Abstract

Ischemia with subsequent reperfusion (IR) injury is a significant clinical problem that occurs after physical and surgical trauma, myocardial infarction, and organ transplantation. IR injury of mouse skeletal muscle depends on the presence of both natural IgM and an intact C pathway. Disruption of the skeletal muscle architecture and permeability also requires mast cell (MC) participation, as revealed by the fact that IR injury is markedly reduced in c-kit defective, MC-deficient mouse strains. In this study, we sought to identify the pathobiologic MC products expressed in IR injury using transgenic mouse strains with normal MC development, except for the lack of a particular MC-derived mediator. Histologic analysis of skeletal muscle from BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice revealed a strong positive correlation (R2 = 0.85) between the extent of IR injury and the level of MC degranulation. Linkage between C activation and MC degranulation was demonstrated in mice lacking C4, in which only limited MC degranulation and muscle injury were apparent. No reduction in injury was observed in transgenic mice lacking leukotriene C4 synthase, hemopoietic PGD2 synthase, N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase-2 (enzyme involved in heparin biosynthesis), or mouse MC protease (mMCP) 1. In contrast, muscle injury was significantly attenuated in mMCP-5-null mice. The MCs that reside in skeletal muscle contain abundant amounts of mMCP-5 which is the serine protease that is most similar in sequence to human MC chymase. We now report a cytotoxic activity associated with a MC-specific protease and demonstrate that mMCP-5 is critical for irreversible IR injury of skeletal muscle.

The classical C pathway and naturally occurring IgM from B-1 lymphocytes are essential components of hind limb ischemia-reperfusion (IR)4 injury in the mouse (1, 2). These data have led to the hypothesis that activation of the classical C pathway with formation of membrane-attack complexes leads to muscle injury. However, the finding that muscle damage is markedly attenuated in C-sufficient but mast cell (MC)-deficient B6D2F1-KitWf/KitWf (Wf/Wf) and WBB6F1-KitW/KitW (W/Wv) mice (3–5) indicates that IR-mediated injury is a more complex pathologic response than currently understood and that MCs play a prominent role in this cytotoxic injury.

After activation, mature MCs quickly exocytose the contents of their secretory granules, which include histamine, serotonin, heparin- and chondroitin sulfate-serglycin proteoglycans, multiple serine proteases, carboxypeptidase A3, and preformed cytokines such as TNF-α. MC activation also results in the rapid generation of the eicosanoids PGD2 and cysteinyl leukotriene C4 (LTC4) (6, 7), followed hours later by increased expression of numerous cytokines and chemokines (8, 9). Although this diverse array of MC-derived products contributes to the vascular leakage and cellular infiltration characteristic of a brisk host inflammatory response, it has not been shown that any of these MC-derived mediators participate in IR-mediated injury of skeletal muscle cells. Classical activation of MCs in adaptive immune responses occurs by cross-linking of IgE bound to FcεRI or by the direct interaction of preformed immune complexes with the low-affinity Ig receptor FcγRIII (10, 11). In addition, several other signals associated with innate immunity, including the anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a and adenosine, can activate MCs (12–16).

The apparent requirement for both the classical C pathway and MCs in IR-induced injury suggested that MC degranulation occurs as a consequence of C activation. In this study, we sought to test the hypothesis that the MC is a critical effector cell downstream of C and then to establish the role of the MC independent of the broad impact of c-kit deficiency on the hemopoietic lineage and other cell types (17–19). We demonstrate reduced levels of both MC degranulation and muscle injury in C4-deficient mice, thereby confirming an essential role for the C pathway in IR injury of muscle. We then delineate the contribution of individual MC-derived mediators by quantitative analysis of the extent of hind limb IR injury and MC degranulation in MC-sufficient strains with targeted disruption of a particular mediator. We demonstrate that of all of the tested MC mediators, only mouse MC protease (mMCP)-5 plays a significant effector role in severe IR-induced rhabdomyolysis of skeletal muscle.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice and BALB/c mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Transgenic mice lacking N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase (NDST)-2 (20), the C5aR (21), C4 (22), hemopoietic PGD2 synthase (PGD2S; Y. Kanaoka, unpublished data), and LTC4 synthase (LTC4S) (23) were on a C57BL/6 genetic background. Transgenic mice lacking mMCP-1 (24) were on a BALB/c mouse genetic background and the C3aR-null mice (25) were generated on both backgrounds. mMCP-5-null mice were generated by targeted mutation of the mMCP-5 gene in embryonic stem cells. The gene was cloned from a BALB/c genomic library as previously described (26) and was mutated by the insertion of the neomycin gene (Ref. 27 and R. L. Stevens, unpublished data). Two independently derived embryonic stem cell clones (129 origin) were identified, expanded, and used to generate independent founders on C57BL/6 (mMCP-5/BL6−/−) or BALB/c (mMCP-5/BALB−/−) genetic backgrounds. These founders were further backcrossed with the respective wild-type strains. At the time of experimentation, the mMCP-5/BL6−/− strain was 91.8% (± 0% from two mice analyzed) homologous to the background C57BL/6 mice and the mMCP-5/BALB−/− strain was 90.7% (± 1.5% from two mice analyzed) homologous to the background BALB/c mice by satellite marker analysis using 110 and 108 background strain markers, respectively (Charles River Laboratories Genetic Testing Services). These finding are equivalent to four backcross generations. Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval was obtained for all animal experiments, and the studies were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health and Public Health Service guidelines for animal care.

