Abstract

Objective To determine whether the variation in unadjusted rates of caesarean section derived from routine data in NHS trusts in England can be explained by maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors.

Design A cross sectional analysis using routinely collected hospital episode statistics was performed. A multiple logistic regression model was used to estimate the likelihood of women having a caesarean section given their maternal characteristics (age, ethnicity, parity, and socioeconomic deprivation) and clinical risk factors (previous caesarean section, breech presentation, and fetal distress). Adjusted rates of caesarean section for each NHS trust were produced from this model.

Setting 146 English NHS trusts.

Population Women aged between 15 and 44 years with a singleton birth between 1 January and 31 December 2008.

Main outcome measure Rate of caesarean sections per 100 births (live or stillborn).

Results Among 620 604 singleton births, 147 726 (23.8%) were delivered by caesarean section. Women were more likely to have a caesarean section if they had had one previously (70.8%) or had a baby with breech presentation (89.8%). Unadjusted rates of caesarean section among the NHS trusts ranged from 13.6% to 31.9%. Trusts differed in their patient populations, but adjusted rates still ranged from 14.9% to 32.1%. Rates of emergency caesarean section varied between trusts more than rates of elective caesarean section.

Conclusion Characteristics of women delivering at NHS trusts differ, and comparing unadjusted rates of caesarean section should be avoided. Adjusted rates of caesarean section still vary considerably and attempts to reduce this variation should examine issues linked to emergency caesarean section.

Introduction

Since the 1970s, many developed countries have experienced substantial growth in the rates of caesarean section.1 2 3 In England, for example, the rate of caesarean sections has increased from 9% in 1980 to 24.6% in 2008-9.4 5 6 Various reasons have been suggested for this increase, including rising maternal age at first pregnancy, technological advances that have improved the safety of the procedure, changes in women’s preferences, and a growing proportion of women who have previously had a caesarean.7 8

Nonetheless, there is concern about whether the current high rates of caesarean section are justified because the procedure is not without risk.9 Women may experience complications after caesarean section such as haemorrhage, infection, and thrombosis,10 and they have an increased risk of complications in subsequent pregnancies (such as uterine rupture and placenta praevia).11 12 13 Neonatal complications, although infrequent, include fetal respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary hypertension, iatrogenic prematurity, and difficulty with bonding and breast feeding.8 9 14

Adding to these concerns is evidence of considerable variation in rates of caesarean section within various countries,15 16 17 including the United Kingdom. In 2000, rates of caesarean section for singleton pregnancies in National Health Service (NHS) maternity units in England and Wales ranged from 10% to 43%.5 In April 2004, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) published guidance on caesarean section with the aim of ensuring consistency and quality of care.4 However, recent figures for births in England during 2008-9 show that rates of caesarean section still vary substantially among NHS trusts.6 These figures also appeared to show a north-south divide, with higher rates in the south of England.

The publication of the 2008-9 figures led to debate about potential causes of the variation in rates of caesarean section. These included differences in the clinical need of local populations, an increase in the number of women without risk factors requesting caesarean sections, a lack of midwives, and different attitudes and practices among professionals.18 19 How much these competing interpretations contributed to the variation is unclear. However, differences between local populations could have been discounted if the figures had been adjusted for maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors.

We describe an analysis of NHS trust and regional rates of caesarean section for singleton pregnancies in England to examine whether the variation can be explained by maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors. We use funnel plots to illustrate whether the variation exceeds that expected from random fluctuations alone, and we extend previous work on rates of caesarean section in England5 by examining whether the variation is greater among women having an elective caesarean section or those having an emergency procedure.

Methods

The study used data from the hospital episode statistics database, which contains records of all patient admissions to NHS hospitals in England. Its core fields contain patient demographics and region of residence, and hospital administrative and clinical details. Diagnostic information is coded using the international classification of diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), and operative procedures are described using the UK Office for Population Censuses and Surveys classification (OPCS), 4th revision. Hospital episode statistics also include additional fields (the “maternity tail”) that capture information specific to deliveries, including onset of labour, parity, birth weight, and length of gestation. However, only around 75% of delivery records in the database have information in the maternity tail.

Definitions

We extracted from the hospital episode statistics database records of women who delivered in English NHS acute trusts between 1 January and 31 December 2008. We restricted the sample to women aged between 15 and 44 years who had a singleton birth, and to NHS trusts whose obstetric units had more than 1000 deliveries in the 12 month period. Deliveries were included if the record contained information about mode of delivery in either the maternity tail or the procedure fields (OPCS codes: R17 to R25). The method of delivery was obtained primarily from the procedure fields. Where data had not been entered to these fields (0.6% of women), information was taken from the maternity tail. An elective caesarean section was defined by OPCS code R17, or by “mode of delivery” code 7 when data were obtained from the maternity tail. An emergency delivery was defined by codes R18 or 8, respectively.

