Abstract

Regeneration requires signaling from a wound site for detection of the wound, and a mechanism that determines the nature of the injury to specify the appropriate regenerative response. Wound signals and tissue responses to wounds that elicit regeneration remain poorly understood. Planarians are able to regenerate from essentially any type of injury and present a novel system for the study of wound responses in regeneration initiation. Newly developed molecular and cellular tools now enable study of regeneration initiation using the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Planarian regeneration requires adult stem cells called neoblasts and amputation triggers two peaks in neoblast mitoses early in regeneration. We demonstrate that the first mitotic peak is a body-wide response to any injury and that a second, local, neoblast response is induced only when injury results in missing tissue. This second response was characterized by recruitment of neoblasts to wounds, even in areas that lack neoblasts in the intact animal. Subsequently, these neoblasts were induced to divide and differentiate near the wound, leading to formation of new tissue. We conclude that there exist two functionally distinct signaling phases of the stem cell wound response that distinguish between simple injury and situations that require the regeneration of missing tissue.

Introduction

All animals suffer risk of injury. Therefore, wound responses are expected to be a common feature of animals throughout the Metazoa. Injuries can elicit a myriad of responses, including cell recruitment, cell proliferation, immunologic responses, and, in some cases, complete regeneration of missing parts. Identification of wound signals and the cellular events that lead to regenerative repair is of fundamental significance. A simple and genetically tractable system in which to study responses to injuries would enable the dissection of the processes that are induced following wounding and that lead to restoration of the injured tissue. Planarians are flatworms that are famous for their ability to regenerate any part of their body (Newmark and Sánchez Alvarado, 2002). The introduction of histological and molecular tools for study of planarian biology—including markers for the stem cells that are involved in regeneration, a complete genome sequence, and strategies for high-throughput RNA interference screening—make them an attractive system for investigation of events that happen at wounds and lead to regeneration.

Planarian regeneration requires adult stem cells known as neoblasts (Reddien and Sánchez Alvarado, 2004). Because injuries in planarians result in dramatic responses tailored to the identity of missing tissue, the signaling that occurs between the injury site and neoblasts is of great interest for understanding stem cells and their role in regeneration. Many tissues in other organisms can regenerate (or replenish cell numbers) through the action of stem and progenitor cells (Barker et al., 2007; Ito et al., 2005; Jiang et al., 2009; Kragl et al., 2009; Morrison et al., 2006; Oshima et al., 2001; Till and McCulloch, 1961). Neoblasts are described as the only known mitotically active somatic cells in the adult planarian (Baguñà, 1989). They are distributed throughout the body, except for two regions that cannot support regeneration of an entire animal when isolated—the region in front of the photoreceptors and the centrally located pharynx (Morgan, 1898; Reddien and Sánchez Alvarado, 2004). Within 2-3 days following amputation of a planarian, an unpigmented structure called a blastema is formed at the wound site and gives rise to some of the new body parts (Reddien and Sánchez Alvarado, 2004). Various studies indicate that neoblasts proliferate following wounding and are the source of new cells for blastema formation (Baguñà, 1976b; Best et al., 1968; Coward et al., 1970; Lindh, 1957; Saló and Baguñà, 1984). However, there has been a history of contradictory results with respect to the spatio-temporal pattern of proliferation. This may in part be due to examination of different species in these studies and the limitations of previously available histological techniques for examination of neoblasts. Two studies, using Schmidtea mediterranea (Baguñà, 1976b) and Dugesia tigrina (Baguñà, 1976b; Saló and Baguñà, 1984), described an initial maximum in mitotic numbers within 4-12 hours following amputation followed by a second maximum in mitotic numbers occurring more strongly near the wounds by approximately 2-4 days.

Using newly available markers for neoblasts and neoblast mitoses, we provide evidence for the existence of distinct signaling events that control these two mitotic peaks of the neoblast wound response in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Our data indicate that the first mitotic peak is a systemic response to all types of wounding and that the second mitotic peak is a local response only generated following injuries that result in missing tissue. These findings establish for the first time two distinct stem cell responses in situations of simple injury versus situations where tissue must be regenerated. Additionally, this work divides the planarian wound response into two temporally and functionally distinct phases that provide a framework for future molecular studies of stem cell behavior in regeneration in an in vivo setting.

Materials and methods

Planaria culture

Schmidtea mediterranea asexual strain CIW4 was maintained as described (Wang et al., 2007) and starved for 1 week before experiments. 4-8mm-long animals were used for immunolabelings and cell-counting experiments; 1-2 mm-long animals were used for in situ hybridizations.

Gene cloning

For riboprobes, genes were cloned into pGEM and amplified using T7-promoter-containing primers. For RNAi, genes were cloned into pPR244 as described (Reddien et al., 2005a).

In situ hybridizations

in situ hybridizations on cells were performed as described (Reddien et al., 2005b). For maceration, CMFB contained 1 mg/ml collagenase; fragments rocked 10 minutes at RT. Further dissociation used a syringe; cells were filtered (40μm), centrifuged (70g, 5 minutes), resuspended in CMF, and fixed with 4% PFA. Fluorescence in situ hybridizations were performed as described (Pearson et al., 2009). For double/triple labeling, HRP-inactivation was performed between labelings in 4% formaldehyde, 30min.

Immunostaining

Animals were killed in 10% NAC in PBS and labeled with anti-H3P (1:100, Millipore, USA), anti-NST (1:2000), or anti-SMEDWI-1 (1:2000) as described (Newmark and Sánchez Alvarado, 2000). Anti-SMEDWI-1 antibody was generated in rabbits using the peptide previously described (Guo et al., 2006). Anti-NST antibody was generated in rabbits by injection of full-length planarian NST.

Imaging and analyses

Mitotic density was determined by counting nuclei labeled with the anti-H3P antibody, and normalized by the quantified animal area (unless otherwise stated) using the Automatic Measurement program of the AxioVision software (Zeiss, Germany). For quantification of NB.21.11E-expressing cells, the complete dorsal domain of cells (about twenty 1μm z-stacks) was photographed from the head and tail regions (335μm from the head or tail tip along the head-to-tail axis were imaged, or ~0.1mm2 of tissue per animal). Numbers were determined using the Automatic Measurement program of the AxioVision software (Zeiss, Germany). For cell in situ hybridization quantifications, animals were dissociated and labeled as described above, and the percentage of cells with signal (medium and high expression levels, assigned visually) of the total DAPI+ cell number was calculated.

Results

Neoblasts respond to wounding in a widespread first mitotic peak and a second localized mitotic peak

Amputation and feeding result in an increase in neoblast proliferation that can last up to seven days (Baguñà, 1976a; Baguñà, 1976b). To investigate neoblast mitoses following wounding, we used an antibody that recognizes Histone H3 phosphorylated at serine 10 (anti-H3P). This mark is present from the onset of mitosis to telophase (Hendzel et al., 1997). Because neoblasts are the only actively dividing somatic cells, and whole-mount antibody labeling can be performed in planaria, this antibody allows quantification and spatial resolution of neoblast mitoses in entire animal fragments (Newmark and Sánchez Alvarado, 2000).