IR procedure

Male mice >8 wk of age and weighing >25 g were anesthetized with i.p. injections of ketamine (120 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). After full sedation was achieved, the hind limbs of each mouse were elevated for 2 min to minimize retained blood. Bilateral rubber bands (Latex O-Rings) were then applied above the greater trochanter using the McGivney Hemorrhoidal Ligator (Miltex). In most experiments, mice were subjected to 2 h of hind limb ischemia, followed by 3 h of reperfusion before analysis. Sham-treated mice did not undergo ischemia. Hydration was maintained by i.v. infusion of 0.1 ml of 0.9% saline during each hour of reperfusion. Mice were maintained in a supine position and kept anesthetized by intermittent i.p. injections of ketamine and xylazine. They were covered throughout the experiment to maintain body temperature. After euthanasia by anesthetic overdose, two 1-cm longitudinal and two 0.5-cm cross-sectional portions of gastrocnemius muscle were taken from each mouse.

Histology, histochemistry, and enzyme cytochemistry

Tissues were fixed for 8 h in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded in JB-4 glycolmethacrylate, sectioned at 1.5-μm thickness, and picked up on coated glass slides for staining with Masson's trichrome for histologic assessment of muscle fiber integrity. Fifty individual muscle fibers were counted in each histologic section, and the extent of injury was expressed as the number of damaged fibers per 50 fibers counted (50 fc). The histologic appearance of Masson's trichrome-stained preparations of the skeletal muscle from an IR-treated C57BL/6 mouse is quite different from that of a sham-treated C57BL/6 mouse. Uninjured muscle cells stain uniformly dark pink to red, have straight margins, a uniform width throughout their mid-portion, pronounced periodic A and I band striations, and intact actin/myosin bundles. In progressive order, injured muscle cells exhibit varying widths resulting in irregular margins, broadening and irregular spacing of the A and I striations, dissolution of the actin/myosin bundles (rhabdomyolysis), and decreased intensity of staining. The earliest injury seen is the wavy fiber/distorted costameres (28), which consist of slightly undulating cell borders, irregular spacing of the striations, and slightly decreased intensity in staining of the cells. The most severely injured cells have discontinuities in their sarcolemma; broken, serpentine aggregates of actin and myosin; and severe loss of staining. There are ∼35– 40 individual muscle fibers across an entire muscle bundle in a longitudinal section at ×10 objective. The most pronounced injury is usually in the middle of the muscle bundle. The overall distribution of injured skeletal muscle is one of patchiness.

For identification of MCs, tissue sections were assessed for their chloroacetate esterase activity, which labels the prominent proteases in the MC granules. In this cytochemistry assay, protease/proteoglycan macromolecular complexes released from the MC or retained inside its granules stain bright red. A section through an intact MC contains >75 secretory granules. When three or more of their secretory granules were found outside the cell, the cell was counted as degranulating. We noted that degranulation was generally limited to those MCs within the injured skeletal muscle bundles.

Assessment of the presence of mMCP-5 in skeletal muscle MCs was performed on frozen tissue samples from skeletal muscle. The mMCP-5 was identified using rabbit anti-mMCP-5 Ab made to an mMCP-5-specific peptide as previously described (29). The Ab was affinity purified using the immunizing peptide and was used at a final dilution of 1/500.

Statistical analysis

Student's t test for paired samples was used for direct comparisons of observations made in control and knockout animals. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used in estimating the relationship between muscle injury and MC degranulation for wild-type control animals. A p <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Time course of muscle injury and MC degranulation after reperfusion of ischemic skeletal muscle

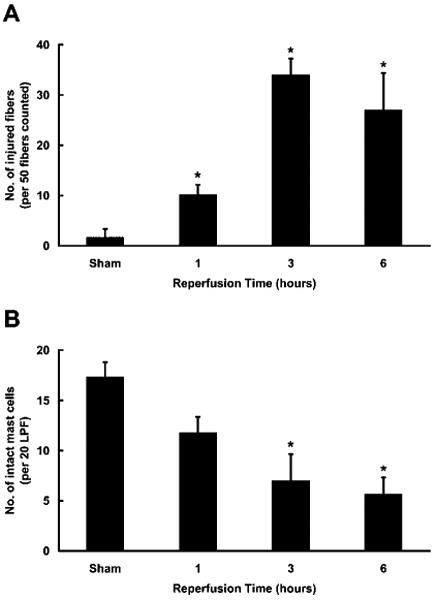

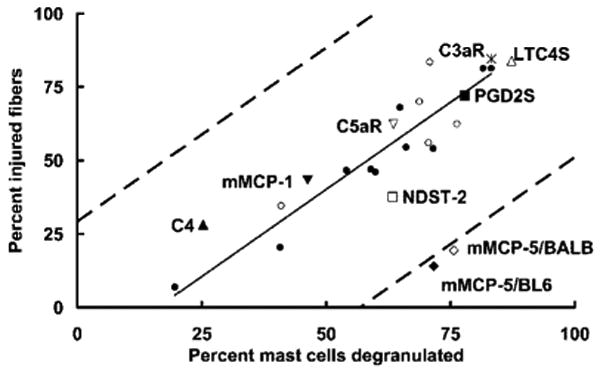

In our initial study of hind limb IR injury in W/Wv mice and their +/+ littermates, MC degranulation and muscle injury were assessed after 3 h of reperfusion (4). Others have assessed muscle damage 24 h after reperfusion (3, 5). To determine the time course of MC degranulation relative to skeletal muscle injury, we assessed each at 1, 3, and 6 h after the initiation of reperfusion in C57BL/6 mice. Skeletal muscle damage was expressed as the number of injured fibers per 50 fc. MC degranulation was quantitated as the number of degranulated MC in 20 low-power (×10 objective) fields (LPF). Both irreversible muscle damage and MC degranulation exhibited time-dependent changes only after the initiation of reperfusion. Although skeletal muscle injury was maximal at the 3-h time point, substantial injury was seen consistently 1 h after the initiation of reperfusion (Fig. 1A). MC degranulation showed a similar time course, with detectable activation and exocytosis of granules occurring within 1 h and reaching maximal levels by 3 h (Fig. 1B). Comparable muscle damage and MC degranulation also were noted in the IR-treated BALB/c mouse (Fig. 2). For both wild-type mouse strains, the extent of muscle damage was strongly correlated with the percentage of MCs exhibiting degranulation (R2 = 0.85, Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1.

