Abstract

AD (Alzheimer’s disease) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease of unknown origin. Despite questions as to the underlying cause(s) of this disease, shared risk factors for both AD and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease indicate that vascular mechanisms may critically contribute to the development and progression of both AD and atherosclerosis. An increased risk of developing AD is linked to the presence of the apoE4 (apolipoprotein E4) allele, which is also strongly associated with increased risk of developing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Recent studies also indicate that cardiovascular risk factors, including elevated blood cholesterol and triacylglycerol (triglyceride), increase the likelihood of AD and vascular dementia. Lipids and lipoproteins in the circulation interact intimately with the cerebrovasculature, and may have important effects on its constituent brain microvascular endothelial cells and the adjoining astrocytes, which are components of the neurovascular unit. The present review will examine the potential mechanisms for understanding the contributions of vascular factors, including lipids, lipoproteins and cerebrovascular Aβ (amyloid β), to AD, and suggest therapeutic strategies for the attenuation of this devastating disease process. Specifically, we will focus on the actions of apoE, TGRLs (triacylglycerol-rich lipoproteins) and TGRL lipolysis products on injury of the neurovascular unit and increases in blood–brain barrier permeability.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, apolipoprotein E (apoE), astrocyte, endothelial cell, lipoprotein, triacylglycerol-rich lipoprotein (TGRL), vascular system

INTRODUCTION

Vascular dysfunction and endothelial injury have come to be recognized as key mediators in the development of ASCVD (atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease). ASCVD is defined as a thickening of arterial walls due to accumulation of fatty material and macrophages. Atherosclerosis affects medium-large arteries and similar disease processes may also affect the smaller arteries of the brain. Although cerebrovascular disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, research into the fundamental mechanisms underlying this problem has been relatively slow coming, compared with the emphasis that has been placed on atherosclerosis research in the last several decades.

Despite the apparent differences between the peripheral vasculature and the cerebrovasculature, many of the same mechanisms, or slight variants thereof, may also contribute to endothelial injury in the brain. Vascular dysfunction in the brain has long been recognized as a contributing factor to the development of stroke and vascular dementia. More recently, evidence has accumulated that suggests that the development of AD (Alzheimer’s disease) may also be strongly related to underlying vascular problems. Whether this vascular dysfunction actually causes AD or merely contributes to the development of the disease or worsens the disease processes once they are underway, it is worthwhile to investigate how the vasculature and its related blood lipids, lipoproteins and vascular Aβ (amyloid β) promote AD. The present review will focus on the actions of apoE (apolipoprotein E), TGRLs [triacylglycerol (triglyceride)-rich lipoproteins] and TGRL lipolysis products on injury of the neurovascular unit and increases in BBB (blood–brain barrier) permeability.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF AD

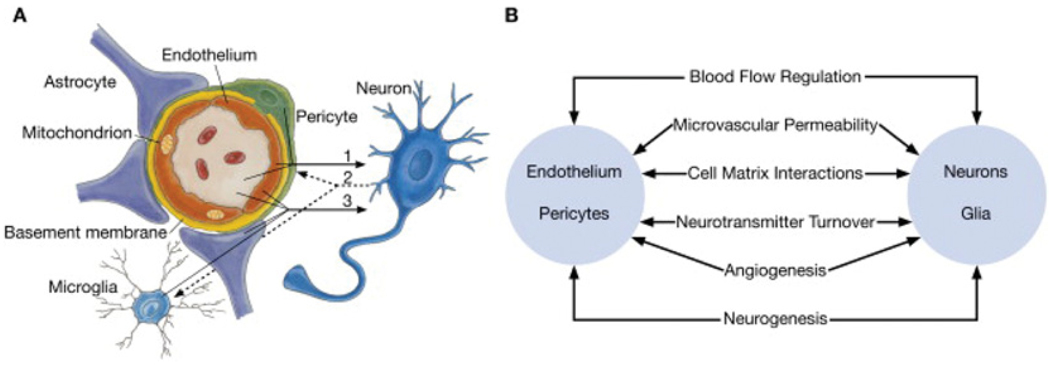

Dementia is the progressive decline in cognitive function due to damage or disease of the brain, and is distinct from the slowing of cognitive function that is expected with normal aging. The two most common causes of dementia are AD and vascular dementia [1–4]. For the more common form of late-onset AD, only one susceptibility allele has so far been identified, ε4 (E4) of the apoE gene [5]. In AD, progressive brain atrophy is observed, principally in the temporoparietal cortex, together with an inflammatory response of neurons and astrocytes, as well as deposition of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Astrocytes are a subtype of glial cells in the brain that are ‘star shaped’ and are key cells in the maintenance of the BBB, as their endfeet surround endothelial cells (Figure 1) [6–11]. In addition, the many arm-like processes of astrocytes envelop neurons. Astrocytes are associated with senile plaques in the brain and inflammation of microvascular endothelial cells, and astrocytes are common features of AD [12–22].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the neurovascular unit.

(A) Endothelial cells and pericytes are separated by the basement membrane. Pericyte processes sheathe most of the outer side of the basement membrane. At points of contact, pericytes communicate directly with endothelial cells through the synapse-like peg-socket contacts. Astrocytic endfoot processes unsheathe the microvessel wall, which is made up of endothelial cells and pericytes. Resting microglia have a ‘ramified’ shape. In cases of neuronal disorders that have a primary vascular origin, circulating neurotoxins may cross the BBB to reach their neuronal targets, or pro-inflammatory signals from the vascular cells or reduced capillary blood flow may disrupt normal synaptic transmission and trigger neuronal injury (arrow 1). Microglia recruited from the blood or within the brain and the vessel wall can sense signals from neurons (arrow 2). Activated endothelium, microglia and astrocytes signal back to neurons, which in most cases aggravates the neuronal injury (arrow 3). In the case of a primary neuronal disorder, signals from neurons are sent to the vascular cells and microglia (arrow 2), which activate the vasculo–glial unit and contributes to the progression of the disease (arrow 3). (B) Co-ordinated regulation of normal neurovascular functions depends on vascular cells (endothelium and pericytes), neurons and astrocytes. Reprinted from Neuron volume 57, Zlokovic, B.V., The blood–brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders, pp. 178–201, Copyright (2008), with permission from Elsevier (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/08966273).

The neurovascular unit, including brain microvascular endothelial cells and astrocytes, regulates BBB permeability. In a study examining human subjects with mild-to-moderate AD, the BBB wasfound to be a significant modifier of AD progression over 1 year [23]. Increased BBB permeability plays an important role in the promotion of AD by allowing potentially neurotoxic substances, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines and lipids, access to the CNS (central nervous system) [24–28].

CEREBROVASCULAR Aβ

The physiology and pathophysiology of the neurovascular unit in AD may well be influenced by interactions with cerebrovascular Aβ. Aβ results from the proteolytic processing of APP (amyloid precursor protein), which is found in various cell types throughout the body, including cells of the brain. Proteolytic cleavage of APP by β-secretase and γ -secretase results in two forms of Aβ: Aβ40 [Aβ-(1–40)] and Aβ42 [Aβ-(1– 42)] [29]. Although Aβ is a physiological component of plasma, the exact origin of plasma Aβ remains unknown. Peripheral sources, such as blood platelets, may prove to be important sources of plasma Aβ [30]. It has been suggested that, regardless of the primary origin of plasma Aβ, it may play an important role in the cerebrovascular pathology associated with AD. Higher levels of plasma Aβ42 were found in AD patients and in those subjects who would eventually develop AD compared with those who did not develop AD [31–33]. Additionally, mutations associated with early-onset familial AD result in elevated levels of extracellular Aβ42 [33].

The neuropathological characteristics of AD usually include sporadic CAA (cerebral amyloid angiopathy), even in the absence of underlying ASCVD, with some studies reporting up to 80% of AD patients exhibiting CAA to at least a minor degree [34,35]. Studies suggest that CAA severity increases with progressing AD [36]. The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study demonstrated that men with both CAA and AD had greater cognitive impairment than those individuals with either CAA or AD [37]. Numerous pathological, cell culture and animal model studies have demonstrated the deleterious effects of Aβ peptides and CAA on cerebral microvessels [38]. This damage includes histological and ultrastructural abnormalities of cerebrovascular walls in CAA [39]. Reduced adhesion of vascular smooth muscle cells in response to treatment with Aβ [40] and impaired function of vascular smooth muscle cells in transgenic mouse models of CAA [41] were also observed. Additional in vitro studies demonstrated that wild-type and mutant forms of Aβ have anti-angiogenic and vasoactive properties [42–44]. CAA-related vascular abnormalities in both transgenic mouse models and AD patients may also contribute to capillary occlusion and altered blood flow [45,46].

The detrimental effects of plasma Aβ and amyloid angiopathy on components of the cerebrovasculature suggest that cerebrovascular Aβ may be intimately related to the progression and development of AD through vascular pathways. The combined influences of cerebrovascular Aβ, plasma lipoproteins and apoE may form a constellation of negative interactions that lead directly to vascular dysfunction. Although conflicting studies debate the usefulness of plasma Aβ as a biomarker predictive of AD [32], the potential contribution of cerebrovascular Aβ to the vascular pathologies associated with AD merits continued attention.

