Abstract

Dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1), an acidic protein important to the formation of bone and dentin, primarily exists as the processed NH2-terminal and COOH-terminal fragments in the extracellular matrix of the two tissues. Previous in vitro studies showed that the substitution of residue Asp213 by Ala213 (D213A) at a cleavage site blocked the processing of mouse DMP1 in cells. In this study, we generated transgenic mice expressing mutant D213A-DMP1 (WT/D213A-Tg mice) to test the hypothesis that the proteolytic processing of DMP1 is an activation step essential to osteogenesis. By crossbreeding WT/D213A-Tg mice with Dmp1 knock-out (Dmp1-KO) mice, we obtained mice expressing D213A-DMP1 in a Dmp1-KO background; these mice will be referred to as “Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg” mice. Biochemical, radiological, and morphological approaches were used to characterize the skeletal phenotypes of Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice compared with wild-type mice, Dmp1-KO mice, and Dmp1-KO mice expressing the normal Dmp1 transgene. Protein chemistry analyses showed that DMP1 was barely cleaved in the bone of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice, indicating that D213A substitution effectively blocked the proteolytic processing of DMP1 in vivo. While the expression of the normal Dmp1 transgene completely rescued the phenotypic skeletal changes of the Dmp1-KO mice, the expression of the mutant D213A-Dmp1 transgene failed to do so. These results indicate that the full-length form of DMP1 is an inactive precursor and its proteolytic processing is an activation step essential to the biological functions of this protein in osteogenesis.

Keywords: Bone, Extracellular Matrix Proteins, Post-translational Modification, Protein Chemistry, Protein Processing, Dentin Matrix Protein 1, Mineralization, Osteogenesis

Introduction

Dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1),2 first identified by cDNA cloning using a rat odontoblast mRNA library, was originally postulated to be dentin-specific (1). Several research groups later demonstrated that DMP1 is also expressed in bone (2, 3, 4) at more abundant levels than in teeth (5, 6, 7, 8). Mouse and human genetic studies have demonstrated that the inactivation of DMP1 leads to osteomalacia/rickets and dentin hypomineralization, indicating that this protein plays crucial roles in osteogenesis and dentinogenesis (9, 10, 11, 12). The major histopathological changes resulting from DMP1-deficiency include an excess accumulation of osteoid in the bone and widening of predentin in the tooth. Although these data have established an association between DMP1 and the formation of healthy mineralized tissues, the exact mechanistic pathways by which this protein participates in vital steps leading to the formation of healthy bone and dentin are unclear.

In the extracellular matrix (ECM) of bone and dentin, DMP1 mainly occurs as the proteolytically processed fragments originating from the NH2-terminal and COOH-terminal regions of the DMP1 amino acid sequence, respectively (7). The NH2-terminal fragment of DMP1 (designated as “DMP1-N”) exists in two forms: the 37-kDa fragment (7) and the proteoglycan form referred to as “DMP1-PG” (13), while the COOH-terminal fragment (designated as “DMP1-C”) is present as the 57-kDa fragment (7). DMP1-PG contains a single glycosaminoglycan chain (13), while DMP1-C is not glycosylated, but highly phosphorylated (7). Recently, the full-length form of DMP1 has been detected in the ECM of bone and dentin at a remarkably lower level than in its processed fragments (14).

In vitro mineralization studies have shown that DMP1-C and the 37-kDa fragment promote the nucleation of hydroxyapatite crystals whereas the full-length DMP1 and DMP1-PG inhibit their growth (15, 16). Immunohistochemistry and protein chemistry studies showed that the localization of DMP1-N is different from that of DMP1-C in the tooth and cartilage of the long bone (17, 18). These observations in both bone and tooth suggest that the NH2-terminal fragment and the COOH-terminal fragment of DMP1, which vary dramatically in chemical structure, may play different roles in osteogenesis and dentinogenesis. These findings also suggest that the proteolytic processing of DMP1, which releases DMP1-N and DMP1-C, may be important for this protein to exert its functions during the formation of bone and dentin.

Our recent protein chemistry work showed that rat DMP1 is proteolytically processed into DMP1-N and DMP1-C at four peptide bonds: Phe189-Asp190, Ser196-Asp197, Ser233-Asp234, and Gln237-Asp238 (7). A subsequent in vitro study demonstrated that bone morphogenetic protein-1 (BMP-1)/tolloid-like proteinases cleave the bacterium-made full-length form of rat DMP1 at the peptide bond Ser196-Asp197 (19). Amino acid sequence alignment showed that residues Ser196 and Asp197 and their flanking regions in the rat DMP1 are highly conserved across a very broad range of species, suggesting that the proteolytic cleavage at this site may be related to an important biological function (20). Speculating that the Ser196-Asp197 bond is a critical cleavage site for the proteolytic processing of DMP1, we replaced Asp213 with Ala213 in the mouse DMP1 amino acid sequence, which corresponds to Asp197 in the rat DMP1. Transfection experiments showed that this D213A substitution effectively blocked the proteolytic processing of mouse DMP1 in eukaryotic cells (21). In the present study, we generated transgenic mice expressing mutant D213A-DMP1, in which Asp213 was replaced by Ala213. The results from this investigation revealed that D213A-DMP1 was barely cleaved in the mouse bone, and the expression of this mutant protein failed to rescue the phenotypic changes in the skeleton of the Dmp1-KO mice, while the expression of the normal Dmp1 transgene completely corrected the skeletal phenotypes in the Dmp1-KO mice.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Transgenic Mice Expressing D213A-Dmp1 Transgene

A pBC-KS construct containing a 3.6-kb rat Col 1a1 promoter upstream of the mouse DMP1 cDNA (22) was used to generate the targeting transgene. A detailed description of the specificity of the Col 1a1 promoter and its use for driving the expression of a normal Dmp1 transgene to rescue Dmp1-KO phenotypes was described previously (22). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on this construct to generate the cDNA encoding a mutant DMP1 (designated “D213A-DMP1”), in which Asp213 was substituted by Ala213 (21). This substitution, which created an extra AfeI restriction enzyme site in the mutant cDNA, was confirmed by AfeI digestion and DNA sequencing. The restriction enzymes SacII and SalI (New England Biolabs) were used to release a 7.2-kb fragment containing the 3.6-kb rat Col 1a1 promoter, 1.6-kb intron l of the Col 1a1 gene, 1.6-kb mouse DMP1 cDNA (encoding D213A substitution) and an SV40 later poly(A) tail from the construct. This 7.2-kb fragment, referred to as the “Dmp1-D213A transgene”, was used for pronuclear injection at the Brown Foundation Institute of Molecular Medicine of the University of Texas-Houston Health Science Center to generate transgenic founders with a C57BL/6J background.