Assessment of the time-dependent appearance of muscle injury and MC degranulation. Histological assessment of muscle injury (A) and MC degranulation (B) after 2 h of ischemia and various times of reperfusion in C57BL/6 mice. A, The mean numbers (±SEM) of injured fibers per 50 fc from 3 to 6 animals in three separate experiments are plotted (*, p < 0.05 relative to sham). B, The mean numbers of intact MC (±SEM) in 20 LPF are plotted for the same animals described in A (*, p < 0.05 relative to sham).

FIGURE 2.

Correlation of IR-induced muscle damage with MC degranulation. The mean percentage of injured muscle fibers vs the mean percentage of degranulated MCs after hind limb IR injury was plotted for each mouse strain studied in this investigation. The correlation coefficient and solid trend line are based on the mean values from the injured wild-type control groups (C57BL/6 (●), n = 10, and BALB/c (○), n = 5) in the individual experiments including the time course presented in Fig. 1. The Pearson correlation coefficient (R2) for the data for wild-type mice alone is 0.85. The 95% confidence interval relative to the trend line is indicated by dashed lines. Also indicated are the mean percentages for muscle injury and MC degranulation obtained from all studies with transgenic mice that do not express C3aR (*), C5aR (∇), C4 (▲), LTC4S (△), PGD2S (■), mMCP-1 (▼), mMCP-5/BL6 (◆), mMCP-5/BALB (◇), or NDST-2 (□).

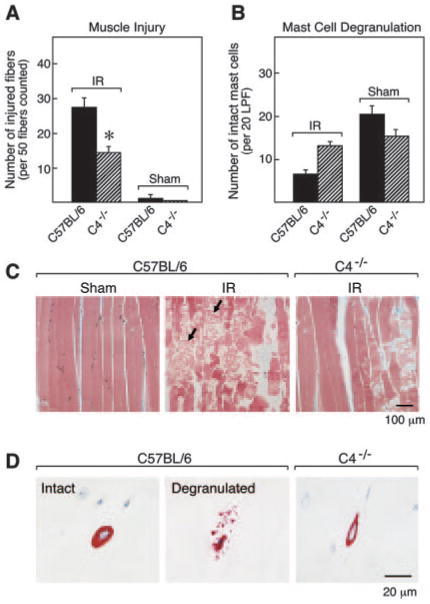

Dependence of muscle injury and MC degranulation on the C pathway

Earlier studies indicated that C activation was necessary for IR injury. Mice lacking C3 or C4 showed about a 50% reduction in the change in vascular permeability relative to similarly treated wild-type controls (1), and a semiquantitative assessment of muscle integrity in C5-deficient mice also indicated an ∼50% attenuation of muscle damage (2). Since none of these earlier studies included a parallel assessment of MC activation and skeletal muscle injury, we evaluated the extent of muscle damage and MC degranulation concomitantly in C4-null mice after hind limb IR. Relative to their controls, muscle injury in C4-null mice was reduced by 48% and MC degranulation was reduced by 85% (Figs. 2 and 3). These results link activation of the classical C pathway to both MC degranulation and skeletal muscle injury and suggest that C activation precedes MC participation in the injury process.

FIGURE 3.

IR-induced muscle damage and MC degranulation in C4−/− mice. A, The mean number (±SEM) of injured muscle fibers per 50 fc is shown for 8 IR-treated C57BL/6 mice, 12 IR-treated C4−/− mice, 3 sham-treated C57BL/6 mice, and 4 sham-treated C4−/− mice in two separate experiments (*, p < 0.01 relative to wild type). B, The mean number (±SEM) of intact MCs per 20 LPF was quantitated for each group described in A. C and D, Representative histological sections from these experiments. C, Gastrocnemius muscle sections were stained with Masson's trichrome. Large numbers of injured muscle fibers were detected in the muscle of IR-treated C57BL/6 mice with serpigenous strands of actin/myosin and rhabdomyolysis (arrows, middle panel). Minimal irreversible damage occurred in sham-treated C57BL/6 mice (left panel) and IR-treated C4−/− mice (right panel). D, High-power (×50 objective) magnification fields of the chloroacetate esterase-positive MCs in the muscle of the three groups as in C. Many exocytosed granules were found in the extracellular milieu adjacent to the activated MCs in IR-treated C57BL/6 mice (middle panel). These exocytosed granules were rarely seen in sham-treated C57BL/6 mice (left panel) or IR-treated C4−/− mice (right panel).

The C-derived peptides C3a and C5a are capable of eliciting activation and secretion of mediators from MCs (12–14), and both anaphylatoxins are generated during the formation of the membrane-attack complex C5b-9. C5a has been implicated in IR-induced injury of the kidneys (30). However, when we evaluated strains that lacked one of the anaphylatoxin receptors, either C3aR or C5aR, the extent of MC degranulation and muscle injury was comparable to that of their wild-type littermates (Fig. 2 and Table I). These unexpected findings suggest either that C3aR and C5aR have redundant activities or that the MCs are activated via another C-dependent mechanism.