APOE STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

Although the underlying cause of AD remains unknown, an increased risk of developing the disease is linked to the presence of the apoE4 allele. ApoE is a 34 kDa glycoprotein that has many functions, including assembly, processing and removal of plasma lipoproteins [47], neuronal repair, dendritic growth and anti-inflammatory properties [48]. It is a component apolipoprotein of VLDLs (very-low-density lipoproteins), IDLs (intermediate-density lipoproteins), chylomicrons, HDLs (high-density lipoproteins) [49] and LDLs (low-density lipoproteins) [50]. ApoE serves as a ligand for LDLRs (LDL receptors) and, through its interaction with these receptors, participates in the distribution of cholesterol and other lipids among various cells of the body [51]. In humans, there are three common isoforms of apoE: apoE2, apoE3 and apoE4, with apoE3 being the most common isoform [52–60].

ApoE contains a 22-kDa N-terminal domain (residues 1–191) and a 10-kDa C-terminal domain (residues 222–299) connected by a protease-sensitive loop [61]. The N-terminal domain contains the LDLR-binding region (residues 136–150 in helix 4) and the C-terminal domain has a high affinity for lipid and is responsible for lipoprotein-lipid binding [62]. ApoE4 differs from apoE3 by the presence of an arginine residue at position 112, rather than a cysteine residue at the same position in apoE3 [63]. ApoE in the blood is generated by the liver, intestine and macrophages, whereas apoE in the brain is generated by glial cells, including astrocytes and microglia [64].

Among the human isoforms, apoE4 shows a unique domain interaction where the arginine residue at the 112 position induces an interaction of Arg61 in the N-terminal domain with Glu255 in the C-terminal domain, a feature thought to be responsible for the preferential association of apoE4 with VLDLs in blood [65,66]. Approx. 40– 65% of individuals with AD have at least one copy of the E4 allele. The E4 allele is present in approx. 25% of the U.S. population [67–69] and is strongly linked to an increased risk of the development of AD and atherosclerosis complications [70–72]. ApoE4 is reported to have effects that promote amyloid deposition, neurotoxicity, oxidative stress and neurofibrillary tangle formation [48], all of which are pathophysiologically linked to AD. Clinical trials also suggest that apoE4 plays key causative roles in AD. In a postmortem study, brains from patients with advanced AD exhibited plasma proteins, such as prothrombin, in the microvessels, and suggested that increased permeability of the BBB may be more common in patients with at least one E4 allele [73]. These findings indicate that the E4 allele is an important determinate of AD.

APOE AND MODULATION OF NEURAL AND VASCULAR TISSUE RESPONSE TO INJURY

ApoE4 is associated with increased brain inflammation. Previous studies have shown that apoE4 can undergo pro-teolysis and cause mitochondrial damage [74], increase brain inflammation found in apoE4-expressing mice in response to LPS (lipopolysaccharide) [75] and facilitate the deposition of oligomeric Aβ as amyloid to a greater extent than apoE3 [76]. Our previous study showed that apoE4 increased, and apoE3 decreased, TNF (tumour necrosis factor)-α-induced human aortic endothelial cell injury [77]. These studies indicate that, in addition to being a marker of increased risk for AD and ASCVD, apoE4 could directly generate microvascular and neural injury.

In contrast, apoE3 is associated with reduced brain inflammation [78,79]. Microglial activation by APP was reduced by apoE3 [80]. In addition, apoE3 interacts with Aβ via an apoE-receptor-mediated process to inhibit neurotoxicity and neuroinflammation, a process possibly related to binding and clearance of apoE3–Aβ oligomer complexes. Our findings suggest a role for apoE3 to prevent inflammation and balance the intracellular redox state in injured human aortic endothelial cells [77]. Thus these results suggest that apoE3 protects against and apoE4 promotes AD and ASCVD.

LIPIDS AND APOE CONFORMATION

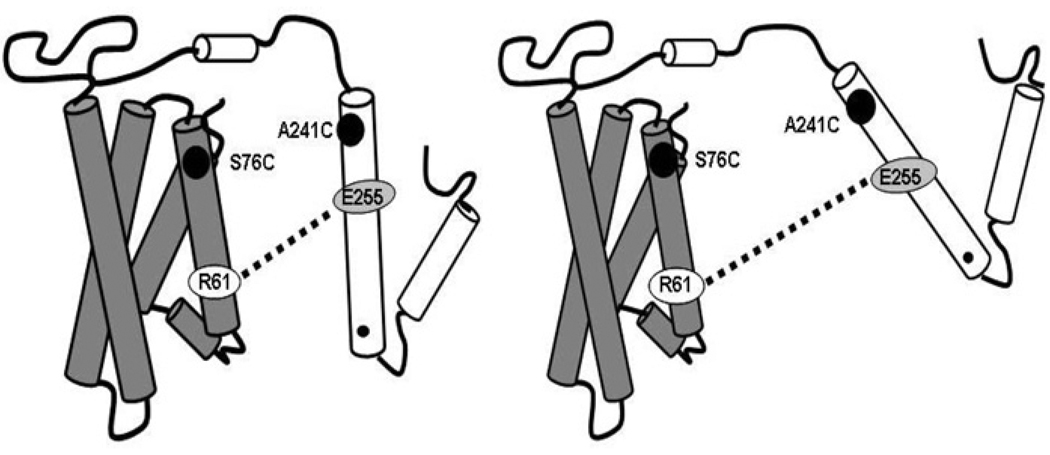

Our studies indicate that the postprandial state, and specifically TGRL lipolysis products, can have a profound effect on apoE4 conformation to increase formation of a more linear species of apoE4 [82], which may potentially have an impact on the pathogenesis of AD (Figure 2) [82]. Regardless of the plasma triacylglycerol levels, consistent conformational changes were observed as a result of interactions between TGRL lipolysis products and apoE4. In contrast, TGRL lipolysis products did not cause linear conformation changes in apoE3. Using thrombin-accessibility assays, other studies have shown that binding of high triacylglycerol-containing VLDLs to macrophages was related to differences in the conformation of apoE [83–86], although the specific conformational change was not known. These studies, among others [72,75,82,87,88], indicate that lipids can have dramatic effects on apoE4 conformation and binding to cells. In the presence of varying plasma lipid levels, similar apoE4 conformational and cell interaction effects were observed, which suggests that comparable mechanisms at the level of the lipoprotein may be important in apoE4 individuals irrespective of their overall lipid levels.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of apoE4 before and after a moderately high-fat meal.

An apoE4 mutant was employed to study the domain interaction of the apoE4 mutant using EPR (electron paramagnetic resonance) spectroscopy. The dotted line represents a salt bridge between Arg61 (R61) and Glu255 (E255) of apoE4 showing a domain interaction. In this mutant, the serine residue at position 76 and the alanine residue at position 241 were mutated to cysteine and subsequently labelled with a nitroxyl spin label. The left-hand panel represents the structural conformation of apoE4 during the fasting state, and the right-hand panel represents the conformation in the postprandial state. ApoE4 had a reduced domain interaction during the postprandial state, implying a more linear protein [82]. The left-hand Figure was reproduced with permission from [82]. Copyright (2006) American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. The right-hand Figure was reproduced with permission from [222]. Copyright (2010) American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

It is unknown whether increased VLDL particle fluidity and linearization of apoE4 resulting from VLDL lipolysis products acts to increase apoE4 binding and injury to brain microvascular endothelial cells. This potential mechanism of injury to endothelial cells may increase BBB permeability, enabling TGRL lipolysis products to have increased access to the brain, where they may promote astrocyte and neuronal injury that could initiate and perpetuate AD.

Other studies have indicated that Aβ clearance and degradation mechanisms in the brain are dramatically affected by the lipidation state of apoE [89–94]. Using real-time in situ microdialysis methods in mice, Bell et al. [95] showed that Aβ clearanceacross the BBBisdecreased when Aβ associates with poorly lipidated apoE3, and is almost completely blocked when Aβ associates with lipidated apoE3. Following the same experimental methods, Deane et al. [96] showed that lipidation of the apoE2, apoE3 or apoE4 isoform significantly reduced the transport of apoE–Aβ complexes across the BBB. The extent of this effect was dependent on the specific isoform,where apoE4–Aβ transport was most significantly disrupted, compared with apoE3–Aβ or apoE2–Aβ complexes [96]. Interestingly, lipidation of apoE appears to have opposing effects on Aβ degradation in the brain. Additional studies have shown that strategies to increase apoE lipidation reduce amyloid burden in animal models. Overexpression of ABCA1 [ABC (ATP-binding-cassette) family A1] in the brain promotes the formation of lipidated apoE and reduces the formation of amyloid plaques [97,98]. LXR (liver X receptor) agonists have also been shown to have a beneficial effect on amyloid burden in the brain. LXRs are involved with the removal of cholesterol by ABC transporters and the transfer of this cholesterol to apolipoproteins such as apoE and apoAI (apolipoprotein AI). Stimulation of these receptors by LXR agonists resulted in reduced Aβ levels and enhanced apoE lipidation [92,99–101]. Furthermore, the molten globule form of apoE4, which is a partially unfolded reactive intermediate, has been associated with increased pathogenicity [74,102]. These studies indicate that the lipidation state and conformation of the apoE isoforms are important determinants of Aβ homoeostasis in the brain; however, the exact mechanisms by which this occurs are not well understood.