From two microinjections, we obtained six independent founders that expressed the Dmp1-D213A transgene. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis detected DMP1 mRNA in the skin from the six lines of transgenic mice, indicating that the transgene was active, since the skin of wild type mice does not express DMP1. The expression of the Dmp1-D213A transgene in the skeleton was confirmed by quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR), Western immunoblotting and immunohistochemical staining (see below).

The transgenic founders expressing the Dmp1-D213A transgene in the wild type background were designated as “WT/D213A-Tg” mice. Three of the six transgenic founders were used for crossbreeding with the Dmp1-KO mice (9, 23).

Generation of Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg Mice

The homozygous Dmp1-KO (i.e. Dmp1−/−) male mice were crossbred with Dmp1-D213A transgenic female mice that were heterozygous for the Dmp1-null allele (i.e. Dmp1+/−) to produce mice expressing the Dmp1-D213A transgene but lacking the endogenous Dmp1 (i.e. Dmp1−/−). The homozygous Dmp1-KO mice carrying the Dmp1-D213A transgene are referred to as “Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg” mice. The Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice derived from the three mouse lines had very similar phenotypes in their skeletons, although the expression levels of the Dmp1-D213A transgene were different.

The skeletal phenotypes of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice were compared with 1) wild type (WT), 2) Dmp1-KO, 3) Dmp1-KO mice expressing normal Dmp1 transgene (Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg), and 4) WT/D213A-Tg mice. The generation and characteristics of Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg mice have been well described in previous publications (6, 10, 22, 23).

Genotyping by PCR

Genotyping for the mutant mice was performed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA extracted from the mouse tails, using three sets of primers. To identify D213A-Dmp1 or normal Dmp1 transgene, we used primers p-Tg1 (5′-CAGTGAGTCATCAGAAGAAAGTCAAGC-3′) and p-Tg2 (5′-GGGGTATCTTGGGCACTGTTTTC-3′). When primers p-Tg1 and p-Tg2 were used, the PCR product derived from the transgene templates was 332 bp, while that from the endogenous genomic DNA was 1832 bp, since the sequence of the forward primer p-Tg1 was from exon 5 and that of the reverse primer p-Tg2 was from exon 6 in the mouse Dmp1 gene. Primers p-lacZ1 (5′-GAGTGCGATCTTCCTGAGGCCGATACTGTC-3′) and p-lacZ2 (5′-CGCGGCTGAAATCATCATTAAAGCGAGTGG-3′) were used for the identification of the null Dmp1 allele (expected PCR product, 461 bp), since the Dmp1-KO mice generated by the lacZ knock-in approach contained the β-galactosidase-encoding lacZ gene (23). Primers p-WT1 (5′-GCCCCTGGACACTGACCATAGC-3′) and p-WT2 (5′-CTGTTCCTCACTCTCACTGTCC-3′) were used to detect the wild-type allele (expected PCR product, 400 bp). The sequence of the forward primer p-WT1 was from intron 5, while the reverse primer p-WT2 was from exon 6 of the mouse Dmp1 gene; the sequence of p-WT1 was present in the endogenous Dmp1 gene but not in the Dmp1-null allele. These three sets of primers were used to distinguish among the WT, Dmp1-KO, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice. For example, when the genomic DNA extracted from the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice was used as the template, PCR analysis using primers p-Tg1 and p-Tg2 generated the transgene-specific 332 bp product, and primers p-lacZ1 and p-lacZ2 gave rise to the lacZ gene-specific 461-bp product, while analysis using primers p-WT1 and p-WT2 produced no defined DNA bands.

qRT-PCR

To assess the level of D213A-Dmp1 transgene expression in the skeleton, we performed qRT-PCR using total RNA isolated from the mouse long bone as the template. The primers used for qRT-PCR were p-RT1 (5-AGTGAGTCATCAGAAGAAAGTCAAGC-3′) and p-RT2 (5′-CTATACTGGCCTCTGTCGTAGCC-3′). The sequence of the forward primer p-RT1 was from exon 5, while that of the reverse primer p-RT2 was from exon 6 of the mouse Dmp1 gene. For qRT-PCR, total RNA was extracted from the long bone of 6-week-old Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg and WT mice (n = 3, for each group) using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a QuantiTect Rev Transcription Kit (Qiagen). The mean values from triplicate analyses were compared. The qRT-PCR reactions were performed using Brilliant SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and the Stratagene MX4000 Real-Time PCR Detection System. The PCR conditions were: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 30 s. The PCR product accumulation was monitored by the increase in fluorescence intensity caused by the binding of SYBR Green to double-stranded DNA. The levels of D213A-Dmp1 transgene in the three transgenic mouse lines were expressed as fold change relative to the level found in WT mice.

Extraction and Separation of Non-collagenous Proteins (NCPs) and Detection of DMP1

NCPs were extracted from the long bones of 6-week-old WT, Dmp1-KO, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice, as previously described (14). The NCPs in the extracts were separated by a 10 ml Q-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) column connected to a fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system (GE Healthcare). The gradient employed for the Q-Sepharose ion-exchange chromatography was 0.1–0.8 m NaCl in a 6 m urea solution at pH 7.2. NCPs, including DMP1 and its fragments, eluted into 120 0.5-ml fractions. The full-length form of DMP1 and its processed fragments mainly eluted in fractions 40–52 when the 10 ml Q-Sepharose column was used in the FPLC chromatography. 60-μl samples (in 6 m urea solution) from these chromatographic fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblotting, and particular attention was paid to the presence/absence and quantity of DMP1 and its processed fragments.

For Western immunoblotting, we used the polyclonal anti-DMP1-C-857 antibody, which was purified by passing it through an affinity column made of synthetic peptide injected into the rabbits to generate the antisera (18). This affinity-purified anti-DMP1 antibody was used at a concentration of 0.2 μg IgG/ml. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) at a dilution of 1:5000 was employed as the secondary antibody for the Western immunoblotting analysis. The blots were incubated in the chemiluminescent substrate CDP-star (Ambion) for 5 min and exposed to x-ray films (Kodak).

