Abstract

Increases in extracellular potassium concentration ([K+]o), which can occur during neuronal activity and under pathological conditions such as ischemia, lead to a variety of potentially detrimental effects on neuronal function. Although astrocytes are known to contribute to the clearance of excess K+o, the mechanisms are not fully understood. We examined the potential role of mitochondria in sequestering K+ in astrocytes. Astrocytes were loaded with the fluorescent K+ indicator PBFI and release of K+ from mitochondria into the cytoplasm was examined after uncoupling the mitochondrial membrane potential with carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP). Under the experimental conditions employed, transient applications of elevated [K+]o led to increases in K+ within mitochondria, as assessed by increases in the magnitudes of cytoplasmic [K+] ([K+]i) transients evoked by brief exposures to CCCP. When mitochondrial K+ sequestration was impaired by prolonged application of CCCP, there was a robust increase in [K+]i upon exposure to elevated [K+]o. Blockade of plasmalemmal K+ uptake routes by ouabain, Ba2+, or a mixture of voltage-activated K+ channel inhibitors reduced K+ uptake into mitochondria. Also, reductions in mitochondrial K+ uptake occurred in the presence of mito-KATP channel inhibitors. Rises in [K+]i evoked by brief applications of CCCP following exposure to high [K+]o were also reduced by gap junction blockers and in astrocytes isolated from connexin43-null mice, suggesting that connexins also play a role in K+ uptake into astrocyte mitochondria. We conclude that mitochondria play a key role in K+o handling by astrocytes.

Keywords: Channel/Other, Cell Junctions, Connexin, Mitochondria, Neurobiology, Astrocyte, Buffering, Gap Junction, Potassium

Introduction

Changes in extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o)3 can both reflect and, in turn, influence neuronal function. Normally ∼3 mm under resting conditions, [K+]o can increase to >10 mm during seizure activity, >25 mm during ischemia, and >50 mm during spreading depression, with consequent effects on neuronal excitability, synaptic transmission, neurotransmitter re-uptake and, ultimately, neuronal viability (reviewed in Refs. 1 and 2).

Astrocytes play a critical role in regulating [K+]o under both physiological and pathological conditions (reviewed in Refs. 1 and 3). Astrocytes are equipped with a variety of plasmalemmal K+ uptake mechanisms, including Na+,K+-ATPase, ion transporters (e.g. Na+-K+-2Cl− co-transport), and voltage-activated K+ channels (e.g. inward rectifier (Kir), delayed rectifier (Kdr), and A-type (Ka) K+ channels). Astrocytes are also extensively coupled by gap junctions that aid in the spatial redistribution of K+ from areas of high [K+]o/i to those of low [K+]o/i (1, 3–6). This spatial buffering is achieved when a local increase in [K+]o causes the K+ equilibrium potential (EK) to become more positive than the membrane potential, allowing K+ influx into an astrocyte. Meanwhile, at more distant sites, where EK remains more negative than the membrane potential, K+ leaves the syncytium.

Another mechanism that could limit potentially detrimental increases in astrocytic [K+]i that might otherwise occur during K+ uptake is transient sequestration into intracellular stores. Mitochondria in close association with the plasmalemmal membrane have been shown to play an important role in internal Ca2+ and Na+ sequestration in a variety of cell types (7–13) and the potential involvement of analogous mechanisms in internal K+ handling are starting to be explored.

Several lines of evidence are consistent with a potential role for mitochondria in K+ sequestration. First, mitochondria are intimately associated with the plasma membrane (14, 15), placing them in an appropriate location to sequester K+ that enters a cell across the plasma membrane. Second, the mitochondrial inner membrane is endowed with a variety of K+ channels and transporters that contribute to the regulation of the inner mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm), matrix volume, and oxidative phosphorylation (16). Third, mitochondria have a negative resting membrane potential, creating a driving force for K+ uptake (17). Fourth, mitochondria maintain matrix [K+] at 150–180 mm (18, 19), a higher concentration than [K+]i (∼100 mm) (20). Finally, mitochondria in cardiomyocytes have been reported to act as sinks for K+o (21).

In this study we investigated the role of mitochondria in the uptake of K+o by astrocytes. To avoid the difficulties and potential artifacts associated with isolated mitochondrial preparations (e.g. see Refs. 22 and 23) we assessed mitochondrial K+ uptake in intact astrocytes. We determined that mitochondrial KATP channels (mito-KATP) and potentially mitochondrial connexin43 (Cx43), a protein that is abundantly expressed in astrocytes and has recently been found to contribute to K+ uptake in isolated cardiac mitochondria (24), play a role in the temporary sequestration of K+ by astrocyte mitochondria.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cortical Astrocyte Cultures

Cortical astrocytes from neonatal (1–2 days) CD-1 wild-type mice were cultured and plated, unless otherwise indicated, onto poly-d-lysine-coated glass coverslips in 24-well plates and maintained as previously described (25). Primary astrocytes were used between 7 and 28 days in vitro and the results obtained were not dependent on the length of time the astrocytes were maintained in culture.

For a portion of the experiments, wild-type (Cx43+/+), heterozygous (Cx43+/−), and Cx43-null (Cx43−/−) astrocytes were obtained from CD57/Bl6 mice generated by crossing heterozygous mice with the Gja1 null mutation (26) using procedures as described above. Tissue from each newborn pup was genotyped by PCR using primers specific for the wild-type Cx43 and the disrupted Cx43 gene, as previously described (27).

Solutions and Test Compounds

The standard perfusion medium contained (in mm): 136.5 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.5 NaH2PO4, 1.5 MgSO4, 10 d-glucose, 2 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES (titrated to pH 7.35 with 10 m NaOH). Bicarbonate-containing perfusion medium contained (in mm): 117.5 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.5 NaH2PO4, 1.5 MgSO4, 10 d-glucose, 2 CaCl2, and 29 NaHCO3, and was equilibrated with 5% CO2 in air (pHo 7.35). Medium containing high [K+] or the K+ channel blocking mixture (3 mm BaCl2, 5 mm 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), and 1 mm TEA) were prepared by equimolar substitution for NaCl. In solutions containing BaCl2, NaH2PO4 was omitted and MgSO4 was replaced with MgCl2. Test compounds (bumetanide, carbenoxolone (CBX), carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), diazoxide, carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), furosemide, glyburide, 18α-glycyrrhetinic acid (AGA), glycyrrhizic acid (GZA), 5-hydroxydecanoic acid (5-HD), oligomycin, omeprazole, ouabain, quinine, saponin, and timolol) were obtained from Sigma and applied by superfusion. Experiments were performed at room temperature (20–22 °C) unless otherwise indicated.

Measurement of Cytoplasmic K+ Concentration

Astrocytes were placed for 1 h at room temperature in standard HEPES-buffered medium containing 5 μm of the K+-sensitive fluorophore potassium-binding benzofuran isophthalate acetoxymethyl ester (PBFI) and 0.05% pluronic F-127 (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR). Cells were then placed in fluorophore-free medium for 30 min to ensure de-esterification of the fluorophore and then mounted in a perfusion chamber on a Zeiss Axioskop2 FS Plus microscope (Carl Zeiss Canada Ltd., ON). Astrocytes were continuously superfused at ∼2 ml/min throughout the course of an experiment.

Measurements of [K+]i with PBFI were performed using the dual excitation ratio method. Fluorescence emissions >505 nm were captured by a 12-bit digital cooled CCD camera (Retiga EXi, QImaging, Burnaby, BC) from regions of interest placed on individual astrocytes. Raw emission intensity data at each excitation wavelength (340 and 380 nm; Lambda DG-5, Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA) were collected every 6 s, corrected for background fluorescence, and background-subtracted ratio pairs (BI340/BI380) were analyzed off-line. In a cell-free system using the camera gain and exposure settings employed throughout the study, fluorescence signals were not detectable from any of the test compounds employed. In addition, a subset of experiments similar to those shown in Fig. 3A were performed in non-PBFI-loaded cells and no changes in 340 and 380 nm emission signals or 340/380 ratio values were detected upon exposure to CCCP or high [K+]o, indicating that endogenous fluorescence from molecules (e.g. NADH) is unlikely to contribute to the changes in the PBFI-derived ratio values measured in the study (data not shown). Furthermore, CCCP responses were nearly abolished in gramicidin-permeabilized PBFI-loaded astrocytes (supplemental Fig. S1), indicating it is unlikely that the effect of CCCP to increase the PBFI signal represents an artifact.

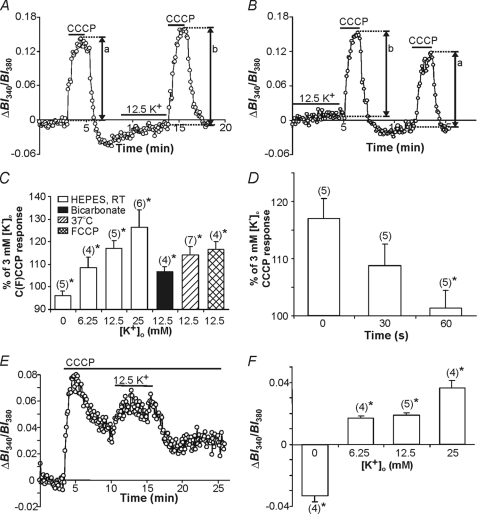

FIGURE 3.