LIPOPROTEINS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF AD

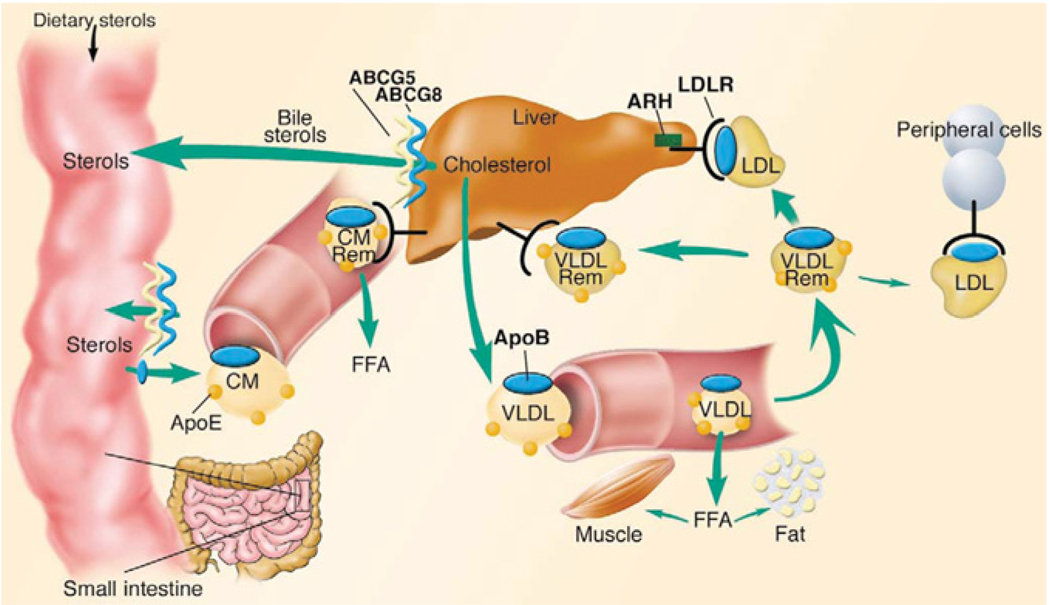

Lipoproteins are heterogeneous lipid and protein complexes. The principal function of lipoproteins is to transport lipids as fuel for cells throughout the body. Typically, a lipoprotein particle consists of a monolayer surface shell of phospholipids, cholesterol and apolipoproteins surrounding a hydrophobic core of triacylglycerols and cholesterol esters [103–105]. The apolipoproteins are integrated into the lipid environment through amphipathic helices, which contain hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains. Following food intake, energy distribution occurs largely through generation of TGRLs, either chylomicrons or VLDLs, which are synthesized from exogenous and endogenous lipids respectively (Figure 3) [106]. The elevation of triacylglycerol in the blood after consumption of a meal, postprandial lipaemia,is the result of contributions from both of these pathways. Once in the blood, the triacylglycerols in TGRLs are hydrolysed by LpL (lipoprotein lipase), an enzyme anchored to endothelial cells [107–111]. Hydrolysis results in the successive formation of smaller TGRLs, called lipoprotein remnant particles, as well as other lipolysis products, such as fatty acids, phospholipids, monoacylglycerols and diacylglycerols. Furthermore, lipolysis of VLDL remnant particles yields LDL. The composition and size distribution of TGRLs have been shown to be important in ASCVD [56]. For example, VLDLs and chylomicron remnant lipoprotein particles are known to penetrate arterial walls and become trapped in the artery wall, thus participating in the early stages of atherosclerosis. However, VLDL and chylomicron remnant particles are unlikely to penetrate brain microvascular endothelium because of the reduced permeability of the BBB.

Figure 3. Overview of LDL metabolism in humans.

Dietary cholesterol and triacylglycerols are packaged with apolipoproteins in the enterocytes of the small intestine and secreted into the lymphatic system as chylomicrons (CM). As chylomicrons circulate, the core triacylglycerols are hydrolysed by LpL, resulting in the formation of chylomicron remnants (CM Rem), which are rapidly removed by the liver. Dietary cholesterol has four possible fates once it reaches the liver: it can be (i) esterified and stored as cholesteryl esters in hepatocytes; (ii) packaged into VLDL particles and secreted into the plasma; (iii) secreted directly into the bile; or (iv) converted into bile acids and secreted into the bile. VLDL particles secreted into the plasma undergo lipolysis to form VLDL remnants (VLDL Rem). Approx. 50 % of VLDL remnants are removed by the liver via the LDLR and the remainder mature into LDL, the major cholesterol transport particle in the blood. An estimated 70 % of circulating LDL is cleared by LDLR in the liver. ABCG5 and ABCG8 (ABC family G, members 5 and 8 respectively) are located predominantly in the enterocytes of the duodenum and jejunum, the sites of uptake of dietary sterols, and in hepatocytes, where they participate in sterol trafficking into bile. ApoB, apolipoprotein B; ARH, autosomal recessive hypercholesterolaemia protein; FFA, non-esterified (‘free’) fatty acid Journal of Clinical Investigation. Online by Rader, D.J., Cohen, J. and Hobbs, H.H. Copyright 2003 by American Society for Clinical Investigation. Reproduced with permission of American Society for Clinical Investigation in the format Journal via Copyright Clearance Center.

Previous studies have indicated that cardiovascular risk factors, including elevated blood cholesterol and triacylglycerol, increase the likelihood of AD and dementia [112–118]. Most, but not all, previous studies have shown that elevations in mid-life cholesterol levels in the blood are associated with the development of AD [115,116,119–124]. However, definitive randomized control trials have yet to show that HMG-CoA (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins) reduce the incidence of AD [59,120,125–127]. Despite the lack of conclusive evidence that cholesterol interventions have a preventative effect on AD, a substantial body of data supports the notion that mid-life blood cholesterol and triacylglycerol levels are associated with the development of AD.

TRIACYLGLYCEROLS, FATTY ACIDS AND THE INITIATION AND PROGRESSION OF AD

Most, but not all, previous studies in humans have shown an association between AD and elevated fasting triacylglycerols in the blood and also an association of AD with the metabolic syndrome. In one human study, the only significant relationship of lipids/lipoproteins with AD was elevated triacylglycerols [128]. The Three Cities Study showed that a high plasma triacylglycerol level was the only component of the metabolic syndrome that was significantly associated with the incidence of all-cause {HR (hazard ratio) 1.45, [95% CI (confidence interval), 1.05–2.00]; P=0.02} and vascular [HR, 2.27 (95% CI, 1.16–4.42); P= 0.02] dementia, even after adjustment for the apoE genotype [129]. In another study, elevated total cholesterol, LDLs and triacylglycerol, with normal HDLs and total cholesterol/HDL ratio characterize the lipid profile in AD, which overlaps with the ASCVD risk profile [130]. Additionally, patients with AD had a significantly larger mean waist circumference, higher mean plasma concentrations of triacylglycerols and glucose, and a lower mean plasma concentration of HDL-cholesterol compared with controls [131]. Thus most previous human clinical studies have shown an association of serum triacylglycerols and AD or vascular dementia.

However, the clinical measurement of the mass of triacylglycerols in blood may not reveal the true pathogenicity of TGRLs, and specifically TGRL lipolysis products. Chylomicrons and VLDL particles, which carry most triacylglycerols in blood, are not strongly associated with ASCVD or AD, perhaps because they are large particles and do not easily enter the artery wall and do not cross the BBB.