Data on maternal age at delivery, ethnicity, and the NHS trust and region of treatment were obtained from the core fields of the hospital episode statistics. Parity was obtained from the maternity tail. Where parity was not available, a woman was labelled as multiparous if she was found to have had a delivery episode in the previous 10 years of data (April 1997 to December 2007). Otherwise, she was assumed to be nulliparous (the median interval between first and second births is three years20). Among the 193 637 women with parity data in the maternity tail, there was 84% agreement between the nulliparous and multiparous values derived from the maternity tail and those in historical data (kappa=0.69). The majority (92%) of disagreements were because a previous pregnancy could not be identified in the historical data.

Risk factors for caesarean section were identified using all ICD-10 diagnosis fields (see web appendix for exact definitions), which had been adapted from a previously published classification system.21 A previous caesarean section was defined if any diagnosis code indicated a “uterine scar from previous surgery” (ICD-10: O34.2) among multiparous women or if a woman had delivered by caesarean according to the previous 10 years of hospital episode statistics. Among the 312 407 multiparous classifications, there was 91% agreement between the coding of a “uterine scar” and a previous caesarean section in the historical data (kappa=0.66). Most (90%) disagreements arose because a previous caesarean section was found in the historical data for a woman without the coding for a scar.

Finally, socioeconomic deprivation was defined using a five category indicator that was derived from the English Indices of Deprivation 2004 ranking of the English super output areas.22 The categories were defined by partitioning the ranks of the 32 480 areas into quintiles (for example, 0-20th percentiles, 20-40th percentiles) and were labelled 1 (least deprived) to 5 (most deprived). Women were allocated a category on the basis of their region of residence. Where this was missing (1.1% of women), a woman was allocated to the deprivation category that was most common among the women delivering at their NHS trust.

Statistical analysis

The unadjusted rate of caesarean sections for each NHS trust was expressed as a percentage of all live or stillborn births. Regional rates of caesarean section were derived on the basis of the 10 strategic health authorities that have existed since 1 April 2006.

Multiple logistic regression was used to estimate the probability of a woman having had a caesarean section on the basis of her age, ethnicity, level of socioeconomic deprivation, and clinical risk factors for caesarean section. Interactions between maternal age and the clinical risk factors were examined but were not included in the final model because they did not significantly improve the model’s fit (likelihood ratio test, P value>0.3). The ability of the logistic model to discriminate between women who had a vaginal delivery and those who had a caesarean section was summarised using the C statistic. A C statistic of 0.5 indicates that the model discriminates no better than chance alone, whereas a value of 1.0 indicates perfect discrimination.23 The probabilities of caesarean section for women who delivered at the same NHS trust were summed to give the trust’s predicted rate of caesarean section. Risk adjusted rates of caesarean section for each NHS trust were produced by dividing the trust’s unadjusted caesarean section rate by its predicted rate, and multiplying this ratio by the national caesarean section rate. An equivalent process was used to produce adjusted rates for rates of emergency and elective caesarean section. However, because there were now three outcomes (vaginal delivery, elective caesarean section, and emergency caesarean section), we used multinomial logistic regression to estimate the probability of each mode of delivery.

Funnel plots were used to examine the variation among NHS trusts in both crude and risk adjusted rates of caesarean section.24 These plots “test” whether the rate of caesarean sections of a NHS trust differs significantly from the national rate for England, assuming the trust’s rate is only influenced by sampling variation (that is, random errors). The plot contains two funnel limits. Assuming differences arise from random errors alone, the chance of the trust being within the limits is 95% for the inside funnel and 99.8% for the outer funnel. We measured the amount of variation between NHS trusts above that expected from sampling variation by using a random effects approach.24 This estimates an “overdispersion” term that, when added to the sampling variance of each NHS trust, would inflate the funnel limits to fit the observed distribution of caesarean section rates.

Differences between groups were tested using the χ2 test. All P values were two sided, and those lower than 0.05 were judged to be statistically significant. To account for a lack of independence in the data of women treated in the same trust, the standard errors of the regression model coefficients were calculated using a clustered sandwich estimator. STATA (version 10) was used for all statistical calculations.

Results

Between 1 January and 31 December 2008, 620 604 singleton births took place at 146 NHS trusts among women resident in England. Of these, 397 573 (64.1%) were normal vaginal deliveries and 75 305 (12.1%) were vaginal deliveries in which medical instruments were used. The average age of these women was 28.9 years (SD 6.0 years) and, among the 552 290 women with known ethnicity, 124 004 (22.5%) were not white.

There were 147 726 caesarean sections during this period, giving an overall national caesarean section rate of 23.8% for women in England with singleton births. These 147 726 caesarean sections consisted of 57 892 (9.3%) elective and 89 834 (14.5%) emergency procedures.

