Abstract

Objectives

Early hospital readmission is a common and costly problem in the Medicare population. In 2009, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services began mandating hospital reporting of disease-specific readmission rates. We sought to determine the rate and predictors of readmission after colectomy for cancer, as well as the association between readmission and mortality.

Methods

Medicare beneficiaries who underwent colectomy for stage I-III colon adenocarcinoma from 1992–2002 were identified from the SEER-Medicare database. Multivariate logistic regression identified predictors of early readmission and one-year mortality. Odds ratios were adjusted for multiple factors, including measures of comorbidity, socioeconomic status, and disease severity.

Results

Of 42,348 patients who were discharged, 4,662 (11.0%) were readmitted within 30 days. The most common causes of rehospitalization were ileus/obstruction and infection. Significant predictors of readmission included male gender, comorbidity, emergent admission, prolonged hospital stay, blood transfusion, ostomy, and discharge to nursing home. Readmission was inversely associated with hospital procedure volume, but not surgeon volume. After adjusting for potential confounding variables, the predicted probability of one-year mortality was 16% for readmitted patients, compared to 7% for those not readmitted. This difference in mortality was significant for all stages of cancer.

Conclusions

Early readmission after colectomy for cancer is common and due in part to modifiable factors. There is a remarkable association between readmission and one-year mortality. Early readmission is therefore an important quality-of-care indicator for colon cancer surgery. These findings may facilitate the development of targeted interventions that will decrease readmissions and improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: Colon Cancer, Surgery, Colectomy, Readmission, Rehospitalization, Mortality, Hospital Discharge, Risk Factors, Outcomes

Introduction

Early hospital readmissions are common and costly. In the Medicare population, almost 20% of hospital stays are followed by readmission within 30 days. Unplanned rehospitalizations led to an estimated $17.4 billion in Medicare expenditures in 2004. 1 Some early readmissions are due to factors such as patient frailty or progression of disease, but others are the result of poor quality care and are preventable.2 While investigators have reported population-based readmission rates for older adults with a variety of diagnoses,1, 3–5 the rate and causes of readmission after surgery for colon cancer, a common malignancy in the Medicare population, are unknown. The current study addresses this gap in the literature. Using population-level data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database, we determined the rate of early readmission after colectomy for colon adenocarcinoma and identified patient-, disease-, and treatment-related risk factors for readmission. We also examined the relationship between early readmission and one-year mortality. An understanding of the frequency, causes, and consequences of rehospitalization may facilitate the development of interventions that will decrease readmissions, thereby potentially improving patient outcomes and reducing health care expenditures.

Methods

This study was prospectively reviewed by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB) and determined to be exempt under Code of Federal Regulations Title 45 Part 46.101(b)(4).

Data Sources

We examined records from the SEER-Medicare database for patients diagnosed with colon cancer in the years 1992–2002. The SEER program of cancer registries collects information about patient demographics, tumor characteristics, first course of treatment, and survival for persons newly diagnosed with cancer. For people who are Medicare eligible, the SEER-Medicare database includes claims for covered health care services, including hospital, physician, outpatient, home health, and hospice bills. The linkage of persons in the SEER data to their Medicare claims is performed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The SEER-Medicare dataset has successfully linked 93% of individuals over age 65 at diagnosis to their Medicare record.6, 7 SEER registries from 1992–2002 contain incident cancer diagnoses in the following cities, states, and regions: Los Angeles, San Francisco-Oakland, San Jose-Monterey, Greater California, Connecticut, Detroit, Atlanta, Rural Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, New Mexico, Seattle-Puget Sound, and Utah. In 2000, SEER regions included approximately 26% of the United States population. 7

Patients

All Medicare-enrolled patients aged 66 years and older diagnosed with primary colon adenocarcinoma in a SEER area from 1992 to 2002 were evaluated for inclusion in the study. Included patients had a diagnosis of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage I to III colon (SEER cancer site codes 18.0–18.9, and 19.9) adenocarcinoma (SEER histology codes 8140-47, 8210-11, 8220-21, 8260-63, 8480-81, and 8490). Patients with mucinous cystadenocarcinoma (histology code 8470) were excluded because the natural history of this disease, which occurs in the appendix and is associated with pseudomyxoma peritoneii, is different than other histological subtypes of colon adenocarcinoma.8 We also excluded patients with rectal cancer because the surgical treatment of rectal cancer (e.g., abdominoperineal resection with permanent colostomy) is different from that of colon cancer, is often more technically challenging, and may be associated with a higher rate of complications. Patients were required to be continuously enrolled in parts A and B of fee-for-service Medicare for the twelve months preceding cancer diagnosis to ascertain comorbidity, and for an additional two months after surgical discharge or until death to enable capture of early readmissions. Patients enrolled in health maintenance organizations (HMOs) were excluded. We included patients who underwent primary tumor resection, corresponding to International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) procedure 45.7X (partial excision of large intestine) and 45.8X (total intra-abdominal colectomy). We excluded patients if they did not undergo tumor resection within six months of diagnosis. Patients were also excluded if they were diagnosed with another malignancy one year before or after the date of colon cancer diagnosis, or if their first diagnosis of colon cancer was made after death (i.e., on autopsy).

Outcome Variable

The primary outcome measure was 30-day readmission. We used the 30-day interval because most preventable readmissions have been found to occur within one month of discharge.2, 9, 10 Readmission to any acute care hospital within 30 days of discharge after colon cancer resection was designated as a 30-day readmission. Hospital-to-hospital transfers were not considered readmissions. Readmissions to psychiatric hospitals and rehabilitation facilities were also excluded. Readmission diagnoses were classified using Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Clinical Classifications Software (CCS).

A secondary outcome measure, mortality within one year of surgical discharge, was created based on dates of death recorded in the Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary File (PEDSF) according to Social Security administration data. Patients who died during the initial surgical hospital stay were excluded from the denominator in calculations of readmission rate and one-year mortality rate.

Predictor Variables

Information on date of birth, gender, marital status, and race/ethnicity were obtained from the SEER database. Census tract level median household income and median level of education were obtained from the PEDSF and used as proxies for patient socioeconomic status. Geographic region represented by SEER registry and rural/urban county of residence based on 2003 Rural/Urban Continuum Codes were also obtained from the PEDSF.

To measure comorbidity, we used CMS Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCCs)11 based on outpatient and inpatient diagnoses from the twelve months prior to colon cancer diagnosis. We also recorded the number of hospitalizations for each individual in the year prior to cancer diagnosis.

