Abstract

This study examined the relation between immune response to cytomegalovirus (CMV) and all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality, and possible mediating mechanisms. Data were derived from the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging, a population-based study of older Latinos (aged 60–101 years) in California followed in 1998–2008. CMV immunoglobulin G (IgG), tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin-6 were assayed from baseline blood draws. Data on all-cause and CVD mortality were abstracted from death certificates. Analyses included 1,468 of 1,789 participants. For individuals with CMV IgG antibody titers in the highest quartile compared with lower quartiles, fully adjusted models showed that all-cause mortality was 1.43 times (95% confidence interval: 1.14, 1.79) higher over 9 years. In fully adjusted models, the hazard of CVD mortality was also elevated (hazard ratio = 1.35, 95% confidence interval: 1.01, 1.80). A composite measure of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 mediated a substantial proportion of the association between CMV and all-cause (18.9%, P < 0.001) and CVD (29.0%, P = 0.02) mortality. This study is the first known to show that high CMV IgG antibody levels are significantly related to mortality and that the relation is largely mediated by interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor. Further studies investigating methods for reducing IgG antibody response to CMV are warranted.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, cytomegalovirus, immune system, infection, inflammation

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a highly prevalent, easily transmissible beta herpesvirus (1, 2). Serious complications from infection are documented in vulnerable populations including infants, transplant recipients, and patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. CMV is not cleared from the body but rather persists in a number of tissues as a combination of a chronic productive infection and latent infection with periodic subclinical reactivation (2). Because of its lack of overt clinical symptoms, CMV was thought to be benign in immunocompetent hosts. However, researchers have paid increasing attention to CMV as an etiologic agent for chronic diseases and as a marker of immune dysfunction.

More recently, CMV has been linked with cancer (3), cardiovascular disease (4, 5), cognitive functioning including vascular dementia (6, 7), and functional impairment (8). It is thought that CMV contributes to progression of these disease processes primarily through inflammatory mechanisms, whereby infection with CMV induces production of cytokines and acute-phase proteins (9). CMV has also been implicated as a driving force in immunosenescence (10, 11). As a persistent infection, CMV is continually captured, processed, and presented to T cells, leading to clonal expansion and contraction of the adaptive immune system. Over time, this process leads to clonal exhaustion whereby CMV-specific T cells are present but anergic, leaving fewer naïve T cells to combat novel pathogens (11). Research has shown that this process is not a consequence of deteriorating health, comorbidity, or a general loss of immune control over the virus (12, 13).

Loss of cell-mediated control of CMV leads to increases in immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies specific to CMV. An ensuing increase in CMV IgG antibody levels may increase proinflammatory cytokines. The proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin 6 (IL-6), and immune parameter C-reactive protein, are secreted in response to CMV infection and have been shown to be independently associated with mortality from cardiovascular disease and all causes (14–16). Elevated levels of IL-6 and TNF have previously been shown to jointly predict cardiovascular events (17). Given the implication of CMV in a myriad of disease pathologies and biologic evidence suggesting that CMV potentiates these pathologies in several ways (9), with the induction of proinflammatory cytokines being particularly important (15), we would expect that individuals with higher IgG antibody titers to CMV would be at risk of premature mortality and that this relation would be partially or wholly mediated by proinflammatory cytokines.

Despite this growing body of work implicating CMV in multiple disease processes, there are few studies of CMV and prospective disease risk in population-based samples. The current study tested whether higher CMV IgG antibody levels were related to mortality from all causes and cardiovascular disease over 9 years of follow-up in a population-based cohort. We hypothesized that higher levels of CMV IgG antibodies would be associated with higher rates of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality, even after accounting for conventional risk factors for cardiovascular disease, and that the relation between CMV and mortality would be mediated by IL-6, TNF, and C-reactive protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

Data for these analyses were derived from the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging (SALSA), a large, representative, ongoing prospective cohort study of community-dwelling Latinos in California. Participants were 60–101 years of age at baseline in 1998–1999. Trained bilingual interviewers conducted in-home interviews covering sociodemographics, lifestyle factors, and medical diagnoses. A fasting blood sample was drawn on the day of the interview. More detailed information on the survey design has been published previously (18).

At baseline recruitment, 1,789 people were enrolled in the study. We excluded 229 participants without measures of antibody titers to CMV and an additional 92 without measures of our covariates at baseline. Observed participants who were excluded on the basis of missing covariates were significantly more likely to have died from all causes but not cardiovascular disease, to be older, to be male, to have less education, to not be hypertensive, and to have higher levels of TNF, at the P < 0.05 level (results not shown). Our analysis subsample comprised the 1,468 individuals with complete information on covariates included in final models. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Michigan and the University of California, Davis.

Laboratory analyses

Baseline frozen (−70°C) serum samples were analyzed for CMV and for TNF, IL-6, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used for detecting type-specific IgG antibody responses to CMV (Wampole Laboratories, Princeton, New Jersey) measured by optical density units with an assay sensitivity and specificity of 99% and 94%, respectively. TNF and IL-6 levels were determined by using the Quantiglo Chemiluminescent Immunoassay, QTA00B and Q6000B, respectively (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota). C-reactive protein levels were assayed with the CRP Ultra Wide Range Reagent Kit latex-enhanced immunoassay (Equal Diagnostics, Exton, Pennsylvania).

