Abstract

Interleukin-2 (IL-2) has been implicated as being necessary for the optimal formation of primary CD8+ T cell responses against various pathogens. Here we have examined the role that IL-2 signaling plays in several aspects of a CD8+ T cell response against murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68). Exposure to MHV-68 causes a persistent infection, along with infectious mononucleosis, providing a model for studying these processes in mice. Our study indicates that CD25 is necessary for optimal expansion of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response but not for the long-term memory response. Contrastingly, IL-2 signaling through CD25 is absolutely required for CD8+ T cell mononucleosis.

Members of the gammaherpesvirus family are associated with significant diseases, such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma, lymphoid malignancies, and infectious mononucleosis (16). Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68) is a γ2-herpesvirus related to the human pathogens Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Kaposi's sarcoma virus (19, 21). Intranasal (i.n.) infection of mice with MHV-68 results in acute infection of the lung epithelium, which is eventually controlled; however, the virus also establishes a latent infection in B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages that is maintained throughout the life of the host (8, 9). Infection with MHV-68 generates a broad array of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells that can control the virus without eliminating persistent infection (5, 12, 13). Additionally, CD4+ T cells and neutralizing antibodies are thought to be critical for the prevention of virus reactivation (3, 6).

A major complication of EBV infection is infectious mononucleosis (16), which occurs when infection is delayed until puberty. Signs of disease include dramatic lymph node enlargement and the presence of large numbers of activated CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood. Similarly to EBV infection, MHV-68 induces a polyclonal activation of B cells upon establishment of latency. Concurrently, a CD8+ T cell-dominated lymphocytosis of the peripheral blood occurs, as seen with EBV. However, there are distinct differences between the two types of infectious mononucleosis. CD8+ T cell lymphocytosis seen with EBV consists of a broad array of T cell receptor specificities, a large proportion of which are specific for EBV epitopes. In contrast, MHV-68-induced mononucleosis is dominated by oligoclonal Vβ4+ CD8+ T cells that are not reactive to MHV-68 epitopes. With MHV-68, the expansion of this population is dramatic, with levels reaching upwards of 60% of the peripheral blood CD8+ T cell population (20). This occurs in different mouse strains, across at least five different major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I haplotypes. However, it is important to note that infection of wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) does not induce splenomegaly, as seen with laboratory strains of mice, indicating a potential lack of Vβ4 expansion that may be species related (14). Interestingly, evidence suggests that Vβ4+ CD8+ T cell expansion does not require classical MHC class Ia antigen presentation (4). Recent studies instead implicate a secreted viral protein, M1, capable of stimulating the Vβ4+ T cell population in a novel manner, and the authors propose a role for Vβ4+ T cells in control of MHV-68 infection (7).

We and others have recently shown that IL-2 signaling during the early stages of a response to acute viral and bacterial pathogens is required for optimal expansion and differentiation of CD8+ T cells (15, 17, 18). However, reports with other viruses have shown IL-2-independent primary CD8+ T cell responses (1, 22). Therefore, we wished to determine whether IL-2 signals are necessary for the expansion, maintenance, and/or recall of CD8+ T cell responses during murine gammaherpesvirus infection.