Table I. IR-induced muscle injury and MC degranulation in mice deficient in C3aR and C5aR compared to their wild-type controls.

| Mouse Strain | Muscle Injurya | No. of Intact MCb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR treated | Sham treated | IR treated | Sham treated | |

| C3aR−/− | 42.3 ± 2.5 | 2.0 ±1.0 | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 19.7 ± 2.0 |

| BALB/c | 41.8 ± 1.4 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 16.8 ± 0.9 |

| C5aR−/− | 31.0 ± 4.5 | 2.0 ±1.0 | 6.5 ± 1.4 | 17.8 ± 0.9 |

| C57BL/6 | 23.3 ± 2.7 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 0.9 | 19.8 ± 0.7 |

Values are the mean number (±SEM) of injured muscle fibers (per 50 fc) quantitated histologically from: 8 C3aR−/− and 9 +/+ mice in the IR-treated groups with 3 and 4 shams, respectively; 12 C5aR−/− and 13 +/+ IR-treated mice with 5 and 6 shams, respectively.

Values are the mean number (±SEM) of intact MCs per 20 LPF from the same animals.

Role of specific MC mediators in IR-induced muscle injury

Mouse MCs elaborate numerous cytokines/chemokines, most of which are expressed 2–6 h after cellular activation in vitro. In our time course study (Fig. 1), substantial muscle damage was apparent after 1 h of reperfusion, suggesting little opportunity for transiently induced cytokines and chemokines to play a significant role. However, because some populations of mouse MCs store small amounts of preformed TNF-α in their secretory granules (31), we evaluated IR injury in a mouse strain unable to express this cytokine and determined that muscle injury was not attenuated (5 mice, n = 1, data not shown).

The cysteinyl leukotrienes are permeability-enhancing mediators, and mice lacking LTC4S do not exhibit increases in MC- and macrophage-dependent microvascular permeability (23, 32). PGD2 is the other prominent eicosanoid released from activated MCs, and this arachidonic acid metabolite also increases microvascular permeability (33). IR-induced muscle-cell damage in LTC4S- and hemopoietic PGD2S-null mice was found to be comparable to that in wild-type mice (Fig. 2 and Table II). Thus, the two most prominent eicosanoids generated from MCs do not contribute significantly to MC-dependent IR-mediated skeletal muscle damage.

Table II. IR-induced muscle injury and MC degranulation in mice deficient in LTC4S, PGD2S, and mMCP-1 compared to their wild-type controls.

| Mouse Strain | Muscle Injurya | No. of Intact MCb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR treated | Sham treated | IR treated | Sham treated | |

| LTC4S−/− | 42.0 ± 0.6 | 0 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 21 |

| C57BL/6 | 40.7 ±1.2 | 0 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 22 |

| PGD2S−/− | 36.0 ± 4.0 | 2.0 ± 2.0 | 4.3 ± 0.9 | 19.5 ± 1.5 |

| C57BL/6 | 23.8 ± 4.4 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 10.0 ± 1.1 | 21.5 ±1.5 |

| mMCP-1−/− | 21.4 ±1.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 12.6 ± 1.5 | 23.5 ± 2.5 |

| BALB/c | 17.3 ± 0.9 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 13.0 ± 2.5 | 22.0 ±3.0 |

Values are the mean number (±SEM or one-half range for two animals) of injured muscle fibers (per 50 fc) quantitated histologically from: 3 LTC4S −/− and 3 +/+ mice in the IR-treated groups with 1 sham from each strain; 4 PGD2S−/− and 4 +/+ IR-treated mice with 2 shams each; 5 mMCP-1 −/− and 5 +/+ IR-treated mice with 2 shams each.

Values are the mean number (±SEM or one-half range for two animals) of intact MCs per 20 LPF from the same animals.

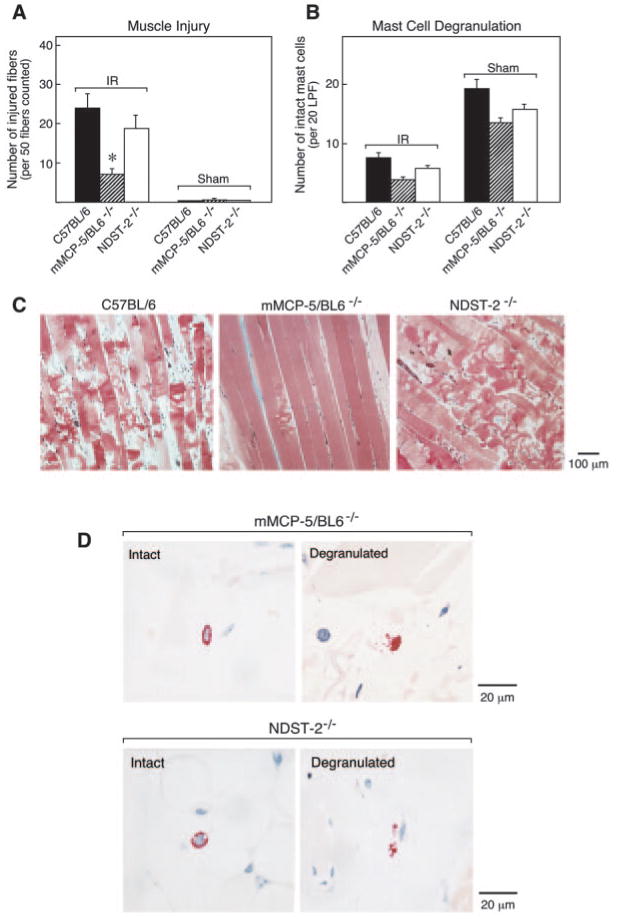

A defining characteristic of the constitutive MCs in skeletal muscle are the macromolecular complexes in their secretory granules that consist of negatively charged serglycin proteoglycans ionically bound to positively charged proteases (34). Heparin glycosaminoglycan is a major constituent of the serglycin proteoglycans stored in the granules of all safranin-positive MCs, including those in skeletal muscle. Because NDST-2 is essential for heparin biosynthesis (35), the MCs in NDST-2-null mice lack fully sulfated heparin proteoglycans in their secretory granules, which in turn leads to diminished storage but not total loss of the proteases of the MC granules (20, 36, 37). After hind limb IR, the degree of muscle injury in NDST-2-null mice was negligibly reduced relative to that in wild-type mice (Figs. 2 and 4). Thus, the heparin proteoglycans of the MC do not play a direct role in the elicitation of hind limb IR injury.