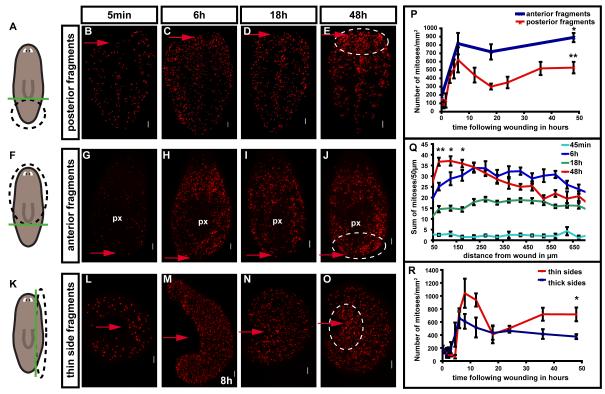

We established an assay and key time points for examining mitotic patterns in animal posterior (tail) fragments (Figs. 1A-E, Figs. S1A-D). A temporally biphasic mitotic pattern occurred following amputation (Figs. 1A-E, P, Figs. S1A-F), similar to that observed previously by counting mitotic figures in successive tissue strips (Saló and Baguñà, 1984). After a slight decrease in mitotic density at around 45 minutes (min) – 1 hour (h) (Figs. 1P, S1A), a rapid, 5-fold increase in mitotic numbers occurred, resulting in a first mitotic peak within 6h (Figs. 1C, P). Significantly, this peak occurred throughout the entire animal fragment, rather than only in cells near the wound. This first peak was followed by a general decrease in mitotic numbers, reaching a minimum by 18h following amputation (Figs. 1D, P). At this point, mitoses were still 2-fold higher in number than in uninjured animals (Fig. 1P). Additional wounding applied to tail fragments 6h before the mitotic minimum was not sufficient to increase mitotic numbers; by contrast, a stimulus applied during the mitotic minimum, or later, was sufficient to boost mitotic numbers (Fig. S2). This observation indicates that the drop in mitotic numbers at 18h is likely not caused by a cessation in wound signaling.

Fig. 1. Neoblasts respond to amputation with a widespread first mitotic peak and a second, localized mitotic peak.

(A-R) Wounding triggers a widespread first mitotic peak, by 4-10 hours, and a localized, second mitotic peak by 48h. A), F), K) schematics, amputation procedure. Green line, amputation plane. Black dotted circle, region analyzed. Amputated fragments were labeled with an anti-H3P antibody to detect mitoses at indicated timepoints. (P) Change in mitotic density with time following amputation in transversely amputated fragments. Mitotic numbers were significantly higher at 48h versus 18h; **p<0.01, *p<0.05, Student’s t-test. (Q) Mitotic numbers at different distances from the wound site in posterior fragments. Numbers were significantly higher at the wound site at 48h versus 6h; **p<0.01, *p<0.05, Student’s t-test. (R) Change in mitotic density with time following parasagittal amputation. Mitotic numbers were significantly higher at 48h versus 18h; *p<0.05 by Student’s t-test. Red arrows, amputation site. White arrows, pharynx. Circles, wound site at 48h showing increased mitoses. n ≥ 3. Anterior to the top in all images, dorsal view. Scale bars 100μm. All data represent averages ± standard deviation (sd).

A second change in neoblast division occurred involving an increase in mitotic numbers near the wound that peaked approximately 48h – 72h following wounding (Figs. 1E, P, Figs. S1B-C). This second mitotic peak thus differs from the first peak in that the increase in mitotic numbers is local as opposed to widespread (Figs. 1E, Q). Mitotic numbers stayed elevated for the following 8 days, but became more evenly distributed throughout the fragment (Figs. S1B, D-F). Between five and six days following amputation, mitoses were lacking where the newly forming pharynx became visible (Figs. S1E-F). In contradiction to previous reports (Saló and Baguñà, 1984), we did observe mitoses occasionally in blastemas, particularly in posterior-facing blastemas (Figs. S1G-J).

To determine whether the biphasic mitotic pattern described above is a general feature of planarian regeneration, a time course of transverse and parasagittal amputations was performed to obtain fragments with posterior (Figs. 1F-J) and lateral-facing wounds (Figs. K-O). In all cases, a biphasic mitotic pattern was observed, with some differences in the details of the pattern (Figs. 1P, R). Thin, regenerating side fragments, for instance, had a longer period of decrease in mitotic numbers before the first peak (Fig. S1A) and a later first peak (8h) than did posterior fragments (Figs. 1M, R, S1A). The overall magnitude of mitotic numbers at the time of the second, localized mitotic peak varied greatly between the different fragment types. However, a local increase at the wound site was always observed (Figs. 1E, J, O, Q) (hereafter referred to as the second peak). These key aspects of the neoblast wound response – a biphasic pattern mitotic pattern consisting of a first, immediate, and widespread mitotic peak and a second, localized mitotic peak – are explored below.

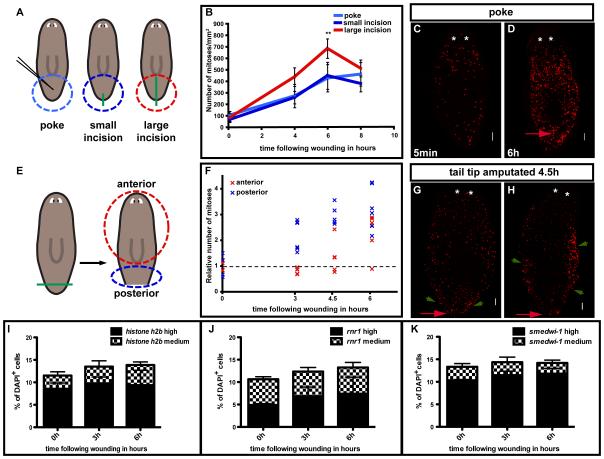

The magnitude of the first mitotic peak depends on wound size

What aspects of injury result in the rapid and widespread increase in mitoses during the first mitotic peak? To test the influence of wound size, three different surgeries were performed (Fig. 2A) and numbers of mitoses were analyzed at 4, 6, and 8h. Strikingly, all wound types tested caused a robust and widespread mitotic increase, even minor injuries that did not elicit or require overt blastema formation. The first wound type (a simple poke in the animal tail using a 10-20μm diameter needle ) and the second wound type (a small incision with a blade in the tail tip) caused a more than 4-fold increase in mitotic numbers in the postpharyngeal region (Fig. 2B). Because a simple piercing of the animal can trigger a mitotic response throughout the planarian body (Figs. 2C, D), we suggest that the initial response of neoblasts to wounds is triggered by disruption of animal integrity. Furthermore, prior data suggested interaction of dorsal and ventral epidermis during wound closure might be inductive for regeneration (Kato et al., 2001; Ogawa et al., 2002). However, because a needle-poke of the dorsal epidermis induced a robust mitotic response, we conclude that dorsal/ventral epidermis interaction is not required for a neoblast wound response.

Fig. 2. The first mitotic peak and the response of neoblasts to wounds.

