Summary

Analyses of plant tolerance in response to different modes of herbivory are essential to understand plant defense evolution, yet are still scarce. Allocation costs and trade-offs between tolerance and plant chemical defenses may influence genetic variation for tolerance. However, variation in defenses occurs also for presence or absence of discrete chemical structures, yet, effects of intra-specific polymorphisms on tolerance to multiple herbivores have not been evaluated.

Here, in a glasshouse experiment, we investigated variation for tolerance to different types of herbivory damage, and direct allocation costs in 10 genotypes of Boechera stricta (Brassicaceae), a wild relative of Arabidopsis, with contrasting foliar glucosinolate chemical structures (methionine-derived glucosinolates vs glucosinolates derived from branched-chain amino acids).

We found significant genetic variation for tolerance to different types of herbivory. Structural variations in the glucosinolate profile did not influence tolerance to damage, but predicted plant fitness. Levels of constitutive and induced glucosinolates varied between genotypes with different structural profiles, but we did not detect any cost of tolerance explaining genetic variation in tolerance among genotypes.

Trade-offs among plant tolerance to multiple herbivores may not explain the existence of intermediate levels of tolerance to damage in plants with contrasting chemical defensive profiles.

Keywords: constitutive glucosinolates, genetic variation, generalist herbivores, herbivory, induced glucosinolates, plant defenses, tolerance, specialist herbivores

Introduction

Plants have a rich diversity of defensive adaptations against herbivores, which may enable resistance to herbivore attack or tolerance of damage. In the first case, plants rely on traits that reduce herbivore damage on plant tissues, such as trichomes, spines or toxic secondary compounds (reviewed in Strauss & Zangerl, 2002). Alternatively, some plant genotypes may be less susceptible to negative impacts when herbivore damage occurs (Strauss & Agrawal, 1999). In both cases, plant defensive traits are typically genetically complex quantitative traits (Rosenthal & Kotanen, 1994; Weinig et al., 2003; Agrawal & Fishbein, 2006; Schranz et al., 2009), and often show heritable variation within and among populations (e.g., Fornoni & Nuñez-Farfán, 2000; Kliebenstein et al., 2001; Windsor et al., 2005; Løe et al., 2007). In particular, plant tolerance to damage (the ability to regrow and reproduce after herbivory, Strauss & Agrawal, 1999) is genetically variable in many species (reviewed by Strauss & Agrawal, 1999; Fornoni et al., 2003; Nuñez-Farfán et al., 2007; but see Ivey et al., 2009), and therefore, may evolve in response to natural selection. However, the ecological and genetic basis of tolerance variation still is not well understood, especially among populations (Fornoni et al., 2003).

The expression of plant tolerance to damage varies among environments (Wise & Abrahamson, 2007). Resource availability, the timing and magnitude of damage, and the type of herbivore damage are important ecological factors influencing the evolution of tolerance (e.g., Maschinski & Whitham, 1989; Strauss & Agrawal, 1999; Tiffin, 2002; Stevens et al., 2007; Suwa & Maherali, 2008). In particular, tolerance to damage is often dependent upon the type of tissue damaged – that is, apical versus foliar damage, damage on young leaves versus mature ones, or damage to roots versus leaves (e.g., Houle & Simard, 1996; Stinchcombe, 2002; Boalt & Lehtilä, 2007; but see Tiffin & Rausher, 1999). However, these studies simulate damage mainly through manual clipping, which may be a poor surrogate for genuine herbivory (Strauss & Agrawal, 1999). In addition, little is known about how different kinds of herbivore damage influence tolerance to herbivory across naturally varying genotypes (but see Agrawal et al., 1999; Tiffin & Rausher, 1999; Pilson, 2000). However, to understand the evolution of tolerance, it is essential to determine whether conspecific genotypes show differential tolerance to herbivore damage. Furthermore, plants are often attacked by multiple herbivore species, so we must examine diverse generalist and specialist herbivores feeding on different parts of the plant. In addition, plants face different types of herbivores across their ranges, which may result in different ecological and evolutionary outcomes (Thompson, 1988; Stinchcombe & Rausher, 2002; Strauss & Irwin, 2004).

The influence of quantitative intraspecific variation in plant chemical defenses on tolerance to damage is frequently studied in the context of ecological trade-offs and direct costs of tolerance (Strauss et al., 2002; Leimu & Koricheva, 2006). Allocation costs occur when there are significant negative genetic correlations between tolerance and resistance, or between tolerance and fitness in the absence of herbivores. Such costs are thought to maintain the existing levels of genetic variation in tolerance within species (Strauss & Agrawal, 1999; Strauss et al., 2002), but they are not always detected (Leimu & Koricheva, 2006). Both tolerance to damage and the magnitude and significance of tolerance costs may depend on phenotypic plasticity, such as differences in trait expression through ontogeny (Boege et al., 2007; Barton, 2008) or in levels of defense induction (Agrawal, 1998, 1999). However, genetic variation in chemical defenses occurs not merely at the quantitative level but also for presence or absence of discrete chemical structures (e.g., Schranz et al., 2009), and differential allocation costs could arise among genotypes with different chemical compositions, especially if geographical structure underlies such variation. Recent studies have shown that constitutive structural polymorphism in chemical plant defenses affects plant resistance to herbivores and influences herbivore communities (Newton et al., 2009; Schranz et al., 2009), yet, to our knowledge, effects of intra-specific chemical polymorphism on plant fitness have not been evaluated in the context of herbivore tolerance. However, if distinct defensive compounds have different biosynthetic costs, then such structural polymorphisms in plant chemical defenses may also influence tolerance or its costs (Koricheva, 2002 and references therein).

Here, we investigate genetic variation in tolerance to different types of damage, and the allocation costs of tolerance to damage in genotypes of Boechera stricta (Brassicaceae) with contrasting foliar glucosinolate chemical structures. Tolerance is defined here as the difference in fitness between damaged and undamaged plants (Strauss & Agrawal, 1999). In B. stricta, heritable natural polymorphism exists in aliphatic glucosinolates within and among populations (Schranz et al., 2009). Although Arabidopsis, Brassica, and most other crucifers produce leaf glucosinolates largely derived from the amino acids methionine or tryptophan, some genotypes of B. stricta synthesize glucosinolates from the branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) valine, leucine, or isoleucine (Windsor et al., 2005; Schranz et al., 2009). Although there is currently little information about the ecological role of BCAA-derived aliphatic glucosinolates, recent QTL mapping has shown that heritable resistance to the larvae of the generalist lepidopteran Trichoplusia ni (Noctuidae) varies significantly between genotypes with contrasting glucosinolate profiles (Schranz et al., 2009). In particular, lines producing methionine-derived glucosinolates were significantly more resistant and suffered less leaf herbivory than lines producing predominantly BCAA-derived glucosinolates (Schranz et al., 2009). In addition, biosynthesis of BCAA and methionine-derived glucosinolates is controlled by different genes using different metabolic pathways (Mikkelsen & Halkier, 2003), which may affect tolerance if differences in the biosynthetic costs of such compounds vary.

To our knowledge, ours is the first investigation of the effects of natural structural polymorphism in plant chemical defenses on tolerance to different herbivores. Specifically, we address the following questions: (1) is there genetic variation in B. stricta for tolerance to herbivory? If so, (2) does this variation depend on the type of herbivore damage or the glucosinolate structural profile (glucosinolates derived from methionine vs BCAA). (3) Do allocation costs explain the observed genetic variation in tolerance to damage in B. stricta?, (4) Is the magnitude and significance of tolerance costs determined by the type of herbivore damage, the structural glucosinolate profile, or by glucosinolate induction? We seek to determine the ecological and evolutionary significance of non-methionine derived aliphatic glucosinolates in plant defense to herbivory.

Materials and Methods

Study system

Boechera stricta (previously Arabis drummondii) is a morphologically and genetically well-defined, monophyletic, short-lived perennial herb distributed across diverse habitats in western North America (Mitchell-Olds, 2001; Song et al., 2006). B. stricta is a predominantly self-fertilizing, sexual diploid, and is attacked by a wide array of specialist (e.g., the pierid Pontia spp.) and generalist insect herbivores (e.g., noctuids, grasshoppers, flea beetles and weevils). In the field, levels of individual plant damage range between 0–100% (average damage per leaf, 8.8 %; average proportion of leaves damaged, 13.1 %), and there is substantial variation in the average herbivore damage among populations and years (T. Mitchell-Olds, unpublished). Plants produce between one–five inflorescences in late spring, and both fruit maturation and seed set takes place in June–July.

