and R. Keller. 2003. Mechanisms, mechanics and function of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in early development. Mech. Dev. 120:1351-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki, K., H. Kusumoto, Y. Deyashiki, J. Nishioka, I. Maruyama, M. Zushi, S. Kawahara, G. Honda, S. Yamamoto, and S. Horiguchi. 1987. Structure and expression of human thrombomodulin, a thrombin receptor on endothelium acting as a cofactor for protein C activation. EMBO J. 6:1891-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vega, S., A. V. Morales, O. H. Ocana, F. Valdes, I. Fabregat, and M. A. Nieto. 2004. Snail blocks the cell cycle and confers resistance to cell death. Genes Dev. 18:1131-1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watabe, M., K. Matsumoto, T. Nakamura, and M. Takeichi. 1993. Effect of hepatocyte growth factor on cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. Cell Struct. Funct. 18:117-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamagata, N., Y. Shyr, K. Yanagisawa, M. Edgerton, T. P. Dang, A. Gonzalez, S. Nadaf, P. Larsen, J. R. Roberts, J. C. Nesbitt, R. Jensen, S. Levy, J. H. Moore, J. D. Minna, and D. P. Carbone. 2003. A training-testing approach to the molecular classification of resected non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 9:4695-4704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan, Z., S. Wong, A. Borrelli, and M. A. Chung. 2007. Down-regulation of MUC1 in cancer cells inhibits cell migration by promoting E-cadherin/catenin complex formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 362:740-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.