(A-D) The first mitotic peak magnitude depends on wound size. A) Green lines, wound. Light blue, blue, and red circles, area analyzed. (B) Change in mitotic density with time following wounding. (C-D) A small injury (needle-poke) induces a widespread first mitotic peak by 6h; n ≥ 5. (E-H) The signal that causes the first peak spreads from the wound site. (E) Tail tips were amputated; blue and red circles, area analyzed at right. (F) Change of mitoses in areas far from the wound (anterior) and close to the wound (posterior) following wounding. The number of mitoses for each data point was divided by the average number of mitoses determined for each body region present immediately after amputation (5 min). (G-H) Animals from E) labeled with anti-H3P at 4.5h. Images, stages (G) with mitotic numbers elevated near but not far from the wound (2/8 animals), and (H) with mitotic numbers elevation having spread along the animal periphery (5/8 animals); n ≥ 6. (I-K) The signal that causes the first mitotic peak likely acts on G2/M transition. Graphs, quantification of in situ hybridizations on fixed cells from animals macerated at indicated timepoints, probing for (I) histone H2B (DN290330), (J) rnr1 (DN309701), and (K) smedwi-1 (DQ186985) mRNA. The number of S phase-marker-positive cells did not robustly change before the first mitotic peak; n=5, triplicate. Red arrows, wound sites. Anterior to the top, dorsal view. Asterisks, photoreceptors. Scale bars, 100μm in all images. Data represent averages ± sd.

A large incision, from the tail tip to the pharynx, resulted in a significantly higher increase in mitotic numbers at 6h following wounding than did the two smaller wounds (Fig. 2B). Therefore, the magnitude of the first mitotic peak scales with wound size. Because planarians can readily seal these injuries along the incision plane, this injury also did not require overt blastema formation for repair. Importantly, none of these surgeries (poke or incision without amputation) resulted in a robust, localized second mitotic peak (this observation is explored further below). Together, these observations indicate that the signal that causes the first mitotic peak is wound size-dependent, with a fast and broad-acting mechanism, and is triggered by any injury – even those not requiring blastema formation for repair – that pierces the epidermis.

The signal that causes the first mitotic peak spreads from the wound site

If there exists a signal that emanates from the wound that is responsible for the first mitotic peak, it should be possible to observe intermediate stages of increase in mitoses as a function of distance from the wound. By 3-4.5h following amputation at the tip of the tail, a wave-like increase in mitoses starting from the wound site was in fact observed (Figs. 2E-F). At the 3 and 4.5h time points, fragments were found to be in various stages of mitotic elevation (Figs. 2G-H). By 6h, all but one fragment showed similar mitotic increase in the anterior and the posterior (Fig. 2F). The mitotic increase was found to spread from near the wound site along the periphery of the animal, before spreading towards the fragment middle (Fig. 2H). These observations indicate the candidate existence of a diffusion/spreading mechanism that triggers the first mitotic peak.

The signal that causes the first mitotic peak acts mainly on the G2/M transition

The simplest explanation for the rapid increase in mitotic numbers during the first mitotic peak would be action of the inducing signal on G2/M progression, resulting in shortening of G2. Because BrdU can only be applied by injection or feeding (Newmark and Sánchez Alvarado, 2000), which both induce an increase in neoblast proliferation, BrdU-labeling and fraction of labeled mitoses (FLM) experiments cannot easily identify the kinetic changes in cell cycle phases that occur following injury. However, prior FLM experiments indicate that the median length of G2, under conditions of stimulation, is 6h (Newmark and Sánchez Alvarado, 2000). Furthermore, experiments with S-phase inhibitors suggested that roughly half of the mitoses induced by wounding could occur if S phase was blocked (Saló and Baguñà, 1984). Though not conclusive, these observations are consistent with the idea that acceleration of S-phase does not alone explain the first mitotic peak. In general these observations suggest that approximately half of the mitoses observed at the first peak come from cells that were in S-phase at the time of injury and half come from cells that were in G2. We further reasoned that if the signal that causes the rapid mitotic increase simply accelerates G2, no apparent change in numbers of S-phase cells should be visible. By contrast, if the first peak is explained entirely by a change in the rate of S-phase entry or progression, a robust change in the number of S-phase cells during production of the first mitotic peak should occur. Animals were amputated post-pharyngeally and left to respond to the injury for 0, 3, and 6h. Subsequently, tails were macerated and in situ hybridizations were performed on resultant separated and fixed cells. We probed for expression of the planarian homologs of the S-phase-specific transcripts histone H2B (Hewitson et al., 2006) and rnr1 (Bjorklund et al., 1990; Eriksson et al., 1984), as well as smedwi-1 as a control. The smedwi-1 gene encodes a planarian homolog of PIWI proteins and is expressed in more than 90% of actively cycling neoblasts (Reddien et al., 2005b). Therefore, it should be expressed in most, if not all cell cycle stages. No significant increase or decrease in the number of cells positive for the S-phase markers or smedwi-1 was observed (Figs. 2I-K). Whereas it is possible that changes in multiple phases of the neoblast cell cycle occur, these data support the idea that the wound-specific signal that induces the first mitotic peak causes an acceleration of G2 rather than S-phase.

The localized increase in mitoses at the wound site during the second peak is specific to loss of tissue

Mitoses localize to the wound site by two days following amputation. However, as described above, fragments that were only incised showed no robust second mitotic peak. We also examined animals that were amputated postpharyngeally, and, in addition, had a thin epidermal strip cut off the side of the resulting tail fragments (Fig. S3A). These fragments possessed a wound surface twice as large as the wounds from simple tail amputation; however, both fragment types were missing approximately the same amount of tissue (the entire midbody and head) and had a similar second mitotic peak (Fig. S3A). These observations raise the question of what factor(s), if not simply wounding or wound size, trigger the second neoblast-response phase that culminates in the second peak.

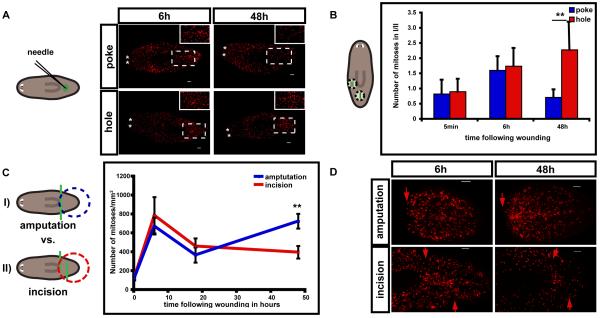

We considered the possibility that it is the absence of tissue that is the key determinant in generation of the localized second peak. We compared the wound response of animals injured with a needle poke (diameter 10-20μm) and with a small hole-punch (diameter >50μm); the hole-punch removes tissue, whereas the needle-poke does so only minimally. Significantly, only animals that regenerated from a hole-punch showed a local increase in proliferation at the wound site during the second mitotic peak (Figs. 3A, B). Areas further away from the wounds had an equal mitotic density for both surgery types (Figs. 3A, B), and overall mitoses were higher in both surgeries (Fig. S3B). Because the wounds caused by hole-punch close without dorsal-ventral epidermis juxtaposition, the second, localized mitotic peak does not require DV confrontation. These data are consistent with the idea that it is the absence of tissue that triggers the second, localized mitotic peak.

Fig. 3. The localized, second mitotic peak is specific to loss of tissue.