Association between caesarean section and patient factors

The proportion of women who had a caesarean section differed according to maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors (table 1). A quarter (25%) of nulliparous women had a caesarean section, whereas only 9% of multiparous women underwent a caesarean section if they had no history of caesarean delivery. Women were more likely to have had a caesarean section if they had previously had a caesarean (71%), their baby had a breech presentation (90%), or they had placenta praevia or placental abruption (85%). Among the 46 748 women with a previous caesarean section and who delivered by caesarean, 32 493 (70%) had an elective procedure. Similarly, 11 151 (57%) of the 19 656 women who delivered a breech baby by caesarean had an elective procedure. Overall, 72% of elective caesarean sections (41 709/57 892) were performed for breech presentation or because of a previous caesarean section.

Table 1.

Unadjusted rates of caesarean section according to maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors

| Prevalence (%) | Number of women who underwent caesarean section | Rate of caesarean sections | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singleton pregnancies | 620 604 | 147 726 | 24% |

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| Under 20 | 39 974 (6) | 5304 | 13% |

| 20-24 | 121 182 (20) | 20 709 | 17% |

| 25-29 | 170 161 (27) | 36 691 | 22% |

| 30-35 | 168 011 (27) | 44 915 | 27% |

| Over 35 | 121 276 (20) | 40 107 | 33% |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 428 286 (69) | 100 662 | 24% |

| Afro-Caribbean | 36 548 (6) | 10 892 | 30% |

| Asian | 63 258 (10) | 15 328 | 24% |

| Other | 24 198 (4) | 5863 | 24% |

| Unknown | 68 314 (11) | 14 981 | 22% |

| Level of socioeconomic deprivation | |||

| 1 (least deprived) | 96 144 (15) | 25 138 | 26% |

| 2 | 98 383 (16) | 25 149 | 26% |

| 3 | 111 434 (18) | 27 329 | 25% |

| 4 | 135 461 (22) | 31 414 | 23% |

| 5 (most deprived) | 179 182 (29) | 38 696 | 22% |

| Clinical risk factors | |||

| Parity | |||

| Nulliparous | 312 722 (50) | 78 176 | 25% |

| Multiparous: no previous caesarean section | 241 824 (39) | 22 802 | 9% |

| Multiparous: previous caesarean section | 66 058 (11) | 46 748 | 71% |

| Breech | 21 869 (4) | 19 636 | 90% |

| Fetal distress | 137 603 (22) | 45 482 | 33% |

| Dystocia | 110 233 (18) | 44 548 | 40% |

| Pre-existing diabetes mellitus | 3072 (0.5) | 1856 | 60% |

| Pre-existing hypertension | 2523 (0.4) | 1067 | 42% |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 12 065 (1.9) | 5074 | 42% |

| Eclampsia or pre-eclampsia | 11 680 (1.9) | 6005 | 51% |

| Placenta praevia or placental abruption | 5902 (1.0) | 5003 | 85% |

| Preterm delivery | 29 619 (4.8) | 11 158 | 38% |

A total of 313 987 women, 51% of the overall sample, had none of the specified clinical risk factors for a caesarean section. Just 15 431 (4.9%) of these women had a caesarean delivery. These caesarean sections consisted of 4499 (29%) emergency deliveries and 10 932 (71%) elective procedures. The proportion of women with no clinical risk factors who had a caesarean section increased with maternal age, ranging from 1.7% (387/22 812) for women aged under 20 years to 9.2% (5021/54 288) for women aged 35 years or over.

Table 2 summarises the risk of a caesarean section associated with the maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors studied. The likelihood of a caesarean section was higher in older women, independent of other risks, and in Afro-Caribbean women. The odds ratios of caesarean section were greatest for women who had placenta praevia or placental abruption, previously had caesarean section, or had breech presentation. The influences of other obstetrical complications such as dystocia and fetal distress were significant but less marked. Overall, the regression model discriminated well between women who did and those who did not deliver by caesarean (C statistic=0.86).

Table 2.

Odds ratio of caesarean section for maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors

| Unadjusted odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical risk factors | |||

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| Under 20 | 0.74 | 0.73 (0.70 to 0.76) | <0.001 |

| 20-24 | 1 | 1 | |

| 25-29 | 1.33 | 1.24 (1.21 to 1.27) | |

| 30-35 | 1.77 | 1.57 (1.52 to 1.62) | |

| Over 35 | 2.40 | 2.14 (2.05 to 2.24) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 1 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Afro-Caribbean | 1.38 | 1.47 (1.36 to 1.58) | |

| Asian | 1.04 | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.11) | |

| Other | 1.04 | 1.06 (0.98 to 1.14) | |

| Unknown | 0.91 | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.98) | |

| Level of socioeconomic deprivation | |||

| 1 (least deprived) | 1 | 1 | 0.811 |

| 2 | 0.98 | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.06) | |

| 3 | 0.92 | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.08) | |

| 4 | 0.86 | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.09) | |

| 5 (most deprived) | 0.78 | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07) | |

| Parity | |||

| Nulliparous | 1 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Multiparous: no previous caesarean section | 0.31 | 0.35 (0.33 to 0.38) | |

