Abstract

Biliary epithelial cells (BEC) are morphologically and functionally heterogeneous. To investigate the molecular mechanism for their diversities, we test the hypothesis that large and small BEC have disparity in their target gene response to their transcriptional regulator, the biliary cell-enriched hepatocyte nuclear factor HNF6. The expression of the major HNF (HNF6, OC2, HNF1b, HNF1a, HNF4a, C/EBPb, and Foxa2) and representative biliary transport target genes that are HNF dependent were compared between SV40-transformed BEC derived from large (SV40LG) and small (SV40SM) ducts, before and after treatment with recombinant adenoviral vectors expressing HNF6 (AdHNF6) or control LacZ cDNA (AdLacZ). Large and small BEC were isolated from mouse liver treated with growth hormone, a known transcriptional activator of HNF6, and the effects on selected target genes were examined. Constitutive Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a gene expression were 2.3-, 12.4-, and 2.6-fold, respectively, higher in SV40SM cells. This was associated with 2.7- and 4-fold higher baseline expression of HNF1a- and HNF4a-regulated ntcp and oatp1 genes, respectively. Following AdHNF6 infection, HNF6 gene expression was 1.4-fold higher (P = 0.02) in AdHNF6 SV40SM relative to AdHNF6 SV40LG cells, with a corresponding higher Foxa2 (4-fold), HNF1a (15-fold), and HNF4a (6-fold) gene expression in AdHNF6-SV40SM over AdHNF6-SV40LG. The net effects were upregulation of HNF6 target gene glucokinase and of Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a target genes oatp1, ntcp, and mrp2 over AdLacZ control in both cells, but with higher levels in AdH6-SV40SM over AdH6-SV40LG of glucokinase, oatp1, ntcp, and mrp2 (by 1.8-, 3.4-, 2.4-, and 2.5-fold, respectively). In vivo, growth hormone-mediated increase in HNF6 expression was associated with similar higher upregulation of glucokinase and mrp2 in cholangiocytes from small vs. large BEC. Small and large BEC have a distinct profile of hepatocyte transcription factor and cognate target gene expression, as well as differential strength of response to transcriptional regulation, thus providing a potential molecular basis for their divergent function.

Keywords: heterogeneity, bile transport, hepatocyte nuclear factors, hepatocyte nuclear factor 6

hepatic gene expression is primarily regulated at the transcriptional level by families of hepatocyte nuclear factors (HNF). Among these, the homeodomain HNF1, the orphan nuclear receptor HNF4, the ONECUT HNF6 (also known as OC-1 and OC-2), forkhead box (FoxA), and the CCATT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBP) are cell-autonomous, liver-enriched transcription factors bearing specific DNA-binding domains, which recognize cognate DNA motifs on the regulatory region of hepatic target genes to participate in a cross-regulatory network for modulating target gene activities (10, 36). In vivo, HNF participate in the liver developmental program. For instance, Foxa1 and Foxa2 are implicated in hepatic specification (24), HNF4a in hepatic fate determination (30), and OC1 and OC2 in biliary cell lineage specification (8). HNF also participate in the regulation of hepatic function in the mature liver, including glucose metabolism by HNF4a (39), HNF1a (25), HNF6 (22), or cholesterol and bile acid metabolism by HNF6 (41) and Foxa2 (7).

The liver is the largest internal organ of the body and is composed of two types of epithelial cells: 1) hepatocytes and 2) cholangiocytes (2). Hepatocytes account for ∼70% and cholangiocytes for 3–5% of the endogenous liver cell population. Cholangiocytes [also known as biliary epithelial cells (BEC)] populate the bile ducts (2). The intrahepatic bile duct size ranges from large ducts emanating from the confluence of the extrahepatic bile ducts at the liver hilum to progressively smaller intrahepatic ducts (19). In experimental models, small BEC refer to BEC lining the small bile ducts, whereas large BEC line larger biliary ducts (3, 15). Small and large rodent BEC have distinct morphometry (15), gene expression profile (38), as well as proliferative, apoptotic, and secretory responses to experimental stimuli (1, 14, 15). This BEC heterogeneity is clinically relevant in that the large and small ducts are differentially targeted in human cholangiopathies (37), stressing the importance of understanding the molecular mechanism regulating their functional diversities.

Since hepatocytes and BEC embryonic cellular origins are from multipotent hepatoblasts (34), it is not surprising that they have overlapping physiological function, such as solute secretion and metabolic activities (23), and are, therefore, likely to share transcriptional regulation. Compared with BEC, the role of HNF in the molecular regulation of differentiated liver-specific genes in hepatocytes is better understood (10, 36). Among HNFs, the current body of data suggest that HNF6 is a dominant BEC-enriched transcription factor. It is critical to the early commitment of hepatoblasts to the biliary epithelial lineage as mutant mice with global HNF6 deletion exhibit biliary duct malformations and early mortality from cholestasis (9). Our laboratory has shown that HNF6 transcription factor is also highly expressed in BEC in the mature mouse liver and can negatively regulate BEC proliferation during early bile duct ligation injury (17). The transcriptional regulation of hepatic target genes by HNF6 is broad, involving gene with metabolic and transport function (22, 29, 35, 41), as well as other HNF, such as HNF4a (21), HNF1b (9), and Foxa2 (21), suggesting that HNF6 can comprehensively regulate the biliary cell molecular signature, and that enforced HNF6 expression in large and small biliary cells would elucidate the molecular basis for their heterogeneity. To further our understanding of BEC gene regulation, we herein test the hypothesis that the biliary cell-enriched transcription factor HNF6 differentially regulates the large and small BEC downstream transcriptional events. We first characterized the expression profile of HNF and selected HNF target genes in the SV40 large T antigen-transformed and immortalized large and small BEC (SV40LG and SV40SM, respectively). We compared changes in the BEC transcriptional response to increasing HNF6 expression in these cell lines using recombinant adenoviral vectors expressing HNF6 cDNA (AdHNF6). We evaluated representative in vivo HNF6 target gene expression in large and small BEC isolated from liver tissues following administration of HNF6-enhancing vector growth hormone (GH), a known STAT5-mediated transcriptional activator of HNF6 promoter (21).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