(A-B) A needle-poke and a hole-punch both induced a strong first peak, but only a hole-punch induced a second, localized peak. Animals were labeled with anti-H3P at indicated timepoints. At left, cartoon schematic depicts the surgical strategy with representative images shown in (A) and quantification shown in (B). Green circles, wound site. A needle was used to inflict piercing of the epidermis (poke, diameter 10-20μm), whereas a broken needle was used to inflict hole-punches (hole, diameter >50μm) that removed a cylindrical region of tissue. Black circles, analyzed areas. (A) Insets, wound-site magnification. (B) At left, cartoon depicts the regions quantified following infliction of poke or hole wounds. Mitotic numbers were determined for two different 267 μm diameter, cylindrical tissue regions (dotted circles): I) centered at the wound site and II) at a region distal from the wound. n ≥ 5. **p<0.01 by Student’s t-test.(C-D) Amputations, I), were accomplished by surgical removal of the anterior two-thirds of the body (green line). Incisions, II), were made through the entirety of the body at indicated locations (green lines) and allowed to re-seal. Amputation, I), triggered a localized second mitotic peak, but incisions, II), which caused a larger wound size than in I) but no significant loss of tissue, did not. Blue and red circles, area analyzed. (C) Mitotic density with time following amputation. n ≥ 4. **p<0.01 by Student’s t-test. (D) Representative images of animals analyzed in (C). Red arrows, wound site. Bars, 100μm. Data represent averages ± sd.

To exclude the possibility that the difference in wound size between the needle-poke and the hole-punch caused the differences in localization of mitoses, we designed a surgery strategy to result in two fragment types; the first I) involved tissue removal and the second II) involved a wound of larger size than I) but with essentially no missing tissue (Fig. 3C). For both surgeries, mitoses were strongly increased in the analyzed fragments during the first peak. However, only the surgery that resulted in tissue loss (type I, missing the midbody and head) produced a robust second mitotic peak (Fig. 3C). Importantly, no localization of mitoses was visible at the wound site in fragments that were only incised (type II) (Fig. 3D). Because mitotic numbers are still elevated at 18h and 48h in these animals as compared to intact animals, possibly due to continued proliferative effects from the first peak, the most prominent difference observed was a local increase in mitoses at the wound site. These observations, together with the data described above, suggests that it is tissue loss, rather than simple injury itself, that induces the localized, second mitotic peak.

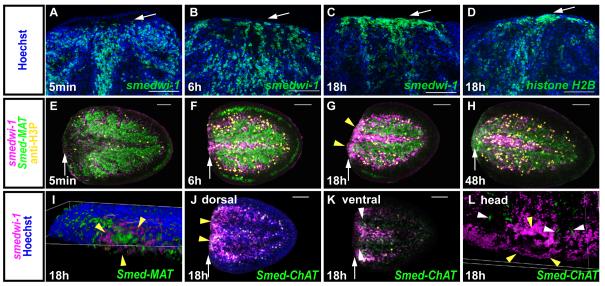

Neoblasts accumulate at the wound site during the mitotic minimum

What changes occur within the neoblast population in the transition from the initial wound response to the second mitotic peak? We determined that, during this phase of decline in mitotic numbers (by 18h), the neoblasts accumulate at injury sites. We performed fluorescent in situ hybridizations with regenerating fragments 5min, 6h, and 18h after amputation using a riboprobe for the neoblast marker, smedwi-1. smedwi-1+ cells accumulated near the wound site by 18h (Figs. 4A-C). A similar observation was made for cells expressing either histone H2B, expressed in S-phase (Hewitson et al., 2006), (Fig. 4D) or cyclin B, expressed in a subset of cycling cells (Lee et al., 1988; Richardson et al., 1992), (Fig. S4). Of note, at 18h following amputation, the majority of smedwi-1+ cells accumulated dorsally at the wound site; neoblast proliferation was previously suggested to occur along the planarian nerve cords (Brøndsted, 1969), which are located ventrally. However, most smedwi-1+ cells at the wound site were found in close vicinity to the remnant intestine branches (Figs. 4E-H, J), rather than the ventral nerve cords (Figs. 4I-L). In general, the observed neoblast accumulation at wounds raises the possibility that regeneration initiation may involve signaling from injuries that trigger neoblast migration.

Fig. 4. Cycling cells are recruited to the wound site and proliferate predominantly near intestinal branches.

(A-D) Cycling cells accumulate at the wound site at 18h following wounding. Wound sites in tail fragments are shown. (A-C) smedwi-1+ and D) histone H2B+ cells accumulate at the wound site at 18h (green). Nuclei were labeled with Hoechst (blue). Anterior, to the top. (E-L) Cycling cells accumulate at the tip of gut branches at 18h (yellow arrows), but not at the nerve cords. Tail fragments were labeled with smedwi-1 (magenta) and anti-H3P (yellow), together with Smed-MAT (EG413862, Methionine adenosyltransferase, expressed in the planarian intestine) or Smed-ChAT (Choline acetyltransferase, expressed in planarian nerve cords) (green) at indicated timepoints. Anterior, left, except in I) and L). (I) 3D projection showing a gut branch opening (green) surrounded by smedwi-1+ cells (magenta); anterior-dorsal view. (J) Optical section from dorsal domain of a posterior (tail) fragment. Gut branch outlines can be seen by Hoechst labeling; in this dorsal domain, no ChAT expression is found. (K) Optical section from ventral domain of the same tail fragment as J). No accumulation of smedwi-1+ cells in areas of ChAT expression. (L) 3D projection from an anterior (head) fragment showing that the majority of smedwi-1+ cells accumulates around the single gut branch, but not the nerve cords - ChAT + cells (in green, white arrow heads), posterior-ventral view. Images represent superimposed optical sections, except in (J-K). Dorsal view, unless otherwise stated. White arrows, wound site. Yellow arrowheads, smedwi-1+ cells surrounding gut branches. Bars, 100μm.

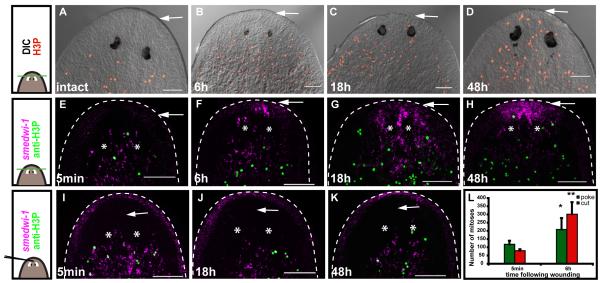

Loss of tissue induces neoblast migration to wound sites

To test the hypothesis that neoblasts are recruited to wounds we amputated animals anterior to the photoreceptors, a region devoid of neoblasts (Newmark and Sánchez Alvarado, 2000). Following amputation, smedwi-1+ and H3P+ cells were visible in front of the photoreceptors at 18h and 48h following wounding, respectively (Figs. 5A-H). Accumulation of smedwi-1+ cells at 12h and rare cells at 6h was even observed (Figs. 5F, S5). We conclude that active recruitment of neoblasts to the site of wounding can occur before or during the minimum in mitoses (by 18h).

Fig. 5. Loss of tissue induces neoblast recruitment to wounds.

(A-K) Cartoons at left depict surgery types. Top and middle, amputation of the head tip (green line); bottom, black line indicates site of needle poke. White arrows on images indicate the sites of amputation or needle poke in head tips. White asterisks indicate photoreceptors. Anterior, up. Bars, 100μm. (A-D) Mitotic cells appear in front of the photoreceptors at (C) 18h and (D) 48h after amputation. Differential interference contrast (DIC) image superimposed with image of mitotic cells (anti-H3P, red). (E-K) smedwi-1+ cells (magenta – fluorescence at animal periphery is non-specific) and mitoses (green) accumulate in head tips (a region normally devoid of neoblasts) at 18h and 48h, respectively, when the head tip was amputated (E-H), but not following a needle-poke (I-K). (L) A head tip needle-poke induces a first mitotic peak. Data represent averages (n ≥ 3) ± sd. Mitoses were quantified from z-stacks through the entirety of the DV axis from tip of the head to the posterior base of the pharynx. Data were significantly higher at 6h than at 5min; **p<0.01 and *p<0.05 by Student’s t-test.