Like other members of the Brassicaceae, B. stricta produces glucosinolates, which constitute a primary chemical defense against herbivores (Hopkins et al., 2009). There is extensive natural genetic variation for type and quantity of glucosinolates within and among natural populations (Windsor et al., 2005; Schranz et al., 2009). The glucosinolate polymorphism controls allocation to BCAA- versus methionine-derived glucosinolates and predicts levels of herbivory (Schranz et al., 2009).

Because a large portion of genetic polymorphism in B. stricta is distributed among populations (Song et al., 2006), we examined one genotype from each population, in order to maximize genetic variation for a given sample size. We considered nine genotypes from our study areas in the Northern Rocky Mountains (see later and Supporting Information Fig. S1). One of these genotypes (Lost Trail, Montana) has been used as a parent for QTL mapping of insect resistance (Schranz et al., 2009), hence the other parent (Taylor River, Colorado) was also included for comparison.

Experimental procedure

Mature seeds of 10 genotypes were collected from 10 different populations located in the Rocky Mountains in western United States (in Montana, Idaho and Colorado, see Fig. S1 and Table S1 for details). Those populations are diverse in ecological conditions and also differ in the levels of plant damage received by the plants. Genotypes included in the experiment were selected on the basis of their chemical background: four genotypes produce mainly BCAA-derived glucosinolates, and six genotypes produce methionine-derived glucosinolates (Table S1). We minimized potential maternal effects by using seeds from a second generation of self-fertilized, glasshouse-grown plants.

In November 2007, we placed 12 self-sib seeds/genotype into Petri dishes at 4°C for 6 wk of cold stratification. Once germinated, 11 seeds per genotype were individually planted and grown on standard soil (Fafard 4p mix; MA, USA) in a randomized complete blocks design, with the blocks consisting of one tray of 40 (5× 5× 6 cm) pots, distributed randomly within the tray. Those trays were placed in the Duke University glasshouse under controlled growth conditions. After c. 6 wk, plants were moved to a growth chamber (22°C, 16 h light and 8 h dark) and randomly assigned to the following four treatments: (1) undamaged control; (2) specialist herbivore treatment, with 33% of plant leaf area damaged by a caged second-instar Pieris rapae larva (Lepidoptera: Pieridae); (3) generalist herbivore treatment, with 33% of plant leaf area damaged by a caged second-instar Trichoplusia ni larva (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae); (4) manual clipping treatment, with 33% of each leaf clipped and removed using scissors. Therefore, each of the 10 genotypes had 11 individuals (replicated in blocks) in each of the four treatments, for a total of 440 plants.

Insect species used here are not native enemies of B. stricta, but they have been used extensively to investigate plant functional responses to herbivory by specialist and generalist insects (e.g. Agrawal, 1999, 2000a; Jones et al., 2006; Schranz et al., 2009). P. rapae is able to detoxify glucosinolates whereas T. ni is not, which affects the feeding behavior of the herbivores and the pattern of plant damage caused by each type of herbivore (see Notes S1 and Fig. S2). Second-instar T. ni larvae were ordered from Benzon Research Inc. (Carlisle, PA, USA) and fed on a artificial diet. Second-instar P. rapae larvae were obtained from a colony maintained in the laboratory on fresh Raphanus sativa leaves, originating from eggs provided by Carolina Biological Supply (Burlington, NC, USA). In both of the insect treatments, a single larva without any previous starvation period was placed on top of each plant. To guarantee a single insect on each plant, each plant-larva pair was enclosed using a cylindrical tube (5 cm diameter wide × 14 cm high) made of acetate (3M®) with both ends open. One end was inserted into the soil and the other was covered by loose-weave fabric. Larvae were removed from the plants once 33% of leaf area was consumed (after 24–56 h and 24–88 h, for specialist and generalist insects respectively). Size of treated plants (estimated from the plant basal diameter) ranged between 3.8–11.4 cm. Plants were checked for damage 24 h after the infestation, and then every 8 h. In every census, we recorded both the proportion of leaves with herbivore damage and estimated the percentage of tissue removed per leaf (taken by the same person and ranging from 1 to 100%, see Schranz et al., 2009 for a similar procedure) to calculate the percentage of plant damage. After 72 h, the majority of the plants (368 plants, 87.7 %) in both insect treatments had the target level of damage, while 72 plants (12.3 %) did not reach the level of plant damage desired or had excess damage. These plants were not included in the statistical analysis. More details on the feeding behavior of each insect species and the way that insects damaged the plants are given in Notes S1.

Like most perennial species, Boechera requires a cold vernalization period to induce flowering and seed production. For this reason, 1 wk after the herbivory treatments we moved the plants to a cold room (4°C, 16 h light and 8 h dark) for 6 wk, in order to initiate flowering and reproduction. This laboratory treatment provides an effective simulation of ‘winter’ vernalization because plants perceive vernalization cues only when temperatures are above freezing, rather than the long periods of below-freezing temperatures that occur in the wild. Subsequently, plants were moved back to the glasshouse (15.6°C–21°C, 16 h light and 8 h dark) until the end of the experiment (in May 2008).

Reproductive measurements

For each plant, we recorded both the flowering time (the number of days from germination until the opening of the first flower) and several correlates of maternal fitness: total number of flowers, seed set (total number of seeds/total number of flowers), and reproductive biomass [the weight of one individual seed randomly chosen (fresh weight using a Mettler Toledo ® xs105 precision scale) multiplied by the total number of seeds]. B. stricta is self-compatible and highly inbred (Song et al., 2006), thus, differences in fitness are unlikely to reflect inbreeding depression.

Analysis of constitutive and induced glucosinolates

Concurrent with the tolerance experiment, we grew 440 additional plants from each of the same 10 genotypes under the same conditions for analysis of constitutive and induced glucosinolates. Experimental procedure and methods for glucosinolate extraction, isolation, purification and quantification follow our previous methods (Schranz et al., 2009) and are given in Notes S2

Statistical analyses

To analyze the effect of herbivory on multiple fitness components, we conducted both multivariate analyses and general linear mixed models with maximum likelihood estimates, using JMP (ver. 7.0.1., SAS Institute Inc., 2007). Since fitness components were correlated (Table S2), we first performed a MANOVA to test the effects of treatment, genotype and their interaction on overall fitness. A significant interaction between genotype and treatment shows the existence of genetic variation in tolerance (i.e., difference in fitness between the damage treatments and the undamaged control, see below) for overall plant fitness. Second, we conducted a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to obtain independent factors (after varimax normalized rotation) accounting for plant fitness traits. Factor scores significantly correlated with fitness were included as dependent variables in separate mixed models fitted to test the fixed effects of treatment, genotype and their interaction. We included plant size as a covariate and block as a random effect in these models. The interaction between plant size and genotype was non-significant (not shown) and was removed from the models. Reproductive values were log-transformed to improve normality and homoscedasticity.

Tolerance was estimated for each genotype and fitness component (i.e., principal component) as the difference in fitness between the damage treatments (either specialist herbivore, generalist herbivore or clipping) and the undamaged control (Strauss & Agrawal, 1999). Higher and positive values depict greater tolerance to damage than smaller or negative values. Damage levels and fitness components were on the same multiplicative scale (Wise & Carr, 2008). For each of the fitness components, genetic variation in tolerance was inferred from the significance of genotype by treatment interaction term in the linear mixed models described above. When a significant interaction between genotype and herbivore treatment was detected, we carried out tests of simple main effects using the SLICE option in JMP, which allows the effects of a given factor to be explored at each level of the other factors (Schabenberger et al., 2000). In the context of this study, this test allowed us to determine, for each genotype, what type of herbivore damage had a significant effect on fitness components.

To analyze whether tolerance to damage is affected by the type of glucosinolate profile we grouped the 10 genotypes in two categories: methionine-derived glucosinolates or BCAA-derived glucosinolates (see Table S1). Differences in tolerance means between these two groups were estimated using a non-parametric Kruskall–Wallis test with genotype as the unit of replication. In addition, to test the effect of the chemical background of the genotypes and herbivory on plant fecundity, for each fitness component, we fitted a general linear mixed model including treatment, the glucosinolate group (BCAA-derived vs methionine-derived) and their interaction as fixed factors, and block as a random factor. Since plants with a high proportion of BCAA-derived glucosinolates were significantly bigger (basal radius mean ± 1SE, BCAA-derived: 73.75 ± 1.98 mm, methionine-derived: 70.77 ± 1.89 mm; ANOVA: F1,406 = 2.45, P = 0.015), plant size was included as a covariate.

