Abstract

Because they are obligate intracellular parasites, all viruses are exclusively and intimately dependent upon host cells for replication. Viruses, in turn, induce profound changes within cells, including apoptosis, morphological changes, and activation of signaling pathways. Many of these alterations have been analyzed by gene arrays, which measure the cellular “transcriptome.” Until recently, it has not been possible to extend comparable types of studies to globally examine all the host cellular proteins, which are the actual effector molecules. We have used stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC), combined with high-throughput two-dimensional (2-D) high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)/mass spectrometry, to determine quantitative differences in host proteins after infection of human lung A549 cells with human influenza virus A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) for 24 h. Of the 4,689 identified and measured cytosolic protein pairs, 127 were significantly upregulated at >95% confidence, 153 were significantly downregulated at >95% confidence, and a total of 87 proteins were upregulated or downregulated more than 5-fold at >99% confidence. Gene ontology and pathway analyses indicated differentially regulated proteins and included those involved in host cell immunity and antigen presentation, cell adhesion, metabolism, protein function, signal transduction, and transcription pathways.

Influenza A virus (FLUAV), a member of the family Orthomyxoviridae, is a small enveloped virus with a genome consisting of 8 segments of negative-sense single-stranded RNA that encodes for 10 to 11 proteins depending on the strain (56). The segmented genome and highly error-prone viral replication lead to enormous genetic plasticity, mediated by nucleotide or genome segment exchange, termed genetic drift or genetic shift, respectively. Genomic changes control the differences in virulence and host range seen among FLUAV isolates. FLUAVs are serologically categorized by 2 surface proteins: hemagglutinin (HA), of which there are currently 16 types (H1 to H16), and neuraminidase (NA), of which there are currently 9 types (N1 to N9) (56). Virtually every possible H-N combination has been found in water fowl (2, 46), the generally accepted reservoir, but only a few H-N types have circulated in humans: H1N1 (1918 “Spanish Flu” and the current pandemic H1N1 2009 strains), H2N2, and H3N2. A number of antiviral strategies, including vaccines and small molecule inhibitors, have been developed to combat this virus, but its genetic plasticity often leads to resistance to virus-targeted antiviral strategies. Because of its small genome, the virus, like other viruses, is an obligate parasite and must make extensive use of host cell machinery. Thus, an alternate antiviral strategy could be to better understand the critical host factors that are influenced and required by the virus for its efficient propagation.

While a cell's genome generally remains relatively constant (except for certain epigenetic events; see references 28 and 33 for reviews), the cell's proteome (the total protein repertoire, including how any given protein may be cotranslationally or posttranslationally modified) varies greatly due to its biochemical interactions with the genome, as well as the cell's interactions with the environment. A cell's protein expression is dependent on the location of the cell, different stages of its life cycle, and different environmental conditions. In the case of viruses, which require the host cell's machinery and metabolism to replicate, the cell's proteome also reflects the specific alterations of the pathways induced by virus infection.

Previous analyses of how cells respond to influenza virus infection have used microarray technologies which measure the cellular “transcriptome” (for examples, see references 6, 30, and 45). However, there frequently is little concordance between microarray and protein data (6, 52, 71), partly because mRNA levels cannot provide complete information about levels of protein synthesis or extents of posttranslational modifications. Thus, proteomic analyses have also been employed to better understand host alterations to virus infection. Vester et al. used two-dimensional difference in gel electrophoresis (2-D DIGE) and identified 8 significantly altered host proteins in influenza virus A/PR/8/34 (H1N1)-infected MDCK and human A549 cells (72), and Liu and colleagues used a similar approach to identify about 25 significantly altered host proteins in avian influenza A/Hong Kong/108/2003 (H9N2)-infected human gastric carcinoma cells (48).

There have been a number of significant improvements in quantitative proteomic analyses, particularly in areas of nongel-based studies, such as isotope-coded affinity tags (ICAT) (see references 11, 35, and 39 for some examples), isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) (see references 12, 20, 61, and 77 for examples), and stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) (see references 15, 16, 27, 34, and 55 for examples). There also have been improvements in peptide fractionation (22, 67). Therefore, we decided to apply newer quantitative approaches to more fully probe the richness of influenza virus-infected host cell proteomes to attempt to identify additional potential antiviral targets. We chose SILAC, using 12C6-Lys and 12C614N4-Arg (“light” [L]) and 13C6-Lys and 13C615N4-Arg (“heavy” [H]), because virtually every tryptic peptide is expected to contain an L or H label, thereby providing increased protein coverage; L and H samples are mixed together early in the process, thereby reducing sample-to-sample variability, and other such studies succeeded in identifying and quantitatively measuring up to several thousand proteins (7, 15, 34, 62). We succeeded in the current study in identifying and measuring nearly 4,700 cytosolic host proteins, of which 127 were significantly upregulated, including proteins involved in acetylation, cell structure, defense responses, protein binding, and responses to stress, stimulus, and virus, and 153 proteins, including those involved in alternative splicing, localization, transport, protein binding, and nucleoside, nucleotide, and nucleic acid metabolism that were significantly downregulated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses. (i) Viruses.

Influenza virus strain A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) was grown in embryonated hen eggs from laboratory stocks, and chorioallantoic fluid was harvested, aliquoted, and titered in MDCK cells by standard procedures (8). Additional stocks were made by recombinant means to exclude chorioallantoic fluid effects (53).

(ii) Cells.

Human lung A549 cells were routinely cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Intergen), and 2 mM l-glutamine. Cells were maintained as monolayers in 10% CO2 and were passaged by trypsinization 2 to 3 times each week. For SILAC labeling, cells were grown in DMEM provided with a SILAC phosphoprotein identification and quantification kit (Invitrogen Canada Inc.; Burlington, Ontario, Canada), supplemented as above (except without nonessential amino acids), and with 10% dialyzed FBS (Invitrogen Canada Inc.; Burlington, Ontario, Canada) plus 100 mg each of “light” (L) or “heavy” (H) l-lysine and l-arginine per liter of DMEM.

Infection.

Once the cells had grown through six doublings, L cells in T25 and T75 flasks were infected with A/PR/8/34 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 7 PFU per cell. An equivalent number of H cells were mock infected as the control. Cells were overlaid with the appropriate medium and cultured for various periods of time. Infections were carried out multiple times over several months.

Photomicrography.

Infected and mock-infected cells in the T25 flask were examined microscopically for cytopathic effect (CPE) at 0, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 h postinfection with a Nikon TE-2000, and cells were photographed with a Canon-A700 digital camera. Images were imported into Adobe and slight adjustments made in brightness and contrast, which did not alter image context with respect to each other.

Cell fractionation.

At 24 h postinfection, L and H cells in the T75 flasks were collected and counted. To verify the infection status of each culture, aliquots of all cultures were saved for virus titration and for Western blotting (see below). For comparative SILAC assays, equivalent numbers of L and H cells were mixed together, and the mixed cells were washed three times in >50 volumes of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For assays to confirm differential infection status, infected and mock-infected cells were processed separately. In assays destined for SDS-PAGE separations, washed cells were swollen in hypotonic buffer (10 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], supplemented with 1.1 μM pepstatin A) for 30 min on ice, and then cells were lysed by 20 passages through a 30-gauge needle. Lysis was confirmed microscopically, and nuclei and insoluble membranes were pelleted at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was saved as “cytosol.” The nuclei and crude membranes were resuspended in 200 μl of 0.5% NP-40 and incubated on ice for 30 min, and nuclei were removed by pelleting at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The “crude membranes” (supernatant) were transferred to a fresh microcentrifuge tube, and electrophoresis sample buffer was added to each of the three fractions (nuclear pellet, crude membranes, and cytosol), which were then frozen at −80°C until further processing took place. In assays destined for liquid chromatographic separations, washed cells were lysed with 0.5% NP-40, supplemented with 1.1 μM pepstatin A, and incubated on ice for 30 min, and nuclei were removed by pelleting at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The cytosol and soluble membranes (supernatant) were transferred to fresh microcentrifuge tubes, and the two fractions (nuclear pellet and supernatant) were frozen at −80°C until further processing took place.

Immunoblotting.

Aliquots of unlabeled and L- and H-labeled infected and mock-infected cells were separately harvested and dissolved with 0.5% NP-40 as described above, and cytosolic fractions were collected, mixed with SDS electrophoresis sample buffer, heated to 95°C for 5 min, and resolved in a 5 to 15% minigradient SDS-PAGE gel (6.0 by 10.0 by 0.1 cm) at 180 V for 50 min (until the bromophenol blue tracking dye was at the gel bottom), and proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF). The PVDF membranes were briefly stained with Ponceau to confirm protein transfer, blocked with 5% skim milk, and probed with various antibodies. Primary antibodies were mouse anti-influenza NP protein (74), α-GAPDH, α-vimentin, α-β-2-microglobulin, alpha vasodilatory-stimulated phosphoprotein (α-VASP), rabbit anti-actin, α-Rock2, α-Akt, α-cytokeratin 10, α-Bid, and goat anti-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP). Secondary antibodies were Alexa488-conjugated goat anti-mouse for NP and GAPDH, Alexa488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit for actin, or the appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse, goat anti-rabbit, or rabbit anti-goat for all other proteins. HRP was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence, film and fluorescent secondary antibodies were visualized, and band intensities were measured with an Alpha Innotech FluorChemQ MultiImage III instrument.

Protein digestion.

Protein content in the cytosolic and soluble membrane fractions collected as described above was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce; Rockford, IL) and bovine serum albumin standards. After protein concentration determinations, samples were diluted with freshly made 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate to provide concentrations of ∼1 mg/ml and a pH of ∼8. Three hundred microliters of each sample (∼300 μg of protein) was reduced, alkylated, and trypsin digested using the following procedure. Thirty microliters of freshly prepared 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate was added. The samples were then incubated for 45 min at 60°C. Thirty microliters of freshly prepared iodoacetic acid (500 mM solution in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate) was added to each tube, and the tubes were then incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Finally, 50 μl of 100 mM DTT solution was added to quench the excess iodoacetic acid. Samples were digested overnight at 37°C with 6 μg of sequencing grade trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI). The samples were lyophilized and stored at −80°C.

Peptide fractionation using 2-D RP HPLC.