FIGURE 4.

IR-induced muscle damage and MC degranulation in mMCP-5/BL6−/− and in NDST-2−/− mice. A, The mean number (±SEM) of injured muscle fibers per 50 fc is shown for 11 IR-treated C57BL/6 mice, 12 IR-treated mMCP-5/BL6−/− mice, 6 IR-treated NDST-2−/− mice, 8 sham-treated C57BL/6 mice, 8 sham-treated mMCP-5/BL6−/− mice, and 3 sham-treated NDST-2−/− mice (*, p < 0.01). B, The mean number (±SEM) of intact MCs per 20 LPF were quantitated for each group. C, Representative histological sections from IR-treated C57BL/6 (left panel), mMCP-5/BL6−/− (middle panel), and NDST-2−/− (right panel) mice are shown. Extensive muscle damage (including rhabdomyolysis) occurs in IR-treated C57BL/6 mice and NDST-2−/− mice but not in mMCP-5/BL6−/− mice. D, High-power magnification fields of the chloroacetate esterase-positive MCs in the muscle of the mMCP-5/BL6−/− and NDST-2−/− mice. Many exocytosed granules were found in the extracellular milieu adjacent to the activated MCs in IR-treated mMCP-5/BL6−/− mice and NDST-2−/− mice but not in their sham-treated controls.

Based on the rapid time frame associated with IR injury, the MC-derived mediators most likely involved are the preformed secretory granule proteases. The MCs that reside in the muscles of BALB/c mice express mMCP-5 and mMCP-7, but not mouse transmembrane tryptase (mTMT)/tryptase γ/Prss31 (38). The MCs in the C57BL/6 mouse are unable to express mMCP-7 because of a point mutation in the exon 2/intron 2 splice site of this tryptase gene (39). In contrast, the levels of mTMT are markedly increased in the MCs of this mouse strain relative to those in BALB/c mice (38). The similarity in the extent of hind limb IR injury in the BALB/c and C57BL/6 mouse strains (Fig. 2) implies that neither mMCP-7 nor mTMT is the primary MC-derived factor that mediates muscle injury. Because we previously observed that some intra-alveolar macrophages are coated with immunoreactive mMCP-1 in our hind limb IR model (4), we considered the possibility that mMCP-1 released from mucosal MCs could exert its effects at a distant site such as the muscle. The extent of muscle injury and MC activation-secretion in mMCP-1-null mice was comparable to that in wild-type mice (Fig. 2 and Table II). Thus, mMCP-1 is not the relevant factor.

Of the remaining mMCP candidates, mMCP-5 is the most abundant serine protease in every safranin-positive mouse MC examined to date (40). After IR treatment of wild-type and mMCP-5/BL6−/− mice, mean muscle injury was 48 ± 4.7% and 15.6 ± 2.1% (mean ± SEM, n = 4, p < 0.01), respectively, for a reduction in injury of 68% (Figs. 2 and 4), even though MC degranulation was comparable (63 ± 7.5% and 73 ± 10%, respectively). To exclude other defects that may have occurred during development of this mMCP-5-null mouse strain, we also examined a second mMCP-5-null strain produced from an independently derived embryonic stem cell clone and backcrossed onto the BALB/c genetic background. These mice also showed dramatic protection against muscle injury; mean injury in the BALB/c controls was 60 ± 3.3% (mean ± SEM, 12 mice, 2 experiments) while the mean injury in the 5 mMCP-5/BALB−/− mice was 19.4 ± 3.1% (p < 0.001) for a reduction in injury of 68% (Fig. 2). MC degranulation was comparable, 74.3 and 75.7%, respectively. The extent of muscle injury relative to MC degranulation in the two mMCP-5-null strains was well below the trend line for all other strains and fell outside of the 95% confidence interval for this analysis (Fig. 2). Excluding mMCP-5, the correlation coefficient for the trend line including all of the normal mice and transgenic strains with targeted deletions tested was R2 = 0.83.