Effects of changes in [K+]o on CCCP-induced [K+]i rises. A, an initial 2-min application of CCCP (at [K+]o = 3 mm) evoked a [K+]i transient. Following the recovery of [K+]i to near resting levels, [K+]o was increased to 12.5 mm for 5 min, immediately after which CCCP was again applied at [K+]o = 3 mm. The rise in [K+]i evoked by the second application of CCCP (indicated by b) was larger than that evoked by the first application (indicated by a) of the protonophore. B, the same experiment as illustrated in A, except [K+]o was increased to 12.5 mm prior to the first application of CCCP. C, summary of the results obtained in experiments of the type shown in A and B conducted under HEPES- (open bars) and HCO3−/CO2−- (solid bars) buffered conditions. Also shown are results obtained under HEPES-buffered recording conditions at 37 °C (hatched bars) and with FCCP (crosshatched bars). In all cases, changes in [K+]o (0–25 mm) were applied for 5 min immediately prior to the application of CCCP at [K+]o = 3 mm. Results are presented as percent changes in the peak amplitudes of CCCP-evoked PBFI-derived BI340/BI380 ratio value transients (representing [K+]i) after altered [K+]o, compared with control responses evoked by CCCP in the absence of a preceding change in [K+]o. In all cases, there was a significant change (*, p < 0.05) in the amplitude of [K+]i transients observed after pretreatment with altered [K+]o compared with those evoked under control conditions. Responses due to 12.5 mm [K+]o were significantly different under HEPES- versus bicarbonate-buffered conditions (p < 0.05). Furthermore, responses to 12.5 mm [K+]o under HEPES-based recording conditions were similar to the response in the FCCP and 37 °C groups (p > 0.05). D, following an initial 2-min application of CCCP at [K+]o = 3 mm, astrocytes were exposed to 12.5 mm [K+]o for 5 min, after which [K+]o was reduced to 3 mm for 0, 30, or 60 s prior to the second application of CCCP (also at 3 mm K+o). The increase in the CCCP-induced [K+]i transient observed following pretreatment with 12.5 mm K+o was not significantly altered (p > 0.05) at 30 s but was effectively abolished (*, p < 0.05) at 60 s after the end of the pretreatment (n = 5 in each case). E, exposure to 12.5 mm [K+]o during mitochondrial uncoupling with prolonged CCCP treatment caused an increase in resting [K+]i. F, summary of the results obtained in experiments of the type shown in E. Results are presented as the average amplitudes of the changes in PBFI-derived BI340/BI380 ratio values observed over the final 1-min exposure to altered [K+]o after subtraction of the [K+]i value observed immediately prior to altering [K+]o. *, p < 0.05 in all cases. The respective n values are indicated in parentheses. Bars indicated the mean ± S.E.

To determine the sensitivity of PBFI to K+ in our preparation of cultured astrocytes, in situ calibration experiments were performed in which astrocytes were exposed sequentially to medium containing (in mm): 1.5 NaH2PO4, 1.5 MgSO4, 10 d-glucose, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, four different [K+] values (range 80–140 mm), LiCl (as appropriate to balance osmolarity), and 10 μm gramicidin (pH 7.35 with 1 m LiOH). Additionally, sensitivity to Na+ was assessed by performing calibrations in the presence of 65 mm NaCl. Sensitivity to pH was also assessed by adjusting the pH to either 6.5 or 8 with 1 m LiOH. PBFI sensitivity to 80, 100, and 140 mm K+o was also assessed in the presence of 10 μm CCCP. PBFI-derived BI340/BI380 ratio values were normalized to the BI340/BI380 ratio value obtained at [K+] = 100 mm, and the data points relating [K+] to the normalized, background-subtracted PBFI ratio values were fitted (r2 > 0.99) by a three-parameter hyperbolic equation (28).

Measurement of Mitochondrial K+ Sequestration in Situ by Application of CCCP

Two paradigms were employed in this study. First, mitochondrial K+ was assessed using a protocol similar to that previously utilized in the examination of mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering (23, 29, 30). The mitochondrial membrane uncoupler CCCP (10 μm) was applied for 2 min to reversibly collapse ΔΨm, which caused efflux of mitochondrial K+ that was detected by cytoplasmic PBFI (e.g. see Fig. 2A), giving a measure of mitochondrial K+ content. [K+]o was then increased (or decreased) for 5 min prior to the next 2-min application of CCCP (e.g. see Fig. 3, A and B). The difference in the magnitude of response reflected mitochondrial K+ sequestration. For analysis, BI340/BI380 values obtained under resting conditions at the start of an experiment were subtracted from the BI340/BI380 values measured during the entire experiment. Changes in [K+]i evoked by brief (2 min) exposures to CCCP were quantified as the percent difference between the peak CCCP-induced BI340/BI380 transient measured after exposure to altered [K+]o and the peak CCCP-induced BI340/BI380 transient measured in the same cells during perfusion with normal [K+]o (3 mm).

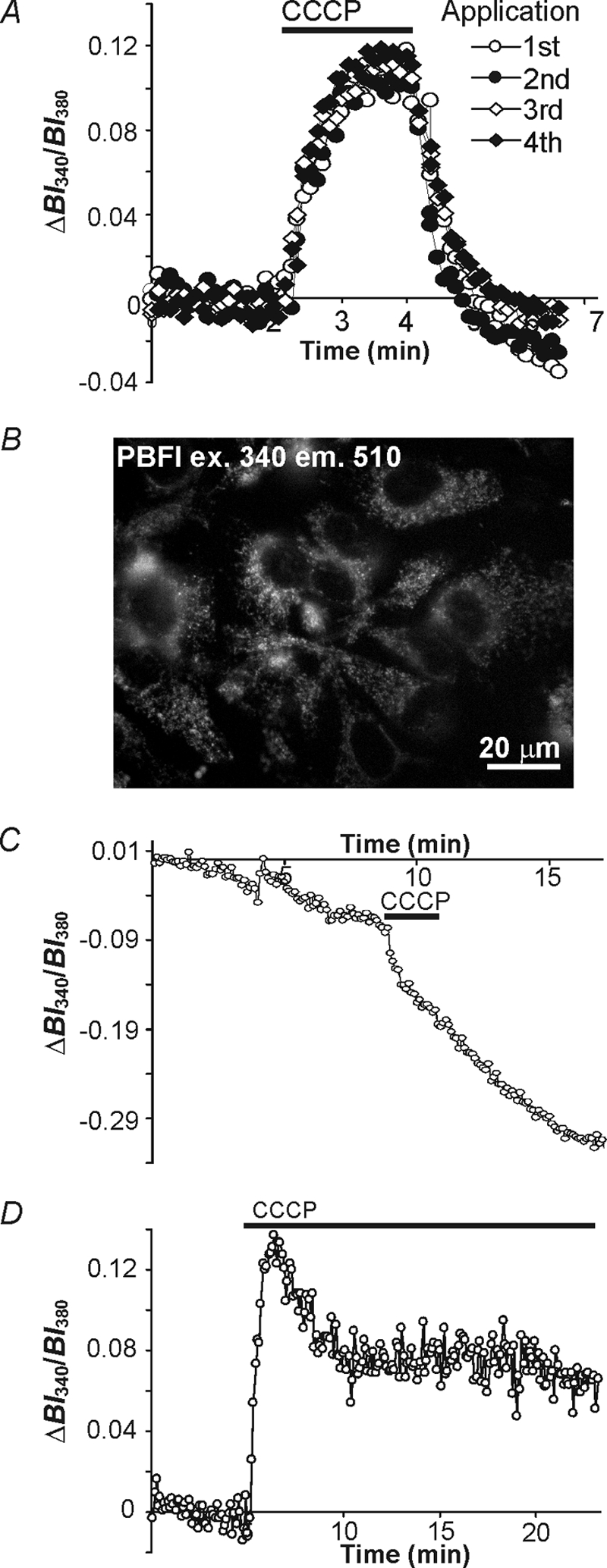

FIGURE 2.

CCCP evokes an increase in [K+]i in cultured astrocytes. A, under standard PBFI loading conditions, superimposed records of the changes in [K+]i (represented by changes in cytosolic PBFI-derived BI340/BI380 ratio values) were evoked by four consecutive 2-min applications of 10 μm CCCP. For each response, BI340/BI380 ratio values were baseline adjusted to the resting BI340/BI380 value observed immediately prior to the appropriate application of CCCP. The rises in [K+]i evoked by CCCP remained unaltered during repeated 2-min applications of CCCP (n = 5 preparations, p > 0.05). B, an image of astrocytes (excitation wavelength 340 nm) after preferentially loading of PBFI into mitochondria and following 50 μg/ml of saponin treatment to release cytosolic PBFI. Under these conditions signals largely emanate from mitochondria. C, in saponin-treated astrocytes under external Na+- and K+-free recording conditions, mitochondrial-derived PBFI BI340/BI380 ratio values declined rapidly upon uncoupling with a 2-min application of 10 μm CCCP indicating mitochondria release K+, which can be detected by cytosolic PBFI as indicated in A. D, under standard PBFI loading conditions prolonged application of 10 μm CCCP caused an immediate increase in [K+]i followed by a gradual decrease in [K+]i to a new steady state level. All records in A and D were obtained at [K+]o = 3 mm.

In the second paradigm, 10 μm CCCP was applied for an extended period of time (∼15 min) to uncouple the mitochondrial membrane thereby inhibiting K+ sequestration. [K+]o was altered in the continued presence of CCCP and [K+]i was monitored by changes in cytoplasmic PBFI ratio values. This paradigm was used to reflect changes in K+ entry across the plasma membrane in the absence of mitochondrial sequestration. For analysis, changes in [K+]i observed during changes in [K+]o were quantified by subtracting the steady-state BI340/BI380 value measured prior to altering [K+]o from the average BI340/BI380 value obtained over the final minute of exposure to altered [K+]o (e.g. see Fig. 3, E and F).

Measurement of Cytoplasmic Na+ Concentration

Measurements of [Na+]i in astrocytes exposed to CCCP were performed with sodium-binding benzofuran isophthalate, as detailed previously (28, 31).