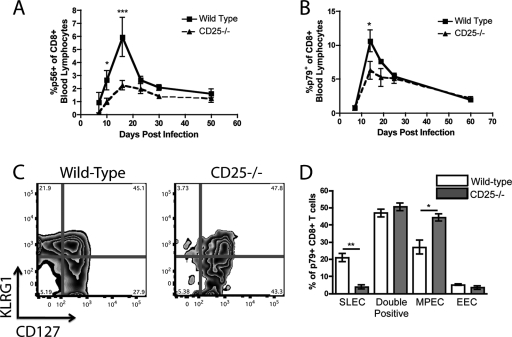

We generated chimeric mice through lethal irradiation of C57BL/6 mice followed by adoptive transfer of mixed bone marrow from C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) and CD25−/− donors, as previously described (17). Following previous described protocols, mice were given bone marrow in a 2:1 ratio of CD25−/−/WT to generate equally proportioned congenic populations in recipient mice (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (1, 17). The resultant mice contained CD8+ T cells of both WT and CD25−/− origin, which could be distinguished by congenic markers. Chimeric mice were infected intranasally with 400 PFU of MHV-68, and the kinetics of the CD8+ T cell response were followed by antibody and tetramer staining of peripheral blood for CD8+ T cells specific for the epitopes ORF6487 (p56) and ORF61524 (p79), as previously described (13). While antigen-specific CD25−/− CD8+ T cells were initially able to proliferate in response to infection, the peak response was significantly lower than that of the wild-type cells (Fig. 1 A and B). This indicates that while CD25 is dispensable for early activation of CD8+ T cells, IL-2 signaling is required for full expansion of the antigen-specific response to MHV-68. Despite this deficit in the acute antiviral response, the resultant memory populations were not statistically different between the groups (Fig. 1A and B). In our previous report, CD25−/− CD8+ T cells were unable to fully differentiate into short-lived effector cells (SLECs), defined as KLRG1high CD127low (17). To determine if MHV-68-specific responses were also unable to fully differentiate, we infected chimeric mice and stained p79+ CD8+ T cells for the cell surface markers KLRG1 and CD127. At the peak of the response (14 days postinfection [p.i.]), p79+ WT cells had differentiated into SLEC (KLRG1high CD127low), memory precursor (MPEC) (KLRG1low CD127high), and doubly positive populations. However, the p79+ CD25−/− cells failed to form the SLEC population and instead had a corresponding increase in the MPEC population, indicating that CD25 is necessary for full effector differentiation of gammaherpesvirus-specific CD8+ T cell responses (Fig. 1C and D).

FIG. 1.

IL-2 signals are necessary for the optimal expansion of MHV-68-specific CD8+ T cells. WT/CD25−/− chimeric mice were infected with MHV-68 intranasally and bled at set time points. The antigen-specific responses against two dominant epitopes, p79 (A) and p56 (B), were determined via tetramer staining of peripheral blood. p79-specific CD8+ T cells from the WT and CD25−/− populations were stained at the peak of the response (day 14 p.i.) for KLRG1 and CD127 to determine their ability to differentiate into short-lived and memory precursor effector cells (C and D). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Error bars represent standard deviations from the means. Four mice were used per group, and data are representative of at least two experiments.

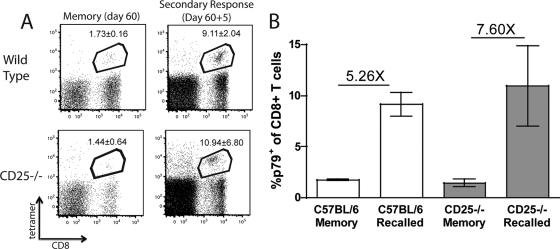

To determine whether antigen-specific CD25−/− CD8+ T cells were capable of optimally responding to a secondary challenge, we infected chimeric mice with MHV-68 and waited 60 days before challenging with recombinant vaccinia virus (rVV) expressing the ORF61524 epitope (2 × 106 PFU, intraperitoneal). It is necessary to use a heterologous virus to induce a recall CD8+ T cell response since MHV-68 generates a robust neutralizing antibody response, preventing secondary infection. Previous studies with rVV indicate that the recall response of MHV-68-specific CD8+ T cells is antigen dependent, since administration of rVV expressing an irrelevant epitope had no effect upon the MHV-68-specific populations (2). WT and CD25−/− cells were able to respond to the secondary challenge with similar kinetics (Fig. 2 A and B), indicating that MHV-68 memory CD8+ T cells are capable of a generating a recall response in the absence of IL-2 signaling. These data, together with our previous report (17), show that the dependence on CD25 for formation of the SLEC population is conserved between both persistent and acute virus infections.

FIG. 2.

CD25−/− CD8+ T cells can respond to secondary challenge. WT/CD25−/− chimeric mice were infected with MHV-68 i.n. After 60 days, the percentage of peripheral blood CD8+ T cells specific for p79 was determined. Mice were then challenged with rVV p79, and the p79+ CD8+ population was determined 5 days postchallenge (A). The numbers in the box represent the averages ± standard deviations. The average fold increase was calculated to determine the ability of WT and CD25−/− CD8+ T cells to respond to a secondary challenge (B). Error bars represent standard deviations from the means. Four mice were used per group, and data are representative of at least two experiments.