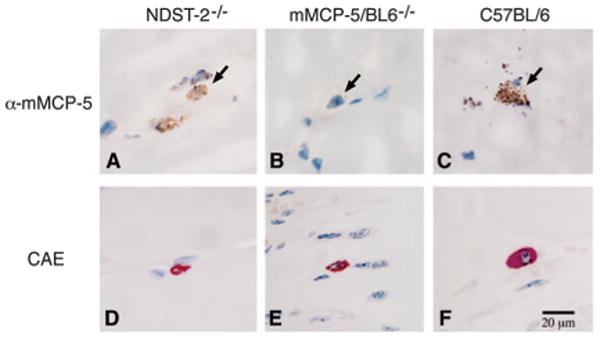

The normal IR injury in the NDST-2 null mice that still transcribe the gene but are deficient in granule-stored mMCP-5 implies that the NDST-2 null MC could still be providing the protease needed for the injury. Frozen sections of skeletal muscle, immunohistochemically evaluated for the presence of mMCP-5, showed a diffuse staining pattern associated with the MCs of the NDST-2−/− mice (Fig. 5A). No mMCP-5 was detectable in the MCs of mMCP-5/BL6−/− mice (Fig. 5B) and a distinct granule staining pattern was associated with the skeletal muscle MC in wild-type C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 5C). The chloroacetate esterase reactivity demonstrates the smaller size of the MCs found in the skeletal muscle of these two null strains (Fig. 5, D and 5, E) as compared with the MCs in the wild-type strain (Fig. 5F). The chloroacetate esterase activity in MCs of the two null strains is attributed to the presence of mMCP-4 that has been detected by activity in another NDST-2−/− strain (36) and by immunoblot analysis in peritoneal MCs from the mMCP-5/BL6−/− mice (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Immunohistochemical detection of mMCP-5 in NDST-2−/− and in C57BL/6 mice but not in mMCP-5/BL6−/− mice. A–C, The presence or absence of mMCP-5 in MCs was evaluated in frozen sections of skeletal muscle from NDST-2−/− (A), mMCP-5/BL6−/− (B), or wild-type C57BL/6 (C) mice using anti-mMCP-5. MCs are indicted by arrowheads. D–F, The size of the skeletal muscle MCs in the various mouse strains was compared using chloroacetate esterase (CAE) reactivity to identify the cells in paraformaldehyde-fixed sections of skeletal muscle from NDST-2−/− (D), mMCP-5/BL6−/− (E), or wild-type C57BL/6 (F) mice.

Discussion

We have identified a cytotoxic function for one MC granule protease in IR injury of mouse skeletal muscle. We made this observation while establishing that MCs participate quantitatively with natural IgM and C in producing IR injury of hind limb skeletal muscle of the mouse. The results demonstrate that the prominent MC secretory granule protease mMCP-5 is essential for the occurrence of irreversible muscle damage and that its release depends on classical C activation. The extensive skeletal muscle injury with local MC activation during IR contrasts with the absence of severe local cellular injury after conventional MC activation through receptors such as FcεRI, FcγRIII, or c-kit.

These studies extend earlier results that implicated the MCs in hind limb IR by demonstrating protection against injury in MC-deficient Wf/Wf and W/Wv mouse strains (3–5). The most recent assessment by Bortolotto et al. (5) demonstrated that reconstitution of the skeletal muscle with <10% of the normal number of MCs was able to restore 85% of the injury observed in the wild-type controls. Yet, the genetic abnormality of the receptor tyrosine kinase c-kit in these strains not only prevents survival of peripheral tissue MCs but also creates deficiencies in other hemopoietic lineages, such as erythrocytes and neutrophils, as well as affects mel-anogenesis and gametogenesis (17–19, 41–43). Thus, our results confirm the role of the MC in a mouse strain with normal hemopoietic lineage development and demonstrate the critical role of the MC proteases by identifying a requirement for a specific MC function through targeted disruption of a MC-specific gene.

The role of the local MCs in producing irreversible skeletal muscle injury was suggested by time-dependent studies in which a quantitative progression of cell injury was associated with an incremental reduction of intact MCs at the lesion (Fig. 1) and not in adjacent unaffected skeletal muscle (data not shown). This interpretation is supported by an analysis of the percentage of injured muscle fibers and the percentage of degranulated MCs in the same muscle (Fig. 2). The percentage of injured skeletal muscle fibers is directly correlated with the percentage of degranulated MCs in the injury site with a correlation coefficient of 0.85, indicating that 85% of the muscle injury is directly correlated with MC activation. Analysis of the various null mutant mice shows that with the exception of the mMCP-5-null mice, values from the other transgenic animals evaluated in our study lie near the linear trend line for the comparison of skeletal muscle injury and loss of intact MCs obtained from injured +/+ control mice. The skeletal muscle MCs of both the mMCP-5- and NDST-2-null strains have small granules due to the absence of core components of the secretory granule complex and a concomitant small cell size (Fig. 5). Trichinella spiralis infection in each of the strains elicits mucosal MCs in normal numbers and size, indicating that lineage development is normal and that the small size of the skeletal muscle MC only reflects the decrease in granule constituents (Ref. 20 and R. L. Stevens, unpublished data). Nonetheless, they can be enumerated and assessed for exocytosis with chloroacetate esterase staining in both resting and injured skeletal muscle (Figs. 4 and 5). Importantly, both possessed virtually the same number of MCs per 20 LPF in their hind limb skeletal muscle and responded to IR with comparable levels of degranulation. Yet the mMCP-5 null mice experienced minimal skeletal muscle injury, whereas the NDST-2 null mice were severely injured. The surprising finding that the degree of IR injury in the NDST-2-null mouse strain is similar to that in wild-type mice suggests that the small amount of mMCP-5 detected by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 5) is sufficient for extensive muscle damage in this animal model. By analogy to the finding that heparin restricts the enzymatic activity of recombinant mMCP-6 (44) and purified rat MC protease-1 (45), it is possible that the absence of heparin in the NDST-2-null mouse results in a marked increase in the relative lytic activity of the small amount of mMCP-5. Despite their granule storage deficiency, the mMCP-5 gene is transcribed at a normal rate in the MCs of NDST-2-null mice (20). Thus, another possibility is that extensive muscle damage occurs in NDST-2-null mice because the constitutive release of mMCP-5 augments the response of the tissue to other factors active in hind limb IR injury. Because the NDST-2-null mouse also has less MC carboxypeptidase A (20, 36, 37, 46), any role for this exopeptidase acting in concert with mMCP-5 would again depend on the lack of heparin binding.

The fact that this MC-dependent cytotoxicity occurs in a setting of IR with C activation preceding degranulation argues for a critical combination of events, including binding of natural IgM, which leads to activation of C and then MCs. The critical role of mMCP-5 in this setting may be operative via several different mechanisms. The protease might directly activate a pronecrotic pathway or inactivate an antinecrotic pathway outside the muscle cell or inside the cell if it is able to gain entry via the C5b-9 membrane pore. Alternately, mMCP-5 could activate a protease cascade that ultimately results in proteolytic disruption of the basement membrane, sarcolemma, the subsarcolemma cytoskeleton of skeletal muscle, or a factor that regulates the viability of the muscle cell. Whatever its mechanism, our findings demonstrate that irreversible skeletal muscle injury in IR-treated mice is exquisitely dependent on mMCP-5 and independent of several other MC-derived mediators.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM-52585, HL-36110, and HL-63284.