Outcomes

Mortality follow-up was available through June 2008, with 459 total deaths. The analysis subsample included 359 deaths from all causes, of which 220 were due to cardiovascular disease. Mortality ascertainment involved online obituary surveillance, review of the Social Security death index and the National Death Index, review of vital statistics data files from California, and telephone interviews with family members to track those participants who had moved. Death certificates were obtained for 90.2% (n = 414) of the deceased (n = 335, 93.3% of the analysis subsample). Information on cause of death was coded according to the Tenth Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Cardiovascular disease mortality was defined as deaths for which anywhere on the death certificate mentioned Tenth Revision codes for acute rheumatic fever, chronic rheumatic heart disease (codes I00–I09.9); hypertensive heart and renal diseases (codes I11, I13.9); ischemic heart disease, pulmonary heart disease, other cardiovascular diseases (codes I20–I51.9); and stroke (codes I60, I69.9). If a death certificate was not located, the individual was counted as dying from all-cause mortality, with the cause unspecified.

Covariates at baseline

Smoking was dichotomized as having never smoked or having ever smoked, because only 155 (10.6%) of the sample currently smoked. Hypertension was defined as antihypertensives use or a sitting systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg and/or a diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg. Education was divided into less than high school and high school or more. Morning fasting blood samples were used to measure low density lipoprotein cholesterol and high density lipoprotein cholesterol. A comorbidity index was created to control for the effect of chronic health conditions on mortality. Participants received one point for each of the following: myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, dementia, liver disease, diabetes, renal disease, any malignancy, and leukemia or lymphoma. The points were summed and participants were assigned a score between 0 and 9 reflecting the number of conditions reported at baseline.

Statistical analyses

The distributions of mortality and covariates were compared across quartiles of CMV IgG antibody titers by using chi-squared tests for general association. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the effect of CMV IgG antibody on all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. Survival time was measured in years since study enrollment. In cardiovascular disease models, the 139 deaths not attributable to cardiovascular disease were censored at the time of death. The association of CMV with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality, controlling for several covariates, was also examined. Covariates were screened as confounders based on hypothesized relations and were included in models if they were associated with the exposure and associated with the outcome among the unexposed (defined as the lowest 3 quartiles of CMV IgG; refer to the information below) (19, 20). Age, gender, and education were assessed as covariates because they are associated with death and CMV serostatus or age at infection (1, 21). Smoking status, hypertension, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high density lipoprotein cholesterol were assessed as covariates because they are associated with death (22, 23) and CMV infection. It is thought that CMV may be related to these risk factors through socioeconomic status. Low socioeconomic status may influence CMV IgG antibody levels by increasing frequency of exposure and transmission via crowded and poor living conditions, poorer nutrition, higher levels of stress, diabetes, and smoking (21, 24–26).

Since CMV has been implicated in the progression of many chronic diseases and may also reactivate as a consequence of chronic disease, including many of the conditions compiled in our comorbidity index (3, 4, 6, 11), it may mediate or confound the relation between CMV and mortality. Conservatively, we adjusted for number of comorbidities. Our final models excluded smoking status, hypertension, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high density lipoprotein cholesterol because they were unassociated with CMV in our population. The comorbidity index was included because, when modeled continuously, it was marginally positively associated with CMV IgG antibody titers and positively associated with death.

TNF, IL-6, and C-reactive protein were analyzed as mediators if they satisfied the criteria of Baron and Kenny (27): 1) CMV was associated with the marker(s), 2) the marker(s) was associated with mortality, and 3) if controlling for the inflammatory marker(s) significantly altered the association between CMV and mortality. Our final models excluded C-reactive protein because it was not associated with mortality in our sample, a finding compatible with other studies showing a null association (28). To investigate whether a systemic inflammatory reaction mediated the CMV–mortality association, we additionally analyzed whether TNF and IL-6 jointly mediated the CMV–mortality association by summing z scores for the individual cytokines. For the 6 possible mediation scenarios (e.g., CMV/all-cause mortality relation mediated by TNF), each individual relation (e.g., CMV and TNF) was assessed for possible confounding by using the set of controls and criteria described above. Path coefficients were estimated with SAS software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina), standardized by using the method developed by Herr (29), and the Sobel test was calculated by using equations developed by Preacher and Hayes (30).

CMV IgG antibody titers were parameterized as a dummy variable comparing the highest quartile with the bottom 3 quartiles combined. This categorization was used because examination of survival curves showed no differences between the first 3 quartiles regarding the outcomes of interest (refer to Web Figures 1 and 2, the first of 4 supplementary figures referred to as “Web Figure” in the text and posted on the Journal’s Web site (http://aje.oupjournals.org/)). TNF and IL-6 levels were log transformed (using the natural logarithm) to correct skewness. The comorbidity index was entered continuously.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed for CMV IgG antibody titers with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality over 9 or more years of follow-up. In this paper, curves are presented unadjusted and adjusted for age, gender, education, and baseline comorbidities (none/one or more). Stratified log-rank test statistics or Wilcoxon test statistics were calculated based on assessment of the proportional hazards assumptions through log-log plots. All analyses were conducted by using SAS 9.1 software, and graphic plots were created with STATA 10 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of our sample stratified by quartiles of CMV IgG antibody titers. Quartiles were broken at 3.64, 5.00, and 6.40 optical density units; 54 subjects were considered seronegative according to clinical test cutpoints. Those with higher CMV IgG antibody titers were more likely to die from all causes as well as from cardiovascular disease–specific causes; were older; were female; had less education; and had higher levels of TNF, IL-6, and C-reactive protein. There were no differences in CMV IgG antibody titers based on nativity, smoking status, hypertension, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and number of baseline health conditions. All differences were significant at the 0.05 alpha level using 2-tailed significance tests.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics, by Quartile of CMV IgG Titers, of Subjects in the SALSA Study (N = 1,468), California, 1998–2008