In addition to the patient-related variables described above, we measured a variety of disease-related variables. SEER data provided AJCC cancer stage and tumor grade. To allow adjustment for acuity of illness, we identified patients who presented with intestinal obstruction or perforation (ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 560.89 and 560.9, respectively), and those who were emergently admitted prior to colectomy.

Treatment-related predictor variables in our analysis included length of hospital stay, perioperative blood transfusion, creation of an ileostomy or colostomy during the operation, receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy within 30 days of surgical discharge, discharge destination, in-hospital complications, and surgeon and hospital procedure volume. Due to the inability of SEER-Medicare data to identify minor complications,12 we used the approach described by Morris and colleagues, in which only those complications that resulted in reoperation or other procedural intervention were recorded.13 Average annual procedure volume was determined using ICD-9 procedure codes for hospitals and CPT codes for surgeons, using the method previously described by Schrag, et al.14

Statistical Analysis

We determined the overall frequency of 30-day readmissions after colectomy for colon cancer. We compared the frequency of patient-related (age, gender, race/ethnicity, census-tract based income and education, SEER registry, urban/rural residence, hospitalization in the year prior to colon cancer surgery, HCC comorbidity score), disease-related (stage, grade, obstruction, perforation, emergent admission), and treatment-related (short or prolonged index hospitalization, hospital procedure volume, surgeon procedure volume, blood transfusion, ostomy, chemotherapy, perioperative complication, discharge destination) variables in patients who were and were not readmitted. We used logistic regression to analyze these data and determine adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of early hospital readmission after colectomy for cancer for different predictors, controlling for the other patient, disease, and treatment-related factors. We used logistic regression and Kaplan-Meier survival curves to quantify the association between 30-day readmission and one-year mortality for patients who survived beyond 30 days after discharge. Analyses were performed using SAS 8.02 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and Stata 10.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). All tests of significance were at the p < 0.05 level, and p-values were two-tailed.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 43,903 individuals met the inclusion criteria for the study. 1,555 patients (3.5%) died during the surgical hospital stay, and 42,348 patients were discharged alive. The mean age was 78 ± 6.9 years and 58.5% were female. Most patients were white, married, and residing in a major metropolitan area. Almost 26% of the patients in this sample were hospitalized in the year before surgery. The most frequent cancer stage was II (44.4%), followed by III (31.5%) and I (24.0%). The majority of tumors were moderately-differentiated. 17.4% of admissions were coded as emergent, and 5.7% of patients had either intestinal obstruction or perforation on admission. Table 1 displays frequencies for the other patient- and disease-related variables.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries discharged after colectomy for cancer (n = 42,348). Abbreviations: HCC, Hierarchical Condition Categories; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

| Characteristic | All Patients (n=42,348), % | Non- Readmitted (n=37,686), % | Readmitted (n=4,662), % | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-related | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 78.0 (6.9) | 77.8 (6.9) | 78.9 (7.1) | < 0.001 |

| Female gender | 58.5 | 58.9 | 55.5 | < 0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 86.3 | 86.5 | 84.9 | 0.021 |

| Black | 6.0 | 5.9 | 7.0 | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.4 | |

| Hispanic | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.4 | |

| Other | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| Marital status | 0.005 | |||

| Married | 49.9 | 50.2 | 47.4 | |

| Widowed | 35.6 | 35.4 | 37.4 | |

| Single, Separated, or Divorced | 11.2 | 11.1 | 11.6 | |

| Unknown | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.6 | |

| Median household income, $, mean (SD) | 38,477 (17,319) | 38,601 (17,400) | 37,445 (16,595) | < 0.001 |

| Less than 12y edu, %, mean (SD) | 20.3 (12.3) | 20.2 (12.3) | 21.2 (12.5) | < 0.001 |

| SEER Registry | < 0.001 | |||

| California | 28.5 | 28.7 | 27.2 | |

| Connecticut | 11.7 | 11.8 | 10.8 | |

| Detroit | 11.6 | 11.5 | 12.6 | |

| Hawaii | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.8 | |

| Iowa | 14.6 | 14.7 | 14.4 | |

| New Mexico | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.4 | |

| Seattle | 8.1 | 8.2 | 7.6 | |

| Utah | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.1 | |

| Atlanta & Rural Georgia | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.4 | |

| Kentucky | 3.4 | 3.4 | 4.2 | |

| Louisiana | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.7 | |

| New Jersey | 7.0 | 6.9 | 8.0 | |

| Residence location | 0.15 | |||

| Major metropolitan | 56.2 | 56.2 | 56.9 | |

| Metropolitan or urban | 33.7 | 33.9 | 32.6 | |

| Less urban or rural | 10.1 | 10.0 | 10.6 | |

| HCC comorbidity score, mean (SD) | 2.1 (1.4) | 2.1 (1.3) | 2.6 (1.5) | < 0.001 |

| Hospitalized in the year before surgery | 25.9 | 24.9 | 34.5 | < 0.001 |

| Disease-related | ||||

| Cancer stage | < 0.001 | |||

| I | 24.0 | 24.3 | 22.2 | |

| II | 44.4 | 44.4 | 44.4 | |

| III | 31.5 | 31.3 | 33.4 | |

| Tumor grade | 0.002 | |||

| Well-differentiated | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.2 | |

| Moderately-differentiated | 66.1 | 66.3 | 64.8 | |

| Poorly or undifferentiated | 20.6 | 20.4 | 22.5 | |

| Unknown | 4.2 | 4.2 | 3.6 | |

| Emergent admission | 17.4 | 16.7 | 23.4 | < 0.001 |

| Intestinal obstruction on admission | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 0.141 |

| Intestinal perforation on admission | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 0.002 |

| Treatment-related | ||||

| Year of surgery | ||||

| 1992–1995 | 30.9 | 31.3 | 27.5 | < 0.001 |

| 1996–1999 | 28.7 | 28.7 | 28.7 | |

| 2000–2002 * | 40.4 | 40.0 | 43.7 | |

| Hospital procedure volume | < 0.001 | |||

| 1st tertile (lowest volume) | 36.2 | 35.8 | 39.4 | |

| 2nd tertile | 31.3 | 21.4 | 30.0 | |

| 3rd tertile | 32.6 | 32.8 | 30.7 | |

| Surgeon procedure volume | 0.279 | |||

| 1st tertile (lowest volume) | 34.9 | 34.8 | 36.0 | |

| 2nd tertile | 35.5 | 35.5 | 35.1 | |

| 3rd tertile | 29.6 | 29.7 | 29.0 | |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.753 |

| Length of hospital stay, mean (SD) | 11.2 (6.9) | 11.0 (6.5) | 13.3 (9.0) | < 0.001 |

| Received blood transfusion | 17.5 | 16.9 | 21.9 | < 0.001 |

| Stoma | 8.3 | 8.0 | 11.0 | < 0.001 |

| In-hospital complication | 3.4 | 3.1 | 5.8 | < 0.001 |

| Discharge destination | ||||

| Home | 81.0 | 82.1 | 71.5 | < 0.001 |

| SNF | 17.3 | 16.3 | 25.8 | |

| Other facility ** | 1.7 | 1.6 | 2.8 | |

| Chemotherapy w/in 30d of discharge | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 0.806 |

Three SEER registries (Kentucky, Louisiana, and New Jersey) were added in 2000.