A newly developed orthogonal procedure (32, 67) was employed for 2-D reversed-phase (RP) high-pH/RP low-pH peptide fractionation. Lyophilized tryptic digests were dissolved in 200 μl of 20 mM ammonium formate (pH 10) (buffer A for first-dimension separation), injected onto a 1- by 100-mm XTerra (Waters, Milford, MA) column, and fractionated using a 0.67% acetonitrile-per-minute linear gradient (Agilent 1100 Series high-performance liquid chromatography [HPLC] system; Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE) at a 150-μl/min flow rate. Sixty 1-min fractions were collected (covering an ∼40% acetonitrile concentration range) and concatenated using procedures described elsewhere (22, 67); the last 30 fractions were combined with the first 30 fractions in sequential order (i.e., 1 with 31; 2 with 32, etc.). Combined fractions were vacuum dried and redissolved in buffer A for the second-dimension RP separation (0.1% formic acid in water).

A splitless nano-flow Tempo LC system (Eksigent, Dublin, CA) with 20 μl sample injection via a 300-μm by 5-mm PepMap100 precolumn (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) and a 100-μm by 200-mm analytical column packed with 5 μm Luna C18(2) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) were used in the second-dimension separation prior to mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. Both eluents A (water) and B (acetonitrile) contained 0.1% formic acid as an ion-pairing modifier. A 0.33% acetonitrile-per-minute linear gradient (0 to 30% B) was used for peptide elution, providing a total 2-h run time per fraction in the second dimension.

Mass spectrometry, bioinformatics, and data mining.

A QStar Elite mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used in a data-dependent tandem MS (MS/MS) acquisition mode. One-second-survey MS spectra were collected (m/z 400 to 1,500), followed by MS/MS measurements on the three most intense parent ions (80 counts/s threshold, +2 to +4 charge state, m/z 100 to 1,500 mass range for MS/MS), using the manufacturer's “smart exit” (spectral quality 5) settings. Previously targeted parent ions were excluded from repetitive MS/MS acquisition for 60 s (50-mDa mass tolerance). Protein Pilot 2.0 (Applied Biosystems) software was used for protein identification and quantitation. Raw data files (30 in total for each run) were submitted for simultaneous searches using standard SILAC settings for QStar instruments. Proteins for which at least two fully trypsin-digested L and H peptides were detected at >99% confidence were used for subsequent comparative quantitative analysis.

Raw MS data files were analyzed by Protein Pilot, version 2.0, using the nonredundant human gene database. Proteins, and their confidences and L/H ratios, were returned with GeneInfo Identifier (gi) accession numbers.

Differential regulation within each experimental data set was determined by normalization of each data set, essentially as described previously (43). Briefly, every L/H ratio was converted into log2 space to determine geometric means and facilitate normalization. The average log2 L/H ratios and standard deviation of the log2 L/H ratios were determined for each data set, both before and after computational removal of the few (up to 12) significant outliers found in a few data sets. Every protein's log2 L/H ratio was then converted into a z-score, using the formula:

|

where b represents an individual protein in a data set population (a….n), and the z-score is the measure of how many standard deviation units (expressed as “σ”) that protein's log2 L/H ratio is away from its population mean. Thus, a protein with a z-score of >1.645σ indicates that that protein's differential expression lies outside the 90% confidence level, >1.960σ indicates that it is outside the 95% confidence level, 2.576σ indicates 99% confidence, and 3.291σ indicates 99.9% confidence. Z-scores of >1.960 were considered significant. GeneInfo Identifier numbers of all significantly regulated proteins were converted into HUGO nomenclature committee (HGNC) identifiers (IDs) by Uniprot (http://www.uniprot.org/), HGNC terms were submitted to and analyzed by the DAVID bioinformatic suite at the NIAID, version 6.7 (19, 41), and gene ontologies were examined with the “FAT” data sets. The gi numbers were also submitted to, and pathways constructed with, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software.

RESULTS

Kinetics of influenza virus-induced cytopathology in cultured A549 cells.

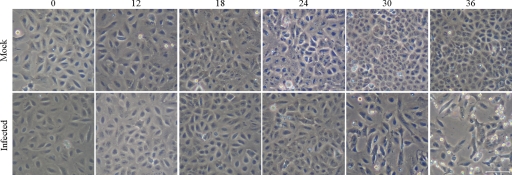

One of the key parameters for determining virus-induced alterations, and in separating such alterations from general stress responses related to cell death late in infection, is to determine when cytopathic effects (CPE) are manifested in the model system. Accordingly, we initially infected our A549-cultured human lung cells with influenza strain A/PR/8/34 (H1N1; PR8) at multiplicities of 7 PFU per cell (>99% of cells are initially infected as predicted by the Poisson distribution), and they were microscopically monitored for cell viability and CPE over time. Cells infected with PR8 and cultured for 24 h or less demonstrated no detectable CPE; there was minimal CPE detectable at 30 h postinfection (hpi), and CPE was readily apparent at later time points (Fig. 1). Therefore, in subsequent experiments, A549 cells were infected with the same MOI of PR8, cultured for 24 h, and processed in order to allow the virus to exert maximal effects without demonstrable CPE.

FIG. 1.

Photomicrographs of A549 cells infected with A/PR/8/34 at an MOI of 7 PFU/cell (bottom) or mock-infected (top) for the indicated hours postinfection (indicated at the top). Scale bar, 100 μm.

Two-dimensional HPLC provides more extensive protein identification than 1-D SDS-PAGE/1-D LC/ESI-MS.

Eukaryotic cells possess highly complex proteomes, and peptide sample complexity must be reduced prior to MS-based interrogation (reviewed in references 23 and 75). There are several strategies for reducing sample complexity. We initially evaluated and compared gel-based purification of intact cellular proteins to HPLC purification of digested peptides. Equivalent numbers of PR8-infected 12C6-Lys, 12C614N4-Arg (SILAC light), and mock-infected 13C6-Lys, 13C615N4-Arg (SILAC heavy) A549 cells were mixed together, and various purification methods were tested. Initially, mixtures of L- and H-labeled entire cells were dissolved in electrophoresis sample buffer and resolved in a single gel lane of a 5 to 15% SDS-PAGE minigel, the entire gel lane was cut into 24 slices, and each slice was processed by in-gel trypsin digestion. Peptides were extracted and processed as detailed more fully in Materials and Methods by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LC/ESI-MS); this resulted in the identification of about 300 pairs of proteins (data not shown).

We then fractionated mixed L-H cells as described in Materials and Methods to generate crude cytosolic, membrane, and nuclear fractions, each of which were separately resolved by 1-D SDS-PAGE/1-D LC/ESI-MS as described above. Approximately 250 to 550 L-H protein pairs were detected and measured in each fraction in each of 2 biologic replicates, using stringent protein identification criteria of 2 complete L and H tryptic peptides and an identification confidence of ≥99% (Table 1). There were some common proteins found in different fractions, such that compilation of both 1-D SDS-PAGE/1-D LC/ESI-MS analyses identified 1,002 pairs of proteins in the combined cytosolic and membrane fractions (Fig. 2 A). As an alternate strategy, equivalent L-H cell mixtures were washed and lysed with 0.5% NP-40 to obtain cytosolic and membrane fractions, proteins were digested with trypsin, and peptides were processed for 2-D HPLC/ESI-MS as detailed in Materials and Methods. Analyses of two separate biological replicates processed this way identified more than 2,100 pairs of proteins. More than 500 of the identified protein pairs were common to both the 1-D SDS-PAGE/1-D LC/ESI-MS and the 2-D HPLC/ESI-MS methods, and many proteins were also detected in the nuclear fractions (Fig. 2A).

TABLE 1.

Number of proteins, log2 L/H ratio means and standard deviations, and z-scores of SILAC-labeled proteins identified by various purification schemes

| Purification method | No. of proteins | Mean log2 L/H ratio | SD log2 | Z-scoresa |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ±1.960σ (95%) | ±2.576σ (99%) | ±3.291σ (99.9%) | ||||

| SDS-PAGE/LC | ||||||

| 1 Cytosol | 248 | 0.029 | 0.565 | 8, 6 | 8, 4 | 8, 1 |

| Crude membranes | 273 | 0.085 | 0.531 | 9, 5 | 8, 3 | 8, 2 |

| Nuclear | 262 | 0.083 | 0.678 | 15, 1 | 14, 0 | 11, 0 |

| 2 Cytosol | 467 | −0.034 | 0.478 | 20, 9 | 9, 6 | 4, 4 |

| Crude membranes | 524 | 0.011 | 0.422 | 22, 10 | 14, 8 | 11, 2 |

| Nuclear | 478 | 0.003 | 0.415 | 18, 12 | 13, 3 | 10, 2 |

| 2-D HPLC | ||||||

| 1 | 1,890 | 0.013 | 0.633 | 44, 52 | 25, 35 | 20, 23 |

| 2 | 846 | 0.046 | 0.506 | 22, 15 | 17, 9 | 14, 5 |

| 3 technical (1) | 2,509 | −0.030 | 0.539 | 47, 67 | 33, 42 | 23, 30 |

| 3 technical (2) | 2,574 | −0.020 | 0.533 | 55, 65 | 35, 37 | 26, 29 |

| Combined | 3,173 | −0.025 | 0.537 | |||

The first value is the number of upregulated proteins outside the indicated confidence level; the second number is the number of downregulated proteins outside the indicated confidence level.

FIG. 2.

Distributions of proteins identified in various experiments. (A and B) Venn diagrams of the numbers of identified proteins from various analyses. (A) Proteins from A/PR/9/34-infected A549 cells were fractionated into the cytosolic plus crude membrane (Cyto/Gel) and nuclei (Nuclei/Gel) fractions, resolved in SDS-PAGE, and then subjected to tryptic digest before 1-D LC/MS. Alternatively, proteins were harvested from cytosolic and crude membrane fractions and digested with trypsin, and then peptides were resolved by 2-D orthogonal LC/MS (2-D LC/MS). Results were compiled from two replicate experiments. (B) Proteins identified by the three separate 2-D LC/MS analyses. Proteins from the two technical replicate analyses of the third 2-D LC/MS run were merged prior to being combined with other data. (C) Frequency distributions of identified proteins in two influenza virus-infected A549 sample sets, with L/H ratios expressed as log2 values. Positive values represent upregulated host proteins in virus-infected cells; negative values represent downregulated host proteins. Only the distributions of one SDS-PAGE analysis and one 2-D LC/MS analysis are shown for clarity. Note that distributions are not identical, with different peak breadths, and not perfectly normal, with the 2-D LC/MS sample exhibiting several substantially downregulated proteins at approximately −13log2. Characteristics of all SDS-PAGE and 2-D LC/MS protein distributions, mean log2 L/H ratios, and standard deviations of log2 L/H ratios are shown in Table 1.