| Characteristic | Quartile |

P Value | |||||||

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| All-cause mortality (n = 1,468) | 76 | 21.17 | 76 | 21.17 | 86 | 23.96 | 121 | 33.70 | 0.0002 |

| CVD mortality (n = 1,329)a | 48 | 21.82 | 49 | 22.27 | 53 | 24.09 | 70 | 31.82 | 0.0202 |

| Age, years (n = 1,468) | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| <69.5 | 218 | 29.70 | 180 | 24.52 | 189 | 25.75 | 147 | 20.03 | |

| ≥69.5 | 149 | 20.30 | 187 | 25.48 | 178 | 24.25 | 220 | 29.97 | |

| Gender (n = 1,468) | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Male | 210 | 35.78 | 153 | 26.06 | 120 | 20.44 | 104 | 17.72 | |

| Female | 157 | 17.82 | 214 | 24.29 | 247 | 28.04 | 263 | 29.85 | |

| Education (n = 1,468) | 0.0076 | ||||||||

| <High school | 237 | 23.08 | 247 | 24.05 | 272 | 26.48 | 271 | 26.39 | |

| ≥High school | 130 | 29.48 | 120 | 27.21 | 95 | 21.54 | 96 | 21.77 | |

| Nativity (n = 1,468) | 0.349 | ||||||||

| US born | 186 | 25.00 | 200 | 26.88 | 177 | 23.79 | 181 | 24.33 | |

| Foreign born | 181 | 25.00 | 167 | 23.07 | 190 | 26.24 | 186 | 25.69 | |

| Smoking status (n = 1,465) | 0.4875 | ||||||||

| Never | 166 | 24.09 | 164 | 23.80 | 178 | 25.83 | 181 | 26.27 | |

| Ever | 200 | 25.77 | 203 | 26.16 | 187 | 24.10 | 186 | 23.97 | |

| Hypertension (n = 1,455) | 0.6628 | ||||||||

| Yes | 236 | 24.16 | 253 | 25.90 | 246 | 25.18 | 242 | 24.77 | |

| No | 126 | 26.36 | 112 | 23.43 | 117 | 24.48 | 123 | 25.73 | |

| Median LDL cholesterol (n = 1,458) | 0.9484 | ||||||||

| Below | 175 | 24.31 | 181 | 25.14 | 181 | 25.14 | 183 | 25.42 | |

| Above | 189 | 25.61 | 185 | 25.07 | 181 | 24.53 | 183 | 24.80 | |

| Median HDL cholesterol (n = 1,463) | 0.5958 | ||||||||

| Below | 174 | 24.89 | 182 | 26.04 | 164 | 23.46 | 179 | 25.61 | |

| Above | 191 | 25.00 | 184 | 24.08 | 201 | 26.31 | 188 | 24.61 | |

| Comorbidity indexb (n = 1,468) | 0.899 | ||||||||

| 0 | 180 | 25.42 | 180 | 25.42 | 171 | 24.15 | 177 | 25.00 | |

| ≥1 | 187 | 24.61 | 187 | 24.61 | 196 | 25.79 | 190 | 25.00 | |

| Median log(TNF) (n = 1,468) | 0.0036 | ||||||||

| Below | 202 | 27.52 | 199 | 27.11 | 173 | 23.57 | 160 | 21.80 | |

| Above | 165 | 22.48 | 168 | 22.89 | 194 | 26.43 | 207 | 28.20 | |

| Median log(IL-6) (n = 1,468) | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Below | 216 | 29.47 | 186 | 25.38 | 179 | 24.42 | 152 | 20.74 | |

| Above | 151 | 20.54 | 181 | 24.63 | 188 | 25.58 | 215 | 29.25 | |

| Median log(CRP) (n = 1,468) | 0.0008 | ||||||||

| Below | 203 | 27.81 | 189 | 25.89 | 188 | 25.75 | 150 | 20.55 | |

| Above | 164 | 22.22 | 178 | 24.12 | 179 | 24.25 | 217 | 29.40 | |

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL, high density lipoprotein; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IL-6, interleukin 6; LDL, low density lipoprotein; SALSA, Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Excludes non-CVD deaths.

Includes myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, dementia, liver/renal disease, diabetes, malignancy, and leukemia or lymphoma.

Table 2 presents hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals from Cox proportional hazards models of all-cause mortality. In bivariate models, all variables were significantly associated with all-cause mortality. In model 1, CMV IgG antibody titers were associated with an increased hazard of death (hazard ratio = 1.59, 95% confidence interval: 1.28, 1.98). When we adjusted for age, gender, and education, the top quartile of CMV IgG antibody titers was associated with a 39% (95% confidence interval: 11, 74) increased hazard of all-cause mortality (model 2). Model 3 added the comorbidity index; the hazard ratio for CMV increased slightly (hazard ratio = 1.43, 95% confidence interval: 1.14, 1.79). Models 4, 5, and 6 added the mediators TNF, IL-6, and both cytokines together, respectively, and reduced the CMV IgG antibody relation with all-cause mortality by 19%, 14%, and 21%, respectively, although all estimates were still statistically significant.