When significant genetic variation was found, we estimated the allocation costs of tolerance to damage. We analyzed the genetic correlation among genotype fitness means (in all the cases means are model adjusted LS-MEANS) for damaged and undamaged plants using correlation analyses in JMP 7.0.1 (SAS Institute Inc., 2007). A significant negative correlation between fitness of damaged and undamaged plants indicates a cost of tolerance (Strauss & Agrawal, 1999). In addition, we analyzed the genetic correlation among genotype mean tolerance in each of the herbivory damage treatments (i.e., tolerance to generalist vs tolerance to specialist damage; tolerance to generalist vs tolerance to clipping damage; and tolerance to specialist vs tolerance to clipping damage). Similarly, a significant negative correlation between tolerance to different types of damage would indicate a cost of tolerance.

Because all damaged plants had equal percentage of leaf area removed (see above), we could not directly infer heritable variation for resistance among our plant genotypes. However, given the defensive role that glucosinolates often play (at least against generalist herbivores, e.g. Hopkins et al., 2009), for each type of damage, we also analyzed tolerance-chemical defense trade-offs by regressing the genotype tolerance means obtained for each type of damage and the genotype total glucosinolate concentration means both at constitutive and induced level. A significant negative genetic relation between tolerance and the concentration of defensive metabolite indicates the presence of an allocation tradeoff between tolerance and resistance (Leimu & Koricheva, 2006). Because the total concentration of constitutive and induced glucosinolates was affected significantly by the chemical background of the genotypes (see the Results section) we explored the covariance between tolerance and resistance through both groups. Because our data did not satisfy the assumptions of ANOVA analyses (e.g., small sample size, non-normal errors, and presence of outliers), we used a robust analysis of covariance based on M estimation (Chen, 2002). Robust ANCOVA analyses were then performed using the procedure ROBUSTREG procedure in SAS ver. 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., 2008). In these analyses, genotypic mean tolerance was always the dependent variables, and the glucosinolate group was the grouping factor. We included as covariates the mean genotype total glucosinolate concentration either in the undamaged treatment (constitutive resistance) or the difference in the mean total glucosinolate concentration after 24 h of herbivory between damaged and undamaged plants (induced resistance). Statistical significance of ANCOVA analyses came from -Robust Wald’s linear test (Chen, 2002).

Results

Effects of herbivory treatments on overall plant fitness

A MANOVA conducted on all fitness components did not show a significant main effect of herbivory treatment (Table 1). However, there were significant effects of genotype on overall fitness, and the genotype by herbivory interaction (Table 1), which suggests that the magnitude and/or sign of the herbivory treatment on fitness depended on genotype. Analyses conducted separately on each of the fitness components (see below) revealed that herbivory affected the early fitness components, although its effect was dependent on genotype. Block and plant size also influenced plant fitness (Table 1).

Table 1.

MANOVA to test the effects of genotype, herbivory treatment and their interaction on four fitness components of Boechera stricta

| Source | Wilks’ λ | df | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | 0.387 | 36, 1227 | 35.29 | <0.0001 |

| Herbivory | 0.945 | 12, 865 | 1.54 | 0.1050 |

| Genotype × herbivory | 0.654 | 108, 1300 | 1.36 | 0.0100 |

| Plant size | - | 4, 327 | 8.22 | <0.0001 |

| Block | 0.51 | 40, 1242 | 6.13 | <0.0001 |

Significant values (P < 0.05) are in bold.

Fitness components and genetic variation in tolerance

Taken together, three independent factors accounted for 98.6 % of the variation in reproductive traits in our PCA (Table S3). The first factor (PC1) depicts late plant fecundity because it is related to seed set and reproductive biomass (Table S3). The second factor (PC2) indicates early fecundity, and is closely related to the numbers of flowers (Table S3), providing the opportunity for reproductive fitness via male function. Both factors are related to variation in fecundity, where higher and positive values indicate higher levels of seed and flower production. The third factor (PC3) depicts flowering time variation (Table S3). In this case, negative and smaller values denote early flowering times, while positive and higher values depict late flowering times.

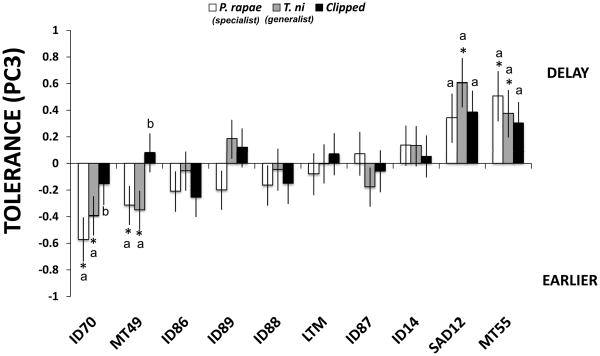

Herbivory, as a main effect, did not influence the PC3 fitness component related to flowering time PC3 (Table 2). However, there was a significant effect of genotype, and the genotype by herbivory treatment interaction on the PC3 fitness component (Table 2). This result suggests that the consequences of different types of herbivory on the PC3 fitness component are genotype-dependent, and that there is significant genetic variation in tolerance when fitness components correlated with flowering time are considered (Fig. 1). Tests of main effects showed that 6 out of 10 genotypes were not affected by the herbivory treatment (Table 3). However, ID70 and MT49 genotypes flowered faster in response to insect damage, while MT55 and SAD12 genotypes flowered more slowly in response to damage (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Summary results of the general linear mixed model testing the effects of herbivory treatment, genotype and their interaction on three principal components summarizing fitness–related variation in Boechera stricta

| Fixed effects | df | PC1 |

df | PC2 |

df | PC3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P | F | P | F | P | ||||

| Genotype | 9, 333 | 11.24 | <0.0001 | 9, 332 | 14.52 | <0.0001 | 9, 330 | 171.97 | <0.0001 |

| Herbivory | 3, 331 | 2.38 | 0.069 | 3, 331 | 2.36 | 0.071 | 3, 330 | 0.81 | 0.489 |

| Genotype × Herbivory | 27, 331 | 1.17 | 0.257 | 27, 331 | 1.55 | 0.042 | 27, 330 | 1.62 | 0.027 |

Significant P-values (P < 0.05) are in bold. PC1 is a late fitness component, PC2 is an early fitness component and PC3 is an indicator of flowering time (see text for details).

Fig. 1.

Variation in tolerance, estimated as the average (adjusted LS-MEANS ± 1 SE) difference in fitness (fitness component PC3, correlated with flowering time) between the damaged treatments and the undamaged controls (the zero line in the graph), for three types of herbivore damage among 10 different genotypes of Boechera stricta. Significant differences (P < 0.05) from undamaged control plants are depicted with an asterisk based on tests of simple main effects (see the Materials and Methods section for details). For each genotype, letters above the bars not identified by the same letter are significantly different (P < 0.05). Treatments: open bars, Pieris rapae (specialist); gray bars, Trichoplusia ni (generalist); black bars, clipped.

Table 3.

Tests of simple main effects (interaction slices) for the effect of herbivory treatment on fitness components correlated with early fitness/flower number (PC2) and flowering time (PC3) for each Boechera stricta genotype

| PC2 | PC3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Genotype | df | F | P | F | P |

| Herbivory | ID14-76A | 3, 330 | 2.90 | 0.035 | 0.26 | 0.85 |

| Herbivory | ID70-10A | 3, 330 | 3.88 | 0.009 | 3.57 | 0.014 |

| Herbivory | ID86-38A | 3, 330 | 0.09 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.39 |

| Herbivory | ID87-31A | 3, 330 | 0.58 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.58 |

| Herbivory | ID88-2A | 3, 330 | 1.55 | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.75 |

| Herbivory | ID89-5A | 3, 330 | 0.43 | 0.73 | 1.91 | 0.13 |

| Herbivory | LTM | 3, 330 | 0.23 | 0.87 | 0.21 | 0.89 |

| Herbivory | MT49-18B | 3, 330 | 0.48 | 0.69 | 3.19 | 0.023 |

| Herbivory | MT55-9B | 3, 330 | 5.57 | <0.0001 | 2.17 | 0.09** |

| Herbivory | SAD12 | 3, 330 | 0.28 | 0.84 | 2.54 | 0.05 |

Significant values (P < 0.05) are in bold.