Having established that 2-D HPLC/ESI-MS identified more than twice as many protein pairs as 1-D SDS-PAGE/1-D LC/ESI-MS, we then performed two technical 2-D HPLC/ESI-MS analyses in an additional biological experiment. These technical replicates identified a total of 3,173 unique cytosolic proteins (Table 1), of which 2,044 were common to both replicates. Comparisons of each of these 2,044 common protein's log2 ratios showed a correlation of r2 = 0.660 (data not shown), indicating that most of the commonly identified proteins had similar L/H ratios in each technical replicate. Ten of the 2,044 proteins did not behave similarly in both replicate runs such that they differed in significance or direction of regulation. One protein (MGC2477) was measured as significantly upregulated 18-fold in one technical replicate but downregulated almost 2-fold in the other run. Nine other proteins appeared to be significantly up- or downregulated in one run (defined as described above) but were slightly regulated in the opposite direction in the other replicate. These 10 proteins were included in subsequent statistical analyses, but because we could not confidently establish whether each was up- or downregulated, we did not include them in lists of up- and downregulated proteins or in subsequent gene ontology and pathway analyses.

Influenza virus infection induces significant up- and downregulation of numerous cellular proteins.

Combination of all 2-D LC-identified proteins with all 1-D SDS-PAGE/1-D LC-identified proteins resulted in the identification and measurement of 4,817 total unique protein pairs. Inspection of each protein's log2 distribution indicated variability in each data set's mean log2 value and in each data set's log2 standard deviation (Fig. 2C; Table 1). Thus, every protein's L/H ratio was converted into a z-score as described in Materials and Methods to allow interexperiment comparisons.

Stratification of each protein's L/H ratio and its z-score from each experimental run indicated that numerous proteins were identified in each experiment that could be considered significantly regulated. For example, of the 248 proteins identified in the first SDS-PAGE/LC-prepared cytosol sample, 8 were upregulated at 95% confidence and each of these was also upregulated at 99.9% confidence (Table 1). Six proteins in the same data set were downregulated at 95% confidence, but only one of these proteins was also downregulated at 99.9% confidence. Inspection of protein L/H ratios and z-scores indicated that most proteins differentially regulated at >95% confidence had L/H ratios altered by >1.6-fold, and most proteins differentially regulated at >99% confidence had L/H ratios altered by >2.2-fold. However, a number of proteins with L/H ratios in the range of 0.667 to 1.500 also had significant z-scores. For example, a protein might have an L/H ratio of 1.2 but be considered significant if it was a member of a population with a negative mean log2 L/H and a small standard deviation (i.e., 2nd cytosol sample), whereas another protein might have an L/H ratio of 2.2 but be considered nonsignificant if it was a member of a population with a positive mean log2 L/H ratio and a larger standard deviation (i.e., first nuclear sample). Thus, although some studies have set L/H ratio significance levels ranging from as little as 1.4-fold (29) or less to as much as 3-fold (49), we elected to assign significance based upon z-scores, with a few exceptions. Of the 4,817 total identified proteins, only 128 were found exclusively in the nuclei fractions derived from the preliminary limited 1-D SDS-PAGE/1-D LC analyses; thus, we focused further analyses on the 4,689 cytosolic proteins, with the expectation that the nuclear proteins will be studied more extensively at a later date.

Using the above criteria, we identified and measured 127 proteins that were significantly upregulated (Table 2). A protein was usually included in this table if a minimum of one-half of its biologic replicate z-scores were >1.960σ. Proteins were not considered significantly regulated if there were significant differences in their z-scores from the 2 technical replicates of the 3rd 2-D HPLC analysis. Some of the significantly upregulated proteins included vimentin and Mx2, known to be upregulated by inflammation and/or influenza virus infection, and both upregulated about 5- to 7-fold. Although the significance of each protein's fold change was based upon z-score, we also included every protein's average fold level alteration, determined by averaging each protein's log2 L/H value from every observation (see Table ST-1 in the supplemental material). A total of 153 proteins were significantly downregulated using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as above (Table 3). Many of these, including 38 proteins (such as ARHGAP5, cyclophilin-33A, and the Vav 3 oncogene), were significantly downregulated (z-score < −4.0σ) >100-fold.

TABLE 2.

A549 proteins increased >95% confidencea

| Accession no. | HGNC ID | Name/description | L/H ratioc | Biological replicate | Z-score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-D HPLC/MSb |

SDS-PAGEd | ||||||||

| A | B | 2DLC1 | 2DLC2 | ||||||

| Proteins measured in >1 biologic replicate | |||||||||

| gi|4755085 | COL1A1 | Pro alpha 1(I) collagen | 17.307 | 2 | 5.845 | ||||

| gi|6013427 | ALBU | Serum albumin precursor | 9.979 | 2 | 6.104 | 3.948 | |||

| gi|5031841 | KRT6B | Keratin 6B | 8.514 | 3 | 6.448 | ||||

| gi|547749 | K1C10 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10 (cytokeratin 10) (CK-10) (keratin 10) (K10) | 7.214 | 7 | 6.069 | 11.870 | 6.434 | ||

| gi|5030431 | VIME | Vimentin | 6.944 | 2 | 3.664 | 6.347 | |||

| gi|5031839 | K2C6A | Keratin 6A | 5.939 | 3 | 4.559 | 3.044 | |||

| gi|55956899 | K1C9 | Keratin 9 | 5.700 | 7 | 5.481 | 5.888 | |||

| gi|17318569 | KRT1 | Keratin 1 | 5.141 | 8 | 8.213 | 12.290 | 2.308 | 5.600 | |

| gi|49456703 | Q6FH82 | IFITM2 | 5.002 | 2 | 6.397 | ||||

| gi|2996631 | Q75MY7 | MX2 | 4.968 | 2 | 4.771 | 3.406 | |||

| gi|56757580 | K2C5 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 5 (cytokeratin 5 [CK-5]) (keratin 5 [K5]) (58-kDa cytokeratin) | 4.273 | 2 | 4.445 | ||||

| gi|47132620 | K22E | Keratin 2 | 4.243 | 7 | 5.140 | 5.913 | |||

| gi|15431310 | K1C14 | Keratin 14 | 3.762 | 4 | 8.348 | ||||

| gi|48146249 | B2 M | Beta-2-microglobulin | 2.788 | 2 | 3.775 | ||||

| gi|14550514 | UCRP | ISG15 ubiquitin-like modifier | 2.735 | 3 | 6.499 | ||||

| gi|4580013 | SNX6 | Sorting nexin-6, TRAF4-associated factor 2 | 2.608 | 2 | −0.557 | 6.024 | |||

| gi|55960992 | H2A2C | Histone 2, H2ac | 2.495 | 2 | 4.848 | 0.098 | |||

| gi|55961043 | SF13A | FUS-interacting protein (serine-arginine rich) 1 | 2.293 | 2 | 2.575 | 1.807 | |||

| gi|13279173 | CSN4 | COP9 constitutive photomorphogenic homolog subunit 4 (arabidopsis) | 2.287 | 2 | 0.040 | 4.640 | |||

| gi|34784772 | GPI | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 2.118 | 3 | 6.172 | −0.602 | |||

| gi|34783347 | RAB15 | RAB15, member RAS oncogene family | 1.959 | 3 | 5.252 | 0.148 | |||

| gi|56122599 | Q5Q9Z3 | Leukemia multidrug resistance-associated protein | 1.865 | 2 | 2.225 | ||||

| gi|7705893 | DCTN4 | Dynactin 4 (p62) | 1.864 | 2 | 2.884 | 4.081 | −0.086 | ||

| gi|4218955 | FLNC | Gamma-filamin | 1.847 | 2 | −0.325 | 3.784 | |||

| gi|13623669 | HEXI1 | Hexamethylene bis-acetamide inducible 1 | 1.746 | 2 | 2.313 | 2.035 | 0.833 | ||

| gi|39645500 | SCYL2 | SCY1-like 2 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | 1.699 | 2 | 2.414 | 0.396 | |||

| gi|40850903 | Q549N5 | Signal recognition particle receptor, B subunit | 1.613 | 2 | 2.626 | 2.207 | 0.151 | ||

| gi|49457320 | Q6FGE5 | S100A10 | 1.567 | 6 | 0.324 | 2.112 | |||

| gi|6031192 | MPCP | Solute carrier family 25 member 3 isoform a precursor | 1.538 | 3 | 3.114 | −0.092 | |||

| gi|3088341 | RS21 | Ribosomal protein S21 | 1.481 | 2 | 2.799 | ||||

| gi|29839750 | AT1A3 | Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase alpha-3 chain (sodium pump 3) (Na+/K+ ATPase 3) [alpha(III)] | 1.386 | 2 | 2.114 | −0.994 | |||

| gi|57160805 | SH3L1 | SH3 domain binding glutamic acid-rich protein-like | 1.368 | 2 | −0.316 | 2.355 | |||

| gi|37514845 | NUDC1 | NudC domain containing 1 | 1.349 | 2 | 2.130 | −0.422 | 0.000 | ||

| gi|55661047 | RRBP1 | Ribosome binding protein 1 homolog, 180 kDa (dog) | 1.323 | 2 | −0.240 | 2.066 | |||

| gi|57162423 | 5NTD | 5′ nucleotidase, ecto (CD73) | 1.271 | 4 | 4.652 | 2.585 | 1.392 | ||

| gi|984325 | 6PGD | Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 1.148 | 3 | 2.775 | ||||

| Proteins measured in only 1 biologic replicate but in 2 technical replicates | |||||||||

| gi|435476 | K1C9 | Cytokeratin 9 | 33.818 | 10.613 | 8.434 | ||||

| gi|57864582 | HORN | Hornerin | 17.710 | 7.367 | 8.212 | ||||

| gi|435675 | MT1X | MT-1l protein | 4.544 | 4.275 | 3.971 | ||||

| gi|345829 | *e | Ubiquitin carrier protein E2, human | 3.684 | 4.948 | 2.154 | ||||

| gi|5902146 | UBE2C | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2C isoform 1 | 3.438 | 2.942 | 3.808 | ||||

| gi|57208424 | CRNL1 | Crn, crooked neck-like 1 (Drosophila) | 3.131 | 0.861 | 5.404 | ||||

| gi|52352803 | ZNT1 | Solute carrier family 30 (zinc transporter), member 1 | 2.644 | 2.504 | 2.827 | ||||

| gi|5817162 | DREB | Hypothetical protein | 2.577 | 1.882 | 3.317 | ||||

| gi|36327 | METK2 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase | 2.355 | 2.697 | 2.007 | ||||

| gi|4507711 | TTC1 | Tetratricopeptide repeat domain 1 | 2.316 | 1.692 | 2.932 | ||||

| gi|4529892 | HSP71 | HSP70-2 | 1.949 | 1.590 | 2.101 | ||||

| gi|4689140 | GBRL2 | Ganglioside expression factor 2 homolog | 1.932 | 2.350 | 1.285 | ||||