SV40LG and SV40SM BEC were derived from BALB/c mice and characterized as previously described (38). The construction and preparation of the replication-defective recombinant adenoviral vectors expression of the bacterial LacZ (AdLacZ) or mouse HNF6 cDNA (AdHNF6) have been reported (41). HNF6, HNF1a, HNF4a, Foxa2, C/EBPb, and β-actin antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Technology.

Cell culture.

As previously described (15), cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere in D-MEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% pen/strep, and 1% l-glutamine. For experiments (n = 4), cells were plated at 5 × 106 cells in 10-cm culture dishes for mock infection or infection with a multiplicity of infection of 35 infectious units of AdHNF6 or AdLacZ in 1 ml of media for 60 min, following which media was added to a final 10-ml volume. Cells were harvested after 24 h of infection and washed three times with PBS to remove residual virus for subsequent total RNA extraction.

Animal procedures.

Six- to eight-week-old male CD1 mice were kept in a 12:12-h light-dark-cycles with free access to standard chow and water. All animals received humane care, according to the criteria outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the National Academy of Sciences and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The animal care and use section of the NIH funding application was reviewed in accordance with the policies of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and approved. Mice received an initial intraperitoneal injection of human recombinant GH (obtained from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases National Hormone and Peptide Program) at 4 μg/g body wt, followed by a 3 μg/g body wt injection every 6 h and killed after 24 h for BEC isolation and purification.

BEC isolation.

The procedure was described previously (2) but briefly, following in situ collagenase perfusion, in three different experiments, the cholangiocyte mixture from the biliary tracts were separated into large and small cells by counterflow elutriation (3) with further purification by immunoaffinity using immunomagnetic beads. Glucose-6-phosphatase and vimentin immunostaining was done to rule out contamination by hepatocytes and mesenchymal cells, respectively (1).

Gene analyses.

Total liver RNA was extracted using RNA-STAT-60 (Tel-Test “B”, Friendswood, TX). Following DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX) digestion, cDNA was synthesized using the cDNA Synthesis Kit (Biorad, Hercules, CA) and purified through Qiagen column. Reactions were amplified using the appropriate primer sets and analyzed in triplicate using a MyiQ Single Color Real-Time PCR Detection System (Biorad). The relative expression of the genes was calculated by a mathematical delta-delta method developed by PE Applied Biosystems. Levels were reported after normalization to housekeeping gene cyclophilin for each gene. The primers sequences for mouse genes are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for mouse genes

| Primers |

||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

| Transcription factors | ||

| HNF1a | 5′-TTC TAA GCT GAG CCA GCT GCA GAC G-3′ | 5′-GCT GAG GTT CTC CGG CTC TTT CAG A-3′ |

| HNF1b | 5′-GAA AGC AAC GGG AGA TCC TC-3′ | 5′-CCT CCA CTA AGG CCT CCC TC-3′ |

| HNF6 | 5′-GGT CTG GGC AGC ATT CAC AAC-3′ | 5′-CAG GGT GGT GGG CTT CAA AG-3′ |

| HNF4a | 5′-ACA CGT CCC CAT CTG AAG-3′ | 5′-CTT CCT TCT TCA TGC CAG-3′ |

| C/EBPb | 5′-ATC GAC TTC AGC CCC TAC CT-3′ | 5′-GGC TCA CGT AAC CGT AGT CG-3′ |

| Foxa2 | 5′-CCA TCA GCC CCA CAA AAT G-3′ | 5′-CCA AGC TGC CTG GCA TG-3′ |

| Hepatic function genes | ||

| Glucokinase | 5′-CCT GGG CTT CAC CTT CTC CTT-3′ | 5′-GAG GCC TTG AAG CCC TTG GT-3′ |

| Mrp2 | 5′-AGA GGG CGG TGA CAA CCT GAG-3′ | 5′-CGG ATG GTC GTC TGA ATG AGG-3′ |

| Ntcp | 5′-ATG ACC ACC TGC TCC AGC TT-3′ | 5′-GCC TTT GTA GGG CAC CTT GT-3′ |

| Oatp1 | 5′-AAT TTG GGA AGA GTG GCC TT | 5′-TGG AGT CAA TGC AAA AAC CA |

| TGFb2R | 5′-CGG AAA TTC CCA GCT TCT GG-3′ | 5′-TTT GGT AGT GTT CAG CGA GC-3′ |

Sequences are annotated with the binding position upstream of the transcription start site. See text for definitions of gene acronyms.

Western blot assays.

Crude protein extracts were prepared from AdHNF-6 infected SV40LG and SV40SM cells, and protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). HNF6, HNF1a, HNF4a, Foxa2, C/EBPb, and β-actin immune complexes were detected with horseradish-conjugated secondary antibody (Fisher), followed by chemiluminescence (ECL + plus, Amersham Biosciences).

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed as means ± SD, unless otherwise indicated. Intergroup differences were evaluated by analysis of variance for repeated measures. A P value of <0.05 is considered to be significant. All statistical analyses were performed with the software SPSS.

