Abstract

Cardiac transplantation is indicated for patients with end-stage cardiomyopathy secondary to cardiac sarcoidosis. Although rare, recurrent disease has been reported in two cases. The current report presents a case of recurrent cardiac sarcoidosis in a patient 45 months postorthotopic heart transplantation and 40 months following reactivation of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. The patient was the first to have recurrent disease following an infection that has been proposed to be involved in its pathogenesis. The patient’s interval between transplant and recurrence is the longest reported to date.

Keywords: Cardiac sarcoidosis, Endomyocardial biopsy, Transplantation, Tuberculosis

Abstract

La transplantation cardiaque est indiquée pour les patients ayant une myocardiopathie en phase terminale secondaire à une sarcoïdose cardiaque. Bien que la maladie récurrente soit rare, on en a déclaré deux cas. Le présent rapport expose le cas d’une sarcoïdose cardiaque récurrente chez un patient 45 mois après une greffe cardiaque postorthopédique et 40 mois après la réactivation d’une infection à Mycobacterium tuberculosis latente. Le patient était le premier à avoir une maladie récurrente après une infection qu’on pense impliquée dans sa pathogenèse. L’intervalle qu’a vécu le patient entre la greffe et la récurrence est le plus long à avoir été déclaré jusqu’à présent.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that, in 90% of cases, affects the lungs, intrathoracic lymph nodes, skin and eyes (1). The etiology remains unclear, but it is believed that an immunological response to triggers such as infections and inorganic particles occurs in genetically susceptible individuals (1). Of systemic sarcoidosis patients, 25% present with cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) and only 5% of these patients manifest cardiac-related symptoms (1). In the current report, we present a case of a 58-year-old man who, at heart transplantation, was diagnosed with primary CS. Five months following transplantation, the patient developed a pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) infection. Forty-five months after transplantation, CS was identified on routine endomyocardial biopsy. The present case is the longest reported interval between transplant and CS recurrence, and is the only case in which recurrent sarcoidosis was preceded by Mycobacterium infection.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 58-year-old Pakistani man, with a history of mild left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, dyslipidemia, hypothyroidism and a 35-pack-year smoking history was referred to the Toronto General Hospital (Toronto, Ontario) following a one-month history of dyspnea at rest and a 4.53 kg weight gain. His most recent angiogram was negative for significant coronary artery disease. He denied any previous TB infection or exposures.

On examination, his blood pressure was 94/64 mmHg and his heart rate was 58 beats/min. His jugular venous pressure was 6 cm above the sternal angle. Heart sounds S1, S2 and S3 were split and there was no S4 heart sound. A grade III/VI pansystolic murmur was heard at the apex. His respiratory and abdominal examinations were unremarkable. He had moderate pitting edema. First-degree heart block and right bundle branch block were seen on electrocardiography. Echocardiography demonstrated a dilated LV with an ejection fraction of less than 20%. The LV diastolic filling pattern appeared to be restrictive. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging estimated an LV ejection fraction of 8% and a right ventricular ejection fraction of 21%. The delayed enhancement study demonstrated biventricular patchy areas, compatible with an infiltrative process, and while admitted, he was treated for congestive heart failure (CHF) and underwent automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation. After multiple admissions for CHF, he underwent orthotopic heart transplantation six months later, and was initiated on everolimus, cyclosporine and prednisone. Pathological analysis of the explanted heart showed biventricular hypertrophy and dilation, with patchy areas of fibrosis (Figure 1). Multifocal noncaseating granulomas with inflammatory cells and giant cells were seen in the myocardium and around the epicardial vessels (Figure 2). Specific stains for mycobacterium and fungal infection were negative. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for tuberculosis was not performed because it was not available at the institution, and the provincial laboratory did not agree to have the specimen tested. Because there was no evidence of systemic sarcoidosis based on history and investigations, he was diagnosed with primary CS.

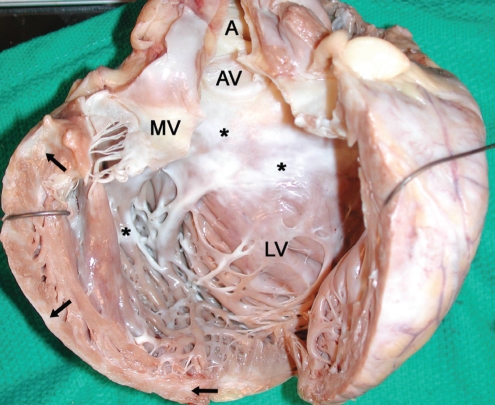

Figure 1).

Gross image of the explanted heart without the atria. The left ventricle (LV) is markedly dilated, measuring 8.0 cm (side-to-side) × 9.0 cm (anteroposterior), with a wall thickness as thin as 0.5 cm. There is significant septal endocardial (asterisks) and myocardial (arrows) fibrosis. The fibrosis is most pronounced in the subaortic region. The aorta (A), aortic valve (AV) and mitral valve (MV) can also be seen

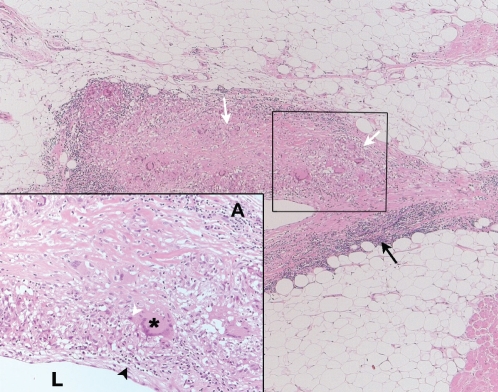

Figure 2).