Abbreviations used in this paper: IR, ischemia-reperfusion; fc, fibers counted; LPF, low-power field; LTC4, leukotriene C4; LTC4S, LTC4 synthase; PGD2S, PGD2 synthase; MC, mast cell; mMCP, mouse MC protease; NDST, N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase; mTMT, mouse transmembrane tryptase.

Disclosures: The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Weiser MR, Williams JP, Moore FD, Jr, Kobzik L, Ma M, Hechtman HB, Carroll MC. Reperfusion injury of ischemic skeletal muscle is mediated by natural antibody and complement. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2343–2348. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyriakides C, Austen W, Jr, Wang Y, Favuzza J, Kobzik L, Moore FD, Jr, Hechtman HB. Skeletal muscle reperfusion injury is mediated by neutrophils and the complement membrane attack complex. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C1263–C1268. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.6.C1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazarus B, Messina A, Barker JE, Hurley JV, Romeo R, Morrison WA, Knight KR. The role of mast cells in ischaemia-reperfusion injury in murine skeletal muscle. J Pathol. 2000;191:443–448. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH666>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukundan C, Gurish MF, Austen KF, Hechtman HB, Friend DS. Mast cell mediation of muscle and pulmonary injury following hindlimb ischemia-reperfusion. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:1055–1056. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bortolotto SK, Morrison WA, Han X, Messina A. Mast cells play a pivotal role in ischaemia reperfusion injury to skeletal muscles. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1103–1111. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz HR, Raizman MB, Gartner CS, Scott HC, Benson AC, Austen KF. Secretory granule mediator release and generation of oxidative metabolites of arachidonic acid via Fc-IgG receptor bridging in mouse mast cells. J Immunol. 1992;148:868–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levi-Schaffer F, Dayton ET, Austen KF, Hein A, Caulfield JP, Gravallese PM, Liu FT, Stevens RL. Mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells cocultured with fibroblasts: morphology and stimulation-induced release of histamine, leukotriene B4, leukotriene C4, and prostaglandin D2. J Immunol. 1987;139:3431–3441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plaut M, Pierce JH, Watson CJ, Hanley-Hyde J, Nordan RP, Paul WE. Mast cell lines produce lymphokines in response to cross-linkage of FcεRI or to calcium ionophores. Nature. 1989;339:64–67. doi: 10.1038/339064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burd PR, Rogers HW, Gordon JR, Martin CA, Jayaraman S, Wilson SD, Dvorak AM, Galli SJ, Dorf ME. Interleukin 3-dependent and -independent mast cells stimulated with IgE and antigen express multiple cytokines. J Exp Med. 1989;170:245–257. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyajima I, Dombrowicz D, Martin TR, Ravetch JV, Kinet JP, Galli SJ. Systemic anaphylaxis in the mouse can be mediated largely through IgG1 and FcγRIII: assessment of the cardiopulmonary changes, mast cell degranulation, and death associated with active or IgE- or IgG1-dependent passive anaphylaxis. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:901–914. doi: 10.1172/JCI119255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dombrowicz D, Flamand V, Miyajima I, Ravetch JV, Galli SJ, Kinet JP. Absence of FcεRIα chain results in upregulation of FcγRIII-dependent mast cell degranulation and anaphylaxis: evidence of competition between FcεRI and FcγRIII for limiting amounts of FcRβ and γ chains. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:915–925. doi: 10.1172/JCI119256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim HW, He D, Esquenazi-Behar S, Yancey KB, Soter NA. C5a, cutaneous mast cells, and inflammation: in vitro and in vivo studies in a murine model. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:305–311. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12480568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson AR, Hugli TE, Muller-Eberhard HJ. Release of histamine from rat mast cells by the complement peptides C3a and C5a. Immunology. 1975;28:1067. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.el Lati SG, Dahinden CA, Church MK. Complement peptides C3a- and C5a-induced mediator release from dissociated human skin mast cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:803–806. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12378589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerniway RJ, Yang Z, Jacobson MA, Linden J, Matherne GP. Targeted deletion of A3 adenosine receptors improves tolerance to ischemia-reperfusion injury in mouse myocardium. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:H1751–H1758. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.4.H1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong H, Shlykov SG, Molina JG, Sanborn BM, Jacobson MA, Tilley SL, Blackburn MR. Activation of murine lung mast cells by the adenosine A3 receptor. J Immunol. 2003;171:338–345. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell ES. Hereditary anemias of the mouse: a review for geneticists. Adv Genet. 1979;20:357–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitamura Y, Go S, Hatanaka K. Decrease of mast cells in W/Wv mice and their increase by bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1978;52:447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernstein A, Chabot B, Dubreuil P, Reith A, Nocka K, Majumder S, Ray P, Besmer P. The mouse W/c-kit locus. Ciba Found Symp. 1990;148:158–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humphries DE, Wong GW, Friend DS, Gurish MF, Qiu WT, Huang C, Sharpe AH, Stevens RL. Heparin is essential for the storage of specific granule proteases in mast cells. Nature. 1999;400:769–772. doi: 10.1038/23481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopken UE, Lu B, Gerard NP, Gerard C. The C5a chemoattractant receptor mediates mucosal defence to infection. Nature. 1996;383:86–89. doi: 10.1038/383086a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer MB, Ma M, Goerg S, Zhou X, Xia J, Finco O, Han S, Kelsoe G, Howard RG, Rothstein TL, et al. Regulation of the B cell response to T-dependent antigens by classical pathway complement. J Immunol. 