Interaction with the ‘specialist’ and ‘generalist’ levels is significant at P < 0.05. Also see Fig. 2.

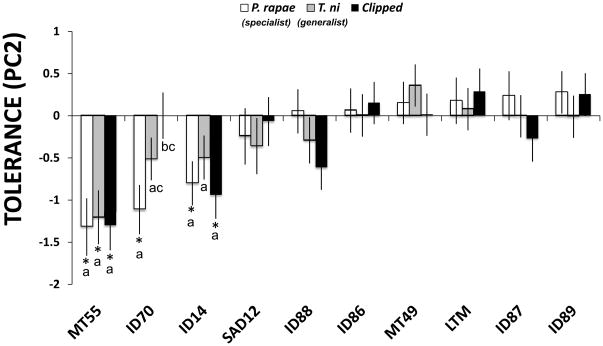

Early fitness component PC2 differed significantly among genotypes and showed only marginal effects of herbivory treatment; however, the genotype by herbivory treatment interaction was significant (Table 2). This indicates that: the fitness consequences of herbivore treatments depend on genotype; and there is significant genetic variation in tolerance for early fitness components (Fig. 2). Tests of main effects showed that most of the genotypes (7 out of 10) were able to compensate for herbivore damage, while 3 out of 10 did not (Table 3, Fig. 2). Thus, herbivore damage to the ID14, ID70 and MT55 genotypes had a negative impact on fitness (Fig. 2), although the magnitude and impact of each type of herbivore damage also varied among these genotypes (Fig. 2). For the remaining genotypes, the type of damage (i.e., treatment) had no detectable effect on PC2, an indicator of early fecundity and flower number.

Fig. 2.

Variation in tolerance, estimated as the average (adjusted LS-MEANS ± 1SE) difference in fitness (early fitness component PC2) between the damaged treatments and the undamaged controls (the zero line in the graph), for three types of herbivore damage among 10 different genotypes of Boechera stricta. Significant differences (P < 0.05) from undamaged control plants are depicted with an asterisk based on tests of simple main effects (see the Materials and Methods section for details). For each genotype, letters above the bars not identified by the same letter are significantly different (P < 0.05). Treatments: open bars, Pieris rapae (specialist); gray bars, Trichoplusia ni (generalist); black bars, clipped.

MT55 damaged plants had lower PC2 fitness compared with undamaged plants regardless of the type of damage (Fig. 2). For the ID70 genotype, only plants subjected to the specialist treatment had significantly reduced fitness relative to undamaged controls. Furthermore, for the ID14 genotype, plants in both the insect specialist and generalist treatments had significant lower fitness than undamaged control plants. Finally, plant size had a significant positive effect on fitness component PC2 (F= 31.96, df = 1.323, P < 0.0001; 0.022 ± 0.004, estimate ± 1 SE value).

The late fitness component PC1 (which is correlated with seed production) was significantly affected by genotype and, marginally, by the herbivory treatment (Table 2). Thus, plants in the manual clipping treatment had lower fitness (PC1 LSMEANS ± 1SE: −0.16 ± 0.11) than undamaged control plants (0.07 ± 0.11; contrast test : F1,331 =3,59, P = 0.059), or than plants subjected to the insect specialist treatment (0.17± 0.12, contrast test : F1,332 = 6,62, P = 0.01), but not significantly different than plants in the generalist treatment (0.013 ± 0.11; contrast test: F1,331 =1, 9, P = 0.16). Among genotypes, PC1 values ranged between 0.57 ± 0.18 for genotype MT55 to −0.77 ± 0.16 for genotype ID70. The genotype by herbivory interaction was not significant (Table 2), indicating that the effect of the type of herbivory damage on the late fitness component PC1 was constant for all the genotypes. Further, this nonsignificant interaction term also indicates that there is no detectable genetic variation in tolerance to damage when late fitness components are considered.

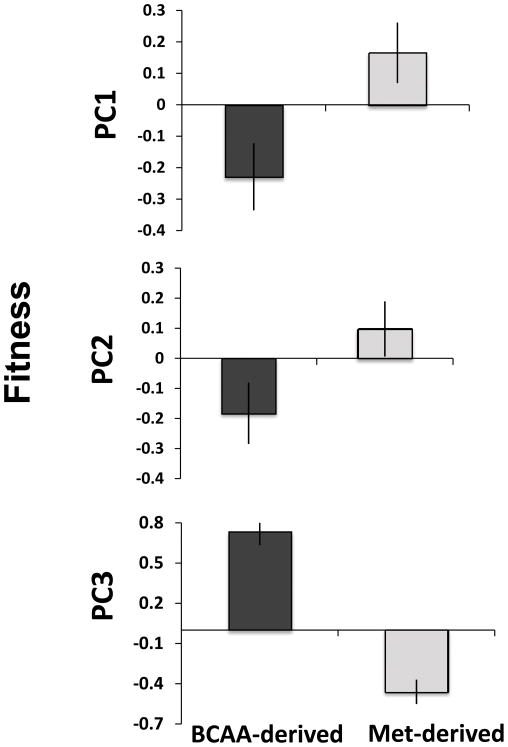

Effect of glucosinolate polymorphism on tolerance to damage and plant fecundity

The type of glucosinolate profile was unrelated to tolerance to damage for any of the fitness components or types of damage considered (see Table S4). However, variation in the constitutive glucosinolate profile was associated with differences in all plant fitness components, irrespective of herbivory treatment, as indicated by the non-significant interaction between glucosinolate type and herbivory treatment (Table 4). Thus, plants with high proportions of BCAA-derived glucosinolates had significantly lower fitness than plants with methionine-derived glucosinolates (Fig. 3). Similarly, plants with a high proportion of BCAA-derived glucosinolates flowered later than plants with methionine-derived glucosinolates (Fig. 3). Finally, there was a significant positive effect of plant size on fitness components PC2 and PC3 (0.022 ± 0.0031, 0.0027 ± 0.004; estimate ± 1 SE values for PC2 and PC3 respectively, see Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of general linear mixed models analyzing the effect of the glucosinolate-profile and herbivory treatment on three plant fitness components of Boechera stricta

| Fitness components | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | ||||||

| df | F | P | df | F | P | df | F | P | |

| Herbivory | 3, 363 | 2.40 | 0.070 | 3, 363 | 1.58 | 0.19 | 3, 362 | 0.48 | 0.69 |

| Glucosinolate profile (GS) | 1, 363 | 15.28 | <0.0001 | 1, 363 | 8.47 | 0.004 | 1, 362 | 248.23 | <0.0001 |

| Herbivory × GS |

3, 363 | 1.69 | 0.17 | 3, 363 | 1.03 | 0.38 | 3, 362 | 0.23 | 0.88 |

| Covariate |

|||||||||

| Plant size | 1, 349 | 1.35 | 0.25 | 1, 348 | 49.27 | <0.0001 | 1, 369 | 49.75 | <0.0001 |

Significant P-values (P < 0.05) are in bold. PC1 is a late fitness component, PC2 is an early fitness component and PC3 depicts flowering time. See text for details.

Fig. 3.

Variation in plant fitness components among Boechera stricta plants with contrasting structural glucosinolate profile: high proportion of branched-chain amino acids (BCAA)-derived glucosinolates (dark gray bars) vs low proportion of BCAA-derived glucosinolates (light gray bars). (PC1 is an indicator of late fitness/seed production, PC2 is correlated with flowering number/early fitness, and PC3 is associated with variation in flowering time). Values are adjusted LS-MEANS ± 1 SE.