This experiment involved amputation in a region where neoblasts do not reside, leaving open the possibility that neoblast recruitment only occurs in cases when no neoblasts are initially present at the wound site. However, as described above, the number of cycling cells increases by 18h at transverse amputation sites (e.g., in tail fragments)—that possess many neoblasts (Figs. 4C, D, Fig. S4). Mitoses are evenly distributed in the body before 18h following such transverse amputations (Figs. 1D, I, N); we therefore conclude that the accumulation of neoblasts cannot be explained by local proliferation. In addition, irradiation experiments indicate that neoblasts cannot be produced by differentiated tissues (Wolff and Dubois, 1948), excluding the alternative explanation that de-differentiation occurs at the wound site and explains the greater number of neoblasts observed.

Significantly, a poke into the head tip with an injection needle did not cause detectable recruitment of smedwi-1+ cells or H3P+ cells (Figs. 5I-K), despite inducing a first mitotic peak at 6h (Fig. 5L). Therefore, we conclude that the increase of neoblasts at wounds is the result of neoblast migration and is induced by tissue absence rather than by injury per se.

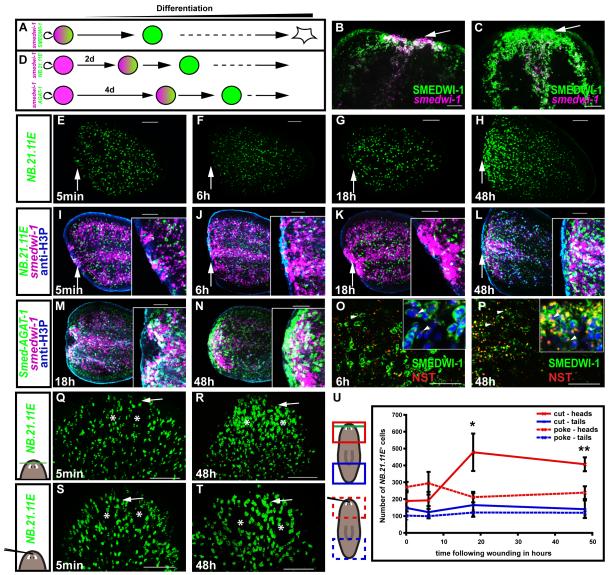

The second mitotic peak is accompanied by neoblast differentiation

In order for tissue replacement to occur, neoblasts must produce differentiated cells. Does this occur in response to injuries during a phase of regeneration initiation, or after initial blastema formation? To distinguish cycling neoblasts from those that have exited the cell cycle and will differentiate, we double-labeled animals with a riboprobe to detect smedwi-1 mRNA and an antibody to recognize SMEDWI-1 protein (Guo et al., 2006). Cycling cells are smedwi-1+/SMEDWI-1+, whereas cells that cease expression of smedwi-1 and exit the cell cycle will transiently be smedwi-1−/SMEDWI-1+ due to protein perdurance (Fig. 6A). Support for this assertion can be observed by the spatial relationship between these two cell types in intact animals; smedwi-1−/SMEDWI-1+ cells are present anterior to the photoreceptors, a region devoid of cycling neoblasts (Guo et al., 2006; Newmark and Sánchez Alvarado, 2000). Furthermore, SMEDWI-1+ cells are eliminated shortly after irradiation (Guo et al., 2006) and can be labeled by a BrdU-pulse chase; indicating that the entire SMEDWI-1+ cell population is comprised of neoblasts and their non-dividing descendants. By 18h after amputation, there existed a high density of smedwi-1+/SMEDWI-1+ cells at the wound site, many of which expressed smedwi-1 mRNA strongly (Fig. 6B). By 48h after amputation, however, a layer of mostly smedwi-1−/SMEDWI-1+ cells was found in front of the zone of actively cycling cells (smedwi-1+/SMEDWI-1+) (Fig. 6C). These data indicate that before and during the second mitotic peak a proportion of neoblast descendant cells exit the cell cycle and give rise to a layer of non-cycling cells at the wound site. This indicates that signals from wounds trigger increased differentiation at the wound site very early in regeneration—before and during the second mitotic peak.

Fig. 6. The second mitotic peak is accompanied by differentiation and cell growth at the wound site.

(A) Lineage relationship schematic. smedwi-1+(mRNA, magenta)/SMEDWI-1+(protein, green) neoblasts will become SMEDWI-1+ cells as they differentiate. (B-C) Tail fragments probed with anti-SMEDWI-1 antibody (green) and smedwi-1 riboprobe (magenta). White arrow, wound site. Anterior, up. (B) smedwi-1+/SMEDWI-1+ cells accumulate at the wound site of tail fragments at 18h. White arrow, wound site. Anterior, left. (C) A layer of smedwi-1−/SMEDWI-1+ cells formed in front of actively proliferating smedwi-1+/SMEDWI-1+ cells at 48h, indicating increased differentiation. (D) smedwi-1+ neoblasts (magenta) will turn on the NB.21.11E and Smed-AGAT-1 genes (green) as they differentiate. (E-L) Timecourse, following amputation, of tail fragments (E-H) labeled with an NB.21.11E riboprobe (green); (I-L) merge of (E-H) labeling with anti-H3P antibody for mitoses (blue epidermal fluorescence is non-specific), and with a smedwi-1 riboprobe (magenta). Insets, magnified view of wound site. White arrow, wound site. Anterior, left. (M-N) Timecourse, following amputation, of tail fragments. Smed-AGAT-1+ (EC616230) cells (green) accumulate at the wound site in front of smedwi-1+ cells (magenta) at 48h (mitoses in blue, anti-H3P), indicating increased differentiation. Anterior, left. (O-P) Neoblast descendants at the wound site show an increase in nucleolar size at 48h. Tail fragments labeled with anti-SMEDWI-1 (green) and anti-NST (red) antibodies. NST signal was also found in SMEDWI-1+ cells, white arrowheads. (O) At 6h, NST was localized to a small nuclear region, inset (Hoechst, blue). (P) At 48h, NST signal occupies up to 1/3 of the nucleus. SMEDWI-1 and NST are in the cytoplasm and nucleus, respectively. However, both antibodies are from rabbits, leading to some artificial double labeling where there was high signal intensity (e.g., at 48h, nucleolar SMEDWI-1 signal is an artifact). (Q-S) Increased neoblast descendant formation at wounds is specific to tissue loss. NB.21.11E+cells (green) increased at the wound site (white arrow) between 18h and 48h following head tip amputation (Q-R), but not following a poke in the head tip (S-T). (U) Number of NB.21.11E+ cells in the wound area shown in images (Q-T). Data represent averages; n ≥ 3 ± sd. Green line, amputation plane. Red and blue regions, analyzed areas. (B, C, E-T) Images represent superimposed optical sections, dorsal view, unless otherwise stated. Scale bars, 100μm.