RESULTS

Constitutive expression of hepatocyte transcription factors in SV40LG and SV40SM cells.

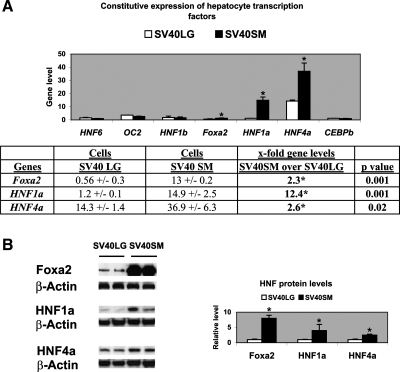

The SV40 large T antigen-transformed large (SV40LG) and small BEC (SV40SM), derived from large and small bile ducts of mouse liver, were previously characterized (38) and shown to display morphological, phenotypic, and functional characteristics of freshly isolated large and small cholangiocytes (15). The baseline profile in the expression of hepatocyte transcription factors HNF6 (OC1) and its paralog OC2 (18), HNF1b, HNF1a, HNF4a, Foxa2, and C/EBPb was assessed by real-time PCR in SV40LG and SV40SM cell lines. Figure 1 illustrates that, while HNF6, OC2, HNF1b, and C/EBPb gene expression levels were comparable in small and large BEC, Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a levels were 2.3-fold (P = 0.001), 12.4-fold (P = 0.001), and 2.6-fold (P = 0.02), respectively, higher in SV40SM cells. Consistent with the fact that HNF expression is primarily regulated at the transcriptional level, Western blotting for protein expression (Fig. 1B) exhibits the same pattern of higher Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a levels in SV40SM cells.

Fig. 1.

Constitutive expression of hepatocyte transcription factors in SV40LG (large) and SV40SM (small) cell lines. A: real-time PCR bar graph of HNF6, OC2, HNF1a, HNF1b, Foxa2, HNF4a, and C/EBPb gene levels (after normalization to housekeeping gene cyclophilin), showing higher Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a in SV40SM over SV40LG cells. The table shows Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNf4a gene levels and the x-fold higher expression with the corresponding P values in SV40SM over SV40LG cells. B: Western blotting micrographs of Foxa2, HNF1a, HNF4a, and β-actin protein expression in SV40LG and SV40SM cells. Bar graph of densitometry analysis of the immune complexes after normalization with β-actin shows higher Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a expression levels in SV40SM cells relative to SV40LG cells. *P values of significance at <0.05. See text for definitions of gene acronyms used in figures.

Constitutive expression of HNF target genes in SV40LG and SV40SM cells.

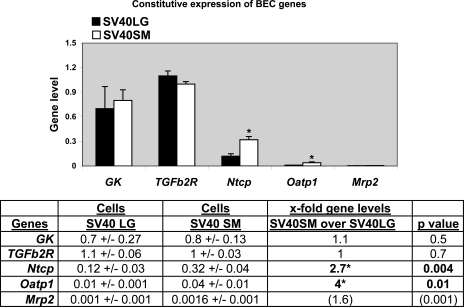

Intrahepatic bile acid transport is among many of BEC important functions (26). We next examined the expression of hepatic bile acid transport genes, which are known target genes for HNF: ntcp (the Na+-dependent taurocholate cotransport peptide for bile acid import, also known as slc10a1) is transcriptionally regulated by HNF1a (13) and HNF4a (13, 16); mrp2 (the multidrug resistance-associated protein for xeno- and endobiotics bile acid export, also known as abcc2) by HNF1a and HNF4a (20, 32), and possibly by Foxa2 (7); and oatp1 (the organic anion transporter for basolateral bile acid uptake, also known as slc21a1) by HNF1a (4, 27) and HNF4a (11, 16). Since the above data showed that SV40LG and SV40SM cells have differential expression of Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a transcription factors, we next sought to characterize the baseline expression of HNF6, Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a target genes. As control target genes for HNF6, we assayed glucokinase (GK, previously shown to be positively regulated by HNF6) (22) and TGFb2R (shown to be negatively regulated by HNF6) (31, 40) and did not find differences in their baseline expression (Fig. 2). HNF1a/HNF4a target genes ntcp and oatp1 are expressed at 2.7-fold (P = 0.004) and 4-fold higher levels (P = 0.01) in SV40SM than SV40LG cells. Since mrp2 expression levels were low, the biological significance of a statistical difference in the expression between SV40LG and SV40SM cells (1.6-fold higher in SV40SM, P = 0.001) is not clear.

Fig. 2.

Constitutive expression of target genes in SV40LG and SV40SM cell lines. Real-time PCR bar graph shows glucokinase (GK), TGFb2R, ntcp, oatp1, and mrp2 gene levels, and table shows ntcp, oatp1a1, and mrp2 gene levels and the x-fold higher expression in SV40SM over SV40LG cells with the corresponding P values. *Significant P values.

Effects of increasing HNF6 expression in BEC on known HNF6 target genes.