Allocation costs of tolerance

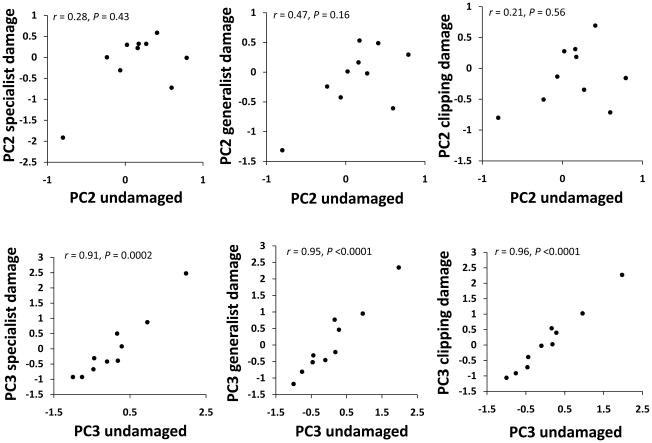

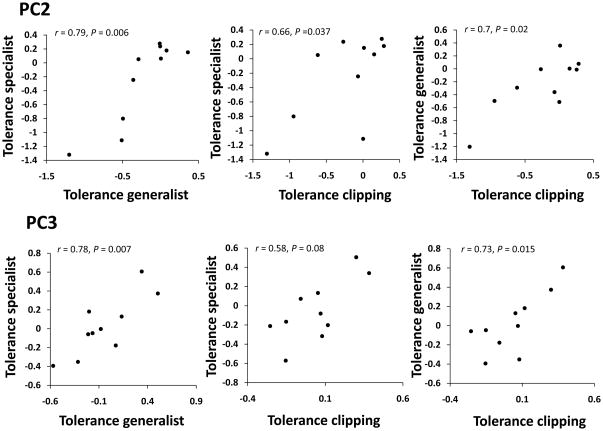

Because significant genetic variation was only detected for the PC2 and PC3 fitness components, we analyzed costs of tolerance only for these traits. PC2 genetic means on damaged and undamaged plants were not significantly correlated (Fig. 4). However, genotype PC3 fitness means for damaged and undamaged plants showed a significant positive correlation (Fig. 4), which suggests that genotypes with late flowering times in the undamaged treatment also showed late times to flower in all the damage treatments (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Genetic correlations between mean fitness components correlated to early fecundity PC2 (above) and flowering time PC3 (below) between damaged Boechera stricta plants and their undamaged controls. Values in the figures are the genetic correlation coefficients. A significant negative correlation between fitness of damaged and undamaged plants would indicate a cost of tolerance. However, no evidence for such costs is detectable.

For both fitness components PC2 and PC3, genotypic mean tolerance to damage in each of the treatments were positive and significantly correlated in most of the cases (Fig. 5), which suggests that plants of a given genotype show similar levels of tolerance to different herbivore species.

Fig. 5.

Genetic correlations for tolerance to different damage treatments. For each Boechera stricta genotype (each point in the graphs), tolerance is estimated as the average (adjusted LS-MEANS) difference in fitness between the damaged treatments and the undamaged controls. Each panel indicates the genetic correlation and its statistical significance. Early fitness component PC2 is in the top row, and flowering time fitness component PC3 is below. A significant negative correlation between tolerance of different type of damage would indicate a cost of tolerance. However, no evidence for such costs is detectable.

Trade-offs between tolerance and chemical defenses

The constitutive concentration of leaf glucosinolates varied significantly among the 10 genotypes (ANOVA result for genotype factor: F9,82 = 10.61, P < 0.0001), and also between plants with different chemical profiles (ANOVA: F1,90 = 5.33, P = 0.023, Fig S4). However, overall, we did not detect a significant genetic correlation between the total concentration of constitutive glucosinolates and tolerance to damage (Table 5). We detected a significant effect, dependent on the glucosinolate group, of the constitutive glucosinolate concentration on tolerance (PC2) to clipping (Table 5). Tolerance and defensive metabolites concentration were significantly and positively genetically correlated in plants with methionine-derived glucosinolates (pair wise correlation coefficient: n = 6, r = 0.93, P = 0.007, Fig. S5), but not in plants with BCAA-derived glucosinolates (n = 4, r = 0.54, P = 0.45). These results provide no evidence for a trade-off between tolerance and resistance for each type of damage.

Table 5.

Results of the robust ANCOVA analyzing trade-offs between constitutive resistance (genotype-mean glucosinolate concentration, GS0) and tolerance to three types of herbivory damage across 10 Boechera stricta genotypes with two contrasting constitutive glucosinolate profile (BCAA-derived glucosinolates vs met-derived glucosinolates)

| Tolerance PC2 | Tolerance PC3 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects | Specialist | Generalist | Clipping | Specialist | Generalist | Clipping | |||||||||||||

| df | P | P | P | P | P | P | |||||||||||||

| [GS0] | 1, 10 | 0.21 | 0.64 | 0.365 | 0.544 | 2.84 | 0.09 | 0.275 | 0.6 | 0.291 | 0.589 | 0.06 | 0.8 | ||||||

| GS-profile | 1, 10 | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.013 | 0.907 | 33.61 | <0.0001 | 1.181 | 0.177 | 2.161 | 0.141 | 1.17 | 0.278 | ||||||

| GS-profile × [GS0] | 1, 10 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.045 | 0.831 | 23.83 | <0.0001 | 1.31 | 0.252 | 0.937 | 0.332 | 0.547 | 0.459 | ||||||

Significant P-values (P < 0.05) are in bold.

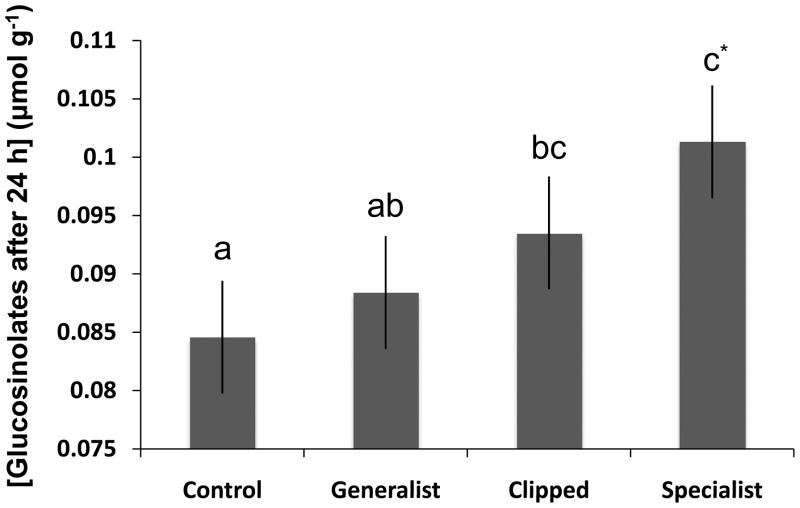

The total concentration of leaf constitutive glucosinolates after 24 h of damage varied significantly among genotypes and herbivory treatments (Figs 6, S6, Table S5), but genetic variation in glucosinolate induction was non-significant (the interaction of genotype and treatment was not significant, Table S5). Induction of glucosinolates was significant related to the genotypic chemical profile in the specialist herbivory treatment only (Kruskall-Wallis ANOVA: df = 1,10, χ2 = 3.68, P = 0.05; P > 0.05 for the rest of the treatments, see also Fig. S7). Overall, glucosinolate induction did not affect tolerance to herbivore damage (Table S6). Only in one case did glucosinolate induction significantly affect tolerance (PC3 component) to specialist damage (Table S6), but this correlation was positive (pair wise correlation: n = 10, r = 0.65, P = 0.043).

Fig. 6.

Total Boechera stricta leaf glucosinolate concentration (adjusted LS-MEANS ± 1 SE) after 24 h of damage among four different herbivory treatments. Different letters depict significant differences (P < 0.05). *, Marginally significant (P = 0.07).

Discussion

Our experiments show significant genetic variation for tolerance to different types of herbivore damage among genotypes of B. stricta, a wild relative of Arabidopsis. We found genetic heterogeneity in flowering responses to damage by different herbivore treatments. Different types of damage had heterogeneous effects on flowering time (PC3) and the number of flowers (PC2), and these responses varied among genotypes. By contrast, the influence of damage treatments on later fitness components (PC1) was genetically homogeneous. Variation in the structural glucosinolate profile did not influence tolerance to damage, although it is associated with aspects of plant fitness. Plants with a high proportion of BCAA-derived foliar glucosinolates had significantly later flowering times and lower fitness than plants containing methionine-derived glucosinolates. We did not find a significant negative genetic correlation between tolerance and fitness in the absence of herbivores, or between tolerance to different types of herbivore damage. Finally, we did not detect any trade-off between tolerance and resistance that might explain the genetic variation in tolerance among these genotypes.