Measurement of Mitochondrial K+

Measurements of mitochondrial K+ were performed using a PBFI loading protocol that favors mitochondrial dye localization (24, 32, 33). In brief, astrocytes were placed for 1 h at 37 °C in standard HEPES-buffered medium containing 10 μm PBFI and 0.05% pluronic F-127. Cells were then placed in fluorophore-free medium for 30 min. To permeabilize the plasma membrane and release PBFI from the cytoplasmic compartment cells were treated with 50 μg/ml of saponin for 5 min (33) in a mitochondria medium containing (in mm) 250 sucrose, 25 Tris, 3 EGTA, 5 MgCl2, 5 succinate, and 5 glutamate (pH 7.3) (32). Preparations used to assess mitochondrial K+ uptake (e.g. see Fig. 6) were additionally incubated in a medium containing (mm) 200 sucrose, 50 TEA, 25 Tris, 3 EGTA, 5 MgCl2, 5 succinate, and 5 glutamate (pH 7.3) for 20 min to deplete mitochondrial K+ (see Ref. 24). Mitochondria from the permeabilized astrocytes were subsequently imaged in the mitochondria medium. K+ uptake into mitochondria was assessed by measuring the rate of change of PBFI-derived ratio values upon exposure to 25 mm K+ (solution containing (in mm) 200 sucrose, 25 KCl, 25 Tris, 3 EGTA, 5 MgCl2, 5 succinate, and 5 glutamate; pH 7.3) applied at a bath perfusion rate of 4.2 ml/min. At the camera settings utilized in this study, fluorescence signals were not discernable in PBFI-free saponin-treated astrocytes (data not shown).

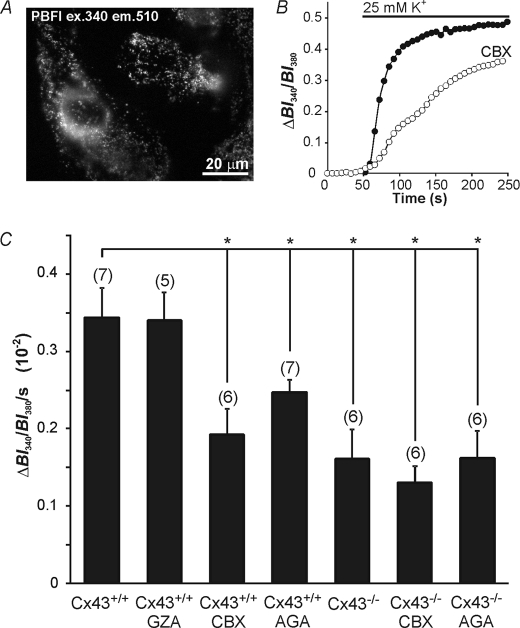

FIGURE 6.

K+ uptake in mitochondria from cultured astrocytes. A, mitochondria were preferentially loaded with PBFI and treated with saponin to remove cytosolic dye yielding signals largely derived from mitochondria. B, mitochondria were initially perfused with a K+-free solution followed by application of a solution containing 25 mm K+. In Cx43+/+ cultures application of 25 mm K+ caused an increase in K+ in the mitochondria, an effect that was reduced by the Cx43 blocker CBX (20 μm). C, a graph quantifying the changes in K+ uptake rate, defined by the change in ratio value over the first 100 s during the initial rise in PBFI ratio upon application of 25 mm K+. K+ uptake was significantly reduced with treatment of the Cx43 blockers CBX (20 μm) and AGA (10 μm), and was not reduced with the inactive analogue GZA (20 μm). K+ uptake was also reduced in mitochondria obtained from Cx43−/− mice. Application of CBX or AGA was ineffective in further reducing K+ uptake in Cx43−/− mice. *, p < 0.05, n values in parentheses represent the number of individual coverslips tested. Bars indicate the mean ± S.E.

Assessment of Changes in Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

Astrocytes were placed in standard HEPES-buffered medium containing 5 μm rhodamine-123 (Molecular Probes Inc.) for 15 min and then washed in standard HEPES medium for 30 min. The dye was excited at 495 nm and emissions were collected at >505 nm. For analysis, ΔF/F was measured by dividing rhodamine-123-derived BI495 values measured during exposure to high [K+]o by the average of BI495 values obtained during the control portion of an experiment.

ATP Measurements

Intracellular ATP content was determined by luciferin/luciferase luminescence using an ATP determination kit (Molecular Probes Inc.). Astrocytes grown in 6-well plates were rinsed with standard perfusion medium. Cultures were then treated with (a) standard perfusion medium, (b) 10 μm CCCP for 2 min followed by a 10-min wash with standard perfusion medium, or (c) 10 μm CCCP for 10 min. Cells were then lysed with 80 μl of 10 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.5), 0.1 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.01% Triton X-100 and a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). Aliquots (10 μl) were then obtained and added to the luciferin/luciferase luminescence reaction mixture and sample luminescence was detected with a Berthold LB9507 Lumat luminometer (Fisher Scientific). ATP measurements were made in duplicate. Samples were also obtained for protein concentration determination using the BCA protein quantification kit (Pierce). Cellular ATP content was estimated by assuming an astrocyte volume of 4.8 liters/kg of protein (34).

Western Blot

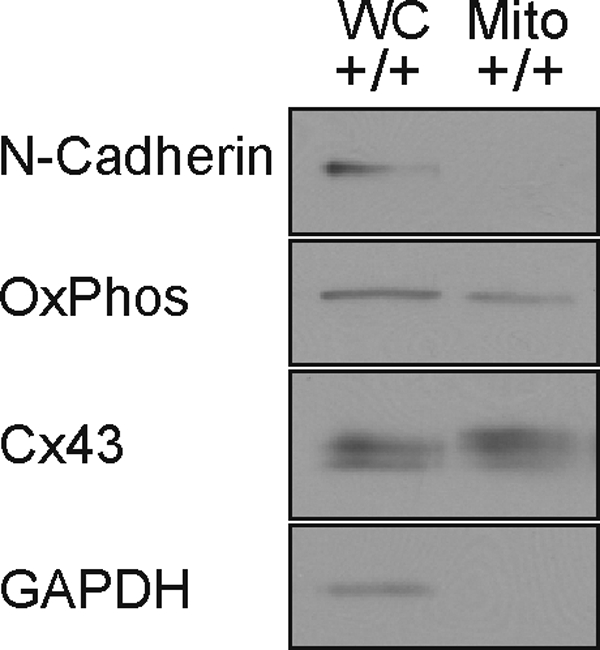

Whole cell fractions were obtained by lysing Cx43+/+ and Cx43−/− astrocytes grown on 100-mm culture dishes in radioimmunoprecipitation lysis buffer containing phosphatase (Sigma) and protease inhibitors (Roche). The cells were then scraped and the solution was drawn up with a 22-guage needle and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein quantification kit (Pierce). Mitochondria were obtained from sister cultures using a mitochondria isolation kit (Pierce). Both mitochondrial and whole cell fractions were boiled for 1 min in sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer. Whole cell fractions containing 10 μg of protein and 10 μg of samples of the mitochondrial fraction were separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel in parallel with molecular weight markers (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Proteins were transferred and probed according to standard protocols (35). The following primary antibodies at the dilutions indicated were applied overnight at 4 °C: 1:8,000 anti-connexin43 produced in rabbit (Sigma, catalogue C6219), 1:1,500 anti-OxPhos Complex V subunit α produced in mouse (Molecular Probes Inc.), or 1:2,500 anti-N-cadherin produced in mouse (BD Transduction Laboratories). Horseradish peroxidase-tagged secondary antibody (Cedarlane Laboratories, ON) was applied for 1 h at a 1:20,000 dilution and subsequently detected with Super-Signal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce). The labeled blots were exposed to x-ray film to visualize antibody binding. As necessary, the blot was stripped with Restore Western blot stripping buffer (Pierce) and reprobed with a different primary antibody. To ensure equivalent loading of protein samples the blots were stripped and probed with 1:10,000 anti-GAPDH produced in rabbit (Cedarlane Laboratories).

Data Analysis

Results are reported as mean ± S.E. with the accompanying n value referring to the number of cell populations (i.e. number of coverslips) analyzed under each experimental condition. In the imaging experiments, data were obtained simultaneously from 10 to 20 astrocytes per coverslip and averaged. Unless otherwise indicated, statistical comparisons were performed using Student's unpaired t test, with a 95% confidence limit.

RESULTS

Measurement of Cytoplasmic [K+] with PBFI in Cultured Astrocytes

Determination of [K+]i with PBFI may be problematic because PBFI-free acid in aqueous solution exhibits a limited resolution for increases in [K+]i above the physiological range (36). Nevertheless, incorporated inside cells, PBFI has successfully been employed to measure increases in [K+]i from high resting [K+]i values (e.g. Refs. 37–39), findings that suggest that the K+ affinity of PBFI may become reduced in a cellular context (as is known to be the case for the related dye sodium-binding benzofuran isophthalate, the KD of which for Na+ displays a marked increase in cells compared with the dye in free solution (40)). To examine this possibility, we performed in situ calibration experiments to examine the sensitivity of PBFI for [K+] over a physiologically relevant range ([K+]i = 80 to 140 mm). As shown in Fig. 1, increasing [K+]i from 80 to 140 mm in 20 mm steps led to detectable increases in PBFI-derived ratio values, and the dye did not appear to saturate even at 140 mm [K+].

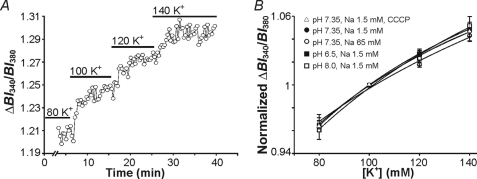

FIGURE 1.

In situ calibration of PBFI. A, a calibration experiment in which PBFI-loaded cultured astrocytes on a single coverslip were exposed to 10 μm gramicidin-containing HEPES-buffered solutions at the [K+]o values (in mm) shown above. B, a plot of [K+] versus PBFI-derived BI340/BI380 ratio values normalized to unity at [K+] = 100 mm from calibration experiments of the type shown in A. In comparison to the standard calibration curve (closed circle, n = 6), curves did not differ at [Na+]o = 65 mm (open circle, n = 5), nor when pH was altered to pH 6.5 (closed square, n = 5), pH 8 (open square, n = 5), or in the presence of CCCP (open triangle, n = 5). In all cases, p > 0.05 (two-way ANOVA). Bars indicate the mean ± S.E.