Table 2.

CMV IgG Titers and Rate of All-cause Mortality Among Subjects in the SALSA Study (N = 1,468), California, 1998–2008

| Model |

||||||||||||

| 1a |

2b |

3b |

4b |

5b |

6b |

|||||||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| CMV antibody titers (highest quartilec) | 1.59 | 1.28, 1.98 | 1.39 | 1.11, 1.74 | 1.43 | 1.14, 1.79 | 1.28 | 1.02, 1.61 | 1.36 | 1.09, 1.70 | 1.25 | 1.00, 1.58 |

| Biomarkers | ||||||||||||

| Comorbidity indexd | 1.46 | 1.37, 1.56 | 1.39 | 1.30, 1.48 | 1.35 | 1.27, 1.45 | 1.37 | 1.29, 1.47 | 1.35 | 1.26, 1.44 | ||

| Log(TNF) | 2.47 | 2.03, 2.99 | 1.81 | 1.45, 2.26 | 1.69 | 1.34, 2.12 | ||||||

| Log(IL-6) | 1.73 | 1.50, 2.00 | 1.41 | 1.21, 1.66 | 1.33 | 1.13, 1.56 | ||||||

| Demographics (reference) | ||||||||||||

| Age | 1.10 | 1.09, 1.12 | 1.10 | 1.08, 1.11 | 1.09 | 1.07, 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.07, 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.07, 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.07, 1.09 |

| Gender (female) | 1.29 | 1.05, 1.59 | 1.42 | 1.15, 1.75 | 1.49 | 1.21, 1.85 | 1.52 | 1.23, 1.88 | 1.50 | 1.21, 1.85 | 1.52 | 1.23, 1.88 |

| Education (<high school) | 1.85 | 1.43, 2.39 | 1.49 | 1.15, 1.93 | 1.53 | 1.18, 1.98 | 1.46 | 1.12, 1.89 | 1.49 | 1.15, 1.93 | 1.44 | 1.11, 1.87 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMV, cytomegalovirus; HR, hazard ratio; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IL-6, interleukin 6; SALSA, Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Model 1: bivariate relation with mortality.

Models 2–5: include variables with hazard ratio estimates.

Reference: lower quartiles.

Includes myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, dementia, liver/renal disease, diabetes, malignancy, and leukemia or lymphoma.

Table 3 replicates the analyses of Table 2 but with cardiovascular disease mortality as the outcome. Models 1–3 show a similar pattern of positive associations between CMV and cardiovascular disease; however, model 2 confidence intervals included the null value. Models 4, 5, and 6, which added TNF, IL-6, and both cytokines together, respectively, reduced the relation between CMV and cardiovascular disease mortality by 20%, 13%, and 22%, respectively. TNF and IL-6 were significantly, positively associated with the risk of both overall and cardiovascular disease–specific mortality in both unadjusted and fully adjusted models.

Table 3.

CMV IgG Titers and Rate of CVD Mortality Among Subjects in the SALSA Study (N = 1,486), California, 1998–2008

| Model |

||||||||||||

| 1a |

2b |

3b |

4b |

5b |

6b |

|||||||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| CMV IgG titers (highest quartilec) | 1.47 | 1.11, 1.95 | 1.30 | 0.97, 1.74 | 1.35 | 1.01, 1.80 | 1.17 | 0.87, 1.58 | 1.28 | 0.96, 1.71 | 1.15 | 0.86, 1.55 |

| Biomarkers | ||||||||||||

| Comorbidity indexd | 1.51 | 1.39, 1.64 | 1.44 | 1.33, 1.57 | 1.4 | 1.29, 1.52 | 1.43 | 1.31, 1.55 | 1.40 | 1.29, 1.52 | ||

| Log(TNF) | 2.66 | 2.09, 3.38 | 2.00 | 1.51, 2.64 | 1.87 | 1.40, 2.49 | ||||||

| Log(IL-6) | 1.76 | 1.47, 2.11 | 1.44 | 1.17, 1.76 | 1.33 | 1.08, 1.64 | ||||||

| Demographics (reference) | ||||||||||||

| Age | 1.11 | 1.09, 1.12 | 1.10 | 1.08, 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.07, 1.11 | 1.08 | 1.07, 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.07, 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.06, 1.10 |

| Gender (female) | 1.44 | 1.11, 1.88 | 1.57 | 1.20, 2.05 | 1.67 | 1.28, 2.19 | 1.71 | 1.30, 2.24 | 1.67 | 1.28, 2.19 | 1.71 | 1.31, 2.24 |

| Education (<high school) | 2.01 | 1.44, 2.81 | 1.62 | 1.16, 2.28 | 1.67 | 1.19, 2.34 | 1.58 | 1.13, 2.22 | 1.63 | 1.16, 2.29 | 1.57 | 1.12, 2.20 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IL-6, interleukin 6; SALSA, Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Model 1: bivariate relation with mortality.

Models 2–5: include variables with hazard ratio estimates.