Although this study does not include native herbivores of B. stricta, results from our experiment are relevant because we analyzed the effect on tolerance to damage by different types of herbivory, and also examined genotypes with contrasting constitutive chemical background, which are under-studied aspects in the context of plant tolerance to herbivore damage.

Genetic variation for tolerance and effects of types of herbivory on plant fitness

Effects of herbivory on plant fitness range from mortality to overcompensation (reviewed by Agrawal, 2000b; Hawkes & Sullivan, 2001; Wise & Abrahamson, 2007). Within host species, responses to herbivory are determined by the degree of genetic variation, environmental effects, and their complex interactions (Strauss & Agrawal, 1999; Fornoni et al., 2003; Nuñez-Farfán et al., 2007). Our results support this view. Leaf herbivory affected fitness-related traits in B. stricta, although both the magnitude and the direction of these effects varied among genotypes, as well as among different fitness components and types of herbivore damage. Despite progress in this field, analyses of tolerance in response to different insects and modes of herbivory are still scarce (Agrawal et al., 1999; Jones et al., 2006).

The type of herbivory and the distribution of damage within the plant are believed to influence tolerance and its expression across genotypes (Rosenthal & Kotanen, 1994; Agrawal et al., 1999). This view is grounded in two well-known facts: different herbivores feed on different plant tissues and structures, which may affect plant performance differently according to the fitness value of the tissue (e.g., Karban & Strauss, 1993; Zangerl & Rutledge, 1996; Anderson & Agrell, 2005, Barto & Cipollini, 2005); and induced resistance in plants is herbivore-specific, as are the consequences for plant fitness (Agrawal, 1998, 1999, 2000a). In our experiment, the amount of damage imposed was constant across plant genotypes and herbivory treatments, yet the distribution of this damage within the plant differed among treatments. P. rapae larvae fed mostly on the upper parts of the plant (primarily on young and recently-mature upper leaves), while T. ni larvae fed on lower leaves and avoided feeding on the apical part of the plant (Fig. S3). By contrast, in the clipping treatment the damage was homogeneously distributed within the plant (see Methods). In addition, we found that induced resistance varied significantly among herbivory treatments, and this variation was homogeneous among genotypes (Figs 6, S6 and Table S5). In particular, we found that induced glucosinolate responses were higher in plants attacked by P. rapae larvae than in other herbivory treatments. However, although the herbivory treatments differed consistently across genotypes in terms of the location of the damage and the pattern of induced response, the effect of the type of damage on tolerance was heterogeneous among genotypes (Table 2). MANOVA detected significant genetic variation on overall fitness traits, with significant responses to herbivory at earlier stages of plant reproduction (i.e., on flowering time and the total number of flowers). Two of the genotypes flowered earlier when exposed to insect damage, while insect herbivory caused two other genotypes to delay flowering in comparison to their undamaged controls (Fig. 1). Similarly, herbivory had a significant impact on the total number of flowers produced per plant, yet the magnitude of these effects were genotype-specific and dependent on type of damage. When significant (in 3 out 10 genotypes), herbivory always had a negative effect, resulting in fewer flowers than the undamaged controls.

The marginally significant effect of the type of damage on later fitness components (PC1) is also noticeable, which suggests that plants damaged by the specialist insect tended to overcompensate, while clipped plants tended to undercompensate, and this was constant for all the genotypes (as indicated by the nonsignificance of the herbivory by genotype interaction for the component PC1, see Table 2). Overcompensation following P. rapae damage has been shown previously in the Brassicaceae family, is related to the induced response to such damage, and is thought to be adaptive (i.e., plants have enhanced fitness when induced by specialist insects, and lower fitness when undamaged or clipped, see Agrawal, 1998, 1999). Similarly, overcompensation is common when plants are exposed to apical damage (Wise and Abrahamson, 2008, and references therein), which was the main type of damage inflicted by P. rapae larvae in our experiment.

Our results show that although B. stricta can compensate for herbivory (particularly damage caused by the specialist insect), herbivory still reduced overall flower production and altered flowering for some genotypes. The mechanisms involved in compensation for herbivory are beyond the scope of this paper, but differential allocation of resources to other plant tissues, variation in flowering time, and changes in growth rates are known mechanisms (Rosenthal & Kotanen, 1994; Agrawal et al., 1999; see also Pilson &Decker, 2002) which might explain the observed variation in tolerance to herbivory among B. stricta genotypes.

Clearly, the expression of tolerance may be influenced by other ecological factors not considered in our study. For example, the levels of inter-specific competition experienced in the field (Jones et al., 2006) and the timing of damage may be important factors determining B. stricta’s tolerance to herbivory. We damaged the plants after 6 wk of vegetative growth, which may correspond to the mid-summer period when most herbivores are actively feeding on B. stricta plants in natural populations (Mitchell-Olds, pers. obs.). However, later herbivory still is possible if an herbivore outbreak occurs late in the season, or if plant phenology is altered by local climatic conditions. The later in the season the damage occurs, the shorter the compensation period will be, hence damage also may affect late fecundity (see Maschinski & Whitham, 1989; Tiffin, 2002).

Glucosinolate polymorphism and plant fecundity

A first step to understanding the significance underlying polymorphism of plant chemical defenses is determining whether such variation has ecological implications. Previously in our system, we found that chemical polymorphism affected plant resistance to generalist herbivores (Schranz et al., 2009). By contrast, here we have shown that tolerance to herbivory damage does not depend on the structural glucosinolate profile. In the current study the chemical polymorphism was associated with plant fitness regardless of herbivore damage. Thus, plants with a high proportion of BCAA-derived glucosinolates in their leaves flowered significantly later and had significantly lower fitness than plants containing mainly methionine-derived glucosinolates (Fig. 3). Previous studies have shown negative effects of chemical defenses on plant fecundity in several systems, suggesting the existence of direct allocation costs of resistance (Strauss et al., 2002). However, to our knowledge, no work has described the existence of direct costs of resistance derived from natural and discrete variation in the structural chemical profile within plant species. Although this effect on fitness also might reflect other genotypic effects (i.e., linkage disequilibrium), several arguments suggest that discrete variation in the chemical profile of B. stricta genotypes might truly affect other components of plant fitness. First, among plant species, the magnitude and significance of constitutive resistance costs at the quantitative level vary among types of defensive compounds, because distinct defensive compounds have different biosynthetic costs (Koricheva, 2002 and references therein). Interestingly, in our system we also found a significant negative genetic correlation between the total concentration of glucosinolates and fitness components among genotypes with different chemical profiles, suggesting a direct cost of resistance. Although the total concentration of glucosinolates was negatively correlated with early plant fecundity (PC2), it was strongly and negatively correlated with late plant fecundity (PC1) in genotypes with a high proportion of BCAA-derived glucosinolates (Table S7, Fig. S8).

Second, QTL mapping analyses recently conducted on a B. stricta mapping population have revealed a significant QTL predicting survival and reproduction in the BCMA chromosomal region, which controls synthesis of BCAA- vs methionine-derived glucosinolates in B. stricta (Schranz et al., 2009; Anderson & Mitchell-Olds, unpublished data). Future work using transgenic lines can clarify whether BCMA genes have significant effects on plant fitness traits.

One limitation from our study, however, is that fitness estimates were obtained under glasshouse conditions, which may differ from fitness measurements in natural populations, especially if variation in the chemical profile in B. stricta is the result of local adaptation or another form of balancing selection. This latter possibility is currently being examined in natural populations of B. stricta.

Costs of tolerance

Plant defense theory proposes that allocation costs maintain genetic variation for tolerance, preventing fixation of alleles for maximal tolerance among individuals within and among populations (Strauss & Agrawal, 1999; Strauss et al., 2002). However, empirical evidence for such costs is limited, despite multiple attempts to address this question (reviewed by Koricheva, 2002; Leimu & Koricheva, 2006). Here, we investigated two different types of allocation costs of tolerance. However, we did not find a significant negative genetic correlation between tolerance and fitness in the absence of herbivores, or between tolerance to different types of herbivore damage. Indeed, tolerance to different types of damage showed significant positive genetic correlations. These results indicate that: allocation costs do not constrain the evolution of tolerance, hence genetic variation for tolerance may be maintained by other ecological or evolutionary forces; and genotypes showed positive genetic correlations in their tolerance to different herbivory treatments. This result is concordant with the few existing studies examining tolerance to different enemies, which found no evidence for tradeoffs between tolerance to different types of damage (Tiffin & Rausher, 1999; Pilson 2000). These results suggest that evolution of tolerance to multiple herbivores may not account for the existence of intermediate levels of tolerance to leaf damage on plants (Nuñez-Farfán et al., 2007).