A second potential difficulty with the use of PBFI in the present experiments is its reported affinity for Na+ ions (36). To assess whether changes in [Na+]i could contribute to changes in PBFI fluorescence signals under the present experimental conditions, in situ calibration experiments (see Ref. 28) were performed by exposing astrocytes to either 1.5 or 65 mm [Na+]i (the latter approximating the rise in [Na+]i following a 5-min exposure to CCCP; see supplemental Fig. S2). The calibration curves obtained at 1.5 and 65 mm Na+ did not differ (Fig. 1B; p > 0.05, two-way ANOVA), indicating that the sensitivity of PBFI to [Na+] is weak under our experimental conditions and is unlikely to affect our measurements of [K+]i. In agreement, Kasner and Ganz (39) found that [Na+] failed to alter the fluorescent properties of PBFI loaded into mesangial cells until [Na+]i was >75 mm.

As protonophores, such as CCCP, are known to cause small changes in pH (41) we also performed calibration experiments at pH 6.5 and 8. Neither alteration caused a change in PBFI sensitivity for [K+] in comparison to the standard calibration curve obtained at pH 7.35 (Fig. 1B; p > 0.05, two-way ANOVA). In addition, 10 μm CCCP did not alter the sensitivity of PBFI for [K+] (Fig. 1B; p > 0.05, two-way ANOVA). Furthermore, PBFI is known to be insensitive to changes in [Ca2+], [Mg2+], and osmolarity within the ranges expected in the present study (e.g. Ref. 36; see also Ref. 42).

Taken together these observations support the use of PBFI in the present study to measure increases in [K+]i above the resting level in astrocytes. Nevertheless, as discussed by Kasner and Ganz (39), the hyperbolic form of the PBFI calibration curve underscores the difficulty of determining accurate absolute values for [K+]i, especially at high concentrations of K+. In the present study, therefore, changes in [K+]i are presented as changes in PBFI-derived BI340/BI380 ratio values.

Finally, fluorescent [ion] indicators (e.g. fura-2, sodium-binding benzofuran isophthalate) loaded as acetoxymethyl esters can enter internal organelles as well as the cytoplasm. To examine the potential compartmentalization of PBFI in astrocytes under the standard (room temperature) loading conditions employed for the majority of the experiments reported here, astrocytes were treated with 0.05% saponin to release dye located in the cytoplasm. Saponin treatment reduced PBFI-derived emission intensities at each excitation wavelength by >85% (data not shown), indicating that under our standard loading conditions the majority of PBFI was situated in the cytosolic compartment. The remaining PBFI-derived fluorescence signal presumably emanates from intracellular organelles, including mitochondria. With regard to the latter, it is important to note that if mitochondrial [K+] in situ is higher than cytosolic [K+] (18, 43) any contribution from PBFI localized to mitochondria to an experimentally induced change in the total (i.e. cytosolic + organellar) PBFI fluorescence signal will be relatively small (see the PBFI calibration curve presented in Fig. 1B). Furthermore, because mitochondrial [K+] was decreasing in response to the majority of our experimental maneuvers (e.g. see Fig. 2C), this will further decrease the contribution of any PBFI localized in mitochondria to the total PBFI signal. These considerations suggest that, under the standard loading conditions employed, any PBFI fluorescence derived from mitochondria will not perturb our total PBFI signal. Consequently, we conclude that experimentally induced changes in the PBFI ratio values will largely reflect changes in cytoplasmic [K+] rather than [K+] within internal organelles.

CCCP Increases [K+]i in Cultured Astrocytes

We sought to determine whether astrocytic mitochondria in situ sequester K+ by exposing astrocytes to the uncoupling agent CCCP. As outlined under “Experimental Procedures,” two paradigms were employed. First, as illustrated in Fig. 2A, a 2-min application of CCCP (10 μm) under control (3 mm K+o) conditions was used to induce a rapid increase in the PBFI-derived BI340/BI380 ratio value (representing mitochondrial K+ efflux). Consistent with previous observations (41), the effect of a brief application of CCCP was reversible and washout of the protonophore was followed by a rapid fall in [K+]i to below resting levels, after which [K+]i slowly returned toward baseline. The undershoot of [K+]i after CCCP washout may represent the efflux of K+ through plasma membrane K+ channels (38) and/or the re-uptake of K+ into mitochondria. Additional 2-min applications of CCCP produced rises in [K+]i, the amplitudes of which remained unchanged (one-way ANOVA, p > 0.05) over successive (up to 4) CCCP applications (Fig. 2A). The increase in cytoplasmic [K+] detected by PBFI after uncoupling the mitochondrial membrane with CCCP is unlikely to reflect K+ entry across the plasma membrane as [K+]i is low in comparison to resting [K+]i (which in astrocytes has been estimated at ∼100 mm (20)). Rather, because mitochondria maintain an elevated matrix [K+] (see Introduction), the release of K+ from mitochondria may be the source of the CCCP-induced increase in cytoplasmic [K+]. To examine this possibility directly, astrocytes were loaded with PBFI using an established protocol that promotes the localization of the dye in mitochondria (see Refs. 32, 33, and 44). Astrocytes were subsequently exposed to 50 μg/ml of saponin to release any dye located in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2B). In separate experiments, dye localization to mitochondria was confirmed by co-labeling with the mitochondrial marker rhodamine-123 (data not shown; see Ref. 44). The release of K+ from mitochondria induced by CCCP was then examined under Na+o- and K+o-free conditions to avoid the potentially confounding effects of Na+ and/or K+ entry across the plasma membrane. As shown in Fig. 2C, under these conditions the mitochondrial fluorescence signal slowly declined, and a 2-min application of CCCP caused a rapid further reduction in the fluorescence signal (n = 4) indicating the release of K+ from mitochondria (38). This is consistent with our suggestion that CCCP-induced increases in cytoplasmic [K+] emanate largely through K+ efflux from mitochondria. The continued decline of the PBFI signal after CCCP withdrawal seen in Fig. 2C reflects the fact that the experiment was conducted in saponin-treated cells in the absence of K+o, conditions that do not favor the refilling of mitochondria with K+.

Next, using the standard PBFI loading protocol, astrocytes were subjected to the second paradigm. More prolonged applications of CCCP (>15 min) at 3 mm K+o evoked an initial rise in [K+]i that was followed by a slow decline to a plateau steady-state level in the continued presence of the protonophore (Fig. 2D). The early rise in [K+]i, as discussed above, is due to mitochondrial K+ efflux, whereas the gradual decline in signal is suggestive of a gradual loss of K+ to the extracellular space. This paradigm was used to assess plasma membrane K+ entry in the absence of mitochondrial K+ sequestration, as ΔΨm is collapsed in the presence of CCCP (e.g. Fig. 3, E and F).

Temporary Sequestration of K+ in Astrocyte Mitochondria

A large body of evidence obtained in multiple cell types, including astrocytes, indicates that mitochondria are able to sequester Ca2+ (and Na+) ions entering across the plasma membrane and thereby limit potentially detrimental cytosolic [Ca2+] elevations that might otherwise occur upon Ca2+ entry into a cell (reviewed by Refs. 8 and 45; see also Refs. 10, 12, and 13). Therefore, we examined whether astrocyte mitochondria might act in an analogous manner to sequester K+ entering astrocytes. In these experiments, CCCP (10 μm) was applied for 2 min (at [K+]i = 3 mm) to release K+ from mitochondria and, several minutes after CCCP washout, [K+]o was adjusted to 0–25 mm for 5 min, after which CCCP was again applied for 2 min at 3 mm [K+]o. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, the increase in [K+]i evoked by CCCP following exposure to elevated [K+]o was larger than the increase in [K+]i evoked by CCCP in the absence of a prior exposure to high [K+]o. Because the amplitudes of the CCCP-induced increases in PBFI-derived ratio values varied between different astrocyte cultures, peak amplitudes of the changes in BI340/BI380 ratio values evoked by CCCP following exposure to altered [K+]o were compared relative to the peak amplitudes of the responses obtained in the same population of astrocytes under control conditions (i.e. in the absence of a prior exposure to altered [K+]o). In many experiments, the PBFI signal in response to the initial application of CCCP failed to return completely to baseline prior to the second application of the uncoupling agent. Therefore, experiments were also performed in which elevated [K+]o was applied prior to the first application of CCCP (i.e. in the absence of an undershoot) rather than the second application of CCCP (i.e. during the undershoot after the first application). As illustrated in Fig. 3B, the increase in [K+]i evoked by CCCP continued to be greater following the prior application of raised [K+]o. The pooled data from these experiments are shown in Fig. 3C and indicate that CCCP-induced rises in [K+]i were significantly (p < 0.05 in all cases) greater following 5-min exposures to 6.25–25 mm [K+]o than under control conditions; conversely, CCCP-induced rises in [K+]i were significantly (p < 0.05) smaller when CCCP was applied after a 5-min exposure to K+-free medium. Quantitatively similar results were obtained with another protonophore, FCCP (Fig. 3C), which is also known to elicit rises in [K+]i (38).

The aforementioned data were obtained at room temperature in the absence of HCO3−. Therefore, additional experiments were performed under more physiological conditions, i.e. at 37 °C or in the presence of HCO3−. At 37 °C, the absolute magnitudes of the CCCP-induced increases in PBFI-derived ratio values were greater than those observed at room temperature; however, the relative increase in [K+]i evoked by CCCP following exposure to 12.5 mm K+o continued to be significantly larger than the increase in [K+]i evoked by CCCP in the absence of a prior exposure to high [K+]o and was not significantly different (p > 0.05) to the result obtained at room temperature (Fig. 3C). In the presence of HCO3− the relative increase in [K+]i evoked by CCCP following exposure to 12.5 mm K+o continued to be significantly larger than the increase in [K+]i evoked by CCCP in the absence of a prior exposure to high [K+]o (Fig. 3C). (As reported previously, distinct increases in resting [K+]i were observed in the presence of HCO3− upon exposure to high [K+]o (20), whereas high [K+]o evoked only small increases in resting [K+]i under HEPES-buffered conditions (see Fig. 3, A and B, and supplemental Fig. S3). A potential explanation for these observations is that Na+-HCO3− co-transporters may provide Na+ ions for Na+,K+-ATPase-dependent K+ uptake (46), hence overall K+ uptake may be reduced in HEPES-based recording solutions.)