| Multiparous: previous caesarean section | 7.26 | 11.54 (10.75 to 12.39) | |

| Breech | 32.31 | 72.23 (63.71 to 81.89) | <0.001 |

| Fetal distress | 1.84 | 2.34 (2.12 to 2.58) | <0.001 |

| Dystocia | 2.68 | 3.57 (3.24 to 3.92) | <0.001 |

| Pre-existing diabetes mellitus | 4.94 | 4.47 (3.98 to 5.03) | <0.001 |

| Pre-existing hypertension | 2.36 | 1.82 (1.65 to 2.00) | <0.001 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 2.37 | 2.25 (2.09 to 2.42) | <0.001 |

| Eclampsia or pre-eclampsia | 3.49 | 3.85 (3.55 to 4.18) | <0.001 |

| Placenta praevia or placental abruption | 18.40 | 34.97 (30.10 to 40.62) | <0.001 |

| Preterm delivery | 2.01 | 1.59 (1.50 to 1.70) | <0.001 |

*Wald test.

Variation between trusts in adjusted rates of caesarean section

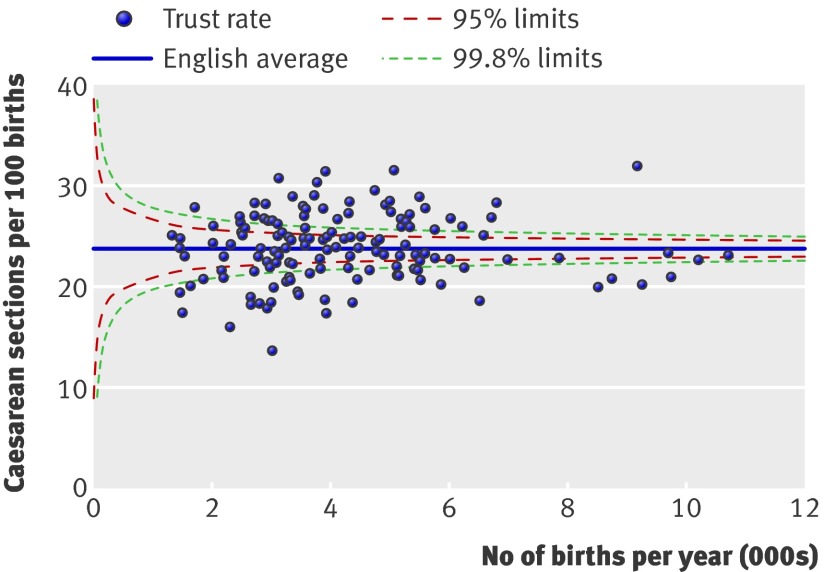

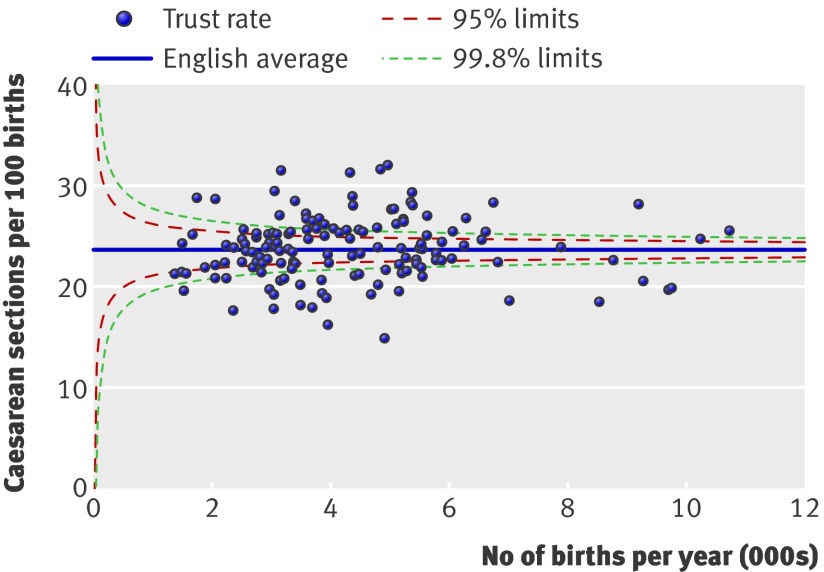

The unadjusted rates of caesarean section varied substantially between NHS trusts (fig 1), ranging from 13.6% to 31.9%. The range was not unduly influenced by a few extreme values: 80% of NHS trusts had rates between 19.5% and 28.0%, the 10th and 90th percentiles. Although NHS trusts differed considerably in their patient populations, 80% of NHS trusts had predicted rates of caesarean section between 20.6% and 27.5%. However, taking account of the differences in the patient characteristics did not reduce the variation in the rates of caesarean section between NHS trusts. The adjusted rates of caesarean section still differed substantially, ranging from 14.9% to 32.1% (fig 2). The overdispersion terms for the unadjusted and adjusted rates were 3.8 and 2.7, respectively.