Reference: lower quartiles.

Includes myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, dementia, liver/renal disease, diabetes, malignancy, and leukemia or lymphoma.

Table 4 shows the results of our statistical assessment of mediation. TNF and IL-6 individually mediated a significant and substantial portion of the effect of CMV on mortality (10.9% to 23.9%). TNF and IL-6 combined mediated an even larger proportion of the association between CMV and all-cause (18.9%, P < 0.001) and cardiovascular disease (29.0%, P = 0.02) mortality.

Table 4.

Mediation of Associations Between CMV IgG Titers and Mortality by Cytokines Among Subjects in the SALSA Study (N = 1,468), California, 1998–2008

| Cytokine | All-cause Mortality |

CVD Mortality |

||||

| Percent Mediated | Ratioa | Sobel's Test (P Value) | Percent Mediated | Ratioa | Sobel's Test (P Value) | |

| Log(TNF) | 10.81 | 0.03 | 2.20 (0.0275) | 17.47 | 0.05 | 2.11 (0.0353) |

| Log(IL-6) | 14.90 | 0.03 | 1.78 (0.0746) | 23.92 | 0.04 | 1.62 (0.1056) |

| Combinedb | 18.87 | 0.12 | 2.58 (0.0010) | 28.97 | 0.23 | 2.43 (0.0151) |

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IL-6, interleukin 6; SALSA, Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Indirect to direct effect.

Log-transformed cytokines combined by summing individual cytokine z scores.