In light of the fact that [ATP]i is known to decline in response to CCCP application (47, 48), additional experiments (n = 4) were performed in the presence of 20 μm oligomycin, an ATP synthase inhibitor, to maintain ATP levels after the brief (2 min) application of CCCP (48). No change in K+ sequestration was observed using this treatment, indicating that changes in [ATP] induced by brief applications of CCCP do not affect mitochondrial K+ sequestration (data not shown).

To examine the length of time that mitochondria are apparently able to sequester K+ in response to a period of elevated [K+]o, astrocytes were exposed to 12.5 mm [K+]o for 5 min, after which [K+]o was reduced to 3 mm for 30 or 60 s immediately prior to a 2-min application of 10 μm CCCP also at 3 mm K+o. As illustrated in Fig. 3D, the relative increase in the CCCP-induced [K+]i transient elicited by pre-exposure to high [K+]o was abolished when CCCP was applied 60 s after the end of the 5-min pretreatment with 12.5 mm K+o (n = 5 in each case).

To further assess the potential role of mitochondria in sequestering K+ during exposure to elevated [K+]o, [K+]o was altered during prolonged mitochondrial uncoupling with CCCP to completely dissipate ΔΨm. As noted previously (Fig. 2D), the prolonged application of CCCP under control conditions (3 mm K+o) elicited a rise in [K+]i, which then declined to a new steady-state, elevated level in the continued presence of CCCP. When [K+]o was then increased to concentrations varying from 6.25 to 25 mm during the plateau phase of the CCCP-induced [K+]i response, there was an additional rise in [K+]i (Fig. 3, E and F). Conversely, when [K+]o was lowered to 0 mm a reduction in steady-state [K+]i was observed. These results contrast with the failure of raised [K+]o to substantially increase [K+]i under HEPES-buffered conditions in the absence of CCCP and are consistent with a role for mitochondria in the sequestration of K+.

Because CCCP is known to affect [Ca2+]i and mitochondrial Ca2+ handling (30, 49), experiments similar to those illustrated in Fig. 3, A and E, were performed under external Ca2+-free conditions, which have previously been shown to nearly abolish CCCP-induced increases in [Ca2+]i (49). Results similar to those observed in the presence of 2 mm Ca2+o were obtained in both transient (n = 4) and prolonged (n = 4) CCCP exposure protocols, effectively ruling out an influence of Ca2+ influx on K+ uptake under our experimental conditions (data not shown).

Effects of Blocking Plasmalemmal or Mitochondrial K+ Uptake Mechanisms

A number of mechanisms have been suggested to contribute to the uptake of K+ across the plasma membrane of astrocytes, including the Na+,K+-ATPase, Na+-K+-2Cl− co-transport, and a variety of voltage-activated K+ channels (1, 6, 32). The entry of K+ across the mitochondrial inner membrane into mitochondria occurs via a K+ leak pathway dependent on the ΔΨm and a K+ uniporter, mito-KATP, whereas excess K+ can be removed by a K+/H+ antiporter (16); calcium-sensitive mitochondrial potassium (mito-KCa) currents have also been described (33). To determine whether these mechanisms contribute to K+o uptake into astrocyte mitochondria, the effects of a variety of inhibitors were examined on the changes in [K+]i evoked by 5-min exposures to 12.5 mm K+o during prolonged mitochondrial uncoupling with CCCP, where mitochondrial K+ sequestration is impaired, and on the [K+]i transient induced by a 2-min application of CCCP immediately after a 5-min exposure to 12.5 mm K+o.

Under conditions where mitochondrial sequestration mechanisms are impaired (i.e. prolonged mitochondrial uncoupling with CCCP), the effects of inhibiting established K+ entry pathways in the plasma membrane were examined on the change in [K+]i evoked by 12.5 mm K+o (Fig. 4, A and B). Under these conditions the high [K+]o-evoked rise in [K+]i was reduced by inhibiting Kir with 50 μm Ba2+, and was effectively blocked by a K+ channel blocking mixture containing 3 mm Ba2+, 5 mm 4-AP, and 1 mm TEA to inhibit Kir, Kdr, and Ka channels (Fig. 4, A and B; p < 0.05 and n = 5 in each case). The potential involvement of KATP channels was assessed with the KATP channel inhibitor glyburide (1 μm), which did not affect K+ entry (Fig. 4B; p > 0.05 and n = 5). In addition, the Na+,K+-ATPase inhibitor ouabain (1 mm) did not significantly affect the high [K+]o-evoked rise in [K+]i observed during prolonged exposure to CCCP (Fig. 4B, p > 0.05; n = 6). The lack of effect of ouabain in this instance (compared with its effect to reduce rises in [K+]i evoked by 2-min applications of CCCP immediately after a 5-min exposure to 12.5 mm K+o, compared with control; see below) likely reflects the profound depletion of [ATP]i that occurs during prolonged applications of CCCP (47, 48). In support, 10-min applications of CCCP resulted in an 83% reduction in ATP levels (Fig. 4E). By calculating the cellular ATP content at this time point we determined that astrocyte ATP concentration was 0.036 mm, corresponding to ∼10% Na+,K+-ATPase activity (50), consistent with the finding that ouabain exerts little effect on K+ uptake during the prolonged application of CCCP. Unfortunately, we were unable to examine the potential contribution of plasma membrane Na+-K+-2Cl− co-transport (1, 6) as the inhibitors bumetanide and furosemide resulted in a marked reduction in resting [K+]i (see also Ref. 39), thereby confounding the interpretation of the K+ sequestration experiments. Also, quinine compounds could not be employed to block plasma membrane tandem pore domain K+ (K2P) channels because their intrinsic absorbance and fluorescence at the excitation wavelengths employed for PBFI markedly interfered with the PBFI signals. In summary, these results indicate that Kir, Kdr, and Ka channels play a role in K+ uptake across the plasma membrane during exposure to high [K+]o.

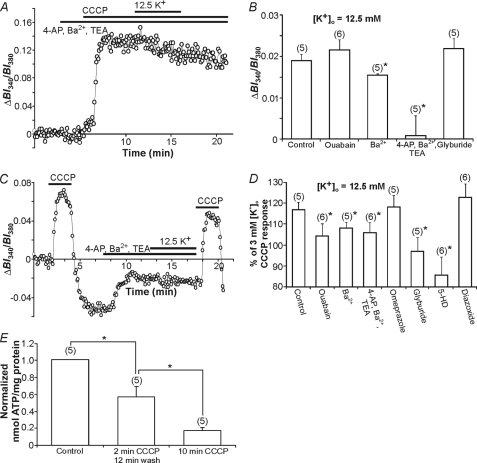

FIGURE 4.

K+ uptake mechanisms in cultured astrocytes. A, a representative trace of the effect of pretreatment with a K+ channel-blocking mixture on the rise in [K+]i evoked by 12.5 mm K+o in the continuous presence of CCCP. B, increases in [K+]i evoked by 5-min applications of 12.5 mm [K+]o during mitochondrial uncoupling with CCCP were significantly reduced in the presence of either 50 μm Ba2+ or a mixture containing 5 mm 4-AP, 3 mm Ba2+, and 1 mm TEA (*, p < 0.05 in each case), whereas no reduction was observed in the presence of 1 mm ouabain or 1 μm glyburide (p > 0.05). C, a representative trace displaying the BI340/BI380 transients (representing [K+]i) evoked by 2-min applications of CCCP prior to and after a 5-min pretreatment with 12.5 mm K+o. The K+ channel blocking mixture significantly attenuated the expected increase in the magnitude of the [K+]i transient evoked by CCCP after exposure to 12.5 mm K+o (compare with Fig. 3A). D, the effects of ouabain, voltage-activated K+ channel inhibitors, omeprazole, glyburide, 5-HD, and diazoxide in experiments of the type shown in C. All test compounds, except diazoxide and omeprazole, significantly reduced the 12.5 mm [K+]o-induced increase in the CCCP response (*, p < 0.05). E, the effect of CCCP application on intracellular ATP levels (nanomole/mg of protein normalized to control). A 2-min application of CCCP followed by a 12-min wash and a 10-min application of CCCP significantly reduced ATP levels (*, p < 0.05). The respective n values are indicated in parentheses. Bars indicate the mean ± S.E.

Next, to examine which plasma membrane K+ uptake routes play a role in mitochondrial K+ sequestration we tested the effects of the same inhibitors by adding them 3–5 min prior to elevating [K+]o to 12.5 mm for 5 min and then applying CCCP at 3 mm K+o for 2 min (Fig. 4, C and D). As illustrated in Fig. 4D, inhibition of inwardly rectifying K+ channels with 50 μm Ba2+ (n = 5) significantly (p < 0.05) reduced the amplitude of the [K+]i transient evoked by CCCP immediately after a 5-min exposure to 12.5 mm K+o, compared with the control response. A K+ channel blocking mixture containing 3 mm Ba2+, 5 mm 4-AP, and 1 mm TEA (to block Kir, Kdr, and Ka channels) also caused a reduction in the response (n = 6; p < 0.05), although the reduction was not significantly different (p > 0.05) to that evoked by 50 μm Ba2+ alone. Inhibition of H+/K+-ATPase activity with omeprazole (100 μm) did not alter mitochondrial K+ sequestration (n = 5; p > 0.05). Finally, compared with control, inhibition of the Na+,K+-ATPase with 1 mm ouabain (n = 6) significantly (p < 0.05 in each case) reduced the amplitude of the [K+]i transient evoked by CCCP immediately after a 5-min exposure to 12.5 mm K+o, suggesting that ATP levels during a 2-min exposure to CCCP remain sufficient to maintain Na+,K+-ATPase activity (47). Indeed, we found that after a 2-min exposure to CCCP followed by a 12-min wash, ATP levels were reduced by 43% (cf. the 83% reduction evoked by a 10-min application of CCCP; Fig. 4E); the calculated cellular ATP concentration was 0.12 mm, corresponding to ∼35% Na+,K+-ATPase activity (50).