Other facility includes long-stay, psychiatric, and rehabilitation hospitals.

The median length of hospital stay was 9 days (interquartile range 7–13). 17.5% of patients received a perioperative blood transfusion. Less than 1% of operations were done laparoscopically. The rate of in-hospital complication requiring re-operation or other procedural intervention was 3.4%. The most frequent complications were organ injury (1.1%), abdominal infection (0.8%), and shock/hemorrhage (0.7%). Most patients (81.0%) were discharged home, and 17.3% were discharged to a skilled nursing facility. Only 5.7% of patients received chemotherapy within 30 days of discharge (Table 1).

Rate of Readmission

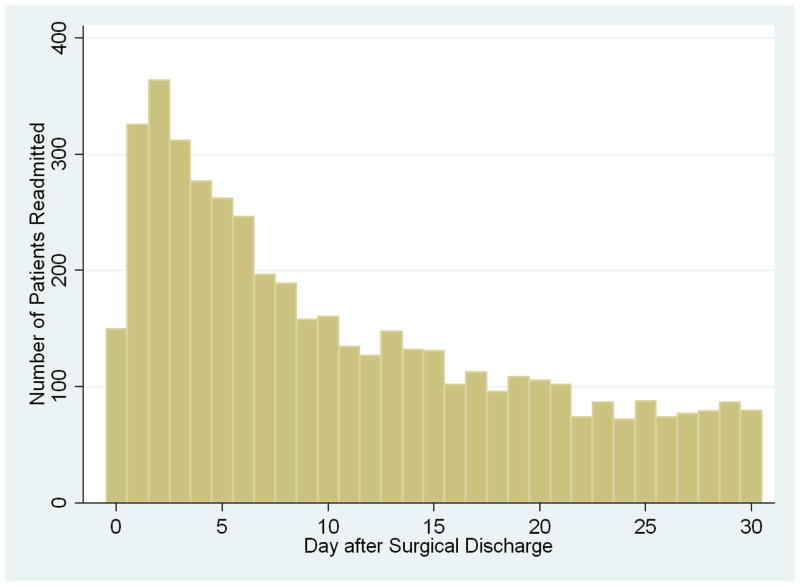

Of the 42,348 patients who were discharged alive after colectomy for cancer, 4,662 were rehospitalized within 30 days, yielding a readmission rate of 11.0%. The median day of readmission was post-discharge day nine (interquartile range 4–17). Figure 1 shows the distribution of the number of readmitted patients by post-discharge day. The curve is approximately exponential in shape, with the greatest number of readmissions occurring during the first few days after discharge and declining thereafter. The highest frequency of readmissions—364, or 7.8% of all 30-day readmissions—occurred on post-discharge day two. Of the 4,662 readmitted patients, 614 (13.2%) were readmitted to a hospital other than the one in which they underwent initial surgery. The median readmission length of stay was 5 days (interquartile range 3–9). The readmission in-hospital mortality rate was 6.5%.

FIGURE 1.

Frequency of hospital readmissions (n=4,662) by post-discharge day. Day zero is the day of surgical discharge.

Differences Between Readmitted and Non-Readmitted Patients

Prior to adjustment, there were statistically significant differences between the readmitted and non-readmitted groups for all independent variables other than rural/urban residence location, pre-operative bowel obstruction, surgeon procedure volume, laparoscopic versus open resection, and receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy within 30 days of discharge (Table 1). Compared to non-readmitted patients, the proportion of older individuals, males, and blacks were higher in the readmitted group. Readmitted patients had a lower median household income and a higher percentage of non-high school graduates in their census tract of residence. Readmitted patients also had a higher burden of comorbid disease as measured by HCC score. Rates of pre-operative bowel perforation and emergent operation were higher in readmitted patients. There was an association between surgery at a low-procedure volume hospital and subsequent readmission. Rehospitalized patients had a longer average length of hospital stay after surgery, and higher rates of perioperative blood transfusion, stoma creation, and post-operative in-hospital complications. Finally, readmitted patients were more likely to have been discharged to a skilled nursing facility rather than to home.

Causes of Readmission

The most common readmission diagnoses were ileus, obstruction, and other gastrointestinal complications (28.3%), followed by surgical site infection (7.6%), pneumonia and other respiratory complications (7.1%), bleeding and anemia (6.9%), and sepsis (5.1%, Table 2). The majority of rehospitalizations were coded as emergent (52%) or urgent (34%) admissions. The readmission hospital was different from the site of surgery in over 13% of readmission cases.

TABLE 2.

Readmission Diagnoses of 4662 Patients Readmitted After Colectomy for Cancer, Grouped by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) Codes.

| Readmission Diagnosis | Percent |

|---|---|

| Ileus, obstruction & other GI complications | 28.3 |

| Surgical site infection | 7.6 |

| Pneumonia & other respiratory complications | 7.1 |

| Bleeding & anemia | 6.9 |

| Sepsis | 5.1 |

| Fluid & electrolyte disorders | 5.0 |

| Congestive heart failure & pulmonary heart disease | 4.7 |

| Dehiscence & other surgical complications | 3.9 |

| Myocardial infarction & cardiac arrest | 3.8 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 3.1 |

Predictors of Readmission

Table 3 lists the adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of the independent variables for 30-day readmission as determined by logistic regression. Age was not a significant predictor of readmission. The odds ratio for males vs. females was 1.20 (95% CI 1.12–1.29), indicating that the odds of readmission were significantly higher for males. Patients with Asian or Pacific Islander race/ethnicity had higher odds of readmission than whites (OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.06–1.50). After adjustment, there was no statistically significant association between marital status and 30-day rehospitalization.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted odds ratios* for 30-day readmission and one-year mortality after colectomy for cancer. Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HCC, Hierarchical Condition Categories; SNF, skilled nursing facility. Statistically significant associations (p<0.05) are highlighted.