Fig 1 Funnel plot showing unadjusted rates of caesarean section among women who had singleton deliveries in English NHS trusts during 2008

Fig 2 Funnel plot showing rates of caesarean section among women who had singleton deliveries in English NHS trusts during 2008, adjusted for maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors

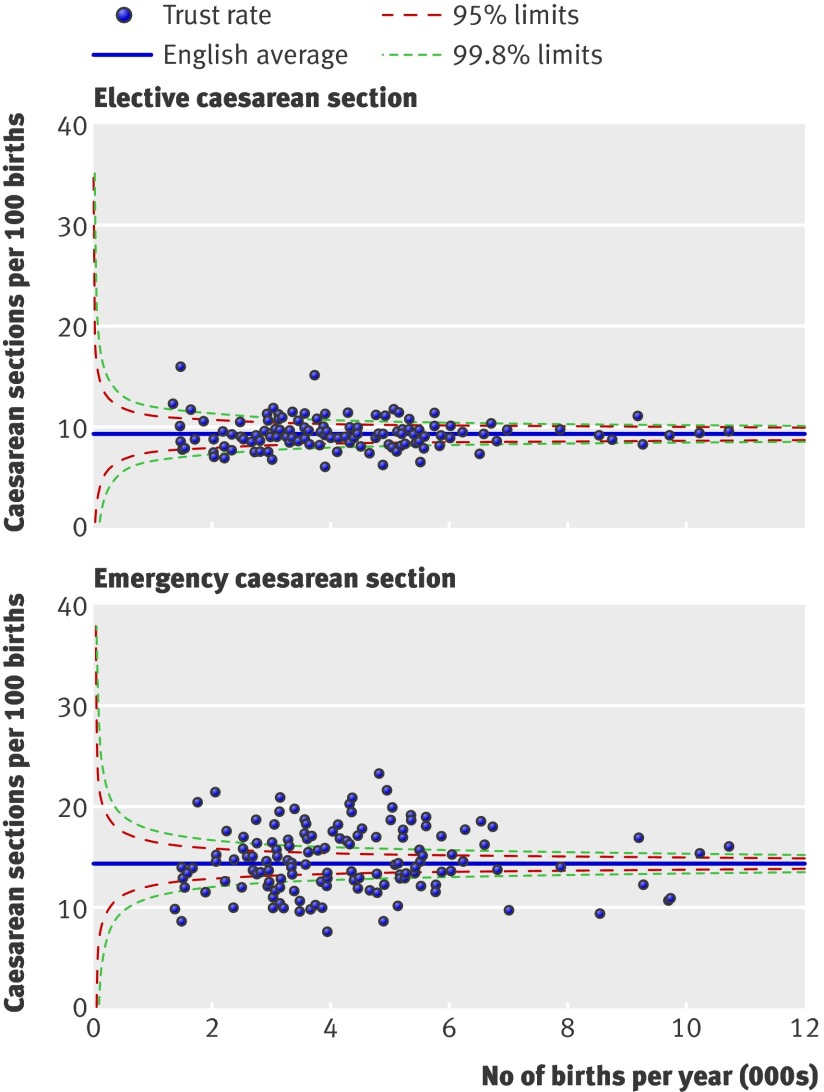

This variation in the overall rate of caesarean sections between trusts arose mainly from differences in the rates of emergency caesarean section (fig 3). The 10th and 90th percentiles of the adjusted rates of emergency caesarean section among NHS trusts were 10.7% and 18.9%, whereas for elective caesarean sections, these percentiles were 7.8% and 11.2%. The overdispersion term for the adjusted rates of emergency caesarean section was 4.9; for the adjusted rate of elective caesarean section, it was 0.4.

Fig 3 Elective and emergency caesarean section rates among women who had singleton deliveries in English NHS trusts during 2008, adjusted for maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors

Figure 4 shows the differences between strategic health authorities in the unadjusted rates of caesarean section. There was a distinct north-south divide according to these unadjusted rates, with the average rates in the southern authorities being noticeably higher. However, after adjusting for maternal characteristics and risk factors, these regional differences were greatly reduced and the divide was no longer apparent. Figure 4 also highlights that the variation between strategic health authorities was small compared with the variation between trusts.

Fig 4 Unadjusted and adjusted rates of caesarean section among women who had singleton deliveries during 2008, organised by strategic health authority. Rates are adjusted for maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors. E Eng, East of England; E Mid, East Midlands; Lond, Greater London; NE, North East; NW, North West; S Cent, South Central; SE, South East; SW, South West; Y & H, Yorkshire and Humberside; W Mid, West Midlands

Finally, the differences in the average rate of caesarean sections among small (<2500 deliveries), medium (2500-4000 deliveries), and large (>4000 deliveries) NHS trusts were small in comparison with the variation within each of these categories of NHS trust. The overall adjusted rates of caesarean section for small, medium, and large NHS trusts were 22.8%, 23.6%, and 24.0%, respectively.