Digestion of DMP1 by BMP-1

To test if BMP-1 cleaves the mutant DMP1, we incubated the protein sample from the chromatographic fractions containing normal DMP1 (from the Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg mice) and D213A-DMP1 (from the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice) with recombinant human BMP-1 (R&D Systems). For these in vitro enzyme assay experiments, the protein samples in the fractions containing DMP1 were first desalted by dialysis against water. After lyophilization, the protein samples were suspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl solution (pH 7.5) and incubated with BMP-1 at an enzyme/substrate (lyophilized protein) ratio of 1:20 (by weight), as previously described (19). The digestion products were analyzed by Western immunoblotting using the affinity-purified anti-DMP1-C-857 antibody. For these Western immunoblotting analyses, a protein sample equal to 300 μl of the original solution in corresponding chromatographic fractions was loaded into each well.

Tissue Preparation and Immunohistochemistry

Under anesthesia, mice at the ages of 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months were perfused from the ascending aorta with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer. The hind legs were dissected and further fixed in the same fixative for 48 h, followed by demineralization in 8% EDTA containing 0.18 m sucrose (pH 7.4) at 4 °C for ∼2 weeks. The tissues were processed for paraffin embedding, and serial 5-μm sections were prepared.

For the immunolocalization of DMP1 in bone, the monoclonal anti-DMP1-C-8G10.3 antibody (24) was used at a dilution of 1:800; for the detection of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) in bone, a monoclonal antibody against mouse FGF23 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was used at a dilution of 1:400. All immunohistochemistry experiments were performed using the ABC kit and DAB kit (Vector Laboratories Inc.), following the manufacturer's instructions.

X-ray Radiography and Microcomputed Tomography (μ-CT)

The long bones from the 6-week, 6-month, and 12-month-old mice were dissected from the five types of mice and were analyzed by x-ray radiography (piXarray 100, Micro Photonics) and by a μ-CT35 imaging system (Scanco Medical, Basserdorf, Switzerland). The μ-CT analyses included: 1) a medium-resolution scan (7.0 μm slice increment) of the whole femur from the 6-week-old mice for an overall assessment of the shape and structure; 2) a high-resolution scan (3.5 μm slice increment) of the femoral midshaft region (midway between the two epiphyses along the cranial-caudal axis, 100 slices) for analysis of the cortical bone; 3) a high-resolution scan (3.5 μm slice increment) of the femoral metaphysis region proximal to the distal growth plate for evaluation of trabecular bones. For trabecular bone analyses, we selected a cylinder area in the center of the metaphysis region with a radius of 100 μm and a length of 1400 μm (400 slices); the cortical shell was excluded in these trabecular bone analyses. The data acquired from the high-resolution scans were used for quantitative analyses. The quantitative μCT parameters obtained and analyzed using the Scanco software included: bone volume to total volume ratio (BV/TV), apparent density, material density, trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp). The data are reported as mean ± S.D.

Histology

Demineralized specimens for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining were prepared in the same way as described in the immunohistochemistry protocol. To prepare undemineralized sections, specimens were embedded in methylmethacrylate and cut in 6-μm thick sections using a Leica 2165 rotary microtome (Leica). These undemineralized sections were stained by Goldner's Masson Trichrome stain, as previously described (11), to compare the quantity of osteoid in the bone among the WT, Dmp-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice. In Goldner's Masson Trichrome staining, unmineralized osteoid, and collagen stains red or orange, while fully mineralized bone matrix stains green.

Double Fluorochrome Labeling

To visualize the mineral deposition and compare the mineralization rate in the bone of WT, Dmp-KO, and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice, double fluorescence labeling was performed as previously described (22). Briefly, 5 mg/kg of calcein-green (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the abdominal cavity of 5-week-old mice, and 20 mg/kg of Alizarin red (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected 1 week later. The mice were sacrificed 48 h after the injection of Alizarin red, and their long bones were removed and fixed in 70% ethanol for 48 h. The specimens were dehydrated and embedded in methylmethacrylate without prior demineralization. 10 μm sections were cut with a Leitz 1600 saw microtome. The unstained sections were viewed under epifluorescent illumination using a Nikon E800 microscope interfaced with Osteomeasure histomorphometry software.

Serum Biochemistry

The levels of serum phosphorus in 6-week-old WT, Dmp1-KO, and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg (n = 5 for each group) were measured using the phosphomolybdate-ascorbic acid method, while the serum FGF23 level was determined with a FGF23 ELISA kit (Kainos Laboratories), as previously described (11). The data analysis was performed with the Bonferroni method for two-group comparison and one-way ANOVA for multiple group comparison. If significant differences were found with the one-way ANOVA, the Bonferroni method was used to determine which groups were significantly different from others. The quantified results were reported as mean ± S.E. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software.