| gi|56207188 | SSU72 | Novel protein (HSPC182) | 1.759 | 2.213 | 0.915 | ||||

| gi|20986531 | MK01 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | 1.738 | 1.011 | 2.064 | ||||

| gi|21619574 | OSGEP | O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase | 1.711 | 1.971 | 1.011 | ||||

| gi|54696790 | PRAF1 | Rab acceptor 1 (prenylated) | 1.644 | 2.075 | 0.688 | ||||

| Proteins measured only once | |||||||||

| gi|13650074 | HBA | Hemoglobin alpha-1 globin chain | 121.222 | 13.028 | |||||

| gi|18418633 | HBB | Mutant beta-globin | 47.517 | 8.781 | |||||

| gi|38788274 | BPTF | Fetal Alzheimer antigen isoform 1 | 30.503 | 7.770 | |||||

| gi|4885215 | ERBB4 | v-erb-a erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 4 isoform JM-a/CVT-1 precursor | 25.424 | 8.724 | |||||

| gi|181402 | K22E | Epidermal cytokeratin 2 | 18.987 | 7.942 | |||||

| gi|55958235 | MARH5 | RING finger protein 153 | 16.959 | 7.702 | |||||

| gi|10440389 | Q9H7N8 | FLJ00030 protein | 16.475 | 6.366 | |||||

| gi|31815 | DHE4 | Glutamate dehydrogenase [NAD(P)+] | 15.471 | 7.454 | |||||

| gi|19923667 | RSAD2 | Radical S-adenosyl methionine domain containing 2 | 14.315 | 6.046 | |||||

| gi|34416 | TRFL | Precursor (amino acids 19 to 692) | 14.032 | 6.000 | |||||

| gi|13623477 | WDR4 | WD repeat domain 4 | 13.968 | 7.177 | |||||

| gi|2183299 | AL1A1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 | 12.845 | 6.950 | |||||

| gi|4557701 | K1C17 | Keratin 17 | 12.223 | 6.641 | |||||

| gi|34190642 | TRXR3 | TXNRD3 protein | 12.096 | 6.787 | |||||

| gi|38541654 | Q53YJ2 | Dermcidin | 9.891 | 6.242 | |||||

| gi|7688699 | Q9P0H9 | RER1 protein | 9.749 | 6.156 | |||||

| gi|51470993 | * | Predicted: similar to sucb isoform 1 | 9.129 | 5.980 | |||||

| gi|51467148 | * | Predicted: similar to tropomyosin 4 | 9.005 | 5.988 | |||||

| gi|4557325 | APOE | Apolipoprotein E precursor | 8.927 | 4.969 | |||||

| gi|9437341 | Q9NRV0 | x 004 protein | 7.502 | 4.573 | |||||

| gi|1911770 | NCOR2 | T3 receptor-associating cofactor 1; TRAC-1 | 7.469 | 5.442 | |||||

| gi|609308 | TCPG | Cytoplasmic chaperonin hTRiC5 | 7.181 | 5.337 | |||||

| gi|27734452 | RAB15 | Ras-related protein Rab-15 | 6.862 | 5.252 | |||||

| gi|4186185 | VIPAR | Unknown | 6.835 | 4.361 | |||||

| gi|3075509 | PLK2 | Serum-inducible kinase | 6.041 | 4.080 | |||||

| gi|22671717 | HBA | Hemoglobin alpha-2 | 5.865 | 4.012 | |||||

| gi|541678 | D3DTU3 | hbZ17 | 5.798 | 3.986 | |||||

| gi|57162615 | ANK3 | Ankyrin 3, node of Ranvier (ankyrin G) | 5.631 | 3.919 | |||||

| gi|17390794 | TISB | Zinc finger protein 36, C3H type-like 1 | 5.303 | 3.783 | |||||

| gi|40788366 | TM63A | KIAA0792 protein | 4.782 | 4.367 | |||||

| gi|115143 | BTF3 | Transcription factor BTF3 (RNA polymerase B transcription factor 3) | 4.745 | 4.253 | |||||

| gi|3763907 | RBP56 | RBP56/hTAFII68 | 4.704 | 4.006 | |||||

| gi|49065664 | KATNAL2 | Katanin p60 subunit A-like 2 | 4.627 | 4.160 | |||||

| gi|56204086 | D3DVZ4 | C20orf16 | 4.450 | 4.055 | |||||

| gi|28559080 | SMOX | Polyamine oxidase isoform 4 | 3.868 | 3.700 | |||||

| gi|55666285 | LCN1L1 | Lipocalin 1-like 1 | 3.808 | 3.473 | |||||

| gi|14043853 | KITH | Thymidine kinase 1, soluble | 3.803 | 3.024 | |||||

| gi|55664988 | KHDR1 | KH domain containing, RNA binding, signal transduction associated 1 | 3.641 | 3.591 | |||||

| gi|51477696 | PARVB | Parvin, beta isoform a | 3.628 | 3.508 | |||||

| gi|14602868 | GLTP | Glycolipid transfer protein | 3.597 | 3.485 | |||||

| gi|56417844 | ARK73 | Aldo-keto reductase family 7, member A3 (aflatoxin aldehyde reductase) | 3.546 | 2.865 | |||||

| gi|11036646 | H2BFS | H2B histone family, member S | 3.521 | 3.495 | |||||

| gi|56404694 | RIOK3 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase RIO3 (RIO kinase 3) (sudD homolog) | 3.133 | 2.583 | |||||

| gi|40548422 | CHM4A | Chromatin-modifying protein 4A | 3.130 | 3.516 | |||||

| gi|386849 | K2C6B | Keratin type II | 3.115 | 3.113 | |||||

| gi|39843342 | A16L1 | APG16L beta | 3.090 | 2.551 | |||||

| gi|27657357 | Q861B7 | MHC class I antigen | 2.933 | 2.939 | |||||

| gi|3559910 | CMC1 | Aralar1 | 2.916 | 2.923 | |||||

| gi|37515270 | MACD1 | LRP16 protein | 2.867 | 2.381 | |||||

| gi|5815178 | TX264 | Unknown | 2.855 | 3.557 | |||||

| gi|1143492 | GRP78 | BiP | 2.846 | 2.858 | |||||

| gi|453155 | K1C9 | Keratin 9 | 2.792 | 3.482 | |||||

| gi|13937792 | Q6FG85 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 1B | 2.778 | 2.309 | |||||

| gi|1296662 | PLEC1 | Plectin | 2.721 | 2.761 | |||||

| gi|50949925 | Q6AI07 | Hypothetical protein | 2.685 | 3.348 | |||||

| gi|9931112 | Q9GJF2 | Human leukocyte antigen Cw | 2.659 | 2.685 | |||||

| gi|55665435 | B4DEB1 | H3 histone, family 3A | 2.659 | 2.209 | |||||

| gi|47682981 | GRPE2 | GrpE-like 2, mitochondrial (Escherichia coli) | 2.619 | 2.175 | |||||

| gi|6730096 | PAI1 | Chain D, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 | 2.619 | 2.635 | |||||

| gi|4758544 | HNRNPC | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C isoform b | 2.587 | 2.610 | |||||

| gi|24659879 | PRDX2 | Peroxiredoxin 2 | 2.562 | 2.124 | |||||

| gi|7209305 | MRP7 | FLJ00002 protein | 2.518 | 2.085 | |||||

| gi|4826774 | UCRP | Interferon, alpha-inducible protein (clone IFI-15K) | 2.504 | 2.515 | |||||

| gi|7020602 | MTMRC | Unnamed protein product | 2.495 | 2.064 | |||||

| gi|2143260 | P3C2A | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase | 2.454 | 2.461 | |||||

| gi|22760981 | Q8NC04 | Unnamed protein product | 2.331 | 2.329 | |||||

| gi|48145713 | Q6IBK5 | GTF2F1 | 2.267 | 2.249 | |||||

| gi|55959755 | RPL29 | Ribosomal protein L29 | 2.261 | 2.233 | |||||

| gi|33357878 | DCK | Chain B, structure of human Dck complexed with gemcitabine and Adp-Mg | 2.167 | 2.131 | |||||

| gi|56205909 | RAB4A | RAB4A, member of RAS oncogene family | 2.166 | 2.130 | |||||

| gi|4240137 | PCF11 | KIAA0824 protein | 2.136 | 2.093 | |||||

| gi|38516 | CAV1 | Caveolin | 2.091 | 2.010 | |||||

| gi|2924620 | SPIT2 | Hepatocyte growth factor activator inhibitor type 2 | 2.044 | 2.415 | |||||

| gi|642239 | 1C03 | Class I histocompatibility antigen HLA-CW3 | 1.866 | 2.104 | |||||

| gi|825616 | ACTB | Unnamed protein product | 1.819 | 2.017 | |||||

Protein is included if at least half of the biologic z-score values are ≥1.960σ (indicated by bolding) and there are no major disagreements between technical replicates A and B.

2-D HPLC runs; A and B refer to 2 technical replicates of a third biologic sample; 2DLC1 and 2DLC2 refer to the first and second 2-D HPLC runs.

L/H ratio refers to the geometric mean of all log2 L/H values for each given gi number, expressed as relative protein quantity in infected cultures.

Z-scores from multiple SDS-PAGE fractions are collapsed into a single most significant value for clarity.

*, unable to map; record obsolete or removed.

TABLE 3.