Discussion

In 2008, almost one in four deliveries in English NHS trusts was a caesarean section. The likelihood of a caesarean section was strongly associated with maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors, and NHS trusts were estimated to have a range of rates of caesarean section owing to differences in their patient populations. However, adjusting for maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors did not greatly reduce the observed variation between individual trusts, with rates ranging from 14.9% to 32.1%. We found that risk adjustment reduced the regional differences in unadjusted rates of caesarean section, in contrast to the effect of adjustment on between trust variation, and suggests there is no north-south divide in England. The adjusted rates of caesarean section among small, medium, and large NHS trusts were also similar.

That the variance in patient populations could not explain the observed variation in rates of caesarean section is consistent with the findings of a study of caesarean section rates in England in 2000.5 Unfortunately, because of changes in the organisation of hospitals in the intervening years, it is not possible to comment whether the level of variation has changed between 2000 and 2008.

Finally, the results show that the variation in overall rates of caesarean section stems predominantly from variation in rates of emergency caesarean section. This possibility has been discussed by other studies,5 15 and evidence of this relation was found in one regional study from France.16 We are unaware of any other study showing this link or that rates of elective caesarean section at English NHS trusts exhibit only slightly more variation than would be expected from random factors alone.

Strengths and limitations of study

Hospital episode statistics database includes information on all deliveries in English NHS maternity units, which reduces the risk of selection bias. In 2007, 96.5% of all deliveries in England occurred in NHS trusts.20 There is some regional variation in the proportion of home births and in the number of deliveries in independent hospitals, but given that they represent only 2.8% and 0.7% of births in England, respectively, the error resulting from their omission will be small.

A limitation of our study is the possibility of inaccuracies in the coding for the method of delivery. Elective and emergency caesareans were defined using the first three characters of the full four character OPCS codes. Using broader categories has been shown to be more reliable than using specific codes, in studies of both hospital episode statistics25 and other administrative databases.26 27 We could not find any study validating the coding of caesarean procedures in hospital episode statistics against hospital records, but studies in other countries have reported high levels of agreement (kappa>0.98, where stated).27 28 29 Thus, errors in the coding of caesarean procedures are unlikely to explain the large between trust variation in overall rates of caesarean section.

The coding of emergency and elective caesarean section has been reported to be less accurate but agreement between hospital episode statistics against hospital records was still excellent (kappa=0.88 and 0.84 for elective and emergency caesarean section).27 Moreover, widespread miscoding of these procedures would have resulted in similar levels of overdispersion for elective and for emergency procedures. Consequently, coding errors are unlikely to account for the large variation in rates of emergency caesarean section between trusts.

Another limitation of our analysis is the incompleteness and inaccuracy of the information on clinical risk factors that we used to derive the adjusted rates. Some maternal characteristics and obstetric conditions were under-reported throughout hospital episode statistics (for example, obesity), so it was not possible to include these in the regression analysis. Other factors (such as duration of gestation and birth weight) had to be ignored because the completeness of the data differed between NHS trusts. Consequently, there is likely to be some residual confounding. Nonetheless, the discrimination of the logistic regression model was very good (C statistic=0.86).

Although parity and previous caesarean section were incompletely coded in the hospital episode statistics, we were able to determine missing values for these variables from historical data. The internal consistency of this approach was good, and using longitudinal data to find previous caesarean births has been validated elsewhere.30 There were no obvious gaps in the completeness of data for the other risk factors across the NHS trusts, and their overall prevalence rates were similar to those reported by the National Sentinel Caesarean Section Audit.31

Implications for the publication of maternity statistics

The reported variation in rates of caesarean section between NHS trusts6 led to debate about the use of caesarean section in England.18 19 Various reasons for the variation were proposed, but these are speculative. Moreover, using unadjusted rates of caesarean section as a quality indicator has been shown to be flawed because failing to account for clinical factors may lead to incorrect conclusions.15 32 A first step to improving our understanding of maternity statistics would be to replace publication of unadjusted rates of caesarean section with publication of either rates of caesarean section for women with particular clinical indications or risk adjusted figures. A second step would be for any publication to include an appropriate measure of statistical uncertainty and whether an individual rate is to be considered “divergent.” For example, the fact that many NHS trusts fell outside the control limits suggests that overdispersion should be explicitly included in assessments of performance until the reasons for the excess variability are understood.24

This study highlights various weaknesses in the hospital episode statistics that must be addressed if clinicians, patients, and policy makers are to make greater use of maternity statistics derived from these data. Priority should be given to improving the completeness of the maternity tail, a persistent weakness of hospital episode statistics.33 34 NHS trusts could start by ensuring data on parity and gestational age are complete, because this information is fundamental to deriving meaningful statistics on intrapartum care. Nonetheless, hospital episode statistics will require other refinements to improve the relevance of caesarean section figures for monitoring quality of care. For example, Robson et al35 defined patient groups to enable the comparison of rates of caesarean section, and these categories were used by the National Sentinel Caesarean Section Audit.31 In addition, the 2004 NICE guideline recommended that the urgency of a caesarean section be indicated using the Lucas/National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) classification and noted that replacing the terms “emergency” and “elective” with its four grades of urgency would aid communication between health professionals.4 Currently, hospital episode statistics are unable to capture either the Lucas/NCEPOD urgency classification, or all the items required to derive Robson groups.