RESULTS

Expression of D213A-Dmp1 Transgene

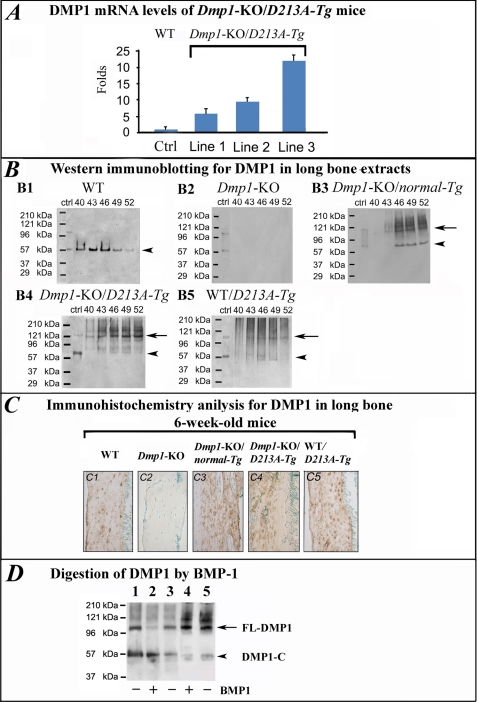

The bone from all three lines of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice showed higher levels of DMP1 mRNA compared with the WT mice (Fig. 1A). Different expression levels for the transgene were observed among the three lines of Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice: the DMP1 expression level of line 1 was ∼8-fold that of the WT mice; line 2 was ∼10-fold, and line 3 was ∼22-fold that of WT. We characterized the skeleton in all of the three transgenic mouse lines. Although the mRNA levels of the Dmp1-D213A transgene were different for the three mouse lines, their skeletal phenotypes were very similar. In this report, the skeletal phenotypes of line 2 are used to illustrate the skeletal changes of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg transgene and digestion of DMP1 by BMP-1. A, mRNA levels of DMP1 in the three lines of Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice. The levels of DMP1 mRNA in the bone were determined by qRT-PCR. The level of DMP1 mRNA in the bone of the WT mice was taken as 1 while that of each of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mouse lines was expressed as fold of the WT control (Ctrl). Note that the levels of DMP1 mRNA in the three lines of transgenic mice were higher than in the WT mice. The data represent the mean values from triplicates. B, detection of DMP1 and its fragments in the bone extracts. NCPs from the long bone of 6-week-old WT, Dmp1-KO, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice were separated by Q-Sepharose anion-exchange chromatography. The chromatographic fractions containing DMP1 and its processed fragments were analyzed by Western immunoblotting with the anti-DMP1-C-857 antibody. The amounts of NCPs extracted from 20 legs (i.e. five mice) from each group were sufficient for the detection and comparison of the full-length form of DMP1 and/or its processed fragments by Western immunoblotting. Long arrows represent the full-length form of DMP1. Arrowheads indicate the position of the COOH-terminal fragment of DMP1. Numbers at the top of each figure represent the anion-exchange chromatographic fractions (i.e. fractions 40–52). Ctrl: 2 μg of purified DMP1 extracted from rat long bone was used as a positive control. 60 μl of sample in 6 m urea solution from each fraction was loaded; when using this amount of sample, only the COOH-terminal fragment of DMP1 was detected in the WT mice. In the Dmp1-KO mice, neither the full-length nor the fragment form of DMP1 was observed. In the Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg mice, both the full-length and fragment forms were detected. In the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice, only the full-length form of DMP1 was detected. In the WT/D213A-Tg mice, both the full-length and fragment forms were detected. These findings indicated that D213A substitution blocked the proteolytic processing of mouse DMP1 in bone. C, immunolocalization of DMP1. The specimens were from the diaphysis region of the tibia from five types of mice at 6 weeks of age. The primary antibody used in the immunohistochemistry was the anti-DMP1-C-8G10.3 antibody. Except for the Dmp1-KO mice, DMP1 was detected in the osteocytes and the matrix surrounding these cells. The three types of transgenic mice showed higher levels of DMP1 expression compared with the WT mice. Note that the signals for DMP1 were observed in the ECM of bone from the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice, suggesting that the uncleaved DMP1 was secreted into the matrix (i.e. not trapped in the cells). D, digestion of DMP1 by BMP-1. The normal DMP1 and D213A-DMP1 were incubated with BMP-1. The two types of DMP1 were isolated from the bone of the Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg mice (lanes 2 and 3) and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice (lanes 4 and 5), respectively. Ctrl (lane 1) was 2 μg of DMP1 extracted from rat long bone. The digestion products were analyzed by Western immunoblotting using the anti-DMP1-C-857 antibody. Note that the majority of the full-length form of the normal DMP1 was cleaved into fragments (lane 2) by BMP-1, while D213A-DMP1 was not processed at all (lane 4). Lane 3, normal DMP1 not incubated with BMP-1; lane 5, D213A-DMP1 not incubated with BMP-1. FL-DMP1: full-length form of DMP1 (arrow); DMP1-C: the COOH-terminal fragment of DMP1 (arrowhead).

Western immunoblotting was used to examine the expression of the D213A-Dmp1 transgene at the translational level and determine if the mutant D213A-DMP1 was processed into 37-kDa and 57-kDa fragments. The chromatographic fractions 40–52 of bone extracts from the five types of mice were evaluated by Western immunoblotting (Fig. 1B). When 60 μl of the urea-containing sample was loaded onto SDS-PAGE, the fragments were clearly detected in the NCP extracts from the bone of WT mice although the full-length form of DMP1 was not present. Both the fragments and the full-length form of DMP1 were observed in the extracts from Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg and WT/D213A-Tg mice. Significant amounts of the full-length DMP1 were detected in the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice, although its fragments were not observed when 60 μl of the urea-containing sample was loaded (Fig. 1B). When a large volume of the sample (e.g. 300 μl of sample concentrated to a small volume) from Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice was loaded onto SDS-PAGE, very weak protein bands matching the COOH-terminal fragment of DMP1 were observed, indicating that trace amounts of D213A-DMP1 were cleaved. In the Dmp1-KO mice, no DMP1 signal was detected by the anti-DMP1 antibody. These results indicate that the D213A substitution effectively blocked the proteolytic processing of DMP1 in the mice.

Immunohistochemistry was employed to evaluate the tissue/cell localization of DMP1. In both WT mice and the three types of transgenic mice (Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, WT/D213A-Tg, and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg), the DMP1 signals were associated with osteocytes; they were either in the osteocytes or in the matrix surrounding these cells (Fig. 1C). The bone of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice appeared to have more osteocytes than that of the WT mice. The DMP1 signals were observed in the ECM of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice, suggesting that uncleaved DMP1 was secreted in the matrix. While the DMP1 expression levels in the long bones was similar among the Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg and WT/D213A-Tg mice (Fig. 1C), the immunohistochemical signals for DMP1 were stronger in the three types of transgenic mice than in the WT mice. As the animals aged, the quantitative difference in the DMP1 signals between Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg and WT mice became more remarkable. The difference in the osteocyte counts between the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg and WT mice also diverged significantly with advancing age (data not shown).

BMP-1 Cleaves Normal DMP1 but Not D213A-DMP1

The in vitro enzyme assay experiments showed that the majority of DMP1 extracted from Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg mice was processed by BMP-1 (lane 2 in Fig. 1D), whereas D213A-DMP1 extracted from the bone of Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice was not cleaved at all (lane 4 in Fig. 1D). These results indicate that BMP-1 cleaves DMP1 at the NH2 terminus of Asp213 in the mouse DMP1.