Microscopic view of an epicardial vein from the explanted heart. Cross-section of an epicardial vein demonstrates noncaseating granulomas within its wall (white arrows). The remainder of the wall shows an extensive, chronic, inflammatory infiltrate (lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages) (black arrow). Inset Higher magnification of the outlined area shows noncaseating granulomas with a multinucleate giant cell (asterisk) surrounded by lymphocytes (black arrowhead) and epithelioid cells (white arrowhead). The lumen (L) and vessel adventitia (A) can be seen. (Hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification ×2.5, inset ×20)

Five months postoperatively, he presented to the hospital with a one-week history of productive cough and fever. A left pleural effusion was seen on a computed tomography scan. Analysis of pleural fluid and bronchoalveolar lavage was negative for infection and malignancy. He underwent left pleural biopsy, which was diagnostic for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by PCR. His induced sputum was also positive. Necrotizing granulomas were seen on microscopic examination of the pleural tissue. Again, PCR for TB was not performed. He was started on quadruple therapy and continued on his immunosuppressant therapy, including prednisone.

An endomyocardial biopsy 40 months later revealed noncaseating granulomas with multinucleate giant cells, consistent with recurrent CS (Figure 3), because repeat investigations did not reveal extracardiac sarcoidosis. Specific stains for infection were negative. A repeat echocardiogram revealed normal LV function, and he remains asymptomatic.

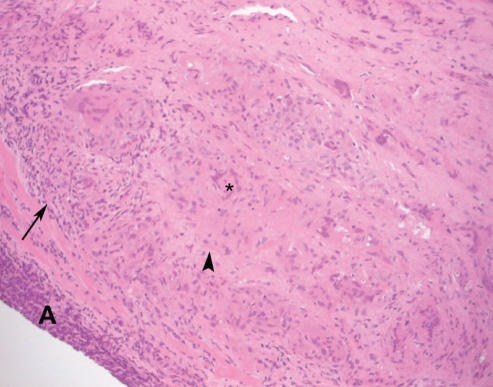

Figure 3).

Microscopic view of the right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy at 45 months postorthotopic heart transplantation. Endomyocardial biopsy demonstrates the presence of a granuloma (arrowhead) and a giant cell (asterisk). A mononuclear infiltrate can be seen within the myocardium (arrows). A Quilty A lesion (A) can also be seen. (Hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification ×40)

DISCUSSION

Primary CS is a rare granulomatous disease that can cause sudden cardiac death by inducing life-threatening arrhythmias. Granulomas are commonly found in the myocardial LV free wall and septum, although the endocardium, pericardium, epicardial vessel walls and valve leaflets can also be affected (1). Most patients with systemic sarcoidosis do not have cardiac manifestations. It is difficult to diagnose clinically because patients can present with nonspecific cardiac findings including atrioventricular or bundle branch block, CHF or sudden death (1). Emphasizing the difficulty of diagnosis, our patient was found to have CS only after examination of the explanted heart.

Despite two reports of recurrent CS in the graft (2,3), patients with end-stage cardiomyopathy may benefit from heart transplantation with no reported recurrence (4). Oni et al (2) and Yager et al (3) have reported cases of recurrent sarcoidosis (34 and 26 years of age) at six and 19 months following transplantation, respectively. Neither patient was on steroids at the time of recurrence and had no decline in LV function. Although our patient also had normal LV function, his time to recurrence was longer (45 months). Because the disease pattern of sarcoidosis is homogeneous and typically affects the LV, the sensitivity of right ventricular biopsy is low (1). Our patient may have had recurrent disease earlier, which was not detected on previous biopsies. Our patient was maintained on a low dose of steroids at the time of recurrence, which may explain why disease was found at 45 months. This suggests that disease recurrence may have a threshold effect, in which granulomas develop when steroid therapy is discontinued.

Our patient is the first with recurrent disease following an acute TB infection. The etiology of sarcoidosis is still unknown, but infections such as TB have been reported to be a possible precipitating agent (1), with PCR techniques identifying Mycobacterium DNA from excised tissue (5). It is postulated that the immune response induces activation of CD4+ T cells, which initiates the formation of granulomas to confine the pathogen, limit inflammation and protect neighbouring normal tissue (1). The two other reported cases of recurrent CS did not have known TB infection before their recurrence. It is plausible that our patient had reactivation of latent TB, given his ethnicity and his immunosuppressive therapy. It is of interest to consider the possibility that a recurrent infection, in a patient with a particular genetic predisposition, reactivated his immune system to initiate the formation of granulomas in his grafted heart. What is most puzzling in the present case is the isolated cardiac involvement before transplantation and at the time of recurrence after his pulmonary TB infection.

CONCLUSIONS

A case of recurrent CS after pulmonary TB infection, 45 months following transplantation, was reported. Despite the recurrence, cardiac transplantation remains an effective treatment modality for patients with advanced cardiac dysfunction. Close surveillance of patients with known CS is necessary following the discontinuation of steroids.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim JS, Judson MA, Donnino R, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis. Am Heart J. 2009;157:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oni AA, Hershberger RE, Norman DJ, et al. Recurrence of sarcoidosis in a cardiac allograft: Control with augmented corticosteroids. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1992;11(2 Pt 1):367–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yager JE, Hernandez AF, Steenbergen C, et al. Recurrence of cardiac sarcoidois in a heart transplant recipient. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1988–90. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valantine HA, Tazelaar HD, Macoviak J, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: Response to steroids and transplantation. J Heart Transplant. 1987;6:244–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saboor SA, McFadden J, Johnson N. Detection of mycobacterial DNA in sarcoidosis and tuberculosis with polymerase chain reaction. Lancet. 1992;339:1012–5. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90535-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]