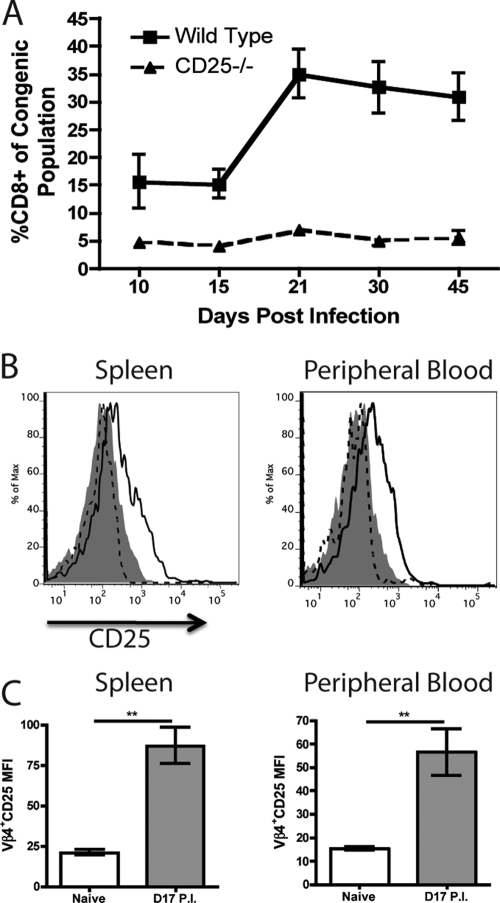

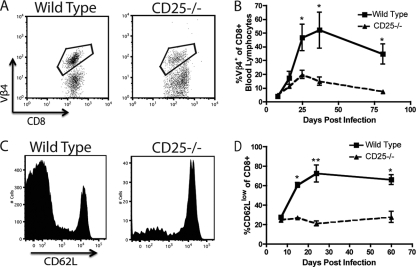

WT CD8+ T cells underwent a dramatic expansion between days 15 and 21 p.i. (Fig. 3A), consistent with infectious mononucleosis (10). Interestingly, we did not observe a similar expansion of CD25−/− CD8+ T cells, indicating a role for IL-2 signaling in the expansion of CD8+ T cells during mononucleosis (Fig. 3A). Since mononucleosis is dominated by Vβ4+ CD8+ T cells, we analyzed these T cells from both naive and infected mice (17 days p.i.) for expression of CD25 by flow cytometry. While Vβ4+ CD8+ T cells from the spleen and peripheral blood of naive mice did not express detectable levels of CD25, mice infected with MHV-68 expressed intermediate levels of CD25 during the time period when dramatic expansion of Vβ4+ T cells occurs (Fig. 3B and C). Consistent with a role for IL-2 signaling in Vβ4 expansion, we observed a severe deficit in expansion in the CD25−/− population of chimeric mice, since the percentage of WT Vβ4+ cells increased dramatically between days 14 and 36 p.i., accompanied by only a small expansion of the CD25−/− Vβ4+ population over the same period (Fig. 4 A and B).

FIG. 3.

Vβ4+ CD8+ T cells express CD25 upon infection with MHV-68. WT/CD25−/− chimeric mice were infected with MHV-68 i.n., and the percentage of peripheral blood cells that were CD8+ was determined over time for each congenic population (A). Vβ4+ CD8+ T cells from naive and MHV-68-infected mice (day 17 p.i.) were analyzed for expression of CD25 (B and C). Isotype control, filled histogram; naive mice, dashed line; infected mice, solid line (**, P < 0.01). Error bars represent standard deviations from the means. Four mice were used per group, and data are representative of at least two experiments.

FIG. 4.

CD8+ T cell-based infectious mononucleosis does not occur in the absence of IL-2 signaling in MHV-68-infected mice. WT/CD25−/− chimeric mice were infected with MHV-68 i.n., and the percentage of Vβ4+ CD8+ T cells was determined over time for each congenic population. Representative plots from day 36 p.i. (A) or the averages over time (B) are shown. WT and CD25−/− CD8+ T cells from chimeric mice were analyzed for expression of CD62L over time. Representative plots from day 24 p.i. (C) or the averages over time (D) are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). Error bars represent standard deviations from the means. Four mice were used per group, and data are representative of at least two experiments.