| Characteristic | OR for Readmission (95% CI) | OR for Mortality (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-related | ||

| Age | ||

| 66–70 | 1 | 1 |

| 71–75 | 0.94 (0.85—1.05) | 1.29 (1.13—1.47) |

| 76–80 | 1.00 (0.90—1.11) | 1.47 (1.29—1.67) |

| 81–85 | 1.04 (0.93—1.16) | 2.06 (1.81—2.35) |

| 86+ | 1.08 (0.96—1.21) | 2.70 (2.36—3.08) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 1.20 (1.12—1.29) | 1.21 (1.12—1.30) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 1 | 1 |

| Black | 1.08 (0.94—1.23) | 1.05 (0.91—1.21) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.26 (1.06—1.50) | 0.65 (0.52—0.81) |

| Hispanic | 1.13 (0.94—1.36) | 0.85 (0.70—1.04) |

| Other | 1.08 (0.64—1.82) | 0.48 (0.24—0.98) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1 | 1 |

| Widowed | 1.01 (0.93—1.09) | 1.05 (0.97—1.14) |

| Single, Separated, or Divorced | 1.00 (0.90—1.11) | 1.12 (1.00—1.24) |

| Unknown | 1.01 (0.85—1.21) | 1.08 (0.90—1.30) |

| SEER Registry | ||

| California | 1 | 1 |

| Connecticut | 1.06 (0.93—1.21) | 1.02 (0.89—1.17) |

| Detroit | 1.20 (1.07—1.36) | 1.05 (0.93—1.19) |

| Hawaii | 0.93 (0.71—1.23) | 0.85 (0.60—1.20) |

| Iowa | 1.17 (1.01—1.35) | 1.03 (0.88—1.20) |

| New Mexico | 1.00 (0.80—1.26) | 1.24 (0.99—1.56) |

| Seattle | 1.10 (0.96—1.26) | 1.19 (1.04—1.37) |

| Utah | 1.11 (0.90—1.37) | 1.19 (0.97—1.47) |

| Atlanta & Rural Georgia | 1.14 (0.96—1.34) | 1.16 (0.98—1.37) |

| Kentucky | 1.27 (1.05—1.54) | 1.43 (1.17—1.75) |

| Louisiana | 1.32 (1.08—1.60) | 0.99 (0.80—1.23) |

| New Jersey | 1.11 (0.96—1.29) | 0.80 (0.68—0.93) |

| Residence location | ||

| Major metropolitan | 1 | 1 |

| Metropolitan or urban | 0.99 (0.89—1.09) | 0.99 (0.90—1.10) |

| Less urban or rural | 0.99 (0.85—1.14) | 0.98 (0.84—1.14) |

| Hospitalized in the year before surgery | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.26 (1.18—1.36) | 1.16 (1.08—1.25) |

| HCC score | 1.14 (1.11—1.17) | 1.27 (1.24—1.30) |

| Disease-related | ||

| Cancer stage | ||

| I | 1 | 1 |

| II | 0.99 (0.91—1.08) | 1.23 (1.11—1.35) |

| III | 0.97 (0.88—1.06) | 2.50 (2.26—2.76) |

| Tumor grade | ||

| Well-differentiated | 1.07 (0.96—1.19) | 1.03 (0.91—1.17) |

| Moderately-differentiated | 1 | 1 |

| Poorly or undifferentiated | 1.10 (1.02—1.19) | 1.71 (1.59—1.84) |

| Unknown | 0.91 (0.77—1.08) | 1.14 (0.95—1.36) |

| Emergent admission | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.14 (1.05—1.24) | 1.17 (1.08—1.27)b |

| Intestinal obstruction on admission | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.91 (0.77—1.06) | 1.37 (1.19—1.57) |

| Intestinal perforation on admission | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.93 (0.75—1.15) | 1.47 (1.22—1.78) |

| Treatment-related | ||

| Year of surgery | ||

| 1992–1995 | 1 | 1 |

| 1996–1999 | 1.08 (1.00—1.18) | 0.93 (0.86—1.02) |

| 2000–2002 | 1.13 (1.02—1.24) | 0.97 (0.87—1.07) |

| Hospital procedure volume | ||

| 1st tertile (lowest volume) | 1 | 1 |

| 2nd tertile | 0.88 (0.81—0.95) | 0.92 (0.85—0.99) |

| 3rd tertile | 0.85 (0.78—0.92) | 0.80 (0.74—0.88) |

| Surgeon procedure volume | ||

| 1st tertile (lowest volume) | 1 | 1 |

| 2nd tertile | 1.02 (0.95—1.10) | 0.95 (0.88—1.03) |

| 3rd tertile | 1.05 (0.97—1.14) | 1.06 (0.97—1.15) |

| Laparoscopic surgery | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.16 (0.79—1.71) | 0.66 (0.38—1.15) |

| Length of hospital stay | ||

| Less than 6 days | 0.96 (0.82—1.12) | 0.82 (0.67—1.00) |

| 6–14 days | 1 | 1 |

| More than 14 days | 1.33 (1.23—1.45) | 1.70 (1.57—1.84) |

| Received blood transfusion | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.14 (1.06—1.24) | 1.21 (1.11—1.31) |

| Stoma | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.13 (1.01—1.25) | 1.30 (1.17—1.44) |

| In-hospital complication | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.42 (1.23—1.65) | 1.05 (0.90—1.23) |

| Discharge destination | ||

| Home | 1 | 1 |

| SNF | 1.34 (1.23—1.46) | 2.20 (2.03—2.38) |

| Other facility | 1.18 (0.95—1.45) | 2.38 (1.97—2.87) |

| Chemotherapy w/in 30d of discharge | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.99 (0.86—1.13) | 1.01 (0.88—1.16) |

| Readmitted within 30 days of discharge | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 2.44 (2.25—2.65) | |

Odds ratios are adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, census tract median household income and percent of non-high school graduates, SEER registry, rural/urban residence location, hospitalization in the year before surgery, Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCC) comorbidity score, tumor stage and grade, emergent admission, obstruction, perforation, year of surgery, hospital and surgeon procedure volume, laparoscopic vs. open resection, length of stay, blood transfusion, ostomy, in-hospital complication, discharge destination, and receipt of chemotherapy.