Additionally, we did not find any trade-off between tolerance and investment in defensive metabolites, as suggested by the lack of a significant negative genetic relationship between constitutive or induced glucosinolates and tolerance to different types of damage. On the contrary, we found that the concentration of constitutive glucosinolates and tolerance to clipping were significantly and positively correlated, at least, in terms of the production of flowers. This suggests that tolerant plants may be also more resistant to some types of damage. This was especially true for genotypes with methionine-derived glucosinolates (Table 5, Fig. S5). Thus, the evolution of resistance and tolerance in B. stricta does not seem be limited by genetic constraints, and for genotypes with methionine-derived glucosinolates, resistance and tolerance will evolve jointly (i.e., allocating resources simultaneously to both tolerance and resistance, Nuñez-Farfán et al., 2007).

Although we did not detect any allocation cost of tolerance in our study, there is growing evidence that the existence of allocation costs are dependent on complex interactions with the biotic and/or abiotic environment (Koricheva, 2002; Siemens et al., 2009), which we did not manipulate in our glasshouse experiment. Therefore, future work will need to take into account environmental variation that exists under natural conditions.

In short, our study has shown that structural variations in the chemical profile of plant defenses did not influence the ability of B. stricta to compensate for different types of herbivory damage, although this chemical variation is correlated with plant fitness in our sample. In addition, our study points out the importance of considering jointly both intrinsic plant factors and extrinsic ecological factors to understand the evolution of plant tolerance to damage and its costs.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1 Distribution map of B. stricta populations and geographical origin of the genotypes selected for the tolerance experiment.

Fig. S2 Schematic representation of Boechera stricta showing the three different ontogenetic stages of leaf growth.

Fig. S3 Average percentage of leaves harmed and average damage per leaf caused by the herbivores among three different ontogenetic levels within 215 B. stricta plants used in the insect treatments in the tolerance experiment.

Fig. S4 Variation in the total leaf glucosinolate concentration among 90 B. stricta plants with two contrasting structural glucosinolate profiles.

Fig. S5 Genetic correlations between the early fecundity fitness component and the average total concentration of leaf glucosinolates of B. stricta plants with met-derived glucosinolates.

Fig. S6 Genetic correlations between the mean total leaf glucosinolate concentration of undamaged controls plants and the mean total leaf glucosinolate concentration after 24 h of damage treatment to three types of herbivory.

Fig. S7 Variation in the total leaf glucosinolate concentration after 24 h of damage caused by the specialist lepidopteran P. rapae among B. stricta plants with two contrasting structural glucosinolate profile: plants with a high proportion of BCAA-derived glucosinolates vs plants with Met-derived glucosinolates.

Fig. S8 Genetic correlations between the average total concentration of leaf glucosinolates and the late fitness component, shown separately for genotypes with predominantly BCAA- and met-derived glucosinolates.

Notes S1 Insect feeding behavior and intra-plant variation in plant damage.

Notes S2 Constitutive and induced glucosinolates analysis and methods.

Table S1 Location and geographical origin of the 10 genotypes used in the tolerance to damage experiment

Table S2 Pairwise correlation coefficients among the four fitness components considered in this study

Table S3 Principal components analysis conducted on four plant reproductive parameters of 368 B. stricta plants under four different herbivory treatments

Table S4 Results of Kruskall–Wallis tests conducted to analyze differences in tolerance to three types of herbivory damage between B. stricta plants with two contrasting glucosinolate profiles

Table S5 Summary results of the general linear mixed model testing the effects of herbivory treatment, genotype and their interaction on the total leaf glucosinolate concentration after 24 h of herbivory damage

Table S6 Results of the Robust ANCOVA analyzing trade-offs between induced resistance and tolerance to three types of herbivory damage across 10 B. stricta genotypes with two contrasting constitutive glucosinolate types

Table S7 Results of the Robust ANCOVA analyzing direct cost of resistance (for B. stricta plants with two contrasting constitutive glucosinolate types

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

Acknowledgments

We thank three anonymous reviewers and J. Anderson for helpful comments on the manuscript, and K. Springer, S. Hurst, C. Weiss-Lehman, J. Lutkenhaus and the Duke Glasshouses staff for technical assistance. A.J.M. was funded by Spanish Ministry of Education and Science, grant EX-2006-0652, and Duke University. T.M.O. was funded by the National Science Foundation (award EF-0723447) and the National Institutes of Health (award R01 GM086496).

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- Anderson P, Agrell J. Within-plant variation in induced defence in developing leaves of cotton plants. Oecologia. 2005;144:427–434. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal AA. Induced responses to herbivory and increased plant performance. Science. 1998;279:1201–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal AA. Induced responses to herbivory in wild radish: Effects on several herbivores and plant fitness. Ecology. 1999;80:1713–1723. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal AA. Speci city of induced resistance in wild radish: Causes and consequences for two specialist and two generalist caterpillars. Oikos. 2000a;89:493–500. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal AA. Overcompensation of plants in response to herbivory and the byproduct benefits of mutualism. Trends in Plant Science. 2000b;5:310–313. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal AA, Fishbein M. Plant defense syndromes. Ecology. 2006;87:S132–S149. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[132:pds]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal AA, Strauss SY, Stout MJ. Costs of induced responses and tolerance to herbivory in male and female fitness components of wild radish. Evolution. 1999;53:1093–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb04524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barto KE, Cipollini DF. Testing the optimal defense theory and the growth-differentiation balance hypothesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Oecologia. 2005;146:169–178. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton KE. Phenotypic plasticity in seedling defense strategies: compensatory growth and chemical induction. Oikos. 2008;117:917–925. [Google Scholar]

- Boalt E, Lehtilä K. Tolerance to apical and foliar damage: costs and mechanisms in Raphanus raphanistrum. Oikos. 2007;116:2071–2081. [Google Scholar]

- Boege K, Dirzo R, Siemens D. Ontogenetic switches from plant resistance to tolerance: Minimizing costs with age? Ecology Letters. 2007;10:177–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. Robust Regression and Outlier Detection with the ROBUSTREG Procedure. Proceedings of the Twenty-seventh Annual SAS Users Group International Conference; Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fornoni J, Nuñez-Farfán J. Evolutionary ecology of Datura stramonium: genetic variation and costs for tolerance to defoliation. Evolution. 2000;54:789–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornoni J, Nuñez-Farfán J, Valverde PL. Evolutionary ecology of tolerance to herbivory: advances and perspectives. Comments on Theoretical Biology. 2003;8:643–663. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes CV, Sullivan JJ. The impact of herbivory on plants in different resource conditions: a meta-analysis. Ecology. 2001;82:2045–2058. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins RJ, van Dam NM, van Loon JJA. Role of glucosinolates in insect–plant relationships and multitrophic interactions. Annual Review of Entomology. 2009;54:57–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.54.110807.090623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle G, Simard G. Additive effects of genotype, nutrient availability and type of tissue damage on the compensatory response of Salix planifolia ssp. planifolia to simulated herbivory. Oecologia. 1996;107:373–378. doi: 10.1007/BF00328454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey C, Carr D, Eubanks M. Genetic variation and constraints on the evolution of defense against spittlebug (Philaenus spumarius) herbivory in Mimulus guttatus. Heredity. 2009;102:303–311. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2008.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T, Kulseth S, Mechtenberg K, Jorgenson C, Zehfus M, Brown P, Siemens D. Simultaneous evolution of competitiveness and defense: induced switching in Arabis drummondii. Plant Ecology. 2006;184:245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Karban R, Strauss S. Effects of herbivores on growth and reproduction of their perennial host, Erigeron glaucus. Ecology. 1993;74:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein DJ, Kroymann J, Brown P, Figuth A, Pedersen D, Gershenzon J, Mitchell-Olds T. Genetic control of natural varation in Arabidopsis glucosinolate accumulation. Plant Physiology. 2001;126:811–825. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koricheva J. Meta-analysis of sources of variation in fitness costs of plant antiherbivores defenses. Ecology. 2002;83:176–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lankau R. Specialist and generalist herbivores exert opposing selection on a chemical defense. New Phytologist. 2007;175:176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimu R, Koricheva J. A meta-analysis of tradeoffs between plant tolerance and resistance to herbivores: combining the evidence from ecological and agricultural studies. Oikos. 2006;112:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Løe G, Toräng P, Gaudeul M, Ågren J. Trichome production and spatiotemporal variation in herbivory in the perennial herb Arabidopsis lyrata. Oikos. 2007;116:134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Maschinski J, Whitham TG. The continuum of plant responses to herbivory: the influence of plant association, nutrient availability, and timing. American Naturalist. 1989;134:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen MD, Halkier BA. Metabolic engineering of valine- and isoleucine-derived glucosinolates in Arabidopsis expressing CYP79D2 from Cassava. Plant Physiology. 2003;131:773–779. doi: 10.1104/pp.013425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell-Olds T. Arabidopsis thaliana and its wild relatives: a model system for ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2001;16:693–700. [Google Scholar]