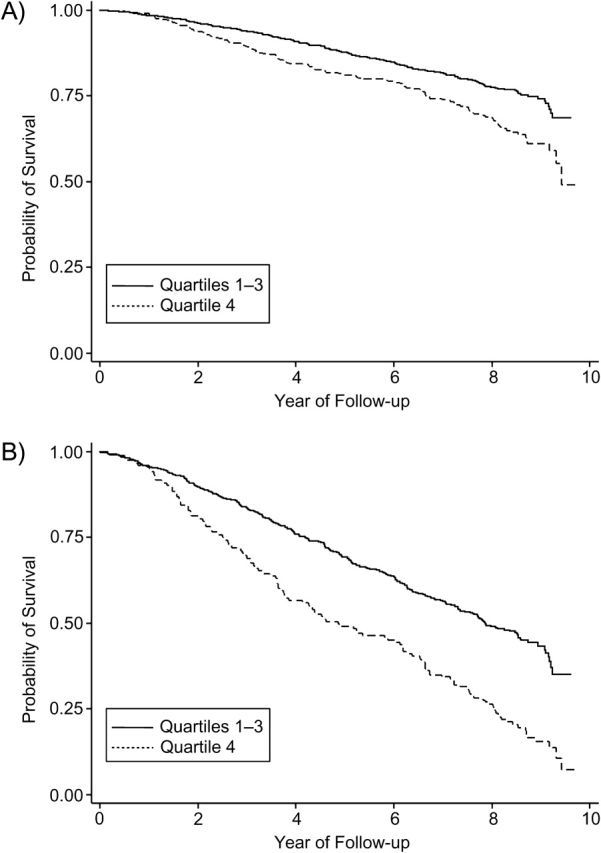

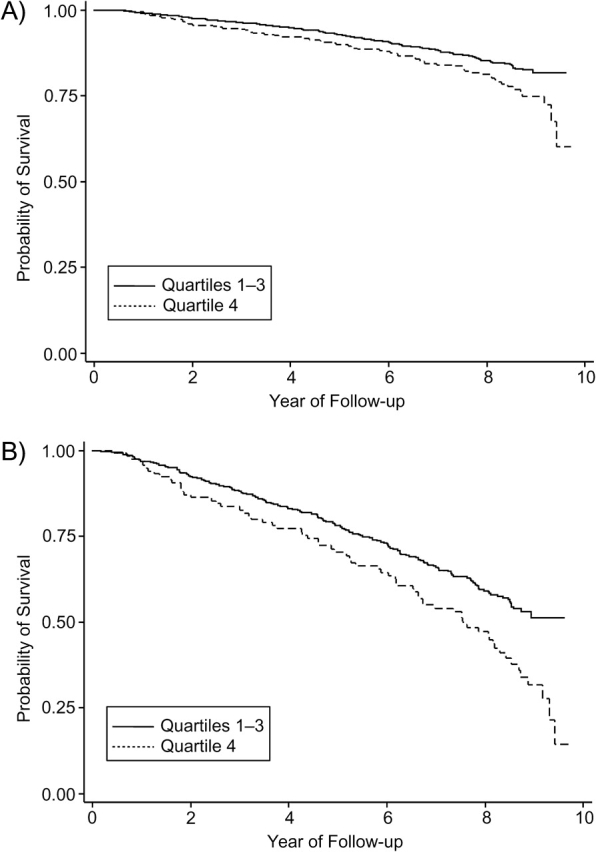

Figure 1 shows Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all-cause mortality by CMV IgG antibody titers. Panel A displays unadjusted associations. The stratified log-rank test statistic for the difference in survival curves was 17.6, P < 0.001. Panel B shows the probability of survival for an above-average-age male with less than a high school education and one or more baseline comorbidities. The stratified log-rank test statistic was 17.04, P < 0.001. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for cardiovascular disease mortality by CMV IgG antibody titers. The stratified log-rank tests were statistically significant. In both Figures 1 and 2, the highest quartile of CMV IgG antibody predicted a significantly worse survival probability over 9 years of follow-up.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all-cause mortality by cytomegalovirus immunoglobulin G antibody titers for 1,468 subjects in the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging (California) from 1998 to 2008. Cytomegalovirus is divided into quartiles 1, 2, and 3 versus quartile 4. Panel A: unadjusted relation; panel B: adjusted for gender (male/female), age (above/below the mean), education (less than high school/high school or more), and comorbidities (none/one or more). Panel B shows survival for males older than 69 years of age with less than a high school education and one or more baseline comorbidities. Stratified log-rank test statistics were 17.6 (P < 0.001) for panel A and 17.04 (P < 0.001) for panel B.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for cardiovascular disease mortality by cytomegalovirus immunoglobulin G antibody titers for 1,468 subjects in the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging (California) from 1998 to 2008. Cytomegalovirus is divided into quartiles 1, 2, and 3 versus quartile 4. Panel A: unadjusted relation; panel B: adjusted for gender (male/female), age (above/below the mean), education (less than high school/high school or more), and comorbidities (none/one or more). Panel B shows survival for males older than 69 years of age with less than a high school education and one or more baseline comorbidities. Stratified log-rank test statistics were 7.08 (P < 0.01) for panel A and 7.05 (P < 0.01) for panel B.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 1,468 community-dwelling elderly Latinos, we found that increasing CMV IgG antibody titers were associated with all-cause mortality even after adjusting for a number of important covariates such as age, gender, education, and baseline health conditions. Adjustment reduced the significance levels for the relation between CMV IgG antibody titers and cardiovascular disease mortality, but the direction of the association between CMV IgG and risk of cardiovascular death remained positive. The Sobel test suggests that a substantial proportion of the relation between CMV and mortality was mediated by TNF and IL-6. Survival curves suggest significantly worse all-cause and cardiovascular disease survival for individuals in the highest quartile of CMV IgG antibody titers over 9 years of follow-up.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to report on the relation between CMV IgG antibody levels and mortality in a population-based cohort. These results are in agreement with the few available studies examining CMV seropositivity and all-cause mortality. In the Swedish longitudinal OCTO Immune Study, mortality was related to CMV-driven characteristic immune system changes now recognized as part of the immune risk profile (31). Similar findings were replicated in the Swedish NONA Immune Study (13). However, these 2 studies had modest sample sizes (102 and 138 participants, respectively), utilized specialized populations (very healthy oldest-old Swedes and oldest-old Swedes, respectively; the oldest old were aged 86–94 years at baseline), and examined seropositivity rather than antibody levels.

Our study extends these earlier findings by testing the association with antibody levels, examining the relation in a larger sample, using a broader age range and a longer period of follow-up, and utilizing a general population sample in the United States representing a growing ethnic group. Other studies have noted the importance of high anti-CMV antibody titers to cardiovascular disease progression and outcomes (32–34). Given that approximately 80% of individuals aged 65 years or older are seropositive for CMV (1), it is unlikely that infection serostatus alone will explain disease and mortality outcomes. Measuring antibody response, on the other hand, may capture subclinical reactivation of CMV and therefore may be more relevant for examining CMV-induced inflammation and immune system dysfunction than seropositivity alone (16, 35). Thus, our novel results concerning mortality support earlier work showing that immune response to CMV is related to a myriad of diseases including cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline, and physical functioning (6, 8, 32–34).

Several mechanisms may explain why a higher CMV antibody level is associated with an increased risk of mortality. First, reactivation of CMV likely contributes to cell damage through inflammatory pathways (9, 15, 17). We observed a 20% and 13% decrease in our hazard ratio for CMV when including TNF and IL-6, respectively, in cardiovascular disease models (19% and 14%, respectively, for all-cause models). Statistical tests of mediation showed that TNF and IL-6 mediated a substantial portion of the effect of CMV on all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. Given that we were measuring peripheral circulating levels of TNF and IL-6 rather than direct stimulated cellular production of these cytokines, our results likely underestimated the mediating effect of cytokines on mortality. We found no association between levels of C-reactive protein and mortality in our sample. Mean levels of C-reactive protein in our sample (4.56 mg/L in men and 7.07 mg/L in women) were higher than values typically reported in white, non-Hispanic elderly populations (36). However, these earlier studies were conducted on populations of predominantly European ancestry, meaning that potentially important genetic and/or cultural differences when comparing across race/ethnic populations remain unaccounted for (28). More research on the association between C-reactive protein and mortality among ethnically diverse elderly populations is needed.

Second, CMV infection has been implicated as a key component in immunosenescence (10, 11). It is known that the elderly are particularly susceptible to some infectious diseases and cancer (11, 16). This increased susceptibility may be due to alterations in immune function related to CMV infection, whereby the reduced number of naïve T cells reduces the body's ability to clear novel pathogens or genetically altered self-proteins. Additionally, CMV has been classified as oncomodulatory because of its ability to disrupt key cell signaling pathways (9).