We observed regional variation in odds of 30-day readmission after colectomy for cancer. Compared to California, the SEER region that contributed the most patients to our sample, patients from Iowa (OR 1.17, 95% CI 1.01–1.35), Detroit (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.07–1.36), Kentucky (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.05–1.54), and Louisiana (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.08–1.60) had higher odds of readmission, after adjusting for other factors. However, rural or urban residence location was not significantly associated with readmission.

A history of hospitalization in the year prior to surgery was a significant predictor of readmission after colon cancer surgery (OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.18–1.36). Greater patient comorbidity as quantified by HCC score was also associated with rehospitalization (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.11–1.17).

Of the disease-related variables, emergent admission (OR 1.14, CI 1.05–1.24) and poorly-differentiated grade (OR 1.10, CI 1.02–1.19) were significantly associated with readmission. Cancer stage and intestinal obstruction/perforation were not significant predictors.

Several treatment-related variables were significant predictors of 30-day readmission. Prolonged length of hospital stay, defined as 15 days or more, was a predictor of subsequent readmission (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.23–1.45). Patients who received blood transfusions (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.06–1.24), underwent stoma creation (OR 1.13, CI 1.01–1.25), or experienced a post-operative complication (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.23–1.65) also had increased odds of early readmission. Compared to patients who went home after discharge, those who were transferred to a skilled nursing facility had greater odds of readmission (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.23–1.46). The year of surgery was also associated with rehospitalization status. Compared to patients who underwent surgery in 1992–1995, those who had surgery in 2000–2002 were more likely to be readmitted (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.02–1.24).

Association of Readmission with Mortality

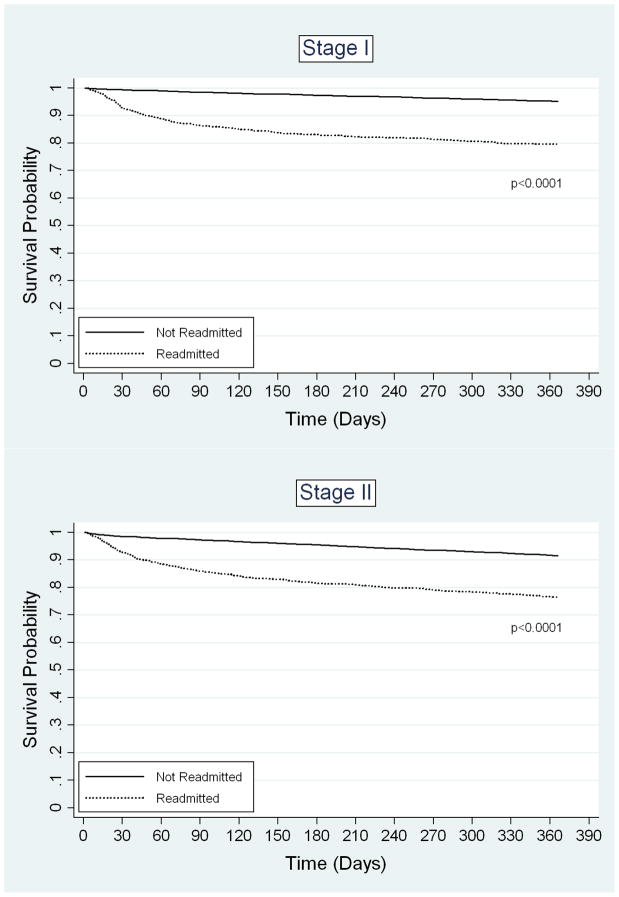

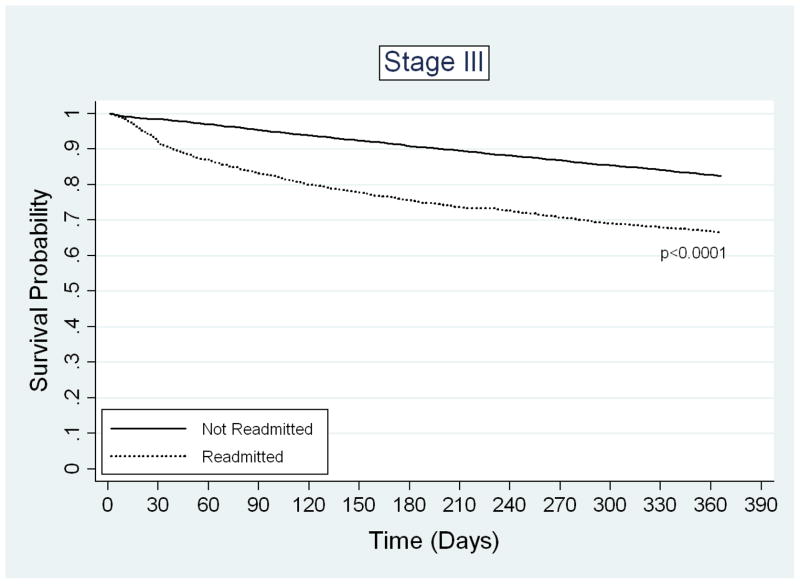

Readmission was strongly associated with increased one-year mortality. The unadjusted one-year mortality rate for readmitted patients was 26.6%, compared to 11.0% for non-readmitted patients (p-value < 0.0001). The adjusted odds ratio of one-year mortality for readmitted versus non-readmitted patients was 2.44 (95% CI 2.25–2.65). The magnitude of this association was comparable to the difference in one-year mortality between patients with stage III and stage I disease (OR 2.50, 95% CI 2.26–2.76) and patients older than 85 versus those aged 66–70 years (OR 2.70, 95% CI 2.36–3.08). Besides readmission, age, and stage, other significant predictors of death within one year of surgical discharge included male gender, hospitalization in the year before surgery, HCC score, tumor grade, emergent admission, bowel obstruction or perforation upon admission, length of hospital stay, blood transfusion, ostomy creation, and discharge destination other than home (Table 3). Interestingly, the majority of the variables that predicted early readmission were also significant predictors of one-year mortality. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated a significant difference in probability of one-year survival between readmitted and non-readmitted patients for all cancer stages (Figure 2). After adjustment for potential confounders, the predicted probabilities of one-year mortality were also significantly different between readmitted and non-readmitted patients (Table 4).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for patients who were not readmitted (37,686) or were readmitted (n=4,662) after colectomy for cancer. A) Stage I disease, B) Stage II disease, C) Stage III disease.

TABLE 4.