A549 proteins decreased >95% confidencea

| Accession no. | HGNC ID | Name/description | L/H ratioc | Biological replicate | Z-score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-D HPLC/MSb |

SDS-PAGEd | ||||||||

| A | B | 2DLC1 | 2DLC2 | ||||||

| Proteins measured in >1 biologic replicate | |||||||||

| gi|27597059 | DNJC9 | DnaJ homolog, subfamily C, member 9 | 0.009 | 2 | −0.155 | −0.554 | −21.013 | ||

| gi|50949588 | LS14A | Hypothetical protein | 0.009 | 2 | −0.279 | −26.334 | |||

| gi|13124770 | VKOR1 | Vitamin K epoxide reductase complex, subunit 1 isoform 1 | 0.009 | 2 | −24.902 | −0.409 | |||

| gi|37181648 | WDR82 | WD40 protein | 0.011 | 2 | 0.593 | 0.061 | −21.013 | ||

| gi|5821389 | 8ODP | MTH1a-Met83 (p26), MTH1b-Met83 (p22), MTH1c-Met83 (p21), MTH1d-Met83 (p18) | 0.012 | 2 | −24.902 | 1.014 | |||

| gi|55665273 | B9EKV4 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 9 family, member A1 | 0.057 | 2 | −0.371 | −15.994 | |||

| gi|45827757 | TACC2 | Transforming, acidic coiled-coil-containing protein 2 isoform a | 0.074 | 2 | −24.615 | −1.545 | −0.726 | ||

| gi|5726629 | SNX12 | Sorting nexin 12 | 0.227 | 2 | −0.712 | −0.442 | −6.243 | ||

| gi|38511857 | GSLG1 | Golgi apparatus protein 1 | 0.342 | 2 | −3.394 | −4.634 | −2.215 | ||

| gi|9910266 | KIF15 | Kinesin family member 15 | 0.344 | 2 | −1.462 | −2.124 | −3.330 | ||

| gi|33563340 | MYH14 | Myosin, heavy polypeptide 14 | 0.358 | 2 | −3.286 | −1.859 | |||

| gi|20384898 | CTNB1 | Beta-catenin | 0.374 | 3 | −5.387 | −1.942 | 0.164 | ||

| gi|5138999 | NDUS3 | NADH-ubiquinone reductase | 0.416 | 2 | −1.260 | −2.098 | −2.564 | ||

| gi|47678533 | GTPB1 | GTPBP1 | 0.425 | 2 | −1.776 | −2.361 | |||

| gi|55962101 | IF4G3 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 gamma 3 | 0.443 | 2 | −2.085 | −1.532 | −2.157 | ||

| gi|51479145 | BIG1 | Brefeldin A-inhibited guanine nucleotide-exchange protein 1 | 0.461 | 2 | −2.619 | −1.315 | |||

| gi|21961441 | STRN4 | Striatin, calmodulin binding protein 4 | 0.537 | 2 | −4.143 | 0.721 | |||

| gi|763122 | RAB35 | Ray | 0.572 | 2 | −1.786 | −2.023 | −1.110 | ||

| gi|7582292 | Q9NZE6 | BM-010 | 0.576 | 2 | −0.332 | −1.135 | −2.369 | ||

| gi|4886522 | Q75MJ1 | Hypothetical protein | 0.584 | 2 | −3.130 | 0.236 | |||

| gi|32698702 | HECTD1 | HECT domain containing 1 | 0.605 | 2 | −3.042 | −1.500 | −0.345 | ||

| gi|21752190 | Q8N9Z3 | Unnamed protein product | 0.606 | 2 | 0.654 | −4.459 | |||

| gi|4098297 | IF2B3 | Koc1 | 0.610 | 2 | −1.988 | −1.796 | −0.947 | ||

| gi|520587 | KPCD | Protein kinase C delta-type | 0.611 | 2 | −2.028 | −0.387 | |||

| gi|27881820 | UN45A | Unc-45 homolog A (Caenorhabditis elegans) | 0.638 | 2 | 0.073 | −2.099 | |||

| gi|12803105 | NUCB1 | Nucleobindin 1 | 0.656 | 4 | −2.422 | −2.116 | 1.074 | −2.188 | −1.659 |

| gi|28422560 | NUP53 | NUP35 protein | 0.700 | 2 | −2.049 | −1.554 | −0.096 | ||

| gi|7022606 | PPME1 | Unnamed protein product | 0.716 | 2 | 0.043 | −2.070 | |||

| gi|4808278 | ERG7 | Lanosterol synthase | 0.721 | 2 | −0.973 | −2.703 | 0.081 | ||

| gi|6563210 | NSF1C | P47 protein | 0.722 | 2 | −2.753 | ||||

| gi|57014043 | Q5I6Y6 | Lamin A/C transcript variant 1 | 0.756 | 3 | −2.320 | −2.094 | −0.199 | ||

| gi|36155 | RIR2 | Small subunit ribonucleotide reductase | 0.759 | 2 | −1.575 | −2.115 | 0.322 | ||

| gi|5726310 | 1433G | 14-3-3 gamma protein | 0.812 | 2 | −2.185 | ||||

| gi|913174 | LAP2A | TRPP | 0.847 | 3 | −0.325 | −2.416 | |||

| gi|54648253 | FUBP2 | KHSRP protein | 0.950 | 6 | −0.349 | −0.068 | 0.893 | −0.222 | −1.970 |

| Proteins measured in 1 biologic replicate only but in 2 technical replicates | |||||||||

| gi|5837964 | Q564D3 | Endothelial protein C receptor | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.615 | −24.902 | |||

| gi|18490620 | EPCR | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 7, 35 kDa | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.615 | −24.902 | |||

| gi|21361822 | NDUFA13 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex 13 | 0.0020 | 1 | −8.653 | −24.902 | |||

| gi|56550065 | CPLX2 | Complexin 2 | 0.0055 | 1 | −24.615 | −3.229 | |||

| gi|30354483 | NAA40 | N-acetyltransferase 11 | 0.0063 | 1 | −2.436 | −24.902 | |||

| gi|34530730 | BTBDB | Unnamed protein product | 0.0064 | 1 | −2.376 | −24.902 | |||

| gi|55960776 | D3DVC8 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L24 | 0.0065 | 1 | −2.290 | −24.902 | |||

| gi|4504009 | AGAL | Galactosidase, alpha | 0.0081 | 1 | −1.051 | −24.902 | |||

| gi|7657671 | UBF1 | Upstream binding transcription factor, RNA polymerase I | 0.209 | 1 | −3.494 | −4.840 | |||

| gi|29791720 | MET10 | METT10D protein | 0.223 | 1 | −3.919 | −4.080 | |||

| gi|39645799 | Q6P3U7 | RXRA protein | 0.278 | 1 | −3.678 | −3.131 | |||

| gi|6730223 | PROF2 | Chain D, crystal structure of human profilin Ii | 0.284 | 1 | −0.987 | −5.718 | |||

| gi|4503453 | EDF1 | Endothelial differentiation-related factor 1 isoform alpha | 0.297 | 1 | −4.678 | −1.759 | |||

| gi|55960673 | D3DPX7 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type F | 0.313 | 1 | −3.252 | −2.916 | |||

| gi|25987321 | Q54A15 | URP1 | 0.324 | 1 | −2.317 | −3.669 | |||

| gi|55770850 | CP24A | Cytochrome P450, family 24 precursor | 0.364 | 1 | −2.915 | −2.427 | |||

| gi|23512254 | SF01 | SF1 protein | 0.379 | 1 | −2.849 | −2.284 | |||

| gi|27769298 | TRI25 | Tripartite motif-containing 25 | 0.439 | 1 | −1.915 | −2.425 | |||

| gi|457262 | Q7KZ24 | Nuclease-sensitive element binding protein 1 | 0.449 | 1 | −2.011 | −2.209 | |||

| gi|10798851 | FADS2 | Fatty acid desaturase 2 | 0.472 | 1 | −2.412 | −1.539 | |||

| gi|10436660 | Q9H7U7 | Unnamed protein product | 0.487 | 1 | −2.703 | −1.074 | |||

| gi|34999 | CADH2 | Unnamed protein product | 0.487 | 1 | −2.253 | −1.522 | |||

| gi|4589628 | PALLD | KIAA0992 protein | 0.487 | 1 | −2.653 | −1.117 | |||

| gi|4503131 | CTNNB1 | Catenin (cadherin-associated protein), beta 1, 88 kDa | 0.487 | 1 | −2.154 | −1.621 | |||

| gi|14124936 | CO044 | Chromosome 15, open reading frame 44 | 0.491 | 1 | −1.782 | −1.960 | |||

| gi|6492130 | D3DU08 | Urokinase receptor-associated protein uPARAP | 0.491 | 1 | −1.359 | −2.386 | |||

| gi|2865163 | TGFI1 | Hic-5 | 0.499 | 1 | −2.376 | −1.271 | |||

| gi|4506409 | RANBP3 | RAN binding protein 3 isoform RANBP3-a | 0.505 | 1 | −2.390 | −1.189 | |||

| gi|4759068 | SCO1 | Cytochrome oxidase-deficient homolog 1 | 0.507 | 1 | −1.395 | −2.177 | |||

| gi|27477134 | PO210 | Nucleoporin 210 | 0.509 | 1 | −2.405 | −1.135 | |||

| gi|7657683 | XCT | Solute carrier family 7, (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system) member 11 | 0.542 | 1 | −2.229 | −0.972 | |||

| Proteins measured only once | |||||||||

| gi|49899808 | RHG05 | ARHGAP5 protein | 0.0001 | 1 | −21.013 | ||||

| gi|47115211 | ARL3 | ARL3 | 0.0001 | 1 | −26.334 | ||||

| gi|5326759 | KCC2B | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II beta e′ subunit | 0.0001 | 1 | −21.013 | ||||

| gi|8571386 | ICLN | Chloride ion current inducer protein I (Cln) | 0.0001 | 1 | −26.334 | ||||

| gi|51594277 | Q670S4 | Hemoglobin Lepore-Baltimore | 0.0001 | 1 | −21.013 | ||||

| gi|21739669 | IWS1 | Hypothetical protein | 0.0001 | 1 | −21.013 | ||||

| gi|21739912 | HTR7A | Hypothetical protein | 0.0001 | 1 | −21.013 | ||||

| gi|34365494 | CE044 | Hypothetical protein | 0.0001 | 1 | −21.013 | ||||

| gi|57997169 | Q5JPD9 | Hypothetical protein | 0.0001 | 1 | −21.013 | ||||

| gi|57471655 | KDM5C | Jumonji, AT-rich interactive domain 1C (RBP2-like) | 0.0001 | 1 | −21.013 | ||||

| gi|6382020 | RHG31 | KIAA1204 protein | 0.0001 | 1 | −21.013 | ||||

| gi|56081771 | DUSTY | Receptor-interacting protein kinase 5 | 0.0001 | 1 | −21.013 | ||||

| gi|55960721 | VAV3 | vav 3 oncogene | 0.0001 | 1 | −21.013 | ||||

| gi|23903 | MK04 | 63-kDa protein kinase | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.902 | ||||

| gi|29727 | MYH7 | Cardiac beta myosin-heavy chain | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.902 | ||||

| gi|25990944 | CLIC6 | Chloride channel form B | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.615 | ||||

| gi|2828149 | PPIE | Cyclophilin-33A | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.902 | ||||

| gi|115855 | CBL | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase CBL (signal transduction protein CBL) (proto-oncogene c-CBL) (casitas B-lineage lymphoma proto-oncogene) (RING finger protein 55) | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.902 | ||||

| gi|6942004 | EHD3 | EH domain containing protein 2 | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.615 | ||||

| gi|18676696 | MOV10 | FLJ00247 protein | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.615 | ||||

| gi|42407269 | HELLS | Lymphoid specific helicase variant 8 | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.902 | ||||

| gi|20986521 | MK08 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 isoform 4 | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.902 | ||||