- Newton EL, Bullock JM, Hodgson DJ. Glucosinolate polymorphism in wild cabbage (Brassica oleracea) in uences the structure of herbivore communities. Oecologia. 2009;160:63–76. doi: 10.1007/s00442-009-1281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez-Farfán J, Fornoni J, Valverde PL. The evolution of resistance and tolerance to herbivores. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematic. 2007;38:541–566. [Google Scholar]

- Pilson D. The evolution of plant response to herbivory: simultaneously considering resistance and tolerance in Brassica rapa. Evolutionary Ecology. 2000;14:457–489. [Google Scholar]

- Pilson D, Decker KL. Compensation for herbivory in wild sunflower: response to simulated damage by the head-clipping weevil. Ecology. 2002;83:3097–3107. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal JP, Kotanen PM. Terrestrial plant tolerance to herbivory. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1994;9:145–148. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schabenberger O, Gregorie TG, Kong F. Collections of simple effects and their relationships to main effects and interactions in factorial. American Statistician. 2000;54:210–214. [Google Scholar]

- Schranz EM, Manzaneda AJ, Windsor AJ, Clauss MJ, Mitchell-Olds T. Ecological genomics of Boechera stricta: Identification of a QTL controlling the allocation of methionine- vs. branched chain amino acid-derived glucosinolates and levels of insect herbivory. Heredity. 2009;102:465–474. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemens DH, Haugen R, Matzner S, Vanasma N. Plant chemical defence allocation constrains evolution of local range. Molecular Ecology. 2009;18:4974–4983. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B-H, Clauss MJ, Pepper A, Mitchell-Olds T. Geographic patterns of microsatellite variation in Boechera stricta, a close relative of Arabidopsis. Molecular Ecology. 2006;15:357–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steven MT, Waller DM, Lindroth RL. Resistance and tolerance in Populus tremuloides: genetic variation, costs, and environmental dependency. Evolutionary Ecology. 2007;21:829–847. [Google Scholar]

- Stinchcombe JR. Fitness consequences of cotyledon and mature-leaf damage in the ivyleaf morning glory. Oecologia. 2002;131:220–226. doi: 10.1007/s00442-002-0871-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinchcombe JR, Rausher MD. The evolution of tolerance to deer herbivory: modifications caused by the abundance of insect herbivores. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 2002;269:1241–1246. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss SY, Agrawal AA. The ecology and evolution of plant tolerance to herbivory. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1999;14:179–185. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01576-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss SY, Irwin RE. Ecological and evolutionary consequences of multispecies plant–animal interactions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematic. 2004;35:435–466. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss S, Zangerl AR. Plant-insect interactions in terrestrial ecosystems. In: Herrera CM, Pellmyr O, editors. Plant–animal interactions. An evolutionary approach. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science; 2002. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss SY, Rudgers JA, Lau JA, Irwin RE. Direct and ecological costs of resistance to herbivory. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2002;17:278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss SY, Irwin RE, Lambrix VM. Optimal defence theory and ower petal colour predict variation in the secondary chemistry of wild radish. Journal of Ecology. 2004;92:132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Suwa T, Maherali H. Influence of nutrient availabilty on the mechanisms of tolerance to herbivory in an annual grass, Avena barbata (Poaceae) American Journal of Botany. 2008;95:434–440. doi: 10.3732/ajb.95.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JN. Variations in interspecific interactions. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematic. 1988;19:65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffin P. Competition and time of damage affect the pattern of selection acting on plant defense against herbivores. Ecology. 2002;83:1981–1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffin P, Rausher MD. Genetic constraints and selection acting on tolerance to herbivory in the common morning glory Ipomoea purpurea. American Naturalist. 1999;154:700–716. doi: 10.1086/303271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinig C, Stinchcombe JR, Schmitt J. Evolutionary genetics of resistance and tolerance to natural herbivory in Arabidopsis thaliana. Evolution. 2003;57:1270–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor AJ, Reichelt M, Figuth A, Svatoš A, Kroymann J, Kliebenstein DJ, Gershenzon J, Mitchell-Olds T. Geographic and evolutionary diversi cation of glucosinolates among near relatives of Arabidopsis thaliana (Brassicaceae) Phytochemistry. 2005;66:1321–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise MJ, Abrahamson WG. Effects of resource availability on tolerance of herbivory: a review and assessment of three opposing models. American Naturalist. 2007;169:443–454. doi: 10.1086/512044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise MJ, Carr D. On quantifying tolerance of herbivory for comparative analyses. Evolution. 2008;62:2429–2432. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise MJ, Abrahamson WG. Applying the limiting resource model to plant tolerance of apical meristem damage. American Naturalist. 2008;172:635–647. doi: 10.1086/591691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangerl AR, Rutledge CE. The probability of attack and patterns of constitutive and induced defense: a test of optimal defense theory. American Naturalist. 1996;147:599–608. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Distribution map of B. stricta populations and geographical origin of the genotypes selected for the tolerance experiment.

Fig. S2 Schematic representation of Boechera stricta showing the three different ontogenetic stages of leaf growth.

Fig. S3 Average percentage of leaves harmed and average damage per leaf caused by the herbivores among three different ontogenetic levels within 215 B. stricta plants used in the insect treatments in the tolerance experiment.

Fig. S4 Variation in the total leaf glucosinolate concentration among 90 B. stricta plants with two contrasting structural glucosinolate profiles.

Fig. S5 Genetic correlations between the early fecundity fitness component and the average total concentration of leaf glucosinolates of B. stricta plants with met-derived glucosinolates.

Fig. S6 Genetic correlations between the mean total leaf glucosinolate concentration of undamaged controls plants and the mean total leaf glucosinolate concentration after 24 h of damage treatment to three types of herbivory.

Fig. S7 Variation in the total leaf glucosinolate concentration after 24 h of damage caused by the specialist lepidopteran P. rapae among B. stricta plants with two contrasting structural glucosinolate profile: plants with a high proportion of BCAA-derived glucosinolates vs plants with Met-derived glucosinolates.

Fig. S8 Genetic correlations between the average total concentration of leaf glucosinolates and the late fitness component, shown separately for genotypes with predominantly BCAA- and met-derived glucosinolates.

Notes S1 Insect feeding behavior and intra-plant variation in plant damage.

Notes S2 Constitutive and induced glucosinolates analysis and methods.

Table S1 Location and geographical origin of the 10 genotypes used in the tolerance to damage experiment

Table S2 Pairwise correlation coefficients among the four fitness components considered in this study

Table S3 Principal components analysis conducted on four plant reproductive parameters of 368 B. stricta plants under four different herbivory treatments

Table S4 Results of Kruskall–Wallis tests conducted to analyze differences in tolerance to three types of herbivory damage between B. stricta plants with two contrasting glucosinolate profiles

Table S5 Summary results of the general linear mixed model testing the effects of herbivory treatment, genotype and their interaction on the total leaf glucosinolate concentration after 24 h of herbivory damage

Table S6 Results of the Robust ANCOVA analyzing trade-offs between induced resistance and tolerance to three types of herbivory damage across 10 B. stricta genotypes with two contrasting constitutive glucosinolate types

Table S7 Results of the Robust ANCOVA analyzing direct cost of resistance (for B. stricta plants with two contrasting constitutive glucosinolate types

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.