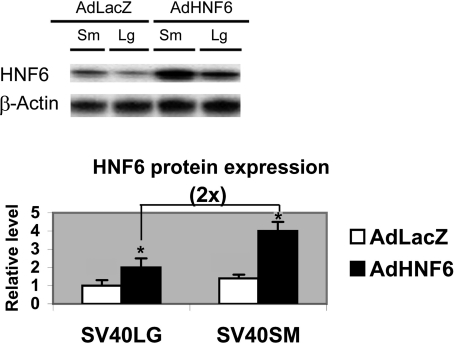

Since HNF6 is a major BEC-enriched transcription factor, cells were mock infected or treated with AdLacZ and AdHNF6 to assess if increasing HNF6 expression can transcriptionally alter BEC gene profiles. Since mock-infected cells have comparable gene expression levels as AdLacZ-infected cells (data not shown), the results comparing AdLacZ- against AdHNF6-infected cells are presented (Table 2). Previous studies have shown that AdHNF6 tail vein injection effectively increased HNF6 gene and nuclear protein expression in both hepatocytes and bile ducts (17). Following AdHNF6 treatment, HNF6 gene expression was also appropriately increased in AdHNF6-SV40LG and AdHNF6-SV40SM cells relative to AdLacZ-treated control by 1,450-fold and 2,608-fold, respectively, corresponding to a 1.4-fold higher HNF6 expression in AdHNF6-SV40SM relative to AdHNF6-SV40LG (P = 0.02) (Table 1). Western blotting of AdLacZ- and AdHNF6-infected SV40LG and SV40SM cells confirmed a similar pattern of higher HNF6 protein expression in AdHNF6-SV40SM cells (Fig. 3). HNF6 target gene TGFb2R (Table 2) changed minimally in AdHNF6-infected SV40LG, but, consistent with the higher expression of HNF6 in AdHNF6-SV40SM cells, its level is 1.6-fold more diminished in AdHNF6-SV40SM relative to AdHNF6-SV40LG cells (P = 0.03). HNF6 target gene glucokinase response was more dramatic, with a 16- and 38-fold upregulation following AdHNF6 infection over AdLacZ control in AdHNF6-SV40LG and AdHNF6-SV40SM cells, respectively, corresponding to an 1.8-fold higher (P = 0.02) glucokinase expression in AdHNF6-SV40SM cells compared with AdHNF6-SV40LG cells. These results demonstrate that BEC and hepatocytes display similar HNF6 target gene response, but most of all, that small BEC have higher reactivity to HNF6 transcriptional regulation.

Table 2.

Effect of AdHNF6 on HNF6 and HNF6 target genes

| AdLacZ | AdH6 | x-Fold AdHNF6 vs. AdLacZ | x-fold AdHNF6 SV40SM vs. AdHNF6 SV40LG | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNF6 | |||||

| SV40LG | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 725 ± 109 | 1,450 | ||

| SV40SM | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 1043 ± 98 | 2,608 | 1.4 | 0.02 |

| GK | |||||

| SV40LG | 0.8 ± 0.37 | 13 ± 1.9 | 16 | ||

| SV40SM | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 23 ± 4.6 | 38 | 1.8 | 0.02 |

| TGFb2R | |||||

| SV40LG | 1 ± 0.14 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.8 | ||

| SV40SM | 1 ± 0.11 | 0.5 ± 00.1 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.03 |

SV40LG and SV40SM cells were treated with AdLacZ or AdHNF6 for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted for real-time PCR analysis of HNF6, cyclophilin, and HNF6-target genes glucokinase (GK) and TGFb2R. Table shows gene levels after normalizing with housekeeping gene cyclophilin, the x-fold changes in gene level between AdLacZ-treated cells and AdHNF6-treated cells, and the x-fold difference between AdHNF6-treated SV40SM and AdHNF6-treated SV40LG cells with its corresponding P values. See text for definitions of gene acronyms.

Fig. 3.

Effect of adenoviral HNF6 (AdHNF6) treatment on SV40 biliary epithelial cell (BEC) HNF6 protein expression. SV40LG and SV40SM cells were infected with AdLacZ and AdHNF6 for 24 h. Micrograph shows Western blotting results of HNF6 protein expression in SV40SM (Sm) and SV40LG (Lg) cells. Bar graph shows densitometry results of the immune complexes after normalization to β-actin with values reported relative to AdHNF6-infected SV40LG cells, showing a twofold higher HNF6 expression in AdHNF6-SV40SM over AdHNF6-SV40LG cells. *Significant P values.

Effects of increasing HNF6 BEC expression on other HNF and HNF-regulated bile transport target genes.

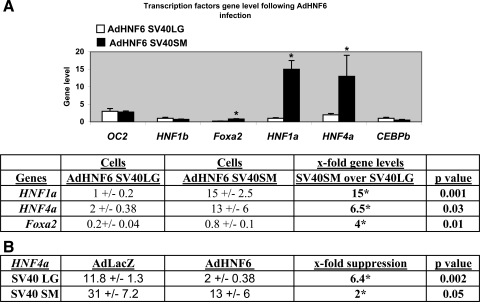

We next evaluated the effect of HNF6 overexpression on the transcriptional response of other known HNF6-dependent HNF [such as HNF4a (21), HNF1b (9), and Foxa2 (21)] in BEC (Fig. 4). Despite an unexpected AdHNF6-associated suppression of endogenous HNF4a gene levels (Fig. 4B) in both SV40SM (by 2-fold, P = 0.05) and SV40LG cells (by 6.4-fold, P = 0.002), the net effect of higher HNF6 expression in AdHNF6-SV40SM over AdHNF6-SV40LG BEC is illustrated in Fig. 4A, demonstrating that the final Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a expression in AdHNF6-infected small BEC remained markedly higher than in AdHNF6-infected large BEC, with a 4-fold (P = 0.01), 15-fold (P = 0.001), and 6.5-fold (P = 0.03) difference, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Net effect of AdHNF6 treatment on SV40 BEC hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF) expression. A: bar graph shows OC2, HNF1b, Foxa2, HNF1a, HNF4a, and C/EBPb gene levels for AdHNF6-infected SV40LG and AdHNF6-infected SV40SM cells. *Significant differences in levels between AdHNF6 SV40LG vs. AdHNF6 SV40SM cells. Table shows gene levels and the x-fold higher expression levels of HNFa1, HNF4a, and Foxa2 in AdHNF6-SV40SM relative to AdHNF6-SV40LG cells with the corresponding P values. B: table shows HNF4a gene levels in AdLacZ- and AdHNF6-infected SV40LG and SV40SM cells and x-fold suppression (with the corresponding P values) in gene levels of AdHNF6-infected SV40 cells relative to AdLacZ-infected cells. *Significant differences in levels between AdLacZ and AdHNF6-infected cells.