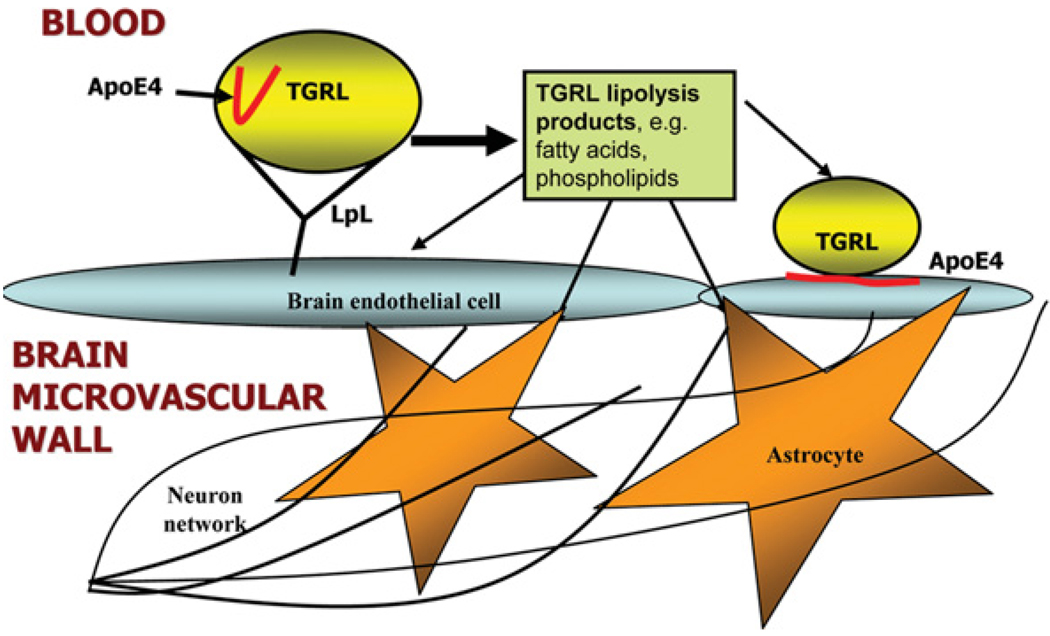

Mouse models and cell culture models also have suggested a role for triacylglycerols and fatty acids in AD pathogenesis. Elevated triacylglycerol levels were found in the brain of a mouse model of AD [132]. In another study, elevated blood triacylglycerol levels preceded amyloid deposition in mouse brain [133]. It has been shown that fatty acids can cause generation of presenilin-1, an important determinate of γ -secretase activity necessary for generation of Aβ in neuroblastoma cells [134]. Furthermore, palmitic and stearic fatty acids [SFAs (saturated fatty acids)] induce AD-like hyperphosphorylation of Tau in primary rat cortical neurons [135]. These results establish a central role for NEFAs [non-esterified (‘free’) fatty acids] in causing hyperphosphorylation of Tau through astrogliamediated oxidative stress. Accumulating evidence from human, mouse and cell culture models suggests triacylglycerols and fatty acids are related to the development of AD (Figure 4) [136,137].

Figure 4. Vascular disease model illustrating how TGRL lipolysis products and apoE4 may interact with brain microvascular endothelial cells and astrocytes.

Hydrolysis of TGRLs by LpL present in the circulation results in the release of lipolysis products, including TGRL remnant particles, mono-, di- and tri-acylglycerols, phospholipids and NEFAs. Lipolysis products may influence the inflammatory environment of the brain through two pathways: (i) direct injury to brain microvascular endothelial cells or astrocytes, or (ii) indirect injury to glial cells and neurons through cascades that begin with damaged endothelial cells. In addition, apoE4 associated with TGRL undergoes a conformational change to a more linear species in the presence of TGRL lipolysis products. This conformational change may influence the binding of apoE4 to brain microvascular endothelial cells. Negative effects to the endothelial cells due to the altered apoE4 conformation may disrupt the barrier function of the cerebrovasculature and allow TGRL lipolysis products to access the brain parenchyma, causing damage to neurons and glial cells.

The literature also contains substantial data that specific fatty acids can either prevent or promote cognitive decline [119,138–141]. For example, eating fish or consuming increased long-chain omega-3 fatty acids in the diet had a beneficial effect on cognitive decline [139,142,143]. Oxidized linoleic acid, otherwise known as 13-HODE [(13S)-hydroxyoctadeca-(9Z,11E)-dienoic acid], is the most prevalent oxidized lipid in oxidized LDLs, a known mediator of vascular injury and atherosclerosis. A recent study has shown that 13-HODE is the most prevalent oxylipid present in VLDL lipolysis products in normal young adults [144], raising concern about life-long implications of 13-HODE elevations at the blood–endothelial cell interface where lipolysis occurs. Further study is needed to unravel the relationship between long-chain fatty acids, stroke and AD, and to examine the potential beneficial effects of omega-3 long-chain PUFAs (polyunsaturated fatty acids), such as DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) [145].

Previous studies also indicate that the fat composition and fat quantity of the diet is important in the promotion or prevention of AD, vascular dementia and ASCVD [52,53,60,146–157]. For example, a Mediterranean diet confers protection against AD, as compared with a Western diet [121,158–164]. In addition, DHA is an abundant fatty acid in the brain, and increased plasma levels of DHA were associated with reduction in AD in the Framingham Heart Study [165]. Understanding how lipids/lipoproteins influence AD pathophysiology could have a substantial impact on primary prevention of this devastating disease.

TGRL LIPOLYSIS PRODUCTS AND VASCULAR INFLAMMATION

Triacylglycerols in blood are contained in the core of TGRLs (chylomicrons, VLDLs and their remnant particles) and are not in direct contact with endothelium. LpL is anchored to brain microvascular endothelium, where it hydrolyses TGRLs to smaller lipolysis products, such as fatty acids and phospholipids. These lipolysis products are generated in very high concentrations immediately adjacent to brain microvascular endothelial cells. Potentially, lipolysis products generated at the luminal surface of the vascular endothelium can directly injure the endothelium and increase permeability and/or cross the BBB and injure astrocytes (Figure 4). Our studies have shown that TGRL particles, including chylomicrons and VLDLs, have relatively little effect on a variety of endothelial cell types in comparison with the dramatic effects on endothelial cell injury that we have observed with TGRL lipolysis products [107,166–169]. Thus, with regard to the brain microvasculature, TGRL lipolysis products, rather than plasma triacylglycerols, may be the most meaningful lipids to study in terms of the pathogenesis of AD.

Previous investigations have shown that TGRL lipolysis products have both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects on endothelium [170–173]. Sub-physiological concentrations of lipolysis products (5–10 µg of VLDL + 200 units/ml LpL) in endothelial cell culture prevented endothelial cell injury through generation of PPAR (peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor) ligands in response to cytokine stimulation with TNF-α [174,175]. Similar studies using human aortic endothelial cells in culture generated comparable results. However, as VLDL triacylglycerol concentrations approached physiological concentrations (50 mg/dl triacylglycerol) in the human aortic endothelial cell culture system, endothelial cell injury predominated when TGRLs were treated with LpL. Thus TGRL lipolysis products at high physiological-to-pathophysiological concentrations appear to have a predominately pro-inflammatory effect.

The products of TGRL lipolysis, especially the fatty acid fraction, and treatment with individual fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, in moderate-to-high physiological concentrations also injure endothelial cells. These experiments strongly indicate that it is the enzymatic function of LpL that is an important factor in generating endothelial cell injury [166]. As shown by Eiselein et al. [166] in Figure 5, the permeability of human aortic endothelial cell monolayers in culture is radically affected by exposure to TGRL lipolysis products. ZO-1 (zonula occludens-1) is an integral member of structurally sound tight junctions between adjacent endothelial cells and helps to regulate the paracellular permeability of endothelial monolayers. Exposure to TGRL lipolysis products resulted in a transition from smooth continuous ZO-1 staining to a fragmented discontinuous appearance. The disruption of the structural integrity of the tight junctions between cells suggests that the monolayer’s ability to regulate its permeability was negatively affected. Additional experiments using TEER (transendothelial electrical resistance) measurements showed that the resistance of the monolayer decreased following treatment with TGRL lipolysis products [166]. Recent studies in mice overexpressing hLpL (human LpL) have shown that excess vascular wall LpL augments vascular dysfunction in the setting of inflammation [176,177]. Furthermore, in transgenic mice expressing hLpL, agonist-induced contraction of smooth muscle cells was increased when compared with that of wild-type mice [178]. These studies strongly indicate that TGRL lipolysis products in highphysiological and supra-physiological concentrations injure endothelium and smooth muscle cells. The aforementioned experiments that observed similar results using varying concentrations of LpL in both cell culture and animal models suggest that the physiological action of normal LpL levels is sufficient to generate injurious levels of TGRL lipolysis products at the vascular wall.

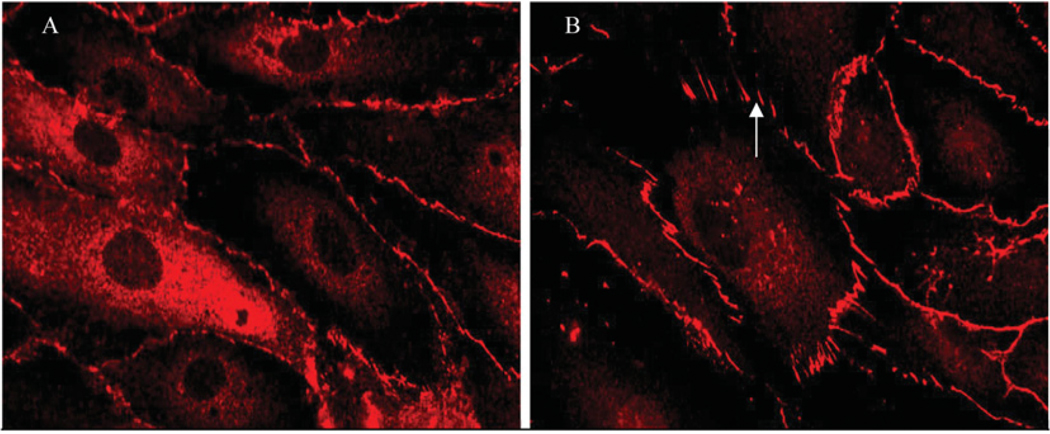

Figure 5. ZO-1 immunofluorescence before and after treatment with TGRL lipolysis products.