X-ray and μ-CT Analyses

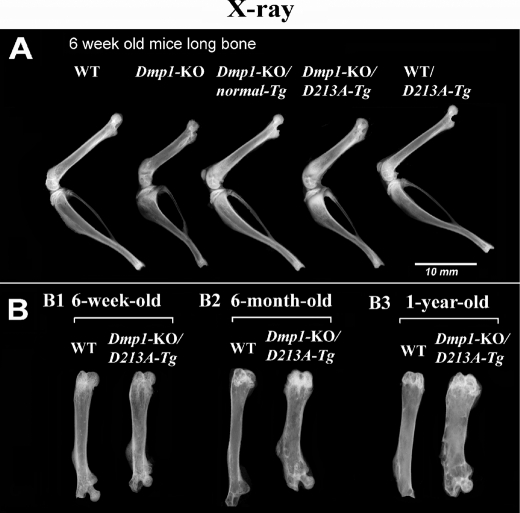

X-ray radiography showed that the length of the long bone of the Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg and WT/D213A-Tg mice was similar to that of the WT mice. The long bone of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice, although slightly longer than that of the Dmp1-KO mice, was shorter and wider than the WT mouse bone (Fig. 2A). At the ages of 6 and 12 months, the shortness defect of the long bone in the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice remained the same compared with the WT mice, while the difference in the width of the tibia became more pronounced between the two types of mice (Fig. 2B). Because of shortened vertebral bodies, the tail of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice was also shorter than that of the WT mice (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

X-ray analysis of the skeletons. The hind leg bones from the WT, Dmp1-KO, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice were analyzed by x-ray. A, comparison of the hind leg bones from 6-week-old WT, Dmp1-KO, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice. The hind leg bones of the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice were shorter and wider than those of the WT mice. The hind leg bones of the Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg and WT/D213A-Tg mice were the same length and thickness as those of the WT mice. The bone density in the midshaft region of tibia in the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice appeared lower than in the WT mice. B, comparison of femurs between WT and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice at the ages of 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months. As the animals aged, the phenotypic changes in the skeleton of Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice, compared with the WT mice, became more profound. In particular, the difference in the width of the femur became more remarkable between the WT and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice with advancing age.

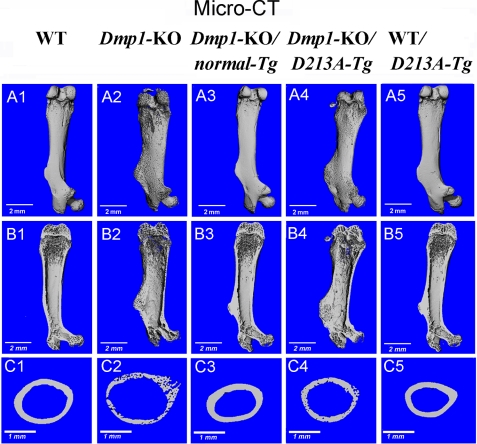

The μ-CT analyses showed that the femur structures were similar among the WT, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice, while the structures and mineralization levels of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg were similar to those of the Dmp1-KO mice (Fig. 3). There were more unmineralized areas appearing as hollow holes in both the outer and inner surfaces of the femur in the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg and Dmp1-KO mice; the femurs of these mice were more porous than those of the WT mice (Fig. 3, A and B). The cross-sectional view of the midshaft region shows the presence of poorly organized cortical bone in the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg and Dmp1-KO mice (Fig. 3C), which was consistent with the histological analyses indicating the abundance of osteoid tissues in the areas that would normally be occupied by well-mineralized cortical bone. The BV/TV, apparent density and material density in the cortical bone of the femoral mid-shaft region of the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice were significantly lower than in the WT mice (Table 1), indicating a lower level of mineralization in the cortical bone of the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice. Phenotypic changes in the trabecular bone structure were also observed in Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice, when compared with WT mice (Table 2).

FIGURE 3.

μ-CT analyses. The femurs from 6-week-old WT, Dmp1-KO, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice were analyzed by μ-CT. A1–A5, μ-CT images showed that the femurs of Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice had enlarged metaphyses and reduced bone length compared with the WT and two other types of mutant mice. The bone surfaces of the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice appeared rough and porous. B1–B5, in the μ-CT images of the longitudinal sections of the femurs, rough inner surfaces with enlarged metaphyses and smaller secondary ossification centers were seen in the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice. C1–C5, three-dimensional reconstructions of the midshaft region of the femoral cortical bones. Note that a large number of hollow holes were seen in the cross sections of the cortical bone from the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice.

TABLE 1.

Quantitative μ-CT analyses of the cortical bone (the midshaft region) of the femurs from 6-week-old WT, Dmp1-KO, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice

| Variables | WT | Dmp1-KO | Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg | Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg | WT/D213A-Tg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± S.D. | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 |

| BV/TVa | 0.96 ± 0.13 | 0.54 ± 0.04b | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.66 ± 0.11b | 0.93 ± 0.14 |

| Apparent density (mg/cm3)c | 966 ± 16 | 513 ± 34b | 807 ± 15b | 669 ± 20b | 935 ± 34 |

| Material density (mg/cm3)d | 1038 ± 25 | 804 ± 36b | 938 ± 17 | 853 ± 44b | 1014 ± 23 |

a BV/TV: ratio of bone volume (BV) to total volume (TV).

b Significant difference from WT mice (p < 0.05).

c Apparent density (expressed as milligram of mineral/cm3): total mineral contents divided by total volume.

d Material density (expressed as milligram of mineral/cm3): total mineral contents divided by bone volume.

TABLE 2.

Quantitative μ-CT analyses of the trabecular bone in the femoral metaphysis region proximal to the distal growth plate from 6-week-old WT, Dmp1-KO, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice

| Variables | WT | Dmp1-KO | Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg | Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg | WT/D213A-Tg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± S.D. | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 |

| BV/TVa | 0.082 ± 0.003 | 0.069 ± 0.017b | 0.091 ± 0.012 | 0.223 ± 0.042b | 0.944 ± 0.021 |

| Tb.N (mm) | 4.031 ± 0.117 | 2.696 ± 0.223b | 3.987 ± 0.210 | 9.732 ± 0.143b | 4.245 ± 0.112 |

| Tb.Th (mm) | 0.019 ± 0.002 | 0.026 ± 0.009b | 0.020 ± 0.006 | 0.023 ± 0.007b | 0.018 ± 0.006 |

| Tb.Sp (mm) | 0.227 ± 0.012 | 0.345 ± 0.059b | 0.301 ± 0.009 | 0.079 ± 0.004b | 0.342 ± 0.012 |

a BV/TV: bone volume (BV) to total volume (TV) ratio.

b Significant difference from WT mice (p < 0.05).