Implications for clinical practice

The lack of uniformity in the use of caesarean section in England was not associated with clinical indications for caesarean section. Almost all women with placenta praevia, placental abruption, or a breech presentation had a caesarean section. The lack of variation for a breech presentation suggests broad agreement of current practice with NICE guidance.4 The guidance recommends that caesarean section be offered to women with a breech presentation at term (in whom external cephalic version is contraindicated or has been unsuccessful) and was based on reported benefits of caesarean from the Term Breech Trial.36

Some of the variation in rates of caesarean section is likely to reflect different preferences among women, such as willingness to try vaginal delivery after a previous caesarean section. However, it seems unlikely that maternal request in the absence of any clinical indication18 19 contributes substantially to the rates. Nearly three quarters (72%) of elective caesarean sections were performed for a breech presentation or a previous caesarean section, and the adjusted rates of elective caesarean section did not differ greatly between NHS trusts.

We observed that variation in the overall rates of caesarean section was associated with rates of emergency procedures. Various studies have discussed the likelihood of this relation,5 17 although quantitative confirmation has been rare.16 One contributing factor is that the term “emergency caesarean section” covers a wide range of clinical situations, from an immediate threat to the life of the woman or fetus to a situation requiring early delivery although there is no maternal or fetal compromise.4 Allied to this is the lack of a precise definition for fetal compromise or dystocia,17 both common reasons for emergency caesarean section. The diagnosis of fetal compromise or dystocia can be difficult and can result from a variety of clinical assessments.8

Studies have established that rates of caesarean section are influenced by the use of electronic fetal monitoring and fetal scalp blood sampling, the use of partograms, active management of labour, and whether or not consultants are involved in the decision making process.4 37 38 The observed variation in rates suggests that NHS trusts should examine whether use of caesarean section locally can be made more compliant with recent NICE guidelines on caesarean section4 and intrapartum care.39

Conclusions and policy implications

Variation in rates of caesarean section among English NHS trusts continues to cause concern and be debated. Our results demonstrate that some issues apparent in unadjusted rates of caesarean section, such as the north-south divide, disappear once maternal characteristics and clinical risk factors are taken into account. The results also suggest that another explanation—that high numbers of low risk women are requesting elective caesarean—is unlikely to be a major contributor because most women undergoing a caesarean section in 2008 had at least one clinical risk factor, and there is little variation in adjusted rates of elective caesarean section. Instead, the most variation was observed in the use of emergency caesarean section. NHS trusts, with the support of strategic health authorities and commissioners, need to examine the reasons for variation in caesarean section in their regions and how the consistency of care for pregnant women can be improved.

What is known about this topic

Routine hospital data show that the proportion of women having a caesarean section varied between English NHS trusts in 2008-9, with higher rates in the south of England compared with the north

This variation could reflect differences in clinical need, choices offered to women, or clinical practice

The hospital data were not adjusted for maternal characteristics or clinical risk factors, which hampered interpretation by not removing legitimate reasons for variation

What this study adds

NHS trusts in England vary in their patient populations—predicted rates of caesarean section for NHS trusts estimated on the basis of their population characteristics and risk factor profile were between 20.6% and 27.5% for 80% of trusts

Rates of caesarean section still varied substantially between NHS trusts after adjustment, with adjusted rates of caesarean section ranging from 14.9% to 32.1%; however, adjustment removed the apparent north-south divide

There was little variation between NHS trusts in rates of elective caesarean section, with 72% of these procedures being performed for breech presentation or a previous caesarean section

Most variation in overall rates of caesarean section was associated with rates of emergency caesarean section, which probably reflects the lack of precise criteria for fetal distress or dystocia and differences in management practices

We thank the Department of Health for providing the hospital episode statistics data used in this study.

Contributors: DAC, LCE, TAM, AT, and JHvdM conceived and designed the study; FB, IG-U, and DAC conducted the statistical analyses; FB and DAC wrote the manuscript; LCE, IG-U, TAM, AT, and JHvdM commented on drafts. DAC is guarantor.

Funding: JHvdM received a national public health career scientist award from the Department of Health and NHS research and development programme.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.”