Images of human aortic endothelial cell monolayers showing (A) continuous ZO-1 staining with treatment with TGRL (150 mg/dl triacylglycerol), and (B) discontinuity and radial rearrangement of ZO-1 (arrow) during exposure to lipolysis products generated from co-incubation of TGRL (150 mg/dl) + LpL (2 units/ml), causing increased endothelial layer permeability. This Figure was reproduced from [166] and is used with permission. Copyright (2007) American Physiological Society.

Lipotoxicity is the term commonly used to describe cell dysfunction and death induced by lipid accumulation in non-adipose tissue [179]. Most lipotoxicity has been associated with SFA-induced lipotoxicity [180– 182]. Furthermore, lipotoxicity has been related to ER (endoplasmic reticulum) stress [181,183,184], apoptosis [182], mitochondrial dysfunction [185–188], lysosomal pathways and potentially autophagy [189,190]. Neurovascular lipotoxicity may play an important role in TGRL lipolysis-induced brain microvascular endothelial cell and astrocyte injury.

TGRL LIPOLYSIS PRODUCTS, ROS (REACTIVE OXYGEN SPECIES) AND AD

Oxidative stress, in which ROS overwhelm antioxidant mechanisms, is hypothesized to be important in neurodegeneration [191–193]. Previous studies have shown ROS to be important in AD [2,12,14,21,194–197], although whether ROS are causes or consequences of AD has yet to be defined. For example, lipoprotein oxidizability (as indicatedby the accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides from the aggregate lipoproteins under oxidizing conditions) was measured in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma from 29 AD patients and was found to be significantly increased in comparison with 29 controls without dementia [198]. ROS can directly oxidize and damage DNA, proteins and lipids [199], and induce stress-response genes. In addition, astrocyte NADPH oxidase may be a key enzyme in the production of ROS in AD [12]. Some studies have indicated that ROS can be reduced by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) [88]. One potential mechanism by which statins could reduce astrocyte injury is by down-regulation of NADPH oxidase, leading to a reduction in ROS production [200,201]. In addition, ROS can mediate apoptosis by mitochondrial apoptotic pathways [202]. VLDL lipolysis products generate ROS in human aortic endothelial cells [144,203], suggesting that VLDL lipolysis product-induced ROS generation in human microvascular endothelial cells and astrocytes may be an important mechanism of oxidative injury in these cells.

TLRs (Toll-like receptors) are a class of proteins that play a key role in the innate immune system. Recent work has shown that TLRs may be important in the pathophysiology of AD and may specifically mediate astrocyte injury and apoptosis [204,205]. SFAs modulate TLR4 through regulation of receptor dimerization and incorporation of TLR4 into lipid rafts in a ROS-dependent manner [206]. High concentrations of SFAs induced by lipolysis of VLDLs may injure astrocytes by generation of ROS and activation of TLR4.

BRAIN LIPIDS AND AD

The brain contains more lipid than any other single organ in the body. Both extra- and intra-cellular lipids, as well as lipids within the plasma membrane, are essential to normal brain function, but also have the capacity to induce injury, apoptosis and cell death of the brain [207–218]. DHA, phospholipid oxidation products, neurotrophin receptors, lipoprotein receptors, neural membrane glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid mediators, and small-molecule oxidation products that trigger disease-associated protein misfolding have all been associated with either the promotion or prevention of AD. Montine et al. [219] demonstrated that measurements of F2-isoprostanes in cerebrospinal fluid, which are indicative of free radical damage to brain lipids, correlate well with the degree of neurodegeneration in AD patients and may be a promising biomarker for AD. Preliminary studies also suggest that resolvins, compounds that are derived from the omega-3 fatty acids EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA [220,221], may be important in AD for their anti-inflammatory properties. Further research is needed to unravel the intricate web of connections between specific lipids, their locations and functions within the brain, and the pathology of AD.

CONCLUSIONS AND CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Current treatment strategies for AD revolve around attempts to slow the progression of the disease, maintain cognitive ability and reduce the negative behavioural consequences of the disease. However, there are no known treatments to prevent or cure AD. As the underlying causative factors for AD are still unknown, targeted treatments that effectively combat the development of the disease have proven to be elusive. An increasing number of studies suggest that, whether or not lifestyle factors are the primary cause of AD, they have a significant effect on the course of the disease. As such, these lifestyle factors represent an important avenue of approach to help slow or prevent the progression of AD. In particular, lipids derived from the diet, such as fatty acids, provide an appealing target, given the abundance of current research that suggests potentially detrimental effects of these lipids on cellular components of the cerebrovasculature.

Our present review shows considerable overlap of the risk factors associated with AD and the risk factors associated with ASCVD, such as dyslipidaemia and the presence of the apoE4 allele. Furthermore, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and diabetes are believed to be causative for ASCVD. It is reasonable to speculate that these same risk factors could initiate or promote AD, although these areas are relatively understudied in AD. Given this background information, aggressive treatment of ‘cardiovascular risk factors’ for the prevention and attenuation of AD appears warranted and should be vigorously pursued.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

R.A. was supported by an American Heart Association Western States Affiliate Predoctoral Fellowship. J.R. was supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Program Grant (R01) [grant number HL55667], a UC Davis AD Center Core Pilot and Feasibility Project [grant number P30 AG10129-15], and the Richard A. and Nora Eccles Harrison Endowed Chair in Diabetes Research. This publication was made possible by grant number UL1 RR024146 to the UC Davis Clinical and Translational Science Center from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of NIH and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overviewtranslational.asp.

Abbreviations

- ABC

ATP-binding-cassette

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- apoE

apolipoprotein E

- ASCVD

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- Aβ

amyloid β

- Aβ42

Aβ-(1–42)