Three different categories of genes that are expressed in cells that disappear following irradiation were recently identified. These genes are expressed in neoblasts (e.g., smedwi-1) and the non-dividing descendant cells of neoblasts (e.g., NB.21.11E and Smed-AGAT-1) (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008), allowing assessment of neoblast differentiation (Fig. 6D). It was previously shown that neoblast descendants accumulate at the wound site at 4d following amputation (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008). A thin strip of unpigmented tissue is already visible at the amputation site by 48h, however. To assess differentiation and blastema formation, we assessed the distribution of NB.21.11E+ and Smed-AGAT-1+ cells in tail fragments (Figs. 6D, E-N). By 48h after amputation, NB.21.11E+ or Smed-AGAT-1+ cells were found in front of (proximal to the wound epidermis) the smedwi-1+ and H3P+ cells (Figs. 6L, N). By contrast, NB.21.11E+ and Smed-AGAT-1+ cells were behind smedwi-1+ and H3P+ cells (distal, with respect to the wound epidermis) at 6 and 18h after amputation (Figs. 6J-K, M). These observations indicate that, first, stem cells are recruited to wounds and second, increased neoblast differentiation occurs at the wound site during the time of the second mitotic peak to initiate blastema formation.

Cells with a high demand for ribosomal biosynthesis, such as highly proliferating or growing cells, typically show an increase in nucleolar size (Frank and Roth, 1998). We raised an antibody against SMED-NUCLEOSTEMIN (NST), the planarian homolog of mammalian nucleostemin, a nucleolar GTPase that is expressed in proliferating cells/stem cells (Kudron and Reinke, 2008; Tsai and McKay, 2002; Tsai and McKay, 2005). Therefore, NST should serve as a marker of the planarian nucleolus, and was in fact localized to a compartment of the nucleus (Figs. S6A-B). Within 11 days following nucleostemin RNAi, the protein was mostly depleted (Figs. S6C-D), indicating antibody specificity. Following wounding, SMEDWI-1+ cells at the wound site exhibited a strongly broadened NST signal at 48h compared to 6h-wounded animals (Figs. 6O-P). This suggests nucleolus broadening and probable increase in ribosome biosynthesis. Most of these SMEDWI-1+ cells have likely exited the cell cycle, as shown by their lack of smedwi-1 mRNA expression (Fig. 6C). It is therefore probable that these non-dividing neoblast progeny cells are growing and differentiating (Johnson et al., 1974). The increase in progeny cells and in cells with a broadened NST signal indicates commitment to differentiate at wounds is an early response in regeneration initiation.

We described above that local proliferation at the second peak and neoblast recruitment to wounds are outcomes specific to injuries that remove tissue. To test whether increased formation of non-dividing neoblast descendants is also specific to tissue loss, we utilized different injuries in animal head tips. In fragments where the tip of the head had been amputated, NB.21.11E+ cells increased in number at the wound site, but not far away from the wound, at 18h and 48h (Figs. 6Q-R, U). By contrast, we did not observe accumulation of NB.21.11E+ cells at 18h or 48h in animals that were poked in the tip of the head with a needle (Figs. 6S-U). This observation suggests that it is loss of tissue, rather than simply wounding, that triggers neoblast differentiation at wound sites. Together, our experiments indicate that – in addition to wound detection – tissue absence is detected early in regeneration and that signals from wounds that result in loss of tissue lead to neoblast recruitment, local neoblast division, and neoblast descendant formation at the wound site – coordinately leading to blastema formation. These data are significant in that they indicate a key event in regeneration is the detection of tissue absence and the associated signaling from wounds.

Discussion

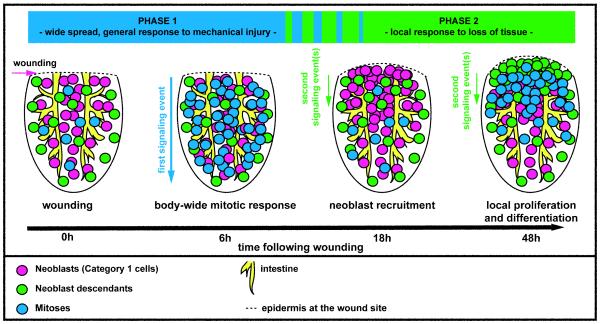

Planarian regeneration provides a powerful system for studying the regenerative response of adult stem cells following different types of injuries. Utilizing histological and molecular tools that have only recently become available, we characterized changes in planarian neoblasts that occur following wounding. Two distinct mitotic peaks were apparent early in the process of planarian regeneration, consistent with studies performed previously in Schmidtea mediterranea and Dugesia tigrina (Baguñà, 1976b; Saló and Baguñà, 1984). We provide evidence that the two described mitotic peaks have distinct properties indicative of two phases of regeneration initiation, with independent underlying signaling events. Together, our data suggest a model for planarian regeneration initiation (Fig. 7) that involves two phases of wound responses. First, wounds trigger entry into mitosis at long distances (body wide); induction of cell cycle changes distant from the site of injury is a novel property of wound-induced signaling. Second, tissue absence is detected, which triggers recruitment of neoblasts to wounds. Neoblasts are then signaled to divide near the wound and they commit to production of cells at the wound that will exit the cell cycle and differentiate (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Model of the planarian neoblast wound response.

Cartoon summarizing cellular changes during regeneration initiation. Two distinct phases of neoblast responses occur during regeneration initiation. The first phase represents a generic response to injury that spreads quickly from the wound site, is wound-size dependent, and induces increased mitotic entry of neoblasts body-wide. The second phase occurs only when a significant amount of tissue is missing and involves local signals that induce recruitment of neoblasts followed by local proliferation and differentiation at the wound site. Depicted are posterior (tail) fragments.

The response to wounds and the first mitotic peak

We found an immediate and broad increase in mitoses that peaks between 4-10 hours following wounding. An immediate increase in mitotic numbers had been observed before in S. mediterranea (Baguñà, 1976b) and Dugesia tigrina (Saló and Baguñà, 1984). Surprisingly, a simple poke with a needle sufficed to trigger this body-wide, mitotic response. Our data provide evidence for a broad and fast-acting signal, that scales with wound-size, and that spreads quickly from wounds.

We did not detect robust changes in the numbers of S-phase cells in the first 6h after injury, suggesting that the wound signal acts primarily on G2/M progression of the cell cycle to shorten G2. However, because the number of mitotic cells is very small in comparison to the number of cells in S phase, it is still possible that a minor, undetected change in the S phase cell numbers would be sufficient to cause a 4-10 fold increase in mitotic numbers. Considering data from previous studies (Newmark and Sánchez Alvarado, 2000; Saló and Baguñà, 1984), it seems likely that cells that were both in G2 and S-phase at the time of injury contribute to the first mitotic peak with the increase in mitotic numbers caused by acceleration of G2.

In hydra, it has been shown that 4 hours following head, but not foot amputation, an immediate apoptosis-induced increase of proliferation occurs (Chera et al., 2009). In planarians it has been shown that a simple incision is sufficient to induce a localized increase in apoptosis at the wound site by 4 hours (Pellettieri et al., 2009). Whether this localized cell death is involved in the induction of the broad, first mitotic peak remains to be determined; however, the spatial distributions of mitoses and apoptotic cells following injury differ. Rapid, organ-wide, wound-induced gene expression changes have been described recently in zebrafish heart regeneration (Lepilina et al., 2006). The possibility thus exists that early broad-acting wound signals will be found in many regenerating organisms. The identity of regeneration signals that are induced by wounds and exert influence at long distances is unknown.