Ethical approval: Not required for the analysis of anonymised routine data for service evaluation.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c5065

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Indications and clinical conditions associated with an increased risk of caesarean section

References

- 1.Belizán JM, Althabe F, Barros FC, Alexander S. Rates and implications of caesarean sections in Latin America: ecological study. BMJ 1999;319:1397-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet 1985;2:436-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Althabe F, Sosa C, Belizán JM, Gibbons L, Jacquerioz F, Bergel E. Cesarean section rates and maternal and neonatal mortality in low-, medium-, and high-income countries: an ecological study. Birth 2006;33:270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Caesarean section. National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Paranjothy S, Frost C, Thomas J. How much variation in CS rates can be explained by case mix differences? BJOG 2005;112:658-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Information Centre. NHS maternity statistics, England: 2008-09. Department of Health, 2009.

- 7.Porreco RP, Thorp JA. The caesarean birth epidemic: trends, causes, and solutions. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:369-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Churchill H, Savage W, Francome C. Caesarean birth in Britain. 2nd ed. Middlesex University Press, 2006

- 9.Shorten A. Maternal and neonatal effects of caesarean section. BMJ 2007;335:1003-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deneux-Tharaux C, Carmona E, Bouvier-Colle MH, Bréart G. Postpartum maternal mortality and cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Leindecker S, Varner MW, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2581-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Q, Wen SW, Oppenheimer L, Chen XK, Black D, Gao J, et al. Association of caesarean delivery for first birth with placenta praevia and placental abruption in second pregnancy. BJOG 2007;114:609-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, Zavaleta N, Carroli G, Velazco A, et al. Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet 2006;367:1819-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiMatteo MR, Morton SC, Lepper HS, Damish TM, Carney MF, Pearson M, et al. Cesarean childbirth and psychological outcomes: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 1996;15:303-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fantini MP, Stivanello E, Frammartino B, Barone AP, Fusco D, Dallolio L, et al. Risk adjustment for inter-hospital comparison of primary cesarean section rates: need, validity and parsimony. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabilloud M, Ecochard R, Guilhot J, Toselli A, Mabriez JC, Matillon Y. Study of the variations of the caesarean section rate in the Rhône-Alpes region (France): effect of women and maternity service characteristics. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1998;78:11-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Librero J, Peiró S, Calderón SM. Inter-hospital variations in caesarean sections. A risk adjusted comparison in the Valencia public hospitals. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:631-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BBC News. Emergency c-sections predominate. 27 October 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/8328049.stm.

- 19.Boseley S. Caesarean births: high number and postcode variation worries experts. Guardian. 27 October 2009. http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2009/oct/27/caesarean-births-high-number.

- 20.Office for National Statistics. Birth statistics: births and patterns of family building. England and Wales FM1 no 36, 2007. Office for National Statistics, 2008.

- 21.Henry OA, Gregory KD, Hobel CJ, Platt LD. Using ICD-9 codes to identify indications for primary and repeat cesarean sections: agreement with clinical records. Am J Public Health 1995;85:1143-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. The English indices of deprivation 2004: summary (revised). www.communities.gov.uk/documents/communities/pdf/131206.pdf.

- 23.Hosmer DW and Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. Wiley, 2000.

- 24.Spiegelhalter DJ. Funnel plots for comparing institutional performance. Stat Med 2005;24:1185-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dixon J, Sanderson C, Elliott P, Walls P, Jones J, Petticrew M. Assessment of the reproducibility of clinical coding in routinely collected hospital activity data: a study in two hospitals. J Public Health Med 1998;20:63-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henderson T, Shepheard J, Sundararajan V. Quality of diagnosis and procedure coding in ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2006;44:1011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts CL, Bell JC, Ford JB, Morris JM. Monitoring the quality of maternity care: how well are labour and delivery events reported in population health data? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009;23:144-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Martin DP. Risk of uterine rupture during labor among women with a prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 2001;345:3-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasmeen S, Romano PS, Schembri ME, Keyzer JM, Gilbert WM. Accuracy of obstetric diagnoses and procedures in hospital discharge data. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:992-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen JS, Roberts CL, Ford JB, Taylor LK, Simpson JM. Cross-sectional reporting of previous Cesarean birth was validated using longitudinal linked data. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas J, Paranjothy S. National sentinel caesarean section audit report. RCOG Press, 2001. [PubMed]

- 32.Aron DC, Harper DL, Shepardson LB, Rosenthal GE. Impact of risk-adjusting cesarean delivery rates when reporting hospital performance. JAMA 1998;279:1968-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Middle C, MacFarlane A, Labour and delivery of “normal” primiparous women: analysis of routinely collected data. BJOG 1995;102:970-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Healthcare Commission. Towards better births: a review of maternity services in England. Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection, 2008.

- 35.Robson MS, Scudamore IW, Walsh SM. Using the medical audit cycle to reduce caesarean section rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:199-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet 2000;356:1375-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alfirevic Z, Devane D, Gyte GML. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;3:CD006066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown HC, Paranjothy S, Dowswell T, Thomas J. Package of care for active management in labour for reducing caesarean section rates in low-risk women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;4:CD004907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Intrapartum care. Care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. RCOG Press, 2007. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Indications and clinical conditions associated with an increased risk of caesarean section