Effects of AdHNF6 treatment on HNF-regulated bile transport target genes.

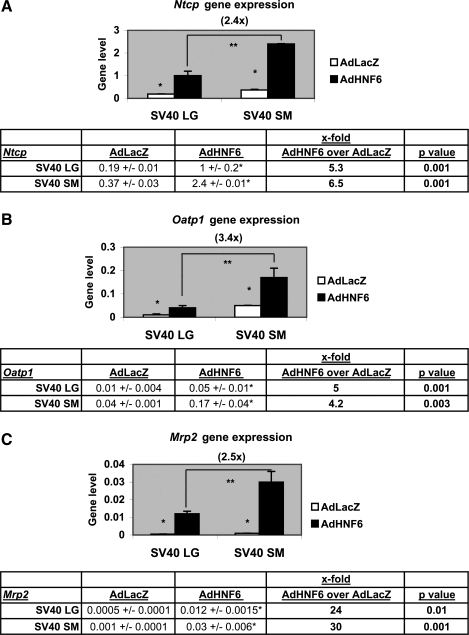

As seen in Fig. 5, the response to AdHNF6 infection in both SV40LG and SV40SM cells of the biliary genes was characterized in AdHNF6-SV40 cells relative to AdLacZ-SV40 cells by upregulation of ntcp, oatp1, and mrp2 expression with enhanced ntcp (5.3-fold up, P = 0.001, Fig. 5A), oatp1 (5-fold up, P = 0.001, Fig. 5B), and mrp2 (24-fold up, P = 0.01, Fig. 5C) expression in AdHNF6-SV40 LG cells, and increased ntcp by 6.5-fold (P = 0.001, Fig. 5A), oatp1 by 4.2-fold (P = 0.003, Fig. 5B), and mrp2 by 30-fold (P = 0.001, Fig. 5C) in AdHNF6-SV40SM cells.

Fig. 5.

Effect of AdHNF6 treatment on SV40 BEC gene expression. SV40LG and SV40SM cells were infected with AdLacZ and AdHNF6 for 24 h. Bar graphs show gene levels for ntcp (A), oatp1 (B), and mrp2 (C) in AdLacZ- and AdHNF6-infected SV40LG and SV40SM cells. *Significant differences in levels between AdLacZ and AdHNF6-infected cells. **Significantly higher ntcp, oatp1, and mrp2 levels (2.4-, 3.4-, and 2.5-fold, respectively) in AdHNF6-infected SV40SM cells compared with AdHNF6-infected SV40LG. The tables show gene levels of infected cells with the corresponding P values.

The net effects of AdHNF6 infection of higher HNF6, Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a expression in AdHNF6-SV40SM relative to AdHNF6-SV40LG were associated with correspondingly higher levels of ntcp (2.4-fold, P = 0.02), oatp1 (3.4-fold, P = 0.006), and mrp2 (2.5-fold, P = 0.02) in AdHNF6-SV40SM compared with AdHNF6-SV40LG cells.

Effects of increasing in vivo HNF6 expression on target gene transcription.

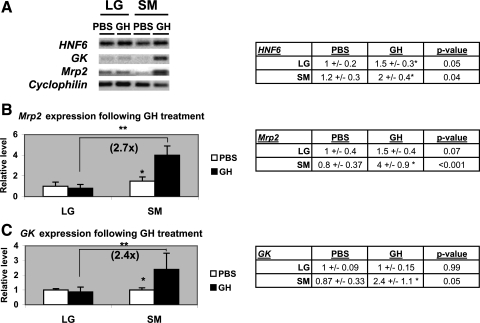

To evaluate HNF6 in vivo target gene transcriptional response, hepatic HNF6 expression was physiologically enhanced by treatment with recombinant GH, a known STAT5-mediated transcriptional activator of HNF6 promoter (21). The mrp2 gene expression was selected since, among the above bile transport gene-positive transcriptional responses to AdHNF6 treatment, mrp2 levels were the most dramatically enhanced (by >20-fold in both SV40LG and SV40SM cells). Large and small BEC were isolated for gene expression analyses following 24 h of GH administration (Fig. 6). As expected from our laboratory's previous work in GH-treated liver (40, 41), HNF6 gene expression was appropriately increased in large (by 1.5-fold) and small BEC (by 1.7-fold) relative to PBS control (Fig. 6A). Consistent with our laboratory's previous findings that SV40SM cell lines displayed a magnified responsiveness to HNF6 induction relative to SV40LG cells, in vivo GH-treated small BEC had significant increases of glucokinase (2.8-fold, P = 0.05; Fig. 6B) and mrp2 (5-fold, P < 0.001; Fig. 6A) gene expression over PBS-treated small BEC. Of note, unlike our laboratory's previous SV40 cell data showing enhanced glucokinase (Table 1) and mrp2 response (Fig. 5C) to AdHNF6 infection in SV40LG cells, this increase was not seen in GH-treated large BEC, possibly because GH-induced HNF6 in vivo expression was less dramatic. Compared with GH-treated large BEC, glucokinase and mrp2 levels were 2.4-fold (P = 0.04) and 3.4-fold (P < 0.001), respectively, higher in GH-treated small BEC than GH-treated large BEC, showing that the same pattern of small BEC in vitro sensitivity in its transcriptional response to HNF6 was also seen in vivo.