1996;157:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanaoka Y, Maekawa A, Penrose JF, Austen KF, Lam BK. Attenuated zymosan-induced peritoneal vascular permeability and IgE-dependent passive cutaneous anaphylaxis in mice lacking leukotriene C4 synthase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22608–22613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knight PA, Wright SH, Lawrence CE, Paterson YY, Miller HR. Delayed expulsion of the nematode Trichinella spiralis in mice lacking the mucosal mast cell-specific granule chymase, mouse mast cell protease-1. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1849–1856. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humbles AA, Lu B, Nilsson CA, Lilly C, Israel E, Fujiwara Y, Gerard NP, Gerard C. A role for the C3a anaphylatoxin receptor in the effector phase of asthma. Nature. 2000;406:998–1001. doi: 10.1038/35023175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNeil HP, Austen KF, Somerville LL, Gurish MF, Stevens RL. Molecular cloning of the mouse mast cell protease 5 gene: a novel secretory granule protease expressed early in the differentiation of serosal mast cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20316–20333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens RL, Qui D, McNeil HP, Friend DS, Hunt JE, Austen KF, Zhang J. Transgenic mice that possess a disrupted mast cell protease 5 gene cannot store carboxypeptidase A in their granules. FASEB J. 1996;10:1307. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ervasti JM. Costameres: the Achilles' heel of Herculean muscle. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13591–13594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNeil HP, Frenkel DP, Austen KF, Friend DS, Stevens RL. Translation and granule localization of mouse mast cell protease 5: immunodetection with specific antipeptide Ig. J Immunol. 1992;149:2466–2472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Vries B, Kohl J, Leclercq WK, Wolfs TG, van Bijnen AA, Heeringa P, Buurman WA. Complement factor C5a mediates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury independent from neutrophils. J Immunol. 2003;170:3883–3889. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon JR, Galli SJ. Release of both preformed and newly synthesized TNF-α/cachectin by mouse mast cells stimulated via FcεRI: a mechanism for the sustained action of mast cell-derived TNF-α during IgE-dependent biological responses. J Exp Med. 1991;174:103–107. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolaczkowska E, Shahzidi S, Seljelid R, van Rooijen N, Plytycz B. Early vascular permeability in murine experimental peritonitis is co-mediated by resident peritoneal macrophages and mast cells: crucial involvement of macrophage-derived cysteinyl-leukotrienes. Inflammation. 2002;26:61–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1014837110735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis RA, Soter NA, Diamond PT, Austen KF, Oates JA, Roberts LJ. Prostaglandin D2 generation after activation of rat and human mast cells with anti-IgE. J Immunol. 1982;129:1627–1631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens RL, Wong GW, Humphries DE. Serglycin proteoglycans: the family of proteoglycans stored in the secretory granules of certain effector cells of the immune system. In: Iozzo RV, editor. Proteoglycans: Structure, Biology, and Molecular Interactions. Dekker; New York: 2000. pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eriksson I, Sandback D, Ek B, Lindahl U, Kjellén L. cDNA cloning and sequencing of mouse mastocytoma glucosaminyl N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase, an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of heparin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10438–10443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lundequist A, Tchougounova E, Abrink M, Pejler G. Cooperation between mast cell carboxypeptidase A and the chymase mouse mast cell protease 4 in the formation and degradation of angiotensin II. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32339–32344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forsberg E, Pejler G, Ringvall M, Lunderius C, Tomasini-Johansson B, Kusche-Gullberg M, Eriksson I, Ledin J, Hellman L, Kjellen L. Abnormal mast cells in mice deficient in a heparin-synthesizing enzyme. Nature. 1999;400:773–776. doi: 10.1038/23488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong GW, Tang Y, Feyfant E, Sali A, Li L, Li Y, Huang C, Friend DS, Krilis SA, Stevens RL. Identification of a new member of the tryptase family of mouse and human mast cell proteases that possesses a novel C-terminal hydrophobic extension. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30784–30793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hunt JE, Stevens RL, Austen KF, Zhang J, Xia Z, Ghildyal N. Natural disruption of the mouse mast cell protease 7 gene in the C57BL/6 mouse. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2851–2855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reynolds DS, Stevens RL, Lane WS, Carr MH, Austen KF, Serafin WE. Different mouse mast cell populations express various combinations of at least six distinct mast cell serine proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3230–3234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gurish MF, Tao H, Abonia JP, Arya A, Friend DS, Parker CM, Austen KF. Intestinal mast cell progenitors require CD49dβ7 (α4β7 integrin) for tissue-specific homing. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1243–1252. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.9.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sonoda T, Hayashi C, Kitamura Y, Nakano T, Bessho M, Hirashima K, Miyazaki E, Hara H. Poor response of Wv/Wx mice to a grafted neutrophilia-inducing, colony-stimulating-factor-producing tumor. Exp Hematol. 1984;12:850–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cynshi O, Satoh K, Shimonaka Y, Hattori K, Nomura H, Imai N, Hirashima K. Reduced response to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in W/Wv and Sl/Sld mice. Leukemia. 1991;5:75–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang C, Friend DS, Qiu WT, Wong GW, Morales G, Hunt J, Stevens RL. Induction of a selective and persistent extravasation of neutrophils into the peritoneal cavity by tryptase mouse mast cell protease 6. J Immunol. 1998;160:1910–1919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Trong H, Neurath H, Woodbury RG. Substrate specificity of the chymotrypsin-like protease in secretory granules isolated from rat mast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:364–367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Henningsson F, Ledin J, Lunderius C, Wilen M, Hellman L, Pejler G. Altered storage of proteases in mast cells from mice lacking heparin: a possible role for heparin in carboxypeptidase A processing. Biol Chem. 2002;383:793–801. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]