Whereas the association between CMV and cardiovascular disease mortality was statistically insignificant in models 4–6 when we added the mediators (TNF and IL-6), we would not interpret this occurrence as suggesting that inflammatory processes mediate the entire effect of CMV on cardiovascular disease mortality. Post-hoc power calculations indicated a 60% chance of rejecting a false-null hypothesis for all-cause mortality models; for cardiovascular disease, there was only a 20% chance of rejecting a false-null hypothesis. Thus, future studies with larger samples are needed to confirm or refute the novel findings presented here. Furthermore, our study population had moderate levels of some comorbidities including baseline cardiovascular disease (21%). Therefore, we examined models for the subset of individuals without a history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, heart failure, or stroke at baseline to investigate the association of CMV with new-onset cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. We observed similar point estimates with slightly wider 95% confidence intervals (results not shown). Further research is needed to clarify the relation between CMV and cardiovascular disease among younger populations who are disease free at baseline.

There are several limitations to our study. First, we were unable to examine other cellular immune markers in relation to CMV antibody levels since peripheral blood mononuclear cells were unavailable. In addition, CMV IgG antibodies were measured at baseline only. Scant evidence exists that CMV IgG changes with time within individuals, but cross-sectional data suggest that CMV increases with age over several years or more (35). While antibody levels appear to increase with age, Olsson et al. (31) found, over 8 years of follow-up, that 100% of subjects with a CD4/CD8 ratio of less than 1 were CMV seropositive compared with 87% of subjects with a CD4/CD8 ratio greater than 1 and that no subjects changed from an unfavorable to a favorable CD4/CD8 ratio over this period, suggesting that CMV-related immune alterations are stable. Therefore, our baseline measures of CMV IgG antibody titers, along with age-adjusted models, likely provide a robust measure of stable CMV-related immune alterations.

Second, several studies have implicated other infectious agents such as Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori, and other herpesviruses as causative disease agents, particularly via their contribution to atherosclerosis through inflammatory pathways (4). In Cox models and survival curves examining the association of herpes simplex virus 1 with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality, we observed null associations (Web Figures 3 and 4). This observation is in agreement with previous findings (5, 6, 37) and highlights the importance of CMV as a specific marker of immune dysfunction and a predictor of mortality. Still, we cannot rule out total pathogen burden or other specific infections as a possible alternative explanation.

Third, it is possible that accidental deaths (e.g., from a car crash) were inappropriately included in our sample. Examination of the immediate cause of death indicated only 2 possible accidental deaths in our sample (dehydration and inanition). Removal of these 2 deaths from consideration had little to no effect on the reported associations (results not shown).

Fourth, it is important to consider the natural history of CMV infection over the life course (2). Seropositivity is nearly ubiquitous by later life, with infection often occurring at a young age (1). Research has shown that stress alters the immune system, leading to reactivation of latent viral infections and increased levels of herpesvirus antibody titers, including CMV (38). Reactivation is a key component in many of the observed deleterious immune system alterations (11). It is possible that Latinos residing in the United States have unique life course experiences that influence exposure, response, and reactivation of CMV (1, 21) as well as their mortality rates. For example, country of birth, duration since migration, and acculturation might influence CMV infection and mortality. Country of birth was not related to CMV quartiles or mortality in our sample, but those born outside of the United States were more likely to be excluded from this sample because of missing data. Future studies in ethnically heterogeneous populations would help answer these questions. Last, our study used self-reported comorbidity data. Others have documented good agreement between self-reported medical conditions and medical records among elderly patients (39).

Controlling the deleterious effects of CMV infection and understanding the causes of age-related immune decline are important public health issues. Our finding that individuals in the highest quartile of CMV IgG antibody titers are at increased risk of mortality calls for continued investigation of the broader social conditions contributing to both CMV infection and reactivation over the life course given the strong socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in CMV antibody levels and infection status (21, 24, 37). Alongside efforts to control reactivation, primary prevention efforts are warranted. CMV vaccines are currently being developed; however, to date, only one has undergone efficacy evaluation in humans (40).

In conclusion, this study contributes to growing evidence that CMV immune response is related to the deleterious processes involved in aging, contributing to premature mortality. Our novel results suggest that the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF are a primary mechanism of action related to immune response to CMV and its relation with mortality. Further studies elucidating the biologic mechanisms underlying the association between CMV and chronic disease are needed. These results suggest more urgency in investigating strategies to reduce CMV exposure and IgG antibody levels among infected individuals over the life course.

Acknowledgments

Author affiliations: Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Eric T. Roberts, Mary N. Haan, Allison E. Aiello); Center for Social Epidemiology and Population Health, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Eric T. Roberts, Allison E. Aiello); School of Health Sciences, Hunter College, City University of New York, New York, New York (Jennifer Beam Dowd); and CUNY Institute for Demographic Research (CIDR), New York, New York (Jennifer Beam Dowd).