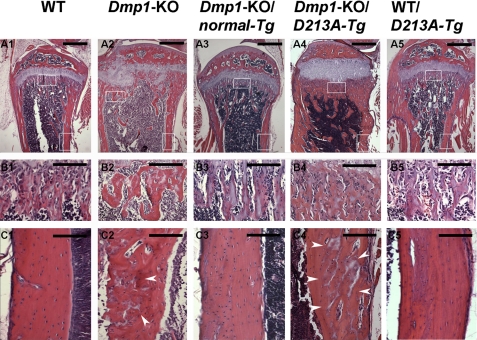

Histological Changes in the Skeleton of Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg Mice

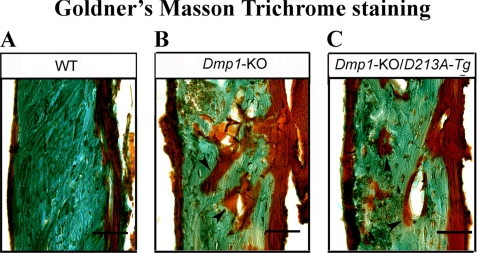

H&E staining demonstrated that the skeletal phenotypes were similar among the WT, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg and WT/D213A-Tg mice. The skeletons of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice were similar to those of the Dmp1-KO mice (Fig. 4). Compared with the WT mice, the femurs of the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice had the following histological characteristics: 1) the bone was shorter and wider; 2) the trabecular bone in the metaphysis region was disorganized; and 3) more osteoid was present. Goldner's Masson Trichrome staining (Fig. 5) showed that the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mouse bone had more osteoid (red/orange) and less mineralized bone (green) than the WT mouse bone.

FIGURE 4.

H&E staining. These specimens were from the tibia of 6-week-old WT, Dmp1-KO, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice. A1–A5, lower magnification of the upper portion of the tibia. Note the disorganized trabeculae, disorganized and expanded growth plates, enlarged metaphyses, and smaller secondary ossification centers in the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mouse tibia, compared with the WT, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice. Bars, 500 μm. B1–B5, enlarged view of the trabecular bone area in the metaphyseal region (upper boxed areas in Fig. 3, A1–A5). In comparison with the WT, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg, and WT/D213A-Tg mice, the bones in the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice had disorganized trabeculae with widespread osteoid and wider osteoid seams. Bars, 30 μm. C1–C5, enlarged view of the cortical bone from the diaphysis region (lower boxed areas in Fig. 3, A1–A5). White arrowheads indicate osteoid in the bone matrix. Note that there was remarkably more osteoid (accounting for more cortex porosity in the μ-CT images) in the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice than in the WT, Dmp1-KO/normal-Tg and WT/D213A-Tg mice. Bars, 20 μm.

FIGURE 5.

Goldner's Masson Trichrome staining. The specimens were from the diaphysis region of the tibia of 6-week-old WT (A), Dmp1-KO (B), and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg (C) mice. The tibia of the Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice had remarkably more osteoid and poorly mineralized cortical bone (shown in “red”) than of the WT mice. Bars, 20 μm.

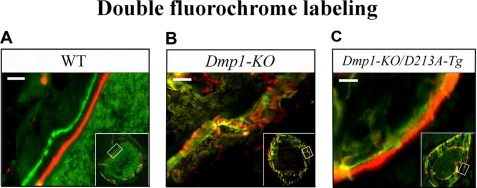

Double Fluorochrome Labeling

A clear space between the defined green and red zones was observed in the WT mice (Fig. 6A). The mineral deposition was irregular (i.e. the green and red colors were mixed) in the Dmp1-KO mice (Fig. 6B). In the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice (Fig. 6C), the green and red zones were slightly more defined than in the Dmp1-KO mice, but the two zones still lacked definition, making it difficult to distinguish between the two. Due to the irregular mineral deposition in the bone of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg and Dmp1-KO mice, it was not possible for us to measure the distance between the green and red zones, because the fluorescence-labeled zones had no clear boundaries. Nevertheless, we assumed that the mineralization rate in the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg and Dmp1-KO mice was lower than in the WT mice, based on the histological appearance.

FIGURE 6.

Double fluorochrome labeling. The specimens were from the tibia of 6-week-old WT (A), Dmp1-KO (B), and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg (C) mice. In the WT mouse bone, two distinct zones of labeling were clearly seen. The distance between these two labeled zones reflects the mineralization rate. The bone from the Dmp1-KO mice showed diffused fluorescent labeling indicating disordered mineral deposition and lower mineralization rate compared with the WT mice. It appeared that the organization of the mineral deposition in the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice was slightly better than in Dmp1-KO, but was far from the normal appearance seen in the WT mice. Bars, 10 μm.

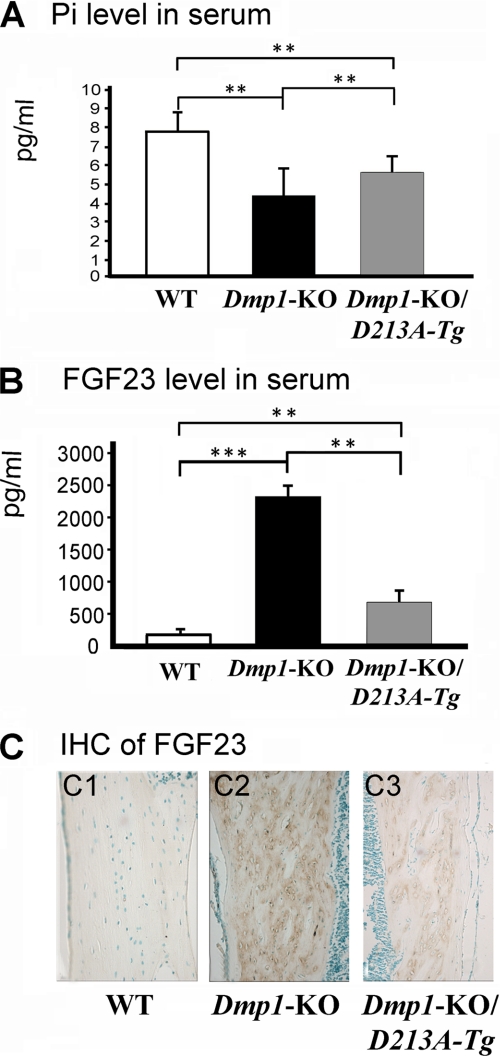

Levels of Phosphorus and FGF23 in the Serum and FGF23 in Bone

The serum phosphorus level in the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice was higher than in the Dmp1-KO mice and but lower than in the WT mice (Fig. 7A). The level of serum FGF23 in the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice was lower than in the Dmp1-KO mice, but higher than in the WT mice (Fig. 7B). The results from the anti-FGF23 immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 7C) agreed with the serological tests, i.e. the level of FGF23 in the bone of Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg was higher than in the WT mice but lower than in the Dmp1-KO mice.