| gi|3041706 | MYH6 | Myosin-heavy chain, cardiac muscle alpha isoform (MyHC-alpha) | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.902 | ||||

| gi|55664366 | STRBP | Spermatid perinuclear RNA binding protein | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.615 | ||||

| gi|5454100 | TACC1 | Transforming, acidic coiled-coil-containing protein 1 | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.902 | ||||

| gi|35438 | PGK2 | Unnamed protein product | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.615 | ||||

| gi|13124617 | VTI1B | Vesicle transport through interaction with t-SNAREs homolog 1B (vesicle transport v-SNARE protein Vti1-like 1) (Vti1-rp1) | 0.0001 | 1 | −24.902 | ||||

| gi|7020344 | MIO | Unnamed protein product | 0.022 | 1 | −8.672 | ||||

| gi|46250008 | PP4R4 | KIAA1622 | 0.108 | 1 | −5.090 | ||||

| gi|51859376 | H33 | H3 histone, family 3A | 0.131 | 1 | −5.138 | ||||

| gi|46249414 | LTBP1 | Latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein 1 isoform LTBP-1L | 0.148 | 1 | −4.380 | ||||

| gi|576554 | ANT3 | Antithrombin III variant | 0.187 | 1 | −3.841 | ||||

| gi|21264337 | ARAP3 | Centaurin, delta 3 | 0.228 | 1 | −3.391 | ||||

| gi|4557707 | L1CAM | L1 cell adhesion molecule isoform 1 precursor | 0.243 | 1 | −3.244 | ||||

| gi|55664563 | KI67 | Antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki-67 | 0.253 | 1 | −3.626 | ||||

| gi|39932736 | MYO5B | Myosin-5B (Myosin Vb) | 0.265 | 1 | −3.046 | ||||

| gi|31127073 | RANB9 | RANBP9 protein | 0.266 | 1 | −3.038 | ||||

| gi|7023521 | FBX3 | Unnamed protein product | 0.275 | 1 | −2.964 | ||||

| gi|40788219 | NRCAM | KIAA0343 | 0.277 | 1 | −3.443 | ||||

| gi|190133 | AT2B1 | Plasma membrane Ca2+ pumping ATPase | 0.279 | 1 | −3.420 | ||||

| gi|16741274 | Q53SZ8 | Prolactin regulatory element binding | 0.279 | 1 | −2.929 | ||||

| gi|3413793 | NB5R3 | NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase | 0.281 | 1 | −3.759 | ||||

| gi|51467774 | RPS3AP5 | Predicted: similar to ribosomal protein S3a isoform 1 | 0.289 | 1 | −3.121 | ||||

| gi|6468766 | LCAP | Oxytocinase/insulin-responsive aminopeptidase, variant 1 | 0.292 | 1 | −2.827 | ||||

| gi|22761383 | CAB45 | Unnamed protein product | 0.304 | 1 | −3.132 | ||||

| gi|55859586 | NU188 | Nucleoporin, 188 kDa | 0.304 | 1 | −2.732 | ||||

| gi|55664592 | ARGAL | Novel protein | 0.319 | 1 | −2.625 | ||||

| gi|10799803 | RBSK | Ribokinase | 0.321 | 1 | −2.608 | ||||

| gi|6983729 | MYL9 | MYL9 | 0.325 | 1 | −3.007 | ||||

| gi|21311254 | STXB6 | Amisyn | 0.330 | 1 | −2.546 | ||||

| gi|5689473 | NUDC3 | KIAA1068 protein | 0.337 | 1 | −2.497 | ||||

| gi|45501300 | Q6NXG4 | WDR13 protein | 0.338 | 1 | −2.491 | ||||

| gi|23273305 | D3DS37 | Jub, ajuba homolog (Xenopus laevis) | 0.338 | 1 | −2.490 | ||||

| gi|1685075 | PTPRJ | Density-enhanced phosphatase-1 | 0.342 | 1 | −2.817 | ||||

| gi|22902182 | RAVR1 | RAVER1 protein | 0.348 | 1 | −2.425 | ||||

| gi|57160661 | MIPEP | Mitochondrial intermediate peptidase | 0.355 | 1 | −2.380 | ||||

| gi|27764863 | SLC25A6 | Solute carrier family 25, member A6 | 0.355 | 1 | −2.716 | ||||

| gi|50949497 | ALO17 | Hypothetical protein | 0.364 | 1 | −2.700 | ||||

| gi|15559717 | AP2A1 | AP2A1 protein | 0.368 | 1 | −2.941 | ||||

| gi|115351 | CO5A2 | Collagen alpha-2(V) chain precursor | 0.381 | 1 | −2.222 | ||||

| gi|55960069 | CJ076 | Novel protein | 0.387 | 1 | −2.185 | ||||

| gi|21706672 | CRIP2 | Cysteine-rich protein 2 | 0.387 | 1 | −2.531 | ||||

| gi|31874098 | NRCAM | Hypothetical protein | 0.388 | 1 | −2.477 | ||||

| gi|45501252 | PRAX | Periaxin | 0.389 | 1 | −2.780 | ||||

| gi|20306890 | PSA7L | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, alpha type, 8 | 0.392 | 1 | −2.500 | ||||

| gi|57162346 | DIAPH3 | Diaphanous homolog 3 (Drosophila) | 0.392 | 1 | −2.154 | ||||

| gi|292870 | UFO | Tyrosine kinase receptor | 0.392 | 1 | −2.497 | ||||

| gi|53791223 | FINC | Fibronectin 1 | 0.403 | 1 | −2.094 | ||||

| gi|55957730 | D3DVE6 | WD repeat domain 42A | 0.404 | 1 | −2.084 | ||||

| gi|48429194 | UFO | Tyrosine-protein kinase receptor UFO precursor (AXL oncogene) | 0.407 | 1 | −2.351 | ||||

| gi|12804489 | MELPH | Melanophilin | 0.412 | 1 | −2.318 | ||||

| gi|178743 | APEX1 | Apurinic endonuclease | 0.415 | 1 | −2.347 | ||||

| gi|56204680 | Q5T8R3 | Solute carrier family 16 (monocarboxylic acid transporters), member 1 | 0.418 | 1 | −3.006 | ||||

| gi|15488917 | PRKCSH | Protein kinase C substrate 80 K-H | 0.420 | 1 | −2.311 | ||||

| gi|57209070 | Q5JTE2 | RP3-337H4.4 | 0.421 | 1 | −1.994 | ||||

| gi|34531906 | Unnamed protein product | 0.425 | 1 | −2.280 | |||||

| gi|48255937 | CD44 | CD44 antigen isoform 2 precursor | 0.425 | 1 | −2.946 | ||||

| gi|1575607 | FUBP2 | FUSE binding protein 2 | 0.431 | 1 | −2.901 | ||||

| gi|6969149 | MCM3 | MCM3 minichromosome maintenance deficient 3 (S. cerevisiae) | 0.436 | 1 | −2.069 | ||||

| gi|39753961 | IQGA3 | IQ motif containing GTPase-activating protein 3 | 0.444 | 1 | −2.160 | ||||

| gi|18860900 | PTPRJ | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, J precursor | 0.448 | 1 | −2.136 | ||||

| gi|56204524 | ARPC5 | Actin-related protein 2-3 complex, subunit 5, 16 kDa | 0.449 | 1 | −2.764 | ||||

| gi|55665466 | D3DV57 | Novel protein (FLJ21919) | 0.451 | 1 | −1.985 | ||||

| gi|55665798 | UBP2L | Ubiquitin-associated protein 2-like | 0.471 | 1 | −2.000 | ||||

| gi|50949942 | S4A7 | Hypothetical protein | 0.477 | 1 | −1.966 | ||||

| gi|1184699 | SYYC | Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase | 0.479 | 1 | −2.149 | ||||

| gi|30268334 | CD44 | Hypothetical protein | 0.479 | 1 | −2.148 | ||||

Protein is included if at least half of the biologic z-score values are ≥1.960σ (indicated by bolding) and there are no major disagreements between technical replicates A and B.

2-D HPLC runs; A and B refer to 2 technical replicates of a 3rd biologic sample; 2DLC1 and 2DLC2 refer to the first and seconnd 2-D HPLC runs.

L/H ratio refers to the geometric mean of all log2 L/H values for each given gi number, expressed as relative protein quantity in infected cultures.

Z-scores from multiple SDS-PAGE fractions are collapsed into a single most significant value for clarity.

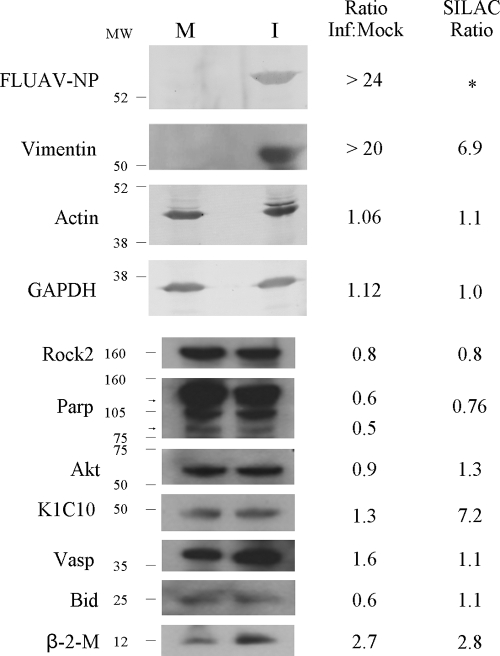

Validation of SILAC ratios by Western blotting.

To confirm some of the SILAC-determined protein ratios, we analyzed selected proteins in infected and mock-infected cells by immunoblotting. Although there are a limited number of appropriate immunological reagents for most of the SILAC-measured proteins we identified in this study, we confirmed that vimentin and β-2-microglobulin were upregulated (Fig. 3). A number of proteins usually used as Western blot loading controls, such as GAPDH, which was found in every experiment at an L/H ratio of 1.1 ± 0.1 (mean ± standard deviation), and actin, with a measured average L/H ratio of 1.1, were present at equivalent levels in infected and mock-infected cells, as measured also by immunoblotting. Most other tested proteins were suggested by SILAC analysis to not be significantly regulated (L/H ratio of 1.0 ± 0.3 and z-scores within 0.5σ of 0.0), and these relative levels were generally confirmed by Western blotting. Of note, two major PARP bands in Fig. 3 have Mr values of 80 and 110 kDa, and immunoblots suggest that they are slightly downregulated 0.5- to 0.6-fold. PARP was returned as a number of gi identifications, including gi|337424 and gi|22902366, which had L/H ratios of about 0.76 and z-scores of approximately −0.2. We also tested the quantity of keratins, many of which appeared to be highly significantly upregulated in numerous SILAC experiments (L/H ratios of >5.0 and z-scores >3.0). However, immunoblotting indicated nearly equivalent amounts of cytokeratin 10 in infected and mock-infected cells. Thus, except for keratins, which are usually considered contaminants in MS experiments, immunoblotting validated the SILAC-determined values.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot analysis of host and influenza virus proteins in mock-infected (M) and influenza virus strain A/PR/8/34 (H1N1)-infected (I) A549 cells. Cells were harvested and lysed with 0.5% NP-40 detergent, nuclei were removed, and cytosolic fractions were dissolved in SDS electrophoresis sample buffer, resolved in s 5 to 15% minigradient SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF, and probed with various antibodies. Bands were visualized and intensities measured with an Alpha Innotech FluorChemQ MultiImage III instrument. Molecular weight standards are indicated at the left and ratios of each protein (infected divided by mock infected) are indicated for each protein at the right, along with SILAC-measured ratios (far right). *, no viral proteins were measured by SILAC because they were not present in mock-infected samples.