Fig. 6.

Effects of growth hormone (GH)-mediated HNF6 increases on BEC gene expression. LG and SM BEC were isolated from PBS- or GH-treated mice (n = 3). Total RNA was extracted for real-time PCR analyses of HNF6, mrp2, GK, and cyclophilin. A: micrograph shows representative real-time PCR gel results, and table shows HNF6 gene levels with the corresponding P values. B and C: bar graphs show gene levels for mrp2 (B) and GK (C) in PBS- and GH-treated BEC. *Significant differences in levels between PBS- vs. GH-treated BEC. **Significantly higher mrp2 and GK levels (2.7- and 2.4-fold, respectively) in GH-treated SM relative to LG cholangiocytes. Tables show the gene levels with the corresponding P values.

DISCUSSION

The concept of biliary cell morphological and functional heterogeneity originating from the early work in rat biliary model system (2, 6) has progressively gained acceptance with many comprehensive reviews on this subject (14, 19, 28). Since the liver epithelial cell phenotype and function are determined by the spectrum of hepatic-specific genes, whose expression are regulated by liver-enriched HNFs, an evaluation of the BEC transcriptional characteristics is a logical start in furthering our understanding of basic molecular mechanism for BEC diversities.

We found that the small and large BEC display distinctive constitutive levels of hepatocyte transcription factors and biliary cell-enriched gene expression. The small SV40 BEC exhibited higher expression of Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a hepatocyte transcription factors. This transcriptional profile likely provides the molecular basis for higher constitutive expression of HNF1a-, HNF4a-, and Foxa2-candidate target genes such as ntcp, oatp1, and mrp2 in SV40SM cells. The dominance of HNF1a and HNF4a as BEC-enriched transcription factors in small biliary cells is consistent with previous genomewide promoter analyses of human hepatocytes, showing that HNF1a, HNF4a, and HNF6 are the core group of HNFs in orchestrating the transcription of a wide array of differentiated hepatic genes (29). Of great interest to us, it remains to be seen in future experiments whether large biliary cell could be induced into acquiring the same small BEC molecular repertoire upon enforced expression of these HNF1a-, HNF4a-, and Foxa2-enriched hepatocyte transcription factors, and, conversely, whether the small biliary cell would lose its constitutive molecular imprint following reversal of its HNF profile.

Small BEC also displayed a higher transcriptional response level to HNF6 treatment. Since HNF6 transcriptional regulation of target gene also involves other HNF, such as HNF4a (21), HNF1b (9), and Foxa2 (21), we first evaluated HNF response patterns to AdHNF6 in SV40 BEC. Consistent with the known cross-regulatory transcriptional network among HNFs, AdHNF6 treatment affected the HNF profile of BEC, albeit with a negative effect on HNF4a transcription for both large and small SV40 BECs. A simple explanation for this unexpected suppressive response is that previous results demonstrating hepatic HNF4a-positive transcriptional response to HNF6 could not be extrapolated to that of BEC. Alternatively, the approach of using HNF6 adenoviral expression vectors to transduce HNF6 expression in BEC cell lines limits this analysis to HNFs as cell-autonomous regulators outside the context of in vivo systems. An evaluation of in vivo cholangiocytes' HNF and target gene response are pending to shed light on the true physiological significance of these in vitro findings. The relevance of the suppressive transcriptional response of HNF4a to HNF6 overexpression in SV40BEC is unclear, but does not diminish the remarkable findings that Foxa2, HNF1a, and HNF4a remain dominant transcription factors in the AdHNF6-infected small BEC, with commensurate higher expression levels of their target genes, ntcp, oatp1, and mrp2.

Following AdHNF6 infection, despite unchanged Foxa2 and HNF1a, yet suppressed HNF4a expression, HNF1a-, HNF4a-, and/or Foxa2 target gene ntcp, oatp1, and mrp2 levels were significantly enhanced in both large and small SV40 cells, suggesting that the response pattern of these bile transport genes is more complex than just straightforward transcriptional regulation by HNF1a, HNF4, Foxa2, or HNF6, since HNFs commonly function in a cross-regulatory fashion. With respect to ntcp, transient transfection of CMV-HNF6 expression vectors in HepG2 cell lines did not activate ntcp reporter gene constructs (data not shown). Furthermore, prior AdHNF6 liver infection by tail vein injection did not enhance whole liver ntcp or mrp2 expression (40), suggesting that ntcp and mrp2 gene response cannot be directly attributed to simple HNF6 transcriptional effects on their promoters. Since HNF commonly participate in a transcriptional network with the proper complement of HNF and cross-interaction among HNFs controlling the target gene profile, BEC upregulation of ntcp and mrp2 expression following AdHNF6 infection could be due to potential molecular synergistic interactions between HNF6 and HNF1a/HNF4a/Foxa2, perhaps through the recruitment of coactivators to orchestrate target gene activation. A precedence for this mechanism has been described with HNF6-HNF4a activation of glucose-6-phosphatase promoter by joint engagement of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (5); or with HNF6-C/EBPa recruitment of the CREB binding protein CBP coactivator to enhance Foxa2 promoter activities (33, 42). Of note, oatp1 hepatic gene expression and oatp1 promoter occupancy by HNF6 nuclear proteins are severely diminished in HNF6 liver conditional null mice (manuscript submitted), suggesting that oatp1 is an authentic HNF6 target gene. Upregulation of oatp1 expression in AdHNF6 treated cells is consistent with direct transcriptional stimulation of oatp1 by HNF6 or HNF1a-HNF6 interaction.