FIGURE 7.

Levels of serum phosphate, serum FGF23, and expression levels of FGF23 in bone. A, phosphate (Pi) concentrations in the sera of 6-week-old WT, Dmp1-KO, and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice. Data were mean ± S.E. (n = 5). **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. The serum Pi level in Dmp1-KO mice was significantly lower than in the WT mice (p < 0.01). The serum Pi level in Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice was significantly lower than in WT mice (p < 0.01) but higher than in Dmp1-KO mice (p < 0.01). B, FGF23 concentrations in the sera of 6-week-old WT, Dmp1-KO and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice. Data are mean ± S.E. (n = 5). **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. The serum FGF23 level in the Dmp1-KO mice was significantly higher than in the WT mice (p < 0.001). The FGF23 level in Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice was significantly higher than in the WT mice (p < 0.01) but lower than in the Dmp1-KO mice (p < 0.01). C, sections were from the diaphysis region of tibia from 6-week-old WT, Dmp1-KO, and Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice. Immunohistochemical staining on these sections showed that the expression level of FGF23 in the bone of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice was higher than in WT, but lower than in the Dmp1-KO mice.

DISCUSSION

Under physiological conditions, DMP1 is mainly present as the processed NH2-terminal and COOH-terminal fragments in the ECM of bone and dentin (7, 13), while the full-length form of DMP1 is found only in trace amounts (14). In contrast to the WT mice, the bone ECM of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice generated in this study contained significant amounts of full-length DMP1 (i.e. D213A-DMP1) and only trace amounts of DMP1 fragments. These trace amounts may have originated from the cleavage of the mutant protein at a redundant peptide bond serving as a cryptic cleavage site. Under physiological conditions, such a cryptic cleavage site may not be active, while in the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice, the substitution of Asp213 might cause this putative site to be activated. If this cryptic cleavage site is present, it must be very close to Asp213, since the migration rate of the DMP1 fragments from the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice was very similar to that of the natural fragments of DMP1. Previous in vitro work in our laboratory showed that trace amounts of DMP1 fragments were present (21) in the culture medium of human embryonic kidney 293 cells expressing the mutant D213A-DMP1, which agrees with the findings in this study. It was obvious that such trace amounts of the DMP1 fragments were far from sufficient at maintaining the DMP1 functions since the skeletal phenotypes of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice were similar to those of the Dmp1-KO mice. These findings indicate that the proteolytic processing of DMP1 to produce sufficient amounts of DMP1 fragments is essential for the formation of healthy bone. The trace amounts of DMP1 fragments in the bone ECM of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice may be responsible for the slight differences in their skeleton compared with the Dmp1-KO mouse skeletons. For example, the long bones of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice were slightly longer than those of the Dmp1-KO mice.

BMP-1/Tolloid-like proteinases have been shown to cleave bacterium-made rat DMP1 at the NH2 terminus of Asp197 (19), which corresponds to Asp213 in the mouse DMP1. Recently, another study (25) showed that BMP-1 cleaves recombinant human DMP1 made in the eukaryotic cells at the NH2 terminus of Asp218, which corresponds to Asp213 in the mouse DMP1. This cleavage was blocked when Met215 and Gln216 were replaced by IIe215 and His216 (i.e. MQSDDP motif was changed to IHSDDP) (25). In the present study, we used full-length DMP1 isolated from mouse bone and showed that BMP-1 cleaved normal DMP1, but not D213A-DMP1, providing further proof that BMP-1/Tolloid-like proteinases are the enzymes responsible for the proteolytic processing of DMP1 at the NH2 terminus of Asp213 in the mouse DMP1 sequence. However, the cleavage pattern observed in the in vitro studies to date was different from that seen in the ECM of bone and dentin. The protein chemistry work revealed that the cleavage of DMP1 in the ECM of rat bone and dentin results in the presence of two clusters of protein bands on SDS-PAGE; these clusters represent more than two fragments from the NH2-terminal region and several fragments from the COOH-terminal region of the DMP1 amino acid sequence (7). We speculate that under physiological conditions (i.e. in the ECM of bone and dentin), the cleavage at the NH2 terminus of Asp213 (in mouse) represents an initial, first-step scission in the whole cascade of DMP1 processing. Furthermore, we surmise that conformational changes after the initial cleavage at Ser212-Asp213 expose other sites for the BMP-1/Tolloid-like proteinases to introduce further scissions. Thus, the breaking of bond Ser212-Asp213 starts a chain of proteolytic events, resulting in the cleavage of several other peptide bonds and producing multiple fragments. It is also possible that after the initial cleavage of DMP1 at Ser212-Asp213 by the BMP-1/Tolloid-like proteinases, the released DMP1 fragments may be further trimmed (processed) by matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9, which gives rise to the observed heterogeneity of the DMP1 fragments. It is worth noting that matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 are expressed in bone (26) and dentin (27). These two metalloproteinases have been shown to cleave the NH2-terminal fragment of dentin sialophosphoprotein (27), another acidic protein sharing a number of unique similarities with DMP1 (8, 20).

In vitro studies have shown that the 57-kDa fragment (COOH-terminal) and the 37-kDa fragment (NH2-terminal) of DMP1 nucleate hydroxyapatite crystals, while the full-length DMP1 and DMP1-PG inhibit crystal growth (15, 16, 28). The results from the present study showed that the skeletal phenotypes of the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice were very similar to those of the Dmp1-KO mice, indicating that the D213A substitution resulted in a failure in the processing of DMP1, which subsequently produced the loss of function of this protein during osteogenesis. We previously hypothesized that the proteolytic processing of DMP1 is a key step essential for the biological functioning of this protein in biomineralization (8, 20). The in vitro and in vivo findings in this study lend strong support to this hypothesis.

The serum levels of FGF23 in the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice were lower than in the Dmp1-KO mice but higher than in the WT mice. The increase in the serum level of FGF23 in the Dmp1-KO mice has been found to trigger a decrease in the serum level of phosphate (11). Although the mechanism by which DMP1 participates in the regulation of FGF23 is unclear, the results from the present study suggest that the processed fragments of DMP1, not the full-length form, are likely the molecular variants of this protein involved in the regulation of the growth factor. The differences in the FGF23 levels between the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg and Dmp1-KO mice may be due to the presence of trace amounts of DMP1 fragments in the Dmp1-KO/D213A-Tg mice.