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- CAA

cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- CI

confidence interval

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HMG-CoA

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA

- 13-HODE

(13S)-hydroxyoctadeca-(9Z,11E)-dienoic acid

- HR

hazard ratio

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LDLR

LDL receptor

- LpL

lipoprotein lipase

- hLpL

human LpL

- LXR

liver X receptor

- NEFA

non-esterified (‘free’) fatty acid

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SFA

saturated fatty acid

- TGRL

triacylglycerol (triglyceride)-rich lipoprotein

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

- VLDL

very-low-density lipoprotein

- ZO-1

zonula occludens-1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggarwal NT, Decarli C. Vascular dementia: emerging trends. Semin. Neurol. 2007;27:66–77. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-956757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chui HC, Zarow C, Mack WJ, Ellis WG, Zheng L, Jagust WJ, Mungas D, Reed BR, Kramer JH, Decarli CC, et al. Cognitive impact of subcortical vascular and Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Ann. Neurol. 2006;60:677–687. doi: 10.1002/ana.21009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeCarli C. The role of cerebrovascular disease in dementia. Neurologist. 2003;9:123–136. doi: 10.1097/00127893-200305000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeCarli CS. When two are worse than one: stroke and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1326–1327. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244911.16867.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berglund L, Wiklund O, Eggertsen G, Olofsson SO, Eriksson M, Linden T, Bondjers G, Angelin B. Apolipoprotein E phenotypes in familial hypercholesterolaemia: importance for expression of disease and response to therapy. J. Intern. Med. 1993;233:173–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1993.tb00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benarroch EE. Neurovascular unit dysfunction: a vascular component of Alzheimer disease? Neurology. 2007;68:1730–1732. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264502.92649.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gee JR, Keller JN. Astrocytes: regulation of brain homeostasis via apolipoprotein E. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005;37:1145–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haseloff RF, Blasig IE, Bauer HC, Bauer H. In search of the astrocytic factor(s) modulating blood-brain barrier functions in brain capillary endothelial cells in vitro. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2005;25:25–39. doi: 10.1007/s10571-004-1375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parri R, Crunelli V. An astrocyte bridge from synapse to blood flow. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:5–6. doi: 10.1038/nn0103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008;57:178–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abramov AY, Duchen MR. The role of an astrocytic NADPH oxidase in the neurotoxicity of amyloid β peptides. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2005;360:2309–2314. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blasko I, Stampfer-Kountchev M, Robatscher P, Veerhuis R, Eikelenboom P, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. How chronic inflammation can affect the brain and support the development of Alzheimer’s disease in old age: the role of microglia and astrocytes. Aging Cell. 2004;3:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drew PD, Xu J, Storer PD, Chavis JA, Racke MK. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist regulation of glial activation: relevance to CNS inflammatory disorders. Neurochem. Int. 2006;49:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Y, Weisgraber KH, Mucke L, Mahley RW. Apolipoprotein E: diversity of cellular origins, structural and biophysical properties, and effects in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2004;23:189–204. doi: 10.1385/JMN:23:3:189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Husemann J, Silverstein SC. Expression of scavenger receptor class B, type I, by astrocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells in normal adult mouse and human brain and in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158:825–832. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64030-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadiu I, Glanzer JG, Kipnis J, Gendelman HE, Thomas MP. Mononuclear phagocytes in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurotox. Res. 2005;8:25–50. doi: 10.1007/BF03033818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miao H, Hu YL, Shiu YT, Yuan S, Zhao Y, Kaunas R, Wang Y, Jin G, Usami S, Chien S. Effects of flow patterns on the localization and expression of VE-cadherin at vascular endothelial cell junctions: in vivo and in vitro investigations. J. Vasc. Res. 2005;42:77–89. doi: 10.1159/000083094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minagar A, Shapshak P, Fujimura R, Ownby R, Heyes M, Eisdorfer C. The role of macrophage/microglia and astrocytes in the pathogenesis of three neurologic disorders: HIV-associated dementia, Alzheimer disease, and multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2002;202:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossner S. New players in old amyloid precursor protein-processing pathways. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2004;22:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sastre M, Klockgether T, Heneka MT. Contribution of inflammatory processes to Alzheimer’s disease: molecular mechanisms. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2006;24:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strazielle N, Ghersi-Egea JF, Ghiso J, Dehouck MP, Frangione B, Patlak C, Fenstermacher J, Gorevic P. In vitro evidence that β-amyloid peptide 1–40 diffuses across the blood-brain barrier and affects its permeability. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2000;59:29–38. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowman GL, Kaye JA, Moore M, Waichunas D, Carlson NE, Quinn JF. Blood-brain barrier impairment in Alzheimer disease: stability and functional significance. Neurology. 2007;68:1809–1814. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000262031.18018.1a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell RD, Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular mechanisms and blood-brain barrier disorder in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:103–113. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0522-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desai TR, Leeper NJ, Hynes KL, Gewertz BL. Interleukin-6 causes endothelial barrier dysfunction via the protein kinase C pathway. J. Surg. Res. 2002;104:118–123. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2002.6415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lashuel HA. Membrane permeabilization: a common mechanism in protein-misfolding diseases. Sci. Aging Knowl. Environ. 2005:pe28. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2005.38.pe28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persidsky Y, Ramirez S, Haorah J, Kanmogne G. Blood-brain barrier: structural components and function under physiologic and pathologic conditions. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1:223–236. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simionescu M, Antohe F. Functional ultrastructure of the vascular endothelium: changes in various pathologies. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2006;176:41–69. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32967-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saido TC, Iwata N. Metabolism of amyloid β peptide and pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: towards presymptomatic diagnosis, prevention and therapy. Neurosci. Res. 2006;54:235–253. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skovronsky DM, Lee VM, Pratico D. Amyloid precursor protein and amyloid β peptide in human platelets. Role of cyclooxygenase and protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:17036–17043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayeux R, Tang MX, Jacobs DM, Manly J, Bell K, Merchant C, Small SA, Stern Y, Wisniewski HM, Mehta PD. Plasma amyloid β-peptide 1–42 and incipient Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 1999;46:412–416. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199909)46:3<412::aid-ana19>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayeux RM, Honig LSM, Tang MXP, Manly JP, Stern YP, Schupf NP, Mehta PDP. Plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 and Alzheimer’s disease: relation to age, mortality, and risk. Neurology. 2003;61:1185–1190. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000091890.32140.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, Song X, Citron M, Suzuki N, Bird TD, Hardy J, Hutton M, Kukull W, et al. Secreted amyloid β-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 1996;2:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellis RJ, Olichney JM, Thal LJ, Mirra SS, Morris JC, Beekly D, Heyman A. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: the CERAD experience, Part XV. Neurology. 1996;46:1592–1596. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Attems J, Quass M, Jellinger KA, Lintner F. Topographical distribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy and its effect on cognitive decline are influenced by Alzheimer disease pathology. J. Neurol. Sci. 2007;257:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Attems J, Jellinger KA, Lintner F. Alzheimer’s disease pathology influences severity and topographical distribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110:222–231. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1064-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfeifer LAM, White LRM, Ross GWM, Petrovitch HM, Launer LJP. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive function: the HAAS autopsy study. Neurology. 2002;58:1629–1634. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.11.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herzig MC, Van Nostrand WE, Jucker M. Mechanism of cerebral β-amyloid angiopathy: murine and cellular models. Brain Pathol. 2006;16:40–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2006.tb00560.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vinters HV, Secor DL, Read SL, Frazee JG, Tomiyasu U, Stanley TM, Ferreiro JA, Akers MA. Microvasculature in brain biopsy specimens from patients with Alzheimer’s disease: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 1994;18:333–348. doi: 10.3109/01913129409023202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mok SS, Losic D, Barrow CJ, Turner BJ, Masters CL, Martin LL, Small DH. The β-amyloid peptide of Alzheimer’s disease decreases adhesion of vascular smooth muscle cells to the basement membrane. J. Neurochem. 2006;96:53–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Christie R, Yamada M, Moskowitz M, Hyman B. Structural and functional disruption of vascular smooth muscle cells in a transgenic mouse model of amyloid angiopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158:1065–1071. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paris D, Ait-Ghezala G, Mathura VS, Patel N, Quadros A, Laporte V, Mullan M. Anti-angiogenic activity of the mutant Dutch Aβ peptide on human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2005;136:212–230. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paris D, Humphrey J, Quadros A, Patel N, Crescentini R, Crawford F, Mullan M. Vasoactive effects of Aβ in isolated human cerebrovessels and in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: role of inflammation. Neurol. Res. 2003;25:642–651. doi: 10.1179/016164103101201940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paris D, Townsend K, Quadros A, Humphrey J, Sun J, Brem S, Wotoczek-Obadia M, DelleDonne A, Patel N, Obregon DF, et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis by Aβ peptides. Angiogenesis. 2004;7:75–85. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000037335.17717.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stopa EGMD, Butala PMD, Salloway SMD, Johanson CEP, Gonzalez LP, Tavares RB, Hovanesian VB, Hulette CMMD, Vitek MPP, Cohen RAP. Cerebral cortical arteriolar angiopathy, vascular β-amyloid, smooth muscle actin, braak stage, and ApoE genotype. Stroke. 2008;39:814–821. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.493429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thal DR, Capetillo-Zarate E, Larionov S, Staufenbiel M, Zurbruegg S, Beckmann N. Capillary cerebral amyloid angiopathy is associated with vessel occlusion and cerebral blood flow disturbances. Neurobiol. Aging. 2009;30:1936–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fazio S, Linton MF, Swift LL. The cell biology and physiologic relevance of ApoE recycling. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2000;10:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(00)00033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lahiri DK. Apolipoprotein E as a target for developing new therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease based on studies from protein, RNA, and regulatory region of the gene. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2004;23:225–233. doi: 10.1385/JMN:23:3:225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miserez AR, Scharnagl H, Muller PY, Mirsaidi R, Stahelin HB, Monsch A, Marz W, Hoffmann MM. Apolipoprotein E3Basel: new insights into a highly conserved protein region. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;33:677–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karlsson H, Leanderson P, Tagesson C, Lindahl M. Lipoproteomics I: mapping of proteins in low-density lipoprotein using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2005;5:551–565. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahley RW. Apolipoprotein E: cholesterol transport protein with expanding role in cell biology. Science. 1988;240:622–630. doi: 10.1126/science.3283935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anuurad E, Rubin J, Lu G, Pearson TA, Holleran S, Ramakrishnan R, Berglund L. Protective effect of apolipoprotein E2 on coronary artery disease in African Americans is mediated through lipoprotein cholesterol. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:2475–2481. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600288-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berglund L. The APOE gene and diets-food (and drink) for thought. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001;73:669–670. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eggertsen G, Heimburger O, Stenvinkel P, Berglund L. Influence of variation at the apolipoprotein E locus on lipid and lipoprotein levels in CAPD patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1997;12:141–144. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eggertsen G, Tegelman R, Ericsson S, Angelin B, Berglund L. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism in a healthy Swedish population: variation of allele frequency with age and relation to serum lipid concentrations. Clin. Chem. 1993;39:2125–2129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hyson D, Rutledge JC, Berglund L. Postprandial lipemia and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2003;5:437–444. doi: 10.1007/s11883-003-0033-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Isasi CR, Shea S, Deckelbaum RJ, Couch SC, Starc TJ, Otvos JD, Berglund L. Apolipoprotein ε2 allele is associated with an anti-atherogenic lipoprotein profile in children: the Columbia University BioMarkers Study. Pediatrics. 2000;106:568–575. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pablos-Mendez A, Mayeux R, Ngai C, Shea S, Berglund L. Association of apo E polymorphism with plasma lipid levels in a multiethnic elderly population. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997;17:3534–3541. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.12.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Romas SN, Tang MX, Berglund L, Mayeux R. APOE genotype, plasma lipids, lipoproteins, and AD in community elderly. Neurology. 1999;53:517–521. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.3.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rubin J, Berglund L. Apolipoprotein E and diets: a case of gene-nutrient interaction? Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2002;13:25–32. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200202000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wetterau JR, Aggerbeck LP, Rall SC, Jr, Weisgraber KH. Human apolipoprotein E3 in aqueous solution. I. Evidence for two structural domains. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:6240–6248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilson C, Wardell MR, Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW, Agard DA. Three-dimensional structure of the LDL receptor-binding domain of human apolipoprotein E. Science. 1991;252:1817–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.2063194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weisgraber KH, Rall SC, Jr, Mahley RW. Human E apoprotein heterogeneity. Cysteine-arginine interchanges in the amino acid sequence of the apo-E isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:9077–9083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vance JE, Karten B, Hayashi H. Lipid dynamics in neurons. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006;34:399–403. doi: 10.1042/BST0340399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dong LM, Weisgraber KH. Human apolipoprotein E4 domain interaction. Arginine 61 and glutamic acid 255 interact to direct the preference for very low density lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:19053–19057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saito H, Dhanasekaran P, Baldwin F, Weisgraber KH, Phillips MC, Lund-Katz S. Effects of polymorphism on the lipid interaction of human apolipoprotein E. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:40723–40729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dallongeville J, Davignon J, Lussier-Cacan S. ACAT activity in freshly isolated human mononuclear cell homogenates from hyperlipidemic subjects. Metab. Clin. Exp. 1992;41:154–159. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90144-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fleisher A, Grundman M, Jack CR, Jr, Petersen RC, Taylor C, Kim HT, Schiller DH, Bagwell V, Sencakova D, Weiner MF, et al. Sex, apolipoprotein Eε 4 status, and hippocampal volume in mild cognitive impairment. Arch. Neurol. 2005;62:953–957. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tiret L, de Knijff P, Menzel HJ, Ehnholm C, Nicaud V, Havekes LM. ApoE polymorphism and predisposition to coronary heart disease in youths of different European populations. The EARS Study. European Atherosclerosis Research Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. 1994;14:1617–1624. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.10.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davignon J, Gregg RE, Sing CF. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;8:1–21. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roses AD, Einstein G, Gilbert J, Goedert M, Han SH, Huang D, Hulette C, Masliah E, Pericak-Vance MA, Saunders AM, et al. Morphological, biochemical, and genetic support for an apolipoprotein E effect on microtubular metabolism. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1996;777:146–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW. Human apolipoprotein E: the Alzheimer’s disease connection. FASEB J. 1996;10:1485–1494. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.13.8940294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zipser BD, Johanson CE, Gonzalez L, Berzin TM, Tavares R, Hulette CM, Vitek MP, Hovanesian V, Stopa EG. Microvascular injury and blood-brain barrier leakage in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2007;28:977–986. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mahley RW, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y. Apolipoprotein E4: a causative factor and therapeutic target in neuropathology, including Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:5644–5651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600549103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ophir G, Amariglio N, Jacob-Hirsch J, Elkon R, Rechavi G, Michaelson DM. Apolipoprotein E4 enhances brain inflammation by modulation of the NF-κB signaling cascade. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005;20:709–718. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Manelli AM, Stine WB, Van Eldik LJ, LaDu MJ. ApoE and Aβ1-Abet42 interactions: effects of isoform and conformation on structure and function. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2004;23:235–246. doi: 10.1385/JMN:23:3:235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mullick AE, Powers AF, Kota RS, Tetali SD, Eiserich JP, Rutledge JC. Apolipoprotein E3- and nitric oxide-dependent modulation of endothelial cell inflammatory responses. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27:339–345. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000253947.70438.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ophir G, Meilin S, Efrati M, Chapman J, Karussis D, Roses A, Michaelson DM. Human apoE3 but not apoE4 rescues impaired astrocyte activation in apoE null mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2003;12:56–64. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(02)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rubinsztein DC, Hanlon CS, Irving RM, Goodburn S, Evans DG, Kellar-Wood H, Xuereb JH, Bandmann O, Harding AE. Apo E genotypes in multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, schwannomas and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Cell. Probes. 1994;8:519–525. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1994.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barger SW, Harmon AD. Microglial activation by Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein and modulation by apolipoprotein E. Nature. 1997;388:878–881. doi: 10.1038/42257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reference deleted