Taken together, the aforementioned observations are consistent with previous findings that the plasmalemmal Na+,K+-ATPase and inwardly rectifying K+ channels contribute to K+ influx across the astrocyte plasma membrane (1, 6), and suggest that these pathways contribute to subsequent mitochondrial K+ loading at elevated [K+]o. Nevertheless, K+ sequestration by mitochondria was not entirely blocked by the test compounds used, indicating that other mechanisms must also contribute.

To examine the role of mitochondrial K+ channels in the sequestration of K+ by mitochondria, a variety of inhibitors were utilized under the brief 2-min CCCP application paradigm. The KATP channel blocker 5-HD was used at a concentration that inhibits mito-KATP channels and not plasma membrane KATP channels (500 μm (51)). Application of 5-HD 5 min prior to and during the application of 12.5 mm [K+]o reduced (p < 0.05) the amount of K+ taken up into mitochondria, as assessed by a reduction in the [K+]i transient evoked by the subsequent 2-min application of CCCP at 3 mm K+o (n = 6; Fig. 4D). Consistent with previous findings (38), 5-HD alone had no apparent effect on resting PBFI-derived ratio values but did slightly (p > 0.05) reduce the rise in [K+]i evoked by a 2-min application of CCCP under control (K+o = 3 mm) conditions in the absence of a prior application of elevated [K+]o. Application of glyburide, which inhibits both plasma membrane and mitochondrial KATP channels (52), also reduced mitochondrial K+ sequestration (n = 5; p < 0.05; Fig. 4D). As noted above, glyburide did not act on putative plasma membrane KATP channels indicating that mito-KATP channels are its likely site of action. Application of the mito-KATP channel opener diazoxide at a concentration specific for mitochondrial channels (100 μm) (53) failed to significantly augment the amplitude of the [K+]i transient induced by a 2-min application of CCCP after pretreatment with 12.5 mm K+o (n = 6; p > 0.05; Fig. 4D), indicating that additional mito-KATP opening is not necessary for K+ sequestration by mitochondria. The effects of the K+/H+ exchange blocker, quinine, could not be assessed due to its autofluorescence and timolol, another K+/H+ exchange inhibitor, caused a large reduction in [K+]i under resting conditions (see also Ref. 53) making it difficult to interpret the effect of elevated [K+]o on K+ release evoked by CCCP. Other known mitochondrial K+ channel inhibitors could not be employed due to effects on plasmalemmal K+ channels and/or transporters. For example, compounds that block mito-KCa channels (33) also block plasma membrane KCa channels (55). Taken together, these results are consistent with previous findings that K+ is taken up across the plasma membrane of astrocytes by several routes and suggest that mito-KATP channels are an important route for the subsequent entry of K+ into mitochondria.

The Contribution of Cx43 to Mitochondrial K+ Sequestration

Cx43 is highly expressed in astrocytes (56), is permeable to K+ (57), has been shown using a variety of techniques (including electron microscopy) to be present in mitochondria (58, 59), and has been shown to be important in K+ uptake into isolated mitochondria (24). Therefore, we examined whether Cx43 plays a role in the temporary sequestration of K+ by astrocyte mitochondria.

Initially, we examined whether Cx43 was present in astrocyte mitochondria. As illustrated in Fig. 5, Cx43 protein was observed in whole cell and mitochondrial fractions obtained from wild-type (Cx43+/+) astrocytes. Cx43 staining was absent in Cx43−/− cells (supplemental Fig. S4). These observations suggest that Cx43 is indeed present in astrocyte mitochondria and are consistent with similar findings in cardiac tissue and endothelial cells (57, 60, 61).

FIGURE 5.

Cx43 association with astrocyte mitochondria. An immunoblot of Cx43 expression in whole cell (WC) and mitochondrial (Mito) fractions of Cx43+/+ (+/+) astrocyte cultures. Also indicated are the plasma membrane marker N-cadherin, the mitochondrial marker OxPhos, and GAPDH.

Before examining the role of gap junction proteins in K+ sequestration with the CCCP protocols described above, their involvement in mitochondrial K+ uptake was assessed directly using a protocol that preferentially loads PBFI into mitochondria followed by saponin permeabilization (Fig. 6A). As previously described in cardiomyocytes (24), application of 25 mm K+ caused an increase in mitochondrial PBFI-derived BI340/BI380 ratio values (Fig. 6B). The rate of mitochondrial K+ uptake in Cx43+/+ astrocytes was reduced in the presence of the gap junction blockers CBX (20 μm; Fig. 6B) and AGA (10 μm), and also in Cx43−/− astrocytes examined in the absence of the blockers; the inactive analogue GZA (20 μm) was without effect (Fig. 6C). Additionally, CBX and AGA were ineffective in Cx43−/− astrocytes (Fig. 6C).

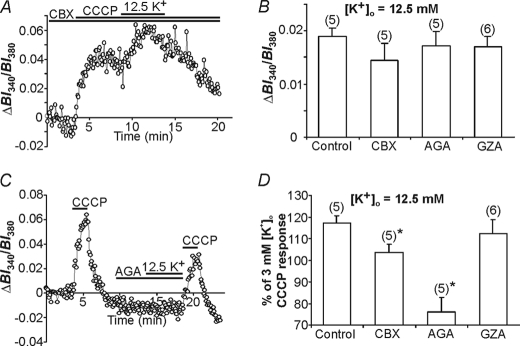

Next, the effects of the gap junction blockers CBX and AGA, and the inactive analogue GZA, were tested on mitochondrial K+ sequestration in situ. During prolonged exposures to CCCP (where ΔΨm is completely dissipated and mitochondrial K+ sequestration is impaired), CBX and AGA failed to inhibit the rise in [K+]i normally evoked by exposure to 12.5 mm K+o (Fig. 7, A and B) suggesting, in turn, that connexon hemichannels do not play a role in K+ uptake at the level of the plasma membrane. In contrast, CBX and AGA significantly attenuated the expected augmentation of the rise in [K+]i induced by a brief (2 min) application of CCCP immediately following exposure to 12.5 mm K+o (Fig. 7, C and D), suggesting that Cx43 plays a role in mitochondrial K+ uptake. The inactive analogue GZA did not affect (p > 0.05) the temporary sequestration of K+ by mitochondria (Fig. 7D). In addition, CBX and AGA were without effect in Cx43−/− astrocytes (p > 0.05; Fig. 8B), confirming the specificity of these compounds in our system. To examine if gap junction coupling plays a role in mitochondrial K+ sequestration, a subset of experiments were performed on solitary astrocytes and results were not significantly different from those obtained in non-solitary cultures (data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

Mitochondrial uptake of K+ is reduced in the presence of gap junction blockers. A, pretreatment with the gap junction blocker CBX (20 μm) did not attenuate the rise in [K+]i in response to the application of 12.5 mm K+o in the continued presence of CCCP. B, changes in [K+]i evoked by 5-min applications of 12.5 mm K+o during mitochondrial uncoupling with CCCP were not reduced in the presence of 20 μm CBX, 10 μm AGA, or 20 μm GZA (p > 0.05 in all cases, compared with control). C, a representative record displaying a reduction in the [K+]i transient evoked by a 2-min application of CCCP after 5 min pretreatment with 12.5 mm K+o in the presence of AGA. D, using the same protocol illustrated in C, the effects CBX and GZA were also examined. All test compounds, except GZA, significantly attenuated (*, p < 0.05) the expected augmentation of CCCP-induced rises in [K+]i following exposure to 12.5 mm K+o. The respective n values are indicated in parentheses. Bars indicate the mean ± S.E.

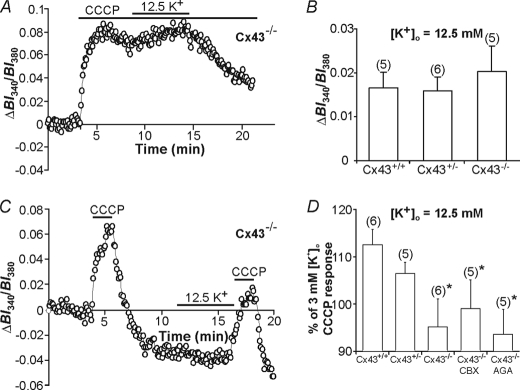

FIGURE 8.

Mitochondrial uptake of K+ is reduced in Cx43−/− astrocytes. A, a representative record of a prolonged CCCP application experiment depicting a rise in [K+]i in response to 12.5 mm K+o application to Cx43−/− astrocytes. B, increases in [K+]i evoked by 5-min applications of 12.5 mm K+o during mitochondrial uncoupling with CCCP were not significantly different (p > 0.05) in Cx43+/+, Cx43+/−, or Cx43−/− astrocytes. C, a representative trace displaying the [K+]i transients evoked by 2-min applications of CCCP in the absence of and after 5 min pretreatment with 12.5 mm K+o in Cx43−/− astrocytes. D, using the same protocol as in C, Cx43−/− astrocytes were found to have a reduced CCCP-induced [K+]i response after high [K+]o exposure in comparison to Cx43+/+ astrocytes (*, p < 0.05), whereas Cx43+/− astrocytes displayed an intermediate response. CBX or AGA were without effect in Cx43−/− astrocytes (p > 0.05). The respective n values are indicated in parentheses. Bars indicate the mean ± S.E.

In support of these results, the rise in [K+]i evoked by 12.5 mm K+o in the continued presence of CCCP was not significantly different in Cx43−/− astrocytes compared with astrocytes obtained from wild-type (Cx43+/+) and heterozygous (Cx43+/−) littermates (Fig. 8, A and B). However, compared with Cx43+/+ astrocytes, cells obtained from Cx43−/− mice exhibited reduced mitochondrial K+ sequestration (p < 0.05; Fig. 8, C and D). An intermediate response, which was not significantly different from that observed in Cx43+/+ and Cx43−/− astrocytes (p > 0.05 in both cases), was observed in Cx43+/− astrocytes (Fig. 8D). In light of the finding that connexon hemichannels do not contribute to K+ uptake across the plasma membrane (see above), the observations that mitochondrial K+ sequestration is inhibited by gap junction blockers and in Cx43-null astrocytes suggest that connexins play a role in K+ sequestration by mitochondria downstream of the plasma membrane.