During infectious mononucleosis, CD8+ T cells are in a highly activated state and thus express low levels of CD62L (20). Therefore, we analyzed CD8+ T cells from chimeric mice for expression of CD62L. After MHV-68 infection, the majority of WT CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood were CD62Llow, as previously reported (Fig. 4C and D) (20). Interestingly, CD25−/− CD8+ T cells failed to develop this dominant CD62Llow population, indicating that CD25 is necessary for the activation of the CD8+ T cell compartment in addition to cell expansion during mononucleosis (Fig. 4C and D). When we analyzed the Vβ4+ CD8+ T cell compartment, we observed that WT cells downregulated expression of CD62L. While Vβ4+ cells from the CD25−/− compartment also decreased expression of CD62L, they did so to a lesser extent both as a percentage and on a per-cell basis (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

In these studies, we have shown that signaling through CD25 is necessary for the generation of an optimal primary CD8+ T cell response against a gammaherpesvirus, since virus-specific CD8+ T cells were unable to expand as robustly as WT cells and did not fully differentiate into short-lived effector cells. These observations are consistent with previous results from our lab and findings of others using a variety of acute infection models (17, 18). However, not all persistent infections appear to require CD25, since the m45-specific response to murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection occurs normally in the absence of IL-2 signals (1). What allows for some responses to be independent of IL-2 remains unknown. Potential explanations could involve differences in tropism, the route of infection, or the amount of proinflammatory cytokines induced by each infection. Despite the dependence on CD25 for the short-term effector response, the memory CD8+ T cell response remained intact in the absence of IL-2 signaling. In contrast, Vβ4 expansion and mononucleosis never attained normal levels. Unlike the antigen-specific response, which relies upon peptide/MHC interactions for induction, mononucleosis does not rely upon conventional antigen presentation (4). Instead, the M1 protein of MHV-68, expressed during the establishment and expansion of latency in the spleen, appears to drive Vβ4 expansion (7). Interestingly, our evidence shows that both antigen-dependent and -independent CD8+ T cell expansion require CD25. Antigen-specific T cells also undergo an apoptotic contraction phase, followed by a lower frequency of cells surviving as relatively quiescent memory cells. In contrast, during mononucleosis caused by MHV-68, CD8+ T cells remain in an activated state and do not undergo a marked contraction, providing a potential explanation as to why the WT and CD25−/− Vβ4 populations continue to differ in both number and phenotype later in the response.

Earlier studies have also identified CD4+ T cells as being critical for the development of MHV-68-induced infectious mononucleosis (11, 20). We have previously shown that CD4+ T cell help was critical for robust expression of CD25 on activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Interestingly, when we measured CD25 expression on Vβ4+ cells from mice lacking CD4+ T cells, we saw a moderate decrease in the level of CD25 expressed (data not shown), indicating one potential reason why CD4-deficient mice do not experience infectious mononucleosis. However, it is likely that other factors involving CD4+ T cells and activation of B cells are also involved (10).