- 82.Tetali SD, Budamagunta MS, Voss JC, Rutledge JC. C-terminal interactions of apolipoprotein E4 respond to the postprandial state. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:1358–1365. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500559-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bradley WA, Gianturco SH. ApoE is necessary and sufficient for the binding of large triglyceride-rich lipoproteins to the LDL receptor; apoB is unnecessary. J. Lipid Res. 1986;27:40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brown SA, Via DP, Gotto AM, Jr, Bradley WA, Gianturco SH. Apolipoprotein E-mediated binding of hypertriglyceridemic very low density lipoproteins to isolated low density lipoprotein receptors detected by ligand blotting. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1986;139:333–340. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(86)80118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gianturco SH, Bradley WA. Interactions of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins with receptors: modulation by thrombin. Semin. Thromb. Hemostasis. 1986;12:277–279. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1003566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gianturco SH, Gotto AM, Jr, Hwang SL, Karlin JB, Lin AH, Prasad SC, Bradley WA. Apolipoprotein E mediates uptake of Sf 100–400 hypertriglyceridemic very low density lipoproteins by the low density lipoprotein receptor pathway in normal human fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:4526–4533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hatters DM, Budamagunta MS, Voss JC, Weisgraber KH. Modulation of apolipoprotein E structure by domain interaction: differences in lipid-bound and lipid-free forms. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:34288–34295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wolozin B, Manger J, Bryant R, Cordy J, Green RC, McKee A. Re-assessing the relationship between cholesterol, statins and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 2006;185:63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Abildayeva K, Jansen PJ, Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Bloks VW, Bakker AH, Ramaekers FC, de Vente J, Groen AK, Wellington CL, Kuipers F, Mulder M. 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol participates in a liver X receptor-controlled pathway in astrocytes that regulates apolipoprotein E-mediated cholesterol efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:12799–12808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Burgess BL, Parkinson PF, Racke MM, Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Fan J, Wong C, Stukas S, Theroux L, Chan JY, Donkin J, et al. ABCG1 influences the brain cholesterol biosynthetic pathway but does not affect amyloid precursor protein or apolipoprotein E metabolism in vivo. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49:1254–1267. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700481-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fan J, Donkin J, Wellington C. Greasing the wheels of Aβ clearance in Alzheimer’s disease: the role of lipids and apolipoprotein E. Biofactors. 2009;35:239–248. doi: 10.1002/biof.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jiang Q, Lee CY, Mandrekar S, Wilkinson B, Cramer P, Zelcer N, Mann K, Lamb B, Willson TM, Collins JL, et al. ApoE promotes the proteolytic degradation of Aβ. Neuron. 2008;58:681–693. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim WS, Chan SL, Hill AF, Guillemin GJ, Garner B. Impact of 27-hydroxycholesterol on amyloid-β peptide production and ATP-binding cassette transporter expression in primary human neurons. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:121–131. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vaya J, Schipper HM. Oxysterols, cholesterol homeostasis, and Alzheimer disease. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:1727–1737. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bell RD, Sagare AP, Friedman AE, Bedi GS, Holtzman DM, Deane R, Zlokovic BV. Transport pathways for clearance of human Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide and apolipoproteins E and J in the mouse central nervous system. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:909–918. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Deane R, Sagare A, Hamm K, Parisi M, Lane S, Finn MB, Holtzman DM, Zlokovic BV. apoE isoform-specific disruption of amyloid β peptide clearance from mouse brain. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:4002–4013. doi: 10.1172/JCI36663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Chan JY, Wilkinson A, Tanaka T, Fan J, Ou G, Maia LF, Singaraja RR, Hayden MR, Wellington CL. Physiologically regulated transgenic ABCA1 does not reduce amyloid burden or amyloid-β peptide levels in vivo. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:914–923. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600543-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wahrle SE, Jiang H, Parsadanian M, Kim J, Li A, Knoten A, Jain S, Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Wellington CL, Bales KR, et al. Overexpression of ABCA1 reduces amyloid deposition in the PDAPP mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:671–682. doi: 10.1172/JCI33622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Eckert GP, Vardanian L, Rebeck GW, Burns MP. Regulation of central nervous system cholesterol homeostasis by the liver X receptor agonist TO-901317. Neurosci. Lett. 2007;423:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lefterov I, Bookout A, Wang Z, Staufenbiel M, Mangelsdorf D, Koldamova R. Expression profiling in APP23 mouse brain: inhibition of Aβ amyloidosis and inflammation in response to LXR agonist treatment. Mol. Neurodegener. 2007;2:20. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Riddell DR, Zhou H, Comery TA, Kouranova E, Lo CF, Warwick HK, Ring RH, Kirksey Y, Aschmies S, Xu J, et al. The LXR agonist TO901317 selectively lowers hippocampal Aβ42 and improves memory in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2007;34:621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mahley RW, Huang Y, Weisgraber KH. Putting cholesterol in its place: apoE and reverse cholesterol transport. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1226–1229. doi: 10.1172/JCI28632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gofman JW. Blood lipoproteins and atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 1950;29:815–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gofman JW, Jones HB, Lindgren FT, Lyon TP, Elliott HA, Strisower B. Blood lipids and human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1950;2:161–178. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.2.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gofman JW, Lindgren F. The role of lipids and lipoproteins in atherosclerosis. Science. 1950;111:166–171. doi: 10.1126/science.111.2877.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rader DJ, Cohen J, Hobbs HH. Monogenic hypercholesterolemia: new insights in pathogenesis and treatment. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1795–1803. doi: 10.1172/JCI18925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Goldberg IJ, Kako Y, Lutz EP. Responses to eating: lipoproteins, lipolytic products and atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2000;11:235–241. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Goldberg IJ, Merkel M. Lipoprotein lipase: physiology, biochemistry, and molecular biology. Front. Biosci. 2001;6:D388–D405. doi: 10.2741/goldberg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lopez-Miranda J, Perez-Martinez P, Marin C, Moreno JA, Gomez P, Perez-Jimenez F. Postprandial lipoprotein metabolism, genes and risk of cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2006;17:132–138. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000217894.85370.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Merkel M, Eckel RH, Goldberg IJ. Lipoprotein lipase: genetics, lipid uptake, and regulation. J. Lipid Res. 2002;43:1997–2006. doi: 10.1194/jlr.r200015-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Otarod JK, Goldberg IJ. Lipoprotein lipase and its role in regulation of plasma lipoproteins and cardiac risk. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2004;6:335–342. doi: 10.1007/s11883-004-0043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.de la Torre JC. How do heart disease and stroke become risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease? Neurol. Res. 2006;28:637–644. doi: 10.1179/016164106X130362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Decarli C. Vascular factors in dementia: an overview. J. Neurol. Sci. 2004;226:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mielke MM, Lyketsos CG. Lipids and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: is there a link? Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 2006;18:173–186. doi: 10.1080/09540260600583007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Panza F, D’Introno A, Colacicco AM, Capurso C, Pichichero G, Capurso SA, Capurso A, Solfrizzi V. Lipid metabolism in cognitive decline and dementia. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2006;51:275–292. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sjogren M, Mielke M, Gustafson D, Zandi P, Skoog I. Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease-is there a relation? Mech. Ageing Dev. 2006;127:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Skoog I, Gustafson D. Update on hypertension and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol. Res. 2006;28:605–611. doi: 10.1179/016164106X130506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wolozin B, Bednar MM. Interventions for heart disease and their effects on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol. Res. 2006;28:630–636. doi: 10.1179/016164106X130515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hartmann T, Kuchenbecker J, Grimm MO. Alzheimer’s disease: the lipid connection. J. Neurochem. 2007;103 Suppl. 1:159–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Burgess BL, Wellington CL. Why lipids are important for Alzheimer disease? Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2009;326:121–129. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-0012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kivipelto M, Solomon A. Cholesterol as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease: epidemiological evidence. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 2006;185:50–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lesser GT, Haroutunian V, Purohit DP, Schnaider Beeri M, Schmeidler J, Honkanen L, Neufeld R, Libow LS. Serum lipids are related to Alzheimer’s pathology in nursing home residents. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2009;27:42–49. doi: 10.1159/000189268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Liu JP, Tang Y, Zhou S, Toh BH, McLean C, Li H. Cholesterol involvement in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2010;43:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Panza F, Capurso C, D’Introno A, Colacicco AM, Vasquez F, Pistoia G, Capurso A, Solfrizzi V. Serum total cholesterol as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: mid-life or late-life determinations? Exp. Gerontol. 2006;41:805–806. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kandiah N, Feldman HH. Therapeutic potential of statins in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009;283:230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.02.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Purandare N. Preventing dementia: role of vascular risk factors and cerebral emboli. Br. Med. Bull. 2009;91:49–59. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldp020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Solomon A, Kivipelto M. Cholesterolmodifying strategies for Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;9:695–709. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cankurtaran M, Yavuz BB, Halil M, Dagli N, Cankurtaran ES, Ariogul S. Are serum lipid and lipoprotein levels related to dementia? Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2005;41:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Raffaitin C, Gin H, Empana JP, Helmer C, Berr C, Tzourio C, Portet F, Dartigues JF, Alperovitch A, Barberger-Gateau P. Metabolic syndrome and risk for incident Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia: the Three-City Study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:169–174. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sabbagh M, Zahiri HR, Ceimo J, Cooper K, Gaul W, Connor D, Sparks DL. Is there a characteristic lipid profile in Alzheimer’s disease? J. Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:585–589. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Razay G, Vreugdenhil A, Wilcock G. The metabolic syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2007;64:93–96. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Nguyen HN, Son DJ, Lee JW, Hwang DY, Kim YK, Cho JS, Lee US, Yoo HS, Moon DC, Oh KW, Hong JT. Mutant presenilin 2 causes abnormality in the brain lipid profile in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2006;29:884–889. doi: 10.1007/BF02973910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Burgess BL, McIsaac SA, Naus KE, Chan JY, Tansley GH, Yang J, Miao F, Ross CJ, van Eck M, Hayden MR, et al. Elevated plasma triglyceride levels precede amyloid deposition in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models with abundant Aβ in plasma. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006;24:114–127. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Liu Y, Yang L, Conde-Knape K, Beher D, Shearman MS, Shachter NS. Fatty acids increase presenilin-1 levels and γ -secretase activity in PSwt-1 cells. J. Lipid Res. 2004;45:2368–2376. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400317-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Patil S, Chan C. Palmitic and stearic fatty acids induce Alzheimer-like hyperphosphorylation of tau in primary rat cortical neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 2005;384:288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Panza F, Capurso C, D’Introno A, Colacicco AM, Del Parigi A, Seripa D, Pilotto A, Capurso A, Solfrizzi V. Diet, cholesterol metabolism, and Alzheimer’s disease: apolipoprotein E as a possible link? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006;54:1963–1965. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Phivilay A, Julien C, Tremblay C, Berthiaume L, Julien P, Giguere Y, Calon F. High dietary consumption of trans fatty acids decreases brain docosahexaenoic acid but does not alter amyloid-β and tau pathologies in the 3xTg-AD model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2009;159:296–307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Florent-Bechard S, Desbene C, Garcia P, Allouche A, Youssef I, Escanye MC, Koziel V, Hanse M, Malaplate-Armand C, Stenger C, et al. The essential role of lipids in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimie. 2009;91:804–809. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Fotuhi M, Mohassel P, Yaffe K. Fish consumption, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and risk of cognitive decline or Alzheimer disease: a complex association. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2009;5:140–152. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Hooijmans CR, Kiliaan AJ. Fatty acids, lipid metabolism and Alzheimer pathology. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;585:176–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Pauwels EK, Volterrani D, Mariani G, Kairemo K. Fatty acid facts, Part IV: docosahexaenoic acid and Alzheimer’s disease. A story of mice, men and fish. Drug. 2009;22:205–213. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2009.22.4.1367709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Boudrault C, Bazinet RP, Ma DW. Experimental models and mechanisms underlying the protective effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009;20:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Das UN. Folic acid and polyunsaturated fatty acids improve cognitive function and prevent depression, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease: but how and why? Prostaglandins Leukotrienes Essent. Fatty Acids. 2008;78:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wang L, Gill R, Pedersen TL, Higgins LJ, Newman JW, Rutledge JC. Triglyceride-rich lipoprotein lipolysis releases neutral and oxidized FFAs that induce endothelial cell inflammation. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:204–213. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700505-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Katz R, Hamilton JA, Pownall HJ, Deckelbaum RJ, Hillard CJ, Leboeuf RC, Watkins PA. Brain uptake and utilization of fatty acids, lipids and lipoproteins: recommendations for future research. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2007;33:146–150. doi: 10.1007/s12031-007-0059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Bourre JM. Effects of nutrients (in food) on the structure and function of the nervous system: update on dietary requirements for brain. Part 2: macronutrients. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2006;10:386–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Chahoud G, Aude YW, Mehta JL. Dietary recommendations in the prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease: do we have the ideal diet yet? Am. J. Cardiol. 2004;94:1260–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Heininger K. A unifying hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. III. Risk factors. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2000;15:1–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1077(200001)15:1<1::AID-HUP153>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kawas CH. Diet and the risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:877–879. doi: 10.1002/ana.20898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, Tangney CC, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Aggarwal N, Schneider J. Consumption of fish and n-3 fatty acids and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2003;60:940–946. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.7.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Panza F, Capurso C, Solfrizzi V. Cardiovascular factors and cognitive impairment: a role for unsaturated fatty acids and Mediterranean diet? Am. J. Cardiol. 2006;98:1120–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Scarmeas N, Stern Y, Tang MX, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA. Mediterranean diet and risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:912–921. doi: 10.1002/ana.20854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]