Adjusted predicted probabilities* and 95% CIs of 1-yr mortality after colectomy for cancer, by 30-day readmission status and cancer stage.

| % Mortality in Non-Readmitted Patients (n=37,686) | % Mortality in Readmitted Patients (n=4,662) | |

|---|---|---|

| All Patients (n=42,348) | 7.4 (7.1—7.7) | 16.3 (15.2—17.3) |

| Stage 1 Patients (n=10,181) | 3.0 (2.6—3.3) | 9.6 (7.9—11.2) |

| Stage 2 Patients (n=18,817) | 5.9 (5.5—6.3) | 14.1 (12.7—15.6) |

| Stage 3 Patients (n=13,350) | 15.1 (14.3—15.8) | 26.1 (23.8—28.3) |

Predicted probabilities are adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, census tract median household income and percent of non-high school graduates, SEER registry, rural/urban residence location, hospitalization in the year before surgery, Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCC) comorbidity score, tumor stage and grade, emergent admission, obstruction, perforation, year of surgery, hospital and surgeon procedure volume, laparoscopic vs. open resection, length of stay, blood transfusion, ostomy, in-hospital complication, discharge destination, and receipt of chemotherapy.

CI indicates confidence interval.

Discussion

Until recently, hospitals have had little financial incentive to minimize readmissions as Medicare pays for all hospitalizations based on the diagnosis, regardless of whether the admission is an initial hospital stay or a readmission.15 However, recent policy developments indicate that this culture is changing. In 2007, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC) proposed mandatory reporting of risk-adjusted readmission rates, with eventual penalties for hospitals with high rates.15 In 2009, CMS began requiring hospitals to report 30-day readmission rates for patients with several medical conditions.16 These increased reporting requirements may reflect the recognition that readmissions not only lead to increased health care utilization and expenditures, but are also often preventable. Because rehospitalization has clear links to health care costs and modifiable processes of inpatient care, health services researchers, policy makers, and payers have increasingly used readmission as a quality-of-care measure.2, 17, 18 Information on predictors of readmission are needed for the development of interventions that will decrease readmissions and improve patient outcomes.

Colon cancer is a cause of significant morbidity and mortality. 148,000 new cases of colorectal cancer are diagnosed annually in the United States.19 Surgical resection performed in the in-patient hospital setting is the standard of care for localized disease. Despite the high incidence of colon cancer and the frequency of surgical treatment, the rate and predictors of readmission after colon cancer surgery have not previously been systematically studied using population-level data. Previous studies have consisted of single-institution retrospective case series. In these reports, which have often combined patients with benign and malignant disease, readmission rates range widely, from zero to 27 percent.5, 20–36 Only one previous study, by Goodney and colleagues, was based on population-level data.5

In the current study we used the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked database to determine the rate, causes, and consequences of readmission after colectomy for cancer. We found that 11.0% of patients—almost one in nine—were readmitted within one month of discharge. Most readmissions occurred within the first 10 days after discharge.

The most common readmission diagnoses were ileus/obstruction and other gastrointestinal complications, surgical site infection, pneumonia and other respiratory complications, bleeding and anemia, and sepsis. After adjusting for other factors, significant predictors of 30-day readmission included male gender, Asian race, hospitalization in the prior year, comorbidity, emergent admission, low hospital procedure volume, prolonged length of hospital stay, perioperative blood transfusion, associated ostomy, post-operative complication requiring an additional procedure, and discharge to a skilled nursing facility. Furthermore, we found a striking association between 30-day readmission and one-year mortality, comparable to other well-established predictors of mortality such as old age and advanced cancer stage. Many of the variables that predicted readmission were also significantly associated with one-year mortality.

The SEER-Medicare database has several advantages for the study of readmission. It contains information on a wide array of patient-, disease-, and treatment-related factors. Results based on national-level SEER-Medicare data may be more generalizable to the population at large compared to findings from studies conducted at specialized academic medical centers. Importantly, SEER-Medicare allows the tracking of patients from one hospital to another. Therefore, we were able to detect readmissions to any hospital, not only readmissions to the hospital where the original surgery was performed. We found that over 13% of readmissions were to another hospital. Single-institution retrospective studies are likely to underestimate the rate of readmission. CMS and other payers should be cognizant of this risk of underestimation before implementing programs based on self-report by hospitals or providers.

The rate of rehospitalization in our study population was almost identical to the readmission rate of 11.1% calculated by Goodney and colleagues for patients with colon cancer treated with colectomy in their analysis of national Medicare data from 1994–1999.5 Higher population-based readmission rates have been reported for coronary artery bypass surgery and other complex cancer operations such as pneumonectomy, esophagectomy, and pancreatic resection.5, 37 In the year 2000, approximately 96,300 colon cancer resections were performed in the United States, and by 2020 this figure is predicted to increase to 141,100 operations.38 Clearly, a readmission rate of almost one-in-nine for patients undergoing this common procedure represents a significant problem from a clinical, public health, and health policy perspective.

We found that most readmissions after hospitalization for colon cancer surgery occurred on the day after discharge and shortly thereafter. The median day of readmission was post-discharge day nine. This is consistent with previous studies which have shown that hospital readmissions cluster shortly after discharge and then decline in frequency.2, 23, 32 Readmissions that occur soon after surgical discharge are likely to be related to surgical complications, poor discharge planning, or other modifiable factors.

Our study included an analysis of the reasons for readmission. The most common causes of readmission were ileus/obstruction and other gastrointestinal complications, surgical site infection, pneumonia and other respiratory complications, bleeding and anemia, and sepsis. These clinical entities are all potentially preventable complications of surgical care. Similarly, an analysis of coronary artery bypass graft surgery in New York found that 85% of readmissions were directly related to potentially preventable surgical complications.37 Our findings regarding the timing and causes of rehospitalization support the use of 30-day readmission as a quality-of-surgical-care indicator.

In their study on early readmissions in the Medicare program, Jencks and colleagues concluded that over 70% of readmissions after surgical discharges were due to “medical conditions”.1 However, in patients who underwent “major bowel surgery,” they reported the most frequent reasons for rehospitalization were “GI problems” (15.9%), postoperative infection (6.4%), “nutrition-related or metabolic issues” (5.6%), and GI obstruction (4.3%). Rather than medical conditions, we would characterize these readmission diagnoses as potentially preventable surgical complications, which is consistent with our findings regarding the causes of readmission after colectomy for cancer.