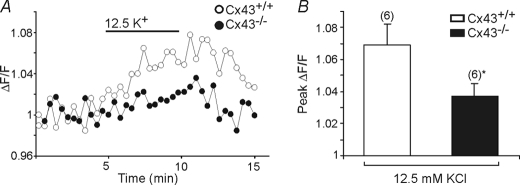

The above results suggest that Cx43 represents a potential pathway for K+ influx into astrocyte mitochondria. To further assess this possibility, in the final series of experiments we compared the effects of high [K+]o on ΔΨm in Cx43+/+ and Cx43−/− astrocytes loaded with the fluorescent voltage sensitive indicator rhodamine-123. Rhodamine-123 is a reliable indicator of ΔΨm and possesses little sensitivity to changes in plasma membrane potential (e.g. Ref. 62). Consistent with a contribution of Cx43 to K+ uptake by astrocyte mitochondria, mitochondrial depolarization in response to the application of 12.5 mm K+o was greater in Cx43+/+ compared with Cx43−/− astrocytes (Fig. 9, A and B).

FIGURE 9.

Mitochondrial membrane potential during elevated [K+]o in Cx43+/+ and Cx43−/− astrocytes. A, changes in ΔF/F values in rhodamine-123-loaded Cx43+/+ and Cx43−/− astrocytes upon exposure to 12.5 mm K+o. B, bar graph summarizing the response to 12.5 mm [K+]o in Cx43+/+ and Cx43−/− astrocytes. The amplitudes of responses to elevated [K+]o were reduced in Cx43−/− astrocytes (*, p < 0.05). The respective n values are indicated in parentheses. Bars indicate the mean ± S.E.

DISCUSSION

Astrocytes have been implicated in K+ buffering for decades (1, 5, 6, 63–66). Although the mechanisms by which astrocytes take up K+o have been extensively studied, how K+ is handled once it enters the cell remains unclear. Although K+ may be redistributed throughout the astroglial syncytium, at least in part via gap junction coupling (4, 67), the short length constants of astrocytic processes may limit K+ redistribution (68) and theories of K+ siphoning through glia have been challenged (69). The results presented here support a role for mitochondria in situ in rapidly sequestering the extracellular K+ that is taken up across the plasma membrane of astrocytes.

Technical Considerations

Despite the potential limitations of PBFI, we found that the dye could be employed as a reliable indicator of increases in [K+]i in intact cells. In agreement with Kasner and Ganz (39) we found no evidence to suggest that changes in [Na+]i within the range observed in the present experiments affect the sensitivity of PBFI to K+ (see also Ref. 44). In addition, as noted under “Results,” previous reports indicate that PBFI (both in vitro and in situ) is relatively insensitive to changes in [Ca2+], [Mg2+], [H+], and osmolarity. Nevertheless, because CCCP is known to cause changes in pH we examined the sensitivity of PBFI to K+ at pH values of 6.5 and pH 8; again in agreement with Kasner and Ganz (39), we found that PBFI fluorescence signals were not altered under these conditions. Finally, changes in [Mg2+]i are unlikely to affect PBFI signals under our experimental conditions because protonophores cause only modest rises in [Mg2+]i and total cellular [Mg2+] is below the threshold to alter the sensitivity of PBFI to K+ (36, 42).

Temporary K+ sequestration by mitochondria was assessed by transiently uncoupling the mitochondria with 2-min applications of CCCP before and after altering [K+]o and the difference between the magnitudes of the CCCP-induced [K+]i transients was taken as a reflection of mitochondrial K+ sequestration. It is unlikely that the [K+]i transients induced by brief applications of CCCP arose from extracellular K+ entry because the [K+]i transients were still observed during the application of the K+ channel blocking mixture, a finding that is consistent with previous reports that indicate that blockade of voltage-activated K+ channels does not alter protonophore-induced changes in plasma membrane currents (47, 49). Despite the possibility that a CCCP-induced disruption of the mitochondrial pH gradient could potentially limit K+ efflux from mitochondria via the mitochondrial K+/H+ exchanger, the application of CCCP in situ (Fig. 2A) and in permeabilized astrocytes (Fig. 2, B and C) caused significant mitochondrial efflux of K+.

K+ Handling by Astrocytes

Separate CCCP application paradigms were used to examine K+ entry through the plasma membrane and mitochondrial K+ sequestration (reflecting K+ fluxes across both the plasma and mitochondrial membranes). Consistent with previous findings, blockade of Kir, Kdr, and Ka channels and also the Na+,K+-ATPase significantly reduced high K+o-induced K+ influx into astrocytes, although technical considerations precluded an examination of the potential involvement of other ion channels (e.g. K2P channels) and transport mechanisms (e.g. Na+-K+-2Cl− co-transport (1, 6)). In contrast, K+ influx across the plasma membrane was not reduced by gap junction blockers or in Cx43-null astrocytes, suggesting that plasma membrane connexon hemichannels are not involved in K+ influx into astrocytes. Because the application of CCCP alters [ATP]i, we also examined the potential role of plasma membrane KATP channels and the H+/K+-ATPase. In neither case were these pathways involved in plasma membrane K+ entry.

The entry of K+ into mitochondria appeared to be mediated, at least in part, by mito-KATP channels. Thus, the mito-KATP channel closer 5-HD inhibited K+ sequestration, although it must be noted that 5-HD can be converted to 5-HD-CoA, which can interfere with mitochondrial function (70). Therefore, we also applied the KATP channel inhibitor glyburide (which did not affect K+ influx across the plasma membrane) and found that mitochondrial K+ sequestration was reduced, indicating that mito-KATP channels are a likely route for mitochondrial K+ entry. We also used diazoxide in an attempt to open mito-KATP channels; however, diazoxide failed to promote additional K+ uptake, suggesting that these channels may have already been open under our experimental conditions. In this regard, it should be noted that the regulation of mitochondrial KATP channels in situ is complex and that at physiological ATP concentrations mito-KATP channels may not be closed because a variety of other mechanisms also play a role in regulating the opening mitochondrial KATP channels in situ (see Ref. 16). Alternatively, diazoxide can inhibit succinate dehydrogenase leading to depolarization of mitochondria (55), which in turn could reduce the driving force for K+ influx into mitochondria. Although we attempted to examine the potential role of the mitochondrial K+/H+ antiporter (16), the fluorescent properties of quinine precluded its use and timolol resulted in a loss of K+ from the cytosol, presumably reflecting its effects on other membrane ion transporters (54).

The Role of Connexin43 in Mitochondrial K+ Uptake

Given the abundance of gap junction proteins in astrocytes (56), their permeability to K+ ions (57), the reported presence of Cx43 on mitochondria (24, 57–60, 71), and their contribution to K+ uptake in isolated mitochondria (24), we employed pharmacological and genetic approaches to examine the potential role of Cx43 in mitochondrial K+ sequestration in situ. The combination of approaches was designed to overcome the limitations of each method. Thus, although we found that AGA and CBX (but not an inactive control) inhibited mitochondrial K+ uptake (with AGA exerting a greater effect, potentially reflecting its higher lipid solubility compared with CBX, which in turn could allow for better permeation across the plasma and mitochondrial membranes), the specificity (or potential lack thereof) of gap junction blockers remained an important consideration. Therefore, we also examined the effects of CBX and AGA in Cx43−/− astrocytes; which was without effect, suggesting these compounds are specific under our experimental conditions. Additional results obtained using the pharmacological approach were also corroborated by a genetic loss-of-expression approach in Cx43+/− and Cx43−/− astrocytes, although this approach also has limitations as Cx43-null astrocytes exhibit altered expression of many genes (72).

Our conclusion that Cx43 contributes to K+ influx into mitochondria was supported by the finding that Cx43 is present in astrocyte mitochondria, as previously reported in mitochondria from cardiac and endothelial tissue (57, 60, 61). Also, a recent report using mitochondria from cardiomyocytes indicate that Cx43 hemichannels locate to the inner mitochondrial membrane and contribute to K+ uptake (24).

It is doubtful that K+ flux through plasmalemmal gap junctions between astrocytes could account for our results because K+o was uniformly applied to our populations of cultured astrocytes and PBFI-derived ratio values measured in individual astrocytes across a population were very similar, making it unlikely that domains of K+ existed to shuttle K+ to neighboring cells connected by gap junctions. Furthermore, mitochondrial K+ sequestration was still observed in solitary astrocytes where cell-cell contacts are absent.

Physiological Implications

It is well established that mitochondria sequester Ca2+ and Na+ from subplasmalemmal [ion]i microdomains that result from ion entry into a cell across the plasma membrane. In the case of Ca2+ ions, it is known that physical linkages exist between subplasmalemmal mitochondria and the endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum, which ensures not only the efficient refilling of ER/SR Ca2+ stores but also acts to limit potentially detrimental cytosolic [Ca2+] elevations (reviewed by Refs. 8 and 45; see also Refs. 10, 12, and 13). This may be analogous to the present results under HEPES-buffered recording conditions where rises in [K+]i were minimal upon exposure to elevated [K+]o, yet a significant increase in mitochondrial K+ was observed.

Interestingly, we also found that there was a larger increase in [K+]i when [K+]o was elevated prior to CCCP exposure and that when [K+]o was lowered to 0 mm there was a smaller CCCP-induced [K+]i response, consistent with the possibility that mitochondria help to maintain [K+]i at a constant level by temporarily sequestering K+ during local elevations in [K+]o/i and by releasing it during reductions in [K+]o/i.

Although it is difficult to assess the amount of K+ that can be taken up by mitochondria, mitochondria occupy up to 7% of the cell volume in astrocytes (73) and can be recruited to lie in close proximity to the plasma membrane (14, 15), suggesting that they could play an important role in buffering K+ influx from the extracellular space to limit potentially detrimental increases in [K+]o.