The response to missing tissue and the second mitotic peak

Our experiments show that loss of tissue is the key event for recruitment of neoblasts to wounds and their subsequent local proliferation and differentiation during the second mitotic peak. To our knowledge, no prior paradigm has indicated any mechanism by which tissue absence – rather than simply injury – is detected and causes a response in stem cells. Therefore, the molecular mechanisms by which regenerating organisms detect tissue absence will be of great interest for understanding regeneration.

We found that neoblasts are recruited to wound sites involving missing tissue. This indicates the existence of a candidate stem cell migratory signal that is induced following the detection of tissue absence. There exist previous conflicting reports on neoblast migration in regeneration. In one study, animals with one half of their body irradiated displayed degeneration in the irradiated region unless they were amputated—supporting the idea that amputation induced neoblast recruitment (Wolff and Dubois, 1948). Subsequent studies using tissue grafts and chromosomal and nuclear markers to track neoblasts led to the proposal that neoblast movement is explained through passive spreading by cell division (Saló and Baguñà, 1985; Saló and Baguñà, 1989). Our data use molecular markers of neoblasts and demonstrate the capacity of neoblasts to migrate to wounds in animal head tips—a region normally devoid of neoblasts.

The cells that accumulate at wounds are cycling, but not initially mitotic. Therefore, whereas the initial wound response (the first peak) involves a mitotic response, the missing-tissue response involves migration of cells that proceed through S phase and result in a later, local mitotic peak (the second peak). The observed increase in NUCLEOSTEMIN signal (nucleolar marker) within neoblast progeny cells at wounds suggests these cells have an increased growth rate. Nucleolar size also increases at the wound site in the regenerating organism Lumbriculus (Sayles, 1927). At 48h post amputation, we also found an accumulation of neoblast progeny expressing differentiation markers. Because we did not observe a notable decrease in neoblast descendant numbers in areas far away from wounds, this accumulation is probably not due primarily to migration of descendants, but local differentiation. Therefore, there exists a signal induced by tissue loss that induces a greater incidence of differentiation of neoblast progeny, as opposed to retention of neoblast identity, near the wound.

Local accumulation of S-phase cells at wound sites, followed by an increase in mitoses is a phenomenon observed in multiple regenerating systems. For example, S-phase cells accumulate at wounds within 12-24h following posterior amputation in the flatworm Macrostomum lignano (Egger et al., 2009), during rodent liver regeneration (Taub, 1996), during zebrafish fin regeneration (Nechiporuk and Keating, 2002), and in Drosophila wing disc regeneration (Bosch et al., 2008). In most of these cases, an increase in mitotic numbers is observed within the day following recruitment, suggesting that the recruited cells undergo mitosis. In the wing disc, genetic ablation of cells is sufficient to induce proliferation (Smith-Bolton et al., 2009). In the Drosophila midgut, stem cell proliferation can also be augmented in response to different stimuli (e.g. detergent and bacterial ingestion) (Amcheslavsky et al., 2009; Buchon et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2009); like the planarian second peak, mitoses were found to peak between one and two days following stimulus exposure. Mechanisms for detection of tissue absence may prove to be an important general feature of animal wound responses and regeneration.

It will be important in future studies to determine whether any heterogeneity of neoblasts that respond to wound signals exists and to characterize in more detail the process of blastema outgrowth. However, our data illuminate a series of events that lead to a blastema: detection of missing tissue leads to signaling that results in neoblast accumulation; some cells produced by these neoblasts will continue to divide locally and some will leave the stem-cell state near the wound epidermis to initiate blastema formation.

The neoblast wound-response assay as a paradigm to study stem cell-mediated regeneration

Generating responses to wounding is a fundamental biological process. However, study of wound responses in regeneration can be challenging because of a myriad of responses that happen in mammals or because of difficulties in gene function studies in adult organisms. We described here key steps in the response of planarian stem cells to wounds, revealing the cellular underpinnings of planarian regeneration initiation and presenting assays for genetic dissection of wound signaling. RNAi in adult planarians is robust (Newmark et al., 2003), can be performed for many genes (Reddien et al., 2005a). We established that a decrease in homeostatic neoblast numbers, following RNAi of genes that impact neoblast maintenance, is directly correlated to a decrease in the wound response (Fig. S7A) and that RNAi of S-phase entry or stress-response related genes caused a stronger effect on the second mitotic peak than the first peak (Fig. S7B). Importantly, we also found that numbers of mitoses in RNAi animals prior to amputation are not necessarily indicative of the homeostatic neoblast numbers (Fig. S7C). We suggest, therefore, that assessment of homeostatic neoblast numbers will be an essential control in experiments that examine potential regulators of neoblast proliferation following wounding and that RNAi can be used to dissect features of the wound response (Fig. S7).

Conclusion

The identification of cellular changes during regeneration initiation in planarians and the establishment of a neoblast wound-response assay provide powerful tools for the molecular dissection of stem cell-mediated regeneration using planarians as a model system. We conclude that regeneration initiation in planarians involves two distinct stem cell responses: an early systemic response to any injury and a later, local response that is uniquely caused by tissue absence, indicating that separate signaling mechanisms exist in regeneration to distinguish between simple injury and loss of tissue.