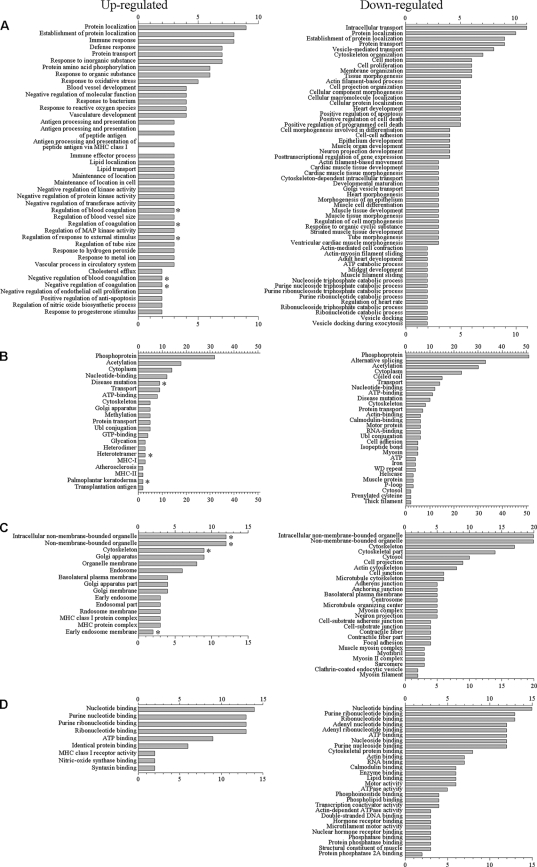

Proteins upregulated by influenza virus infection are associated with responses to stimuli and protein binding, localization, and transport, whereas downregulated proteins are associated with alternative splicing, nucleotide and nucleoside activities, catabolic and hydrolase functions, and cell adhesion.

Proteins, and their levels of regulation, were analyzed by a variety of means. Protein gi numbers were imported into Uniprot (http://www.uniprot.org/) and converted into HUGO nomenclature committee (HGNC) identifiers. Several hundred gi numbers could not be mapped to HGNC identifier numbers, and several hundred gi numbers were collapsed to about half as many genes. This resulted in about 3,900 unique HGNC IDs for the data set (see Table ST-1 in the supplemental material). Several of the different gi numbers that were collapsed into fewer genes may represent different isoforms of the same genes. The HGNC IDs that represented various sets of significantly upregulated and downregulated proteins at different confidence intervals of 95, 99, and 99.9% were then separately imported into DAVID (19, 41), gene identifications were converted to Entrez gene IDs by that suite of programs, and ontological functions were determined by GOTERM, PANTHER, and KEGG. We also analyzed the upregulated proteins at each confidence interval after removing keratins from the data sets. Biological processes, functional annotations, molecular functions, and cellular components identified at 95% confidence are depicted in Fig. 4, and data at all confidence levels are shown in Table ST-2 in the supplemental material.

FIG. 4.

Gene ontology analyses of upregulated and downregulated proteins. The proteins identified in Tables 2 and 3, as well as nonkeratin proteins in Table 2, were imported into the DAVID gene ontology suite of programs at the NIAID, gene identifications were converted by that program, and ontological functions were determined by GOTERM. (A) Biological processes; (B) functional annotations; (C), cellular components; and (D) molecular functions. The numbers of identified genes associated with each group, identified at a confidence level of 95% are illustrated. *, processes, functions, and cellular components that are removed when keratins are excluded from the input gene list. Additional lists of functional groups, processes, and components at different confidence limits are indicated in Table ST-2 in the supplemental material.

Upregulated proteins were assigned to 41 GOTERM biological processes at 95% confidence (Fig. 4A, left; see also Table ST-2 in the supplemental material) that included immune and defense responses, responses to stress and to virus, MHC-I-mediated immunity pathways, and protein localization and transport. These upregulated proteins were also assigned to 21 functional groups (Fig. 4B) (including acetylation, cytoplasm, MHC-I and -II, phosphoprotein, and nucleotide binding), 19 cell component groups (Fig. 4C) (including cytoplasm, Golgi, and organelle membranes), and 9 molecular functions (Fig. 4D) (most notably nucleotide and ribonucleotide binding). PANTHER also assigned upregulated proteins to mRNA transcription regulation, cell structure, molecular binding, and MHC-I mediated immunity pathways (data not shown). Rerunning the analysis after removing keratins led to the removal of blood coagulation and cytoskeletal groups from the above categories. Downregulated proteins were assigned to 56 biological processes at 95% confidence (Fig. 4A, right; see also Table ST-2 in the supplemental material) that included localization determinants, transport, and positive regulation of apoptosis. These downregulated proteins were also assigned to 28 functional groups, including acetylation, phosphoproteins, and alternative splicing (Fig. 4B), 27 cell component groups (Fig. 4C) (including nonmembrane-bounded organelles and adhesion-related components), and 28 molecular functions (Fig. 4D) (including molecular binding and ATPase activity). PANTHER also assigned downregulated proteins to MHC-II-mediated immunity, nucleoside, nucleotide, and nucleic acid metabolism, adhesion, and cytoskeleton regulation. KEGG assigned proteins that had been downregulated >100-fold to a number of cell pathways, including focal adhesion, cell adhesion, and regulators of the actin cytoskeleton.

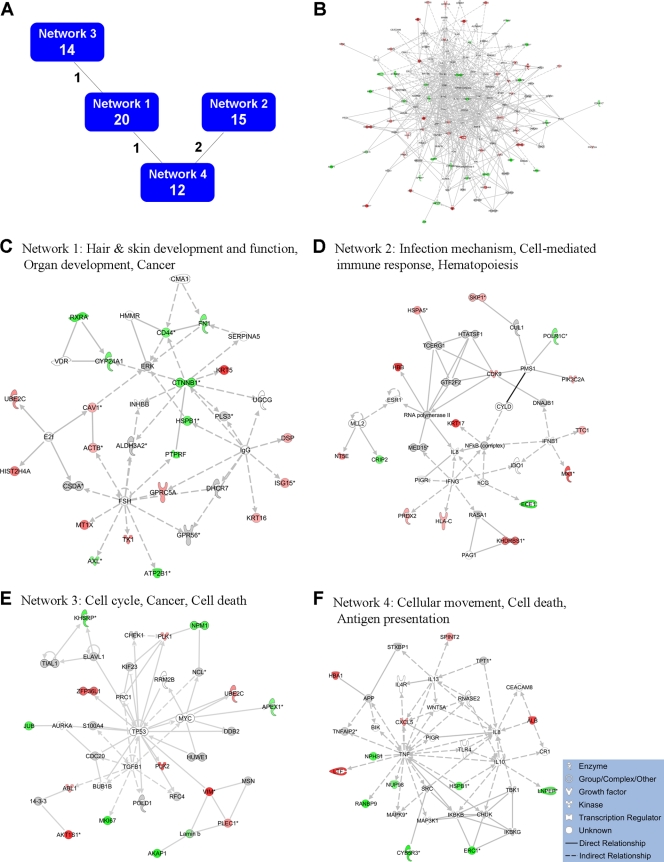

Protein gi numbers and levels of regulation were also imported into the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) tool, and interacting pathways were constructed. A total of 18 pathways were identified at a confidence level of 95% or greater. Four of these pathways, each with 12 or more “focus” members (significantly up- or downregulated proteins), shared common members (Fig. 5A), and it was possible to build a single, merged pathway (Fig. 5B). The other 14 pathways consisted of several proteins but contained only a single focus protein (data not shown). The 4 networks that contained 12 or more focus members corresponded to hair, skin, and organ development, cell cycle, cell death, cancer, infection mechanisms, and antigen presentation pathways (Fig. 5C to F). Proteins present in the pathways and identified in our analyses as upregulated are depicted in shades of red and include Mx1, LTF, and VIM; proteins present in the pathways and identified as downregulated are shown in green and include ERC1, L1CAM, and CTNNB1; proteins present in the pathways and identified in our analyses but neither up- nor downregulated are depicted in gray and include SMAD3, SCARB1, and RNA Pol II; and proteins known to participate in the pathways but not identified in our analyses are shown in white and include MYC, MAP3K1, and TP53. IPA analyses identify interaction nodes. For example, several of the highly upregulated proteins interact with a few other proteins, but some, such as VIM and KHDRBS1, interact with four or more. Similarly, a few of the downregulated proteins interact with few partners, but several, including CTNNB1, appear as interaction “hubs.” We identified numerous other interaction hubs, such as SCARB1, CHUK, HSPB1, SMAD3, CTNND1, TIAL1, and SMAD2, which were not themselves significantly altered but which interacted with several differentially regulated proteins.

FIG. 5.

Molecular pathways of regulated proteins. Proteins and their levels of regulation were imported into the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) tool, and interacting pathways were constructed. (A) Overview of 4 networks identified at 95% confidence, each of which contained 10 or more “focus” molecules (molecules significantly up- or downregulated). Each box contains an arbitrary network number (upper) as well as the number of focus molecules within the network (lower bolded number). Lines connecting networks indicate the number of focus molecules present in each attached network. (B) Merged network, containing all molecules present in each of the four individual networks. (C to F) Individual networks with pathway names indicated. Solid lines, direct known interactions; dashed lines, suspected or indirect interactions; red, significantly upregulated proteins; pink, moderately upregulated proteins; gray, proteins identified but not significantly regulated; light green, moderately downregulated proteins; dark green, significantly downregulated proteins; white, proteins known to be in the network but not identified in our study. Molecular classes are indicated in the legends.