This work was supported by grants AG12975, NIH5P60 DK20572 and DK60753, R21 NR011181-01, and P60 MD002249 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

References

- 1.Staras SA, Dollard SC, Radford KW, et al. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the United States, 1988–1994. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(9):1143–1151. doi: 10.1086/508173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britt W. Manifestations of human cytomegalovirus infection: proposed mechanisms of acute and chronic disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:417–470. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samanta M, Harkins L, Klemm K, et al. High prevalence of human cytomegalovirus in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostatic carcinoma. J Urol. 2003;170(3):998–1002. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000080263.46164.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu R, Moroi M, Yamamoto M, et al. Presence and severity of Chlamydia pneumoniae and cytomegalovirus infection in coronary plaques are associated with acute coronary syndromes. Int Heart J. 2006;47(4):511–519. doi: 10.1536/ihj.47.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorlie PD, Nieto FJ, Adam E, et al. A prospective study of cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus 1, and coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(13):2027–2032. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aiello AE, Haan M, Blythe L, et al. The influence of latent viral infection on rate of cognitive decline over 4 years. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1046–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin WR, Wozniak MA, Wilcock GK, et al. Cytomegalovirus is present in a very high proportion of brains from vascular dementia patients. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;9(1):82–87. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiello AE, Haan MN, Pierce CM, et al. Persistent infection, inflammation, and functional impairment in older Latinos. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(6):610–618. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.6.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Söderberg-Nauclér C. Does cytomegalovirus play a causative role in the development of various inflammatory diseases and cancer? J Intern Med. 2006;259(3):219–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pawelec G, Derhovanessian E, Larbi A, et al. Cytomegalovirus and human immunosenescence. Rev Med Virol. 2009;19(1):47–56. doi: 10.1002/rmv.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pawelec G, Koch S, Franceschi C, et al. Human immunosenescence: does it have an infectious component? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1067:56–65. doi: 10.1196/annals.1354.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson BO, Ernerudh J, Johansson B, et al. Morbidity does not influence the T-cell immune risk phenotype in the elderly: findings in the Swedish NONA Immune Study using sample selection protocols. Mech Ageing Dev. 2003;124(4):469–476. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(03)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wikby A, Nilsson BO, Forsey R, et al. The immune risk phenotype is associated with IL-6 in the terminal decline stage: findings from the Swedish NONA Immune Longitudinal Study of very late life functioning. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127(8):695–704. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, et al. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am J Med. 1999;106(5):506–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stassen FR, Vega-Córdova X, Vliegen I, et al. Immune activation following cytomegalovirus infection: more important than direct viral effects in cardiovascular disease? J Clin Virol. 2006;35(3):349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trzonkowski P, Myśliwska J, Szmit E, et al. Association between cytomegalovirus infection, enhanced proinflammatory response and low level of anti-hemagglutinins during the anti-influenza vaccination—an impact of immunosenescence. Vaccine. 2003;21(25-26):3826–3836. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cesari M, Penninx BW, Newman AB, et al. Inflammatory markers and onset of cardiovascular events: results from the Health ABC Study. Circulation. 2003;108(19):2317–2322. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097109.90783.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haan MN, Mungas DM, Gonzalez HM, et al. Prevalence of dementia in older Latinos: the influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke and genetic factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(2):169–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenland P, Daviglus ML, Dyer AR, et al. Resting heart rate is a risk factor for cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality: the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(9):853–862. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, editors. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dowd JB, Haan MN, Blythe L, et al. Socioeconomic gradients in immune response to latent infection. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(1):112–120. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, et al. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328(7455):1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. (doi:10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990;335(8692):765–774. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dowd JB, Aiello AE, Alley DE. Socioeconomic disparities in the seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the US population: NHANES III. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137(1):58–65. doi: 10.1017/S0950268808000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernández-Real JM, López-Bermejo A, Vendrell J, et al. Burden of infection and insulin resistance in healthy middle-aged men. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(5):1058–1064. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2951058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee DJ, LeBlanc W, Fleming LE, et al. Trends in US smoking rates in occupational groups: the National Health Interview Survey 1987–1994. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46(6):538–548. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000128152.01896.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casas JP, Shah T, Hingorani AD, et al. C-reactive protein and coronary heart disease: a critical review. J Intern Med. 2008;264(4):295–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herr NR. Mediation with dichotomous outcomes. ( http://nrherr.bol.ucla.edu/Mediation/logmed.html). (Accessed December 15, 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsson J, Wikby A, Johansson B, et al. Age-related change in peripheral blood T-lymphocyte subpopulations and cytomegalovirus infection in the very old: the Swedish Longitudinal OCTO Immune Study. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;121(1-3):187–201. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blum A, Giladi M, Weinberg M, et al. High anti-cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgG antibody titer is associated with coronary artery disease and may predict post-coronary balloon angioplasty restenosis. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81(7):866–868. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nieto FJ, Adam E, Sorlie P, et al. Cohort study of cytomegalovirus infection as a risk factor for carotid intimal-medial thickening, a measure of subclinical atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1996;94(5):922–927. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strandberg TE, Pitkala KH, Tilvis RS. Cytomegalovirus antibody level and mortality among community-dwelling older adults with stable cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2009;301(4):380–382. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stowe RP, Kozlova EV, Yetman DL, et al. Chronic herpesvirus reactivation occurs in aging. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42(6):563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sattar N, Murray HM, McConnachie A, et al. C-reactive protein and prediction of coronary heart disease and global vascular events in the Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) Circulation. 2007;115(8):981–989. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.643114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simanek AM, Dowd JB, Aiello AE. Persistent pathogens linking socioeconomic position and cardiovascular disease in the US. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(3):775–787. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herbert TB, Cohen S. Stress and immunity in humans: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 1993;55(4):364–379. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bush TL. Self-report and medical record report agreement of selected medical conditions in the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(11):1554–1556. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.11.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khanna R, Diamond DJ. Human cytomegalovirus vaccine: time to look for alternative options. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]