In addition to sequestration of K+o described in this study, mitochondrial K+ uptake may also serve a beneficial role by facilitating respiration, improving ATP production, reducing mitochondrial permeability transition (74–76), and aiding in cellular protection (21, 75). It remains to be determined whether K+ uptake by mitochondrial Cx43 plays a role in cellular viability under pathological conditions, however, it is known that disruption of Cx43 expression or function in astrocytes increases cellular injury (25, 77).

Supplementary Material

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-aid from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of British Columbia and Yukon (to C. C. N. and C. K.) and Operating Grant MOP-77616 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to J. C.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- [K+]o

- extracellular ion concentration

- AGA

- 18α-glycyrrhetinic acid

- CCCP

- carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone

- CBX

- carbenoxolone

- Cx43

- connexin43

- Cx43+/+

- connexin43 wild-type

- Cx43+/−

- connexin43 heterozygous

- Cx43−/−

- connexin43-null

- [ion]i

- cytoplasmic ion concentration

- FCCP

- carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone

- GZA

- glycyrrhizic acid

- 5-HD

- 5-hydroxydecanoic acid

- ΔΨm

- inner mitochondrial transmembrane potential

- Ka

- A-type potassium channel

- Kdr

- delayed rectifier potassium channel

- Kir

- inward rectifier potassium channel

- K2P

- tandem pore domain potassium channels

- PBFI

- K+-sensitive fluorophore potassium-binding benzofuran isophthalate acetoxymethyl ester

- TEA

- triethanolamine

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- 4-AP

- 4-aminopyridine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walz W. (2000) Neurochem. Int. 36, 291–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somjen G. G. (2002) Neuroscientist 8, 254–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leis J. A., Bekar L. K., Walz W. (2005) Glia 50, 407–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallraff A., Köhling R., Heinemann U., Theis M., Willecke K., Steinhäuser C. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 5438–5447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orkand R. K., Nicholls J. G., Kuffler S. W. (1966) J. Neurophysiol. 29, 788–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kofuji P., Newman E. A. (2004) Neuroscience 129, 1045–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pivovarova N. B., Hongpaisan J., Andrews S. B., Friel D. D. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 6372–6384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poburko D., Lee C. H., van Breemen C. (2004) Cell. Calcium 35, 509–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poburko D., Liao C. H., Lemos V. S., Lin E., Maruyama Y., Cole W. C., van Breemen C. (2007) Circ. Res. 101, 1030–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poburko D., Liao C. H., van Breemen C., Demaurex N. (2009) Circ. Res. 104, 104–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy E., Eisner D. A. (2009) Circ. Res. 104, 292–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reyes R. C., Parpura V. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 9682–9691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azarias G., Van de Ville D., Unser M., Chatton J. Y. (2008) Glia 56, 342–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golovina V. A. (2005) J. Physiol. 564, 737–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolikova J., Afzalov R., Giniatullina A., Surin A., Giniatullin R., Khiroug L. (2006) Brain Cell. Biol. 35, 75–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garlid K. D., Paucek P. (2003) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1606, 23–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernardi P. (1999) Physiol. Rev. 79, 1127–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kowaltowski A. J., Cosso R. G., Campos C. B., Fiskum G. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42802–42807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garlid K. D. (1996) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1275, 123–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walz W. (1992) Neurosci. Lett. 135, 243–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korge P., Honda H. M., Weiss J. N. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 289, H66–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliveira J. M., Jekabsons M. B., Chen S., Lin A., Rego A. C., Gonçalves J., Ellerby L. M., Nicholls D. G. (2007) J. Neurochem. 101, 241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duchen M. R. (2004) Mol. Aspects Med. 25, 365–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miro-Casas E., Ruiz-Meana M., Agullo E., Stahlhofen S., Rodríguez-Sinovas A., Cabestrero A., Jorge I., Torre I., Vazquez J., Boengler K., Schulz R., Heusch G., Garcia-Dorado D. (2009) Cardiovasc. Res. 83, 747–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozog M. A., Siushansian R., Naus C. C. (2002) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 61, 132–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reaume A. G., de Sousa P. A., Kulkarni S., Langille B. L., Zhu D., Davies T. C., Juneja S. C., Kidder G. M., Rossant J. (1995) Science 267, 1831–1834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naus C. C., Bechberger J. F., Zhang Y., Venance L., Yamasaki H., Juneja S. C., Kidder G. M., Giaume C. (1997) J. Neurosci. Res. 49, 528–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diarra A., Sheldon C., Church J. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 280, C1623–1633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murchison D., Griffith W. H. (2000) Brain Res. 854, 139–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murchison D., Zawieja D. C., Griffith W. H. (2004) Cell Calcium 36, 61–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheldon C., Diarra A., Cheng Y. M., Church J. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 11057–11069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ljubkovic M., Marinovic J., Fuchs A., Bosnjak Z. J., Bienengraeber M. (2006) J. Physiol. 577, 17–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu W., Liu Y., Wang S., McDonald T., Van Eyk J. E., Sidor A., O'Rourke B. (2002) Science 298, 1029–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olson J. E., Sankar R., Holtzman D., James A., Fleischhacker D. (1986) J. Cell. Physiol. 128, 209–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bates D. C., Sin W. C., Aftab Q., Naus C. C. (2007) Glia 55, 1554–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minta A., Tsien R. Y. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 19449–19457 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Froschauer E., Nowikovsky K., Schweyen R. J. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1711, 41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu D., Slevin J. R., Lu C., Chan S. L., Hansson M., Elmér E., Mattson M. P. (2003) J. Neurochem. 86, 966–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kasner S. E., Ganz M. B. (1992) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 262, F462–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levi A. J., Lee C. O., Brooksby P. (1994) J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 5, 241–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buckler K. J., Vaughan-Jones R. D. (1998) J. Physiol. 513, 819–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kubota T., Shindo Y., Tokuno K., Komatsu H., Ogawa H., Kudo S., Kitamura Y., Suzuki K., Oka K. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1744, 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stys P. K., Lehning E., Saubermann A. J., LoPachin R. M., Jr. (1997) J. Neurochem. 68, 1920–1928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zoeteweij J. P., van de Water B., de Bont H. J., Nagelkerke J. F. (1994) Biochem. J. 299, 539–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rizzuto R., Pozzan T. (2006) Physiol. Rev. 86, 369–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose C. R., Ransom B. R. (1996) J. Physiol. 491, 291–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Juthberg S. K., Brismar T. (1997) Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 17, 367–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Budd S. L., Nicholls D. G. (1996) J. Neurochem. 66, 403–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park K. S., Jo I., Pak K., Bae S. W., Rhim H., Suh S. H., Park J., Zhu H., So I., Kim K. W. (2002) Pflugers Arch. 443, 344–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jewell E. A., Lingrel J. B. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 16925–16930 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato T., O'Rourke B., Marbán E. (1998) Circ. Res. 83, 110–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang M. K., Lee S. H., Seo H. W., Yi K. Y., Yoo S. E., Lee B. H., Chung H. J., Won H. S., Lee C. S., Kwon S. H., Choi W. S., Shin H. S. (2009) J. Pharmacol. Sci. 109, 222–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garlid K. D., Paucek P., Yarov-Yarovoy V., Murray H. N., Darbenzio R. B., D'Alonzo A. J., Lodge N. J., Smith M. A., Grover G. J. (1997) Circ. Res. 81, 1072–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLaughlin C. W., Peart D., Purves R. D., Carré D. A., Peterson-Yantorno K., Mitchell C. H., Macknight A. D., Civan M. M. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 281, C865–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halestrap A. P., Clarke S. J., Khaliulin I. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 1007–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giaume C., Fromaget C., el Aoumari A., Cordier J., Glowinski J., Gros D. (1991) Neuron 6, 133–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang H. Z., Veenstra R. D. (1997) J. Gen. Physiol. 109, 491–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boengler K., Dodoni G., Rodriguez-Sinovas A., Cabestrero A., Ruiz-Meana M., Gres P., Konietzka I., Lopez-Iglesias C., Garcia-Dorado D., Di Lisa F., Heusch G., Schulz R. (2005) Cardiovasc. Res. 67, 234–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boengler K., Stahlhofen S., van de Sand A., Gres P., Ruiz-Meana M., Garcia-Dorado D., Heusch G., Schulz R. (2009) Basic Res. Cardiol. 104, 141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goubaeva F., Mikami M., Giardina S., Ding B., Abe J., Yang J. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 352, 97–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li H., Brodsky S., Kumari S., Valiunas V., Brink P., Kaide J., Nasjletti A., Goligorsky M. S. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 282, H2124–2133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salvioli S., Ardizzoni A., Franceschi C., Cossarizza A. (1997) FEBS Lett. 411, 77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holthoff K., Witte O. W. (2000) Glia 29, 288–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lian X. Y., Stringer J. L. (2004) Brain Res. 1012, 177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.D'Ambrosio R., Maris D. O., Grady M. S., Winn H. R., Janigro D. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 8152–8162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simard M., Nedergaard M. (2004) Neuroscience 129, 877–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu L., Zeng L. H., Wong M. (2009) Neurobiol. Dis. 34, 291–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen K. C., Nicholson C. (2000) Biophys. J. 78, 2776–2797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Metea M. R., Kofuji P., Newman E. A. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 2468–2471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hanley P. J., Daut J. (2005) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 39, 17–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rodriguez-Sinovas A., Boengler K., Cabestrero A., Gres P., Morente M., Ruiz-Meana M., Konietzka I., Miró E., Totzeck A., Heusch G., Schulz R., Garcia-Dorado D. (2006) Circ. Res. 99, 93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iacobas D. A., Urban-Maldonado M., Iacobas S., Scemes E., Spray D. C. (2003) Physiol Genomics. 15, 177–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pysh J. J., Khan T. (1972) Brain Res. 36, 1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kowaltowski A. J., Seetharaman S., Paucek P., Garlid K. D. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 280, H649–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rousou A. J., Ericsson M., Federman M., Levitsky S., McCully J. D. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287, H1967–1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hansson M. J., Morota S., Teilum M., Mattiasson G., Uchino H., Elmér E. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 741–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakase T., Söhl G., Theis M., Willecke K., Naus C. C. (2004) Am. J. Pathol. 164, 2067–2075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.