Supplementary Material

Ackowledgements

We thank the Reddien Lab for discussions and support; Dan Wagner had major impact on neoblast descendant analysis concepts and Mike Gaviño provided extensive discussion and support. We thank Sylvain Lapan and Dan Wagner for neuron and intestine markers and Irving Wang for great planaria cartoons. We thank Iain Cheeseman for generous advice and reagents for antibody production. P.W.R. is an early career scientist of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We acknowledge support by NIH R01GM080639 and ACS RSG-07-180-01-DDC; Rita Allen, Searle, Smith, and Keck Foundation support; and a Thomas D. and Virginia W. Cabot career development professorship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Amcheslavsky A, Jiang J, Ip YT. Tissue damage-induced intestinal stem cell division in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baguñà J. Mitosis in the intact and regenerating planarian Dugesia mediterranea n.sp. I. Mitotic studies during growth, feeding and starvation. J. Exp. Zool. 1976a;195:53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Baguñà J. Mitosis in the intact and regenerating planarian Dugesia mediterranea n.sp. II. Mitotic studies during regeneration, and a possible mechanism of blastema formation. J. Exp. Zool. 1976b;195:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Baguñà J, Saló E, Auladell C. Regeneration and pattern formation in planarians. III. Evidence that neoblasts are totipotent stem cells and the source of blastema cells. Development. 1989:107. [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best JB, Hand S, Rosenvold R. Mitosis in Normal and Regenerating Planarians. J. Exp. Zool. 1968;168:157–167. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401680204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund S, Skog S, Tribukait B, Thelander L. S-phase-specific expression of mammalian ribonucleotide reductase R1 and R2 subunit mRNAs. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5452–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00475a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch M, Baguna J, Serras F. Origin and proliferation of blastema cells during regeneration of Drosophila wing imaginal discs. Int J Dev Biol. 2008;52:1043–50. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082608mb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brøndsted HV. Planarian Regeneration. Pergamon Press; London: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Buchon N, Broderick NA, Chakrabarti S, Lemaitre B. Invasive and indigenous microbiota impact intestinal stem cell activity through multiple pathways in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2333–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.1827009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chera S, Ghila L, Dobretz K, Wenger Y, Bauer C, Buzgariu W, Martinou JC, Galliot B. Apoptotic cells provide an unexpected source of Wnt3 signaling to drive hydra head regeneration. Dev Cell. 2009;17:279–89. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coward SJ, Hirsh FM, Taylor JH. Thymidine kinase activity during regeneration in the planarian Dugesia dorotocephala. J Exp Zool. 1970;173:269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Egger B, Gschwentner R, Hess MW, Nimeth KT, Adamski Z, Willems M, Rieger R, Salvenmoser W. The caudal regeneration blastema is an accumulation of rapidly proliferating stem cells in the flatworm Macrostomum lignano. BMC Dev Biol. 2009;9:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhoffer GT, Kang H, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Molecular analysis of stem cells and their descendants during cell turnover and regeneration in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:327–39. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson S, Graslund A, Skog S, Thelander L, Tribukait B. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of mammalian ribonucleotide reductase. The S phase-correlated increase in subunit M2 is regulated by de novo protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:11695–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DJ, Roth MB. ncl-1 is required for the regulation of cell size and ribosomal RNA synthesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1321–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Peters AH, Newmark PA. A bruno-like Gene Is Required for Stem Cell Maintenance in Planarians. Dev Cell. 2006;11:159–69. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendzel MJ, Wei Y, Mancini MA, Van Hooser A, Ranalli T, Brinkley BR, Bazett-Jones DP, Allis CD. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates primarily within pericentromeric heterochromatin during G2 and spreads in an ordered fashion coincident with mitotic chromosome condensation. Chromosoma. 1997;106:348–60. doi: 10.1007/s004120050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson TD, Kelynack KJ, Darby IA. Histochemical localization of cell proliferation using in situ hybridization for histone mRNA. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;326:219–26. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-007-3:219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Liu Y, Yang Z, Nguyen J, Liang F, Morris RJ, Cotsarelis G. Stem cells in the hair follicle bulge contribute to wound repair but not to homeostasis of the epidermis. Nat Med. 2005;11:1351–4. doi: 10.1038/nm1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Patel PH, Kohlmaier A, Grenley MO, McEwen DG, Edgar BA. Cytokine/Jak/Stat signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell. 2009;137:1343–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LF, Abelson HT, Green H, Penman S. Changes in RNA in relation to growth of the fibroblast. I. Amounts of mRNA formation in resting and growing cells. Cell. 1974;1:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Orii H, Watanabe K, Agata K. Dorsal and ventral positional cues required for the onset of planarian regeneration may reside in differentiated cells. Dev Biol. 2001;233:109–21. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragl M, Knapp D, Nacu E, Khattak S, Maden M, Epperlein HH, Tanaka EM. Cells keep a memory of their tissue origin during axolotl limb regeneration. Nature. 2009;460:60–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudron MM, Reinke V. C. elegans nucleostemin is required for larval growth and germline stem cell division. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Norbury CJ, Spurr NK, Nurse P. Regulated expression and phosphorylation of a possible mammalian cell-cycle control protein. Nature. 1988;333:676–9. doi: 10.1038/333676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepilina A, Coon AN, Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Roberts RW, Burns CG, Poss KD. A dynamic epicardial injury response supports progenitor cell activity during zebrafish heart regeneration. Cell. 2006;127:607–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindh NO. The mitotic activity during the early regeneration in Euplanaria polychroa. Ark. Zool. 1957;10:497–509. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TH. Regeneration in Planaria maculata. Science. 1898;7:196–197. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JI, Loof S, He P, Simon A. Salamander limb regeneration involves the activation of a multipotent skeletal muscle satellite cell population. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:433–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechiporuk A, Keating MT. A proliferation gradient between proximal and msxb-expressing distal blastema directs zebrafish fin regeneration. Development. 2002;129:2607–17. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark PA, Reddien PW, Cebria F, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Ingestion of bacterially expressed double-stranded RNA inhibits gene expression in planarians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:11861–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834205100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark PA, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Bromodeoxyuridine specifically labels the regenerative stem cells of planarians. Dev Biol. 2000;220:142–53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark PA, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Not your father’s planarian: a classic model enters the era of functional genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:210–9. doi: 10.1038/nrg759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Ishihara S, Saito Y, Mineta K, Nakazawa M, Ikeo K, Gojobori T, Watanabe K, Agata K. Induction of a noggin-like gene by ectopic DV interaction during planarian regeneration. Dev Biol. 2002;250:59–70. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima H, Rochat A, Kedzia C, Kobayashi K, Barrandon Y. Morphogenesis and renewal of hair follicles from adult multipotent stem cells. Cell. 2001;104:233–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson BJ, Eisenhoffer GT, Gurley KA, Rink JC, Miller DE, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Formaldehyde-based whole-mount in situ hybridization method for planarians. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:443–50. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellettieri J, Fitzgerald P, Watanabe S, Mancuso J, Green DR, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Cell death and tissue remodeling in planarian regeneration. Dev Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW, Bermange AL, Murfitt KJ, Jennings JR, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Identification of genes needed for regeneration, stem cell function, and tissue homeostasis by systematic gene perturbation in planaria. Dev Cell. 2005a;8:635–49. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW, Oviedo NJ, Jennings JR, Jenkin JC, Alvarado A. Sánchez. SMEDWI-2 is a PIWI-like protein that regulates planarian stem cells. Science. 2005b;310:1327–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1116110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Fundamentals of planarian regeneration. Ann. Rev. Cell Dev. Bio. 2004;20:725–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.095114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson H, Lew DJ, Henze M, Sugimoto K, Reed SI. Cyclin-B homologs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae function in S phase and in G2. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2021–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saló E, Baguñà J. Regeneration and pattern formation in planarians. I. The pattern of mitosis in anterior and posterior regeneration in Dugesia (G) tigrina, and a new proposal for blastema formation. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1984;83:63–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saló E, Baguñà J. Cell movement in intact and regenerating planarians. Quantitation using chromosomal, nuclear and cytoplasmic markers. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1985;89:57–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saló E, Baguñà J. Regeneration and pattern formation in planarians II. Local origin and role of cell movements in blastema formation. Development. 1989;107:69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sayles L. Origin of the Mesoderm and Behavior of the Nucleolus in Regeneration in Lumbriculus. Biological Bulletin. 1927;52:278–312. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bolton RK, Worley MI, Kanda H, Hariharan IK. Regenerative growth in Drosophila imaginal discs is regulated by Wingless and Myc. Dev Cell. 2009;16:797–809. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub R. Liver regeneration 4: transcriptional control of liver regeneration. Faseb J. 1996;10:413–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till JE, McCulloch E. A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat Res. 1961;14:213–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai RY, McKay RD. A nucleolar mechanism controlling cell proliferation in stem cells and cancer cells. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2991–3003. doi: 10.1101/gad.55671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai RY, McKay RD. A multistep, GTP-driven mechanism controlling the dynamic cycling of nucleostemin. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:179–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zayas RM, Guo T, Newmark PA. nanos function is essential for development and regeneration of planarian germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5901–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609708104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff E, Dubois F. Sur la migration des cellules de régénération chez les planaires. Revue Swisse Zool. 1948;55:218–227. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.