DISCUSSION

A number of studies have defined the cellular networks that are required or manipulated by influenza infection by use of genome wide RNAi screens, mRNA microarray screens, and yeast two-hybrid assay, to identify 1,449 protein targets for further analysis (73). Because viral infection leads to both qualitative and quantitative effects on host gene expression and function, we have complemented these previous studies by deriving a quantitative proteomic assessment of influenza infection to further define the effects of influenza virus infection on host functions. Whereas a variety of quantitative proteomic methods have been employed to examine perturbations in host protein quantities after virus infection, quantification of host protein responses after influenza virus infection had only previously been reported after 2-D DIGE analysis, which identified 25 or fewer proteins (48, 72). Here, we present the application of SILAC and demonstrate several advantages relative to this earlier approach. While 2-D DIGE is excellent for resolving protein species that differ in posttranslational modification, such as phosphorylation, it suffers several drawbacks, including a relatively low dynamic range and sample overloading (13), variability in labeling efficiency, as well as labeling deficits for proteins lacking lysine or cysteine residues, and is unsuited for proteins at the extremes of molecular weight, alkalinity, or hydrophobicity (59). Finally, in-gel digestion methods are usually less efficient in allowing peptide identification than in-solution digestion, which may partially explain why earlier studies identified less than 25 differentially regulated proteins (48, 72).

We used nongel-based quantitative proteomic methods and identified and measured >120,000 SILAC-labeled peptides, which arose from >5,000 host protein pairs. Almost 4,700 cytosolic protein pairs were identified based upon stringent criteria that required two complete L and H tryptic peptides and protein identification confidence of 99% or greater. Of these, statistical tests indicated that 280 proteins (127 upregulated and 153 downregulated) were reliably identified as significantly regulated at the 95% confidence limit. Upregulated proteins included those involved in stress responses, regulation of mRNA transcription, translation initiation, cell structure, molecular binding, and MHC-I-mediated immunity pathways. Downregulated proteins include those involved in alternative splicing, MHC-II-mediated immunity, nucleoside, nucleotide, and nucleic acid metabolism, adhesion, and cytoskeleton regulation. Several proteins (described in more detail below) had been previously described in other studies, but our application of SILAC in combination with multiple purification and fractionation schemes identified more than 10 times as many differentially regulated proteins as have previously been identified in influenza virus infections.

A small number of host proteins have been reported as upregulated by influenza virus infection in earlier quantitative proteomic studies. Keratins, including cytokeratin 10, have repeatedly been shown upregulated as much as 50-fold by A/PR/8/34 infection (3-5, 48, 72). Alterations in these proteins could be expected to have dramatic effects upon intermediate filaments and cellular organization, both of which play significant roles in enveloped virus intracellular transport and budding. However, keratins are also common contaminants in MS experiments, and our Western blot assays suggest that this may have been the case in these studies, as the highly elevated L/H ratios could result from sample contamination with normal unlabeled keratins. This possibility could be tested in follow-up studies by infecting the H-labeled cells, which, if keratins are contaminants, would result in very low L/H ratios. A larger number of genes have been reported affected by influenza virus infection by microarray studies (6, 30). We attempted to correlate our results with these previous transcriptomic analyses and found generally good correlation, as has also been reported in a transcriptomic/semiquantitative proteomic comparison (6). Most of the 22 genes whose products we measured and for which transcriptomic data are readily available correlated well; only 3 were negatively correlated, such that microarrays indicated that STAT3, SNX6, and VIM mRNA levels were upregulated, not affected, and decreased (30), respectively, whereas SILAC indicated that the corresponding proteins were slightly downregulated, upregulated, and highly upregulated, respectively (data not shown).

The myxovirus resistance host proteins Mx1 and Mx2 have been identified as upregulated by influenza infection in several studies, including microarray (30), and in more recent proteomic analyses (6, 72). These interferon (IFN)-induced, large GTPase dynamin-like Mx proteins are important antiviral proteins, particularly against RNA viruses (37, 38). “Semiquantitative” analyses of macaque lungs infected by recombinant influenza virus A/Texas/36/91 (H1N1) suggested an approximate 3-fold upregulation in this protein, and quantitative 2-D DIGE of A549 cells infected with PR8 showed about 5- and 10-fold upregulation at 48 and 72 h postinfection (72). Although MxA (the mouse homolog of Mx1) was apparently not detected at 24 hpi in A549 cells in the earlier study, these values are in good agreement with our measurements of ∼5- to 14-fold increases in Mx proteins by PR8 infection in the current study. Vester et al. (72) reported that nucleobindin was upregulated approximately 2-fold by 72 hpi, although it either was not detected or was not upregulated at earlier time points in their study. Our results indicate that nucleobindins were moderately affected but not significantly at 24 hpi (see Table ST-1 in the supplemental material). In addition, Vester et al. reported proteasome activator hPA28 subunit β was also upregulated about 2-fold by 72 hpi, although it either was not detected or was not upregulated at earlier time points in their study. Our results identified a larger number of proteasome-related molecules and indicated that proteasome inhibitor subunit 1 isoform 1 was upregulated about 2.2-fold, proteasome subunit α type 8 was downregulated nearly 3-fold, and numerous other proteasome activators, including PA28β (upregulated 1.2-fold) were only moderately altered at 24 hpi. Reduction in specific host proteins may be mediated by enhanced proteasomal protein production and activity.

Our study identified many more upregulated and downregulated proteins. Notably, some of these have not been reported in previous quantitative influenza virus infections but have been reported as regulated by other viruses. For example, the intermediate filament protein vimentin, seen upregulated to about 7-fold in our study (Table 2), has been reported increased by other negative-sense RNA viruses, including rabies virus (76), and the positive-sense RNA virus hepatitis C (50) but was reported downregulated by West Nile virus (57), HIV (60), infectious bursal disease virus (79), and human papillomavirus type 16 (44). In addition, dermcidin, a sweat gland-produced antibiotic (51, 63) that activates keratinocytes (54) and had been seen upregulated by HIV infection (58), was also upregulated almost 10-fold in our study, suggesting that it may be activated by a broad range of infectious agents. Other notable innate immunity molecules that we found upregulated include IFITM2, B2M, and the ISG15 ubiquitin-like modifier that is involved in IFN-induced inactivation of viral NS1 functions (78).

Most previous quantitative proteomic analyses identified very few influenza virus-induced downregulated proteins. This might be expected because 2-D DIGE is generally limited to analysis of high-abundance proteins (13, 59, 72). This would not be a limitation if barely detectable proteins are upregulated above the detection threshold, but downregulation of barely detectable proteins below the detection limit might preclude their inclusion in the analyses. The downregulated proteins we identified are involved in a very large number of cellular processes (Fig. 4) and include, most notably, those involved in MHC-II mediated immunity, protein folding and modification, nucleoside, nucleotide, and nucleic acid metabolism, adhesion, and cytoskeleton regulation. Several notable proteins were detected and measured multiple times and found to be significantly downregulated. These include β-catenin, found downregulated ∼3-fold, a key component of cell adhesion pathways and a target for the ubiquitin proteasome pathway (reviewed in reference 1) that also is involved in regulating lung development (18). Downregulation of the β-catenin protein may avoid IFN induction through the WNT/β-catenin pathway (64). In addition, the WD40 protein, which is involved in signal transduction, molecular binding, particularly with β-catenin, and numerous other processes and is targeted by retroviral insertion (42) and required to aid herpesvirus replication (66), was found downregulated ∼100-fold in our study.

Influenza infection is critically dependent on host gene expression because there is a strict requirement for host POL II transcripts as a source of capped oligonucleotides for priming viral transcription, as well as a requirement for splicing machinery to generate NEP and M2 spliced transcripts (reviewed in reference 24). Therefore, influenza virus must maintain and regulate host transcriptional activities to optimize viral replication via the enhanced production of canonical transcription factors, such as TFIIB, TFIIF1, and TFIID7, while downregulating most of the other typical POL II transcription factors. Thus, influenza virus may modulate expression of host POL II transcripts to favor viral replication processes, such as the association of influenza polymerase with POL II early in transcription that may be involved in accessing newly formed capped transcripts as they are produced and concomitantly inhibiting elongation (10, 25). The general transcription factor TFIIA, which regulates RNA POL2-dependent DNA transcription (40), was downregulated ∼4-fold. This protein would not be expected to be needed by an RNA virus that uses no DNA intermediates in its replication; however, downregulation of host DNA-dependent transcription could be important for host resistance genes such as IFN and IFN-inducible genes (36). TACC2 (transforming, acidic coiled-coil-containing protein 2 isoform a), a centrosomal-microtubule-associated protein (31) involved in protein translation and RNA processing and transcription (68), was found downregulated >12-fold. Interestingly, this protein is targeted for degradation by SV40 virus (70), suggesting that disparate viruses may benefit from targeting this host protein.

On the other hand, influenza virus has mechanisms for downregulation of gene expression that involve inhibition of polyadenylation through binding of NS1-viral polymerase complexes to cleavage- and polyadenylation-specific factor 30 (47) that serves to block host gene expression. This blocks the expression of host inhibitors, including interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (which were reduced in PR8-infected A549 cells) (Table 3), and thus a balance of host inhibition must be achieved while maintaining host gene transcription of mRNA and protein products employed for replication. Influenza NS1 protein also binds eIF4G1 and PABP1 translation initiation factors to favor influenza protein translation (9, 17, 69) relative to host translation. It is possible that the reduction in eIF4G1 as well as many ribosomal protein components may be involved in the mechanisms for preferential viral gene expression at the expense of host gene expression.

Influenza infection also enhances immune evasion by directing the incorporation of MHC-I into ganglioside-rich microdomains that function to recruit cellular inhibitors of NK cell binding and function (reviewed in reference 14), which is consistent with an upregulation of MHC-I in A549 cells (Table 2; Fig. 4). The downregulation of several components of the MHC-I antigen presentation machinery could also be expected to reduce influenza antigen presentation on the surface of infected cells to result in immune cell-mediated attack. The upregulation of ubiquitin activities as well as the IFN-induced viral antagonist, Mx1, may be an interrelated feature of Mx1 control because Mx1 is found in nuclear promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) bodies in infected cells that are also sites of ubiquitin degradation (26). We found Mx1 upregulated 14-fold (z-score > 5) in our nuclear fractions, which, as explained earlier, was not further analyzed in the present study (data not shown). With respect to the cytoskeleton components, influenza virus uses actin interactions of NP protein for nucleocytoplasmic transport of RNP (21, 65), and the multiple instances of increases in actins and related components may be instrumental in favoring viral replication. Other upregulated proteins listed in Table 2 and downregulated proteins listed in Table 3 could be hypothesized to have been affected by infection but will not be discussed further at this time, as they await further validation.