While numerous investigators have estimated the readmission rate after colorectal surgery, relatively few have identified predictors of readmission. In a prospective, multicenter study of 1,421 patients undergoing colorectal surgery in France, Guinier and colleagues identified five statistically significant predictors of readmission: surgical field contamination, long operative duration, need for an additional surgical procedure, low hemoglobin, and lack of air leak testing of the bowel anastomosis.31 Kiran and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic conducted a retrospective study to identify predictors of 30-day readmission after colorectal surgery for benign and malignant disease. They found two variables that were significantly associated with readmission: longer hospital stay and use of corticosteroids.32 In contrast to the French multicenter study, low discharge hemoglobin level was not a significant predictor of readmission. Another single-institution study by a group in Allentown, Pennsylvania, did not yield any significant predictors of rehospitalization after elective colorectal surgery, leading them to conclude, “readmissions after colorectal surgery cannot be predicted”.22 However, this study was limited by a relatively small sample size (n=249).

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to identify predictors of early readmission after colon cancer surgery in a population-based sample. Our multivariate analysis identified several significant predictors of readmission after colon cancer resection in this cohort of Medicare beneficiaries aged 66 and older. The odds of readmission were higher for males than females. Gonzalez and colleagues, in a prospective cohort study, also reported a significantly higher risk of readmission in men versus women treated for colorectal cancer in Spain.39 Similarly, in a study of Medicare beneficiaries who underwent surgical treatment of colorectal cancer, Morris et al. found an elevated relative risk of post-operative complications requiring procedural intervention in males compared to females.13 We adjusted for post-operative complication in our multivariate model, yet the increased odds of readmission for males persisted.

Black-white racial disparities in risk factors, screening, stage at diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes such as mortality have been extensively documented for colon cancer patients.40–45 Previous studies have also reported higher rates of readmission for African-Americans with stroke, diabetes mellitus, and asthma.46 After adjustment for socioeconomic and clinical factors, we did not observe a significant difference in odds of readmission for black vs. white patients after colectomy. Interestingly, compared to white patients, Asian patients had higher odds of readmission, but lower odds of one-year mortality.

Other significant predictors of readmission included hospitalization in the year prior to surgery, higher comorbidity score, emergent admission, in-hospital complication, blood transfusion, and prolonged length of stay. Short duration of surgical hospital stay was not associated with increased readmission. However, we did observe a statistically significant trend of increased readmissions in later years. Our study period precedes the widespread implementation of “fast track” colorectal surgery protocols, and relatively few patients in our sample were discharged after hospital stays of four days or less. Future analyses should examine the impact of fast track protocols and laparoscopic surgery on the national early readmission rate after colectomy for cancer.

We found that low hospital procedure volume, but not low surgeon procedure volume, was associated with increased readmission as well as increased one-year mortality. Similarly, in their study of outcomes after primary colon cancer surgery, Schrag and colleagues concluded that hospital volume exerted a stronger effect than surgeon volume.14 Goodney et al. also studied the association between hospital volume and readmission after colectomy for cancer in a Medicare population. They concluded that the association between hospital volume and readmission, while statistically significant, was not clinically meaningful.5 In our study the difference in readmission rates in low compared to high volume hospitals (12% for the lowest volume tertile versus 10% for the highest tertile) was small but clinically significant.

An important finding of our study is that readmission was associated with increased one-year mortality. A similar association between readmission and increased mortality has been reported for patients with lung cancer treated with pulmonary resection.47 Conversely, readmitted patients with pancreatic cancer who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy at Johns Hopkins actually had improved survival compared to patients who were not readmitted.48 In our study, the majority of factors that predicted readmission also predicted mortality. The observation that one-year mortality is higher for readmitted versus non-readmitted colon cancer surgery patients further supports the validity of readmission as a quality-of-care indicator.

Our study has several limitations. Because our study is limited to the Medicare population, the results may not apply to colon cancer patients younger than 65 years of age. However, the risk of colon cancer is known to increase with age, and the average age of diagnosis for patients with non-hereditary colon cancer is over 65 years.49 Also, because our study is based on claims data, we were unable to analyze clinical variables often used to assess “readiness for discharge,” such as patient symptoms, vital signs, laboratory values, bowel function, diet tolerance, and activity level. Claims data are also not well suited for the study of variables related to surgical technique, for example hand-sewn vs. stapled bowel anastomosis. Finally, other than marital status, our analysis did not include measures of social support, another factor that may influence the risk of readmission after surgery. It is likely that some of these factors which we did not measure are also important risk factors for early readmission after colectomy for cancer. Unmeasured factors may also be responsible in part for the observed association between readmission and one-year mortality.

Despite these limitations, this study has important implications. We have demonstrated that readmission after colon cancer surgery is common, readmissions cluster in the days immediately following discharge, and most causes of readmission are potentially preventable. This is the first study based on population-level data to identify multiple predictors of early readmission after colon cancer resection. While some significant predictors such as gender are not modifiable, others are related to structures and processes of care, such as hospital volume and blood transfusion. Importantly, our results show that early readmission is significantly associated with increased one-year mortality. Interestingly, many of the same variables that predicted readmission also predicted one-year mortality. We conclude that readmission is an important quality-of-care measure for colon cancer surgery. An understanding of the rate and predictors of readmission is a crucial first step in the process of developing targeted interventions that will reduce readmissions, decrease expenditures, and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carol Weidel, SAS programmer, for her assistance in preparing the data for analysis.

This project was supported by the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center (UWCCC) Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute - National Institutes of Health, grant number P30 CA014520-34. Additional support was provided by the Health Innovation Program and the Community-Academic Partnerships core of the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UW ICTR), grant 1UL1RR025011 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

This study used the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database. The collection of the California cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute’s SEER Program under contract N01-PC-35136 awarded to the Northern California Cancer Center, contract N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract N02-PC-15105 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement #U55/CCR921930-02 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