Gene profiling (12, 38) and functional studies (14) have shown that large BEC participate in choleresis, immune, and hormone regulation. Our gene expression data suggest that small BEC may carry a more substantial role in the transport of bile acid and bile acid constituents than large BEC. Further analyses for the respective contribution of these cell populations to the liver adaptive response to injury in experimental models of cholestasis are pending to assess the physiological significance of these observations.

Overall, the results lend support to our hypothesis that the large and small cholangiocytes have different transcriptional characteristics, thus providing a potential mechanistic basis for their functional heterogeneity. The data also imply that the well-described intricate interactions among hepatocyte transcription factors in coordinating the transcriptional profile of end genes in hepatocytes may also exist in BECs. Further characterization of the complexities of promoter regulation of biliary-enriched genes in the large and small BECs will enhance our understanding of their differential susceptibility to disease processes in an effort toward modulating their individual pathological responses.

GRANTS

This work is funded by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Grant R21 DK070784-02 to A. Holterman, by the Dr. Nicholas C. Hightower Centennial Chair of Gastroenterology from Scott & White, the VA Research Scholar Award, a VA Merit Award, and NIDDK Grants DK58411 and DK76898.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Alpini G, Glaser S, Robertson W, Phinizy JL, Rodgers RE, Caligiuri A, LeSage G. Bile acids stimulate proliferative and secretory events in large but not small cholangiocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 273: G518–G529, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpini G, Prall RT, LaRusso NF. The pathobiology of biliary epithelia. In: The Liver; Biology & Pathobiology, edited by Arias IM, Boyer JL, Chisari FV, Fausto N, Jakoby W, Schachter D, Shafritz DA. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001, p. 421–435 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alpini G, Roberts S, Kuntz SM, Ueno Y, Gubba S, Podila PV, LeSage G, LaRusso NF. Morphological, molecular, and functional heterogeneity of cholangiocytes from normal rat liver. Gastroenterology 110: 1636–1643, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrejko KM, Raj NR, Kim PK, Cereda M, Deutschman CS. IL-6 modulates sepsis-induced decreases in transcription of hepatic organic anion and bile acid transporters. Shock 29: 490–496, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaudry JB, Pierreux CE, Hayhurst GP, Plumb-Rudewiez N, Weiss MC, Rousseau GG, Lemaigre FP. Threshold levels of hepatocyte nuclear factor 6 (HNF-6) acting in synergy with HNF-4 and PGC-1alpha are required for time-specific gene expression during liver development. Mol Cell Biol 26: 6037–6046, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benedetti A, Bassotti C, Rapino K, Marucci L, Jezequel AM. A morphometric study of the epithelium lining the rat intrahepatic biliary tree. J Hepatol 24: 335–342, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bochkis IM, Rubins NE, White P, Furth EE, Friedman JR, Kaestner KH. Hepatocyte-specific ablation of Foxa2 alters bile acid homeostasis and results in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Med 14: 828–836, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clotman F, Jacquemin P, Plumb-Rudewiez N, Pierreux CE, Van der Smissen P, Dietz HC, Courtoy PJ, Rousseau GG, Lemaigre FP. Control of liver cell fate decision by a gradient of TGF beta signaling modulated by Onecut transcription factors. Genes Dev 19: 1849–1854, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clotman F, Lannoy VJ, Reber M, Cereghini S, Cassiman D, Jacquemin P, Roskams T, Rousseau GG, Lemaigre FP. The onecut transcription factor HNF6 is required for normal development of the biliary tract. Development 129: 1819–1828, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV, Holterman AX, Wang X. Transcription factors in liver development, differentiation, and regeneration. Hepatology 38: 1331–1347, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietrich CG, Martin IV, Porn AC, Voigt S, Gartung C, Trautwein C, Geier A. Fasting induces basolateral uptake transporters of the SLC family in the liver via HNF4alpha and PGC1alpha. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 293: G585–G590, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukushima K, Ueno Y. Bioinformatic approach for understanding the heterogeneity of cholangiocytes. World J Gastroenterol 12: 3481–3486, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geier A, Martin IV, Dietrich CG, Balasubramaniyan N, Strauch S, Suchy FJ, Gartung C, Trautwein C, Ananthanarayanan M. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha is a central transactivator of the mouse Ntcp gene. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 295: G226–G233, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser S, Francis H, Demorrow S, Lesage G, Fava G, Marzioni M, Venter J, Alpini G. Heterogeneity of the intrahepatic biliary epithelium. World J Gastroenterol 12: 3523–3536, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser SS, Gaudio E, Rao A, Pierce LM, Onori P, Franchitto A, Francis HL, Dostal DE, Venter JK, DeMorrow S, Mancinelli R, Carpino G, Alvaro D, Kopriva SE, Savage JM, Alpini GD. Morphological and functional heterogeneity of the mouse intrahepatic biliary epithelium. Lab Invest 89: 456–469, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayhurst GP, Lee YH, Lambert G, Ward JM, Gonzalez FJ. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha (nuclear receptor 2A1) is essential for maintenance of hepatic gene expression and lipid homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol 21: 1393–1403, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holterman AX, Tan Y, Kim W, Yoo KW, Costa RH. Diminished hepatic expression of the HNF-6 transcription factor during bile duct obstruction. Hepatology 35: 1392–1399, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacquemin P, Lannoy VJ, Rousseau GG, Lemaigre FP. OC-2, a novel mammalian member of the ONECUT class of homeodomain transcription factors whose function in liver partially overlaps with that of hepatocyte nuclear factor-6. J Biol Chem 274: 2665–2671, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanno N, LeSage G, Glaser S, Alvaro D, Alpini G. Functional heterogeneity of the intrahepatic biliary epithelium. Hepatology 31: 555–561, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitanaka S, Sato U, Igarashi T. Regulation of human insulin, IGF-I, and multidrug resistance protein 2 promoter activity by hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)-1beta and HNF-1alpha and the abnormality of HNF-1beta mutants. J Endocrinol 192: 141–147, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lahuna O, Rastegar M, Maiter D, Thissen JP, Lemaigre FP, Rousseau GG. Involvement of STAT5 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 5) and HNF-4 (hepatocyte nuclear factor 4) in the transcriptional control of the hnf6 gene by growth hormone. Mol Endocrinol 14: 285–294, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lannoy VJ, Decaux JF, Pierreux CE, Lemaigre FP, Rousseau GG. Liver glucokinase gene expression is controlled by the onecut transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor-6. Diabetologia 45: 1136–1141, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazaridis KN, Strazzabosco M, Larusso NF. The cholangiopathies: disorders of biliary epithelia. Gastroenterology 127: 1565–1577, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee CS, Friedman JR, Fulmer JT, Kaestner KH. The initiation of liver development is dependent on Foxa transcription factors. Nature 435: 944–947, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee YH, Magnuson MA, Muppala V, Chen SS. Liver-specific reactivation of the inactivated Hnf-1alpha gene: elimination of liver dysfunction to establish a mouse MODY3 model. Mol Cell Biol 23: 923–932, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu JJ, Glickman JN, Masyuk AI, Larusso NF. Cholangiocyte bile salt transporters in cholesterol gallstone-susceptible and resistant inbred mouse strains. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 23: 1596–1602, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maher JM, Slitt AL, Callaghan TN, Cheng X, Cheung C, Gonzalez FJ, Klaassen CD. Alterations in transporter expression in liver, kidney, and duodenum after targeted disruption of the transcription factor HNF1alpha. Biochem Pharmacol 72: 512–522, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marzioni M, Glaser SS, Francis H, Phinizy JL, LeSage G, Alpini G. Functional heterogeneity of cholangiocytes. Semin Liver Dis 22: 227–240, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Odom DT, Zizlsperger N, Gordon DB, Bell GW, Rinaldi NJ, Murray HL, Volkert TL, Schreiber J, Rolfe PA, Gifford DK, Fraenkel E, Bell GI, Young RA. Control of pancreas and liver gene expression by HNF transcription factors. Science 303: 1378–1381, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parviz F, Matullo C, Garrison WD, Savatski L, Adamson JW, Ning G, Kaestner KH, Rossi JM, Zaret KS, Duncan SA. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha controls the development of a hepatic epithelium and liver morphogenesis. Nat Genet 34: 292–296, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plumb-Rudewiez N, Clotman F, Strick-Marchand H, Pierreux CE, Weiss MC, Rousseau GG, Lemaigre FP. Transcription factor HNF-6/OC-1 inhibits the stimulation of the HNF-3alpha/Foxa1 gene by TGF-beta in mouse liver. Hepatology 40: 1266–1274, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qadri I, Hu LJ, Iwahashi M, Al-Zuabi S, Quattrochi LC, Simon FR. Interaction of hepatocyte nuclear factors in transcriptional regulation of tissue specific hormonal expression of human multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (abcc2). Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 234: 281–292, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rausa FM, 3rd, Hughes DE, Costa RH. Stability of the hepatocyte nuclear factor 6 transcription factor requires acetylation by the CREB-binding protein coactivator. J Biol Chem 279: 43070–43076, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raynaud P, Carpentier R, Antoniou A, Lemaigre FP. Biliary differentiation and bile duct morphogenesis in development and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samadani U, Costa RH. The transcriptional activator hepatocyte nuclear factor 6 regulates liver gene expression. Mol Cell Biol 16: 6273–6284, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schrem H, Klempnauer J, Borlak J. Liver-enriched transcription factors in liver function and development. I. The hepatocyte nuclear factor network and liver-specific gene expression. Pharmacol Rev 54: 129–158, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strazzabosco M, Fabris L, Spirli C. Pathophysiology of cholangiopathies. J Clin Gastroenterol 39: S90–S102, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ueno Y, Alpini G, Yahagi K, Kanno N, Moritoki Y, Fukushima K, Glaser S, LeSage G, Shimosegawa T. Evaluation of differential gene expression by microarray analysis in small and large cholangiocytes isolated from normal mice. Liver Int 23: 449–459, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Velho G, Froguel P. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY), MODY genes and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Met 23, Suppl 2: 34–37, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang M, Chen M, Zheng G, Dillard B, Tallarico M, Ortiz Z, Holterman AX. Transcriptional activation by growth hormone of HNF-6-regulated hepatic genes, a potential mechanism for improved liver repair during biliary injury in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 295: G357–G366, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang M, Tan Y, Costa RH, Holterman AX. In vivo regulation of murine CYP7A1 by HNF-6: a novel mechanism for diminished CYP7A1 expression in biliary obstruction. Hepatology 40: 600–608, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida Y, Hughes DE, Rausa FM, 3rd, Kim IM, Tan Y, Darlington GJ, Costa RH. C/EBPalpha and HNF6 protein complex formation stimulates HNF6-dependent transcription by CBP coactivator recruitment in HepG2 cells. Hepatology 43: 276–286, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.