In summary, the observation that the expression of the D213A-Dmp1 transgene failed to rescue the skeletal phenotypes of the Dmp1-KO mice indicates that the proteolytic processing of DMP1 is an essential step in osteogenesis. Further studies are warranted to explore how the biologically active cleavage products of DMP1 interact physically with other components within the complex milieu of bone and dentin ECM. The findings from this study provide the basic foundation for directing future investigations in this area of research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeanne Santa Cruz for assistance with the editing of this article, and Dr. Paul Dechow for assistance in the μ-CT analyses. We are also thankful to Drs. William T. Butler, Tao Peng, and Bingzhen Huang for their contributions during the earlier stages of this study.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DE 005092 (to C. Q.) and DE015209 (to J. Q. F.).

- DMP1

- dentin matrix protein 1

- BMP-1

- bone morphogenetic protein 1

- BV/TV

- bone volume to total volume ratio

- DMP1-N

- the NH2-terminal fragment of DMP1

- DMP1-C

- the COOH-terminal fragment of DMP1

- DMP1-PG

- the proteoglycan form of the NH2-terminal fragment of DMP1

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- FGF23

- fibroblast growth factor 23

- Gdm-HCl

- guanidinium hydrochloride

- NCPs

- non-collagenous proteins

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- Tb.N

- trabecular number

- Tb.Th

- trabecular thickness

- Tb.Sp

- trabecular separation

- μ-CT

- microcomputed tomography.

REFERENCES

- 1.George A., Sabsay B., Simonian P. A., Veis A. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 12624–12630 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Souza R. N., Cavender A., Sunavala G., Alvarez J., Ohshima T., Kulkarni A. B., MacDougall M. (1997) J. Bone Miner. Res. 12, 2040–2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirst K. L., Ibaraki-O'Connor K., Young M. F., Dixon M. J. (1997) J. Dent. Res. 76, 754–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDougall M., Gu T. T., Luan X., Simmons D., Chen J. (1998) J. Bone Miner. Res. 13, 422–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toyosawa S., Shintani S., Fujiwara T., Ooshima T., Sato A., Ijuhin N., Komori T. (2001) J. Bone Miner. Res. 16, 2017–2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng J. Q., Zhang J., Dallas S. L., Lu Y., Chen S., Tan X., Owen M., Harris S. E., MacDougall M. (2002) J. Bone Miner. Res. 17, 1822–1831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin C., Brunn J. C., Cook R. G., Orkiszewski R. S., Malone J. P., Veis A., Butler W. T. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34700–34708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin C., D'Souza R., Feng J. Q. (2007) J. Dent. Res. 86, 1134–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye L., MacDougall M., Zhang S., Xie Y., Zhang J., Li Z., Lu Y., Mishina Y., Feng J. Q. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19141–19148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye L., Mishina Y., Chen D., Huang H., Dallas S. L., Dallas M. R., Sivakumar P., Kunieda T., Tsutsui T. W., Boskey A., Bonewald L. F., Feng J. Q. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6197–6203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng J. Q., Ward L. M., Liu S., Lu Y., Xie Y., Yuan B., Yu X., Rauch F., Davis S. I., Zhang S., Rios H., Drezner M. K., Quarles L. D., Bonewald L. F., White K. E. (2006) Nat. Genet. 38, 1310–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenz-Depiereux B., Bastepe M., Benet-Pagès A., Amyere M., Wagenstaller J., Müller-Barth U., Badenhoop K., Kaiser S. M., Rittmaster R. S., Shlossberg A. H., Olivares J. L., Loris C., Ramos F. J., Glorieux F., Vikkula M., Jüppner H., Strom T. M. (2006) Nat. Genet. 38, 1248–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qin C., Huang B., Wygant J. N., McIntyre B. W., McDonald C. H., Cook R. G., Butler W. T. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8034–8040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang B., Maciejewska I., Sun Y., Peng T., Qin D., Lu Y., Bonewald L., Butler W. T., Feng J., Qin C. (2008) Calcif. Tissue Int. 82, 401–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tartaix P. H., Doulaverakis M., George A., Fisher L. W., Butler W. T., Qin C., Salih E., Tan M., Fujimoto Y., Spevak L., Boskey A. L. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 18115–18120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gericke A., Qin C., Sun Y., Redfern R., Redfern D., Fujimoto Y., Taleb H., Butler W. T., Boskey A. L. (2010) J. Dent. Res. 89, 355–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maciejewska I., Qin D., Huang B., Sun Y., Mues G., Svoboda K., Bonewald L., Butler W. T., Feng J. Q., Qin C. (2009) Cells Tissues Organs 189, 186–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maciejewska I., Cowan C., Svoboda K., Butler W. T., D'Souza R., Qin C. (2009) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 57, 155–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steiglitz B. M., Ayala M., Narayanan K., George A., Greenspan D. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 980–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin C., Baba O., Butler W. T. (2004) Crit. Rev. Oral. Biol. Med. 15, 126–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng T., Huang B., Sun Y., Lu Y., Bonewald L., Chen S., Butler W. T., Feng J. Q., D'Souza R. N., Qin C. (2009) Cells Tissues Organs 189, 192–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu Y., Ye L., Yu S., Zhang S., Xie Y., McKee M. D., Li Y. C., Kong J., Eick J. D., Dallas S. L., Feng J. Q. (2007) Dev. Biol. 303, 191–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng J. Q., Huang H., Lu Y., Ye L., Xie Y., Tsutsui T. W., Kunieda T., Castranio T., Scott G., Bonewald L. B., Mishina Y. (2003) J. Dent. Res. 82, 776–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baba O., Qin C., Brunn J. C., Wygant J. N., McIntyre B. W., Butler W. T. (2004) Matrix Biol. 23, 371–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Von Marschall Z., Fisher L. W. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32730–32740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filanti C., Dickson G. R., Di Martino D., Ulivi V., Sanguineti C., Romano P., Palermo C., Manduca P. (2000) J. Bone Miner. Res. 15, 2154–2168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamakoshi Y., Hu J. C., Iwata T., Kobayashi K., Fukae M., Simmer J. P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 38235–38243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gajjeraman S., Narayanan K., Hao J., Qin C., George A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 1193–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]