In conclusion, the significance of these studies is twofold. First, they shed light on the requirements for MHV-68-induced mononucleosis. Second, our data illustrate that CD25 is required for both antigen-specific and non-antigen-specific activation of CD8+ T cell responses, while being dispensable for memory cell formation. This knowledge may be useful in developing new T cell-based immune therapies to enhance control of persistent gammaherpesvirus infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided in part by National Institutes of Health grants AI069943, CA103642, and T32AI07363.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachmann, M. F., P. Wolint, S. Walton, K. Schwarz, and A. Oxenius. 2007. Differential role of IL-2R signaling for CD8+ T cell responses in acute and chronic viral infections. Eur. J. Immunol. 37:1502-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belz, G. T., P. G. Stevenson, M. R. Castrucci, J. D. Altman, and P. C. Doherty. 2000. Postexposure vaccination massively increases the prevalence of gamma-herpesvirus-specific CD8+ T cells but confers minimal survival advantage on CD4-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:2725-2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardin, R. D., J. W. Brooks, S. R. Sarawar, and P. C. Doherty. 1996. Progressive loss of CD8+ T cell-mediated control of a gamma-herpesvirus in the absence of CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 184:863-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coppola, M. A., E. Flano, P. Nguyen, C. L. Hardy, R. D. Cardin, N. Shastri, D. L. Woodland, and M. A. Blackman. 1999. Apparent MHC-independent stimulation of CD8+ T cells in vivo during latent murine gammaherpesvirus infection. J. Immunol. 163:1481-1489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cush, S. S., K. M. Anderson, D. H. Ravneberg, J. L. Weslow-Schmidt, and E. Flano. 2007. Memory generation and maintenance of CD8+ T cell function during viral persistence. J. Immunol. 179:141-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doherty, P. C., D. J. Topham, R. A. Tripp, R. D. Cardin, J. W. Brooks, and P. G. Stevenson. 1997. Effector CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell mechanisms in the control of respiratory virus infections. Immunol. Rev. 159:105-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans, A. G., J. M. Moser, L. T. Krug, V. Pozharskaya, A. L. Mora, and S. H. Speck. 2008. A gammaherpesvirus-secreted activator of Vbeta4+ CD8+ T cells regulates chronic infection and immunopathology. J. Exp. Med. 205:669-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flano, E., S. M. Husain, J. T. Sample, D. L. Woodland, and M. A. Blackman. 2000. Latent murine gamma-herpesvirus infection is established in activated B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages. J. Immunol. 165:1074-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flano, E., Q. Jia, J. Moore, D. L. Woodland, R. Sun, and M. A. Blackman. 2005. Early establishment of gamma-herpesvirus latency: implications for immune control. J. Immunol. 174:4972-4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flano, E., D. L. Woodland, and M. A. Blackman. 2002. A mouse model for infectious mononucleosis. Immunol. Res. 25:201-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flano, E., D. L. Woodland, and M. A. Blackman. 1999. Requirement for CD4+ T cells in V beta 4+CD8+ T cell activation associated with latent murine gammaherpesvirus infection. J. Immunol. 163:3403-3408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freeman, M. L., K. G. Lanzer, T. Cookenham, B. Peters, J. Sidney, T. T. Wu, R. Sun, D. L. Woodland, A. Sette, and M. A. Blackman. 2010. Two kinetic patterns of epitope-specific CD8 T-cell responses following murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection. J. Virol. 84:2881-2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuse, S., J. J. Obar, S. Bellfy, E. K. Leung, W. Zhang, and E. J. Usherwood. 2006. CD80 and CD86 control antiviral CD8+ T-cell function and immune surveillance of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 80:9159-9170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes, D. J., A. Kipar, J. T. Sample, and J. P. Stewart. 2010. Pathogenesis of a model gammaherpesvirus in a natural host. J. Virol. 84:3949-3961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalia, V., S. Sarkar, S. Subramaniam, W. N. Haining, K. A. Smith, and R. Ahmed. 2010. Prolonged interleukin-2Ralpha expression on virus-specific CD8+ T cells favors terminal-effector differentiation in vivo. Immunity 32:91-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kutok, J. L., and F. Wang. 2006. Spectrum of Epstein-Barr virus-associated diseases. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 1:375-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obar, J. J., M. J. Molloy, E. R. Jellison, T. A. Stoklasek, W. Zhang, E. J. Usherwood, and L. Lefrancois. 2010. CD4+ T cell regulation of CD25 expression controls development of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells in primary and secondary responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:193-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pipkin, M. E., J. A. Sacks, F. Cruz-Guilloty, M. G. Lichtenheld, M. J. Bevan, and A. Rao. 2010. Interleukin-2 and inflammation induce distinct transcriptional programs that promote the differentiation of effector cytolytic T cells. Immunity 32:79-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simas, J. P., and S. Efstathiou. 1998. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68: a model for the study of gammaherpesvirus pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 6:276-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tripp, R. A., A. M. Hamilton-Easton, R. D. Cardin, P. Nguyen, F. G. Behm, D. L. Woodland, P. C. Doherty, and M. A. Blackman. 1997. Pathogenesis of an infectious mononucleosis-like disease induced by a murine gamma-herpesvirus: role for a viral superantigen? J. Exp. Med. 185:1641-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Virgin, H. W., IV, P. Latreille, P. Wamsley, K. Hallsworth, K. E. Weck, A. J. Dal Canto, and S. H. Speck. 1997. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 71:5894-5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams, M. A., A. J. Tyznik, and M. J. Bevan. 2006. Interleukin-2 signals during priming are required for secondary expansion of CD8+ memory T cells. Nature 441:890-893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.