References

- 1.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benbassat J, Taragin M. Hospital readmissions as a measure of quality of health care: advantages and limitations. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1074–1081. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.8.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hennen J, Krumholz HM, Radford MJ, et al. Readmission rates, 30 days and 365 days postdischarge, among the 20 most frequent DRG groups, Medicare inpatients age 65 or older in Connecticut hospitals, fiscal years 1991, 1992, and 1993. Conn Med. 1995;59:263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei F, Mark D, Hartz A, et al. Are PRO discharge screens associated with postdischarge adverse outcomes? Health Serv Res. 1995;30:489–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodney PP, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, et al. Hospital volume, length of stay, and readmission rates in high-risk surgery. Ann Surg. 2003;238:161–167. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000081094.66659.c3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, et al. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Med Care. 1993;31:732–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40:IV-3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo NS, Sarr MG. Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the appendix. The controversy persists: a review. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:432–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frankl SE, Breeling JL, Goldman L. Preventability of emergent hospital readmission. Am J Med. 1991;90:667–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibbritt DW. Validation of a 28 day interval between discharge and readmission for emergency readmission rates. J Qual Clin Pract. 1995;15:211–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ash AS, Ellis RP, Pope GC, et al. Using diagnoses to describe populations and predict costs. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;21:7–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potosky AL, Warren JL, Riedel ER, et al. Measuring complications of cancer treatment using the SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002;40:IV-62–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris AM, Baldwin LM, Matthews B, et al. Reoperation as a quality indicator in colorectal surgery: a population-based analysis. Ann Surg. 2007;245:73–79. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000231797.37743.9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrag D, Panageas KS, Riedel E, et al. Surgeon volume compared to hospital volume as a predictor of outcome following primary colon cancer resection. J Surg Oncol. 2003;83:68–78. doi: 10.1002/jso.10244. discussion 78–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Payment Policy for Inpatient Readmissions. Report to the Congress: Promoting Greater Efficiency in Medicare. 2007 June; Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/chapters/Jun07_Ch05.pdf.

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Fact sheet: Quality measures for reporting in fiscal year 2009 for 2010 update. 2008 April 14; 2008. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/media/fact_sheets.asp.

- 17.Acheson ED, Barr A. Multiple spells of in-patient treatment in a calendar year. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1965;19:182–191. doi: 10.1136/jech.19.4.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashton CM, Del Junco DJ, Souchek J, et al. The association between the quality of inpatient care and early readmission: a meta-analysis of the evidence. Med Care. 1997;35:1044–1059. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen J, Hjort-Jakobsen D, Christiansen PS, et al. Readmission rates after a planned hospital stay of 2 versus 3 days in fast-track colonic surgery. Br J Surg. 2007;94:890–893. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson AD, McNaught CE, MacFie J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of multimodal optimization and standard perioperative surgical care. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1497–1504. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azimuddin K, Rosen L, Reed JF, 3rd, et al. Readmissions after colorectal surgery cannot be predicted. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:942–946. doi: 10.1007/BF02235480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basse L, Hjort Jakobsen D, Billesbolle P, et al. A clinical pathway to accelerate recovery after colonic resection. Ann Surg. 2000;232:51–57. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200007000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basse L, Thorbol JE, Lossl K, et al. Colonic surgery with accelerated rehabilitation or conventional care. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:271–7. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0055-0. discussion 277–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basse L, Jakobsen DH, Bardram L, et al. Functional recovery after open versus laparoscopic colonic resection: a randomized, blinded study. Ann Surg. 2005;241:416–423. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000154149.85506.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradshaw BG, Liu SS, Thirlby RC. Standardized perioperative care protocols and reduced length of stay after colon surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:501–506. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delaney CP, Fazio VW, Senagore AJ, et al. ‘Fast track’ postoperative management protocol for patients with high co-morbidity undergoing complex abdominal and pelvic colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1533–1538. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delaney CP, Zutshi M, Senagore AJ, et al. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial between a pathway of controlled rehabilitation with early ambulation and diet and traditional postoperative care after laparotomy and intestinal resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:851–859. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gatt M, Anderson AD, Reddy BS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of multimodal optimization of surgical care in patients undergoing major colonic resection. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1354–1362. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorski TF, Rosen L, Lawrence S, et al. Usefulness of a state-legislated, comparative database to evaluate quality in colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1381–1387. doi: 10.1007/BF02235033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guinier D, Mantion GA, Alves A, et al. Risk factors of unplanned readmission after colorectal surgery: a prospective, multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1316–1323. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-0310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiran RP, Delaney CP, Senagore AJ, et al. Outcomes and prediction of hospital readmission after intestinal surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:877–883. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Brien DP, Senagore A, Merlino J, et al. Predictors and outcome of readmission after laparoscopic intestinal surgery. World J Surg. 2007;31:2430–2435. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9345-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raue W, Haase O, Junghans T, et al. ‘Fast-track’ multimodal rehabilitation program improves outcome after laparoscopic sigmoidectomy: a controlled prospective evaluation. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1463–1468. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9238-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senagore AJ, Duepree HJ, Delaney CP, et al. Results of a standardized technique and postoperative care plan for laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy: a 30-month experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:503–509. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Senagore AJ, Delaney CP, Brady KM, et al. Standardized approach to laparoscopic right colectomy: outcomes in 70 consecutive cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:675–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hannan EL, Racz MJ, Walford G, et al. Predictors of readmission for complications of coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 2003;290:773–780. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Etzioni DA, Liu JH, Maggard MA, et al. Workload projections for surgical oncology: will we need more surgeons? Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:1112–1117. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalez JR, Fernandez E, Moreno V, et al. Sex differences in hospital readmission among colorectal cancer patients. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:506–511. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexander DD, Waterbor J, Hughes T, et al. African-American and Caucasian disparities in colorectal cancer mortality and survival by data source: an epidemiologic review. Cancer Biomark. 2007;3:301–313. doi: 10.3233/cbm-2007-3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ananthakrishnan AN, Schellhase KG, Sparapani RA, et al. Disparities in colon cancer screening in the Medicare population. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:258–264. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chien C, Morimoto LM, Tom J, et al. Differences in colorectal carcinoma stage and survival by race and ethnicity. Cancer. 2005;104:629–639. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gross CP, Smith BD, Wolf E, et al. Racial disparities in cancer therapy: did the gap narrow between 1992 and 2002? Cancer. 2008;112:900–908. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kauh J, Brawley OW, Berger M. Racial disparities in colorectal cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2007;31:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diggs JC, Xu F, Diaz M, et al. Failure to screen: predictors and burden of emergency colorectal cancer resection. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:157–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kind AJ, Smith MA, Frytak JR, et al. Bouncing back: patterns and predictors of complicated transitions 30 days after hospitalization for acute ischemic stroke. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:365–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Handy JR, Jr, Child AI, Grunkemeier GL, et al. Hospital readmission after pulmonary resection: prevalence, patterns, and predisposing characteristics. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1855–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03247-7. discussion 1859–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emick DM, Riall TS, Cameron JL, et al. Hospital readmission after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1243–52. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.08.016. discussion 1252–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel SA, Zenilman ME. Outcomes in older people undergoing operative intervention for colorectal cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1561–1564. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]